Abstract

We study a general class of partially linear transformation models, which extend linear transformation models by incorporating nonlinear covariate effects in survival data analysis. A new martingale-based estimating equation approach, consisting of both global and kernel-weighted local estimation equations, is developed for estimating the parametric and nonparametric covariate effects in a unified manner. We show that with a proper choice of the kernel bandwidth parameter, one can obtain the consistent and asymptotically normal parameter estimates for the linear effects. Asymptotic properties of the estimated nonlinear effects are established as well. We further suggest a simple resampling method to estimate the asymptotic variance of the linear estimates and show its effectiveness. To facilitate the implementation of the new procedure, an iterative algorithm is developed. Numerical examples are given to illustrate the finite-sample performance of the procedure.

Keywords: Estimating equations, Local polynomials, Martingale, Partially linear transformation models, Resampling

1. INTRODUCTION

Linear transformation models provide a general framework for model estimation and inferences in censored survival data analysis, and they have recently attracted considerable attention due to their high flexibility (Clayton and Cuzick, 1985; Bickel et al., 1993; Cheng et al., 1995, 1997; Fine et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2002; Zeng and Lin, 2006; among others). Let T be the survival time and Z be the p-dimensional covariate vector. To the model effects of Z on the response T, the linear transformation models assume that

| (1) |

where H is a completely unspecified strictly increasing function, β is a p × 1 vector of unknown regression coefficients, and the error term ∊ has a known continuous distribution that is independent of Z. In the presence of censoring, we observe the event time and the censoring indicator δ = I(T ≤ C), where C is the censoring time and I(·) is the indicator function. It is usually assumed that the censoring variable C is independent of T given Z.

Linear transformation models include many useful models as special cases. For example, if ∊ follows the extreme value distribution, then the model (1) becomes the Cox’s proportional hazards model (Cox, 1972); if ∊ follows the standard logistic distribution, then (1) reduces to the proportional odds model (Pettitt, 1982, 1984; Bennett, 1983); if there is no censoring and ∊ follows the standard normal distribution, (1) generalizes the usual Box-Cox transformation models. Many procedures have been suggested for estimating β in (1). Among them, Cheng et al. (1995) proposed the inverse censoring-probability weighted (ICPW) method for estimating β and studied the asymptotic properties of the resulting estimator. A key assumption in their work is that the censoring variable C is independent of covariates, which makes it possible to construct the Kaplan-Meier estimator for the censoring probability. The ICPW method was further studied by Cheng et al. (1997), Fine et al. (1998) and Cai et al. (2000). More recently, Chen et al. (2002) proposed a martingale representation based estimating equation approach for simultaneously estimating H and β in (1), where the covariate-independent censoring assumption was relaxed. In addition, Zeng and Lin (2006) studied the nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation for a more general class of linear transformation models that allow time-dependent covariates.

Despite these accomplishments, one limitation of linear transformation models is that all covariate effects are assumed to be linear. This assumption is sometimes too restrictive or unrealistic. For example, in the analysis of the lung cancer data from the Veteran’s Administration lung cancer trial (Kalbfleish and Prentice, 2002), the covariate age shows a strong nonlinear effect (U-shape) on the patient survival time. However, such an important effect may be missed by assuming the covariate effects to be linear (Tibshirani, 1997; Lu and Zhang, 2007). Another motivation for the need of partially linear transformation models is from the New York University women heath study (NYUWHS). In this study, one primary interest is to study the effects of sex hormone levels on the time of developing breast carcinoma, which usually show strongly nonlinear trends. The common practice is to break the continuous hormone levels into discrete quantiles (Zeleniuch-Jacquotte et al., 2004). However, such a discretization method can not make use of the entire data effectively, and more unpleasantly, the final fit can not retain the smooth curve of the nonlinear effect. Therefore, it is desired to provide a more powerful class of semiparametric survival models which can accommodate both linear and nonlinear covariate effects under one unified framework.

