Abstract

Drug resistance in HIV-1 protease, a barrier to effective treatment, is generally caused by mutations in the enzyme that disrupt inhibitor binding but still allow for substrate processing. Structural studies with mutant, inactive enzyme, have provided detailed information regarding how the substrates bind to the protease yet avoid resistance mutations; insights obtained inform the development of next generation therapeutics. Although structures have been obtained of complexes between substrate peptide and inactivated (D25N) protease, thermodynamic studies of peptide binding have been challenging due to low affinity. Peptides that bind tighter to the inactivated protease than the natural substrates would be valuable for thermodynamic studies as well as to explore whether the structural envelope observed for substrate peptides is a function of weak binding. Here, two computational methods — namely, charge optimization and protein design — were applied to identify peptide sequences predicted to have higher binding affinity to the inactivated protease, starting from an RT–RH derived substrate peptide. Of the candidate designed peptides, three were tested for binding with isothermal titration calorimetry, with one, containing a single threonine to valine substitution, measured to have more than a ten-fold improvement over the tightest binding natural substrate. Crystal structures were also obtained for the same three designed peptide complexes; they show good agreement with computational prediction. Thermodynamic studies show that binding is entropically driven, more so for designed affinity enhanced variants than for the starting substrate. Structural studies show strong similarities between natural and tighter-binding designed peptide complexes, which may have implications in understanding the molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in HIV-1 protease.

Keywords: Charge Optimization, Protein Design, Dead-End Elimination

Introduction

Current treatment for HIV-1 infection has been increasingly limited by the growing trend of drug resistance 1–3. One of the most common forms of resistance is mutations in the protease, an enzyme essential for the viral life cycle and a common target for drug treatment 3–6. One consistent feature of multi-drug resistant HIV-1 protease is that binding to inhibitors is significantly reduced while substrate binding and processing remains at viable levels 7,8. Therefore, in order to understand mechanisms of drug resistance and gain insight into how to design new drugs, it is important to understand how the substrate peptides themselves interact with the protease and can be catalytically cleaved by variants containing resistance mutations. Several recent studies have been conducted to address this issue, mostly through structural analysis of complexes between the protease and substrate analogs 9–11, or between inactive protease and actual peptides derived from cleavage sites 12,13. These studies have revealed structural motifs that may be used for substrate recognition 13, as well as compensatory structural changes in response to resistance mutations 10,11,14,15. In addition, these studies propose that HIV-1 protease substrate recognition may be based on shape rather that sequence 13, and have led to the hypothesis that protease inhibitors resembling this “substrate envelope” may be less likely to induce drug resistance because mutations that affect the inhibitor would also be likely to interfere with substrate processing 13,16–19.

Besides structural analysis of substrate complexes, another useful tool in understanding drug resistance in HIV-1 protease has been to examine the thermodynamics of inhibitor binding to both wild-type and drug resistant protease using calorimetry 16,20. These studies support a connection between the enthalpy and entropy of binding with the ability for inhibitors to evade resistance mutations 21,22. A combination of these two experimental approaches, to determine the thermodynamics of binding for peptides in the context of the inactivated protease, may be very useful in learning more about how peptides interact with the protease.

Although the structures of six decameric substrate peptides have been solved in complex with an inactivated (D25N) protease 13, obtaining calorimetric measurements of peptide binding has been challenging, most likely due to poor affinity. The protease forms a homodimer that places a pair of aspartic acid residues (Asp25 from each monomer) at the active site. Although the charge state of this aspartyl dyad during substrate binding is uncertain 23–25, it is likely that the D25N inactivating mutation causes a net charge change of at least one charge unit, possibly accounting for the low affinity. Only one substrate peptide, derived from the reverse transcriptase–RNase H (RT–RH) cleavage site (P5-P5′ sequence: GAETF*YVDGA), shows marginally detectable binding and low micromolar affinity for the inactivated D25N protease (Figure 3A). In order to obtain clean thermodynamic data, and to determine if there exist fundamental differences in the way weaker and tighter binding peptides interact with the protease in terms of the definition of the substrate envelope, we undertook the design of tighter binding substrate-like peptides to the inactivated protease, using the RT–RH peptide–inactivated protease complex as an initial model.

Figure 3.

Isothermal titration calorimetry data for the binding of RT–RH and designed peptides to the inactivated protease. In (A), the sequences of peptides tested (mutations underlined), their design origin, and their determined thermodynamic parameters of binding are shown. Units of the dissociation constant Kd are μM, and energies are in kcal/mol. Errors on thermodynamic parameters are derived from the fitting error after repeating the experiment at least three times. A comparison of the ITC traces for the RT–RH peptide (B) and Peptide 2 (C) shows that a sharp transition is only present for the tighter binding designed peptide.

Computational techniques are well suited for generating suggestions to improve affinity of protein–protein and peptide–protein interfaces; thermodynamic and structural studies of the binding of enhanced affinity peptides can provide insight into substrate binding, as well as into computational methodology. To this end, we applied two computational techniques to design tighter binding peptides to the inactivated protease. The first technique, charge optimization 26–36, has been shown to be a useful tool in identifying chemical groups that have poor electrostatic complementarity for their binding partner. Charge optimization, based on a linear response continuum electrostatic model, varies the partial atomic charges on a protein or peptide side chain so as to balance the cost of desolvation with favorable interactions made upon binding. The resulting charge distributions are optimal in that the electrostatic component of the computed binding free energy is maximally favorable. Mutations to improve binding can be suggested by identifying amino acid substitutions that have charge distributions similar to that of the global optimum, or by repeating the optimization under several charge constraints and selecting mutations that match those that are favorable.

One of the current limitations of charge optimization theory is that the concept is most applicable when the geometry of the bound and unbound states for the ligand being optimized are pre-determined. In general, a single rigid model of the complex is used to represent the bound state, while a rigid separation of the binding partners is used to represent the unbound state of the ligand. While implementations are feasible with conformational change, the rigid binding approximation provides added numerical benefits 30,37. Moreover, rigid binding is a reasonable model in this study due to the extended conformation of the substrate peptide, which allows for a fully solvent-exposed unbound state.

Amino-acid substitutions suggested by charge optimization should generally have a similar shape to the starting residue, in addition to a more optimal charge distribution. Because all amino-acid substitutions involve some degree of shape change, one reasonable way to evaluate a suggestion from charge optimization is to build the mutation using molecular mechanics and evaluate its computed change in binding free energy using the same continuum electrostatics model 36. Although the charge optimization and building procedure does allow for flexibility in the designed side chain, it is still ultimately limited because the initial set of suggested mutations are derived from fixed geometry calculations.

To allow for side-chain flexibility in both the designed peptide and the protease active site, to relax the requirement that suggested mutations are shape conservative, and to see how much of a difference these features make, we have applied a second computational technique to improve peptide affinity — namely, protein design. Computational protein design methods 38–40 have been successfully applied to stabilize protein folds 41,42, create new protein folds 43,44, and design protein interfaces 45–49. Protein design techniques search a combinatorial space of discrete amino-acid identities and geometries in order to identify either global minimum or low energy sequences and structures with desired properties. In the case of designing tighter binding peptides to the inactivated protease, we allowed the RT–RH peptide side chains to change their amino-acid identity and conformation, protease active site residues to change their conformation only, and searched this combinatorial space using discrete search algorithms 50–53 to identify global minimum energy structures for single, double, and triple mutants of the RT–RH sequence. These complexes were then examined for predicted improvements in binding affinity.

Three peptides predicted to bind tighter to the inactivated protease resulting from computational techniques were tested experimentally using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). One peptide, containing a valine mutation at the P2 position of the starting RT–RH substrate, bound greater than ten-fold tighter. Thermodynamic measurements of binding showed that peptide–inactive protease association is entropically driven, and that mutations predicted to improve peptide binding tended to increase the entropic contribution even further. Crystal structures were also obtained for each of the three designed peptide complexes, showing good agreement with calculation and substrate peptide complexes. Overall, agreement between both charge optimization and protein design along with experimental validation reinforces the usefulness of these computational methods in improving binding interfaces, and demonstrates a commonality in binding geometry for weaker and tighter binding substrate complexes.

