Expression patterns of genes at the synapses (or neuromuscular junctions) of extraocular muscles are described by using microarray expression profiling to understand the molecular makeup of the synapses of these small and specialized sets of skeletal muscles. The extraocular muscle synapses expressed genes that are also expressed in limb muscle synapses, but several genes were identified at the same time that showed unique differential regulation patterns compared with limb synapses.

Abstract

Purpose.

To examine and characterize the profile of genes expressed at the synapses or neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) of extraocular muscles (EOMs) compared with those expressed at the tibialis anterior (TA).

Methods.

Adult rat eyeballs with rectus EOMs attached and TAs were dissected, snap frozen, serially sectioned, and stained for acetylcholinesterase (AChE) to identify the NMJs. Approximately 6000 NMJs for rectus EOM (EOMsyn), 6000 NMJs for TA (TAsyn), equal amounts of NMJ-free fiber regions (EOMfib, TAfib), and underlying myonuclei and RNAs were captured by laser capture microdissection (LCM). RNA was processed for microarray-based expression profiling. Expression profiles and interaction lists were generated for genes differentially expressed at synaptic and nonsynaptic regions of EOM (EOMsyn versus EOMfib) and TA (TAsyn versus TAfib). Profiles were validated by using real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR).

Results.

The regional transcriptomes associated with NMJs of EOMs and TAs were identified. Two hundred seventy-five genes were preferentially expressed in EOMsyn (compared with EOMfib), 230 in TAsyn (compared with TAfib), and 288 additional transcripts expressed in both synapses. Identified genes included novel genes as well as well-known, evolutionarily conserved synaptic markers (e.g., nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR) alpha (Chrna) and epsilon (Chrne) subunits and nestin (Nes).

Conclusions.

Transcriptome level differences exist between EOM synaptic regions and TA synaptic regions. The definition of the synaptic transcriptome provides insight into the mechanism of formation and functioning of the unique synapses of EOM and their differential involvement in diseases noted in the EOM allotype.

The extraocular muscles (EOMs) are a group of highly specialized skeletal muscles that are essential in the locating and precise tracking of objects by the visual system.1,2 To fulfill their roles in eye movements including vergence, pursuit, saccadic eye movements, and optokinetic and vestibulo-ocular reflexes, they combine fast contractile properties and high oxidative capacity with high fatigue resistance. This combination of properties is unusual among skeletal muscles.

The differences between EOMs and other skeletal muscles are so marked that Hoh and Hughes3 suggested the term allotype to define a unique, functional niche for these muscles. Previous studies from our laboratory and others have demonstrated that EOMs have a unique transcriptome and proteome.4–10 The enormous differences are also reflected in their altered response to various diseases. Although EOMs are spared during the course of Duchenne's muscular dystrophy,11,12 they show a predilection for involvement in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy,13 mitochondrial myopathies, Grave's Disease, and IBM3, a form of inclusion body myositis.14 The early involvement of EOMs in acquired autoimmune myasthenia gravis (MG) and congenital myasthenic syndromes has also been noted and well studied.15–19

EOMs are innervated by cranial nerves, rather than by motoneurons of the spinal cord. The oculomotor motoneurons exhibit discharge rates that are an order of magnitude higher than those of motoneurons to limb muscles,20,21 and it has been suggested that this neuron activity significantly shapes their unusual fiber type content. Moreover, EOMs in organ culture can be maintained by explants of midbrain (containing appropriate oculomotor motoneurons), but not by explants of spinal cord, suggesting that trophic requirements of EOMs are different from those of skeletal muscle.22 The severe atrophy, degeneration, and fibrosis of EOMs in several of the congenital fibroses of the EOMs are also due to failure of proper neuromuscular interactions.23

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the connection between the motorneuron and the skeletal muscle and has been the paradigm for investigating the assembly, structure, and function of the synapse.24 In adult muscles, mRNAs encoding a number of molecules expressed at the NMJ are selectively transcribed by a small number of spatially restricted subsynaptic nuclei. These include subunits of the acetylcholine receptors (AChRs), utrophin, sodium channels, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), and even transforming growth factor-β.25,26 These molecules, however, may be only a small subset of those that show restricted synthesis by subsynaptic nuclei. Nazarian et al.27 isolated the NMJs of mouse TA muscle by laser capture microdissection (LCM) and used expression profiling to compare molecules expressed by subsynaptic nuclei with those expressed by extrajunctional nuclei. Their analysis generated a list of 143 genes that showed increased expression at the NMJ. In addition to genes known to be expressed preferentially at NMJs they identified a large number of novel NMJ-associated genes. They concluded that many, if not most, of the NMJ specific molecules are yet to be discovered. Confirmation of this potentially vast pool of previously unknown NMJ-specific molecules comes from other microarray analyses of mRNAs enriched in the postsynaptic domain of murine NMJs.28–30 Similarly, in an RNAi study of genes involved in synaptic transmission in Caenorhabditis elegans,31 most of the genes identified had not been implicated in synaptic transmission.

Given the large number of established distinctions between EOMs and other skeletal muscles, it may not be surprising that the NMJs of EOMs also differ from those in skeletal muscle. They do contain, in addition to the singly innervated fibers typical of skeletal muscles, multiply innervated fibers (MIFs). Moreover the coexpression of adult and fetal AChR isoforms, the conspicuous sparseness of subjunctional folds and the altered location of some components of the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex are special features found in the NMJ of EOMs.32–34 Yet, very little is known of their molecular makeup at the transcriptome level.

We used LCM and gene microarray (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) analyses to examine and define mRNA expression patterns associated with EOM NMJs and to compare this with gene expression of NMJs from a fast limb skeletal muscle, the tibialis anterior (TA). The results emphasize the unique properties of the EOM allotype.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Preparation

Animals were maintained and handled in accordance with regulations of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and were used in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Six adult rats (males and females, 3–6 months old, 250–400 g weight) were killed by CO2 inhalation. The eyeballs with muscles attached were dissected, covered with OCT tissue-embedding medium (Tissue-Tek; Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen–cooled isopentane, and stored at −80°C. The TA muscles of all rats were dissected and frozen in the same way. Eyeballs with rectus EOMs attached and TAs were cut transversely into 10-μm sections with a cryostat (Microm HM500; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Oberkochen, Germany), mounted on PEN (poly-ethylene-naphthalene) membrane slides (Arcturus, Sunnyvale, CA). Unfixed sections were stored at −80°C until needed.

