Abstract

The G1 phase of the cell cycle is an important integrator of internal and external cues, allowing a cell to decide whether to proliferate, differentiate, or die. Multiple protein kinases, among them the cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks), control G1-phase progression and S-phase entry. With the regulation of apoptosis, centrosome duplication, and mitotic chromosome alignment downstream of the HIPPO pathway components MST1 and MST2, mammalian NDR kinases have been implicated to function in cell cycle-dependent processes. Although they are well characterized in terms of biochemical regulation and upstream signaling pathways, signaling mechanisms downstream of mammalian NDR kinases remain largely unknown. We identify here a role for human NDR in regulating the G1/S transition. In G1 phase, NDR kinases are activated by a third MST kinase (MST3). Significantly, interfering with NDR and MST3 kinase expression results in G1 arrest and subsequent proliferation defects. Furthermore, we describe the first downstream signaling mechanisms by which NDR kinases regulate cell cycle progression. Our findings suggest that NDR kinases control protein stability of the cyclin-Cdk inhibitor protein p21 by direct phosphorylation. These findings establish a novel MST3-NDR-p21 axis as an important regulator of G1/S progression of mammalian cells.

INTRODUCTION

The G1 phase of the cell cycle is a crucial integrator of internal and external cues, allowing cells to grow, process outside information, or repair damage before entering S phase (32). Entry into S phase is mediated by the action of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdk) complexed with their respective cyclin subunits. Initially cyclin D-Cdk4/6 and later cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes phosphorylate the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor protein, allowing dissociation of Rb from E2F transcription factors and subsequent transcription of genes required for S phase entry (17). The activity of Cdks is controlled on multiple levels (44). The association of Cdks with cyclin subunits is a prerequisite for Cdk activation. This process is initially controlled by the availability of the cyclin subunit, whose abundance is regulated by both transcriptional and posttranscriptional processes (44). Furthermore, cyclin-Cdk inhibitor (CKI) proteins of the Cip/Kip (e.g., p21 and p27) and INK4 (e.g., p16) families control cyclin-Cdk activity by different mechanisms. Cip/Kip proteins associate with and inhibit cyclin E-Cdk2 complexes, and INK4 proteins inhibit cyclin D-dependent Cdks by sequestering Cdk4/6 into binary Cdk-INK4 complexes, thereby blocking assembly of active cyclin D-Cdk4/6 complexes. Multiple signaling pathways have been shown to directly or indirectly affect the activity of cyclin-Cdk complexes, thereby controlling the G1/S transition. Since the correct regulation of the G1/S transition is essential for mammalian cells, much research has been invested in understanding this process. However, investigations of the complex regulation of Cdk activity are still needed.

Members of the nuclear-Dbf2-related (NDR) family of Ser/Thr kinases are highly conserved from yeast to human and have been implicated in the regulation of a variety of biological processes (24). NDR family kinases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have distinct roles in the regulation of mitotic exit by Dbf2p (38, 51) and the control of polarized cell growth by Cbk1p (3, 53). Similarly, in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Sid2p has a role in cytokinesis (16) and Orb6p functions in cell polarity and morphogenesis (11, 25). In Drosophila melanogaster the roles of NDR kinases also differ substantially. Warts regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis (26), and tricornered regulates cell morphogenesis and dendritic tiling (13, 18). These findings indicate that two distinct branches of NDR signaling exist across species. Nevertheless, in a subset of those functions NDR kinases in yeast and flies can function cooperatively (14, 40). With the regulation of mitotic exit, cell growth, proliferation, centrosome duplication, and morphogenesis, NDR family kinases across species have been shown to function in processes tightly linked to the cell cycle (24). The human genome encodes for four different NDR kinase family members, NDR1/2 and LATS1/2 (20). The kinases LATS1/2 function as part of the HIPPO pathway controlling the localization and function of the YAP oncogene (56). Furthermore, roles for LATS1 and LATS2 in controlling mitotic exit and genomic stability have been described (4, 34). Although they are well characterized in terms of biochemical regulation, functions for the other two NDR family kinases in the human genome, NDR1 and NDR2, have only recently started to be unraveled. In cellular systems, NDR kinases have been implicated in the regulation of centrosome duplication, apoptosis, and the alignment of mitotic chromosomes (7, 23, 50). Furthermore, a recent study indicated a tumor-suppressive function, by controlling proper apoptotic responses, for NDR1/2 in mice (10). NDR1/2 activity is regulated by phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif (HM) through the mammalian Ste20-like kinases MST1, MST2, and MST3 (7, 22, 47, 50). Whereas NDR kinase activation during apoptosis and centrosome duplication is mediated by MST1 (22, 50), MST2 regulates NDR in the context of mitotic chromosome alignment (7). However, the functional context of NDR kinase activation by MST3 has not been reported so far. Furthermore, although functions and regulators of NDR1/2 were defined recently, downstream signaling remained elusive. Here we addressed NDR1/2 activation throughout the cell cycle. We show that NDR1/2 are selectively activated in G1 phase by MST3, establishing the first functional context for NDR kinase regulation by MST3. More importantly, with the direct regulation of p21 stability by phosphorylation on Ser 146, we define here the first downstream signaling mechanisms by which NDR kinases can control G1/S progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids.

The construction of plasmids encoding cDNAs and retroviral constructs for tagged variants of NDR1, NDR2, MST1, MST2, and MST3 has been described elsewhere (19, 22, 50). RNA interference (RNAi) rescue constructs for NDR2 were obtained by introducing silent mutations into the short hairpin RNA (shRNA) target sites using PCR mutagenesis. For constructs expressing cDNAs fused to an internal ribosome entry site-green fluorescent protein (IRES-GFP), the IRES-GFP cassette was excised from the pMIG-vector using XhoI/SalI digestion and inserted into pcDNA3 containing the indicated cDNAs using XhoI. Constructs for pGEX2T-GSTp21, pcDNA3-p21, and pcDNA-myc-p21 were obtained by PCR cloning attaching BamHI/XhoI sites to p21-cDNA (a kind gift from N. Lamb, Institut de Génétique Humaine, Montpellier, France) and insertion into the BamHI/XhoI sites of the respective vector. Mutation of T145, S146, and T145/S146 to alanine was done by PCR mutagenesis. cDNA encoding c-myc was a kind gift from N. Hynes (Friedrich Miescher Institute, Basel, Switzerland), and hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged c-myc was obtained similarly to myc-p21 by PCR cloning into a pcDNA3-HA vector. HA-tagged variants of c-myc containing only the first 215 amino acids (c-myc-ΔC) or the last 234 amino acids (c-myc-ΔN) were obtained by PCR cloning. Deletion of the MB1 or MB2 domain was performed by PCR mutagenesis. Primer sequences are available upon request. Vectors encoding cDNA for FBW7 or ubiquitin (Ub) were kind gifts from B. Clurman (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) and W. Filipowicz (Friedrich Miescher Institute, Basel, Switzerland). For production of recombinant protein, kinase-dead NDR1 (NDR1kd) (K118R) cDNA was cloned in the pMal-C2 vector.

Cell culture, transfections, and treatments.

All cell lines used in this study were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were transfected using Fugene 6 (Roche), Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), or jetPEI (Polyplus Transfection) as described by the manufacturer. For small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of MST1, MST2, MST3, or p21, cells were transfected with predesigned siRNA (Qiagen) using Lipofectamine 2000. For si_p21-mediated rescue experiments, cells were transfected twice at 24-h intervals. HeLa cells expressing tetracycline (TET)-inducible shRNA against NDR1 and NDR2 and U2OS cells stably expressing shRNA against NDR1 together with a wild-type NDR1 (NDR1wt) rescue construct have been described elsewhere (23, 50). HeLa and U2OS cells stably expressing shRNA against NDR1 or NDR2 alone were generated as described previously (23, 50). To determine protein stability, cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) or 10 μM MG132.

Reagents and antibodies.

