Abstract

To overcome burden of mosquito-borne diseases, multiple control strategies are needed. Population replacement with genetically modified mosquitoes carrying antipathogen effector genes is one of the possible approaches for controlling disease transmission. However, transgenic mosquitoes with antipathogen phenotypes based on overexpression of a single type effector molecule are not efficient in interrupting pathogen transmission. Here, we show that co-overexpression of two antimicrobial peptides (AMP), Cecropin A, and Defensin A, in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes results in the cooperative antibacterial and antiPlasmodium action of these AMPs. The transgenic hybrid mosquitoes that overexpressed both Cecropin A and Defensin A under the control of the vitellogenin promoter exhibited an elevated resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, indicating that these AMPs acted cooperatively against this pathogenic bacterium. In these mosquitoes infected with P. gallinaceum, the number of oocysts was dramatically reduced in midguts, and no sporozoites were found in their salivary glands when the mosquitoes were fed twice to reactivate transgenic AMP production. Infection experiments using the transgenic hybrid mosquitoes, followed by sequential feeding on naive chicken, and then naive wild-type mosquitoes showed that the Plasmodium transmission was completely blocked. This study suggests an approach in generating transgenic mosquitoes with antiPlasmodium refractory phenotype, which is coexpression of two or more effector molecules with cooperative action on the parasite.

Keywords: vector-borne disease, malaria, immunity, antimicrobial peptide, vitellogenin

Mosquito-borne diseases are among the major concerns of public health. Malaria is a particularly threatening disease that is responsible for over one million deaths per year. Dengue fever affects hundreds of millions of people. Other viral and filarial diseases transmitted by mosquitoes are prevalent in many areas of the world (1, 2). Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore every avenue for developing unique control strategies against mosquito-borne diseases.

Population replacement with genetically modified mosquitoes carrying an antipathogen effector gene has been suggested as one of strategies for disrupting mosquito-borne disease transmission (3, 4). Development of genetic transformation has been accomplished for Aedes aegypti, the vector of Dengue fever, Anopheles stephensi, the vector of Asian malaria, and recently for the vector of most deadly form of malaria in Africa, Anopheles gambiae (5–8). Genetic modification of mosquitoes by means of transposable elements provides an outstanding tool for experimental testing of concepts of vector biology, including pathogen-vector interactions. Utilization of transgenesis to generate mosquitoes with altered immunity has been instrumental in deciphering major immune pathways and their role in antipathogen defense (7, 9–11). Transgenic mosquitoes with antipathogen refractory phenotypes have been developed by utilizing blood meal-activated, tissue-specific promoters, and effector molecules or RNAi-constructs (11–15). However, complete interruption of pathogen transmission in these transgenic models has not been achieved. In the case of malaria parasite, only a few sporozoites present in mosquito salivary glands were sufficient to infect a vertebrate host (15). These transgenic mosquitoes with antipathogen refractory phenotypes have been based on expression of a single type effector molecule in a single organ or tissue. Overexpression of two or more effector molecules with additive antipathogen action in the same transgenic mosquito strain could dramatically increase effectiveness of antipathogen-vector phenotypes. To provide a proof for this hypothesis, we have tested whether co-overexpression of two effector molecules in the transgenic Ae. aegypti could block transmission of Plasmodium gallinaceum.

Studies in Drosophila melanogaster have provided the basis of our knowledge about the insect innate immune response (16). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are an important part of the humoral immunity. In D. melanogaster, there are seven distinct AMP families, which differ widely in their specificities against microorganisms (16). Mosquito AMPs significantly differ from Drosophila and are mainly represented by defensins and cecropins (17). Mosquito defensins are primarily active against Gram-positive bacteria, although a Gram-negative bacterium, Enterobacter cloacae, is susceptible to Aedes Defensin A (DefA) (18). Mosquito cecropins have a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity (19, 20). In vivo, AMPs, and other components of the immune system could work cooperatively against invading pathogens. To test this hypothesis, we have chosen DefA and Cecropin A (CecA) for ectopic overexpression in transgenic mosquitoes, because they are representatives of two major classes of mosquito AMPs (17). Both these AMPs were expressed highly after immune challenge or ectopic expression of REL2, the mosquito orthologue of Drosophila Relish, in Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (11).