LCM and RNA Isolation

NMJs were visualized by staining sections for AChE.35 A sample isolation system (PALM MicroBeam; Carl Zeiss Meditec) was used for laser-based microdissection and for catapulting isolated tissue into a microfuge cap containing 80 μL lysis buffer (RLT; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Figure 1 demonstrates the distinction between synaptic and nonsynaptic regions in the first column. The second column shows the identified regions after being cut with the isolation system. The third column shows sections after isolation and collection of the cut regions into microtubes containing lysis buffer. Approximately 1000 NMJs and an equal amount of nonsynaptic regions were collected from each muscle sample. Well-defined EOM NMJs were collected, mainly from the midbelly region from the orbital and global layers, without discrimination between the MIFs and singly innervated fibers (SIFs). The precision of the LCM technique, the paucity of NMJ regions in the muscle, and the classic chevron morphology of NMJs as determined by staining serial sections (Supplementary Fig. S1, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/full/51/9/4589/DC1) suggests that the cross contamination by NMJ material in non-NMJ samples was minimal, less than the contribution of non-NMJ material in the NMJ samples. To avoid RNA degradation, we completed the whole procedure from thawing of the sections to freezing the tube with the captured tissue within 2 hours. Total RNA was isolated from each captured set with a kit (RNeasy; Qiagen). The purity and concentration of total RNA were determined with a spectrophotometer (ND-1000; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE); 260/280 ratios were between 1.8 and 2.1. The RNA samples used had single peaks for the 18S and 28S bands, as determined by a bioanalyzer (model 2100; Agilent Technologies Inc., Palo Alto, CA).

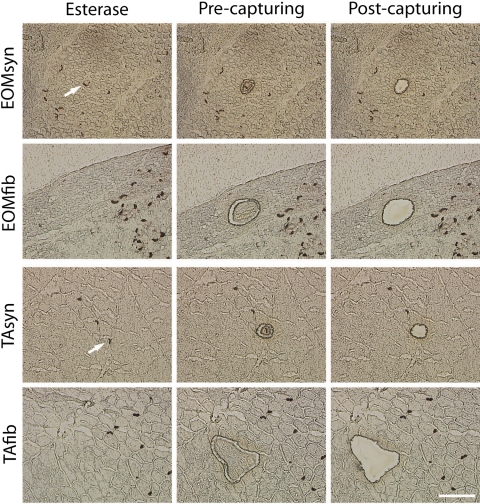

Figure 1.

Microdissection of fibers and synaptic (NMJ) regions of EOM and TA with a microdissection system. AChE staining was used to visualize NMJ on 10-μm cryosections. The first column shows EOM and TA before microdissection. White arrow: the NMJ that is to be captured. A focused laser microbeam was used to cut around the target cell or cell cluster without touching the structures of interest as shown in the second column. A small joint of 1 μm was left. To transfer the cell cluster into a collection device, a defocused laser with slightly increased energy was directed at the remaining joint region and its energy used to catapult the cells into a cap with lysis buffer. The third row shows EOM and TA after LCM. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Linear Amplification and cRNA Labeling

Total RNAs were used to generate double-stranded cDNA with the T7-oligo (dT) primer according to the microarray (GeneChip; Affymetrix) two-cycle target-labeling protocol as described by the manufacturer. First-cycle amplified RNAs (i.e., aRNAs) were normalized to 600 ng for further amplification and labeling. Two rounds of in vitro transcription were performed yielding labeled cRNA (260/280 ratios were 1.9–2.1).

Microarray Hybridization

cRNA of four EOM and TA synapse and four EOM and TA fiber samples were used for hybridization to a rat microarray containing 31,099 probe sets (Rat 230 ver. 2.0 GeneChip; Affymetrix, Inc.) and scanned with a gene array scanner (model G2500A; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Raw intensities for each probe set were stored in electronic format (GeneChip Operating System ver. 1.1, GCOS1.1; Affymetrix, Inc.).

Microarray Statistical Analysis

The raw data (16 Affymetrix cell files) were imported into a statistical analysis and data mining program (Genomics Suite version 6.4; Partek, St. Louis, MO) where a GC-RMA algorithm was applied to yield log signal values. Four individual pair-wise comparisons (EOMsyn versus EOMfib, TAsyn versus TAfib, EOMfib versus TAfib, and EOMsyn versus TAsyn) were performed with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05 and an additional twofold cutoff filter. A three-way ANOVA using the interaction term across the four groups of samples (EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, TAfib) was used to create the interaction list with an FDR of 0.01. Visualization of the relationships between the samples was achieved by using principal component analysis (PCA) and unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Affymetrix databases (NetAffix) and the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) were used for assigning functional annotations.

qPCR Validation

First-round amplified cRNA of two independent samples was used for validation of the interaction list and second-round cRNA for validation of pair-wise comparisons. Rat gene expression profiling assays (TaqMan rat Assays-on-Demand; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) for Chrne (Rn00567899_m1), Nes (Rn00564394_m1), calsenilin (Csen) (Rn00583484_m1), myosin heavy chain 13 (Myh13) (Rn01461489_m1), myosin heavy chain 8 (Myh8) (Rn01751718_g1), N-myc down-stream regulated gene 4 (Ndrg4) (Rn00582990_m1), SET and MYND domain containing 2 (Smyd2) (Rn01412513_m1), myomesin 2 (Myom2) (Rn01478731_m1), homeobox 10a (Hox10a) (Rn01410200_m1), regulator of calcineurin 2 (Rcan2) (Rn00598058_m1), prominin 2 (Prom2) (Rn00593883_m1), carbonic anhydrase 3 (Ca3) (Rn00695939_m1), aquaporin 4 (Aqp4) (Rn00563196_m1), solute carrier family 24 member 2 (Slc24a2) (Rn00582020_m1), integrin beta 5 (Itgb5) (Rn00595859_m1), calmodulin-like 4 (Calml4) (Rn01421995_m1), and glia maturation factor gamma (Gmfg) (Rn00710432_m1) were used to quantify the expression on a real-time PCR system (model 7300; Applied Biosystems) for these genes. Data of each primer set were normalized against β-actin (Rn00667869_m1) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Rn99999916_s1) as the reference gene, and change ratios were calculated employing the ΔΔCT method.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections 10 μm thick were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100/PBS and blocked in 10% goat serum/PBS. Primary antibodies (anti-Itgb5 or anti-Slc24a2; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were incubated overnight, followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 488 secondary antibodies and Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were obtained using a fluorescence microscope (BX 51; Olympus, Center Valley, PA) equipped with a camera (Magnafire; Olympus).

