Abstract

In the brain, the amyloid β peptide (Aβ) exists extracellularly and inside neurons. The intracellular accumulation of Aβ in Alzheimer's disease brain has been questioned for a long time. However, there is now sufficient strong evidence indicating that accumulation of Aβ inside neurons plays an important role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Intraneuronal Aβ originates from intracellular cleavage of APP and from Aβ internalization from the extracellular milieu. We discuss here the different molecular mechanisms that are responsible for Aβ internalization in neurons and the links between Aβ internalization and neuronal dysfunction and death. A brief description of Aβ uptake by glia is also presented.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of age-related dementia in the elderly. The increase of the average age of the population is causing a significant rise in the number of people afflicted with this devastating disease, and it is predicted that the incidence of AD will approximately triplicate by 2040 [1] if more effective therapeutic strategies are not made available. In order to develop better therapeutic approaches, the molecular pathways leading to the pathological alterations of the disease must be fully understood.

Major neuropathological and neurochemical hallmarks of AD traditionally included the extracellular accumulation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) in brain senile plaques, the intracellular formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of hyperphosphorylated Tau protein, the loss of synapses at specific brain sites, and the degeneration of cholinergic neurons from the basal forebrain [2]. The original amyloid cascade hypothesis had proposed that the key event in AD development is the extracellular accumulation of insoluble, fibrillar Aβ [3–5]. This “extracellular insoluble Aβ toxicity” hypothesis was later modified to acknowledge the role of soluble Aβ oligomers as pathogenic agents. Only more recently the importance of intraneuronal Aβ accumulation in the pathogenesis of AD has been recognized, despite the fact that the original reports showing Aβ accumulation inside neurons are dated more than 20 years ago. The “intraneuronal Aβ hypothesis” does not argue against a role for extracellular Aβ but complements the traditional amyloid cascade hypothesis [6–8].

The intraneuronal pool of Aβ originates from APP cleavage within neurons and from Aβ internalization from the extracellular milieu. Here we focus on the mechanisms that mediate Aβ internalization in neurons and glia, and we discuss the consequences of Aβ uptake by brain cells.

2. Intraneuronal Aβ

Evidence from several immunohistochemical studies suggested the accumulation of intraneuronal Aβ in AD. Yet, the acceptance of this concept was hampered by the fact that in many studies, antibodies that could not distinguish between APP and Aβ inside the neurons were used. This problem and other experimental issues have been addressed in detail elsewhere [9–11]. Despite these initial technical complications, several studies using antibodies specific for Aβ40 and Aβ42 have confirmed the presence of intraneuronal Aβ and suggested a pathophysiological role for this Aβ pool [12–14]. In the past few years several excellent reviews have discussed the evidence available on accumulation of intracellular Aβ in brains of AD patients and animal models of AD and its impacts on pathogenesis of AD, synaptic impairment, and neuronal loss [6, 9, 11, 15–17]. Here we just mention the most salient aspects of intracellular Aβ accumulation without reviewing the evidence exhaustively.

Intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ is one of the earliest pathological events in humans and in animal models of AD. Intraneuronal Aβ42 immunoreactivity precedes both NFT and Aβ plaque deposition [12, 13], and in the triple transgenic mouse model, Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) abnormalities and cognitive dysfunctions correlate with the appearance of intraneuronal Aβ, prior to the occurrence of plaques or tangles [18, 19]. Moreover, when Aβ is removed by immunotherapy, the intracellular pool of Aβ reappears before tau pathology [20]. Importantly, Aβ accumulation within neurons precedes neurodegeneration in nearly all the animal models in which intracellular Aβ and neuronal loss have been reported, and all models in which intracellular accumulation of Aβ was examined and was present showed synaptic dysfunction [21]. Studies in cultured cells also showed accumulation of intracellular Aβ [22–24].

The observation that cortical neurons that accumulate Aβ42 in brains of AD and Down syndrome patients are apoptotic [25, 26] and that microinjections of Aβ42 or cDNA-expressing cytosolic Aβ42 rapidly induce cell death of primary human neurons [27] indicated the importance of intracellular Aβ in neuronal death. In support of this notion, generation of transgenic mice harboring constructs that target Aβ either extracellularly or intracellularly has demonstrated that only intracellular Aβ-producing transgenic mice developed neurodegeneration [28]. Furthermore, a recent quadruple-mutant mouse has shown neuronal loss in association with intracellular accumulation of Aβ [29]. There is also mounting evidence that intracellular Aβ accumulation is associated with neuritic and synaptic pathology [24, 30, 31] and with alterations of synaptic proteins [32]. Besides, the internalization of Aβ antibodies reduced intraneuronal Aβ and protected synapses [33] as well as reversed cognitive impairment [19].

With respect to the specific form of Aβ that accumulates intracellularly, the use of C-terminal-specific antibodies against Aβ40 and Aβ42 in immunocytochemical studies of human brains with AD pathology, indicated that it is Aβ42 the peptide present within neurons [12, 13, 34–38]. Furthermore, using laser capture microdissection of pyramidal neurons in AD brains, Aoki and collaborators showed increased Aβ42 levels and elevated Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in neurons from sporadic as well as from familial cases of AD, whereas Aβ40 levels remained unchanged [39].

An interesting development of the “intracellular Aβ” cascade is the possibility that Aβ plaques would originate from death and destruction of neurons that contained elevated amounts of Aβ [13, 40, 41]. Indeed, the release of Aβ from intracellular stores by dying cells seems responsible for the reduction or loss of intraneuronal Aβ42 immunoreactivity in areas of plaque formation [12]. Recently, a model was presented in which internalized Aβ starts fibrillization in the multivesicular bodies (MVBs) upon spontaneous nucleation or in the presence of fibril seeds, thus penetrating the vesicular membrane causing cell death and releasing amyloid structures into the extracellular space [42].

The contribution of intracellular Aβ to formation of NFTs has also been proposed. The intracellular pool of Aβ associates with tangles [43], and intracellular Aβ may disrupt the cytoskeleton and initiate the formation of aggregated intracellular Tau protein [12]. Contrary to the concept that intracellular Aβ is linked to NFTs, one report found that intracellular Aβ is not a predictor of extracellular Aβ deposition or neurofibrillary degeneration, although in this study mostly an N-truncated form of Aβ was examined [14].

3. Origin of Intraneuronal Aβ

Based on the evidence presented above, it is now well accepted that two pools of Aβ exist in the brain: intracellular and extracellular. Both Aβ pools are important, and a dynamic relationship between them exists [9, 44].

The intraneuronal pool of Aβ has a double origin: slow production from APP inside the neurons and uptake from the extracellular space. These two mechanisms are quite distinct and are regulated differently. Hence, understanding which pathway, if any, is more relevant to AD pathogenesis may help in the identification of potential targets to treat the disease. There is extensive evidence that indicates the production of Aβ42 from APP “in situ” inside the neurons [23, 45–53]. We are not going to discuss this mechanism of intracellular Aβ accumulation, which has been reviewed recently [9, 15].

Several studies favor a mechanism that involves uptake of Aβ from the extracellular pool [13, 37, 54, 55]. This mechanism of internalization occurs selectively in neurons at risk in AD as demonstrated using organotypic hippocampal slice cultures in which Aβ42 gradually accumulates and is retained intact by field CA1, but not by other subdivisions [40, 56]. Moreover, Aβ from the periphery enters the brain if the blood brain barrier is compromised and accumulates in neurons but not in glia [57]. Recent work also favored a mechanism of Aβ uptake from the extracellular pool based on the fact that intracellular Aβ was always accompanied by increased extracellular Aβ, while in subjects without increased extracellular Aβ there was no detection of intracellular Aβ [10].

