Abstract

The sensitivity and frequency selectivity of hearing result from tuned amplification by an active process in the mechanoreceptive hair cells. In most vertebrates, the active process stems from the active motility of hair bundles. The mammalian cochlea exhibits an additional form of mechanical activity termed electromotility: its outer hair cells (OHCs) change length upon electrical stimulation. The relative contributions of these two mechanisms to the active process in the mammalian inner ear is the subject of intense current debate. Here, we show that active hair-bundle motility and electromotility can together implement an efficient mechanism for amplification that functions like a ratchet: Sound-evoked forces, acting on the basilar membrane, are transmitted to the hair bundles, whereas electromotility decouples active hair-bundle forces from the basilar membrane. This unidirectional coupling can extend the hearing range well below the resonant frequency of the basilar membrane. It thereby provides a concept for low-frequency hearing that accounts for a variety of unexplained experimental observations from the cochlear apex, including the shape and phase behavior of apical tuning curves, their lack of significant nonlinearities, and the shape changes of threshold tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers along the cochlea. The ratchet mechanism constitutes a general design principle for implementing mechanical amplification in engineering applications.

Keywords: auditory system, cochlea, hair cell

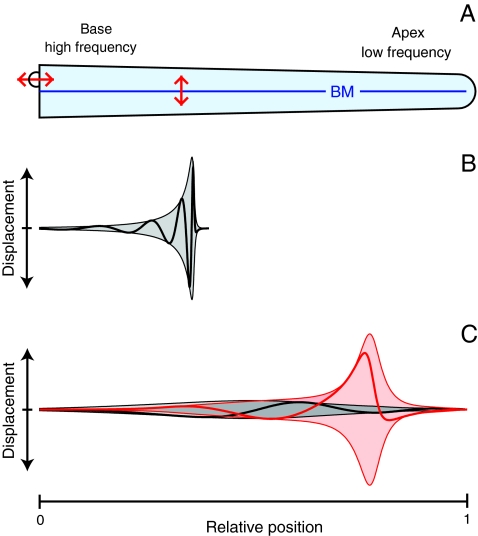

The mammalian cochlea acts as a frequency analyzer in which high frequencies are detected at the organ’s base and low frequencies at more apical positions. This frequency mapping is thought to be achieved by a position-dependent resonance of the elastic basilar membrane separating two fluid-filled compartments (Fig. 1A) (1–3). When sound evokes a pressure wave that displaces the basilar membrane, the resultant traveling wave gradually increases in amplitude as it progresses to the position where the basilar membrane’s resonant frequency coincides with that of the stimulus. Aided by mechanical energy provided by the active process, the wave peaks at a characteristic place slightly before the resonant position and then declines sharply (Fig. 1B). This mechanism is termed critical-layer absorption (1), for a wave cannot travel beyond its characteristic position on the basilar membrane but peaks and dissipates most of its energy there. The mechanism displays scale invariance: different stimulation frequencies induce traveling waves that display a common, strongly asymmetric form upon rescaling of the amplitude and spatial coordinate (4, 5).

Fig. 1.

Principles of cochlear mechanics. (A) In a schematic diagram of the mammalian cochlea, the basilar membrane (BM) is displaced by sound stimuli acting on the stapes (Upper Left). (B) In the classical theory of cochlear mechanics, sound evokes a pressure wave that causes a longitudinal traveling wave of basilar-membrane displacement (Thick Line). The motion of the basilar membrane and the displacements of the associated hair bundles are approximately equal. As the wave approaches the position where its frequency matches the basilar membrane’s resonant frequency, the wave’s amplitude (Thin Line) increases and its wavelength and velocity decline. The wave peaks at a characteristic place slightly before the resonant position and then declines sharply, yielding a strongly asymmetric envelope of the traveling wave (Shading). Experiments confirm this behavior in the basal, high-frequency part of the cochlea. (C) We propose an alternative theory for the cochlea’s mechanics at low frequencies. The basilar membrane near the cochlear apex does not resonate, but the traveling wave on the basilar membrane propagates along the entire cochlea without a strong variation in amplitude, wavelength, and velocity (Black). However, the interplay of electromotility and active hair-bundle motility fosters an independent resonance of the complex formed by the hair bundles, reticular lamina, and tectorial membrane. The hair-bundle displacement (Red) at the characteristic place can therefore exhibit an approximately symmetric peak, exceeding basilar membrane motion by orders of magnitude.