Results and Discussion

Electrostatic optimization of peptide binding

Starting with the crystal structure of a RT–RH substrate peptide bound to inactivated (D25N) HIV-1 protease (Protein Data Bank ID 1KJG), charge optimization was applied to each RT–RH substrate peptide side chain independently. The charges of all other peptide, and all protease atoms were kept at their parameterized values. Four different sets of constraints were applied to the resulting charge distributions; in separate calculations the optimized side chain total charge was required to be negative (−1e), neutral (0e), or positive (+1e), and, as a control, all partial atomic charges in the optimized side chain were set to zero, which is similar to a shape conserving hydrophobic replacement. The results of these charge optimization studies are summarized in Table I. Charge optimization produced new partial atomic charge values that satisfy the sum-of-charges constraint for the side chain without modifying the shape, which is a useful guide for design studies.

Table I.

Changes in Electrostatic Binding Energy upon Charge Optimization of Peptide Side Chains

| Residue | Position | Δ ΔGhφ | Mutation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala | P4 | 0.00 | +4.39 | −0.23 | +0.89 | – | |||

| Glu | P3 | −2.39 | −3.45 | −2.94 | −0.56 | Gln, Leu, Asp | |||

| Thr | P2 | −1.11 | +6.99 | −1.27 | +11.74 | Val | |||

| Phe | P1 | −0.78 | +1.99 | −1.30 | +7.18 | – | |||

| Tyr | P1′ | −0.83 | +0.37 | −1.41 | +2.62 | – | |||

| Val | P2′ | 0.00 | +8.86 | −0.13 | +10.75 | – | |||

| Asp | P3′ | +0.51 | −0.08 | +0.03 | +3.10 | – | |||

| Glya | P4′ | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – | |||

| Ala | P5′ | 0.00 | −0.24 | −0.05 | +0.40 | – |

Changes in the electrostatic component of the binding free energy after optimization of the side-chain partial atomic charges. Results are shown in kcal/mol for constraining all partial atomic charges to zero (hydrophobic isostere, Δ ΔGhφ), as well as constraining the total residue charge to −1e, 0e, and +1e. Negative free energy changes correspond to improved binding. For some positions, mutations suggested by the optimization data are listed.

In these calculations, glycine is not considered to have a side chain, thereby precluding its electrostatic optimization.

Out of the nine peptide residues visible in the structure, the four between the P3 and P1′ positions show computed, idealized electrostatic improvements greater than 1.0 kcal/mol upon charge optimization. In addition, these four residues can achieve a significant portion of this improvement by selecting an all-zero charge distribution, essentially creating a hydrophobic isostere. This suggests that there is little energetic advantage to having a strongly dipolar group or a formally charged group at these four sites, as the electrostatic interaction gained upon binding is generally unable to offset the cost of desolvating the side chain. This finding is consistent with the dominantly hydrophobic nature of the P2–P2′ side-chain binding pockets of the protease. Overall, most residues best optimum corresponded to the same net charge as their standard state at pH 7, with the exception of Glu-P3 which is relatively indifferent to the net charge constraint. This is due to the fact that Glu-P3 is relatively solvent exposed in the bound state, with the −1e optimized and 0e optimized charge distributions having a difference of only 0.9 kcal/mol in desolvation penalty, compared to a corresponding value of 9.5 kcal/mol for Thr-P2.

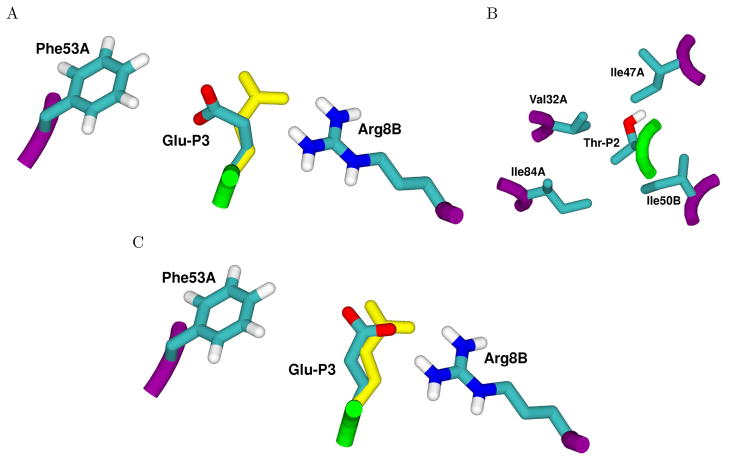

Given the energetics of charge optimization and the resulting partial atomic charge distributions, mutations were considered that have a similar shape but an altered charge distribution that corresponds as closely as possible to optimality. The charge optimization results for the P3 and P2 positions are indeed suggestive of mutations that have a similar shape but with a more optimal charge distribution. The glutamate side chain at P3 shows possible improvements of 3 kcal/mol or greater upon optimization to a neutral or negative net charge. In addition, the energy of the hydrophobic isostere is a 2.4 kcal/mol improvement over the parameterized charges, indicative of a desolvation penalty that is not fully recovered through direct electrostatic interaction with the protease upon binding. This result can be explained by the environment of the Glu-P3 side chain in the bound complex (Figure 1A), where the partially solvent exposed side chain is not making any electrostatic contacts with the protease. In the case of the neutrally optimized side chain, the partial atomic charges depolarize by moving towards zero, and in the negatively charged case, charge tends to accumulate near the Cγ atom and its bonded hydrogen atoms. The clustering of negative charge on these atoms is reflective of their proximity to the positively charged Arg8B side chain on the protease (Figure 1B). These results are suggestive of three mutations. The first is substitution with glutamine, which eliminates the net charge, has a less polar charge distribution, is very shape conservative, and is suggested by the large improvements from depolarization. The second is leucine, which is hydrophobic and has less shape conservation due to the change in hybridization at the branched carbon, but has a charge distribution similar to a hydrophobic isostere. The third is substitution with aspartate, which although very different in shape, may mimic the increase of negative charge near the Cγ atom of the glutamate side chain upon optimization to a −1e total charge. These suggestions were each pursued with more specific computations (described below).

Figure 1.

Molecular environments of the Glu-P3 (A) and Thr-P2 (B) peptide residues found to be suboptimal for electrostatic binding in the RT–RH crystal complex. The position of the P3 glutamate (A, atom colors, center) is pointed away from Arg8B and makes contact with Phe53A. Calculations suggest an alternative conformation (yellow) that makes better electrostatic interactions with Arg8B at the expense of packing. The wild-type P2 threonine residue (B, center) is situated in a pocket composed of four hydrophobic residues and makes no polar interactions. The crystal structure of a designed mutant peptide with a single threonine-to-valine substitution at the P2 position exhibits a structural rearrangement of the Glu-P3 residue (C, atom colors) as compared to the starting sequence (A). This rearrangement is well supported by calculation (A, C, yellow). This figure was prepared with VMD 83 and Raster3D 84.

At the P2 position, the starting threonine has a similar optimization profile to the glutamate at P3. The P2 side chain is surrounded by a hydrophobic pocket (Figure 1B), and the threonine hydroxyl does not make hydrogen bonding interactions in the crystal structure. As a result, both the hydrophobic isostere and 0e optimization results show significant possible improvements because the desolvation penalty of the hydroxyl can not be recovered in direct electrostatic interaction with the protease. The obvious candidate mutation at P2 is valine, which has a similar shape to threonine, yet is very hydrophobic.

For the other two residues that show possible improvement greater than 1 kcal/mol, Phe-P1 and Tyr-P1′, there are no clear candidate mutations. In both cases, conversion to a hydrophobic isostere is favorable, and optimization to a neutral side chain results in a charge distribution that depolarizes the phenyl ring even further than the parameterized charges, which consist of −0.125e and +0.125e dipoles along each C–H bond. For Phe-P1, no obvious mutation to a naturally occurring amino acid exists that has these properties. In the case of Tyr-P1′, one might consider conversion to Phe; however, most of the 0.6 kcal/mol improvement going from a hydrophobic isostere to an optimal neutral residue involves increasing the dipole of the hydroxyl group. This is due to a hydrogen bonding interaction between the hydroxyl group of Tyr-P1′ and the side chain of Arg8A in the protease. Unfortunately, there is no naturally occurring amino-acid side chain that can maintain this favorable hydrogen bonding interaction, have a similar shape to tyrosine, and be otherwise less polarized than an aromatic ring. Therefore, the optimization results for the P1 and P1′ positions do not suggest obvious mutations.

Computed binding energetics of mutants suggested from charge optimization

Although the charge optimization methodology is extremely useful in identifying regions of poor electrostatic complementarity, it is limited in that it assumes the conformation of the side chains are rigid during the calculation, and any prediction based on the results is only accurate within this fixed shape assumption. Because all mutations involve some degree of shape change, the suggested mutations were explicitly modeled in order to further screen for improved binding candidates.

