Abstract

We examined the transduction efficiency of different adeno-associated virus (AAV) capsid serotypes encoding for green fluorescent protein (GFP) flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats in the nonhuman primate basal ganglia as a prelude to translational studies, as well as clinical trials in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD). Six intact young adult cynomolgus monkeys received a single 10 µl injection of AAV2/1-GFP, AAV2/5-GFP, or AAV2/8-GFP pseudotyped vectors into the caudate nucleus and putamen bilaterally in a pattern that resulted in each capsid serotype being injected into at least four striatal sites. GFP immunohistochemistry revealed excellent transduction rates for each AAV pseudotype. Stereological estimates of GFP+ cells within the striatum revealed that AAV2/5-GFP transduces significantly higher number of cells than AAV2/8-GFP (P < 0.05) and there was no significant difference between AAV2/5-GFP and AAV2/1-GFP (P = 0.348). Consistent with this result, Cavalieri estimates revealed that AAV2/5-GFP resulted in a significantly larger transduction volume than AAV2/8-GFP (P < 0.05). Each pseudotype transduced striatal neurons effectively [>95% GFP+ cells colocalized neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN)]. The current data suggest that AAV2/5 and AAV2/1 are superior to AAV2/8 for gene delivery to the nonhuman primate striatum and therefore better candidates for therapeutic applications targeting this structure.

Introduction

Gene therapy provides a novel means to deliver proteins to the central nervous system in a site-specific manner. Among the many different viral delivery systems, the adeno-associated virus (AAV) has become a common vector of choice to deliver genes aimed at modeling neurodegenerative diseases or delivering therapeutic molecules. AAV is a 20–25 nm nonpathogenic human parvovirus.1 Among over 100 identified serotypes of AAV capsid, AAV1–AAV10 are currently being developed as recombinant vectors for gene therapy applications because of their unique capsid-associated tropism for specific receptors that may confer tissue specificity. AAV vectors have a wide range of host and cell type tropism and transduce both dividing and nondividing cells in vitro and in vivo with high stability of transgene expression.2

The nonpathogenic and persistent long-term nature of AAV infection, combined with its wide range of infectivity, has not only made this virus a useful gene transfer vector but also a promising candidate vector for the gene therapy. Recombinant vectors based on AAV2 capsid proteins have been developed as a gene therapy tool and tested in preclinical trials for almost 25 years with an excellent safety profile. This serotype has been shown to transduce neurons in almost all regions of the brain.3,4 Thus, AAV2 vectors are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for central nervous system diseases.5,6,7 Specifically, open-label studies in Parkinson's disease (PD) have successfully delivered the potentially therapeutic molecules using an AAV2 vector with few, if any side effects, suggesting that in vivo gene therapy in the adult human brain can be safe.8,9,10,11 Also, recent studies have shown that AAV vectors are useful to generate various animal models for neurodegenerative diseases in rodents and nonhuman primates.12,13,14,15,16,17

Due to variation in the amino-acid composition of the capsid protein(s), various serotypes differ in which receptors they utilize for cell entry and the epitopes recognized by the immune system. By simply changing the serotypes, the transduction efficiency of certain cell types may be significantly improved and may preferentially escape from immune surveillance. Several of these serotypes have been used in in vivo central nervous system transgene studies preclinically.18,19,20,21,22,23,24 Although AAV2 has been used in most studies including the clinical trials, other serotypes have the potential to provide improved transduction efficiency and spread of the vector from the injection sites.19,23

In addition, neutralizing antibodies against wild-type AAV2 have been detected in a significant portion of the human population that may encumbrance the application of AAV2 vector in clinical gene therapy applications.25,26,27 Specifically, AAV1 and AAV5 serotypes have more favorable properties for reproducible production at high titers. Specific identified cell tropism, high transduction efficiency, and low immune response are the major criteria for the AAV serotype to be considered as the future gene therapy vector. The present study evaluates the transduction efficiency and cell tropism as well as safety of AAV serotypes AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 in the basal ganglia of nonhuman primates. We now present data showing that AAV1 and AAV5 serotypes yield high transduction rates and neuronal tropism in the primate brain leading to the serious consideration as a future gene therapy vectors to treat neurodegenerative disorders like PD.

Results

Transduction pattern of different pseudotyped AAV (AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8) after vector injection into the primate caudate and putamen

