Abstract

Objective: This study was undertaken to determine if a systematic review of the evidence from thirty years of literature evaluating clinical medical librarian (CML) programs could help clarify the effectiveness of this outreach service model.

Methods: A descriptive review of the CML literature describes the general characteristics of these services as they have been implemented, primarily in teaching-hospital settings. Comprehensive searches for CML studies using quantitative or qualitative evaluation methods were conducted in the medical, allied health, librarianship, and social sciences literature.

Findings: Thirty-five studies published between 1974 and 2001 met the review criteria. Most (30) evaluated single, active programs and used descriptive research methods (e.g., use statistics or surveys/questionnaires). A weighted average of 89% of users in twelve studies found CML services useful and of high quality, and 65% of users in another overlapping, but not identical, twelve studies said these services contributed to improved patient care.

Conclusions: The total amount of research evidence for CML program effectiveness is not great and most of it is descriptive rather than comparative or analytically qualitative. Standards are needed to consistently evaluate CML or informationist programs in the future. A carefully structured multiprogram study including three to five of the best current programs is needed to define the true value of these services.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical medical librarian (CML) services have been implemented in dozens of different clinical health care settings since the first program started with grant funding from the National Library of Medicine in 1971 at the University of Missouri−Kansas City School of Medicine [1, 2]. Descriptions and evaluative discussions of these programs have been published with considerable regularity in the library and health sciences literature over the past three decades. However, a 1985 review by Cimpl (the former name of the first author of this review) of the first fifteen years of this literature found only eight published studies that used a survey or questionnaire to assess the value or cost-effectiveness of those early programs, and these studies provided very limited data to support their generally positive assessments [3]. Since then, many more descriptive papers have been written as well as a number of additional studies incorporating at least some evaluative methodology. As a result, clinical librarianship has become a widely recognized, but still relatively infrequently used, model for extending library and information services into the clinical health care environment.

The current study was undertaken to determine if a systematic review of the cumulative, thirty years of evidence from the literature evaluating CML programs could help provide a more definitive determination of the potential effectiveness of this model of outreach service and also help inform the current debate on the potential for developing CML-like “informationist” roles in health care settings [4, 5]. However, we were not optimistic and hypothesized that the published literature would provide little additional strong evidence showing how or if CML services contribute to improved patient care or better performance of health professionals in clinical health care settings.

The paper that follows first provides a descriptive review of the entire CML literature to show the general characteristics of these services as they have been implemented, primarily in teaching-hospital settings. This review also includes other related research studies in clinical health care settings about the impact of information services on education and patient care as well as more recent articles suggesting that health sciences librarians can play a significant role in evidence-based medicine and knowledge management. The next section of the paper describes the criteria and methods used to screen the CML literature for evaluative studies along with the characteristics and measures used to categorize and analyze the thirty-five evaluative studies of CML programs identified from this systematic review. Summary tables are then presented and discussed. The paper concludes with a consideration of the implications of this review for the development of future clinical librarian or informationist services and some recommendations for future evaluation research studies.

BACKGROUND AND SIGNIFICANCE OF CLINCIAL MEDICAL LIBRARIAN (CML) SERVICES

Clinical medical librarian services (sometimes called just “clinical librarian” services) were originally conceived by librarians as a way to integrate health sciences library services and the literature searching expertise of medical librarians into the patient care setting [6]. A primary goal of almost all these programs has been to overcome the time, cost, and expertise barriers that clinicians face when they attempt to incorporate the best current evidence from the literature into their patient care decisions. An important secondary goal of most of these programs has been to enhance the educational experience of students and resident physicians in training [7, 8]. Much like clinical pharmacists, social workers, nutritionists or other allied health professionals, clinical librarians have typically worked as visiting adjunct members of the patient care team for part of their work day or work week in settings such as teaching or inpatient rounds, morning report, and other clinical conferences or journal clubs. The remainder of their time is usually spent in the health sciences library searching, summarizing, and packaging information for delivery back to individuals or to the entire health care team [9–17].

By moving the librarian away from the traditional, in-library reference desk into a clinical setting, CML services have been promoted as a way for the librarian to develop a better understanding of the specific patient-care context of information needs [18, 19]. In addition, by providing an opportunity for the CML to learn about and directly experience the work environment of clinicians, the experience has enabled many CLMs to anticipate information needs and regularly deliver relevant documents or literature search results before they are actually requested [20–25]. CML services began in an era (the early 1970s) when bibliographic database searching was almost exclusively the professional domain of specially trained librarians. Since then, the introduction of very user-friendly search engines and freely accessible versions of MEDLINE and other databases on the Web has shifted the emphasis of many CML services from facilitating and mediating access to information to educating health care team members about the strategies needed to effectively use these resources on their own [26–30].

Most CML programs have been limited to one, or a few, clinical services in institutions where the department head or other clinical team leaders have been supportive and willing to underwrite the extra costs of the CML services or where the clinical service is willing to serve as a project test bed for this new service piloted with library funds [31–35]. CML roles, as described in the numerous published case reports, have included providing research assistance for clinical faculty [36–38], providing bibliographies on requested topics [39–42], selecting and summarizing or abstracting articles to elucidate problems in patient care [43–45], educating students and clinical team members about effective information searching and resource management [46–50], providing information to patients and their families [51–53], and serving as ambassadors to promote the use of traditional library services [54, 55]. These reports have also discussed the various factors presumed to contribute to CML program success or failure, including the degree to which the librarian is accepted as a member of the health care team, the medical knowledgebase of the librarian, the librarian's willingness to undertake the CML role, the frequency with which the CML services are requested and used by members of the health care team, and the cost of the services and the budget resources available to support those costs [56–65].

RELATED RESEARCH

Over the past fifteen years, the development of additional CML programs has also been supported and stimulated by a number of related studies that have attempted to assess the general impact of hospital library services on the quality and costs of clinical care [66]. Three of these studies have been particularly influential. The first, conducted by King in 1986, studied the contribution of hospital library information services to clinical decision making and patient care [67]. Using an unobtrusive design, the study asked 310 physicians and other health professionals to request information on a current case or clinical situation from the hospital library and then to complete a questionnaire on the results without revealing their involvement in the study to library staff. Of the 176 valid responses received, 74% reported that they probably or definitely would have handled the case differently with the information received from the library. In 1990–1991, using a similar methodology, Marshall coordinated a study surveying 448 physicians in fifteen hospitals [68]. Of the 208 questionnaires returned, 80% reported that they either probably or definitely would have handled some aspect of patient care differently. A third major study, conducted in three major teaching hospitals by Klein and colleagues in 1989–1990, investigated the relationship between hospital costs, charges, and length of stay for 192 test patient cases for which MEDLINE searches were conducted and over 10,000 control cases for which MEDLINE searches were not conducted [69]. They found that when a MEDLINE search was conducted during the first half of the hospital stay, the test-case patients had statistically significant lower hospital costs, charges, and lengths of stay.

