1 Introduction

1.1 A brief account of the chemical shift

The chemical shift of a nucleus, i, in a molecule arises from the nuclear shielding effect of an applied magnetic field, caused by an induced magnetic field resulting from circulation of surrounding electrons [1–6]. The magnitude of such an induced magnetic field is proportional to the strength of the applied external magnetic field B0, so that the effective field Beff at the nucleus is given as

| (1) |

where σi is the second-rank nuclear shielding tensor and 1 is the unit matrix. In normal NMR experiments B0 is a uniform field along the z-axis; therefore, σi= σizz. The resonance NMR frequency, νi, of a given nucleus in a molecule is thus related to its gyromagnetic ratio, γi, as given by

| (2) |

The most commonly used isotropic chemical shift (ppm) δi parameter is defined as the difference between the resonance frequency of a nucleus of interest, νi, and that of a reference nucleus, νref [1–4,6]:

| (3) |

In normal NMR experiment B0 is uniform field along z. Only 1 term survives so that νi = (γi/2π)B0 (1− σizz). In an isotropic, liquid sample we can replace σizz by σI and δi is a scalar quantity due to the fast tumbling of molecules as shown below by an average parameter, δiso. In a solid or oriented samples (such as a liquid crystalline or single crystalline sample), the chemical shift is not an isotropic parameter but is a second-rank tensor. The components of the anisotropic chemical shift tensor in these samples can be specified by δij; where i,j = x, y, or z in a reference frame fixed on the nucleus in a molecule. A transformation of the shielding tensor to a frame of reference defined by axes X, Y, and Z [in the principal axis system (PAS)] diagonalizes the matrix to give the three principal components (δXX, δYY, δZZ). The isotropic average of the tensor is given by

| (4) |

In the “Haeberlen notation”, each of the three principal components is related to δiso by [7,8]:

| (5) |

where δZZ is the principal component farthest from the isotropic value, and δYY is the component closest to δiso: the ordering of the components can be either δZZ ≥ δYY ≥ δXX or δZZ ≤ δYY ≤ δXX, depending on the chemical structure in question. Therefore, the “reduced anisotropy” is defined as

| (6) |

or

| (7) |

These two definitions are related by

| (8) |

The shielding asymmetry η is defined as

| (9) |

In the “Mehring notation”, the principal components, δ11, δ22 and δ33, are defined as [9],

| (10) |

Analogous to Eq (4), the definition of an isotropic shielding is given as

| (11) |

but the relationships for anisotropy and asymmetry are more difficult to express than that under the Haeberlen convention, since they depend on the position of σ22 between σ11 and σ33 [7,9].

These anisotropy/asymmetry conventions can be replaced by span (Ω) and skew (κ) parameter with the following definitions [7,10]:

| (12) |

| (13) |

In the case of a symmetric nuclear site, however, those components may be expressed relative to the symmetry axis, δ|| (δ11) and its perpendicular axes δ⊥ (δ22 and δ33), with the chemical shielding (or shift) anisotropy

| (14) |

The magnitude of the anisotropy Δδ and the asymmetric parameter η are also defined as

| (15) |

and

| (16) |

Here, δ|| =δ11 and δ⊥ = (δ22 + δ33)/2.

Undoubtedly, the nomenclature based on the chemical shift parameter δii is directly related to the chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) which is one of the main topics discussed in this article. Nevertheless, there are many previous papers utilizing shielding constants δi’s, instead chemical shifts δ’s. In such cases, it should be bore in mind that Δδ = − Δσ and σ33 ≥ σ22 ≥ σ11.

Isotropic chemical shifts of nuclei in different chemical groups of a molecule, are usually available from a solution sample [1–6] where there is motional averaging of the anisotropic shielding tensor. They are undoubtedly one of the most important NMR parameters measured from high-resolution NMR experiments, besides other parameters such as spin coupling constants and nuclear relaxation times, for determining primary or secondary structures of molecules, their dynamics, intermolecular interactions, etc. The chemical shift anisotropy (CSA) is usually obtained from NMR experiments on a solid or a liquid crystalline sample; the corresponding isotropic chemical shifts can also be measured from solid samples [11–15]. It should be mentioned that CSA is an important source of spin-lattice (T1) and spin-spin (T2) relaxation at high magnetic fields even for solution samples, although not affecting the shapes of solution NMR spectral lines. The contribution of the CSA to T2, and hence the width of the resonance increases with magnetic field strength leading to broad, unresolved lines.

Under such circumstances, transverse relaxation-optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) [16–20] can be utilized to record well-resolved spectra of large proteins or protein complexes with molecular weight on the order of 100 kDa, with the advantage of an attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and CSA under the proton-coupled condition. For this purpose, it is essential to have a prior knowledge of the magnitude of the CSA values for nuclei under consideration to optimize the condition for TROSY-type experiments. This has stimulated much interest in evaluating the CSA values of nuclei in individual amino acid residues of large globular proteins in aqueous solutions or micelles. Determination of residue-specific 15N CSA for proteins in solution is now feasible by careful evaluation of T1 and T2 values at various external magnetic fields [21]. Such data are currently available from the literature. It is emphasized here that we are now in an era when solid-state and solution NMR approaches are frequently utilized in the analyses of CSA parameters and their applications for structural and dynamical studies of biomolecules.

It is therefore very important to gain insights into how and to what extent the isotropic or anisotropic chemical shift of a nucleus under consideration are related to molecular and electronic structure. The existence of conformation-dependent chemical shifts was initially recognized for a variety of biological molecules by solid-state NMR studies on polypeptides, polysaccharides, antibiotics, and so on [22–24] and later by a careful examination of a robust database of chemical shifts available from multidimensional NMR studies of globular proteins in aqueous solution [25–28]. Detailed analyses of such data showed that these chemical shift parameters are indispensable restraints for determining 3D structures of large proteins with or without the usual NOE constraints. Chemical shift anisotropies (CSAs) of individual nuclei were initially obtained by solid-state NMR studies on single crystalline, static, or slowly rotating samples. These CSA parameters for nuclei in challenging proteins are now also available from samples using fast magic angle spinning (MAS) experiments [29].

The values of isotropic and anisotropic chemical shift parameters accumulated so far have been utilized to reveal either secondary or 3D structures of fibrous, membrane and globular proteins in solid-state or aqueous solution-state [22–30]. Further, CSA parameters are essential to characterize atomic-level dynamics in the solid-state, or to search for an optimal condition for obtaining TROSY spectra on globular proteins of larger molecular weight, and also to determine relaxation mechanisms in solution. In particular, the chemical shifts are now utilized as a means to reveal 3D structures of large globular proteins, in the absence of NOE constraints which are difficult to obtain because of broad resonances with low signal-to-noise ratio.

Because of the increasing interest in utilizing CSA parameters, there has been a plethora of studies determining CSA values of nuclei in different types of samples. There are several excellent review articles that deal with the topics of isotropic [22–28] and anisotropic [29–39] chemical shifts. In this review, it is our intention to deal equally with these topics from both solid-state and solution NMR studies based on the recent progress in the field, especially dealing with these studies from a historical point of view. Emphasis, however, is also made on how to reveal necessary chemical and biological insights into a variety of biological molecules, including peptides, proteins, lipids, etc. using isotropic or anisotropic chemical shift data. However, we believe that our treatment can also be extended to other areas of chemistry. In the solid-state, unlike in solution, the chemical shielding experienced by a nucleus depends on the direction of the applied magnetic field in the molecule frame. Therefore the Hamiltonian for the Zeeman interaction, HCSA, in the solid-state is given by:

| (17) |

Thus, the chemical shift tensor component δzz as stated above is related to components δ11, δ22 and δ33 in the molecular principal axis system (PAS) frame by,

| (18) |

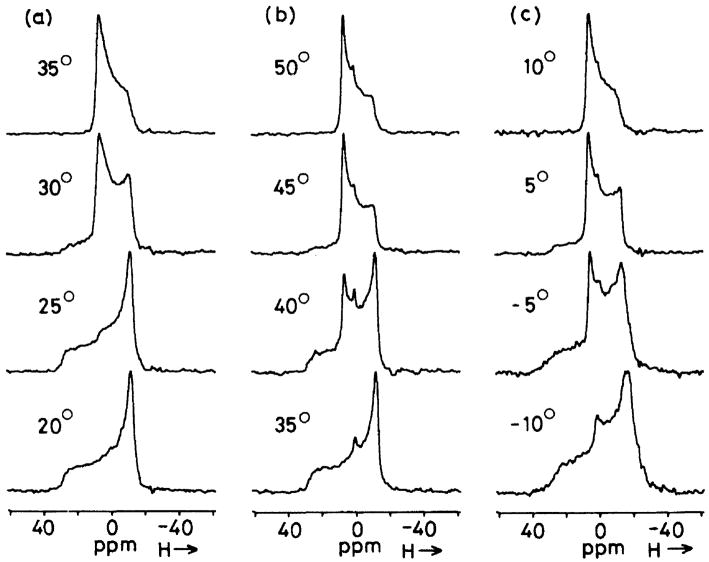

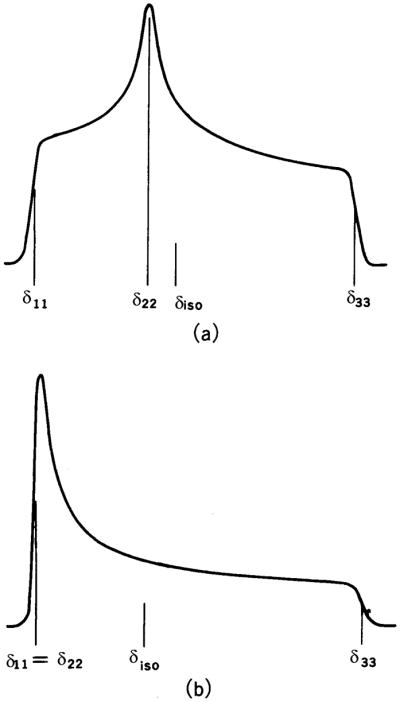

| (19) |

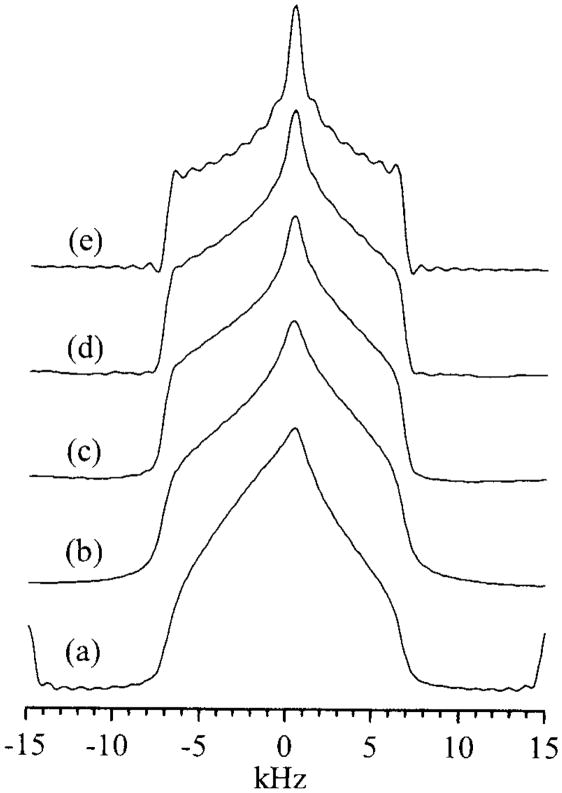

where α and β are the polar angles that the field B0 makes in the PAS (X, Y, and Z) molecular frame (Fig. 1A) for single crystals or oriented samples [1,2]. An NMR signal from microcrystalline or powder samples arises from the sum of all possible contributions of α and β angles (powder pattern), for either axially symmetric (left) (δ11= δ22≠δ33) or (axially) asymmetric (right) (δ11≠ δ22≠ δ33) as illustrated in Fig. 2. The principal components of the CSA tensor can be obtained from the peak at δ22 as well as the two edges at δ11 and δ33 of the powder pattern signal.

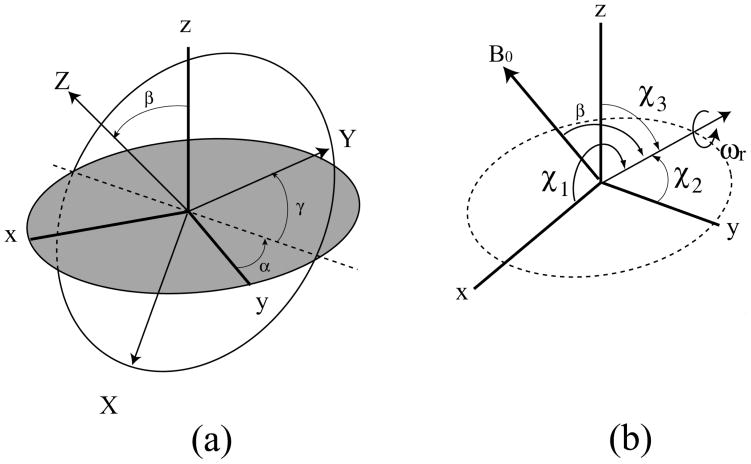

Fig. 1.

(a) Euler angles which relate principal axis system (X,Y, and Z) in a molecule and laboratory frame (x, y, and z, in which z is taken along the direction of applied field. (b) Sample is rotated with angular velocity of ωr about an axis inclined at an angle of β to the applied field B0 at angles χ1, χ2, and χ3 to the principal axes of σ. Magic angle for β = 54°44′

Fig. 2.

Powder pattern spectra for spin ½ nuclei. (a) axially asymmetric (δ11 ≠ δ22 ≠ δ33), (b) axially symmetric (δ11 = δ22 ≠ δ33). δiso = (1/3)(δ11 + δ22 + δ33).