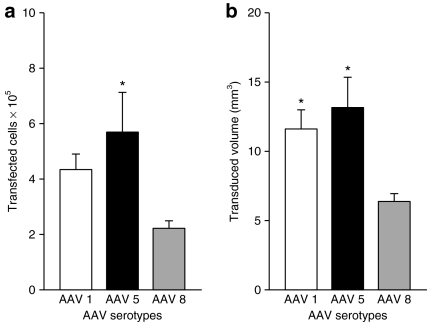

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) immunohistochemistry revealed robust GFP expression in the cell bodies and fibers in the striatal regions for all AAV pseudotypes. At 3 months after AAV injection, numerous GFP positive (GFP+) neurons were observed around the injection site (Figures 1 and 2). To quantitatively compare the transduction efficiency of each serotype, optical fractionator–based stereological cell counts were performed. The data from the unbiased estimation of the GFP+ cell population in caudate and putamen regions, shown in the Figure 3a, revealed 434,020 ± 56,173, 569,341 ± 143,415, and 222,199 ± 27,049 GFP+ cells (mean ± SEM) from the injection of AAV-GFP pseudotypes 2/1, 2/5, and 2/8, respectively. In general, all three pseudotypes provide excellent transduction with high numbers of labeled cells. AAV2/5 transduced more striatal cells than rAAV2/8 (one-way analysis of variance: F(2, 21) = 3.604; P < 0.05 post hoc Bonferroni; P < 0.04). In addition, there was no significant difference between the estimated number of cells transduced by AAV2/5 and AAV2/1 (P = 0.348). There was no significant difference seen between AAV2/1 and AAV2/8 (P > 0.05).

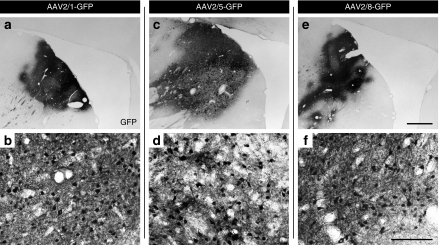

Figure 1.

GFP expression in the caudate nucleus after AAV2/1, AAV2/5, or AAV2/8 injection. Low- and high-power photomicrographs through the caudate nucleus of GFP+ delivered via (a,b) AAV2/1, (c,d) AAV2/5, and (e,f) AAV2/8 vectors demonstrating the robust transduction of striatal cells for each serotype. Note the intense neuronal and fiber network for all pseudotypes, although the fiber network was slightly diminished with AAV2/5. Bar in e and f represents the magnifications of 1 mm and 100 µm, and applies to a,c,e and b,d,f, respectively. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

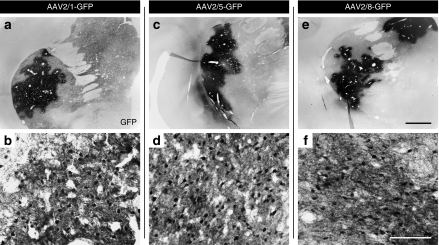

Figure 2.

GFP expression in the putamen after AAV2/1, AAV2/5, or AAV2/8 injection. Low- and high-power photomicrographs through the putamen of GFP+ delivered via (a,b) AAV2/1, (c,d) AAV2/5, and (e,f) AAV2/8 vectors demonstrating the robust transduction of striatal cells for each pseudotype. Bar in e and f represents the magnifications of 2 mm and 100 µm, and applies to a,c,e and b,d,f, respectively. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure 3.

Quantification of GFP+ cells and their distribution volume around the injection sites in caudate and putamen. (a) Stereological estimates of the number of GFP+ stained cells 3 months following intrastriatal AAV2/1-GFP, AAV2/5-GFP, and AAV2/8-GFP. One-way analysis of variance F(2, 21) = 3.604, P = 0.047, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. *P = 0.047. (b) Quantification of GFP+ stained cell volume in the striatum 3 months following intrastriatal AAV1-GFP, AAV5-GFP, and AAV-8 GFP administration. *P < 0.05. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Transduction pattern after injection of AAV2/1 and AAV2/8 in the substantia nigra

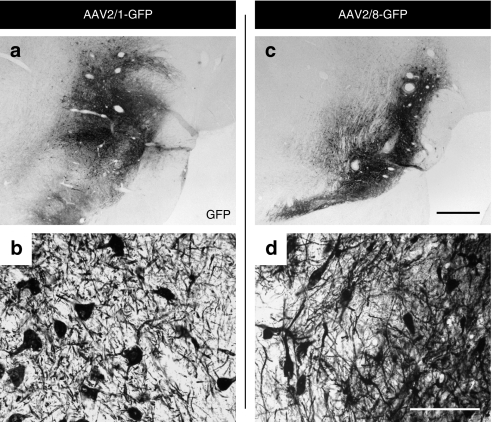

GFP immunohistochemistry showed widespread and intense GFP expression throughout the substantia nigra (Figure 4). Qualitatively, it appeared that cells within the pars compacta and pars reticulata regions were transduced with equal efficiency. Microscopic analysis revealed comparable transduction rates for both AAV2/1 and AAV2/8 serotypes. Stereological counting revealed that AAV2/1 and AAV2/8 transduced 83,402 ± 17,809 and 68,826 ± 17,501 nigral cells, respectively (no group differences, P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

GFP expression in nigra after intranigral AAV2/1 or AAV2/8 injections. Robust expression of GFP+ in the substantia nigra 3 months following (a,b) AAV1-GFP and (c,d) AAV8-GFP. Bar in c and d represents the magnifications of 1 mm and 50 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

The spread of AAV-GFP in the striatum

To estimate the three-dimensional distribution of transgene by each serotype, the volume of individual caudate and putamen transduced for GFP+ cells was quantified. The mean volume for GFP+ cells from a single 10 µl AAV2/1-GFP injection resulted (Figure 3b) 11.6 ± 1.4 mm3. This value was similar to what was observed with a similarly titered injection of AAV2/5-GFP of a similar volume 13.2 ± 2.2 mm3. Although AAV8 also transduced a large area in caudate and putamen with a mean value of 6.4 ± 0.6 mm3, the value was significantly less than what was seen with AAV2/1 and AAV2/5 (P < 0.05 for each).

