Abstract

IL-18 and the extracellular matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inducer (EMMPRIN) stimulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs and are elevated in myocardial hypertrophy, remodeling, and failure. Here, we report several novel findings in primary cardiomyocytes treated with IL-18. First, IL-18 activated multiple transcription factors, including NF-κB (p50 and p65), activator protein (AP)-1 (cFos, cJun, and JunD), GATA, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein, myocyte-specific enhancer-binding factor, interferon regulatory factor-1, p53, and specific protein (Sp)-1. Second, IL-18 induced EMMPRIN expression via myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88/IL-1 receptor-associated kinase/TNF receptor-associated factor-6/JNK-dependent Sp1 activation. Third, IL-18 induced a number of MMP genes, particularly MMP-9, at a rapid rate as well as tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1 and TIMP-3 at a slower rate. Finally, the IL-18 induction of MMP-9 was mediated in part via EMMPRIN and through JNK- and ERK-dependent AP-1 activation and p38 MAPK-dependent NF-κB activation. These results suggest that the elevated expression of IL-18 during myocardial injury and inflammation may favor EMMPRIN and MMP induction and extracellular matrix degradation. Therefore, targeting IL-18 or its signaling pathways may be of potential therapeutic benefit in adverse remodeling.

Keywords: myocardial remodeling, extracellular matrix, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, matrix metalloproteinase, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase, c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase, specific protein-1, activator protein-1, nuclear factor-κB

interleukin (IL)-18, a pleiotropic cytokine belonging to the IL-1 family, is synthesized as a nonglycosylated inactive precursor and converted to an active form by caspase-1 (13). Released mature IL-18 exerts its effects through the IL-18 receptor (IL-18R), a heterodimer of α- and β-subunits (4, 36). Binding to IL-18R-α fails to transmit intracellular signals but leads to heterodimerization with IL18R-β and the activation of diverse signaling pathways. IL-18-binding protein (IL-18BP), a naturally occurring, constitutively secreted inhibitor of IL-18, binds IL-18 with high affinity and blocks its activity (24). Patients with end-stage heart failure have increased levels of IL-18 and IL-18R-α, suggesting a positive amplification of IL-18 signaling (26, 30, 44, 46). Furthermore, IL-18BP levels are significantly decreased (26), suggesting a failure in the negative feed mechanisms that attenuate IL-18 signaling, thus possibly contributing to the progression of heart failure.

Expression of IL-18 is also upregulated during various immune, infectious, and inflammatory conditions. It serves to amplify the inflammatory cascade by inducing the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules (13, 46). Elevated plasma IL-18 levels have been detected in patients with acute coronary syndromes, and a direct correlation has been observed between IL-18 levels and the severity of myocardial dysfunction (25). Circulating IL-18 levels have been shown independently predict coronary events in humans (32), and increased basal levels of IL-18 have been detected in people who later developed coronary events. Increased circulating IL-18 levels have also been detected in stroke patients (54). IL-18 has also been detected in the murine myocardium during endotoxemia, and the administration of IL-18-neutralizing antibodies, IL-18BP, or inhibition of caspase-1 activity have been reported to attenuate tissue and circulating levels of IL-18 and improve LPS-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction (29), suggesting that IL-18 is a myocardial depressant. In fact, Woldbaek et al. (48) have demonstrated increased cardiac IL-18 mRNA, pro-IL-18, and plasma IL-18 levels 7 days after myocardial infarction and reported depressed cardiac contractility after the acute as well as chronic administration of IL-18. Recently, we and others (12, 38, 47) have reported that IL-18 plays a causal role in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, pressure-overload hypertrophy, and myocardial infarction, probably due to its differential effects on various myocardial constituent cells. While exerting prosurvival and progrowth effects in cardiomyocytes (6), IL-18 induces cardiac endothelial cell death (9, 53). Since its administration induces cardiac fibrosis (51), it appears that its differential effects on myocardial constituent cells may contribute to adverse myocardial remodeling.

Myocardial remodeling, a physiological process necessary for the normal growth of the heart, is characterized by a balance between the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors [tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs)] (34, 45). After myocardial injury, infection, and inflammation, this balance is disrupted and results in sustained MMP expression, enhanced extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, cardiomyocyte death and hypertrophy, fibrosis, adverse remodeling, dilation, and myocardial failure. MMPs degrade various ECM proteins, including collagens, gelatins, fibronectin, and laminins. We (7) have previously demonstrated that IL-18 induces the expression of MMP-2 (gelatinase A) and MMP-9 (gelatinase B) in aortic smooth muscle cells (SMCs). In those cells, it increased their migration via increased transcription and translation of MMP-9 (7). Since IL-18 levels are increased in heart failure (26, 30, 44, 46), and as heart failure is characterized by enhanced MMP-9 expression and activity (37) and as lack of MMP-9 expression has been reported to attenuate left ventricular (LV) remodeling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction (15) and acute pressure overload (17), we hypothesized that IL-18 induces MMP-9 expression in cardiomyocytes and investigated the underlying signal transduction pathways.

The extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) is a cell membrane glycoprotein and has been shown to induce the expression of various MMPs, including MMP-9, and to be involved in both physiological and pathological remodeling (20, 55). Recently, we demonstrated that EMMPRIN induces various MMPs in cardiomyocytes. Interestingly, it also induced TIMP expression, but in a delayed fashion, suggesting that EMMPRIN overexpression favors MMP induction and ECM degradation. In the heart, it is expressed in cardiomyocytes but not in cardiac fibroblasts or endothelial cells (31), suggesting that cardiomyocyte-derived EMMPRIN may act on adjacent cardiomyocytes via transcellular homophilic EMMPRIN-EMMPRIN interactions and induce MMP-9 expression. Since EMMPRIN is cleaved from the cell surface (35), cardiomyocyte-derived soluble EMMPRIN may act distally on cardiac fibroblasts and endothelial cells via an interaction with integrin (2) or other yet-to-be-identified EMMPRIN receptors and induce MMP expression. In support of this hypothesis, ectopic expression of EMMPRIN or exogenous addition of recombinant EMMPRIN has been shown to induce the differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and stimulate MMP production (18), implying its role in fibrosis, adverse remodeling, and failure. Of note, its expression is increased in human heart failure (33), and its transgenic overexpression in a cardiac-specific manner results in myocardial hypertrophy and failure in aged mice (55). Importantly, EMMPRIN gene-deleted mice show various developmental defects such as sterility, blindness, and compromised sensory and memory functions due to weak expression of MMPs, failure to break down the ECM, lack of remodeling, cell migration, growth, differentiation, and maturation (21). Since both IL-18 and EMMPRIN are upregulated in myocardial hypertrophy and failure, and since both induce cytokine and MMP expression and play a role in adverse remodeling, we investigated 1) whether IL-18 induces EMMPRIN expression in cardiomyocytes, 2) whether IL-18 induces MMP and TIMP expression, and 3) whether IL-18-induced MMP expression is EMMPRIN dependent. We were also interested in determining the underlying molecular mechanisms.

METHODS

Materials.

Recombinant mouse IL-18 (B002-5), recombinant mouse IL-6 (406-ML-005/CF), IL-18-neutralizing antibodies (αIL-18 Ab; 10 μg/ml for 1 h), normal mouse IgG1 (MAB002), IL-18 antibodies used in the immunoblot analysis (D043-3), IL-18BP-Fc (119-BP-100; 10 μg/ml for 1 h), Fc, and anti-EMMPRIN antibodies used in the immunoblot analysis (AF772) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). EMMPRIN function blocking antibodies (UM-8D6, no. 373-020) were from Ancell (Bayport, MN), and their efficacy has been previously demonstrated (42). Antibodies against NF-κB (p65; no. 3034), ERK1/2 (no. 9102), phosphorylated (p-)ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; no. 9101), p38 MAPK (no. 9212), p-p38MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182; no. 9211), and lamin A/C (no. 2032) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Antibodies against JNK (sc-81468), p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185; sc-12882), cFos (sc-52), c-Jun (sc-44), myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88; sc-11356), IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 4 (IRAK4; sc-135668), and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6; sc-7221) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). SP-600125 (20 μM for 30 min), SB-203580 (1 μM for 30 min), and PD-98059 (10 μM for 1 h) as well as their diluent (DMSO) were purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). α-Tubulin polyclonal antibodies, mithramycin, doxorubicin, polymyxin B sulphate (10 μg/ml in water for 2 h), and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Adult and neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes.

This investigation conformed with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Revised 1996) and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Tulane University in New Orleans. Ca2+-tolerant adult mouse cardiomyocytes (ACMs) were isolated from 3-mo-old male C57Bl/6 mice (3 mo of age, Charles River Laboratories) as previously described (40). Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs) were isolated from 1- to 3-day-old neonatal mice (C57Bl/6 background) as previously described (38).