Two important aspects of the cochlea’s mechanics remain problematical. First, the basilar membrane’s resonant frequency apparently cannot span the entire range of audible frequencies. Experimental measurements of basilar-membrane stiffness suggest that high-frequency resonances are feasible but low-frequency ones are inaccessible (6). This result accords with the analysis of threshold tuning curves for auditory-nerve fibers (7–9) and measurements of basilar-membrane displacement (8, 10–12), both of which indicate that a peaked traveling wave occurs for high-frequency stimulation but not for low-frequency stimulation. Indeed, threshold tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers (7–9) show that high-frequency curves are scale-invariant and possess a sharp cutoff at frequencies above their characteristic frequencies, reflecting the mechanism of critical-layer absorption. However, low-frequency curves lack this sharp cutoff and, in contradiction of the expectation for critical-layer absorption, are instead characterized by an approximately symmetric shape around their characteristic frequencies. Recent experiments in the chinchilla have shown that the shape change between the tuning curves of high- and low-frequency fibers occurs between two crossover frequencies of about 5 kHz and 1.5 kHz (8, 9). Measurements of basilar-membrane displacement yield similar conclusions. Experiments from the cochlear base confirm the existence at high frequencies of peaked traveling waves that result in strongly asymmetric tuning curves and a pronounced nonlinearity at the characteristic frequencies (8, 12–14). Apical measurements of basilar-membrane displacement, however, produce symmetric tuning curves that lack a sharp cutoff for frequencies higher than the characteristic frequency (10, 11, 15). Moreover, only small nonlinearity has been measured (10, 15, 16), raising the question whether amplification occurs at the apex. All available experimental results therefore indicate that low-frequency hearing does not function through critical-layer absorption but must rely on another mechanism to achieve frequency selectivity.

The second key uncertainty is the nature of the active process that operates in the mammalian cochlea. In addition to amplifying weak signals, the active process produces increased frequency selectivity, compressive nonlinearity, and spontaneous otoacoustic emission. In the mammalian cochlea, amplification is provided by specialized OHCs located in the organ of Corti along the basilar membrane (Fig. 2A). Each OHC displays two forms of motility. Like those in the hearing organs of other vertebrates (17, 18), the hair bundle of an OHC can produce mechanical force (17–22). But an OHC also exhibits electromotility: when its membrane potential changes as a result of sound-evoked hair-bundle deflection, the entire cell undergoes a length change owing to conformational rearrangement of the membrane protein prestin (23–25). Direct measurements of the respective roles of the two forms of motility are complicated, for it is difficult to determine the micromechanical responses of the organ of Corti while the cochlea remains intact.

Fig. 2.

The ratchet mechanism. (A) The organ of Corti rests upon the basilar membrane (BM). Three OHCs are connected to Deiters’ cells (DC) that together couple the basilar membrane to the reticular lamina (Dark Green, top of the OHCs) and through the hair bundles to the overlying tectorial membrane (TM). Sound-evoked external forces (Black Arrow) displace the basilar membrane, here upwards, and produce shearing (Black Arrow) of the hair bundles of OHCs (Red Asterisk) and the inner hair cell (IHC) (Cyan Asterisk). Two forms of motility underlie the active process: active hair-bundle motility (Single-Headed Red Arrow) and membrane-based electromotility (Double-Headed Red Arrow). (B) The two fundamental degrees of freedom are the basilar-membrane displacement XBM and the displacement XHB of the hair-bundle complex (circle) that comprises the hair bundles, reticular lamina (RL), and tectorial-membrane. Coupling stems from the impedance ZD of the combined OHCs and Deiters’ cells as well as the impedance ZC of the remaining organ of Corti. (C) In the ratchet mechanism, displacements of the basilar membrane caused by external forces are communicated to the hair-bundle complex. Internal forces (Red Arrow) in the hair bundles increase the shearing motion that decouples from basilar-membrane displacement through appropriate length changes of the OHCs (Dotted Red Arrow). For an animated representation of the model, see Movie S1.

Here we have taken a theoretical approach to investigate a possible mechanism for amplification by the synergistic interplay of active hair-bundle motility and electromotility. We show that they can operate together to achieve low-frequency selectivity in the absence of basilar-membrane resonance and critical-layer absorption. The model advances theoretical understanding of cochlear mechanics in three ways: it reproduces previous theoretical results insofar as they coincide with experiments; it accounts naturally for a variety of unexplained findings from the cochlear apex; and it makes robust, experimentally testable predictions.

Results

The Ratchet Mechanism.

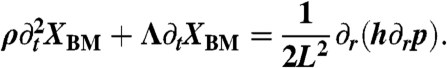

Consider a transverse element of the cochlear partition comprising the basilar membrane, an inner hair cell (IHC) and three OHCs, and the overlying tectorial membrane (Fig. 2A). When a sound-evoked force displaces the basilar membrane upward, the resultant shearing motion between the tectorial membrane and the top of the OHCs, or reticular lamina, deflects the hair bundles in the positive direction. Active hair-bundle motility in the OHCs increases the amplitude of deflection. Without electromotility, this additional displacement would couple back to the basilar membrane and augment the movement there. If electromotility is adjusted such that the OHCs elongate just as much as the tectorial membrane and reticular lamina move upward, however, the basilar membrane does not experience the active force and thus undergoes no additional displacement (Movie S1).