Another much more recent area of concern about the use of the clinical health sciences literature is the need for “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” [70]. This growing evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement (which also extends to nursing, dentistry, public health, and other health professions) now includes international efforts (such as the Cochrane Collaboration [71]) to produce rigorous, systematic reviews of the literature and specialized databases to guide clinical practice [72]. Evidence-based medicine is also providing additional opportunities for health sciences librarians, including clinical librarians, to demonstrate their literature searching expertise with clinicians who need to search, evaluate, and access the best current evidence [73–75]. This collaborative EBM work has even suggested the need for “evidence-based librarianship” to improve the professional services of librarians working with clinicians and researchers [76].

Finally, CML and EBM strategies have both suggested the possibility of developing greatly expanded “knowledge management” roles for information professionals in clinical settings. These roles would require the integration of “individual clinical expertise with the best external evidence” [77, 78]. Davidoff and Florance have called for the creation of a clinical “informationist” professional role within clinical health care teams to provide this knowledge management expertise [79]. This suggestion has provoked widespread discussion and debate [80, 81] as well as suggestions for how to train health professionals or librarians to assume these expanded roles [82–84].

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW METHODS USED

The systematic review phase of this study started with comprehensive searches in medical, allied health, librarianship, and social sciences literature databases (MEDLINE, Library Literature, Library and Information Science Abstracts, and Social Sciences Citation Index) to locate published studies dealing with any aspect of clinical medical librarianship. The search terms used included “clinical,” “medical,” “library,” “librarian,” “librarianship,” “CL,” and “CML.” The Institute for Scientific Information's SCISEARCH database was also used to scan all articles citing Cimpl's 1985 review. The references in the resulting articles were also scanned for additional studies and reports. Finally, this process identified two British colleagues (Winning and Beverly) who were also engaged in a similar effort to review “primary [clinical librarianship] studies which included an evaluative research element,” but limited to studies published after 1982 (because they aimed to “build upon” and not replicate the 1985 Cimpl review) [85, 86]. They were generous in sharing their literature search results prior to the publication of their review, thus providing additional citations for consideration in this review. This process yielded over 250 citations to reports and studies published between 1974 and 2002 that dealt directly or indirectly with some aspect of clinical librarianship.

Based on the titles, source journals, or abstracts of the papers, we next identified and then located full-text copies of 107 potentially relevant studies for closer examination. Each paper was read to determine if any more-or-less-formal quantitative or qualitative methods were used by the authors to evaluate some aspect of a single (or more than one) clinical librarianship service or program. Following the model for medical informatics evaluative studies outlined by Friedman, Owens, and Wyatt [87], each article was further evaluated for any formal methods used to study either the need for CML services, the development process for those services, the effectiveness of the structure or functions of the program, or the outcome effects of the CML services on patient care, education, or research in the clinical setting. Evidence of more formal evaluative research methods included one or more of the following: a careful description of the population or sample of clinicians receiving CML services and the setting(s) in which the services were provided; questions or hypotheses posed about the need, reliability, effectiveness, or impact of the services in the introduction sections of the article; tables or graphs summarizing data collected from the program; and a “methods” or “results” section in the structure of the paper.

This review determined the final group of thirty-five papers reporting studies with some evidence of formal quantitative or qualitative evaluation methods. These were then read more carefully and categorized in spreadsheet tables according to the hypotheses or problems they proposed to study, the research methods they used (including the data or other measures studied and how these were collected and analyzed), the study period and institutional setting, the population or sample of clinicians who received CML services, the quantitative or qualitative research results reported, and any implications for the future suggested by the authors. Quantitative research results, where available, were carefully recorded, along with their statistical parameters in case something approaching a meta-analysis statistical summary could be calculated from the combined results of the studies reviewed. Although meta-analysis has been used primarily for statistically combining the results of clinical trials, it has been suggested that such studies can help support “evidence-based librarianship” and can also be used by clinical librarians or informationists to bring summaries of the best evidence into the clinical setting [88, 89].

FINDINGS

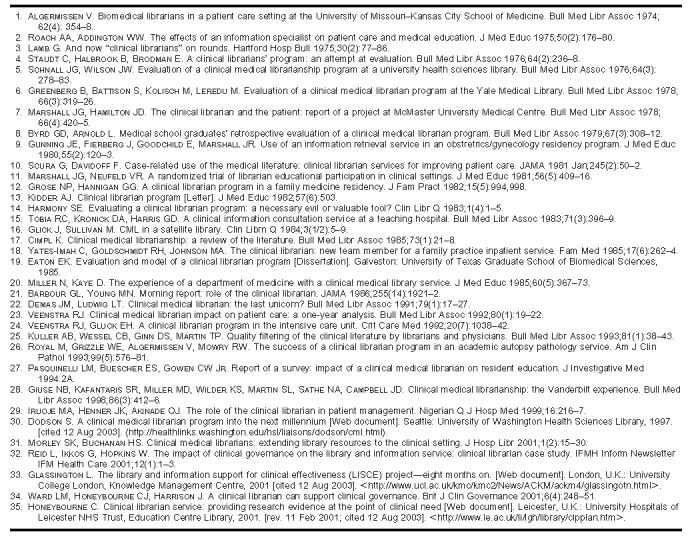

Table 1 summarizes the bibliographic information for the thirty-five evaluative studies of CML services that met the criteria outlined above (one additional unpublished evaluation study in Australia was called to our attention by its first author [90]). Interestingly, the seventeen evaluative studies published after 1982 that were included in the Winning-Beverley systematic review [91] were also all selected according to the criteria used for this review. However, our review also includes three additional studies published after 1982 (Kuller, Morley, and Glassington) that Winning and Beverley determined to be simply descriptive. Finally, our review identified fifteen other earlier studies, including Cimpl's 1985 review, twelve of the studies cited in that review, and two additional studies that had been missed by Cimpl (Lamb and Marshall/Neufeld).

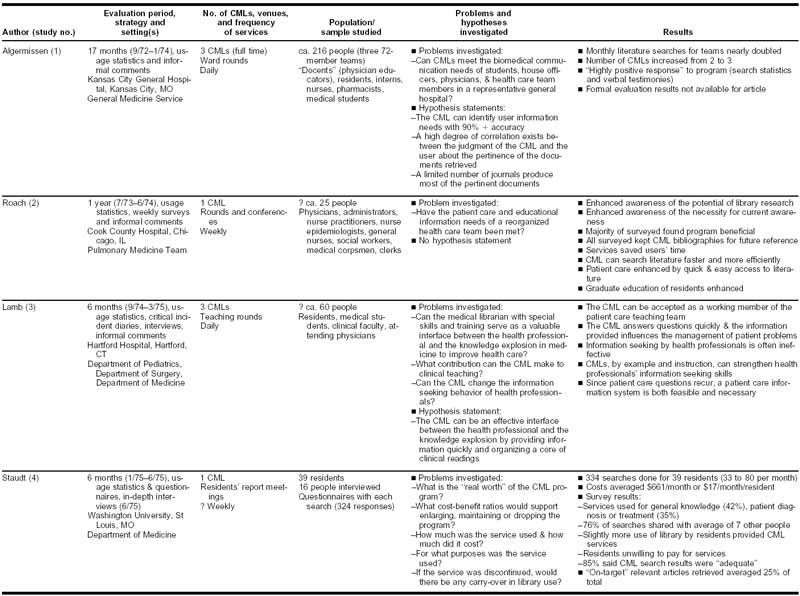

Table 1 Bibliographic information for all identified evaluative studies of clinical medical librarian (CML) programs; arranged chronologically from 1974 to 2001

