Abstract

Metallonucleases conduct metal dependent nucleic acid hydrolysis. While metal ions serve in multiple mechanistic capacities in these enzymes, precisely how the attacking water is activated remains unclear for those lacking an obvious general base. All arguments hinge on appropriate pKa’s for active site moieties very close to this species, and measurement of the pKa of a specific water molecule is difficult to access experimentally. Here we describe a computational approach for exploring the local electrostatic influences on the water-derived nucleophile in metallonucleases featuring the common PD…(D/E)xK motif. We utilized UHBD to predict the pKa’s of active site groups, including that of a water molecule positioned to act as a nucleophile. The pKa of a Mg(II)-ligated water molecule hydrogen bonded to the conserved Lys70 in a Mg(II)-PvuII enzyme complex was calculated to be 6.5. The metal and the charge on the Lys group were removed in separate experiments; both resulted in the elevation of the pKa of this water molecule, consistent with contributions from both moieties to lowering this pKa. This behavior is preserved among other PD…(D/E)xK metallonucleases. pKa’s extracted from the pH dependence of the single turnover rate constant are compared to previous experimental data and the above predicted pKa’s.

INTRODUCTION

Ranging from the degradative activity of restriction enzymes to the initiating reaction in recombination, the cleavage of phosphodiester bonds, producing monoester and alcohol termini, is a reaction crucial to the processing of DNA [1]. Most of these nucleases are metal-ion dependent, relying principally on Mg(II) as a cofactor. Extensive X-ray crystallographic studies reveal common structural themes. The most obvious is a cluster of acidic residues which ligate one but often two metal ions (Fig. 1) [2]. Indeed, mutation of these groups to Ala or a similar residue renders metallonucleases inactive [3]. Subsequent metal ion binding studies confirm the importance of these groups as metal ion ligands [4].

Fig. 1.

A proposed general two-metal mechanism for a metal-dependent nuclease. In the PD…(D/E)xK enzymes, a conserved Lys is located near the attacking water molecule (bold). X− refers to the uncertain means by which the attacking water molecule is activated. In proposed two metal ion mechanism models, metal ion A ligates the scissile phosphate, the attacking water molecule, an additional water molecule and at least one acidic group. Metal ion B also interacts with the DNA and at least one acidic group, and is proposed to be involved in coordinating the water molecule which donates a proton to the leaving group ( ).

).

Common among metallonucleases is the PD…(D/E)xK motif, which in addition to the acidic groups mentioned above also features a conserved active site Lys (K) group [2]. Crystal structures of no fewer than 20 metallonucleases feature this motif. These include transposase Tn7 (TnsA), Hjc resolvase, MutH, λ-exonuclease, RecB, and many restriction enzymes [2]. Mutagenesis of this residue to Ala, Gln or even Arg reduces activity by many orders of magnitude [3, 5].

Also critical to the mechanism is a metal-ligated water molecule that is strategically positioned to attack the scissile phosphate of DNA. Precisely how this water molecule is activated remains enthusiastically debated. The most widely discussed proposal for nucleophile activation involves the coordinating metal ion [6]. Many metal ions lower the pKa of water [7], thus increasing the concentration of hydroxide at assay pH. For flap endonuclease [8] and the hammerhead ribozyme [9], the pH dependence of cleavage rate constants in the presence of various metal ion cofactors support this proposal. The pKa of a metal-ligated water molecule depends very strongly on the metal ion in question. For metal ions like Zn(II), which is a typical center for artificial nucleases [10], the pKa is low enough for sufficient hydroxide to form at neutral pH to catalyze the reaction at a reasonable rate (9 in bulk solution). But for Mg(II), the native cofactor for most protein metallonucleases, the pKa for this bulk species is 11.4 [7], much too high to significantly populate hydroxide near neutral pH. This suggests that either this proposal is incorrect, or that there are other groups that stabilize the nucleophile. In the PD…(D/E)xK enzymes, the highly but not absolutely conserved Lys is an obvious candidate (Fig. 1). Lying very close to the nucleophilic water molecule in the active sites of these enzymes, such a role for this residue has been proposed [11]. The typical pKa of around 10 makes this plausible.

The most convincing support for any nucleophile activation proposal would be the direct measurement of active site group pKa’s via pH titrations. Indeed, this is routine for small, well behaved protein systems [12] but is not as feasible for larger systems. For this reason, we apply computational methods to understand the ionization behavior of metallonuclease active site groups. Theoreticians have developed a number of tools for this purpose [13–15]. Most involve solving a form of the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation using the finite difference method. Indeed, computational chemists have used small model proteins to illustrate that this approach yields accurate pKa’s [16], even if they are unusual [17, 18].

Of particular interest here is the application of pKa prediction to test proposed mechanisms. In beta lactamase, Lys73 has been proposed to be a general base. However, its pKa was calculated to be 10, and NMR data are also consistent with this, indicating that this is unlikely [19]. Recently, the PB equation was applied to understand the low pKa of an active site Cys (3.5) in glutaredoxin [20]. These studies illustrate that one can use computational approaches to understand the ionization behavior of mechanistically relevant active site groups.

An advantage of a computational approach is that it is possible to characterize the ionization behavior of explicitly defined water molecules and reciprocal effects with nearby protein groups. For example, the pKa of a copper-ligated water in the active site of cytochrome c oxidase was successfully predicted [21]. The pKa of Zn(II)-bound water in carbonic anhydrase II and the effect of nearby groups on its ionization behavior has also been recently examined [22]. While environmental parameters such as dielectric constant and ionic strength influence actual pKa values [16, 23], they do not obscure the importance of local interactions. Finally, this approach to examining nucleophilic water pKa’s permits the analysis of any system for which there is a quality crystal structure; in this fashion, general patterns can be detected.

In this study, experimental and computational techniques are combined to examine the utility of pKa predictions in probing metallonuclease mechanism.