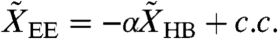

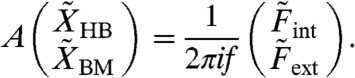

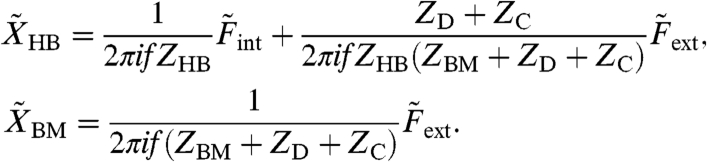

A mathematical formulation of this amplification mechanism clarifies its operation. Consider a two-mass model in which the two degrees of freedom are the motion of the basilar membrane, XBM, and that of the complex formed by the hair bundles, reticular lamina, and tectorial membrane, XHB (Fig. 2B). A sound stimulus of frequency f produces an oscillating external force  acting on the basilar membrane, in which c.c. denotes the complex conjugate. The evoked oscillations of the basilar membrane as well as the hair-bundle complex occur predominantly at the same frequency,

acting on the basilar membrane, in which c.c. denotes the complex conjugate. The evoked oscillations of the basilar membrane as well as the hair-bundle complex occur predominantly at the same frequency,  and

and  . Internal forces Fint arise within hair bundles, where they provide negative damping and introduce nonlinearities (SI Text). The cell bodies of OHCs can be described as piezoelectric elements (26). For small, physiologically relevant motions their electrically evoked displacement

. Internal forces Fint arise within hair bundles, where they provide negative damping and introduce nonlinearities (SI Text). The cell bodies of OHCs can be described as piezoelectric elements (26). For small, physiologically relevant motions their electrically evoked displacement  is proportional to the hair-bundle displacement that triggers changes in the membrane potential, so

is proportional to the hair-bundle displacement that triggers changes in the membrane potential, so  with a complex mechanomotility coefficient α (27). The hair-bundle and basilar-membrane displacements then depend linearly on the forces:

with a complex mechanomotility coefficient α (27). The hair-bundle and basilar-membrane displacements then depend linearly on the forces:

|

[1] |

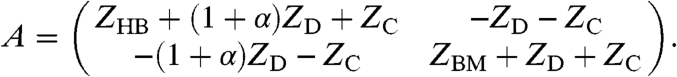

The matrix A contains the impedances ZHB and ZBM of the hair-bundle complex and the basilar membrane as well as the coupling impedances ZD and ZC (Fig. 2B):

|

[2] |

A key feature of this relation is that the matrix element A21 that describes the coupling of the internal force to the basilar membrane vanishes at a critical value α∗ ≡ -1 - ZC/ZD. At the same time, the coupling of the external force to the hair bundle that is represented by element A12 remains nonzero. For the critical value α∗ the displacements become

|

[3] |

The hair-bundle displacement depends on both the internal and external forces, whereas the basilar membrane experiences only the external force. In other words, the sound-evoked external force on the basilar membrane is transmitted to the hair bundle, but the internal force from active hair-bundle motility does not feed back onto the motion of the basilar membrane (Fig. 2C). This symmetry-breaking mode has the characteristics of a ratchet in the sense that information flows unidirectionally: Information applied as a force against the basilar membrane can be detected in the form of hair-bundle displacement, but force acting on the hair bundle cannot be detected at the basilar membrane. The basilar-membrane displacement equals that occuring when the hair-bundle complex is fixed at  and electromotility is absent (α = 0). The ratchet mechanism, therefore, resembles an ideal operational amplifier that neither feeds back on nor draws energy from the input (28).

and electromotility is absent (α = 0). The ratchet mechanism, therefore, resembles an ideal operational amplifier that neither feeds back on nor draws energy from the input (28).

The Mechanomotility Coefficient α.

The magnitude and phase of the critical value α∗ depend on the coupling impedances ZC and ZD. Under realistic assumptions |ZC| is similar to or smaller than |ZD| and |α∗| is therefore near unity. Such a value for the mechanomotility coefficient α has been measured experimentally for apical OHCs (27). The phase of α is controlled by the complex network of ion channels that regulates the membrane potential depending on the hair-bundle displacement (27, 29). Although experiments on the phase of α are not available, theoretical considerations confirm that OHCs have sufficient flexibility through ion-channel regulation to adjust the phase of α to a variety of values and, in particular, to the phase required for α∗ (SI Text).

A Concept for Low-Frequency Hearing.

