Abstract

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE, OMIM 152700) is an autoimmune disease characterized by self-reactive antibodies resulting in systemic inflammation and organ failure. TNFAIP3, encoding the ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20, is an established susceptibility locus for SLE. By fine mapping and genomic resequencing in ethnically diverse populations we fully characterized the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype and isolated a novel TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide associated with SLE in subjects of European (P = 1.58 × 10−8; odds ratio (OR) = 1.70) and Korean (P = 8.33 × 10−10; OR = 2.54) ancestry. This variant, located in a region of high conservation and regulatory potential, bound a nuclear protein complex comprised of NF-κB subunits with reduced avidity. Furthermore, compared with the non-risk haplotype, the haplotype carrying this variant resulted in reduced TNFAIP3 mRNA and A20 protein expression. These results establish this TT>A variant as the most likely functional polymorphism responsible for the association between TNFAIP3 and SLE.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha inducible protein 3 (TNFAIP3) encodes the ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20, a key regulator of NF-κB activity downstream of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), toll-like receptor (TLR), interleukin 1 receptor (IL1R) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2)1–4. The importance of A20 in restricting NF-κB has been demonstrated in A20 deficient mice, which develop systemic organ inflammation and death within six weeks of birth2,3 and in mice with B lymphocyte specific A20 deletion which develop lupus-like autoimmunity5. In humans, genetic surveys have suggested a role for TNFAIP3 in susceptibility to complex genetic autoimmune disorders6–8, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)9–12.

Genetic association between variants in TNFAIP3 and SLE suggest that alterations in activity and/or expression of TNFAIP3 encoded A20 influences SLE pathophysiology9–11. Independent genetic associations of SLE and TNFAIP3 in European-ancestry (EA) subjects have been localized to a region 185 kb upstream of TNFAIP3 that was first identified with rheumatoid arthritis6,7, a region 249 kb downstream of TNFAIP3 and a 109 kb haplotype that spans the TNFAIP3 coding region9–11 that includes a suggested causal coding variant in exon 3 (rs2230926 T>G; F127C, RefSeq: NP_006281.1) that reduces the ability of A20 to attenuate NF-κB signaling10. In this report we fully characterize the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype, including the TNFAIP3 coding region, in five ethnically diverse populations and identify a novel functional polymorphism most likely responsible for association with human SLE.

We studied 127 SNPs in the region of TNFAIP3 on 6q23 and 347 ancestry informative markers (AIMs) in five diverse ethnic populations (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1) and evaluated differences in linkage disequilibrium (LD) to narrow the associated DNA segment. After applying quality control (QC) measures and adjusting for admixture within and across populations (Supplementary Table 2), a total of 8,341 independent cases and 7,476 independent controls (Table 1) were analyzed for 113 TNFAIP3 SNPs and 262 ancestry informative markers (AIMs). We also imputed genotypes for SNPs from the 1000 Genomes Project and Phase III HapMap reference panels resulting in a minimum of 274 additional SNPs for each population (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 1.

Sample summary following quality control adjustments.

| Population | Number of Samples | Case | Control | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African-American | 3338 | 1527 | 1811 | 695 | 2643 |

| Asian (Korean) | 2478 (1831) | 1234 (853) | 1244 (978) | 253 (126) | 2225 (1705) |

| European-ancestry | 7427 | 3936 | 3491 | 1495 | 5932 |

| AA-Gullah1 | 275 | 152 | 123 | 33 | 242 |

| Hispanic2 | 2299 | 1492 | 807 | 207 | 2092 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 15817 | 8341 | 7476 | 2683 | 13134 |

recruited from a group of African-American population originating from Sierra Leone with minimal genetic admixture who live along the Sea Islands of the Carolinas;

