Abstract

Certain primary transcripts of miRNA (pri-microRNAs) undergo RNA editing that converts adenosine to inosine. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) genome encodes multiple microRNA genes of its own. Here we report that primary transcripts of ebv-miR-BART6 (pri-miR-BART6) are edited in latently EBV-infected cells. Editing of wild-type pri-miR-BART6 RNAs dramatically reduced loading of miR-BART6-5p RNAs onto the microRNA-induced silencing complex. Editing of a mutation-containing pri-miR-BART6 found in Daudi Burkitt lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma C666-1 cell lines suppressed processing of miR-BART6 RNAs. Most importantly, miR-BART6-5p RNAs silence Dicer through multiple target sites located in the 3′-UTR of Dicer mRNA. The significance of miR-BART6 was further investigated in cells in various stages of latency. We found that miR-BART6-5p RNAs suppress the EBNA2 viral oncogene required for transition from immunologically less responsive type I and type II latency to the more immunoreactive type III latency as well as Zta and Rta viral proteins essential for lytic replication, revealing the regulatory function of miR-BART6 in EBV infection and latency. Mutation and A-to-I editing appear to be adaptive mechanisms that antagonize miR-BART6 activities.

Keywords: Dicer, Double-stranded RNA, MicroRNA, RNA, RNA Editing, ADAR, Epstein-Barr Virus, Virus Latency

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs)2 play important roles in many processes including development, differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (1, 2). Certain miRNAs act as tumor suppressors or oncogenes and are associated with many cancers (3). Primary transcripts of miRNA genes (pri-miRNAs) are processed sequentially by Drosha and Dicer (4, 5). Nuclear Drosha (6) together with its partner DGCR8 (7, 8) cleaves pri-miRNAs, releasing 60–70-nucleotide pre-miRNAs. Recognition of correctly processed pre-miRNAs and their nuclear export is carried out by exportin-5 and RanGTP (9). Cytoplasmic Dicer together with the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding protein TRBP then cleaves pre-miRNAs into 20–22-nucleotide siRNA-like duplexes (10, 11). In most cases one strand of the duplex (called the effective strand) serves as the mature miRNA, whereas the other strand (called passenger strand) is eliminated. After integration into the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC), miRNAs block translation via partially complementary binding sites located in the 3′-UTRs of targeted mRNAs or guide the degradation of target mRNAs after binding, mainly via the 5′ half of the miRNA sequence, called the “seed sequence” (1, 4, 5).

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) causes mononucleosis during acute and lytic infection and also establishes a persistent and latent infection in the human host. Latently infected EBV has been demonstrated to be associated with a variety of human cancers such as Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (12, 13). Lytic infection and transition to distinctive states of latency (type I-III) are regulated by select viral genes and their interaction with the host immune system (12, 13). Virus genomes encode miRNAs of their own, and the first viral miRNA was identified in human B cells infected with EBV (14). A total of 23 EBV miRNA genes are known and located in the BHRF1 and BART (Bam H1 A rightward transcript) regions of the genome (15–17). These EBV miRNAs have been implicated in regulating the transition from lytic replication to latent infection and in attenuating antiviral immune responses (18). However, only a limited number of their targets have been identified so far. The viral miRNAs seem to target both viral and host cell genes (18). For instance, miR-BART2 targets the EBV DNA polymerase, BALF5, perhaps promoting entry of the virus to latency by slowing down viral replication at the transition point from lytic to latent infection (19). Down-regulation of the EBV protein LMP1 by three EBV miRNAs, miR-BART1–5p, miR-BART16, and miR-BART17–5p, has been reported (20). LMP1 produced during the EBV type II and III latency controls the NF-κβ signaling pathway and growth and apoptosis of host cells. Targeting of host cell genes PUMA (p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis) by miR-BART5 (21) and CXC-chemokine ligand 11 (CXCL11) by miR-BHRF1–3 (22) have been reported. Down-regulation of PUMA may suppress apoptosis of virus-infected host cells (21), whereas suppression of CXCL11 may shield EBV-infected B cells from cytotoxic T cells (22).

One type of RNA editing involves the conversion of adenosine residues into inosine (A-to-I editing) in dsRNA through the action of adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR). Three ADAR gene family members (ADAR1–3) have been identified in humans and rodents (23, 24). The translation machinery reads an inosine as if it were guanosine, which could lead to codon changes (25). Thus, when A-to-I RNA editing occurs within a coding sequence, synthesis of proteins not directly encoded by the genome can result, as demonstrated with transcripts of glutamate receptor ion channels and 5-HT2C serotonin receptors (26). However, the most common targets for A-to-I editing are non-coding RNAs that contain inverted repeats of repetitive elements such as Alu elements and LINEs located within introns and 3′-UTRs (27–30). The biological significance of non-coding, repetitive RNA editing is largely unknown. Furthermore, editing of certain pri-miRNAs has been reported (31, 32). A recent survey has revealed that ∼20% of human pri-miRNAs are subject to A-to-I RNA editing catalyzed by ADAR1 and ADAR2 (33). Editing of pri-miRNAs modulates expression and function of miRNAs (33). For instance, A-to-I editing of several adenosine residues located near the Drosha cleavage sites of pri-miRNA-142 results in inhibition of the processing by Drosha and consequent down-regulation of mature miR-142 RNAs (34), whereas editing of two sites identified near the end loop of the pri-miR-151 hairpin structure inhibits the Dicer cleavage step (35). By contrast, editing of primary transcripts of the miR-376 cluster at two sites located within the seed sequence does not affect their processing but results in expression of mature-edited miR-376 RNAs with altered seed sequences and consequent silencing of a set of genes different from those targeted by unedited miR-376 RNAs (36).

In this study we set out to examine editing of EBV miRNAs in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid GM607 cells, Burkitt lymphoma Daudi cells, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma C666-1 cells. Human lymphoblastoid cells such as GM607 cells in type III latency express a set of genes essential for this specific state of latency, such as EBNA2 and LMP1. By contrast, Daudi Burkitt lymphoma cells in the restricted sub-type of type III latency do not express EBNA2 due to the genomic deletion (37, 38). Viral infection in C666-1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells is associated with more restricted forms of type II latency, which expresses only a limited number of viral genes, representing a less immune-responsive state (38). We have found that primary transcripts of four EBV miRNAs, including miR-BART6, are subject to A-to-I editing. Moreover, we demonstrate that editing of pri-miR BART6 RNAs as well as mutations of miR-BART6 RNAs found in latently EBV-infected cells inhibits expression or their loading onto the functionally active miRISC. Most significantly, we found that miR-BART6 targets Dicer and affects the latent state of EBV viral infection. Regulation of the miR-BART6 expression and function through A-to-I editing and mutation may be critical for the establishment or maintenance of latent EBV infection.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell line GM607 (GM00607) was obtained from Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ). Burkitt lymphoma cell line Daudi was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Burkitt lymphoma Mutu I and Mutu III and nasopharyngeal carcinoma line C666-1 were used in our previous studies (39–41). These cell lines were cultured in RPMI1640 (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA), supplemented with 100 units/ml benzylpenicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin sulfate (both from Invitrogen) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Tissue Culture Biological, Tulare, CA). HeLa and HEK293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS.

Analysis of in Vitro Processed Pri-miRNA Products by Northern Blotting

Nonradioactive pri-miR-BART6 RNAs (10 fmol) were synthesized by in vitro transcription and processed by Drosha-DGCR8 (20 ng) and/or Dicer-TRBP complexes (20 ng) as described previously (34). Processed RNAs were electrophoresed on a 15% polyacrylamide, 8 m urea gel and transferred to a Hybond XL membrane (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting. Membranes were UV-cross-linked (StrataLinker; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and hybridized with 5′-32P-labeled miRCURY locked nucleic acid probes (Exiqon Inc., Woburn, MA) and analyzed by Northern blotting. The hybridization buffer contained 50% formamide, 0.5% SDS, 5× saline/sodium phosphate/EDTA, 5× Denhardt's solution, and 20 μg/ml sheared, denatured, salmon sperm DNA. Hybridization was conducted at 34 °C. Membranes were washed by 2× SSC/0.1% SDS, and hybridized signals were quantified by a Typhoon Imager System.