Results

Expression Profiling of EOM and TA Synapses and Fibers

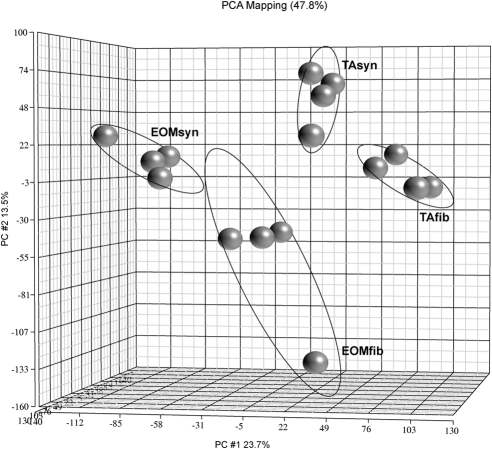

Four independent RNA preparations (EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, and TAfib) were prepared for each of the four animals, resulting in a total of 16 samples for screening experiments. Samples were processed and hybridized to a rat microarray (Rat Expression Arrays 230 version 2.0; Affymetrix). A PCA plot showed three-dimensional visualization of the relationships between the samples (Fig. 2), on the basis of the expression levels of 20,266 detected probe sets. The four different tissue types clearly clustered into distinct areas, indicating a difference in the molecular makeup between them.

Figure 2.

PCA and 3D visualization of EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, and TAfib microarray data. Shown is the 3D scatterplot of the PCA performed on the samples. Each gray ball represents gene clustering of a replicate of each sample (i.e., the EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, or TAfib gene microarray), not a gene. Ellipses around the groups represent an SD of 2. PCA captured 47.8% of the variation observed in the experiment in the first three principal components, which are plotted on the x, y, and z axes, representing the largest fraction of the overall variability in samples.

We generated five sets of gene profiles: Four sets of pair-wise comparisons (sets 1–4; Supplementary Tables S1–S4, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/full/51/9/4589/DC1) and an interaction list (set 5; Supplementary Table S5) which shows the most significant differentially expressed genes for each tissue type after comparing the four tissues with each other. All primary data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE15737, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; provided in the public domain by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD).

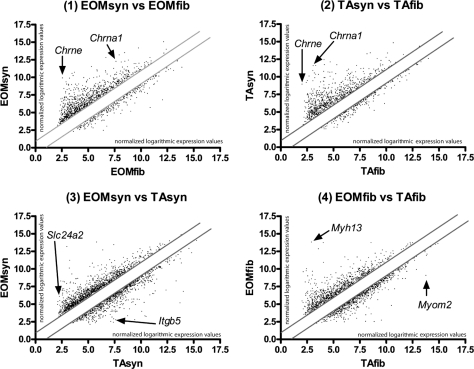

The EOMsyn versus EOMfib (set 1) profile shows 927 transcripts upregulated and 300 transcripts downregulated in EOM synapses versus EOM nonsynaptic regions; these represent 2.98% and 0.97% of the probe sets screened. The comparison of TAsyn versus TAfib (set 2) showed 763 transcripts up- and 233 transcripts downregulated in TA synapses versus the TA nonsynaptic regions, representing 2.45% and 0.75% of the probe sets. The comparison of EOMsyn versus TAsyn (set 3) showed 1195 transcripts up- and 830 transcripts downregulated in EOMsyn versus TAsyn, representing 3.84% and 2.67% of the probe sets. Finally, a comparison of EOMfib versus TAfib (set 4) revealed 830 transcripts up- and 707 transcripts downregulated in EOM nonsynaptic regions versus TA nonsynaptic regions, representing 2.67% and 2.27% of the total number of probe sets (Supplementary Tables S1–S4). The scattergraphs in Figure 3 show the expression levels of the transcripts differentially expressed in these comparisons.

Figure 3.

Scattergram analysis of expression profiling. The four scattergraphs represent the four sets of expression profiling experiments undertaken in this study. Axes show logarithmic expression levels of each gene on a linear scale. The graphs compare the expression profiling data sets for the following independent samples/conditions: (1) EOMsyn versus EOMfib, (2) TAsyn versus TAfib, (3) EOMsyn versus TAsyn, and (4) EOMfib versus TAfib. Solid gray lines: a twofold cutoff. Genes situated farthest from the diagonal showed greatest expression differences between the two expression profiling data sets compared in each graph. (1, 2) The synaptic markers Chrna1 and Chrne upregulated in both EOMsyn and TAsyn. Examples of differentially expressed genes in (3) EOMsyn versus TAsyn are Slc24a2 and Itgb5. Myh13 was upregulated in EOMfib; Myom2 was downregulated in EOMfib (4).