enriched for Amerindian-European admixture

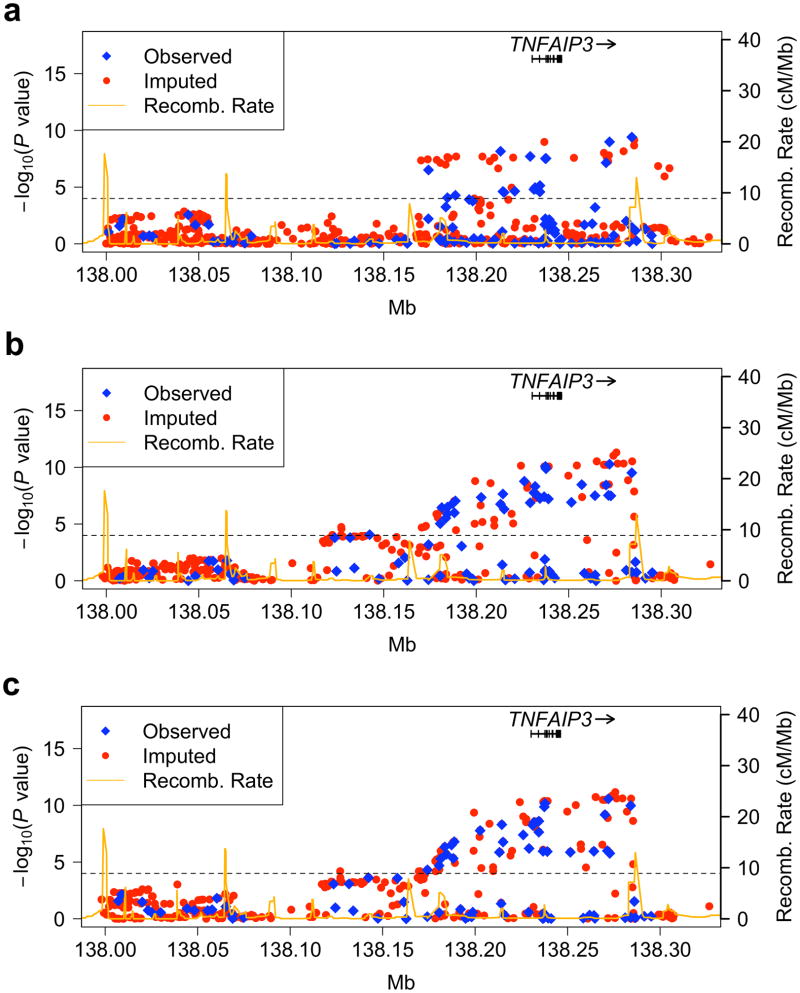

Adjusting for sex and global ancestry in EA and Asian (AS) populations single marker logistic regression analyses of SNPs spanning the TNFAIP3 coding region demonstrated association far below a Bonferroni corrected P < 1 × 10−4 (Figs. 1a and 1b). Peak associations in EA and AS were seen at markers rs6932056 (P = 3.92 × 10−10, OR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.49–2.13) and rs4896303 (P = 6.84 × 10−11, OR = 2.35, 95% CI = 1.82–3.03) 38 kb and 30 kb downstream of TNFAIP3, respectively. Only modest association was seen in the EA population in the previously reported region 185kb upstream of TNFAIP39,10 (Fig. 1a). Korean subjects comprised 71% of our AS cohort and when analyzed independently demonstrated no marked differences in association from the full AS data set (Fig. 1c); thus, subsequent analyses focused only on the more homogeneous Korean subset.

Figure 1.

SNPs in and around the TNFAIP3 gene associated with SLE in European-ancestry (a.), Asian (b.) and Korean (c.) populations. Genotyped SNPs are depicted with blue diamonds and imputed SNPs are shown with red circles. An orange solid line represents recombination rates across the region. The dashed line represents a Bonferroni corrected P < 1 × 10−4. Arrows identify SNPs demonstrating the most significant association results in each population.

In total, 28 SNPs (P < 1 × 10−4) in the both EA and Korean populations defined the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype (Table 2). Interestingly, no convincing evidence for association with TNFAIP3 was seen in the African American (AA), AA-Gullah (AAG) or Hispanic (HS) populations (Supplementary Figs. 1a, 1b, and 1c, respectively).

Table 2.

Association evidence for 28 SNPs in both European-ancestry and Korean populations with P < 1 × 10−4.

| SNP | Position | SNP Statusa | European-ancestry

|

Korean

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allelesb | MAFc | ORd(95% CI) | P valuee | Allelesb | MAFc | ORd(95% CI) | P valuee | |||

| rs2788289 | 138184430 | g | G/A | 0.181 | 1.20(1.09–1.31) | 8.57E-05 | G/A | 0.146 | 1.50(1.25–1.81) | 1.69E-05 |

| rs670369 | 138188741 | g | T/C | 0.180 | 1.20(1.10–1.32) | 5.27E-05 | T/C | 0.133 | 1.60(1.32–1.95) | 2.21E-06 |

| chr6:138203359 | 138203359 | i | G/A | 0.037 | 1.72(1.42–2.08) | 2.03E-08 | G/A | 0.011 | 6.26(2.61–14.99) | 3.91E-05 |

| rs80126770 | 138209776 | i | C/T | 0.037 | 1.72(1.42–2.08) | 2.49E-08 | C/T | 0.010 | 6.91(2.66–17.97) | 7.30E-05 |

| rs9494883 | 138213159 | g | A/G | 0.043 | 1.68(1.41–2.00) | 6.99E-09 | A/G | 0.020 | 2.96(1.77–4.95) | 3.59E-05 |

| rs9494885 | 138214441 | g | A/G | 0.100 | 1.28(1.14–1.44) | 2.43E-05 | A/G | 0.081 | 1.94(1.52–2.48) | 8.96E-08 |

| rs7753873 | 138215115 | g | A/C | 0.100 | 1.28(1.14–1.44) | 2.91E-05 | A/C | 0.091 | 1.72(1.37–2.16) | 2.70E-06 |

| rs7767264 | 138219151 | i | T/G | 0.092 | 1.32(1.17–1.49) | 1.11E-05 | T/G | 0.018 | 3.28(1.86–5.78) | 4.01E-05 |

| rs72063345 | 138219986 | i | T/C | 0.037 | 1.71(1.42–2.07) | 2.49E-08 | T/C | 0.046 | 2.00(1.44–2.8) | 4.57E-05 |

| rs5029924 | 138229191 | g | C/T | 0.048 | 1.61(1.37–1.90) | 1.97E-08 | C/T | 0.020 | 3.02(1.81–5.05) | 2.49E-05 |

| rs5029926 | 138231208 | g | A/G | 0.100 | 1.29(1.15–1.45) | 1.60E-05 | A/G | 0.081 | 1.93(1.51–2.46) | 1.05E-07 |

| rs5029928 | 138231635 | i | C/T | 0.099 | 1.29(1.15–1.45) | 1.65E-05 | C/T | 0.081 | 1.95(1.53–2.48) | 7.84E-08 |

| rs3757173 | 138231847 | g | A/G | 0.099 | 1.30(1.16–1.46) | 1.10E-05 | A/G | 0.080 | 1.95(1.53–2.49) | 9.10E-08 |

| rs5029930 | 138232377 | g | A/C | 0.100 | 1.29(1.15–1.45) | 1.45E-05 | A/C | 0.081 | 1.93(1.51–2.46) | 1.05E-07 |

| rs719149 | 138234438 | g | G/A | 0.097 | 1.29(1.14–1.45) | 2.63E-05 | G/A | 0.079 | 1.87(1.47–2.39) | 4.35E-07 |