Aβ uptake from the extracellular space and Aβ generation from APP inside neurons have been linked in what can be considered an autocatalytic vicious cycle or loop. According to this concept, intracellular accumulation of Aβ42 causes pronounced upregulation of newly generated Aβ42 within neurons. Glabe's group has shown that internalization of exogenous Aβ42 by HEK-293 cells overexpressing APP resulted in accumulation of amyloidogenic fragments of APP [58]. The effect was specific since the amount of nonamyloidogenic α-secretase carboxy-terminal fragments was only slightly affected. The accumulation of the amyloidogenic fragments did not result from an increase in APP synthesis, but instead it was due to specific enhancement of peptides stability, possibly by interaction of the fragments with stable Aβ aggregates causing evasion of the normal degradation pathway. Glabe's group also demonstrated that the amyloidogenic fragments can be further cleaved to produce Aβ, further supporting the hypothesis that amyloid accumulation is a process mechanistically related to prion replication [41, 59]. Exogenous Aβ42 might initiate the cycle in the multivesicular bodies or lysosomes, where Aβ42 accumulates [40, 58]. The induction of amyloidogenic APP fragments by Aβ42 was also documented in the field CA1 of hippocampal slices [40], and the accumulation of intracellular Aβ upon Aβ42 uptake was demonstrated in dendrites of primary neurons [60]. Importantly, the Aβ-induced synaptic alterations demonstrated in this last study required amyloidogenic processing of APP. Indeed, the decrease in synaptic proteins caused by extracellular Aβ [32, 61] is reversed when Aβ is provided together with a γ-secretase inhibitor or given to APP knockout neurons [60]. A link between extracellular Aβ-induced neuronal death and APP cleavage has been suggested [60] based on the evidence that extracellular Aβ causes death of wild type neurons but not APP-knock out neurons [62] and that point mutations in the NPXY motif in the C-terminus of APP block Aβ toxicity [63].

4. Aβ Uptake by Neurons

The molecular events involved in neuronal Aβ internalization in AD are unclear. Aβ is internalized by dissociated neurons, neuron-like cells, and other cells in culture [64–71] (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication) and in cultured hippocampal slices [40, 56, 72]. In neurons, as in other cells, several forms of endocytosis exist (reviewed in [73–75]). Clathrin-mediated endocytosis has been considered the major mechanism of Aβ internalization until recently but many other endocytic processes independent of clathrin may mediate Aβ uptake.

4.1. Uptake of Aβ through ApoE Receptors

The first discovered mechanism of clathrin-mediated Aβ endocytosis involved receptors that bind to apolipoprotein E (apoE) and belong to the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR) family. ApoE is a polymorphic protein that transports extracellular cholesterol. We [76] and others [77] have reviewed the role of apoE in AD, including the increased risk of developing AD in individuals who express the apoE4 isoform. ApoE receptors themselves play important roles in processes related to AD such as neuronal signaling, APP trafficking, and Aβ production (reviewed in [78]).

Studies in human brain indicated that intracellular Aβ accumulation in damaged cells correlates with apoE uptake [54], and neurons with marked intracellular Aβ42 immunoreactivity also stain positively for apoE [12]. Furthermore, the presence of one or two apoE4 alleles strongly correlates with an increased accumulation of intraneuronal Aβ [79]. The finding of apoE inside neurons has been taken as evidence of receptor-mediated uptake [80, 81]. In support of this concept, intraneuronal Aβ is significantly decreased in brains of PDAPP mice lacking apoE [82].

From the several receptors that belong to the LDLR family and bind apoE, the evidence available points at the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) as the most important in Aβ uptake. LRP1 is required for Aβ endocytosis in several cell types including cortical neurons from Tg2576 mice [67], glioblastoma [68] and neuroblastoma cells [83], fibroblasts [72], human cerebrovascular cells [69], synaptosomes and dorsal root ganglion cells [84], and brain endothelial cell lines [85]. Moreover, overexpression of the LRP minireceptor mLRP2 enhanced Aβ uptake in PC12 cells [82], and increased extracellular deposition of Aβ (which was considered as indication of reduced internalization, although this is questionable) was detected in mice that have reduced levels of LRP1 due to deficiency of the chaperone receptor-associated protein (RAP) [83].

Binding of apoE to Aβ increases or decreases Aβ endocytosis depending on the cell type and other environmental conditions [84–90]. ApoE4, in particular, seems to cause a switch to a mechanism independent of LRP1, mediated by other receptors, which in the blood-brain barrier seems to be VLDLR [85, 87]. Whether the formation of a complex Aβ-apoE is required for the regulation of Aβ uptake is still unclear. Some studies showed evidence that LRP1 binds and mediates Aβ endocytosis directly (reviewed in [78, 91]), thus apoE would not be required. However, Yamada and colleagues found that Aβ does not interact directly with LRP1 and suggested that a coreceptor might be needed for Aβ internalization [85]. A fragment of apoE increased Aβ uptake without binding Aβ directly or without inducing up-regulation of LRP1 [92]. As apoE, α2-macroglobulin (α2M) has been linked to AD and is a ligand of LRP1. α2M promotes Aβ uptake by cortical neurons [67] and fibroblasts [72] in culture.

4.2. Uptake of Aβ in the Absence of ApoE

We have speculated that Aβ would exist in the brain in equilibrium between a complex with apoE (or other chaperones) and free Aβ (Figure 1). That equilibrium would be affected by the affinity of apoE for Aβ, which is isoform specific. In addition, during AD, especially when soluble Aβ accumulates in the brain parenchyma, the pool of free Aβ would increase. We demonstrated that neurons are able to internalize free Aβ in the absence of apoE [66]. ApoE-free Aβ is endocytosed by a mechanism that does not involve receptors of the LDLR family, since it is insensitive to RAP. Interestingly a similar RAP-independent Aβ uptake mechanism has been previously observed in synaptosomes, although it was interpreted as nonspecific internalization by constitutive membrane endocytosis [84]. In our case however, it occurs selectively in neuronal axons and, albeit it is independent of clathrin it requires dynamin suggesting that it is a regulated mechanism of endocytosis. A common form of clathrin-independent endocytosis that requires dynamin also involves caveolae, but in our studies we found that Aβ endocytosis does not require caveolin [66]. We reached this conclusion not because neurons do not express caveolin, in fact the neurons used in our studies (except those isolated from caveolin null mice) do express caveolin, as demonstrated for many other neurons [93], but neurons seem to lack caveolae. N2A cells internalize Aβ by another clathrin-independent, dynamin-mediated endocytosis that requires RhoA [65] suggesting that Aβ might also use the pathway of the IL2Rβ receptor [74].

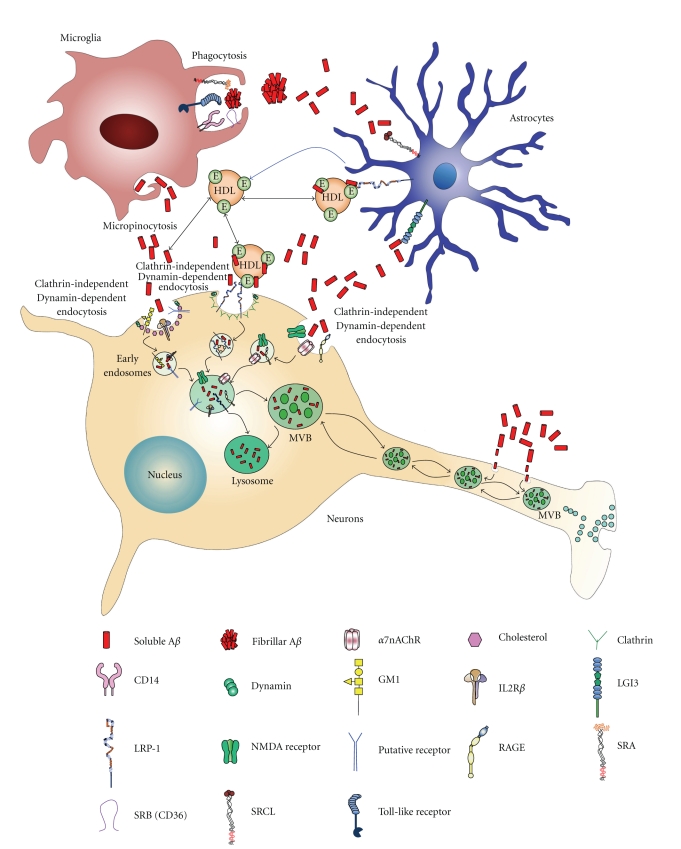

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of Aβ internalization in neurons and glia.

