Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) affects at least 3% of the population above the age of 50 and is the precursor to multiple myeloma (MM), an incurable malignancy of plasma cells. Recent advances in MGUS include: an improved understanding of the pathogenesis of MGUS and its progression to MM, involving molecular events intrinsic to the malignant plasma cell as well as the microenvironment; novel techniques to assess risk for progression to MM using serum-free light-chain analysis and immunophenotyping; and a renewed interest in chemoprevention of MM. In the future, continued improvement in our understanding of MGUS will lead to the development of better biomarkers for prognosis and therapies for chemoprevention of MM.

Keywords: MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, pathogenesis

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a common condition in the general population, affecting at least 3% of patients over 50 years of age, and it is the precursor to multiple myeloma (MM) [1]. MGUS is diagnosed when a monoclonal protein is detected in serum without clinical evidence of MM, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, primary amyloidosis, lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia [2]. The diagnosis of MGUS is usually made incidentally when evaluating the patient for nonspecific symptoms or signs, such as fatigue, bone pain, anemia or renal failure. In 1961, Jan Waldenström initially reported finding a monoclonal protein without evidence of a malignant disorder, and named the condition ‘essential hypergammaglobulinemia’ [3]. His description emphasized the stability of the level of the monoclonal protein over time, which is contrasted to the increasing levels seen in MM. For some time, this condition was was also referred to as ‘benign monoclonal gammopathy’. However, Robert Kyle recognized that determining the potential of MGUS to progress to a malignancy was only possible with serial follow-up [4]. Thus, he coined the term ‘monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance’. The diagnostic criteria for monoclonal gammopathies were recently formalized by the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) (Table 1) [2].

Table 1.

International Myeloma Working Group Criteria for the diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and asymptomatic (smoldering) multiple myeloma.

| Parameter | Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance | Asymptomatic (smoldering) multiple myeloma |

|---|---|---|

| Serum monoclonal protein | <3 g/dl | ≥3 g/dl |

| and | and/or | |

| Bone marrow plasma cells | <10% | ≥10% |

| Myeloma-related organ or tissue impairment† | Absent | Absent |

The ‘CRAB’ criteria: hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia and bone lesions.

In recent years, there have been numerous advances in the understanding of MGUS in the areas of pathogenesis, diagnosis, epidemiology and prognosis. New insights into the molecular and microenvironmental events that contribute to the pathogenesis of MM have been discovered. The serum-free light-chain (sFLC) assay has improved the sensitivity of detection of monoclonal gammopathies – including the identification of light-chain MGUS (LC-MGUS) – and added a useful prognostic tool for patients with MGUS. Several epidemiologic studies have revealed important insights into the racial and familial distribution of MGUS, suggesting a genetic component to the etiology of this disorder. The importance of MGUS in the pathogenesis of MM has recently been clarified. sFLC analysis and immunophenotyping of bone marrow plasma cells have been shown to be useful methods for assessing prognosis in MGUS. Regarding the epidemiology of MGUS, the reader is referred to recent extensive reviews [5,6].

It is now apparent that there are at least two kinds of premalignant MGUS tumors that are associated with a selective expansion of monoclonal lymphoplasmacytic cells or monoclonal plasma cells, respectively [7]. Most lymphoplasmacytic monoclonal tumors secrete IgM, whereas plasma cell tumors rarely (~1%) express IgM and, instead, usually have undergone IgH switch recombination that results in secretion of monoclonal IgG, IgA, IgD, IgE or monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains. The normal cell that corresponds to plasma cell tumors is a long-lived plasma cell that has undergone extensive somatic hyper-mutation and antigen selection of immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain genes, has undergone productive IgH switch recombination, and is localized in the bone marrow [8]. Although much is known regarding the molecular pathogenesis of plasma cell tumors (see later), the molecular genetic abnormalities of lymphoplasmacytic tumors have proven elusive thus far [9]. In general, IgM MGUS is assumed to be associated with lymphoplasmacytic tumors, whereas non-IgM MGUS is assumed to be associated with a plasma cell tumor, although a definitive diagnosis should include histopathology of the bone marrow. The remainder of this review is focused on non-IgM/plasma cell-associated MGUS.

Pathogenesis of MGUS & MM

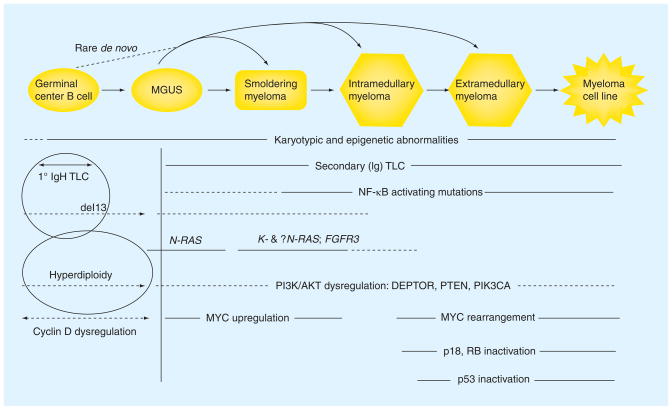

There have been significant advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of MGUS and MM over the past decade, and several excellent reviews have been published [8,10,11]. A model for the pathogenesis of MGUS and MM is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multistep model for the molecular pathogenesis of MGUS and myeloma.

Four early, partially overlapping oncogeneic events (cyclin D dysregulation, hyperdiploidy, chromosome 13 deletion, and primary IgH translocations) are shared by MGUS and MM tumors. The relative timing of these four events is not fully understood, although primary IgH translocations are thought to occur in germinal center B cells. Other oncogenic events are thought to occur later, and mostly in MM tumors, but sometimes are found in MGUS tumors. Late oncogenic events (e.g., MYC rearrangement and p53 activation) appear to occur mainly in advanced MM tumors. Estimates of the timing of various events are indicated by solid and dashed (reflecting less certainty) lines. See text for additional details. MGUS: Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM: Multiple myeloma.