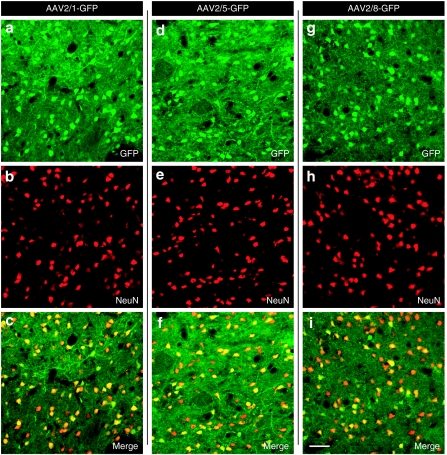

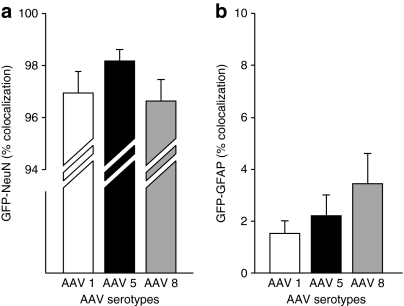

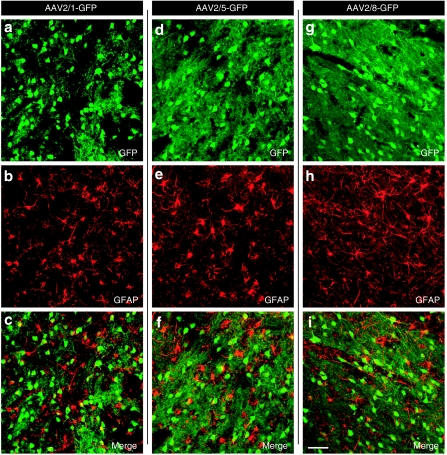

Characterization of cell types transduced by different AAV pseudotypes

One of our overarching goals was to understand the different tropism for the different AAV pseudotypes in the nonhuman primate brain (Figures 5–7). Confocal microscopic analyses revealed extensive colocalization of GFP with the neuronal marker NeuN for each serotype (Figure 5). In contrast, only rare GFAP+ astrocytes express GFP after AAV injections regardless of the pseudotype employed (Figure 6). The qualitative observations were supported by the quantitative evidence. AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 demonstrated 97, 98, and 95% colocalization in neurons but 1.3, 1.5, and 2.7% in astrocytes, respectively (P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Transduction of neuronal cells by AAV pseudotypes. Confocal images (a,d,g) shows GFP+, cells (green color), extensively colocalized with (b,e,h) NeuN (red color) in the striatum as demonstrated by (c,f,i) the merged image (the yellow cells). Bar in (i) represents 100 µm for all panels. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescence protein.

Figure 7.

Quantification of GFP-NeuN and GFP-GFAP colocalization. Quantification of colocalization of GFP+ delivered via each serotype with (a) NeuN and (b) GFAP. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure 6.

Transduction of glial cells by AAV pseudotypes. Confocal images (a,d,g) shows GFP+ cells (green color), which rarely colocalized with (b,e,h) GFAP (red color) in the striatum as demonstrated by (c,f,i) the merged image (only a few yellow cells). Bar in (i) represents 100 µm for all panels. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescence protein.

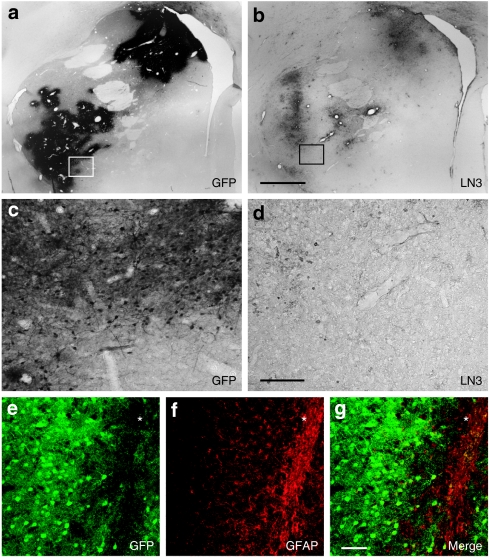

Immune response to each serotype

LN3 immunostaining was performed to evaluate the immune response for each capsid serotype (Figure 8). LN3 stains activated T cells and monocytes as well as macrophages. In all cases, some LN3+ was observed in the area near the injection tract and partially spread to a region surrounding that tract (Figure 8b). In some cases, there appeared to be some perivascular cuffing. In no case was the staining equivalent to the volume of staining seen with GFP (Figure 8a,c,d). In this regard, some areas with abundant number of GFP+ cells displayed almost no inflammatory response (Figure 8c,d). In general, any immune response appeared to be mild. Interestingly, the LN3+ microglial infiltration was distinct from the astrogliosis that was seen as a result of the needle tract. Under these conditions, a distinct band of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) positivity was observed that followed the path of the needle tract and did not extend into the region of GFP+ (Figure 8e–g).