The generation of antibodies against T444-P, NDR1, NDR2, and NDR1/2 has been described previously (50). Antibodies against cyclin A, cyclin E, cyclin B1, cdc2, p27, GFP, c-myc (N262), HA (Y11), and actin were from Santa Cruz. Antibodies to detect p21, cyclin D1, Cdk4, MST1, MST2, MST3, and myc-tagged proteins (71D10) were from Cell Signaling. Antibodies against HA tag (12CA5 and 42F13), tubulin (YL1/2), and c-myc (9E10) were used as hybridoma supernatants. Additional antibodies used included anti-p21-pS146 (Abgent), anti-P-MST4-T178/-MST3-T190/-STK25-T174 (referred to as P-MST3) (Epitomics), anti-MST3 (BD Biosciences), and anti-FLAG (M2) (Sigma). Nocodazole, thymidine, propidium iodide (PI), and cycloheximide were from Sigma. Okadaic acid (OA), SB203580, and SB202190 were from Alexis (Enzo Life Sciences). MG132 was from Calbiotech. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and anti-BrdU antibody were from BD Biosciences.

Protein extraction, immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and ubiquitination analysis.

Protein extraction from cultured cells, immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting were done as described previously (19). The following antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation: anti-HA (12CA5), anti-c-myc (9E10 and N262), anti-p21, anti-MST3, and a mixture of NDR1- and NDR2-specific antibodies to assess endogenous NDR species. For quantification using the Li-Cor Odyssey system, Western blots were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescent dyes. Quantifications were carried out using the Li-Cor Odyssey software. Analysis of c-myc ubiquitination was performed as described previously (41).

Cell cycle analysis.

HeLa and HeLa S3 cells were synchronized using either a double thymidine block with subsequent nocodazole arrest and mitotic shake-off (48) or a single treatment with 100 ng/ml nocodazole for 14 h. Cells were washed free of nocodazole with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and released into fresh medium for the indicated times before harvesting. Cell cycle distribution was assessed using either BrdU labeling as described by the manufacturer or PI staining as described previously (23). To detect cells blocked in G1, a method described by Mikule et al. was used (35). In short, cells were seeded at defined densities into 10-cm dishes, and 24 h later 2.5 μg/ml nocodazole was added and left for 14 to 16 h to terminally arrest cells at the G2/M border. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and processed for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Kinase assays.

Methods to determine the activity of endogenous NDR kinases have been described earlier (50). To assay p21 phosphorylation by NDR1/2 in vitro, HEK293 cells were transfected with cDNAs encoding HA-tagged NDR kinase isoforms and mutants. Cells were stimulated with 1 μM okadaic acid for 60 h prior to lysis and immunoprecipitation. In vitro kinase assays using purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged p21 isoforms were performed as described previously (19) with minor modifications. Before addition of [γ-32P]ATP and GST-p21, the immunoprecipitated kinases were preincubated for 90 min at 30°C in reaction buffer without 32P-labeled ATP. The labeling reaction was stopped after 60 min by boiling the samples in sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C. Samples were resolved on SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie blue, and exposed to a phosphorimager (Amersham Biosciences). Kinase activity of endogenous MST3 species was assessed by immunoprecipitation of endogenous MST3 and by using recombinant maltose binding protein (MBP)-tagged NDR1 K118R as a substrate in an in vitro kinase assay as described earlier (47).

Proliferation assays.

For the analysis of cell proliferation, cells were seeded at defined densities in triplicates. For experiments including inducible shRNAs, fresh tetracycline was added each day, starting with cell seeding. After the indicated times, cells were harvested by trypsinization and counted using a ViCell-XR automated cell counter (Beckman Coulter). The decrease in proliferation of HeLa shNDR1/2 cells with or without TET was calculated using the formula y = 100 × (cell count on day 6 with TET)/(cell count on day 6 without TET). The result represents the mean of triplicates for three different clones.

RNA isolation, quantitative real-time PCR, and luciferase assays.

Total RNA from cells was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and further purified using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was generated from 2 μg of total RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (NEB) and oligo(dT) primers. Quantitative RT-PCR to detect p21, p27, and c-myc (primer sequences are available upon request) was carried out using SYBR green technology in an ABI Prism 7000 detection system (Applied Biosystems). Luciferase assays using the wild-type (LDH-WT) or E-box-mutated (LDH-MT) version of the LDA-H promoter (a kind gift from C. V. Dang, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (45) were performed using the dual-luciferase reporter assay from Promega.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with Student's t test for the comparison between two samples.

RESULTS

NDR kinases are activated in G1 by MST3.

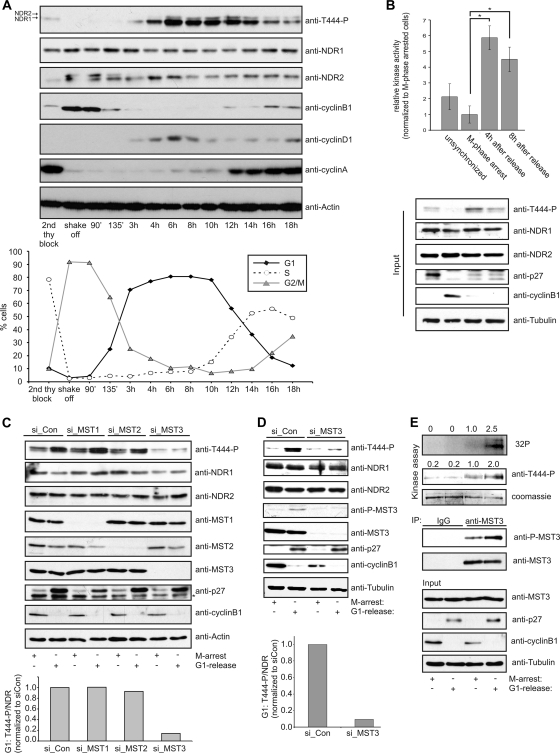

Mammalian NDR kinases are implicated in the regulation of cell cycle-dependent processes such as centrosome duplication and the alignment of mitotic chromosomes (7, 22). To better define the cell cycle function(s) of NDR kinases, we analyzed NDR kinase activity during cell cycle progression. Hydrophobic motif (HM) phosphorylation of NDR1 and NDR2, as an indicator of NDR kinase activity (47), was nearly absent in M phase, increased 3 h after mitotic shake-off upon entry into G1 phase, and peaked at around 6 to 8 h in G1 phase. Activation of NDR persisted into S phase (12 to 14 h) and started to decrease 14 h after shake-off (Fig. 1A). Analysis of cell cycle markers by immunoblotting and FACS staining of the cell population (visualized by a plotted graph) confirmed that NDR activation peaked in G1 phase with the activation persisting into S phase. G1 activation of NDR1/2 was confirmed by analyzing endogenous NDR1/2 activity using a peptide kinase assay (Fig. 1B). Since three members of the mammalian Ste20-like kinases (MST1/2/3) can regulate NDR kinases by phosphorylation of the HM of NDR (7, 22, 47, 50), we tested which MST kinase was important for NDR1/2 activation in G1. To this end, we analyzed NDR phosphorylation in G1 upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of MST1 to -3 (Fig. 1C). Although depletion of MST1 and MST2 hardly affected NDR activation, knockdown of MST3 expression significantly reduced NDR phosphorylation in this setting. This finding was confirmed using overexpression of dominant negative (DN) variants of MST1 to -3 (data not shown), suggesting that MST3 is the main upstream kinase in this cell cycle phase. Interestingly, we observed an increase in phosphorylated MST3 in G1-phase cells versus M-phase-arrested cells, indicating that MST3 activity is increased in G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 1D). We then addressed whether increased MST3 phosphorylation reflected an increase in kinase activity. Endogenous MST3 kinase was immunoprecipitated in cells arrested in M phase or released into G1 phase. The increase in phosphorylation of MST3 in G1 was paralleled by approximately 2-fold-increased kinase activity when an in vitro kinase assay on kinase-dead NDR1 (MBP-NDR1 K118R) was performed (Fig. 1E), therefore demonstrating that kinase activity of MST3 is increased in G1. Collectively, these results revealed that NDR kinases were activated in G1 phase of the cell cycle, with the activation persisting into S phase. Furthermore, our experiments revealed MST3 as the responsible upstream kinase for NDR1/2 in this setting, thereby providing the first functional link between NDR1/2 and MST3.