These thirty-five studies were published between 1974 and 2001 in fourteen different journals as well as in a dissertation and on three Websites. The Bulletin of the Medical Library Association accounts for 37% of the total (13), but the library literature as a whole accounts for less than half (15 or 43%). The rest are scattered among various general and clinical medical journals, with two journals each accounting for more than one study: the Journal of Medical Education (5) and JAMA (2). In all, seventy-seven different individuals contributed to these studies, but only four contributed to more than one (V. Algermissen, C. Honeybourne, J. G. Marshall, and R. J. Veenstra each authored or co-authored two studies). In the tables and discussion of the systematic review results presented in the rest of this paper, these studies will be identified by the last name of the first author and, where necessary, the first coauthor.

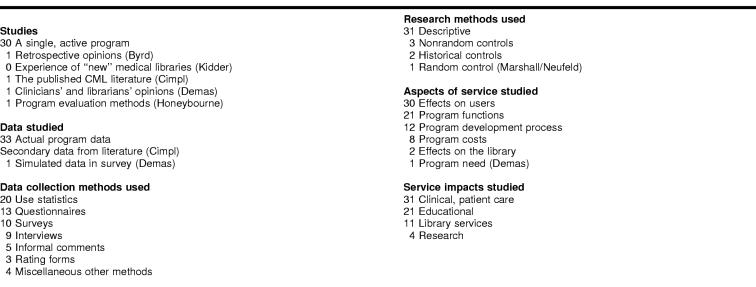

Table 2 summarizes the general characteristics and research methods used in each of the thirty-five studies. With only five exceptions, these studies have focused on single active programs (although often serving several clinical patient care units or departments), usually in individual hospitals or other clinical settings. The results reported were most often based on actual data collected by practicing CMLs in those settings using descriptive data collection and analysis methods such as use statistics, surveys, questionnaires, or interviews. Also, the great majority of these studies focused on users' perceptions of the usefulness and effectiveness of CML services or the functional efficiency of the services as well as the patient-care or educational impact of the information provided.

Table 2 Distribution of CML evaluative study general characteristics

Atypical studies

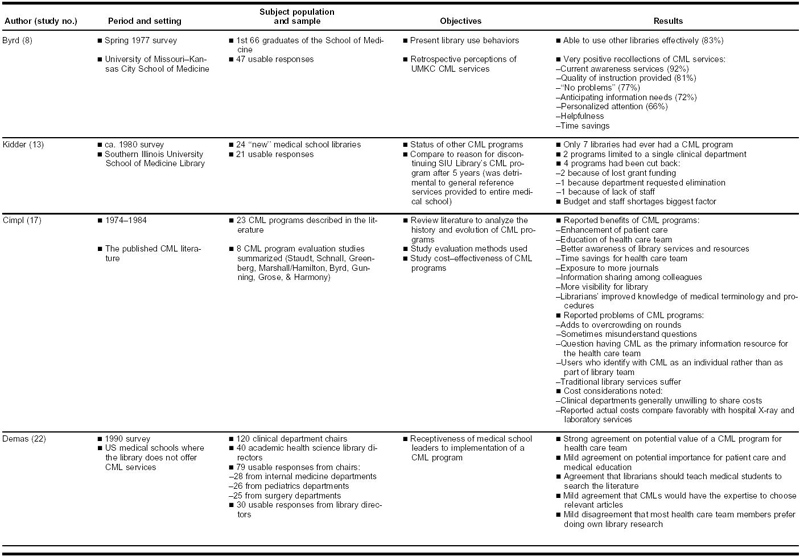

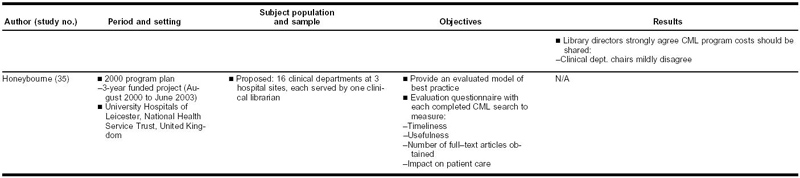

Table 3 briefly summarizes the period and setting, subject population and sample, objectives, and results of the five atypical CML-program evaluation studies. In general, these five studies reported very mixed results using a combination of current, retrospective, and needs assessment data. The results included a variety of opinions from users of CML services and other potential supporters about the benefits and problems associated with these services. The benefits reported included the helpfulness and personal attention to information services, including instruction provided by, or anticipated from, CMLs. The problems reported included the difficulty of finding the resources needed to hire and train librarians to provide these services for all clinical health care teams and the potential for inadequately trained librarians to misinterpret clinical information needs. These atypical evaluation strategies also demonstrated a variety of macro- and micro-approaches, ranging from a literature review and a retrospective survey of the former student users of one CML program to a national survey of librarians and clinical department heads and a project evaluation plan based on a “scoping study.”

Table 3 Five atypical CML program evaluation studies

The Byrd and Honeybourne studies each focused on a single CML program. Byrd evaluated the retrospective opinions of practicing physicians who had used one school's CML services while they were undergraduate medical students, and Honeybourne described a proposal to develop a methodology for evaluating a CML program that had not yet been fully implemented. Kidder's letter to the editor described a 1980 survey of twenty-four “new” medical school libraries (located in schools that graduated their first class in or after 1972) asking about the status of any current or previous CML programs at their institutions. Cimpl used secondary data from a review of the CML literature published before 1985 to assess the costs of, and evaluation strategies used for, programs up to that date. Finally, Demas described a double-blind survey of a sample of 120 clinical department heads and 40 library directors in academic medical centers without CML programs, using scenarios describing CML services to assess acceptance of, and attitudes toward, the CML service model.