As its most important characteristic, the ratchet mechanism can explain frequency selectivity near the cochlear apex in the absence of a peaked traveling wave. The resonant frequency of the hair-bundle complex is determined solely by the impedance ZHB and the internal forces, and is therefore defined by the properties of the hair bundles and tectorial membrane (3) (30,31–32). In particular, hair-bundle resonance can occur in the absence of basilar-membrane resonance. The ratchet mechanism therefore permits the resonant frequency of the hair bundles to follow a logarithmic law along the cochlea, whereas the resonant frequency of the basilar membrane remains significantly greater near the apex (Fig. 3B) (6).

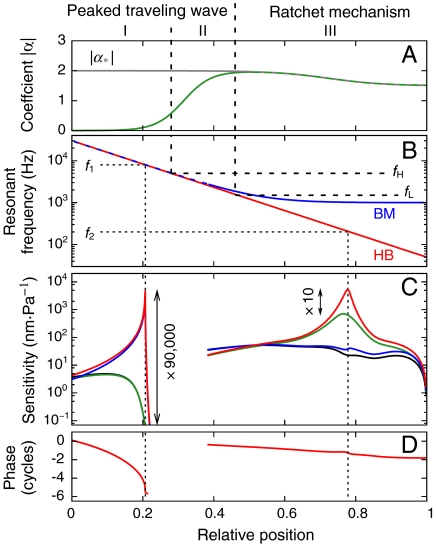

Fig. 3.

Cochlear model. (A) The ratchet mechanism operates when the mechanomotility coefficient α (Green) coincides with the critical value α∗ (gray). Although electromotility is negligible to the basal side of fH, it underlies the ratchet mechanism apical to the position of fL. (B) The resonant frequency of the hair-bundle complex (HB, Red) agrees with that of the basilar membrane (BM, Blue) only for frequencies above fL. (C) A high-frequency sound stimulus (f1 = 8 kHz) induces a traveling wave that peaks in the basal region. The displacements of the hair bundles (Red) coincide with that of the basilar membrane (Blue). Elimination of active hair-bundle motility decreases the sensitivity by a factor of 90,000 (Green, hair bundles; Black, basilar membrane) indicative of a strong nonlinearity. A low-frequency stimulus (f2 = 200 Hz) triggers a traveling wave that does not peak on the basilar membrane, but the hair-bundle displacement exhibits a resonance enabled by the ratchet mechanism (same color code). Without active hair-bundle motion the hair-bundle displacement decreases by a factor of only 10, indicative of a weak nonlinearity. (D) The phase of the basilar-membrane displacement for f1 has a strongly increasing slope near the resonant position and thus shows a wave traveling to the resonant position but not beyond. For f2 the slope of the phase remains almost constant, corresponding to a wave traveling beyond the characteristic place.

Further evidence points to the occurrence of the ratchet mechanism at the cochlear apex but not at the base. First, the basilar membrane at the base is narrow and presumably tuned to the characteristic frequencies at which auditory-nerve fibers are most sensitive (Fig. 3B). Amplification of basilar-membrane motion there is feasible and need not be avoided. Indeed, experiments have demonstrated a strong compressive nonlinearity of basilar-membrane motion at high frequencies. However, the apex exhibits a wider basilar membrane that experiences stronger viscous forces and whose resonant frequencies deviate from the characteristic frequencies (6). Amplification of basilar-membrane motion near the apex would therefore be highly inefficient. The absence of a strong, compressive nonlinearity in experimental measurements of basilar-membrane displacement in the apical region confirms the lack of basilar-membrane amplification there. Next, the membrane time constant of OHCs restricts electromotility’s ability to work on a cycle-by-cycle basis to frequencies below a few kilohertz (33, 34), disabling the ratchet mechanism for higher frequencies. It is noteworthy that the ion channels of apical OHCs differ significantly from those of basal OHCs (35) and that apical OHCs are considerably longer than basal ones and can accordingly produce greater length changes (25).

A Unified Model for Cochlear Mechanics.

We have quantified these considerations in a one-dimensional model of the cochlea (SI Text). Studies of threshold tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers in the chinchilla have delineated three distinct regimes that are separated by two crossover frequencies, a high frequency fH ≈ 5 kHz, and a low frequency fL ≈ 1.5 kHz (Fig. 3) (9). In our model for the basal regime I, above fH, electromotility is negligible owing to the membrane time constant; each segment of the basilar-membrane is tuned to its characteristic frequency. In the transitional regime II, between fH and fL, unidirectional coupling provided by electromotility occurs, but every segment of the basilar-membrane still resonates at its characteristic frequency. In the apical regime III, below fL, electromotility combines with active hair-bundle motility to implement the ratchet mechanism for amplification. The resonant frequency of the basilar-membrane is therefore of minor importance and remains approximately constant at a value significantly above the range of characteristic frequencies.

