Abstract

Objective

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory condition associated with oxidative stress, but controversy persists regarding whether antioxidants such as vitamins C and E are preventative. To assess the role of combined deficiencies of vitamins C and E on the earliest stages of atherosclerosis, four combinations of vitamin supplementation (Low C/Low E, Low C/High E, High C/Low E, High C/High E) were studied in atherosclerosis-prone apolipoprotein E (apoE)-deficient mice also unable to synthesize their own vitamin C (gulo−/−). The effect of a more severe depletion of vitamin C alone was evaluated in a second experiment using gulo−/− mice carrying the hemizygous deletion of SVCT2, the vitamin C transporter.

Methods and Results

After 8 weeks on a high-fat diet (16% lard, 0.2% cholesterol), atherosclerosis developed in the aortic sinus areas of mice in all diet groups. Each vitamin-deficient diet significantly decreased liver and brain contents of the corresponding vitamin. Combined deficiency of both vitamins increased lipid peroxidation, doubled plaque size, and increased plaque macrophage content by 2-3-fold in males, although only plaque macrophage content was increased in females. A more severe deficiency of vitamin C in gulo−/− mice with defective cellular uptake of vitamin C increased both oxidative stress and atherosclerosis in apoE−/− mice compared to littermates on a diet replete in vitamin C, again most clearly in males.

Conclusion

Combined vitamin E and C deficiencies are required to worsen early atherosclerosis in an apoE-deficient mouse model. However, a more severe cellular deficiency of vitamin C alone promotes atherosclerosis when vitamin E is replete.

Keywords: Antioxidants, atherosclerosis, genetically altered mice, nutrition

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease that is initiated, at least in part, by the interaction of oxidized low density lipoprotein (oxLDL) with cells of the vascular wall 1. A potential role for oxidative stress in the disease has given rise to the notion that it might be prevented by antioxidant treatment, and especially by antioxidant vitamins such as ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and α-tocopherol (vitamin E). However, recent large clinical trials have generally not supported the notion that these antioxidant vitamins can slow the progression of established atherosclerosis 2–4. Whether antioxidant vitamins can prevent or slow early atherosclerosis may be a more relevant question that is not readily tested in humans, given the prolonged asymptomatic period of the disease. Studies in animal models of atherosclerosis might provide support for such clinical trials, but these are also hampered by the fact that most mammals can synthesize vitamin C, making it difficult to deplete the vitamin. One exception is the guinea pig, which, like humans, lacks the enzyme gulonolactone oxidase (gulo), and thus the ability to synthesize vitamin C. Indeed, guinea pigs with early scurvy were shown over 5 decades ago to develop lesions that on histology were indistinguishable from atherosclerosis in regions of large arteries exposed to hemodynamic stress 5. These lesions were reversed by provision of ascorbate in the diet 6. These findings were extended by Maeda, et al. 7 using a mouse model in which gulo was deleted by targeted gene disruption. When placed on a diet deficient in vitamin C the gulo−/− mice developed early scurvy after 4–5 weeks, and aortas showed disruption of the elastic lamina. However, no intimal lesions characteristic of atherosclerosis were observed. To investigate this issue in more detail, Maeda and colleagues crossed the gulo−/− mice with mice deficient in apolipoprotein E (apoE) 8. The mice were fed normal chow diets (practically ascorbate-free) and were supplemented with ascorbate in their drinking water with two levels of the vitamin: one that produces supra-normal plasma and liver ascorbate concentrations, and the other that results in levels 25–30% of normal (still adequate to sustain normal weight gain and prevent scurvy). After 4 months on these vitamin C intakes, the mice had developed lipid-laden atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic sinus that increased in size after 9 months of continued supplementation. However, ascorbate intake did not affect lesion size at either time in either gender. Feeding a high fat diet for 4 months increased plaque size, but there was still no difference in lesion size between the two ascorbate diets. On the other hand, compared to mice on the high ascorbate supplements, mice on the low ascorbate supplements showed plaques with 30–50% decreases in collagen content, larger necrotic cores, and decreased fibrosis. Although these results suggest a role for ascorbate in plaque morphology and possibly plaque stability, they fail to support the notion that marginal ascorbate deficiency affects atherosclerotic plaque development, size, or progression.

Despite the negative results with moderate vitamin C deficiency alone, several caveats are worth considering. First, there may be different effects of vitamin C deficiency at earlier time points than 4 months, since vitamin C is best known to affect early changes in atherosclerosis, such as endothelial dysfunction 9 and since irreversible changes may not have occurred at this early time point. Second, there may be a cooperative effect of vitamin C and vitamin E in protecting arterial wall integrity, and a more severe deficiency of vitamin C may be required in the mouse model. Indeed, since lipid hydroperoxides in oxLDL appear to be required for lesion formation, 10 the lipid-soluble vitamin E (α-tocopherol) might be better at quenching lipid hydroperoxide propagation compared to the water-soluble ascorbate. Moreover, ascorbate is capable of recycling α-tocopherol in lipid micelles 11 and of sparing α-tocopherol in intact cells (reviewed in 9). Further, two studies have shown that a severe deficiency of vitamin E due to lack of the α-tocopherol transfer protein increased atherosclerosis in apoE−/− mice 12, 13. Third, a more significant depletion of vitamin C may be required to provide proof-of-principle evidence that supplementation has therapeutic effects on early atherosclerosis. To test these possibilities, we carried out two experiments. In the first, we tested whether combined ascorbate and α-tocopherol deficiency hastens early plaque development and progression in gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice fed a high-fat diet supplemented with low or high levels of vitamin C or vitamin E. In the second experiment, we tested the impact of high and low levels of vitamin C intake on early atherosclerosis in gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice also deficient in one allele of the transporter that brings vitamin C into most vascular cells, the SVCT2. Our results show that low levels of both vitamins C and E increase early lesion size and plaque macrophage content and that a severe deficiency of vitamin C is required to increase plaque size when vitamin E is replete, with differences more pronounced in males.