In this paper, we consider a class of partially linear transformation models and study their estimation and inference properties. In particular, we consider

| (2) |

where β is the vector of regression parameters for linear covariates and f is an unknown smooth function with f(0) = 0. Here the nonlinear covariate X is assumed to be univariate. Throughout the paper, we assume that the censoring variable C is independent of T given Z and X. There is a rich literature on studying the proportional hazards model with nonlinear or partially linear covariate effects (Hastie and Tibshirani, 1990; Gray, 1992; Sasieni, 1992; O’Sullivan, 1993; Grambsch and Therneau, 1994; Fan et al. 1997; Huang, 1999; Huang et al., 2000; Cai et al., 2007, 2008; among others) based on the partial likelihood function (Cox, 1975). Various nonparametric techniques including the kernel method, regression splines, smoothing splines and local polynomials were suggested for parameter estimation and inferences. However, relatively fewer methods have been developed for partially linear transformation models. Among them available, Ma and Kosorok (2005) studied the penalized log-likelihood estimation for the partially linear transformation model with current status data. The partially linear transformation model involves two nonparametric components H and f that need to be estimated under different constraints: the monotonicity on H and the smoothness on f. It is intriguing how to take into account both constraints seamlessly in the estimation.

In this paper we propose a system of martingale representation based global and local estimating equations to naturally deal with all these difficulties. Furthermore, under appropriate regularity conditions, we show that with a range of choices of the smoother parameter (the kernel bandwidth), the estimator of β is root-n consistent. The asymptotic normality is also obtained for the estimates of the linear and nonlinear parameters. The idea of the local estimating equation approach to nonparametric regression problems was pioneered by Carroll et al. (1998). It is also noted that our proposed estimating equations based method is related to some existing quasi/partial-likelihood based algorithms for partially linear models (Carroll et al. 1997; Cai et al., 2007, 2008). However, for partially linear transformation models, the need of estimating two nonparametric functions simultaneously imposes enormous challenges for both model estimation and inferences.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the global and local estimating equations for the parameters β, H and f in model (2), and we establish the asymptotic normality for the estimates of β. In addition, a new and simple resampling scheme is proposed to estimate the asymptotic variance of the resulting estimates. In Section 3, we conduct simulation studies to examine the finite-sample properties of the new estimator and further illustrate its performance via a real example. We give concluding remarks in Section 4. All technical proofs are relegated to an online supplementary appendix.

2. MODEL ESTIMATION AND INFERENCES

In this section, we propose a system of estimating equations based on the martingale representation to simultaneously estimate H, β, and f. The main motivation is to generalize the estimating equation method of Chen et al. (2002) for linear transformation models to partially linear transformation models. In order to estimate the extra nonparametric component f in (2), we use the local polynomial regression technique (Fan and Gijbels, 1996) to construct a set of locally-weighted estimating equations. As shown in the following, the new procedure naturally combines the global and local estimating equations in one unified framework, which greatly facilitates the computation and model inferences.

2.1 Global and Local Estimating Equations

Suppose there are n subjects in the study. Let Ti, Ci and be respectively the failure time, censoring time, and covariates of the ith subject, for i = 1, … ,n. The observations then consist of , i = 1, … ,n, which are independent copies of . Let and denote respectively the counting and at-risk processes of the ith subject. In addition, define

| (3) |

where Λ(·) is the known cumulative hazard function of ∊ and (β0, H0, f0) are the true values of (β, H, f). Then Mi(t) is a martingale process by the counting process theory (Fleming and Harrington, 1991; Andersen et al., 1993).

If the nonparametric function f were known, partially linear transformation models reduce to linear transformation models, and thus we can adopt the estimation equation suggested by Chen et al. (2002) to estimate β and H. Motivated by this, we first propose a set of “global estimating equations” to solve global parameters β and H, with f being fixed at its current value.

Global Estimating Equations

| (4) |

| (5) |

where . Note that (4) is a martingale difference equation used for estimating the transformation function H when β is fixed, while (5) is a martingale integral equation used for identifying β. The resulting estimate is a nondecreasing step function with jumps at the observed J failure times 0 < t1 < ⋯ < tJ < ∞ among the n observations.

Next, in order to estimate f, we approximate it locally by a linear function

for x in a neighborhood of u, where γ0(u) = f(u) and . The superscript dot denotes the first-order derivatives. Let K be a symmetric probability density function and Kh(t) = K(t/h)/h be the rescaled function of K, with h as the bandwidth parameter. Given β and H, we propose to solve the following kernel-weighted local estimating equations for f(·):

Local Estimating Equations

| (6) |

| (7) |

Altogether, we need to solve four estimating equations (4)-(7) iteratively: solve (4)-(5) for β and H with f being fixed, and solve (6)-(7) for f(·) with β and H fixed.

We now present an iterative algorithm to implement our estimation procedure. The algorithm is given as follows:

Step 0 (Initialization step). Choose an initial estimate . Solve (4) and (5) to obtain and using Chen et al. (2002) for linear transformation models. Set and .

