Abstract

Haemophilus ducreyi resists killing by antimicrobial peptides encountered during human infection, including cathelicidin LL-37, α-defensins, and β-defensins. In this study, we examined the role of the proton motive force-dependent multiple transferable resistance (MTR) transporter in antimicrobial peptide resistance in H. ducreyi. We found a proton motive force-dependent effect on H. ducreyi's resistance to LL-37 and β-defensin HBD-3, but not α-defensin HNP-2. Deletion of the membrane fusion protein MtrC rendered H. ducreyi more sensitive to LL-37 and human β-defensins but had relatively little effect on α-defensin resistance. The mtrC mutant 35000HPmtrC exhibited phenotypic changes in outer membrane protein profiles, colony morphology, and serum sensitivity, which were restored to wild type by trans-complementation with mtrC. Similar phenotypes were reported in a cpxA mutant; activation of the two-component CpxRA regulator was confirmed by showing transcriptional effects on CpxRA-regulated genes in 35000HPmtrC. A cpxR mutant had wild-type levels of antimicrobial peptide resistance; a cpxA mutation had little effect on defensin resistance but led to increased sensitivity to LL-37. 35000HPmtrC was more sensitive than the cpxA mutant to LL-37, indicating that MTR contributed to LL-37 resistance independent of the CpxRA regulon. The CpxRA regulon did not affect proton motive force-dependent antimicrobial peptide resistance; however, 35000HPmtrC had lost proton motive force-dependent peptide resistance, suggesting that the MTR transporter promotes proton motive force-dependent resistance to LL-37 and human β-defensins. This is the first report of a β-defensin resistance mechanism in H. ducreyi and shows that LL-37 resistance in H. ducreyi is multifactorial.

INTRODUCTION

Haemophilus ducreyi is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease chancroid, which has been shown to facilitate the transmission of HIV (47, 51). During human infection, H. ducreyi is surrounded by professional phagocytes and is subject to attack by these and other components of a robust innate immune response (7, 8). Some of the major virulence factors of H. ducreyi are those that allow the organism to circumvent the innate immune system. For example, the secreted proteins LspA1 and LspA2 are key to resisting phagocytosis, and the outer membrane protein (OMP) DsrA confers resistance to killing by human serum (17, 24). Although little is known about how H. ducreyi regulates virulence factors, DsrA and LspA2, along with the secretory protein LspB, are controlled by the CpxRA two-component regulator (29, 48). H. ducreyi lacking the sensor kinase component gene cpxA is attenuated in a human model of infection, possibly because of dysregulation of important virulence determinants (48). Thus, the CpxRA regulon plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of H. ducreyi infection.

During human disease, H. ducreyi is surrounded by antimicrobial peptide (AP)-secreting cells, including neutrophils and macrophages (7, 8, 10). APs are small cationic peptides that aid in the killing of microorganisms through membrane disruption or effects on intracellular targets (14). APs play a protective role by controlling bacterial infection; however, successful pathogens have developed a variety of mechanisms to resist AP-mediated killing (13, 25, 27). H. ducreyi is resistant to human APs found during infection, including α-defensins, β-defensins, and cathelicidin LL-37 (34). The Sap uptake transporter in H. ducreyi confers resistance to LL-37 and contributes to virulence in humans (35). Interestingly, the H. ducreyi Sap transporter does not confer resistance to α- or β-defensins, suggesting that H. ducreyi possesses other mechanisms to survive attack by defensins (35).

One AP resistance mechanism employed by other Gram-negative pathogens is the multiple transferable resistance (MTR) efflux transporter, which actively exports a variety of hydrophobic substrates, such as antibiotics, detergents, and APs, using energy provided by the cell's proton motive force (PMF) (46). MTR pumps are in the resistance-nodulation-division (RND) family of drug efflux pumps, which form tripartite export systems (4, 31). The energy-dependent MTR pump in Neisseria gonorrhoeae comprises an inner membrane transporter protein (MtrD), a periplasmic membrane fusion protein (MtrC), and an outer membrane channel protein (MtrE). In N. gonorrhoeae, MTR confers resistance to a variety of hydrophobic agents, including LL-37 and the porcine AP protegrin 1 (46).

In this study, we demonstrated that H. ducreyi expresses a PMF-dependent AP resistance mechanism. We identified homologs of the three MTR structural genes in the H. ducreyi genome and constructed a nonpolar, unmarked deletion mutation in the gene encoding the putative periplasmic component MtrC. We found that the mtrC mutant was significantly less resistant than the parent strain to LL-37 and β-defensins but showed wild-type resistance to α-defensins; this phenotype was fully complemented in trans. Interestingly, the mtrC mutation activated the CpxRA two-component regulator, which in part contributed to LL-37 resistance. The MTR transporter represents the first mechanism identified for β-defensin resistance in H. ducreyi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains are listed in Table 1. Except where noted, H. ducreyi strains were grown at 33°C with 5% CO2 on chocolate agar plates supplemented with 1% IsoVitaleX and, for strains harboring plasmid vectors or antibiotic resistance cassettes, appropriate antibiotics, including spectinomycin (200 μg/ml), kanamycin (20 μg/ml), or streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (35). For antimicrobial assays, strains were grown in Columbia broth supplemented with hemin (50 μg/ml) (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI), 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 1% IsoVitaleX, and half the concentration of appropriate antibiotics. Escherichia coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth with appropriate antibiotics, including spectinomycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (50 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), or streptomycin (100 μg/ml), except for strain DY380, which was grown in L-Broth at 32°C or 42°C as indicated (48, 50).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araΔ139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (strR) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| HB101 | F thi-1 hsdS20(rB− mB−) supE44 recA13 ara-14 leuB6 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 (strR) xyl-5 mtl-1 | Promega |

| DY380 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7649 galU galK rspL nupG [λ cI857 Δ(cro-bioA) (tetR)] | 50 |

| MEB149 | DY380 with plasmid pMEB144 | This study |

| H. ducreyi | ||

| 35000HP | Class I clinical isolate; human-passaged variant of strain 35000; Winnipeg, Canada, 1975 | 3 |

| HD183 | Class I clinical isolate; Singapore, 1982 | 9, 49 |

| HD188 | Class I clinical isolate; Kenya, 1982 | 9, 49 |

| 82-029362 | Class I clinical isolate; California, 1982 | 9, 49 |

| 6644 | Class I clinical isolate; Massachusetts, 1989 | 9, 49 |

| 85-023233 | Class I clinical isolate; New York, 1985 | 9, 49 |

| CIP542 ATCC | Class II clinical isolate; Hanoi, Viet Nam, 1954 | 23, 54 |

| HMC112 | Class II clinical isolate; 1984 (location not reported) | 54 |

| 33921 | Class II clinical isolate; Kenya (yr not reported) | 9, 15 |

| DMC164 | Class II clinical isolate; Bangladesh (yr not reported) | 54 |

| 35000HP(pLSSK) | 35000HP with vector pLSSK; Strr | This study |

| 35000HPmtrC | mtrC unmarked deletion mutant of 35000HP | This study |

| 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) | 35000HPmtrC with vector pLSSK; Strr | This study |

| 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) | mtrC unmarked deletion mutant of 35000HP with plasmid pMEB219; Strr | This study |

| FX517 | dsrA::cat insertion mutant of 35000; Cmr | 17 |

| 35000HPΔcpxA | cpxA unmarked deletion mutant of 35000HP | 48 |

| 35000HPΔcpxR | cpxR::cat insertion/deletion mutant of 35000HP; Cmr | 28 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | TA cloning vector; Ampr | Promega |

| pCR-XL-TOPO | TA cloning vector; Kanr | Invitrogen |

| pRSM2832 | Specr cassette flanked by FTR sites | 50 |

| pRSM2975 | FLP recombinase vector | 48 |

| pLSSK | H. ducreyi shuttle vector; Strr | 55 |

| pRSM2072 | Suicide vector; Ampr | 12 |

| pMEB144 | mtrC + flank in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pMEB191 | mtrC replaced with Specr cassette in pGEM-T Easy | This study |

| pMEB193 | mtrC replaced with Specr cassette in pRSM2072 | This study |

| pMEB219 | mtrC in pLSSK | This study |

Strr, resistance to streptomycin; Cmr, resistance to chloramphenicol; Ampr, resistance to ampicillin; Kanr, resistance to kanamycin; Specr, resistance to spectinomycin.