In accordance with the theory of critical-layer absorption (1), in regime I the traveling-wave produced by a pure-tone stimulus peaks at the characteristic place and sharply decreases beyond that point (Fig. 3C). The characteristic behavior of critical-layer absorption—decrease of the traveling-wave’s speed and wavelength near the characteristic place—appears in the phase behavior as an increase of the slope (Fig. 3D). Active hair-bundle motility amplifies the peak displacement. A strong compressive nonlinearity arises because amplification by active hair-bundle motility both increases the hair-bundle and basilar-membrane motion per unit pressure difference and enhances the amplitude of the pressure wave itself (Fig. 3C). The combination of the two effects yields a compressive nonlinearity that extends over a significantly broader range of sound intensities than the nonlinearity in hair-bundle motion itself.

In regime II, electromotility influences the micromechanics and causes hair-bundle displacement to exceed basilar-membrane displacement. The theory of critical-layer absorption still applies. The basilar-membrane tuning curves, phase behavior, and nonlinearity consequently parallel those in regime I.

In regime III, the ratchet mechanism leads to very different behavior. Sound evokes a low-frequency pressure wave that traverses the entire cochlea, evoking only a small basilar-membrane displacement throughout, for the resonant frequency of the basilar-membrane is higher everywhere (Fig. 3B). At the characteristic place, however, the hair bundles exhibit an independent resonance amplified through active hair-bundle motility and facilitated by the unidirectional coupling provided by electromotility. The hair-bundle displacement there can exceed the basilar-membrane response by orders of magnitude (Fig. 3C). In further contrast to the theory of critical-layer absorption, the traveling wave does not slow and its wavelength does not vanish at the characteristic place, for the basilar-membrane does not resonate. This becomes apparent in the behavior of the traveling wave’s phase, whose slope remains low and nearly constant across the characteristic place (Fig. 3D). The phase behavior also confirms that the wave reaches the helicotrema. Because amplification through the ratchet mechanism does not act on the basilar membrane, the latter exhibits approximately linear behavior (Fig. 3C). The pressure wave is therefore unaffected by the active process. Hair-bundle displacement is amplified and exhibits a moderate compressive nonlinearity (Fig. 3C).

Threshold Tuning Curves of Auditory-Nerve Fibers.

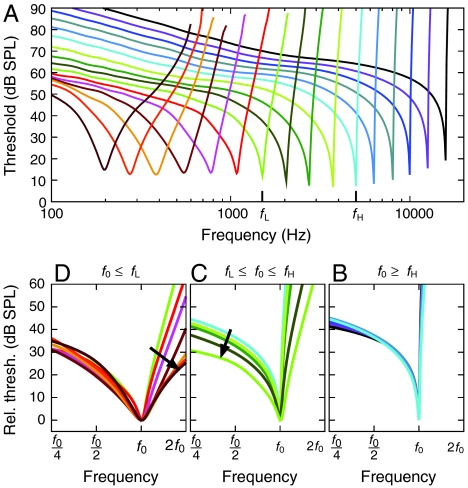

Strong support for the proposed model comes from studies of threshold tuning curves for auditory-nerve fibers (7–9). Recent measurements have shown characteristic shape changes occurring around the crossover frequencies fH and fL (9). To compare these data to our model, we have computed tuning curves and—despite their complexity and the simplicity of our model—found striking agreement with the measurements (Fig. 4). High-frequency fibers, those tuned above fH, display the strongly asymmetric shape characteristic of critical-layer absorption. Moreover, they fall onto a universal curve when the frequency and threshold are measured relative to the values at the characteristic frequency. This accords with experimental findings and the scaling symmetry of the peaked traveling-wave mechanism (4, 5, 9). For intermediate characteristic frequencies between fL and fH the scaling law is violated as the ratchet mechanism starts to influence the micromechanics, causing the left limb of the threshold tuning curves to fall as the characteristic frequency decreases (9). A second violation of the scaling arises for characteristic frequencies below fL, for which the right limb falls. Also observed experimentally (9), this second violation of scaling indicates a breakdown of critical-layer absorption that predicts a steep increase for threshold tuning curves at frequencies above the characteristic frequency.

Fig. 4.

Threshold tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers. (A) The tuning curve at each position along the cochlea has a characteristic frequency f0 corresponding to the resonant frequency of the hair-bundle complex. When tuning curves are rescaled such that the frequency is measured in octaves relative to the characteristic frequency f0 and the threshold is measured relative to that at the characteristic frequency, characteristic shape changes are seen to occur between curves of different characteristic frequencies. (B) Tuning curves for high characteristic frequencies, above fH, fall onto a universal curve that exhibits the strongly asymmetric form and high-frequency cutoff characteristic of a peaked traveling wave. (C) As the characteristic frequency declines from fH to fL, the left limb falls (Arrow), indicating the emerging influence of electromotility and the ratchet mechanism. (D) As the characteristic frequency diminishes below fL, the right limb falls steeply (Arrow), pointing to the breakdown of the peaked-wave mechanism and the dominance of ratchet amplification.