| rs719150 | 138234454 | g | A/G | 0.098 | 1.31(1.17–1.48) | 7.27E-06 | A/G | 0.078 | 2.00(1.56–2.57) | 5.89E-08 |

| rs5029937 | 138236844 | i | G/T | 0.042 | 1.76(1.47–2.10) | 1.04E-09 | G/T | 0.065 | 2.36(1.79–3.13) | 1.75E-09 |

| rs5029939 | 138237416 | g | C/G | 0.047 | 1.60(1.36–1.89) | 3.05E-08 | C/G | 0.065 | 2.38(1.80–3.16) | 1.39E-09 |

| rs2230926 | 138237759 | g | T/G | 0.050 | 1.58(1.34–1.86) | 2.98E-08 | T/G | 0.065 | 2.35(1.78–3.11) | 2.11E-09 |

| rs7752903 | 138269057 | i | T/G | 0.040 | 1.71(1.42–2.06) | 9.60E-09 | T/G | 0.064 | 2.41(1.82–3.20) | 1.13E-09 |

| rs9494894 | 138270213 | g | T/C | 0.040 | 1.65(1.37–1.98) | 7.17E-08 | T/C | 0.061 | 2.30(1.72–3.08) | 1.77E-08 |

| rs57427648 | 138270467 | i | G/T | 0.041 | 1.67(1.39–2.00) | 2.19E-08 | G/T | 0.064 | 2.41(1.82–3.20) | 1.13E-09 |

| chr6:138271733 | 138271733 | i | T/A | 0.039 | 1.70(1.41–2.04) | 1.58E-08 | T/A | 0.059 | 2.54(1.89–3.42) | 8.33E-10 |

| rs7749323 | 138272082 | g | G/A | 0.042 | 1.75(1.46–2.09) | 1.03E-09 | G/A | 0.064 | 2.43(1.83–3.22) | 8.33E-10 |

| rs77000060 | 138279682 | i | C/T | 0.039 | 1.72(1.43–2.07) | 6.90E-09 | C/T | 0.064 | 2.43(1.83–3.22) | 8.33E-10 |

| rs6932056 | 138284130 | g | T/C | 0.041 | 1.78(1.49–2.13) | 3.92E-10 | T/C | 0.061 | 2.47(1.85–3.31) | 1.25E-09 |

| rs61117627 | 138285393 | i | G/A | 0.039 | 1.77(1.47–2.13) | 2.14E-09 | G/A | 0.055 | 2.57(1.89–3.50) | 1.98E-09 |

| rs58721818 | 138285432 | i | C/T | 0.040 | 1.79(1.49–2.15) | 7.00E-10 | C/T | 0.011 | 7.87(3.07–20.18) | 1.75E-05 |

SNP Status, genotyped (“g”) or imputed (“i”);

major/minor;

minor allele frequency;

Odds Ratio (OR) was calculated with respect to minor allele;

adjusted for sex and global ancestry estimates.

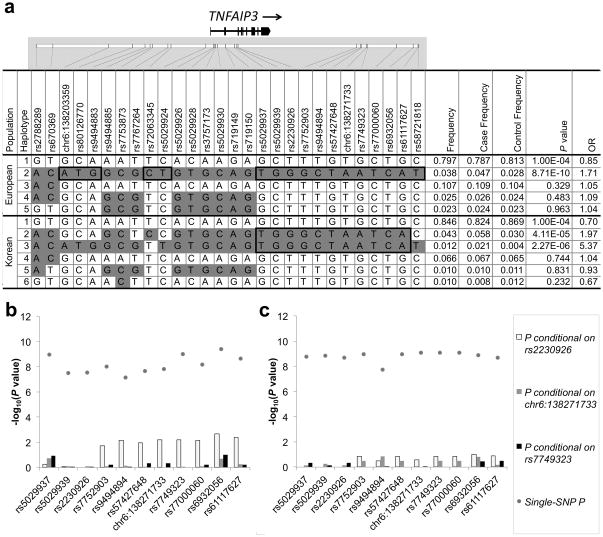

To assess whether differences in the LD structure between EA and Korean populations (see Supplementary Fig. 2) could reduce the size of the TNFAIP3 risk segment, we compared haplotypes (frequency ≥ 1%) formed by the SNPs in Table 2. In EA, a single 101 kb risk haplotype (P = 8.71 × 10−10) was observed (Fig. 2a, EA Haplotype 2). Three segments of this haplotype carry minor alleles absent from the non-risk haplotypes, suggesting they might harbor the causal variant. In Koreans, we observed two primary risk haplotypes with P = 4.11 × 10−5 and P = 2.27 × 10−6 (Fig. 2a, Korean Haplotype 2 and 3, respectively). These two risk haplotypes shared minor alleles not present on the non-risk haplotype from marker rs5029937 to rs61117627 thus reducing the TNFAIP3 risk interval to this 48.5 kb segment.

Figure 2.

Haplotype and conditional association analysis results of the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype. Haplotypes present at a frequency > 1% were compared in the European-ancestry and Korean populations (a.). Alleles in white boxes represent the major allele and those in grey boxes represent the minor allele for each haplotype. Black bold rectangles identify minor alleles that differentiate the SLE risk haplotype from the non-risk haplotype. Conditional association analysis was performed in the European (b.) and Korean (c.) populations for each of the SNPs within the 48.5 kb segment bounded by rs5029937 and rs61117627. We assessed three models: first, conditioning the on F127C coding variant rs2230926 (white bars), then conditioning on the TT>A variant (gray bars) and finally conditioning on rs7749323 (black bars).