Construction and characterization of a nonpolar, unmarked mtrC deletion mutation in H. ducreyi.

We used “recombineering” to generate an mtrC deletion mutant, as described previously (48, 50). This method allows the deletion of the mtrC gene, leaving a 35-codon open reading frame (ORF) that includes the last 7 codons of the mtrC gene (48). Briefly, a 3.8-kb PCR product containing mtrC was amplified from 35000HP genomic DNA with primers mtrcfor1 and mtrcrev1 (Table 2) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, WI) to generate pMEB144. E. coli strain DY380 was transformed with pMEB144 and maintained at 32°C to generate MEB149. MEB149 was grown to mid-logarithmic phase, incubated at 42°C for 15 min to induce the lambda red recombinase, and then transformed with a 2.2-kb PCR fragment containing a spectinomycin resistance (Specr) cassette flanked by flippase (FLP) recognition target (FRT) sites and 50 bp flanking mtrC that had been amplified from pRSM2832 with primers H1P1mtrc and H2P2mtrc (48). Recombination in MEB149 replaced mtrC with the FRT-Specr-FRT cassette. A plasmid with the correct digestion pattern (pMEB191) was digested with SpeI to generate a 4.5-kb fragment containing the recombined mtrC locus, which was ligated into the suicide plasmid pRSM2072 to generate pMEB193. pMEB193 was passaged through E. coli HB101 before H. ducreyi transformation.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Construct or use | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| mtrCfor1 | pMEB144 | CAGTTTGCCCAATCGTGGCGATAA |

| mtrCrev1 | pMEB144 | ACCGCTCCAGCAAGTGTTAAGGAA |

| H1P1 mtrC | pMEB191 | CATCAGTAAATAAACTGCTTATTGCATAAAGTGTAGCTTGAAAAATTATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC |

| H2P2 mtrC | pMEB191 | AAATATCTGTGAACATGAAAATGCCTCAATTATAAGTTTGTTTCTATGGCTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG |

| glmUfor1 | qRT-PCR | TATGGGCACGGCGGTGACTTATTA |

| glmUrev1 | qRT-PCR | TTTGCTGCGATAAGGCGGGTTAAG |

| mtrCcompfor1 | pMEB219 | TATCGGCTTGTGCAATCG |

| mtrCcomprev1 | pMEB219 | AGGTAGTTGGATATGTACAAGATT |

| mtrCfor2 | Class conservation | TGTGGCATGCTCATAATTGATTT |

| mtrCrev2 | Class conservation | CTAATCGCTAATACTGGGCGCT |

| HD0281for1 | qRT-PCR | ATATCAGCTATGGCTGCTCCTCCA |

| HD0281rev1 | qRT-PCR | CCGCTGCAGTTTGCCCTAAATCAA |

| HD0769for1 | qRT-PCR | ATTACAACAATGGCTCAGCAGCCG |

| HD0769rev1 | qRT-PCR | ACCGCCTTCATTAGACCAAGTCCA |

| HD1155for1 | qRT-PCR | AGCTAGAGCGGCTGACCCATTAAA |

| HD1155rev1 | qRT-PCR | GTGAGAAATTGCTCCGCTTTGGCT |

| HD1435for1 | qRT-PCR | TCGGCCTCAGCAGTTACGCTTTAT |

| HD1435rev1 | qRT-PCR | ACCCGCATTACGTATCGCATGTTC |

35000HP was transformed with 3.6 μg of pMEB193 and screened for Specr. Twenty-seven colonies were subcultured onto chocolate agar plates containing spectinomycin and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (Roche, Indianapolis, IN; 40 μg/ml). White colonies were tested by colony PCR for the insertion of the Specr cassette in the mtrC locus. A clone with the correct insert was transformed with pRSM2975, a temperature-sensitive plasmid containing FLP recombinase under the control of the tet promoter (50). Transformants were selected on chocolate agar supplemented with kanamycin and cultured at 32°C to maintain pRSM2975. Expression of the FLP recombinase was induced with anhydrotetracycline (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) in mid-logarithmic phase, and the culture was plated on chocolate agar plates and grown at 35°C to promote the loss of pRSM2975. Colonies were replica plated on plates containing spectinomycin, kanamycin, or no antibiotic to screen for the FRT recombination event and the loss of pRSM2975. Of 89 colonies screened, recombination at the FRT site occurred in 1 colony, and loss of the recombinase plasmid occurred in 21 of 89 colonies. Because no colonies screened were sensitive to both spectinomycin and kanamycin, the spectinomycin-sensitive colony was grown at 35°C for 48 h on plates without antibiotics to obtain a kanamycin-sensitive derivative that had lost pRSM2975; the clone was named 35000HPmtrC.

The desired construct in 35000HPmtrC was confirmed by PCR and sequencing. Growth curves indicated no significant changes in growth rates compared with the parent strain (data not shown). Outer membrane protein preparations and Western blot analysis were performed as described previously (35). Densitometry of scanned immunoblots was performed using NIH ImageJ software (2).

Complementation in trans.

A 1.8-kb fragment containing 286 bp 5′ of the mtrC ATG start codon, including the predicted promoter region, was amplified from genomic DNA of 35000HP with primers mtrccompfor1and mtrccomprev1 and cloned into pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), resulting in pMEB215. A 1.9-kb fragment was excised from pMEB215 by digestion with NotI and BamHI and ligated into the shuttle vector pLSSK, resulting in the 5.4-kb plasmid pMEB219. 35000HPmtrC was transformed with pMEB219 to obtain 35000HPmtrc(pmtrC). 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC were transformed with pLSSK to generate 35000HP(pLSSK) and 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK), respectively.

AP bactericidal assays.

Recombinant α- and β-defensin peptides were purchased from AnaSpec (San Jose, CA), PeproTech Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ), Peptides International (Louisville, KY), and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); synthetic LL-37 was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Belmont, CA).

AP assays were performed as described previously (34, 35). Briefly, H. ducreyi strains were grown to mid-logarithmic phase, harvested, washed, and diluted in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, supplemented with 1% Columbia broth. Approximately 2,000 CFU of bacteria was added to a 96-well plate with various concentrations of diluted peptide. LL-37 was reconstituted in 10% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and further diluted in 0.01% acetic acid, HBD-3 and HBD-2 were reconstituted and diluted in 0.01% acetic acid, and all other peptides were reconstituted and diluted in water. Assays were performed in duplicate for each peptide concentration. After 1 h of incubation, each well was plated in triplicate on chocolate agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Survival of bacteria at each concentration of peptide was compared to their survival in control wells with no peptide. Because of batch-to-batch variation in the activities of APs, statistical comparisons between strains for their sensitivity to a given AP were made only when assayed side by side. We used Student's t test with Sidak adjustment for multiple comparisons to determine statistical significance.

For assays examining the effects of the PMF on AP resistance, the PMF-uncoupling reagent carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI) was used, following a modified protocol from Shafer et al. (46). Briefly, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 100 μM CCCP diluted in DMSO was incubated with approximately 2,000 CFU of washed, mid-logarithmic phase bacteria for 20 min at 33°C with 5% CO2. Following the uncoupling step, the indicated concentration of peptide was added and samples were incubated for 1 h. Wells were plated, and percent survival was calculated as described above.