To this extent, the starting side chain as well as candidate mutations proposed in the previous section were built into the structure and their computed energetics were compared to that of the crystal, as summarized in Table II. At the P3 position, rebuilding the initial glutamate using the same procedure applied to mutants led to an unexpectedly large energetic improvement over the crystal conformation, mainly due to its selection of an alternative conformation that made more favorable interactions with the side chain of Arg8B (Figure 1A). In this alternative conformation, improved electrostatic interactions were partially offset by worsened van der Waals packing. The significance of this finding is that if this alternative conformation were truly populated, a mutation at this position would need to exceed this 1.5 kcal/mol improvement over the crystal structure in order to be a good candidate for observable tighter binding.

Table II.

Binding Energies of Mutants Suggested From Charge Optimization

| Residue | Position | Mutation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu | P3 | Glumin | −3.2 | +1.7 | −1.5 | |||

| Glnmin | −0.8 | −1.1 | −1.9 | |||||

|

|

−1.2 | −0.2 | −1.5 | |||||

|

|

−1.1 | −0.5 | −1.7 | |||||

| Leumin | −1.6 | +0.1 | −1.5 | |||||

| Aspmin | −3.3 | +3.2 | 0.0 | |||||

| Thr | P2 | Thrmin | +0.9 | −0.9 | 0.0 | |||

| Valmin | −2.2 | −0.1 | −2.4 | |||||

| Valcrystal | −0.7 | −0.7 | −1.5 | |||||

Estimated change in binding free energy for rebuilt starting and mutant structures suggested from charge optimization. All energetics are relative to the crystal structure, and are in kcal/mol. Negative free energies correspond to improved binding. Energy differences are shown for two rebuilding techniques, one in which a minimized structure is obtained for the mutating residue (min), and an alternative method in which the crystal structure dihedral angles are used to rebuild the mutant side chain (crystal). For the Glu to Gln mutation, there are two possible orientations using the crystal dihedrals. Energetics are shown for the electrostatic and van der Waals (vdW) components of the free energy, as well as the total free energy difference, including a surface area contribution.

The mutation to glutamine at P3, irrespective of whether the side chain was built in its minimum energy conformation or directly on top of the crystal glutamate, led to a calculated improvement of about 1.5 kcal/mol over the crystal structure, mainly due to improved electrostatics as identified by charge optimization. However, if the glutamate can adopt the alternative conformation, mutation to glutamine is not predicted to be a significant binding improvement. Therefore, the mutation of glutamate to glutamine at P3 is a good choice for an experimental test, because if the binding energy were to remain the same, it would suggest that the glutamate residue may spend some of its time interacting more favorably with Arg8B in solution.

Additional mutations suggested by charge optimization at the P3 position include leucine and aspartate, which attempt to mimic the optimal charge distributions for a neutral and negatively charged side chain, respectively. Designing a leucine at P3 leads to a computed electrostatic benefit of 1.6 kcal/mol over the crystal structure, as expected from charge optimization, with nearly unchanged van der Waals interactions. This results in an energetic profile similar to that of the glutamine mutation, where a predicted improvement is dependent on the likelihood of the alternative initial glutamate conformation. Building and relaxing aspartate at this position led to greatly improved electrostatic interactions, due to proximity to Arg8B, but weakened van der Waals packing due to the reduced size of aspartate compared to glutamate. These effects canceled, leading to the same predicted binding free energy as the crystal structure, and indicate that the aspartate mutation may be less likely to provide a binding improvement independently.

At the P2 position, rebuilding of the starting threonine residue led to similar energetics as the crystal, with a small tradeoff between electrostatics and packing. The suggested valine mutation at this position is computed to be favorable by 1.5–2.5 kcal/mol depending on whether the valine was rebuilt on top of the threonine or in an energy minimized geometry. This improvement is mainly accounted for by eliminating the desolvation penalty for the threonine hydroxyl group. Because valine has roughly the same shape as threonine, and is predicted to bind better in several built geometries, this mutation is an excellent candidate for improved binding.

Overall, building mutations into the structure is a useful tool to assess the feasibility of mutations suggested by charge optimization. In some cases, the building procedure highlights weaknesses of the rigid binding model used in charge optimization, as exemplified by the Gln-P3, Leu-P3, and Asp-P3 suggested mutations, and in other cases it confirms its usefulness, such as the Val-P2 mutation. Mutations that are good candidates for experimental validation are the shape conservative Gln-P3, computed to have improved binding if the crystal structure is the correct reference structure, serving as a good diagnostic for the interactions of the starting glutamate, and the Val-P2 mutation, highly shape conservative and computed to be favorable in multiple geometries.

Improving binding through protein design

The charge optimization and building procedure presented above, although very useful for rapidly identifying side chains with poor electrostatic complementarity, is still ultimately limited by its fixed-shape approximation. Mutations initially suggested for building need to maintain shape similarity, and side chains on the protease and at peptide positions not being optimized and built must be kept in fixed conformation. To relax these requirements, we have applied a full computational protein design treatment that systematically considers all twenty common amino acids, except proline, in multiple conformations for the central eight side chains (P4–P4′) of the peptide, while simultaneously considering active-site side chains in all rotamer combinations. Thus, this procedure permits side chain but not backbone relaxation to accommodate peptide mutations. Due to the large number of possible peptide sequences to consider, global minimal energy conformations were obtained for all single, double, and triple mutants from the wild-type RT–RH peptide sequence in a discrete conformational space, and their rigid binding energetics were computed to identify complexes with improved predicted binding properties.

When the wild-type RT–RH sequence was rebuilt using this protein design procedure, the same conformational heterogeneity observed at the P3 glutamate position in the charge optimization protocol was again identified. These two conformations for the P3 glutamate are separated by 0.5–2.0 kcal/mol depending on parameter set, and show the same energetic tradeoff between electrostatics and van der Waals packing upon the change of geometry to make closer interactions with Arg8B (Figure 1A). In addition, different parameter sets disagree about which state is more favorable, with van der Waals energies derived from PARAM19 favoring the crystal conformation, and those from united-atom AMBER favoring the alternative conformation. To factor out this uncertainty, the energetics for any sequence that does not involve a mutation at P3 was referenced against the starting structure with the same conformation for Glu-P3, and any structure involving a mutation at P3 was required to score better than both P3 conformations of the starting sequence. In all cases, sequences predicted to have improved binding were also required to score better than the reference in both electrostatics with solvation and van der Waals energies across multiple parameter sets. That is, given uncertainty in structure and some disagreement between models, we required all models to agree on mutations predicted to improve affinity, which is a conservative criterion. In addition, because the balance between packing and electrostatic interactions is sometimes difficult to quantify, we further required improvements in both terms simultaneously, which is again conservative.

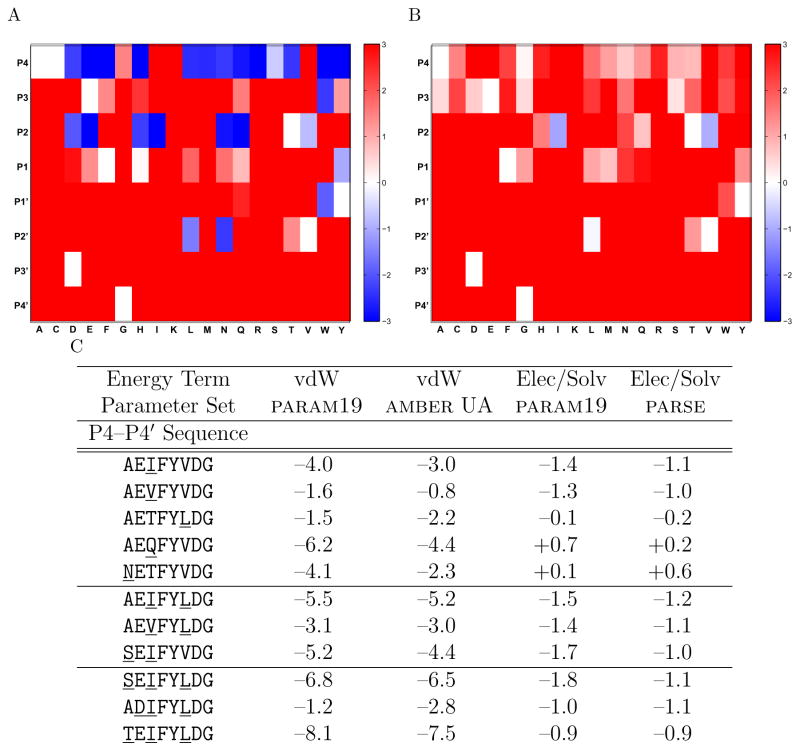

The binding energetics for all single mutations to the RT–RH sequence are presented in Figure 2, showing the lesser improvement in binding free energy across two different van der Waals parameter sets (Figure 2A) and two different electrostatics/solvation parameter sets (Figure 2B) relative to the appropriate initial reference structure. In terms of packing interactions, there exist many opportunities for improvement identified computationally, especially at the P4 and P2 positions. Substitution of the solvent exposed alanine at the P4 position with larger amino acids is generally computed as an advantage for van der Waals’ interactions due to the ability to pack against the side of the binding interface. The starting valine residue at P2 sits in a pocket that computations suggest can accommodate a slightly larger amino acid, and moderately sized amino acids provide a packing advantage. Other pockets such as P1, P1′, and P2′ appear also to accommodate larger amino acids for improved packing interactions.