Fig. 1.

NDR kinases are activated by MST3 in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. (A) NDR kinases are activated in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Synchronized HeLa S3 cells were harvested after mitotic shake-off and replated in fresh medium for the indicated times. Activation of NDR1/2 was assessed using anti-T444-P, -NDR1, and -NDR2 antibodies. Cell cycle distribution was assessed using propidium iodide (PI) staining and FACS analysis. (B) Endogenous NDR kinase activity is increased in G1 phase. HeLa cells were arrested at the G2/M border using nocodazole treatment for 14 h and released for the indicated times before harvesting. Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation of endogenous NDR species using a mixture of isoform-specific antibodies. NDR kinase activity was assessed using peptide kinase assays (n = 3; P < 0.002). (C) Depletion of MST1/2/3 kinases using isoform-specific siRNAs. HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (si_Con) or siRNAs targeting MST1/2/3 kinases (si_MST1, si_MST2, and si_MST3) and 48 h later were arrested with nocodazole for 14 h. Arrested cells were harvested or released into G1 for 8 h before harvesting. NDR activation was assessed using T444-P antibody. Cell cycle phases were confirmed by analyzing cyclin B1 and p27 expression (*, unspecific band). Phospho-T444 levels after G1 release were compared to those in control samples and analyzed using the Li-Cor Odyssey system. (D) Reduction of MST3 impairs G1 activation of NDR. HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (si_Con) or siRNA against MST3 (si_MST3) and treated and analyzed as described for panel C. MST3 activation was assessed using a P-MST4-T178/-MST3-T190/-STK25-T174-specific antibody (anti-P-MST3). Note that the P-MST3 signal disappears in the siMST3-treated samples. (E) Kinase activity of MST3 is increased in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. HeLa cells were arrested at the G2/M border using nocodazole treatment for 14 h and released for 8 h before harvesting. Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting and in parallel to immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous MST3 species using anti-MST3 or control antibodies. Endogenous MST3 kinase activity was assessed by an in vitro kinase assay using recombinant MBP-NDR1 K118R as a substrate. Reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting against phosphorylation of Thr 444 in NDR1 and in parallel by exposure to a phosphorimager screen. NDR phosphorylation was quantified and normalized to the activity of MST3 in M phase.

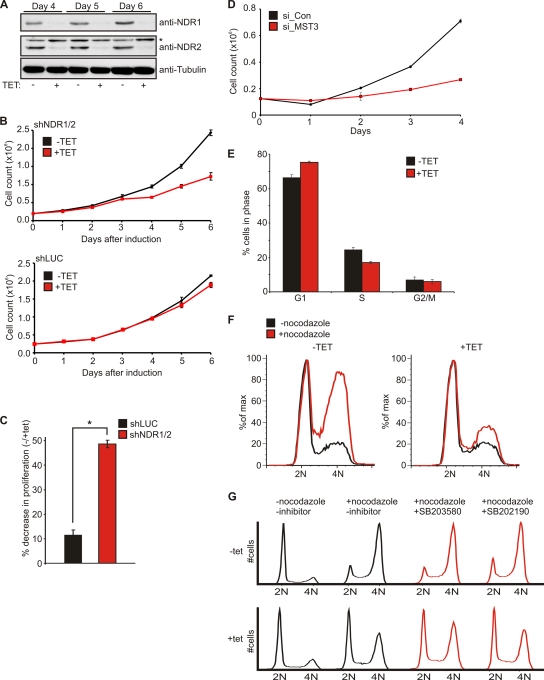

Depletion of NDR kinases results in G1 arrest and subsequent proliferation defects.

To analyze whether the activation of NDR kinases contributed to cell cycle progression and proliferation, we generated HeLa cells expressing inducible shRNA against NDR1 and NDR2 (Fig. 2A). Both isoforms were simultaneously targeted to avoid any compensatory effects as described earlier for NDR1-deficient mice (10). Knockdown of NDR kinases consistently resulted in decreased proliferation of around 50%, which was not observed in control clones expressing shRNA against firefly luciferase (Fig. 2B and C). Single knockdown of NDR kinase isoforms also resulted in a significant decrease in proliferation (data not shown). Accordingly, depletion of MST3 by RNAi resulted in reduced proliferation similar to that after knockdown of NDR1/2 (Fig. 2D). Reduced proliferation in NDR-depleted cells was accompanied by an increase in cells in G1 and a decrease in cells in S phase (Fig. 2E). G1 phase arrest was confirmed by treating cells with nocodazole to accumulate cycling cells at the G2/M border (Fig. 2F). Briefly, at 3 days after induction of shRNA expression, the cells were treated with nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules, activating the spindle assembly checkpoint and arrest cells at the G2/M border. (35). Therefore, cells blocked in G1 will not proceed to G2/M border, and as was apparent, cells depleted of NDR1/2 were retained in the G1 peak (Fig. 2F, +TET). Since depletion of NDR can result in centrosome defects (23), we asked next whether the G1 arrest was due to activation of the p38-p53 centrosome integrity checkpoint (35, 46). NDR1/2-depleted cells were treated with p38 inhibitors (SB203580 and SB202190) prior to G1 arrest assessment (Fig. 2G), revealing that inhibition of p38 had no detectable effect. These results suggest that p38-p53 signaling does not contribute to the cell cycle arrest upon NDR1/2 depletion. Therefore, we analyzed the mechanisms underlying the G1 block by investigating expression levels of other known G1/S regulators (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the expression of p21 and p27 was elevated in NDR1/2 knockdown cells without a significant decrease in the expression of cyclins and Cdks (Fig. 3A). In addition, the expression of the c-myc proto-oncogene was reduced. These results were confirmed in HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1 and NDR2 alone, as well as in transiently transfected HCT116 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, stable expression of shRNA-resistant NDR1wt in U2-OS cells counteracted p21 and p27 upregulation and restored cell proliferation (data not shown). This suggested that the observed G1 block upon depletion of NDR1/2 might be due to the inhibition of cyclin-Cdk complexes by increased levels of p21 and p27. In addition, we analyzed the effects of MST3 depletion on p21, p27, and c-myc levels (Fig. 3B). As found upon NDR depletion, we also observed upregulation of p21 and p27, while c-myc levels were reduced in MST3-depleted cells (Fig. 3B). These experiments suggest the existence of an MST3-NDR axis as regulator of cell proliferation.

Fig. 2.

shRNA-mediated knockdown of NDR1/2 results in cellular proliferation defects due to a G1 block. (A) Characterization of T-Rex-HeLa cells stably expressing shRNA against NDR1 and NDR2. Cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes, and shRNA expression was induced by the addition of tetracycline (TET) for the indicated times. Lysates from harvested cells were analyzed for NDR1 and NDR2 expression using isoform-specific antibodies (*, unspecific band). (B) NDR1/2 depletion results in proliferation defects. HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 (shNDR1/2) or firefly luciferase (shLUC) as a control were seeded in triplicates, and tetracycline was added to induce shRNA expression. After the indicated times, cells were harvested by trypsinization and counted using a ViCell automated cell counter. (C) Validation of proliferation defects in different clones stably expressing shNDR1/2 or shLUC (n = 3; P < 0.001). Experiments were performed as for panel B, and differences in proliferation were calculated as the percentage of cells without tetracycline to cells with tetracycline counted on day 6 after induction of shRNA expression. (D) Depletion of MST3 results in proliferation defects similar to those observed in NDR-depleted cells. HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (si_Con) or siRNA against MST3 (si_MST3); 24 h later, cells were seeded at defined densities in triplicates and cell counts were analyzed as for panel B. (E) Depletion of NDR1 and NDR2 results in an increase in G1 phase cells accompanied by a decrease in S phase cells. HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 were induced for 4 days with tetracycline. BrdU was added directly to the cell medium and left for 30 min before harvesting and processing for FACS analysis (n = 3). (F) Depletion of NDR1/2 results in G1 arrest. Knockdown of NDR1/2 was induced for 4 days using tetracycline. At 14 h before harvesting and processing for FACS analysis, cells were treated with 2.5 μg/ml nocodazole to induce G2/M accumulation. Fixed cells were stained with PI and analyzed by FACS. Histograms were overlaid to allow better comparison of cells in a given cell cycle phase. (G) Treatment of NDR1/2-depleted cells with inhibitors against p38 does not suppress G1 arrest. HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 were induced for 4 days with tetracycline. At 24 h before analysis, SB203580 or SB202190 (10 μM final concentration) was added to the cells. G1 arrest analysis was performed as for panel F.