Methods and Materials

Atherosclerosis Models

Double knockout gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice that had been backcrossed at least 8 generations onto the C57BL/6 background were obtained from MMRRC (http://www.mmrrc.org). These mice were used in Experiment #1 in which vitamins C and E were both modified. In Experiment #2, gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice were crossed with SVCT2+/− mice, which had also been separately placed on the C57BL/6 background by 9 backcrosses. Gulo−/−/apoE−/−/ SVCT2+/− mice were obtained after backcrossing the resulting SVCT2+/− progeny to gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice. The genotype of each pup was determined for by PCR as described previously 7, 14 with minor modifications using the following primers: apoE (TGTGACTTGGGAGCTCTGCAGC, GCCGCCCCGACTGCATCT, CATCTGTGCGTGCATAGTAGC); gulo (CGCGCCTTAATTAAGGATCC, GTCGTGACAGAATGTCTTGC, GCATCCCAGTGACTAAGGAT), and SVCT2 (CATCTGTGCGTGCATAGTAGC, CACCGTGGCCCTCATTG, TCTGAGCCCAGAAAGCGAAG, GATGGACGGCATACAAGTTC).

All mice were maintained during breeding and pregnancy on normal rodent chow (Purina Lab Diet #5001) that contained about 45 International units (IU)/kg vitamin E and negligible amounts of vitamin C. Drinking water for the pregnant dams was changed twice weekly and prepared from deionized water and contained 0.33 g/l ascorbate and 0.01 mM EDTA. Deionized water was used to prepare the ascorbate-containing drinking water, since it was found that almost all ascorbate was lost after 48 h when tap water was used, whereas only about 10% was lost when deionized water was used (results not shown). This level of ascorbate supplementation has been shown to result in normal plasma and liver levels of vitamin C 8. All protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Vanderbilt University.

Diet and supplements of vitamins C and E

After weaning, male and female pups were maintained on normal chow and drinking water that contained 0.33 g/l ascorbate and 0.01 mM EDTA until 5 weeks of age. All mice were then placed on high fat diets from Harlan-Teklad (Madison, WI). For Experiment #1, the diets lacked vitamin C and either contained vitamin E (TD.07311, 135 International units(IU)/kg of vitamin E as DL-α-tocopheryl acetate, 16% vitamin E-stripped lard, 0.2% cholesterol), or lacked vitamin E (TD.07310, ~5 International units/kg of vitamin E, 16% vitamin E-stripped lard, 0.2% cholesterol). For Experiment #2, gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice were placed on the high fat diet with vitamin E supplements as noted for Experiment #1.

For Experiment #1, mice were randomly assigned to one of 4 groups with different levels of vitamin C and E supplementation. The groups were as follows (based on average individual consumption of 4 g of feed and 5 ml of water per day) 15: HighE/HighC, 0.27 mg (0.6 IU) vitamin E daily plus 1.7 mg vitamin C daily; HighE/LowC, 0.27 mg vitamin E daily plus 0.17 mg vitamin C daily; LowE/HighC, ~0.01 mg vitamin E daily plus 1.7 mg vitamin C daily; and LowE/LowC, ~0.01 mg vitamin E daily plus 0.17 mg vitamin C daily. Vitamin E was supplemented by the supplier in the diet, whereas vitamin C was supplemented in the drinking water that also contained 0.01 mM EDTA. The concentrations of vitamin C in the drinking water were HighC = 0.33 g/l and LowC = 0.033 g/l water.

For experiment #2, gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice were randomly assigned to the same high or low contents of vitamin C in the drinking water as noted for Experiment #1: HighC = 0.33 g/l and LowC = 0.033 g/l water.