Figure 2.

Changes in binding free energy contributions computed for mutants derived from protein design calculations. The worst-case changes across two van der Waals (vdW) (A) and two electrostatics/solvation (Elec/Solv) (B) parameter sets were computed for all single mutations (except proline) at each peptide position relative to the appropriate starting RT–RH sequence. Changes upon mutation in excess of +3 kcal/mol, or mutations ranked worse than +5 kcal/mol from the original sequence in stability of the complex, were dropped from consideration in the protein design calculation and are represented as the darkest red. Sequences and relative energetics for several of the best electrostatically ranking single, double, and triple mutations are also presented (C), broken down by energy term and parameter set. Mutations to the sequence are underlined, relative energies are in kcal/mol, and negative numbers indicate computed improvements to binding.

The P3′ and P4′ positions show no opportunity for improvement; no alternative side chain from the reference could be grown from the fixed backbone with a reasonable computed energy. In the case of the P3′ aspartate, mutation to any other side chain caused the energy of the bound complex to be at least 5 kcal/mol worse than the reference, thereby excluding it from further consideration. At the P4′ position, any amino acid besides the reference glycine caused a large van der Waals clash with a region of the fixed protease backbone.

Single mutations computed to offer a binding advantage in electrostatics and solvation were much less numerous, with only one position, P2, offering any significant opportunities. Mutations to valine or isoleucine at P2 were predicted to be better electrostatically than the starting threonine, in excellent agreement with charge optimization calculations. Again, the valine and isoleucine mutations were computed to avoid the desolvation penalty associated with burying the threonine hydroxyl group in a hydrophobic pocket. Although no additional positions yielded significant solvation improvements, there were several mutations that were computed to have unchanged electrostatics, for example, a serine mutation at P3, a glutamine mutation at P2, or a leucine mutation at P2′.

Van der Waals packing and electrostatics (with solvation) are important forces governing binding, but it is unclear that they contribute equally to successful molecular design. One might choose to assign higher confidence to mutations that score well in both of these properties across multiple parameter sets, represented by substitutions that are white-to-blue in both Figures 2A and 2B. In Figure 2C, several of the sequences that scored best in electrostatics/solvation while still maintaining a favorable van der Waals binding free energy change are presented, along with their improvements over the reference residue in two parameters sets. Mutations at P2 to isoleucine and valine were predicted to be quite favorable, along with leucine at P2′, while other mutations such as glutamine at P2 and asparagine at P4 were computed to be excellent for packing but slightly unfavorable for electrostatics/solvation.

Double and triple mutant sequences were also computationally screened for improved binding, and five of the top sequences in electrostatics/solvation that maintained good packing are also shown in Figure 2C. Overall, the double and triple mutants were additive in that their predicted improvements could be explained by adding together the benefit of their individual single mutations. This allowed less favorable mutations to be carried along into high ranking sequences by pairing them with the most favorable individual mutations, as was often observed in the triple mutant sequences. For example, one of the highest electrostatically ranked triple mutations, containing the favorable isoleucine mutation at P2 and leucine mutation at P2′, permits the P3 aspartate mutation which, although deficient in van der Waals interaction, is electrostatically reasonable.

The mutations identified from protein design calculations served to support and extend those derived from charge optimization calculations. The protein design results recapitulated the ability to improve electrostatics at the P2 position by substituting threonine with a valine. In addition, they go beyond the fixed shape assumption and propose that isoleucine can achieve additional packing interactions at this position in addition to improving electrostatic complementarity. Although the protein design methods did not identify improvements at the P3 position, this was largely due to the difficulty in making predictions when the reference structure was in question, and the strict requirements placed on predicted improvements at this position. Protein design also identified several sites where improved packing interactions could be made, such as the P2′ position, but did not discover any additional electrostatic improvements beyond those identified by charge optimization.

Experimental determination of binding energetics for designed peptides

In order to experimentally test the effectiveness of the computational design procedures, three designed peptides, one from protein design and two suggested from charge optimization, were tested along with the starting RT–RH peptide for binding to the inactivated (D25N) protease using isothermal titration calorimetry (Figure 3A). These designed peptides include one of the high scoring triple mutants from protein design (Peptide 1), as well as the shape conserving T-P2-V mutation (Peptide 2) and diagnostic E-P3-Q mutation (Peptide 3) suggested from charge optimization. The triple-mutant peptide selected for synthesis and testing (Peptide 1) was computed to be less favorable for packing than other triple mutants (Figure 2C), most likely due to the aspartate mutation at P3. However, it was chosen because of the promising electrostatic profile of the Asp-P3 mutant (Table II), and the computed optimality of the corresponding reference aspartate at P3′.

The starting RT–RH sequence has an observed dissociation constant of about 6 μM, and an overall poor experimental binding profile, marked by a lack of a clear binding transition (Figure 3B). In contrast, Peptide 2, corresponding to the T-P2-V mutation suggested by both charge optimization and protein design, shows a very sharp transition (Figure 3C), and an apparent Kd of about 0.5 μM, more than a ten-fold improvement over the starting RT–RH peptide. The improvement in binding seen here supports the analysis from both charge optimization and protein design calculations, as the starting threonine side chain was consistently calculated to pay a significant and uncompensated desolvation penalty upon binding due to its buried hydroxyl group with unsatisfied hydrogen bonds. Replacement with a valine side chain eliminates this penalty while maintaining the same capability for packing interactions.

Peptide 1, a triple mutant derived from protein design, exhibited a more modest improvement of 2–3 fold over the starting RT–RH sequence. It contains a mutation to aspartate at P3, estimated to be better in electrostatics and worse in van der Waals than the crystal glutamate, and vice versa for the alternative conformation, as computed from protein design. It also contains an isoleucine mutation at P2, which is functionally equivalent to the valine mutation in terms of electrostatics but contains an additional methyl group expected to make better packing interactions. Finally, it contains a valine to leucine mutation at P2′, which is computed to be equivalent electrostatically but to make better van der Waals interactions upon binding. Overall, it is difficult to attribute this modest binding improvement (less than expected) to any particular residue or combination of residues. Although the isoleucine and leucine mutations were consistently computed to be binding improvements, the aspartate’s predictions were marginal and depended on the conformation of the starting glutamate residue at that position. Because aspartate is tolerated at the P3′ position (as it is in the RT–RH peptide), it would be surprising for aspartate alone to be the explanation for only the small improvement in affinity.

Finally, Peptide 3, containing the diagnostic E-P3-Q mutation, has similar affinity to the starting RT–RH peptide. The glutamine mutant was only predicted to be improved by charge optimization if the structure could not relax to an alternative conformation where the glutamate makes better electrostatic interactions with Arg8B (Figure 1A). This experimental result suggests that the initial glutamate at P3 may interact more closely with Arg8 in solution than is observed in the crystal structure, making it more favorable than it would appear from looking at the crystal structure alone. This emphasizes the importance of building charge-optimization suggested side chains into the structure, because if a prediction were made from electrostatic optimization of the crystal structure alone, this mutation would have been expected to be a substantial binding improvement.

For all peptides studied, the experimentally measured thermodynamics of binding to the inactivated protease is dominated by a large favorable change in entropy, which is counterbalanced by a smaller but unfavorable change in enthalpy. In addition, all designed mutations served to increase the favorable contribution of entropy and worsen the enthalpic contribution to binding. This may not be surprising given that all of the suggested mutations serve to decrease the amount of polar surface area buried upon binding, and in some cases increase the total surface area buried. Because these trends tend to correlate with the hydrophobic effect and solvent release upon binding 54, it may not be surprising that solvent entropy plays a major role in the observed thermodynamics.