Luciferase Reporter Constructs

The human Dicer 3′-UTR (1498 bp), which contains four miR-BART6-5p binding sites (supplemental Experimental Procedures), were amplified using human genomic DNA extracted from GM607 cells and specific primers hDicerFW (5′-GCTACTAGTGATCTTTGGCTAAACACCCCAT-3′) and hDicerRV (5′-GCTGTTTAAACCTCCAACAAAAAGTGAAACGGC-3′). The PCR products were inserted into a luciferase reporter vector (pMIR-REPORTTM Luciferase; Ambion) after digestion with Spe1 and Pml1.

Transfections of miR-BART6 RNAs

miR-BART6-5p and unedited miR-BART6–3p RNA duplexes were synthesized at Ambion (Pre-miRTM miRNA). All transfections were carried out in triplicate as described previously (42). Briefly, HeLa cells were pre-plated in 24-well tissue culture plates. 200 ng of luciferase reporter plasmid and 200 ng of control vector pMIR-REPORTTM β-galactosidase Control Plasmid (Ambion) were diluted into 50 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) with or without 10 pmol of miR-BART6 duplex or sequence unrelated control miRNA, cel-miR-67, or miR-376a followed by the addition of 3 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The transfection mixture was incubated at room temperature for 5 min followed by the addition of DNA/miR-BART6 and further incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Then 100 μl of transfection mixture was added to the HeLa cells in 500 μl of the growth medium. Transfection efficiency monitored by using 5-carboxylfluorescein-labeled control siRNA (Ambion) was more than 80%. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) together with β-galactosidase activity by reading the absorbance at 415 nm in a plate reader with the β-Galactosidase Enzyme Assay System (Promega). Normalized luciferase values divided by the β-galactosidase activity were statistically compared among each group by Mann-Whitney U test.

Transfections of the miR-BART6-5p Antagomir

C666.1 or Mutu I cells (1.5 × 105 cells) were cultured in 24-well plates. The next day cells were transfected with 50 pmol of inhibitor of miR-BART6-5p (miScript miRNA inhibitor, Qiagen) or AllStars Negative Control siRNA (Qiagen) using 3 μl of Hiperfect Transfection reagent (Qiagen). After 72 h, total RNA was extracted and treated with DNase I. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA using miScript Reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) or Superscript III with random primer.

Transfections of the Dicer Targeting shRNA Expression Vector

To suppress Dicer expression, a short hairpin expression vector was used. Using BLOCK-iT RNAi Designer (Invitrogen), complementary DNA oligos were designed. For construction of Dicer shRNA plasmids, sense (5′-CACCGCAGCTCTGGATCATAATACCCGAAGGTATTATGATCCAGAGCTGC-3′) and antisense (5′-AAAAGCAGCTCTGGATCATAATACCTTCGGGTATTATGATCCAGAGCTGC-3′) strand oligos were synthesized. For construction of LacZ2.1 Control, sense (5′-CACCAAATCGCTGATTTGTGTAGTCGGAGACGACTACACAAATCAGCGA-3′) and antisense (5′-AAAATCGCTGATTTGTGTAGTCGT CTCCGACTA CACAAATCAGCGATTT-3′) strand oligos were synthesized. To generate a double-stranded DNA, these oligos were annealed and cloned into pENTER/H1/TO vector (Invitrogen). C666.1 or Mutu III cells (1 × 106) were transfected with 1 μg of vector DNA using CUY21Pro-Vitro (NEPA GENE., Co Ltd, Ichikawa, Japan). After 48 h, total RNA was extracted and treated with DNase I. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA using the miScript reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) or Superscript III with random primers. Transfection efficacy monitored by co-transfection of ptdTomato-C1 vector (Clontech) was ∼70–80%.

Induction of Viral miRNA Expression in HEK293T Cells

The pri-miR-BART6 sequences were PCR-amplified using genomic DNA extracted from GM607 cells and a set of primers, LentiBART6FW (5′-GCCTCGAGTGACCTTGTTGGTACTTTAAGGTTG-3′) and LentiBART6-UneditedRV (5′-GCGAATTCTGGCCTTGAGTTACTCTAAGGCTA-3′) containing a thymidine residue at the +20 site or LentiBART6-Edited RV (5′-GCGAATTCTGGCCTTGAGTTACTCCAAGGCTA-3′) containing a cytidine residue (edited) at the +20 site. These PCR products were digested with XhoI and EcoRI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and ligated into pTRIPZ vector (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). pTRIPZ-derived lentiviruses were transfected into HEK293T in the presence of puromycin (Sigma). Permanently transfected cell lines were induced for pri-miR-BART6 expression with 2 μg/ml doxycycline (Sigma). Transfection efficiency and expression of pri-miRNA were determined by turboRFP expression. Protein and total RNA were extracted 48 h after DOX induction. Levels of mature miR-BART6-5p were examined by dideoxyoligonucleotide/primer-extension assay.

miRISC Loading Assay

The target probes were 5′-end 32P-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP. 5 fmol of 32P-labeled miR-BART6-5p target RNA (5′-AACCUACUAUGGAUUGGACCAACCUUACCAAG-3′), BART6–3P-unedited target (5′-AACCUAAGCUAAGGCUAGUCCGAUCCCGCCAAG-3′), BART6–3P-edited target (5′-AACCUAGCCAAGGCUAGUCCGAUCCCCGCCAAG-3′), and pre-miR-BART6 RNAs, which had been cleaved from pri-miR-BART6 RNAs with Drosha-DGCR8 and gel-purified, were incubated with FLAG-tagged Ago2-complex made from permanently transfected HEK293 cells in a reaction buffer containing 1 unit/μl RNasin, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 0.1 m NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm DTT, 0.2 mm PMSF, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 3.2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 20 mm creatine phosphate, and 1 units/μl creatine kinase at 37 °C for 90 min as described previously (43, 44). miRISC loading products (32P-labeled cleaved target RNAs) were electrophoresed on a 15% polyacrylamide, 8 m urea gel, and quantified by Typhoon Imager.

RESULTS

A-to-I Editing Sites and Mutations Found in EBV Pri-miRNAs

We examined the primary transcripts of all 23 EBV miRNAs for A-to-I RNA editing in latently EBV-infected human lymphoblastoid GM607, Daudi Burkitt lymphoma, and C666-1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. We found that pri-miR-BHRF1–1, pri-miR-BART6, pri-miR-BART8, and pri-miR-BART16 are edited at specific sites (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. 1A). Although the editing frequencies of pri-miR-BHRF1–1, pri-miR-BART8, and pri-miR-BART16 were relatively low (supplemental Fig. 1B), editing of pri-miR-BART6 in Daudi and GM607 cells at the +20 site reached 50 and 70%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Low levels of editing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs were also detected in C666-1 cells (Fig. 1B). We found that the size of the end loop and the terminal stem of the pri-miR-BART6 of Daudi is smaller than that of GM607 cells (wild-type) due to deletion of three uridine nucleotides (Fig. 1A). The same deletion was detected in C666-1 cells, as reported previously (16).

FIGURE 1.

