Abstract

myo-Inositol-1-phosphate synthase is a conserved enzyme that catalyzes the first committed and rate-limiting step in inositol biosynthesis. Despite its wide occurrence in all eukaryotes, the role of myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase and de novo inositol biosynthesis in cell signaling and organism development has been unclear. In this study, we isolated loss-of-function mutants in the Arabidopsis MIPS1 gene from different ecotypes. It was found that all null mips1 mutants are defective in embryogenesis, cotyledon venation patterning, root growth, and root cap development. The mutant roots are also agravitropic and have reduced basipetal auxin transport. mips1 mutants have significantly reduced levels of major phosphatidylinositols and exhibit much slower rates of endocytosis. Treatment with brefeldin A induces slower PIN2 protein aggregation in mips1, indicating altered PIN2 trafficking. Our results demonstrate that MIPS1 is critical for maintaining phosphatidylinositol levels and affects pattern formation in plants likely through regulation of auxin distribution.

Keywords: Development, Embryo, Endocytosis, Endosomes, Trafficking

Introduction

Inositol is a precursor for many inositol-containing compounds that play critical and diverse roles in signal transduction, membrane biogenesis, vesicle trafficking, and chromatin remodeling (1–3). Higher plants contain abundant inositol and inositol-derived compounds such as inositol phosphates, phosphatidylinositide, and sphingolipids. These compounds are involved in gene expression modulation, hormonal signaling, guard cell movement, stress response, disease resistance, and membrane and cell wall biogenesis (4–9). Plant seeds also contain high levels of inositol hexakisphosphate (phytate), which serves as phosphorus storage, but it also is considered to be an anti-nutrient because its phosphorus and the associated minerals are not available to monogastric animals (10). To reduce the phytate content in cereal seeds has been an objective actively pursued by the agrobiotechnology industry (10, 11).

Inositol is synthesized from glucose 6-phosphate by 1l-myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase (also known as 1d-myo-inositol-3-phosphate synthase) (MIPS).2 The reaction generates inositol 1-phosphate, which is then dephosphorylated by an inositol monophosphatase to form myo-inositol (12). Because MIPS catalyzes the rate-limiting step in inositol biosynthesis, MIPS may be important in determining the pool size of inositol and its derivatives in cells. Nonetheless, inositol can also be recycled from inositol-containing compounds, and it is thus not clear whether de novo inositol synthesis plays a regulatory role in modulating phosphoinositide levels in multicellular organisms. Furthermore, information about the role of MIPS in plant growth and development is also limited.

Previously, plants with reduced MIPS transcript levels obtained by antisense or RNA interference suppression were found to be defective in embryo development in maize (13), seed development in soybean (14), or apical dominance in potato (15). Recently, the role of inositol synthesis in cell death and pathogen resistance was also identified (16–18). Here, we report that null mutations in the inositol-phosphate synthase MIPS1 gene in Arabidopsis have dramatic impacts on plant development, including impaired embryogenesis, altered cotyledon development and venation pattern, distorted root cap organization, root agravitropism, and reduced basipetal transport of the phytohormone auxin. The mips1 mutants have reduced contents of major phosphatidylinositol species and altered trafficking of the auxin efflux carrier PIN2. Our study thus establishes an essential role of MIPS1 in auxin transport and organ pattern formation. It also suggests that MIPS1 may not be a good target for controlling phytate levels in seeds.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used in all experiments except where indicated. The mips1-4 T-DNA in the C24 background was isolated in our genetic studies of abiotic stress signal transduction. The mips1-2 (SALK_023626), mips1-5 (CS851587), and mips2-1 (SALK_031685) T-DNA lines were isolated from the Salk T-DNA insertion library. The eir1-1 and aux1-7 mutants were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Columbus, OH). The homozygous mips1-2 (SALK_023626) T-DNA line was used in all experiments unless otherwise stated. The eir1 mips1-2 and aux1 mips1-2 double mutants were selected by genotyping progenies of genetic crossings between the respective single mutants. The derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences (dCAPS) primers 5′-TTGTTGATCATTTTACCTGGGACA and 5′-GGTTGCAATGCCATAAATAGAC (with BseLI restriction site) were used for genotyping of eir1-1. Because mips1-2 single mutant seedlings do not have altered 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) tolerance relative to the wild type, the aux1 mips1-2 double mutant was selected from the segregating F2 population on 100 nm 2,4-D. Seeds were surface-sterilized with bleach and planted onto half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) media supplemented with 3% sucrose and 0.6% agar. For rescue of mips1 mutants, myo-inositol of various concentrations was added into the medium. After 2 days of cold treatment, plates were incubated at 22 °C under constant white light for seed germination and seedling growth. For root growth assays, seedlings grown on plates with 1.2% agar were incubated vertically and photographed using a digital camera. Soil-grown plants were kept in a growth room at 22 °C with a 16-h light period.

Plant Transformation

The MIPS1 cDNA was amplified with primers 5′-CACCATGTTTATTGAGAGCTTCAAAG and 5′-CCATGATCATGTTGTTCTCC. The 1.1-kb MIPS1 promoter was amplified with primers 5′-CACCACTAGTGTAACTTGGAAAAGC and 5′-GCTTCTAATCAGCGGAGAC. The PCR fragments were ligated into the pENTR-D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). After sequence confirmation, they were cloned into the pMDC Gateway vectors through LR clonase recombination. Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 were transformed by electroporation with these constructs. Four-week-old Arabidopsis plants were then vacuum-infiltrated with the transformed Agrobacterium strains, and transformants were screened using the respective antibiotics.

Phosphatidylinositol Analysis

Phospholipids were extracted and analyzed using an API 4000 liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as described previously (19). Five replicates were carried out with 10-day-old seedlings.

Root Curling and Root Curvature Measurements

For root curling assay, seeds were planted on a half-strength MS plate and vertically grown for 5 days. The plate was then laid flat for 2 more days before taking pictures. For measurement of root curvature, the plates with vertically grown 5-day-old seedlings were rotated 90°, and pictures were taken every hour. The root curvature was measured using the NIH imaging software. Root realignment assay and Mann-Whitney rank order sum test were performed as described previously (20).

Auxin Polar Transport Assay

Basipetal and acropetal auxin polar transport assays were performed as described using 3H-labeled indole-3-acetic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemical, St. Louis, MO) (21). Three replicates, each with 10 seedlings, were carried out.