The etiologic factors for the development of MGUS remain unclear. There is significant support for genetic susceptibility, based on familial aggregation and ethnic disparities [6,12–14]. Environmental exposures, such as occupation, radiation and pesticides, have all been studied [15–18]. The most consistent relationship with the development of myeloma appears to be with pesticide exposure [16]. It is also possible that immune dysregulation plays an important role in the development of monoclonal gammopathies. Monoclonal gammopathies appear in various settings of immune dysregulation, including autoimmune diseases, HIV and following solid-organ transplantation [19]. In these settings, MGUS may resolve with immune reconstitution [20]. In addition, specific antigenic targets have been associated with the development of MGUS, such as paratarg-7 [21].

There are four early oncogenic events that lead to the expanded plasma cell population found in MGUS and MM. These events are partially overlapping and the exact timing of these events remains unclear. First, there is nearly universal dysregulation of cyclin D1, -2 or -3, or inactivation of RB-1 [22]. Second, there are primary translocations involving the immunoglobulin locus (14q32), which occur in approximately 40% of MM tumors [23]. Seven primary translocations form three groups: the 4p16 group (MMSET and FGFR3); a cyclin D group, 6p21 (CCND3), 11q13 (CCND1) and 12p13 (CCND2); and a MAF group, 8q24.3 (MAFA), 16q23 (c-MAF) and 20q11 (MAFB) [10,24]. Even cytogenetic abnormalities that are associated with a poor prognosis in MM, such as t(4;14) and t(14;16), can be detected in MGUS and smoldering MM (SMM), albeit at a lower frequency [24]. Third, roughly half of MGUS and MM tumors show hyperdiploidy, which is associated with multiple trisomies of eight odd-numbered chromosomes but rarely with primary IgH translocations [25]. Fourth, there is a loss of chromosome 13, which is the single most common genetic abnormality and is found in approximately 50% of MM tumors but a somewhat lower fraction of MGUS tumors [24–26].

Importantly, it is critical to understand that the majority of all genetic changes identified in MM are also present in MGUS, so that it is not possible to distinguish MGUS tumor cells from MM tumor cells, whereas advanced MM tumors have molecular genetic abnormalities that rarely, if ever, are found in MGUS tumors (e.g., p18 homozygous deletion and p53 deletion) [24,27]. The specific oncogenic events that are associated with progression from MGUS to MM remain unclear. Translocations involving Myc, which are present in 90% of human myeloma cell lines, are rare in MGUS, but are detected with increasing frequency – often associated with heterogeneity within the population of tumor cells – in MM (15%) and advanced MM (44%) [28]. Thus, it was proposed that rearrangements and the consequent dysregulation of MYC are late progression events that occur as tumors become more proliferative and less stromal cell dependent. Recently, however, it was shown that induction of MYC dysregulation in mice that have MGUS led to the development of MM in the majority of them, which also suggests a role for MYC in the MGUS to MM transition [29]. Consistent with this idea, there is a significant increased expression of MYC in MM compared with MGUS tumors, so that dysrsegulation of MYC may be involved at both early and late stages of pathogenesis (Figure 1). Mutations of N- or K-RAS occur with a similar frequency in up to 40% of MM tumors, but are present in less than 10% of MGUS tumors. It may be significant that only N-RAS mutations have been reported in MGUS tumors thus far, thereby suggesting nonidentical roles of N- and K-RAS mutations in pathogenesis, and perhaps a unique role of K-RAS mutations that can mediate the progression from MGUS to MM for some tumors (Figure 1) [30–32]. Epigenetic changes may also play a role in the progression of MGUS to MM [33]. Preliminary data have demonstrated the increased expression of several miRNAs in MGUS compared with normal plasma cells, and several other miRNAs with increased expression in MM but not MGUS [34].

Factors extrinsic to the clonal plasma cell (e.g., bone marrow microenvironment and immune function) are also potential contributors to progression. Increasing bone marrow angiogenesis has been shown with advancing disease states along the MGUS to MM spectrum [35]. In addition, a loss of the ability to inhibit angiogenesis also seems to occur with disease progression [36]. Although the development of bone disease clearly differentiates MGUS from MM clinically, it is also clear that there is evidence of increased bone resorption in MGUS, based on bone morphometric studies [37], elevation of bone resorption markers [38] and an increased risk of fractures in the axial skeleton [39]. However, whether the cycle of osteoclast activation, bone resorption and myeloma cell growth are a cause or a consequence of MGUS progression remains unclear [40]. Specific immune factors, such as loss of immunity to SOX2 and OFD1, may also be important in the progression from MGUS to MM [41,42].