THEORY AND EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Chelex resin was purchased from Biorad (Hercules, CA). Puratronic MgCl2 was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Concentrations of stock solutions were determined by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy using a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 700 spectrophotometer. All buffers were applied to a Chelex column to remove adventitious metal ions. Subsequent pH adjustments were made with metal-free nitric acid. All solutions were determined by atomic absorption spectroscopy to be metal-free to the limits of detection [24].

Preparation of PvuII Endonucleases

Purification of PvuII endonuclease was accomplished using phosphocellulose chromatography and heparin sepharose affinity chromatography as previously described [25]. Adventitious metal ions were removed via exhaustive dialysis against metal-free buffer [26]. Apoenzyme was quantitated using ε280 = 36,900 M−1cm−1 for the monomer subunit and handled with metal-free sterile pipet tips and sterile plasticware to prevent contamination.

The Theory and Methodology of pKa Predictions

An electrostatics-based computational methodology implemented in the University of Houston Brownian Dynamics (UHBD v. 5.1) program [14, 16] was used to predict pKa values of all ionizable groups and molecules in the type II restriction endonuclease PvuII. UHBD is used to compute the electrostatic potential and the electrostatic free energy for a given charge distribution in an arbitrary dielectric medium by solving Poisson-Boltzmann equation using a finite-difference method. In this approach, each ionizable group is initially assigned to a starting or model pKa value that represents the pKa of that group in solution. For amino acid residues, literature pKa’s for the sidechains of free amino acids in aqueous solution are used. For Mg(II)-ligated water molecules, the experimentally determined value of 11.4 for Mg(II) in bulk water was used as the starting or model pKa [7]. According to a thermodynamic cycle of ionization in solution and in a protein, prediction of the apparent pKa value of an ionizable group in the protein environment is computed from the difference in electrostatic free energy (ΔΔG) for protonating such a group in solution vs. in its environment in the protein:

| (1) |

where ΔGel is the electrostatic free energy difference for ionization of a given site in a molecule in the solution and in the protein with all other groups in their neutral state. The intrinsic pKa is defined by the equation

| (2) |

where pKa model is the starting pKa value, γ is −1 for an acidic group and +1 for a basic group. The electrostatic work for the ionization is calculated by use of the linearized Poisson-Boltzmann equation implemented in UHBD. The determination of pKa,intrinsic consists of two electrostatic contributions. One is the desolvation energy when the ionizable group is transferred from bulk solution to its environment in the protein, the latter of which exhibits a low dielectric environment. The other contribution is from the ionization energies assuming that all of the other titratable groups are neutral. The electrostatic energy is determined by the interaction with all of the background charges in the protein when all amino acids are in their neutral state.

In reality, of course, the protein has multiple titratable sites, so pKa intrinsic is not equal to pKa apparent because all other ionizable residues will not be neutral. Therefore, to calculate the electrostatic energy from the charge-charge interaction between the given ionizable group and all other titratable groups, it is essential to evaluate the ionization states of each site at various pH values. This multiple titration state problem requires the evaluation of numerous protonation patterns. This problem can be treated by a Monte Carlo method, which samples combinations of protonation states using a Metropolis algorithm, resulting in a Boltzmann distribution of protein protonation states and their associated electrostatic free energies. The Monte Carlo method provides a list of pKa apparent and pKa intrinsic values for all ionizable groups in the protein. Since the number of protein ionization states is huge (on the order of 2N, where N is the number of ionizable groups in the protein system), it is difficult to adequately sample the possibilities. Therefore, a different approach was also taken to address this coupled titration problem, which was a hybrid divide-and-conquer Tanford-Roxby method [27]. In this approach, titratable residues that strongly interact are put in the same cluster and the coupled titration problem is solved exactly within each cluster, supplemented by an inter-cluster interaction term.

The single site approach was used to describe the ionization in the titratable group upon protonation or deprotonation. This approach neglects the fact that the partial charge distribution changes upon ionization and treats ionization by adding or subtracting a full charge to one atomic position in the group as previously demonstrated [14]. Ionizable groups were switched “off” by changing the atom type to nonionizable. Interaction potentials were extracted from the output file pkaS-potential. Due to the somewhat rough description of ionization in the single site model and the neglect of conformational flexibility, we believe that the error in the pKa prediction of active site residues is on the order of one pH unit [14] but has not been determined for metal bound waters.

Parameters Applied in the pKa Predictions

Atomic partial charges and radii from the CHARMM22 force field [28] were used in all calculations. The aqueous milieu was modeled using the dielectric constant. Solvent and protein dielectric constants were 80 and 20, respectively. The ionic strength (150 mM), ionic radius (2 Å), surface probe radius (1.4 Å), and temperature (293 K) were chosen to reflect the experimental conditions.

Preparation of Protein Structures

All pKa calculations were performed on PvuII X-ray crystal structures obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Structures were visualized with SwissPDB Viewer v. 3.7 [29] (http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/). Calculations on the free enzyme were performed without water molecules or DNA unless otherwise specified. Hydrogens were added to the protein structures with the HBUILD module of the CHARMM program in order to generate the reference state for pKa predictions. In this state, every ionizable residue is set up in its neutral state. Hydrogens added via HBUILD/CHARMM in conjunction with the single-site pKa procedure in UHBD undergo a search for optimal placement with respect to hydrogen bonding. For calculations involving Mg(II) or Mn(II), a charge of 2+ and ionic radii of 1.282 or 1.425 Å were utilized, respectively.

Single Turnover Cleavage Assays as a Function of pH

Single turnover DNA cleavage rate constants (kobs) for PvuII restriction endonuclease were obtained discontinuously as a function of pH using PAGE. 300 nM of a 32P-5′-endlabeled, nonselfcomplementary cognate 14 mer duplex [30] was incubated with 2 μM enzyme dimers in a constant ionic strength triple buffer system [31] containing 10 mM Mg(II), 80 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 25 mM NaAc and 25 mM MES. Under these conditions, enzyme concentration is in sufficient excess of substrate for kobs to be independent of enzyme concentration [32]. pH adjustments and measurements were made at 37°C.