Crystal structures of designed complexes

After successfully designing peptides that bind tighter to inactivated HIV-1 protease, two important questions arise. The first is whether or not the structures predicted by the protein design methodology are an accurate representation of what is occurring experimentally. The second, more fundamental to the issue of resistance in HIV protease, is if there exist differences in the way that higher affinity peptides bind to inactivated protease as compared to the substrate peptides. If substantial differences were found, it would be important to consider mimicking these improved interactions when designing inhibitors that resemble the substrate envelope in an effort to avoid resistance. To address these questions, the crystal structures of the three designed complexes were experimentally determined, with crystallographic statistics outlined in Table III.

Table III.

Crystallographic statistics for the three RT–RH variant complexes. Statistics for the corresponding previously determined RT–RH complex 13 are also presented for comparison.

| Structure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | ||||

| RT–RH | Peptide 1 | Peptide 2 | Peptide 3 | |

| Peptide Sequence | GAETF*YVDGA | GADIF*YLDGA | GAEVF*YVDGA | GAQTF*YVDGA |

| PDB ID | 1KJG | 2NXD | 2NXL | 2NXM |

| Data Collection | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.25 |

| Temperature | RT | Cryo | Cryo | Cryo |

| Space Group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| a (Å) | 51.3 | 51.2 | 50.9 | 51.0 |

| b (Å) | 58.8 | 57.6 | 57.5 | 58.5 |

| c (Å) | 62.0 | 61.5 | 61.9 | 61.7 |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Total Reflections | 60432 | 53438 | 54458 | 30202 |

| Unique Reflections | 13019 | 11909 | 12332 | 8523 |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.0 | 3.4 | 7.1 | 6.5 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.6 | 92.7 | 95.8 | 91.0 |

| I/σI | 7.6 | 21.2 | 12.5 | 10.3 |

| Crystallographic Refinement | ||||

| R (%) | 18.4 | 19.5 | 16.0 | 18.7 |

| Rfree (%) | 22.6 | 25.7 | 21.6 | 24.4 |

| Sigma Cutoff | None | None | None | None |

| RMSD in: | ||||

| Bond Lengths (Å) | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Bond Angles (Å) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

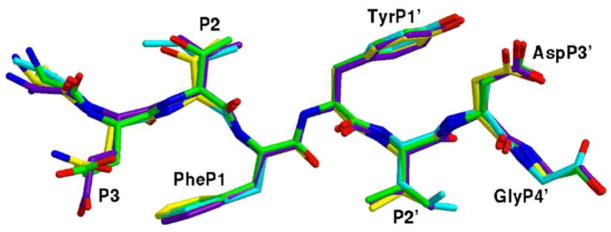

The three-dimensional arrangement and topology for the protease and the three designed peptides were similar to other peptide–inactivated protease complexes 13. The 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc maps clearly revealed the peptide locations with the exception of certain side-chain atoms of Peptide 1. The electron density for the Asp-P3 and Asp-P3′ side chains is absent and Leu-P2′ had to be modeled for the best stereochemistry as the density is ambiguous. Nevertheless, the backbone could be traced unambiguously for Peptide 1 and most of the side chains of Peptide 2 and Peptide 3 were also located. The peptides share high structural homology (Figure 4) with the starting RT–RH peptide.

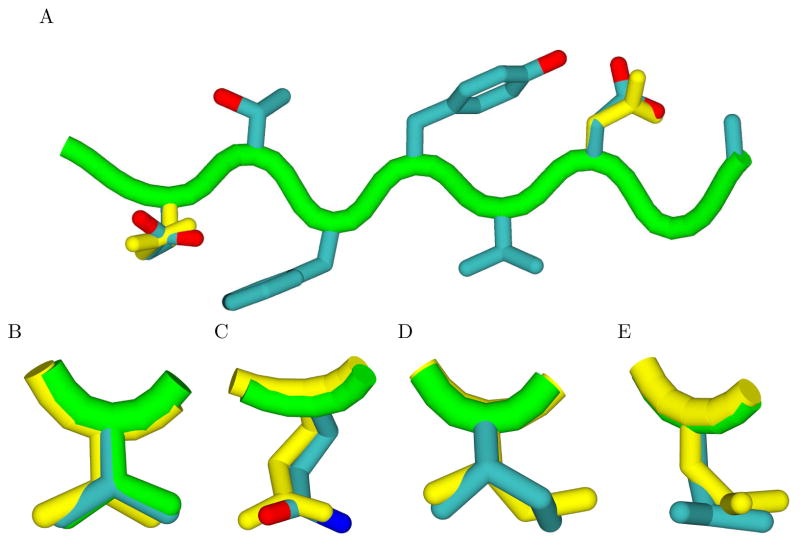

Figure 4.

Superposition of the crystal structures for the RT–RT peptide (green), Peptide 1 (cyan), Peptide 2 (purple), and Peptide 3 (yellow) exhibits structural similarity. This figure was prepared with Midas Plus 85.

Peptide–protease hydrogen bonds were computed for all three designed peptide complexes and compared with the reference RT–RH structure (Table S1, Supplementary Materials). Each of the peptides exhibit 14–17 hydrogen bonds out of which 13 are completely conserved among the four structures. Also, 11 of these 13 conserved hydrogen bonds are also conserved across all the D25N-substrate complexes 13. The conserved hydrogen bonds found among the RT–RH and its analog structures are shown (Figure S1, Supplementary Materials). The differences in hydrogen bonds between the starting and modified RT–RH complexes were examined. The most striking change was observed for the Peptide 1 complex. It exhibits 3 hydrogen bonds less (14 hydrogen bonds total) than the other three complexes (17 hydrogen bonds total) (Table S1, Supplementary Materials). Also, because the electron density for Asp-P3 and Asp-P3′ is ambiguous in this peptide, it is possible that they may not make stable hydrogen bonds.

In the Peptide 2 complex, the side chain of Glu-P3 undergoes conformational change and forms a new salt bridge with Arg8B (Figure 1C) not found in the crystal structure of the starting RT–RH peptide. This interaction is very similar to the alternative conformation favored computationally for the Glu-P3 side chain in the initial RT–RH complex (Figure 1A,C). These results suggest that the multiple conformations proposed by computation for the Glu-P3 residue are justified, and that the energetic barrier between these structures may be low. It is also possible that the new hydrogen-bonding interaction plays a role in the improved affinity observed for Peptide 2, and may help to explain why the suggested Gln mutation at P3 might not be a binding improvement, as Gln-P3 is also capable of hydrogen bonding with Arg8B. Also, in the Peptide 2 complex, an existing salt bridge found in the reference RT–RH complex between Asp-P3′ and Arg8A, is absent. Overall, these changes in hydrogen bonding for Peptide 2 may imply that the unprimed side forms stronger interactions than in the RT–RH substrate peptide complex.

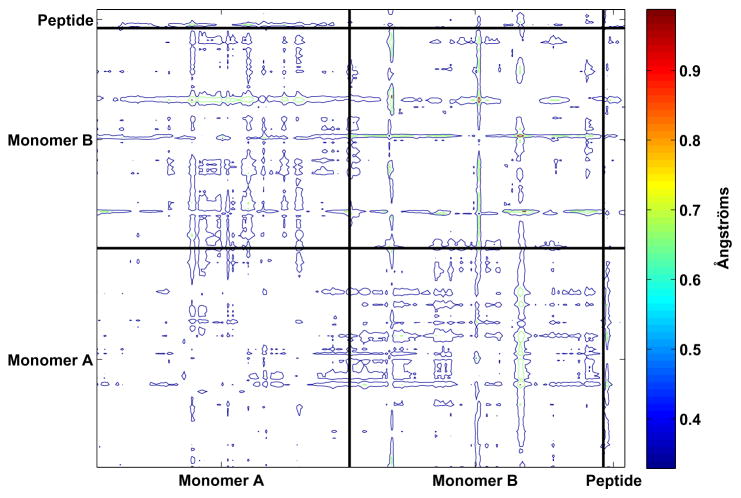

In order to determine whether there were fundamental differences between the way that the tightest-binding designed mutant (Peptide 2) and the initial RT–RH peptide bound to the protease, a Cα double difference plot was constructed to identify regions of the protein backbone that deviated between the two complexes (Figure 5). Overall, few regions exhibited significant deviations, and the largest differences were associated with surface protease residues, such as Gly17, Gly51, and Cys67, where flips of the peptide bond geometry occurred. A closer examination of the residues lining the active site reveals that the backbone of Ile50 adopts slightly different relative positions in the two structures, most likely due to an alternative selection of side-chain rotamers. There are some slight positional changes between the A and B monomers and relative movement of the peptide N-terminus, however no evidence of large-scale, concerted conformational motion was found. These results suggest that the structures of the natural substrates are sufficient for defining a substrate envelope that may be a useful guideline for designing tight-binding protease inhibitors that are less likely to induce drug-resistance mutations.