Adenoviral transduction.

Recombinant, replication-deficient adenoviral vectors encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP; Ad.GFP), dnp65 (Ad.dnp65), kdIKK-β (Ad.kdIKK-β), phosphorylation-deficient IκB-α (S32A/S36A, Ad.dnIκB-α), a truncated soluble mutant of EMMPRIN (Ad.mEMMPRIN), and its control (Ad.empty vector) have all been previously described (27, 38). Cells were infected with adenoviruses in PBS at ambient temperature and at the indicated multiplicities of infection (MOIs). After 1 h, the adenovirus was replaced with media containing 0.5% BSA. Assays were carried out 24 h later.

Small interfering RNA and transfections.

NMCMs were transiently transfected with the indicated vectors using the Neonatal Nucleofector kit (no. VPE-1002, Amaxa). After an overnight incubation in medium containing 0.5% BSA, dead cells were removed, and the incubation was continued for an additional 24 h. Small interfering (si)RNA against MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) before transfection with the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector. These siRNA consisted of pools of three to five target-specific 19- to 25-nt siRNAs designed to knock down target gene expression. A nontargeting scrambled siRNA duplex (Scramble II Duplex, Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) served as a control. In addition, siRNA against GFP served as a second control. Knockdown of target genes was confirmed by immunoblot analysis.

Promoter reporter activity.

A 537-bp fragment of the 5′-flanking region (−538 to −1 relative to the transcription start site) of the EMMPRIN gene (GenBank accession no. NT_039500) was amplified from mouse genomic DNA (no. G309A, Promega) using the primers shown in Table 1. The sense primers contained a KpnI restriction site at the 5′-end (lowercase letters in Table 1). The antisense primer contained a HindIII restriction site. The PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO and subcloned into the pGL3-Basic reporter vector at the same restriction sites. The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by sequencing of both strands. Mutations of Sp1-binding sites in the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector were performed by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and the primers shown in Table 1 and were confirmed by complete nucleotide sequencing. NMCMs were transfected with the indicated EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector (3 μg) and 100 ng of the control Renilla luciferase vector pRL-TK (Promega) using Lipofectamine. After incubation for the indicated time periods, cells were harvested for the dual-luciferase assay. Data were normalized by dividing firefly luciferase activity with that of the corresponding Renilla luciferase. For MMP-9 promoter analysis, a 726-bp fragment of the 5′-flanking region (−723 to −3 relative to the transcription start site) of the MMP-9 gene was subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (7).

Table 1.

Primers used in mouse EMMPRIN analysis

| Primers | |

|---|---|

| cDNA (GenBank accession no. NM_009768.2; 530-nt product size) | |

| Sense: 5′-CTGAGGTCCTGGTGTTGGTT-3′ | |

| Antisense: 5′-CCCCCTCCAACAGTAAGTCA-3′ | |

| Promoter construct | |

| Sense: 5′-ggtaccGGACAGCCGAGCATCGTGG-3′ | |

| Antisense: 5′-aagcttGTCGCCTCGTCCAGGAGCTG-3′ | |

| Site-directed mutagenesis | |

| Sp1-1 | Sense: 5′-TGTGTGCCTGGCGAGATCTACTGCGACGCCGCGT-3′ |

| Sp1-2 | Sense: 5′-TGCCTGCGTGCGCGCGAGATCTACTTCTTATAGAGC-3′ |

| Sp1 chromatin immunoprecipitation assay | |

| Sense: 5′-TGCCAACGCTTCTCCACCCGCT-3′ | |

| Antisense: 5′-TCCAGGAGCTGCCCCACT-3′ | |

| EMMPRIN open reading frame | |

| Sense: 5′-AGTCAACTCCAAAACACAGCTTA-3′ | |

| Antisense: 5′-CTCAGGAAGGAAGATGCAGGA-3′ |

EMMPRIN, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor; Sp1, specific protein-1.

mRNA quantitation.

Expression of EMMPRIN and MMP-9 mRNA was analyzed by reverse transcription followed by real-time quantitative PCR using an ABI Geneamp 7700 Sequence Detection System (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA-free total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion). RNA quality was assessed by capillary electrophoresis using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). All RNA samples had RNA integrity numbers of >9.1 (scale of 1–10), as assigned by default parameters of the Expert 2100 Bioanalyzer software package (version 2.02). Primer pairs were designed to span intron-exon junctions, and thermal melting profiles of amplicons were performed for confirmation. The primers for EMMPRIN (GenBank accession no. D00611, 102bp) were as follows: sense 5′-GGGAAACCATCTCACTGCGT-3′, antisense 5′-TAGATAAAGATGATGGTAACCAACACCA-3′, and probe 5′-FAM-CCTTCC TAGGCATCGTGGCTGAGGT-TAMRA-3′. The primers for MMP-9 were as follows: sense 5′-ACCCGAAGCGGACATTGTC-3′, antisense 5′-CGAAGGGATACCCGTCTCC-3′, and probe 5′-FAM-TCCAGTTTGGTGTCGCGG-TAMRA-3′. Amplification of actin (sense 5′-TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA-3′, antisense 5′-GGATGCCACAGGATTCCATACCCA-3′, and probe 5′-FAM-TATGCTCTCCCTCACGCCATCCTGCGT-TAMRA-3′) was performed for each sample to control for sample loading. No template controls were performed for each assay, and samples processed without the reverse transcriptase step served as negative controls. Each cDNA sample was run in triplicate, and the amplification efficiencies of all primer pairs were determined by serial dilutions of input template. The comparative cycle threshold method was used to analyze the data by generating relative values of the amount of target cDNA. All data were normalized to corresponding actin mRNA and are expressed as the fold difference in gene expression in IL-18-treated cardiomyocytes relative to untreated controls.

EMMPRIN mRNA expression was confirmed by Northern blot analysis using 25 μg of total RNA and a cDNA probe prepared by RT-PCR of total ACM RNA using the following primer pairs: sense 5′-CTGAGGTCCTGGTGTTGGTT-3′ and antisense, 5′-CCCCCTCCAACAGTAAGTCA-3′. Both 28S rRNA and actin served as loading controls.

MMP and TIMP expression at 1 and 24 h in IL-18-treated ACMs after EMMPRIN knockdown was analyzed as previously described (41) using a quantitative PCR-based array (PAMM-013, SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD). The array detects 13 MMPs {MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-10, MMP-11, MMP-12, MMP-13, MMP-14 [membrane type (MT)1-MMP], MMP-15 (MT2-MMP), and MMP-16 (MT3-MMP)} and 3 TIMPs (TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3). Actin served as an invariant control.

Protein-DNA interaction array.

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the Panomics Nuclear Extraction kit (no. AY2002, Panomics/Affymetrix, Freemont, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Protein-DNA interactions were analyzed using TranSignal Protein/DNA Array 1 (PD array 1, Panomics/Affymetrix) essentially as described by Imam et al. (22). The array detects 56 transcription factor elements simultaneously (see Supplemental Fig. 2).1

Regulation of IL-18-mediated transcription factor activation was confirmed by a signaling profiling ELISA (BD Mercury TransFactor Profiling Assay, BD Biosciences Clontech) (16). This assay profiles NF-κB (p65 and p50), c-Fos, cAMP responsive element-binding protein 1, activated transcription factor 2, c-Rel, FosB, c-Jun, JunD, Sp1, and STAT1. The assay has a 10-fold higher sensitivity than traditional EMSA with fewer false negative results (sensitivity for NF-κB of >0.3 nM) (1). Cardiomyocytes were treated with IL-18 for 2 h, and 25 μg of nuclear protein were used. After the addition of chromogen, plates were read at 650 nm.

The formation of NF-κB protein-DNA complexes and their subunit composition were also analyzed by ELISA (TransAM TF ELISA kits, catalog no. 43296; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) (30, 39). Activation of NF-κB was also confirmed by reporter assays using adenoviral transduction of an NF-κB reporter vector (Ad.NF-κB-Luc, MOI 50) (38). Similarly, activation of AP-1 was confirmed by a reporter assay using Ad-AP-1-Luc (50 MOI, Vector Biolabs). Ad-MCS-Luc served as a control. Ad-β-galactosidase (50 MOI, Vector Biolabs) served as an internal control. NF-κB activation was also confirmed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies against NF-κB p65. Activation of Sp1 was confirmed by ELISA (TransAM Sp1, Active Motif).