Below pH 7.0 and above pH 8.6, time points were obtained via manual quenching with EDTA. A 100 μl reaction volume was prepared containing 300 nM duplex and 10mM Mg(II); a small volume of 5–10 μl enzyme stock in metal-free buffer was added to initiate the reaction.

For reactions conducted between pH 7 and 8.6, reaction samples were collected using a BioLogic SFM-400/QS stopped flow/quench flow apparatus (Molecular Kinetics) run with BioLogic MPS software for Windows v. 2.00. One syringe was loaded with enzyme pre-incubated with reaction buffer containing Mg(II); the second syringe was loaded with DNA pre-mixed with the same reaction buffer. The reaction was initiated by mixing enzyme and DNA from two separate syringes together and quenched by 100 mM EDTA loaded in the third syringe. The final concentration for reactions was 2 μM enzyme and 300 nM DNA. The final collection volume was about 200 μl and 10–12 μl of samples were mixed with stop dye.

Substrates and products were separated by denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel and analyzed using a Storm phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant software v. 5.2.

The data were normalized and fitted to a first order exponential equation. Quantitation of product and substrate gave very similar rate constants. Reactions slow enough to do both manually and by quench flow yielded the same rate constants. More than three trials were performed for each reaction, and the resulting rate constants were averages. At 10 mM Mg(II) and pH 7.5, starting the reaction with enzyme premixed with Mg(II) and metal-free enzyme (Mg(II) loaded with DNA) yielded the same rate constants.

Since the plot of log(kobs) vs. pH for the acidic limb of the pH profile is nonlinear (see Results), the entire range of data was fit to a model involving at least three pKa’s (Scheme 1; K’s are dissociation constants). Since metal ion binding has already been established as involving two ionizations [33], this (most acidic) portion of the profile is represented by one apparent macroscopic pKa1,app, the pKa,app associated with Mg(II) binding (H2M). The second transition involves the proton associated with the general base of the reaction (HN; pKa2). The third (basic) pKa is generally assigned to the protonation of the leaving group (HLG). From this scheme, the following equation can be derived (see Supplemental Material):

| (3) |

where kchem is the chemical cleavage step. Data were fit to eqn. 3 using Kaleidagraph 3.6 software.

Scheme 1.

RESULTS

Prediction of PvuII Active Site pKa’s

While metallonucleases are increasingly studied via computational methods [34], there is little application of pKa prediction to metallonuclease function. For this reason, we chose to initiate pKa calculations on a system which is relatively simple and for which there is experimental data. It would be especially convincing if calculated pKa’s could be applied to rationalize experimental data, providing critical validation for the approach.

A relatively simple pH-dependent behavior of metallonucleases is metal ion binding. In the course of our characterization of metal ion binding by PvuII endonuclease, Glu68 and Asp58 were established as metal ion ligands [4, 33]. These results provide an ideal setting for validating pKa prediction in simulating experimentally characterized solution behavior in metallonucleases.

25Mg NMR experiments have established that the pKa,app of Mg(II) binding for free PvuII endonuclease (i.e., without DNA present) is 6.7 [33]. This value most likely has a number of contributions. However, E68A is the only PvuII active site variant that does not bind Mg(II) or Ca(II) ions [4, 33]. This indicates that the major determinant of the pH dependence of metal ion binding behavior is the ionization of Glu68; therefore if pKa calculations yield reasonable values, we would expect Glu68 to have a pKa near 6.7.

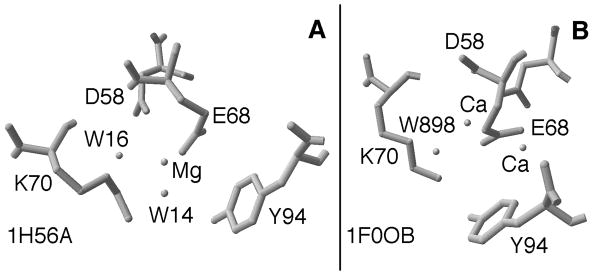

To test this hypothesis, we performed simple pKa calculations on a PvuII structure file. PvuII has been crystallized with two Ca(II) ions and DNA [35] and we work with a derivative of this structure below. However, solution Mg(II) binding studies were conducted in the absence of DNA. Therefore we found it more appropriate to perform these initial calculations with the only published coordinates that contain Mg(II), 1H56. In this structure, there is one Mg(II) per active site in different locations in each subunit. In subunit A, Mg(II) is ligated to Glu68 and Asp58 (Fig. 2A), a position supported by solution thermodynamic studies [4, 33]. In subunit B, the sole Mg(II) ion is ligated by Tyr94, a contact which appears to be less critical for activity [36]. Calculations were therefore confined to subunit A.

Fig. 2.

The active site of (A) apo enzyme subunit A of 1H56 with Mg(II)-ligated water molecules highlighted. Because it required little editing of the file, this structure was used in the first series of calculations. (B) Subunit B of 1F0O with Ca(II) ions and water molecule highlighted. It is upon this structure that the two-metal ion mechanism is proposed [32].

The resulting pKa’s for Asp58 and Glu68 are 4.4 and 6.3, respectively. The pKa for Asp58 is similar to that of the free amino acid (about 4), but the pKa value for Glu68 is elevated relative to the free amino acid (also about 4) and compares very well with the pKa,app for Mg(II) binding (6.7) and is consistent with the experimentally established critical role of this ligand in metal ion binding. Thus pKa calculations in the free enzyme can be used to rationalize experimental data.