4.3. Lipids and Aβ Endocytosis

Our work implied that at least one mechanism by which neurons internalize apoE-free Aβ involves noncaveolae, GM1-containing rafts [66]. Lipid raft endocytosis occurs in cells with and without caveolae [94]. Aβ uptake by this mechanism is impaired by the simultaneous inhibition of cholesterol and sphingolipid synthesis, and, under these conditions, there is also decreased uptake of cholera toxin subunit B (CTxB). CTxB binds specifically to the ganglioside GM1 and is a known marker for clathrin-independent endocytosis in many cells [73]. Raft-mediated endocytosis is regulated by plasma membrane cholesterol and sphingolipid. Cholesterol regulates several processes that take place in AD including APP cleavage, Aβ production and/or aggregation, and intracellular APP trafficking [95, 96]. Likewise, sphingolipids and gangliosides participate in key events that involve Aβ [96, 97]. Previous work demonstrated that the level of cholesterol at the cell surface regulates Aβ binding and Aβ toxicity [98–100]. None of these studies investigated the role of cholesterol in Aβ internalization. The inhibition of Aβ uptake under low cholesterol and sphingolipid levels could be explained by the disorganization of lipid rafts with the consequent misslocalization of a putative Aβ receptor. Alternatively, Aβ could be internalized in a complex with GM1. Our studies support this last possibility for two reasons; internalized Aβ partially colocalizes with CTxB, and treatment with fumonisin B1 causes decrease of GM1 synthesis [101] and blocks Aβ endocytosis [66]. Our results argue for a concerted role of sphingolipids/gangliosides which is in agreement with extensive evidence and with the model proposed by Dr. Yanagisawa's group [97].

4.4. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors

Other receptors implicated in Aβ internalization are the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which have been linked to AD in several other ways (reviewed in [102, 103]). The most vulnerable neurons in AD appear to be those that abundantly express nAChRs, particularly neurons of the hippocampus and cholinergic projection neurons from the basal forebrain that express the α7nAChR. α7nAChR colocalizes with amyloid plaques and more importantly, α7nAChR regulates calcium homeostasis and acetylcholine release, two key events in cognition and memory. In addition, α7nAChR seems to mediate at least some of the toxic effects of Aβ and Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation.

nAChRs seem to be internalized by endocytosis independent of clathrin and dynamin, in a process that requires the polymerization of actin through activation of Rac-1 [104]. Several studies have suggested the involvement of α7nAchR in the internalization of Aβ42. Work in brains from patients with AD and in neuroblastoma cells expressing α7nAChR suggested that Aβ42 accumulates selectively in neurons that express this receptor as the result of internalization of the Aβ in a complex with α7nAChR [55]. It is unclear if the role of α7nAChR on Aβ uptake depends on the direct binding of Aβ to the nAChR, although Aβ interacts with α7nAChR with high affinity [105, 106]. S 24795, a novel selective α7nAChR partial agonist decreases the interaction between Aβ and α7nAChR in vitro and reduces the intraneuronal Aβ load in organotypic frontal cortical slices [107]. However, in our studies using cultured primary rat neurons, Aβ42 was unable to compete with α-BTx nicotinic receptor binding sites in neuronal membranes, and α-BTx did not affect Aβ42 internalization, despite the expression of α7nAChR, especially in the axons of these neurons [66]. Our results are in agreement with evidence obtained using three different systems namely membrane preparations from rat hippocampus, brain slices and neuroblastoma cells expressing α7nAChR [108]. The difference in the results may be explained by the use of different Aβ preparations and the presence or absence of lipoproteins (and therefore Aβ chaperones) in the different studies. Recently, it was shown that the loss of α7nAChR in Tg2576 mice (A7KO-APP mice) enhances Aβ oligomer accumulation in the extracellular space and increases early cognitive decline and septohippocampal pathology in young animals [109], but improves cognitive deficits and synaptic pathology in aged A7KO-APP mice [110]. It would be interesting to assess the intraneuronal levels of Aβ in the brain of those animals at different ages.

4.5. Integrins and NMDA Receptors

Two receptors present in many synapses are integrins and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. Both receptors regulate clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Several links between Aβ and NMDA receptors have been reported. Aβ-induced neurodegeneration [111, 112], disruption of axonal transport [113], and impairment of synaptic transmission [61] are mediated, at least in part, by NMDA receptors. In agreement, neurons are protected against neuronal degeneration and Aβ toxicity by transient inactivation of NMDA receptors [114, 115]. Memantine is a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist used for the treatment of moderate to severe AD patients. Memantine protects against neuronal degeneration and Aβ toxicity [111, 116]. Importantly, new evidence from Kar's laboratory indicated that the protective role of memantine in cultured cortical neurons are independent of endocytosis since memantine was unable to inhibit Aβ uptake (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication). In other systems, however, the uptake and the effects of Aβ42 on hippocampal neurons were blocked by the NMDA receptor antagonist APV [56]. Moreover, it has been reported that Aβ mediates and promotes NMDA receptor endocytosis possibly via the α7nAChR [61, 117].

The uptake of Aβ by neurons in hippocampal slices is also regulated by integrins. Bi and colleagues found that integrin antagonists enhance Aβ uptake [56]. They propose the following mechanisms of action for integrin antagonists: (i) the increase in peptide availability for uptake, due to disruption of the interaction of Aβ with integrins, which might represent the first step in Aβ extracellular proteolysis, (ii) the facilitation of endocytosis, by reducing the binding of integrins to the extracellular matrix and submembrane cytoskeleton which would slow invagination and endocytosis and (iii) a change in lysosomal proteolysis of Aβ since adhesion receptors can change the rate at which primary lysosomes are formed. Moreover, they suggested that the selectivity in Aβ uptake could be explained by the different types of integrin subunits expressed in each area of the brain or even in specific neurons.

4.6. Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGEs)

The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs) is considered a primary transporter of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier into the brain from the systemic circulation [118], but some evidence exists that RAGE binds monomeric, oligomeric, and even fibrillar Aβ at the surface of neurons [119–121]. Recently, it was reported that RAGE cointernalizes with Aβ and colocalizes with Aβ at the hippocampus of mouse model of AD and that blockade of RAGE decreases Aβ uptake and Aβ toxicity [122].