Utility of SFLC analysis

A significant advance in the diagnosis of monoclonal gammopathies has been the development of sFLC analysis. The standard tests for the evaluation of monoclonal gammopathies, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) and immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE), are useful for the majority of patients with MM, but are inadequate or suboptimal for the evaluation of the majority of patients with primary amyloidosis, oligosecretory or nonsecretory myeloma and light-chain myeloma [43]. sFLC analysis (Freelite™, The Binding Site, Inc., Birmingham, UK) measures the concentration of free κ and λ light chains through polyclonal antibodies directed at epitopes that are exposed only when free of the intact immunoglobulin [44]. The serum concentration of light chains is dependent on both the production by plasma cells and renal clearance; therefore, the clinical context is critical to the interpretation of the assay. The ratio of κ:λ is critical to the interpretation, because an abnormal serum-free light ratio should only be present in the context of a plasma cell dyscrasia or other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. In addition, it is important to note that sFLC analysis is much more sensitive than the other techniques for the detection of monoclonal light chains. The sensitivity for light chains by SPEP, IFE and sFLC are 1–2 g/l, 150–500 mg/l and 1 mg/l, respectively [45]. The IMWG has published guidelines for the use of sFLC analysis in the evaluation of MM and related disorders [46]. The addition of sFLC to the traditional tests is recommended during the initial evaluation of all patients with a suspected plasma cell dyscrasia. This is based on a screening study performed on 428 patients from the Mayo Clinic database with a positive urine IFE [47]. If SPEP and serum IFE alone were used, 28 patients (6%) would have had a missed diagnosis of a plasma cell dyscrasia, including four with MM and 19 with primary amyloidosis. If sFLC analysis had been used as the only test, 14% of patients would have had a missed diagnosis. However, if all three tests had been used, 99.5% of patients would have been diagnosed with a plasma cell dyscrasia. The two missed patients had MGUS, one of which had ‘LC-MGUS’, a newly described MGUS subtype.

Among patients with newly diagnosed MM, 16% produce a monoclonal light-chain only (light-chain MM) and 3% produce no monoclonal protein (nonsecretory MM) [48]. Therefore, the nature of the precursor state in these entities may be detectable with sFLC analysis, if, in fact, these disorders evolve from a LC-MGUS. The Mayo Clinic were the first to describe the prevalence of LC-MGUS, defined as the presence of an abnormal sFLC ratio and a negative IFE for immunoglobulin heavy chain [49]. Among 16,637 persons age 50 years or older, LC-MGUS was detected in 2% of patients. In this cohort, four patients have developed MM and two patients have developed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Light-chain MGUS was also detected in six out of 30 patients with MM, for whom pre-diagnostic serum were available from the US Department of Defense (DoD) Serum Repository [50]. Four patients developed light-chain MM and two patients developed intact immunoglobulin MM. This limited data on LC-MGUS suggests that it is probably a legitimate premalignant entity, which may evolve to light-chain MM, intact immunoglobulin MM and other related B-cell malignancies; however, more information on its prevalence and natural history is needed.

Thus, it is clear that sFLC analysis increases the sensitivity for the detection of plasma cell dyscrasias and is particularly important in the evaluation and monitoring of patients with oligosecretory and light-chain MM, as well as amyloid light chain amyloidosis. A provisional MGUS subtype, LC-MGUS, has been revealed by this test. Last, sFLC analysis has a specific application for the assessment of prognosis in MGUS, which will be described in detail later.

Progression of MGUS to MM

The reasons for progression of MGUS to MM remain unknown, and possible events intrinsic and extrinsic to the malignant plasma cell were described earlier [51]. Until recently, a fundamental question about the pathogenesis of MM remained unanswered: are all myelomas preceded by MGUS? Historically, approximately a third of patients with myeloma were thought to evolve from a prior MGUS or SMM [48]. However, this estimate comes from patients who were known to have MGUS/SMM, and given that these disorders are, by definition, asymptomatic, this is probably an underestimate. Some investigators have suggested that myelomas with a prior MGUS/SMM have a different gene-expression profile and a different response and outcome with therapy [52–54]. The limitation of all these studies was that MGUS/SMM were defined clinically and not comprehensively with prediagnostic serum analyses for monoclonal immunoglobulin.

Recently, our group has demonstrated that virtually all myelomas arise from MGUS [50]. We crossreferenced MM patients treated with autologous stem cell transplantation at Walter Reed Army Medical Center with the DoD Serum Repository to obtain prediagnostic sera. The DoD Serum Repository contains serum collected every 2 years on all US military service members. SPEP, IFE and sFLC analysis were performed on all sera collected 2 or more years prior to the diagnosis of MM to detect MGUS/SMM. In 30 patients, 110 prediagnostic samples were available from 2.2–15.3 years prior to diagnosis. MGUS was detected in 27 out of 30 patients (90%) – by SPEP and/or IFE in 21 patients (77.8%) and by sFLC in six patients (22.2%). The three patients without a detectable MGUS were unlikely to be detected as one patient with IgG myeloma had only one sample 9 years prior to diagnosis and the remaining two patients had IgD-myeloma, which is characterized by very low levels of immunoglobulin secretion. Thus, given additional serial samples, and the availability of more sensitive detection techniques for IgD myeloma, we suspect that a MGUS might have been detected in all patients. Our results have been confirmed in another independent study by Landgren and colleagues. They obtained prediagnostic sera from 71 patients with MM in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial [55]. In this study, containing serum from 2 to 9.8 years prior to diagnosis, nearly 100% of patients had a preceding MGUS. The PLCO study differs from the military study in that the latter included nearly 50% African–Americans and only one woman (3%). In addition, the median age of patients in the latter study was nearly 20 years less than in the PLCO study or in most MM patient cohorts that have been studied in other settings.