Calculation of Metal-Bound Water Molecule pKa’s

The classic proposed mechanism for metal-dependent nucleases involves activation of a water-derived nucleophile. While there are a number of proposals for how this occurs [6], most require unusual pKa’s. Combining the measurement of active site group pKa’s with that of the attacking water itself would be the ideal means to evaluate these proposals.

While the titration of amino acid sidechains can be observed via NMR spectroscopy, the pKa of a crystallographically defined water molecule is not as experimentally accessible. Correlations with pH kinetic rate profiles of metalloenzymes [37] come the closest to estimating these values via experimental techniques. However, calculating water pKa’s and examining the impact of this group on neighboring sidechains has literature precedent [21, 22, 38]. We reasoned that we could use this strategy to understand the local influences on a well-positioned water molecule. In this approach, interpretation does not heavily rely on the accuracy of the pKa value. The emphasis is on the effect of the perturbations (i.e., shifting the water pKa up or down and/or magnitude of interaction potentials).

To understand the influences on the pKa of metal-ligated water molecules, we applied the linearized version of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation to crystallographically determined, Mg(II)-ligated water molecules in multiple PvuII structures. Since Coulomb’s Law dictates that electrostatic forces decrease inversely with the square of the distance [39], the focus is on local influences (3 Å). This is the basis of the rationale for first working with the crystal structure of PvuII endonuclease bound only by Mg(II) (1H56) [36]. In subunit A of this structure, Mg(II) coordinates two water molecules, HOH14 and HOH16, in addition to the aforementioned ligands Glu68 and Asp58. The former water molecule is within hydrogen bonding distance to Lys70 and is in a position analogous to an attacking water in an enzyme-substrate complex (Fig. 2A). The latter water molecule has no additional contacts of interest, is not implicated mechanistically, and thus serves as an important control.

To understand the influences of nearby groups on its pKa, we performed a series of pKa calculations on this and closely related structures. The active site Mg(II) ion was modeled as described in Materials and Methods. Since 11.4 is the established pKa for the deprotonation of a Mg(II)-ligated water in bulk solution [7], this value was used as a starting (model) pKa value for both water molecules in the PvuII active site. By design, this value is influenced by the course of the calculation, that is, local electrostatic effects, as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Table 1, UHBD predicted that HOH16 has a higher pKa (near 14), but the pKa of HOH14 is remarkably lower (6.5; Expt 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Water pKa Predictions for PvuII Endonuclease 1H56a

| Expt | # Mg | HOH14 | HOH16 | K70 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Result | ||||

| 1 | WT | 1 | 6.5 | 14.6 | 14.6 |

| 2 | WT | 0 | > 15 | > 15 | |

| 3 | Lys off | 1 | 9.8 | > 15 | - |

| 4 | WT | 1 | None | None | 9.9 |

Subunit A of this structure. Mg-O (water) distance is 1.9 Å for HOH14 and 2.7 Å for HOH16. The model or starting pKa for Mg(II) ligated water is 11.4, and the model or starting pKa for Lys is 10.4. pKa’s shift from these values as a result of the calculations.

To confirm the electrostatic importance of interactions with the metal ion, the cofactor was removed and the calculation repeated. In the absence Mg(II), the pKa of HOH14 is elevated to 15 (Expt 2, Table 1), even with a starting value of 11.4. This trend holds even if the starting pKa value is set to 12.4 or 13.4 (data not shown).

The predicted pKa of HOH14 suggests that Mg(II) is not the only influence on this pKa. To guide the dissection of the influences on this water molecule, we examined the immediate environment of HOH14. This water molecule is wedged between the Mg(II) ion and Lys70. Indeed, the interaction potential [40] between the water and Lys70 is 3.5 kcal/mol. Expt 3 (Table 1) reveals that without the positive charge on the Lys group, the pKa of HOH14 is raised to nearly 10. Consistent with the interplay of these active site moieties, the pKa of Lys70 is lowered (from 14 to 10) in the absence of that water molecule (Expt 4, Table 1). While there are caveats (see Discussion), these results support the theory that the pKa of a water positioned between Mg(II) and a Lys residue in a PD…(D/E)xK motif metallonuclease is lowered by both moieties to an extent which makes it a plausible nucleophile.

The disadvantage of working with a starting structure that does not have DNA is that metal ions and water molecules are not necessarily aligned as in an enzyme substrate complex. In restriction enzymes, DNA binding is accompanied by global conformational changes [41] which can affect the placement of active site moieties. There are no structures of PvuII bound to DNA and Mg(II) simultaneously. Because it supports DNA binding but not cleavage, Ca(II) [30] is used extensively in metallonuclease-DNA crystal structures [6]. However, PvuII coordinates can be suitably modified from a structure in which the enzyme is bound by DNA (1F0O) [35] and two Ca(II) ions. In this way, we can examine local electrostatic effects in the context of the DNA-bound enzyme conformation. In an effort to better understand the influences on the attacking water pKa and consistent with literature precedent [38], calculations were performed on various modified versions of this structure.

In subunit B of 1F0O, HOH898, which is ligated to Ca(II) and hydrogen-bonded to Lys70 (Fig. 2C), is considered to be the candidate nucleophile. The DNA atoms were removed (see Discussion), and Ca(II) was replaced with Mg(II) at the same location. Since Mg(II) is smaller than Ca(II) (0.65 Å vs. 0.99 Å ionic radius), this substitution effectively extends the water oxygen-metal distance to 2.8 Å (from a typical Mg-O distance of 2.0 Å [42]). The pKa of HOH898 is 9.3 (Expt 1, Table 2). This value is distinctly higher than that observed with Mg(II) and the 1H56 structure, but it is also reasonable given that Mg(II) is placed at the center of a site for the larger Ca(II) ion, placing the smaller ion farther away from the water molecule (2.8 vs. 1.9 Å in 1H56.pdb). To optimize the Ca(II)-H2O geometry for Mg(II)-H2O, HOH898 was shifted closer to metal ion to 2.0 Å, more closely matching the geometry in 1H56. As illustrated in Expt 3, Table 2, the resulting pKa is similar to that obtained with 1H56 (6.4 vs. 6.5). This illustrates the importance of the ligating metal ion and the metal-ligand distance in modulating this pKa.