Resequencing nine TNFAIP3 risk chromosomes from seven EA carriers (two homozygotes and five heterozygotes) did not identify any additional SNPs not already accounted for in our analyses (Online Methods). However, we did find a novel single base deletion at chromosome 6 position 138,271,732 (hg18) present on all nine risk chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, this deletion polymorphism was located adjacent to SNP chr6:138271733 (P = 1.58 × 10−8, OR = 1.70, 95%CI = 1.41–2.04, MAF = 0.039 in EA and P = 8.33 × 10−10, OR = 2.54, 95%CI = 1.89–3.42, MAF = 0.059 in Koreans), and together they formed a novel TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide (deletion T followed by a T to A transversion) at chromosome 6 position 138,272,732–138,271,733 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

To determine the segment of the risk haplotype that accounted for the largest portion of the association signal, we performed conditional association analysis. Conditioning on SNP chr6:138271733 or its proxy SNP rs7749323 (r2 ≥ 0.97) for both EA and Korean populations reduced the association signal to baseline (Figs. 2b and 2c, respectively). However, conditioning on rs2230926, a coding variant in exon 3 (F127C) and a putative causal variant, revealed residual association in the region 31.2 kb downstream most prominently in EA (Fig. 2b) and to a lesser extent in the Koreans (Fig. 2c). These results suggested that the variant responsible for association with SLE was likely to be located in the 16.3 kb region extending from rs7752903 to rs61117627.

To assess the functional potential of the nine risk variants (8 SNPs and 1 deletion) present on the 16.3 kb TNFAIP3 risk segment defined by our previous analyses we evaluated the region with the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) to determine overlap between variants and genomic regulatory elements (Supplementary Fig. 5a). The TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide is located in a region of high mammalian conservation (17-way vertebrate conservation13), high regulatory potential (7X Regulatory Potential, ESPERR14) and overlap with DNase hypersensitivity and transcription factor binding signals, as well as a region of enhancer activity bearing the H3K27Ac epigenetic mark15 (Supplementary Fig. 5a). A total of eight transcription factors produced CHIP-seq signals in the vicinity of this variant with the strongest signals produced by early B-cell factor (EBF), B-cell CLL/lymphoma 11A (BCL11A) and NF-κB16 (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In contrast, the remaining variants demonstrated substantially less overlap with regulatory elements thus pointing to the TT>A variant as the prime functional variant responsible for association with SLE.

Further evidence supporting the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide was sought by genotyping both AA and AAG cases and controls (Online Methods). Neither of these populations demonstrated SLE association and would therefore not be expected to carry the variants of interest. In all AA samples evaluated (N=2,252), we observed this variant only 23 times (1 copy each in 13 cases and 11 controls) for an overall allele frequency of 0.53%, which approximates that expected due to European admixture (Online Methods). Furthermore, TT>A variant was not detected in any of the AAG (N=243), a population with low European admixture (~3.5%17). We estimate our power to detect an association with the TT>A variant in this AA sample is only 0.8% given a type I error of 0.0001 and an odds ratio of 1.7. These results suggest that the TT>A dinucleotide polymorphism is derived from European and Asian chromosomes and the low allele frequency in African-Americans resulted in our inability to demonstrate association.