Figure 8.

Immune response following injections of AAV serotypes in striatum. (a) Low-power photomicrographs illustrating GFP+ staining derived from AAV2/1 (caudate) and AAV2/8 (putamen). (b) A modest inflammatory response seen using LN3 staining on an adjacent section. (c,d) High-power photomicrograph of GFP and LN3 staining shows limited immune response with abundant number of GFP+ cells. e is a confocal image that demonstrates virally expressed GFP. Note the absence of GFP within the needle tract (*). (f) A dense, but limited plexus, of GFAP positivity astrocytes were observed in the needle tract (*). (g) Note the absence of GFP/GFAP colocalization in the merged image indicating that activated astroglia are not transduced by the viral vectors. Bar in (a,b) represents 2 mm, whereas (c–g) represents 100 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

AAV-GFP vector trafficking

We did not find any GFP-ir perikarya in the substantia nigra in monkeys receiving only intrastriatal AAV (data not shown) indicating that there was no retrograde transport of the AAV or the transgene, and there was no retrograde transport for any serotype from the striatum to the cerebral cortex or thalamus as well. Although we observed fibers stained for GFP in external globus pallidus, internal globus pallidus, and substantia nigra pars reticulata indicative of anterograde transport, the experimental design of this study did not permit segregation of this finding for the different serotypes.

Discussion

At present, different AAV serotypes have generated significant interest because of their excellent transgene expression and distinct tropism.28,29 Among all identified AAV serotypes, AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8 are of particular interest because of their favorable properties of transduction patterns in the basal ganglia. The present study compared the transduction efficiency of the most efficient AAV serotypes AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8 in the nonhuman primate brains. Our results confirm and extend a previously described tropism for AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8 in rodent studies. Overall, these serotypes were shown to transduce cells in the basal ganglia with high efficiency. A primary goal of this study was to compare the transduction efficiency of AAV1, AAV5, and AAV8. As the striatum is a target of interest in many gene therapy strategies for both PD and Huntington's disease, it was chosen as the primary injection region in this study. Furthermore, it is a well-delineated and well-characterized structure that is difficult to cover by single injections of vector in larger animal species and humans.23 By unbiased stereological estimates of GFP+ cells, we found that AAV2/1 and AAV2/5 transduce significantly higher number of cells compared to AAV2/8, whereas there was no significant difference between AAV2/1 and AAV2/5. With a single 10 µl injection, over 500,000 cells expressed GFP 3 months post-transduction. Interestingly, the Cavalieri's volume estimates showed the same pattern of results in the distribution of AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8. There was significant difference between AAV2/5, AAV2/1 compared to AAV2/8, whereas there was no significant difference between AAV2/1 and AAV2/5. We quantified the GFP transduced cell density in caudate and putamen; the mean value was 16,164 ± 1,830, 15,942 ± 1,486, and 11,633 ± 1,704 cells/mm3, for AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8, with no significant difference among the group (P = 0.115). Thus, an augmented number of successfully transduced cells seen with the AAV2/5 serotype appears to be due to the larger volume of spread and not a higher density of cells within an infected area. Confocal microscopic analyses revealed each vector displayed high neurotropism with very poor gliotropism. In this regard, >95% of the cells successfully transduced colocalized the specific neuronal marker NeuN, and it was only the rare GFP+ cell (<4%) that coexpressed the astrocytic marker GFAP.

The present study confirms the results from the earlier studies on rodents in tropism activity and transduction pattern of these serotypes. Earlier studies in rodents19,30 showed all serotypes displayed peak transgene expression by 4 weeks after injection and remain constant over a long period of time; our study confirms these findings and shows high efficiency of transduction with these serotypes with 3 months after injections. In rodent studies, several investigators reported efficiency of AAV2/1, AAV2/5 is equal to or better than that of AAV2/8 in the striatum, and also the high transduction rates with AAV2/1 and 2/5 in the nigra region.19,21,22,23 They all reported these vector serotypes transduce comparatively high number of neuronal cell structures in striatum or nigra without apparent toxicity. Our study confirms the gliosis or astrocytosis adjacent to the needle tract for each serotype as observed in rodent study21 with negligible inflammatory response compared to widespread transduction and high EGFP expression.

In contrast to our study, Broekman et al.18 found AAV8 has higher transduction rate compared to AAV1 that might be because their injections were done by intracerebroventricular infusion and also their study involved brain structures other than striatum and nigra, but again, they observed that predominantly neurons were transduced suggesting that brain location together with the chosen chicken β-actin promoter does not significantly affect the neurotropic or gliotropic properties of specific serotypes. Another study,31 reported neurotoxicity with high titers of AAV8-GFP (1.0 × 1010 genome copies) but not with the AAV5 or AAV1 in rodents. In that study, it remains unclear whether the toxicity is due to the vector or the transgene (i.e., GFP). In the present study, we observed no apparent toxicity with 10 µl injections using a titer of 2.57 × 1012 viral genomes/ml in monkeys. In contrast to our study, others have found that AAV5 failed to transduce the cat brain with GUSB (human lysosome enzyme β-glucuronidase) although strong GUSB gene expression with AAV1 in major gray and white matter structures.32 Whether this disparity is the result of a species differences remains to be determined.

AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 are becoming common pseudotypes used in the preclinical experiments and demonstrate similar properties to AAV2 that is still employed most often in gene therapy trials for PD. In the present study, we estimated the volume in individual caudate nuclei and putamen. We found almost 1.16 ± 0.14 mm3, 1.32 ± 0.22 mm3, and 0.64 ± 0.06 mm3 per 1 µl of AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8, respectively [without convection-enhanced delivery (CED) delivery] considering only GFP+ cells in caudate and putamen individually. Previous studies in rodents demonstrate the superiority of AAV serotypes other than AAV2 in essential vector characteristics when directly compared to AAV2. In the present study, we did not directly compare the three AAV serotypes with the AAV2/2 “the current gold standard for gene therapy in clinical studies for PD.” However, all three serotypes examined in the present study were superior to what we have seen previously with AAV2/2-GFP.33 In our previous study, we have a transduction efficiency of 0.5 mm3 for 1 µl of AAV2/2. In contrast, the current study revealed transduction efficiency of about two- to threefold with AAV2/1 and AAV2/5 pseudotypes. These findings stand in contrast to Hadaczek and co-workers34 who quantified the volume of transduced area using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Following 150 µl AAV1-GFP injections using CED, they reported 707 ± 125 mm3 volume resulting in 4.7 mm3 per 1 µl AAV1-hr GFP (2.3 × 1011 DNase-resistant particles). However, this volume also included neighboring brain structures such as the globus pallidus, subthalamic nucleus, and internal capsule where signal was observed due to the transport from the infusion sites, thus making it difficult to compare with the present study. A second study by the same group35 estimated the volume using Cavalieri's method and reported mean transduced volume of 730 mm3 in putamen for 34.5 µl AAV2-TK (1.5 × 1011 viral genomes/ml) resulting 24.3 mm3 per 1 µl AAV2-TK with a single CED infusion. Sanftner and co-workers36 estimated the volume using a design based stereology method and reported 283 mm3 transduced volume in putamen for 50 µl AAV2-h AADC resulting 2.6 mm3 per 1 µl AAV2-h AADC (15 × 1011 viral genomes/ml) by CED infusion. Future clinical trials may consider switching to a non-AAV2 serotype to deliver the therapeutic transgene and using CED delivery.

In conclusion, previous studies have shown that different AAV serotypes increase transduction efficiency and distribution of viral vector. However, very few studies have been performed using nonhuman primates. The size, complexity, and organization of the monkey brain is closer to humans and testing in this species may enhance predictive validity when considering clinical trials. With regard to PD, the neurotropism afforded by these AAV vectors allows for transduction of nigral cells directly, as we successfully demonstrated with our intranigral injections or using the neurons within the striatum to manufacture a new transgene and secrete it into the environment for uptake and utilization by degenerating nigrostriatal fibers.

Materials and Methods

Subjects. Six normal adult cynomolgus monkeys (male, 6–9 kg) were employed in this study. All monkeys were maintained one per cage on a 12-hour on/12-hour off lighting schedule with ad libitum access to food and water. The quality of animal care and experimentation exceeded the recommended National Institutes of Health guidelines. All experimentation procedures were performed according to Rush University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Biosafety Committee approved protocols.

Construction of AAV-GFP vector. The AAV recombinant genome, pTRUF11 that was packaged in AAV serotypes 1, 5, and 8, contains the coding sequence for humanized GFP37 under the control of the synthetic chicken β-actin promoter38 and the SV40 polyadenylation signal followed by the neomycin resistance gene under the control of the mutant polyomavirus enhancer/promoter (PYF441) and the human bovine growth hormone poly(A) site, flanked by AAV2 terminal repeats.39 To produce rAAV2/1, rAAV2/5, and rAAV2/8, pTRUF11 was co-transfected with pXYZ1, pXYZ5, or pDG8 helper plasmids respectively. The capsid serotype helper plasmids also contain all necessary helper function in addition to rep and cap in trans for their respective capsid serotype.40,41 Recombinant virus was then purified by iodixanol step gradients and Sepharose Q column chromatography as previously described41 and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline. All three virus stocks were at least 99% pure as judged by silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate acrylamide gel fractionation. Vector titers were determined by dot-blot assay as described,41 and the titers were determined to be as follows: rAAV2/1 = 2.75 × 1012 genome copies/ml; rAAV2/5 = 1.69 × 1013 genome copies/ml, and rAAV2/8 = 8.79 × 1012 genome copies/ml.