Plasma lipid analyses

Plasma cholesterol and triglycerides were determined in 4-hour-fasted mice as previously described 16

Assays of ascorbate, α-tocopherol and lipid peroxidation products

For assay of ascorbate, weighed tissues (50–100 µg wet weight) were homogenized in microfuge tubes using a plastic pestle in 0.1 ml of 25% metaphosphoric acid (w/v), followed by further homogenization in 0.35 ml of a buffer containing 0.1 M Na2HPO4 and 0.05 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. For assay of ascorbate in serum, 0.1 ml of serum was treated with 400 mM sodium perchlorate and mixed. The treated serum or tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 3 °C for 1 min at 13,000 × g. Duplicate aliquots of supernatant were taken for assay of ascorbate 17. Vitamin E in tissues and plasma was assayed as α-tocopherol by HPLC with electrochemical detection by the method of Lang, et al. 18. Malondialdehyde was measured in heart using the HPLC method of Tebbe, et al. 19, as previously modified 20. F2-isoprostanes were analyzed after Folch extraction, base hydrolysis, and derivatization as previously described 21 in the Eicosanoid Core Laboratory at Vanderbilt University. In both assays butylated hydroxytoluene was added during extraction and sample preparation to prevent further oxidative modification of unsaturated fatty acids.

Quantification of Arterial Lesions

Mice were killed under general anesthesia and 30 ml of saline was flushed through the left ventricle. The heart with proximal aorta intact was removed and embedded in Tissue Tek OCT solution (100498-158, VWR Scientific, Suwanee, GA), and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections of the proximal aorta of 10 µm thickness were prepared as described 22, starting at the aortic sinus and continuing distally according to the method of Paigen, et al. 23, adapted for computer analysis 16. Aortic sections were stained with oil red O and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images of 4 sections of each aorta were captured and analyzed with an imaging system (KS 300, release 2.0, Kontron Electronik GmbH).

Immunocytochemistry

To detect macrophages, 5 µm serial cryosections of the proximal aorta were fixed in cold acetone and incubated overnight at 4 °C in 5 mM phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) with a rat antibody to mouse macrophage-derived foam cells, MOMA-2 (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corp.)24. The sections were treated with biotinylated goat antibodies to rat IgG (PharMingen) and incubated with avidin-biotin complex labeled with alkaline phosphatase (Vector Laboratory). Fast Red TR/Napthol AS-NX substrate (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was used to visualize enzyme activity. Photomicroscopy was carried out with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope with Plan-FLUAR objectives. The area of macrophage immunostaining in the atherosclerotic lesions was quantified as described for oil red O, above.

Statistical Analyses

The results were calculated as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance with post-hoc testing (Experiment #1) or by non-paired t-testing (Experiment #2) using the software program Sigma Stat 2.0 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Significance was based on a p value of < 0.05.

Results

Experiment #1

At the completion of the 8 week experiment, none of the mice showed signs of vitamin E deficiency (ataxia, gait difficulties) or of scurvy (lassitude, changes in fur or grooming, weight loss). Mouse weights (Table 1) at the end of the diet period were higher in males than females (p = 0.002) and higher in females fed high levels of both vitamins. All of the mice had markedly elevated plasma cholesterol values after 8 weeks of a diet increased in fat and cholesterol (Table 1). Despite the fact that the diets all had the same amount of cholesterol and fat, there were differences amongst the diets with varying vitamin contents in both cholesterol and triglycerides. Cholesterol levels in both genders tended to be higher in mice on the vitamin E-deficient diets than in mice on vitamin E-replete diets (Table 1). In contrast, vitamin E-deficient mice of both genders had significantly lower triglyceride levels than mice on the high supplements of vitamin E. The presence or absence of vitamin C had no effect on lipid levels, and gender did not have consistent effects across the different treatments.

Table 1.

Body weight and biochemical data at the end of the diet study*

| HighE/HighC | HighE/LowC | LowE/HighC | LowE/LowC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight: | males | 23 ± 2a | 19 ± 8a | 22 ± 3a | 21 ± 5a |

| (grams) | females | 22 ± 1a | 18 ± 3b | 19 ± 2b | 19 ± 3b |

| Cholesterol: | males | 630 ± 76a,b | 525 ± 239a | 872 ± 256b | 860 ± 252b |

| (mg/dl) | females | 365 ± 85a | 569 ± 77a,b | 697 ± 80b | 578 ± 184b |

| Triglycerides: | males | 546 ± 297a | 254 ± 151a | 91 ± 11b | 86 ± 16b |

| (mg/dl) | females | 354 ± 130a | 342 ± 70a | 134 ± 17b | 115 ± 52b |

| Liver ascorbate: | males | 1.6 ± 0.6a | 0.6 ± 0.5b | 1.7 ± 0.5a | 0.5 ± 0.6b |

| (µmol/g wet wt) | females | 1.7 ± 0.4a | 1.1 ± 0.9a,b | 1.5 ± 0.4a | 0.4 ± 0.5b |

| Brain ascorbate | males | 7.3 ± 4.9a | 2.2 ± 2.2b | 3.1 ± 0.8a,b | 1.2 ± 1.3b |

| (µmol/g wet wt) | females | 5.6 ± 2.2a | 2.5 ± 2.0a,b | 3.1 ± 1.5a | 1.1 ± 1.1b |

| Liver α-tocopherol: | males | 60 ± 50a,b | 98 ± 93a | 13 ± 17b,c | 6.5 ± 11c |

| (nmol/g wet wt) | females | 73 ± 30a | 71 ± 48a | 17 ± 13b | 12 ± 20b |

| Brain α-tocopherol | males | 32 ± 15a | 31 ± 18a | 3.0 ± 3.9b | 6.1 ± 9.2b |

| (nmol/g wet wt) | females | 32 ± 13a | 42 ± 13a | 2.9 ± 2.3b | 3.7 ± 7.2b |

Results shown as mean ± standard deviation are from at least 8 values for each gender and treatment group.