RNA Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from 10-day-old seedlings grown on half-strength MS agar media by using the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's manual (Invitrogen). For RNA blotting analysis, 10 μg of total RNA were loaded onto 1.5% formaldehyde-agarose gels. MIPS1 gene-specific probe was generated with ∼300-bp 3′-untranslated region fragment. RNA gel blots were autoradiographed to a phosphorimager screen (Amersham Biosciences).

Histochemical Staining

Seedlings or tissues from transgenic plants were vacuumed in staining solution (25 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 10 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm ferricyanide, 0.5 mm ferrocyanide, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 2 mm 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-glucuronide cyclohexylamine salt) for 10 min before staining at 37 °C. After staining, the solution was replaced with 75% ethanol to remove chlorophyll.

Confocal, Light, and Scanning Electron Microscopy

Whole seedlings were mounted in water under glass coverslips for green fluorescent protein visualization using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon Eclipse E-800 C1) equipped with a krypton-argon laser. Roots were stained with 10 μg per ml propidium iodide for 2 min before taking root cap pictures using the same microscope.

For FM4-64 (Invitrogen) uptake assay, 5-day-old seedlings were incubated in 5 μm FM4-64 dye prepared in a liquid MS medium for 5 min on ice, and images were taken immediately or after incubation in the MS medium at room temperature for 30 or 60 min using a confocal microscope. For BFA treatments, 5-day-old seedlings were first incubated in an MS medium containing 50 μm BFA for 2 h and then in an MS medium with 5 μm FM4-64 and 50 μm BFA for 30 min before taking pictures. More than 30 seedlings were examined for each treatment.

The PIN2-GFP (22) or PIP2-GFP (23) transgene was introduced into mips1-2 by crossing, and homozygous progenies were observed for their green fluorescent protein fluorescence using a confocal microscope as described above. BFA treatment of seedling was carried out at 50 μm for 30, 60, or 90 min, and images were taken immediately or after washout in half-MS for 2 h. More than 30 seedlings were examined for each treatment.

Whole-mount preparation of ovules was conducted by incubating the ovules in Hoyer's solution (chloral hydrate/glycerol/water, 80:13:30 g) overnight at room temperature. To observe the cotyledon vein pattern, cotyledons from 7-day-old seedlings were fixed in a 3:1 mixture of ethanol/acetic acid overnight. The seedlings were then cleared overnight in saturated chloral hydrate. For starch granule staining, 3-day-old seedlings were stained for 3 min with 1% Lugol's solution (consists of 0.05% iodine (I2) and 0.1% potassium iodide) and then rinsed with water and cleared with saturated chloral hydrate briefly. Differential interference contrast images of cleared ovules, cotyledons, and root caps were taken with a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope and a QImaging (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada) Retiga cooled camera.

Scanning electron micrographs of 13-day-old cotyledons or rosette leaves were taken with a Hitachi TM-1000 electron microscope. Stomatal primary and secondary complexes were counted as described previously (24). More than 250 stomatal complexes from three representative seedlings were scored for each genotype.

RESULTS

Arabidopsis MIPS1 Gene and Its Regulation

While conducting a genetic study of stress and abscisic acid signal transduction in Arabidopsis (25), we isolated a T-DNA insertion mutant in the C24 background with disruption in an inositol-phosphate synthase gene (MIPS1, At4g39800). In Arabidopsis, there are three MIPS homologs with more than 80% identity at the amino acid level: MIPS1 (AT4G39800) (also called IPS) (26), MIPS2/IPS2 (AT2G22240), and MIPS3/IPS3 (AT5G10170). The enzyme activity of MIPS1 in inositol biosynthesis has been demonstrated by both in vitro assay and yeast complementation (26). The public Arabidopsis microarray databases indicate that the transcript level of MIPS1 is predominant over that of MIPS2 and MIPS3 at all development stages except seed maturation and early germination stages. At these stages, the transcript level of MIPS2 is comparable with that of MIPS1, although the MIPS3 level is much lower at all developmental stages (supplemental Fig. S1) (27, 28).

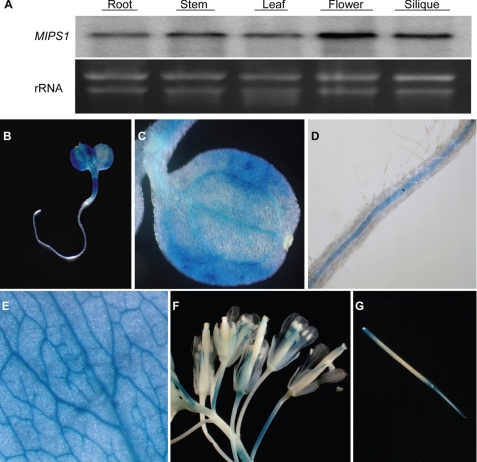

To investigate whether there is any organ-specific expression of MIPS1, we checked the transcript levels of MIPS1 in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and siliques. MIPS1 transcripts were detected in all plant parts examined, with the highest level in floral tissues (Fig. 1A). Because inositol and its derivatives are known to play roles in stress signal transduction and salt tolerance (7, 8), we examined whether MIPS1 is regulated by stress. However, we found that MIPS1 transcript levels were not regulated by either salt stress or abscisic acid (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Expression pattern of MIPS1. A, MIPS1 transcript levels in different plant parts detected by RNA blot analysis. Ten μg of total RNA from roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and siliques were loaded per lane. B–G, MIPS1::GUS expression patterns in whole seedling (B), cotyledon (C), root (D), mature leaf (E), floral organ (F), and silique (G). GUS staining was performed overnight.

Transgenic plants expressing the MIPS1 promoter-driven β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene were generated to examine the expression of MIPS1 at the tissue level. In young seedlings, MIPS1 promoter activity was detected in cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots, with especially strong signals in vascular tissues (Fig. 1, B–D). GUS expression was also observed in mature leaf vascular tissues (Fig. 1E). In floral organs, GUS expression was evident in filaments (Fig. 1F), tips of siliques (Fig. 1G), and the joint region of silique and pedicel (Fig. 1G).