Fig. 3.

Depletion of NDR1/2 kinases results in an increase in p21 and p27 protein levels and a decrease in c-myc protein level. (A) Reduced NDR kinase levels increase p21 and p27 and decrease c-myc. Knockdown of NDR1/2 was induced for 4 days, and cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of the indicated cell cycle regulators using Western blotting. (B) Depletion of MST3 increases p21 and p27 and decreases c-myc similarly to knockdown of NDR kinases. HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA (si_Con) or siRNA against MST3 (si_MST3). After 3 days, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (*, p27). (C) NDR1/2 depletion results in increased p27 mRNA levels, whereas changes in c-myc and p21 are observed only at the protein level. Knockdown of NDR1/2 was induced for the indicated times, and RNA extracts were prepared to analyze p21, p27, and c-myc mRNAs by quantitative RT-PCR. Values for p21, p27, and c-myc mRNAs are given as fold change relative to untreated samples (n = 3). In parallel, the samples were analyzed for the levels of the indicated proteins by Western blotting.

It has been shown that c-myc is able to repress p21 and p27 expression (9, 54). Therefore, we tested whether depletion of NDR1/2 would result in increased expression of p21 and p27 mRNAs. Strikingly, although p27 mRNA levels were clearly increased, we did not observe any elevation of p21 mRNA in our settings (Fig. 3C). In addition, NDR depletion did not affect c-myc mRNA expression, suggesting that NDR kinases regulated p21 and c-myc protein levels posttranscriptionally (Fig. 3C).

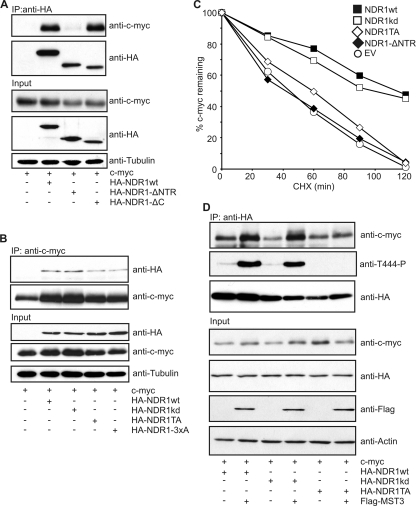

NDR kinases regulate c-myc protein levels by direct binding and interfering with FBW7-mediated ubiquitination.

A recent report analyzing posttranscriptional modifiers of c-myc in human B cells proposed that NDR1 could regulate c-myc protein stability (52). In full agreement with this previous report, c-myc protein levels were rescued by the addition of the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 in NDR1/2-depleted HeLa cells (data not shown). In addition, we could confirm that NDR1 and c-myc interacted on both overexpressed and endogenous levels (data not shown). Furthermore, NDR2 bound to c-myc with similar affinity as NDR1 (data not shown). Next, we analyzed the currently unknown determinants for NDR binding to c-myc. Using coimmunoprecipitation experiments, we found that c-myc interacted mainly with the N-terminal region (NTR) (residues 1 to 82) of NDR1 (Fig. 4A). In addition, interaction was shown to be modulated by HM phosphorylation (Thr 444) (Fig. 4B). Both the NTR and the HM phosphorylation site have been shown to be essential for full kinase activity of NDR (2, 36, 47), suggesting that NDR might bind to c-myc in an active conformation. Nevertheless, kinase-dead NDR1 (NDR1kd) associated with c-myc similarly to NDR1wt (Fig. 4B). Both NDR1wt and NDR1kd significantly stabilized c-myc levels (Fig. 4C). NDR1 mutants defective in or with reduced c-myc interaction (NDR1-ΔNTR and NDR1-TA) had minor effects on c-myc stability, indicating that binding of NDR1 to c-myc is required to stabilize c-myc levels. Furthermore, increasing HM phosphorylation of overexpressed NDR by coexpression of MST3 increased complex formation and c-myc stability (Fig. 4D and data not shown). The effects of overexpression and HM phosphorylation of NDR1 on endogenous c-myc levels were also tested. Strikingly, overexpression of NDR1wt and NDR1kd increased endogenous c-myc levels, which could be further increased by stimulating HM phosphorylation through coexpression of MST3 (data not shown). Besides stabilizing c-myc protein levels, NDR1wt but not NDR1TA (T444A) overexpression stimulated c-myc-mediated transcription (reference 45 and data not shown). This suggests that NDR expression and phosphorylation can positively affect c-myc protein levels and activity.

Fig. 4.

NDR1/2 in an active conformation stabilizes c-myc. (A) c-myc binds to the N-terminal region of NDR1. HEK293 cells were transfected with c-myc together with the indicated HA-tagged NDR1 constructs. NDR1 species were immunoprecipitated, and c-myc binding was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Binding of NDR1 to c-myc is modulated by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation (T444). HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated NDR1 constructs (NDR1TA, T444A; NDR1-3xA, T74, S281, and T444A). c-myc was immunoprecipitated, and bound NDR1 species were analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) Overexpression of NDR1wt and NDR1kd stabilizes c-myc. HEK293 cells were transfected with c-myc and the indicated NDR1 cDNA; 24 h later, cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times and c-myc levels were analyzed using the Li-Cor Odyssey system. (D) Hydrophobic motif phosphorylation of NDR increases binding of NDR to c-myc. HEK293 cells were transfected with c-myc and the indicated NDR1 cDNAs together with a vector encoding FLAG-MST3, and complex formation was analyzed.

Degradation of c-myc is tightly regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (49), and hence we tested whether NDR expression affected c-myc ubiquitination. Indeed, we observed that the stabilizing effect of NDR1 overexpression on c-myc was due to impaired c-myc ubiquitination (Fig. 5A). The FBW7 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex has been shown to mainly regulate c-myc ubiquitination and degradation (49). We tested the effect of NDR overexpression on FBW7-mediated ubiquitination (Fig. 5B). Ubiquitination of c-myc by FBW7 was impaired by NDR1wt overexpression, although NDR1 did not compete with FBW7 for c-myc interaction (Fig. 5C). Collectively, our analysis suggests a role for NDR kinases in the regulation of c-myc protein stability by interfering with FBW7-mediated ubiquitination. Interestingly, NDR kinases interacted with c-myc supported by HM phosphorylation, but independent of NDR kinase activity.

Fig. 5.

NDR overexpression impairs FBW7-mediated c-myc ubiquitination. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with c-myc and His-tagged ubiquitin (His-Ub) together with HA-NDR1wt where indicated. Ubiquitinated proteins were pulled down from cell lysates using Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)–Sepharose and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) NDR decreases FBW7-mediated ubiquitination of c-myc. The experiment was performed as for panel A, but where indicated, GFP-FBW7 was coexpressed. (C) NDR1 does not compete with FBW7 for c-myc binding. HEK 293 cells were transfected with c-myc, FBW7, and increasing amounts of NDR1wt. c-myc was immunoprecipitated and analyzed for bound FBW7.