Surgery. Stereotaxic surgery was performed on all six monkeys according to the coordinates for stereotaxic injections based upon MRI guidance. For each serotype (AAV2/1, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8), 10 µl of concentrated viral particles (2.75 × 1012 viral genomes/ml) was administered into the striatum of all six monkeys in the pattern that resulted in each vector being injected into at least four sites (see Table 1). In addition, AAV2/1 and AAV2/8 were injected into substantia nigra at the same viral particle titer and volume as the striatal injections in some animals. The caudate injections were targeted at the head of the caudate nucleus. The putamen injections were made at the level just caudal to the decussation of the anterior commissure. Prior to surgery, monkeys were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of Telazol (10–15 mg/kg) and atropine (0.05 mg/kg, subcutaneous). Once in an anesthetic plane, monkeys were placed in the MRI-compatible stereotaxic unit. The coordinates for injection sites into the caudate nuclei, putamen, and substantia nigra were ascertained using the MRI's computer software according to previously published procedure.42

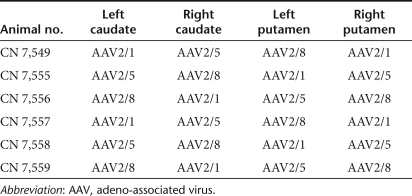

Table 1.

The injection pattern for the different AAV pseudotypes, in such a way that each serotype has been injected into at least four sites

On the day of surgery, monkeys were tranquilized with ketamine (10 mg/kg, intramuscular). The monkeys were then intubated and anesthetized with Isoflurane (1–2%) and were replaced in the same stereotaxic unit, having the same orientation used during the MRI scan. Under sterile conditions, exposure of the superior sagittal sinus served as the midline zero. The burr holes were made on the striatum and nigra regions according to the coordinates from the MRI scan. The measurements of cortical surfaces were recorded, and each monkey then received at least four injections of different serotypes of AAV-GFP. All injections were performed by using microinfusion pump (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) through the 10 µl Hamilton syringe at a rate of 1 µl per minute. The needle was left in situ for an additional 3 minutes to allow the vector to diffuse from the needle tip before slowly retracting the syringe. Following the injections, the burr holes were filled with Gelfoam. The subcutaneous tissues were closed with 4-0 coated Vicryl, and the skin was closed with 4-0 Ethilon. The monkeys were killed 3 months after injections.

Necropsy and preparation of tissue.All monkeys were deeply anesthetized and perfused transcardially with warm (100 ml) and ice-cold (400 ml) normal saline, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde solution (pH 7.4, 500 ml). The brains were removed from the calvaria and placed in 30% sucrose made in phosphate-buffered saline until brains were fully immersed. Coronal brain sections (40 µm thick) were cut with sliding knife microtome and the sections were stored at 4 °C in a cryoprotectant solution.

Histochemistry. To assess AAV transduction, a series of immunohistochemical stain for GFP was performed on every sixth section according to standard procedure.43 Briefly, sections were washed with 0.01 mol/l phosphate-buffered saline to make the tissue free from cryoprotectant prior to staining. Sections were then treated with a solution containing phosphate-buffered saline, 3% normal serum, and 2% bovine serum albumin to block the background followed by incubation in the primary anti-GFP mouse antibody (1:1,000; Clontech, Mountain View, CA) in 5% normal horse serum and 0.1% Triton X-100. Incubation was done overnight at room temperature. The sections were sequentially incubated in the biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature followed by incubation with ABC kit (VECTASTAIN Elite, cat. no. PK-6100; Vector Labs). The sections were immersed in a chromogen solution containing 0.05% 3′3 diaminobenzidine and 0.005% hydrogen peroxide. All sections were then mounted on subbed slides, dehydrated and cover-slipped. Control sections were processed in an identical manner except the primary antibody. Immunohistochemical staining for LN3 was performed on every 12th sections according to the above procedure by using the monoclonal antihuman B-lymphocyte LN-3 primary antibody (1:500; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and secondary antibody biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Vector Labs).

Double-labeling immunofluorescence procedure. Transduced cells from the injections were further characterized by double labeling GFP with either neuron-specific nuclear protein (NeuN) or GFAP (GFP as a native fluorescence and NeuN or GFAP). Immunofluorescence staining was performed on every 12th section by using the rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:1,000; Chemicon, Billerica, MA) and mouse anti-NeuN (1:500; Chemicon). Standard staining procedures were performed with an additional fluorophore treatment by using streptavidin-conjugated Cy 5 (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). After 1-hour incubation with fluorophore, sections were washed, mounted, dehydrated and then cover-slipped with mounting media. Control sections were processed in an identical manner except primary antibody treatment.

Stereology counting. To compare the transduction efficiency in the striatum, the total number of GFP+ cells within the striatum was determined using optical fractionator procedure.44,45 Briefly, the Stereo Investigator 2000 System (MicroBrightField Bioscience, Colchester, VT) was used to perform unbiased stereological estimates. This method determines the precise estimates of the total number of cells present in the selected region by counting cells in a fraction of the region, represented by “optical dissectors.” Prior to each series of measurements, the instrument was calibrated. Using low-magnification ×1.25 objective, the counting region (caudate, putamen, or nigra) was outlined. Random sample of the area was assured by using Stereo Investigator 2000 software. Optical dissectors were defined using a counting frame with width and height set at 70 µm and thickness set at 20 µm, and two guard zones of 2 µm were applied. Cell counts were made at regular intervals (X = 500 µm, Y = 500 µm). The sections were analyzed using high-magnification (×60) oil immersion objective with 1.4 numerical aperture. Using the uniform, systematic, and random design counting procedure,44,46 and stereological principles, the GFP+ cells through the specific regions were sampled.