Serum bactericidal assays.

H. ducreyi strains were assayed for survival in human serum, as described previously (1, 6, 48). Briefly, 14- to 16-h growth from confluent plates was scraped into gonococcal (GC) broth and diluted to 2,000 CFU/ml. Bacteria were mixed 1:1 with human serum that either was active or had been heat inactivated at 56°C for 35 min. Survival was determined by plate count after 45 min of incubation with the indicated serum at 33°C with 5% CO2. Assays were performed in triplicate. The percent survival was calculated as follows for each strain: 100 × average (CFU/plate)active/average (CFU/plate)heat inactive. We used Student's t test with Sidak adjustment for multiple comparisons to determine statistical significance.

qRT-PCR.

We analyzed RNA isolated from 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC for transcripts of glmU, the downstream gene in the mtrCD locus, and four genes regulated by CpxRA, dsrA, ompP2B, lspB, and fimA, by quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR), as described previously (35). Briefly, RNA was isolated from three independent mid-logarithmic cultures with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was treated twice with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX) for 45 min each time at 37°C and purified with an RNeasy spin column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA samples were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis following RT-PCR to evaluate DNA contamination. Reactions were carried out with the one-step QuantiTect SYBR green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen), and the Pfaffl method was used to determine the relative quantification of the target gene compared to the constitutively expressed gyrB (gene ID, HD1643) as a reference (36). We used the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) for qRT-PCR of glmU and the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad CA) for the other four genes.

Survey of H. ducreyi clinical isolates for the mtrC gene.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from six class I and four class II clinical H. ducreyi isolates (Table 1), as described previously (9). A 1.5-kb fragment containing the mtrC open reading frame was PCR amplified using primers mtrcfor2 and mtrcrev2 (Table 2) and sequenced by the DNA Sequencing Core Facility at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Sequences were aligned using the ClustalW algorithm in the Lasergene software package (DNAStar version 7).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the mtrC alleles are available in GenBank under accession numbers HQ712073 to HQ712081.

RESULTS

AP resistance in H. ducreyi is partially proton motive force dependent.

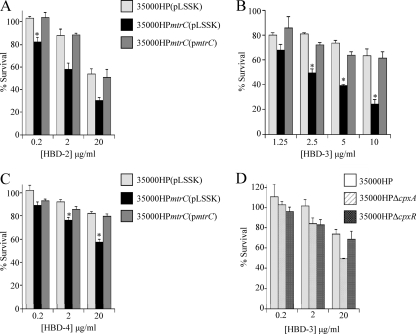

Our previous research established that H. ducreyi utilizes the Sap transporter to resist killing by the human cathelicidin LL-37; however, the Sap transporter did not confer resistance to either α- or β-defensins (35). With the goal of identifying resistance mechanisms against human defensins, we tested H. ducreyi for a PMF-dependent AP resistance mechanism using the PMF uncoupler CCCP. In these assays, H. ducreyi was preincubated with CCCP before challenge with APs. Preliminary studies showed that the CCCP diluent DMSO had no effect on H. ducreyi survival or on AP activity against H. ducreyi (data not shown). Upon challenge with APs, CCCP-treated H. ducreyi was more susceptible than DMSO-treated H. ducreyi to both LL-37 (Fig. 1A) and human β-defensin 3 (HBD-3) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, CCCP treatment had no effect on survival in the presence of the α-defensin human neutrophil peptide 2 (HNP-2) (data not shown). These data show that H. ducreyi contains a PMF-dependent mechanism for resistance to LL-37 and β-defensins, but not α-defensins.

Fig. 1.

H. ducreyi has a PMF-dependent mechanism for LL-37 and HBD-3 resistance. Shown are bactericidal assays with 35000HP after pretreatment with the PMF inhibitor CCCP, or its diluent DMSO, and either LL-37 (2 μg/ml) (A) or HBD-3 (10 μg/ml) (B). The data represent the means and standard errors of four independent assays. The single asterisks indicate significant differences from the control, which received neither CCCP nor AP (P < 0.02); the double asterisks indicate significant differences in AP sensitivity with or without CCCP pretreatment (P ≤ 0.001).

Characterization of mtr genes in H. ducreyi.

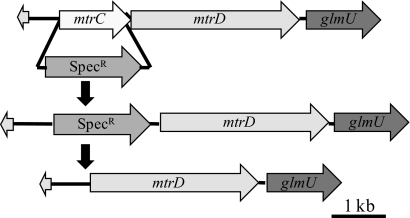

Previous work with N. gonorrhoeae has shown that CCCP-mediated inactivation of the MTR transporter increases sensitivity to APs (46). A search of the H. ducreyi genome for possible RND pumps, such as MTR, revealed a locus encoding two putative RND efflux components. HD1512 encodes a predicted protein that is 31% identical and 37% similar to the N. gonorrhoeae MtrD inner membrane protein; directly upstream is HD1513, which encodes a putative RND efflux membrane fusion protein that is 29% identical and 44% similar to N. gonorrhoeae MtrC, which we termed mtrC (Fig. 2). By RT-PCR analysis, we confirmed that mtrC, mtrD, and the downstream gene glmU were cotranscribed in an operon (data not shown). The genetically unlinked HD1829 encodes a putative outer membrane efflux transporter with homology to the NodT-MtrE-TolC efflux transporters (E values, 10−167 to 10−90) that is 25% identical and 47% similar to N. gonorrhoeae MtrE. No other NodT-MtrE-TolC family members were found in the genome of 35000HP.

Fig. 2.

Genetic map of the mtrCD-containing operon and mutagenesis strategy for constructing 35000HPmtrC. The mtrC gene was first replaced with a Specr cassette flanked by FRT sites, and then FLP recombinase was introduced to recombine the FRT sites and excise the Specr cassette, leaving a single FRT site in place of mtrC.

Pleiotropic effects of the mtrC gene deletion in H. ducreyi.

To study the effects of the MTR transporter, we used the “recombineering” method recently developed for use in H. ducreyi to construct a nonpolar, unmarked mtrC mutation in 35000HP, designated 35000HPmtrC (48) (Fig. 2). A single base change was found in the downstream mtrD ORF, which would cause a D154N amino acid change. The operon contained the native promoter, and qRT-PCR analysis verified that 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC had similar levels of glmU expression, confirming the lack of polarity of the mutation on downstream genes (data not shown). We complemented 35000HPmtrC in trans with the intact mtrC ORF, along with its native promoter, on the shuttle vector pLSSK to generate 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC).

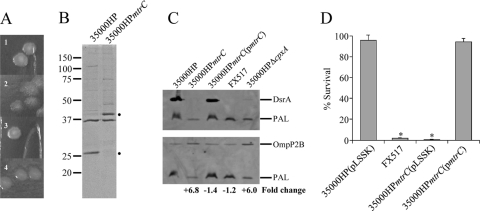

Deletion of mtrC led to phenotypic changes in colony morphology and OMP profiles. On chocolate agar, colonies of 35000HP(pLSSK) were opaque, smooth, and round, while the 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) mutant colonies were translucent, rough, and irregularly shaped (Fig. 3A, 1 and 2, respectively). This colony morphology was restored to wild type when complemented in trans with mtrC (Fig. 3A, 3). OMP profiles showed two changes in 35000HPmtrC compared with 35000HP. 35000HPmtrC lacked a 28-kDa band and showed increased intensity in a 43-kDa band (Fig. 3B). This altered OMP profile was reminiscent of the OMP profile of a cpxA mutant, which does not express the 28-kDa DsrA and overexpresses the 43-kDa OmpP2B protein (28, 48). We used Western blot analysis to confirm that DsrA and OmpP2B were the proteins with altered expression in 35000HPmtrC (Fig. 3C). DsrA was not detected in whole-cell lysates of 3500HPmtrC but was restored to wild-type levels when 35000HPmtrC was trans-complemented with mtrC (Fig. 3C, top, lanes 1 to 3). As expected, DsrA expression was not detected in the dsrA mutant FX517 or in the cpxA mutant (Fig. 3C, top, lanes 4 and 5). To quantitate the level of OmpP2B in 35000HPmtrC, whole-cell lysates were probed with antibodies against OmpP2B and the constitutively expressed OMP PAL (Fig. 3C, bottom). 35000HP, 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC), and FX517 showed similar expression levels of OmpP2B (lanes 1, 3, and 4); 35000HPmtrC and 35000HPΔcpxA showed levels of OmpP2B that were elevated 6.8- and 6.0-fold, respectively, compared to 35000HP (Fig. 3C, bottom, lanes 2 and 5).