Values in the same row that do not share superscripts are significantly different (p<0.05).

Ascorbate and α-tocopherol levels in liver and brain cortex were modified as expected, based on the different diets (Table 1). Liver and brain ascorbate levels were decreased 40–75% in mice fed low amounts of the vitamin in their drinking water compared to mice on high vitamin C intakes. It should be noted that the high level of vitamin C intake supplements mice only to approximately normal plasma and tissue levels of the vitamin 8, not to supra-normal levels. In gulo−/− mice on the low vitamin C intake for 4 weeks, serum ascorbate levels were 15 ± 4 µM compared to 54 ± 4 µM in littermates fed the high level of vitamin C. This 72% decrease is in line with that seen in liver. Levels of α-tocopherol in mice on the low vitamin E diets were decreased by 75–90% of the levels in both liver and brain compared to mice on the high vitamin E diets. In gulo−/− mice on the low vitamin E intake for 16 weeks, serum α-tocopherol levels were 3.8 ± 1.4 µM compared to 25 ± 4 µM in littermates fed the high level of vitamin E. This 85% decrease is in line with that seen in liver. The vitamin E supplement level of 135 IU/kg was somewhat higher than typically supplemented in normal rodent chow (45–90 IU/kg). There were no consistent effects of gender or of either vitamin E or vitamin C to modify levels of the other vitamin.

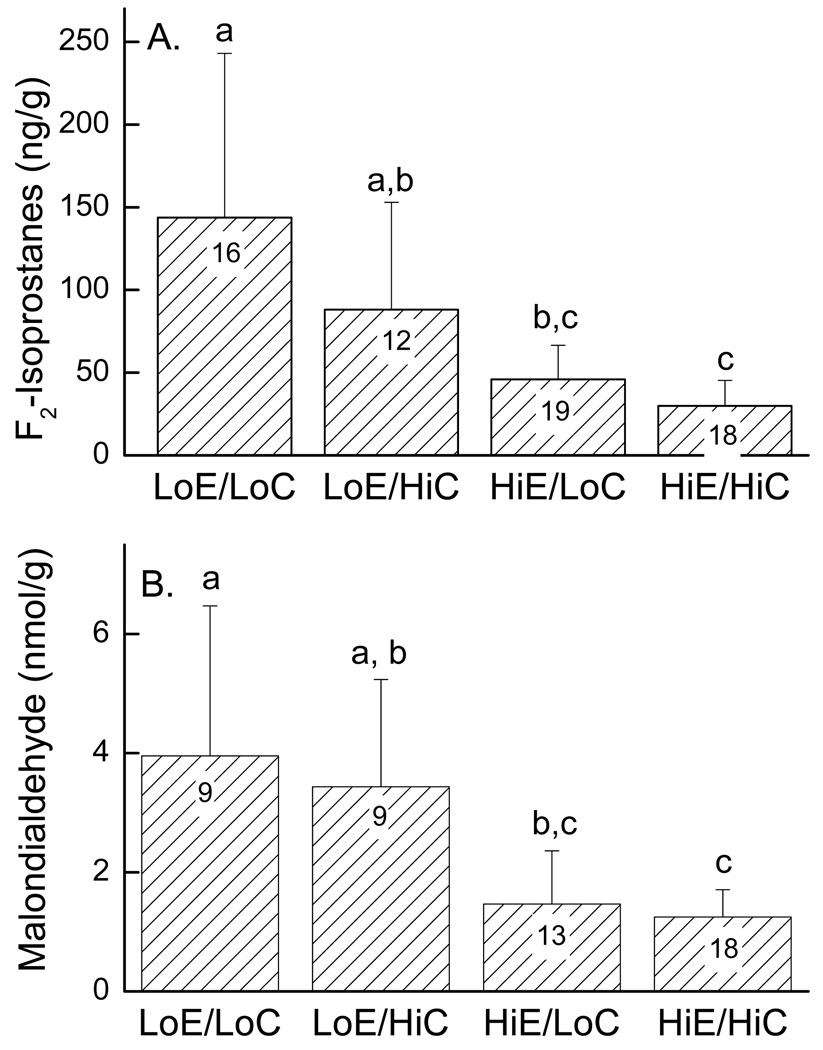

To assess oxidative stress in response to vitamin deficiency, F2-isoprostane levels were determined in liver (Fig. 1A) and malondialdehyde concentrations were measured in heart (Fig. 1B). There were no gender differences for either measurement, so data from males and females was combined. For both measurements, mice with low intakes of both vitamins (LowE/LowC) had greater than 50% increases in the levels of both lipid peroxidation products compared to the respective tissues from mice on diets supplemented with vitamin E (HighE/LowC, HighE/HighC). Even when vitamin C was supplemented to approximately normal levels, a diet low in vitamin E increased both liver F2-isoprostanes and heart malondialdehyde (Fig. 1, LoE/HiC vs. HiE/HiC).

