Abstract

Pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria depends on a type III secretion (T3S) system which translocates effector proteins into eukaryotic cells and is associated with an extracellular pilus and a translocon in the host plasma membrane. T3S substrate specificity is controlled by the cytoplasmic switch protein HpaC, which interacts with the C-terminal domain of the inner membrane protein HrcU (HrcUC). HpaC promotes the secretion of translocon and effector proteins but prevents the efficient secretion of the early T3S substrate HrpB2, which is required for pilus assembly. In this study, complementation assays with serial 10-amino-acid HpaC deletion derivatives revealed that the T3S substrate specificity switch depends on N- and C-terminal regions of HpaC, whereas amino acids 42 to 101 appear to be dispensable for the contribution of HpaC to the secretion of late substrates. However, deletions in the central region of HpaC affect the secretion of HrpB2, suggesting that the mechanisms underlying HpaC-dependent control of early and late substrates can be uncoupled. The results of interaction and expression studies with HpaC deletion derivatives showed that amino acids 112 to 212 of HpaC provide the binding site for HrcUC and severely reduce T3S when expressed ectopically in the wild-type strain. We identified a conserved phenylalanine residue at position 175 of HpaC that is required for both protein function and the binding of HpaC to HrcUC. Taking these findings together, we concluded that the interaction between HpaC and HrcUC is essential but not sufficient for T3S substrate specificity switching.

INTRODUCTION

Gram-negative plant-pathogenic bacteria of the genus Xanthomonas infect a large number of mono- and dicotyledonous plants and cause severe yield losses worldwide (43). In most cases, bacteria utilize a type III secretion (T3S) system to successfully conquer their respective host plants (12). T3S systems are essential pathogenicity factors of many Gram-negative plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria and mediate the translocation of bacterial proteins, also referred to as type III effector proteins, into the cytosol of eukaryotic cells (12, 31, 60). Type III effector proteins presumably interfere with host cellular functions such as basal immune responses, to the benefit of the pathogen, and thus promote bacterial multiplication (5, 12, 36, 69).

In our laboratory, we study Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, which is the causal agent of bacterial spot disease in pepper and tomato plants and one of the model systems for the analysis of bacterial pathogenicity factors (12). During natural infection, bacteria enter the plant tissue via openings on the plant surface, such as stomata, hydathodes, or wounds, and colonize the intercellular spaces. Bacterial multiplication depends on the T3S system, which injects approximately 30 effector proteins (Xops [Xanthomonas outer proteins]) into the plant cell and is encoded by the chromosomal hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity) gene cluster (10, 69). The hrp gene cluster contains 25 genes organized into eight transcriptional units, whose expression is activated by at least two regulatory proteins, HrpG and HrpX, that are encoded outside the cluster (8, 16, 74, 76, 78). Eleven hrp gene products (designated Hrc [for Hrp conserved]) are conserved among plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria (32). They presumably constitute the main components of the T3S system, suggesting that the architecture of the membrane-spanning secretion apparatus is similar in different bacterial species. Notably, translocation-associated T3S systems are evolutionarily related to the bacterial flagellum, which is also referred to as a T3S system (22). In contrast to flagellar T3S systems, which are connected via an extracellular hook to the bacterial filament, translocation-associated T3S systems are extended by an extracellular pilus (plant pathogens) or needle (animal pathogens) that serves as a transport channel for secreted proteins to the host-pathogen interface (10, 31, 32). The pilus of plant pathogens is considerably longer (up to 2 μm) than the needle (40 to 80 nm) of animal pathogens and presumably spans the plant cell wall, which is a major obstacle for the translocation of effector proteins by invading microbes (31, 38). Effector protein translocation by both plant- and animal-pathogenic bacteria is mediated by the channel-like T3S translocon of bacterial origin, which inserts into the host plasma membrane (11, 18).