Table 2.

Summary of water pKa calculations with 1F0Oa

| Expt | Structure | Enzyme | No. metals | Distance Mg-O | Distance Res70-O | pKa Water | pKa Res70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1H56.A | WT | 1 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 6.5 | 14.6 | |

| 1H56.A | K70 off | 1 | 1.9 | 9.8 | |||

| 1 | 1F0O.B | WT | 2 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 9.3 | 12.7 |

| 2 | 1F0O.B | K70 off | 2 | 10.5 | |||

| 3 | 1F0O.Bb | WT | 2 | 2.0 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 10.7 |

| 4 | 1F0O.B | K70 off | 2 | 2.0 | 7.8 | ||

| 5 | 1F0O.A | WT | 2 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 7.4 | >15 |

| 6 | 1F0O.A | K70 off | 2 | 2.6 | 10.5 | ||

The model or starting pKa for water is 11.4; distances are in Angstroms.

Water-metal distance modified as described in the text.

Subunit A of 1F0O.pdb does not feature a water molecule at this location. A Lys70 hydrogen-bonded water molecule was built up artificially based on the geometry of the metal bound water complex in subunit B. A distance of 2.60 Å between the water oxygen and the metal ion was assigned (a reasonable Ca-O distance), and steric clashes were avoided. Finally, Mg(II) parameters were used in the calculation but the Mg(II) was placed at the Ca(II) center. As outlined in Expt 5, Table 2, this geometry results in a pKa of 7.4.

To establish the importance of the Lys group in modulating the pKa of this water molecule, the Lys group in these structures was neutralized. As shown in Expts 2, 4, and 6 of Table 2, this pKa is elevated. The extent to which this occurs varies. The effects in the subunit B structure are similar (ΔpKa ≈ 1.6), even though the Mg-O distances are quite different. In subunit A, where the water site is engineered, the effect is the most dramatic (ΔpKa of 3.1).

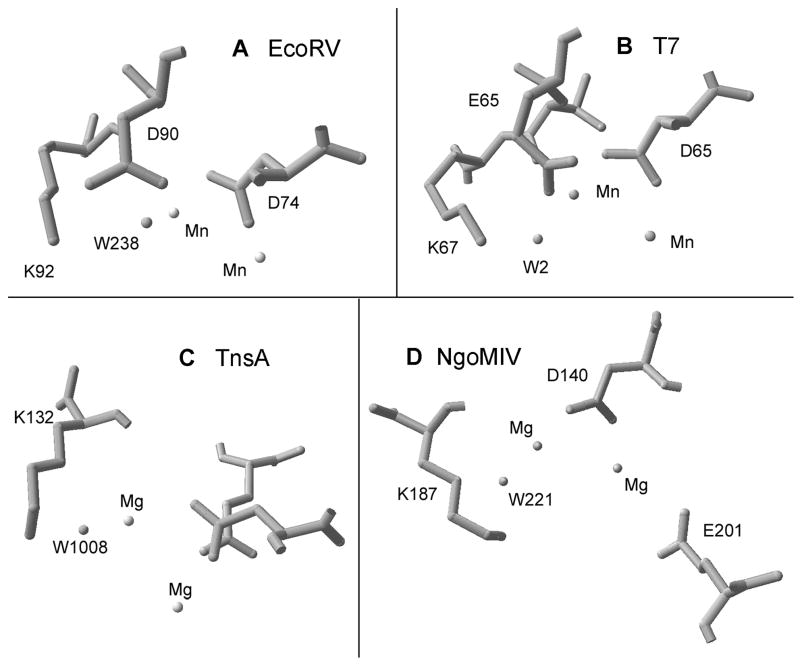

pKa of Other Metal Ligated Waters in PD…(D/E)xK Metallonucleases

To test the generality of the effects on water pKa observed with PvuII endonuclease, this experiment was repeated with the structures of a number of other enzymes which feature a well-positioned, metal-ligated water molecule in a PD…(D/E)xK motif (Fig. 3). Consistent with studies on PvuII endonuclease, all calculations were performed without the DNA present. As summarized in Table 3, while the magnitude of the pKa changes varies, the trend of low pKa’s for metal-ligated waters that are elevated upon removal of the positive charge at Lys is preserved. This is consistent with a role for this conserved Lys in modulating the pKa of the water molecule.

Fig. 3.

Other metallonucleases which feature a conserved Lys group proximal to a metal-ligated water molecule. (A) EcoRV endonuclease (1SX5); (B) T7 endonuclease I (1M0D); (C) TnsA of Tn7 transposase (1F1Z); (D) NgoMIV endonuclease (1FIU).

Table 3.

Summary of Water pKa Calculations for Other Metallonucleases

pH Dependence of Cleavage Activity

It would be useful to compare pKa’s obtained in the absence of DNA with those in its presence. Such an analysis can provide insight into 1) the extent to which DNA affects active site groups and 2) the degree to which the polyanionic effects of DNA are mitigated by well-established screening effects. Since suitable electrostatic modeling of DNA is beyond the scope of this study, we turn instead to a correlative study of the pH dependence of single turnover PvuII cleavage kinetics. This analysis provides apparent titration behavior for the ionizable groups involved in the cleavage reaction. This approach of comparing pKa prediction results with kinetic data has literature precedent [20, 43, 44]. For a couple of related metallonucleases, one limb of the profile has been assigned to the attacking water molecule [8, 37]. Other groups that are responsible for other mechanistic steps (e.g., coordinating required metal ions and protonation of the leaving group) are also represented.