Step 1. (Local estimation equation step) Fix and at their current values. For x = Xi, solve (6) and (7) by the Newton-Ralphson method to obtain and , for i = 1, … ,n.

Step 2. (Global estimation equation step) Update by solving the equations (4) and (5) by fixing , i = 1, … ,n.

Step 3. Repeat Steps 1 and 2 until convergence.

Step 4. Fix at its estimated value from Step 3. The final estimate of f(x) is , where are obtained by solving (6) and (7).

Remark 1

In the supplementary Appendix A, we propose a one-step estimator as the initial estimator and show its local consistency. In practice, to save the computation cost, one can posit a parametric form for f and estimate it using the method of Chen et al. (2002) for the linear transformation model to obtain .

Remark 2

The proposed algorithm above is in the similar spirit as Carroll et al. (1997) for generalized partially linear single-index models and Cai et al. (2007, 2008) for partially linear hazard regression models with multivariate survival data. All these algorithms, in their own contexts, alternatively optimize the global and local quasi-likelihood functions until convergence.

In the estimation procedure above, one needs to select the smoothing parameter h in Steps 1-3 and Step 4. It is worth noting that h plays different roles in different steps: in the first three steps, h should be chosen to ensure the proper estimation of β and H; in the last step, however, h should be optimal for estimating the nonparametric function f. Consequently, we suggest using one value of h in Steps 1-3 and using another value of h in Step 4. In the simulation section, we give more details on how to select the optimal h based on either the theoretical convergence rate or some data-adaptive tuning criteria.

2.2 Asymptotic Properties

In this section we establish the asymptotic properties of the estimators , , and . Let and . Following the notations used in Chen et al. (2002), for any t, s ∈ (0, τ], define

In addition, we define

where b⊗2 = bb’ for any vector b. For i = 1, … ,n, we further let

mZ(t) = α(t)λ*{H0(t)}/B2(t), and α(t) be a solution to the following Fredholm integral equation of the second kind:

| (8) |

where D1(·, ·), D2(·) and ρ(·) are defined in the supplementary Appendix B.

To derive the asymptotic properties of our estimators, we need the following regularity conditions:

(C1) The covariates Z and X are of compact support, and the density g(·) of X has a bounded second derivative.

(C2) β0 belongs to the interior of a known compact set , H0 has a continuous and positive derivative, and f0 has a continuous second derivative.

(C3) λ(·) is positive, ψ(·) is continuous, and limt→-∞ λ(t) = 0 = limt→-∞ ψ(t).

(C4) τ is finite with P(T > τ) > 0 and P(C > τ ) > 0.

(C5) There exist positive constants ζ0 and ζ1 such that supt∈[0, τ] B2(t) > ζ0 and supt∈[0, τ] {B2(t) + ∣B1(t)∣} ≤ ζ1.

(C6) The kernel D1(·, ·) in (8) satisfies .

(C7) The matrices A = A1 − A2 and Σ are finite and nondegenerate.

Remark 3

Conditions (C1)-(C5) are similar to those in Chen et al. (2002) for establishing asymptotic results for linear transformation models. Condition (C6) is used to assure that there exists a unique solution to the integral equation (8), which is usually satisfied when the covariates are bounded and also the functions f(·), λ(·) and are bounded on their supports. Condition (C7) is needed for establishing the asymptotic normality of the estimators.

The following theorems establish the asymptotic properties of , , and . The proofs of all theorems and the necessary regularity conditions are relegated to the supplementary Appendix B for ease of exposition.

Theorem 1

Under the regularity conditions (C1)-(C7), if nh2/{log(1/h)} → ∞ and nh4 → 0, we have that, given in a small neighborhood of β0, and

| (9) |

in distribution as n → ∞.

Theorem 2

Under the regularity conditions (C1)-(C7), if nh2/{log(1/h)} → ∞ and nh4 → 0, we have the asymptotic representation

for t ∈ (0, τ], where κi(t)’s are independent mean zero functions and their definitions are given in the supplementary Appendix B.

Theorem 3

Assume that conditions (C1)-(C4) hold. If nh5 is bounded, and β and H are estimated at the order Op(n−1/2), then

| (10) |

in distribution as n → ∞, where and the definitions of V1(x), V2(x) and bn(x) are given in the supplementary Appendix B.