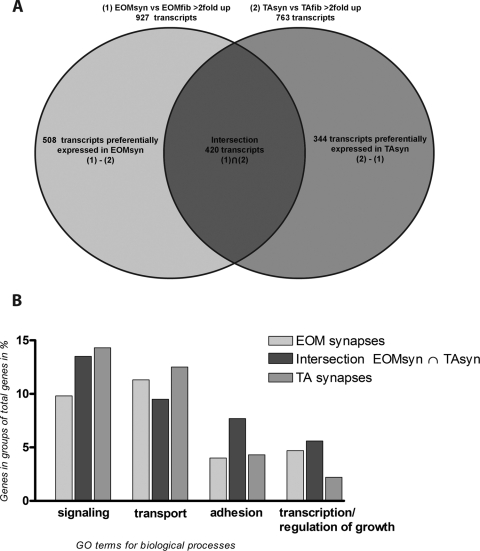

Because of the limitations of LCM, a minor degree of contamination of synaptic preparations with nonsynaptic regions was inevitable. Therefore, not only genes that are known to be expressed in synaptic regions, like Chrne or Chrna but some fiber components, such as Myh13, Myh8, and cardiac alpha actin 1 were present in the comparison of EOMsyn versus TAsyn (set 3). We therefore decided to focus on the comparisons EOMsyn versus EOMfib (set 1) and TAsyn versus TAfib (set 2), to determine genes and groups of genes involved in biological processes that are preferentially expressed in either of the synapses (TA or EOM). Transcripts with more than twofold upregulation in these profiles (sets 1 and 2) would be enriched in synapses and therefore used for further investigation. The Venn diagram in Figure 4A demonstrates which genes are common to both sets (intersection of 1 vs. 2; 420 transcripts) and which genes were preferentially expressed in either of the synapse types (508 transcripts in EOMsyn and 344 in TAsyn). To increase the stringency of the analysis we substracted the transcribed loci without gene affiliation and also subtracted transcripts that could be readily determined to emanate from the same genetic loci. We found 275 genes enriched in the EOM synaptic region that were not enriched in the TA synaptic region and 230 genes enriched in the TA synaptic region that were not enriched in the EOM synaptic region. An intersection of these enriched gene lists revealed 288 transcripts that were expressed in EOM and TA synapses. Table 1 shows the 25 most upregulated genes on this list, which contains such well-known, evolutionarily conserved, synaptic markers as Chrna and Chrne, Nes, and dual specificity phosphatase 6 (Dusp6).27 We also show the 15 most upregulated genes that were preferentially expressed in EOMsyn (Table 2) and TAsyn (Table 3). We sorted the enriched genes in EOMsyn (n = 275) and TAsyn (n = 230) and the genes that were upregulated in EOMsyn and TAsyn (n = 288) into various functional groups (for their GO terms for biological processes) by searching each gene in NetAffix and DAVID (Fig. 4B). Channel and transport proteins represented 9.4% of all known genes in the intersection, 11.3% of all genes with preferential EOM synaptic expression and 12.2% of the genes with preferential TA synaptic expression. Signaling molecules represented 13.5% of the intersection, 9.8% of EOMsyn and 14.3% of TAsyn genes. Adhesion molecules represented 7.3% of the intersection, 4.0% of EOMsyn and 4.3% of TAsyn genes. Other groups included several genes involved in transcription and regulation of growth (Fig. 4B). Overall, we found the genes of these lists involved in the same biological processes, which confirms the fundamental similarity between the EOM and TA synapses. On the other hand, numerous differentially expressed genes identify and define the unique gene expression patterns at EOM and TA synapses.

Figure 4.

Venn diagram of intersection and GO annotations of expression profiling datasets. Venn diagram (A) shows the intersection of transcripts that were detected at greater than a twofold cutoff for the datasets EOMsyn versus EOMfib (set 1) and TAsyn versus TAfib (set 2). Data were sorted for genes that both profiles had in common (intersection; 420 transcripts) and genes that were found in either EOMsyn (508 transcripts) or TAsyn (344 transcripts). After the unknown transcripts had been substracted, the known genes of the intersection (288 genes), EOMsyn (275 genes), and TAsyn (230 genes) were also sorted for their involvement in biological processes by their GO annotations and are shown in (B).

Table 1.

Twenty-five Most Upregulated Genes in EOMsyn versus EOMfib and TAsyn versus TAfib

| Column ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Gene Ontology Biological Process | EOMsyn vs. EOMfib Change Ratio | TAsyn vs. TAfib Change Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1369137_at | Chrne | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, epsilon polypeptide | Transport // inferred from electronic annotation // ion transport | 157.247 | 117.543 |

| 1371293_at | LOC688228 | Similar to Myosin light polypeptide 4 | — | 126.452 | 350.942 |

| 1383447_at | Etv5 | Ets variant gene 5 | Organ morphogenesis // positive regulation of transcription | 97.3142 | 164.044 |

| 1382319_at | Gpr68_pred. | G protein-coupled receptor 68 (predicted) | — | 85.2915 | 19.2249 |

| 1386905_at | Prkar1a | Protein kinase, cAMP dependent regulatory, type I, alpha | Regulation of protein amino acid phosphorylation//signal transduction | 67.846 | 164.315 |

| 1370432_at | Pou3f1 | POU domain, class 3, transcription factor 1 | Transcription // regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 65.1349 | 18.8814 |

| 1380138_at | RGD1564397_pred. | Similar to heparan sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2 isoform S | — | 51.2881 | 29.8474 |

| 1378144_at | BC060737_pred. | CDNA BC060737 (predicted) | — | 50.8532 | 16.8249 |

| 1387024_at | Dusp6 | Dual specificity phosphatase 6 | Inactivation of MAPK activity // protein amino acid dephosphorylation | 39.8326 | 99.6652 |

| 1373911_at | Postn_pred. | Periostin, osteoblast specific factor (predicted) | Cell adhesion // extracellular matrix organization and biogenesis | 35.9518 | 184.012 |

| 1393069_at | Sfrp5_pred. | Secreted frizzled-related sequence protein 5 (predicted) | — | 34.6946 | 5.18785 |

| 1367760_at | Map2k1 | Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 1 | MAPKKK cascade // protein amino acid phosphorylation | 31.8626 | 28.9762 |

| 1371052_at | Nog | Noggin | Inferred from electronic annotation // central nervous system develop. | 29.8093 | 52.838 |

| 1386948_at | Nes | Nestin | Nervous system development | 27.7714 | 79.7923 |

| 1387112_at | Plp1 | Proteolipid protein (myelin) 1 | Integrin-mediated signaling pathway | 24.8193 | 17.8458 |

| 1369843_at | Chrna1 | Cholinergic receptor, nicotinic, alpha polypeptide 1 (muscle) | Transport // ion transport// neuromuscular synaptic transmission | 23.8895 | 300.776 |