The chemical shift of an nucleus depends on its electronic and molecular environment [2] and can be given in terms of various contributions by the following equation.

| (20) |

where σd is known as the diamagnetic term, σp the paramagnetic term, and σ′ is a term from neighbors which accounts for the magnetic anisotropy effect, polar effect, ring current effect, etc. Intrinsically, σ is a tensor quantity, from a theoretical point of view, which depends on its electronic and molecular environments [1,3,4,7]. Indeed, by placing the nucleus of interest and the zero point of the vector potential due to the external magnetic field at the origin, the contributions to σd and σp are given by:

| (21) |

where α and β are subscripts labeling the Cartesian components (x, y or z), μ0 is the vacuum permeablity, e is the elementary charge and m is the electron mass, rk is the position of the kth electron compared to the nucleus of interest. Lk is the corresponding orbital angular momentum operator, δαβ is the Kronecker delta function. |0> and |n> refer to the electronic ground and excited states of molecules with energies E0 and En, respectively.

The paramagnetic term in the case of a nucleus for 13C, 15N and 17O atoms having 2, 3 and 4 2p electrons considered here, in particular, is expressed as a function of excitation energy, bond order, and electron density according to the sum-over-states method in a simple form as follows [40]

| (22) |

where (Em − Em) the singlet-singlet excitation energy between the nth occupied orbital and the mth unoccupied orbital, and Qαβ is a factor including the bond order and the electron density. The quantity <r−3>2p is the spatial dimension for a 2p electron, and C is the coefficient incorporating the universal constants. The term σpαβ can be evaluated by a variety of molecular orbital calculations, such as semi-empirical, non-empirical, or ab initio MO methods. It should be noted that a quantum chemical calculation gives all nine chemical shielding tensor components of the CSA tensor. The isotropic chemical shielding constant is obtained as an average of the magnitudes of the three principal components of the chemical shielding tensor. The chemical shielding anisotropy, therefore, arises from the distortion from symmetry of the distribution of electrons around a nucleus in molecules in the presence of the applied magnetic field. Using these procedures, it is possible to calculate the chemical shielding tensor components of a nucleus in a molecule with any specified conformation.

As mentioned above, the CSA originates from a distortion from a spherical distribution of 2p electrons around a nucleus. Each of the three diagonal shielding tensor components is more sensitive to structural changes such as torsion angle and hydrogen bonding as compared to the average isotropic shielding constant. Also, the directions of the principal axes of the shielding tensor depend on the molecular structure. Therefore, the determination of the orientation of the principal axes in the molecular frame gives us detailed information about the molecular structure.

For atoms with 2p electrons such as 13C, 15N and 17O considered in polypeptides and proteins, the relative chemical shift is predominantly contributed by σp and is little contributed by σd and σ′. Thus, it is very important to estimate σp values with good precision for these nuclei. On the other hand, for a 1H nucleus the relative chemical shift is more significantly determined by contributions from σd and σ′ as compared to σp. The σd can be easily estimated from the calculated electron density. Using these procedures, one can calculate the chemical shift tensor components of a nucleus in a molecule with any specified conformation [41–54]. A negative sign of the chemical shielding constant σ indicates deshielding and so shielding variations can be compared with the observed chemical shift δ where a positive sign denotes deshielding.

1.2 Determination of CSA values

Several approaches have been proposed to determine CSA tensors: (1) static NMR measurements on a single crystal or an oriented liquid crystalline sample, (2) simulations of static powder pattern spectra obtained from polycrystalline samples, (3) analysis of spinning sidebands in MAS spectra obtained under slow-spinning conditions, (4) CSA recoupling procedures based on multidimensional, fast-spinning MAS NMR. All six CSA parameters, including the three principal values δ11, δ22 and δ33 and three direction cosines specifying the principal axis system, can be unambiguously determined by performing NMR experiments on single crystals. Some of direction cosines are also available from experimental measurements on uniaxially oriented samples. Further, relative orientations of such principal axes with respect to the 13C-15N bond axis can be also determined from [13C, 15N]-doubly labeled polycrystalline samples. In many cases, isotope enrichment by 13C, 15N and 17O nuclei is essential in order to determine reliable and precise CSA parameters.

1.2.1 Single crystal or aligned samples

The experimental procedures to determine CSA values from single crystals by a stepwise rotation of a sample holder attached to a goniometer are well documented [9,31,55]. Static NMR signals available from a single crystal in the laboratory frame as shown in Eq.(17) should be converted into the principal values (Eq. (18)) through transformations of coordinate frames: from laboratory frame → goniometer frame → crystal frame → principal axis frame. For this purpose, it is essential to have a prior knowledge of the 3D structure of the molecule under consideration in the crystal frame determined either by X-ray or neutron diffraction study. The magnitudes of the principal values and direction cosines can be determined by fitting the observed chemical shift frequencies, obtained by stepwise rotation of the direction of a crystalline sample relative to the applied magnetic field, to Eqs. (18) and (19).

Such analyses, however, can be more complicated for quadrupolar nuclei such as 17O (spin number 5/2), since the central (½↔−½) transition signal becomes broad by the second-order perturbation by the very large quadrupolar interaction [11]. The quadrupolar interaction (νQ) in addition to the chemical shift tensor interaction (νCS) is expressed by

| (23) |

where

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

| (28) |

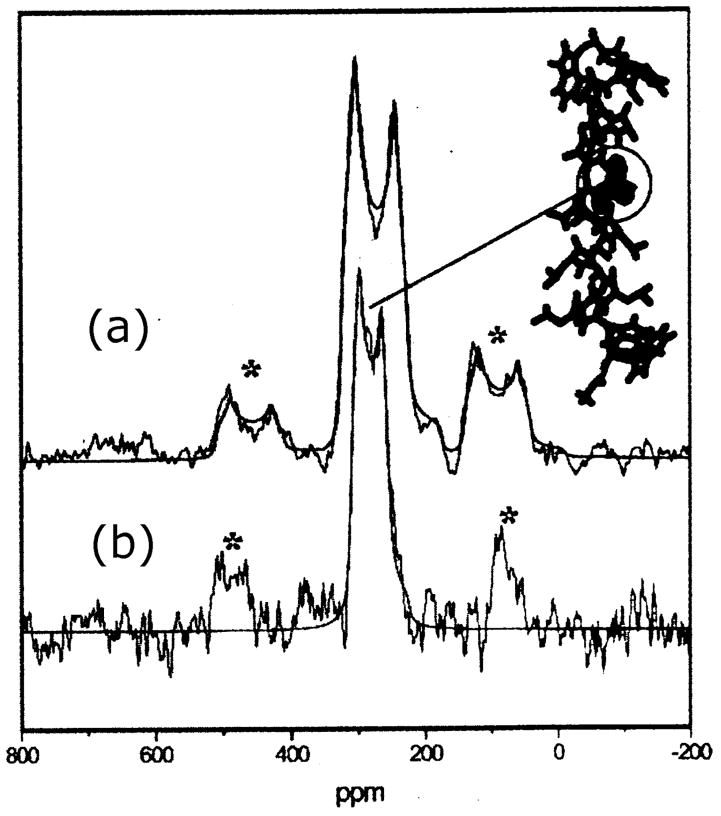

Here, θ and φ are the polar and azimuthal angles, respectively, in the principal axes of the electric field gradient tensor, e2qQ/h is the quadrupolar coupling constant, and ηQ is the asymmetry factor of the electric field gradient defined by its principal components VXX, VYY and VZZz. Recording 17O spectra at the highest magnetic field currently available is essential in order to minimize the relative contributions of the quadrupolar interaction which is decreased at a higher field, as seen from the νQ2/nu;0 factor in Eq. (23). It is also important to measure static spectra at several magnetic field strengths, in order to determine the total eight parameters including the quadrupolar coupling constant and asymmetry factor ηQ.

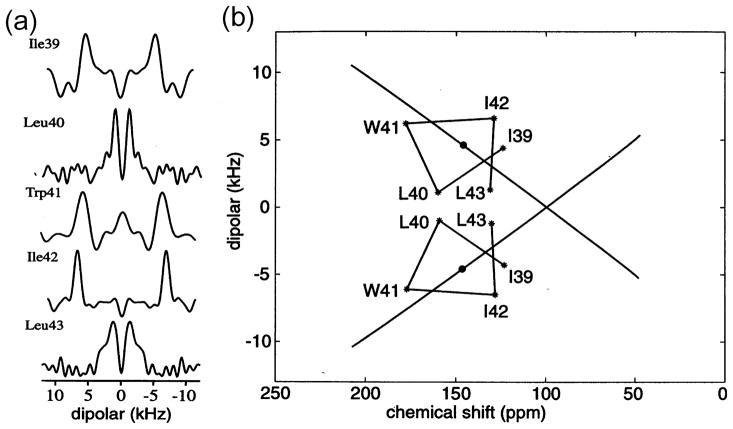

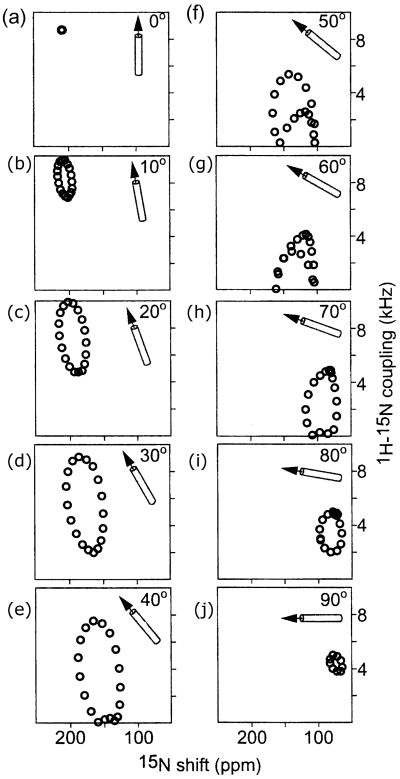

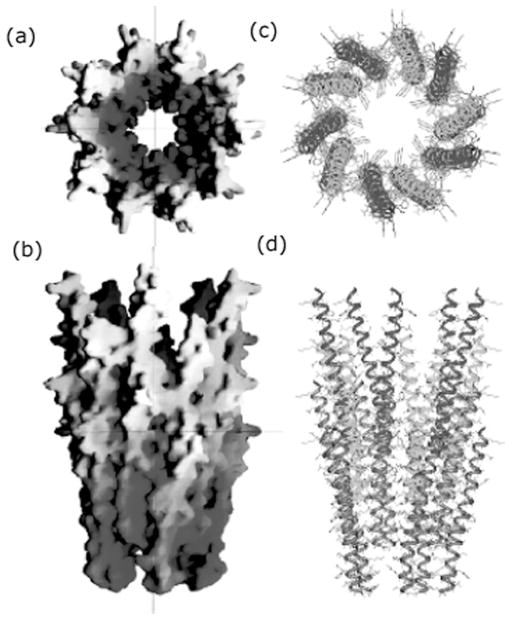

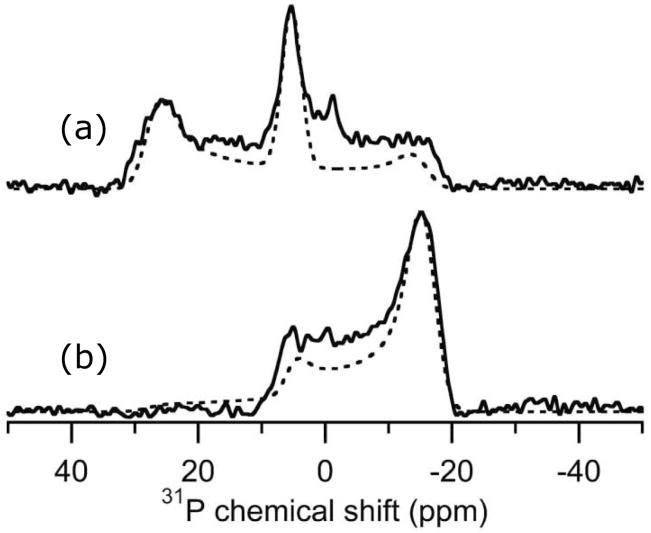

Next, we are concerned with aligned samples. For example, orientation-dependent 15N and 13C solid-state static NMR spectra of [15N]- or [13C]-labeled silk fibroin fibers were observed when the fiber axis was arranged at various angles between 0° and 90° relative to the external magnetic field direction [56,57]. A 1D spectrum convoluted with 1H-15N dipolar coupling and 15N chemical shift interactions has been obtained from a [15N]Gly-collagen fiber with the fiber axis oriented parallel to the external magnetic field [58]. Orientation-dependent spectra of lipid bilayers are discussed below in Section 4.3.2.

1.2.2 Static powder pattern spectra

While static solid-state NMR measurements from a high quality single crystal are the best way of determining accurate CSA tensors, obtaining single crystals is extremely difficult and sometimes impossible for biological systems. In addition, a single crystal study is very time-consuming in spite of some fast approaches to reduce the number of experiments [59]. The three principal values alone, however, are available from the analysis of the powder pattern spectra (see Fig. 2). Following Eq. (19), the observed frequency of spectral lines can be expressed in terms of Euler angles (α, β) which relate the principal axes of the CSA tensor to the laboratory frame. As a result, δ11, δ22 and δ33 can be determined from the peak at δ22 of the divergence of the line-shape function and two edges at δ11 and δ33 of the shoulder [9,31]. More accurately, these parameters can be determined by line-shape analyses of the experimental spectra based on a treatment by Bloembergen and Rowland [60]; discussions about the line-shape analysis can be found in the literature [9,15,31].