Single-program study characteristics

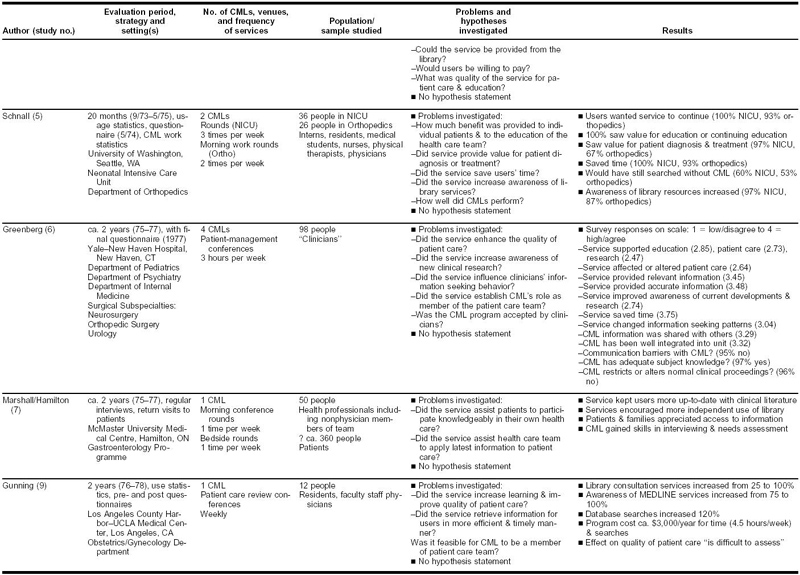

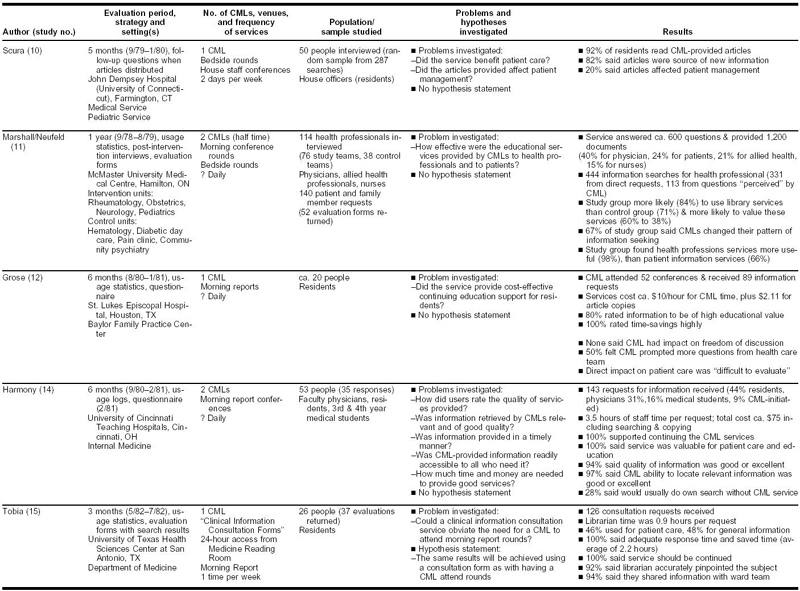

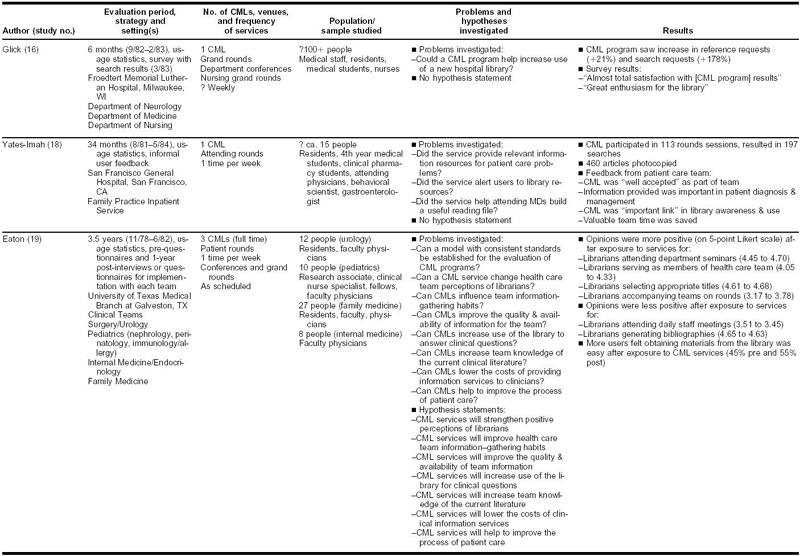

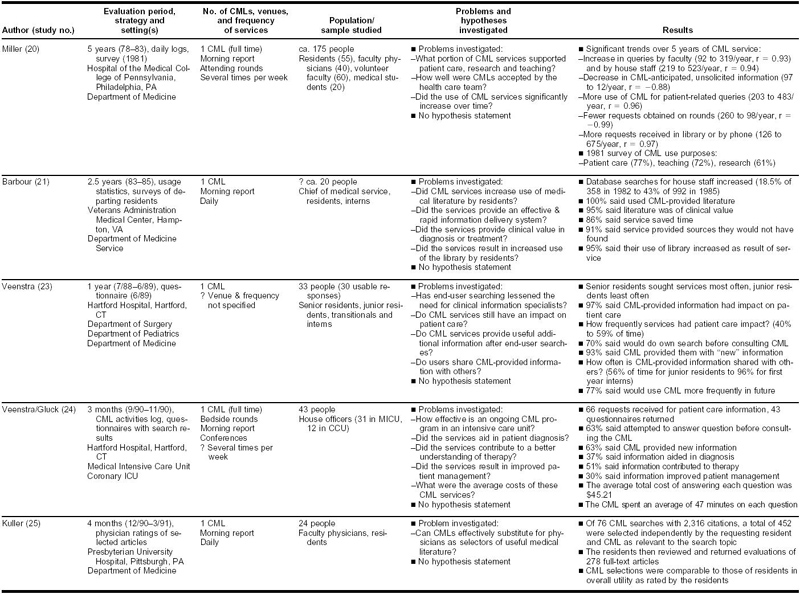

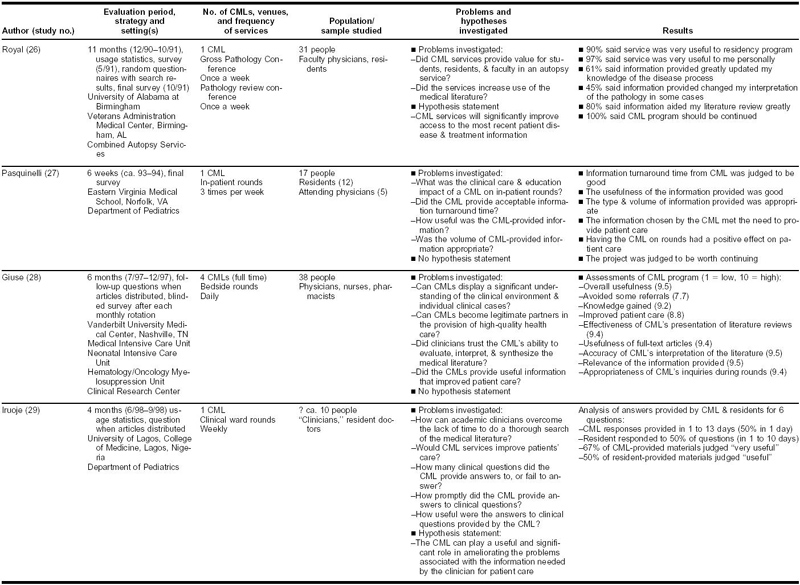

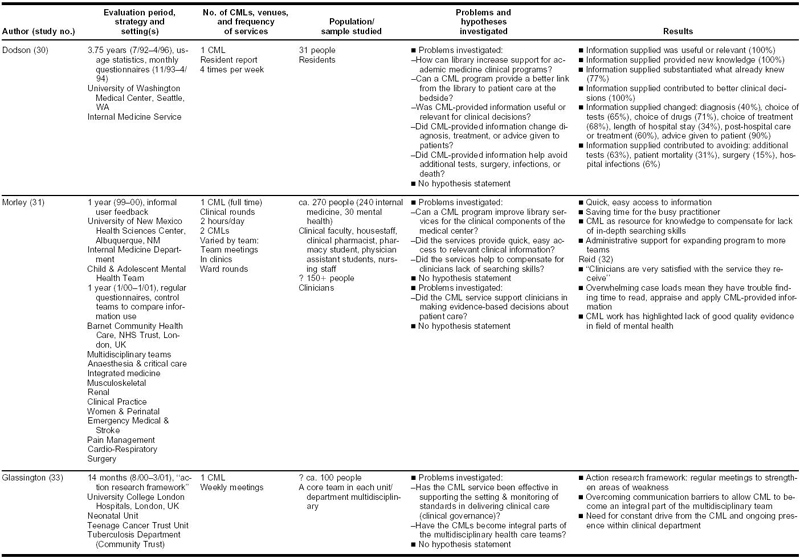

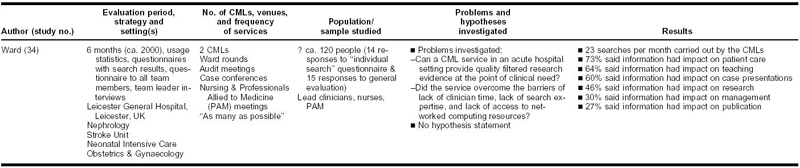

Table 4 summarizes the evaluation periods, strategies, and settings; number of CMLs, venues, and frequency of services; the study population and sample numbers and characteristics; the problems and hypotheses investigated; and the results reported from the remaining thirty evaluative studies focusing on single programs. The evaluation period for these studies ranged from six weeks to five years, with a median period of one year. The most common evaluation strategy has been the collection and analysis of usage statistics from the CML services provided (20 studies); followed by the use of surveys or questionnaires (13 studies), often distributed with the articles and other information given to health professional users by the CMLs (9 studies); one-time surveys conducted at the end of the defined evaluation period (10 studies); and interviews with users (9 studies). Many evaluators used more than one strategy in combination, but all of these and some other scattered methods (such as diaries or work logs, rating forms, and informal user feedback) are essentially descriptive.

Table 4 Characteristics of single CML program evaluative studies

Only four studies used, or suggested, more rigorous comparative research methods. Two used historically controlled before-and-after methods, with pre- and post surveys or interviews to measure the changes attributable to the CML services (Gunning and Eaton). One study used randomly selected intervention and control groups to experimentally test the extent to which the measured outcomes could be attributed to the CML services provided (Marshall/Neufeld), and one additional recent study described a plan to also use control teams to “compare their information use with that of the study teams” (Reid), but the study results reported did not include any data from that comparison.

The most common settings for these studies were hospital clinical departments, units, or teams; most frequently in departments of medicine or internal medicine (19); followed by departments of pediatrics (7); intensive care units (5); departments of surgery (4); and obstetrics and gynecology (3). Most of the CML programs in these studies served only one clinical department or unit (16 studies), but a number were serving two (4), three (4), or four units (5), and one evaluated program was serving ten different clinical units (Reid).

Most of these programs (20) used just one, usually part-time, CML to provide the evaluated services, but a few programs employed two (5), three (Algermissen, Lamb, and Eaton) or four (Greenberg and Giuse) CMLs. The evaluated services were usually provided while attending patient care rounds or conferences, such as morning report, and only ten of the evaluated CML programs provided these services on a daily schedule. The most frequent schedule of attendance at rounds or conferences was once a week (12 programs), with the rest scheduled two, three, or “several” times each week.

