Abstract

Protein folding mechanisms are probed experimentally using single-point mutant perturbations. The relative effects on the folding (ϕ-values) and unfolding (1 - ϕ) rates are used to infer the detailed structure of the transition-state ensemble (TSE). Here we analyze kinetic data on > 800 mutations carried out for 24 proteins with simple kinetic behavior. We find two surprising results: (i) all mutant effects are described by the equation:  . Therefore all data are consistent with a single ϕ-value (0.24) with accuracy comparable to experimental precision, suggesting that the structural information in conventional ϕ-values is low. (ii) ϕ-values change with stability, increasing in mean value and spread from native to unfolding conditions, and thus cannot be interpreted without proper normalization. We eliminate stability effects calculating the ϕ-values at the mutant denaturation midpoints; i.e., conditions of zero stability (ϕ0). We then show that the intrinsic variability is ϕ0 = 0.36 ± 0.11, being somewhat larger for β-sheet-rich proteins than for α-helical proteins. Importantly, we discover that ϕ0-values are proportional to how many of the residues surrounding the mutated site are local in sequence. High ϕ0-values correspond to protein surface sites, which have few nonlocal neighbors, whereas core residues with many tertiary interactions produce the lowest ϕ0-values. These results suggest a general mechanism in which the TSE at zero stability is a broad conformational ensemble stabilized by local interactions and without specific tertiary interactions, reconciling ϕ-values with many other empirical observations.

. Therefore all data are consistent with a single ϕ-value (0.24) with accuracy comparable to experimental precision, suggesting that the structural information in conventional ϕ-values is low. (ii) ϕ-values change with stability, increasing in mean value and spread from native to unfolding conditions, and thus cannot be interpreted without proper normalization. We eliminate stability effects calculating the ϕ-values at the mutant denaturation midpoints; i.e., conditions of zero stability (ϕ0). We then show that the intrinsic variability is ϕ0 = 0.36 ± 0.11, being somewhat larger for β-sheet-rich proteins than for α-helical proteins. Importantly, we discover that ϕ0-values are proportional to how many of the residues surrounding the mutated site are local in sequence. High ϕ0-values correspond to protein surface sites, which have few nonlocal neighbors, whereas core residues with many tertiary interactions produce the lowest ϕ0-values. These results suggest a general mechanism in which the TSE at zero stability is a broad conformational ensemble stabilized by local interactions and without specific tertiary interactions, reconciling ϕ-values with many other empirical observations.

Keywords: kinetics, mutations, phi-values, perturbation analysis, free energy relationships

Protein engineering has dominated the experimental study of folding mechanisms for nearly two decades(1–3). In this method, single-point mutations are studied kinetically to determine the relative effects in folding and unfolding rates. The basic approach is based on the common observation that the logarithm of the folding relaxation rate changes with chemical denaturant in a V-shaped fashion (i.e., the chevron plot) (4). For a two-state folding protein the low and high denaturant limbs report on the folding and unfolding rate constants, respectively. Linear chevron limbs are taken to imply that there is a thermodynamically well-defined transition-state ensemble (TSE) with intermediate sensitivity to chemical denaturant (4). Accordingly, the perturbation free energy produced by mutation ( ) partitions between the folding (ϕ) and unfolding limbs (1 - ϕ) depending on how it affects the TSE. High ϕ-values (> 0.7) indicate a TSE as perturbed as the native state, and low ϕ-values (< 0.3) little effects on the TSE. ϕ-values are viewed as probes of the degree of native structure present in the TSE at the residue level (1) with high values defining the folding nucleus (5).

) partitions between the folding (ϕ) and unfolding limbs (1 - ϕ) depending on how it affects the TSE. High ϕ-values (> 0.7) indicate a TSE as perturbed as the native state, and low ϕ-values (< 0.3) little effects on the TSE. ϕ-values are viewed as probes of the degree of native structure present in the TSE at the residue level (1) with high values defining the folding nucleus (5).

The large number of proteins studied experimentally with this approach has turned ϕ-values into critical benchmarks for theory (6), statistical mechanical models (7–9), and computer simulations (10, 11). More recently, experimental ϕ-values are being used as constraints to identify folding transition states in molecular dynamics simulations (12). In parallel, there has been increasing interest in the sources of experimental error and variability (13, 14). A concerted effort has showed that the experimental precision for  across various labs is ∼1.3 kJ/mol (15), which is slightly worse than estimates from fitting errors (∼0.7–1 kJ/mol). The accuracy of individual ϕ-values is thus critically dependent on

across various labs is ∼1.3 kJ/mol (15), which is slightly worse than estimates from fitting errors (∼0.7–1 kJ/mol). The accuracy of individual ϕ-values is thus critically dependent on  (14), which ranges from 2 to 20 kJ/mol in typical experiments. In parallel, the dynamic range in experimental ϕ-values appears to vary for different proteins, which are thus classified as having polarized or diffuse TSE (13). Another important issue is whether ϕ-values are constant or change systematically with protein stability. ϕ-value increases with temperature have been reported in CI2 (16), the Pin WW-domain (17), and the villin headpiece subdomain (9). Monotonic changes in ϕ-values have also been used to explain the curved chevron limbs observed for some proteins (18). However, ϕ-values from chemical denaturation experiments are assumed to be constant when the protein exhibits linear chevron limbs.

(14), which ranges from 2 to 20 kJ/mol in typical experiments. In parallel, the dynamic range in experimental ϕ-values appears to vary for different proteins, which are thus classified as having polarized or diffuse TSE (13). Another important issue is whether ϕ-values are constant or change systematically with protein stability. ϕ-value increases with temperature have been reported in CI2 (16), the Pin WW-domain (17), and the villin headpiece subdomain (9). Monotonic changes in ϕ-values have also been used to explain the curved chevron limbs observed for some proteins (18). However, ϕ-values from chemical denaturation experiments are assumed to be constant when the protein exhibits linear chevron limbs.