While many classical activity/pH profiles are constructed using steady state data, this approach has fallen out of favor. It is very difficult to clearly interpret these data: While kcat is supposed to represent the chemical step, in reality its value also reflects the rate-limiting step. In the case of many enzymes including metallonucleases, this step is product release [45]. The composition of Km is also complex, comprised of a ratio of rate constants for enzyme-substrate complex formation and breakdown. We have already demonstrated that we can access the chemical step in this system using single turnover kinetics [32], and utilize conditions that make kobs independent of enzyme concentration and thus reflective of species that participate in the chemical step.

As shown in Fig. 4A, a classical bell-shaped curve common to many nucleases was observed. Taking the log of kobs and replotting is very diagnostic for establishing the stoichiometry of the acidic and basic limbs, i.e., how many protons are involved. Separate plots of log(kobs) for the acidic and basic limbs reveals distinct behaviors (Fig. 4B and C). The basic limb is clearly linear and yields a slope of 0.8 consistent with the involvement of one proton. The behavior of the acidic limb is distinctly biphasic, indicating two ionization regimes. Fit of the upper portion (pH 6–7) yields a slope of 1.3. The slope of the lower portion is 2.8, which is a bit higher but similar to the slope of 2.1 previously observed in Mg(II) binding titrations [33]. Given the number of points obtainable in this region, a cautious comparison is reasonable.

Fig. 4.

PvuII single turnover kinetic rate constant as a function of pH. (A) Entire profile fit to equation 3. The resulting pKa’s are 6.1, 7.7, and 7.8. (B) Acid limb plotted as log(kobs). The slopes of the two regions are 2.8 and 1.3. (C) Basic limb plotted as log(kobs). The slope is 0.8. See text for further details.

Since cleavage rates depend on bound Mg(II), which is in turn determined by the ionization states of two of its ligands, the entire profile was fit to a model involving at least three pKa’s (see Methods). Because we cannot reliably extract two distinct pKa’s from the data on the lower end of the acidic limb, the data were fit to an apparent acidic pKa,app for metal ion binding involving two ionizable groups [33]. Two additional pKa’s define the bell shape of the profile. This fit yields pKa’s of 6.1, 7.7 and 7.8. While the comparison involves measurements and/or calculations performed in the absence of DNA (see Discussion), it is worth noting that the lowest of these values correlates reasonably well with the pKa, app for Mg(II) binding by PvuII endonuclease (6.7) ([33] and above), and even better with the calculated pKa of Glu68 (6.3). Given the experimental uncertainty in the pKa calculations and in the kinetic measurements, if the differences between these values were smaller, it would not be more significant.

One of the higher, basically identical pKa’s correlates well with the water pKa calculated above for the nucleophilic water molecule and to that obtained in the pH dependence of EcoRV endonuclease cleavage rates and assigned to the same group [37]. The basic limb protonation most likely reflects the behavior of the second key water molecule in the active site, i.e., that assigned to leaving group protonation (see Fig. 1; [37]).

DISCUSSION

Correlating Experimental and Computational Data

pH dependence studies have long been useful in identifying active site groups which are involved in various aspects of enzyme function [46]. These correlative studies are most convincing when there is an obvious match between typical pKa’s and active site groups (e.g., neutral pKa and His). For many metallonucleases, assigning pKa,app values to specific functions is a particularly complex challenge. In addition to the metal ion dependence of cleavage, one must consider the pH dependence of metal ion and substrate binding, the latter of which is metal ion dependent in some systems [30, 47]. To further complicate matters, the active sites of many metallonucleases do not feature groups which typically ionize in the physiological range, but exhibit pH-dependent behavior with pKa,app values in this region. Metal ion binding in PvuII endonuclease [33] and DNA binding in MunI endonuclease [48] both have pKa, app values near neutrality. Since metallonucleases of this class have a number of conserved acidic groups in their active sites, it is reasonable to speculate that these groups ionize at unusually high pH [49] [[50].

The study most relevant to the data presented here are of EcoRV endonuclease. An examination of the pH dependence of kobs revealed a classical bell-shaped curve, each side of which exhibited a unity slope [37]. Two identical pKa’s of 8.5 were derived from these data and assigned to a general base (nucleophile activation via a Metal A-bound hydroxide) and a general acid (leaving group protonation via a Metal B-bound water). The general shape of the pH dependence of kobs for PvuII is remarkably similar to this. The distinguishing feature is the more complex behavior of the acidic limb, which in the log-log plot is clearly biphasic. Since the pH dependence of metal ion binding behavior by PvuII endonuclease is better characterized, this permits the application of a more complex model in which protonation of metal ion ligands, which inhibit metal binding and thus cleavage, can be included. Analysis of the data presented here yields three pKa,app values which can be assigned to metal binding (for simplification, two ionizations are represented with a macroscopic pKa,app of 6.1), a general base (7.7), and a general acid (7.8). Given that the metal ion binding work and pKa predictions were conducted in the absence of DNA, the correlations are surprisingly good: 6.1 is close to the calculated pKa,app for Glu68 (6.3), the critical bridging ligand. The general base value of 7.7 is comparable to the computed value for the nucleophilic water in PvuII structures in the conformation it adopts when bound to DNA (7.4). There are a few possible reasons for this. 1) The effect of the DNA is screened by counterions [51] such that the full effect is not experienced by active site groups. Even if the extent of this effect is not clear in the active sites of enzymes acting on nucleic acids, this is a general and well known phenomenon; 2) Nucleophile activation occurs before DNA binds (see below); and 3) Experimental error. pKa predictions have an uncertainty of one unit (see Methods). In a pH study of DNA binding by MunI endonuclease, data for unidentified ionizations were fit to a model in which the DNA elevated the pKa’s of these unidentified groups by about 1 unit [48]. Thus it is possible for DNA to exert an effect that might not be discernible within experimental error.