Fig. 3.

Pleiotropic phenotypes of 35000HPmtrC. (A) Colony morphologies of 35000HP(pLSSK) (1), 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) (2), 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) (3), and 35000HPΔcpxA (4) on chocolate agar plates after 3 to 4 days of growth. (B) Coomassie-stained outer membrane proteins of 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC. The dots to the right of the blot indicate changes in band expression in 35000HPmtrC. (C) Western blot of whole-cell lysates of 35000HP, 35000HPmtrC, 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC), FX517, and 35000HPΔcpxA probed with PAL-specific monoclonal antibody 3B9, as a loading control, and either DsrA-specific (top) or OmpP2B-specific (bottom) antibodies. The fold change in OmpP2B expression compared to the parent strain, after normalization to PAL, is indicated at the bottom. (D). Survival of 35000HP(pLSSK), FX517, 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK), and 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) in 50% normal human serum (NHS). The data represent the means and standard errors of three independent assays. The asterisks indicate significant differences from 35000HP(pLSSK) (P = 0.005).

DsrA is required for H. ducreyi survival in human serum (17). Because DsrA expression was undetectable in 35000HPmtrC, we tested the mtrC mutant for serum resistance. 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) was as sensitive as the dsrA mutant FX517 to serum-mediated killing and significantly more sensitive than wild-type 35000HP(pLSSK) (P = 0.005) (Fig. 3D). This serum-sensitive phenotype was fully complemented in 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) (Fig. 3D).

Deletion of mtrC in 35000HP activated the two-component regulator CpxRA system.

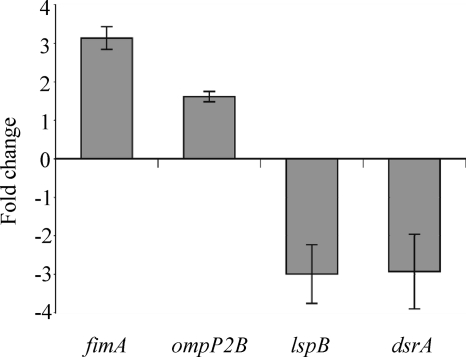

Recent studies showed that the CpxRA two-component regulator in H. ducreyi regulates expression of DsrA and OmpP2B (28, 48). Sequence analysis showed no changes in the predicted promoter regions for dsrA and ompP2B in 35000HPmtrC (data not shown). We thus hypothesized that the Cpx regulon is activated in the mtrC mutant. We tested this hypothesis by examining mRNA expression levels of selected Cpx-regulated genes, including dsrA, ompP2B, and two additional genes known to be either upregulated (HD0281) or downregulated (HD1155) by activation of CpxRA (28). HD0281 encodes the putative major fimbrial subunit FimA, and HD1155 encodes LspB, which is required for secretion of the antiphagocytic factors LspA1 and LspA2 (29, 52). qRT-PCR analysis showed that, relative to 35000HP, the mtrC mutant had increased transcriptional levels of fimA and ompP2B and decreased mRNA levels of lspB and dsrA (Fig. 4). These data confirmed that the CpxRA regulon was activated in 35000HPmtrC.

Fig. 4.

The CpxRA regulon is activated in 35000HPmtrC. qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of fimA, ompP2B, lspB, and dsrA in 35000HPmtrC compared with mRNA levels in 35000HP. The data represent means ± standard errors (n = 3).

We examined the colony morphology of 35000HPΔcpxA, in which the Cpx regulon is constitutively active, to determine whether CpxRA activation accounted for the altered morphology of 35000HPmtrC colonies (48). 35000HPΔcpxA had an intermediate phenotype between 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC (Fig. 3A, 4). Although colonies of 35000HPΔcpxA were translucent like those of 35000HPmtrC, the round shape and smooth surface were similar to the colonies of 35000HP. Thus, the colony morphology of 35000HPmtrC may be only partially attributable to activation of CpxRA.

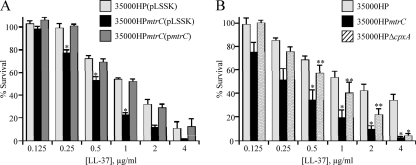

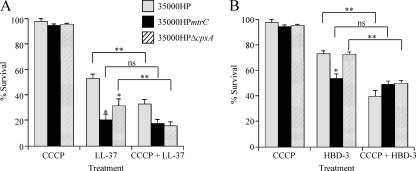

The MTR transporter contributes to LL-37 resistance.

To determine the role of the MTR transporter in AP resistance, we assayed 35000HP(pLSSK), 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK), and 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) for survival using a range of LL-37 concentrations. 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) was significantly more susceptible than 35000HP(pLSSK) to LL-37 at several concentrations (Fig. 5A). No significant difference was observed between the parent and the complemented mutant.

Fig. 5.

LL-37 resistance in H. ducreyi is affected by both MTR and the Cpx regulon. (A) Survival of 35000HP(pLSSK), 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK), and 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) exposed to the indicated concentrations of LL-37. (B) Comparison of sensitivities of 35000HP, 35000HPmtrC, and 35000HPΔcpxA to LL-37. The data represent the means and standard errors of at least three independent assays. The single asterisks indicate significant differences from the parent strain (P < 0.04); the double asterisks in panel B indicate significant differences between 35000HPmtrC and 35000HPΔcpxA (P < 0.05).

To assess the contribution of CpxRA activation to LL-37 sensitivity in the mtrC mutant, we tested 35000HPΔcpxA alongside 35000HP and 35000HPmtrC for susceptibility to LL-37. Both mutants were more sensitive than 35000HP to LL-37 at a concentration of 4 μg/ml (Fig. 5B); however, only the mtrC mutant was significantly more sensitive than the parent to LL-37 concentrations from 0.5 to 2 μg/ml. At these concentrations, the mtrC mutant was more sensitive than the cpxA mutant (Fig. 5B, double asterisks). 35000HPΔcpxR, in which the Cpx regulon is constitutively inactive (29), showed no significant difference from 35000HP in survival of LL-37 at concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 20 μg/ml (data not shown). Together, these data suggest that, although activation of CpxRA causes increased sensitivity to LL-37, the MTR transporter itself independently contributes to LL-37 resistance.

Because 35000HPΔcpxA exhibited increased sensitivity to LL-37 and we previously identified a role for the H. ducreyi Sap transporter in LL-37 resistance, we used qRT-PCR to determine whether sap gene expression was affected in the cpxA mutant. Both sapA, the first structural gene in the sap operon, and the genetically unlinked sapF were expressed at wild-type levels in 35000HPΔcpxA, with expression ratios of 0.9 ± 0.2 (mean ± standard error of 3 replicates) and 1.3 ± 0.3, respectively. Similarly, expression of mtrC was not affected by deletion of cpxA (1.1 ± 0.2). Thus, the increased sensitivity of 35000HPΔcpxA to LL-37 was not attributable to changes in expression of either the Sap or MTR transporter.

The MTR transporter contributes to β-defensin resistance.