To investigate these issues we have compiled all available single-point mutant folding data of proteins exhibiting simple kinetic behavior—that is, single exponential kinetics, no evidence of intermediates, and chevron plots with linear limbs—and for which all kinetic parameters have been reported (806 mutants in 24 single-domain proteins, see Table S1). We then analyze all these mutant rate data using a combination of empirical, statistical, and clustering approaches.

Results

General Trends and Structural Information in ϕ-Values.

We analyze all data together by comparing the changes in activation free energy for unfolding upon mutation ( ) with

) with  (i.e, the Brønsted plot). The advantage of the Brønsted plot is that it provides direct comparison between mutants in a free energy scale in which the horizontal (ϕ = 1) and diagonal (ϕ = 0) lines define the experimental dynamic range as function of

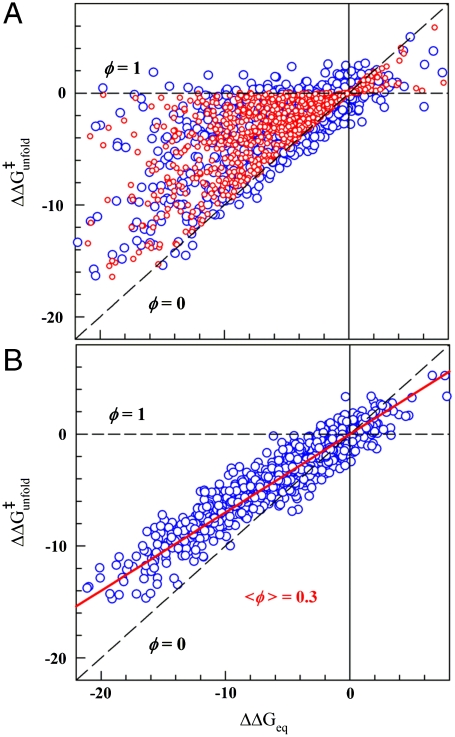

(i.e, the Brønsted plot). The advantage of the Brønsted plot is that it provides direct comparison between mutants in a free energy scale in which the horizontal (ϕ = 1) and diagonal (ϕ = 0) lines define the experimental dynamic range as function of  . As reference frame we consider two extreme scenarios. In the first scenario ϕ-values cover the full 0 to 1 range, corresponding to maximal structural information. In the second scenario all mutants for all proteins have the same ϕ-value. Numerical simulations, with the

. As reference frame we consider two extreme scenarios. In the first scenario ϕ-values cover the full 0 to 1 range, corresponding to maximal structural information. In the second scenario all mutants for all proteins have the same ϕ-value. Numerical simulations, with the  values taken from experiment and the ϕ-values taken either randomly between 0 and 1 (scenario 1) or as a single value of 0.3 (scenario 2), produce the Brønsted plots shown in red in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively. The effects of experimental error are shown in blue for a uniform estimated precision of ± 1.0 kJ/mol. Comparison of Fig. 1 A and B shows that these two scenarios are indistinguishable for

values taken from experiment and the ϕ-values taken either randomly between 0 and 1 (scenario 1) or as a single value of 0.3 (scenario 2), produce the Brønsted plots shown in red in Fig. 1 A and B, respectively. The effects of experimental error are shown in blue for a uniform estimated precision of ± 1.0 kJ/mol. Comparison of Fig. 1 A and B shows that these two scenarios are indistinguishable for  , consistently with the Sanchez and Kiefhaber conclusion (13). However, the overall experimental dynamic range in

, consistently with the Sanchez and Kiefhaber conclusion (13). However, the overall experimental dynamic range in  (∼20 kJ/mol) is large enough to warrant further analysis in terms of changes in free energy.

(∼20 kJ/mol) is large enough to warrant further analysis in terms of changes in free energy.

Fig. 1.

Scenarios for the structural interpretation of ϕ-values. (A) Simulated Brønsted plot for a scenario in which ϕ-values explore all possible values between 0 and 1. Red circles are the simulation without noise. Blue circles are the same plus white noise of ± 1.0 kJ/mol. (B) As A but for a scenario in which all mutations produce a single ϕ-value of 0.3. All relevant units are in kJ/mol.

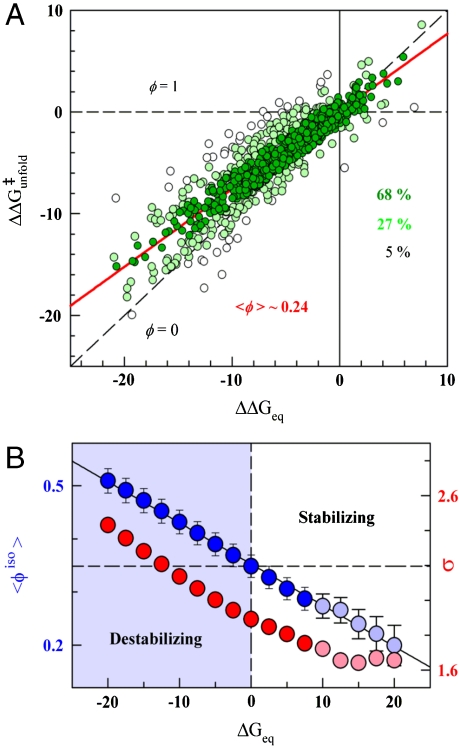

Interestingly, the Brønsted plot for the actual experimental data shows that all mutants cluster around a straight line defined by  (linear correlation coefficient r ∼ 0.9), corresponding to a global ϕ-value of 0.24 (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the experimental data is very close to a single universal ϕ-value with normally distributed error (e.g., scenario 2 as simulated in Fig. 1B), whereas the probability for it arising from scenario 1 is statistically negligible (p < 10-10, see SI Methods). Individual mutations deviate from the correlation line with standard deviation (σ) of ∼1.8 kJ/mol. That is, for 68% of the data (548 mutants, dark green in Fig. 2A) the agreement is better than 1.8 kJ/mol and is thus comparable to the experimental reproducibility in