A-to-I RNA editing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs. A, shown are hairpin structures of pri-miR-BART6. Two different hairpin structures of pri-miR-BART6 (partial), the wild-type from GM607 cells and a mutant found in Daudi Burkitt and C666-1 cells, are shown. The editing site adenosine (+20 site), highlighted in red, is indicated by a number with the 5′ end of the mature miR-BART6–3p sequence counted as +1. The regions to be processed into the mature miRNAs (5p sense and 3p antisense strands) are highlighted in green. Mature miR-BART6-5p and both unedited and edited -3p RNAs are also shown. Three deleted U nucleotides are indicated in black boxes within the wild-type hairpin structure. B, DNA sequencing chromatograms of RT-PCR products derived from GM607, Daudi, and C666-1 pri-miR-BART6 RNAs are shown. The RNA editing site (+20) is detected as an A-to-G change in the cDNA sequencing chromatogram as indicated by red arrows. Three T nucleotides, deleted in pri-miR-BART6 from Daudi and C666-1 cells, are indicated. Editing frequency was estimated as a percentage estimated from the ratio of G peak over the sum of G and A peaks of the sequencing chromatogram. Two separate measurements were done, and identical results were obtained.

Because involvement of enzymatically active ADAR1 and ADAR2 in the RNA editing mechanism has been established (23, 24, 45), we examined the expression of ADAR1 and ADAR2 in GM607, Daudi, and C666-1 cells by Western blotting analysis. Although no ADAR2 was detected, abundant expression of ADAR1 (both interferon-inducible p150 and constitutive p110 isoforms) (46) was found in all three cell lines (supplemental Fig. 2), indicating that ADAR1 is likely to be responsible for editing of pri-miR-BART6. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that ADAR2 may be also able to edit this site.

Processing of Pri-miR-BART6 Is Affected by Editing and Mutation

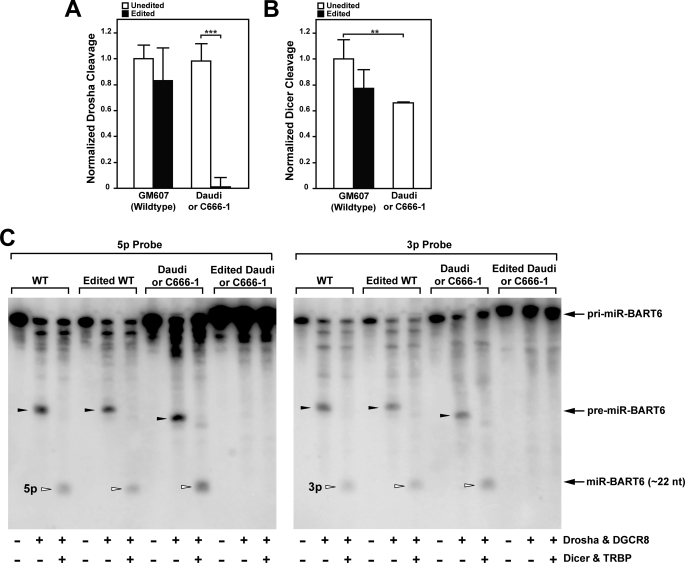

Many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) found in human miRNA genes affect biogenesis and function, suggesting that they may be associated with diseases (47). Sequence variations in several EBV pri-miRNAs have also been reported (16), but the significance of most of these mutations has not been evaluated. We reasoned that editing at the +20 site and the mutations found in Daudi and C666-1 cells may affect the biogenesis of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs. An in vitro pri-miRNA processing assay using recombinant Drosha-DGCR8 and Dicer-TRBP complexes (33, 34, 36) was conducted with uniformly 32P-labeled unedited and “edited” wild-type and Daudi (C666-1) pri-miR-BART6 RNAs, which were prepared by in vitro transcription. The edited pri-miRNAs had an A-to-G substitution at the +20 site. We had previously shown that the miRNA processing machinery recognizes A-to-G substitutions of pri-miRNAs as if they were A-to-I changes (34). The radioactive pri-, pre-, and mature miRNA products were quantitatively analyzed after fractionation on a polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition, nonradioactive pri-miRNAs and their in vitro Dicer and/or Drosha cleavage assay products were also analyzed by Northern blotting using 5p- or 3p strand-specific oligonucleotide probes (Fig. 2C). The efficient conversion of both unedited and edited wild-type (GM607) pri-miR-BART6 to pre-miR-BART6 and mature miR-BART6 was detected, indicating that the editing of wild-type pri-miR-BART6 at the +20 site has no inhibitory effect on Drosha and Dicer cleavage (Fig. 2, A and B). Generation of both 5p and 3p mature miRNAs from unedited and edited wild-type pri-miR-BART6 was confirmed by Northern blotting analysis using strand-specific probes (Fig. 2C). Similarly, unedited Daudi (C666-1) pri-miR-BART6 RNAs were processed to pre- and mature miRNAs, although Dicer cleavage efficiency was reduced to ∼70% of the unedited wild-type level, likely due to the deletion of three U residues (Fig. 2, B and C). However, Drosha cleavage of edited Daudi (C666-1) pri-miR-BART6 was completely blocked (Fig. 2, A and C). Binding of DGCR8 to Daudi (C666-1) pre-miR-BART6 seemed to be unaffected by editing, as seen from a set of electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) gels (supplemental Fig. 3). The nearly identical Kd values (∼5 nm) for binding to unedited and edited pri-miR-BART6 RNAs were estimated from analysis of several EMSA gels. Thus, a combination of the deletion of three U residues and editing at the +20 site appears to inhibit Drosha cleavage of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs.

FIGURE 2.

In vitro processing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs by miRNA processor complexes. A, effect of editing on Drosha cleavage of wild-type and mutant pri-miR-BART6 RNAs was tested with uniformly 32P-labeled pri-miR-BART6 RNAs. The mutant pri-miR-BART6 sequences of Daudi and C666-1 are identical. Thus, it is indicated as Daudi or C666-1. Unedited or edited pri-miR-BART6 RNAs (i.e. containing an A-to-G substitution at the +20 site) was subjected to the Drosha cleavage reaction using Drosha-DGCR8 complex. B, effect of editing on Dicer cleavage is shown. The Drosha-DGCR8 reaction products were subjected to the Dicer cleavage reaction using the Dicer-TRBP complex. A and B, three independent assays were done. Differences analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test: **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). C, Northern blotting analysis of in vitro processed miR-BART6 RNAs is shown. Nonradioactive pri-miR-BART6 RNAs processed in vitro by Drosha-DGCR8 and/or Dicer-TRBP complexes were analyzed by Northern blotting using a 32P-labeled 5p- or 3p-strand specific oligo probe. Representative results for unedited and edited pri-miR-BART6 RNAs of wild-type (GM607) and mutant (Daudi) are shown.

Targeting of Dicer by miR-BART6

The inhibitory effects of mutation and A-to-I editing on processing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs into mature miRNAs may indicate that this viral miRNA plays a role in regulating EBV infection state in Daudi and C666-1 cells. For instance, suppression of miR-BART6 RNAs may be necessary for EBV to remain at a specific state of latency. Certain viral miRNAs have been shown to target genes of the host cell as well as genes of the virus itself (18). Using the DIANA-microT program (48) we, therefore, predicted in silico human and EBV target genes for miR-BART6-5p and miR-BART6–3p (both unedited and edited isoforms). The candidate target genes were pruned by a species conservation filter and also by accepting only genes that have multiple target sites within the 3′-UTRs. We found no strong target gene candidates containing multiple binding sites for miR-BART6-5p or -3p RNAs in the EBV genome. By contrast, the screening identified 14 human strong candidates for miR-BART6-5p and 3 human targets for miR-BART6–3p regardless of whether miR-BART6–3p RNAs were edited or unedited (supplemental Table 1). Because the +20 editing site of miR-BART6–3p is located outside of the seed sequence (Fig. 1A), it was anticipated that editing should not severely affect the selection of target genes.