It is possible to determine the orientation of a 15N or 13C CSA tensor in the molecular frame by measuring the correlated/convoluted chemical shift spectra with 13C-15N or 15N-1H dipolar interactions. Several studies have reported 15N and 13C CSA tensors of peptides and proteins selectively labeled with these isotopes [61–64]. For example, the orientation of the 15N chemical shift tensor relative to the molecular frame was determined from a polycrystalline L-[1-13C]alanyl-L-[15N]alanine sample using a 13C chemical shift spectrum convoluted with the 13C-15N dipolar coupling interaction. The reported angles are βCN = 106°, αCN = 5° and βNH = −19°, αNH = 12° [65].

1.2.3 Spinning side-band analysis

The free induction decay from a spinning sample having inhomogeneous anisotropic interactions takes the form of a train of rotational spin echoes. The Fourier transform of these rotational spin echoes results in a spectrum with spinning side bands which contain information concerning the CSA. Maricq and Waugh [66] showed that the second (M2) and third (M3) moments [67] of such NMR spectra can be used to obtain the CSA from the side-band intensities. Thus,

| (29) |

| (30) |

Herzfeld and Berger showed that the principal CSA values can be derived from the intensities of a relatively small number of sidebands, based on general integral and series expansions for sideband intensities [68]. The expressions are evaluated for a wide range of shift parameters and the results are commonly used to construct graphical and numerical methods for extracting the principal values of chemical shift tensors from the intensities of just a few spinning sidebands. To accurately measure CSA parameters, Fenzke, et al.[69] developed an alternative approach to determine the principal values of a CSA tensor from MAS sideband intensities, in which one attempts to minimize the mean square deviation between the calculated and experimental sideband intensities. Another approach was proposed for the analysis of MAS NMR spectra which combines nonlinear and linear analytical procedures for fitting sideband spectra [70]. This method is particularly useful for the analysis of spectra with lower S/N ratio or overlapping lines.

The reliability of the determination of the anisotropy and the asymmetry parameter of the chemical shift interaction was calculated using the Cramér-Rao lower bounds [71]. Based on numerous studies, it is realized that CSA tensors can be more accurately determined from a spinning sample experiment than from a static experiment on a powder sample.

1.2.4 CSA recovery under MAS

While MAS averages CSA, a number of multidimensional separation and correlation techniques have been utilized to recover CSA interactions [15]. Magic angle hopping is a 2D technique which utilizes a mechanical device for rotating the sample in discrete 120° jumps, during the 120° jump time interval between the jumps with a “hop” about the magic angle axis, with the proton decoupling switched off during the “hop” period [72]. The CSA is averaged to zero by allowing the magnetization to evolve at three suitable orientations of the sample relative to the magnetic field. The static anisotropic pattern is observed in the detection period, after such an effective isotropic evolution. This technique was further modified by replacing the discrete magic angle hopping technique which requires special flip apparatus with a continuous slow MAS experiment, yielding similar result [73]. The sensitivity of this method (magic angle turning (MAT)) was increased by this modification due to acquisition of the full echo rather than only half of the echo. Alternatively, the switched-angle sample-spinning (SASS) method allows the 13C magnetization to evolve under the sample spinning at an off-magic-angle and under proton decoupling, and then makes measurements at the magic angle [74].

A phase corrected MAT (PHORMAT) technique has been developed to overcome the shortcomings of the previous version of the MAT experiment [75]. An excellent spectrum of methyl-α-D-glucopyranoside free of baseline artifact provided the principal values of 13C CSA with an accuracy comparable to the values obtained from a single crystal study. A complete separation of isotropic and anisotropic chemical shifts was established by a 2D MAS experiment, relying on the fact that the magnetization evolution under the TOSS sequence [76] can be reversed by the application of a “mirror image” sequence [77]. A 2D phase adjusted spinning sideband (PASS) method was developed to separate anisotropic and isotropic chemical shift interactions under MAS using sequences of five π pulses [78,79].

One revolutionary technique, polarization inversion spin exchange at magic angle (PISEMA), that correlates 15N CSA and 1H-15N dipolar coupling greately improves the resolution and sensitivity of separated-local-field (SLF) spectroscopy [61]. The PISEMA sequence was combined with the MAT technique, taking advantages of high-resolution and high-sensitivity of PISEMA and the ability to resolve isotropic resonances using MAT [62]. 1D magic-angle decoupling and magic-angle turning (MADMAT) NMR was also developed by combining the magic-angle rf decoupling in one time period and the MAT pulse sequence in another time period [63]. Application of the 1D dipolar-shift method under MAS was used to determine the 15N CSA and 1H-15N dipolar interaction tensors from a powder sample of a model peptide [64].

Another experiment was introduced to obtain undistorted CSA lineshape under MAS [80]. This utilizes the time dependence of the resonance frequency of an isolated spin under MAS ω (t) [66], which can be written as

| (31) |

Here, Ci(Ω) are coefficients that depend on the molecular orientation relative to the rotor axis Ω at time 0. For a stationary sample, the C1(Ω)+ C2(Ω) term gives rise to the usual CSA pattern. By means of four rotor-synchronized π pulses under fast MAS in a 2D experiment, the anisotropy effects of C1(Ω) and C2(Ω) are reintroduced with equal prefactors, while those of S1(Ω) and S2(Ω) remain equal to zero over a rotor period. This 2D iso-aniso experiment was further developed (and named as RAI, recoupling of anisotropy information) to produce the static chemical shift spectra in the indirect dimension and isotropic chemical shift spectra in the direct dimension [81,82]. This approach decreases the influence of finite pulse length effects in the original sequence by recoupling the CSA over three rotor periods instead of one. Then, it is even possible to use a spinning speed as fast as 10 kHz. Cogwheel (COG) phase-cycled, constant time, and optimized implementations of the CSA recoupling experiment demonstrated that the modifications give reliable, undistorted CSA powder patterns using a standard experimental hardware and methods [83]. The constant time (CT-2DCSA (COG)) variant was shown to give optimum lineshapes of the powder patterns while the optimized (OPT-2DCSA(COG)) version of the experiment maximized the signal-to-noise ratio as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

F1 slices of the 13C resonance of carbonyl site of glycine extracted from the 100.56 MHz 2D spectra for (a) the conventional implementation of the 2DCSA experiment, (b) the 2DCSA(COG) implementation, (c) the OPT-2DCSA(COG) implementation, (d) the CT-2DCSA(COG) implementation, (e) a simulated powder pattern. Reproduced with permission from [83]. Copyright 2006 Elsevier.

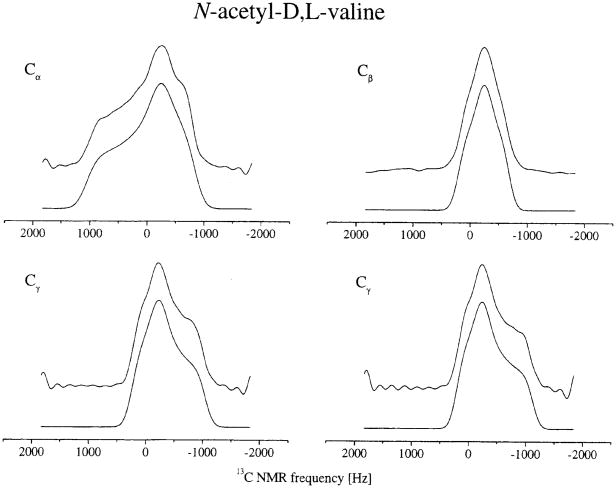

No significant artifacts, with standard rf power levels and spinning speeds between 2.5 and 5 kHz, were observed using the SUPER (separation of undistorted powder patterns by effortless recoupling) approach [84] which utilizes 360° instead of 180° pulses in the above-mentioned iso-aniso 2D MAS experiment [80]. The SUPER method has been applied to samples containing various sp2- and sp3- hybridized carbon sites. A variant of this technique was proposed to recover the CSA by combining a pair of selective and non-selective π pulses to suppress the 13C-13C scalar and dipolar interactions [85]. Another approach was proposed for the recovery of CSA under MAS while retaining a static CSA powder pattern line shape and simultaneously attenuating homonuclear dipole–dipole interactions [86]. This was accomplished by a rotor-synchronized rf pulse sequence with symmetry properties that permit static CSA line shapes to be obtained by a pulse sequence called ROCSA Σrecoupling of chemical shift anisotropyΠ, with the scaling factors of 0.272 for CSA, and approximately 0.05 for homonuclear dipole–dipole interactions. Analysis of the CSA patterns in the Aβ11-15 (a 15-residue peptide fragment in which four amino-acid residues were uniformly 13C and 15N labeled) demonstrated the utility of ROCSA measurements for probing peptide conformations in noncrystalline solids, as illustrated for the Val residue of the peptide in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

13C ROCSA spectra for Val-18 of Aβ11– 25. The C′ spectrum was measured at νR=20 kHz and 9.39 T. The other spectra were measured at νR= 11 kHz and 14.09 T. Upper traces are experimental spectra. Lower traces are best-fit simulations for a one-spin system. Reproduced with permission from [86]. Copyright 2003 American Institute of Physics.

1.2.5 Solution NMR experiments

NMR signals split by CSA in the solid are time-averaged in solution by fast isotropic tumbling motions, yielding narrow spectral lines. Nonetheless, the CSA information is present in the individual isotropic signals through their nuclear spin relaxation times T1 or T2, especially when solution NMR spectra of globular proteins are examined at a high magnetic field when the contribution of the CSA relaxation mechanism becomes dominant as compared to that of the dipole-dipole interaction. Therefore, it is possible to retrieve CSA data from the spin-spin relaxation rates by careful examination of relaxation data available from solution NMR, as will be described in more detail in Section 3.3. For this reason, a prior knowledge of the magnitude of the CSA values in solution is essential to optimize the experimental condition to record high-resolution TROSY spectra for large proteins or protein complexes with a molecular weight of ~100 kDa [16–20].

1.2.6 Quantum chemical calculations

Quantum chemical methods have been used to calculate CSA tensors for nuclei in a variety of molecules. The accuracy of such calculated nuclear shielding constants and the orientations of the principal axes depends strongly on the quantum chemical calculations used, for example semiempircal, ab inito, or DFT (density functional theory) [40,47,50–52,87,88]. These calculations have proved to be very useful for providing insights into the underlying mechanism of nuclear shielding, including the dependence on molecular conformational changes and intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding, even theough such calculations have long remained qualitative for prediction of the experimental data. Currently, more accurate data are available from ab initio Hartree-Fock theory using perturbation methods with the inclusion of the electronic correlation, or DFT theory [87,88]. Studies have shown that these calculations are useful in understanding the variation of CSA tensors from one molecule to another, and one amino acid residue to another in a given protein. Some of these studies are highlighted later in this review.

2. Isotropic chemical shifts

2.1 Referencing chemical shifts

A IUPAC recommendation proposed to delete the factor of 106 in Eq. (3), and to express the numerator in Hz and the denominator in MHz [7,89]. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) in dilute solution in organic solvents such as CDCl3 or 2,2-dimethylsilapentane-5-sulfonic acid (DSS) in aqueous solutions are commonly used as internal reference compounds for reporting 1H and 13C NMR spectra. Without significant differences in chemical shifts between these references, chemical shifts can also be given by “Ξ” which is defined as the resonance frequency in a magnetic field in which TMS has a resonance frequency of 100.0 MHz,

| (32) |

The data, however, must be reported to eight or nine significant figures as shown in Table 1 and therefore it is cumbersome for discussion. Hence, chemical shifts of any nuclei are commonly expressed relative to secondary references by the δ scale as discussed above. It should be taken into account, however, that 13C chemical shifts based on DSS and TMS differ by about 2 ppm, which can cause confusion if not clarified [4].

Table 1.

Alternative secondary references

| Isotope | Recommended secondary references | Alternative secondary references | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference compound | Sample conditions | NMR Frequency Ξ/% | Reference compound | Sample conditions | NMR Frequency Ξ/% | |

| 1H | DSS | Internal | 100.000 000 |

TMSa | Internal | 100.000 000 |

| 2H | DSS | Internal | 15.350 608 |

TMSa | Internal | 15.350 609 |

| 13C | DSS | Internal | 25.144 953 |

TMSa | Internal | 25.145 020 |

| 31P | (CH3O3)PO | Internal | 40.480 864 |

H3PO4 (85%) | External | 40.480 742 |

| 15N | NH3(liquid) | External | 10.132 912 |

CH3NO2 | External | 10.136 767 |

| 15N | [(CH3)4N]I | Internal | 10.133 356 |

|||

| 14N | [(CH3)4N]I | Internal | 7.223 885 |

CH3NO2 | External | 7.226 717 |

Volume fraction 1% in CDCl3

0.075M in DMSO-d6

Reproduced from R. K. Harris, E. D. Becker, S. M. C. de Menezes, R. Goodfellow, F. Granger, Pure Appl Chem. 73 (2001) 1795–1918

In contrast, reporting 13C chemical shifts obtained from high-resolution solid-state NMR is more complicated as compared to solution NMR results based on an internal reference, because referencing for solids is usually done by a substitution method using a secondary reference compound, such as the carboxyl peak of glycine (176.03 ppm from neat TMS) or CH2 carbon of adamantine (29.50 ppm from the high-field doublet from a neat TMS). Chemical shifts with respect to other reference systems such as TMS in a sealed capillary of 1% CDCl3 solution or DSS should be compared with the data after subtracting or adding the correction factors given in Table 2 [90]. The following conversion scheme has also been proposed [91]:

| (33) |

Table 2.