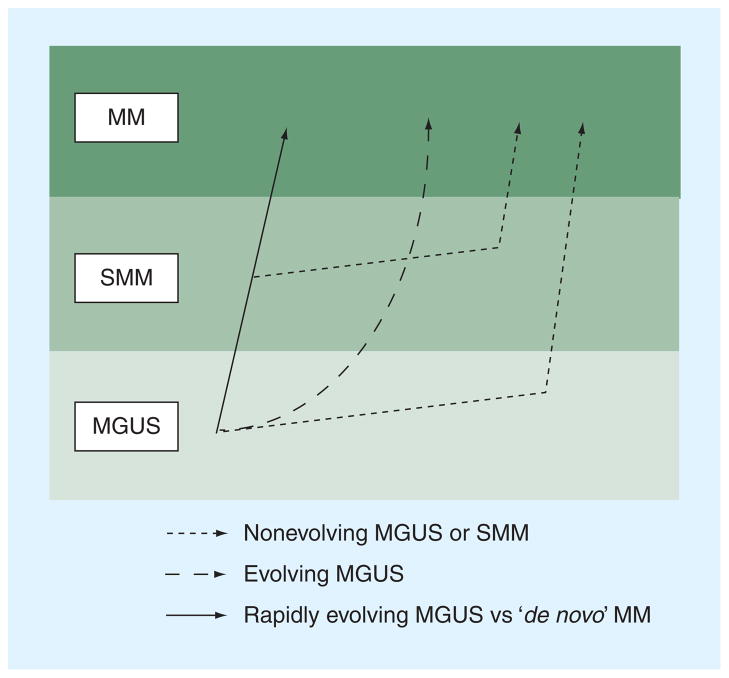

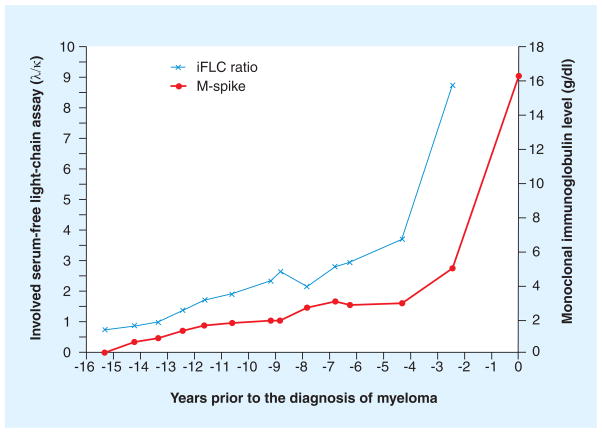

The patterns of changes in the monoclonal protein prior to the development of myeloma have been described [19,50,56,57]. There appears to be at least four patterns of progression (Figure 2) [1]: a non-evolving MGUS or SMM [2], which is characterized by a very stable monoclonal protein followed by a rapid increase prior to the development of symptomatic MM, an evolving type, which is characterized by a steady increase in the monoclonal protein until the MM develops [3], and a rapidly evolving MGUS, in which there is a relatively short period of MGUS (<5 years) prior to the development of MM [4]. Another pattern that has emerged that requires further study involves the serial changes in sFLCs. In the DoD, several patients displayed a dramatic change in the sFLC ratio without a significant change in the monoclonal protein several years prior to the diagnosis of MM (one example is depicted in Figure 3). Thus, serial changes in the sFLC ratio may signal the onset of MM in some patients. This result seems consonant with the fact that the presence of an abnormal sFLC ratio is associated with an increased probability that MGUS will progress to MM (see later).

Figure 2. Proposed models for the patterns of the MGUS to MM progression.

MGUS: Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; MM: Multiple myeloma; SMM: Smoldering multiple myeloma. Redrawn with permission from [51], Nature Publishing Group.

Figure 3. Abnormal serum-free light-chain ratio may signal the onset of multiple myeloma.

Modified with permission from [50].

Novel strategies to assess prognosis in MGUS

Studies evaluating the progression of MGUS to MM and related disorders have demonstrated an average rate of progression of 1% per year [56]. The rate of progression can be affected by several factors, including the level of monoclonal protein, the immunoglobulin isotype, the percentage of bone marrow plasma cells and the presence of polyclonal hypogammaglobulinemia [58]. Improved techniques to risk-stratify patients for progression would be useful for patient counseling and determining an optimal interval for monitoring. Moreover, the identification of high-risk groups for progression would facilitate the design of clinical trials for chemoprevention of MM. Both sFLC analysis and immunophenotyping of bone marrow plasma cells have been studied to risk-stratify patients for malignant progression.

Abnormal sFLC ratios are seen in 30–40% of patients with MGUS [59,60], 90% of patients with SMM [61] and 95% of patients with symptomatic MM [62]. Furthermore, an abnormal sFLC ratio was seen in 70–80% of patients prior to the diagnosis of MM in both the DoD and PLCO studies [50,55]. Thus, excess production of sFLCs has been proposed as a surrogate for expansion of the malignant plasma cell clone. The Mayo Clinic assessed the utility of sFLC analysis on 1148 patients with MGUS with a median follow-up of 15 years [60]. The risk of progression at 20 years with an abnormal sFLC ratio was 35% compared with 13% with a normal sFLC ratio. The investigators combined this with other known risk factors for progression to develop an easily applied clinical model using the following adverse factors for progression: monoclonal protein above 1.5 g/dl, non-IgG isotype and abnormal sFLC ratio (Table 2).

Table 2.

A comparison of two models for risk stratification in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

| Mayo clinic risk stratification model† | Salamanca risk stratification model‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk group | Patients (%) | Annual risk of progression (%) | Risk group | Patients (%) | Annual risk of progression (%) |

| Low (no factors) | 39 | 0.3 | Low (no factors) | 46 | 0.4 |

| Low intermediate (any one factor) | 37 | 1.1 | Intermediate (any one factor) | 48 | 2 |

| High intermediate (any two factors) | 20 | 1.9 | High (two factors) | 6 | 9.2 |

| High (any three factors) | 4 | 2.9 | |||

Adverse risk factors for progression: serum M-protein ≥1.5 gm/dl, nonIgG isotype, abnormal sFLC ratio.

Adverse risk factors for progression: >95% aberrant PC/BMPC, presence of aneuploidy.

BMPC: Bone marrow plasma cell; PC: Plasma cell; sFLC: Serum-free light chain.