The number of health care professional users of CML services surveyed or otherwise studied in each of these programs ranged from 10 to about 270 people, with a median of 35 and an average of 64. The target population most frequently served by these programs was resident physicians in training, or “house officers” as they were sometimes labeled (22 programs). Other health professionals often targeted by these programs included faculty or staff physicians or “clinicians” (19 programs), nurses (9 programs), and undergraduate medical students (7 programs). A number of other allied health profession and student users were identified as part of the evaluation strategies of many programs, and two also targeted patients and their families (Marshall/Hamilton and Marshall/Neufeld).

The problems identified or goals outlined by the authors of these studies included a fairly wide range of questions or issues surrounding the effective provision of CML services. Most often these research problems or goals were not explicitly stated as such in the published article, but could be inferred from the introductory paragraphs. Only six studies also included specific research-hypothesis statements to be tested by the study methodologies and results. The most frequent category of problem identified in these studies related to how the CML services would affect patient care by the health professional users, or more specifically, the quality of their diagnoses and treatments (20 studies). The next most frequently noted problems investigated were the impact of CML services on the graduate education of residents (8 studies) and the efficiency and timeliness of the CML services provided (6 studies). Other problems investigated with some frequency included the degree to which the CML was accepted as a member of the clinical health care team, whether the CML services helped to stimulate increased use of traditional health sciences library services and resources, whether the CML-provided information resources improved the team members' knowledge of the clinical literature, and how the team viewed the overall quality and value of the CML program (each of these problems was investigated in four studies). A wide range of other more specific questions was also mentioned as problems or goals in these studies, ranging from how often team members would share CML-provided information with others to whether a library-based service could substitute for CML attendance at rounds or conferences.

Single-program study results

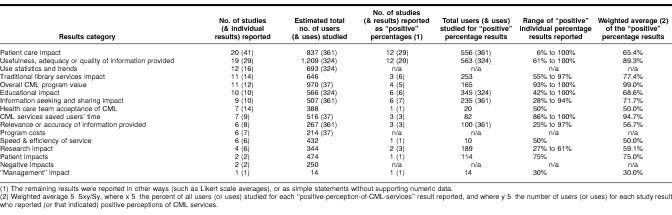

The results reported from these studies (which usually, but not always, correspond with the goals and hypotheses stated in the introductions to these articles) are shown in the last column of Table 4. These results statements have also been categorized and further summarized in Table 5. This analysis shows (in the second column) that twenty studies reported 41 specific ways in which CML services made an impact on the provision of patient care in these settings. Another, not entirely identical, nineteen studies included 29 reported results statements about the perceived usefulness, adequacy, or quality of the CML-provided information resources. Smaller, but still significant, groups of studies reported statistics and trends about the use of the CML services (12), the impact of CML services on traditional health sciences library services (11), the overall value of the CML program (11), the educational impact of the CML services (10), the health care teams' acceptance of the CML as a colleague (7), and the extent to which CML services saved users' time (7). The remaining eight categories of results, including potentially negative impacts of these services, were each reported in six or fewer studies.