(linear correlation coefficient r ∼ 0.9), corresponding to a global ϕ-value of 0.24 (Fig. 2A). Therefore, the experimental data is very close to a single universal ϕ-value with normally distributed error (e.g., scenario 2 as simulated in Fig. 1B), whereas the probability for it arising from scenario 1 is statistically negligible (p < 10-10, see SI Methods). Individual mutations deviate from the correlation line with standard deviation (σ) of ∼1.8 kJ/mol. That is, for 68% of the data (548 mutants, dark green in Fig. 2A) the agreement is better than 1.8 kJ/mol and is thus comparable to the experimental reproducibility in  across labs (15). The distribution of the experimental data around a single value is homogeneous as indicated by a nonparametric jackknife test (Fig. S1). Moreover, the general behavior shown in Fig. 2A is also maintained at the protein level and thus each of the 24 datasets clusters around the global ϕ-value line with mean deviations ranging between 1 and 2.5 kJ/mol (Fig. 3).

across labs (15). The distribution of the experimental data around a single value is homogeneous as indicated by a nonparametric jackknife test (Fig. S1). Moreover, the general behavior shown in Fig. 2A is also maintained at the protein level and thus each of the 24 datasets clusters around the global ϕ-value line with mean deviations ranging between 1 and 2.5 kJ/mol (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Empirical observations in ϕ-values. (A) Conventional Brønsted plot for the 806 mutants. The red line is the linear fit that provides the global ϕ-value (1-slope). The data is colored according to line proximity: closest 68% in dark green; next 27% in light green; farthest 5% in white. (B) Global ϕ-value obtained in isostability conditions (Blue Circles and left scale) and fluctuations from the line defining the global ϕ-value (Red Circles and right scale) as a function of protein stability. Lighter color indicates high stability conditions met by less than 90% of the mutants. Error bars correspond to 95% confidence. All relevant units are in kJ/mol.

Fig. 3.

Brønsted plot of the 24 protein datasets. The red line and the scales are identical to Fig. 2A. Dashed lines signal the swath corresponding to 2σ (i.e. 3.9 kJ/mol). The proteins are identified by their pdb code. Open circles correspond to the same 5% most deviating mutations shown in white in Fig. 2A. σ is the standard deviation of the fluctuations of each protein dataset from the global correlation line (ϕ = 0.24). All relevant units are in kJ/mol.

Intrinsic Movement of the Folding TSE.

The previous analysis was performed using the conventional procedure in which mutant data are compared at a fixed concentration of chemical denaturant (often water or very low denaturant concentrations). Therefore, ϕ-values are by definition compared at different stabilities. One straightforward way to test for stability effects is to compare mutant and wild-type rates at the denaturant concentrations at which the mutants attain a given target stability (same  for all mutants but different denaturant concentration). The target stability can then be changed arbitrarily by scanning through the experimental range provided by chemical denaturant. For example, for zero stability conditions (

for all mutants but different denaturant concentration). The target stability can then be changed arbitrarily by scanning through the experimental range provided by chemical denaturant. For example, for zero stability conditions ( )

)  and

and  are calculated at the chemical denaturation midpoints of the mutants. From here onward ϕ-values calculated this way are termed isostability ϕ-values.

are calculated at the chemical denaturation midpoints of the mutants. From here onward ϕ-values calculated this way are termed isostability ϕ-values.

The striking result is that the global isostability ϕ-value obtained from linear regression of the Brønsted plot increases linearly as  decreases (blue in Fig. 2B). The effect is very pronounced, with the global isostability ϕ-value going from 0.2 to 0.5. This trend indicates that there is intrinsic Hammond behavior in chemical denaturation experiments. What is most remarkable is that the monotonic change in global isostability ϕ-value is observed for proteins and mutants that exhibit linear chevron limbs. This increase is accompanied by larger variability in individual isostability ϕ-values: from ∼1.6 kJ/mol in native conditions to ∼2.5 in highly destabilizing conditions (red in Fig. 2B). Fig. 2B indicates that, as the TSE becomes more native-like in terms of stabilization free energy (higher 〈ϕiso〉), the variability observed at the residue level also increases.

decreases (blue in Fig. 2B). The effect is very pronounced, with the global isostability ϕ-value going from 0.2 to 0.5. This trend indicates that there is intrinsic Hammond behavior in chemical denaturation experiments. What is most remarkable is that the monotonic change in global isostability ϕ-value is observed for proteins and mutants that exhibit linear chevron limbs. This increase is accompanied by larger variability in individual isostability ϕ-values: from ∼1.6 kJ/mol in native conditions to ∼2.5 in highly destabilizing conditions (red in Fig. 2B). Fig. 2B indicates that, as the TSE becomes more native-like in terms of stabilization free energy (higher 〈ϕiso〉), the variability observed at the residue level also increases.

The effects shown in Fig. 2B are related to systematic changes in the slopes of the chevron limbs (mf and mu) between mutants and wild-type proteins. Such slope changes are of two kinds: (i) increasingly steeper chevrons (larger mkin = mu - mf) as  increases, and (ii) larger increases in -mf than in mu (larger βT = -mf/mkin). Although experimental errors in chevron slopes are often large, the two trends are clear at the protein level for most cases (Table S2). Increases in βT have been discussed in detail for proteins such as L23 (19) and reflect Hammond TSE displacements. The increases in mkin are nonclassical effects that could be explained with structural changes in one of the two ground states: either disruption of residual structure in the unfolded state induced by mutation (20, 21) or distortions of the native structure proportional to denaturant concentration.

increases, and (ii) larger increases in -mf than in mu (larger βT = -mf/mkin). Although experimental errors in chevron slopes are often large, the two trends are clear at the protein level for most cases (Table S2). Increases in βT have been discussed in detail for proteins such as L23 (19) and reflect Hammond TSE displacements. The increases in mkin are nonclassical effects that could be explained with structural changes in one of the two ground states: either disruption of residual structure in the unfolded state induced by mutation (20, 21) or distortions of the native structure proportional to denaturant concentration.