We next tested 35000HPmtrC for susceptibility to human β-defensins. Compared with 35000HP(pLSSK), the mtrC mutant 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) showed significantly less survival when incubated with HBD-2, HBD-3, or HBD-4 (Fig. 6A to C). Of the β-defensins tested, HBD-3 exhibited the most potent activity against 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) (Fig. 6B). To determine the contribution of the Cpx regulon to β-defensin resistance in the mtrC mutant, we tested the HBD-3 sensitivities of 35000HPΔcpxA and 35000HPΔcpxR. Compared with 35000HP, the cpxR mutant showed no difference in sensitivity to HBD-3, and 35000HPΔcpxA showed no difference at HBD-3 concentrations of 0.2 to 2 μg per ml (Fig. 6D). At 20 μg HBD-3 per ml, there was a trend toward increased susceptibility of the cpxA mutant to HBD-3 (P = 0.08) (Fig. 6D). Taken together, the data suggest that the MTR transporter, rather than activation of the CpxRA system, is likely the major determinant of resistance to HBD-3 in H. ducreyi.

Fig. 6.

The MTR transporter contributes to β-defensin resistance in H. ducreyi. (A to C) Survival of 35000HP(pLSSK), 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK), and 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) exposed to the indicated concentrations of HBD-2 (A), HBD-3 (B), and HBD-4 (C). (D) Survival of 35000HP, 35000HPΔcpxA, and 35000HPΔcpxR exposed to HBD-3. The data represent the means and standard errors of at least three independent assays. The asterisks indicate significant differences from the parent strain (P < 0.05).

The MTR transporter has little effect on α-defensin resistance.

The susceptibility of 35000HP to HNP-2 was not affected when the proton motive force was dissipated with CCCP (data not shown), suggesting that the MTR system may not play a role in α-defensin resistance. We assayed the mtrC mutant for sensitivity to three α-defensins, HNP-1, HNP-2, and HD-5. At concentrations of 0.2 to 2 μg/ml, both the parent and mtrC mutant strains were fully resistant to all three α-defensins (data not shown). At a concentration of 20 μg/ml, the mtrC mutant showed 10 to 15% decreased survival against two α-defensins (Table 3). We also examined the susceptibility of 35000HPΔcpxA to HNP-1 and HNP-2 and found no increased sensitivity compared with 35000HP (Table 3 and data not shown). We concluded that the MTR transporter plays only a minor role in α-defensin resistance and that the CpxRA system does not appear to control a major mechanism of α-defensin resistance.

Table 3.

Effects of deleting mtrC or cpxA on H. ducreyi resistance to α-defensins

| Strain | % Survival with peptidea: |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HNP-1 | HNP-2 | HD-5 | |

| 35000HP(pLSSK) | 91.8 ± 6.4 | 90.8 ± 0.9 | 100.4 ± 3.2 |

| 35000HPmtrC(pLSSK) | 100.0 ± 8.0 | 74.0 ± 1.6b | 87.7 ± 2.4b |

| 35000HPmtrC(pmtrC) | 101.6 ± 5.9 | 93.0 ± 1.5 | 99.7 ± 2.8 |

| 35000HPΔcpxA | 97.3 ± 3.9 | 104.4 ± 5.6 | ND |

Percent survival when exposed to 20 μg/ml of the indicated peptide compared to control well with no AP. The data represent the means ± standard errors of at least three independent assays. ND, not determined.

Significant difference from 35000HP (P ≤ 0.05).

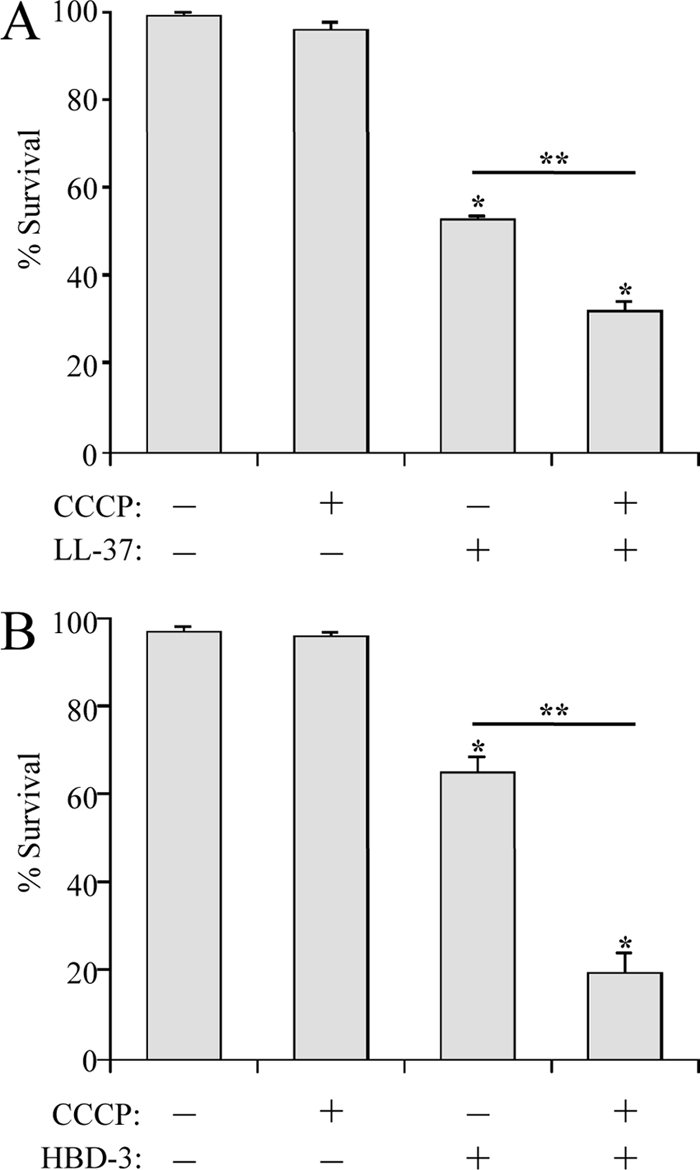

The MTR transporter confers PMF-dependent AP resistance in H. ducreyi.

Our AP susceptibility assays demonstrated that, while activation of the Cpx system may affect one or more AP resistance mechanisms, loss of MtrC had a greater effect on AP resistance than did loss of CpxA (Fig. 5 and 6). We next examined whether the mtrC or cpxA mutant retained the PMF-dependent AP resistance mechanism observed in 35000HP (Fig. 1). 35000HP, 35000HPmtrC, and 35000HPΔcpxA were treated with either DMSO alone or CCCP in DMSO, followed by either LL-37 (Fig. 7 A) or HBD-3 (Fig. 7B). As expected, CCCP pretreatment significantly enhanced the sensitivity of the parent strain to both APs. Similar results were obtained with 35000HPΔcpxA, indicating that Cpx-mediated AP resistance is not PMF dependent. In contrast, pretreatment with CCCP had no significant effect on the AP sensitivity of 35000HPmtrC (Fig. 7), indicating that, in H. ducreyi, the MTR transporter is likely the main AP resistance mechanism driven by the PMF.

Fig. 7.

Proton motive force dependence of mtrC- and cpxA-mediated AP resistance. Strains 35000HP, 35000HPmtrC, and 35000HPΔcpxA were pretreated with DMSO alone or CCCP in DMSO and challenged with LL-37 (2 μg/ml) (A) or HBD-3 (10 μg/ml) (B). The data represent the means and standard errors of 6 independent assays. The single asterisks indicate significant reductions in sensitivity compared with 35000HP (P < 0.03). The double asterisks indicate significant reductions in AP sensitivity with or without CCCP treatment for each strain (panel A, P < 0.001; panel B, P < 0.04). ns, not significant (P ≥ 0.05).