Table 5 Reported results of single-program CML service evaluations

The remaining columns in Table 5 show (1) the total estimated number of users (or uses) of CML services represented in the combined results for each category across all the studies; (2) the combined total number of studies (and individual results statements) in each category that included a quantitative percentage of positive responses from the users studied; (3) the total estimated number of users (or uses) of CML services represented in those studies reporting numerical percentage positive results statements; (4) the positive percentage range reported in those results statements; and (5) a weighted average of all the percentage results reported in each category, using the number of users (or uses) with positive results in each study as the weighting factor. These statistics were derived and calculated from Table 4, which, in addition to the individual results statements listed in the last column, includes, in the fourth column, the number of individuals (or information resources uses) studied in each of these evaluation reports.

Although the numbers as presented here look precise, it is important to emphasize that in some cases the published articles provided only very general information about the numbers of individual CML-service users studied (estimates are indicated with question marks on Table 4). However, the figures in Table 5 do provide a fair estimate of the total relative numbers of health professionals (or their uses of CML services) included in these evaluation studies.

The combined total number of users studied, for each category of CML- service impact, ranged from 14 to about 1,200. Two studies also included evaluation data based on an evaluation form linked to the articles or other search results provided to users by CMLs (324 returned evaluations for the Staudt study, and 37 for the Tobia study). The percentages of positive impacts reported for individual result statements in all the studies ranged from 6% (for the proportion of CML service users in one study who felt that CML information contributed to avoiding hospital infections [Dodson]), to 100% for twelve different statements reporting study results in five of the categories on Table 5. The weighted averages of positive percentage results statements in each category with more than one study range from 57% to 99%.

This analysis points to the perceived usefulness and quality of the information resources provided by the CMLs as the strongest single impact of CML services as reported in these program evaluation studies. The combined evidence for this conclusion includes the relatively large cumulative number of studies (19) and results (29) reported, individual users (1,209) and uses (324) studied, and the weighted average positive results (89%) for the twelve studies with quantitative percentage results statements. The cumulative evidence supporting the conclusion that CML services have contributed to improved patient care by their health professional users is also relatively strong. This evidence includes 20 studies, 41 results statements, and a relatively large number of individual users (837) and uses (361) studied. However, the twelve studies reporting positive opinion percentages about the value of CML services for patient care have a significantly lower weighted average of about 65%.

While the cumulative evidence for other potential impacts of CML services from these studies is also generally positive, it is not strong since the numbers of studies, results reported, and users (and uses) studied are quite small for those categories compared with the usefulness and patient-care impact-study results. Potentially negative impacts of CML services were only reported in two of these thirty studies. Reid, studying about 150 clinician users in ten multidisciplinary health care teams, reported the problem of overwhelming case loads faced by clinicians who find little time to read, appraise, and apply the CML-provided information; Glassington, studying about 100 users in three multidisciplinary health care units, reported the problem of overcoming communication barriers to allow CMLs to become a more integral part of the multidisciplinary health care team.

DISCUSSION

Our goal in conducting this systematic review of the literature evaluating CML programs was to determine if the cumulative evidence would provide additional support for the hypothesis that CML services contribute to improved patient care or better performance by health care professionals or students. As expected, these results show very little support for this hypothesis, with only thirty-five studies published in the past thirty years using any kind of formal evaluation methods. In addition, the published evidence consists almost entirely of descriptive surveys of user opinions and inconsistent statistics measuring the quantity of CML services provided, usually for periods ranging from six to twelve months.

Comparative quantitative research methods or carefully and systematically structured qualitative research methods have been used very rarely, with only four studies using historically controlled before-and-after methods or comparison control groups. Thus, the closest approximation to a meta-analysis statistical summary of the cumulative evidence from these studies that could be derived was the weighted averages calculated from some study survey results stated as percentages (presented in Table 5). This cumulative evidence does help to support somewhat the perception that a large majority of CML program users do find the information resources provided useful and of good quality. A clear majority of these users also state that CML services have contributed in some way to improved patient care. However, no study to date has attempted to measure the direct or indirect impact of CML services on the outcomes of patient care (such as hospital length of stay, patient mortality, adverse drug effects, etc.), as the Klein study [92] did with hospital library services. No study provides more than unverified opinions of health care professionals and students about those potential impacts. Objective evidence for the positive impact of CML services at this level is still missing.

Another important problem mentioned frequently in the non-evaluative, descriptive literature on CML programs [93–96] is the need to justify the special professional training and other costs associated with providing a rather intense level of information services for small subsets of a total user population. These evaluative studies provide very little comparative data or other evidence to help justify the cost-effectiveness of CML services versus other methods of providing or promoting access to knowledge-based information in clinical, patient care settings. For example, they provide very little evidence to justify the cost-effectiveness of CML services in comparison to proposals for informationist services that would be provided by health professionals with doctorate degrees and much higher salary requirements. The two studies that do provide some cost-benefit evidence (Kidder and Demas) are not encouraging about the general level of understanding and willingness to support these services financially or politically. Carefully structured qualitative studies could be very revealing and helpful in understanding the factors that contribute to cost-effective CML service programs, but these are also almost entirely missing from the literature. The Lamb study gathered this kind of useful information in the form of CML diaries, but then failed to subject that data to a systematic or rigorous analysis.

Formal studies looking at more than one CML program have also been very rare, including only the Kidder survey of new medical school libraries and the Cimpl literature review in 1985. Finally, very few of these 35 evaluative studies even discussed actual or potential problems with CML services (Kidder, Cimpl, Demas, Reid, and Glassington). The Demas study came closest to providing a forthright analysis of negative data about the potential support for CML service programs in academic health sciences centers, but this was based only on surveyed opinions using short CML scenario statements.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

With so little cumulative evidence about the impact of CML services on the provision of health care and on the training of health professionals in clinical settings, what can be concluded about the potential future of such programs or the need for additional studies to guide the further development of these services? As is the case with most research, this systematic review of the evaluative studies of CML services conducted over the past thirty years raises many more questions than it answers. Clearly, there is some relatively strong evidence that these programs have been well accepted and liked by most of the targeted clinicians and students served. However, the total amount of such evidence is not great, most of it is descriptive rather than comparative or analytically qualitative, and it does not rise to the level of the “best evidence” called for to support evidence-based medicine or librarianship.

This review also suggests many additional questions that merit further study:

In what settings can CMLs work most effectively? Where are CML-health professional interactions most helpful, productive, and conducive to better patient outcomes (rounds, conferences, or others)?

The changing health care landscape, with more care being provided in outpatient settings, could dramatically change the need for, or the types of services needed from, CMLs. For example, none of the programs described or evaluated in the literature to date have been targeted at health professionals working in outpatient clinics.

What kind of work schedule for CMLs is most effective?

What is the optimal ratio of CMLs to health professionals served?

What training or skill sets are needed to make CMLs or informationists most effective? Some opinions and examples of interesting approaches are described in these studies (see, for example, Giuse), but almost no evidence is presented showing that one approach is more promising than another.

What is the optimum length of time over which a CML program should be evaluated? More trend analyses (such as Miller and Barbour) and before-and-after studies (such as Gunning and Eaton) could help to answer this question.