Binding of Sp1 to the EMMPRIN 5′-cis regulatory region in vivo was determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. ACMs were treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h), and the ChIP assay carried out as previously described (7, 39). Immunocomplexes were prepared using anti-Sp1 antibody (sc-14027 X, Santa Cruz Biotechnology,). Normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027) served as a control. The supernatant of an immunoprecipitation reaction carried out in the absence of antibody was used as the total input DNA control. PCR was carried out on 1 μl of a 1:100 dilution of each sample using EMMPRIN promoter-specific primers (Table 1). Primers predicted to amplify a similar size fragment from the EMMPRIN open reading frame (Table 1) served as a PCR control.

Protein analysis.

Protein levels in whole cell lysates and culture supernatants were analyzed by immunoblot analysis. In experiments quantifying secreted EMMPRIN levels in culture supernatants, tubulin in corresponding ACMs served as a loading control. IL-18-induced IκB kinase-β activity was analyzed at 1 h by an in vitro kinase assay using glutathione-S-transferase-IκB-α as the substrate (38).

Gelatin zymography.

MMP-9 proenzyme and enzyme levels were analyzed by SDS-PAGE zymography using culture supernatants (7).

Cell death analysis.

To investigate whether IL-18 induces cardiomyocyte death, ACMs were incubated with IL-18 for 24 h. Doxorubicin (1 μM for 24 h) served as a positive control (40). Cell death was analyzed using Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS. The assay uses mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against DNA and histones. This allows the specific detection and quantitation of mono- and oligonucleosomes released into the cytoplasm of cells that die from apoptosis (40). In addition, cell death was also analyzed by DNA fragmentation (Supplemental Fig. S1A). In brief, ACMs were harvested, washed, and incubated in 100 μl of 50 mM Tris·HCI (pH 8.0), 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, and 0.5 μg/ml proteinase K for 3 h at 50°C. Fifty microliters of 0.5 mg/ml RNase A were then added, and the incubation was continued for an additional 1 h. Digested samples were incubated with 100 μl of 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) containing 2% (wt/vol) low-melting point agarose, 0.25% bromophenol blue, and 40% sucrose at 70°C. DNA was separated in gels containing 2% agarose and Tris-acetate-EDTA (40 mM Tris-acetate and 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) buffer and visualized by ultraviolet illumination after being stained with ethidium bromide. In addition, cell viability was also tested by trypan blue dye exclusion and microscopic visualization of cell shape and for cells floating in the media.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons between controls and various treatments were performed by ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett's t-tests. All assays were performed at least three times, and the error bars in the figures indicate SEs. Although a representative immunoblot is shown in the figures, changes in protein/phosphorylation levels from three independent experiments were semiquantified densitometrically and are included in the corresponding Supplemental Material (Supplemental figures) along with statistical analyses.

RESULTS

IL-18 induces EMMPRIN expression in ACMs.

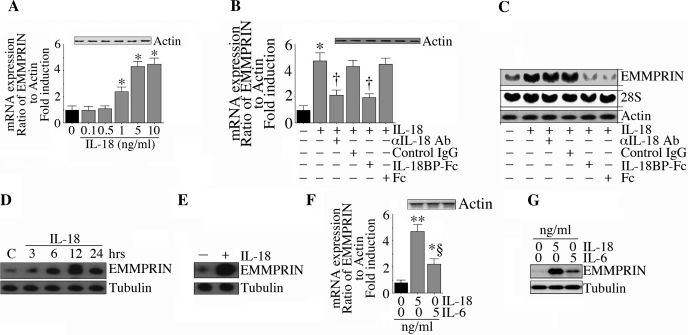

IL-18 and EMMPRIN induce proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs in various tissues and are elevated during myocardial hypertrophy, remodeling, and failure (26, 30, 33, 44, 46, 55). To investigate if IL-18 can regulate EMMPRIN expression in cardiac cells, ACMs were first treated for 2 h with recombinant IL-18 and then assayed for EMMPRIN mRNA by quantitative RT-PCR. IL-18 potently induced EMMPRIN mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner, with peak levels being detected at 5 ng/ml (Fig. 1A). No signal was detected in samples processed without reverse transcriptase, and the levels of the internal control genes actin (Fig. 1A, inset) and 18S rRNA (data not shown) did not change. Therefore, EMMPRIN induction was a specific response to IL-18, and, in all subsequent experiments, IL-18 was used at 5 ng/ml. To confirm that the response was specific for IL-18, ACMs were treated with neutralizing IL-18 antibodies or IL-18BP-Fc before IL-18 addition, and both significantly inhibited IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN mRNA induction quantified by both quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 1B) and Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1C). Control IgG and Fc had no effect, and all treatments failed to significantly affect the internal controls (Fig. 1, B, inset, and C, middle and bottom). In addition to RNA induction, IL-18 also induced EMMPRIN protein expression in ACMs in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1D) and stimulated EMMPRIN secretion (Fig. 1E). The expression of EMMPRIN protein was not affected by preincubation of the cells with polymyxin B sulphate before IL-18 addition (data not shown), indicating that the response was not mediated by any contaminating endotoxins in the IL-18 preparations.

Fig. 1.

IL-18 induces extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor (EMMPRIN) expression in adult cardiomycytes (ACMs). A: IL-18 induced EMMPRIN mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner. ACMs were incubated with recombinant mouse IL-18 for 2 h. EMMPRIN mRNA expression was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Actin served as an invariant control and is shown in the inset. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.01 (at least) vs. untreated ACMs. B: IL-18 specificity. The specificity of IL-18 was verified by incubating cells with IL-18-neutralizing antibodies or IL-18-binding protein (IL-18BP)-Fc (10 μg/ml for 1 h) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h). EMMPRIN mRNA expression was quantified determined as in A. Actin levels are shown in the inset. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated ACMs; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18 + control IgG or Fc. C: IL-18-induced EMMPRIN mRNA expression was confirmed by Northern blot analysis. ACMs were treated as in B and analyzed for EMMPRIN mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. Both 28S rRNA and actin served as loading controls. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. D: IL-18 induced EMMPRIN protein expression. ACMs treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml) were analyzed for EMMPRIN protein levels by immunoblot analysis. Tubulin served as a loading control. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. E: IL-18 stimulated EMMPRIN secretion. ACM were treated as in E but for 24 h, and EMMPRIN levels in culture supernatants were quantified by immunoblot analysis. Tubulin in the corresponding ACM cell lysates demonstrated that similar numbers of ACMs were plated in both groups. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. F and G: effects of IL-18 were more robust than IL-6 on EMMPRIN mRNA (F) and protein (G) expression. ACMs treated with IL-6 or IL-18 (5 ng/ml) for 2 h (F) or 12 h (G) were analyzed for EMMPRIN mRNA (F; n = 6) or protein expression (G; n = 3). F: *P < 0.05 vs. untreated ACMs; **P < 0.001 vs. untreated ACMs; §P < 0.01 vs. IL-6.

We next compared the effect of IL-18 with IL-6, another proinflammatory cytokine induced during myocardial injury (5). Using each recombinant protein at 5 ng/ml, the response to IL-18 appeared to be more robust than that to IL-6, at both the RNA (Fig. 1E; actin is shown in the inset) and protein level (Fig. 1G). Together, these data indicate that IL-18 is a potent inducer of EMMPRIN expression in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1).

Parallel profiling of transcription factors regulated by IL-18 in ACMs.

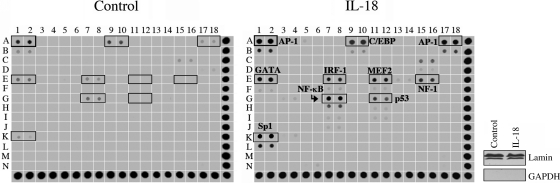

We (7, 38) have previously reported that IL-18 activates the redox-sensitive transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 in SMCs and cardiomyocytes (7, 38). To identify other transcription factors activated/suppressed by IL-18, we used a high-throughput transcription factor array that can identify 54 transcription factors simultaneously (Supplemental Fig. 2). Confirming previous reports (7, 38), IL-18 increased the activations of both AP-1 and NF-κB in ACMs. Moreover, we also found that IL-18 activated GATA, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), myocyte-specific enhancer-binding factor (MEF-2), interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-1, p53, and Sp1 in ACMs (Fig. 2). The purity and equal loading of nuclear extracts were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 2, right) for lamin (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytoplasm). Table 2 shows the DNA sequences of transcription factors induced by IL-18. Interestingly, at this time period, we did not identify transcription factors downregulated by IL-18. These results demonstrate that IL-18 activates multiple transcription factorss in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Parallel profiling of transcription factors (TFs) in ACMs regulated by IL-18. ACM were treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml) for 2 h. Nuclear protein extracts from three independent experiments were pooled and analyzed for protein-DNA interactions using TranSignal Protein/DNA Array 1. The highlighted boxes show the activation of the indicated TFs. The purity of nuclear extracts and equal loading were confirmed by immunoblot analysis (right) using antibodies against lamin (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytoplasmic). AP-1, activator protein-1; GATA, GATA-binding protein; Sp1, specific protein-1; IRF-1, interferon regulatory factor-1; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; MEF-2, myocyte enhancer factor-2; NF, nuclear factor.