Here, we report the generation of two transgenic Vg-CecA strains of Ae. aegypti with blood meal-activated overexpression of Aedes CecA. Obtaining these new strains has permitted us to test whether the two major mosquito AMPs, CecA and DefA, could have cooperative antimicrobial and antiPlasmodium action. The hybrid Vg-CecA/Vg-DefA mosquitoes (CxD), which expressed both CecA and Def A, exhibited an elevated resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, indicating that these AMPs acted cooperatively against this highly pathogenic bacterium. Significantly, we show that coproduction of these AMPs in the hybrid mosquito completely blocked the proliferation cycle of Plasmodium parasites and interrupted their transmission to a vertebrate host. Thus, this work has provided proof of principal of the transgenic approach for effective interruption of the parasite transmission cycle by means of coexpression of antiparasite effector molecules with additive action.

Results

We first generated transgenic Ae. aegypti strains overexpressing CecA. The Vg-CecA construct, obtained by linking the 1.8 kb Vg gene 5′ regulatory region, CecA cDNA, and SV40 polyadenylation signal, was inserted into the pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm] vector (Fig. S1A). Two independent transgenic strains (C2 and C32) were selected for and established as homozygous for the Vg-CecA transgene. Southern blot and PCR analyses confirmed stable integration of the transgene into the mosquito genome for C2 and C32 strains. These analyses indicate that in each strain the transposition occurred as a single copy insertion in different genomic sites (Fig. S1 and Table S1).

In C2 and C32 strains, the Vg-CecA transgene was under the control of the Vg gene regulatory region, which is activated by a blood meal in a strict sex-, stage-, and tissue-specific manner (21). The Vg-CecA transcript was detected only in females of both C2 and C32 strains after blood feeding and expressed in the fat body with a peak at 24 h post blood meal (PBM) similar to that of the endogenous Vg gene (Fig. S2). Immunoblot analysis showed that there was a high level of CecA peptide 24 h PBM but not at previtellogenic fat bodies, thus confirming stage-specific production of CecA peptide in transgenic mosquitoes (Fig. S2F). Both C2 and C32 Vg-CecA mosquitoes exhibited higher level of resistance than the wild-type (wt) mosquitoes to Gram-negative bacterium, E. cloacae, and two Gram-positive bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, which demonstrated functionality of overexpressed CecA peptide (Fig. S3).

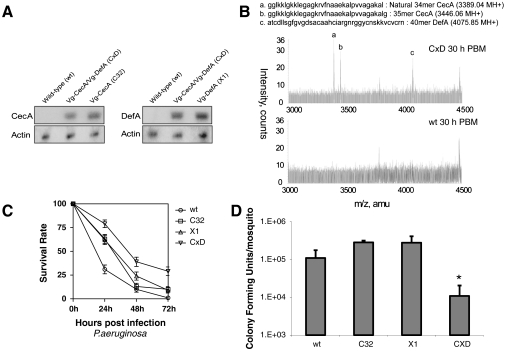

To examine whether CecA and DefA could act cooperatively on pathogens in vivo, we produced hybrid transgenic mosquitoes by crossing the Vg-CecA C32 with the Vg-DefA X1 transgenic strain that produces high levels of Def A in response to a blood meal (7, 22). To generate Vg-CecA/Vg-DefA (CxD) hybrid mosquitoes, the two homozygous strains, Vg-CecA (C32) and Vg-Def A (X1), were maintained as homozygous for four generations before crossing. The hybrid strain was established by crossing C32 females (Vg-CecA) to X1 males (Vg-DefA), and F1 hybrid females were used for experiments. Northern blot analysis indicated that both Vg-CecA and Vg-DefA transgenes were expressed in the CxD mosquitoes (Fig. 1A). To confirm that CecA and DefA peptides were correctly processed in the hybrid mosquitoes, we used mass spectrometry to analyze the components present in their hemolymph 30 h PBM. The mass spectrum from 3,000–4,500 m/z was used to compare the peptide composition of the hemolymph of CxD transgenic and wt mosquitoes (Fig. 1B). Three additional peaks were observed in the hemolymph of CxD mosquitoes that were absent in samples from wt mosquitoes. The mass value of the large 4 kDa peak was only slightly smaller than that calculated for the 40-mer DefA peptide, possibly due to an existing disulfide bond modification in the in vivo peptide (Fig. 1B). The occurrence of two 34-mer and 35-mer peptides is likely related to unprocessed and processed forms of CecA. In Hyalophora cecropia, a modification of C-terminus of recombinant cecropin was necessary to restore broad-spectrum of antimicrobial activity, which was shown in a naturally occurring peptide (23). The naturally occurring CecA in the mosquito Ae. aegypti was reported to be a 34-mer after removal of C-terminus amino acids (19).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the Aedes aegypti hybrid transgenic strain expressing both CecA and DefA. (A) Northern blot analysis of the Vg-CecA C32, Vg-DefA X1, and Vg-CecA/Vg-DefA CxD hybrid mosquitoes. The transgenic and control wild-type (wt) mosquitoes were analyzed 24 h PBM. Total RNA was hybridized with CecA, DefA, or actin cDNA probes wt parental strain. (B) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis of the hemolymph of the hybrid CxD (Upper Panel) and parental wt (Lower Panel) mosquitoes. Peptide sequences below MALDI-TOF image represented processed mature 34-mer and 35-mer Cec A and 40-mer DefA peptides. (C) Survival rate of transgenic and control wt mosquitoes after infection with P. aeruginosa. Means and standard deviations of results reflect data from two independent experiments. P value between the CxD hybrid with other groups was < 0.001. (D) Bacterial proliferation test for P. aeruginosa in adult transgenic and wt mosquitoes. Three mosquitoes per sample were collected and used for colony forming unit determination. Analysis of wt, the transgenic C32, X1, and CxD hybrid female mosquitoes was preformed. Means and standard deviations of results reflect data from two independent experiments. Asterisk (*) represents P < 0.05 (t test), while CxD was compared to other groups.