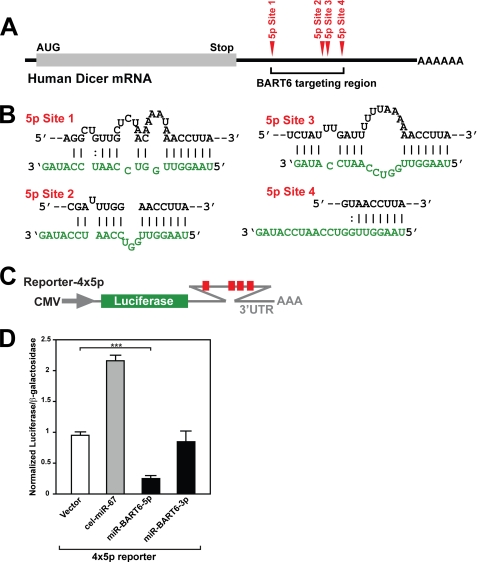

Most interestingly, Dicer was one of the high-score targets for miR-BART6-5p (supplemental Table 1). Because of its importance and global effects on many genes via RNAi, we decided to further investigate the targeting of Dicer by miR-BART6-5p RNAs. Four target binding sites were identified within the ∼1.5-kb region of human Dicer mRNA 3′-UTR (Fig. 3, A and B, and supplemental Experimental Procedures). Although a limited conservation of some 5p sites for elephant (site 1 and site 4) or armadillo (site 1 and site 2) was found, all four sites identified were otherwise unique to the human Dicer 3′-UTR and not evolutionarily conserved even for the chimpanzee Dicer 3′-UTR (data not shown). This is unusual for high score targets, which often have better species conservation, supporting their biological significance. In light of the fact that EBV specifically infects human, it is possible that miR-BART6-5p evolved to target Dicer specifically in human during the establishment of the EBV-host relationship.

FIGURE 3.

Target sites for miR-BART6-5p RNAs identified in the 3′-UTR of human Dicer mRNA. A, the locations of four miR-BART6-5p target sites located within the 3′-UTR of human Dicer mRNA are schematically presented. B, RNA duplex formation between the Dicer 3′-UTR target sites and miR-BART6-5p RNAs are diagrammed. C, shown is a diagram of the luciferase reporter plasmid containing the four 5p strand target sites. D, relative luciferase activities in HeLa cells cotransfected with the reporter vector containing 4 × 5p sites are shown. Two controls, the vector-only transfection, and cotransfection with the unrelated sequence C. elegans miR-67 were conducted. Expression levels of the luciferase reporter gene were normalized by expression levels of a cotransfected β-galactosidase reporter gene. Three independent assays were conducted. The luciferase activities were compared statistically by Mann-Whitney U tests. Significant differences between vector only and miR-BART6-5p or -3p cotransfected experiments are indicated by asterisks; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

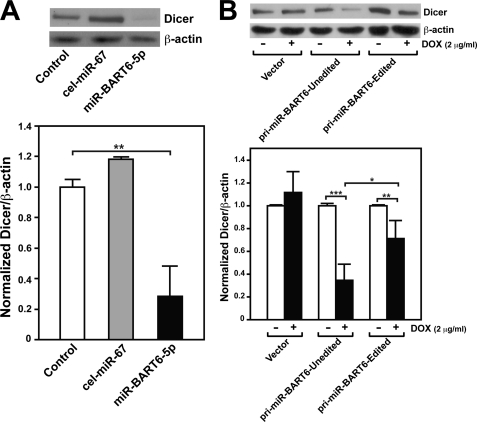

In vitro validation experiments were conducted in HeLa cells (these cells are EBV-negative and, thus, lack pre-existing miR-BART6 RNAs) cotransfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing the Dicer 3′-UTR including the four target sites of miR-BART6-5p (reporter-4 × 5p) (Fig. 3C). The luciferase expression levels were clearly suppressed by miR-BART6-5p (4-fold) but not by miR-BART6–3p in HeLa cells that were cotransfected with the 4 × 5p vector (Fig. 3D). For an unknown reason, our negative control Caenorhabditis elegans miR-67 RNAs unexpectedly increased the luciferase expression (Fig. 3D). This is not due to nonspecific exhaustion of the miRNA-mediated silencing machinery by this control miRNA, as the other sequence-unrelated control miRNA, human miR-376a-5p, had no effect on the luciferase expression (data not shown). The results strongly indicate that the four Dicer mRNA 3′-UTR sites are indeed target sites of miR-BART6-5p RNAs. To validate the targeting of the Dicer mRNA by miR-BART6 RNAs in vivo, we then measured endogenous expression levels of Dicer in HeLa cells. We found a substantial reduction in the Dicer levels (3.5-fold) in HeLa cells transfected with miR-BART6-5p but not with control cel-miR-67 (Fig. 4A), confirming in vivo targeting of Dicer by miR-BART6-5p RNAs.

FIGURE 4.

Repression of Dicer by miR-BART6-5p RNAs. A, Western blot analysis of Dicer expression levels in HeLa cells transfected with miR-BART6-5p RNAs is shown. Two control experiments were conducted; HeLa cells without transfection or transfected with a sequence-unrelated C. elegans miR-67. As a normalization control, β-actin levels were also monitored. A summary graph of normalized Dicer expression levels is also presented. B, shown is a Western blot analysis of Dicer expression in HEK293T cells infected with inducible lentivirus vectors for expression of unedited or edited (A-to-G substitution at the +20 site) pri-miR-BART6 RNAs. Expression of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs was induced with 2 μg/ml doxycycline (DOX). In the presence of doxycycline, the control vector directs the expression of non-silencing verified negative siRNAs (Open Biosystems). A summary graph of normalized Dicer expression levels is also shown. A and B, significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

Suppression of miRISC Loading of miR-BART6-5p RNAs by Editing

To further confirm the in vivo silencing of Dicer by miR-BART6 RNAs, we prepared two tetracycline-inducible pri-miR-BART6 RNA expression constructs in a lentivirus vector system; one expressing unedited wild-type pri-miR-BART6 and the other expressing the edited pri-miR-BART6 containing an A-to-G substitution at the +20 editing site. HEK293 cells (also EBV-negative and, thus, lacking pre-existing miR-BART6-5p RNAs) were infected with the lentiviral constructs and subjected to conditional induction of pri-miR-BART6 and consequent mature miR-BART6 RNAs. Very low editing activities have been reported in HEK293 cells (49), and we confirmed that the pri-miR-BART6 RNAs derived from the unedited pri-miRNA expression construct were barely edited (<5%, data not shown). Dicer levels were reduced by 70% in HEK293 cells infected with the unedited pri-miR-BART6 construct compared with the vector control (Fig. 4B). The reduction in the Dicer levels was also detected in HEK293 cells infected with the edited pri-miR-BART6 construct. However, the extent of suppression was much less, by 25%. This may indicate that editing of the wild-type pri-miR-BART6 RNA has negative effects on the in vivo expression or functions of miR-BART6-5p RNAs, although no difference was noted between unedited and edited pri-miR-BART6 of wild-type (GM607) in in vitro pri-miRNA processing (Fig. 2). No significant difference in miR-BART6-5p RNA levels was detected between HEK293 cells infected with the unedited and edited pri-miR-BART6 expression constructs (supplemental Fig. 4), indicating that the stability and/or turnover of the mature miR-BART6-5p RNAs is unlikely to be affected by editing.