Correction of 13C chemical shifts primarily referenced to glycine or adamatane (italic) and then secondarily referenced to TMS or DSS (ppm)

| Standard reference | Primary reference (with reference to the respective standard reference) | Chemical-shift correctiona | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycine C=O | Adamantane Low field | Adamantane High field | ||

| TMS neat | 176.03 | 38.04 | 29.00 | 0 |

| TMS neat | 38.5 | 29.5 | −0.5 | |

| TMS 1% CDCl3 | 37.8 | 28.8 | +0.2 | |

| DSS solid | 38.1 | 29.1 | −0.1 | |

| 5% D2O | 40.4 | 31. 4 | −2.4 | |

| 1% D2O | 40.6 | 31.5 | −2.5 | |

Chemical shifts were calibrated by the peak position expressed by italic as the primary reference. Chemical shift correction should be made to compare the data based on different reference system to each other, after adding or subtracting “chemical shift correction”. Reproduced with permission from [90].

In order to retrieve any meaningful results from experimental data, a careful check on the reference system is also essential. Here we have dropped the label ‘iso’ on δ when isotropic terms alone are concerned.

2. 2 Isotropic chemical shifts

2.2.1 13C chemical shifts

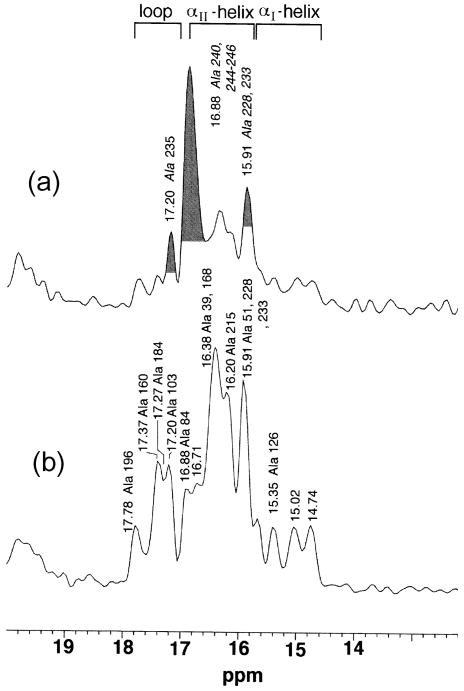

In the solid-state, displacements of 13C NMR peaks as large as 8 ppm are noticed between different conformations in polysaccharides, polypeptides, proteins and several types of ionophores [22–24]. Even though the magnitude of these displacements is still small compared with the total chemical shift spread of 200 ppm, it is sufficiently large to provide a convenient intrinsic probe for conformational characterization. In particular, 13C chemical shifts of the backbone Cα and C=O, as well as the side-chain Cβ signals, are significantly displaced for a variety of amino acid residues in polypeptides, depending on their local conformation such as α-helix, β-sheet, 31 helix, silk I, collagen type triple helix, random coil, etc [22–24,92–101]: the Cα and C=O 13C chemical shifts of all residues in an α-helix are displaced downfield by 3.5–8.0 ppm with respect to those of a (antiparallel) β-sheet form, while the Cβ shifts in an α-helix are displaced upfield by 3.4–5.2 ppm with respect to those of a β-sheet, as summarized in Table 3 (referenced to neat TMS, through the chemical shift of C=O carbonyl peak of Gly). The transferability of these parameters for particular residues, from simple model peptides to more complicated proteins, has proved to be an excellent diagnostic means of determining local conformations of specific amino acid residues in proteins such as silk fibroin [102, 103], collagen [104–106] and transmembrane peptides [107]. This is a consequence of a dominant contribution from the paramagnetic term of the shielding constant in Eq. (21).

Table 3.

13C chemical shifts characteristic of the α-helix, β-sheet and random coil forms (ppm from TMS)

| Amino acid Residues in Polypeptides | Cα |

Cβ |

C=O |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-helix | β-sheet | random coilb | Δa | α-helix | β-sheet | random coilb | Δa | α-helix | β-sheet | random coilb | Δa | |

| Ala | 52.4 | 48.2 | 51.1 | 4.2 | 14.9 | 19.9 | 15.7 | −5.0 | 176.4 | 171.8 | 176.1 | 4.6 |

| 52.3 | 48.7 | 3.6 | 14.8 | 20.0 | −5.2 | 176.2 | 171.6 | 4.6 | ||||

| 52.8 | 49.3 | 3.5 | 15.5 | 20.3 | −4.8 | 176.8 | 172.2 | 4.6 | ||||

| Leu | 55.7 | 50.5 | 55.2 | 5.2 | 39.5 | 43.3 | 39.7 | −3.8 (4.1) | 175.7 | 170.5 | 175.7 | 5.2 |

| 55.8 | 51.2 | 4.6 | 43.7c | 39.6 | 175.8 | 171.3 | 4.5 | |||||

| Val | 65.5 | 58.4 | 61.2 | 7.1 | 28.7 | 32.4 | 31.7 | −3.7 | 174.9 | 171.8 | 174.4 | 3.1 |

| 58.2 | 32.4 | 171.5 | ||||||||||

| Ile | 63.9 | 57.8 | 61.1 | 6.1 | 34.8 | 39.4 | 37.1 | −4.6 | 174.9 | 172.7 | 175.8 | 2.2 |

| 57.1 | 33.1 | 171.0 | ||||||||||

| Glu(OBzl) | 56.4 | 51.2 | 5.2 | 25.6 | 29.0 | −3.4 | 175.6 | 171.0 | 4.6 | |||

| 56.8 | 51.1 | 5.7 | 25.9 | 29.7 | −3.8 | 175.4 | 172.2 | 3.2 | ||||

| Asp(OPBzl) | 53.4 | 49.2 | 4.2 | 33.8 | 38.1 | −4.3 | 174.9 | 169.8 | 5.1 | |||

| 53.6d | 34.2d | 174.9 | ||||||||||

| Lyse | 57.4 | 29.9 | 176.5 | |||||||||

| Lys (Z) | 57.6 | 51.4 | 6.2 | 29.3 | 28.5 | −0.8 | 175.7 | 170.4 | 5.3 | |||

| Arge | 57.1 | 28.9 | 176.8 | |||||||||

| Phe | 61.3 | 53.2 | 8.1 | 35.0 | 39.3 | −4.3 | 175.2 | 169.0 | 6.2 | |||

| Met | 57.2 | 52.2 | 5.0 | 30.2 | 34.8 | −4.6 | 175.1 | 170.6 | 4.5 | |||

| Gly | 43.2 | 168.4 | ||||||||||

| 44.3 | 169.2 | |||||||||||

| 171.6f | 168.5 | 3.1 | ||||||||||

Difference in the 13C chemical shifts of the α-helix form relative to those of the β-sheet form.

in CF3COOH solution. A few drops of H2SO4 were added in the cases of (Ile)n and (Leu)n

This assignment should be reversed.

Erroneously assigned from the left-handed α-helix.

Data taken from the data of salt-induced α-helix in neutral aqueous solution

Averaged values from the data of polypeptides containing 13C-labeled glycine residues.

Reproduced with permission from [24]

The 13C chemical shift peaks of polypeptides, involved in a random coil form in CF3COOH or aqueous solution, always appear between the peaks of α-helix and β-sheet conformations, as a consequence of time-averaging of the shifts of the allowed conformations. In some instances, however, the 13C chemical shifts of the α-helix are very close to those of a random coil as encountered for Ala and Leu residues (Table 3). This is also the case for a variety of membrane proteins, for instance, [3-13C]Ala-labeled bacteriorhodopsin (bR) in which an α-helical Ala Cβ from the flexible C-terminal region resonates at the lowest boundary position accidentally overlapped at the frequency typical of a random coil [24,108]. Even in such cases, a distinction between α-helix and random coil peaks can be made, by taking into account that the signal from the α-helix under consideration can be recorded only by a CPMAS experiment in the presence of persistent C-H dipolar interactions, but the peak from random coil can be obtained by either solution NMR or by DD (direct-detection or dipolar-decoupled, without cross-polarization) MAS because of averaged such dipolar interactions. Even though the antiparallel structure is known as the major form in the β-sheet form, the parallel β-sheet form [109,110] plays an important role in the secondary structure of amyloid peptides [111] and silk fibroin from S.c.ricini [112]. In reflecting the presence of different types of hydrogen bonding between the two types of β-sheet forms, more wide spread of Ala Cβ 13C chemical shifts (16.1–22.8 ppm, with reference to a neat TMS) in N- and C-terminal Ala residues in a parallel β-sheet (Ala)3 and (Ala)4, as confirmed by X-ray diffraction studies, turned out to be an excellent means to distinguish the types of both conformations as compared with those of an antiparallel form (18.9–21.1 ppm) [112]. Consequently, the 13C chemical shifts as measured in the solid-state with reference to those from model polypeptides in Table 3 and parallel β-sheet form turned out to be a very valuable means as intrinsic probes to determine the secondary structure of peptides and proteins, irrespective of neighboring amino acid residues.

Further, it is interesting to note that carbonyl 13C chemical shifts (C′) in peptides and proteins are also related to the nature of participating hydrogen bonds. In particular, it was empirically shown that the observed isotropic 13C′ chemical shifts in Gly, Ala, Leu, Val and Asp residues move linearly downfield with a decrease in the hydrogen-bonding length RN…O, according to Eq. (34) [113–115],

| (34) |

where a and b are 206.0 (ppm) and 12.4 (ppm/Å) for Gly residue, 237.5 (ppm) and 21.7 (ppm/Å) for Ala residue, 215.4 (ppm) and 14.2(ppm/Å) for Val residue, 202.2 (ppm) and 10.0 (ppm/Å) for Leu residue, and 199.0 (ppm) and 9.6 (ppm/Å), respectively. Alternatively, the RN…O values of some polypeptides in the crystalline state can be evaluated by these relations from the observed amide C′ chemical shifts.

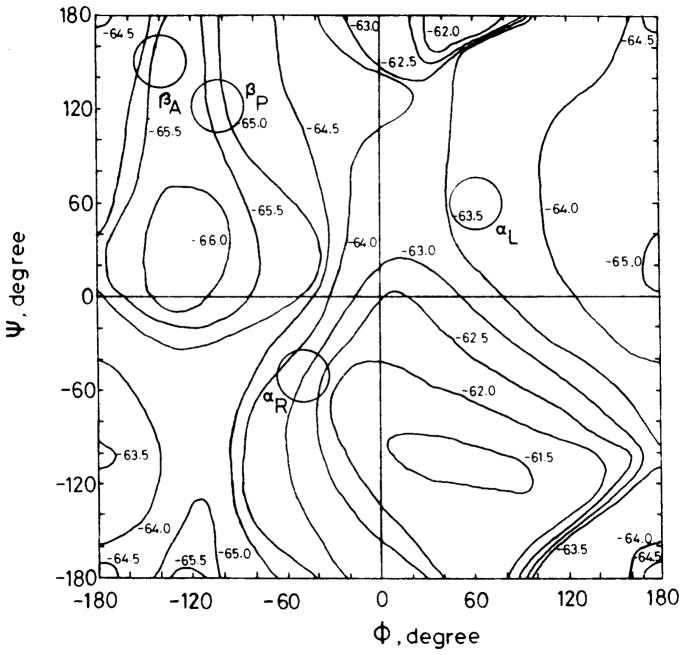

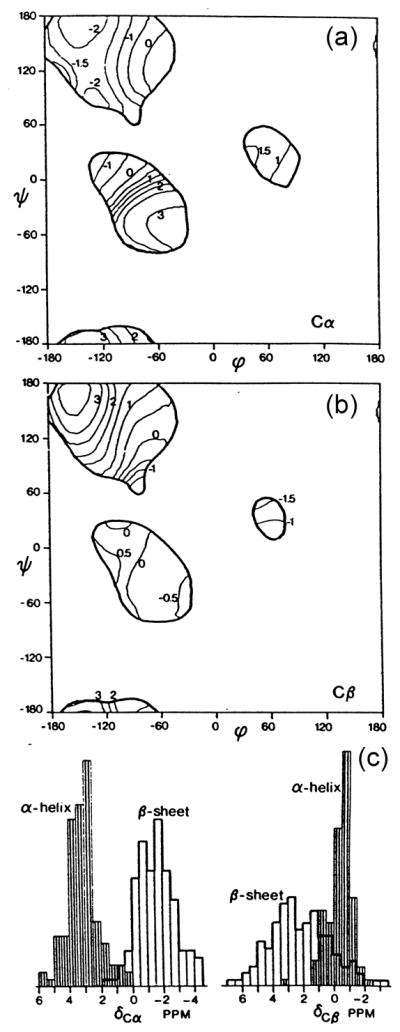

The above-mentioned conformation-depence of 13C chemical shifts in polypeptides or proteins has been explained theoretically by calculation of the 13C shielding constants of Ala fragment (N-acetyl-N′-methyl-L-alanine amide; Ac-L-Ala-NHMe) as a function of the torsion angles (dihedral angles) (φ, ψ) by means of the FPT-INDO method [41]. The 13C chemical shift for the Ala Cβ carbon, for instance, in any specified conformation can be found from the calculated contour map of the shielding constant as illustrated in Fig. 5 [41]. These calculations verified that 13C chemical shifts of Ala residues in polypeptides and proteins vary with conformation and can be utilized as convenient probes for predicting conformation. However, for the interpretation of Cα and C=O 13C chemical shifts, however, it turned out to be essential to include hydrogen bonds at N-H and C=O in addition to the effects of the torsion angles, although the Cβ chemical shift is not affected by such hydrogen bonds. Instead of this fragment approach, calculation of Cα, Cβ and C=O 13C chemical shifts of (Gly)n, (Ala)n, and (β-benzyl-L-Asp)n, have been made which take tight-binding MO theory suitable for treating infinite molecular chain into account of the infinite chain-length of peptides including appropriate intramolecular hydrogen bond network and these are consistent with the experimental data [116,117]. Consistent results were further obtained by more elaborate calculations of 13C chemical shifts for Ac-L-Ala-NHMe and Ac-Gly-NHMe on the basis of ab initio MO approaches [43,44,117,118].