| 1381374_at | Lgi4 | Leucine-rich repeat LGI family, member 4 | Neuron maturation | 23.0476 | 5.40245 |

| 1386903_at | S100b | S100 protein, beta polypeptide, neural | Learning and/or memory // regulation of neuronal synaptic plasticity | 21.3054 | 8.66384 |

| 1387146_a_at | Ednrb | Endothelin receptor type B | G protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway | 21.0869 | 6.59027 |

| 1373590_at | Stom | Stomatin | Carbohydrate metabolic process // inferred from electronic annotation | 21.0434 | 17.4717 |

| 1391534_at | Elovl2_pred. | Elongation of very long chain fatty acids | — | 20.844 | 4.14474 |

| 1381995_at | Brunol4_pred. | Bruno-like 4, RNA binding protein (Drosophila) (predicted) | mRNA splice site selection | 19.4164 | 7.16528 |

| 1368427_at | — | Transcribed locus | — | 18.9114 | 11.7946 |

| 1368475_at | Colq | Collagen-like tail subunit (single strand of homotrimer) | Phosphate transport // neurotransmitter catabolic process | 18.5443 | 13.2888 |

| 1387803_at | Ppp2r2b | Protein phosphatase 2, reg. subunit B (PR 52), beta isoform | Signal transduction // inferred from electronic annotation | 18.1864 | 3.89215 |

Table 2.

Fifteen Most Upregulated Genes in EOMsyn versus EOMfib

| Column ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Gene Ontology Biological Process | EOMsyn vs. EOMfib Change Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1383435_at | Scn3b | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type III, beta | Transport//ion transport | 23.4972 |

| 1376225_at | — | Transcribed locus, strongly similar to Calsenilin | — | 22.19 |

| 1383444_at | Slc24a2 | Solute carrier family 24, member 2 | Transport//ion transport | 21.5818 |

| 1368540_at | Tpbg | Trophoblast glycoprotein | — | 19.8022 |

| 1373793_at | Igsf8 | Immunoglobulin superfamily, member 8 | — | 16.4911 |

| 1385038_at | Hhip | Hedgehog-interacting protein | Signal transduction//smoothened signaling pathway | 16.0351 |

| 1369347_s_at | Prom2 | Prominin 2 | — | 12.7502 |

| 1398405_at | Sept6 | Septin 6 | — | 11.681 |

| 1383946_at | Cldn1 | Claudin 1 | Calcium-independent cell-cell adhesion | 8.87824 |

| 1384864_at | Dhh | Desert hedgehog | Smoothened signaling pathway // cell-cell signal. | 8.62125 |

| 1392646_at | Tmem16d | Transmembrane protein 16D | — | 8.52559 |

| 1368090_at | Prx | Periaxin | Axon ensheathment | 8.50384 |

| 1370389_at | Gpm6b | Glycoprotein m6b | — | 7.8063 |

| 1379505_at | Lix1_predicted | Limb expression 1 homolog (chicken) (predicted) | — | 7.69383 |

| 1388004_at | Gpr37l1 | G protein-coupled receptor 37-like 1 | G protein-coupled receptor protein signaling pathway | 7.29707 |

Table 3.

Fifteen Most Upregulated Genes in TAsyn versus TAfib

| Column ID | Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Gene Ontology Biological Process | TAsyn vs. TAfib Change Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1375026_at | LOC691455 | Similar to calmodulin-like 4 | — | 156.718 |

| 1370517_at | Nptx1 | Neuronal pentraxin 1 | — | 118.519 |

| 1398358_a_at | Itgb5 | Integrin, beta 5 | — | 39.2099 |

| 1390358_at | Cacna2d3 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, alpha2/delta subunit 3 | Transport // inferred from electronic annotation // ion transport | 37.4849 |

| 1373490_at | Gmfg | Glia maturation factor, gamma | — | 35.7943 |

| 1391187_at | Ppl_predicted | Periplakin (predicted) | — | 31.6507 |

| 1387323_at | Klkb1 | Kallikrein B, plasma 1 | Proteolysis // inferred from electronic annotation | 29.3106 |

| 1371947_at | Ndn | Necdin | Nerve growth factor receptor signaling pathway | 20.9155 |

| 1393460_at | Lrrc33 | Leucine rich repeat containing 33 | — | 16.7067 |

| 1388271_at | Mt2A | Metallothionein 2A | Nitric oxide mediated signal transduction | 16.3911 |

| 1371684_at | Pelo | Pelota homolog (Drosophila) | Translation // inferred from electronic annotation | 15.7686 |

| 1370932_at | Lrp4 | Low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 | Negative regulation of Wnt receptor signaling pathway // receptor clustering | 15.0417 |

| 1369662_at | Scn2a1 | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type II, alpha 1 | Transport // ion transport | 13.677 |

| 1388138_at | Thbs4 | Thrombospondin 4 | Cell adhesion // nervous system development | 13.2976 |

| 1386974_at | Phldb1 | Pleckstrin homology-like domain, family B, member 1 | — | 13.2754 |

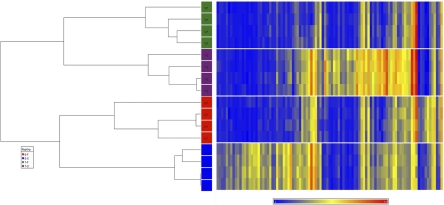

Furthermore, we generated an interaction list as a more stringent approach to determining the most significantly differentially expressed genes across the four different tissue types. After filtering with an FDR of 0.01, we received a list of 99 transcripts (set 5), representing 0.31% of the total of probe sets that were screened (n = 31,099). We have visualized these statistically significant transcripts on a heatmap (Fig. 5) to show the relative expression of each transcript.

Figure 5.