Pathogenic Gram-negative bacterium P. aeruginosa exhibits a broad host range. This bacterium causes 100% lethality in D. melanogaster (24). It is pathogenic to wt Ae. aegypti mosquitoes (11). To test whether CecA and DefA acted cooperatively against this bacterium, mosquitoes, wt and transgenic, were blood fed and at 24 h PBM were injected with overnight culture of P. aeruginosa diluted 10 times with LB medium (final concentration was 0.2 O.D./mL). The mortality of the challenged mosquitoes was assayed at different time points postinfection (Fig. 1C). Transgenic mosquitoes overexpressing either CecA (Vg-CecA C32 strain) or DefA (Vg-DefA X1 strain) exhibited only a slightly increased rate of survival compared with that of the wt mosquitoes. However, the CxD mosquitoes clearly exhibited an increased survival rate after the challenge by P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that CecA and DefA acted cooperatively against this bacterium. The cooperative activity of these two AMPs was further supported by the observation that reduced susceptibility of the CxD mosquitoes correlated with the limitation of P. aeruginosa proliferation in these mosquitoes (Fig. 1D). The bacterial loads between 5.0 and 5.5 logs were equally maintained in the wt, C32, and X1 mosquitoes by 5 h postinoculation time. However, P. aeruginosa counts were reduced more than 10-fold in the CxD mosquitoes by the same 5 h postinoculation (Fig. 1D). In Drosophila, both the Toll and immunodeficiency pathways are required for providing a maximal resistance to P. aeruginosa, which in turn escapes host defenses by suppressing AMP gene expression (24, 25). In the transgenic mosquito strains, CecA and DefA are produced via blood meal-activated gene cascade, independent of an immune response. Thus, their production is unaffected by P. aeruginosa infection. In the CxD mosquitoes, these AMP peptides acted cooperatively against P. aeruginosa before the development of bacterial virulence, partially protecting these mosquitoes.

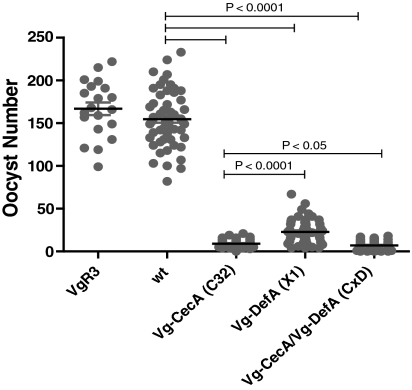

To evaluate whether CecA and DefA had antiPlasmodium activity, two types of experiments were conducted. First, to investigate the effect of transgenic CecA and DefA expression on Plasmodium development, transgenic Vg-CecA, Vg-DefA, and CxD mosquitoes, as well as control mosquitoes, were blood fed on the same P. gallinaceum-infected chick (Fig. 3 and EXP1, EXP2 in Table 1). Two types of control mosquitoes were used: (i) the wt Rockefeller/UGAL strain, and (ii) a nonrelated transgenic VgR3 strain established on wt genetic background and carrying the piggyBac transposon with the 3xP-EGFP marker, similar to that in the experimental transgenic strains. However, the latter had the ovary-specific vitellogenin receptor gene promoter (VgR) (26). The VgR3 strain was used to ascertain whether the incorporation of the pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm] transposon itself did not affect Plasmodium development (Fig. 2, Table 1). The number of oocysts per gut was determined 7–8 d postinfectious blood meal (PIBM). Mosquitoes from control groups showed similar numbers of oocysts indicating that neither the presence of an unrelated transgene in the mosquito genome nor enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) expression as a marker had any effect on malaria parasite oocyst development (Fig. 2, Table 1). In contrast, there was a marked decrease in the number of oocysts in midguts of transgenic mosquitoes expressing CecA (C32 strain), DefA (X1 strain), or both (CxD) (Fig. 2, Table 1). AntiPlasmodium effect of CecA was clearly higher than that of DefA, however, a combination of both in CxD mosquitoes had the strongest inhibition of Plasmodium oocyst development (Fig. 2). The latter clearly showed cooperative action of DefA and CecA in antiPlasmodium defense.