Discussion

The classical theory of cochlear mechanics assumes that the basilar membrane resonates at a characteristic place for each frequency in the auditory range. The resulting mechanism of critical-layer absorption is characterized by (i) strongly asymmetric, scale-invariant tuning curves with steep, high-frequency cutoffs, (ii) an increasing slope of the traveling wave’s phase upon approaching the characteristic place, (iii) basilar-membrane displacement similar to hair-bundle displacement, and (iv) pronounced compressive nonlinearity at the characteristic frequency. This picture is consistent with diverse experimental findings from the cochlear base, including direct measurements of basilar-membrane motion and studies of threshold tuning curves for auditory-nerve fibers. However, as summarized previously, experimental results from the cochlea’s apex are in qualitative disagreement with the first, second, and fourth characteristics.

Here we have proposed a concept for low-frequency hearing that employs a ratchet mechanism involving the interplay of active hair-bundle motility and electromotility. Whereas sound-evoked forces displace the basilar membrane and the hair bundles, the active forces within the hair bundle can decouple from the basilar membrane through appropriate elongation and contraction of OHCs. This mechanism allows hair bundles to resonate independently of the basilar membrane and thus explains how the ear’s hearing range can extend to values well below the resonant frequency of the basilar membrane. We have shown that amplification by the ratchet mechanism leads to characteristic behavior that is distinct from that associated with critical-layer absorption: it exhibits (i′) approximately symmetric tuning curves that display no sharp, high-frequency cutoff, (ii′) a constant slope of the traveling wave’s phase across the characteristic place, (iii′) tuned hair-bundle displacement that exceeds the untuned basilar-membrane displacement by orders of magnitude at resonance, and (iv′) approximately linear basilar-membrane displacement and only moderate compressive nonlinearity in hair-bundle motion at the characteristic frequency.

Comparison to Experimental Results.

The proposed model yields the classical theory of critical-layer absorption for high-frequency sounds (Figs. 1B, 3, and 4A). Experiments in the base have confirmed (i) the asymmetric form of tuning curves (13, 14), (ii) the increasing slope of the phase (36, 37), and (iv) the strong compressive nonlinearity (13, 14, 37). Owing to difficulties in accessing the motion of the organ of Corti at the base, the relation (iii) of hair-bundle motion to basilar-membrane motion has not yet been measured there.

Because the membrane time constant of OHCs is expected to limit the operation of electromotility to low frequencies (33, 34), we have chosen in our model to consider only active hair-bundle motility in the basal part of the cochlea. However, studies in prestin knockout mice suggest that electromotility is necessary for high-frequency amplification (38, 39). Electromotility near the base may adjust the operating point of the hair-bundle motor on a time scale slower than the period of oscillation or provide a fast electrical signal in the form of membrane-potential change upon mechanical stimulation.

Our theory accounts for a number of unexplained results from the cochlear apex. Experiments have measured (i′) approximately symmetric tuning curves without sharp, high-frequency cutoffs of tectorial-membrane and therefore hair-bundle displacement (10, 11, 15). In our model, the approximate symmetry arises naturally, for it reflects the resonance of the hair bundles, reticular lamina, and tectorial membrane independently of resonance by the basilar membrane (Figs. 1C and 3C and D). Experiments have consistently reported (ii′) a constant phase slope across the characteristic place (10, 11, 40). This feature emerges in our model (Fig. 3D) because the basilar membrane is untuned at low frequencies and the pressure wave therefore reaches the helicotrema. There remains a controversy about the existence of nonlinearity at the cochlear apex (12): Although some investigators have found no nonlinearites (15), others have reported a small compressive (10, 16) or expansive nonlinearity (11). However, all agree about (iv′) the absence of a strong compressive nonlinearity.

The cochlear apex allows observation of different parts of the organ of Corti—such as the tectorial membrane and Hensen’s cells as well as the basilar membrane—and thus permits tests of characteristic (iii′) in our model. Experiments on a temporal-bone preparation (15, 41) have shown that vibrations of the reticular lamina and tectorial membrane are orders of magnitude larger than the basilar-membrane displacement at the characteristic place. These findings are in perfect agreement with our theory. However, the in vitro experiments have been criticized for an uncertainty about which constituents of the organ of Corti were measured (12) and are in contradiction with studies using other preparations (10, 16). Definite conclusions must, therefore, be postponed until further experimental results become available.