How effective are CMLs who anticipate information needs compared with those who just respond to direct questions from clinicians? What kind of clinical information need is most effectively anticipated?

What evaluation data gathering and analysis strategies are needed to allow program developers to effectively compare their outcomes with other CML programs?

Without the evidence provided from carefully researched answers to at least some of these questions as well as convincing analyses of the cost-benefit ratio for these services, it will be very difficult to justify the further development and growth of such services. Although continuing innovation and experimental new programs are valuable for exploring potential service strategies, standards are needed to consistently evaluate CML or informationist programs in the future. These need to include consistent data-gathering and analysis methods, comparable cost-benefit data, and standards for measuring patient care impacts and program value. A carefully structured multi-program study using such standards and including three to five of the best current CML or informationist programs could help define the true value of these services.

Whether such services continue to be provided by information professionals we call clinical medical librarians, or by a new cadre of professionals who combine the training of librarians with training in one or more of the health professions and call themselves informationists, is not as important for the future of these services as the need to study and answer some of the fundamental questions about the value of these services for patient care in clinical settings. If the true value (that is the cost-effectiveness) of CML services, by whatever name, can be clearly demonstrated with objective data about their effects on patient care, then financial and political support for these programs within health care organizations will follow naturally. However, much more high-quality research is needed to demonstrate the value of these services in comparison to other methods for supporting evidence-based health care in clinical settings.

Table 3 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Table 4 Continued

Footnotes

* Based on a presentation at MLA '03, the 103rd Annual Meeting of the Medical Library Association, San Diego, California, May 5, 2003.

Contributor Information

Kay Cimpl Wagner, Email: kcwagner@usd.edu.

Gary D. Byrd, Email: gdbyrd@buffalo.edu.

REFERENCES

- Algermissen V. Biomedical librarians in a patient care setting at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1974 Oct. 62(4):354–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GE. A decade of clinical librarianship. Clin Librn Q. 1982 Sep. 1(1):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cimpl K. Clinical medical librarianship: a review of the literature. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1985 Jan. 73(1):21–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist: a new health profession? Ann Intern Med. 2000 Jun 20. 132(12):996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutchak TS. Informationists and librarians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct. 88(4):391–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb GE. A decade of clinical librarianship. Clin Librn Q. 1982 Sep. 1(1):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Claman GG. Clinical medical librarians: what they do and why. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):454–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour GL, Young MN. Morning report: role of the clinical librarian. JAMA. 1986 Apr 11. 255(14):1921–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claman GG. Clinical medical librarians: what they do and why. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):454–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose NP, Hannigan GG. A clinical librarian program in a family medicine residency. J Fam Pract. 1982 Nov. 15(5):994998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden R. A clinical librarian program for oncology nursing at Roswell Park Memorial Institute. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Sep. 2(1):13–6. [Google Scholar]

- Miller N, Kaye D. The experience of a department of medicine with a clinical medical library service. J Med Educ. 1985 May. 60(5):367–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsted DD. The evolving role of clinical medical librarians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Jul. 77(3):299–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis JM, Shipley JM. Clinical medical librarianship [Letter]. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1990 Apr. 78(2):199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuse NB, Kafantaris SR, Miller MD, Wilder KS, Martin SL, Sathe NA, and Campbell JD. Clinical medical librarianship: the Vanderbilt experience. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998 Jul. 86(3):412–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert CM. Adapting clinical librarianship. Med Ref Serv Q. 1999 Spring. 18(1):69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome RN, Giuse NB, Gish KW, Sathe NA, and Dietrich MS. Information needs of clinical teams: analysis of questions received by the Clinical Informatics Consult Service. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Apr. 89(2):177–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt C, Halbrook B, and Brodman E. A clinical librarians' program: an attempt at evaluation. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1976 Apr. 64(2):236–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claman GG. Clinical medical librarians: what they do and why. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):454–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra RJ. Clinical medical librarian impact on patient care: a one-year analysis. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Jan. 80(1):19–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal M, Grizzle WE, Algermissen V, and Mowry RW. The success of a clinical librarian program in an academic autopsy pathology service. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993 May. 99(5):576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb G. Bridging the information gap. Hosp Libr. 1976 Nov 15. 1(10):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S, Malamud J, Stearns NS, and Moulton B. Preselecting literature for routine delivery to physicians in a community hospital-based patient care reading program. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1981 Apr. 69(2):236–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon G, Victory M, and Harvey S. Anticipating clinical information needs: preclinical primers for the clinical medical librarian. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1982 Apr. 70(2):239–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuller AB, Wessel CB, Ginn DS, and Martin TP. Quality filtering of the clinical literature by librarians and physicians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1993 Jan. 81(1):38–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach AA, Addington WW. The effects of an information specialist on patient care and medical education. J Med Educ. 1975 Feb. 50(2):176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JB, Byrd GB, Petersen KW, Algermissen V, and Tchobanoff JB. A role for the clinical medical librarian in continuing education. J Med Educ. 1978 Jun. 53(6):514–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis J, Hamburger S. The impact of the clinical medical librarian on medical education. J Med Educ. 1981 Oct. 56(10):860–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig SA, Graves KJ. The clinical librarian program as an integral component of graduate medical education. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Jun. 1(4):7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Turman LU, Koste JL, Horne AS, and Hoffman CE. A new role for the clinical librarian as educator. Med Ref Serv Q. 1997 Spring. 16(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning JE, Fierberg J, Goodchild E, and Marshall JR. Use of an information retrieval service in an obstretrics/gynecology residency program. J Med Educ. 1980 Feb. 55(2):120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand NL, Maynard CD, and Sprinkle MD. A comprehensive information service for an academic radiology department AJR. Am J Roentgenol. 1983 Nov. 141(5):1077–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobia RC. Clinical librarianship at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio Library. Clin Librn Q. 1984 Sep/Dec. 3(1/2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Glick J, Sullivan M. CML in a satellite library. Clin Librn Q. 1984 Sep/Dec. 3(1/2):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra RJ, Gluck EH. A clinical librarian program in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1992 Jul. 20(7):1038–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach AA, Addington WW. The effects of an information specialist on patient care and medical education. J Med Educ. 1975 Feb. 50(2):176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis J, Hamburger S. The impact of the clinical medical librarian on medical education. J Med Educ. 1981 Oct. 56(10):860–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AA III, Kolisch ME, and McBride ME. A system for the management of clinical information in orthopaedics. Clin Orthop 1982 Apr;(164):154–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelisse L. A clinical reference program in the Department of Medicine, Tufts-New England Medical Center Hospital. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):456–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunning JE, Fierberg J, Goodchild E, and Marshall JR. Use of an information retrieval service in an obstretrics/gynecology residency program. J Med Educ. 1980 Feb. 55(2):120–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AA III, , Kolisch Savit ME, and McBride ME. Clinical information coordinator: new information specialist role for medical librarians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1980 Oct. 68(4):367–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson S, Malamud J, Stearns NS, and Moulton B. Preselecting literature for routine delivery to physicians in a community hospital-based patient care reading program. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1981 Apr. 69(2):236–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates-Imah C, Goldschmidt RH, and Johnson MA. The clinical librarian: new team member for a family practice inpatient service. Fam Med. 1985 Nov–Dec. 17(6):262–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour GL, Young MN. Morning report: role of the clinical librarian. JAMA. 1986 Apr 11. 255(14):1921–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusher A. Getting evidence to the bedside: the role of the clinical librarian. In: Bakker S, ed. Libraries without limits: changing needs—changing roles, Proceedings of the Sixth European Conference of Medical and Health Libraries. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 1999:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Roach AA, Addington WW. The effects of an information specialist on patient care and medical education. J Med Educ. 1975 Feb. 50(2):176–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG, Neufeld VR. A randomized trial of librarian educational participation in clinical settings. J Med Educ. 1981 May. 56(5):409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose NP, Hannigan GG. A clinical librarian program in a family medicine residency. J Fam Pract. 1982 Nov. 15(5):994998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand NL, Maynard CD, and Sprinkle MD. A comprehensive information service for an academic radiology department AJR. Am J Roentgenol. 1983 Nov. 141(5):1077–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strube K. Can a clinical librarian serve a medical school faculty? Clin Librn Q. 1985 Jun. 3(4):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG, Hamilton JD. The clinical librarian and the patient: report of a project at McMaster University Medical Centre. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):420–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AA III, , Kolisch Savit ME, and McBride ME. Clinical information coordinator: new information specialist role for medical librarians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1980 Oct. 68(4):367–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG, Hamilton JD. The clinical librarian and the patient: report of a project at McMaster University Medical Centre. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Oct. 66(4):420–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billick P, Bresien P. The clinical librarian program at Saint Luke's Hospital, Cleveland. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Sep. 2(1):16–8. [Google Scholar]