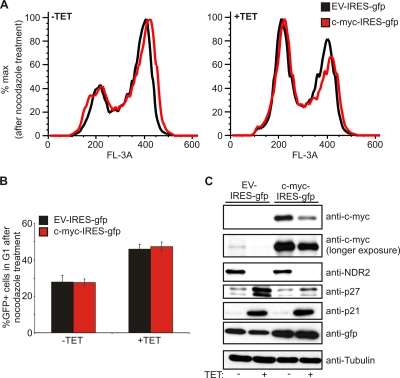

G1 arrest upon depletion of NDR is not dependent on c-myc.

Depletion of NDR1/2 results in G1 arrest accompanied by an increase in the p21 level and a decrease in c-myc. To test the potential contribution of a reduced c-myc level to the G1 arrest observed in NDR-depleted cells, we restored the c-myc level by exogenous expression (Fig. 6). Although restoring c-myc prevented, as expected, accumulation of p27, it failed to rescue cells from G1 arrest in this setting. These experiments therefore indicated that the increased levels of p21 might mediate the observed G1 arrest in NDR kinase-depleted cells.

Fig. 6.

G1 arrest in NDR-depleted cells is not dependent on c-myc. (A) HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 were induced for 72 h with tetracycline and transfected with vectors expressing c-myc together with an IRES-GFP as a transfection marker. G1 arrest analysis was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2F. Cell cycle profiles of GFP-positive cells were overlaid to allow for better comparison. (B) Analysis of GFP-positive cells in G1 after nocodazole arrest upon depletion of NDR1/2 and overexpression of c-myc (n = 3). (C) Analysis of c-myc, p21, and p27 in NDR1/2-depleted cells upon overexpression of c-myc. Cells were treated as described for panel A, but lysates were prepared before G1 arrest analysis.

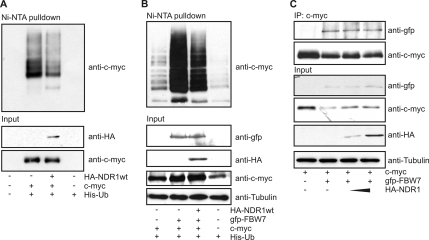

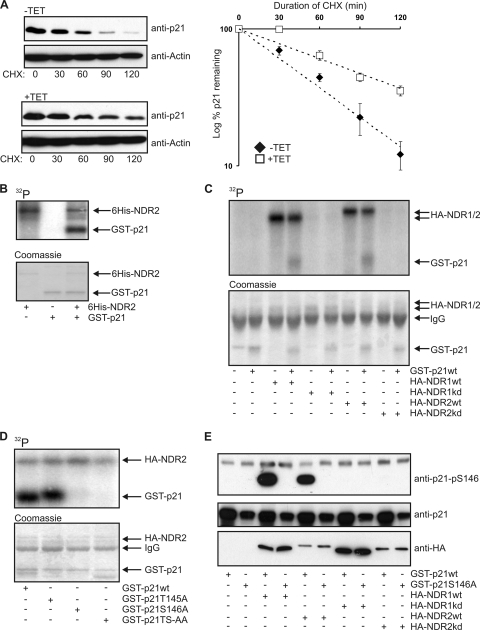

NDR kinases regulate p21 stability by phosphorylation of S146 on p21.

Since restoration of c-myc level was not sufficient to compensate for NDR depletion and release of the subsequent G1 arrest, we addressed the well-known cell cycle regulator p21 in our setting. NDR depletion results in increased p21 protein levels, without accompanying upregulation of p21 mRNA (Fig. 3). This indicates that NDR kinases could affect p21 protein stability. Indeed, knockdown of NDR1/2 significantly increased p21 protein stability (Fig. 7A). No binding of NDR1/2 to p21 could be detected (data not shown), suggesting a mechanism distinct from the regulation of c-myc by NDR. Earlier studies have implicated several phosphorylation sites on p21 in regulating p21 stability (8), which suggested p21 as a potential NDR kinase substrate. Recombinant NDR2 kinase was able to phosphorylate GST-p21 in an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 7B). Strikingly, purified NDR1 and NDR2wt phosphorylated p21 in vitro, while NDR1/2kd did not (Fig. 7C and data not shown). Although no substrates of NDR1/2 have been described, one study reported that NDR1 prefers a stretch of positively charged basic amino acids in the vicinity of the phosphorylation site (36). Intriguingly, the p21 primary sequence contains a stretch of four basic amino acids upstream of the known phosphorylation sites T145 and S146 (43), GRKRRQT145S146MT (G, glycine; R, arginine; K, lysine; Q, glutamine; T, threonine; S, serine; and M, methionine). Therefore, T145 or S146 alanine mutants were subjected to kinase assays (Fig. 7D and E). Phosphorylation of p21 by NDR1/2 was abolished when Ser 146 was mutated to alanine but not when Thr145 was mutated (Fig. 7D and data no shown). These findings were confirmed using a phospho-specific antibody for phosphorylation on Ser 146 (anti-p21-pS146) (Fig. 7E). Therefore, our analysis showed that NDR1/2 phosphorylates p21 mainly on S146.

Fig. 7.

NDR kinases phosphorylate p21 on S146 in vitro. (A) Depletion of NDR1/2 increases p21 stability. HeLa-shNDR1/2 cells were treated with tetracycline for 72 h. Prior to harvesting, cells were treated for the indicated times with CHX. p21 levels were analyzed using the Li-Cor Odyssey system (n = 3). p21 levels are depicted as the percentage remaining relative to the level at time zero, and trend lines were added to the data. r2 values for the trend lines are 0.98 (−TET) and 0.92 (+TET). Equation for the trend lines are y = 100e−0.0166x (−TET) and y = 100e−0.0083x (+TET). (B) Recombinant NDR2 phosphorylates recombinant p21. GST-p21 was used in an in vitro kinase assay with polyhistidine-tagged NDR2 from Sf9 cells in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. After 30 min, reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and exposure to a phosphorimager. (C) NDR1 and 2 phosphorylate p21 in vitro. HA-tagged NDR1/2wt or HA-NDR1/2kd was immunoprecipitated from okadaic acid-stimulated HEK293 cells and used for in vitro kinase assays with GST-p21 as a substrate. Reactions were analyzed as for panel B. (D) Ser 146 is the major site of p21 phosphorylated by NDR kinases. GST-p21 with mutated T145, S146, or T145/S146 phospho-acceptor sites was used as a substrate for in vitro kinase assays as described for panel B. (E) NDR1 and -2 phosphorylate p21 on Ser 146. GST-p21wt or GST-p21 S146A was used as a substrate in in vitro kinase assays using HA-tagged NDR1/2wt or HA-NDR1/2kd from okadaic acid-stimulated HEK 293 cells. Assays were analyzed by Western blotting using a phospho-specific antibody of p21 recognizing only if Ser 146 of p21 is phosphorylated.

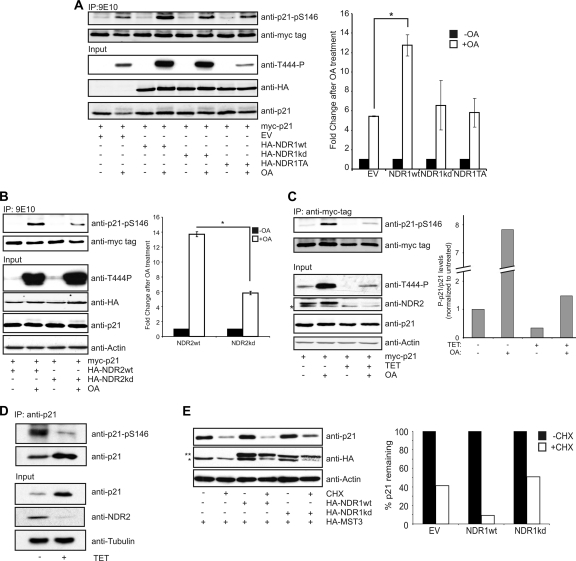

NDR kinases are efficiently activated by okadaic acid (OA) treatment. Indeed, overexpression of NDR1wt but not kinase-dead NDR1 or an HM mutant increased phosphorylation of p21 upon OA treatment (Fig. 8A). Similar results were obtained when NDR2wt or kinase-dead NDR2 was used (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, reduction of NDR kinases in cells by shRNA reduced OA-mediated as well as steady-state phosphorylation of p21 on S146 (Fig. 8C). Significantly, steady-state phosphorylation of endogenous p21 on S146 was reduced upon knockdown of NDR1/2 in HeLa cells without OA treatment, despite an increase in the total level of p21 (Fig. 8D). Since it has been shown that phosphorylation of S146 destabilizes p21 (42), we tested the effect of overexpressing NDR1 together with MST3 on the stability of p21 (Fig. 8E). Although overexpression of NDR1wt or NDR1kd did not significantly affect p21 steady-state level, treatment of cells with cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit translation revealed that overexpression of NDR1wt but not NDR1kd decreased p21 protein stability in this setting (Fig. 8E). Taken together, these results show that NDR kinases directly phosphorylated p21 on S146 in vitro and in vivo, establishing p21 as the first substrate for mammalian NDR kinases. Importantly, since phosphorylation on S146 can negatively affect the protein stability of p21, our results suggest that loss of NDR activity results in an increase in total p21 level and that increased activity of NDR leads to destabilization of p21.