T3S systems secrete different sets of substrates, including extracellular components of the secretion apparatus and effector proteins (31). T3S and/or translocation of bacterial proteins often depends on a signal within the N-terminal 15 to 50 residues that is not conserved on the amino acid level (3, 44, 59, 64, 65). Furthermore, in many cases, specialized bacterial cytoplasmic chaperones are involved that bind to secretion substrates and promote their stability and/or secretion (27, 58). Experimental evidence suggests that T3S chaperones target secreted proteins to the cytoplasmic ATPase of the T3S system at the inner bacterial membrane (2, 30, 45, 70).

Given the architecture of translocation-associated and flagellar T3S systems, it is assumed that the assembly of extracellular components of the secretion apparatus precedes effector protein translocation, suggesting a hierarchical process (19, 31, 73). Components of the extracellular pilus are therefore presumably secreted prior to translocon and effector proteins, which implies that the substrate specificity of the T3S system switches from “early” to “late” substrates. For X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, it was proposed that the secretion of the pathogenicity factor HrpB2, which is required for pilus assembly, precedes the secretion of the translocon protein HrpF and effector proteins (48, 62). To date, the molecular mechanisms underlying the T3S substrate specificity switch have been studied intensively in animal-pathogenic bacteria. It has been shown that the switch depends on secreted regulatory proteins, designated T3S substrate specificity switch (T3S4) proteins and including, e.g., YscP from Yersinia spp., Spa32 from Shigella flexneri, and FliK from the flagellar T3S system (1, 35, 50, 53, 66). T3S4 proteins share limited amino acid sequence similarity with each other but contain a structurally conserved C-terminal domain, termed the T3S4 domain, which is presumably crucial for protein function (1, 9, 52, 56). Experimental evidence reported for Spa32 and FliK suggests that T3S4 proteins interact with the C-terminal cytoplasmic domains of members of the conserved FlhB/YscU family of inner membrane proteins, which are proposed to be involved in the recognition of T3S substrates (9, 54, 55). FlhB, YscU, and their homologs contain four transmembrane helices and a C-terminal cytoplasmic region that is autocatalytically cleaved between the asparagine and proline residues of the conserved NPTH (letters refer to amino acids) motif. The cleavage event involves the cyclization of the asparagine residue and results in a reorientation of the PTH loop (6, 21, 28, 42, 49, 79, 81). It is assumed that binding of T3S4 proteins to the C-terminal cleavage products of FlhB/YscU family members leads to a conformational change and thus to a switch in T3S substrate specificity. This model is corroborated by the finding that T3S4 mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli can be restored to the wild-type phenotype by extragenic suppressor mutations in the C-terminal regions of FlhB, YscU, and the homologous EscU protein, respectively (23, 41, 80, 81).

To date, little is known about the mechanisms underlying the postulated T3S substrate specificity switch in plant-pathogenic bacteria. For X. campestris pv. vesicatoria, mutant studies revealed that T3S is presumably controlled by the products of hpa (hrp-associated) genes that are located in or next to the hrp gene cluster and contribute to the host-pathogen interaction (13, 14, 33, 47, 48). We have previously shown that HpaB acts as a general T3S chaperone that promotes the efficient secretion and translocation of effector proteins and presumably targets them to the T3S-associated ATPase HrcN (13, 14, 45). HpaB interacts with the cytoplasmic HpaC protein, which is an additional control protein of the T3S system and promotes the secretion of translocon and effector proteins (14). Interestingly, HpaC also prevents the efficient secretion of HrpB2, which is presumably one of the first substrates that travel the T3S system (48, 62, 75). Thus, HpaC differentially regulates the secretion of early and late substrates and therefore presumably induces a switch in the T3S substrate specificity, similar to known T3S4 proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria. A possible role of HpaC as a T3S4 protein was supported by the finding that HpaC interacts with the C-terminal domain of HrcU (HrcUC), which is a member of the FlhB/YscU protein family (14, 48). Binding of HpaC to HrcUC depends on the NPTH motif of HrcU and presumably occurs prior to HrcU cleavage (46). We recently demonstrated that a point mutation (Y318D; exchange of the tyrosine residue at position 318 with aspartate) in HrcUC suppresses the hpaC mutant phenotype. This implies that the HpaC-mediated T3S substrate specificity switch depends on a conformational change in HrcUC that is induced upon binding to HpaC (46). Interestingly, the Y318D mutation in HrcUC abolishes the efficient binding of HpaC, suggesting that the postulated conformational change leads to the release of HrcUC-bound HpaC (46).