Perhaps the most reliable comparison of our model to experimental measurements comes through tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers that yield information about cochlear mechanics that is least disturbed by experimental intervention and represent responses from the whole length of the cochlea. These tuning curves exhibit progressive shape changes from (i) the strongly asymmetric form typical of high-frequency fibers to (i′) the nearly symmetric form found for low-frequency fibers (7–9). Our modeled responses of tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers exhibit the same shape changes (Fig. 4), thus providing a conceptual explanation for the three distinct cochlear regimes.

Experimentally Testable Predictions.

Our theory yields experimentally testable predictions based on the characteristics (i′)–(iv′). As discussed above, (i′) the approximately symmetric tuning curves as well as (ii′) the constant phase slope have already been observed. In contrast, characteristic (iii′) that predicts hair-bundle motion that exceeds the basilar-membrane motion at the characteristic frequency by orders of magnitude remains controversial. Future experiments are therefore required to test this prediction. Such studies should also determine whether, as our theory implies, the complex formed by the hair bundles, reticular lamina, and tectorial membrane exhibits a resonance independent of the basilar membrane, whose response is untuned. A further test is feasible through experimental studies of the nonlinear behavior at the apex, for which our theory predicts (iv′) a moderate compressive nonlinearity in hair-bundle motion and therefore in tectorial-membrane motion, but no more than a weak nonlinearity in the basilar membrane’s response. Finally, and beyond the theory presented in this article, the ratchet mechanism should allow for traveling waves in the tectorial membrane (42) that are unidirectionally coupled to basilar membrane waves.

The Ratchet Principle.

The ratchet mechanism constitutes a general design principle for mechanical amplification whereby the output does not feed back onto the input. In this way, it represents a mechanical analogue of the operational amplifier from electrical engineering (28). Although the current technology of signal detectors such as microphones relies on electrical amplification, mechanical amplification could improve signal-to-noise ratios and thereby greatly advance sensitivity and detection of weak signals. The ratchet mechanism thus opens a path for implementing controlled mechanical amplification in engineering applications.

Materials and Methods

Hydrodynamics.

By combining continuity equations and fluid-momentum equations, we describe the cochlea’s hydrodynamics with the partial differential equation

|

[4] |

Here ρ denotes the density of liquid in the cochlea, L the length of the cochlea, h the height of the scalae, and p and XBM, respectively, the pressure across and the displacement of the basilar-membrane at position r and time t. The coefficient Λ accounts for friction due to fluid motion. Position is measured in units of the cochlear length, such that r = 0 corresponds to the basal and r = 1 to the apical end. The pressure translates into an external force acting on the basilar membrane and yields a displacement that we compute employing the model of Fig. 2B (SI Text). Temporal Fourier transformation yields an ordinary differential equation that we solve numerically with the shooting method in Mathematica 7 (Wolfram Research). We apply two boundary conditions. First, p = p0 at r = 0: a sound-evoked pressure p0 acts at the stapes. And second, p = 0 at r = 1: because the two scalae communicate at the helicotrema, the pressure difference between them vanishes at the apical end of the cochlea.

Tuning Curves of Auditory-Nerve Fibers.