5. Consequences of Intraneuronal Accumulation of Aβ

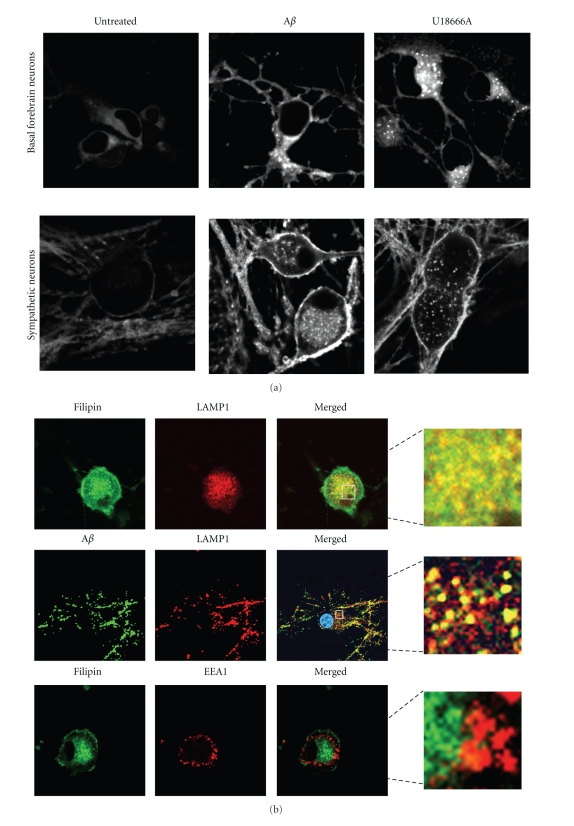

The cellular uptake and degradation of Aβ have been originally considered as mechanisms that reduce the concentration of Aβ in interstitial fluids. However, Aβ42 is degraded poorly, and its accumulation inside neurons has dramatic consequences. Intraneuronal Aβ accumulates within the endosomal/lysosomal system, in vesicles sometimes identified as lysosomes [13, 40, 56, 64, 71, 82, 123] and some others as late endosomes/multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [30, 124–126]. In sympathetic neurons we found that Aβ42 causes sequestration of cholesterol (Figure 2(a)), which colocalizes with LAMP-1 and is the site of Aβ accumulation (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Aβ causes cholesterol sequestration in primary neurons. (a) Rat primary neurons (forebrain and sympathetic) cultured in serum-free medium, were treated for 24 h with 20 μM oligomeric Aβ42 (prepared according to [66]) or with 1.5 μM U18666A, a drug extensively used to induce cholesterol sequestration. Cholesterol was examined by confocal microscopy, using filipin. (b) Neurons were treated as in (a) but fluorescent oligomeric Aβ42 was used. Intracellular localization of cholesterol and Aβ was examined by double indirect immunofluorescence confocal microscopy using LAMP1 as a marker of late endosome/MVBs and EEA1 as a marker of early endosomes.

Aβ42 internalized from the extracellular milieu is quite resistant to degradation possibly due to formation of protease resistant aggregates. Shorter Aβ peptides are degraded and do not accumulate after endocytosis [58, 59, 123, 127]. In one study Aβ42 was shown to be cleared rapidly after delivery to lysosomes, although it previously concentrated and aggregated within the cells, possibly serving as a seed for further Aβ aggregation [71].

Aβ accumulation in lysosomes may cause loss of lysosomal membrane impermeability and leakage of lysosomal content (proteases and cathepsins) causing apoptosis and necrosis [13, 55, 123, 128–130] (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication). The release of lysosomal contents into the cytoplasmic compartments has been considered one of the earliest events in intracellular Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity in vitro [123], and inhibition of lysosomal enzymes protects against Aβ toxicity in cultured cells [131]. ApoE4 potentiates Aβ-induced lysosomal leakage and apoptosis in N2A cells by a mechanism that requires endocytosis by LRP1 [132]. Immunogold studies suggested that the disruption of MVBs could release enough Aβ42 to induce neurotoxicity [30].

An increase in cathepsin D levels secondary to Aβ internalization has been reported in hippocampal slices [56, 133] and cultured cortical neurons (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication). Elevation of cathepsin D levels is a characteristic of AD brains [134–136]; endosome dysfunction occurs early in AD, before amyloid deposition (reviewed in [128]) and is enhanced in persons expressing apoE4 [137]. Abnormal endosomes are also detected in Down syndrome and Niemann-Pick type C, in which Aβ peptide accumulates intracellularly [138].

Endosomal dysfunction, however, might not necessarily involve lysosomal leakage in all cases but could involve defects in intracellular trafficking. MVBs are considered late endosomes, which form by fusion of early endosomes with signaling endosomes and serve as vehicle for the transport of receptors and signaling molecules [139]. MVBs are important vesicles in retrograde transport, and accumulation of Aβ within MVBs would impair their degradative and trafficking functions. MVBs contain inner vesicles with lower pH in the lumen. Aβ interacts with, and partitions into negatively charged membranes [140] and there is evidence that Aβ42 is localized to the outer membrane of the MVBs in brains of patients with AD [30], and is inserted in the membrane of lysosomes in cultured cells that internalized Aβ [130]. The MVBs represent a good location for Aβ aggregation because MVBs are rich in membranes and have low pH [30]. In addition, Aβ accumulation in MVBs membranes will likely disrupt intracellular trafficking as mentioned above.

In neurons, axonal retrograde transport is essential for neuronal life since it secures the delivery of growth factors and/or their survival signals to the soma. This requires the normal function of the endosomal system in axons [141, 142] and will likely be affected by Aβ accumulation in axonal MVBs. We demonstrated that axons are entry points of Aβ and apoE [66, 143] suggesting that accumulation of Aβ in axonal MVBs could impair retrograde transport. Our new evidence suggests that cholesterol accumulation in MVBs could worsen intracellular trafficking in neurons. The impairment of retrograde transport has been proposed to play an important role in degeneration of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in AD [144, 145]. Recent work has shown impairment of BDNF-mediated TrkB retrograde transport in Tg2576 axons and in cultured neurons treated with Aβ [146].

Protein sorting into MVBs is a highly regulated event. One of the mechanisms of MVB sorting is the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) [147]. Aβ inhibits the proteasome [148–150]. Important in the context of this review, part of Aβ internalized by neurons appears in the cytosol, where it could get in contact with the proteasome [149]. LaFerla's group demonstrated an age-dependent proteasome inhibition in the triple transgenic mice model of AD [150]. This inhibition was responsible for tau phosphorylation and was reversed by Aβ immunotherapy. Inhibition of the UPS was responsible for impairment of the MVB sorting pathway in cultured Tg2576 neurons challenged with Aβ [124]. Inhibition of fast axonal transport by Aβ by mechanisms that do not involve MVBs directly has also been reported [151].

6. Neuronal Death Secondary to Aβ Uptake

The role of Aβ in neuronal death and dysfunction has been investigated extensively. The attention has focused mainly on how extracellular Aβ causes neuronal death. On the other hand, whether the intracellular accumulation of Aβ is a cause of neuronal death has been a matter of debate. Some groups consider that intracellular accumulation of Aβ is not responsible for neuronal loss. For instance, the appearance of Aβ immunoreactivity in neurons in infants and during late childhood, adulthood, and normal aging, suggests that this is part of the normal neuronal metabolism [14]. Moreover, Aβ did not produce clear signs of cell death upon infusion in hippocampal slices [40] although in combination with transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) it induced neuronal degeneration in field CA1 [152]. On the other hand, evidence that supports the importance of intracellular Aβ in cell death includes the observations that different mice models of AD show dramatic intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and neuronal cell death that correlates with intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and precedes Aβ deposition [7, 26, 29, 55, 126, 153]. Moreover, the abnormalities and cognitive dysfunctions in several models of AD correlate with the appearance of intraneuronal Aβ, before the appearance of plaques or tangles [18, 19]; markers of apoptosis are present in the subset of neurons that accumulate Aβ in Down syndrome brains [25], and microinjections of Aβ42 or a cDNA-expressing cytosolic Aβ42 rapidly induces cell death of primary human neurons [27]. In addition, treatment of cultured neurons or neuron-like cells with Aβ42 causes Aβ internalization and death [55, 65, 66, 116, 123, 154, 155] (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication).

The evidence above opens the question whether Aβ internalization is required for toxicity. Inhibition of Aβ endocytosis in N2A cells [65], primary cortical neurons (Song, Baker, Todd, and Kar, resubmitted for publication) and sympathetic neurons (Saavedra and Posse de Chaves, unpublished observations) resulted in significantly less intracellular Aβ accumulation and reduced Aβ toxicity. Besides, the selective toxicity of Aβ oligomers versus Aβ fibrils has been explained by the preferential oligomeric Aβ uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis [156]. As indicated above, the endocytic mechanisms used by Aβ in different cells or under different conditions seem to be different, but in all cases the fate of internalized Aβ is similar, being delivered to MVBs or lysosomes.

7. Aβ Internalization by Astrocytes and Microglia

The accumulation of activated astrocytes and microglia close to Aβ deposits suggests that these cells play a role in AD pathology [157–159]. Astrocytes are the most abundant type of cells in the CNS. Upon exposure to Aβ, they become activated and play a neuroprotective role by extending their hypertrophic processes to physically separate the neurons from Aβ fibrils [160]. In addition, activated astrocytes can internalize and degrade Aβ [161], possibly in an attempt to reduce Aβ availability to neurons. Nevertheless, exposure of astrocytes to Aβ could have detrimental consequences. Aβ upregulates inflammatory cytokines and increases the release of nitric oxide in cultured astrocytes [162]. Moreover, Aβ induces not only astrocytic cell death [163], but also neuronal cell death indirectly [164].