Figure 1.

Liver F2-isoprostanes (Panel A) and heart malondialdehyde (Panel B) contents of hearts of mice on the various diets. The bar plot shows mean + standard deviation, with the number of mice noted in the bars. Statistical differences are indicated by the small letters above the data, such that treatments with no letters in common were different.

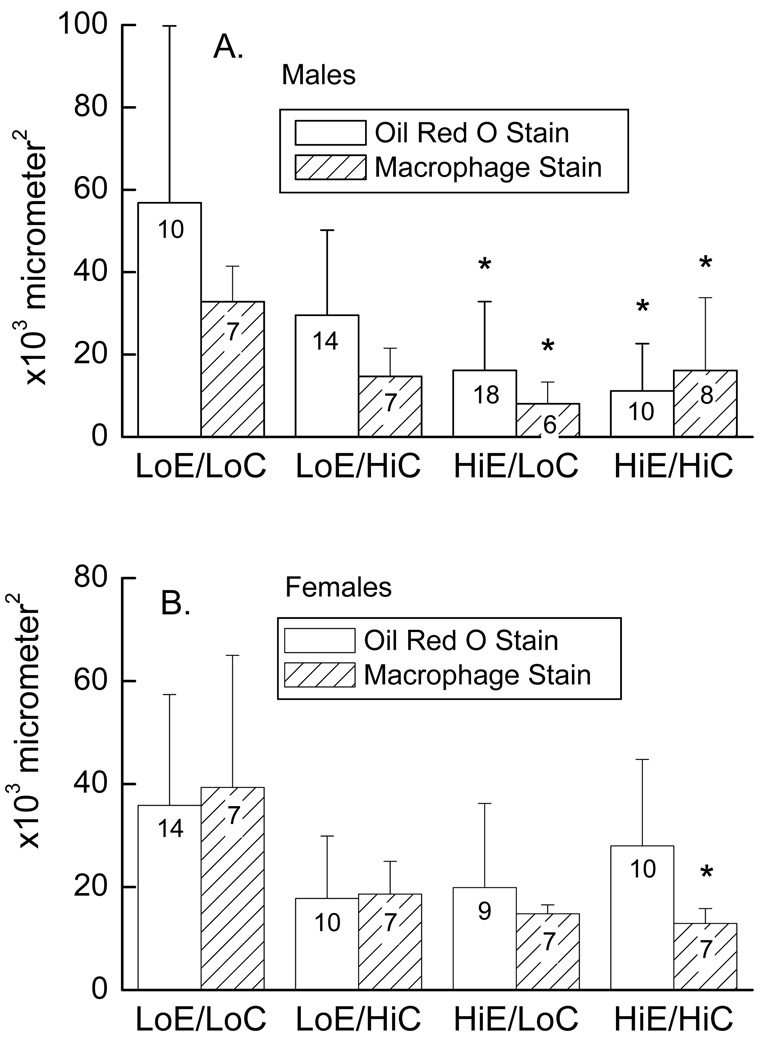

The extent of atherosclerosis in the aortic sinus area was determined by measuring the lesion area using oil red O staining for lipids and MOMA immunostaining for macrophages. Lesion size and macrophage content correlated well across the different diets in the individual mice of both genders (R = 0.55, p < 0.001), supporting the notion that both assays measured the extent of early atherosclerosis, when most of the lesion is composed of viable macrophages 25. In the male mice, lesion area and macrophage staining were significantly increased when mice were on diets low in both vitamins (Fig. 2A, LowE/LowC) compared to the diets in which vitamin E was supplemented (HighE/LowC, HighE/HighC). In the females, mice fed the diet low in both vitamins (LowE/LowC) showed a significantly increased area of macrophage staining with MOMA-2 in the atherosclerotic lesions compared to mice fed the diet high in both vitamins (HighE/HighC, Fig. 2B), although the lesion sizes were not significantly different due to variability in the HighE/HighC group. The previously noted tendency for mice with vitamin E deficiency to have higher cholesterols did not appear to be the mechanism of the observed effect, since lesion area did not show a significant correlation with cholesterol levels in either gender or in the combined genders (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Atherosclerosis in the aortic sinus area of mice on different diet treatments. Panel A shows results in males and Panel B in females. Bar plots show mean + standard deviation, with the number of mice noted in the bars. An asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05 compared to the LowE/LowC diet.