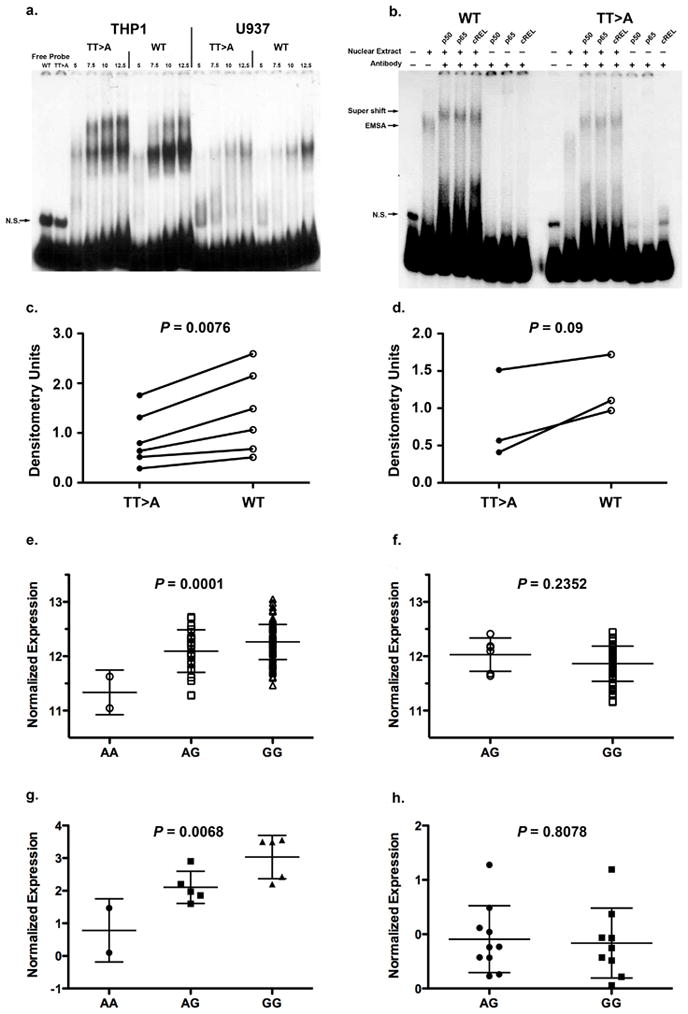

To test functional differences in nuclear protein binding conferred by the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide, oligonucleotide probes containing this variant or wild-type sequences were evaluated using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). In nuclear extracts from independent monocyte cell lines, THP1 and U937, we observed differential intensity of shifted bands (Fig. 3a) suggesting that the TT>A variant was important in mediating nuclear protein binding. Using antibodies specific to subunits of the NF-κB transcription factor (p50, p65, cREL) we demonstrated that NF-κB was a major component of the DNA-nuclear protein complex (Fig. 3b). Densitometric measurement of shifted band intensity from multiple independent experiments demonstrated statistically significant differences between the TT>A and WT cells for the THP-1 extracts at P = 0.0076 (N=6, Fig.3c). U937 extracts also exhibited a difference at the less stringent level of P = 0.09, likely due to the smaller number of observations in U937 cells (N=3, Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Functional characterization of the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide and TNFAIP3 associated risk haplotype. (a.) Shown is a representative EMSA result from six independent experiments for THP1 and three for U937). The first two lanes show free probe for wild type (WT) and TT>A variant followed by increasing amounts of nuclear protein and labeled probes as indicated. A non-specific band is labeled N.S. (b.) Super shift was performed using antibodies specific to NF-κB subunits.. Complexes formed in the presence and absence of antibodies are identified by arrows on the left of the figure.. Densitometric quantification of nuclear protein binding in independent experiments was performed for THP1 cells (c.) and U937 cells (d.) using optimal concentrations of nuclear extract. Expression of TNFAIP3 transcripts were evaluated from CEU, CHB and JPT populations (AA, N=2; AG, N=24; GG, N=115) (e.) and compared to the YRI population (AG, N=6; GG, N=54) (f.) using a one-way ANOVA and unpaired t-test. A20 protein expression from cell lines of European-ancestry subjects (AA, N=2; AG, N=5; GG, N=5) (g.) were compared to African-American subjects (AG, N=10, GG, N=9) (h.) using one-way ANOVA and unpaired t-test, respectively.

Since altered binding of NF-κB to the regulatory region containing the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide could influence TNFAIP3 gene expression we used gene expression data generated from transformed B-cell lines of 201 unrelated HapMap samples18 (ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/genevar) to test this possibility. We pooled the genotypes for SNP rs7749323 from HapMap European (CEU), Chinese (CHB) and Japanese (JPT) subjects since our data confirmed that rs7749323 is a perfect proxy of the TT>A variant in these populations and compared TNFAIP3 mRNA expression to that of the HapMap Yoruba (YRI) samples. These results demonstrated a significant decrease in TNFAIP3 mRNA expression with the number of risk alleles (A) in the combined sample (Fig. 3e, P = 0.0001, one-way ANOVA) compared to the YRI samples (Fig. 3f, P = 0.2352, two-tailed t-test). To confirm these results we evaluated basal A20 expression in an independent set of EBV transformed cell lines by Western blotting. Similar to the mRNA expression results, we found decreased expression of A20 protein as a function of the number of rs7749323 risk alleles in EA subjects (Fig. 3g, P = 0.0068, one-way ANOVA) compared to cell lines from AA subjects (Fig. 3h, P = 0.8078, two-tailed t-test). These results support the hypothesis that regulatory polymorphisms present on the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype, such as the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide, influence A20 expression.

In summary, we have comprehensively characterized the genetic variation present on the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype and have identified a novel TT>A dinucleotide as the best candidate polymorphism responsible for SLE association in subjects of European and Korean ancestry. The lack of significant association in AA, AAG, and HS populations is proportional to the power to detect the European derived TT>A variant present at frequencies consistent with EA admixture (0.53%, unobserved, and 2.9%, respectively). The TT>A dinucleotide variant, 42 kb downstream of the TNFAIP3 promoter, is located in a genomic region of high conservation and regulatory potential and may influence TNFAIP3 expression by altering the binding of transcription factors, one of which is NF-κB, in response to pro-inflammatory signals.

In addition to the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide and the rs2230926 T>G F127C exon 3 coding variant, another TNFAIP3 functional variant was recently reported in SLE through genetic association in 217 AA cases19. This variant, rs5029941 C>T, defines a rare African derived protective haplotype (P=0.027) and encodes an A125V substitution, two amino acid residues from F127C19. Functionally, the A125V polymorphism resulted in significant defects in A20 mediated deubiquitination19. However, our results from a larger set of AA SLE cases (N=1527) failed to support a role for rs5029941 (P=0.223, Supplementary Table 4) in AA SLE susceptibility.

While rare variants may influence the genetic association with TNFAIP3, we are confident that we have captured all common variants (minor allele frequency > 1%) present on the risk haplotype in our analyses with the data supporting the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide as responsible for SLE association. It is possible that this variant may work in concert with the F127C or A125V coding region variants to influence both expression and enzymatic activity of A20, thus producing a more robust functional phenotype. Such a mechanism has been suggested for IRF5, where a complex haplotype is required for SLE risk20.

The location of the TT>A polymorphic dinucleotide in relation to TNFAIP3 suggests that it may be part of a transcriptional modulator perhaps through recruitment of epigenetic DNA modifiers or through direct interaction with the A20 proximal promoter. The precise mechanism for how the TT>A polymorphism would influence expression of TNFAIP3 is uncertain, however, methods designed to detect long-range interactions of transcriptional regulatory elements may provide insight into this process21. Future work will focus on characterizing the protein complex bound to the TT>A polymorphism and mapping the interactions of this genomic region with other regulatory elements in the vicinity of TNFAIP3.