Eliminating Stability Effects and Estimating the Intrinsic Variability in ϕ-Values.

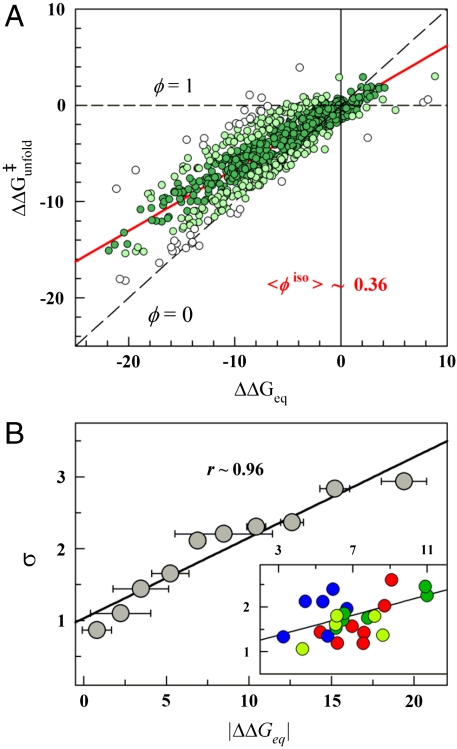

To eliminate stability effects we redefine the ϕ-value to zero stability ( ), where there is no net folding bias. As an additional advantage, at zero stability the folding and unfolding rates are determined with highest precision. The global ϕ-value calculated at zero stability (ϕ0 from hereafter) is ∼0.36, and the scatter from the correlation line in the Brønsted plot is minimally increased to ∼1.9 kJ/mol (Fig. 4A). The global ϕ0-values for the 24 protein datasets (obtained from the Brønsted slopes) are also statistically consistent with a global ϕ0-value of 0.36 (mean ∼0.34 and standard deviation ∼0.08).

), where there is no net folding bias. As an additional advantage, at zero stability the folding and unfolding rates are determined with highest precision. The global ϕ-value calculated at zero stability (ϕ0 from hereafter) is ∼0.36, and the scatter from the correlation line in the Brønsted plot is minimally increased to ∼1.9 kJ/mol (Fig. 4A). The global ϕ0-values for the 24 protein datasets (obtained from the Brønsted slopes) are also statistically consistent with a global ϕ0-value of 0.36 (mean ∼0.34 and standard deviation ∼0.08).

Fig. 4.

Eliminating stability effects in ϕ-values. (A) Brønsted plot obtained at the chemical denaturation midpoint (zero stability) for the 806 mutants. Colors as in Fig. 2A. (B) Correlation between the fluctuations from the line defining the global ϕ-value (standard deviation, σ) and  for the 806 mutations grouped in 10 clusters according to

for the 806 mutations grouped in 10 clusters according to  . (Inset) Superposition of the mean deviation for each of the 24 protein datasets. Proteins have been colored according to structural class: (Blue) all-beta, (Red) α-helical, (Dark Green) α + β with more than 30% β-sheet, (Pale Green) α + β with 30% β-sheet or less. All relevant units are in kJ/mol.

. (Inset) Superposition of the mean deviation for each of the 24 protein datasets. Proteins have been colored according to structural class: (Blue) all-beta, (Red) α-helical, (Dark Green) α + β with more than 30% β-sheet, (Pale Green) α + β with 30% β-sheet or less. All relevant units are in kJ/mol.

Interestingly, the deviations from the global ϕ0 are directly proportional to the perturbation magnitude. This is shown in Fig. 4B using a clustering analysis in which the > 800 mutants have been optimally grouped according to their experimental  values (Methods). The cluster analysis allows extricating the intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values from the experimental error in

values (Methods). The cluster analysis allows extricating the intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values from the experimental error in  . The intercept of the correlation line with the ordinate at ∼1 kJ/mol provides a direct estimate of the overall experimental precision (variability when

. The intercept of the correlation line with the ordinate at ∼1 kJ/mol provides a direct estimate of the overall experimental precision (variability when  ). Furthermore, from the correlation slope of ∼0.11 we estimate that the intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values is 0.36 ± 0.11. This is an important result that indicates that the ϕ0-value fluctuations of Fig. 4A do include some structural-energetic information. To explore trends at the protein level we can plot the mean ϕ0 and

). Furthermore, from the correlation slope of ∼0.11 we estimate that the intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values is 0.36 ± 0.11. This is an important result that indicates that the ϕ0-value fluctuations of Fig. 4A do include some structural-energetic information. To explore trends at the protein level we can plot the mean ϕ0 and  values for the 24 datasets on top of the correlation line (inset to Fig. 4B). This exercise shows that all protein datasets are reasonably close to the global line (within 0.8 kJ/mol), but there is significant scatter that signify that some datasets are more polarized (above the line) or more diffuse (points well below the line). Coloring the points according to the protein structural type hints a pattern in which the intrinsic ϕ0 variability seems to be larger for all-β proteins (blue) than for α-helical proteins (red), with mixed α/β proteins lying in between (dark green for β content > 30% and pale green for β content ≤ 30%). This weak structural pattern agrees with recent theoretical predictions (22).

values for the 24 datasets on top of the correlation line (inset to Fig. 4B). This exercise shows that all protein datasets are reasonably close to the global line (within 0.8 kJ/mol), but there is significant scatter that signify that some datasets are more polarized (above the line) or more diffuse (points well below the line). Coloring the points according to the protein structural type hints a pattern in which the intrinsic ϕ0 variability seems to be larger for all-β proteins (blue) than for α-helical proteins (red), with mixed α/β proteins lying in between (dark green for β content > 30% and pale green for β content ≤ 30%). This weak structural pattern agrees with recent theoretical predictions (22).