By fractionation and immunocytochemistry analysis, Lackey et al. (29) showed that MIPS in Phaseolus vulgaris is widely distributed in intracellular compartments, including cytoplasm, membrane-bound organelles, and cell walls as well. On the contrary, using immunogold-labeled anti-MIPS antibody, Mitsuhashi et al. (27) reported that MIPS proteins exclusively locate in the cytosol of developing Arabidopsis seeds. To investigate the MIPS1 localization in planta, we generated stable transgenic plants expressing the GFP-MIPS1 fusion protein. As shown in supplemental Fig. S2, A–C, MIPS1 was found to accumulate mainly in the cytoplasm and possibly at cellular membranes but not in cell walls (supplemental Fig. S2, D–F). To further investigate a possible membrane association of MIPS1, an EYFP-MIPS1 construct was co-infiltrated into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker CFP-HDEL (30) or the Golgi marker GmMan1-CFP (31). The EYFP-MIPS1 showed a similar localization as the GFP-MIPS1 in Arabidopsis, i.e. in the cytoplasm and also likely in membranes (supplemental Fig. S2, G and H). Although multiphoton optical sections and time-lapse imaging found that the EYFP-MIPS1 signal was associated with the ER marker in some subcellular domains (supplemental Fig. S2K), the signal did not co-localize with the Golgi marker (supplemental Fig. S2L). In Arabidopsis, the GFP-MIPS1 signal was also not internalized upon BFA treatments (supplemental Fig. S2N), suggesting that the GFP-MIPS1 may be partly associated with the ER but not Golgi bodies.

mips1 Mutants Exhibit Defects in Seedling Development and Have Reduced Levels of Phosphatidylinositols

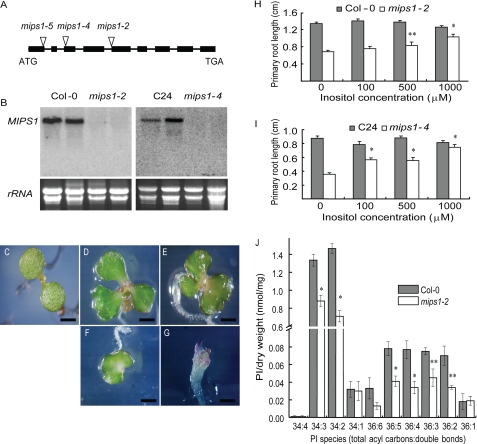

To investigate the role of MIPS in plant development, we identified additional homozygous T-DNA insertional lines of MIPS1 (Fig. 2A) and MIPS2 in the Columbia-0 (Col-0) background from the SALK T-DNA library (32). RNA analysis did not detect any full-length MIPS1 transcript in the mutant lines (Fig. 2B), indicating that these mutants are null for MIPS1. Along with the mips1-4 mutant we isolated in the C24 background (Fig. 2B), these T-DNA lines were compared for their potential growth and developmental alterations. It was found that mips1 mutants in different genetic backgrounds have identical phenotypes and failed to complement one other. On the other hand, the mips2 mutants did not display any obvious defects in growth and development.

FIGURE 2.

Seedling phenotypes of the mips1 mutants. A, structure of the MIPS1 gene. Boxes represent exons. The sites of T-DNA insertions are indicated. B, MIPS1 transcript levels in wild type and mips1 mutants detected with the RNA blotting analysis. mips1-2 (SALK_023626) and mips1-5 (CS851587) are in the Col-0 background, and mips1-4 is in the C24 background. C–G, Col-0 seedling (C) and representative mips1-2 seedlings defective in cotyledon development (D–G). H and I, root length of 10-day-old wild type and mips1 seedlings on an MS plate without or with 100, 500, or 1000 μm inositol. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 20). J, levels of phosphatidylinositol species in 10-day-old Col-0 and mips1-2 seedlings. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 5 biological replicates). Bars, 1 mm (C) and 2 mm (D–G). **, p < 0.05; *, p < 0.01.

One obvious phenotype of mips1 at the early seedling stage is that the mutants display cotyledon defects such as altered cotyledon size, number, arrangement, and morphology. Fig. 2, D–G, shows the morphology of representative mips1-2 seedlings with one cotyledon, three cotyledons, a fused cotyledon, or in the most severe case, no cotyledons. Cotyledons of most mips1-2 mutants are lobed or serrated and have width-to-length ratios greater than one instead of less than one in the wild type (Fig. 2, D–F). Representative mips1-2 mature plants displayed increased branching and shorter statures (supplemental Fig. S3A). The scanning electron micrograph of cotyledon epidermis shows that mips1-2 mutants have an increased number but smaller sized epidermal cells and altered patterning of stomata (supplemental Fig. S3, B–D). In contrast to predominantly primary stomatal complex development in WT (77.97% ± 0.06 primary complex, 22.04% ± 0.06 secondary complex; see “Experimental Procedures”), mips1-2 mutant showed predominant higher order stomatal complex (42.8% ± 0.02 primary complex, 42.4% ± 0.05 secondary complex, and 14.8% ± 0.03 tertiary complex). mips1 seedlings also have shorter primary roots (Fig. 2, H and I). To test whether exogenous inositol can rescue some of these phenotypes, inositol was supplied in the growth media. Although the inositol treatment did not have a noticeable effect on the growth of the wild type seedlings, it did significantly improve the mips1 primary root growth at higher concentrations (Fig. 2, H and I).

Given the possibility that the level of inositol has an impact on phosphatidylinositide synthesis, we analyzed the content of phosphatidylinositols, the precursors of phosphatidylinositides, in mips1-2. Indeed, the MIPS1 null mutant was found to have greatly reduced levels of most of the phosphatidylinositol species examined (Fig. 2J).

MIPS1 Is Required for Embryo Development and Vascular Patterning

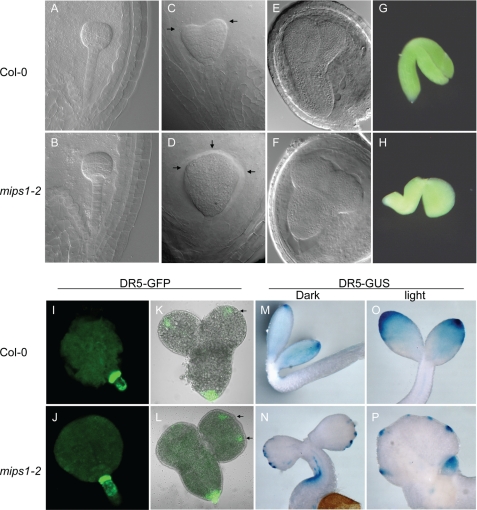

The abnormal cotyledon patterning (Fig. 2) of mips1 suggests that MIPS1 may affect embryo development. To determine at which stage cotyledon development was affected in the mutant, siliques from different development stages were dissected, and the developing embryos were cleared for observation under a microscope. Although no clear defects in early stages of embryogenesis could be observed (Fig. 3, A and B), abnormality can be seen starting from the transition to the heart stage (Fig. 3, C and D) when, coincidently, the transcript of the MIPS1 gene starts to increase, whereas that of MIPS2 gene starts to decrease (33) (supplemental Fig. S4). Fig. 3D shows that one heart stage embryo of mips1-2 has three developing cotyledons instead of two in the wild type (Fig. 3C). The torpedo stage embryos of mips1-2 exhibited increased lateral proliferation and resulted in expansion of the cotyledon compared with elongated cotyledons in the wild type (Fig. 3, E and F). When mature embryos were dissected out of seed coats, most mips1-2 embryos did not fold, or only partially folded, compared with the fully folded embryonic root and cotyledons in the wild type (Fig. 3, G and H).