Fig 5.

The calculated 13C chemical shift (shielding constant) map of the Cβ carbon of N-acetyl-N′-methyl-L-alanine amide obtained by using the FPT-INDO method. The chemical shielding constants were calculated at 15° intervals for the torsion angles (φ, ψ). Reproduced with permission from [41]. Copyright 1984 American Chemical Society.

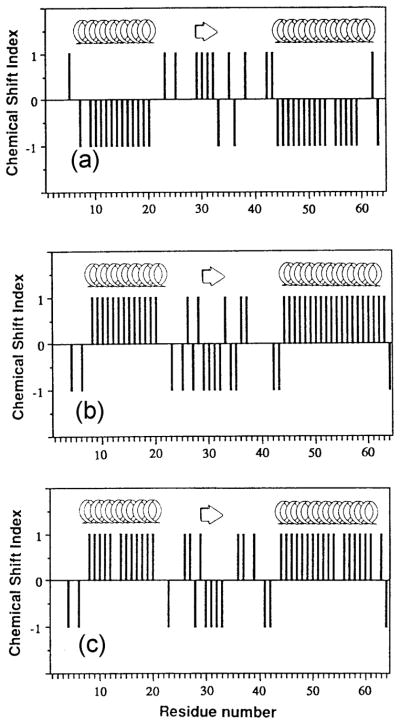

Average 13C chemical shifts obtained by multidimensional solution NMR experiments for Cα and C=O carbons of all 20 amino acid residues taking α-helix, β-sheet and random coil forms have been reported [25,120]. Both the 13C resonances experience downfield shifts in the α-helix and upfield shifts in the β-sheet forms with respect to those in a random coil. Solution NMR structural studies have extended this approach to formulate a chemical shift index (CSI) to identify the secondary structure of proteins [28,121,122]. This method can be thought of as a filtration procedure to separate out spurious chemical shift signals, by assigning an index value of +1, 0, or −1 for the α-helix, random coil and β-sheet structures, respectively. The CSI values which are graphically represented against the amino acid sequence were originally developed for the analysis of Hα signals and extended to include 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13C=O chemical shifts to identify and locate the secondary structure of proteins without recourse to NOE measurements by utilizing these four independent chemical shift measurements [122]. For example, the secondary structure of the first 65 residues of interleukin 4 experimentally determined by the CSI values are consistent with the secondary structure determined by X-ray and NOE data, as depicted by the arrows (β-strand) and coils (helices) in Fig. 6 [28].

Fig. 6.

Chemical shift index plotted for the first 65 residues of interleukin 4 using assignments supplied by Powers et al. [123]. (a) Hα, (b) Cα, and (c) carbonyl resonances. Reproduced with permission from [28]. Copyright 1994 Elsevier.

13C chemical shifts of the Cα and Cβ carbons of individual residues can be used to obtain the corresponding torsion angles φ and ψ of the peptide unit, whose values available from high-resolution x-ray diffraction studies in which their 3D structures have been resolved at 1.0–2.2 Å [25]. Average secondary shifts of (Δ (φ, ψ)) as a function of the torsion angles (φ, ψ) were calculated by convolution of each of the deviation from random coil chemical shift as a secondary shift of residue k, δ (φk, ψk), with a Gaussian function

| (35) |

Plots of these functions for Cα and Cβ signals are illustrated in Fig. 7 (A and B, respectively), together with histograms of secondary shift distribution in α-helix and β-sheet forms (C). This is consistent with the data obtained from polypeptides in the solid-state as summarized in Table 3 and in Fig. 5. An extensive database of Cα and Cβ chemical shifts of proteins in solution has been generated, for which high-resolution crystal structures exist and they have been shown to be essentially identical to the solution structures [124]. The effects of backbone dihedral angles, side-chain dihedral angle χ1 and hydrogen bonding on the Cα and Cβ chemical shifts were analyzed. These chemical shift data, together with those of 15N and 1H chemical shifts, are currently utilized as most important structural restraints for 3D construction as discussed in Section 4. 1.

Fig. 7.

Contour plots of the average secondary shift Δ(φ, ψ) of (a) Cα and (b) Cβ resonances and histogram (c) of secondary shift distributionin α-helix and β-sheet form. Reproduced with permission from [25]. Copyright 1991 American Chemical Society.

2.2.2 15N chemical shifts

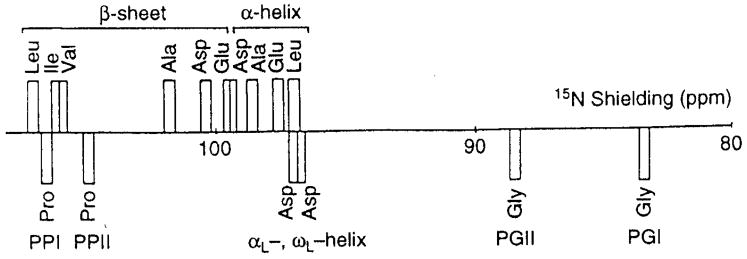

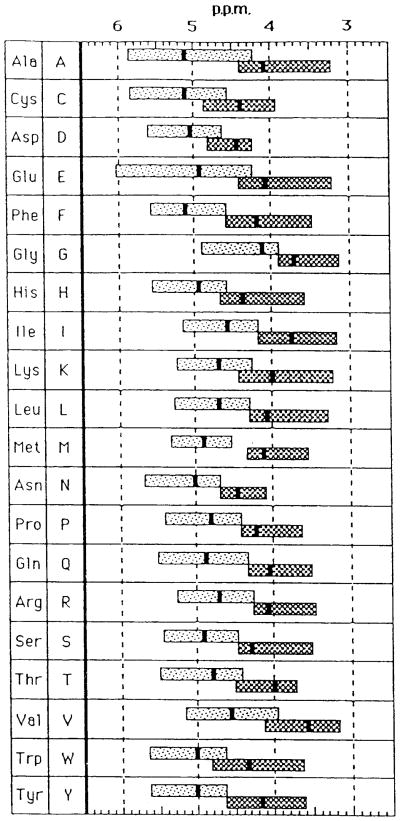

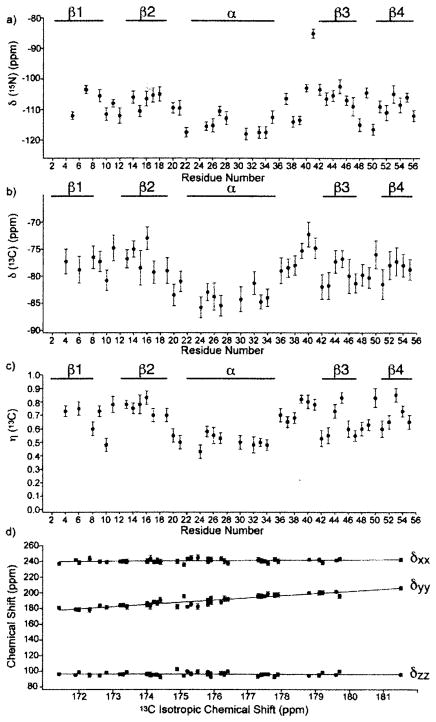

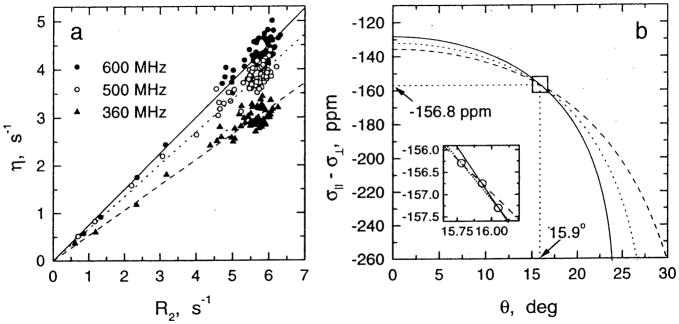

It was also anticipated that amide-15N chemical shifts of polypeptides and proteins would also be sensitive to their secondary structures. In studies of 15N-labeled homo- and copolypeptides in the solid-state [30, 125–127], the conformation-dependency of 15N chemical shifts is found be not so simple as compared to the above-mentioned 13C chemical shifts, because 15N chemical shifts depend mainly on the conformation and side-chain structure of an individual amino acid residue [30]. In fact, the amide-15N signals of α-helial homopolypeptides (97.0–99.2 ppm) are found at a higher field than that of the β-sheet conformation (99.5–107.0 ppm), as demonstrated in Fig. 8, consistent with the isotropic and δ22 component of the 15N shielding map calculated for poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate) [128]. The δ22 component of the 15N shielding tensor, which lies perpendicular to the H-N-C plane as illustrated in Fig. 10 for the amide-15N nuclei, can be utilized as a good parameter for distinguishing α-helix and β-sheet conformations. In Fig. 8, 15N chemical shifts of other conformations including forms I and II of (Pro)n [PP] and (Gly)n [PG], αL (left-handed α-helix) and ωL (omega) helix are also included. It is also noted that the 15N chemical shifts of the β-sheet form of Leu, Val or Ile residues with alkyl side-chains appear at a lower field than that of an Ala residue, while the 15N chemical shifts of the β-sheet forms of Asp(OBzl), Glu(OBzl) or Glu(OMe) residues appear at higher fields than that of an Ala residue. In fact, 15N chemical shifts are strongly influenced by the side-chain bulkiness of residue i-1 affecting the backbone 15N shift of the ith residue [30].

Fig. 8.

The diagram of the observed isotropic 15N chemical shifts of some homopolypeptides (X)n with various conformations [α-helix, β-sheet, αL-helix, ωL-helix, (Gly)n I (PGI), (Gly)n II (PGII), (Pro)n I (PPI) and (Pro)n II (PPII) forms]. Reproduced with permission from [30]. Copyright 1993 Elsevier.

Fig. 10.

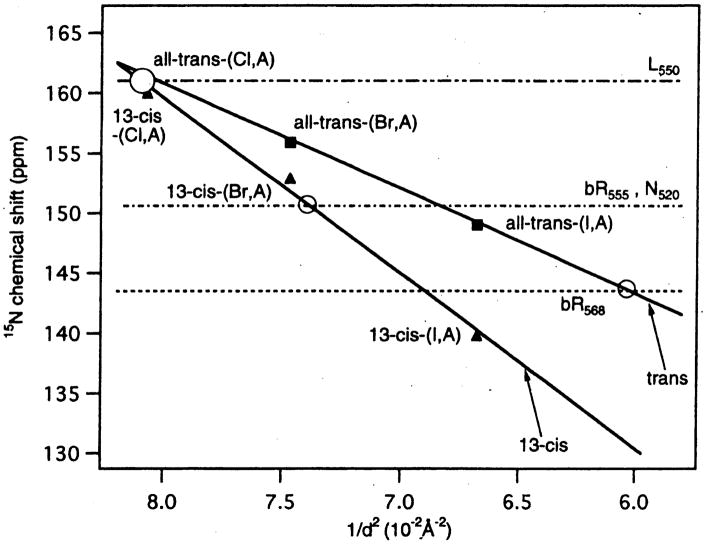

Correlation between the 15N chemical shift for protonated 6-s-trans-retinal Schiff bases (SB) and the counterion strength measurd by 1/d2, where d is the center-center distance between the SB nitrogen and the counterion. Reproduced with permission from [144]. Copyright 1997 American Chemical Society.

In a similar manner, a 3–4 ppm difference in amide-15N chemical shift was observed between the α-helix and β-sheet residues from various globular proteins in aqueous solution [118]. In relation to the neighboring effect as described above, an empirical correlation between 15N chemical shifts, in BPTI and apamin, and the torsion angle of the preceding residue ψi−1 was proposed for the β-sheet residues [129]. Empirical correlation between 15N chemical shifts and the torsion angles φi and ψi−1 was searched for a variety of proteins with known 3D structures [130]: on average, the rms error between experiment and prediction is about 3.5 ppm, although results for Thr, Val and Ile residues are worse (~4.8 ppm). Ab initio calculations were performed for several peptide fragments in order to estimate the contributions to 15N chemical shifts of peptide residues such as the torsion angles (φi−1, ψi−1 φi, ψi and χ1) and hydrogen bond [43,131]. It was shown that the two backbone torsion angles closest to the peptide group (ψi−1 and φi) have the largest effects up to 20 ppm on 15N chemical sifts. The adjacent (preceding) torsion angles φi−1 and ψi have a smaller contribution up to 8 ppm. Different side chain conformations produced chemical shift variations of only 4 ppm [131].