Volume measurement. The volume of the transduced brain area was quantified according to Cavalieri principle using the above-mentioned Stereo Investigator 2000 software as described previously.45,47 Four regions (left caudate, right caudate, left putamen, and right putamen) in each animal were sampled using serial sections with an interval of 240 µm centered around the injection site. A counting grid was placed over the screen on which the entire transduced brain region was displayed from a low-power (×4) objective. Grid points overlying the GFP+ perikarya located in the caudate and putamen were counted separately. The transduced volume was calculated by multiplying the sum of the counted points by the distance between the counted sections and the area associated with each point on the grid. The statistical procedure was performed to analyze the data obtained for each region.

Fluorescence imaging and quantification. An Olympus IX81 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Imaging America, Center Valley, PA) was used for fluorescence imaging. Green and red channels (Cy 2 and Cy 5, respectively) were sequentially activated to observe the double-labeled (GFP-NeuN and GFP-GFAP) cells. A minimum of 200 GFP+ cells were counted per brain site per animal, and the ratio for GFP+/NeuN+ or GFP+/GFAP+ cells relative to the total GFP+ population was determined. The data for each vector was then combined and plotted on the graph to compare the neurotropism and gliotropism efficiency of each serotype.

Statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and SigmaStat software (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA) for GFP stereological counting data, volume measurement data, and percentage colocalization double-label counting data. The F-test score and P value were recorded for all comparisons. When appropriate, post hoc analysis between groups was performed by using the Bonferroni and Dunn's method to control for multiple comparisons.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yaping Chu for microscopic guidance and Gina Folino for histochemistry assistance. This work has been funded by NIH (grant no. NS055143).