Immunophenotyping is an attractive technique to potentially identify high levels of malignant plasma cells amidst normal plasma cells, a situation that is probably common in MGUS [63]. The Salamanca group first reported that monoclonal plasma cells express a distinct immunophenotype by flow cytometry: CD38+, CD19−, CD45− and CD56+ [64]. These monoclonal plasma cells, which are immunophenotypically similar to plasma cells from MM patients, can be detected among the total plasma cell population in patients with MGUS, albeit at a low frequency. The investigators reported that it was rare for patients with MM to have more than 3% polyclonal plasma cells by flow cytometry. Thus, flow cytometry may be useful in identifying MGUS patients with a high proportion of monoclonal plasma cells. Persona and colleagues reported on the risk of progression in 407 MGUS patients and 97 SMM patients based on multiparameter flow cytometry using a panel of CD38, CD45, CD19 and CD56 antibodies [65]. They defined an aberrant plasma cell phenotype as greater than 95% of bone marrow plasma cells being CD38+, but CD45− and/or CD19−, and/or CD56+. The most common aberrant phenotypic profile is CD45− and CD19− and CD56+, which occurs in half of patients with an aberrant profile. With a median follow-up time of 56 months, patients who had MGUS and an aberrant immunophenotypic profile had a 25% risk of progression to myeloma at 5 years in contrast to a 5% risk of progression at 5 years for those without the aberrant expression. In patients with SMM, those with an aberrant phenotypic profile had a 64% risk of progression at 5 years in contrast to an 8% risk without the aberrant phenotype. The authors constructed a risk stratification model for both MGUS and SMM (Table 2). The aberrant immunophenotypic profile was an independent prognostic factor in both MGUS and SMM, but aneuploidy was the additional risk factor for MGUS and immunoparesis was the additional risk factor for SMM.

Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages for the risk stratification of patients with MGUS. The Mayo Clinic model is based on a large dataset with the longest median follow-up. In addition, the factors in this model can be determined using peripheral blood tests for relatively low cost. Given that the majority of patients with MGUS will not undergo a bone marrow aspirate, this model is easily applied in the clinic. The disadvantages of the Mayo Clinic model are its poor discrimination of the risk of progression between the groups. Even the highest-risk group has an annual risk of progression of only 3%, which limits the model’s utility to identify a group for closer interval follow-up or trials for chemoprevention. The biologic basis for an abnormal sFLC ratio as a surrogate for malignant progression remains speculative, which also weakens this model. The Salamanca model, on the other hand, has a very strong biologic basis because it quantifies the ‘load’ of malignant plasma cells among the normal plasma cells by immunophenotyping and the presence of aneuploidy. It has a superior ability to identify a truly high-risk population, with an annual risk of progression of nearly 10%, in comparison to the Mayo Clinic model. However, the Salamanca model’s major disadvantages are invasiveness (it requires a bone marrow aspirate), technical complexity and cost. A limitation of both studies is the ethnic homogeneity, a major problem for translation to the clinic. In summary, the Mayo Clinic model may be useful in routine clinical practice, assuming it is validated in other patient populations, but the Salamanca model is a superior model for use in research, in particular, to identify a truly high-risk MGUS population that is suitable for trials of chemoprevention.

Preventive therapies in MGUS

The existence of easily identifiable precursor states to MM, MGUS and SMM, represents an opportunity for chemoprevention. Although modern therapies (autologous transplant, thalidomide, lenalidomide and bortezomib) appear to have increased survival, myeloma remains mostly incurable [66,67]. The opportunity to prevent or delay the development of MM would be a significant advance in the management of these plasma cell dyscrasias. Studies to date in this area have suffered from significant limitations: the inability to define a uniformly high-risk population for progression, use of nonstandard inclusion criteria, use of nonuniform response criteria and the availability of agents with sufficient efficacy and acceptable toxicity to be used in this setting. Three agents, thalidomide, anakinra and curcumin, have been studied in SMM and MGUS, but only the trials with thalidomide have sufficient follow-up to be informative [68–71].

Two single-arm studies have been reported using thalidomide in patients with SMM. The initial report by the Mayo Clinic enrolled patients with SMM and ‘indolent MM’ [69]. The patients were started on 200 mg daily with the intention of increasing to 800 mg. The overall response rate was 66%, with a median follow-up of 2 years, the median progression-free survival had not been reached. The University of Arkansas reported on 76 patients with SMM treated with thalidomide at 200 mg daily (as well as pamidronate) [68]. The overall response rate in this trial was 63%, including 17% of patients with complete response/near-complete response, using standard European Bone Marrow Transplant response criteria. The median time to progression was an impressive 7 years. The median time to progression for patients with SMM who are observed is between 3.2 and 4.8 years [72,73]. Another very interesting finding in this trial was the observation that patients who achieved a partial remission or better had a shorter event-free survival and time to myeloma therapy. This finding suggests more proliferative tumors were more likely to respond. In addition, the median survival postprogression after thalidomide was greater than 5 years. This finding is somewhat reassuring given the concern for the development of drug resistance. The interim results of a randomized Phase III trial of lenalidomide and dexamethasone compared with therapeutic abstention in patients with high-risk SMM were recently reported [74,101]. At a median follow-up of 16 months among the first 40 patients enrolled, there have been no progressions in the treatment arm and eight progressions in the therapeutic abstention arm. In patients who have completed the full planned 9 months of therapy, the overall response rate was 100%, including 47% with a very good partial response. It is difficult to compare these trials of chemoprevention of MM given their differing eligibility criteria, sample size and length of follow-up. However, it appears that drugs active in the treatment of symptomatic myeloma when administered to patients with SMM may delay development of symptomatic myeloma.