Experiment 2

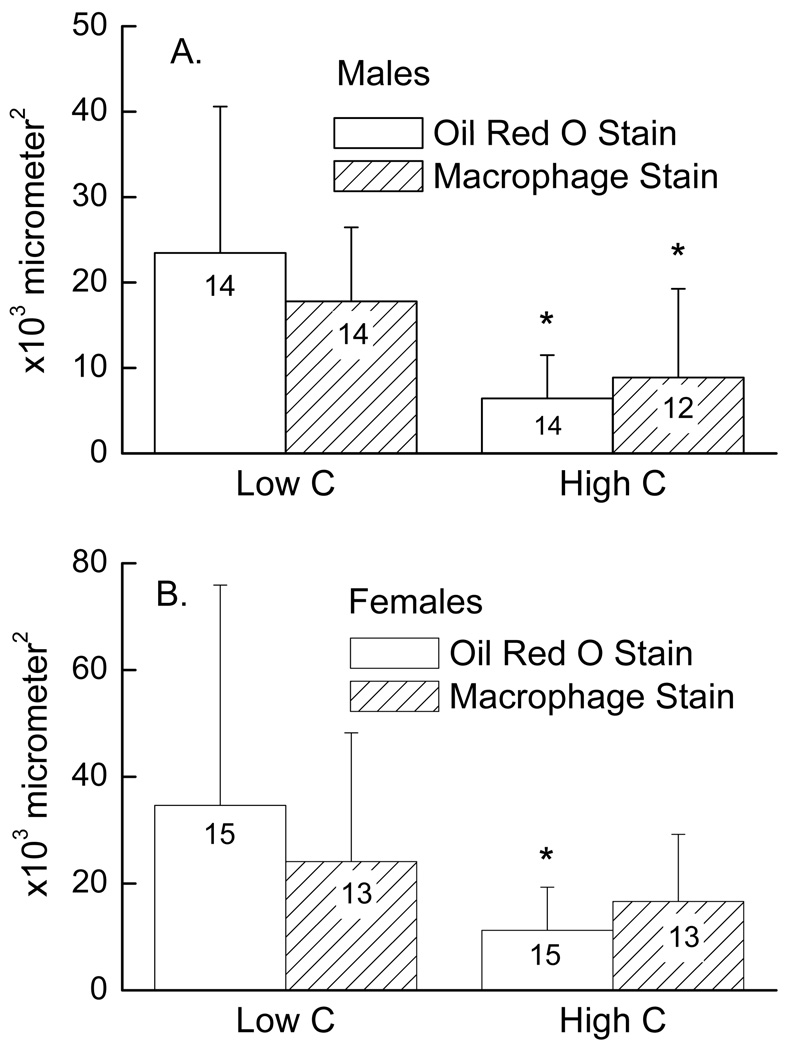

The failure of vitamin C deficiency to affect atherosclerosis in mice not deficient in vitamin E in this and the previous study by Maeda, et al. 7 brings up the question of whether a more severe cellular deficiency of vitamin C might have an effect in mice on an adequate intake of vitamin E. To further decrease cellular vitamin C by a non-dietary approach, we crossed gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice with mice hemizygous for deficiency of the ascorbate transporter, SVCT2 (SVCT2+/−). These mice were fertile and grew normally on normal rodent chow and drinking water containing the standard vitamin C supplement of 0.33 g/l. When placed for 8 weeks on drinking water containing the low amount of vitamin C used in Experiment 1 (0.033 g/l), the mice continued to do well and showed no physical signs of scurvy. As shown in Table 2, decreasing the vitamin C intake did not significantly affect weights of the gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice. Gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice on the same vitamin C and E intake as the gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice shown in Table 1 (HighE/HighC and HighE/LowC) had decreased vitamin C levels in brain (p < 0.001) and liver (p < 0.01), irrespective of vitamin C intake. This confirms that deleting one allele of the SVCT2 lowers tissue vitamin C levels. As expected, feeding the mice water with a low vitamin C content further decreased vitamin C levels in liver, brain and heart compared to gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice on the high level of vitamin C intake (Table 2). Quantification of lesion size showed that the male mice on the low vitamin C intake had increases in both lesion size (3.6-fold increase, p = 0.003) and macrophage content (2-fold increase, p = 0.03) compared to littermates on high vitamin C intake (Fig. 3A). For the females, these increases were 3.1-fold in lesion size (p = 0.03) and 1.4-fold in macrophage content (p = 0.33) (Fig. 3B). These results show that a more severe lowering the tissue content of vitamin C due to a partial deficiency of the SVCT2 plus a low vitamin C intake significantly increased both lesion size and lesion macrophage content in male mice and increased lesion size in female mice.

Table 2.

Body weight and biochemical data for apoE−/−/gulo−/−/SVCT2+/− mice*

| High C | Low C | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight: | males | 25 ± 2a | 18 ± 4a |

| (grams) | females | 21 ± 2a | 21 ± 3a |

| Cholesterol: | males | 608 ± 160a | 521 ± 136a |

| (mg/dl) | females | 533 ± 147a | 504 ± 126a |

| Triglycerides: | males | 334 ± 111a | 220 ± 54a |

| (mg/dl) | females | 265 ± 59a | 264 ± 75a |

| Liver ascorbate: | males | 0.5 ± 0.2a | 0.3 ± 0.2b |

| (µmol/g wet wt) | females | 0.7 ± 0.1a | 0.2 ± 0.2b |

| Brain ascorbate | males | 1.2 ± 0.3a | 0.4 ± 0.2b |

| (µmol/g wet wt) | females | 1.5 ± 0.6a | 0.4 ± 0.2b |

| Heart ascorbate | males | 0.4 ± 0.2a | 0.1 ± 0.1b |

| (µmol/g wet wt) | females | 0.6 ± 0.5a | 0.1 ± 0.1b |

Results shown as mean ± standard deviation are from at least 14 values for each gender and treatment group.