Theories of Nucleophile Activation

Authors who have published pH dependence studies offer support for the involvement of a metal hydroxide in protein [8, 37] and nucleic acid [9]. Of course what must always be reconciled is the fact that a Mg(II) ligated water has a very high pKa (11.4) for a reaction with a pH optimum that is typically below pH 8. This suggests that either a metal hydroxide is not the active species, or more interestingly, that there are other factor(s) which contribute to the stabilization of this nucleophile. Presented here is evidence that for the PD…(D/E)xK enzymes, nucleophile activation may indeed be a collaborative effort between a metal ion and a positively charged residue. Indeed, a role for the conserved Lys in EcoRV endonuclease in modulating the attacking nucleophile pKa has been proposed [52]. The fact that this conserved Lys influences the pKa of metal ligated waters in a number of PD…(D/E)xK metallonucleases lends strong support to this idea.

The fact that the effect of the Lys group on the nucleophilic water molecule is conserved in PvuII structures with one (1H56) and two (1F0O) active site metal ions (as well as in multiple other two-metal metallonuclease structures) indicates that the second metal ion does not play a role in this behavior. Nor should it: One, it is too far away to exert a Coulombic effect; two, no two-metal ion mechanism has been proposed or defended in which more than one metal ion interacted with the nucleophilic water.

A limitation of the proposal that Lys and metal ion work together to modulate the water pKa is that it clearly cannot apply to those metallonucleases which do not feature this group (i.e., outside of the PD…(D/E)xK subfamily). BamHI endonuclease is a notable exception among the restriction enzymes. This enzyme features a Glu residue in the position analogous to the conserved Lys in the aforementioned enzymes (Glu-113). Interestingly, when we apply the same UHBD algorithm to this enzyme, the pKa of the attacking water molecule is predicted to be 8.3. As expected, this value is lowered (to 7.2) when Glu-113 is neutralized, and raised to above 15 when the metal ion is removed. Fuxreiter and coworkers recently utilized protein dipoles/Langevin dipoles (PDLD/S) method, the EVB/FEP method, quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical calculations and molecular dynamics simulations of reaction energy barriers to support a mechanism that is termed “extrinsic” and refers to “the penetration of OH− from bulk solution”, with additional stabilization of the nucleophilic water via metal ion ligation [53, 54]. Using these approaches, pKa’s ranging from 5.3–6.2 were obtained for the nucleophilic water. While these values are lower than that obtained with UHBD, all of these pKa’s are substantially lower than that of a metal ion-ligated water in bulk solution and are consistent with an active site environment that stabilizes the nucleophile. The above mechanism proposed by these authors is similar to that proposed earlier for the exonuclease domain of Klenow fragment [55], another metallonuclease which does not feature an active site Lys residue.

These results suggest that either the metallonuclease mechanisms are not universal in every detail, or the proposal that Lys modulates the water pKa in PD…(D/E)xK enzymes lacks merit. Addressing the later, consider that without the positive charge on the Lys residue, the calculated water pKa’s in enzymes containing this residue are consistently elevated, and the electrostatic interaction potential between water and Lys is quite high. This indicates that the charge on this group indeed interacts with the water molecule and influences its ionization behavior. The fact that the PvuII variant K70A binds cognate DNA as well as WT but has very little cleavage activity is consistent with this explanation [3], and not with the possibility that the positively charged Lys functions to attract DNA to the active site. Moreover, mutations at this position in other PD…(D/E)xK enzymes are generally devastating to cleavage activity [5]. The bottom line is the PD…(D/E)xK enzymes have evolved to function with this Lys residue, even though it is clearly not required in metallonucleases with other motifs. Given the proximity of Lys to the water and the obvious influence on its pKa, the proposal that Lys contributes to the modulation of water pKa is quite reasonable. Other influences on the pKa of the water molecule, including the dielectric constant, ionic strength, etc., cannot and need not be ruled out.

Of course it also follows from the same electrostatic arguments that the presence of unneutralized polyanionic DNA would have the reverse effect of raising the pKa of the nucleophilic water. Modeling the nucleic acid using the more appropriate nonlinear form of the Poisson-Boltzmann equation [56, 57] is beyond the scope of this study. However, we have published kinetic evidence to support a mechanism in which the enzyme binds metal ion(s) before substrate [45]. In this scenario, the nucleophile can form in the absence of DNA. The subsequent introduction of substrate would lead to a competition between protonation of the nucleophile (precipitated by the introduction of negative charge, which raises the pKa) and nucleophilic attack. Secondly, there is substantial experimental evidence that significant neutralization is afforded by backbone interactions with bulk counterions [51]. And while it is reasonable to expect an impact from substrate binding on active site electrostatics, it is unlikely that the enzyme active site experiences the full effect of unmitigated negative charge from DNA. Regardless of which consideration is operative, clearly this is an area that merits further development. In the meantime, since the focus is on the influences of local groups on the water pKa, rather than the absolute value of the pKa itself, the trends documented in this work are clear.