Fig. 8.

NDR phosphorylates p21 in vivo and regulates p21 stability. (A) Overexpression of NDR1wt increases okadaic acid (OA)-induced phosphorylation of p21 on S146. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated HA-tagged NDR1 species together with myc-tagged p21. Samples were stimulated with OA for 1 h before lysis where indicated. myc-tagged p21 was immunoprecipitated from lysates, and p21-pS146 levels were analyzed and quantified using the Li-Cor Odyssey system (n = 3; P < 0.002). p21-pS146 levels were normalized to controls without OA. (B) NDR2 phosphorylates p21 on S146 in vivo. HeLa cells were transfected with the HA-tagged NDR2wt or NDR2kd together with myc-tagged p21. Samples were stimulated with OA for 1 h before lysis where indicated. myc-tagged p21 was immunoprecipitated from lysates, and p21-pS146 levels were analyzed and quantified using the Li-Cor Odyssey system (n = 3; P < 0.0001). p21-pS146 levels were normalized to controls without OA. (C) Depletion of NDR1/2 decreases phosphorylation of p21 on S146. HeLa-shNDR1/2 cells were induced for 72 h with tetracycline and transfected with cDNA encoding myc-tagged p21. At 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with OA for 1 h and lysed. p21-pS146 levels were analyzed as for panel B (*, unspecific band). p21-pS146 levels were normalized to the untreated control sample. (D) Depletion of NDR results in a reduction of phosphorylated p21. HeLa-shNDR1/2 cells were induced for 72 h with tetracycline before lysis and immunoprecipitation of endogenous p21 were performed. p21-pS146 levels were analyzed by Western blotting. (E) Overexpression of NDR decreases p21 stability. HeLa cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or with cDNAs encoding HA-NDR1wt or HA-NDR1kd in the presence of HA-MST3. Prior to lysis, cells were treated with CHX for 60 min where indicated (*, HA-MST3; **, HA-NDR).

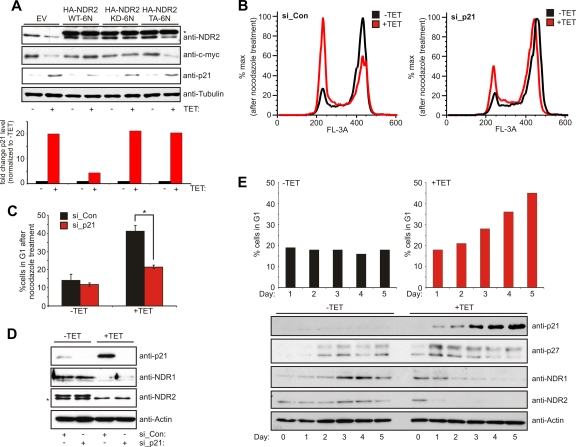

G1 arrest upon depletion of NDR kinases is dependent on increased p21 stability.

To confirm the effects of NDR on p21, we performed experiments to rescue the effects of depletion of NDR by transient overexpression of NDR mutants refractory to shRNA (Fig. 9A). Indeed, whereas overexpression of NDR2wt in this setting rescued both the effects on c-myc and p21 levels, overexpression of NDR2kd only restored c-myc levels. Importantly, NDR2TA failed to rescue either of the effects. Additionally, reexpression of refractory NDR1wt in U2OS shNDR1 cells rescued the effect on p21 levels upon NDR1 knockdown (data not shown). These observations fully confirm our previous findings, namely, that NDR can regulate c-myc stability irrespective of kinase activity, while the effect of NDR kinases on p21 levels is dependent on NDR kinase activity.

Fig. 9.

G1 arrest after NDR kinase knockdown is rescued by reducing p21 levels. (A) The effects of NDR kinase depletion can be rescued depending on the NDR mutant. HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR2 were treated for 48 h with tetracycline and subsequently transfected with the indicated NDR2 mutants refractory to shNDR2 (*, HA-tagged NDR2). p21 levels were quantified using the Li-Cor Odyssey system. (B) HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 were treated with tetracycline for 48 h before being transfected with siRNA against p21 on two consecutive days. The cells were treated for G1 arrest analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 2F at 24 h after the second transfection. (C) Quantification of cells in G1 after nocodazole treatment (n = 3; P < 0.002). (D) Cells obtained from the experiment for panel B were analyzed for the expression of p21 and NDR1/2 (*, unspecific band). (E) p21 levels correlate with G1 arrest in NDR1/2-depleted cells. HeLa cells expressing shRNA against NDR1/2 were induced with tetracycline for the indicated times before harvest and lysis. Cells used for cell cycle analysis were treated with 2.5 μg/ml nocodazole for 14 h before harvest.

Next we analyzed whether altered p21 levels mediated the G1 arrest upon depletion of NDR. Indeed, siRNA-mediated depletion of p21 was fully sufficient to result in a significant restoration of NDR1/2-depleted cells from G1 blockade (Fig. 9B to D). Furthermore, we have confirmed this finding by the use of a second, independent siRNA against p21 (data not shown). In full agreement with this finding, p21 levels were shown to correlate with G1 arrest in shNDR1/2 cells. Prolonged depletion of NDR1/2 resulted in an increasing amount of cells in G1 and correspondingly in an accumulation of p21 protein, whereas p27 levels did not correlate (Fig. 9E). Collectively, these experiments revealed that p21 is a key mediator of the G1 arrest observed in NDR kinase-depleted cells.

DISCUSSION

In eukaryotes NDR kinases have been shown to function in processes tightly linked to the cell cycle, such as mitotic exit, cell growth, proliferation, centrosome duplication, and morphogenesis (24). Here we identify human NDR kinases as novel regulators of cell cycle progression. NDR kinases are activated in G1, with the activation persisting into S phase (Fig. 1), in full accordance with NDR kinase function in centrosome duplication (23). Conversely, knockdown of NDR1/2 results in G1 arrest (Fig. 2). Importantly, although depletion of NDR kinases can result in centrosome duplication defects (22, 23), our experiments show that the G1 arrest is completely independent of the reported p38-p53 centrosome integrity checkpoint (35, 46).

Although they are well described in terms of upstream regulation and biochemical activation, signaling mechanisms downstream of mammalian NDR kinases remained elusive. Here we describe a novel function for NDR kinases in regulating the G1/S transition, identify c-myc and p21 as downstream signaling targets for mammalian NDR kinases, and provide detailed mechanistic insight into this regulation: whereas NDR kinases regulate c-myc protein stability by direct interaction independent of kinase activity (Fig. 4 and 5), p21 is directly phosphorylated by NDR kinases on Ser 146, thereby regulating p21 stability (Fig. 7 and 8). Furthermore, knockdown of NDR1/2 resulted in G1 arrest and was dependent on increased p21 stability but not on c-myc (Fig. 9).