REFERENCES

- Muzyczka N. Use of adeno-associated virus as a general transduction vector for mammalian cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;158:97–129. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-75608-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildinger M., and , Auricchio A. Advances in AAV-mediated gene transfer for the treatment of inherited disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:263–271. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JS, Samulski RJ., and , McCown TJ. Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:1181–1186. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.8-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R, Janson CG, Mastakov M, Lawlor P, Young D, Mouravlev A, et al. Quantitative comparison of expression with adeno-associated virus (AAV-2) brain-specific gene cassettes. Gene Ther. 2001;8:1323–1332. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN Jr, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–2248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee SW, Janson CG, Li C, Samulski RJ, Camp AS, Francis J, et al. Immune responses to AAV in a phase I study for Canavan disease. J Gene Med. 2006;8:577–588. doi: 10.1002/jgm.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worgall S, Sondhi D, Hackett NR, Kosofsky B, Kekatpure MV, Neyzi N, et al. Treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis by CNS administration of a serotype 2 adeno-associated virus expressing CLN2 cDNA. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:463–474. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberling JL, Jagust WJ, Christine CW, Starr P, Larson P, Bankiewicz KS, et al. Results from a phase I safety trial of hAADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1980–1983. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312381.29287.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, Fitzsimons HL, Mattis P, Lawlor PA, et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson's disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH., and , Olanow CW. Regulatable promoters and gene therapy for Parkinson's disease: is the only thing to fear, fear itself. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks WJ Jr, Ostrem JL, Verhagen L, Starr PA, Larson PS, Bakay RA, et al. Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease: an open-label, phase I trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:400–408. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Burger C, Lundberg C, Johansen TE, Muzyczka N, et al. Parkinson-like neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of alpha-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2780–2791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Annett LE, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ., and , Björklund A. Nigrostriatal alpha-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human alpha-synuclein: a new primate model of Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2884–2889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536383100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D., and , Björklund A. Modeling CNS neurodegeneration by overexpression of disease-causing proteins using viral vectors. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:386–392. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, King MA, Hamby ME., and , Meyer EM. Dopaminergic cell loss induced by human A30P alpha-synuclein gene transfer to the rat substantia nigra. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:605–612. doi: 10.1089/10430340252837206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy A, Bjorklund T, Hermening S., and , Kirik D. In vivo gene delivery for development of mammalian models for Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Iwatsubo T, Mizuno Y., and , Mochizuki H. Overexpression of alpha-synuclein in rat substantia nigra results in loss of dopaminergic neurons, phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein and activation of caspase-9: resemblance to pathogenetic changes in Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2004;91:451–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekman ML, Comer LA, Hyman BT., and , Sena-Esteves M. Adeno-associated virus vectors serotyped with AAV8 capsid are more efficient than AAV-1 or -2 serotypes for widespread gene delivery to the neonatal mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;138:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Gorbatyuk OS, Velardo MJ, Peden CS, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, et al. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2004;10:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson BL, Stein CS, Heth JA, Martins I, Kotin RM, Derksen TA, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3428–3432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050581197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland NR, Lee JS, Hyman BT., and , McLean PJ. Comparison of transduction efficiency of recombinant AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, and 8 in the rat nigrostriatal system. J Neurochem. 2009;109:838–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterna JC, Feldon J., and , Büeler H. Transduction profiles of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors derived from serotypes 2 and 5 in the nigrostriatal system of rats. J Virol. 2004;78:6808–6817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6808-6817.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taymans JM, Vandenberghe LH, Haute CV, Thiry I, Deroose CM, Mortelmans L, et al. Comparative analysis of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 in mouse brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:195–206. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cearley CN, Vandenberghe LH, Parente MK, Carnish ER, Wilson JM., and , Wolfe JH. Expanded repertoire of AAV vector serotypes mediate unique patterns of transduction in mouse brain. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1710–1718. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirmule N, Propert K, Magosin S, Qian Y, Qian R., and , Wilson J. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1574–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erles K, Sebökovà P., and , Schlehofer JR. Update on the prevalence of serum antibodies (IgG and IgM) to adeno-associated virus (AAV) J Med Virol. 1999;59:406–411. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199911)59:3<406::aid-jmv22>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peden CS, Burger C, Muzyczka N., and , Mandel RJ. Circulating anti- wild-type adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) antibodies inhibit recombinant AAV2 (rAAV2)-mediated, but not rAAV5-mediated, gene transfer in the brain. J Virol. 2004;78:6344–6359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6344-6359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Nash K., and , Mandel RJ. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors in the nervous system. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:781–791. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH., and , Wilson JM. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:285–297. doi: 10.2174/1566523054065057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimsnider S, Manfredsson FP, Muzyczka N., and , Mandel RJ. Time course of transgene expression after intrastriatal pseudotyped rAAV2/1, rAAV2/2, rAAV2/5, and rAAV2/8 transduction in the rat. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1504–1511. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RL, Dayton RD, Leidenheimer NJ, Jansen K, Golde TE., and , Zweig RM. Efficient neuronal gene transfer with AAV8 leads to neurotoxic levels of tau or green fluorescent proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vite CH, Passini MA, Haskins ME., and , Wolfe JH. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated transduction in the cat brain. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1874–1881. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Herzog CD, Dass B, Bakay RA, Stansell J, Gasmi M, et al. Delivery of neurturin by AAV2 (CERE-120)-mediated gene transfer provides structural and functional neuroprotection and neurorestoration in MPTP-treated monkeys. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:706–715. doi: 10.1002/ana.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaczek P, Forsayeth J, Mirek H, Munson K, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, et al. Transduction of nonhuman primate brain with adeno-associated virus serotype 1: vector trafficking and immune response. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:225–237. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadaczek P, Kohutnicka M, Krauze MT, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, Cunningham J, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) into the striatum and transport of AAV2 within monkey brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:291–302. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanftner LM, Sommer JM, Suzuki BM, Smith PH, Vijay S, Vargas JA, et al. AAV2-mediated gene delivery to monkey putamen: evaluation of an infusion device and delivery parameters. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Hauswirth WW, Guy J., and , Muzyczka N. A “humanized” green fluorescent protein cDNA adapted for high-level expression in mammalian cells. J Virol. 1996;70:4646–4654. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4646-4654.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H, Yamamura K., and , Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C, Nguyen FN, Deng J., and , Mandel RJ. Systemic mannitol-induced hyperosmolality amplifies rAAV2-mediated striatal transduction to a greater extent than local co-infusion. Mol Ther. 2005;11:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Flotte TR, Reier PJ., and , Mandel RJ. Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated global anterograde delivery of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor to the spinal cord: comparison of rubrospinal and corticospinal tracts in the rat. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:71–82. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotukhin S, Potter M, Zolotukhin I, Sakai Y, Loiler S, Fraites TJ, Jr, et al. Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28:158–167. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordower JH, Bloch J, Ma SY, Chu Y, Palfi S, Roitberg BZ, et al. Lentiviral gene transfer to the nonhuman primate brain. Exp Neurol. 1999;160:1–16. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride JL, During MJ, Wuu J, Chen EY, Leurgans SE., and , Kordower JH. Structural and functional neuroprotection in a rat model of Huntington's disease by viral gene transfer of GDNF. Exp Neurol. 2003;181:213–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emborg ME, Ma SY, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Taylor MD, Brown WD, et al. Age-related declines in nigral neuronal function correlate with motor impairments in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C., and , Hof PR. Design-based stereology in neuroscience. Neuroscience. 2005;130:813–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamura C, Dell'Acqua ML, Moessner R, Murphy DL, Lesch KP., and , Persico AM. Altered neocortical cell density and layer thickness in serotonin transporter knockout mice: a quantitation study. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1394–1401. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baekelandt V, Claeys A, Eggermont K, Lauwers E, De Strooper B, Nuttin B, et al. Characterization of lentiviral vector-mediated gene transfer in adult mouse brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:841–853. doi: 10.1089/10430340252899019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]