Remark 4

Theorems 1 and 2 establish the root-n consistency of and , respectively. They are used to establish the standard nonparametric rate for the estimates of the nonlinear covariate effect presented in Theorem 3.

2.3 Estimation of Asymptotic Variance of

As shown in Theorem 1, the asymptotic variance of has a standard sandwich form A−1Σ(A−1)’. However, the matrices A and Σ are of complicated analytic forms and their computation requires one to solve the Fredholm integral equation (8), which is often difficult and unstable even for a moderate sample size. Therefore, it is desired to have a feasible computation approach to approximate the asymptotic variance of . In this section, we propose to use a resampling scheme (Jin et al., 2001) to approximate the asymptotic distribution of .

The resampling algorithm proceeds as follows. First, we generate n i.i.d. exponential random variables {ξi, i = 1, … , n} with mean 1 and variance 1. Fixing data at their observed values, we solve the following ξi-weighted estimation equations and denote the solutions as β*, H*(t) and f*(x):

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

The estimates β*, H* and f*(x) can be obtained using the same iterative algorithm proposed in Section 2.2. In the following theorem, we establish the validity of the proposed resampling method.

Theorem 4

Under the regularity conditions (C1)-(C7) and the same rate of h, the conditional distribution of given the observed data converges almost surely to the asymptotic distribution of .

Based on Theorem 4, by repeatedly generating {ξ1, … ,ξn} many times, we may obtain a large number of realizations of β*. The variance estimate of can then be obtained by referring to the empirical distribution of β*.

3. NUMERICAL STUDIES

3.1 Simulation

We examine in this section the finite sample performance of the proposed estimators. The failure times Ti’s are generated from the partially linear transformation model (2). For the linear component, two independent covariates (Zi1, Zi2) are considered, where Zi1’s are generated from a Bernoulli distribution with the success probability 0.5 and Zi2’s are from a uniform distribution on (0, 1); for the nonlinear component, a scalar covariate Xi is generated from a uniform distribution on (0, 1) and is independent of (Zi1, Zi2). We take β0 = (−1, 1)’ and consider two designs for the nonparametric function:

Design I: f(x) = 8(x − x3),

Design II: f(x) = 0.05{exp(3x) − 1}.

The hazard function of the error term ∊ is chosen as

with ζ = 0, 1, 0.5 (Dabrowska and Doksum, 1988). Note that the partially linear proportional hazards (PLPH) and the partially linear proportional odds (PLPO) models correspond to ζ = 0 and ζ = 1, respectively. The function H(t) is chosen respectively as log(t) for ζ = 0, log(et − 1) for ζ = 1, and log(2e0.5t − 2) for ζ = 0.5.

We consider two types of censoring mechanisms: covariate-independent censoring and covariate-dependent censoring. For covariate-independent censoring, the censoring times Ci’s are generated from a uniform distribution on (0, c0); for covariate-dependent censoring, Ci’s are generated from exponential distributions with the means exp(c0 + c1Zi1). Here the constants c0 and c1 are chosen to achieve the desired censoring level 20% or 40%. In each scenario, we conduct 500 runs of simulations with the sample size n = 100 and 200.

In our computational algorithm, we choose the initial values as . For the estimation of the parametric component, we set the bandwidth parameter h = α1n−1/3 as suggested by the asymptotic theory. We have tried various values of α1 from 0.01 to 0.5, and found that α1 = 0.05 works very well under all the scenarios. Therefore, we only report the simulation results based on this choice. In practice, we may also use a similar cross-validation method as that of Tian et al. (2005) for the kernel estimation of the proportional hazards model with time-varying coefficients to choose the optimal bandwidth based on estimating equations. In order to assess the performance of the proposed resampling method for variance estimation, we generated M = 500 sets of ξ’s for each simulated data and computed the asymptotic variance estimates of based on the empirical variance of β*’s. The estimation results for β with n = 100 under the covariate-independent and covariate-dependent censoring schemes are summarized respectively in Tables 1 and 2. It is clear that the proposed estimators are nearly unbiased in all simulated scenarios, and the proposed asymptotic standard error (SE) estimates based on the resampling method match those sample standard deviations (SD) of the parameter estimates reasonably well. Furthermore, the Wald-type 95% confidence intervals have proper converge probabilities. We also reported the averaged Monte Carlo standard errors of Bias, mean squared error (MSE) of estimates, and SE/SD for each model. Here the Monte Carlo standard errors of SE/SD were computed using the Jackknife method.

Table 1.