FIGURE 3.

Embryo development and the DR5 reporter expression pattern in mips1 mutants. A–H, embryos at the early globular stage of WT Col-0 (A) and mips1-2 (B), heart stage of WT (C) and mips1 (D), torpedo stage of WT (E) and mips1 (F), and mature embryo of WT (G) and mips1 (H). I–L, DR5-GFP in embryos at the later globular stage of WT (I) and mips1 (J), torpedo stage of WT (K) and mips1 (L). M–P, multiple restricted DR5-GUS maxima in cotyledons of 2-day-old mips1-2 grown in the dark (M) or in the light (O) compared with one diffusive DR5-GUS maximum in cotyledons of 2-day-old Col-0 grown in the dark (N) or in the light (P).

It was proposed that lateral organ patterning was established by local auxin gradients (34). We thus checked the expression of auxin maxima reporter DR5-GFP and DR5-GUS in mips1-2 mutant. Although no clear alteration of the DR5-GFP expression pattern was observed at early stages of the embryo development (Fig. 3, I and J), embryos at later stages exhibited altered expression of the DR5-driven reporter genes. Corresponding to the expanded cotyledons in mips1-2 embryo, DR5-GFP expression indicated that multiple auxin maxima are often formed in mips1-2 cotyledons compared with only one auxin maximum per cotyledon in the wild type (Fig. 3, K and L). Similarly, multiple DR5-GUS maxima are found along the cotyledon margins of 2-day-old mips1-2 seedlings grown under either light or dark conditions (Fig. 3, N and P), whereas only one auxin maximum at the very end of the cotyledon tip can be detected in the wild type (Fig. 3, m and O). Interestingly, the auxin maxima of mips1-2 are more confined than that of the wild type, which show a more diffused pattern (Fig. 3, M–P).

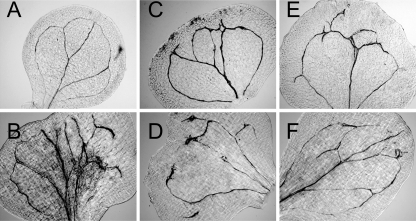

The lobed cotyledon morphology is often associated with vascular patterning alterations. We thus examined mips1-2 mutants for their vascular patterning. In wild type plants, the vascular tissues of the cotyledons form near symmetrical, continuous architectures (Fig. 4A). However, venation patterns of mips1-2 were asymmetric and display multiple abnormalities, including altered numbers of vascular branches (Fig. 4, B–F), incorrect vein orientation (Fig. 4F), extra free endings (Fig. 4, B–F), and extra loops (Fig. 4, B–F). In addition, mips1-2 mutants also had extra proliferation of vascular tissues at the free endings or junctions (Fig. 4, B–F).

FIGURE 4.

Altered cotyledon vein patterning in mips1. A–F, differential interference contrast (DIC) images of cleared 7-day-old seedling cotyledons of Col-0 (A) and mips1-2 (B–F).

mips1 Mutants Are Defective in Root Gravitropic Responses and Root Cap Organization

In addition to their shorter roots, mips1 roots are unable to grow straight downward on vertically placed MS medium plates, similar to the auxin-resistant mutant aux1. To further characterize this phenotype, we first used the root-curling assay to test whether mips1 has altered gravitropism. Fig. 5A shows that wild type roots formed complete curls 2 days after the plate was placed horizontally, whereas mips1 roots grew more randomly instead of forming complete curls. Next, we studied the gravity response by measuring root tip curvature of 5-day-old seedlings. Plates with vertically grown seedlings were rotated 90°, and pictures were taken every hour during the realignment of root tips with the new gravity vector. Compared with the significant response of the wild type 1 h after the reorientation, very limited curvature was observed in mips1 root tips (Fig. 5B). Two hours later, mips1 root tips exhibited a curvature smaller than that of the wild type at 1 h. In fact, the curvature of mips1 roots is about 20° less than that of the wild type at each time point examined (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results demonstrate that mips1 mutants are indeed defective in gravity response.

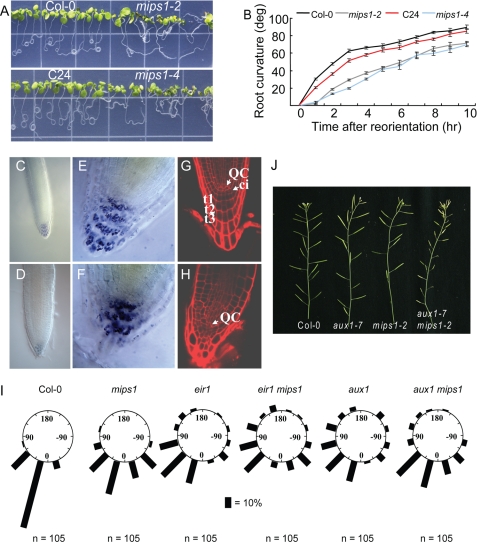

FIGURE 5.

Root gravitropism and columella cell patterning in mips1. A, root curling assay of the wild type and mips1 seedlings. The pictures were taken 2 days after the plate was placed horizontally. B, root curvature of 5-day-old wild type and mips1 roots. Shown are means ± S.E. (n = 33). C and D, Lugol's solution stained Col-0 (C) and mips1-2 (D) root tips. E and F, high magnification of Col-0 (E) and mips1-2 (F) root cap stained with Lugol's solution. G and H, propidium iodide-stained Col-0 (G) and mips1-2 (H) root tips. QC, quiescent center; ci, columella initials; t1, t2, t3, the first three columella cell layers of the root cap. I, quantitative analyses of root re-orientation of mips1, eir1, aux1 single and double mutants. Root angles were determined as the deviation from 0° representing complete re-orientation to the vertical and grouped in 12 sectors of 30°. Bars represent relative numbers of roots as percentage of the total (n). J, inflorescence of 6-week-old Col-0, aux1–7, mips1-2, and mips1 aux1 double mutant.