Table 2.

Primers used in protein/DNA array 1

| Transcription Factor | Lanes on Array | DNA Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| AP-1 (1) | A1 and A2 | 5′-CGCTTGATGACTCAGCCGGAA-3′ |

| C/EBP | A9 and A10 | 5′-TCGTACTCTCGTACTCTCGTACTCTCGTACTC-3′ |

| AP-1 (2) | A17 and A18 | 5′-GATCAGCTTGATGATGAGTCAGCCCG-3′ |

| GATA | E1 and E2 | 5′-CACTTGATAACAGAAAGTGATAACTCT-3′ |

| MEF-2 | E11 and E12 | 5′-GATCGCGCTAAAAATAACCCTGTCG-3′ |

| IRF-1 | E7 and E8 | 5′-GGAAGCGAAAATGAAATTGACT-3′ |

| NF-1 | E15 and E16 | 5′-TTTTGGATTGAAGCCAATATGATAA-3′ |

| NF-κB | G7 and G8 | 5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′ |

| p53 | G11 and G12 | 5′-TACAGAACATGTCTAAGCATGCTGGGG-3′ |

| Sp1 | K1 and K2 | 5′-ATTCGATCGGGGCGGGGCGAG-3′ |

AP-1, activator protein-1; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein; GATA, GATA-binding protein; MEF-2, myocyte enhancer factor-2; IRF-1, interferon regulatory factor-1; NF, nuclear factor.

IL-18 activates NF-κB, AP-1, and Sp1 in ACMs.

We investigated the activation of NF-κB, AP-1, and Sp1 further using reporter assays, immunoblot analysis, and a signal-profiling ELISA that analyzes both subunit composition and levels. IL-18 significantly activated both p50 and p65 subunits of NF-κB but not c-Rel (Fig. 3A). IL-18 also increased the c-Fos, c-Jun, and FosB subunits of AP-1 but not JunD (Fig. 3A) and Sp1. Using a reporter assay (Fig. 3B) and immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3C), we confirmed that IL-18 mediated NF-κB activation and p65 nuclear translocation in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3C). Similarly, activations of AP-1 (Fig. 3D) and Sp1 (Fig. 3E) were confirmed by a reporter array (AP-1) and ELISA (Sp1). These results support the results from the array (Fig. 2) and demonstrate that IL-18 is a potent inducer of NF-κB, AP-1, and Sp1 in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

IL-18 activates NF-κB, AP-1, and Sp1 in ACMs. A: IL-18-mediated TF activation was confirmed by ELISA using nuclear extracts from ACMs treated with IL-18 as in Fig. 2. Values are means ± SE; n = 3 per group. P < 0.05 (at least) vs. control. B: IL-18-mediated NF-κB activation was confirmed by a reporter assay. ACMs were infected with Ad.NF-κB-Luc [multiplicity of infection (MOI): 50] for 24 h and then treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml). Ad.MCS-Luc served as a control. Cell were coinfected with Ad.β.gal (MOI 50), and both firefly and β-galctosidase levels were quantified after 12 h. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. Ad.MCS-Luc + IL-18. C: activation of NF-κB was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. ACMs were treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml) and then analyzed for phospho-p65 levels by immunoblot analysis using nuclear protein extracts. Lamin served as a purity and loading control. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. D: IL-18 induced AP-1-dependent reporter gene activation. ACMs were infected with Ad.AP-1-Luc, Ad.MCS-Luc, and Ad.β-gal and then analyzed as in B. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. Ad.MCS-Luc + IL-18. E: IL-18 activated Sp1. ACM treated as in A were analyzed for Sp1 activation in nuclear protein extracts using TransAM TF ELISA. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated ACMs.

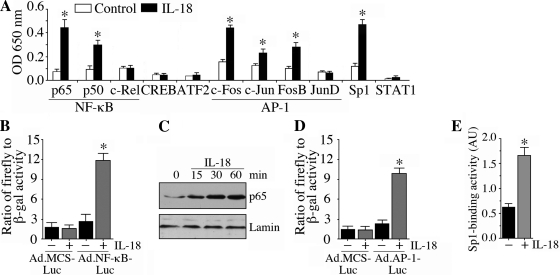

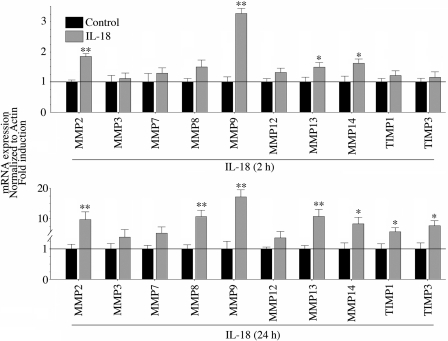

IL-18 induces EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity.

Since EMMPRIN expression is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level, we next investigated whether IL-18 can induce EMMPRIN transcription. ACMs are extremely difficult to transfect using standard transfection protocols. Higher transfection efficiencies (>90%) can be achieved using adenoviral, lentiviral, or retroviral vectors (3, 14); however, this is a complex and time-consuming procedure, and impractical for the preparation of deletion series or mutant DNA promoter constructs. Therefore, we used NMCMs to study the 5′-cis regulatory region of EMMPRIN. NMCMs exhibit much higher efficiency (∼33% using the pEGFP-N1 vector, Clontech) with only 9% cell death. Therefore, NMCMs were transiently transfected with a reporter vector containing a 567-bp fragment of the 5′-flanking region of the EMMPRIN gene (pEMMPRIN-Luc; Fig. 4A) for 24 h and later treated with IL-18 for 12 h. IL-18 induced a fivefold increase in EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity (Fig. 4B), an effect that was moderately, but not significantly, attenuated by the adenoviral transduction of dnp65, dnIκB-α, or kdIKK-β (Fig. 4C) or adenoviral transduction of dncFos (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin or forced expression of a dominant negative mutant Sp1 both significantly attenuated IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN promoter reporter activity (Fig. 4E). Of note, infection with the adenoviral vectors failed to affect cardiomyocyte viability, shape, or adherence. These results suggest that IL-18-induced Sp1 is a major regulator of EMMPRIN transcription in cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

IL-18 induces EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs). A: the EMMPRIN promoter sequence (−538 to −1 relative to the transcription start site) used in the present study. Primers used to amplify the 5′-cis regulatory region (underlined), Sp1-binding sites, mutations in the Sp1-binding sites, and primer sequences used in the chromatin immunoprecipation (ChIP) assay (boxed) are shown. B: IL-18 induced EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity. NMCMs transfected with the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector (3 μg for 24 h) were treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 12 h). pGL3-Basic served as a vector control. pRL-TK served as a loading control. Luciferase activities were determined using the dual luciferase assay kit as been described in methods. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMs. C and D: inhibition of NF-κB (C) or AP-1 (D) failed to significantly modulate IL-18 induced EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity. NMCMs were transfected with the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector (3 μg) for 24 h and then transduced with an adenoviral vector (MOI: 100) expressing dnp65, dnIκB-α, or kdIKK-β (C) or dncFos (D) for 24 h. IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 12) was then added, and cells were processed as in B. GFP, green fluorescent protein. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMs. E: IL-18 stimulated EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity via Sp1. NMCMs transfected with the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector (3 μg for 24 h) were treated with mithramycin (100 nM in DMSO for 45 min) or infected with mutant Sp1 by adenoviral transduction (MOI: 10 for 24 h) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 12) and then processed as in B. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMs; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18.