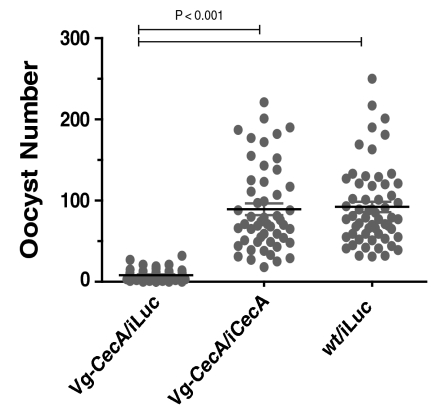

Fig. 3.

RNA interference depletion of CecA to test the functional effect of CecA overexpression on P. gallinaceum infection. Wt and transgenic Vg-CecA female mosquitoes (C32 strain) were injected with CecA or control luciferase dsRNA. One week later mosquitoes from each treated group were blood fed on the same infected chick. Mosquito midguts were dissected 7 days postinfection and scored for oocyst numbers: Vg-CecA/iLuc, Vg-CecA transgenic mosquitoes treated with luciferase dsRNA (control); Vg-CecA/iCecA, Vg-CecA transgenic mosquitoes treated with CecA dsRNA; wt/iLuc, wt mosquitoes treated with luciferase dsRNA (control for infection). Data represents the result of 3 independent experiments for each transgenic and control strains.

Table 1.

Inhibition of oocyst proliferation in transgenic mosquitoes after a single blood meal on Plasmodium-infected chickens

| Wild-type | VgR3 | Vg-CecA | Vg-DefA | Vg-CecA/DefA | |

| EXP1 | 116.2* (124–195) 11MG† | 151.7 (99–185) 10MG | 9.2 (5–16) 10MG | 27.2 (5–56) 11MG | 9.3 (4–15) 11MG |

| EXP2 | 192.3 (152–233) 12MG | 182.2 (121–222) 10MG | 11 (6–19) 10MG | 33.8 (6–67) 10MG | 11.1 (6–18) 11MG |

| EXP3 | 155.4 (103–172) 11MG | 7.9 (4–14) 11MG | 17.7 (4–35) 10MG | 6.5 (3–11) 12MG | |

| EXP4 | 126.2 (82–155) 10MG | 7.7 (3–14) 11MG | 14.9 (4–32) 11MG | 4.3 (0–10) 11MG | |

| EXP5 | 146.5 (97–188) 12MG | 9.9 (0–21) 11MG | 20.1 (4–37) 12MG | 4.7 (0–14) 14MG |

EXP1–5—independent experiments utilizing separate cohorts of mosquitoes.

*The mean oocyst number per midgut. The range of observed values is indicated in parentheses.

†The total number of mosquito midguts examined.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of oocyst proliferation in transgenic mosquitoes. Wt and transgenic VgR3 (control unrelated transgenic strain), Vg-CecA C32, Vg-DefA X1, and Vg-DefA/Vg-CecA CxD hybrid mosquitoes were blood fed on the same P. gallinaceum infected chick, 7 days postinfection mosquito midguts were dissected and the numbers of developed oocysts were scored. The data of 3 independent experiments were pooled for each transgenic and control strains.

To be sure that in transgenic strains the AMP overexpression itself inhibits development of oocysts after blood feeding and is not dependent on a genetic background of these strains, we performed RNAi knockdown experiments to eliminate or reduce level of CecA mRNA (Fig. S4). Control wt and C32 mosquitoes were used for injection of dsRNA. Oocyst number observed in C32 strain injected with CecA dsRNA reached about the same level as control wt strain injected with control Luc dsRNA, P < 0.001 (Fig. 3). In contrast, C32 strain injected with Luc dsRNA show very low oocyst number (about 10 times less) and similar to that which typically observed in these transgenic mosquitoes (Fig. 2, Table 1). These data indicated that reduction of oocyst number in C32 transgenics depended on overexpression of the CecA transgene and not genetic background of this particular strain. Specific silencing of overexpressed CecA transgene by dsRNA reversed the antiPlasmodium immune phenotype in the C32 transgenic strain.