Figure 5.

Double difference plot between Cα atoms in the crystal structures of the RT-RH peptide complex and the tightest-binding designed complex (Peptide 2). The largest deviations correspond to the surface residues 17, 51, and 67 in monomer B.

Comparison of predicted to experimental structures

The crystal structures for the designed complexes were also used to gauge the accuracy of the structural predictions from the protein design methodology. The structure of each designed complex was compared to the predicted structure by aligning the alpha carbons of the protease and examining the deviation between the predicted and experimental peptide side-chain geometries.

For reference, the crystal structure of the initial RT–RH peptide complex, from which all calculations were based, compares favorably with the corresponding structure as generated in protein design. For all but two of the side chains, the protein design methodology selected the crystal conformation as optimal. For the two remaining peptide side chains, Glu-P3 and Asp-P3′, conformations were selected from the rotamer library that were close to the crystal geometry (Deviations — Glu-P3: chi;1 10°, χ2 12°, χ3 43°; Asp-P3′: χ1 23°, χ2 56°) (Figure 6A). In addition, the computed structure for the protease remained very close to that of the crystal. Overall, the total root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) for designed side chains between the crystallographic and designed complexes for the starting RT–RH sequence was 0.6 Å.

Figure 6.

Comparison between predicted and experimentally determined structures. For reference, comparisons are made between the designed (atom colors) and crystal structure (yellow) for the starting RT–RH peptide sequence (A). Crystal rotamers were selected by design at all but two residues. Designed mutation to valine at P2 in Peptide 2 (atom colors) has good structural agreement with both the crystal structure of the mutant (yellow) and the wild-type threonine (green) (B). The glutamate to glutamine structural prediction at P3 (atom colors) for Peptide 3 also agrees well with its experimental structure (yellow) (C). Mutations at P2 to isoleucine (D) and P2′ to leucine (E) in Peptide 1 occupy similar volumes with some structural differences. This figure was prepared with VMD 83 and Raster3D 84.

The computationally predicted structure for Peptide 2 agrees very well with the experimental structure, with a negligible difference in side-chain geometry. As expected, the valine mutation is directly superimposed on the original threonine (Figure 6B), confirming the hypothesis that this is a shape-conserving mutation. Although Peptide 3 did not show an improvement in binding, it was not necessarily due to an error in modeling the bound state as the predicted and experimental conformations of the P3 glutamine mutation are very similar. The side-chain dihedral angles are virtually identical, and the only differences in their placement are due to small changes in the backbone geometry (Figure 6C).

A comparison of the predicted and experimental structures for Peptide 1 shows less agreement. Although much of the side-chain density is missing from the crystal structure of the Peptide 1 complex, two out of the three designed side chains are visible. The modeled isoleucine mutation at the P2 position differs from the crystal by approximately 30 degrees in the first χ angle for an overall side-chain RMSD of 0.8 Å (Figure 6D). Although a rotamer closer to the crystal structure did exist in the search space, its energy was predicted to be only 0.2 kcal/mol higher than that of the selected conformation, indicative of a relatively flat energy landscape. Mutation at the P2′ position to leucine was also visible in the structure, and its predicted geometry was somewhat different from the experimental observation. The first χ angle deviates by 41° as the crystal side chain adjusts to make closer packing interactions with the backbone of Asp30B, rather than the Ile50A side chain as found by protein design (Figure 6E). In the rotamer library used for design, there did exist a leucine conformation slightly closer to the observed crystal structure (20° closer in χ1), but it was not selected because computed packing interactions with the Ile50A side chain were better in the chosen geometry.

Conclusion

Two computational techniques to improve binding affinity were successfully applied to design peptide sequences that bind tighter to inactivated (D25N) HIV-1 protease in an effort to obtain thermodynamic and structural data to aid in the understanding of substrate binding and drug resistance. Charge optimization techniques identified two residues in the tightest binding natural substrate peptide (RT–RH), Glu-P3 and Thr-P2, that provided opportunities to improve electrostatic complementarity, suggesting several mutations to enhance binding or serve as diagnostics for elucidating energetic contributions of the original residues. Computational protein design techniques, which allow for side-chain flexibility and shape changing mutations, confirmed the predictions from charge optimization, demonstrated the limitations of charge optimization’s fixed geometry model, and suggested additional substitutions to further improve packing interactions at the interface.

Three designed peptides were tested for inactive protease binding through isothermal titration calorimetry. A single threonine to valine substitution at the P2 position, heavily suggested by calculation, led to more than a ten-fold improvement in binding, which is a considerable improvement given the small perturbation. In addition, a triple mutant sequence derived from protein design led to a 2–3 fold improvement. Substitution of glutamine for glutamate at the P3 position suggests that the starting residue may be more favorable than calculated from the crystal structure alone. It is important to note that the three designed peptides presented here were the only peptides tested experimentally, and that only the data presented in this work was used to select the designed peptides.

Thermodynamic measurements of peptide binding revealed that binding to the inactive protease was heavily entropically driven, most likely due to release of solvent from the active site upon binding. Mutations suggested by computation tended to replace polar groups with less polar groups and increase the total amount of buried hydrophobic surface area, resulting in a further increase in the entropic contribution. These results may be important in understanding resistance, as peptides that bind primarily through the hydrophobic effect without making strongly orientation dependent interactions may be better suited to adapt to resistance mutations where less flexible small-molecule inhibitors cannot.

Crystal structures of the designed peptide complexes, in addition to validating structural predictions from computation, revealed only minor differences between complexes of the natural RT–RH substrate and the tightest-binding designed peptide (Peptide 2). These findings suggest that using the geometries of natural substrates is sufficient to define envelopes that represent the consensus volume of substrates, which may be useful in subsequent drug design efforts to target drug-resistant HIV-1 protease 13,16–19.

An additional application for tighter binding peptides is in the understanding of a more recently identified mechanism of drug resistance against protease inhibitors, substrate co-evolution 15. In cases of highly drug resistant protease, compensatory mutations can arise in the cleavage sites to improve catalytic efficiency. One of the most common of these substrate mutations occurs in the nucleocapsid–p1 site (NC–p1), where an alanine in the P2 position is converted to valine in response to a V82A drug resistance mutation in the protease. This mutation is analogous to the valine P2 mutation predicted and tested to be favorable in the RT–RH background, indicating that substrate co-evolution may serve to increase peptide– protease affinity as well as optimize substrate processing.

Overall, computational design methods have been shown to be a useful tool in discovering tighter binding peptides for an inactivated mutant of HIV-1 protease. These peptides serve to improve our understanding of how peptides bind HIV-1 protease, both structurally and thermodynamically, as well as rationalizing the use of natural substrate structures as models for future drug development.

Materials and Methods

Protein structure preparation

The crystal structure of inactivated (D25N) HIV-1 protease complexed with RT–RH substrate peptide 13 (Protein Data Bank ID 1KJG) was used as the starting point for all calculations. For residues with multiple occupancy, the first conformation was selected except for residues Glu 21A and Glu 35A where the second conformation was selected to improve the hydrogen-bond network. In addition, the ring of His69B was flipped 180° to improve hydrogen bonding. Because the substrate peptide used in the crystal structure had blocked termini, acetyl and methylamide groups were added to the N and C termini of the peptide respectively. All water molecules were removed from the structure except for the five conserved across all protease–substrate complexes 13. Hydrogens were added to the structure using the HBUILD module 55 in the CHARMM computer program 56 with the PARAM22 all-atom parameter set 57. All ionizable residues were left in their standard states at pH 7, with histidines singly protonated on the δ nitrogen.