Simulation results for covariates-independent censoring.

| β01 = −1.0 | β02 = 1.0 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Design | Prop. | Bias | MSE | SE/SD | CP | Bias | MSE | SE/SD | CP |

| ζ = 0 | I | 20% | 0.004 | 0.060 | 0.947 | 0.930 | 0.036 | 0.140 | 1.011 | 0.944 |

| 40% | −0.012 | 0.082 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 0.044 | 0.198 | 1.000 | 0.946 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.053 | 0.074 | 0.921 | 0.934 | 0.086 | 0.166 | 0.987 | 0.942 | |

| 40% | −0.065 | 0.094 | 0.957 | 0.944 | 0.083 | 0.212 | 1.015 | 0.954 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.033 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| ζ = 1 | I | 20% | −0.033 | 0.177 | 0.919 | 0.924 | 0.004 | 0.460 | 0.934 | 0.932 |

| 40% | −0.035 | 0.183 | 0.958 | 0.940 | −0.002 | 0.475 | 0.981 | 0.960 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.061 | 0.188 | 0.926 | 0.922 | 0.026 | 0.468 | 0.952 | 0.942 | |

| 40% | −0.077 | 0.198 | 0.952 | 0.932 | 0.004 | 0.471 | 0.997 | 0.946 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.019 | 0.013 | 0.031 | 0.031 | 0.029 | 0.030 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| ζ = 0.5 | I | 20% | −0.021 | 0.110 | 0.927 | 0.926 | 0.004 | 0.287 | 0.929 | 0.930 |

| 40% | −0.032 | 0.128 | 0.955 | 0.942 | 0.002 | 0.318 | 0.988 | 0.964 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.063 | 0.124 | 0.925 | 0.928 | 0.033 | 0.302 | 0.944 | 0.936 | |

| 40% | −0.081 | 0.144 | 0.946 | 0.928 | 0.027 | 0.320 | 1.005 | 0.956 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.016 | 0.009 | 0.032 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.030 | |||

SD, sample standard deviation; SE, mean of estimated standard error via resampling method; CP, empirical coverage probability of 95% confidence intervals; MSE, mean squared error of estimates; Prop.: censoring proportion; Avg. MCSE, averaged Monte Carlo standard errors of Bias, MSE and SE/SD for each model.

Table 2.

Simulation results for covariates-dependent censoring.

| β01 = −1.0 | β02 = 1.0 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Design | Prop. | Bias | MSE | SE/SD | CP | Bias | MSE | SE/SD | CP |

| ζ = 0 | I | 20% | 0.004 | 0.059 | 0.955 | 0.944 | 0.025 | 0.159 | 0.942 | 0.940 |

| 40% | −0.026 | 0.087 | 0.946 | 0.938 | 0.027 | 0.227 | 0.943 | 0.946 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.059 | 0.073 | 0.943 | 0.930 | 0.080 | 0.174 | 0.963 | 0.928 | |

| 40% | −0.065 | 0.102 | 0.939 | 0.916 | 0.050 | 0.244 | 0.947 | 0.956 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.014 | 0.032 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| ζ = 1 | I | 20% | −0.022 | 0.168 | 0.927 | 0.934 | 0.047 | 0.444 | 0.938 | 0.938 |

| 40% | −0.045 | 0.189 | 0.961 | 0.930 | 0.018 | 0.536 | 0.936 | 0.936 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.055 | 0.184 | 0.927 | 0.918 | 0.043 | 0.478 | 0.929 | 0.938 | |

| 40% | −0.065 | 0.195 | 0.957 | 0.936 | 0.048 | 0.531 | 0.945 | 0.936 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.030 | 0.031 | 0.030 | 0.028 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| ζ = 0.5 | I | 20% | −0.027 | 0.113 | 0.925 | 0.932 | 0.018 | 0.288 | 0.937 | 0.934 |

| 40% | −0.036 | 0.129 | 0.972 | 0.946 | 0.026 | 0.369 | 0.936 | 0.934 | ||

| II | 20% | −0.060 | 0.123 | 0.936 | 0.940 | 0.043 | 0.306 | 0.940 | 0.934 | |

| 40% | −0.068 | 0.139 | 0.976 | 0.944 | 0.048 | 0.364 | 0.967 | 0.940 | ||

| Avg. | MCSE | 0.016 | 0.008 | 0.031 | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.030 | |||

SD, sample standard deviation; SE, mean of estimated standard error via resampling method; CP, empirical coverage probability of 95% confidence intervals; MSE, mean squared error of estimates; Prop.: censoring proportion; Avg. MCSE, averaged Monte Carlo standard errors of Bias, MSE and SE/SD for each model.