Next, we analyzed whether extending the expression of transgenes over time would affect the Plasmodium development. First, the transgenic and wt mosquitoes were blood fed on the same P. gallinaceum-infected chick. Several mosquitoes from each strain were dissected, and the number of oocysts per gut was determined at 7–8 d PIBM; these were similar to the first experiment (Table 1, EXP 3–5). To reactivate the transgenes, most of the mosquitoes were then blood fed on a naive chick at 7 d PIBM. On the 14th day PIBM, the number of sporozoites per salivary gland was determined. Both Vg-CecA and Vg-DefA transgenic strains had significantly reduced numbers of sporozoites in their salivary glands compared with the wt mosquitoes (Table 2). Number of sporozoites in the Vg-CecA C32 strain was significantly less than in the Vg-DefA X1 strain suggesting that CecA exhibited a higher antiPlasmodium activity than DefA (Table 2). Importantly, no sporozoites were detected in salivary glands of the CxD mosquitoes after reactivation of both transgenes by feeding on a naive chick at 7 d PIBM (Table 2).

Table 2.

Blocking of Plasmodium transmission in transgenic mosquitoes co-overexpressed DefA and CecA

| Wild-type | Vg-CecA | Vg-DefA | Vg-CecA/DefA | ||

| Exp 3 | *Sporozoite # per a SG | 12210 (8410–17430) | 350 (0–560) | 660 (40–1240) | 0 (0–0) |

| †Parasitemia (%)/chicks # | 15% (5–20%)/9 | 1% (0–4%)/9 | 3% (0–9%)/8 | 0% (0–0%)/11 | |

| ‡Oocyst # per a midgut | 42 (11–79) | 1 (0–6) | 2 (0–11) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Exp 4 | *Sporozoite # per a SG | 8950 (5840–15740) | 315 (0–610) | 573 (30–970) | 0 (0–0) |

| †Parasitemia (%)/chicks # | 12% (0–18%)/10 | 0.5% (0–2%)/9 | 2.1% (0–4%)/9 | 0% (0–0%)/10 | |

| ‡Oocyst # per a midgut | 29 (0–62) | 1 (0–4) | 1.5 (0–7) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Exp 5 | *Sporozoite # per a SG | 12950 (7820–17210) | 380 (0–770) | 1542 (10–11200) | 0 (0–0) |

| †Parasitemia (%)/chicks # | 14% (0–22%)/9 | 2% (0–3%)/9 | 3% (0–5%)/9 | 0% (0–0%)/10 | |

| ‡Oocyst # per a midgut | 34 (0–88) | 1 (0–5) | 2 (0–12) | 0 (0–0) |

*Plasmodium-infected mosquitoes from independent cohorts of EXP3-5 (Table 1) were fed on naive chickens on day 14 postinfection. This was done to reactivate the production of CecA and DefA in transgenic strains. The mean sporozoite number per a salivary gland. The range of observed values is indicated in parentheses.

†Mosquitoes from the same batches were then fed on naive chickens. Parasitemia of these chickens was established by examining red blood cells for the presence of Plasmodium infection. Parasitemia is expressed as the mean percentage of infected to total red blood cells examined. The range of observed value in an individual chick is indicated in parentheses.

‡Wt naive mosquitoes were blood fed on an individual chicken tested for parasitemia levels in each column of†. The oocyst number in there midguts was 7 days after blood feeding. The mean oocyst number per midgut and the range of observed values (in parentheses) are indicated.

To determine whether transgenic mosquitoes could still transmit Plasmodium, we blood fed each mosquito on a naive chick at 14 d PIBM prior to examination for sporozoites. After 9 d, the parasitemia level in individual chicks was determined, then each chick was used for blood feeding of naive wt mosquitoes, and finally the number of oocysts in each mosquito midgut was determined 7–8 d later (30–31 d PIBM) (Table 2). Although we observed a significant decline in the number of oocysts in the midgut and sporozoites in the salivary gland of the Vg-CecA and Vg-DefA strains compared with the control wt mosquitoes, both of these transgenic strains were still able to transmit the Plasmodium. However, when we used the CxD mosquitoes as a vector, we could detect neither any parasitemia in tested chicks nor oocysts in the midguts of naive wt mosquitoes fed on these chicks (Table 2). Therefore, we observed that the systemic co-overexpression of DefA and CecA hindered the development of Plasmodium, causing a significant reduction in the number of oocysts and sporozoites in the transgenic mosquitoes. Most importantly, in the CxD mosquitoes, the second simultaneous reactivation of these two AMPs by a blood meal completely blocked Plasmodium transmission.