Root cap columella cells are the sites for root gravity perception (35). Amyloplasts in columella cells sediment to the direction of gravity, which initiates an undefined signaling cascade that eventually directs auxin flux toward the lower side of the root presumably through PIN3 and AUX1 (36–38). Auxin in the lower side of the root can be redistributed to the elongation zone by PIN2, where it inhibits cell elongation and leads to root bending toward the gravity vector (36, 39, 40). We first checked whether starch granules are distorted in mips1. Staining with the Lugol's solution could detect starch granules in both wild type and mips1-2 root columella cells, with a smaller region stained in mips1-2 (Fig. 5, C–F), suggesting that the root cap columella cell identity might not have been changed, and gravity sensing may still be normal in mips1-2. Nonetheless, mips1 mutant roots had distorted root cap organization. Compared with the clear three-layered columella cells in the wild type root cap (Fig. 5G), both the shape and the alignment of these cells in mips1-2 are irregular, and no single recognizable columella cell layer could be identified (Fig. 5H). The severity of these cell-patterning defects in the root cap can be significantly mitigated by exogenous inositol or inositol 1-phosphate (supplemental Fig. S5), although no significant restoration of root gravitropism by inositol feeding was found under the current experimental conditions (supplemental Fig. S6).

Because the auxin transporters AUX1 and PIN2 both are involved in gravity response, to investigate the extent to which the gravitropism alteration in mips1-2 is contributed by PIN2 or AUX1, we compared pin2 (eir1) or aux1 single and pin2 (eir1) mips1-2 or aux1 mips1-2 double mutants for their root curvature response (Fig. 5I). Although eir1 seedlings had a more severe defect in the assay than mips1-2, no significant difference was observed between eir1 and eir1 mips1-2 double mutant (p value obtained from Mann-Whitney, two-tailed nonparametric test was 0.128, n = 105), indicating that MIPS1 and PIN2 may act in the same pathway, and the gravitropic defect in root bending in mips1-2 was largely caused by PIN2 dysfunction. On the contrary, aux1 and aux1 mips1-2 differed significantly from each other (p = 0.00013, n = 105). Although aux1 is more agravitropic than mips1-2, surprisingly, aux1 mips1-2 double mutant exhibited a gravitropic response similar to the mips1-2 single mutant (p = 0.052, n = 105), suggesting that the mips1 mutation partially suppressed aux1 agravitropic response. Therefore, AUX1 and MIPS1 may act in distinct pathways in gravitropism, although the phenotypes of the respective mutants are partly overlapping. In addition, the aux1 mips1-2 double mutant has greatly reduced fertility (silique length), although no difference was observed among wild type, aux1, mips1-2, eir1, and eir1 mips1-2 (Fig. 5J and data not shown), indicating that AUX1 and MIPS1 may act in distinct pathways and in the mips1-2 mutant background, AUX1-mediated auxin influx becomes limiting for fertility.

Altered Auxin Transport and Response in mips1 Mutants

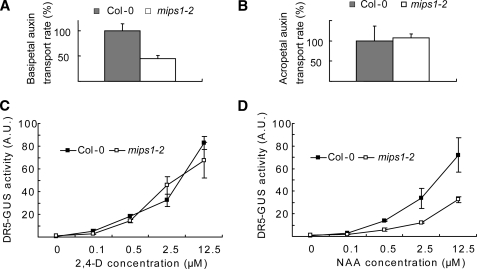

The various auxin-related phenotypes of mips1 mutants described above suggest that the mutants may have changed auxin responsiveness or transport. We first measured auxin transport rates in mips1 roots. Although no significant difference in acropetal auxin transport was detected between the wild type and mips1-2 (Fig. 6B), basipetal auxin polar transport rate in mips1-2 roots was less than half that in wild type roots (Fig. 6A). To determine whether the mips1-2 mutants exhibit altered responses to auxin, mutant and wild type seedlings with DR5-GUS transgene were treated with different concentrations of 2,4-D or naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). No clear differences in DR5-GUS induction by 2,4-D were observed between wild type and mips1-2, but we found that mips1-2 mutant exhibited reduced induction of reporter gene by NAA (Fig. 6, C and D). 2,4-D is a relatively poor substrate for auxin efflux carrier, although NAA can freely diffuse into the cell independent of auxin influx carrier; therefore, reduced response to NAA but intact response to 2,4-D induction of DR5-GUS in mips1-2 may suggest that rather than changed auxin response, mips1-2 may be more likely impaired in its auxin efflux capacity.

FIGURE 6.

Impaired polar auxin transport and altered auxin response in mips1. A and B, relative rate of basipetal (A) and acropetal (B) auxin transport in mips1 roots. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3). C and D, DR5-GUS activity (A.U., arbitrary units) in Col-0 and mips1-2 seedlings treated with different concentrations of 2,4-D (C) or NAA (D). Five-day-old seedlings were treated with the indicated concentrations of auxins for 24 h before extracting the protein for GUS assay. Data are means ± S.E. (n = 3).

mips1 Mutants Exhibit Defects in Vesicle and Plasma Membrane Protein Trafficking

Previous studies in animal cells have documented the pivotal role of phosphatidylinositides in many membrane trafficking events, including vesicle targeting, interactions between the membrane and the cytoskeleton, and membrane budding and fusing (2, 41). Given that auxin influx and efflux carriers undergo vesicle-dependent trafficking (42, 43) and the fact that mips1 has reduced phosphatidylinositol contents (Fig. 2J), it is likely that impaired vesicle trafficking might underlie the polar auxin transport-related phenotypes in mips1. We thus investigated the possible impacts of mips1 mutations on vesicle trafficking.

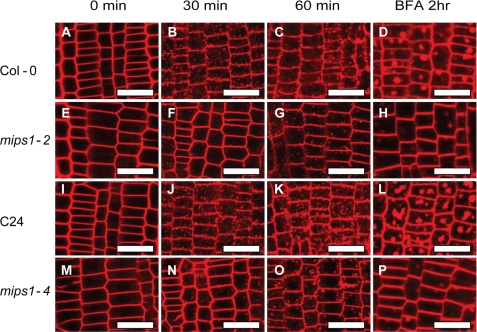

The fluorescent dye FM4-64 can stain plasma membrane and has been used as a marker to monitor the endocytosis of plasma membrane. Thirty minutes after treatment, wild type root tips showed clear internalization of the dye (Fig. 7, B and J). However, no apparent accumulation of the dye was observed in mips1 roots (Fig. 7, F and N). One hour after the treatment, when large chunks of fluorescence were evident in the wild type (Fig. 7, C and K), mips1 started to show limited cytosolic endosome fluorescence (Fig. 7, G and O). Therefore, mips1 mutants have significantly slower endocytosis rates.