Clinical management of MGUS

Recently, the UK Myeloma Forum and the Nordic Myeloma Study Group have proposed guidelines for the management of MGUS [75]. These guidelines are almost entirely based on expert consensus opinion rather than prospective clinical trials. For the purposes of management, they suggest dividing patients into low- and high-risk groups. The low-risk group is defined by a serum IgG M-protein below 1.5 g/dl or IgA or IgM less than 1.0 g/dl. This group can be monitored in the primary-care setting at intervals of 3–4 months initially (for the first year) and then lengthened to 6–12 months based on the patient’s clinical history, laboratory results and comorbid conditions. The higher risk group is defined as IgG M-protein above 1.5 g/dl, IgA or IgM above 1.0 g/dl or IgD or IgE at any level. These patients should be monitored by a hematologist at shorter intervals, perhaps three- to four-times per year. The recommended tests for monitoring include SPEP, serum total immunoglobulins, complete blood count, creatinine, urea, electrolytes and serum calcium.

The guidelines specifically state that there is no evidence supporting the use of sFLC in monitoring patients. By contrast, the IMWG guidelines for the use of sFLC analysis recommend its use at diagnosis for all patients with MGUS to assess prognosis [46]. However, sFLC analysis may be a useful adjunctive test in monitoring patients with MGUS based on two lines of evidence. First, the initial Mayo Clinic study describing the impact of sFLC on the risk of progression to MM demonstrated that an increasingly extreme sFLC ratio increased the risk of progression to MM. Second, in the DoD Serum Repository Study, the development of an abnormal sFLC ratio in the context of a minimally changing serum M-protein level signaled the onset of myeloma within 2–4 years. Thus, the development of an abnormal or increasingly abnormal sFLC ratio may herald the onset of symptomatic MM, and a closer interval of follow-up may be indicated in these patients; however, additional studies are needed to validate a role for sFLC assays for all MGUS patients. Our current practice is to perform sFLC analysis at all monitoring visits and for patients who develop marked changes in the sFLC ratio closer observation or additional tests are considered.

Expert commentary

Our understanding of monoclonal paraproteins, from Waldenström’s ‘essential hypergammaglobulinemia’ to Kyle’s ‘monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance’, continues to evolve. The availability of novel tests, such as sFLC analysis and immunophenotyping of bone marrow plasma cells, hold promise for determining the significance of an individual patient’s MGUS with regards to its potential for malignant progression. However, there are certainly other factors involved in the progression from MGUS to MM that deserve further study. This includes a better understanding of the role of the microenvironment in progression, including angiogenesis, bone marrow stromal cell interactions and the role of bone metabolism. Future studies need to evaluate biomarkers associated with these processes, which will hopefully yield many new insights into the biology and clinical management of MGUS. The era of personalized medicine has arrived and the ability to more accurately assign prognosis in MGUS would have significant value to patients and lead to more optimal strategies for evaluation and monitoring. In addition, these studies may lead to new targets for the prevention of symptomatic myeloma. This is of major importance given the incurable nature of MM. Currently, available agents that are active in MM are, aside from lenalidomide, not suitable for chemoprevention, making the identification of other targets of great interest. The epidemiology of MGUS deserves further study, notably, in populations of younger ages and diverse ethnic backgrounds. Insights from these studies will lead to a better understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of MGUS and MM.

Five-year view

In 5 years, improved techniques for the prognostication of MGUS/SMM may be available through the identification of novel biomarkers. There should be a better understanding of the pathogenesis of the progression of MGUS to MM, which might allow for the identification of potential agents for chemoprevention. Preliminary results of currently planned studies of prevention in patients with SMM will be available. Results from larger epidemiologic studies on populations that are ethnically diverse and span a wider age range will inform the community on the societal burdens of MGUS.

Key issues

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is one of the most common premalignant conditions, affecting more than 3% of those over the age of 50 years.

There are striking differences in the prevalence and clinical features of MGUS among different racial and ethnic groups, as well as familial aggregation supporting a role for genetic factors in the pathogenesis of MGUS and multiple myeloma (MM).

Serum-free light-chain analysis is a useful tool for the diagnosis and assessment of prognosis of MGUS.

Virtually all patients with MM have a preceding MGUS.

The reasons for progression from MGUS to MM remain unknown.

MM remains incurable and given the universal existence of a premalignant state, chemoprevention trials are of major interest.

The standard of care for MGUS/smoldering MM remains careful clinical observation for evidence of progression to symptomatic MM.

Footnotes

For reprint orders, please contact reprints@expert-reviews.com

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, nor the US Government. W Michael Kuehl is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Other research support was provided by The Binding Site, Inc., Birmingham, UK. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Brendan M Weiss, Email: brendan.weiss@us.army.mil, Hematology-Oncology Service, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, 6900 Georgia Avenue, N.W., Washington, DC 20307, USA, Tel.: +1 202 782 5773, Fax: +1 202 782 3256.