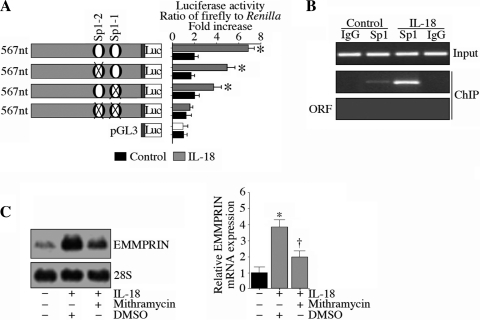

Since the 5′-flanking region of the EMMPRIN gene contains two Sp1-binding sites (highlighted in red in Fig. 4A), we next analyzed their role in EMMPRIN transcription using NMCMs. The mutation of either Sp1-binding site partially, but significantly, reduced IL-18-induced reporter gene activity, whereas mutations of both reduced the response to almost baseline levels (Fig. 5A), indicating that IL-18 induces EMMPRIN transcription via at least two Sp1-binding sites. In support experiments, the ChIP assay showed that IL-18 increased Sp1 DNA binding to the EMMPRIN promoter in vivo (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, pretreatment with the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin significantly attenuated IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN mRNA expression in ACMs (Fig. 5C, Northern blot analysis; results from three independent experiments are shown on the right). These results demonstrate that IL-18 is a potent inducer of EMMPRIN transcription in cardiomyocytes, which is mediated primarily by Sp1 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

IL-18 induces EMMPRIN transcription in NMCMs via Sp1. A: IL-18 induction of EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activation was Sp1 dependent. NMCMs were transfected with wild-type and mutant EMMPRIN promoter-reporter constructs before the addition of IL-18 and then processed as in Fig. 4B. *P < 0.05 (at lease) vs. untreated NMCMs. B: IL-18 stimulated Sp1 binding to the EMMPRIN promoter in vivo. NMCMs were treated with IL-18 for 2 h. Cross-linked chromatin was prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-Sp1 antibody or control IgG before amplification of the EMMPRIN gene region containing Sp1 sites. The EMMPRIN open reading frame (ORF) with a similar amplicon size served as a control. Amplification of the input DNA is shown at the top. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. C: IL-18 induced EMMPRIN mRNA expression via Sp1. ACM were treated with mithramycin (100 nM in DMSO for 45 min) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h). EMMPRIN mRNA expression was analyzed by Northern blot analysis, and results from three independent experiments are shown on the right. *P < 0.01 vs. untreated ACMs; †P < 0.05 vs. IL-18.

IL-18 induces Sp1 activation and EMMPRIN transcription via MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6.

IL-18 is known to signal via Myd88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 (8, 9). Therefore, we next investigated whether IL-18 induces Sp1 activation and EMMPRIN transcription via these intermediates. MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 were targeted by specific siRNA, and their knockdown in NMCMs was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Supplemental Fig. 6A). Both scrambled siRNA and siRNA against GFP (used as controls), however, failed to modulate MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 expression. Knockdown of each of these intermediaries inhibited IL-18-induced Sp1 DNA-binding activity (Fig. 6A) and EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity (Fig. 6B), indicating that IL-18 induces Sp1 activation and EMMPRIN transcription via MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

IL-18 induces Sp1 DNA binding and EMMPRIN promoter-reporter activity via myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88), IL-1 receptor-associated kinase-4 (IRAK4), and TNF receptor-associated factor-6 (TRAF6) in NMCMs. A: IL-18 induced Sp1 DNA-binding activity via MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6. NMCMs were transfected with specific small interfering (si)RNA (100 nM for 48 h) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h). Sp1 DNA-binding activity in nuclear protein extracts was analyzed by ELISA as in Fig. 3E. AU, arbitrary units. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMS; †P < 0.05 (at least) vs. IL-18. B: IL-18 induced EMMPRIN promoter-dependent reporter gene activation via MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6. NMCMs were transfected with MyD88, IRAK4, or TRAF6 siRNA before transfection with the EMMPRIN promoter-reporter vector (3 μg for 24 h) and then treated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml) for 12 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined as in Fig. 4B. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.01 vs. untreated NMCMs; †P < 0.05 (at least) vs. IL-18.

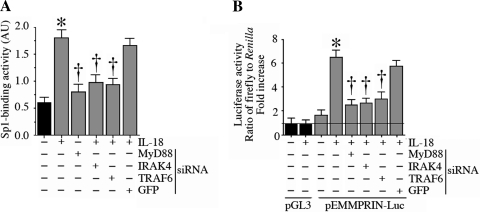

IL-18 activates Sp1 via JNK.

Since IL-18 is a potent inducer of all three stress-activated mitogen kinases in cardiomyocytes (6), we next investigated their role in Sp1 activation. IL-18 induced the phosphorylation of JNK (Fig. 7A), ERK (Fig. 7B), and p38 MAPK (Fig. 7C), effects that were attenuated by their respective inhibitors, SP-600125, PD-98059, and SB-203580. Moreover, knockdown of MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 blunted IL-18-mediated JNK (Fig. 7D), ERK (Fig. 7E), and p38 MAPK (Fig. 7F) activations. However, only SP-600125, but not PD-98059 or SB-203580, significantly attenuated IL-18-mediated Sp1 activation (Fig. 7G). Of note, using the trypan blue dye exclusion test for cell viability, cell death detection ELISAPLUS, and microscopic visualization of cell shape and for cells floating in the media, our results show that at the indicated concentrations and for the duration of treatment, the pharmacological inhibitors did not affect cardiomyocyte shape, adherence, and viability (data not shown). These results demonstrate that IL-18 activates Sp1 via MyD88/IRAK4/TRAF6/JNK signaling (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

IL-18 induces Sp1 activation via JNK. A–C: IL-18 activated JNK (A), ERK (B), and p38 MAPK (C) in NMCMs. NMCMs were treated with SP-600125 (SP; 20 μM in DMSO for 30 min; A), PD-98059 (PD; 10 μM in DMSO for 1 h; B), or SB-203580 (SB; 1 μM in DMSO for 30 min; C) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 1 h). Total and phosphorylated (p-)MAPK levels were analyzed by immunoblot analysis using cleared whole cell lysates and activation-specific antibodies. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. D–F: knockdown of MyD88, IRAK4, and TRAF6 blunted IL-18-mediated JNK (D), ERK (E), and p38 MAPK (F) activations. NMCMs were transfected with MyD88, IRAK4, or TRAF6 siRNA before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 1 h). Total and p-MAPK levels were analyzed by immunoblot analysis. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. G: IL-18 induced Sp1 activation via JNK but not via ERK and p38 MAPK. NMCMs were treated with SP, PD, or SB before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h). Sp1 activation in nuclear protein extracts was analyzed as in Fig. 3E. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMs; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18 + DMSO. H: schema showing the signal transduction pathway involved in IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN expression.

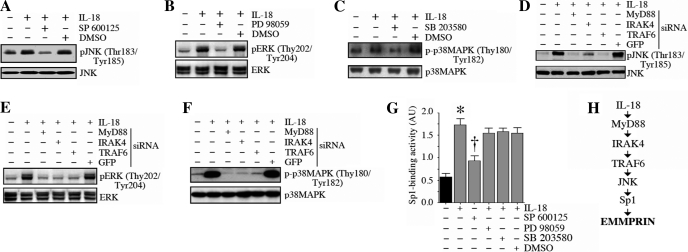

IL-18 induces MMP and TIMP expression in ACMs.

We (7) have previously demonstrated that IL-18 induces MMP-9 expression in SMCs. However, the effects of IL-18 on other MMPs and TIMPs are not known. Therefore, we next investigated the effects of IL-18 on the expression of a panel of MMP and TIMP family members using a quantitative PCR-based array. ACMs were stimulated with 5 ng/ml IL-18, and RNA was isolated at both 2- and 24-h time points for analysis. Compared with untreated controls, IL-18 significantly upregulated MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-13, and MMP-14 at 2 h (Fig. 8, top). MMP-1, MMP-10, MMP-11, MMP-15, and MMP-16 were either extremely low or undetected. In addition, although TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 were detectable under basal conditions, their expression was not significantly modulated by IL-18 at 2 h. Of note, TIMP-2 was not detected, and TIMP-4 was not present on the array. The stimulatory effects of IL-18 were more pronounced at 24 h. In addition to the persistent and increasing upregulation in MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-14, IL-18 also induced significant MMP-8 and MMP-13 expression at 24 h. Furthermore, TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 expression were significantly higher at this time point, demonstrating their delayed induction. Notably, MMP-9 expression was the most elevated at both 2 h and 24 h. Together, these results suggest that IL-18 favors the enhanced expression of MMPs in ACMs (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

EMMPRIN induces various matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitors [tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase (TIMPs)] in ACMs. ACMs were incubated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml) for 2 h (top) or 24 h (bottom). DNA-free total RNA was analyzed for MMPs and TIMPs using a quantitative PCR-based array. Expression levels in the respective controls were considered as 1, and the induction after IL-18 treatment is shown as the fold change. Values are means ± SE; n = 6. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001 vs. control.

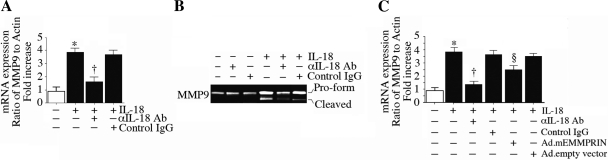

IL-18 induces MMP-9 expression in ACMs.