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering and heatmap of differentially expressed transcripts in EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, and TAfib. The diagram shows unsupervised hierarchical clustering (left) and heatmap (right) of 99 genes that were differentially expressed between the four groups EOMsyn (blue), EOMfib (red), TAsyn (purple), and TAfib (green) at an FDR of 0.01. The normalized raw data of the 20,266 detected transcripts were used to perform unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Based on the correlation of gene expression patterns, the EOMsyn, EOMfib, TAsyn, and TAfib microarray data cluster into four distinct groups, as can be seen in the dendrogram, which quantitatively demonstrates that the EOMsyn samples are related to one another, as are the EOMfib, TAsyn, and TAfib samples. The scale for the heatmap is shown below with blue representing the lowest expression and red the highest level.

Validation

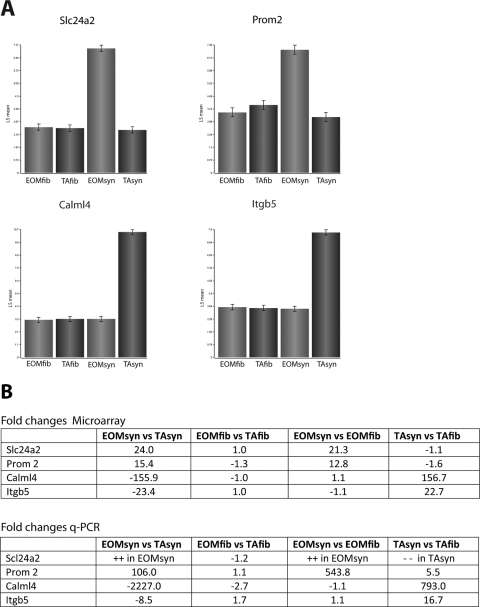

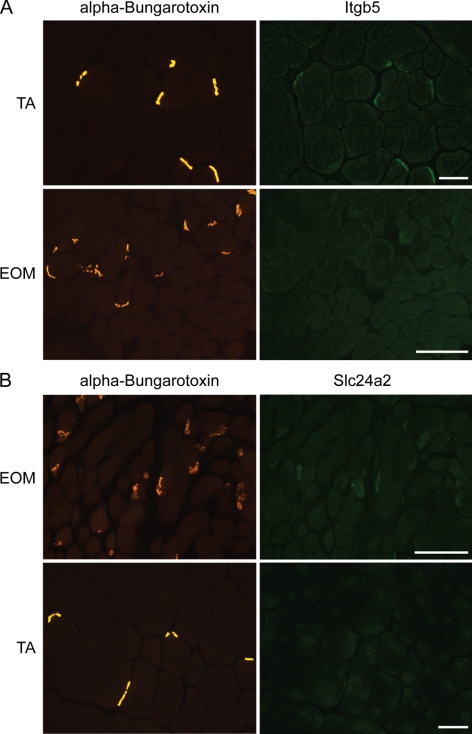

The microarray data were validated with qPCR. For validation of sets 1 to 4, we verified the expression levels of 13 genes by qPCR (Chrne, Nes, Csen, Myh13, Myh8, Ndrg4, Smyd2, Myom2, Hox10a, Rcan2, Ca3, Gmfg, and Aqp4; Supplementary Tables S6–S9, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/full/51/9/4589/DC1). Genes validated included upregulated as well as downregulated genes of each of the four comparisons; well-known synaptic markers such as Chrne and Nes served as positive controls (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7). The interaction list was validated for four genes, two of which were preferentially expressed in EOM synapses (Slc24a2 and Prom2) and two in TA synapses (Calm-l4 and Itgb5) (Fig. 6A). Change ratios of microarray and qPCR data were concordant and correlated well, validating our profile (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, relative protein levels of Itgb5 and Slc24a2 assessed by immunohistochemistry showed that TA synapses stained strongly for Itgb5, whereas it was not detected in EOM synapses (Fig. 7A). Slc24a2 showed weak but preferential staining in EOM synapses (Fig. 7B).

Figure 6.

Validation of differentially expressed genes by real-time qPCR. Selected genes with preferential expression in EOMsyn or TAsyn were verified by qPCR. (A) Normalized expression levels of the microarray for the four genes (Slc24a2 and Prom2 for EOMsyn and Calml4 and Itgb5 for TAsyn) that were chosen for validation. Changes of gene expression in the microarray and qPCR correlated well and are shown in the tables (B). ++, high levels; –, no amplification.

Figure 7.

Validation of Itgb5 and Slc24a2 expression by immunohistochemistry. Itgb5 and Slc24a2 expression in NMJs was verified by double staining with specific antibodies (right) and α-bungarotoxin to mark synapses (left). (A) TAsyn were positive for Itgb5, whereas EOMsyn were negative. (B) EOMsyn were weakly labeled with anti-Slc24a2, whereas TAsyn were negative for Slc24a2. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

The molecular makeup of EOMs is inherently different from limb muscle. To test our hypothesis that these differences extend to the genes expressed at the synapses by subsynaptic nuclei, we compared the expression of those genes by using gene microarrays (GeneChips; Affymetrix). We found 275 known genes enriched in EOM synapses and 230 known genes enriched in TA synapses. To identify genes that were most significantly specific for each tissue type, we created an interaction list consisting of 99 genes. Verification of tissue specific genes was undertaken by qPCR with biologically independent samples. Our results support our hypothesis that fundamental differences in the overall patterns of gene expression exist between the NMJ regions of EOM compared with the NMJ regions of other skeletal muscles.

Several recent studies27–31,36 have suggested that a large pool of genes involved in NMJ functioning is yet to be discovered. Our results are consistent with these suggestions, because they revealed numerous genes that had not been known to play a role in the NMJs. Although the NMJ is one of the most thoroughly studied synapses and many important players involved in its assembly, maintenance, and stabilization have been identified, we are still far from having a complete understanding of this subcellular region.