Discussion

We used the yellow fever mosquito, Ae. aegypti, as a vector model because it is amenable to both transgenesis and reverse-genetic analysis. Its eggs can be stored for many months, making it possible to maintain a long-term large genetic stock. Moreover, Ae. aegypti pair wise crossing makes developing hybrid strains possible. The 5′ regulatory region of the Ae. aegypti Vg gene sufficient for a high level blood meal-activated, sex- and tissue-specific expression (21) was used in this study for expression of effector molecules. The Vg gene is highly activated exclusively in the fat body, the tissue central for production of AMPs. The Vg gene expression is cyclic as it is tightly linked to separate blood meals making it possible to manipulate expression of effector molecules by repeated blood feedings (21).

The site of expression of antipathogen effector molecules is an important consideration in enhancing antipathogen phenotype in transgenic mosquitoes. Overexpression of effector molecules via the fat body-specific promoter results in secretion of these products into the hemolymph affecting two stages of Plasmodium: oocysts and sporozoites. It has been shown that after the release from mature oocysts and prior to invasion of the mosquito salivary glands, large number of sporozoites undergoes massive destruction by humoral factors in the hemolymph (27). Simultaneous utilization of transgenes with promoters driving effector molecules in different tissues (i.e., the midgut and the fat body), affecting different stages of the parasite development could be even more effective for transmission blocking.

In this work, we have shown that co-overexpression of two effector molecules with antipathogen action in the same transgenic mosquito results in a total refractory phenotype. Two AMPs, CecA and DefA, completely blocked P. gallinaceum transmission when they are produced by the Ae. aegypti fat body and secreted into the hemolymph in a blood meal-activated manner. These experiments have clearly demonstrated cooperative action of these AMPs against Plasmodium. Interestingly, in the in vivo environment of the transgenic Ae. aegypti, CecA alone had notably higher negative effect on Plasmodium development than DefA. Further tests of the mosquito-Plasmodium system (particularly, An. gambiae–P. falciparum) should reveal whether antiPlasmodium action by CecA can be augmented by another effector even stronger than by DefA.

Although the mechanism of AMP action on parasitic protozoa is not well understood, they appear to possess potent antiprotozoan properties. In earlier studies, exogenous AMPs, purified from other insect species, have been tested for activity against Plasmodium. Two defensins, one from the dragon fly Aeschna cyanea and the other from the flesh fly Phormia terranovae, have been reported as having a profound toxic effect on the development of P. gallinaceum oocysts in the midgut of Ae. aegypti as well as on isolated sporozoites (28). The midgut-specific activation of CecA in the transgenic An. gambiae resulted in 60% reduction of Plasmodium oocysts (13). In addition, the adverse effects of cecropins have been observed on other pathogens such as Leishmania (29).

In Ae. aegypti, transgenic overexpression of REL2 by the fat body leads to increased resistance to bacterial infection as well as partial refractoriness toward P. gallinaceum (11). The Imd/REL2 is also important in An. gambiae for resisting P. berghei (30). RNA interference experiments to deplete Caspar, the negative regulator of Imd pathway, have shown that the pathway is involved in regulating resistance of A. gambiae and other anopheline species to the human malaria parasite P. falciparum (31). Nevertheless, these studies have not provided a clear link between AMPs and the antiPlasmodium defense. Indeed, defensins and cecropins do not appear to be a part of natural mosquito defense against Plasmodium species. Transcriptomic analyses have shown that the infection of An. gambiae by either P. falciparum or P. berghei does not elicit the activation of defensins and cecropins (32, 33). In agreement, RNA interference depletion of defensins and cecropins did not affect in vivo Plasmodium development in mosquitoes (32, 33). It is, however, different from the transgenic activation of these AMPs linked to blood feeding. Appearance of the high level of AMPs, CecA and DefA, at the time of parasite acquisition by a mosquito clearly has a detrimental effect on Plasmodium development.

In conclusion, we report the genetic engineering of transgenic Ae. aegypti mosquitoes with a blood meal dependent systemic activation of two major mosquito AMPs, CecA and DefA. Co-overexpression and cooperation of CecA and DefA in these mosquitoes limit the proliferation of the highly pathogenic bacteria P. aeruginosa. These AMPs appear to work cooperatively against Plasmodium developmental stages, completely blocking the parasite transmission. Our present study suggests a unique approach in generating transgenic mosquitoes with antiPlasmodium refractory phenotype, which is coexpression of two or more effector molecules with cooperative action on the parasite. Based on our study, it appears that a combinatorial overexpression of several antiparasitic effector molecules in genetically modified mosquitoes will provide a potent tool for preventing transmission of Plasmodium in human malaria vectors.

Methods

Generating Transgenic Mosquitoes.