Since MMP-9 expression was the highest at both 2 and 24 h, we next investigated the molecular mechanisms involved in its induction. Since EMMPRIN is a potent inducer of MMP-9, we also investigated whether IL-18-induced MMP-9 is EMMPRIN dependent. Confirming the array results (Fig. 8), quantitative RT-PCR revealed significant upregulation in MMP-9 mRNA expression in IL-18-treated ACMs at 2 h (Fig. 9A), an effect that was markedly attenuated by preincubation with IL-18-neutralizing antibodies. Furthermore, IL-18 stimulated MMP-9 pro-enzyme and enzyme levels (zymography; Fig. 9B). Importantly, overexpression of mutant EMMPRIN by adenoviral transduction, moderately but significantly attenuated IL-18-induced MMP-9 expression (Fig. 9C), indicating that IL-18 induces MMP-9 in part via EMMPRIN (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

IL-18 induces MMP-9 expression in part via EMMPRIN in ACMs. A: IL-18 induced MMP-9 mRNA expression. ACMs treated with IL-18-neutralizing antibodies or control IgG (10 μg/ml for 1 h) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 2 h) were analyzed for MMP-9 mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR. Actin served as an invariant control. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated ACMs; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18. B: detection of IL-18-induced MMP-9 pro-enzyme and enzyme. ACMs were treated as in A but for 24 h. MMP-9 levels in culture supernatants were analyzed by gelatin zymography. Values are means ± SE; n = 3. C: IL-18 induced MMP-9 mRNA expression in part via EMMPRIN. ACMs were transduced with adenoviral mEMMPRIN (MOI: 50 for 24 h) before the addition of IL-18. Ad.GFP served as a control. MMP-9 mRNA expression was analyzed as in A. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated ACMs; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18 + Ad.mEMMPRIN; §P < 0.05 vs. IL-18 + Ad.empty vector.

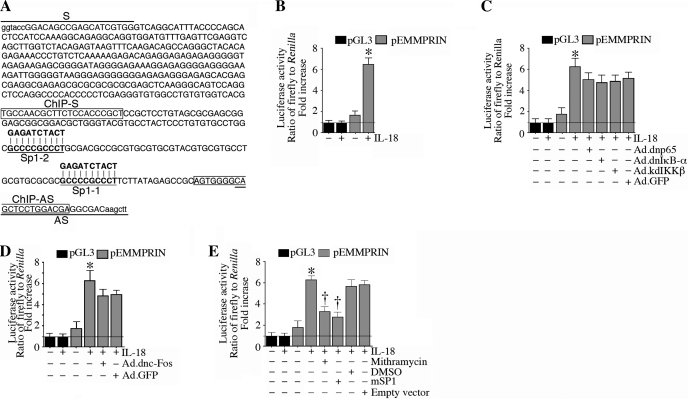

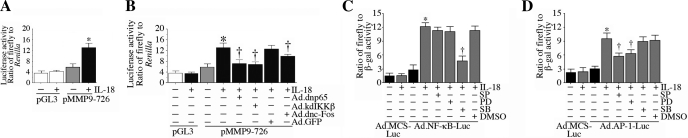

IL-18 induces MMP-9 expression via NF-κB and AP-1 activation.

Since MMP-9 is an NF-κB- and AP-1-responsive gene, we next investigated their role in IL-18-mediated MMP-9 expression. NMCMs were transiently transfected with the MMP-9 promoter-reporter vector and then treated with IL-18. As expected, IL-18 markedly increased MMP-9 promoter-dependent reporter gene activity (Fig. 10A), an effect that was significantly inhibited by Ad.dnp65, Ad.kdIKK-β, and Ad.dncFos (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, whereas inhibition of p38 MAPK attenuated IL-18-mediated NF-κB activation, inhibition of both ERK and JNK attenuated AP-1 activation. These results indicate that in addition to inducing MMP-9 indirectly via EMMPRIN, IL-18 also induces MMP-9 transcription directly through p38 MAPK-dependent NF-κB and JNK- and ERK-dependent AP-1 activation (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

IL-18 induces MMP-9 promoter-reporter activation via MAPK-dependent NF-κB and AP-1 activations. A: IL-18 induced MMP-9 promoter-reporter activation. NMCMs transiently transfected with the MMP-9 promoter-reporter vector (pMMP-9-726; 3 μg for 24 h) were incubated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 12 h). pGL3-Basic served as a vector control. pRL-TK was used to equalize for variations in transfection efficiency. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined as in Fig. 4B. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.01 vs. pGL3 + IL-18. B: IL-18 induced MMP-9 promoter-reporter activity via NF-κB and AP-1. NMCMs transfected with the MMP-9 promoter-reporter vector (3 μg for 24 h) were infected with NF-κB or AP-1 mutant expression vectors by adenoviral transduction (MOI: 10 for 24 h) before the addition of IL-18 (5 ng/ml for 12). Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were determined as in Fig. 4B. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated NMCMs; †P < 0.05 (at least) vs. IL-1 8 +Ad.GFP. C: IL-18 induced NF-κB activation via p38 MAPK. NMCMs infected with Ad.NF-κB-Luc (MOI: 50) for 24 h were treated with SB-203580, PD-98059, or SP-600125 and then incubated with IL-18 (5 ng/ml). Ad.MCS-Luc served as a control. Cell were coinfected with Ad.β.gal (MOI: 50), and both firefly and β-galctosidase levels were quantified after 12 h. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.001 vs. Ad.MCS-Luc + IL-18; †P < 0.01 vs. IL-18 + DMSO. D: IL-18 induced AP-1 activation via JNK and ERK. NMCMs infected with Ad.AP-1-Luc (MOI: 50) for 24 h were treated and processed as in C. Values are means ± SE; n = 12. *P < 0.01 vs. Ad.MCS-Luc + IL-18; †P < 0.05 (at least) vs. IL-18 + DMSO.

DISCUSSION

There is increasing evidence that the pleiotropic cytokine IL-18 plays a significant role in adverse myocardial remodeling, a process characterized by a delicate balance between MMPs and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs). Here, we show, for the first time, that IL-18 is a potent inducer of various MMPs in cardiomyocytes, with a predominant induction of MMP-9. Interestingly, IL-18 also induces TIMP-1 and TIMP-3, but in a delayed fashion. We also show that IL-18 induces the MMP inducer EMMPRIN in cardiomyocytes via JNK-dependent Sp1 activation and that of MMP-9 via p38 MAPK-dependent NF-κB and JNK- and ERK-dependent AP-1 activation. Furthermore, we also show that EMMPRIN is partially responsible for the induction of MMP-9. These in vitro results suggest that the elevated cardiomyocyte and noncardiomyocyte-derived IL-18 in vivo during myocardial injury and inflammation may favor EMMPRIN and MMP induction, ECM degradation, and adverse remodeling.

We also show, for the first time, that IL-18 can induce detectable levels of MMP-2, MMP-13, and MMP-14 mRNA in cardiomyocytes within 2 h of treatment, and these are enhanced after 24 h. MMP-8 is also detectable by 24 h. These data, combined with the observed slow and relatively low induction of TIMP-1 and TIMP-3, support our hypothesis that the elevated expression of IL-18 seen during myocardial injury and inflammation favors MMP induction, ECM degradation, and adverse remodeling. Furthermore, since IL-18 has been shown to induce various cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors that are known inducers of MMPs and TIMPs, it is reasonable to speculate that IL-18 may induce MMPs and TIMPs in concert with these inflammatory molecules. Our future studies will determine this possibility using suboptimal concentrations of IL-18 in combination with other cytokines.

IL-18 activates various transcription factors in cardiomyocytes. In addition to previously reported NF-κB, AP-1, and GATA (6, 7), we identified C/EBP, MEF-2, IRF-1, p53, and Sp1 as IL-18-responsive factors. In addition, using a variety of assays, we found that IL-18-activated NF-κB in cardiomyocytes was composed of mainly of p65 and p50 and activated AP-1 of c-Fos, c-Jun, and JunD. Since MMPs can be broadly divided into various subgroups based on their inducibility by AP-1 and NF-κB as well as the location of their binding sites in their proximal promoter regions (49), it is possible that they are regulated differentially by these cis regulatory elements. It is also possible that IL-18 may regulate the expression of MMPs at transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Despite few CpG islands in the promoter regions of MMPs, epigenetic mechanisms have also been shown to significantly affect MMP expression (43). For example, increased promoter methylation has been shown to suppress MMP-9 transcription (49). Therefore, it is possible that IL-18 may regulate the expression of MMPs by both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. In addition to various MMPs, we have also reported that IL-18 induces TIMP expression in cardiomyocytes, but in a delayed fashion. Of note, both TIMP-1 and TIMP-3 are also AP-1 responsive (11, 23). Since other cytokines also activate AP-1, it is possible that IL-18-induced intermediaries might have contributed to their delayed induction.