METHODS

Subjects

This study included the following independent cases and controls, respectively (Supplementary Table 1): African-American (1,569/1,893), Asian (1,328/1,348), European-ancestry (4,248/3,818), African-American Gullah (155/131) and Hispanic enriched for the Amerindian-European admixture (1,622/887) populations. The Asians were comprised primarily of Koreans (906 cases and 1012 controls) but also included Chinese, Japanese, Taiwanese and Singaporeans. Cases were defined by meeting at least four of the 1997 ACR revised criteria for the classification of SLE22. Samples were collected from multiple sites and processed at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) under the auspices of the OMRF Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Genotyping and Quality Control

Genotyping was performed on the Illumina iSelect platform at OMRF for 127 SNPs (chromosome 6, 138,001,148 to 138,295,172 bp; NCBI build 36, dbSNP build 126) and 347 genome-wide AIMs23,24 (Supplementary Table 5). Principal components analysis25, using R (Supplementary Fig. 6), and global ancestry, estimated using ADMIXMAP26,27 were used to identify population outliers (with ancestral allele frequencies from African, European, American Indian, and East Asian populations23,24). For inclusion, SNPs had to meet the following criteria: well-defined cluster plots, call rate >90%, minor allele frequencies >0.001 and P>0.001 for Hardy-Weinberg proportion tests in controls. We removed 1,182 samples because of low call rates (<90%), sample heterozygosity outliers (>5 standard deviations from the mean), extreme population outliers (based on global ancestry estimation and principal component analysis), sample duplicates (the proportion of alleles shared identity by descent (IBD) >0.4), gender discrepancies between reported gender and genetic data, and genotype/imputation error discovered by resequencing (Supplementary Table 2). comprised 113 TNFAIP3 SNPs and 262 AIMs and 15,817 samples (Table 1).

Imputation Methods

Imputation was performed 137.9 Mb to 138.4 Mb on chromosome 6q with the genotype data as the source of observed genotypes and the 1000 Genomes Project and the Phase III HapMap release 2 as reference using IMPUTE2 program28–30. IMPUTE2 calculates posterior probabilities for the three possible genotypes (i.e. AA, AB, and BB). We converted the posterior probabilities to the most likely genotypes with a threshold of 0.8 and removed imputed SNPs with less than 90% average certainty of the most probable genotypes. At a call threshold of 0.8, more than 87% of the imputed genotypes were called and more than 94% of those were concordant with the known genotypes. The composition of the 1000 Genomes Project and Phase III HapMap reference panels for each population imputation can be found in Supplementary Table 3. After imputation, our datasets comprised a minimum of 351 SNPs for each of the populations (the number varied based on linkage disequilibrium structure) (Supplementary Table 3).

Association Analyses

The single marker association analyses were calculated using the logistic regression function in PLINK31 and R under the additive model adjusting for sex and either global ancestry (African, European, and East Asian) or the first three principal components, with no observable difference. Conditional analyses were also performed using PLINK and R and were adjusted for sex and global ancestry as well as each SNP, one-at-a-time, within the risk haplotype.

LD between variants was estimated and probable haplotypes were calculated followed by haplotypic association using Haploview version 4.232 for all haplotypes formed by the associated markers with P < 1 × 10−4 (28 SNPs) that are common in EA and Koreans. We used those SNPs to construct haplotypes for AA, AAG, and HS (Supplementary Fig. 7). The pairwise linkage LD for SNPs across TNFAIP3 was confirmed by the r2 values. Haplotype blocks were calculated using the solid-spine of LD algorithm with a minimum D’ value of 0.832. Only haplotypes with a frequency of at least 1.0% were included in the haplotype analysis. The haplotype blocks were then compared to narrow down the region of interest. Power to detect association to the TT>A effect in the AA, AAG, and HS populations was determined using the available sample sizes, assuming an OR of 1.7 (as seen in the EA), a type I error rate of 0.0001, and the respective minor allele frequency (MAF).

Resequencing

Targeted sequence capture followed by resequencing was performed using the Agilent SureSelect and Illumina GAIIx platforms, respectively. Data generated using the Illumina GAIIx instrument was processed using the Illumina Pipeline software (v.1.7). Duplicate reads were removed and unique reads as well as sequence contigs were assembled and analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench Software 4.0. All samples were sequenced to minimum average fold coverage of 25X.

We resequenced the TNFAIP3 risk segment of two EA cases homozygous for the risk haplotype, five EA cases heterozygous for the risk haplotype (although phase was estimated not confirmed) and three EA cases with no copies of the risk haplotype using solution-based sequence capture and massively parallel sequencing. We identified 258 variants (233 SNPs and 26 deletion/insertion polymorphisms (DIPs)) that differed from the reference sequence (hg18) across the 174 kb targeted region from 138,173,000 to 138,347,000 bp. Of these, 220 were already documented in the HapMap or 1000 Genomes Project databases leaving 29 novel SNPs and 9 novel DIPs (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 6). No single SNP was observed in more than one individual and thus not likely to be carried on the TNFAIP3 risk haplotype. Among the 9 novel DIPs only one was observed with the expected risk genotype distribution and was found at position chr6:138271732, immediately adjacent to SNP chr6:138271733.

Genotyping the TT>A Polymorphic Dinucleotide in African-Americans

The TT>A variant genotyping was performed on a Li-Cor Longread IR 4200 DNA sequencer using a PCR based assay and a Li-Cor IR 700nm labeled M13 forward primer and two unlabeled TNFAIP3 primers (Supplementary Table 7). Individual PCR reactions were set up in a 10ul volume using 0.25 Units Takara Taq DNA polymerase, 1 X PCR buffer, 1 X dNTPs (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA), 19 mM MgCl2, 1.5 uM each primer, and 10 ng genomic DNA. PCR reactions were denatured at 94oC for 3 minutes, followed by 33 cycles of 94oC for 30 seconds, 57oC for 45 seconds and 72oC for 1 minute followed by a final extension at 72oC for 2 minutes. Samples were held at 10oC until they were run on the Li-Cor sequencers. The 100 bp insertion and/or 99 bp deletion amplification products were separated and detected on 6% polyacrylamide gels run with 1X TBE buffer for 945 AA cases and 1,307 controls and 127 AAG cases and 116 controls. The allele frequency of the TT>A variant expected in the AA due to European admixture alone (0.429–0.585%) was calculated as the product of the EA minor allele frequency (3.9%) and the proportion of the genome expected to originate from the European population, in this case 11% to 15%33. This was similarly calculated for the HS population (MAF=1.8% to 3.2%) based on recent European admixture estimates ranging from 48% to 82%34.