Values in the same row that do not share superscripts are significantly different (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Aortic sinus atherosclerosis in mice on different intakes of vitamin C. Panel A shows results in males and Panel B in females as mean + standard deviation, with the number of mice noted in the bars. An asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05 compared to the group with a low vitamin C intake.

Discussion

We assessed the impact of combined deficiencies of vitamins C and E on early atherogenesis in apoE deficient mice unable to synthesize their own vitamin C. Atherosclerosis-prone gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice showed increased lesion size and macrophage immunostaining in the aortic sinus area after only eight weeks on a high fat diet. This regimen resulted in less atherosclerosis (< 25 × 103 µm2) than that seen by Nakata, et al. 8 in gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice on normal rodent chow (31–35 × 103 µm2) for a total of 16 weeks. In male gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice fed the diet low in vitamin C and E, both the extent of atherosclerosis and the area staining for macrophages within the lesions were increased compared to mice with high level supplementation of vitamin E. In female gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice fed the diet low in vitamin C and E the area staining for macrophages in the atherosclerotic lesions was significantly increased compared to those fed the diet high in both vitamins, but the trend for an increase in atherosclerosis was not significant. In agreement with Nakata, et al. 8, there was no effect of moderate vitamin C deficiency in serum and tissues on lesion size when vitamin E levels were not depressed. On the other hand, when a more severe cellular vitamin C deficiency was induced by using gulo−/−/apoE−/− mice having only half the number of vitamin C transporters (gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/−), the extent of atherosclerosis was increased despite the same relatively high level of vitamin E supplementation as in the first experiment. Intracellular ascorbate was decreased by halving the number of ascorbate transporters in liver and brain, and was further decreased when the dietary intake of vitamin C was lowered. The latter was especially evident in heart, although vitamin C still remained detectible in all three tissues. Since these mice did not have signs of scurvy, the results suggest that the atherosclerotic process is differentially sensitive to severe cellular ascorbate depletion. A similar effect of what was likely severe ascorbate deficiency alone was found some years ago in guinea pigs 6, although vitamin C levels were not measured. The finding that macrophage area was increased in the male gulo−/−/apoE−/−/SVCT2+/− mice on low ascorbate intakes suggests that this cell type may play a critical role in the increased susceptibility to atherogenesis with severe deficiency of vitamin C, although further studies at the cellular level are needed to define the mechanism.

In our current studies, combined deficiencies of vitamins C and E were required to increase both atherosclerotic lesion size and the macrophage content of the lesions. These results suggest that an adequate intake of vitamin E is more important than that of vitamin C in protecting against atherosclerosis in apoE−/−/gulo−/− mice. As to the mechanism of this difference, increased oxidative stress was likely a major contributing factor, since lipid peroxidation products were increased in both heart and liver of the mice on vitamin E-deficient diets. Although cholesterol levels also tended to be higher in vitamin E-deficient mice in this study, lesion size did not correlate with cholesterol in either gender, so it seems unlikely that different cholesterol levels contributed to the differences observed.

The role of severe vitamin E deficiency alone was previously evaluated by two groups using apoE−/− mice unable to assimilate α-tocopherol due to lack of the α-tocopherol transfer protein. After 6–7 months of diet treatments, vitamin E deficiency caused a significant 20–30% increase in aortic atherosclerosis 12, 13. In those studies, the extent of vitamin E deficiency (80–90%) was similar to that induced by diet in both serum and tissues in the present study, and serum and tissue vitamin E levels in the supplemented groups were also comparable. The earlier studies were of longer duration (6–7 months vs. 2 months), so that the lesions were many-fold larger and more advanced, extending to the abdominal aorta in the study by Suarna, et al. 13 Our results show that in earlier lesions the deleterious effect of vitamin E deficiency requires concomitant deficiency of vitamin C.

Although this study shows a significant effect of combined deficiencies of vitamins C and E on mouse atherosclerosis, it does not address the issue of whether vitamin supplements above normal intakes will have a favorable impact on atherosclerosis. Initial studies in either apoE-deficient mice 26 or in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice 27 showed that very high vitamin E supplements in these mice (2000 IU/kg diet versus 175 IU/kg diet in the present study) markedly suppressed both urinary F2-isoprostanes and the extent of aortic atherosclerosis over 12–14 weeks 26, 27. On the other hand, in a more recent study Suarna, et al. 13 failed to see an effect on atherosclerosis of the same high level of vitamin E supplements used in the two earlier studies. A more potent vitamin E analog did improve atherosclerosis in apoE−/− mice not deficient in α-tocopherol in the Suarna study, however 13. In addition to decreasing oxidative stress, vitamin E supplements might affect the progression of atherosclerosis by modifying lipid levels. Although vitamin E supplements several times those in normal rodent chow increased triglycerides in apoE−/− mice in this study, this has not been a consistent response in either apoE−/− mice 26, 27 or in humans 28.