Another critical observation of the present study is that IL-18 induces the MMP inducer EMMPRIN in cardiomyocytes and that EMMPRIN partially contributes to IL-18-induced MMP expression. These results suggest EMMPRIN-dependent and -independent effects of IL-18 on MMP and TIMP expression. Since both IL-18 and EMMPRIN play a role in myocardial hypertrophy and failure, their synergistic or additive effects may enhance adverse remodeling. We also showed that IL-18 induces EMMPRIN transcription through Sp1 activation rather than through NF-κB and AP-1. EMMPRIN promoter-dependent reporter gene activation was significantly attenuated when the two Sp1-binding sites in the EMMPRIN proximal promoter region were mutated. Similarly, pretreatment with the Sp1 inhibitor mithramycin and overexpression of mutant Sp1 both blunted EMMPRIN expression. In addition to the Sp1-binding sites, the EMMPRIN proximal promoter also contains putative binding sites for AP-1, AP-2, early growth response 2, and transciption factor 2. However, neither overexpression of mutant AP-1 (dncFos) nor of mutant NF-κB (dnp65, dnIκB-α, or kdIKK-β) negatively or positively regulated IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN transcription, suggesting that Sp1 is the most potent transcriptional activator of EMMPRIN in cardiomyocytes.

Consistent with our previous results (8, 9), here, we also show that IL-18 activates Sp1 via MyD88-, IRAK4-, and TRAF6-dependent JNK activation. Interestingly, although IL-18 activated JNK, which is an upstream regulator of AP-1, and even though EMMPRIN contains an AP-1-binding site in its 5′-flanking region, targeting AP-1 failed to significantly modulate IL-18-mediated EMMPRIN transcription. It is, however, possible that AP-1 as well as NF-κB may productively cooperate with Sp1 and enhance EMMPRIN transcription. In support of this hypothesis, it has been previously reported that Sp1 interacts with NF-κB, and their functional and physical interactions activate human immunodeficiency virus-1 enhancer (28). Similarly, Sp1-AP-1 interactions have been shown to mediate EGF-induced 12(S)-lipoxygenase gene expression (10).

Although we report here several novel findings such as IL-18 dependent activation of multiple transcription factors, time-dependent expression of various MMPs and TIMPs, induction of the MMP inducer EMMPRIN, EMMPRIN-dependent MMP-9 expression, and the underlying molecular mechanisms, our study has some limitations. For example, although it has been reported that systemic IL-18 concentrations in vivo vary widely between 200 and 900 pg/ml in various pathophysiological conditions (19, 52), we used 5 ng/ml IL-18 to study the response pathways underlying the induction of EMMPRIN and MMP-9. This concentration is somewhat high but is in line with levels (1–100 ng/ml) used in previous studies (6–9, 50). However, in the present study, we were able to detect EMMPRIN expression with 1 ng/ml IL-18, which is near the upper level measured in pathophysiological conditions in vivo. Another possible limitation is that we used both adult and neonatal cardiomyocytes to investigate the effects of IL-18. Although the majority of the experiments were performed in ACMs, experiments involving transcriptional regulation and siRNA transfection were performed in NMCMs, as they have higher transfection efficiency. Another limitation is that we performed the transcription factor array experiments at 2 h after IL-18 treatment. Since trancription factors are regulated differentially and temporally, we might have missed those factors that may be activated by IL-18 at later time points. Studies are in progress to determine the time-dependent changes in trancription factor activation/inactivation in IL-18-treated cardiomyocytes. Additionally, we investigated the effects of IL-18 by delivering recombinant protein exogenously. Therefore, our findings may not fully represent the events in vivo, where IL-18 is generated locally as well as systemically. We generated adenovirus expressing tetracycline-inducible mature IL-18 and plan to examine the effects of regulatable, pathophysiological levels of IL-18 on EMMPRIN and other ECM-related genes in the future. Notwithstanding these possible limitations, our results support the hypothesis that IL-18 overexpression during myocardial injury and inflammation favors MMP induction and ECM degradation and is thus a potential therapeutic target to counter adverse remodeling after cardiac injury.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service Award 1101BX007080 (to B. Chandrasekar) and by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-86787 (to B. Chandrasekar) and HL-70241 and HL-80682 (to P. Delafontaine). V. S. Reddy was a recipient of Undergraduate Research Collaborative/New Investigator Award administered by the University of Texas Health Science Center (San Antonio, Texas).