FIGURE 7.

Impaired vesicle trafficking in mips1 mutants. Shown are fluorescence images of FM4-64 uptake in the root tips of Col-0 (A–D), mips1-2 (E–H), C24 (I–L), and mips1-4 (M–P). Roots of 5-day-old seedlings were incubated in a half-strength MS medium containing 5 μm FM4-64 for 5 min on ice. Pictures were taken immediately or after 30 or 60 min of incubation in a half-strength MS solution at 22 °C. For BFA-induced compartments, 5-day-old seedlings were incubated in 50 μm BFA for 2 h before incubation in 50 μm BFA plus 5 μm FM4-64 for 30 min. Pictures were taken immediately after the FM4-64 treatment. More than 30 seedlings were examined for each treatment. Bars, 25 μm.

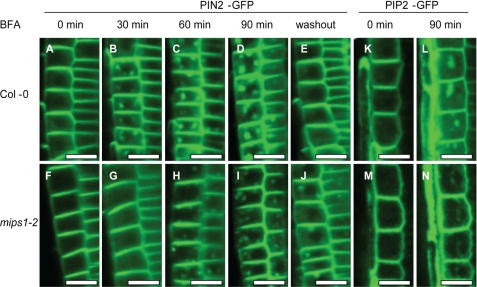

BFA inhibits vesicle trafficking to and from the Golgi/TGN and induces the formation of BFA compartments (44). Consistent with its slowed endocytosis rate, mips1 mutants also exhibited reduced BFA compartmentalization (Fig. 7, D, H, L, and P). The slower rate of endocytosis in mips1 mutants may affect the trafficking of membrane proteins, including auxin carriers. To test this, we introduced the PIN2-GFP protein fusion construct into the mips1-2 mutant plants by crossing with the PIN2-GFP line (22). Although 30 min of BFA treatment induces the formation of clear BFA compartments in the wild type seedlings (Fig. 8B), no clear BFA compartments were formed in the mips1-2 mutant (Fig. 8G). With longer BFA treatment, one or two large BFA compartments were observed in the wild type (Fig. 8, C and D). Under the same conditions, smaller and more numerous BFA compartments were detected in mips1-2 mutants than in the wild type (Fig. 8, H and I). Two hours after washout of BFA, PIN2 resumed its asymmetric localization in the wild type (Fig. 8E), whereas in mips1-2 mutants, a certain amount of PIN2 remained in the cytosol (Fig. 8J). To test whether the mips1 mutation affects the trafficking of other membrane proteins, we checked another plasma membrane protein PIP2-GFP (23) in mips1-2. Similar to PIN2 protein, the BFA-induced compartmentalization of PIP2 protein was also impaired in mips1-2 (Fig. 8, K–N). Similar BFA compartment results have been reported by Sieburth et al. (45) in ARF-GAP mutant sfc for PIN1, suggesting that mips1-2 mutant may have suppressed scarface activity and consequently impaired endocytosis of PIN proteins. However, it is also possible that a step(s) before GNOM ARF-GEF may be affected in mips1 that leads to the altered BFA compartment.

FIGURE 8.

Altered sorting of membrane proteins in mips1 mutants. A–J, PIN2 localization in root tips of Col-0 (A–E) and mips1-2 (F–J). PIN2-GFP in root epidermal and cortical cells of Col-0 (A) and mips1 (F) without BFA treatment. PIN2 accumulation after 30, 60, and 90 min of BFA treatment in Col-0 (B–D) and mips1 (G–I). Note that as compared with one or two large PIN2 compartments in the Col-0 after 90 min of BFA treatment, multiple smaller PIN2 compartments are evident in mips1. Two hours after BFA washout, PIN2 polar localization is reestablished in Col-0 (E), although considerable amount of PIN2 is still in the cytosol in mips1-2 (J). K–N, PIP2 localization in root tips of Col-0 (K and L) and mips1-2 (M and N). PIP2-GFP in epidermal cells of Col-0 (K) and mips1-2 (M) without BFA treatment. PIP2 accumulation after 90 min of BFA treatment in Col-0 (L) and mips1-2 (N). More than 30 seedlings were examined for each treatment. Bars, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

Inositol and its derivatives are essential for numerous cellular processes such as chromatin remodeling, gene regulation, mRNA export, hormone signaling, vesicle trafficking, stress adaptation, and membrane and cell wall biogenesis (1–4). As a result, defects in MIPS or lack of inositol may have dramatic impacts on cellular organisms. For instance, the Trypanosoma brucei mips mutant is nonviable (46), and the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ino1 mutant is inositol auxotrophic (47); yet, it is unclear which process is primarily responsible for the lethality in these unicellular organisms. In this study, we isolated Arabidopsis MIPS1 null mutants that allow us to reveal the in vivo role of this group of highly conserved enzymes in regulating vesicle trafficking and pattern development in a higher eukaryote.

MIPS1 Is Required for Multiple Developmental Processes

Null mips1 mutants exhibited multiple defects in embryogenesis (Fig. 3, C–H), cotyledon vein patterning (Fig. 4), epidermal cell division (supplemental Fig. S3, B–D), root growth and gravitropism (Fig. 2, H and I, and Fig. 5, A, B, and I), root cap cell patterning (Fig. 5, C–H), apical dominance (supplemental Fig. S3A), and auxin response (Fig. 6, C and D). Similar to some of the phenotypes we observed, smaller seedling size, wrinkled seeds, irregular cotyledons, altered vascular patterning, and altered epidermal cell division in mips1 have also been reported recently together with its compromised cell death suppression and basal immunity (16, 18). The maize low phytic acid mutant lpa241 with a reduced MIPS transcript level caused by an unknown epigenetic mutation(s) also exhibits defects related to embryo development such as displacement of the scutellum and altered symmetry (13). Transgenic potato plants expressing antisense MIPS have altered leaf morphology and reduced apical dominance (15). In addition, RNA interference silencing of soybean GmMIPS1 leads to aborted seed development (14). Consistent with this, mutants in inositol polyphosphate or phosphatidylinositol metabolism also exhibit defects in vein formation, gravitropic response, or auxin response (48, 49). Our current genetic study of the MIPS1 gene, together with previous gene expression studies, demonstrate that de novo biosynthesis of inositol is essential for normal embryo development and seedling growth. For this reason, MIPS may not be a good target for engineering low phytate crops.