Continuum electrostatic and charge optimization calculations

All continuum electrostatic calculations were performed using a locally-modified version of the DelPhi computer program 58–61 to solve the linearized Poisson–Boltzmann equation. A dielectric constant of 4 was used for the protein and 80 for water, as well as an ionic strength of 145 mM in the solvent region. The boundary between protein and solvent was represented by a molecular surface computed with a probe radius of 1.4 Å, and an ion-exclusion layer of 2.0 Å surrounded all molecules. Partial atomic charges and radii for continuum electrostatic calculations were taken from the PARSE parameter set 62, and structures derived from protein design calculations were additionally screened using charges and radii from the PARAM19 parameter set 63,64. Electrostatic binding and solvation contributions for protease–peptide complexes designed from charge optimization were calculated using a 257×257×257 cubic grid and a two-stage boundary condition focusing scheme. The complex was placed on the grid such that it occupied first 23% and then 92% of the grid size, where the solved potentials from the lower percent fill were used as boundary conditions for the higher percent fill calculation. This resulted in a final grid spacing of 0.23 Å. In addition, each result was averaged over 10 translations of the complex relative to the grid in order to reduce artifacts from the grid-based representation of atomic charges and the molecular surface. Complexes from protein design calculations were evaluated similarly, except a 129×129×129 grid and only one translation were used due to the large number of structures that needed evaluation. The matrix elements for electrostatic optimization were also computed in a similar fashion, but using a 129×129×129 grid, 10 translations and a three-stage over-focusing scheme of 23%, 92%, and 184%, where the 184% calculation was centered on the single atom charged when computing a row of the ligand desolvation matrix.

Charge optimization was performed as previously described 26–28,30–34,36, using locally written software. Each side chain of the peptide had its partial atomic charges independently optimized to maximize the rigid electrostatic binding free energy of the peptide to the inactivated protease. Each peptide side chain was constrained to a total net charge of −1e, 0e, and +1e in separate computations, while simultaneously requiring that no atom exceed a charge magnitude of 0.85e. In an additional calculation, each side chain was constrained to have all zero partial atomic charges, thus simulating a hydrophobic isostere. For each constraint set, the energy difference between the optimal and parameterized charge distribution was determined by using the resulting charges with the optimization objective function 30,34,36. All constrained optimizations were carried out using the software package LOQO 65,66.

Modeling of peptide mutations from charge optimization

Peptide mutations suggested from charge optimization were built into the RT–RH peptide complex structure using the CHARMM computer program 56 and the PARAM22 all-atom parameter set 57, using a distance-dependent dielectric constant of 4r. Two procedures were used to model each mutant structure. The first aimed to find a low-energy structure for each mutation, and all mutant side-chain dihedral angles were enumerated every 30 degrees. Each enumerated side-chain conformation was then minimized until convergence, with the rest of the protease and peptide held fixed. The lowest energy minimized structure was selected to represent the mutation. Alternatively, because charge optimization suggests shape-conserving mutations, the mutant side chain was built on top of the starting crystal structure using the dihedral angles common to both side chains.

Protein design calculations

Through the use of locally developed protein design software, the central eight positions of the peptide (P4–P4′) were allowed to mutate to and select a conformation for any of the 20 standard amino acids except proline. Histidines were modeled with all three possible protonation states. In addition, the side chains of active-site protease residues 8, 23, 25, 29, 30, 32, 45, 47, 50, 53, 82 and 84 in both monomers were allowed to change their conformation but not their identity. In all cases, the protein backbone was held fixed. Side-chain conformations were modeled discretely from the backbone independent rotamer library of Dunbrack and Karplus (May 2000) 67, but with additional rotamers ± 10° about the first two χ angles. In addition, the exact structure of the crystal side chain was permitted as a choice in the design. The objective function minimized in the protein design procedure was the energy of the bound complex. A model of the peptide unfolded state was not used in these calculations because short peptides tend not to form stable structures 68. The energy of the bound complex was estimated using an energy function pairwise additive in side-chain conformations, consisting of an electrostatics term with a distance-dependent dielectric constant of 4r, a van der Waals interaction term, and internal dihedral energy as computed by CHARMM 56 using a modified version of the PARAM19 parameter set 63,64 with included aromatic and sulfhydryl hydrogens. For each single, double, and triple mutant peptide sequence, the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) was identified for the complex using dead-end elimination (DEE) 50,52,53 and A* 51. These structures were then screened for predicted improvements in binding as described below.

Calculation of binding energetics

The binding free energy of peptide-inactivated protease complexes was estimated using a rigid binding model, where the difference between solvation energy in the bound and unbound state was added to the vacuum (ε = 4) interaction energy in the bound state. Vacuum binding energies were computed with CHARMM 56, using the PARAM22 parameter set 57, for mutants derived from charge optimization. For mutants suggested from protein design, a modified version of the united-atom PARAM19 parameter set 63,64, where aromatic and sulfhydryl hydrogens were added, was used for vacuum energies. In addition, mutants from protein design were also screened with the AMBER united-atom parameter set 69. Solvation energies were computed using a Poisson–Boltzmann/Surface Area (PBSA) model 62. The linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation was solved with a locally-modified version of DelPhi as described above, and CHARMM was used to compute the analytical surface area. Parse 62 radii and charges were used for all structures, and designed complexes from protein design were additionally screened using PARAM19 radii and charges. To compute the hydrophobic contribution to solvation, the surface area was multiplied by 5 cal/mol/Å2 62. To avoid possible scaling problems between the electrostatic/solvation and van der Waals components of the estimated binding energy, mutations considered as improvements were required to be better than the starting structure in both of these components of the energy function.

Substrate peptides

Decameric peptide variants of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase-RNase H substrate (RT–RH) with sequences GADIF*YLDGA (Peptide 1), GAEVF*YVDGA (Peptide 2), and GAQTF*YVDGA (Peptide 3) were prepared as previously described 13. The peptides were purchased from 21st Century Biochemicals, Marlboro, MA.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Thermodynamic parameters of peptide binding were determined using an isothermal titration calorimeter, VP-ITC (MicroCal Inc., Northampton, MA). The buffer used for all protease and peptide solutions consisted of 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5.0, 2% DMSO, and 2 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP). A 1-mM solution of each peptide was directly titrated into a solution of 30–70 μM D25N HIV-1 protease in 10 μl aliquots. The experiments were performed at 15° C. Each experiment was repeated at least in triplicate. Data were processed using the Origin 7 software package from MicroCal.

Mutagenesis, protein purification, and crystallization

A previously described method 15,70 was followed throughout all wet chemistry experiments. A synthetic gene of HIV-1 protease, optimized for Escherichia coli codon usage was used as the starting template for mutagenesis to introduce the D25N substitution. This isosteric mutation inactivates the protease, and it was made using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The purified inactive protease, in 50% acetic acid, was then refolded by rapid 10-fold dilution into a mixture of 0.05 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 10% glycerol, 5% ethylene glycol, and 5 mM dithiothreitol (refolding buffer) kept over ice. The diluted protein was concentrated and dialyzed to remove residual acetic acid. Protease used for crystallization was further purified using a Pharmacia Superdex 75 FPLC column equilibrated with refolding buffer. Crystals were grown by the hanging drop, vapor diffusion method. Stock solutions (25 mM) of substrate peptides used for co-crystallization were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide. The protein concentration was approximately 1 mg/ml. Small crystals started appearing after 3–7 days with the longest length between 0.1 and 0.2 mm.

Crystallographic data collection

The crystals were flash frozen over a nitrogen stream and intensity data were collected on an in-house Rigaku X-ray generator with a R-axis IV image plate. Frames were indexed using Denzo and scaled using ScalePack 71,72. Complete data collection statistics are listed in Table III.

Structure solution and crystallographic refinement

The crystal structures were solved and refined using the programs within the CCP4i interface 73. Structure solution was carried out by molecular replacement using the program AMoRe 74. The crystal structure of a wild-type protease complexed to the inhibitor TMC-114 (Protein Data Bank ID 1T3R) 16 was used as the starting model. The molecular replacement phases were further improved using ARP/wARP 75 by building solvent molecules into the unaccounted regions of electron density. Subsequently, interactive model building was carried out using O 76. Initial 2Fo − Fc and Fo − Fc maps indicated the positions of RT–RH substrate variants. Conjugate gradient refinement using Refmac5 77 was performed by incorporating the Schomaker and Trueblood tensor formulation of TLS (translation, libration, screw-rotation) parameters 78–80. The working R-factor (Rwork) as well as the cross-validated version (Rfree) were assessed using Procheck 81 at the end of each refinement round. The refinement statistics are also shown in Table III.

Analysis of and comparison to experimental structures

The double difference plot comparing the structures of the tightest-binding mutant and original RT–RH peptide complexes was computed by determining the interatomic distances between all pairs of Cα atoms in each structure. The difference between these two distance matrices was subsequently calculated, and every difference element was replaced by its absolute value.

Crystal structures for the designed complexes were compared to predicted structures by performing a best RMSD fit between all Cα atoms of just the protease using the program PROFIT 82. The resulting RMS difference between peptide side-chain conformations was subsequently calculated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Karplus for the charmm computer program package, Barry Honig for the DelPhi computer program package, and R. J. Vanderbei for LOQO. This work was partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (GM065418 and GM066524).