NDR1 has been shown previously to bind to c-myc and increase its stability; however, mechanistic insight into this regulation has not been reported so far (52). Here we confirm the binding of NDR kinases to c-myc (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Strikingly, we find that both binding and stabilization of c-myc by NDR are independent of NDR kinase activity (Fig. 4), indicating a novel adaptor-like function for NDR kinases. We observed distinct effects on NDR–c-myc interaction upon point mutation of the hydrophobic motif phosphorylation site T444 or deletion of the C terminus. The C-terminal deletion mutant still interacted with c-myc, whereas point mutants (T444A, T444D, or T444E) displayed reduced or no interaction (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Since we found the N terminus of NDR to be responsible for the interaction with c-myc, deletions or mutations of the C terminus might have distinct conformational consequences for the structure of the N-terminal region of NDR. Therefore, future structural analysis of NDR kinases bearing mutations or deletions will be required to put these findings into the context of how NDR–c-myc interaction is modulated and hence how exactly NDR stabilizes c-myc.

c-myc protein levels are tightly regulated in cells. Apart from a pronounced regulation at the transcriptional level, protein levels of c-myc are controlled by ubiquitin ligases such as FBW7 (49). Here we show that NDR kinases do not compete with FBW7 for c-myc binding. Nevertheless, NDR kinases can inhibit c-myc ubiquitination by FBW7 (Fig. 5), indicating a novel mechanism by which NDR kinases interfere with c-myc degradation. Potentially, NDR kinases bound to c-myc inhibit ubiquitination directly or facilitate recruitment of deubiquitinating enzymes. Future studies to further define the effects of NDR kinases on c-myc stability are warranted.

Various mechanisms control expression of the Cdk inhibitor p21. The transcriptional regulation of p21 is well described and includes p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms (15). Here we show that the deregulation of p21 levels upon knockdown of NDR is not based on changes in transcription of the p21 gene (Fig. 3), indicating a novel aspect of p21 regulation on a posttranscriptional level by NDR kinases. Degradation of p21 is mediated by both ubiquitin-dependent and -independent mechanisms (1). In addition, phosphorylation of p21 has been shown to modulate a variety of p21 functions by affecting p21 localization, complex formation, and degradation (8). We show here that NDR1 and NDR2 phosphorylate p21 on S146 in vitro and in vivo, identifying p21 as the first in vivo substrate for human NDR1/2 (Fig. 7 and 8). Direct substrates of NDR/LATS orthologs in yeast and flies and also of mammalian LATS1/2 kinases have been discovered (6, 12, 28, 29, 33, 37). Interestingly, the aforementioned reports also defined consensus phosphorylation motifs for NDR/LATS kinases in yeast, flies, and mammals: for human LATS1/2 and fly warts, HXRXXS; for yeast Dbf2p and Sid2p, RXXS; and for yeast Cbk1p, HXR/KR/KXS (H, histidine; R, arginine; K, lysine; S, serine; and X, any amino acid). Interestingly, NDR1/2 kinases seem to have a less stringent consensus, since they prefer a stretch of positively charged basic amino acids N terminal of the phosphorylation site (36). Nevertheless, the p21 phosphorylation site of NDR, GRKRRQTS146M, matches a minimal consensus for NDR kinases across species, RxxS. However, further research in this area in order to define a precise consensus phosphorylation motif of mammalian NDR1/2 kinases is warranted.

Interestingly, endogenous p21 phosphorylation is reduced upon knockdown of NDR kinases despite an increase in total levels of p21 (Fig. 8). Phosphorylation of p21 on S146 has been reported to both increase and decrease p21 protein stability, depending on the cellular context and whether endogenous or overexpressed p21 was analyzed (30, 39, 42, 55). In our setting we could confirm the destabilizing effect of phosphorylated S146 on p21 protein turnover (Fig. 8). Even more importantly, our results show that increased p21 stability and subsequent accumulation of p21 correlated with the increase of cells in G1 (Fig. 9). Furthermore, in rescue experiments using siRNAs targeting p21 in cells depleted of NDR kinases, we observed a significant release from G1 arrest compared to that in control cells (Fig. 9) Therefore, p21 indeed is the main regulator of the G1 arrest observed in NDR kinase-depleted cells.

Previous reports revealed a role for NDR kinases in regulating mitotic chromosome alignment, centrosome duplication, and apoptosis (7, 22, 50). In these contexts, however, NDR kinases have been shown to function downstream of MST1 and MST2 kinases (7, 22, 50), which have been established as tumor suppressors as part of the HIPPO pathway (21, 56). A third member of the MST kinase family, MST3, has also been reported to act as an upstream kinase for NDR kinases (47), but the biological significance of this MST3-NDR axis has remained elusive. Here we identified MST3 as the main upstream kinase responsible for NDR activation in G1 (Fig. 1). In addition, we observed an increase of active MST3 in G1 compared to M phase, showing that MST3 activity can change in a cell cycle-dependent manner. Furthermore, our experiments confirmed a role of MST3 signaling in cell cycle regulation, as depletion of MST3 resulted in effects on proliferation similar to those observed for NDR kinases (Fig. 2D and 3B). MST3 signaling has been implicated in the regulation of axon outgrowth, cellular migration, and stress-induced apoptosis (5, 27, 31); however, any involvement of MST3 in cell cycle progression has not been described so far. Now, given our findings regarding this novel role of MST3 in the control of cell cycle progression, future research addressing the molecular activation mechanisms of MST3 is warranted.