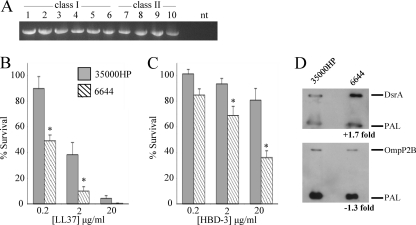

Characterization of the mtrC gene in class I and class II clinical isolates of H. ducreyi.

Clinical isolates of H. ducreyi fall into two phenotypic classes. To determine how widely conserved MTR is among isolates, we analyzed six class I and four class II strains of H. ducreyi for the mtrC gene. All strains exhibited a PCR-amplifiable band that comigrated with the mtrC PCR product of 35000HP (Fig. 8 A). Sequence analysis of the mtrC ORF for both the class I and class II strains revealed a high degree of homology between isolates. The mtrC ORFs from class I isolates HD183, HD188, and 85-023233 were identical to the 35000HP mtrC allele. However, the mtrC alleles in class I isolates 82-029362 and 6644 were identical to each other but contained a missense mutation and a 1-bp deletion that introduced a stop codon, truncating the predicted protein products to the N-terminal 271 amino acids (aa) of the 438-aa class I MtrC. All class II isolates contained identical mtrC alleles, which varied at 27 bp from the 35000HP mtrC allele, leading to a predicted full-length protein with 10 aa substitutions compared with MtrC from 35000HP.

Fig. 8.

Strain conservation of mtrC and LL-37 and HBD-3 resistance in H. ducreyi clinical isolate 6644. (A) PCR amplification of the mtrC ORF from class I and class II clinical isolates of H. ducreyi. A 1.602-kbp fragment was amplified from genomic DNA of each strain using primers flanking the mtrC ORF in 35000HP. Lanes 1 to 6 contain class I strains 35000HP, HD183, HD188, 82-029362, 6644, and HD85-023233, respectively; lanes 7 to 10 contain class II strains CIP542 ATCC, HMC112, 33921, and DMC164, respectively. nt, no template control. (B and C) Survival of 35000HP and 6644 exposed to the indicated concentrations of LL-37 (B) or HBD-3 (C). The data represent the means and standard errors of five independent assays. The asterisks indicate significant differences from 35000HP (P ≤ 0.04). (D) Western blot of whole-cell lysates of 35000HP and 6644 probed with PAL-specific monoclonal antibody 3B9, as a loading control, and either DsrA-specific (top) or OmpP2B-specific (bottom) antibodies. The fold change in DsrA and OmpP2B expression compared to 35000HP, after normalization to PAL, is indicated at the bottom.

We have previously shown that LL-37 and β-defensin resistance in the class II strain ATCC CIP542 is similar to that of 35000HP (34), suggesting that the class II mtrC allele is functional. The finding of a truncated mtrC allele in two class I clinical isolates raised the question of whether these isolates would exhibit increased sensitivity to APs and constitutive activation of CpxRA, as was observed in 35000HPmtrC. We therefore compared strain 6644 with 35000HP for LL-37 and HBD-3 resistance, serum resistance, and expression of CpxRA-regulated outer membrane proteins. Both strains were grown at 30°C with 10% CO2, which allowed propagation of 6644; strain 82-029362 did not grow sufficiently for use in these assays. Compared with 35000HP, strain 6644 was more sensitive to both LL-37 (Fig. 8B) and HBD-3 (Fig. 8C). We noted that 35000HP was slightly more resistant to HBD-3 than was seen in previous assays, which may be due to the modified growth conditions. To assay for CpxRA activation, we examined expression of DsrA and OmpP2B by Western blotting. Our results indicated that DsrA and OmpP2B were expressed at similar levels in 6644 and 35000HP (Fig. 8D). Interestingly, despite expression of DsrA, 6644 was significantly more sensitive to killing by human serum than 35000HP (P = 0.03; data not shown). Collectively, the phenotypes of the naturally occurring mtrC mutant 6644 are consistent with loss of MTR-mediated AP resistance but are not consistent with activation of the CpxRA regulon.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we defined a PMF-dependent mechanism of AP resistance in H. ducreyi. CCCP acts as a proton uncoupler that can inhibit transporters, such as the RND, major facilitator superfamily (MFS), and multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) families (31). Our data show that H. ducreyi utilizes a PMF-dependent mechanism for LL-37 and HBD-3 resistance, but not for resistance to α-defensin HNP-2. Experiments by Shafer et al. showed a similar response for N. gonorrhoeae exposed to AP and CCCP, and the major contributor to this phenotype was the MTR transporter (46). We identified an H. ducreyi homolog of MTR and inactivated the transporter by deletion of mtrC. Although the loss of mtrC activated the CpxRA regulon, the mtrC mutant was more sensitive than a cpxA mutant to LL-37 and HBD-3. Addition of CCCP to the mtrC mutant did not affect AP resistance, indicating that the mutant had lost the PMF-dependent AP resistance mechanism. In contrast, exposure to CCCP increased the sensitivity of a cpxA mutant to APs, indicating that the cpxA mutant retained PMF-dependent AP resistance. These data demonstrate that the PMF-dependent AP resistance in H. ducreyi is mediated by the MTR homolog.

The MTR transporter in H. ducreyi was identified by homology searches of the genome for RND efflux transporter genes. In N. gonorrhoeae, genes encoding the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux transporter lie in a single operon, which is under the control of regulatory proteins MtrA and MtrR (22, 32, 42). Homology searches of the H. ducreyi genome did not reveal homologs of these regulators. The H. ducreyi MTR system is encoded in two chromosomal loci: the mtrCD genes (HD1513-HD1512) are found in one operon, while the putative outer membrane component mtrE (HD1829) is genetically unlinked. This genetic organization is common to many tripartite efflux transporters in Gram-negative bacteria, as the outer membrane component, a NodT-MtrE-TolC family member, often interacts with more than one inner membrane transporter (11, 26, 33, 37, 40). A genomic search in H. ducreyi for additional transporters revealed homologs of the inner membrane and periplasmic components of the tripartite macrolide-specific pump MacAB (HD1018-HD1019) (43). Although the inner membrane pump, MacB, is energized by ATP hydrolysis rather than the PMF, MacA and MacB complex with a NodT-MtrE-TolC family outer membrane channel for efflux of substrates; thus, the predicted outer membrane channel component MtrE (HD1829) could interact with two efflux pumps.

Deletion of mtrC in H. ducreyi yielded several phenotypic changes, including alterations in colony morphology, OMP expression profiles, and serum sensitivity. Each phenotype was fully complemented in trans by the intact mtrC gene (Fig. 3), confirming that the phenotypic changes were not due to secondary mutations in 35000HPmtrC. Rather, our data show that mutation of mtrC activated the two-component CpxRA system. In other organisms, the CpxRA system is activated in response to envelope stress, although its trigger in H. ducreyi is unclear (28, 39, 48). Transcriptional changes and altered phenotypes have been reported in other bacteria when RND transporters are disrupted. Deletion of individual genes encoding the AcrA-AcrB-TolC pump in Salmonella enterica led to global changes in gene expression, including changes in virulence factor expression; the regulatory basis for these transcriptional changes is not known (53). Loss of the outer membrane channel TolC led to increased expression of several regulatory genes in E. coli (41), and the CpxRA system in Sinorhizobium meliloti was activated by mutagenesis of tolC (44). Rosner and Martin postulated that the effects of inactivating TolC are due to intracellular accumulation of metabolic products normally secreted through the TolC channel, although specific metabolites were not identified (41). In the case of H. ducreyi, the organism likely utilizes the MTR transporter to export metabolic waste products, in addition to harmful compounds, such as APs, from the host environment. We propose that, without MtrC, the MtrD pump remains active but uncoupled from MtrE, leading to an accumulation of metabolic products in the periplasm, which subsequently induces envelope stress and activates CpxRA.