Protein Packing and Local Interactions as Primary Determinants of ϕ0-Values.

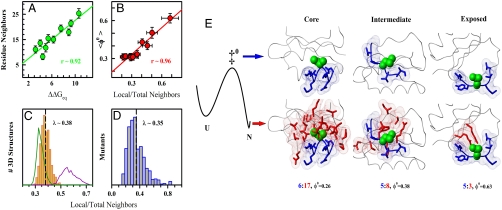

To further investigate the structural information in ϕ0-values we again resort to a clustering approach. The clustering procedure allows to objectively group mutants according to specific properties and to reduce experimental error and undesired heterogeneity through averaging within each cluster. We clustered mutations based on the structural-packing properties of the mutated site as defined by three parameters: the number of residues with atoms within a 0.68 nm radius of the mutated residue (spatial neighbors), the side-chain solvent accessibility (ASA), and the fraction of neighbors within four residues in sequence (local neighbors). These three parameters determine quite precisely whether the mutated site is in the protein core or on the surface as well as the contribution from local contacts (i.e., secondary structure).

A first observation is that mutant perturbations are proportional to the packing density around the mutated site. This is shown as a strong correlation between  and the number of spatial neighbors (Fig. 5A). Similar results are obtained with different numbers of clusters, other distance cut-offs (0.5–0.7 nm), counting atoms, and including or neglecting the backbone. This result is in fact a generalization of previously reported correlations for side-chain deletions (23). In other words, the closer the mutated site is to the protein core, the larger the resulting perturbation. The implication is that there is a strong connection between packing environment and stabilization energetics. The proportionality shown in Fig. 5A also suggests that mutant perturbations propagate to all surrounding chemical groups, even beyond the first coordination shell.

and the number of spatial neighbors (Fig. 5A). Similar results are obtained with different numbers of clusters, other distance cut-offs (0.5–0.7 nm), counting atoms, and including or neglecting the backbone. This result is in fact a generalization of previously reported correlations for side-chain deletions (23). In other words, the closer the mutated site is to the protein core, the larger the resulting perturbation. The implication is that there is a strong connection between packing environment and stabilization energetics. The proportionality shown in Fig. 5A also suggests that mutant perturbations propagate to all surrounding chemical groups, even beyond the first coordination shell.

Fig. 5.

Packing and local interactions as primary determinants of ϕ-values. (A) Mutant perturbation free energies versus the number of residues surrounding the mutated site. Error bars are one standard deviation.  variability ranges from 2 to 5 kJ/mol per cluster. (B) ϕ0-values versus the fraction of local neighbors. Vertical error bars are 68% confidence from linear fits to the Brønsted plot of each cluster. Horizontal error bars correspond to one standard deviation. (C) Mean fraction of local neighbors in the residue packing environments of globular protein structures (Yellow). Green shows only buried (61%) and magenta only solvent-exposed (39%) residues. (D) As C for the 806 individual mutated sites. (E) Depiction of the folding TSE at zero stability with buried backbone and local interactions made (Blue). Long-range interactions (Red) form after crossing the barrier. This translates into lower or higher ϕ0-values depending on the fraction of local residues surrounding the mutated site (shown in Green).

variability ranges from 2 to 5 kJ/mol per cluster. (B) ϕ0-values versus the fraction of local neighbors. Vertical error bars are 68% confidence from linear fits to the Brønsted plot of each cluster. Horizontal error bars correspond to one standard deviation. (C) Mean fraction of local neighbors in the residue packing environments of globular protein structures (Yellow). Green shows only buried (61%) and magenta only solvent-exposed (39%) residues. (D) As C for the 806 individual mutated sites. (E) Depiction of the folding TSE at zero stability with buried backbone and local interactions made (Blue). Long-range interactions (Red) form after crossing the barrier. This translates into lower or higher ϕ0-values depending on the fraction of local residues surrounding the mutated site (shown in Green).

A second observation is that ϕ0-values are proportional to the fraction of local residue neighbors, as demonstrated by a strong linear correlation (r ∼ 0.96 with slope ∼1 and ∼zero intercept) (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the global ϕ0-value seems to reflect the average contribution from local neighbors to the packing of globular proteins, which is indeed very uniform, mostly independent of protein topology, and similar in magnitude to the global ϕ0-value (Fig. 5C). By the same token, the variability in ϕ0-values is related to the packing heterogeneity at the single site level, which depends mostly on the location on the protein structure. For core residues, the fraction of local neighbors is low (green in Fig. 5C) because these residues are surrounded by many nonlocal neighbors, whereas surface residues have high local fractions owing to the fewer nonlocal neighbors (magenta in Fig. 5C). These differences are evident in the > 800 mutated sites, which exhibit a quite broad distribution of local fractions with mean at 0.35 (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5 A–D indicate that the higher ϕ0-values correspond to mutations in sites surrounded by few packing neighbors and that produce very small perturbations. The influence of these mutants on the overall behavior is thus small in terms of total free energy: The two clusters with highest ϕ0-values in Fig. 5B produce an average perturbation of ∼3.1 kJ/mol. Nevertheless, the correlation between ϕ0-value and the fraction of local neighbors is very strong, independent of the numbers of clusters employed (Fig. S2), and further corroborated by the Brønsted plot at zero stability for the 153 mutations on exposed sites (> 50% ASA), which produces a slope of ∼0.56. The importance of Fig. 5 A and B is that they directly connect the intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values with the contribution of local interactions to the structural-energetic environment of the mutated site. Protein core residues have dense packing environments with many neighbors, result in large perturbations, and exhibit low ϕ0-values because local interactions contribute little to their energetic environment (Fig. 5E). Residues on the surface are surrounded by few mostly local neighbors and, accordingly, produce much smaller perturbations with higher ϕ0-values (Fig. 5E). Based on this premise, the global ϕ0-value reflects the overall contribution from local interactions to protein stability, which to a first order approximation is proportional to the fraction of local neighbors in globular proteins structures.