Microglia are mononuclear phagocytes of the innate immune system in the CNS. MicrogIia can act as a dual sword in AD pathology. Aβ deposition activates microglia, which release proinflammatory cytokines and other cytotoxic compounds that cause neurodegeneration [165, 166]. Some studies, however, suggested a neuroprotective role of microglia via their ability to internalize and degrade Aβ [167–170].

The evidence of Aβ accumulation in brain glia in AD is contentious. Aβ accumulation in areas with high Aβ deposition has been shown in astrocytes and microglia [171] or astrocytes but not microglia or neurons [172, 173]. Blood-derived Aβ42 is able to cross a compromised blood-brain barrier, is internalized, and accumulates in cortical pyramidal neurons but not in glia [57]. But continuous intracerebral infusion of Aβ in rat brain resulted in Aβ accumulation in astrocytes but not microglia [174]. The lack of intracellular Aβ in microglia cannot be interpreted as microglia being unable to take up Aβ, since it could also reflect that they are highly efficient in degrading it [174]. A theory that opposes this concept establishes that, instead of accumulating Aβ intracellularly, microglia release fibril Aβ contributing to the growth of amyloid plaques [160, 175]. Aβ internalization by microglia in vitro has been shown in several studies [176, 177]. 3D reconstruction of ultrathin sectioning of microglia cells in the vicinity of dense-core amyloid plaque showed that amyloid plaques were exclusively extracellular deposits suggesting that microglia do not internalize fibril Aβ [178]. On the contrary, Bolmont et al. found that plaque-associated microglia internalize a fluorescent dye binding amyloid injected systemically. The intracellular dye particles were positive for Aβ and were not continuous with the amyloid plaque, suggesting true Aβ internalization by microglia [179].

As discussed for neurons, the intracellular pool of Aβ in microglia and astrocytes could be derived from increased endogenous production or increased internalization of exogenous Aβ. Some studies showed that Aβ production in these cells is very low due to reduced APP expression in microglia and reduced beta-secretase activity in astrocytes compared to neurons [180–182]. Nevertheless some stimuli induce expression of APP, beta-secretase, γ-secretase and production of Aβ in astrocytes and microglia [183–185].

7.1. Aβ Internalization by Astrocytes

The involvement of LDLR/LRP1 in Aβ internalization by astrocytes is controversial. The ability of astrocytes to degrade Aβ deposits demonstrated in brains of transgenic PDAPP mice depends on apoE secretion and is blocked by RAP suggesting a mechanism mediated by a member of the LDLR family [186]. Unfortunately, Aβ internalization by astrocytes was not examined in this study [186], and in view that Aβ degradation by astrocytes could be mediated by extracellular matrix metalloproteinases [187], Aβ internalization in this paradigm is not granted. One study showed that Aβ-induced activation of cultured astrocytes is mediated by LRP [188] suggesting that LRP participates in Aβ uptake, although Aβ internalization was not directly examined under these conditions either. Conversely, another study demonstrated that Aβ internalization by astrocytes is not affected by RAP treatment [69] arguing against the involvement of LDLR/LRP1.

The accumulation of fibrillar Aβ in cytoplasmic vesicles of human astrocytes is associated with increased cellular level of apoJ/clusterin [189]. Since apoJ/clusterin binds to fibrillar Aβ [190] and is involved in LRP1- and scavenger-receptor-mediated endocytosis/phagocytosis [191], it was hypothesized that human astrocytes can take up fibril Aβ via apoJ/clusterin-mediated endocytosis [189]. Recently, it has been shown that astrocytes can take up oligomeric Aβ better than fibrillar Aβ [192]. ApoE and apoJ/clusterin reduced oligomeric Aβ positive astrocytes without affecting fibril Aβ uptake [192]. This indicates that Aβ uptake by astrocytes depends on Aβ aggregation status and that oligomeric Aβ internalization by astrocytes could be mediated by the LDLR family.

Scavenger receptors (SRs) are cell surface receptors expressed by diverse cell types that bind to a variety of unrelated ligands [193]. Based on the ability of fucoidan and polyinosinic acid, known ligands for SR, to reduce Aβ binding to and internalization by astrocytes SRs have been recognized as possible mediators of Aβ internalization by astrocytes [164, 194, 195].

Formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) is a G protein-coupled receptor regulating the immune responses [196]. FPRL1 mediates Aβ internalization in astrocytes. Immunostaining of Aβ-treated astrocytes shows colocalization of internalized Aβ and FPRL1. In addition, cotreatment with a FPRL1 agonist (fMLF) or antagonist (WRW4) reduces Aβ internalization. This indicates that Aβ binds to FPRL1 stimulating the complex internalization [197].

Another type of receptors that has shown to be involved in Aβ internalization by astrocytes is leucine-rich glioma inactivated protein 3 (LGI3), a type I transmembrane protein containing leucine rich repeat (LRR) [198, 199]. Aβ induces the expression of the Lib gene in astrocytes, which encodes for LRR-containing type I transmembrane proteins [200]. These LRR containing proteins are thought to mediate protein-protein or protein-matrix interactions [201]. LGI3 colocalizes with Aβ at the plasma membrane and intracellularly in astrocytes suggesting that LGI3 could be playing a role in Aβ internalization [198]. This was supported by the ability of LGI3 downregulation to reduce Aβ internalization by astrocytes [199]. LGI3 is involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in astrocytes and neuronal cell lines [199]. It interacts with flotillin regulating APP intracellular trafficking in neuronal cells [202].

Phagocytosis is another mechanism that could mediate Aβ internalization by astrocytes. Astrocytes that accumulate Aβ in AD brains also have high levels of neuron-specific choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and α7nAChR [163], which suggest that astrocytes are able to internalize Aβ-loaded neurons via phagocytosis. However, the evidence that cytochalasin B, an inhibitor of phagocytosis, does not block Aβ internalization in astrocytes is in conflict with this notion [203].

7.2. Aβ Internalization by Microglia

With respect to the mechanisms that mediate Aβ uptake in microglia, the evidence suggest that different mechanisms exist for soluble and aggregated Aβ (reviewed in [204]). Soluble Aβ internalization by microglia does not depend on the presence of apoE [205] and is not blocked by RAP treatment [168, 170] excluding the involvement of LDLR/LRP-1. Internalized soluble Aβ does not colocalize with internalized transferrin further excluding clathrin-mediated endocytosis [168]. Moreover, soluble Aβ internalization by microglia is nonsaturable excluding receptor-mediated internalization [168, 170]. Soluble Aβ internalization by microglia has been classified as fluid phase macropinocytosis, a process dependent on cytoskeletal structures. Aβ-containing macropinocytic vesicles fuse with late endosomes and later with lysosomes, where they are degraded [168]. Blocking microglial surface receptors that mediate fibril Aβ internalization do not affect internalization of soluble Aβ [168] confirming that the two mechanisms are different.

Fibril/aggregated Aβ internalization by microglia seems to proceed by receptor-mediated endocytosis and receptor-mediated phagocytosis [177, 206]. The surface receptors involved are Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs). These are the receptors used by the innate immune system to recognize pathogen associated molecular pattern, including SR-type A, CD14, CD47, SR-type B (CD36), α6β1 integrin, and toll-like receptors (TLRs) [177, 206–211]. Microglia take up fibril Aβ into phagosomes, which then enter the endosomal-lysosomal system for degradation [177, 206, 207]. Fibril Aβ internalization by microglia is blocked by the scavenger receptor agonists Ac-LDL or fucoidan, but not by RAP indicating the involvement of scavenger receptors but not LDLR/LPR-1 [177]. Microglia that do not express CD14 have lower ability to take up Aβ [207]. The microglial Aβ cell surface receptor complex, composed of α6β1 integrin, CD47 (integrin-associated protein), and the B-class scavenger receptor CD36 [210], mediates microglial uptake of fibril Aβ via a receptor mediated nonclassical phagocytosis [206]. Activation of toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) increases microglial ability to internalize Aβ [207–209, 212]. TLRs activation increases the expression of G protein-coupled mouse formyl peptide receptor 2 (mFPR2), mouse homologue of FPRL1, in microglia. Increased Aβ uptake by microglia upon TLRs activation was blocked by pertussis toxin PTX, Gαi-protein coupled receptor deactivator, W peptide, mFPR2 agonist, anti-CD14, as well as scavenger receptors ligand. This indicates that mFPR2, CD14 and scavenger receptors work together to increase Aβ internalization by microglia upon TLR activation [208, 209]. In addition, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) was also found to mediate Aβ internalization in microglia [197].