W Michael Kuehl, Genetics Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. Prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1362–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121(5):749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldenstrom J. Studies on conditions associated with disturbed γ globulin formation (gammopathies) Harvey Lect. 1960;56:211–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyle RA. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Natural history in 241 cases. Am J Med. 1978;64(5):814–826. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90522-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Epidemiology of the plasma-cell disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20(4):637–664. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landgren O, Weiss BM. Patterns of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and multiple myeloma in various ethnic/racial groups: support for genetic factors in pathogenesis. Leukemia. 2009;23(10):1691–1697. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC; Lyon, France: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8 ••.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(3):175–187. doi: 10.1038/nrc746. Comprehensive review of the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma (MM), which is an essential starting point for understanding this disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vijay A, Gertz MA. Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood. 2007;109(12):5096–5103. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10 •.Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Molecular pathogenesis and a consequent classification of multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(26):6333–6338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.021. Synthesizes molecular findings in MM into a molecular classification. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hideshima T, Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM, Anderson KC. Advances in biology of multiple myeloma: clinical applications. Blood. 2004;104(3):607–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vachon CM, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, et al. Increased risk of monoclonal gammopathy in first-degree relatives of patients with multiple myeloma or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2009;114(4):785–790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristinsson SY, Goldin LR, Bjorkholm M, Koshiol J, Turesson I, Landgren O. Genetic and immune-related factors in the pathogenesis of lymphoproliferative and plasma cell malignancies. Haematologica. 2009;94(11):1581–1589. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.008979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristinsson SY, Bjorkholm M, Goldin LR, et al. Patterns of hematologic malignancies and solid tumors among 37,838 first-degree relatives of 13,896 patients with multiple myeloma in Sweden. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(9):2147–2150. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baris D, Silverman DT, Brown LM, et al. Occupation, pesticide exposure and risk of multiple myeloma. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2004;30(3):215–222. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Hoppin JA, et al. Pesticide exposure and risk of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in the Agricultural Health Study. Blood. 2009;113(25):6386–6391. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwanaga M, Tagawa M, Tsukasaki K, et al. Relationship between monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and radiation exposure in Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors. Blood. 2009;113(8):1639–1650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landgren O. A role for ionizing radiation in myelomagenesis? Blood. 2009;113(8):1616–1617. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-186957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance: a review. Immunol Rev. 2003;194:112–139. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blade J. Clinical practice. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2765–2770. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grass S, Preuss KD, Ahlgrimm M, et al. Association of a dominantly inherited hyperphosphorylated paraprotein target with sporadic and familial multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: a case–control study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(10):950–956. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70234-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM, Zhan F, Sawyer J, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy J., Jr Cyclin D dysregulation: an early and unifying pathogenic event in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106(1):296–303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergsagel PL, Chesi M, Nardini E, Brents LA, Kirby SL, Kuehl WM. Promiscuous translocations into immunoglobulin heavy chain switch regions in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(24):13931–13936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fonseca R, Bailey RJ, Ahmann GJ, et al. Genomic abnormalities in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2002;100(4):1417–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonseca R, Bergsagel PL, Drach J, et al. International Myeloma Working Group molecular classification of multiple myeloma: spotlight review. Leukemia. 2009;23(12):2210–2221. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avet-Loiseau H, Facon T, Grosbois B, et al. Oncogenesis of multiple myeloma: 14q32 and 13q chromosomal abnormalities are not randomly distributed, but correlate with natural history, immunological features, and clinical presentation. Blood. 2002;99(6):2185–2191. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonseca R, Barlogie B, Bataille R, et al. Genetics and cytogenetics of multiple myeloma: a workshop report. Cancer Res. 2004;64(4):1546–1558. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shou Y, Martelli ML, Gabrea A, et al. Diverse karyotypic abnormalities of the c-myc locus associated with c-myc dysregulation and tumor progression in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(1):228–233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chesi M, Robbiani DF, Sebag M, et al. AID-dependent activation of a MYC transgene induces multiple myeloma in a conditional mouse model of post-germinal center malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bezieau S, Devilder MC, Avet-Loiseau H, et al. High incidence of N and K-Ras activating mutations in multiple myeloma and primary plasma cell leukemia at diagnosis. Hum Mutat. 2001;18(3):212–224. doi: 10.1002/humu.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chng WJ, Gonzalez-Paz N, Price-Troska T, et al. Clinical and biological significance of RAS mutations in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2280–2284. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasmussen T, Kuehl M, Lodahl M, Johnsen HE, Dahl IM. Possible roles for activating RAS mutations in the MGUS to MM transition and in the intramedullary to extramedullary transition in some plasma cell tumors. Blood. 2005;105(1):317–323. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heller G, Schmidt WM, Ziegler B, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional response to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine and trichostatin a in multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(1):44–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pichiorri F, Suh SS, Ladetto M, et al. MicroRNAs regulate critical genes associated with multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(35):12885–12890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806202105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajkumar SV, Mesa RA, Fonseca R, et al. Bone marrow angiogenesis in 400 patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, multiple myeloma, and primary amyloidosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2210–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, Witzig TE, Timm M, et al. Bone marrow angiogenic ability and expression of angiogenic cytokines in myeloma: evidence favoring loss of marrow angiogenesis inhibitory activity with disease progression. Blood. 2004;104(4):1159–1165. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bataille R, Chappard D, Basle MF. Quantifiable excess of bone resorption in monoclonal gammopathy is an early symptom of malignancy: a prospective study of 87 bone biopsies. Blood. 1996;87(11):4762–4769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Politou M, Terpos E, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Role of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κ B ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin and macrophage protein 1-α (MIP-1a) in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) Br J Haematol. 2004;126(5):686–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melton LJ, 3rd, Rajkumar SV, Khosla S, Achenbach SJ, Oberg AL, Kyle RA. Fracture risk in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(1):25–30. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esteve FR, Roodman GD. Pathophysiology of myeloma bone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20(4):613–624. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spisek R, Kukreja A, Chen LC, et al. Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204(4):831–840. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blotta S, Tassone P, Prabhala RH, et al. Identification of novel antigens with induced immune response in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2009;114(15):3276–3284. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-219436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jagannath S. Value of serum free light chain testing for the diagnosis and monitoring of monoclonal gammopathies in hematology. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2007;7(8):518–523. doi: 10.3816/clm.2007.n.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katzmann JA, Clark RJ, Abraham RS, et al. Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free κ and free λ immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains. Clin Chem. 2002;48(9):1437–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradwell A. Serum Free Light Chain Analysis. 5. The Binding Site, Inc; Birmingham, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dispenzieri A, Kyle R, Merlini G, et al. International Myeloma Working Group guidelines for serum-free light chain analysis in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Leukemia. 2009;23(2):215–224. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katzmann JA, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, et al. Elimination of the need for urine studies in the screening algorithm for monoclonal gammopathies by using serum immunofixation and free light chain assays. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(12):1575–1578. doi: 10.4065/81.12.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21–33. doi: 10.4065/78.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rajkumar SV, Kyle R, Plevak M, et al. Prevalence of light-chain monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (LC-MGUS) among Olmsted County, Minnesota residents aged 50 years or greater. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2006;108(11):5060. [Google Scholar]