Looking Beyond General Packing Effects.

In principle, folding topology, aminoacid sequence, and mutation palette should further modulate the energetic-structural contribution from local interactions. In this regard, it is interesting to take a closer look at the 5% largest outliers in Fig. 4A. The first realization is that many of these mutations are in sites with unusual packing properties or with local fractions well away from 0.36 (Table S3). Simply using the local neighbor fraction as direct estimate of the ϕ0-value reduces the deviations by 0.7 kJ/mol on average. The remaining variability is still large (∼4 kJ/mol), and hence it is tempting to assign it to detailed energetic changes in the TSE. However, the vast majority of these mutations involve very large changes in chevron slopes (i.e., > 20%), which suggest significant changes in ground states (20, 21) and make these mutations inappropriate for a standard ϕ-value analysis (24).

A more powerful strategy is to look for systematic trends in multiple mutations at single sites. As a first step, comparing the 55 sites with mutations to both Ala and Gly shows that for most sites, and regardless of solvent accessibility and secondary structure, Ala and Gly produce the same result within the ∼1.4 kJ/mol combined experimental precision (Fig. S3). This result confirms that packing properties are a stronger determinant of ϕ0-values than any mutation-dependent energetic effect. Unfortunately, very little systematic information is available on multiple mutations. The most comprehensive analysis comes from the Davidson group, which has produced extensive mutant collections in single sites of SH3 domains (ref. 25 and references therein). Interestingly, these mutant collections produce linear Brønsted plots with disparate slopes, indicating highly heterogeneous ϕ-values (Table 1). Out of these, the mostly buried E24 exhibits an average local fraction that agrees well with the ϕ0-value. S41 is a clear case of noncanonical TSE effects because all mutations slow down both the folding and unfolding rates, and as such it is beyond the scope of this analysis. The other three sites are located on the exposed face of β-sheets and produce high ϕ0-values. For T22 ϕ0-value and fraction of local neighbors agree well. The other two (R40 and T47) are more intriguing. Their side chains are exposed and the ϕ0-values are high (0.6–0.7), but the fraction of local neighbors is average (Table 1). However, Davidson and coworkers found a strong correlation with the intrinsic β-sheet propensity of the substituting aminoacid (25). Their results nicely confirm that high ϕ0-values do correspond to sites that are mostly stabilized by local interactions and suggest that the apparently larger intrinsic ϕ0 variability in β-sheet proteins (blue in inset to Fig. 4B) may be due to a more heterogeneous distribution of local and nonlocal stabilization throughout these structures, in agreement with recent theoretical analysis (22).

Table 1.

Multiple mutations in single sites

| Site |  |

〈ϕ〉 | 〈ϕ0〉 | Local/Total | ASA |

| T22* | 3.66 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 54% |

| E24† | 6.88 | 0.32 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 12% |

| R40† | 4.94 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 0.28 | 51% |

| S41† | 5.62 | 0.08 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 1% |

| T47† | 3.69 | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 49% |

*drkN SH3

†fyn SH3

Discussion

Correcting for Intrinsic Stability Effects in ϕ-Values.

Our global analysis indicates that the ϕ-values from chemical denaturation experiments are not constant parameters but linear functions of protein stability ( ). Therefore, chemical denaturation induces intrinsic TSE movements, similarly to temperature (9, 16, 17) and to the predictions from simple statistical mechanical models (26, 27). It is important to recapitulate that these results have been obtained on proteins with linear chevron limbs. It follows that linear chevrons are not an indication of a structurally well-defined transition state. Nor do they provide on their own sufficient justification for the applicability of the conventional ϕ-value analysis. What emerges from these considerations is that ϕ-values need to be corrected for the changes in stability induced by mutation before they can be interpreted in structural or mechanistic terms. This is relevant for experimentalists and theorists and most significantly when experimental ϕ-values are to be used as constraints in molecular simulations. Here we propose to calculate ϕ-values at the mutant chemical denaturation midpoint (ϕ0), which provides a standard thermodynamic reference and improvements in experimental precision.

). Therefore, chemical denaturation induces intrinsic TSE movements, similarly to temperature (9, 16, 17) and to the predictions from simple statistical mechanical models (26, 27). It is important to recapitulate that these results have been obtained on proteins with linear chevron limbs. It follows that linear chevrons are not an indication of a structurally well-defined transition state. Nor do they provide on their own sufficient justification for the applicability of the conventional ϕ-value analysis. What emerges from these considerations is that ϕ-values need to be corrected for the changes in stability induced by mutation before they can be interpreted in structural or mechanistic terms. This is relevant for experimentalists and theorists and most significantly when experimental ϕ-values are to be used as constraints in molecular simulations. Here we propose to calculate ϕ-values at the mutant chemical denaturation midpoint (ϕ0), which provides a standard thermodynamic reference and improvements in experimental precision.

Physical Basis for a Universal ϕ-Value with Limited Site-to-Site Variability.

Once we eliminate effects from protein stability and experimental error we find that all mutant data are described with the expression ϕ0 = 0.36 ± 0.11. This result raises two important questions: (i) What are the physics behind a global ϕ-value that changes with stability? (ii) Why is the intrinsic variability in individual ϕ-values low?