The mtrC mutant is more sensitive than the parent strain to cathelicidin and β-defensin classes of human APs. Because the CpxRA system was activated in the mtrC mutant, we examined the AP resistance phenotype of cpxA and cpxR mutants in order to determine the contributions of MTR and the Cpx system to the AP resistance phenotype of 35000HPmtrC. Inactivation of cpxR had no effect on AP resistance (Fig. 6D and data not shown). Deletion of cpxA led to reduced resistance against LL-37 (Fig. 5B, 7A) but had little effect on HBD-3 resistance (Fig. 6D and 7B), suggesting that the CpxRA system may affect the expression of a mechanism for resistance to LL-37 but likely does not play a major role in β-defensin resistance. When assayed side by side, the mtrC mutant was significantly less resistant than the cpxA mutant to LL-37 (Fig. 5B), suggesting that the loss of MTR likely plays a larger role than Cpx activation in the increased LL-37 resistance phenotype of 35000HPmtrC. A distinction between MTR-mediated and CpxRA-mediated AP resistance was also observed by addition of the PMF uncoupler CCCP to AP sensitivity assays (Fig. 7). While the cpxA mutant responded to loss of PMF by becoming more sensitive to LL-37 and HBD-3, CCCP had no effect on the AP sensitivity of the mtrC mutant, demonstrating that the mtrC mutant, but not the cpxA mutant, had lost the PMF-dependent AP resistance mechanism. We thus conclude that the H. ducreyi MTR transporter itself confers resistance to LL-37 and β-defensins.

It is unclear how the CpxRA system affects LL-37 resistance in H. ducreyi. We had previously identified the Sap transporter as a virulence factor reducing sensitivity to LL-37 (35). In the current study, we identified the MTR transporter as a second mechanism of LL-37 resistance. By qRT-PCR, we found no change in expression of sap genes or mtrC in the cpxA mutant, suggesting that neither transporter is under CpxRA control. Interestingly, Labandeira-Rey et al. reported microarray analysis showing that HD1513-HD1511, encoding mtrCD and glmU, were upregulated in a cpxA mutant (28). Although the microarray data were confirmed by performing qRT-PCR on several genes, HD1511-HD1513 were not among those selected for qRT-PCR confirmation (28). The reason for the discrepancy in cpxA-mediated effects on mtrC expression is uncertain, but it could be due to the different cpxA mutants or growth conditions used in the two studies. Our results showing that expression of the mtr genes is not affected by CpxRA are consistent with the differences in AP resistance observed for 35000HPmtrC and 35000HPΔcpxA (Fig. 5 to 7). Thus, the CpxRA regulon may include an additional, unidentified mechanism of LL-37 resistance.

The structural requirements of substrates for MTR have not been determined. In N. gonorrhoeae, MTR transports a wide variety of substrates, including LL-37, antibiotics, dyes, and detergents; the common theme among these diverse substrates is their hydrophobic nature (22, 46). In the present study, we defined two substrates of the H. ducreyi MTR transporter: β-defensins and LL-37. β-Defensins have 6 cysteines and form 3 intramolecular disulfide bonds; these APs are characterized by a triple β-strand structure (20). In contrast, LL-37 is cysteine free and forms a linear α-helix (16). Both have hydrophobic components, which may be the common requirement for MTR-mediated transport. Interestingly, we found little MTR activity against α-defensins, which are somewhat smaller but very similar both structurally and in hydrophobicity to the β-defensins (19, 20). It is possible that MTR transports α-defensins but that the phenotype is masked by other resistance mechanisms or by a lesser potency of α-defensins than of β-defensins. Our data suggest that MTR may exhibit an effect on α-defensins at higher concentrations than those used in our assays (Table 3). The physiologically relevant concentration of these APs is difficult to discern in vivo. In PMN granules, α-defensins attain mg per ml concentrations (30); however, AP concentrations likely decline significantly upon release into the extracellular milieu, where H. ducreyi is most likely to encounter the APs. Estimates of extracellular AP concentrations in human tissues vary extensively among studies, with vaginal concentrations of HNP-1 to -3 ranging from 0.2 μg per ml (45) to 3 μg per ml (5) and an estimated 60 to 110 μg of HD5 per ml (18); urethral concentrations of HD5 were estimated at 0.5 to 18 μg per ml (38). The concentration range used in our assays covers most estimates of physiologically relevant doses.

Although the mtrC gene is conserved in both class I and class II strains of H. ducreyi, the mtrC allele in two class I strains contains a 1-bp deletion in a run of A residues and is predicted to produce a truncated MtrC protein. As the C-terminal domain of membrane fusion proteins is likely required for proper assembly and function of RND transporters (21), the H. ducreyi strains with truncated mtrC genes likely produce inactive transporters. Consistent with this model, strain 6644, which carries the naturally occurring mtrC mutation, showed increased sensitivity to LL-37 and HBD-3 compared with 35000HP, mirroring our findings with the engineered mtrC deletion. Due to poor growth, we were not able to test the AP susceptibility of 82-029362, the other isolate harboring the natural mtrC mutation. The lack of a functional MTR system in two H. ducreyi isolates might indicate that the transporter is dispensable for virulence. However, unlike 35000HP, the passage history of these two isolates and whether they have retained the ability to infect humans is unknown. Based on expression levels of the outer membrane proteins DsrA and OmpP2B, strain 6644 did not display the CpxRA activation phenotype observed in 35000HP. Whether the CpxRA system is conserved in these isolates and whether Cpx regulates the same virulence factors in other strains as in 35000HP is unknown. More detailed genomic studies of 6644 and other clinical isolates of H. ducreyi are needed to resolve these questions.