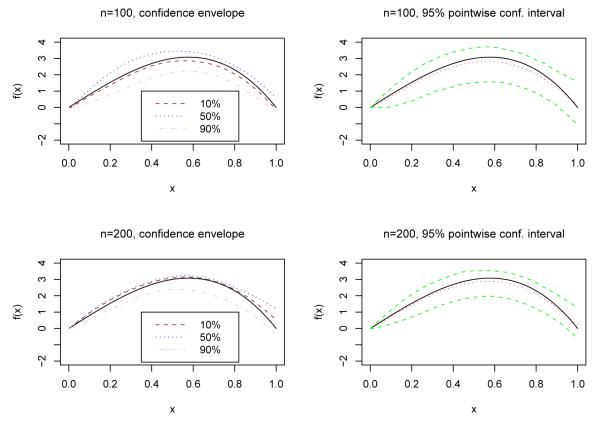

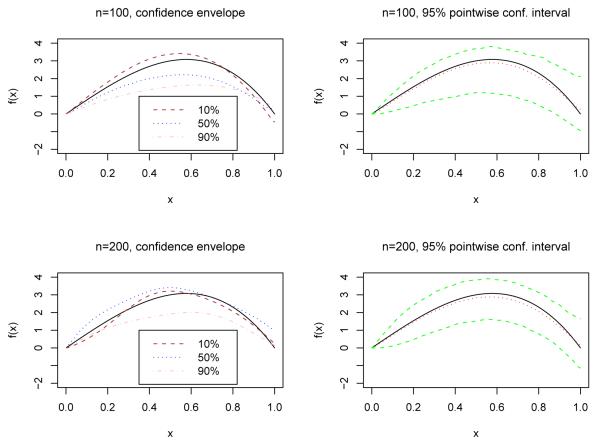

For the estimation of the nonparametric function f, a finer tuning with the mean integrated squared error (MISE) score was conducted. In particular, we set h = α2n−1/5, where α2 = 0.5, 0.25, 0.1, 0.05, 0.025 and selected the optimal α2 by minimizing the MISE. Here we only present the results for design I under the PLPH and PLPO models. The results for design II and the model corresponding to ζ = 0.5 are quite similar and hence omitted. To present the performance of our procedure of nonparametric estimation, we plot the estimated functions for the PLPH model obtained under various scenarios in Figure 1. The left column of Figure 1 depicts the typical estimated functions corresponding to the 10th best, the 50th best (median), and the 90th best according to MISE among 500 simulations. The top plot is for n = 100 and the bottom plot is for n = 200. It is evident that the estimated curves are able to capture the shape of the true function very well, and their performance improves when the sample increases. In order to describe the sampling variability of the estimated nonparametric function at each point, we also depict a 95% pointwise confidence interval for f in the right column of Figure 1. The upper and lower bound of the confidence interval are respectively given by the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the estimated function at each grid point among 500 simulations. The results show that the function f is estimated with reasonably good accuracy. As the sample size increases from 100 to 200, the confidence interval becomes narrower as expected. In Figure 2, we plot the estimated nonparametric function and the associated 95% pointwise confidence interval for the PLPO model. Similar conclusions as the PLPH model can be drawn from Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The estimated nonlinear function, confidence envelop and 95% point-wise confidence interval for the PLPH model.

Figure 2.

The estimated nonlinear function, confidence envelop and 95% point-wise confidence interval for the PLPO model.

In order to examine the numerical stability and efficiency of the proposed iterative algorithm, we also conducted several simulations to study: (i) the effects of different initial values for the nonlinear covariate on the solution; and (ii) how much efficiency is lost if the true covariate effect is linear while the proposed method is used. The results are presented in the supplementary Appendix C. Based on these results, we observe that the estimated linear parameters produced from different initial values are quite similar to each other and close to the truth, and the efficiency loss of our method is relatively small compared with that of Chen et al. (2002) for the linear transformation model when the true covariate effects are really linear.