- Glick J, Sullivan M. CML in a satellite library. Clin Librn Q. 1984 Sep/Dec. 3(1/2):5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Arcari RD. Clinical librarian program—cost recovery effort. Clin Librn Q. 1982 Dec. 1(2):7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kidder AJ. Clinical librarian program [Letter]. J Med Educ. 1982 Jun. 57(6):503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePres KA, Bloom VD. CML programs: a deterrent to library use? Clin Librn Q. 1983 Mar. 1(3):11–2. [Google Scholar]

- Grose NP, Hannigan GG. A clinical librarian program in a family medicine residency. J Fam Pract. 1982 Nov. 15(5):994998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbrook B. Clinical librarian programs: reflections on successes and failures. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Sep. 2(1):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hulkonen DA. Implications for clinical library service in academic medical libraries. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Mar. 1(3):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Faust J. A CML program which was spoiled by its own success. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Mar. 1(3):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Winant RM. The demise of a clinical library program and other possibilities. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Jun. 1(4):11–2. [Google Scholar]

- Demas JM, Ludwig LT. Clinical medical librarian: the last unicorn? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1991 Jan. 79(1):17–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacher LF. Clinical librarianship: its value in medical care. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Apr 17. 134(8):717–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor P. Determining the impact of health library services on patient care: a review of the literature. Health Info Libr J. 2002 Mar. 19(1):1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DN. The contribution of hospital library information services to clinical care: a study in eight hospitals. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1987 Oct. 5(4):291–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JG. The impact of the hospital library on clinical decision making: the Rochester study. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Apr. 80(2):169–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med 1994;69(6):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, and Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13. 312(7023):71–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collaboration. Preparing, maintaining and promoting the accessibility of systematic reviews of the effects of health care interventions. [Web document]. Oxford: UK Cochrane Centre, 2003. [rev. 28 Jul 2003; cited 12 Aug 2003]. <http://www.cochrane.org>. [Google Scholar]

- Mulrow C, Cook D. eds. . Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for health care decisions. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer CS, Dorsch JL. The evolving role of the librarian in evidence-based medicine. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1999 Jul. 87(3):322–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKibbon KA. Evidence-based practice. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998 Jul. 86(3):396–401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerome RN, Giuse NB, Gish KW, Sathe NA, and Dietrich MS. Information needs of clinical teams: analysis of questions received by the Clinical Informatics Consult Service. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2001 Apr. 89(2):177–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge JD. Evidence-based librarianship: an overview. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct. 88(4):289–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, and Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13. 312(7023):71–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalrymple PW. Knowledge management in the health sciences. In: Srikantaiah TK, Koenig M, eds. Knowledge management for information professionals. Medford, NJ: Information Today, Inc., 2000:389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist: a new health profession? Ann Intern Med. 2000 Jun 20. 132(12):996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff F, Florance V. The informationist [Letter]. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Feb 6. 134(3):253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutchak TS. Informationists and librarians. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct. 88(4):391–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd GD. Can the profession of pharmacy serve as a model for health informationist professionals? J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan. 90(1):68–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersh W. Medical informatics education: an alternative pathway for training informationists. J Med Libr Assoc. 2002 Jan. 90(1):76–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipman J, Homan M. Medicine's library lifeline. LibraryJournal.com Apr 1, 2003 [Web document]. New York, Library Journal, 2003. [rev. 1 Apr 2003; cited 12 Aug 2003]. <http://libraryjournal.reviewsnews.com/index.asp>. [Google Scholar]

- Winning A, Beverley C. Clinical librarianship: a systematic review. Hypothesis. 2001 Fall. 15(3):38–9. [Google Scholar]

- Winning MA, Beverley CA. Clinical librarianship: a systematic review of the literature. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun. 20(suppl 1):10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman CP, Owens DK, and Wyatt JC. Evaluation and technology assessment. In: Shortliffe EH, Perreault LE, eds. Medical informatics: computer applications in health care and biomedicine. New York: Springer, 2001:282–323. [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge JD. Evidence-based librarianship: an overview. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 2000 Oct. 88(4):289–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell CL, Rathe RJ. Meta-analysis: a tool for medical and scientific discoveries. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1992 Jul. 80(3):219–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek R, Pinnock C, and Phillips PA. Increasing access to evidence in an acute hospital setting through a clinical evidence researcher service, March 2002–May 2003 [abstract received via a personal electronic mail communication, 15 Apr 2003]. Daw Park, South Australia: Repatriation General Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- Winning MA, Beverley CA. Clinical librarianship: a systematic review of the literature. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun. 20(suppl 1):10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MS, Ross FV, Adams DL, and Gilbert CM. Effect of online literature searching on length of stay and patient care costs. Acad Med 1994;69(6):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcari RD. Clinical librarian program—cost recovery effort. Clin Librn Q. 1982 Dec. 1(2):7–10. [Google Scholar]

- DePres KA, Bloom VD. CML programs: a deterrent to library use? Clin Librn Q. 1983 Mar. 1(3):11–2. [Google Scholar]

- Halbrook B. Clinical librarian programs: reflections on successes and failures. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Sep. 2(1):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Winant RM. The demise of a clinical library program and other possibilities. Clin Librn Q. 1983 Jun. 1(4):11–2. [Google Scholar]