Regarding the possibility of a universal metallonuclease mechanism, this seems quite unlikely. In the past several years, structural diversity in the active sites of metallonucleases has become increasingly obvious [34]. In addition to the occasional substitution of Lys for Glu, some metallonuclease active sites feature one metal ion, others two; some have one His residue, a common general base, while others have none or multiple His residues. It therefore follows that the means by which the mechanistic steps are achieved (i.e. what functional groups are involved) must vary. This does not discount the results or proposals presented here, nor are they in conflict with alternate proposals regarding other systems. Rather, the strategy applied here represents an opportunity for dissecting these details in systems of differing configurations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH GM67596. We are grateful to Julie King for initial work on this project and to Chung Wong for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- UHBD

University of Houston Brownian Dynamics

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- EDTA

ethylene diamine tetra acetate

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Derivation of equation 3.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mishra N. Nucleases-Molecular Biology and Applications. Wiley & Sons; Hoboken: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pingoud A, Fuxreiter M, Pingoud V, Wende W. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:685–707. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4513-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nastri HG, Evans PD, Walker IH, Riggs PD. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25761–25767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.José TJ, Conlan LH, Dupureur CM. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:814–823. doi: 10.1007/s007750050355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selent U, Ruter T, Kohler E, Liedtke M, Thielking V, Alves J, Oelgeschlager T, Wolfes H, Peters F, Pingoud A. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4808–4815. doi: 10.1021/bi00135a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupureur CM. Curr Chem Biol. 2008;2:159–173. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kragten J. Atlas of Metal-Ligand Equilibra in Aqueous Solution. Halsted Press; Chicester, England: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tock MR, Frary E, Sayers JR, Grasby JA. EMBO J. 2003;22:995–1004. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahm SC, Derrick WB, Uhlenbeck OC. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13040–13045. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Wang M, Zhang T, Sun H. Coord Chem Rev. 2004;248:147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton NC, Connolly BA, Perona JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3314–3324. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaller W, Robertson AD. Biochemistry. 1995;34:4714–23. doi: 10.1021/bi00014a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang AS, Gunner MR, Sampogna R, Sharp K, Honig B. Proteins. 1993;15:252–65. doi: 10.1002/prot.340150304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antosiewicz J, McCammon JA, Gilson MK. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:415–436. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehler EL, Guarnieri F. Biophys J. 1999;77:3–22. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76868-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antosiewicz J, McCammon JA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7819–7833. doi: 10.1021/bi9601565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen JE, McCammon JA. Protein Sci. 2003;12:313–26. doi: 10.1110/ps.0229903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble MA, Gul S, Verma CS, Brocklehurst K. Biochem J. 2000;351(Pt 3):723–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raquet X, Lounnas V, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Frere JM, Wade RC. Biophys J. 1997;73:2416–26. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jao SC, English Ospina SM, Berdis AJ, Starke DW, Post CB, Mieyal JJ. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4785–96. doi: 10.1021/bi0516327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quenneville J, Popovic DM, Stuchebrukhov AA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:1035–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riccardi D, Cui Q. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:5703–11. doi: 10.1021/jp070699w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varma S, Jakobsson E. Biophys J. 2004;86:690–704. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74148-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmquist B. Methods Enzymol. 1988;158:6–12. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)58042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupureur CM, Hallman LM. Eur J Biochem. 1999;261:261–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner FW. Methods Enzymol. 1988;158:21–32. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)58045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilson MK. Proteins. 1993;15:266–82. doi: 10.1002/prot.340150305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacKerell J, Bashford AD, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, III, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guex N, Peitsch MC. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2733. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conlan LH, Dupureur CM. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1335–1342. doi: 10.1021/bi015843x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis KJ, Morrison JF. Methods Enzymol. 1982;87:405–26. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie F, Qureshi S, Papadakos GA, Dupureur CM. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12540. doi: 10.1021/bi801027k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupureur CM, Conlan LH. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10921–10927. doi: 10.1021/bi000337d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupureur CM. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horton JR, Cheng X. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1049–1056. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spyridaki A, Matzen C, Lanio T, Jeltsch A, Simoncsits A, Athanasiadis A, Scheuring-Vanamee E, Kokkinidis M, Pingoud A. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:395–406. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00692-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sam MD, Perona JJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6576–6586. doi: 10.1021/bi9901580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spassov VZ, Luecke H, Gerwert K, Bashford D. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:203–19. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weast RC, editor. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. 64. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampogna RV, Honig B. Biophys J. 1994;66:1341–52. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80925-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pingoud A, Jeltsch A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3705–3727. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harding MM. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:401–11. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900019168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bastyns K, Froeyen M, Diaz JF, Volckaert G, Engelborghs Y. Proteins. 1996;24:370–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199603)24:3<370::AID-PROT10>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamotte-Brasseur J, Dubus A, Wade RC. Proteins. 2000;40:23–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(20000701)40:1<23::aid-prot40>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie F, Dupureur CM. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cleland WW. In: The Enzymes. Sigman D, Boyer P, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1990. pp. 99–158. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin AM, Horton NC, Lusetti S, Reich NO, Perona JJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8430–8439. doi: 10.1021/bi9905359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haq I, O’Brien R, Langunavicius A, Siksnys V, Ladbury JE. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14960–14967. doi: 10.1021/bi0113566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sasnauskas G, Jeltsch A, Pingoud A, Siksnys V. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4028–36. doi: 10.1021/bi982456n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen JE, Borchert TV, Vriend G. Protein Eng. 2001;14:505–12. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.7.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Record J, Lohman MTTM, de Haseth P. J Mol Biol. 1976;107:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(76)80023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horton NC, Newberry KJ, Perona JJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13489–13494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fuxreiter M, Osman R. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15017–23. doi: 10.1021/bi010987x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mones L, Kulhanek P, Florian J, Simon I, Fuxreiter M. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14514–23. doi: 10.1021/bi701630s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fothergill M, Goodman MF, Petruska J, Warshel A. J Amer Chem Soc. 1995;117:11619–11627. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Misra VK, Hecht JL, Yang AS, Honig B. Biophys J. 1998;75:2262–73. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77671-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Misra VK, Shiman R, Draper DE. Biopolymers. 2003;69:118–36. doi: 10.1002/bip.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horton NC, Perona JJ. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6841–6857. doi: 10.1021/bi0499056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hadden JM, Declais AC, Phillips SE, Lilley DM. Embo J. 2002;21:3505–15. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hickman AB, Li Y, Mathew SV, May EW, Craig NL, Dyda F. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deibert M, Grazulis S, Sasnauskas G, Siksnys V, Huber R. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:792–9. doi: 10.1038/79032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.