In conclusion, the present results show that both moderate combined vitamin C and E deficiencies and a severe cellular deficiency of vitamin C alone accelerate early atherosclerosis in male apoE−/− mice. They support the notion that oxidative stress accelerates atherosclerosis as well as define the extent to which such vitamins must be depleted to observe an effect on atherosclerosis. It can be argued that deficiencies to the extent induced in these studies (15–28% of normal) are uncommon in humans. On the other hand, it is plausible that longer term but less severe depletion could have similar effects on human atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH grant DK050435 to JMM, HL065709 and HL057986 to SF, 18 HL065405 and HL086988 to MFL, and by center/core grants DK59637, GM15431, and DK020593.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, Buring JE, Manson JE. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:1610–1618. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, Bubes V, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, Gaziano JM. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2123–2133. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willis GC. An experimental study of the intimal ground substance in atherosclerosis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1953;69:17–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis GC. The reversibility of atherosclerosis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1957;77:106–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda N, Hagihara H, Nakata Y, Hiller S, Wilder J, Reddick R. Aortic wall damage in mice unable to synthesize ascorbic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:841–846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakata Y, Maeda N. Vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque morphology in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice unable to make ascorbic acid. Circulation. 2002;105:1485–1490. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012142.69612.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguirre R, May JM. Inflammation in the vascular bed: Importance of vitamin C. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;119:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stocker R, Keaney JF., Jr New insights on oxidative stress in the artery wall. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;3:1825–1834. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niki E, Noguchi N, Tsuchihashi H, Gotoh N. Interaction among vitamin C, vitamin E, and β-carotene. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995;62 Suppl.:1322S–1326S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1322S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Terasawa Y, Ladha Z, Leonard SW, Morrow JD, Newland D, Sanan D, Packer L, Traber MG, Farese RV., Jr Increased atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice deficient in α–tocopherol transfer protein and vitamin E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:13830–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240462697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suarna C, Wu BJ, Choy K, Mori T, Croft K, Cynshi O, Stocker R. Protective effect of vitamin E supplements on experimental atherosclerosis is modest and depends on preexisting vitamin E deficiency. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:722–730. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sotiriou S, Gispert S, Cheng J, Wang YH, Chen A, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Miller GF, Kwon O, Levine M, Guttentag SH, Nussbaum RL. Ascorbic-acid transporter Slc23a1 is essential for vitamin C transport into the brain and for perinatal survival. Nature Med. 2002;8:514–517. doi: 10.1038/0502-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies I, Goddard C, Fotheringham AP, Moser B, Faragher EB. The effect of age on the control of water conservation in the laboratory mouse--metabolic studies. Exp. Gerontol. 1985;20:53–66. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(85)90009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazio S, Babaev VR, Murray AB, Hasty AH, Carter KJ, Gleaves LA, Atkinson JB, Linton MF. Increased atherosclerosis in mice reconstituted with apolipoprotein E null macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:4647–4652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendiratta S, Qu Z-C, May JM. Erythrocyte ascorbate recycling: Antioxidant effects in blood. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998;24:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang JK, Gohil K, Packer L. Simultaneous determination of tocopherols, ubiquinols, and ubiquinones in blood, plasma, tissue homogenates, and subcellular fractions. Anal. Biochem. 1986;157:106–116. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tebbe B, Wu SL, Geilen CC, Eberle J, Kodelja V, Orfanos CE. L-ascorbic acid inhibits UVA-induced lipid peroxidation and secretion of IL-1α and IL-6 in cultured human keratinocytes in vitro. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;108:302–306. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12286468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabharwal AK, May JM. alpha-Lipoic acid and ascorbate prevent LDL oxidation and oxidant stress in endothelial cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2008;309:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9650-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milne GL, Yin H, Brooks JD, Sanchez S, Jackson RL, Morrow JD. Quantification of f2-isoprostanes in biological fluids and tissues as a measure of oxidant stress. Methods Enzymol. 2007;433:113–126. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)33006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Babaev VR, Patel MB, Semenkovich CF, Fazio S, Linton MF. Macrophage lipoprotein lipase promotes foam cell formation and atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26293–26299. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paigen B, Morrow A, Holmes PA, Mitchell D, Williams RA. Quantitative assessment of atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Atherosclerosis. 1987;68:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraal G, Rep M, Janse M. Macrophages in T and B cell compartments and other tissue macrophages recognized by monoclonal antibody MOMA-2. An immunohistochemical study. Scand. J. Immunol. 1987;26:653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1987.tb02301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babaev VR, Chew JD, Ding L, Davis S, Breyer MD, Breyer RM, Oates JA, Fazio S, Linton MF. Macrophage EP4 deficiency increases apoptosis and suppresses early atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;8:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pratico D, Tangirala RK, Rader DJ, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. Vitamin E suppresses isoprostane generation in vivo and reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1038/2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cyrus T, Yao Y, Rokach J, Tang LX, Pratico D. Vitamin E reduces progression of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice with established vascular lesions. Circulation. 2003;107:521–523. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055186.40785.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts LJ, Oates JA, Linton MF, Fazio S, Meador BP, Gross MD, Shyr Y, Morrow JD. The relationship between dose of vitamin E and suppression of oxidative stress in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:1388–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]