Cell Culture

Human monocyte cell lines, THP-1 and U937, were purchased from ATCC. Cells were maintained in RPMI (Gibco Invitrogen) with 10% FBS, L-glutamine (2mM), penicillin and streptomycin (100 units/mL). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

A 248 base pair oligonucleotide was generated by PCR amplification using AccuPrime pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with two primers (Supplementary Table 8) and template DNA from either homozygous risk or non-risk subjects. The amplified product was gel-purified and end-labeled with (γ-32P) adenosine triphosphate (MP Biomedicals Int.) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Invitrogen). A portion of each probe preparation was sequenced to verify no mutations had been introduced during amplification. Nuclear protein extracts were prepared from cells stimulated with LPS (1ug/mL) for 3 hours and incubated for 25 min at 37°C with labeled probes in binding buffer (1ug poly (dI-dC), 20mM HEPES, 10% Glycerol, 100mM KCl, and 0.2mM EDTA, pH 7.9). DNA-protein complexes were resolved on denaturing 5% acrylamide gels. Supershift assays were performed by adding 80–100ug of anti-p50, p65, c-Rel (GeneTex) or Rabbit IgG isotope control (Alpha Diagnostic Int. Inc.) to the mixture followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min prior to adding labeled probe. Densitometry measurements of EMSA bands were performed using a Bio-Rad Universal Hood II Gel Docking Station and Quantity One analysis software. The density value of each band was recorded and normalized to the background for each blot. Statistical analyses were performed using a paired t-test and Prism 5.0 software.

A20 Protein Expression

EBV-transformed B cell lines were obtained from the Large Lupus Family Registry (OMRF) with IRB approval and selected using genotype data corresponding to the TT>A variant proxy marker rs7749323. Cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, L-glutamine and 55uM beta-mercaptoethanol. Equal numbers of cells were harvested under basal conditions in log-phase growth and were lysed in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris, 1% TritonX-100, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.25% deoxycholate and protease inhibitors). Lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western transfer. Membranes were immunoblotted for A20 (Ebioscience) and GAPDH (Imgenex). Bands were revealed radiographically, scanned, and band intensity analyzed using Image J (NIH) software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the individuals with SLE and controls who participated in this study. We are grateful to the research assistants, coordinators and physicians that helped in the recruitment of subjects. We would like to thank the following individuals for contributing samples genotyped in this study: Drs. Sandra D’Alfonso (Italy), Rafaella Scorza (Italy), Peter Junker and Helle Laustrup (Denmark), Marc Bijl (Holland), Emoke Endreffy (Hungary), Carlos Vasconcelos and Berta Martins da Silva (Portugal), Ana Suarez and Carmen Gutierrez (Spain), Iñigo Rúa-Figueroa (Spain) and Dr. Cintia Garcilazo (Argentina). For the AADEA collaboration: Norberto Ortego-Centeno (Spain), Juan Jimenez-Alonso (Spain), Enrique de Ramon (Spain) and Julio Sanchez-Roman (Spain). For the GENLES collaboration: Dr Mario Cardiel (Mexico), Dr Ignacio García de la Torre (Mexico), Marco Maradiaga (Mexico), José F. Moctezuma (Mexico), Dr Eduardo Acevedo (Peru), Cecilia Castel and Mabel Busajm (Argentina), Jorge Musuruana (Argentina). Other participants from the Argentine Collaborative Group are: Hugo R. Scherbarth MD, Pilar C. Marino MD, Estela L. Motta MD; Susana Gamron MD, Cristina Drenkard MD, Emilia Menso MD; Alberto Allievi MD, Guillermo A. Tate MD; Jose L. Presas MD; Simon A. Palatnik MD, Marcelo Abdala MD, Mariela Bearzotti PhD; Alejandro Alvarellos MD, Francisco Caeiro MD, Ana Bertoli MD; Sergio Paira MD, Susana Roverano MD, Hospital José M. Cullen; Cesar E. Graf MD, Estela Bertero PhD; Carolina Guillerón MD, Sebastian Grimaudo PhD, Jorge Manni MD; Luis J. Catoggio MD, Enrique R. Soriano MD, Carlos D. Santos MD; Cristina Prigione MD, Fernando A. Ramos MD, Sandra M. Navarro MD; Guillermo A. Berbotto MD, Marisa Jorfen MD, Elisa J. Romero PhD; Mercedes A. Garcia MD, Juan C Marcos MD, Ana I. Marcos MD; Carlos E. Perandones MD, Alicia Eimon MD; Cristina G. Battagliotti MD.