Tuning curves of auditory-nerve fibers are computed by assuming that the hearing threshold corresponds to a root-mean-square deflection of the hair bundles of inner hair cells by 0.3 nm. These bundles are thought to be coupled by fluid motion to the shearing between the reticular lamina and tectorial membrane and thus to the displacement of the hair bundles of OHCs (SI Text).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank S. Leibler for discussion, the two reviewers for valuable suggestions, and the members of our research group for comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DC00241 and a Alexander von Humboldt Foundation fellowship (to T. R). A. J. H. is an Investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0914345107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lighthill J. Energy flow in the cochlea. J Fluid Mech. 1981;106:149–213. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mammano F, Nobili R. Biophysics of the cochlea: Linear approximation. J Acoust Soc Am. 1993;93:3320–3332. doi: 10.1121/1.405716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shera CA, Tubis A, Talmadge CL. Do forward- and backward-traveling waves occur within the cochlea? Countering the critique of Nobili et al. JARO. 2004;5:349–359. doi: 10.1007/s10162-004-4038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siebert WM. Stimulus transformations in the peripheral auditory system. In: Kolers PA, Eden M, editors. Recognizing Patterns. Cambridge: MIT; 1968. pp. 104–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zweig G. In Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quan Biol. Vol. 40. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1976. Basilar membrane motion; pp. 619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidu RC, Mountain DC. Measurements of the stiffness map challenge a basic tenet of cochlear theories. Hear Res. 1998;124:124–131. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00133-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiang NYS, Liberman MC, Sewell WF, Guinan JJ. Single unit clues to cochlear mechanics. Hear Res. 1986;22:171–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(86)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ulfendahl M. Mechanical responses of the mammalian cochlea. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;53:331–380. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temchin AN, Rich NC, Ruggero MA. Threshold tuning curves of chinchilla auditory-nerve fibers. I. Dependence on characteristic frequency and relation to the magnitudes of cochlear vibrations. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2889–2898. doi: 10.1152/jn.90637.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper NP, Rhode WS. Nonlinear mechanics at the apex of the guinea-pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1995;82:225–243. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zinn C, Maier H, Zenner HP, Gummer AW. Evidence for active, nonlinear, negative feedback in the vibration response of the apical region of the in vivo quinea-pig cochlea. Hear Res. 2000;142:159–183. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robles L, Ruggero MA. Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1305–1352. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper NP, Rhode WS. Basilar membrane mechanics in the hook region of cat and guinea-pig cochlea: Sharp tuning and nonlinearity in the absence of baseline position shift. Hear Res. 1992;63:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggero MA, Rich NC, Recio A, Narayan SS, Robles L. Basilar-membrane responses to tones at the base of the chinchilla cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 1997;101:2151–2163. doi: 10.1121/1.418265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khanna SM, Hao LF. Reticular lamina vibrations in the apical turn of a living guinea pig cochlea. Hear Res. 1999;132:15–33. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhode WS, Cooper NP. Nonlinear mechanics in the apical turn of the chinchilla cochlea in vivo. Audit Neurosci. 1996;3:101–121. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin P, Hudspeth AJ. Active hair-bundle movements can amplify a hair cell’s response to oscillatory mechanical stimuli. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14306–14311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin P, Hudspeth AJ, Jülicher F. Comparison of a hair bundle’s spontaneous oscillations with its response to mechanical stimulation reveals the underlying active process. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14380–14385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251530598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Force generation by mammalian hair bundles supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–883. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan DK, Hudspeth AJ. Ca2+ current-driven nonlinear amplification by the mammalian cochlea in vitro. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nn1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadrowski B, Martin P, Jülicher F. Active hair-bundle motility harnesses noise to operate near an optimum of mechanosensitivity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12195–12200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403020101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudspeth AJ. Making an effort to listen: Mechanical amplification in the ear. Neuron. 2009;59:530–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J, et al. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–155. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dallos P, Zheng J, Cheatham MA. Prestin and the cochlear amplifier. J Physiol. 2006;576:37–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashmore J. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong X, Ospeck M, Iwasa KH. Piezoelectric reciprocal relationship of the membrane motor in the cochlear outer hair cell. Biophys J. 2002;82:1254–1259. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans BN, Dallos P. Stereocilia displacement induced somatic motility of cochlear outer hair cells. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8347–8351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horowitz P, Hill W. The Art of Electronics. 2nd Ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge Univ Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sziklai I. The significance of the calcium signal in the outer hair cells and its possible role in tinnitus of cochlear origin. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261:517–525. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwislocki JJ, Kletsky EJ. Tectorial membrane: Apossible effect on frequency analysis in the cochlea. Science. 1979;204:639–641. doi: 10.1126/science.432671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gummer AW, Hemmert W, Zenner HP. Resonant tectorial membrane motion in the inner ear: its crucial role in frequency tuning. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8727–8732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai H, Shoelson B, Chadwick RS. Evidence of tectorial membrane radial motion in a propagating mode of a complex cochlear model. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6243–6248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401395101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos-Sacchi J. On the frequency limit and phase of outer hair cell motility: effects of the membrane filter. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1906–1916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01906.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Housley GD, Ashmore JF. Ionic currents of outer hair cells isolated from the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol. 1992;448:73–98. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engel J, et al. Two classes of outer hair cells along the tonotopic axis of the cochlea. Neuroscience. 2006;143:837–849. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhode WS. Observations of the vibration of the basilar membrane in squirrel monkeys using the Mössbauer technique. J Acoust Soc Am. 1971;49:1218–1231. doi: 10.1121/1.1912485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nuttall AL, Dolan DF. Steady-state sinusoidal velocity responses of the basilar membrane in guinea pig. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;99:1556–1565. doi: 10.1121/1.414732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mellado Lagarde MM, Drexl M, Lukashkina VA, Lukashkin AN, Russell IJ. Outer hair cell somatic, not hair bundle, motility is the basis of the cochlear amplifier. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:746–748. doi: 10.1038/nn.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dallos P, et al. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhode WS, Cooper NP. Fast traveling waves, slow traveling waves and their interactions in experimental studies of apical cochlear mechanics. Audit Neurosci. 1996;2:289–199. [Google Scholar]

- 41.International Team for Ear Research. Cellular vibration and motility in the organ of Corti. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 1989;467(Suppl):1–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghaffari R, Aranyosi AJ, Freeman DM. Longitudinally propagating traveling waves of the mammalian tectorial membrane. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16510–16515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703665104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.