In addition, microglia can internalize fibril Aβ by phagocytosis stimulated by Aβ-antibody complex interaction with Fc-receptor [177, 213] and/or fibril Aβ interaction with the complement system C1q (antibody dependent) or C3b (antibody independent) [204, 214–216].

8. Conclusions

The intracellular accumulation of Aβ has been confirmed, and evidence of Aβ internalization from outside the cells exist. Neurons seem to use different mechanisms than glia to take up Aβ. The existence of phagocytic processes in glia suggests that these cells participate mostly in the clearance of Aβ. More research is required to understand if neurons take up Aβ under physiological conditions and whether this is part of Aβ normal metabolism. Regulated endocytosis is the main process by which neurons internalize Aβ. The participation of a number of receptors suggests that more than one mechanism exists. The challenge ahead is to understand the significance of this diversity in the development and progression of AD.

Acknowledgments

Studies in our laboratory are supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Alzheimer Society of Canada. We thank Dr. Satyabrata Kar for sharing results that have been submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Minati L, Edginton T, Grazia Bruzzone M, Giaccone G. Reviews: current concepts in alzheimer’s disease: a multidisciplinary review. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias. 2009;24(2):95–121. doi: 10.1177/1533317508328602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(2):741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1991;12(10):383–388. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1991;6(4):487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wirths O, Multhaup G, Bayer TA. A modified β-amyloid hypothesis: intraneuronal accumulation of the β-amyloid peptide—the first step of a fatal cascade. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;91(3):513–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouras GK, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH. Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26(9):1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuello AC. Intracellular and extracellular Aβ, a tale of two neuropathologies. Brain Pathology. 2005;15(1):66–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2005.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(7):499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aho L, Pikkarainen M, Hiltunen M, Leinonen V, Alafuzoff I. Immunohistochemical visualization of amyloid-β protein precursor and amyloid-β in extra- and intracellular compartments in the human brain. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;20(4):1015–1028. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouras GK, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Capetillo-Zarate E. Intraneuronal β-amyloid accumulation and synapse pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(5):523–541. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0679-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouras GK, Tsai J, Naslund J, et al. Intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation in human brain. American Journal of Pathology. 2000;156(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64700-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Andrea MR, Nagele RG, Wang HY, Peterson PA, Lee DHS. Evidence that neurones accumulating amyloid can undergo lysis to form amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Histopathology. 2001;38(2):120–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wegiel J, Kuchna I, Nowicki K, et al. Intraneuronal Aβ immunoreactivity is not a predictor of brain amyloidosis-β or neurofibrillary degeneration. Acta Neuropathologica. 2007;113(4):389–402. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayer TA, Wirths O. Intracellular accumulation of amyloid-Beta—a predictor for synaptic dysfunction and neuron loss in Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2010;2(8) doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tampellini D, Gouras GK. Synapses, synaptic activity and intraneuronal abeta in Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience . 2010;2 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuello AC, Canneva F. Impact of intracellular β-amyloid in transgenic animals and cell models. Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2008;5(3-4):146–148. doi: 10.1159/000113686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, et al. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s Disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Aβ and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39(3):409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal Aβ causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45(5):675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oddo S, Billings L, Kesslak JP, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Aβ immunotherapy leads to clearance of early, but not late, hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates via the proteasome. Neuron. 2004;43(3):321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wirths O, Bayer TA. Neuron loss in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;2010 doi: 10.4061/2010/723782. Article ID 723782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skovronsky DM, Doms RW, Lee VMY. Detection of a novel intraneuronal pool of insoluble amyloid β protein that accumulates with time in culture. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;141(4):1031–1039. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenfield JP, Tsai J, Gouras GK, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi network generate distinct populations of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(2):742–747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi RH, Almeida CG, Kearney PF, et al. Oligomerization of Alzheimer’s β-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(14):3592–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5167-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busciglio J, Pelsman A, Wong C, et al. Altered metabolism of the amyloid β precursor protein is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in Down’s syndrome. Neuron. 2002;33(5):677–688. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chui DH, Dobo E, Makifuchi T, et al. Apoptotic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease frequently show intracellular Aβ42 labeling. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2001;3(2):231–239. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, McLaughlin R, Goodyer C, LeBlanc A. Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid β peptide1–42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. Journal of Cell Biology. 2002;156(3):519–529. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaFerla FM, Tinkle BT, Bieberich CJ, Haudenschild CC, Jay G. The Alzheimer’s Aβ peptide induces neurodegeneration and apoptotic cell death in transgenic mice. Nature Genetics. 1995;9(1):21–29. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casas C, Sergeant N, Itier JM, et al. Massive CA1/2 neuronal loss with intraneuronal and N-terminal truncated Aβ accumulation in a novel Alzheimer transgenic model. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;165(4):1289–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63388-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi RH, Milner TA, Li F, et al. Intraneuronal Alzheimer Aβ42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. American Journal of Pathology. 2002;161(5):1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meyer-Luehmann M, Spires-Jones TL, Prada C, et al. Rapid appearance and local toxicity of amyloid-β plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2008;451(7179):720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature06616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almeida CG, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, et al. Beta-amyloid accumulation in APP mutant neurons reduces PSD-95 and GluR1 in synapses. Neurobiology of Disease. 2005;20(2):187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tampellini D, Magrané J, Takahashi RH, et al. Internalized antibodies to the Aβ domain of APP reduce neuronal Aβ and protect against synaptic alterations. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(26):18895–18906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Echeverria V, Cuello AC. Intracellular A-beta amyloid, a sign for worse things to come? Molecular Neurobiology. 2002;26(2-3):299–316. doi: 10.1385/MN:26:2-3:299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gyure KA, Durham R, Stewart WF, Smialek JE, Troncoso JC. Intraneuronal Aβ-amyloid precedes development of amyloid plaques in Down syndrome. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 2001;125(4):489–492. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0489-IAAPDO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Näslund J, Haroutunian V, Mohs R, et al. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid β-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283(12):1571–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohyagi Y, Tsuruta Y, Motomura K, et al. Intraneuronal amyloid β42 enhanced by heating but counteracted by formic acid. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2007;159(1):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tabira T, Chui DH, Kuroda S. Significance of intracellular Abeta42 accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Biosci. 2002;7:a44–49. doi: 10.2741/tabira. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aoki M, Volkmann I, Tjernberg LO, Winblad B, Bogdanovic N. Amyloid β-peptide levels in laser capture microdissected cornu ammonis 1 pyramidal neurons of Alzheimer’s brain. NeuroReport. 2008;19(11):1085–1089. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328302c858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahr BA, Hoffman KB, Yang AJ, Hess US, Glabe CG, Lynch G. Amyloid β protein is internalized selectively by hippocampal field CA1 and causes neurons to accumulate amyloidogenic carboxyterminal fragments of the amyloid precursor protein. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1998;397(1):139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Glabe C. Intracellular mechanisms of amyloid accumulation and pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2001;17(2):137–145. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedrich RP, Tepper K, Rönicke R, et al. Mechanism of amyloid plaque formation suggests an intracellular basis of Aβ pathogenicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(5):1942–1947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904532106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murphy GM, Forno LS, Higgins L, Scardina JM, Eng LF, Cordell B. Development of a monoclonal antibody specific for the COOH-terminal of β- amyloid 1-42 and its immunohistochemical reactivity in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. American Journal of Pathology. 1994;144(5):1082–1088. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Smith IF, Green KN, LaFerla FM. A dynamic relationship between intracellular and extracellular pools of Aβ. American Journal of Pathology. 