3.2 Application to lung cancer data

In this section, we apply our method to the lung cancer data from the Veteran’s Administration lung cancer trial (Kalbfleishch and Prentice, 2002). In this trial, 137 males with advanced inoperable lung cancer were randomized to either a standard treatment or chemotherapy. Besides the treatment indicator, there were five covariates: Cell type (1=squamous, 2=small cell, 3=adeno, 4=large), Karnofsky score, Months from Diagnosis, Age, and Prior therapy (0=no, 10=yes). The data set has been analyzed by many authors, for example, Tibshirani (1997) fitted the proportional hazards model and Lu and Zhang (2007) considered the proportional odds model. They found that both Cell type and Karnofsky score were significant while others were not. In both methods, all covariates were assumed linear, which may not be true, particularly for the age effect. It is well known that age is a complex confounding factor, and its effect usually shows a nonlinear trend.

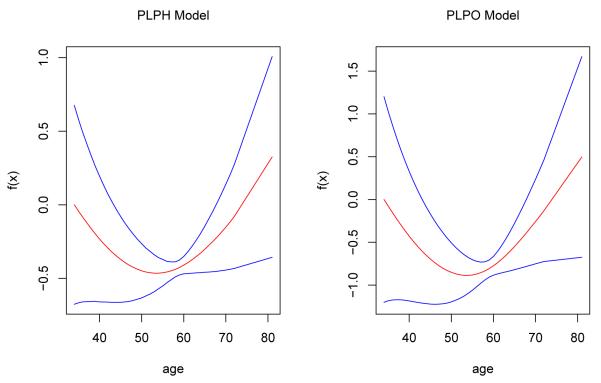

We fitted both the PLPH and PLPO models to the data with three covariates: treatment, cell type and age, where age is assumed to be nonlinear. For estimation, we first rescaled age between 0 and 1, and set h = 0.05n−1/3 as in simulations. Table 3 summarizes the estimated coefficients and their standard errors obtained based on 500 resamplings for both models. As found in the literature, Cell type (small vs large, adeno vs large) is significant while treatment is not in both models. Moreover, Figure 3 gives the estimates of the nonlinear components: the left panel for the PLPH model and the right panel for the PLPO model. The red curves are estimated nonparametric functions and the blue curves are the 95% point-wise confidence intervals constructed based on the resampling method. Based on the plots, the covariate age showed clearly a nonlinear effect (U-shape) on survival times. It is noted that the zero line is not included in the 95% confidence intervals. This example suggests that the partially linear transformation models can be more powerful in discovering significant covariates than those assuming simply linear covariate effects.

Table 3.

Estimates and standard errors of linear coefficients for lung cancer data.

| Covariate | PLPH | PLPO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Treatment | 0.182 | 0.192 | 0.191 | 0.335 |

| squamous vs large | −0.307 | 0.255 | −0.514 | 0.476 |

| small vs large | 0.723 | 0.235 | 1.375 | 0.425 |

| adeno vs large | 0.808 | 0.234 | 1.440 | 0.410 |

Est., estimates of regression coefficients; SE, estimated standard errors based on 500 resamplings.

Figure 3.

The estimated nonlinear function and its 95% point-wise confidence interval.

4. DISCUSSION

We study a general class of partially linear transformation models, and develop the corresponding inference procedure by solving a unified global and local estimating equation system based on the martingale representation. We established the root-n consistency and asymptotical normality for the estimates of regression coefficients, and studied the convergence rates of the estimates for nonparametric components including the transformation function and nonlinear covariate effect. We also provide consistent estimates for the asymptotic variance of the regression coefficient estimates based on a feasible resampling scheme. It is noted that the proposed martingale-based estimating equations are ad hoc and are generally not efficient. Recently, Chen (2009) proposed a nice approach using the weighted Breslow-type estimator to construct efficient estimating equations for the linear transformation model. It is interesting to explore whether such an approach can be generalized to the partially linear transformation model. A thorough investigation is warranted for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor, an associate editor, and two referees for their constructive comments and suggestions, and Professor Kani Chen for inspiring discussions on the consistency of the proposed estimators. This research was partially supported by the NSF awards DMS-0504269 and DMS-0645293, and the NIH awards R01 CA-085848 and R01 CA-140632.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS Extended Derivations and Additional Simulation Results: The pdf file contains extended derivations of theoretical properties and additional simulation results. (jasa_plt_suppl_rev2.pdf)

Contributor Information

Wenbin Lu, (wlu4@stat.ncsu.edu), Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695..

Hao Helen Zhang, (hzhang2@stat.ncsu.edu), Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695..