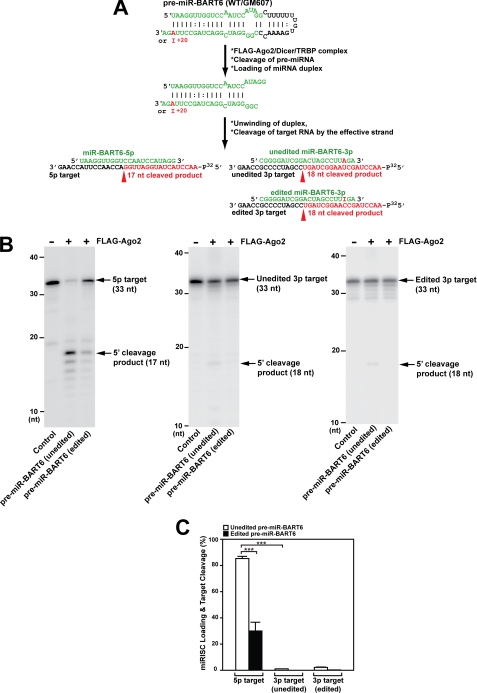

As one of the remaining possibilities, we thought that editing might affect the selection and loading of the “effective” strand onto the miRISC complex (50). We, therefore, examined the assembly of functional miRISC from recombinant FLAG-tagged Ago-2 complexed with Dicer and TRBP and either unedited or edited wild-type pre-miR-BART6 RNAs (Fig. 5A) as described previously (43, 44). We found that formation of the functional miRISC and consequent silencing (cleavage) of the 5p target RNA was indeed much more efficient with unedited pre-miR-BART6 than with edited pre-miR-BART6 (Fig. 5, B and C). Loading of miR-BART6–3p strand RNAs and consequent cleavage of their target RNA were extremely inefficient (Fig. 5, B and C), indicating that miR-BART6-5p is the major effective strand. The cloning frequency for miR-BART6-5p and -3p RNAs in GM607 cells also confirmed that the 5p strand is the effective strand. No sequence variations in the 5′ end sequence of the 5p strand was noted among miR-BART6 clones, indicating that editing at the +20 site does not affect the Drosha cleavage site (data not shown). Together our results clearly demonstrate that editing of the wild-type pri-miR-BART6, although not affecting the processing to pre- and mature miRNAs, inhibits the overall silencing effects of miR-BART6 RNAs. This is the first example of A-to-I editing of a pri-miRNA affecting miRISC loading.

FIGURE 5.

Assembly of functional miRISCs with FLAG-Ago2 and pre-miR-BART6 RNAs. A, a miRISC loading assay of pre-miR-BART6 is shown. Cleavage of the cognate target for miR-BART6-5p or -3p RNAs is schematically shown. The target RNA was 5′ 32P-labeled. B, cleavage of the cognate target product (17 nucleotides) guided by miR-BART6-5p was substantially more efficient with unedited pre-miR-BART6 RNAs than with edited pre-miR-BART6 RNAs (left panel). Cleavage, although very inefficient, of both unedited and edited 3p target was detected only with unedited pre-miR-BART6 (middle and right panels). C, quantitative summary of miRISC loading experiments is presented. The cleavage efficiency was estimated by the ratio of the radioactivity of the correctly cleaved band over that of the uncleaved control band. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests: ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

Suppression of Many miRNAs by miR-BART6-5p

The dramatic reduction in the Dicer expression mediated by miR-BART6-5p (Fig. 4) suggests that it may affect the biogenesis of miRNAs globally. We, therefore, examined the effects of Dicer suppression on expression of other miRNAs by miRNA array analysis. The miRNA levels were examined in HeLa cells with substantially reduced Dicer levels after transfection with miR-BART6-5p RNAs (Fig. 4A). Once again, HeLa cells were used because of the absence of preexisting miR-BART6 RNAs. This study revealed that levels of at least 69 miRNAs were significantly reduced, and 14 of these miRNAs showed more than 2-fold suppression (supplemental Fig. 5A). Synthesis of these miRNAs may be particularly sensitive to the Dicer concentration. Interestingly, the expression of three miRNAs, miR-196b-5p, miR-205–5p, and miR-624–5p (supplemental Fig. 5B), was increased. Although we do not have a confirmed explanation for up-regulation of these three miRNAs, one possibility is that the genes regulating the expression of these miRNAs may be controlled negatively by other miRNAs whose levels are reduced. Our results demonstrate that suppression of Dicer mediated by miR-BART6-5p RNAs affects the expression of a large number of miRNAs.

Modulation of the EBV Latency State by miR-BART6-5p RNAs

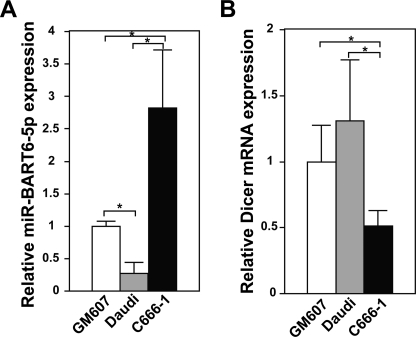

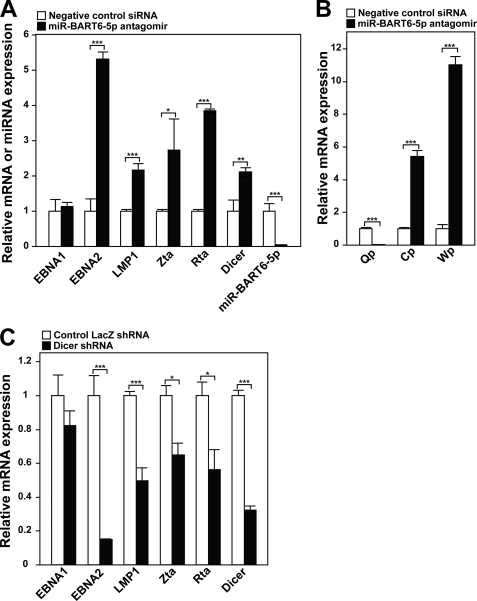

We then asked whether Dicer silencing by miR-BART6-5p RNAs could control the EBV infection state. To examine this possibility, we first examined the relative expression levels of miR-BART6-5p strand RNAs and Dicer among GM607, Daudi, and C666-1 cells by qRT-PCR. Much higher levels of miR-BART6-5p were detected in C666-1 cells, which have much less editing than GM607 and Daudi cells (Fig. 6A). The low levels of miR-BART6-5p in GM607 and Daudi cells are consistent with the high editing rate of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs in these cells (Fig. 1B), which affects their processing (Fig. 2), miRISC formation (Fig. 5C), and consequently the levels of mature miR-BART6-5p RNA. As expected, Dicer levels were lowest in C666-1 cells, in inverse relation to the miR-BART6-5p levels (Fig. 6B). Accordingly, we decided to explore the significance of Dicer repression by miR-BART6-5p RNAs in C666-1 cells. We first attempted to antagonize the miR-BART6-5p RNAs expressed in C666-1 cells by transfection of a miR-BART6-5p antagomir. As expected, the miR-BART6-5p antagomir substantially decreased the miR-BART6-5p level (∼20-fold) with a concomitant increase in the Dicer levels (∼2-fold), indicating that miR-BART6-5p RNAs constantly suppress and maintain Dicer at the reduced levels in C666-1 cells (Fig. 7A). We then examined the relative expression levels of several genes known to be important for either lytic infection or the state of latency: EBNA1, EBNA2, LMP1, Zta, and Rta (12, 13). EBNA1 is detected in type I, II, and III latency, whereas EBNA2 and LMP1 are usually detected in type III latency (12, 13). EBNA2 is essential for the transformation of B lymphocytes and plays a central role in type III latency by up-regulating promoters of all latent EBV genes. Deficiency of the EBNA2 expression is known in type I and II latency (12, 13). A weak expression of LMP1 in type II latency and its deficiency in type I latency have been reported (12, 13). By contrast, Zta and Rta are essential for the initiation of the lytic EBV infection cycle (12, 13). By antagonizing miR-BART6-5p, Zta and Rta increased by 2–3-fold, indicating that miR-BART6-5p keeps these gene products under control. Furthermore, we noticed substantial up-regulation of EBNA2 oncogene expression (∼5-fold) and LMP1 (∼2-fold) by suppression of miR-BART6-5p RNAs, whereas no effects on EBNA1 were observed (Fig. 7A).

FIGURE 6.