We thank Mary C Comeau, MA; Miranda C Marion, MA; Paula S Ramos, PhD; Adam Adler; Summer Frank, MPH; Stuart Glenn, and Mai Li Zhu, MS for their assistance in genotyping, quality control analyses, and clinical data management; Rufei Lu and Nicolas Dominguez for their assistance with EMSA; J. Donald Capra, MD for his critical reading of the manuscript; and the staff of the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR) for collecting and maintaining SLE samples. Support for this work was obtained from the US National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI063274 and R01 AR056360 (P.M.G.); R01 AR043274 (K.L.M.); N01 AR62277, R37 24717, R01 AR042460, P01 AI083194, P20 RR020143, R01 DE018209 (J.B.H.); P01 AR49084 (R.P.K. and E.E.B); R01 AR33062 (R.P.K.); P30 AR055385 (E.E.B); K08 AI083790, LRP AI071651, UL1 RR024999 (T.B.N.); R01CA141700, RC1AR058621 (M.E.A.R.); R01AR051545-01A2, ULI RR025014-02 (A.M.S.); P30 AR053483, N01 AI50026 (J.A.J and J.M.G); P20 RR015577 (J.A.J); R21 AI070304, R01 AI070983 (S.A.B.); R01 AR43814 (B.P.T.); P60 AR053308, M01 RR-00079 (L.A.C.); R01 AR043727, UL1 RR025005 (M.A.P.). A portion of this study was supported by a grant of the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A010252, A080588; S.C.B.). Additional support was granted from the Alliance for Lupus Research (K.L.M.); Merit Award from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (J.B.H. and G.S.G.); the Swedish Research Council for Medicine, Gustaf Vth-80th Jubilee Fund and Swedish Association Against Rheumatism, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) HR09-106 (M.E.A.R.); the European Science Foundation funds the BIOLUPUS network (M.E.A.R. coordinator); the Barrett Scholarship Fund OMRF (C.J.L.); Lupus Research Institute (T.B.N.); The Alliance for Lupus Research (T.B.N., L.A.C. and C.O.J.); the Arthritis National Research Foundation Eng Tan Scholar Award (T.B.N.); Arthritis Foundation (P.M.G. and A.M.S); the Lupus Foundation of Minnesota (P.M.G. and K.L.M.); the Wellcome Trust (T.J.V.); Arthritis Research UK (T.J.V.); Kirkland Scholar Award (L.A.C.) and Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center for Public Health Genomics (C.D.L.). The work reported on in this publication has been in part financially supported by the ESF, in the framework of the Research Networking Programme European Science Foundation - The Identification of Novel Genes and Biomarkers for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (BIOLUPUS) 07-RNP-083.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.M.G., C.G.M., K.L.M., C.J.L., J.A.K., K.M.K., C.D.L., and J.B.H. selected SNPs and were responsible for the study design. M.E.A.R., J.M.A., S.C.B., S.Y.B, S.A.B., E.E.B., M.A.P., C.G., R.R.G., J.D.R., L.M.V., L.A.C., J.C.E., B.I.F., P.K.G., G.S.G., C.O.J., J.A.J., D.L.K., R.P.K., J.M., J.T.M., T.B.N., S.Y.P., B.A.P.E., A.M.S., B.P.T., L.M.V., T.J.V., J.B.H., K.L.M., and P.M.G. assisted in the collection and characterization of the SLE cases and controls. K.M.K. and P.M.G. performed the genotyping. K.M.K. and C.D.L. performed quality control analyses. I.A. and J.S.B. performed association analyses and imputation under the guidance of C.G.M. and P.M.G.; F.W., G.W. and P.M.G. performed the sequencing. F.W., A.T., J.B.K., Y.H., C.F.W., M.B.H., and P.M.G. performed functional studies. I.A., C.G.M., and P.M.G. prepared the manuscript and all authors approved the final draft.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jaattela M, Mouritzen H, Elling F, Bastholm L. A20 zinc finger protein inhibits TNF and IL-1 signaling. J Immunol. 1996;156:1166–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee EG, et al. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science. 2000;289:2350–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boone DL, et al. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 is required for termination of Toll-like receptor responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1052–60. doi: 10.1038/ni1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hitotsumatsu O, et al. The ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 restricts nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2-triggered signals. Immunity. 2008;28:381–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavares RM, et al. The ubiquitin modifying enzyme A20 restricts B cell survival and prevents autoimmunity. Immunity. 2010;33:181–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plenge RM, et al. Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1477–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson W, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis association at 6q23. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1431–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dieude P, et al. Association of the TNFAIP3 rs5029939 variant with systemic sclerosis in the European Caucasian population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham RR, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1059–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musone SL, et al. Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1062–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates JS, et al. Meta-analysis and imputation identifies a 109 kb risk haplotype spanning TNFAIP3 associated with lupus nephritis and hematologic manifestations. Genes Immun. 2009;10:470–7. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han JW, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siepel A, et al. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1034–50. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King DC, et al. Evaluation of regulatory potential and conservation scores for detecting cis-regulatory modules in aligned mammalian genome sequences. Genome Res. 2005;15:1051–60. doi: 10.1101/gr.3642605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birney E, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasowski M, et al. Variation in transcription factor binding among humans. Science. 2010;328:232–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1183621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parra EJ, et al. Ancestral proportions and admixture dynamics in geographically defined African Americans living in South Carolina. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114:18–29. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200101)114:1<18::AID-AJPA1002>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stranger BE, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1217–24. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodolce JP, et al. African-derived genetic polymorphisms in TNFAIP3 mediate risk for autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:7001–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham RR, et al. A common haplotype of interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) regulates splicing and expression and is associated with increased risk of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2006;38:550–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieberman-Aiden E, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MW, et al. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in african americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1001–13. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halder I, Shriver M, Thomas M, Fernandez JR, Frudakis T. A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual biogeographical ancestry and admixture from four continents: utility and applications. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:648–58. doi: 10.1002/humu.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoggart CJ, et al. Control of confounding of genetic associations in stratified populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1492–1504. doi: 10.1086/375613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoggart CJ, Shriver MD, Kittles RA, Clayton DG, McKeigue PM. Design and analysis of admixture mapping studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:965–78. doi: 10.1086/420855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Via M, Gignoux C, Burchard EG. The 1000 Genomes Project: new opportunities for research and social challenges. Genome Med. 2:3. doi: 10.1186/gm124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frazer KA, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–61. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population- based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tishkoff SA, et al. The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans. Science. 2009;324:1035–44. doi: 10.1126/science.1172257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bertoni B, Budowle B, Sans M, Barton SA, Chakraborty R. Admixture in Hispanics: distribution of ancestral population contributions in the Continental United States. Hum Biol. 2003;75:1–11. doi: 10.1353/hub.2003.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.