REFERENCES

- Andersen PK, Borgan O, Gill R, Keiding N. Statistical Models Based on Counting Processes. Springer; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S. Analysis of survival data by the proportional odds model. Statist. Med. 1983;2:273–277. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780020223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel PJ, Klaassen CAJ, Ritov Y, Wellner JA. Efficient and Adaptive Estimation for Semiparametric Models. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Fan J, Jiang J, Zhou H. Partially linear hazard regression for multivariate survival data. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 2007;102:538–551. [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Fan J, Jiang J, Zhou H. Partially linear hazard regression with varying-coefficients for multivariate survival data. J. R. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 2008;70:141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Wei LJ, Wilcox M. Semi-Parametric Regression Analysis for Clustered Failure Time Data. Biometrika. 2000;87:867–78. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RJ, Fan J, Gijbels I, Wand MP. Generalized partially linear single-Index models. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1997;92:477–489. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RJ, Ruppert D, Welsh A. Local estimating equations. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1998;93:214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Jin Z, Ying Z. Semiparametric analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika. 2002;89:659–668. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-H. Weighted Breslow-type and maximum likelihood estimation in semi-parametric transformation models. Biometrika. 2009;96:591–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SC, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Analysis of transformation models with censored data. Biometrika. 1995;82:835–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SC, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Prediction of survival probabilities with semi-parametric transformation models. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1997;92:227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton D, Cuzick J. Multivariate generalizations of the proportional hazards model (with Discussion) J. R. Statist. Soc. Ser. A. 1985;148:82–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables (with discussion) J. R. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 1972;81:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Partial Likelihood. Biometrika. 1975;62:269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska DM, Doksum KA. Estimation and testing in the two-sample generalized odds rate model. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1988;83:744–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Gijbels I. Local Polynomial Modeling and Its Applications. Chapman and Hall; London: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Gijbels I, King M. Local likelihood and local partial likelihood in hazard regression. Ann. Statist. 1997;25:1661–1690. [Google Scholar]

- Fine J, Ying Z, Wei LJ. On the linear transformation model for censored data. Biometrika. 1998;85:980–986. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming TR, Harrington DP. Counting Processes and Survival Analysis. Wiley; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Grambsch P, Therneau T. Proportional hazards tests and diagnostics based on weighted residuals. Biometrika. 1994;81:515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Gray RJ. Flexible methods for analyzing survival data using splines, with application to breast cancer prognosis. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1992;87:942–951. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Generalized additive models. Chapman & Hall; 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J. Efficient estimation of the partially linear Cox model. Ann. Statist. 1999;27:1536–1563. [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Kooperberg C, Stone C, Truong Y. Functional ANOVA modeling for proportional hazards regression. Ann. Statist. 2000;28:961–999. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Ying Z, Wei LJ. A simple resampling method by perturbing the minimand. Biometrika. 2001;88:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbfleish JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Edition 2 Wiley; New Jersey: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Zhang HH. Variable selection for proportional odds model. Stat. Med. 2007;26:3771–3781. doi: 10.1002/sim.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Kosorok MR. Penalized log-likelihood estimation for partly linear transformation models with current status data. Ann. Statist. 2005;33:2256–2290. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan F. Nonparametric estimation in the Cox model. Ann. Statist. 1993;27:124–145. [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt AN. Inference for the linear model using a likelihood based on ranks. J. R. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 1982;44:234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Pettitt AN. Proportional odds model for survival data and estimates using ranks. Appl. Statist. 1984;33:169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard D. Empirical Processes: Theory and Applications. NSF-CBMS Regional Conference Series in Probability and Statistics Volume 2. Hayward: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sasieni P. Information bounds for the conditional hazard ratio in a nested family of regression models. J. R. Statist. Soc. Ser. B. 1992;54:627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Shorack GR, Wellner JA. Empirical Processes with Applications to Statistics. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Zucker D, Wei LJ. On the Cox model with time-varying regression coefficients. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 2005;100:172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. The lasso method for variable selection in the Cox model. Statist. Med. 1997;16:385–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970228)16:4<385::aid-sim380>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart AW, Wellner JA. Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes: With Applications to Statistics. Springer; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Shore RE, Koenig KL, Akhmedkhanov A, Afanasyeva Y, Kato I, Kim MY, Rinaldi S, Kaaks R, Toniolo P. Postmenopausal levels of oestrogen, androgen and SHBG and breast cancer: long-term results of a prospective study. Brit. J. of Can. 2004;90:153–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Lin D. Efficient estimation of semiparametric transformation models for counting processes. Biometrika. 2006;93:627–640. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.