Relative expression levels of miR-BART6-5p and Dicer in different cell lines. A, miR-BART6-5p RNA levels were examined by qRT-PCR and normalized to β-actin mRNA level. Three independent assays were done. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. *, p < 0.05. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). B, Dicer mRNA levels were monitored by qRT-PCR and normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. Three independent assays were performed. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. *, p < 0.05. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

FIGURE 7.

Control of viral genes critical for the state of latency and lytic viral replication. A, up-regulation of EBV genes critical for latency and viral replication by the miR-BART6-5p antagomir is shown. Expression of select viral genes including miR-BART6-5p in C666-1 cells transfected with the miR-BART6-5p antagomir or control (sequence unrelated Qiagen AllStars Negative Control siRNA) was examined by qRT-PCR. Three independent assays were done. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). B, shown are changes induced by the miR-BART6-5p antagomir in the viral promoters Qp, specific for the type I and type II latency, and Cp and Wp, specific for the type III latency. Transcripts initiated from Qp, Cp, and Wp were determined by qRT-PCR and compared with β-actin transcripts. Three independent assays were done. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). C, repression of EBV genes after Dicer knock-down by shRNA. Expression of viral genes in C666-1 cells transfected with the Dicer targeting shRNA expression plasmid or control vector containing shRNA against LacZ was monitored by qRT-PCR. Three independent assays were conducted. Significant differences were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. *, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

The activities of the three viral promoters Cp, Wp, and Qp were also monitored (Fig. 7B). Transcription from Cp and Wp is characteristic of type III latency (51), whereas the Qp promoter is used in EBV-infected cells undergoing type I or II latency (52, 53). We used qRT-PCR primers specific for RNAs initiating at Wp, Cp, or Qp (54). Significant up-regulation of type III latency-specific Cp and Wp promoter activities (5.4- and 11-fold, respectively) were detected in C666-1 cells transfected with miR-BART6-5p antagomir. On the other hand, Qp promoter activities associated with type I and type II latency were completely abolished; that is, not detectable in comparison to control.

We then attempted to silence Dicer directly by transfecting a Dicer targeting short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression vector in C666-1 cells (Fig. 7C). This reduced Dicer levels by ∼70%, indicating the efficiency of this Dicer targeting siRNA expression vector. As expected, changes in the marker genes were completely opposite to those noted in C666-1 cells transfected with the miR-BART6-5p antagomir; that is, an ∼7-fold reduction in the EBNA2 expression as well as substantial down-regulation for LMP1, Zta, and Rta (Fig. 7C), further confirming that control of these critical viral genes by miR-BART6-5p is mediated directly via its silencing effects on Dicer.

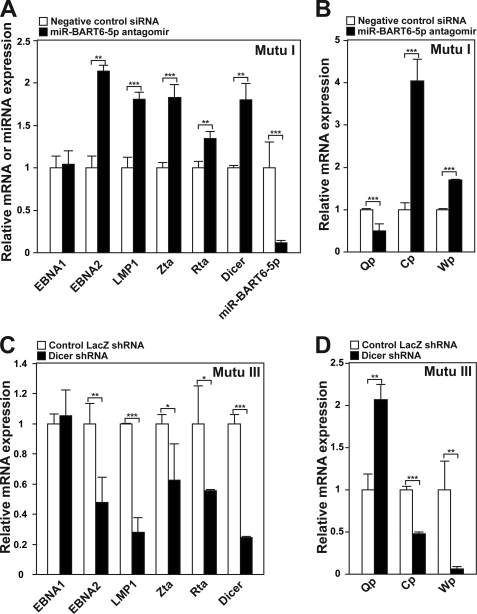

Finally, we examined genetically identical pairs of Burkitt lymphoma Mutu I and Mutu III cell lines, which are in type I and type III latency, respectively, to assess the function of miR-BART6-5p and Dicer silencing in B lymphoma cells (non- nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines). We found that the miR-BART6-5p level is higher in Mutu I than in Mutu III (supplemental Fig. 6A). By contrast, the Dicer level was lower in Mutu I than in Mutu III as expected (supplemental Fig. 6B). Low level A-to-I editing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs was detected only in Mutu III cells, and no mutations were found in the miR-BART6 gene of Mutu I and Mutu III cells (data not shown). Thus, it is currently unknown why higher miR-BART6-5p expression is detected in Mutu I cells as compared with Mutu III cells. We first transfected Mutu I cells with miR-BART6-5p antagomir. As we observed in C666-1 cells, the antagomir effectively reduced miR-BART6-5p levels (∼10-fold) and increased Dicer levels (1.9-fold). Furthermore, significant up-regulation of EBNA2, LMP1, Zta, and Rta, as well as Wp and Cp activation, was detected (Fig. 8, A and B). We then transfected Mutu III cells with the Dicer shRNA expression plasmid, which successfully repressed Dicer levels (∼5-fold). Opposite effects of the miR-BART6-5p antagomir were detected; this, is, suppression of EBNA2, LMP1, Zta, and Rta (Fig. 8C). Up-regulation of Qp activities and down-regulation of Cp and Wp activities were also observed (Fig. 8D).

FIGURE 8.

The effects of miR-BART6-5p and Dicer silencing in B lymphoma cells. A, shown is up-regulation of EBV genes critical for latency III and lytic replication in Mutu I cells transfected with the miR-BART6-5p antagomir or control siRNA. Dicer and miR-BART6-5p levels were also monitored. Three independent qRT-PCR assays were performed. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). B, changes in viral promoter activities were induced in Mutu I cells by the miR-BART6-5p antagomir. Three independent qRT-PCR assays were done. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). C, down-regulation of EBV genes critical for latency III and lytic replication was detected in Mutu III cells transfected with the Dicer targeting shRNA expression plasmid or control vector containing shRNA against LacZ. Three independent qRT-PCR assays were done. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. *, p < 0.05; **, <0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3). D, changes in viral promoter activities were induced in Mutu III cells by Dicer knockdown. Three independent qRT-PCR assays were performed. Significant differences were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U tests. **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars, S.E. (n = 3).

Together, these results suggest that Dicer suppression mediated via miR-BART6-5p RNAs maintains not only the type II latency of C666-1 cells but also the type I latency of Mutu I cells by suppressing lytic replication and also inhibiting transition of these cell lines to type III latency, a more immunoresponse-prone state of the viral infection cycle.

DISCUSSION

Editing Frequency of EBV miRNAs

A-to-I editing of a viral miRNA, KSHV-miR-K12-10 was first implicated because of identification of many cDNA clones corresponding to KSHV-miR-K12-10 RNAs containing an A-to-G substitution compared with the genomic sequence (55). Additional studies conducted more recently confirmed that this is indeed due to A-to-I editing at this site of the viral transcript harboring KSHV-miR-K12-10 by ADAR1 (56). Interestingly, the transcript could be processed into the viral miRNA as well as the mRNA coding for Kaposin A. A-to-I editing and consequent recoding of Kaposin A reduced its transforming activity (56). However, the significance of A-to-I editing of KSHV-miR-K12-10 RNAs remains unknown.

Apart from these reports on KSHV-miR-K12-10 RNAs, there has been no additional report on A-to-I editing of viral miRNAs. In this study we examined EBV miRNAs for A-to-I RNA editing in GM607 B lymphoblastoid cells, Daudi Burkitt lymphoma cells, and C666-1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. We found that primary transcripts of four miRNAs, miR-BHRF1-I, miR-BART6, miR-BART8, and miR-BART16, undergo editing at specific sites. In view of ∼20% of human miRNAs being subject to A-to-I editing (33), our findings of editing of 4 of 23 EBV miRNAs indicate that both cellular and viral miRNAs are subject to editing at about the same frequency. Among four EBV pri-miRNAs, we focused on pri-miR-BART6, which is highly edited at the +20 site of the 3p strand side of the hairpin dsRNA structure.