Beside the AChR subunits we found synaptic genes such as the well-conserved Nes and Prka1a, in accordance with previous studies.29,30 Our profiles also revealed previously described Dusp6 and sodium channels (Scn3b in EOMsyn and Scn2a1 in TAsyn) which are important functional components of the NMJ.27,37 Supplementary Figure S2, http://www.iovs.org/cgi/content/full/51/9/4589/DC1, provides a comparison of the TA-NMJ transcriptome with that described by Nazarian et al.27 The use of LCM as a technique to isolate synaptic regions from nonsynaptic regions has certain limitations. LCM did not allow us to eliminate the mRNAs present in perisynaptic Schwann cells from the synapse pool. This limitation became apparent by the presence of the Schwann cell marker S100 in the synapse pool (Table 1). We did not distinguish between individual layers of EOM and could not unambiguously distinguish MIFs and SIFs in EOM on the basis of AchE staining alone. However, because of the larger size, abundance (most are SIFs), and location, it is likely that we preferentially collected SIF-associated NMJs rather than those associated with MIFs. This probability offers an explanation of our failure to detect mRNA for the gamma subunit of AChR at EOM synapses, as it is known to be associated with MIFs rather than SIFs.32

Signaling, Transduction, and Transcription

The major signaling pathways important for the molecular organization of the NMJ include the neuregulin/v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homologue (ErbB) and Agrin/skeletal muscle tyrosine kinase (Musk) pathways.38 It has been shown by immunolabeling with antibodies against Agrin, receptor-associated protein of synapse (Rapsyn), musk, neuregulin, and ErbB receptors that major components of these pathways are conserved in EOMs.33 However, these investigators reported that in contrast to limb muscle, EOM expressed α-dystrobrevin 1 and β-syntrophin1 in extrajunctional regions. Although the exact functional significance of this finding is unclear, it provides evidence at the protein level of some divergence of molecules expressed in the synaptic and extrasynaptic regions of EOM versus limb muscles. Several genes encoding proteins involved in these pathways were found in our profiles, including Agrin, ErB receptor B3, and some downstream molecules of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (Mapk) and ErbB signaling pathways (e.g., Ras, Map2k1, ets variant gene 5 [Etv5]). Our data support the view of Khanna et al.33 that signal transduction pathways that are used in EOMs are similar to those in other muscles, although the variable expression of signaling molecules may suggest an unequal preference for pathways. Moreover, different modulation especially through extracellular matrix molecules of these pathways may occur.39 Several of these molecules showed preferential expression in our profiles, most significant was integrin beta 5 (Itgb5), which was preferentially expressed in TAsyn compared with EOMsyn and was independently validated by q-PCR. Integrins appear to serve as agrin-binding accessory proteins that mediate the effects of agrin via their laminin G-like domains leading to AChR aggregation.40 Supporting the role of integrins at NMJs McGeachie et al.30 found integrin beta 1 preferentially expressed in NMJs.

Membrane Adhesion

A striking difference in the postsynaptic organization of EOM is the sparseness of subjunctional folds when compared with skeletal muscle. This anatomic feature varies from complete absence in MIFs (orbital and global) to a variable, but in general modest, presence in SIFs.33 Immunohistochemistry suggests that there may be a divergence in the molecular specialization of the extrasynaptic dystrophin glycoprotein complex in EOM.33 We found a glycoprotein, Prom2, preferentially expressed in EOM synapses which is suggested to be involved in the organization of membranes and membrane protrusions in epithelial cells.41,42 Our profile also revealed several genes involved in cell adhesion that were preferentially expressed in TAsyn or EOMsyn and we therefore suggest that the differential expression of these molecules may contribute to the special postjunctional morphology in EOMsyn.

Channels and Transport

Among the genes specifically confined to one synapse versus another was a group of channels and transport proteins. One gene, Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchanger member 2 (Slc24a2), showed significantly higher expression in EOM synapses than in TA synapses. The Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers are a family of bidirectional plasma membrane transporters that play a prominent role in maintaining intracellular calcium homeostasis. Slc24a2 transcripts have been reported in brain and retina,43–46 and it was recently suggested that they also play an important role in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in synaptic nerve terminals.47,48 The Slc24 channels seem to play a dominant role in calcium clearance, especially at high intracellular calcium levels that occur after a train of action potentials.47 Although the channel has not been reported to be present in the NMJ, our profile reveals a 24-fold upregulation in EOMsyn that may contribute to the ability of EOMs to sustain high twitch frequencies.

In conclusion, our results show that the main molecular components of the NMJs are conserved in the EOM synapses; however, the large number of genes that are differentially expressed in these synapses strongly underscores the uniqueness of this NMJ as a part of the EOM allotype. Although the exact functional significance of differences of gene expression at synapses and extrasynaptic regions of EOMs and limb muscle is unclear, it is very likely necessary in fine tuning neuromuscular transmission to meet the specialized functional demands of EOMs and limb muscles. Our expression profiling data provide a broad overview, and we are aware that linking the molecular findings in our microarray to specific EOM fiber types/synapses still has to be accomplished. Nevertheless, our identification and definition of the overall EOM synaptic transcriptome paves the way for future studies and provide insight into the mechanism of formation and functioning of the unique synapses of EOM and their differential involvement in diseases noted in the EOM allotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Javad Nazarian and Eric Hoffman (Children's National Medical Center, Washington, DC) for guidance and protocols.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants EY011779 (NAR) and EY013862 (TSK) from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure: C. Ketterer, None; U. Zeiger, None; M.T. Budak, None; N.A. Rubinstein, None; T.S. Khurana, None