Together, the findings described in this report lay a new foundation for research addressing functions of NDR kinases in cell cycle control. In combination with previous reports regarding apoptotic signaling (10, 50), our results actually indicate a potential dual role for NDR kinases in regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. Intriguingly, the different and partially opposing functions of mammalian NDR kinases seem to depend on the MST kinase input: whereas NDR kinase function in apoptosis, tumor suppression, and centrosome duplication is dependent on MST1 (10, 22, 50), NDR kinases regulate mitotic chromosome alignment downstream of MST2 (7). In line with these findings, the regulation of cell proliferation by NDR kinases described here depends not on MST1 or MST2 but on MST3. In conclusion, the MST3-NDR axis reported here can promote cell proliferation via direct phosphorylation of p21, thereby restricting p21 levels. Therefore, our work might provide a platform for establishing a dual and most likely cell context-dependent role for NDR kinases in normal and cancer cell biology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank B. Amati (European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy), N. Lamb (Institute de Génétique Humaine, Montpellier, France), B. Clurman (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA), C. V. Dang (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD), and N. Hynes and W. Filipowicz (Friedrich Miescher Institute, Basel, Switzerland) for providing reagents. We thank Pier Morin, Jr. (Université de Moncton, Moncton, Canada), for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Swiss Cancer League. The Friedrich Miescher Institute is part of the Novartis Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 January 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abbas T., Dutta A. 2009. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:400–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bichsel S. J., Tamaskovic R., Stegert M. R., Hemmings B. A. 2004. Mechanism of activation of NDR (nuclear Dbf2-related) protein kinase by the hMOB1 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279:35228–35235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bidlingmaier S., Weiss E. L., Seidel C., Drubin D. G., Snyder M. 2001. The Cbk1p pathway is important for polarized cell growth and cell separation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:2449–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bothos J., Tuttle R. L., Ottey M., Luca F. C., Halazonetis T. D. 2005. Human LATS1 is a mitotic exit network kinase. Cancer Res. 65:6568–6575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen C. B., Ng J. K., Choo P. H., Wu W., Porter A. G. 2009. Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 3 (MST3) mediates oxidative-stress-induced cell death by modulating JNK activation. Biosci. Rep. 29:405–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen C. T., et al. 2008. The SIN kinase Sid2 regulates cytoplasmic retention of the S. pombe Cdc14-like phosphatase Clp1. Curr. Biol. 18:1594–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chiba S., Ikeda M., Katsunuma K., Ohashi K., Mizuno K. 2009. MST2- and Furry-mediated activation of NDR1 kinase is critical for precise alignment of mitotic chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 19:675–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Child E. S., Mann D. J. 2006. The intricacies of p21 phosphorylation: protein/protein interactions, subcellular localization and stability. Cell Cycle 5:1313–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Claassen G. F., Hann S. R. 2000. A role for transcriptional repression of p21CIP1 by c-Myc in overcoming transforming growth factor beta-induced cell-cycle arrest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:9498–9503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornils H., et al. 2010. Ablation of the kinase NDR1 predisposes mice to the development of T cell lymphoma. Sci. Signal. 3:ra47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das M., Wiley D. J., Chen X., Shah K., Verde F. 2009. The conserved NDR kinase Orb6 controls polarized cell growth by spatial regulation of the small GTPase Cdc42. Curr. Biol. 19:1314–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dong J., et al. 2007. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130:1120–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Emoto K., et al. 2004. Control of dendritic branching and tiling by the Tricornered-kinase/Furry signaling pathway in Drosophila sensory neurons. Cell 119:245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emoto K., Parrish J. Z., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. 2006. The tumour suppressor Hippo acts with the NDR kinases in dendritic tiling and maintenance. Nature 443:210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gartel A. L., Tyner A. L. 1999. Transcriptional regulation of the p21((WAF1/CIP1)) gene. Exp. Cell Res. 246:280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guertin D. A., Chang L., Irshad F., Gould K. L., McCollum D. 2000. The role of the sid1p kinase and cdc14p in regulating the onset of cytokinesis in fission yeast. EMBO J. 19:1803–1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harbour J. W., Luo R. X., Dei Santi A., Postigo A. A., Dean D. C. 1999. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell 98:859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He Y., Fang X., Emoto K., Jan Y. N., Adler P. N. 2005. The tricornered Ser/Thr protein kinase is regulated by phosphorylation and interacts with furry during Drosophila wing hair development. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:689–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hergovich A., Bichsel S. J., Hemmings B. A. 2005. Human NDR kinases are rapidly activated by MOB proteins through recruitment to the plasma membrane and phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:8259–8272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hergovich A., Cornils H., Hemmings B. A. 2008. Mammalian NDR protein kinases: from regulation to a role in centrosome duplication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hergovich A., Hemmings B. A. 2009. Mammalian NDR/LATS protein kinases in hippo tumor suppressor signaling. Biofactors 35:338–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hergovich A., et al. 2009. The MST1 and hMOB1 tumor suppressors control human centrosome duplication by regulating NDR kinase phosphorylation. Curr. Biol. 19:1692–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hergovich A., Lamla S., Nigg E. A., Hemmings B. A. 2007. Centrosome-associated NDR kinase regulates centrosome duplication. Mol. Cell 25:625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hergovich A., Stegert M. R., Schmitz D., Hemmings B. A. 2006. NDR kinases regulate essential cell processes from yeast to humans. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7:253–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hou M. C., Wiley D. J., Verde F., McCollum D. 2003. Mob2p interacts with the protein kinase Orb6p to promote coordination of cell polarity with cell cycle progression. J. Cell Sci. 116:125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang J., Wu S., Barrera J., Matthews K., Pan D. 2005. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell 122:421–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Irwin N., Li Y. M., O'Toole J. E., Benowitz L. I. 2006. Mst3b, a purine-sensitive Ste20-like protein kinase, regulates axon outgrowth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:18320–18325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jansen J. M., Wanless A. G., Seidel C. W., Weiss E. L. 2009. Cbk1 regulation of the RNA-binding protein Ssd1 integrates cell fate with translational control. Curr. Biol. 19:2114–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lei Q. Y., et al. 2008. TAZ promotes cell proliferation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and is inhibited by the hippo pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:2426–2436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y., Dowbenko D., Lasky L. A. 2002. AKT/PKB phosphorylation of p21Cip/WAF1 enhances protein stability of p21Cip/WAF1 and promotes cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 277:11352–11361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu T. J., et al. 2006. Inhibition of cell migration by autophosphorylated mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 3 (MST3) involves paxillin and protein-tyrosine phosphatase-PEST. J. Biol. Chem. 281:38405–38417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Massague J. 2004. G1 cell-cycle control and cancer. Nature 432:298–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mazanka E., et al. 2008. The NDR/LATS family kinase Cbk1 directly controls transcriptional asymmetry. PLoS Biol. 6:e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McPherson J. P., et al. 2004. Lats2/Kpm is required for embryonic development, proliferation control and genomic integrity. EMBO J. 23:3677–3688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mikule K., et al. 2007. Loss of centrosome integrity induces p38-p53-p21-dependent G1-S arrest. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:160–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Millward T. A., Heizmann C. W., Schafer B. W., Hemmings B. A. 1998. Calcium regulation of Ndr protein kinase mediated by S100 calcium-binding proteins. EMBO J. 17:5913–5922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mohl D. A., Huddleston M. J., Collingwood T. S., Annan R. S., Deshaies R. J. 2009. Dbf2-Mob1 drives relocalization of protein phosphatase Cdc14 to the cytoplasm during exit from mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 184:527–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nelson B., et al. 2003. RAM: a conserved signaling network that regulates Ace2p transcriptional activity and polarized morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:3782–3803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Oh Y. T., Chun K. H., Park B. D., Choi J. S., Lee S. K. 2007. Regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 by protein kinase Cdelta-mediated phosphorylation. Apoptosis 12:1339–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ray S., et al. 2010. The mitosis-to-interphase transition is coordinated by cross talk between the SIN and MOR pathways in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Biol. 190:793–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Salghetti S. E., Kim S. Y., Tansey W. P. 1999. Destruction of Myc by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: cancer-associated and transforming mutations stabilize Myc. EMBO J. 18:717–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Scott M. T., Ingram A., Ball K. L. 2002. PDK1-dependent activation of atypical PKC leads to degradation of the p21 tumour modifier protein. EMBO J. 21:6771–6780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scott M. T., Morrice N., Ball K. L. 2000. Reversible phosphorylation at the C-terminal regulatory domain of p21(Waf1/Cip1) modulates proliferating cell nuclear antigen binding. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11529–11537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. 2004. Living with or without cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 18:2699–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shim H., et al. 1997. c-Myc transactivation of LDH-A: implications for tumor metabolism and growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94:6658–6663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Srsen V., Gnadt N., Dammermann A., Merdes A. 2006. Inhibition of centrosome protein assembly leads to p53-dependent exit from the cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 174:625–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stegert M. R., Hergovich A., Tamaskovic R., Bichsel S. J., Hemmings B. A. 2005. Regulation of NDR protein kinase by hydrophobic motif phosphorylation mediated by the mammalian Ste20-like kinase MST3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:11019–11029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tintignac L. A., et al. 2004. Mutant MyoD lacking Cdc2 phosphorylation sites delays M-phase entry. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1809–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vervoorts J., Luscher-Firzlaff J., Luscher B. 2006. The ins and outs of MYC regulation by posttranslational mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 281:34725–34729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vichalkovski A., et al. 2008. NDR kinase is activated by RASSF1A/MST1 in response to Fas receptor stimulation and promotes apoptosis. Curr. Biol. 18:1889–1895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Visintin R., Amon A. 2001. Regulation of the mitotic exit protein kinases Cdc15 and Dbf2. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:2961–2974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang K., et al. 2009. Genome-wide identification of post-translational modulators of transcription factor activity in human B cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 27:829–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiss E. L., et al. 2002. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mob2p-Cbk1p kinase complex promotes polarized growth and acts with the mitotic exit network to facilitate daughter cell-specific localization of Ace2p transcription factor. J. Cell Biol. 158:885–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang W., et al. 2001. Repression of transcription of the p27(Kip1) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene by c-Myc. Oncogene 20:1688–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhang Y., Wang Z., Magnuson N. S. 2007. Pim-1 kinase-dependent phosphorylation of p21Cip1/WAF1 regulates its stability and cellular localization in H1299 cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 5:909–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhao B., Lei Q. Y., Guan K. L. 2008. The Hippo-YAP pathway: new connections between regulation of organ size and cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20:638–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]