Suppression of miR-BART6 Expression and miRISC Assembly by A-to-I Editing

We have shown previously that A-to-I editing of pri-miRNAs can suppress their processing to pre-miRNAs by inhibiting Drosha cleavage in the nucleus (34) or suppress processing of pre-miRNAs to mature miRNAs by inhibiting Dicer cleavage in the cytoplasm (35). Furthermore, in some cases A-to-I editing of pri-miRNAs resulted in expression of miRNAs with an altered (edited) seed sequence and consequent silencing of a set of genes different from those targeted by the unedited version miRNAs (36).

In vitro pri-miR-BART6 processing studies revealed that a combination of A-to-I editing at the +20 site, and the three-U-residue deletion mutation, as observed in Daudi Burkitt lymphoma and C666-1 nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, blocks the Drosha cleavage step completely. Editing of wild-type pri-miR-BART6 RNAs did not affect their processing. However, loading of miR-BART6-5p onto the functionally active miRISC was substantially inhibited by A-to-I editing at the +20 site. Editing of pri-miR-BART6 RNAs reported in this study is the first example in which editing suppresses loading of miRNA onto miRISC.

Selection of miR-BART6-5p as an Effective Strand

It has been reported that the relative stabilities of the base pairs at the 5′ ends of the duplex consisting of two miRNA strands determine the selection of the effective strand, which is loaded onto miRISC and acts as the functional miRNA (50, 57). According to these studies, the strand whose 5′ end of the sense-antisense strand duplex is less stable is more frequently selected as the effective strand (50, 57). Interestingly, the miR-BART6 duplex consisting of 5p and 3p strands generated by Dicer cleavage predicts the selection of the 3p strand as the effective strand because of a relatively long fray present in the 5′ end of the 3p strand duplex (Fig. 5A). However, we noted that the 5p strand with the more stable 5′ end of the duplex was much more effectively loaded onto miRISC (Fig. 5B). More recently, major roles played by internal mismatched pairs in the selection of the effective strand for loading onto miRISC and also for unwinding of the duplex and consequent formation of the functional miRISC have been reported (58). According to the studies, central mismatches including G·U wobble pairs at positions 7–11 increase the formation of the miRNA duplex-miRISC, whereas the presence of an additional mismatch within the seed sequence and/or 3′-mid regions at positions 12–15 promotes unwinding of the duplex and formation of the mature functional miRISC containing the single-stranded effective miRNA (58). Interestingly, the miR-BART6-5p effective strand duplex contains these central (G·U at position 8), seed (G·U at position 6), and 3′-mid region (A·C at position 13) mismatched pairs (Fig. 5A), perhaps explaining at least partly why the 5p strand is more effective than the 3p strand.

Although the presence of an internal U·G or U·I wobble pair in place of a U·A Watson-Crick pair decreases the stability of the RNA duplex structure, a terminal U·G or U·I pair confers more stability, although subtle, to the RNA duplex than a U·A pair (59). Thus, replacement of a U·A base pair with U·I (U·G) wobble pair at the 5′ end of the 5p and 3p strand duplex due to editing at the +20 site is likely to increase the stability of the duplex, consistent with our observation that loading of miR-BART6-5p is much more efficient with unedited pre-miR-BART6 than with edited pre-miR-BART6 RNAs. Taken together, A-to-I editing at the +20 site suppresses the miRISC loading due to increased stability of the 5′ end of the 5p strand of the duplex.

Significance of Dicer Repression by miR-BART6 for the Viral Life Cycle

Most significantly, we provided evidence that miR-BART6-5p suppresses Dicer expression through binding to four target sites present within the 3′-UTR of the human Dicer mRNA. Interestingly, these four target sites are not conserved in the mouse or even chimpanzee Dicer mRNA, revealing that miR-BART6-5p RNAs target only human Dicer. In view of the EBV host specificity, i.e. EBV infections occur only in human, silencing of Dicer by miR-BART6-5p might have been established during the course of EBV evolution into a human-specific virus. It may be prudent to discount species conservation, usually used as one of the important parameters for target prediction programs, when target genes of a miRNA from a virus with narrow host range are screened.

Our miRNA array analysis revealed that Dicer suppression by miR-BART6-5p RNAs leads to suppression of many miRNAs. Because Dicer is required for processing of miR-BART6 itself, it is anticipated that a negative feedback loop may be made to tightly control Dicer and miR-BART6 as well as other viral and host cell miRNA levels. It has been reported that EBV infection of primary B cells results in a dramatic down-regulation of host cell miRNA expression, implying the presence of a suppressor of miRNA expression encoded by the virus (60). It was proposed that EBV may manipulate the expression of miRNAs as a major regulatory step in the viral life cycle, whereas host cells may potentially use miRNAs in response to EBV (18, 60). It appears that miR-BART6-5p likely is this viral miRNA suppressor and plays a critical role in the EBV virus life cycle by silencing Dicer and regulating the expression of miRNAs.

A global reduction in miRNA expression has been seen in many cancer cells (61). Suppression of Dicer by let-7 as well as by miR-103/107 and the consequent global reduction of miRNA synthesis have been reported (62–65). The cell proliferation rate is repressed by let-7, and it is proposed that let-7 acts as a master regulator of cell proliferation (66). Promotion of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis is controlled by miR-103/107 that down-regulates Dicer and consequently miR-200 (65). It appears that EBV has acquired miR-BART6 to mimic the powerful strategy of let-7 or miR-103/107 to down-regulate host cell miRNA production, which may be necessary to respond to host immune response and help EBV to stay in a specific state of latency and not initiate lytic viral replication. Suppression of miR-BART6-5p by antagomir indeed resulted in activation of EBNA2, LMP1, Zta, and Rta genes, critical for transition to type III latency or lytic replication, in Mutu I and C666-1 cells usually remaining in the less immune reactive type I and type II latency, respectively. In addition, the type III latency-specific Cp and Wp promoter activities were dramatically activated by miR-BART6-5p antagomir, whereas the type I and type II latency-specific Qp promoter activities were suppressed by the antagomir. We currently have no explanation how these promoter activities are up- or down-regulated. Involvement of B-cell-specific factors that activate the Wp promoter has been reported (67). On the other hand, many factors including E2F1, Rb, and LSD1 histone demethylase have been suggested to control the Cp promoter activities (68). Reduction of Dicer and consequent suppression of specific miRNAs that control these factors may be one possible mechanism to affect different viral promoter activities.

In conclusion, our results suggest the important roles played by EBV miR-BART6 RNAs in the regulation of viral replication and latency. Naturally occurring pri-miR-BART6 mutation and editing may be an adaptive selection to counteract the miR-BART6 function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Valente and W. Deng for providing purified Drosha-DGCR8, Dicer-TRBP, and Ago2-Dicer-TRBP complexes and J. M. Murray and B. Zinshteyn for comments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA010815, GM040536, and HL099342. This work was also supported by the Ellison Medical Foundation (AG-SS-2281-09) and the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health (to K. N.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Experimental Procedures, Table 1, and Figs. 1–6.