References

- 1.Larder BA, Kemp SD. Multiple mutations in HIV-1 reverse-transcriptase confer high-level resistance to zidovudine (AZT) Science. 1989;246:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.2479983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffin JM. HIV population-dynamics in-vivo: Implications for genetic-variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science. 1995;267:483–489. doi: 10.1126/science.7824947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Condra JH, Schleif WA, Blahy OM, Gabryelski LJ, Graham DJ, Quintero JC, Rhodes A, Robbins HL, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Titus D, Yang T, Teppler H, Squires KE, Deutsch PJ, Emini EA. In-vivo emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple protease inhibitors. Nature. 1995;374:569–571. doi: 10.1038/374569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debouck C. The HIV-1 protease as a therapeutic target for AIDS. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:153–164. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molla A, Korneyeva M, Gao Q, Vasavanonda S, Schipper PJ, Mo HM, Markowitz M, Chernyavskiy T, Niu P, Lyons N, Hsu A, Granneman GR, Ho DD, Boucher CAB, Leonard JM, Norbeck DW, Kempf DJ. Ordered accumulation of mutations in HIV protease confers resistance to ritonavir. Nat Med. 1996;2:760–766. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flexner C. HIV protease inhibitors. New Eng J Med. 1998;338:1281–1292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804303381808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croteau G, Doyon L, Thibeault D, McKercher G, Pilote L, Lamarre D. Impaired fitness of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with high-level resistance to protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1997;71:1089–1096. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1089-1096.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Picado J, Savara LV, Sutton L, D’Aquila RT. Replicative fitness of protease inhibitor-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3744–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3744-3752.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber IT, Wu J, Adomat J, Harrison RW, Kimmel AR, Wondrak EM, Louis JM. Crystallographic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus 1 protease with an analog of the conserved CA–p2 substrate — Interactions with frequently occurring glutamic acid residue at P2′ position of substrates. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahalingam B, Louis JM, Hung J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Structural implications of drug-resistant mutants of HIV-1 protease: High-resolution crystal structures of the mutant protease/substrate analogue complexes. Proteins. 2001;43:455–464. doi: 10.1002/prot.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tie YF, Boross PI, Wang YF, Gaddis L, Liu FL, Chen XF, Tozser J, Harrison RW, Weber IT. Molecular basis for substrate recognition and drug resistance from 1.1 to 1.6 ångstrom resolution crystal structures of HIV-1 protease mutants with substrate analogs. FEBS J. 2005;272:5265–5277. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. How does a symmetric dimer recognize an asymmetric substrate? A substrate complex of HIV-1 protease. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:1207–1220. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, Schiffer CA. Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: Analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes. Structure. 2002;10:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00720-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, King NM, Schiffer CA. Viability of a drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease variant: Structural insights for better antiviral therapy. J Virol. 2003;77:1306–1315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1306-1315.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, King NM, Schiffer CA. Structural basis for coevolution of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid–p1 cleavage site with a V82A drug-resistant mutation in viral protease. J Virol. 2004;78:12446–12454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12446-12454.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Wigerinck P, de Bethune MP, Schiffer CA. Structural and thermodynamic basis for the binding of TMC114, a next-generation human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. J Virol. 2004;78:12012–12021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12012-12021.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Schiffer CA. Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: Lessons from HIV-1 protease. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuske S, Sarafianos SG, Clark AD, Ding JP, Naeger LK, White KL, Miller MD, Gibbs CS, Boyer PL, Clark P, Wang G, Gaffney BL, Jones RA, Jerina DM, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Structures of HIV-1 RT-DNA complexes before and after incorporation of the anti-AIDS drug tenofovir. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:469–474. doi: 10.1038/nsmb760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkpatrick P. Antiviral drugs: Inside the envelope. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:100–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bardi JS, Luque I, Freire E. Structure-based thermodynamic analysis of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6588–6596. doi: 10.1021/bi9701742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luque I, Todd MJ, Gomez J, Semo N, Freire E. Molecular basis of resistance to HIV-1 protease inhibition: A plausible hypothesis. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5791–5797. doi: 10.1021/bi9802521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velazquez-Campoy A, Todd MJ, Freire E. HIV-1 protease inhibitors: Enthalpic versus entropic optimization of the binding affinity. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2201–2207. doi: 10.1021/bi992399d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyland LJ, Tomaszek TA, Meek TD. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 protease. 2 Use of pH rate studies and solvent kinetic isotope effects to elucidate details of chemical mechanism. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8454–8463. doi: 10.1021/bi00098a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamazaki T, Nicholson LK, Torchia DA, Wingfield P, Stahl SJ, Kaufman JD, Eyermann CJ, Hodge CN, Lam PYS, Ru Y, Jadhav PK, Chang CH, Weber PC. NMR and X-ray evidence that the HIV protease catalytic aspartyl groups are protonated in the complex formed by the protease and a nonpeptide cyclic urea-based inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:10791–10792. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trylska J, Antosiewicz J, Geller M, Hodge CN, Klabe RM, Head MS, Gilson MK. Thermodynamic linkage between the binding of protons and inhibitors to HIV-1 protease. Protein Sci. 1999;8:180–195. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee LP, Tidor B. Optimization of electrostatic binding free energy. J Chem Phys. 1997;106:8681–8690. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee LP, Tidor B. Optimization of binding electrostatics: Charge complementarity in the barnase–barstar protein complex. Protein Sci. 2001;10:362–377. doi: 10.1110/ps.40001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee LP, Tidor B. Barstar is electrostatically optimized for tight binding to barnase. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:73–76. doi: 10.1038/83082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sulea T, Purisima EO. Optimizing ligand charges for maximum binding affinity. A solvated interaction energy approach. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:889–899. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kangas E, Tidor B. Optimizing electrostatic affinity in ligand-receptor binding: Theory, computation, and ligand properties. J Chem Phys. 1998;109:7522–7545. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kangas E, Tidor B. Charge optimization leads to favorable electrostatic binding free energy. Phys Rev E. 1999;59:5958–5961. doi: 10.1103/physreve.59.5958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kangas E, Tidor B. Electrostatic specificity in molecular ligand design. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:9120–9131. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kangas E, Tidor B. Electrostatic complementarity at ligand binding sites: Application to chorismate mutase. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:880–888. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green DF, Tidor B. Escherichia coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase is electrostatically optimization for binding of its cognate substrates. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:435–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sims PA, Wong CF, McCammon JA. Charge optimization of the interface between protein kinases and their ligands. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1416–1429. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green DF, Tidor B. Design of improved protein inhibitors of HIV-1 cell entry: Optimization of electrostatic interactions at the binding interface. Proteins. 2005;60:644–657. doi: 10.1002/prot.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilson MK. Sensitivity analysis and charge-optimization for flexible ligands: Applicability to lead optimization. J Chem Theory Comput. 2006;2:259–270. doi: 10.1021/ct050226y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dahiyat BI, Mayo SL. Protein design automation. Protein Sci. 1996;5:895–903. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Street AG, Mayo SL. Computational protein design. Struct Fold Des. 1999;7:R105–R109. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saven JG. Combinatorial protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:453–458. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahiyat BI, Sarisky CA, Mayo SL. De novo protein design: Towards fully automated sequence selection. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:789–796. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dantas G, Kuhlman B, Callender D, Wong M, Baker D. A large scale test of computational protein design: Folding and stability of nine completely redesigned globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:449–460. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00888-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harbury PB, Plecs JJ, Tidor B, Alber T, Kim PS. High-resolution protein design with backbone freedom. Science. 1998;282:1462–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy. Science. 2003;302:1364–1368. doi: 10.1126/science.1089427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhlman B, O’Neill JW, Kim DE, Zhang KYJ, Baker D. Conversion of monomeric protein L to an obligate dimer by computational protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10687–10691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181354398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shifman JM, Mayo SL. Modulating calmodulin binding specificity through computational protein design. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:417–423. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Havranek JJ, Harbury PB. Automated design of specificity in molecular recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:45–52. doi: 10.1038/nsb877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Looger LL, Dwyer MA, Smith JJ, Hellinga HW. Computational design of receptor and sensor proteins with novel functions. Nature. 2003;423:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joachimiak LA, Kortemme T, Stoddard BL, Baker D. Computational design of a new hydrogen bond network and at least a 300-fold specificity switch at a protein– protein interface. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desmet J, Demaeyer M, Hazes B, Lasters I. The dead-end elimination theorem and its use in protein side-chain positioning. Nature. 1992;356:539–542. doi: 10.1038/356539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]