Regarding the first question, a universal ϕ-value would suggest that proteins commit to folding (reach the TSE) by realizing a given amount of stabilization free energy. As the net free energy stabilizing the native state decreases (e.g., by adding chemical denaturant) the fraction required to reach the TSE grows. These observations coincide with theoretical predictions from energy landscape approaches, which view folding barriers as entropic bottlenecks caused by the imperfect compensation from stabilization free energy during the early folding stages (28). Along these lines the TSE simply corresponds to the folding stage with the largest imbalance, which obviously depends on how much free energy is to be gained upon complete folding. The agreement is in fact quantitative. The capillarity approximation of energy landscape theory predicts that the TSE occurs at 8/27 or 0.29 (29). Simple 1D free energy surface models, which have been successfully used to analyze fast-folding kinetics (30), closely reproduce the global ϕ-value as function of stabilization energy shown in Fig. 2B (31). It is also remarkable that the global ϕ-value in native conditions (ϕiso ∼ 0.25) agrees almost exactly with independent empirical estimates of the fraction of net stabilization free energy realized at the TSE for six two-state-like proteins (i.e., 0.27 ± 0.05) (32).

The limited intrinsic variability in ϕ0 (± 0.11) implies that values close to 1 are statistically extremely rare and, according to Fig. 5, connected to small free energy perturbations and large experimental uncertainty. Furthermore, ϕ0-values seem to be largely independent of the mutation palette. These apparently surprising results seem to arise from two combined factors. First, the perturbations produced by single-point mutations propagate to all surrounding chemical groups and thus are not very sensitive to fine structural details. Second, the TSE at zero stability has realized only one third of the native stabilization free energy (or at least of the free energy affected by mutation), of which local interactions seem to play the major role (Fig. 5B). Such unfolded-like energetics suggests by extension a TSE with high conformational entropy (e.g., see ref. 32) and little structure beyond backbone conformation. Further support for this argument is found in the fact that ϕ-value variability increases together with the global ϕ-value in denaturing conditions (Fig. 2B). As an interesting side effect, this suggests that a simple strategy to maximize the structural information provided by mutational analysis is to determine the ϕ-values in highly denaturing conditions, where the TSE is energetically most native-like.

Implications for the Mechanisms of Folding.

The intrinsic variability in ϕ0-values is clearly connected to general structural properties of the TSE. The correlation between ϕ0 and the fraction of local site-neighbors (Fig. 5B) suggests that individual ϕ0-values reflect the contribution from local interactions to the stabilization free energy of the mutated site and, on average, of the whole protein. This finding explains why, despite all the above, theoretical predictions based on protein 3D structures reproduce some of the experimental patterns in ϕ-values (7, 8, 10, 33). The connection between ϕ0-values and the stabilization from local interactions also has important mechanistic ramifications.

Fractional ϕ-values are typically explained with two alternative TSE scenarios: (i) a single expanded structure with most interactions weakened except the folding nucleus (5); or (ii) a partly folded conformational ensemble in which interactions are present with fractional probabilities (34). Distinguishing between them is difficult because the fundamental differences are only apparent in single-molecule trajectories. However, scenario 1 does imply a specific group of high ϕ-values located within the protein core and that conform the folding nucleus (5). This prediction is inconsistent with our finding that the high ϕ0-values are associated to sites on the protein surface with high local contents. We can thus conclude that the global analysis of mutational data favors scenario 2.

Indeed, the picture for the TSE at zero stability that emerges from our results is that of a broad conformational ensemble stabilized by local interactions and without net consolidation of long-range interactions (Fig. 5E). At more denaturing conditions the TSE becomes energetically more native-like and presumably starts to incorporate long-range tertiary interactions, as suggested by the increase in ϕ-value variability observed experimentally (Fig. 2B). However, one should expect that the TSE movement merely reflects changes in the energetic balance, whereas the sequence of structural events (and thus the mechanism) remains constant. This would imply that local backbone-packing forces control the early folding stages, whereas formation of long-range interactions takes place late in the process. This general description is very similar to the local-first mechanism implicit in hierarchical folding models such as the hydrophobic zipper (35) and in Ising-like statistical mechanical models (26). These results are also reproduced by energy landscape approaches that explicitly distinguish between short- and long-range interactions (36). On the other hand, early lattice simulations suggested an important kinetic role for a small set of long-range contacts (37). In structural terms, the folding TSE at zero stability resembles the classical Molten Globule (38), leaving open the question of how much water is still present in the protein interior. It is also noteworthy that this general picture closely coincides with the structural events drawn from the atom-by-atom analysis of the small protein BBL (39).

Methods

Structural Analysis.

The analysis was performed on 1,014 globular proteins that were obtained by filtering the 1,520 single-domain proteins between 35 and 150 residues with less than 30% sequence identity available in the PDB according to a radius of gyration criterion ( ).

).

Cluster Analysis.