There are some intriguing observations from mips1 mutants. First, some of these defects appear to occur at specific developmental stages. For instance, the defects in embryos were detected relatively late in embryogenesis when the MIPS1 gene expression starts to increase (supplemental Fig. S4). Perhaps at these stages, the demand for de novo inositol biosynthesis from MIPS1 is the highest. The absence of clear defects during early embryogenesis and the relatively normal epidermal cell proliferation and stomatal patterning in rosette leaves suggest that MIPS2, and perhaps also MIPS3, may play a redundant role during early embryogenesis. Second, although the MIPS1 promoter GUS was expressed mainly in the root vasculature (Fig. 1, B–D), reduced basipetal rather than acropetal auxin transport was detected in mips1 roots (Fig. 6, A and B). This may be explained by the transport of MIPS1 product from vasculature to out layers in root. Mitsuhashi et al. (27) also showed that MIPS1 protein primarily located in endosperm but not in embryo, although mips1 mutant exhibits severe defects in embryo development (Fig. 3, B, D, F, and H). Finally, whereas exogenous inositol or inositol 1-phosphate partially rescues some of the phenotypes of mips1 (Fig. 2, H and I, and supplemental Fig. S5) it could not rescue the defects in auxin response in the gravitropism in roots (supplemental Fig. S6). The failure of rescue of this defect by inositol feeding may reflect the limitation of the particular experimental conditions where these assays were conducted or, alternatively, MIPS1 might have unknown functions independent of inositol biosynthesis. Interestingly, a recent study also reported that exogenous inositol could not substitute the loss of MIPS1 gene in T. brucei (46).

Altered Trafficking of PIN Proteins in mips1 Mutants

Although a role of MIPS1 in vesicular trafficking has not previously been reported in any organism, phosphatidylinositides are widely known for their involvement in vesicular trafficking. Specific phosphatidylinositides are proposed to define the identity of discrete vesicle trafficking organelles. The phosphorylation status of the polar heads of phosphatidylinositides in specific intracellular locations may signal either the recruitment or the activation of proteins essential for vesicular transport (50). For example, plasma membrane is specifically enriched in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, and endosomes are enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate, whereas phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is the predominant Golgi membrane marker (51). Thus, the significantly reduced levels of major phosphatidylinositols in mips1 mutants (Fig. 2J) (16) may have important implications for vesicle trafficking. It is also tempting to speculate that certain vesicle trafficking processes may be specifically affected due to the characteristic changes in phosphatidylinositol species (Fig. 2J). Indeed, the mips1 mutants have a slowed rate of FM4-64 internalization and are defective in BFA compartmentalization (Fig. 7, A–P).

Consistent with impaired vesicle trafficking in mips1, the BFA compartment of PIN2 proteins (Fig. 8, A–J) is similar to that of PIN1 protein in the sfc/van3 mutant (45). SFC/VAN3 encodes an ADP-ribosylation factor-guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase)-activating protein (ARF-GAP) that bears a phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-binding pleckstrin homology domain and is located in the TGN (52). AtSNX1, a component of retromer complex that retrieves protein from prevacuole compartment to the TGN, contains a phosphatidylinositol-binding PX domain (53) and co-localizes with a marker for phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate-enriched membrane subdomains (54). Therefore, the changed sorting of PIN2 protein in mips1 is most likely linked to the significantly reduced content of phosphatidylinositols, which may disrupt the homeostasis among the phosphatidylinositide species and consequently either increased sorting to vacuole or decreased retrieval to TGN or both. Indeed, the regulation of SFC/VAN3 by phosphatidylinositide has recently been reported in Arabidopsis by genetic analysis of sfc/van3 and inositol polyphosphate 5′-phosphatases mutants cvp2 and cvl1 (55, 56).

It worth noting that although mips1 mutant has changed sorting of both PIN2 and PIP2 protein, it does not necessarily mean that this mutant has changed sorting of all plasma membrane proteins. Unlike PIN2 and PIP2, AUX1 sorting to vacuole is not regulated by light (57), and our double mutant analyses also indicate that MIPS1 and AUX1 act in distinct pathways (Fig. 5, I and J), suggesting AUX1 protein sorting may not be altered in the mips1 mutant. We also cannot exclude the possibility that mips1 may be defective in auxin response independent of auxin transport, because inositol hexakisphosphate (phytate) might act as a cofactor of auxin receptor TIR1 (5), although supplementing the growth media or spraying with phytate could not rescue the mips1 mutant phenotypes (data not shown). Notably, our discovery of MIPS regulation of vesicle trafficking and protein sorting in plants may be applicable to other eukaryotic systems as well. In fact, an inositol monophosphatase that could function in both inositol biosynthesis and cycling was recently found to regulate the localization of synaptic components in the Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system (58), demonstrating that inositol is also required for protein trafficking in animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jian Xu and Ben Scheres for the PIN2-GFP line and Dr. Thomas Guilfoyle for the DR5-GUS line. We thank Dr. Ming Chen for providing ER and Golgi cyan fluorescent protein marker plasmids, Dr. Howard Berg for helping with the microscopy work, and Dr. Mark Running for comments on the experiments. The Kansas Lipidomics Research Center at the Kansas State University assisted with the phospholipid analysis.

This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant 0446359 (to L. X.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