The Ae. aegypti wt Rockefeller/UGAL strain used in these experiments was reared at 27 °C and 80% humidity. Three- or four-day old previtellogenic females were fed on anaesthetized rats. Newly laid eggs were collected and prepared for microinjection as described previously (8, 10). The 293 nucleotide-long Ae. aegypti CecA cDNA was isolated by means of RT-PCR and used for construction of transformation vector. A DNA fragment containing the 1.8 kb 5′ regulatory region of the Vg gene linked to the CecA cDNA was subcloned into the pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm] in the AscI unique cloning sites. The resulting pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm, Vg-CecA] donor plasmid was purified using the QIAfilter kit (Qiagen). The pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm, Vg-Cec] donor plasmid and the phsp-pBac helper plasmid were mixed in a buffer containing 5 mM KCl and 0.1 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 6.8) at final concentrations of 0.35 μg/mL and 0.25 μg/mL, respectively. Transformation of Ae. aegypti and selection of transformed strains have been performed by a well-established methodology [(5, 22), and SI Text].

Southern, Northern, and immunoblot (Western) blot analyses were performed using standard methodologies (SI Text).

RT-PCR, Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis, and Inverse PCR.

To remove any genomic contamination, 3 μg total RNA was mixed with amplification-grade Dnase I (Gibco BRL/Invitrogen). Then, 2 μg RNA treated with Dnase I was directly used in a cDNA synthesis reaction using the Omniscript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Qiagen). Levels of cDNA in the different samples were quantified using real-time PCR. The real-time PCR master mix, iQ Supermix (BioRad) was utilized. All reactions for real-time PCR were run in triplicate using 2 μL cDNA per reaction. The PCR reactions were performed using an iCyler real-time PCR machine (BioRad). For sequences of primers and probes used in the RT-PCR reactions, see SI Text.

Inverse PCR analysis was done with genomic DNA isolated from transgenic female mosquitoes. Endonucleases Taq I and Msp I were used for digestion of genomic DNA to identify 5′ and 3′ junctions, respectively. For inverse PCR reactions the following primers were used: forward, 5′-TCTTGACCTTGCCACAGAGG-3′, reverse, 5′-TGACACTTACCGCATTGACA-3′ (for TaqI digestion); and forward, 5′-GTCAGTCCAGAAACAACTTTGGC-3′, reverse, 5′-CCTCGATATACAGACCGATAAAAACACATG-3′ (for Msp I digestion).

Survival Test and Bacterial Proliferation Study.

Transgenic and control female mosquitoes, 24 h PBM, were injected with different strains of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. In survival test experiments, groups of 20 females were inoculated by pricking the mosquitoes with a Hamilton 33S needle that had been dipped into medium containing freshly growing bacteria in their exponential phase after 6 h of culturing. The survival rate was calculated 72 h after bacterial injection, because mortality no longer occurred beyond this time.

For the bacterial proliferation study of P. aeruginosa, the overnight-grown bacterial medium was diluted 10-fold with distilled water to a final concentration 3 × 108 CFU/mL, before being used for infection. Infected mosquitoes, collected 5 h after bacterial challenge, were ground up in distilled water, and the resulted supernatant was plated onto LB agar plates. Bacterial colonies were grown for 14–16 h at 37 °C, after which colony counts were scored.

Mass Spectrometry.

For hemolymph collection Ae. aegypti female mosquitoes were decapitated, and their last two abdominal segments were cut off. Mosquitoes prepared in this way were then centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 5 min, and the collected supernatant was used for analysis. Hemolymph samples were pulled from 35–40 females of each of the wt and hybrid CxD mosquitoes and subjected to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS analysis.

Plasmodium Infection.

P. gallinaceum was maintained by transmission between mosquitoes of the wt strain and White Leghorn chicks. All the experimental animals were housed in cages in the psychology building vivarium, and all procedures were preapproved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (see SI Text for detail).

RNA Interference Gene Depletion.

For CecA gene silencing experiments we generated cDNA by RT-PCR and then produced the double stranded RNA (dsRNA) using T7 RNA polymerase. RNA interference gene depletion experiments were essentially performed as previously described [(34) and SI Text].

Statistics.

Individual survival rate curves after bacterial injections were built by the approach of Kaplan–Meier; meanwhile, curves of different groups were compared by both the log-rank and the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests.