Optimized clusters were produced algorithmically minimizing the target properties between possible elements of each cluster using 10,000 rounds of the K-means algorithm from Matlab. The target properties were either ΔΔGeq (Fig. 4B) or the residue packing environments (Fig. 5 A and B), which were defined according to three Z-scored properties: number of residues with atoms within 0.68 nm, fraction of local neighbors, and relative accessible surface area. Tests with different number of clusters were carried out to find the optimal grouping according to the data distribution (SI Text).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1000988107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fersht AR, Matouschek A, Serrano L. The folding of an enzyme 1. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J Mol Biol. 1992;224(3):771–782. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90561-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daggett V, Fersht A. The present view of the mechanism of protein folding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(6):497–502. doi: 10.1038/nrm1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliveberg M, Wolynes PG. The experimental survey of protein-folding energy landscapes. Q Rev Biophys. 2005;38(3):245–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033583506004185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aune KC, Tanford C. Thermodynamics of denaturation of lysozyme by guanidine hydrochloride 2. Dependence on denaturant concentration at 25 degrees. Biochemistry. 1969;8(11):4586–4590. doi: 10.1021/bi00839a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itzhaki LS, Otzen DE, Fersht AR. The structure of the transition-state for folding of chymotrypsin inhibitor-2 analyzed by protein engineering methods—Evidence for a nucleation-condensation mechanism for protein-folding. J Mol Biol. 1995;254(2):260–288. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portman JJ, Takada S, Wolynes PG. Variational theory for site resolved protein folding free energy surfaces. Phys Rev Lett. 1998;81(23):5237–5240. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alm E, Baker D. Prediction of protein-folding mechanisms from free-energy landscapes derived from native structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(20):11305–11310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garbuzynskiy SO, Finkelstein AV, Galzitskaya OV. Outlining folding nuclei in globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2004;336(2):509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubelka J, Henry ER, Cellmer T, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Chemical, physical, and theoretical kinetics of an ultrafast folding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18655–18662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808600105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: What determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and “en-route” intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fersht AR, Daggett V. Protein folding and unfolding at atomic resolution. Cell. 2002;108(4):573–582. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vendruscolo M, Paci E, Dobson CM, Karplus M. Three key residues form a critical contact network in a protein folding transition state. Nature. 2001;409(6820):641–645. doi: 10.1038/35054591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanchez IE, Kiefhaber T. Origin of unusual Phi-values in protein folding: Evidence against specific nucleation sites. J Mol Biol. 2003;334(5):1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raleigh DP, Plaxco KW. The protein folding transition state: what are phi-values really telling us? Protein Peptide Lett. 2005;12(2):117–122. doi: 10.2174/0929866053005809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Los Rios MA, et al. On the precision of experimentally determined protein folding rates and phi-values. Protein Sci. 2006;15(3):553–563. doi: 10.1110/ps.051870506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveberg M, Tan YJ, Silow M, Fersht AR. The changing nature of the protein folding transition state: Implications for the shape of the free-energy profile for folding. J Mol Biol. 1998;277(4):933–943. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jager M, Nguyen H, Crane JC, Kelly JW, Gruebele M. The folding mechanism of a beta-sheet: The WW domain. J Mol Biol. 2001;311(2):373–393. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ternstrom T, Mayor U, Akke M, Oliveberg M. From snapshot to movie: Phi analysis of protein folding transition states taken one step further. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):14854–14859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedberg L, Oliveberg M. Scattered Hammond plots reveal second level of site-specific information in protein folding: phi′ (beta(double dagger)) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(20):7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308497101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez IE, Kiefhaber T. Hammond behavior versus ground state effects in protein folding: Evidence for narrow free energy barriers and residual structure in unfolded states. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:867–884. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho JH, Raleigh DP. Denatured state effects and the origin of nonclassical phi values in protein folding. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(51):16492–16493. doi: 10.1021/ja0669878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho SS, Levy Y, Wolynes PG. Quantitative criteria for native energetic heterogeneity influences in the prediction of protein folding kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:434–439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810218105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Main ERG, Fulton KF, Jackson SE. Context-dependent nature of destabilizing mutations on the stability of FKBP12. Biochemistry. 1998;37(17):6145–6153. doi: 10.1021/bi973111s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fersht AR, Sato S. Phi-value analysis and the nature of protein-folding transition states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(21):7976–7981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402684101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zarrine-Afsar A, Dahesh S, Davidson AR. Protein folding kinetics provides a context-independent assessment of beta-strand propensity in the fyn SH3 domain. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:764–774. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muñoz V, Eaton WA. A simple model for calculating the kinetics of protein folding from three-dimensional structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(20):11311–11316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cellmer T, Henry ER, Kubelka J, Hofrichter J, Eaton WA. Relaxation rate for an ultrafast folding protein is independent of chemical denaturant concentration. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14564–14565. doi: 10.1021/ja0761939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onuchic JN, LutheySchulten Z, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding: The energy landscape perspective. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1997;48:545–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.48.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolynes PG. Folding funnels and energy landscapes of larger proteins within the capillarity approximation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6170–6175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naganathan AN, Doshi U, Muñoz V. Protein folding kinetics: Barrier effects in chemical and thermal denaturation experiments. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(17):5673–5682. doi: 10.1021/ja0689740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muñoz V, Sadqi M, Naganathan AN, de Sancho D. Exploiting the downhill folding regime via experiment. HFSP J. 2008;2(6):342–353. doi: 10.2976/1.2988030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akmal A, Muñoz V. The nature of the free energy barriers to two-state folding. Proteins. 2004;57(1):142–152. doi: 10.1002/prot.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zong C, Wilson CJ, Shen T, Wolynes PG, Wittung-Stafshede P. Phi-value analysis of apo-azurin folding: Comparison between experiment and theory. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6458–6466. doi: 10.1021/bi060025w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shoemaker BA, Wang J, Wolynes PG. Exploring structures in protein folding funnels with free energy functionals: The transition state ensemble. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:675–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weikl TR, Dill KA. Folding rates and low-entropy-loss routes of two-state proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:585–598. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plotkin SS, Onuchic JN. Investigation of routes and funnels in protein folding by free energy functional methods. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(12):6509–6514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abkevich VI, Gutin AM, Shakhnovich EI. Specific nucleus as the transition-state for protein-folding—Evidence from the lattice model. Biochemistry. 1994;33(33):10026–10036. doi: 10.1021/bi00199a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ptitsyn OB. Molten globule and protein folding. Adv Protein Chem. 1995;47:83–229. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sadqi M, Fushman D, Muñoz V. Atom-by-atom analysis of global downhill protein folding. Nature. 2006;442(7100):317–321. doi: 10.1038/nature04859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.