Further, it should be taken into account that 15N chemical shifts are very sensitive to the nature of hydrogen bonding: the 15N signal of a proton donor (N-H) is displaced downfield by about 15 ppm, while the 15N shift of a proton acceptor (tertiary nitrogen atom) is shifted upfield by about 20 ppm [132–136]. Therefore, displacement of 15N chemical shifts arising from hydrogen bonds may surpass the effect due to the above-mentioned conformational changes. In addition to the isotropic 15N chemical shifts, the three principal tensor components were measured for Gly residue in a variety of peptides with a terminal Boc group in order to clarify the relationship between the 15N shifts and RN..O distances: the isotropic 15N chemical shifts (δiso of the glycine residues move downfield with a decrease of hydrogen bond lengths (RN…O) between the nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the amide groups, and that the pricipal value of δ33 moves linearly downfield with a decrease of RN…O. There is no relationship, however, between the principal value of σ11 or σ12 and RN…O, although the decrease of the N-H bond length (RN-H) leads to a linear increase in the 15N chemical shift value [137,138]. Nevertheless, Gly N-H 15N chemical shifts of collagen (Gly-Xaa-Yaa repeating units) and its model polypeptides [(Pro-Ala-Gly)n or (Pro-Pro-Gly)10] were found to be very sensitive probes for locating the interchain (Gly)N-H..O=C (Xaa or Pro) hydrogen bond which is believed to be essential for the stabilization of the coiled-coil triple-helix conformation [139]. In particular, the 15N peak of the Gly N-H group and the high-field (low-frequency) shoulder peak of Pro nitrogen signals in (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 are shifted downfield (4.9 ppm and 6.8 ppm, respectively) with increasing relative humidity by forming N-H … O = C hydrogen bonds, while the corresponding peaks for collagen and (Pro-Ala-Gly)n are unchanged and close to the 15N chemical shift of (Pro-Pro-Gly)10 in the hydrated state. For establishment of the above-mentioned relationship between the 15N chemical shifts and RN..O distances, it is more preferable to use the tensor component δ33 (approximately, parallel to the C-N bond) (see Fig. 9) rather than the isotropic peak [140]. In addition, the N–H bond lengths determined from the N–H dipolar interaction, when the amplitude of a thermal vibration of N–H moiety is significantly enhanced as encountered for weakly hydrogen bonded systems. This means that special care should be exercised when one uses the NMR-derived N–H distances involved in different types of hydrogen bonded systems as parameters for characterizing hydrogen bonded systems.

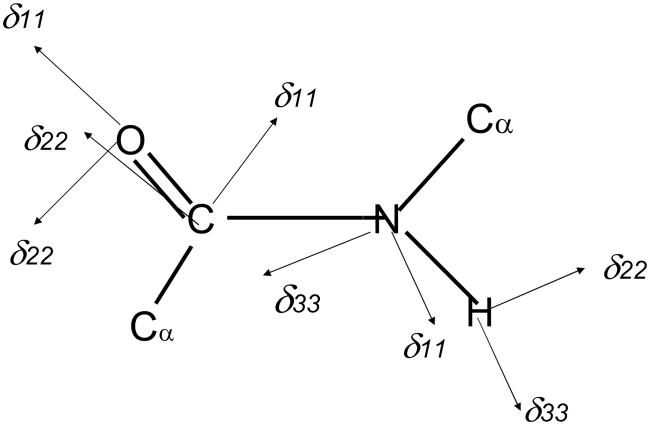

Fig. 9.

Orientations of the principal axes for the 13C, 17O, 15N and 1H CSA tensors for an amide fragment. The most shielded component δ33 for the 13C and 17O tensors is located perpendicular to the peptide plane. The δ22 and δ11 components for the 15N and 1H Tensors, respectively, are also located perpendicular to the peptide plane.

Naturally, the 15N chemical shift is also strongly affected by electrostatic interactions such as effects of electronic charge or counter ion in the vicinity of the nitrogen atom under consideration [135,136]. Thus, the 15N chemical shift of the Schiff base nitrogen in retinylidenes bacteriorhodopsin can be used to identification and detailed characterization of individual photo intermediates [141–145]. The frequencies of the maximum visible absorbance and the 15N chemical shifts of the 13-cis and all trans retinylidene compounds are found to be linearly related to the strength of the protonated Schiff base (pSB)-counterion (CI) interaction as measured by (1/d2), where d is the center-to-center distance between the pSB and the CI, as illustrated in Fig. 10 [143]. With these calibrations, d = 4.0, 3.9, 3.7, 3.6 and 3.8 Å (±0.3Å) distances were estimated for the J625, K590, L550, N520 and bR555 states for 13-cis-compounds of bR, respectively. These distances are comparable with similarly determined values of about 4.16 Å ± 0.03 Å and 4.66 Å ± 0.04 Å for the all-trans bR568 and O640 states, respectively. The effective SB counter ion distance in regenerated bovine rhodopsin expressed by using suspension cultures of HEK293S cells was estimated by means of 15N chemical shift consideration using the empirical relationship as shown in Fig. 10 [146].

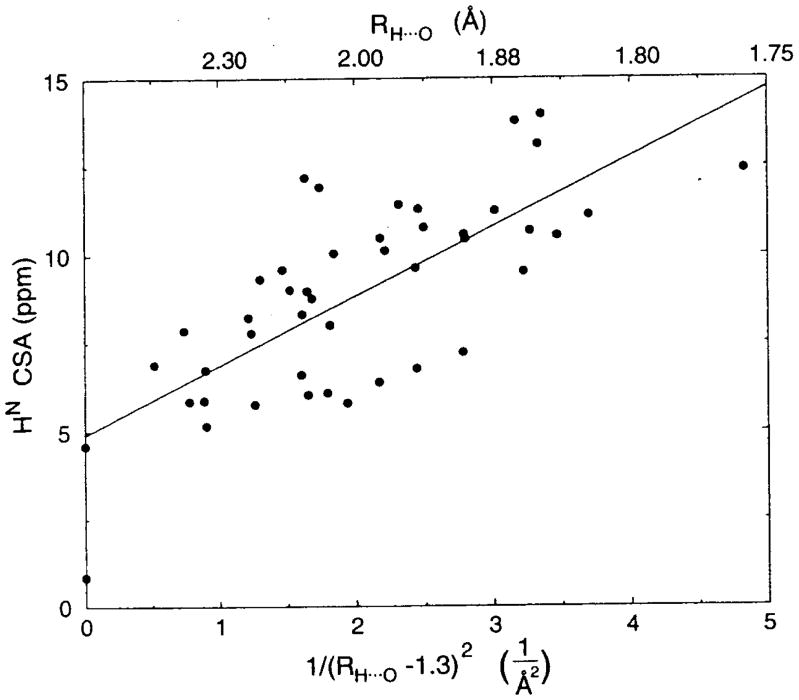

2.2.3 1H chemical shifts

Conformation-dependent 1H chemical shifts, if any, can be caused by the last term in Eq. (21), consisting of neighboring group effects such as magnetic anisotropy, hydrogen bonding, electric field effects, etc. An attempt to evaluate such effects from protein data of known 3D structures showed that Hα protons in the β-sheet regions experience downfield secondary shifts, whereas Hα protons in α-helix regions experience upfield secondary shifts with respect to those of the random coil form. Correlations between the chemical shifts of amide and Cα protons and the length of hydrogen bonds formed by these groups have been made [119,147–152]. The existence of such close correlations between 1H chemical shifts and local secondary structure has been recognized for a variety of proteins of known 3D structures as demonstrated in Fig. 11 [118]. Semi-empirical quantum chemical calculations have been made in attempts to evaluate the contribution of the magnetic anisotropy and electric field effects besides the diamagnetic shielding to 1H chemical shifts of α-helical polypeptide (initially for (Ala)n) and the calculated chemical shifts agree fairly well with the observed values [150]. An empirical analysis of proton chemical shifts referenced to the chemical shift values in random coil protein from a variety of proteins of known structure [151–155] was made to decompose the last term in Eq. (21) into the following contributions:

| (36) |

where the individual terms are contributions from aromatic ring currents, magnetic anisotropy effects from the peptide groups, electric fields from distant polar groups which can polarize the C-H bond, and solvent effects, respectively. The term for the ring current contributions in [155] is

Fig. 11.

Distribution of α-proton chemical shifts in helices and β-strands. The black vertical bar indicates the median chemical shift. Reproduced with permission from [26]. Copyright 1991 Elsevier.

| (37) |

where r is the vector from the observed proton to the aromatic ring, G(r) is a geometric factor, and i and B are constants [156]. The magnetic anisotropy contribution is given by [157]

| (38) |

where L0 is the Avogadro constant, R is the distance from the proton to the amide group which has the magnetic anisotropy Δχ = −5.1 ±0.6 × 10−6erg/(G2mol) (formamide) [158]. The term for the electrostatic contribution is

| (39) |

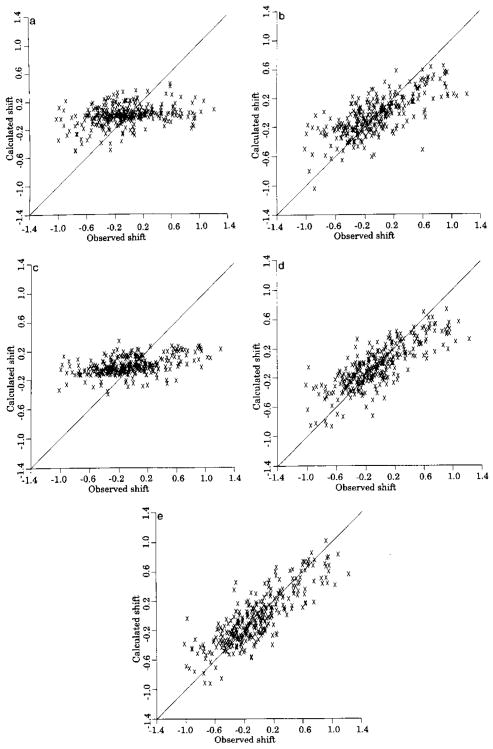

based on the charge model from the CHARMM (version 19) parameters. The parameter fitting of chemical shifts for 5678 protons bonded to carbon into these classical contributions yielded a linear correlation coefficient of 0.88 between calculated and observed structural shifts, with a root mean square error of 0.23 ppm: contributions from the peptide group are especially noticeable for protons at the Cα, although predictions for protons bonded to nitrogen are much worse [152]. Various models for calculating the above-mentioned contributions have been compared [159] and also their relative proportions as illustrated in Fig. 12. The success of such an empirical treatment of 1H chemical shifts of a variety of proteins from the database is promising and further extends to the base of chemical shift restraints for revealing unknown 3D structures of proteins.

Fig. 12.

Comparison of calculated and observed Hα secondary structure shifts. (a) ring current only, (b) magnetic anisotropy only, (c) electric field only, (d) ring current plus magnetic anisotropy, (e) using all three. Values for ubiquitin, turkey ovomucoid third domain, human lysozyme and BTPI are plotted. Reproduced with permission from [159]. Copyright 1991 Elsevier.

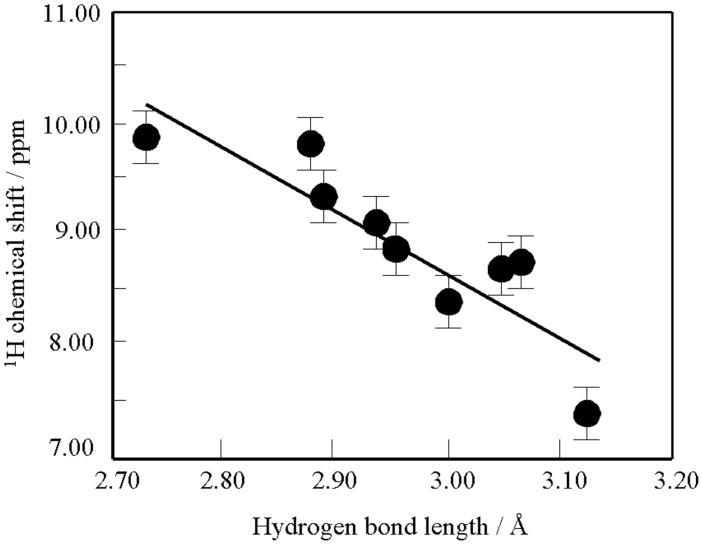

As compared with 13C and 15N NMR spectra, recording 1H NMR spectra of polypeptides and proteins in the solid-state is not an easy task because of the large line broadening caused by dipolar interactions among dense 1H spins. Nevertheless, it was shown that Hα 1H NMR signals of the β-sheet form of (Ala)n and (Leu)n resonate downfield as compared to their signals from the α-helical form as recorded by a combined rotational and multipulse spectroscopy (CRAMPS) method [160,161], consistent with the data from proteins in aqueous solution. Well-resolved N-H proton signals in solid-state are observed either by CRAMPS of 15N-labeled polypeptides [162] or high field/fast MAS measurements [163–165], in order to avoid 14N-1H dipolar splitting caused by the effect of the 14N quadrupole coupling [166]. The measured 1H chemical shift values (δiso) of hydrogen-bonded Gly amide-protons of Gly-containing peptides and polyglycines in the solid-state have been plotted against the hydrogen-bond lengths between amide nitrogen and oxygen atoms (RN…O) determined by X-ray diffraction studies, as illustrated in Fig. 13 [164]. The bars indicate the experimental errors in the spectra. It was found that as RN…O is decreased from 3.12 to 2.72 Å, the amide-1H chemical shift moves downfield by 2.46 ppm from 7.76 to 9.04 ppm. Well-resolved 1H NMR signals including those of amide-NHs were observed for antiparallel and parallel alanine tripeptide (Ala)3 by high-field (930 MHz) MAS (20 kHz) NMR [165]. In particular, amide-NH and NH3+ 1H NMR signals of parallel (Ala)3 were well resolved at 7.5 and 8.9 ppm, respectively, whereas amide-NH and NH3+ signals of antiparallel (Ala)3 resonated at the same frequency (9.5 ppm) which is at lower field than that of the parallel peptide. In a similar manner, amide-15NH signals of antiparallel (Ala)3 resonate at a lower field by 2 to 5 ppm than those of parallel (Ala)3, although the 15NH3+ signal of the former resonates at the peak-position between the two 15N peaks of the latter. These findings based on the 1H and 15N hydrogen bond shifts are consistent with the relative hydrogen bond lengths of inter-strand N-H..O=C bonds as evaluated by x-ray diffraction studies, and are also consistent with DFT calculations for antiparallel and parallel (Ala)3 [165].