In summary, we have shown that the MTR transporter in H. ducreyi promotes resistance to LL-37 and human β-defensins in a PMF-dependent manner. The MTR transporter is the first mechanism of β-defensin resistance identified in H. ducreyi. In addition, we showed that deletion of the mtrC gene activates the CpxRA regulon, which may also contribute to LL-37 resistance. We did not test the mtrC mutant in the human model of H. ducreyi infection because activation of the CpxRA regulon has already been shown to lead to attenuation in vivo (48), and it would not be possible to separate the roles of CpxRA and the MTR transporter in virulence studies with 35000HPmtrC. Future studies will include attempts to inactivate the MTR transporter without activating the CpxRA system and identification of the CpxRA-regulated LL-37 resistance mechanism.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stan Spinola and Eric Hansen for providing H. ducreyi strains 35000HPΔcpxA and 35000HPΔcpxR, respectively. We thank Bob Munson, Jr., for providing strains, plasmids, and protocols for adapting “recombineering” to H. ducreyi, and we thank Beth Baker for her invaluable technical advice on the “recombineering” and mutagenesis protocols. We thank Stan Spinola and Frank Yang for helpful discussions and review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R21 AI075008 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Developmental Awards Program of the NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Sexually Transmitted Infections and Topical Microbicide Cooperative Research Centers grants to the University of Washington (AI 31448) and Indiana University (AI 31494), the Ralph W. and Grace M. Showalter Research Trust Fund, and an Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis Research Support Funds Grant. S.D.R. was supported by fellowships from NIH (grants T32 AI007637 and T32 AI060519).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 March 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdullah M., et al. 2005. Killing of dsrA mutants of Haemophilus ducreyi by normal human serum occurs via the classical complement pathway and is initiated by immunoglobulin M binding. Infect. Immun. 73:3431–3439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abramoff M. D., Magelhaes P. J., Ram S. J. 2004. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 11:36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al-Tawfiq J. A., et al. 1998. Standardization of the experimental model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection in human subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1684–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andersen C. 2003. Channel-tunnels: outer membrane components of type I secretion systems and multidrug efflux pumps of gram-negative bacteria. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 147:122–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balu R. B., et al. 2002. Bacterial vaginosis and vaginal fluid defensins during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 187:1267–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banks K. E., et al. 2008. The enterobacterial common antigen-like gene cluster of Haemophilus ducreyi contributes to virulence in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1531–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bauer M. E., Goheen M. P., Townsend C. A., Spinola S. M. 2001. Haemophilus ducreyi associates with phagocytes, collagen, and fibrin and remains extracellular throughout infection of human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 69:2549–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bauer M. E., Spinola S. M. 2000. Localization of Haemophilus ducreyi at the pustular stage of disease in the human model of infection. Infect. Immun. 68:2309–2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauer M. E., et al. 2009. A fibrinogen-binding lipoprotein contributes to the virulence of Haemophilus ducreyi in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 199:684–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bauer M. E., Townsend C. A., Ronald A. R., Spinola S. M. 2006. Localization of Haemophilus ducreyi in naturally acquired chancroidal ulcers. Microbes Infect. 8:2465–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bina X. R., Provenzano D., Nguyen N., Bina J. E. 2008. Vibrio cholerae RND family efflux systems are required for antimicrobial resistance, optimal virulence factor production, and colonization of the infant mouse small intestine. Infect. Immun. 76:3595–3605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bozue J. A., Tarantino L., Munson R. S., Jr 1998. Facile construction of mutations in Haemophilus ducreyi using lacZ as a counter-selectable marker. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164:269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Braff M. H., Gallo R. L. 2006. Antimicrobial peptides: an essential component of the skin defensive barrier. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 306:91–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brogden K. A. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:238–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deneer H. G., Slaney L., Maclean I. W., Albritton W. L. 1982. Mobilization of nonconjugative antibiotic resistance plasmids in Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Bacteriol. 149:726–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Smet K., Contreras R. 2005. Human antimicrobial peptides: defensins, cathelicidins and histatins. Biotechnol. Lett. 27:1337–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Elkins C., Morrow K. J., Olsen B. 2000. Serum resistance in Haemophilus ducreyi requires outer membrane protein DsrA. Infect. Immun. 68:1608–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan S., Liu X., Liao Q. 2008. Human defensins and cytokines in vaginal lavage fluid of women with bacterial vaginosis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 103:50–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ganz T. 2005. Defensins and other antimicrobial peptides: a historical perspective and an update. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 8:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ganz T. 2003. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:710–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge Q., Yamada Y., Zgurskaya H. 2009. The C-terminal domain of AcrA is essential for the assembly and function of the multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC. J. Bacteriol. 191:4365–4371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hagman K. E., et al. 1995. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antimicrobial hydrophobic agents is modulated by the mtrRCDE efflux system. Microbiology 141:611–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hammond G. W., Lian C. J., Wilt J. C., Ronald A. R. 1978. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 13:608–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janowicz D. M., et al. 2004. Expression of the LspA1 and LspA2 proteins by Haemophilus ducreyi is required for virulence in human volunteers. Infect. Immun. 72:4528–4533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jenssen H., Hamill P., Hancock R. E. 2006. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:491–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koronakis V., Eswaran J., Hughes C. 2004. Structure and function of TolC: the bacterial exit duct for proteins and drugs. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73:467–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kraus D., Peschel A. 2006. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial resistance to anticmicrobial peptides. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 306:231–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Labandeira-Rey M., Brautigam C. A., Hansen E. J. 2010. Characterization of the CpxRA regulon in Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 78:4779–4791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Labandeira-Rey M., Mock J. R., Hansen E. J. 2009. Regulation of expression of the Haemophilus ducreyi LspB and LspA2 proteins by CpxR. Infect. Immun. 77:3402–3411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lehrer R. I., Lichtenstein A. K., Ganz T. 1993. Defensins: antimicrobial and cytotoxic peptides of mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11:105–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li W., Janowicz D. M., Fortney K. R., Katz B. P., Spinola S. M. 2009. Mechanism of human natural killer cell activation by Haemophilus ducreyi. J. Infect. Dis. 200:590–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lucas C. E. J., Hagman K. E., Levin J. C., Stein D. C., Shafer W. M. 1995. Importance of lipooligosaccharide structure in determining gonococcal resistance to hydrophobic antimicrobial agents resulting from the mtr efflux system. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1001–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matsuo T., et al. 2007. VmeAB and RND-type multidrug efflux transporter in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Microbiology 153:4129–4137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mount K. L. B., Townsend C. A., Bauer M. E. 2007. Haemophilus ducreyi is resistant to human antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3391–3393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mount K. L. B., et al. 2010. Haemophilus ducreyi SapA contributes to cathelicidin resistance and virulence in humans. Infect. Immun. 78:1176–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pfaffl M. W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantitation in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Plebanski M., et al. 1999. Interleukin10-mediated immunosuppression by a variant CD4 T cell epitope of Plasmodium falciparum. Immunity 10:651–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Porter E., et al. 2005. Distinct defensin profiles in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis reveal novel epithelial cell-neutrophil interactions. Infect. Immun. 73:4823–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raivio T. L. 2005. Envelope stress responses and Gram-negative bcterial pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 56:1119–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rivilla R., Sutton J. M., Downie J. A. 1995. Rhizobium leguminosarum NodT is related to a family of outer-membrane transport proteins that includes TolC, PrtF, CyaE and AprF. Gene 161:27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rosner J. L., Martin R. G. 2009. An excretory function for the Escherichia coli outer membrane pore TolC: upregulation of marA and soxS transcription and Rob activity due to metabolites accumulated in tolC mutants. J. Bacteriol. 191:5283–5292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rouquette C., Harmon J. B., Shafer W. M. 1999. Induction of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires MtrA, an AraC-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 33:651–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rouquette-Loughlin C. E., Balthazar J. T., Shafer W. M. 2005. Characterization of the MacA-MacB efflux system in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:856–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santos M. R., Cosme A. M., Medeiros J. M. C., Fata M. F., Moreira L. M. 2010. Absence of functional TolC protein causes increased stress response gene expression in Sinorhizobium meliloti. BMC Microbiol. 10:180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sawada M., et al. 2006. Cervical inflammatory cytokines and other markers in the cervical mucus of pregnant women with lower genital tract infection. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 92:117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shafer W. M., Qu X.-D., Waring A. J., Lehrer R. I. 1998. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:1829–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Spinola S. M. 2008. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi, p. 689–699 In Holmes K. K., et al. (ed.), Sexually transmitted diseases, 4th ed McGraw-Hill, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 48. Spinola S. M., et al. 2010. Activation of the CpxRA system by deletion of cpxA impairs the ability of Haemophilus ducreyi to infect humans. Infect. Immun. 78:3898–3904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Spinola S. M., Griffiths G. E., Bogdan J. A., Menegus M. A. 1992. Characterization of an 18,000 molecular-weight outer membrane protein of Haemophilus ducreyi that contains a conserved surface-exposed epitope. Infect. Immun. 60:385–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tracy E., Ye F., Baker B. D., Munson Jr R. S. 2008. Construction of non-polar mutants in Haemophilus influenzae using FLP recombinase technology. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:101–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trees D. L., Morse S. A. 1995. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi: an update. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:357–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ward C. K., Mock J. R., Hansen E. J. 2004. The LspB protein is involved in the secretion of the LspA1 and LspA2 proteins by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect. Immun. 72:1874–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Webber M. A., et al. 2009. The global consequence of disruption of the AcrAB-TolC efflux pump in Salmonella enerica includes reduced expression of SPI-I and other attributes required to infect the host. J. Bacteriol. 191:4276–4285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. White C. D., et al. 2005. Haemophilus ducreyi outer membrane determinants, including DsrA, define two clonal populations. Infect. Immun. 73:2387–2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wood G. E., Dutro S. M., Totten P. A. 1999. Target cell range of Haemophilus ducreyi hemolysin and its involvement in invasion of human epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:3740–3749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]