2006;168(1):184–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin BL, Schrader-Fischer G, Busciglio J, Duke M, Paganetti P, Yankner BA. Intracellular accumulation of β-amyloid in cells expressing the Swedish mutant amyloid precursor protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(45):26727–26730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tienari PJ, Ida N, Ikonen E, et al. Intracellular and secreted Alzheimer β-amyloid species are generated by distinct mechanisms in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(8):4125–4130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner RS, Suzuki N, Chyung ASC, Younkin SG, Lee VM-Y. Amyloids β40 and β42 are generated intracellularly in cultured human neurons and their secretion increases with maturation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(15):8966–8970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia W, Zhang J, Ostaszewski BL, et al. Presenilin 1 regulates the processing of β-amyloid precursor protein C- terminal fragments and the generation of amyloid β-protein in endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Biochemistry. 1998;37(47):16465–16471. doi: 10.1021/bi9816195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierrot N, Ghisdal P, Caumont AS, Octave JN. Intraneuronal amyloid-β1-42 production triggered by sustained increase of cytosolic calcium concentration induces neuronal death. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2004;88(5):1140–1150. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nathalie P, Jean-Noël O. Processing of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid peptide neurotoxicity. Current Alzheimer Research. 2008;5(2):92–99. doi: 10.2174/156720508783954721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soriano S, Chyung ASC, Chen X, Stokin GB, Lee VMY, Koo EH. Expression of β-amyloid precursor protein-CD3γ chimeras to demonstrate the selective generation of amyloid/α and amyloid β peptides within secretory and endocytic compartments. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(45):32295–32300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimura N, Yanagisawa K, Terao K, et al. Age-related changes of intracellular Aβ in cynomolgus monkey brains. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2005;31(2):170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wild-Bode C, Yamazaki T, Capell A, et al. Intracellular generation and accumulation of amyloid β-peptide terminating at amino acid 42. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(26):16085–16088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaFerla FM, Troncoso JC, Strickland DK, Kawas CH, Jay G. Neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease correlates with apoE uptake and intracellular Aβ stabilization. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100(2):310–320. doi: 10.1172/JCI119536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagele RG, D’Andrea MR, Anderson WJ, Wang HY. Intracellular accumulation of β-amyloid in neurons is facilitated by the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;110(2):199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bi X, Gall CM, Zhou J, Lynch G. Uptake and pathogenic effects of amyloid beta peptide 1-42 are enhanced by integrin antagonists and blocked by NMDA receptor antagonists. Neuroscience. 2002;112(4):827–840. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00132-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clifford PM, Zarrabi S, Siu G, et al. Aβ peptides can enter the brain through a defective blood-brain barrier and bind selectively to neurons. Brain Research. 2007;1142(1):223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang AJ, Knauer M, Burdick DA, Glabe C. Intracellular Aβ1–42 aggregates stimulate the accumulation of stable, insoluble amyloidogenic fragments of the amyloid precursor protein in transfected cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(24):14786–14792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang AJ, Chandswangbhuvana D, Shu T, Henschen A, Glabe CG. Intracellular accumulation of insoluble, newly synthesized Aβn-42 in amyloid precursor protein-transfected cells that have been treated with Aβ1–42. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(29):20650–20656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tampellini D, Rahman N, Gallo EF, et al. Synaptic activity reduces intraneuronal Aβ, promotes APP transport to synapses, and protects against Aβ-related synaptic alterations. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(31):9704–9713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2292-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, et al. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-β. Nature Neuroscience. 2005;8(8):1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lorenzo A, Yuan M, Zhang Z, et al. Amyloid β interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3(5):460–464. doi: 10.1038/74833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaked GM, Kummer MP, Lu DC, Galvan V, Bredesen DE, Koo EH. Abeta induces cell death by direct interaction with its cognate extracellular domain on APP (APP 597–624) FASEB Journal. 2006;20(8):1254–1256. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5032fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Knauer MF, Glabe CG. Preferential adsorption, internalization and resistance to degradation of the major isoform of the Alzheimer’s amyloid peptide, A β1–42, in differentiated PC12 cells. Brain Research. 1997;746(1-2):275–284. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu C, Nwabuisi-Heath E, Laxton K, Ladu MJ. Endocytic pathways mediating oligomeric Aβ42 neurotoxicity. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2010;5(1, article 19) doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saavedra L, Mohamed A, Ma V, Kar S, De Chaves EP. Internalization of β-amyloid peptide by primary neurons in the absence of apolipoprotein E. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(49):35722–35732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qiu Z, Strickland DK, Hyman BT, Rebeck GW. α-macroglobulin enhances the clearance of endogenous soluble β- amyloid peptide via low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein in cortical neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;73(4):1393–1398. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0731393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Narita M, Holtzman DM, Schwartz AL, Bu G. α-macroglobulin complexes with and mediates the endocytosis of β- amyloid peptide via cell surface low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;69(5):1904–1911. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69051904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wilhelmus MMM, Otte-Höller I, van Triel JJJ, et al. Lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 mediates amyloid-β-mediated cell death of cerebrovascular cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2007;171(6):1989–1999. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ida N, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Rapid cellular uptake of Alzheimer amyloid βA4 peptide by cultured human neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Letters. 1996;394(2):174–178. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00948-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hu X, Crick SL, Bu G, Frieden C, Pappu RV, Lee JM. Amyloid seeds formed by cellular uptake, concentration, and aggregation of the amyloid-beta peptide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;106(48):20324–20329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911281106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang DE, Pietrzik CU, Baum L, et al. Modulation of amyloid β-protein clearance and Alzheimer’s disease susceptibility by the LDL receptor-related protein pathway. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;106(9):1159–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayor S, Pagano RE. Pathways of clathrin-independent endocytosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(8):603–612. doi: 10.1038/nrm2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumari S, Mg S, Mayor S. Endocytosis unplugged: multiple ways to enter the cell. Cell Research. 2010;20(3):256–275. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.de Chaves EP, Narayanaswami V. Apolipoprotein E and cholesterol in aging and disease in the brain. Future Lipidology. 2008;3(5):505–530. doi: 10.2217/17460875.3.5.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63(3):287–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bu G. Apolipoprotein e and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathways, pathogenesis and therapy. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10(5):333–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Christensen DZ, Schneider-Axmann T, Lucassen PJ, Bayer TA, Wirths O. Accumulation of intraneuronal Aβ correlates with ApoE4 genotype. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(5):555–566. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0666-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Han SH, Hulette C, Saunders AM, et al. Apolipoprotein E is present in hippocampal neurons without neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease and in age-matched controls. Experimental Neurology. 1994;128(1):13–26. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han SH, Einstein G, Weisgraber KH, et al. Apolipoprotein E is localized to the cytoplasm of human cortical neurons: a light and electron microscopic study. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 1994;53(5):535–544. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zerbinatti CV, Wahrle SE, Kim H, et al. Apolipoprotein E and low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein facilitate intraneuronal Aβ42 accumulation in amyloid model mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(47):36180–36186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Van Uden E, Mallory M, Veinbergs I, Alford M, Rockenstein E, Masliah E. Increased extracellular amyloid deposition and neurodegeneration in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice deficient in receptor-associated protein. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(21):9298–9304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09298.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gylys KH, Fein JA, Tan AM, Cole GM. Apolipoprotein E enhances uptake of soluble but not aggregated amyloid-β protein into synaptic terminals. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;84(6):1442–1451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yamada K, Hashimoto T, Yabuki C, et al. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 mediates uptake of amyloid β peptides in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(50):34554–34562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801487200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamauchi K, Tozuka M, Hidaka H, Nakabayashi T, Sugano M, Katsuyama T. Isoform-specific effect of apolipoprotein E on endocytosis of β-amyloid in cultures of neuroblastoma cells. Annals of Clinical and Laboratory Science. 2002;32(1):65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, et al. apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid β peptide clearance from mouse brain. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(12):4002–4013. doi: 10.1172/JCI36663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beffert U, Aumont N, Dea D, Lussier-Cacan S, Davignon J, Poirier J. β-amyloid peptides increase the binding and internalization of apolipoprotein E to hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1998;70(4):1458–1466. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang DS, Small DH, Seydel U, et al. Apolipoprotein E promotes the binding and uptake of β-amyloid into Chinese hamster ovary cells in an isoform-specific manner. Neuroscience. 1999;90(4):1217–1226. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00561-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Beffert U, Aumont N, Dea D, Lussier-Cacan S, Davignon J, Poirier J. Apolipoprotein E isoform-specific reduction of extracellular amyloid in neuronal cultures. Molecular Brain Research. 1999;68(1-2):181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zlokovic BV, Deane R, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Winkler EA. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1: a serial clearance homeostatic mechanism controlling Alzheimer's amyloid β-peptide elimination from the brain. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(5):1077–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dafnis I, Stratikos E, Tzinia A, Tsilibary EC, Zannis VI, Chroni A. An apolipoprotein E4 fragment can promote intracellular accumulation of amyloid peptide beta 42. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2010;115(4):873–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Head BP, Insel PA. Do caveolins regulate cells by actions outside of caveolae? Trends in Cell Biology. 2007;17(2):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kirkham M, Parton RG. Clathrin-independent endocytosis: new insights into caveolae and non-caveolar lipid raft carriers. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1745(3):273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burns MP, Rebeck GW. Intracellular cholesterol homeostasis and amyloid precursor protein processing. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2010;1801(8):853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fantini J, Yahi N. Molecular insights into amyloid regulation by membrane cholesterol and sphingolipids: common mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 2010;12, article e27 doi: 10.1017/S1462399410001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matsuzaki K, Kato K, Yanagisawa K. Aβ polymerization through interaction with membrane gangliosides. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2010;1801(8):868–877. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Arispe N, Doh M. Plasma membrane cholesterol controls the cytotoxicity of Alzheimer’s disease AβP (1–40) and (1–42) peptides. FASEB Journal. 2002;16(12):1526–1536. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0829com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wakabayashi M, Matsuzaki K. Formation of amyloids by Aβ-(1–42) on NGF-differentiated PC12 cells: roles of gangliosides and cholesterol. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;371(4):924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yip CM, Elton EA, Darabie AA, Morrison MR, Mclaurin J. Cholesterol, a modulator of membrane-associated Aβ-fibrillogenesis and neurotoxicity. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2001;311(4):723–734. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Posse de Chaves EI, Bussière M, Vance DE, Campenot RB, Vance JE. Elevation of ceramide within distal neurites inhibits neurite growth in cultured rat sympathetic neurons. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(5):3028–3035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oddo S, LaFerla FM. The role of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Physiology Paris. 2006;99(2-3):172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2005.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buckingham SD, Jones AK, Brown LA, Sattelle DB. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signalling: roles in alzheimer’s disease and amyloid neuroprotection. Pharmacological Reviews. 2009;61(1):39–61. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.John PAS. Cellular trafficking of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2009;30(6):656–662. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang H-Y, Lee DHS, D'Andrea MR, Peterson PA, Shank RP, Reitz AB. β-Amyloid1–42 binds to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity. Implications for Alzheimer's disease pathology. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(8):5626–5632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang H-Y, Lee DHS, Davis CB, Shank RP. Amyloid peptide Aβ1-42 binds selectively and with picomolar affinity to α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2000;75(3):1155–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wang HY, Bakshi K, Shen C, Frankfurt M, Trocmé-Thibierge C, Morain P. S 24795 limits β-amyloid-α7 nicotinic receptor interaction and reduces Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologies. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Small DH, Maksel D, Kerr ML, et al. The β-amyloid protein of Alzheimer's disease binds to membrane lipids but does not bind to the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;101(6):1527–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hernandez CM, Kayed R, Zheng H, Sweatt JD, Dineley KT. Loss of α7 nicotinic receptors enhances β-amyloid oligomer accumulation, exacerbating early-stage cognitive decline and septohippocampal pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(7):2442–2453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5038-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dziewczapolski G, Glogowski CM, Masliah E, Heinemann SF. Deletion of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene improves cognitive deficits and synaptic pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(27):8805–8815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6159-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Miguel-Hidalgo JJ, Alvarez XA, Cacabelos R, Quack G. Neuroprotection by memantine against neurodegeneration induced by β-amyloid(1-40) Brain Research. 2002;958(1):210–221. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Harkany T, Ábrahám I, Timmerman W, et al. β-Amyloid neurotoxicity is mediated by a glutamate-triggered excitotoxic cascade in rat nucleus basalis. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(8):2735–2745. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Decker H, Lo KY, Unger SM, Ferreira ST, Silverman MA. Amyloid-β peptide oligomers disrupt axonal transport through an NMDA receptor-dependent mechanism that is mediated by glycogen synthase kinase 3β in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(27):9166–9171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1074-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Davis D, Bryant K, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. β-amyloid peptides destabilize calcium homeostasis and render human cortical neurons vulnerable to excitotoxicity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12(2):376–389. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00376.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tremblay R, Chakravarthy B, Hewitt K, et al. Transient NMDA receptor inactivation provides long-term protection cultured cortical neurons from a variety of death signals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20(19):7183–7192. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07183.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Song MS, Rauw G, Baker GB, Kar S. Memantine protects rat cortical cultured neurons against β-amyloid-induced toxicity by attenuating tau phosphorylation. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(10):1989–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kurup P, Zhang Y, Xu J, et al. Aβ-mediated NMDA receptor endocytosis in alzheimer's disease involves ubiquitination of the tyrosine phosphatase STEP61. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(17):5948–5957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0157-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Dearie R, Sagare A, Zlokovic BV. The role of the cell surface LRP and soluble LRP in blood-brain barrier Aβ clearance in Alzheimer's disease. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14(16):1601–1605. doi: 10.2174/138161208784705487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yan SD, Chen XI, Fu J, et al. RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996;382(6593):685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen X, Walker DG, Schmidt AM, Arancio O, Lue LF, Yan SD. RAGE: a potential target for Aβ-mediated cellular perturbation in Alzheimer’s disease. Current Molecular Medicine. 2007;7(8):735–742. doi: 10.2174/156652407783220741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lue LF, Walker DG, Brachova L, et al. Involvement of microglial receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE)in Alzheimer’s disease: identification of a cellular activation mechanism. Experimental Neurology. 2001;171(1):29–45. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Takuma K, Fang F, Zhang W, et al. RAGE-mediated signaling contributes to intraneuronal transport of amyloid-β and neuronal dysfunction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;106(47):20021–20026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905686106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ditaranto K, Tekirian TL, Yang AJ. Lysosomal membrane damage in soluble Aβ-mediated cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Disease. 2001;8(1):19–31. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Almeida CG, Takahashi RH, Gouras GK. β-amyloid accumulation impairs multivesicular body sorting by inhibiting the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(16):4277–4288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5078-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Langui D, Girardot N, El Hachimi KH, et al. Subcellular topography of neuronal Aβ peptide in APPxPS1 transgenic mice. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;165(5):1465–1477. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63405-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Schmitz C, Rutten BPF, Pielen A, et al. Hippocampal neuron loss exceeds amyloid plaque load in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164(4):1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63235-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Knauer MF, Soreghan B, Burdick D, Kosmoski J, Glabe CG. Intracellular accumulation and resistance to degradation of the Alzheimer amyloid A4/β protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(16):7437–7441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nixon RA. Endosome function and dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of Aging. 2005;26(3):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Guicciardi ME, Leist M, Gores GJ. Lysosomes in cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23(16):2881–2890. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Liu RQ, Zhou QH, Ji SR, et al. Membrane localization of β-amyloid 1–42 in lysosomes: a possible mechanism for lysosome labilization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(26):19986–19996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.036798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kane MD, Schwarz RD, Pierre LS, et al. Inhibitors of V-type ATPases, bafilomycin A1 and concanamycin A, protect against β-amyloid-mediated effects on 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72(5):1939–1947. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0721939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]