P. gallinaceum infection data from three independent experiments were combined and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov goodness of fit test was done essentially as described (34). Statistically significant difference between samples was evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U test (Graphpad 5.0).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors thank Dr. Bruce Christensen for providing anticecropin antibodies. This work has been supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant 1 R01 AI059492.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1003056107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gratz NG. Emerging and resurging vector-borne diseases. Annu Rev Entomol. 1999;44:51–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill CA, Kafatos FC, Stansfield SK, Collins FH. Arthropod-borne diseases: vector control in the genomics era. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3(3):262–268. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alphey L, et al. Malaria control with genetically manipulated insect vectors. Science. 2002;298(5591):119–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1078278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James AA. Gene drive systems in mosquitoes: rules of the road. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21(2):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jasinskiene N, et al. Stable transformation of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, with the Hermes element from the housefly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(7):3743–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catteruccia F, et al. Stable germline transformation of the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Nature. 2000;405(6789):959–962. doi: 10.1038/35016096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kokoza V, et al. Engineering blood meal-activated systemic immunity in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(16):9144–9149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160258197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lombardo F, Lycett GJ, Lanfrancotti A, Coluzzi M, Arca B. Analysis of apyrase 5′ upstream region validates improved Anopheles gambiae transformation technique. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin SW, Kokoza V, Lobkov I, Raikhel AS. Relish-mediated immune deficiency in the transgenic mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(5):2616–2621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0537347100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bian G, Shin SW, Cheon HM, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. Transgenic alteration of Toll immune pathway in the female mosquito Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(38):13568–13573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502815102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonova Y, Alvarez KS, Kim YJ, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. The role of NF-kappaB factor REL2 in the Aedes aegypti immune response. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39(4):303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito J, Ghosh A, Moreira LA, Wimmer EA, Jacobs-Lorena M. Transgenic anopheline mosquitoes impaired in transmission of a malaria parasite. Nature. 2002;417(6887):452–455. doi: 10.1038/417452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim W, et al. Ectopic expression of a cecropin transgene in the human malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae): Effects on susceptibility to Plasmodium. J Med Entomol. 2004;41(3):447–455. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franz AW, et al. Engineering RNA interference-based resistance to dengue virus type 2 in genetically modified Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(11):4198–4203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600479103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jasinskiene N, et al. Genetic control of malaria parasite transmission: Threshold levels for infection in an avian model system. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76(6):1072–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterhouse RM, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007;316(5832):1738–1743. doi: 10.1126/science.1139862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenberger C, et al. Insect immunity: isolation of three novel inducible antibacterial defensins from the vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;25(7):867–873. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(95)00043-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowenberger CA, et al. Mosquito–Plasmodium interactions in response to immune activation of the vector. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91(1):59–69. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vizioli J, et al. Cloning and analysis of a cecropin gene from the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9(1):75–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kokoza VA, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the mosquito vitellogenin gene via a blood meal-triggered cascade. Gene. 2001;274(1-2):47–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00602-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokoza V, Ahmed A, Wimmer EA, Raikhel AS. Efficient transformation of the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti using the piggyBac transposable element vector pBac[3xP3-EGFP afm] Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;31(12):1137–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaway JE, et al. Modification of the C terminus of cecropin is essential for broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(8):1614–1619. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau GW, et al. The Drosophila melanogaster toll pathway participates in resistance to infection by the Gram-negative human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 2003;71(7):4059–4066. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4059-4066.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apidianakis Y, et al. Profiling early infection responses: Pseudomonas aeruginosa eludes host defenses by suppressing antimicrobial peptide gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(7):2573–2578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409588102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho KH, Cheon HM, Kokoza V, Raikhel AS. Regulatory region of the vitellogenin receptor gene sufficient for high-level, germ line cell-specific ovarian expression in transgenic Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36(4):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillyer JF, Barreau C, Vernick KD. Efficiency of salivary gland invasion by malaria sporozoites is controlled by rapid sporozoite destruction in the mosquito haemocoel. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37(6):673–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.12.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahabuddin M, Fields I, Bulet P, Hoffmann JA, Miller LH. Plasmodium gallinaceum: Differential killing of some mosquito stages of the parasite by insect defensin. Exp Parasitol. 1998;89(1):103–112. doi: 10.1006/expr.1998.4212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akuffo H, Hultmark D, Engstom A, Frohlich D, Kimbrell D. Drosophila antibacterial protein, cecropin A, differentially affects non-bacterial organisms such as Leishmania in a manner different from other amphipathic peptides. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1(1):77–82. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meister S, et al. Immune signaling pathways regulating bacterial and malaria parasite infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(32):11420–11425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garver LS, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(3):e1000335. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong Y, et al. Anopheles gambiae immune responses to human and rodent Plasmodium parasite species. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(6):e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blandin S, et al. Reverse genetics in the mosquito Anopheles gambiae: Targeted disruption of the Defensin gene. EMBO Rep. 2002;3(9):852–856. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou Z, et al. Mosquito RUNX4 in the immune regulation of PPO gene expression and its effect on avian malaria parasite infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(47):18454–18459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804658105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.