Fig. 13.

Plots of the observed 1H chemical shift values (δ) of hydrogen-bonded Gly amide protons of Gly-containing peptides and polyglycines in the solid against the hydrogen bond lengths between amide nitrogen and oxygen atoms (RN…O). Reproduced with permission from [164]. Copyright 2002 Elsevier.

The 1H chemical shielding calculations of hydrogen-bonded Gly amide-protons of two hydrogen-bonded GlyGly molecules have been made using the Gaussian 96 HF program with ab initio 6-31G** basis set by changes of RN…O from 3.5 to 2.6 Å as referred to its crystal structure determined by X-ray diffraction. The calculated chemical shifts move to downfield by 2.5 ppm from 6.9 to 9.4 ppm as RN…O is decreased from 3.30 to 2.72 Å [167].

2.2.4 Chemical shifts can provide torsion angles

Incorporation of both 1H and 13C chemical shift as additional restraints into the refinement of protein structures using the simulated annealing protocol with NOE and J coupling data has been achieved [168,169]. An approach to obtain the most probable φ and ψ angles from multidimensional hypersurface correlations of backbone chemical shifts (13Cα, 13Cβ, 1Hα, 1HN and 15N) of a given residue with its backbone torsion angles was proposed [170]. It was claimed that this information considerably improves the structural quality when used for cases where only a very small number of NOE restraints is available. Indeed, the use of chemical shifts is now recognized as important tool in understanding, generating or refining macromolecular structures: chemical shift refinement options are now available in the simulated annealing protocols, AMBER, XPLOR, and CNS [171]. To this end, a computer program (SHIFTY) was developed to accurately and automatically predict the 1H and 13C chemical shifts of unassigned proteins on the basis of sequential homology of proteins against the database from BioMagResBank [172].

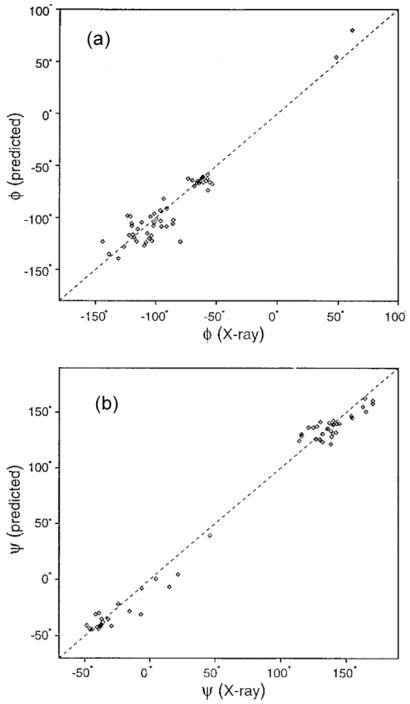

A hybrid approach, [called TALOS (Torsion Angle Likelihood Obtaiend from Shifts and sequence similarity), http://spin.nidak.nih.ov/bax], which searches a database for triplets of adjacent residues with secondary chemical shifts and sequence similarity, in order to provide the best match to the query triplet of interest to predict the most likely backbone angles for a given residue of unknown structure [173]. For each query triplet of consecutive residues, the similarity to a triplet with center-residue j in the database is evaluated by computing a similarity factor, S(i, j) given by:

| (40) |

and the value of S(i,j) is evaluated for all triplets j in the database. Δδ denotes the secondary shifts of the 13Cα, 13Cβ, 13C′, 1Hα and 15N nuclei. Using the empirical weighting factors k0n through k5n values and the residue similarity factors ΔResType, the values of S(i,j) typically range from 5 to 600. As demonstrated in Fig. 14 for comparison of the torsion angles between predicted and observed values in the crystal structure, it appears that the accuracy of the TALOS prediction exceeds that of even some of the best solution structures calculated on the basis of NOEs and J coupling [173]. Alternatively, a computer program (SHIFTX, http://redpoll.pharmacy.ualberta.ca) uses a hybrid predictive approach that employs precalculated, empirically derived chemical shift hypersurfaces in combination with classical or semi-classical equations (for ring current, electric field, hydrogen bond and solvent effects) to calculate 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shifts from atomic coordinates [174]. Data mining techniques were used to extract the largest pairwise contributor (from a list of ~20 derived geometric, sequential and structural parameters) to generate the necessary hypersurfaces which capture dihedral angle, sidechain orientation, secondary structure and nearest neighbor effects. The program was able to attain a correlation coefficient (r) between observed and calculated shifts of 0.911 (1Hα), 0.980 (13Cα), 0.996 (13Cβ), 0.863(13CO), 0.909 (15N), 0.741 (1HN), and 0.907 (sidechain 1H) with RMS errors of 0.23, 0.98, 1.10, 1.16,2.43, 0.49 and 0.30 ppm, respectively. A TALOS-like database searching procedure, which utilizes both the protein sequence and the structural homology, was used after the inclusion of the nearest neighbor, ring current, and hydrogen bond effects to predict the backbone 15N, 1HN, 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13C′ chemical shifts for a protein of known structure, as a computer program SPARTA (Shift Prediction from Analogy in Residue type and Torsion angle) [175]. The predicted and experimental shifts were shown with a standard deviation of 2.52, 0.51, 0.27, 0.98, 1.07 and 1.08 ppm for 15N, 1HN, 1Hα, 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13C′, respectively.

Fig. 14.

Plots of the backbone angles (a) φ, and (b) ψ predicted by TALOS, versus those observed in the crystal structure for ubiquitin. Reproduced with permission from [173]. Copyright 1999 Springer.

The following three computer packages that are currently available on the internet are useful for protein structure determination using chemical shifts: CHESHIRE (CHEmical Shift Restraints) [176], CS-ROSETTA [177], and CS23D (Chemical Shift to 3D structure) [178].

3 Anisotropic chemical shifts

3.1 CSAs of nuclei in peptides and proteins

It is expected that CSA tensors can provide insights into the local secondary structure and dynamics for individual residues in peptides and proteins, as well as their inter-residual besides their inter-residual interactions through N-H..O=C hydrogen bond networks. Both principal components and orientations of CSA tensors are straightforwardly obtained in the solid-state, as described in section 1.2. The orientation information can also be derived from polycrystalline samples through the interactions between X CSA and X-Y dipolar tensors, where spins X and Y are dipolar coupled.

3.1.1 13C CSA

The Gly 13C′ principal values (δ11, δ22 and δ33 for 13C′ nucluei in Gly and their orientations for several single crystalline [179,180] and polycrystalline [42,113,181,182] peptides reported in the literature are summarized in Table 4. The frequency values of many of the principal components are converted and reported with reference to TMS. These values span a wide range of 242–88 ppm. It is noted that the orientations of the principal component δ22 for 13C′ is not always collinear with the C=O bond [179–182] although the δ33 axis is perpendicular to the peptide plane [42 113,179–182], except for [1-13C, 10%] 1Gly2Gly·HCl·H2O (tilt angle of 85°) [180], as illustrated in Fig. 9. It is also noteworthy that the peak positions corresponding to δ22 differ substantially among the peptides, although the peak positions of δ11 and Δδ are almost unchanged. The 13C′ δ11 of [1-13C]Gly[15N]Gly·HCl·H2O lies in the peptide plane and forms an angle of 77° relative to the C=O bond [179]. Measurements have been made of the magnitudes of the deviation of the bond axis for single crystalline samples of [1-13C, 10%]GlyGly, [1-13C, 10%] GlyGly·HNO3, and [1-13C, 10%] 1Gly2Gly·HCl·H2O for various hydrogen bond angles in O-H..O=C< type was examined [180]. For the 13C′ principal values of Ala residue in some peptides, see Table 4 [42,114].

Table 4.

The amide 13C chemical shift tensors of peptides in the solid state

| Peptides | Angle between δii and X-Y bond axis | δ11a ppm | δ22a ppm | δ33a ppm | Δδb ppm | δiso ppm | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1-13C]Gly[15N]Gly HCl H2O | δ22: 13° from C=O bond axis | 244.1 | 177.1 | 87.9 | 111.6 | 169.7 | single crystal. δ convertedc | 179 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]GlyNH2 | δ22: parallel to C=O bond axis | 243.0 | 184.9 | 91.2 | 105.0 | 172.8 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. δ converted | 181 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]AlaNH2 | δ22: parallel to C=O bond axis | 242.1 | 184.9 | 90.0 | 104.7 | 172.3 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 181 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]TyrNH2 | δ22: −6° from C=O bond axis | 242.5 | 165.5 | 95.3 | 112.1 | 167.8 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 181 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]Gly HCl | δ22: −12° from C=O bond axis | 243.8 | 177.2 | 89.1 | 110.7 | 170.0 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 181 |

| [1-13C]Ala[15N]Ala | δ22: 3.6° from C=O bond axis. | 244 | 170.8 | 95 | 111.1 | 169.9 | 13C-15N dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 182 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]AlaNH2 | δ11: −36.6° from C′-N bond axis. | 242.1 | 184.9 | 90.0 | 104.7 | 172.3 | 13C-15N dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 182 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]TyrNH2 | δ11: −40.7° from C′-N bond axis. | 242.5 | 165.5 | 95.3 | 112.1 | 167.8 | 13C-15N dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 182 |

| [1-13C]Gly[15N]Gly HCl | δ11: −46.6° from C′-N bond axis. | 243.8 | 177.2 | 89.1 | 110.7 | 170.0 | 13C-15N dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 182 |

| Ac[1-13C]Gly[15N]GlyNH2 | δ11: −34.5° from C′-N bond. | 243 | 184.2 | 91.2 | 105.3 | 172.8 | 13C-15N dipole coupled powder. δ: converted | 182 |

| [1-13C, 10%]GlyGly HCl H2O | δ22: 13° from C=O bond axis | 242.1 | 177.1 | 87.9 | 109.6 | 169.7 | single crystal. | 180 |

| [1-13C, 10%]GlyGly HNO3 | δ22: 5° from C=O bond axis | 248.1 | 167.8 | 89.1 | 119.7 | 168.3 | single crystal. | 180 |

| [1-13C, 10%]GlyGly | δ22: 10° from C=O bond axis | 242.3 | 173.8 | 88.2 | 111.3 | 168.1 | single crystal. | 180 |

| [1-13C, 99%]AlaGly H2O | 245 | 179 | 93 | 109 | 172.6 | Polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 42 | |

| [1-13C, 99%]AlaSer | 249 | 172 | 89 | 118.5 | 170.1 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 42 | |

| [1-13C, 99%]AlaProGly H2O | 235 | 178 | 95 | 98.5 | 169.3 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 42 | |

| [1-13C, 90%]ValGlyGly | 245 | 170 | 93 | 113.5 | 169.2 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 114 | |

| BocPro[1-13C, 90%]IleGly | 249 | 183 | 88 | 113.5 | 173.0 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 114 | |

| D,L-[1-13C, 90%]LeuGlyGly | 246 | 178 | 92 | 111 | 172.0 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 114 | |

| [1-13C, 90%]AspGly | 242 | 175 | 93 | 108 | 170.3 | polycrystalline; spinning side bands | 114 | |

| N+H3CH(CH3) COO− | 1. δ11: 9.4° from C′-Cα bond axis, | 242.9 | 183.5 | 106.7 | 97.8 | 177.7 | single crystal. δ: converted | 55 |

| 1. COO− 2. CH3(Cβ) |

2. δ33: 4.3° from Cα-Cβ bond axis. | 30.3 | 21.4 | 8.3 | 15.5 | 20.0 |

δ11 > δ22 > δ33. δ11 is most deshielded component and δ33 the most shielded component. δ: relative to TMS.

Δδ = δ33 − (1/2)(δ11 + δ22)

δ: converted from liq. benzene reference to TMS reference [δ for liq. benzene: 128.5 ppm relative to TMS.

Magnitudes of displacements of chemical shifts accompanying conformational changes were examined for Gly 13C′ CSAs of [2-13C, 8 %] (Gly)n, taking I (β-sheet) and II (31-helix) forms, and the guest [2-13C, 8%] Gly incorporated into host (β-benzyl L-aspartate)n or (β-benzyl L- glutamate)n [127,183,184], and also for Ala C′, Cα and Cβ CSAs [185]. Magnitudes of displacement upon conformational changes are larger for δ22 and δ33, while δ11 is almost unchanged (Table 5). Ala 13Cα and 13Cβ CSAs of (Ala)n with the αR-helix and β-sheet forms indicate that the most deshielded value of δ11 for Ala Cα and Cβ are very sensitive to conformational changes and are responsible for the observed conformation-dependent isotropic chemical shifts [186]. The 13Cα CSAs of Ala, Val and Leu in a series of various crystalline peptides of known structure have also been determined [187]. The magnitudes and orientations of the principal components of 13Cα and 13Cβ CSAs of a L-alanine single crystal have been reported and these tensors are not axially symmetric but their values are very small [55]. The direction of the most shielded δ33 axis for Cβ and Cα carbons is almost parallel to the Cα-Cβ bond within ± 5° and is tilted by 25° from the Cα-N bond, respectively.

Table 5.