- 50 ••.Weiss BM, Abadie J, Verma P, Howard RS, Kuehl WM. A monoclonal gammopathy precedes multiple myeloma in most patients. Blood. 2009;113(22):5418–5422. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-195008. One of two seminal reports proving the essential role for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) as a precursor to multiple myeloma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blade J, Rosinol L, Cibeira MT, de Larrea CF. Pathogenesis and progression of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Leukemia. 2008;22(9):1651–1657. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhan F, Barlogie B, Arzoumanian V, et al. Gene-expression signature of benign monoclonal gammopathy evident in multiple myeloma is linked to good prognosis. Blood. 2007;109(4):1692–1700. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pineda-Roman M, Bolejack V, Arzoumanian V, et al. Complete response in myeloma extends survival without, but not with history of prior monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or smouldering disease. Br J Haematol. 2007;136(3):393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar SK, Dingli D, Lacy MQ, et al. Outcome after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in patients with preceding plasma cell disorders. Br J Haematol. 2008;141(2):205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55 ••.Landgren O, Kyle RA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5412–5417. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194241. One of two seminal reports proving the essential role for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) as a precursor to multiple myeloma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kyle RA, Therneau TM, Rajkumar SV, et al. A long-term study of prognosis in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):564–569. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa01133202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rosinol L, Cibeira MT, Montoto S, et al. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: predictors of malignant transformation and recognition of an evolving type characterized by a progressive increase in M protein size. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(4):428–434. doi: 10.4065/82.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering multiple myeloma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21(6):1093–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katzmann JA, Abraham RS, Dispenzieri A, Lust JA, Kyle RA. Diagnostic performance of quantitative κ and λ free light chain assays in clinical practice. Clin Chem. 2005;51(5):878–881. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.046870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60 ••.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA, Therneau TM, et al. Serum free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2005;106(3):812–817. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1038. Reports the Mayo Clinic Risk Stratification Model for progression from MGUS to a MM or a related malignancy, incorporating the use of serum-free light-chain analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, et al. Immunoglobulin free light-chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(2):785–789. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snozek CL, Katzmann JA, Kyle RA, et al. Prognostic value of the serum free light-chain ratio in newly diagnosed myeloma: proposed incorporation into the international staging system. Leukemia. 2008;22(10):1933–1937. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rawstron AC, Orfao A, Beksac M, et al. Report of the European Myeloma Network on multiparametric flow cytometry in multiple myeloma and related disorders. Haematologica. 2008;93(3):431–438. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ocqueteau M, Orfao A, Almeida J, et al. Immunophenotypic characterization of plasma cells from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance patients. Implications for the differential diagnosis between MGUS and multiple myeloma. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(6):1655–1665. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65 ••.Perez-Persona E, Vidriales MB, Mateo G, et al. New criteria to identify risk of progression in monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance and smoldering multiple myeloma based on multiparameter flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow plasma cells. Blood. 2007;110(7):2586–2592. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088443. Describes the aberrant immunophenotype of bone marrow plasma cells as strongly prognostic for progression of patients with MGUS and smoldering MM to MM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111(5):2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, Derolf AR, Bjorkholm M. Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: a population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):1993–1999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68 •.Barlogie B, van Rhee F, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, et al. Seven-year median time to progression with thalidomide for smoldering myeloma: partial response identifies subset requiring earlier salvage therapy for symptomatic disease. Blood. 2008;112(8):3122–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164228. Largest study of a novel agent, thalidomide, to prevent progression from smoldering MM to MM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rajkumar SV, Gertz MA, Lacy MQ, et al. Thalidomide as initial therapy for early-stage myeloma. Leukemia. 2003;17(4):775–779. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Golombick T, Diamond TH, Badmaev V, Manoharan A, Ramakrishna R. The potential role of curcumin in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undefined significance – its effect on paraproteinemia and the urinary N-telopeptide of type I collagen bone turnover marker. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(18):5917–5922. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Zeldenrust SR, et al. Induction of a chronic disease state in patients with smoldering or indolent multiple myeloma by targeting interleukin 1{β}-induced interleukin 6 production and the myeloma proliferative component. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(2):114–122. doi: 10.4065/84.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, et al. Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582–2590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosinol L, Blade J, Esteve J, et al. Smoldering multiple myeloma: natural history and recognition of an evolving type. Br J Haematol. 2003;123(4):631–636. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mateos M, Lopez-Corral L, Hernandez MT, de la Rubia J. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, Phase III trial of lenalidomide–dexamethasone (len/dex) vs therapeutic abstension in smoldering multiple myeloma at high risk of progression to symptomatic MM: results of the first interim analysis. 51st American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting; New Orleans, LA, USA. 5–8 December (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bird J, Behrens J, Westin J, et al. UK Myeloma Forum (UKMF) and Nordic Myeloma Study Group (NMSG), guidelines for the investigation of newly detected M-proteins and the management of monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) Br J Haematol. 2009;147(1):22–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 101.Clinical trials NCT00480363 www.clinicaltrials.gov