- MIPS

- myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- TGN

- trans-Golgi network

- ARF

- ADP-ribosylation factor

- GAP

- guanosine triphosphatase-activating protein

- MS

- Murashige and Skoog

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- NAA

- naphthalene acetic acid

- 2,4-D

- 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- WT

- wild type

- GUS

- β-glucuronidase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michell R. H. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin T. F. (1998) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 14, 231–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth M. G. (2004) Physiol. Rev. 84, 699–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevenson J. M., Perera I. Y., Heilmann I., Persson S., Boss W. F. (2000) Trends Plant Sci. 5, 252–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan X., Calderon-Villalobos L. I., Sharon M., Zheng C., Robinson C. V., Estelle M., Zheng N. (2007) Nature 446, 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagy R., Grob H., Weder B., Green P., Klein M., Frelet-Barrand A., Schjoerring J. K., Brearley C., Martinoia E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33614–33622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong L., Lee Bh., Ishitani M., Lee H., Zhang C., Zhu J. K. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1971–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson D. E., Rammesmayer G., Bohnert H. J. (1998) Plant Cell 10, 753–764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lemtiri-Chlieh F., MacRobbie E. A., Webb A. A., Manison N. F., Brownlee C., Skepper J. N., Chen J., Prestwich G. D., Brearley C. A. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10091–10095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raboy V. (2003) Phytochemistry 64, 1033–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi J., Wang H., Schellin K., Li B., Faller M., Stoop J. M., Meeley R. B., Ertl D. S., Ranch J. P., Glassman K. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 930–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewus F. A., Murthy P. P. (2000) Plant Sci. 150, 1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilu R., Landoni M., Cassani E., Doria E., Nielsen E. (2005) Crop Sci. 45, 2096–2105 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunes A. C., Vianna G. R., Cuneo F., Amaya-Farfán J., de Capdeville G., Rech E. L., Aragão F. J. (2006) Planta 224, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller R., Brearley C. A., Trethewey R. N., Muller-Rober B. (1998) Plant J. 16, 403–410 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue J. L., Alford S. R., Torabinejad J., Kerwin R. E., Nourbakhsh A., Ray W. K., Hernick M., Huang X., Lyons B. M., Hein P. P., Gillaspy G. E. (2010) Plant Cell 22, 888–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy A. M., Otto B., Brearley C. A., Carr J. P., Hanke D. E. (2008) Plant J. 56, 638–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng P. H., Raynaud C., Tcherkez G., Blanchet S., Massoud K., Domenichini S., Henry Y., Soubigou-Taconnat L., Lelarge-Trouverie C., Saindrenan P., Renou J. P., Bergounioux C. (2009) PLoS ONE 4, e7364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welti R., Li W., Li M., Sang Y., Biesiada H., Zhou H. E., Rajashekar C. B., Williams T. D., Wang X. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 31994–32002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Men S., Boutté Y., Ikeda Y., Li X., Palme K., Stierhof Y. D., Hartmann M. A., Moritz T., Grebe M. (2008) Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 237–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rashotte A. M., Brady S. R., Reed R. C., Ante S. J., Muday G. K. (2000) Plant Physiol. 122, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J., Scheres B. (2005) Plant Cell 17, 525–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutler S. R., Ehrhardt D. W., Griffitts J. S., Somerville C. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3718–3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kutter C., Schöb H., Stadler M., Meins F., Jr., Si-Ammour A. (2007) Plant Cell 19, 2417–2429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishitani M., Xiong L., Stevenson B., Zhu J. K. (1997) Plant Cell 9, 1935–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson M. D., Sussex I. M. (1995) Plant Physiol. 107, 613–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsuhashi N., Kondo M., Nakaune S., Ohnishi M., Hayashi M., Hara-Nishimura I., Richardson A., Fukaki H., Nishimura M., Mimura T. (2008) J. Exp. Bot. 59, 3069–3076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmermann P., Hirsch-Hoffmann M., Hennig L., Gruissem W. (2004) Plant Physiol. 136, 2621–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lackey K. H., Pope P. M., Johnson M. D. (2003) Plant Physiol. 132, 2240–2247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M., Han G., Dietrich C. R., Dunn T. M., Cahoon E. B. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 3576–3593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeng Q., Wang X., Running M. P. (2007) Plant Physiol. 143, 1119–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alonso J. M., Stepanova A. N., Leisse T. J., Kim C. J., Chen H., Shinn P., Stevenson D. K., Zimmerman J., Barajas P., Cheuk R., Gadrinab C., Heller C., Jeske A., Koesema E., Meyers C. C., Parker H., Prednis L., Ansari Y., Choy N., Deen H., Geralt M., Hazari N., Hom E., Karnes M., Mulholland C., Ndubaku R., Schmidt I., Guzman P., Aguilar-Henonin L., Schmid M., Weigel D., Carter D. E., Marchand T., Risseeuw E., Brogden D., Zeko A., Crosby W. L., Berry C. C., Ecker J. R. (2003) Science 301, 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winter D., Vinegar B., Nahal H., Ammar R., Wilson G. V., Provart N. J. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benková E., Michniewicz M., Sauer M., Teichmann T., Seifertová D., Jürgens G., Friml J. (2003) Cell 115, 591–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blancaflor E. B., Fasano J. M., Gilroy S. (1999) Adv. Space Res. 24, 731–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R., Guan C., Boonsirichai K., Masson P. H. (2002) Plant Mol. Biol. 49, 305–317 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ottenschläger I., Wolff P., Wolverton C., Bhalerao R. P., Sandberg G., Ishikawa H., Evans M., Palme K. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2987–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friml J., Vieten A., Sauer M., Weijers D., Schwarz H., Hamann T., Offringa R., Jürgens G. (2003) Nature 426, 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swarup R., Friml J., Marchant A., Ljung K., Sandberg G., Palme K., Bennett M. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 2648–2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muday G. K., DeLong A. (2001) Trends Plant Sci. 6, 535–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin H. L., Janmey P. A. (2003) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65, 761–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geldner N., Anders N., Wolters H., Keicher J., Kornberger W., Muller P., Delbarre A., Ueda T., Nakano A., Jürgens G. (2003) Cell 112, 219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinmann T., Geldner N., Grebe M., Mangold S., Jackson C. L., Paris S., Gälweiler L., Palme K., Jürgens G. (1999) Science 286, 316–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nebenführ A., Ritzenthaler C., Robinson D. G. (2002) Plant Physiol. 130, 1102–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sieburth L. E., Muday G. K., King E. J., Benton G., Kim S., Metcalf K. E., Meyers L., Seamen E., Van Norman J. M. (2006) Plant Cell 18, 1396–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin K. L., Smith T. K. (2006) Mol. Microbiol. 61, 89–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Culbertson M. R., Donahue T. F., Henry S. A. (1976) J. Bacteriol. 126, 232–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li G., Xue H. W. (2007) Plant Cell 19, 281–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carland F. M., Nelson T. (2004) Plant Cell 16, 1263–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Camilli P., Emr S. D., McPherson P. S., Novick P. (1996) Science 271, 1533–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. (2006) Nature 443, 651–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koizumi K., Naramoto S., Sawa S., Yahara N., Ueda T., Nakano A., Sugiyama M., Fukuda H. (2005) Development 132, 1699–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanoosthuyse V., Tichtinsky G., Dumas C., Gaude T., Cock J. M. (2003) Plant Physiol. 133, 919–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kleine-Vehn J., Leitner J., Zwiewka M., Sauer M., Abas L., Luschnig C., Friml J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17812–17817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carland F., Nelson T. (2009) Plant J. 59, 895–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naramoto S., Sawa S., Koizumi K., Uemura T., Ueda T., Friml J., Nakano A., Fukuda H. (2009) Development 136, 1529–1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laxmi A., Pan J., Morsy M., Chen R. (2008) PLoS ONE 3, e1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanizawa Y., Kuhara A., Inada H., Kodama E., Mizuno T., Mori I. (2006) Genes Dev. 20, 3296–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.