Conformation-dependent changes in the 13C principal values of some polypeptides

| Sample | Conformation | Amino-acid residues | Carbons | δ11 ppm | δ22 ppm | δ33 ppm | Δδ ppm | δiso ppm | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Gly)n I | β–sheet | Gly | C′ | 243 | 174 | 88 | 121 | 168.3 | 183 |

| (Gly)n II | 31 -helix | Gly | C′ | 243 | 179 | 94 | 117 | 171.8 | 183 |

| (Gly)n I | β–sheet | Gly | CH2 | 60 | 45.0 | 28 | 25 | 44.3 | 184 |

| (Gly)n II | α-helix | Gly | CH2 | 61 | 45.7 | 25 | 28 | 43.7 | 184 |

| (Asp(OBzl), Gly*)n | α-helix | Gly | CH2 | 65 | 44.1 | 25 | 29.6 | 44.8 | 184 |

| (Asp(OBzl), Gly*)n | ω-helix | Gly | CH2 | 65 | 46.5 | 24 | 31.8 | 45.1 | 184 |

| (Ala, Gly*)n | α-helix | Gly | C′ | 244 | 178 | 94 | 116 | 176.4 | 183 |

| (Leu, Gly*)n | α-helix | Gly | C′ | 242 | 179 | 94 | 117 | 175.7 | 183 |

| (Glu(OBzl), Gly*)n | α–helix | Gly | C′ | 243 | 178 | 95 | 116 | 172.0 | 183 |

| (Asp(OBzl), Gly*)n | α– helix | Gly | C′ | 243 | 178 | 95 | 116 | 172.0 | 183 |

| (Asp(OBzl), Gly*)n | ω–helix | Gly | C′ | 242 | 178 | 93 | 117 | 171.1 | 183 |

| (Val, Gly*)n | β-sheet | Gly | C′ | 242 | 171 | 93 | 114 | 168.5 | 183 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | C′ | 247.1 | 192.5 | 93.8 | 104.0 | 177.8 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | Cα | 72.1 | 54.3 | 31.7 | 29.2 | 52.7 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | Cβ | 25.3 | 19.5 | 0.6 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | C′ | 243 | 194 | 99 | 177 | 178.7 | 42 |

| (Ala)n | β-sheet | Ala | C′ | 245.4 | 173.2 | 95.3 | 111.2 | 171.3 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | β-sheet | Ala | Cα | 59.7 | 54.6 | 31.6 | 16.6 | 48.6 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | β-sheet | Ala | Cβ | 37.7 | 16.1 | 5.3 | 27.0 | 19.7 | 186 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | Cα | 72.0 | 51.9 | 39.0 | 26.6 | 53.3 | 185 |

| (Ala)n | α-helix | Ala | Cβ | 23.4 | 18.1 | 2.3 | 13.2 | 15.8 | 185 |

| (Ala)n | β-sheet | Ala | Cα | 64.6 | 49.7 | 32.4 | 23.6 | 48.9 | 185 |

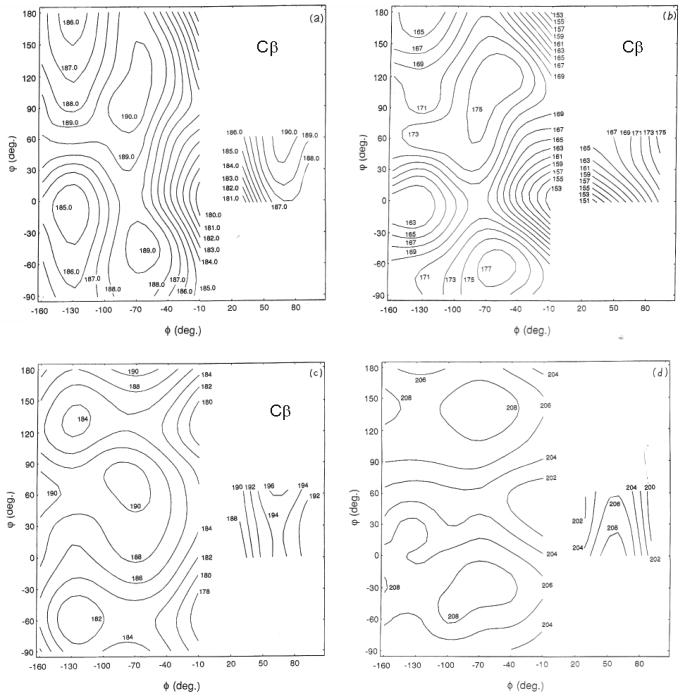

FPT-INDO MO calculations have been performed for Gly and Ala residues having torsion angles of an α-helix taken from N-acetyl-N′-methyl glycine amide and N-acetyl-N′-methyl L-alanine amide, respectively, both of which are hydrogen bonded to two formamide molecules to reveal the directions of principal components of 13C CSA tensors [113,114]. More accurate predictions for the directions of 13C chemical shift tensor components for Ala Cα and Cβ from the latter were carried out by the GIAO-CHF method with the 4–31 basis set, as illustrated in Fig. 15 [118]. It was shown that the direction of the most shielded δ33 axis of Ala Cβ lies almost along the Cα-Cβ bond for αR-helix, βA-sheet, 310R-helix and the helix near the 31-helix with small deviations of 7.4°, 11.0°, 5.8° and 7.4°, and also that the δ11 axis is nearly perpendicular to the plane defined by Cβ, Cα, and N atoms in Ala residue and δ22 is parallel to the plane [118]. These results agree with the experimentally determined direction of δ33 of the 13Cβ CSA of L-alanine [50].

Fig. 15.

The calculated 13C chemical shift map of the Cβ and Cα carbons of N-acetyl-N′-methyl-L-alanine amide calculated by using the GIAO-CHF method with a 4-31G ab initio basis sets. The 4-31G optimized geometries for the peptide were employed. (a) σiso, (b) σ11, (c) σ22, and (d) σ33 for the Cβ carbon (in ppm), and (e) σiso, (f) σ11, (g) σ22, and (h) σ33 for the Cα carbon (in ppm). A positive σ means shielding. Reproduced with permission from [118]. Copyright 1994 Elsevier.

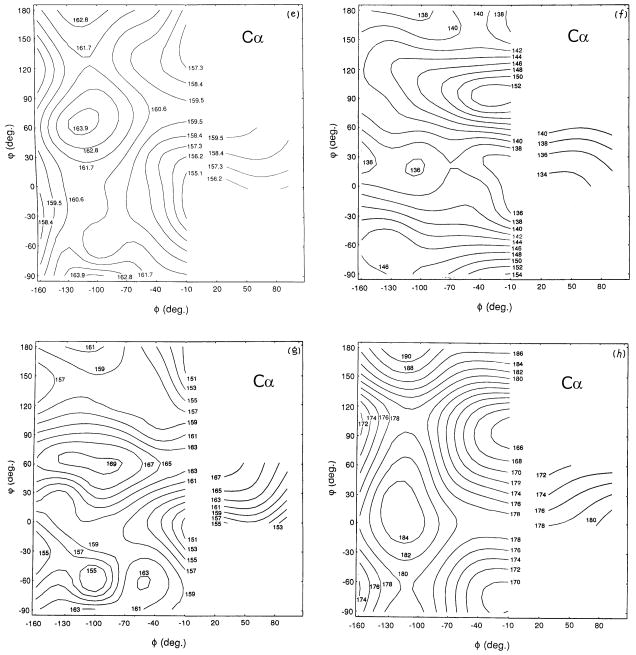

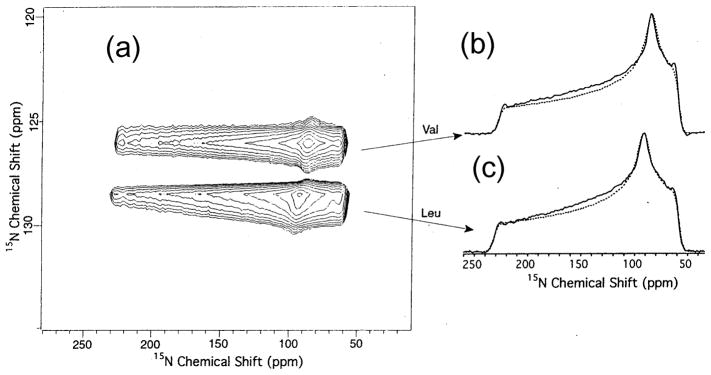

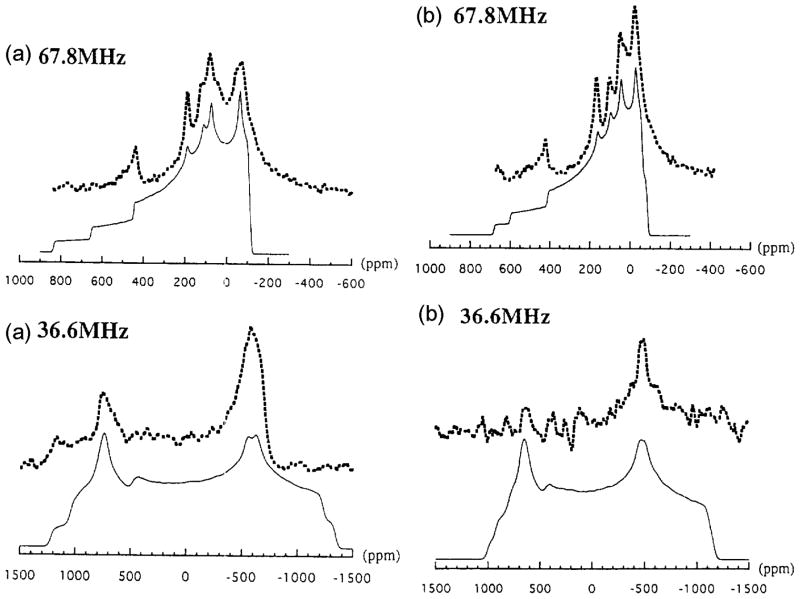

3.1.2 15N CSA

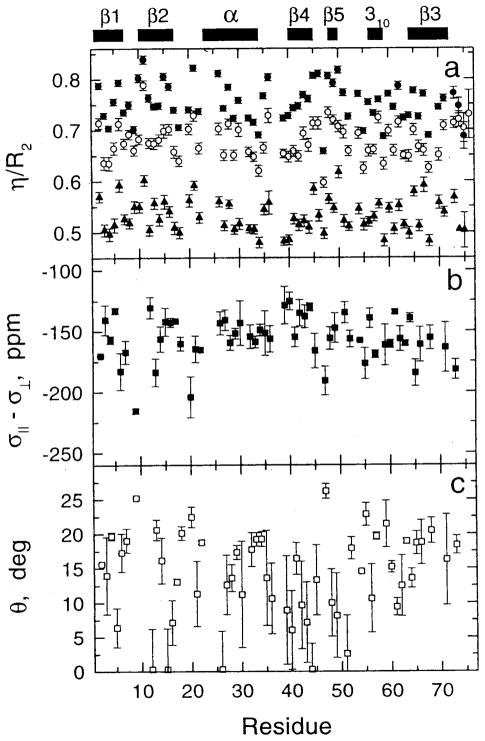

15N CSA principal components and their orientations for a variety of single crystalline [188–190] and polycrystalline [58,62–65,126,127,181,182, 191–204] peptides reported in the literature are summarized in Table 6. It is seen that the orientation of δ11 lies approximately close to the N-H bond with a deviation of up to 25°, δ33 lies approximately along the N-C(=O) bond, and δ22 is aligned in the direction perpendicular to the peptide plane (see Fig. 9). The orientation of the tensor can be also described by the angle that δ11 makes with the C′-N bond axis. The δ11 axis of Ala-[15N]Pro-Gly in a single crystal, deviates 23° from the N-Cα bond and lies 5° below the peptide plane, whereas the orientation of δ22 is 4° away from the peptide plane normal and δ33 lies approximately in the peptide plane [189]. The δ11 of Ala-[15N]Gly-Gly is 11° out of the peptide plane defined by accurate heavy atom positions N(Gly-2), Cα(Gly-2), and C(=O)(Ala-1), and δ22 is rotated by 15° away from the peptide plane normal. The most deshielded δ11 axis of Gly-[15N]Gly-Val is 1° out of the peptide plane and is tilted by 23° from the N-H bond, but the δ22 and δ33 axes are substantially rotated about δ11 such that δ22 is off from the peptide plane normal by 36°. The possibility of conformation-dependent 15N CSA principal values for α-helix, 31-helix and β-sheet structures has been examined for (Ala)n, (Gly)n and Ala- or Gly-residues involved in polypeptides (Table 7). It appears that the values of δ22 of Ala residues, and δ11 of Gly residues are sensitive parameters for distinguishing between α-helix and β-sheet conformations, but the rest of the components including Δδ are insensitive. In contrast, only the δ11 values are sensitive differences between α-helix and β-sheet conformations. It is not easy, however, to distinguish the 31-helix from the α-helix and β-sheet conformations by using 15N CSA information.

Table 6.

The amide 15N chemical shift tensors of peptides and proteins in the solid state

| Peptides | Angle between δii and X-Y bond axis | δ11a ppm | δ22a ppm | δ33a ppm | Δ δb ppm | δiso ppm | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ac[1-13C]Ala [15N]AlaNH2 | δ11: 100° from C′-N bond axis, | 229.4 | 85.1 | 44.6 | 164.6 | 119.7 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. | 190 |

| Ac[1-13C]Ala [15N]TyrNH2 | δ11: 98° from C′-N bond axis | 209.3 | 77.1 | 52.1 | 144.7 | 112.8 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. | 190 |

| [1-13C]Gly[15N]GlyHCl | δ11: 20° from N-H bond axis | 210.0 | 59.8 | 57.3 | 151.5 | 108.9 | 15N-dipole coupled powder. | 190 |

| Gly[15N]Gly | δ11: 21° from N-H bond axis | 222.9 | 79.7 | 46.8 | 159.6 | 116.5 | dipolar/CS | 199 |

| Gly[15N]GlyH2O | δ11: 25° from N-H bond axis | 223.7 | 78.9 | 48.4 | 160.0 | 117.0 | 2D dipolar/CS | 140 |

| Gly[15N]GlyHClH2O | 210.2 | 64.8 | 59.2 | 148.2 | 111.4 | 2D dipolar/CS | 140 | |