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Footnotes

Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benotmane AM, Hoylaerts MF, Collen D, Belayew A. Nonisotopic quantitative analysis of protein-DNA interactions at equilibrium. Anal Biochem 250: 181–185, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berditchevski F, Chang S, Bodorova J, Hemler ME. Generation of monoclonal antibodies to integrin-associated proteins. Evidence that α3β1 complexes with EMMPRIN/basigin/OX47/M6. J Biol Chem 272: 29174–29180, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonci D, Cittadini A, Latronico MV, Borello U, Aycock JK, Drusco A, Innocenzi A, Follenzi A, Lavitrano M, Monti MG, Ross J, Jr, Naldini L, Peschle C, Cossu G, Condorelli G. “Advanced” generation lentiviruses as efficient vectors for cardiomyocyte gene transduction in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther 10: 630–636, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Born TL, Thomassen E, Bird TA, Sims JE. Cloning of a novel receptor subunit, AcPL, required for interleukin-18 signaling. J Biol Chem 273: 29445–29450, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasekar B, Mitchell DH, Colston JT, Freeman GL. Regulation of CCAAT/Enhancer binding protein, interleukin-6, interleukin-6 receptor, and gp130 expression during myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 99: 427–433, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandrasekar B, Mummidi S, Claycomb WC, Mestril R, Nemer M. Interleukin-18 is a pro-hypertrophic cytokine that acts through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1-Akt-GATA4 signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem 280: 4553–4567, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandrasekar B, Mummidi S, Mahimainathan L, Patel DN, Bailey SR, Imam SZ, Greene WC, Valente AJ. Interleukin-18-induced human coronary artery smooth muscle cell migration is dependent on NF-κB- and AP-1-mediated matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression and is inhibited by atorvastatin. J Biol Chem 281: 15099–15109, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandrasekar B, Mummidi S, Valente AJ, Patel DN, Bailey SR, Freeman GL, Hatano M, Tokuhisa T, Jensen LE. The pro-atherogenic cytokine interleukin-18 induces CXCL16 expression in rat aortic smooth muscle cells via MyD88, interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6, c-Src, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and activator protein-1 signaling. J Biol Chem 280: 26263–26277, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandrasekar B, Vemula K, Surabhi RM, Li-Weber M, Owen-Schaub LB, Jensen LE, Mummidi S. Activation of intrinsic and extrinsic proapoptotic signaling pathways in interleukin-18-mediated human cardiac endothelial cell death. J Biol Chem 279: 20221–20233, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang WC, Chen BK. Transcription factor Sp1 functions as an anchor protein in gene transcription of human 12(S)-lipoxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338: 117–121, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark IM, Rowan AD, Edwards DR, Bech-Hansen T, Mann DA, Bahr MJ, Cawston TE. Transcriptional activity of the human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1 (TIMP-1) gene in fibroblasts involves elements in the promoter, exon 1 and intron 1. Biochem J 324: 611–617, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colston JT, Boylston WH, Feldman MD, Jenkinson CP, de la Rosa SD, Barton A, Trevino RJ, Freeman GL, Chandrasekar B. Interleukin-18 knockout mice display maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 354: 552–558, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18. Methods 19: 121–132, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Djurovic S, Iversen N, Jeansson S, Hoover F, Christensen G. Comparison of nonviral transfection and adeno-associated viral transduction on cardiomyocytes. Mol Biotechnol 28: 21–32, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducharme A, Frantz S, Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Lindsey M, Rohde LE, Schoen FJ, Kelly RA, Werb Z, Libby P, Lee RT. Targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates left ventricular enlargement and collagen accumulation after experimental myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 106: 55–62, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagemann T, Wilson J, Kulbe H, Li NF, Leinster DA, Charles K, Klemm F, Pukrop T, Binder C, Balkwill FR. Macrophages induce invasiveness of epithelial cancer cells via NF-κB and JNK. J Immunol 175: 1197–1205, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heymans S, Lupu F, Terclavers S, Vanwetswinkel B, Herbert JM, Baker A, Collen D, Carmeliet P, Moons L. Loss or inhibition of uPA or MMP-9 attenuates LV remodeling and dysfunction after acute pressure overload in mice. Am J Pathol 166: 15–25, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huet E, Vallee B, Szul D, Verrecchia F, Mourah S, Jester JV, Hoang-Xuan T, Menashi S, Gabison EE. Extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer/CD147 promotes myofibroblast differentiation by inducing alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and collagen gel contraction: implications in tissue remodeling. FASEB J 22: 1144–1154, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulthe J, McPheat W, Samnegard A, Tornvall P, Hamsten A, Eriksson P. Plasma interleukin (IL)-18 concentrations is elevated in patients with previous myocardial infarction and related to severity of coronary atherosclerosis independently of C-reactive protein and IL-6. Atherosclerosis 188: 450–454, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacono KT, Brown AL, Greene MI, Saouaf SJ. CD147 immunoglobulin superfamily receptor function and role in pathology. Exp Mol Pathol 83: 283–295, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Igakura T, Kadomatsu K, Kaname T, Muramatsu H, Fan QW, Miyauchi T, Toyama Y, Kuno N, Yuasa S, Takahashi M, Senda T, Taguchi O, Yamamura K, Arimura K, Muramatsu T. A null mutation in basigin, an immunoglobulin superfamily member, indicates its important roles in peri-implantation development and spermatogenesis. Dev Biol 194: 152–165, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imam SZ, Jankovic J, Ali SF, Skinner JT, Xie W, Conneely OM, Le WD. Nitric oxide mediates increased susceptibility to dopaminergic damage in Nurr1 heterozygous mice. FASEB J 19: 1441–1450, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H, Pennie WD, Sun Y, Colburn NH. Differential functional significance of AP-1 binding sites in the promoter of the gene encoding mouse tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3. Biochem J 324: 547–553, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SH, Eisenstein M, Reznikov L, Fantuzzi G, Novick D, Rubinstein M, Dinarello CA. Structural requirements of six naturally occurring isoforms of the IL-18 binding protein to inhibit IL-18. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 1190–1195, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mallat Z, Henry P, Fressonnet R, Alouani S, Scoazec A, Beaufils P, Chvatchko Y, Tedgui A. Increased plasma concentrations of interleukin-18 in acute coronary syndromes. Heart 88: 467–469, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallat Z, Heymes C, Corbaz A, Logeart D, Alouani S, Cohen-Solal A, Seidler T, Hasenfuss G, Chvatchko Y, Shah AM, Tedgui A. Evidence for altered interleukin 18 (IL)-18 pathway in human heart failure. FASEB J 18: 1752–1754, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel DN, Bailey SR, Gresham JK, Schuchman DB, Shelhamer JH, Goldstein BJ, Foxwell BM, Stemerman MB, Maranchie JK, Valente AJ, Mummidi S, Chandrasekar B. TLR4-NOX4-AP-1 signaling mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced CXCR6 expression in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 347: 1113–1120, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perkins ND, Agranoff AB, Pascal E, Nabel GJ. An interaction between the DNA-binding domains of RelA(p65) and Sp1 mediates human immunodeficiency virus gene activation. Mol Cell Biol 14: 6570–6583, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raeburn CD, Dinarello CA, Zimmerman MA, Calkins CM, Pomerantz BJ, McIntyre RC, Jr, Harken AH, Meng X. Neutralization of IL-18 attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H650–H657, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seta Y, Kanda T, Tanaka T, Arai M, Sekiguchi K, Yokoyama T, Kurimoto M, Tamura J, Kurabayashi M. Interleukin-18 in patients with congestive heart failure: induction of atrial natriuretic peptide gene expression. Res Commun Mol Pathol Pharmacol 108: 87–95, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siwik DA, Kuster GM, Brahmbhatt JV, Zaidi Z, Malik J, Ooi H, Ghorayeb G. EMMPRIN mediates β-adrenergic receptor-stimulated matrix metalloproteinase activity in cardiac myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 44: 210–217, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.SoRelle R. Interleukin-18 predicts coronary events. Circulation 108: e9051–e9065, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinale FG, Coker ML, Heung LJ, Bond BR, Gunasinghe HR, Etoh T, Goldberg AT, Zellner JL, Crumbley AJ. A matrix metalloproteinase induction/activation system exists in the human left ventricular myocardium and is upregulated in heart failure. Circulation 102: 1944–1949, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev 79: 215–262, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Y, Kesavan P, Nakada MT, Yan L. Tumor-stroma interaction: positive feedback regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer (EMMPRIN) expression and matrix metalloproteinase-dependent generation of soluble EMMPRIN. Mol Cancer Res 2: 73–80, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torigoe K, Ushio S, Okura T, Kobayashi S, Taniai M, Kunikata T, Murakami T, Sanou O, Kojima H, Fujii M, Ohta T, Ikeda M, Ikegami H, Kurimoto M. Purification and characterization of the human interleukin-18 receptor. J Biol Chem 272: 25737–25742, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyagi SC, Kumar SG, Haas SJ, Reddy HK, Voelker DJ, Hayden MR, Demmy TL, Schmaltz RA, Curtis JJ. Post-transcriptional regulation of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase in human heart end-stage failure secondary to ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 1415–1428, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venkatachalam K, Prabhu SD, Reddy VS, Boylston WH, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Neutralization of interleukin-18 ameliorates ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial injury. J Biol Chem 284: 7853–7865, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venkatachalam K, Venkatesan B, Valente AJ, Melby PC, Nandish S, Reusch JE, Clark RA, Chandrasekar B. WISP1, a pro-mitogenic, pro-survival factor, mediates tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)-stimulated cardiac fibroblast proliferation but inhibits TNF-α-induced cardiomyocyte death. J Biol Chem 284: 14414–14427, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkatesan B, Prabhu SD, Venkatachalam K, Mummidi S, Valente AJ, Clark RA, Delafontaine P, Chandrasekar B. WNT1-inducible signaling pathway protein-1 activates diverse cell survival pathways and blocks doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte death. Cell Signal 22: 809–820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venkatesan B, Valente AJ, Prabhu SD, Shanmugam P, Delafontaine P, Chandrasekar B. EMMPRIN activates multiple transcription factors in cardiomyocytes, and induces interleukin-18 expression via Rac1-dependent PI3K/Akt/IKK/NF-κB andMKK7/JNK/AP-1 signaling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. In press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Venkatesan B, Valente AJ, Reddy VS, Siwik DA, Chandrasekar B. Resveratrol blocks interleukin-18-EMMPRIN cross-regulation and smooth muscle cell migration. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H874–H886, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE. Signal transduction and cell-type specific regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression: can MMPs be good for you? J Cell Physiol 213: 355–364, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Haehling S, Schefold JC, Lainscak M, Doehner W, Anker SD. Inflammatory biomarkers in heart failure revisited: much more than innocent bystanders. Heart Fail Clin 5: 549–560, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wakatsuki T, Schlessinger J, Elson EL. The biochemical response of the heart to hypertension and exercise. Trends Biochem Sci 29: 609–617, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M, Markel TA, Meldrum DR. Interleukin 18 in the heart. Shock 30: 3–10, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M, Tan J, Wang Y, Meldrum KK, Dinarello CA, Meldrum DR. IL-18 binding protein-expressing mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial protection after ischemia or infarction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 17499–17504, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woldbaek PR, Sande JB, Stromme TA, Lunde PK, Djurovic S, Lyberg T, Christensen G, Tonnessen T. Daily administration of interleukin-18 causes myocardial dysfunction in healthy mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H708–H714, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan C, Boyd DD. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J Cell Physiol 211: 19–26, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshimoto T, Mizutani H, Tsutsui H, Noben-Trauth N, Yamanaka K, Tanaka M, Izumi S, Okamura H, Paul WE, Nakanishi K. IL-18 induction of IgE: dependence on CD4+ T cells, IL-4 and STAT6. Nat Immunol 1: 132–137, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu Q, Vazquez R, Khojeini EV, Patel C, Venkataramani R, Larson DF. IL-18 induction of osteopontin mediates cardiac fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H76–H85, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuen CM, Chiu CA, Chang LT, Liou CW, Lu CH, Youssef AA, Yip HK. Level and value of interleukin-18 after acute ischemic stroke. Circ J 71: 1691–1696, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zabalgoitia M, Colston JT, Reddy SV, Holt JW, Regan RF, Stec DE, Rimoldi JM, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. Carbon monoxide donors or heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) overexpression blocks interleukin-18-mediated NF-κB-PTEN-dependent human cardiac endothelial cell death. Free Radic Biol Med 44: 284–298, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaremba J, Losy J. Interleukin-18 in acute ischaemic stroke patients. Neurol Sci 24: 117–124, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zavadzkas JA, Plyler RA, Bouges S, Koval CN, Rivers WT, Beck CU, Chang EI, Stroud RE, Mukherjee R, Spinale FG. Cardiac-restricted overexpression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer causes myocardial remodeling and dysfunction in aging mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H1394–H1402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]