References

- 1.Porter JD, Baker RS, Ragusa RJ, Brueckner JK. Extraocular muscles: basic and clinical aspects of structure and function. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:451–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bron AJ, Tripathi RC, Tripathic BJ. Wolff's Anatomy of the Eye and the Orbit. London: Chapman and Hall Medical; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoh JFY, Hughes S. Myogenic and neurogenic regulation of myosin gene expression in cat jaw-closing muscles regenerating in fast and slow limb muscle beds. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988;9:57–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer MD, Budak MT, Bakay M, et al. Definition of the unique human extraocular muscle allotype by expression profiling. Physiol Genomics. 2005;22:283–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer MD, Gorospe JR, Felder E, et al. Expression profiling reveals metabolic and structural components of extraocular muscles. Physiol Genomics. 2002;9:71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna S, Merriam AP, Gong B, Leahy P, Porter JD. Comprehensive expression profiling by muscle tissue class and identification of the molecular niche of extraocular muscle. FASEB J. 2003;17:1370–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemann CU, Krag TOB, Khurana RS. Identification of genes that are differentially expressed in extraocular and limb muscle. J Neurol Sci. 2000;179:76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Porter JD, Khanna S, Kaminski HJ, et al. Extraocular muscle is defined by a fundamentally distinct gene expression profile. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:12062–12067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraterman S, Zeiger U, Khurana TS, Rubinstein NA, Wilm M. Combination of peptide OFFGEL fractionation and label-free quantitation facilitated proteomics profiling of extraocular muscle. Proteomics. 2007;7:3404–3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraterman S, Zeiger U, Khurana TS, Wilm M, Rubinstein NA. Quantitative proteomics profiling of sarcomere associated proteins in limb and extraocular muscle allotypes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:728–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminski HJ, al-Hakim M, Leigh RJ, Katirji MB, Ruff RL. Extraocular muscles are spared in advanced Duchenne dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 1992;32:586–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khurana TS, Prendergast RA, Alameddine HS, et al. Absence of extraocular muscle pathology in Duchenne's muscular dystrophy: role for calcium homeostasis in extraocular muscle sparing. J Exp Med. 1995;182:467–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brais B, Bouchard JP, Xie YG, et al. Short GCG expansions in the PABP2 gene cause oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1998;18:164–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinsson T, Darin N, Kyllerman M, Oldfors A, Hallberg B, Wahlstrom J. Dominant hereditary inclusion-body myopathy gene (IBM3) maps to chromosome region 17p13.1. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1420–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminski HJ, Maas E, Spiegel P, Ruff RL. Why are eye muscles frequently involved in myasthenia gravis? Neurology. 1990;40:1663–1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaminski HJ. Acetylcholine receptor epitopes in ocular myasthenia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;841:309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elrod RD, Weinberg DA. Ocular myasthenia gravis. Ophthalmology Clin N Am. 2004;17:275–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes BW, Casillas MLM, Kaminski HJ. Pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis. Semin in Neurol. 2004;24:21–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaminski HJ, Li Z, Richmonds CR, Ruff RL, Kusner L. Susceptibility of ocular tissues to autoimmune diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;998:362–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson DA. Oculomotor unit behavior in the monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1970;33:393–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hennig R, Lomo T. Firing patterns of motor units in normal rats. Nature. 1985;314:164–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter JD, Hauser KF. Survival of extraocular muscle in long-term organotypic culture: differential influence of appropriate and inappropriate motoneurons. Dev Biol. 1993;160:39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engle EC, Goumnerov BC, McKeown CA, et al. Oculomotor nerve and muscle abnormalities in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:314–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:791–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duclert A, Changeux JP. Acetylcholine receptor gene expression at the developing neuromuscular junction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:339–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gramolini AO, Dennis CL, Tinsley JM, et al. Local transcriptional control of utrophin expression at the neuromuscular synapse. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8117–8120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nazarian J, Bouri K, Hoffman EP. Intracellular expression profiling by laser capture microdissection: three novel components of the neuromuscular junction. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21:70–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jevsek M, Jaworski A, Polo-Parada L, et al. CD24 is expressed by myofiber synaptic nuclei and regulates synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:6374–6379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishi M, Kummer TT, Eglen SJ, Sanes JR. LL5beta: a regulator of postsynaptic differentiation identified in a screen for synaptically enriched transcripts at the neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:355–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGeachie AB, Koishi K, Andrews ZB, McLennan IS. Analysis of mRNAs that are enriched in the post-synaptic domain of the neuromuscular junction. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30:173–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieburth D, Ch'ng Q, Dybbs M, et al. Systematic analysis of genes required for synapse structure and function. Nature. 2005;436:510–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraterman S, Khurana TS, Rubinstein NA. Identification of acetylcholine receptor subunits differentially expressed in singly and multiply innervated fibers of extraocular muscles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3828–3834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khanna S, Richmonds CR, Kaminski HJ, Porter JD. Molecular organization of the extraocular muscle neuromuscular junction: partial conservation of and divergence from the skeletal muscle prototype. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1918–1926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spencer RF, Porter JD. Structural organization of the extraocular muscles. Rev Oculomot Res. 1988;2:33–79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karnowsky MJ, Roots LA. A “direct coloring” thiocholine method for cholinesterase. J Histochem Cytochem. 1964;3:219–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nazarian J, Hathout Y, Vertes A, Hoffman EP. The proteome survey of an electricity-generating organ (Torpedo californica electric organ). Proteomics. 2007;7:617–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beam KG, Caldwell JH, Campbell DT. Na channels in skeletal muscle concentrated near the neuromuscular junction. Nature. 1985;313:588–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schaeffer L, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Changeux JP. Targeting transcription to the neuromuscular synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dityatev A, Schachner M. The extracellular matrix and synapses. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:647–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier T, Wallace BG. Formation of the neuromuscular junction: molecules and mechanisms. Bioessays. 1998;20:819–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fargeas CA, Florek M, Huttner WB, Corbeil D. Characterization of prominin-2, a new member of the prominin family of pentaspan membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8586–8596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Florek M, Bauer N, Janich P, et al. Prominin-2 is a cholesterol-binding protein associated with apical and basolateral plasmalemmal protrusions in polarized epithelial cells and released into urine. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;328:31–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prinsen CF, Szerencsei RT, Schnetkamp PP. Molecular cloning and functional expression of the potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger from human and chicken retinal cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1424–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prinsen CF, Cooper CB, Szerencsei RT, Murthy SK, Demetrick DJ, Schnetkamp PP. The retinal rod and cone Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;514:237–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsoi M, Rhee KH, Bungard D, et al. Molecular cloning of a novel potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4155–4162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paillart C, Winkfein RJ, Schnetkamp PP, Korenbrot JI. Functional characterization and molecular cloning of the K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in intact retinal cone photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 2007;129:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SH, Kim MH, Park KH, Earm YE, Ho WK. K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchange is a major Ca2+ clearance mechanism in axon terminals of rat neurohypophysis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6891–6899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim MH, Lee SH, Park KH, Ho WK, Lee SH. Distribution of K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in the rat supraoptic magnocellular neuron is polarized to axon terminals. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11673–11680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.