- miRNA

- microRNA

- ADAR

- adenosine deaminases acting on RNA

- miRISC

- miRNA-induced silencing complex

- EBV

- Epstein-Barr virus

- qRT

- quantitative real-time.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartel D. P. (2004) Cell 116, 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stefani G., Slack F. J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esquela-Kerscher A., Slack F. J. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 259–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim V. N., Han J., Siomi M. C. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 126–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter J., Jung S., Keller S., Gregory R. I., Diederichs S. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 228–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y., Ahn C., Han J., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J., Lee J., Provost P., Rådmark O., Kim S., Kim V. N. (2003) Nature 425, 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denli A. M., Tops B. B., Plasterk R. H., Ketting R. F., Hannon G. J. (2004) Nature 432, 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory R. I., Yan K. P., Amuthan G., Chendrimada T., Doratotaj B., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. (2004) Nature 432, 235–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund E., Güttinger S., Calado A., Dahlberg J. E., Kutay U. (2004) Science 303, 95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chendrimada T. P., Gregory R. I., Kumaraswamy E., Norman J., Cooch N., Nishikura K., Shiekhattar R. (2005) Nature 436, 740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Förstemann K., Tomari Y., Du T., Vagin V. V., Denli A. M., Bratu D. P., Klattenhoff C., Theurkauf W. E., Zamore P. D. (2005) PLoS Biol. 3, e236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hislop A. D., Taylor G. S., Sauce D., Rickinson A. B. (2007) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 25, 587–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagano J. S., Blaser M., Buendia M. A., Damania B., Khalili K., Raab-Traub N., Roizman B. (2004) Semin. Cancer Biol. 14, 453–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeffer S., Zavolan M., Grässer F. A., Chien M., Russo J. J., Ju J., John B., Enright A. J., Marks D., Sander C., Tuschl T. (2004) Science 304, 734–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai X., Schäfer A., Lu S., Bilello J. P., Desrosiers R. C., Edwards R., Raab-Traub N., Cullen B. R. (2006) PLoS Pathog. 2, e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards R. H., Marquitz A. R., Raab-Traub N. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 9094–9106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grundhoff A., Sullivan C. S., Ganem D. (2006) RNA 12, 733–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cullen B. R. (2009) Nature 457, 421–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barth S., Pfuhl T., Mamiani A., Ehses C., Roemer K., Kremmer E., Jäker C., Höck J., Meister G., Grässer F. A. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 666–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo A. K., To K. F., Lo K. W., Lung R. W., Hui J. W., Liao G., Hayward S. D. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 16164–16169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choy E. Y., Siu K. L., Kok K. H., Lung R. W., Tsang C. M., To K. F., Kwong D. L., Tsao S. W., Jin D. Y. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 2551–2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xia T., O'Hara A., Araujo I., Barreto J., Carvalho E., Sapucaia J. B., Ramos J. C., Luz E., Pedroso C., Manrique M., Toomey N. L., Brites C., Dittmer D. P., Harrington W. J., Jr. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 1436–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bass B. L. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 817–846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishikura K. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 919–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basilio C., Wahba A. J., Lengyel P., Speyer J. F., Ochoa S. (1962) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 48, 613–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jepson J. E., Reenan R. A. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1779, 459–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Athanasiadis A., Rich A., Maas S. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2, e391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blow M., Futreal P. A., Wooster R., Stratton M. R. (2004) Genome Res. 14, 2379–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D. D., Kim T. T., Walsh T., Kobayashi Y., Matise T. C., Buyske S., Gabriel A. (2004) Genome Res. 14, 1719–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levanon E. Y., Eisenberg E., Yelin R., Nemzer S., Hallegger M., Shemesh R., Fligelman Z. Y., Shoshan A., Pollock S. R., Sztybel D., Olshansky M., Rechavi G., Jantsch M. F. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 1001–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blow M. J., Grocock R. J., van Dongen S., Enright A. J., Dicks E., Futreal P. A., Wooster R., Stratton M. R. (2006) Genome Biol. 7, R27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luciano D. J., Mirsky H., Vendetti N. J., Maas S. (2004) RNA 10, 1174–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawahara Y., Megraw M., Kreider E., Iizasa H., Valente L., Hatzigeorgiou A. G., Nishikura K. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 5270–5280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang W., Chendrimada T. P., Wang Q., Higuchi M., Seeburg P. H., Shiekhattar R., Nishikura K. (2006) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawahara Y., Zinshteyn B., Chendrimada T. P., Shiekhattar R., Nishikura K. (2007) EMBO Rep. 8, 763–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawahara Y., Zinshteyn B., Sethupathy P., Iizasa H., Hatzigeorgiou A. G., Nishikura K. (2007) Science 315, 1137–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly G. L., Milner A. E., Tierney R. J., Croom-Carter D. S., Altmann M., Hammerschmidt W., Bell A. I., Rickinson A. B. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 10709–10717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheung S. T., Huang D. P., Hui A. B., Lo K. W., Ko C. W., Tsang Y. S., Wong N., Whitney B. M., Lee J. C. (1999) Int. J. Cancer 83, 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwakiri D., Sheen T. S., Chen J. Y., Huang D. P., Takada K. (2005) Oncogene 24, 1767–1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiss C., Nishikawa J., Takada K., Trivedi P., Klein G., Szekely L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4813–4818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maruo S., Nanbo A., Takada K. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 9977–9982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng A. M., Byrom M. W., Shelton J., Ford L. P. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregory R. I., Chendrimada T. P., Cooch N., Shiekhattar R. (2005) Cell 123, 631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maniataki E., Mourelatos Z. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 2979–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melcher T., Maas S., Herb A., Sprengel R., Seeburg P. H., Higuchi M. (1996) Nature 379, 460–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuel C. E. (2001) Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 778–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun G., Yan J., Noltner K., Feng J., Li H., Sarkis D. A., Sommer S. S., Rossi J. J. (2009) RNA 15, 1640–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maragkakis M., Reczko M., Simossis V. A., Alexiou P., Papadopoulos G. L., Dalamagas T., Giannopoulos G., Goumas G., Koukis E., Kourtis K., Vergoulis T., Koziris N., Sellis T., Tsanakas P., Hatzigeorgiou A. G. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W273–W276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dabiri G. A., Lai F., Drakas R. A., Nishikura K. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 34–45 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khvorova A., Reynolds A., Jayasena S. D. (2003) Cell 115, 209–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearson G. R., Luka J., Petti L., Sample J., Birkenbach M., Braun D., Kieff E. (1987) Virology 160, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaefer B. C., Strominger J. L., Speck S. H. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 10565–10569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith P. R., Griffin B. E. (1992) J. Virol. 66, 706–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo B., Wang Y., Wang X. F., Liang H., Yan L. P., Huang B. H., Zhao P. (2005) World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 629–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfeffer S., Sewer A., Lagos-Quintana M., Sheridan R., Sander C., Grässer F. A., van Dyk L. F., Ho C. K., Shuman S., Chien M., Russo J. J., Ju J., Randall G., Lindenbach B. D., Rice C. M., Simon V., Ho D. D., Zavolan M., Tuschl T. (2005) Nat. Methods 2, 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gandy S. Z., Linnstaedt S. D., Muralidhar S., Cashman K. A., Rosenthal L. J., Casey J. L. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 13544–13551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwarz D. S., Hutvágner G., Du T., Xu Z., Aronin N., Zamore P. D. (2003) Cell 115, 199–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kawamata T., Seitz H., Tomari Y. (2009) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 953–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strobel S. A., Cech T. R., Usman N., Beigelman L. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 13824–13835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Godshalk S. E., Bhaduri-McIntosh S., Slack F. J. (2008) Cell Cycle 7, 3595–3600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumar M. S., Lu J., Mercer K. L., Golub T. R., Jacks T. (2007) Nat. Genet. 39, 673–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Forman J. J., Legesse-Miller A., Coller H. A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14879–14884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Selbach M., Schwanhäusser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., Rajewsky N. (2008) Nature 455, 58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tokumaru S., Suzuki M., Yamada H., Nagino M., Takahashi T. (2008) Carcinogenesis 29, 2073–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martello G., Rosato A., Ferrari F., Manfrin A., Cordenonsi M., Dupont S., Enzo E., Guzzardo V., Rondina M., Spruce T., Parenti A. R., Daidone M. G., Bicciato S., Piccolo S. (2010) Cell 141, 1195–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson C. D., Esquela-Kerscher A., Stefani G., Byrom M., Kelnar K., Ovcharenko D., Wilson M., Wang X., Shelton J., Shingara J., Chin L., Brown D., Slack F. J. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 7713–7722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tierney R., Nagra J., Hutchings I., Shannon-Lowe C., Altmann M., Hammerschmidt W., Rickinson A., Bell A. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 10092–10100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tempera I., Lieberman P. M. (2010) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799, 236–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.