In this study, we aimed at the identification of functional protein regions in HpaC. For this purpose, we introduced serial 10-amino-acid deletions into HpaC and analyzed the corresponding HpaC deletion derivatives for the ability to complement the hpaC mutant phenotype and to interact with HrcUC. We show that the N- and C-terminal regions of HpaC are crucial for protein function and that amino acids 112 to 212 provide the binding site for HrcUC. The analysis of derivatives with single point mutations led to the identification of a conserved phenylalanine residue in the C-terminal region of HpaC that contributes to both the interaction with HrcUC and the HpaC-dependent substrate specificity switch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli cells were grown at 37°C in lysogeny broth (LB) or Super medium (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains were cultivated at 30°C in nutrient yeast-glycerol (NYG) medium (20) or in minimal medium A (4) supplemented with sucrose (10 mM) and Casamino Acids (0.3%). Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by electroporation and into X. campestris pv. vesicatoria by conjugation, using pRK2013 as a helper plasmid in triparental matings (29). Antibiotics were added to the media at the following final concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; rifampin, 100 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; and gentamicin, 7.5 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains | ||

| 85-10 | Pepper race 2; wild type; Rifr | 17, 39 |

| 85-10 ΔhpaC | hpaC deletion mutant of strain 85-10 | 14 |

| 85* | 85-10 derivative containing the hrpG* mutation | 77 |

| 85* ΔhpaC | hpaC deletion mutant of strain 85* | 14 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany |

| DH5α | F−recA hsdR17(rK− mK−) φ80dlacZΔM15 | Bethesda Research Laboratories, Bethesda, MD |

| DH5α λpir | F−recA hsdR17(rK− mK−) φ80dlacZΔM15 λpir | 51 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBBR1MCS-5 | Broad-host-range vector with lac promoter; Gmr | 40 |

| pBluescript (II) KS | Phagemid, pUC derivative; Apr | Stratagene |

| pBRM | Golden Gate-compatible derivative of pBBR1MCS-5 | 68 |

| pBRMhpaC | pBRM derivative encoding HpaC-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ62–91 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ42–101 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ42–101-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ164–168 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ164–168-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ171–175 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ171–175-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ2-111 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ2-111-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCΔ2–121 | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCΔ2–121-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCL164A | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCL164A–c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCL171A | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCL171A-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCL173A | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCL173A-c-Myc | This study |

| pBRMhpaCF175A | pBRM derivative encoding HpaCF175A-c-Myc | This study |

| pDSK604 | Broad-host-range vector containing triple lacUV5 promoter; Smr | 26 |

| pDGW4M | Derivative of pDSK602 containing attR1-Cmr-ccdB-attR2 upstream of 4× c-Myc epitope-encoding sequence | 47 |

| pDGW4MhpaC | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaC-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ2–11 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ2–11-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ12–21 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ12–21-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ22–31 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ22–31-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ32–41 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ32–41-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ42–51 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ42–51-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ62–71 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ62–71-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ72–81 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ72–81-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ82–91 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ82–91-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ92–101 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ92–101-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ102-111 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ102–111-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ112–121 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ112–121-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ122–131 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ122–131-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ132–141 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ132–141-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ142–151 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ142–151-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ152–161 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ152–161-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ162–171 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ162–171-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ172–181 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ172–181-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ182–191 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ182–191-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ192–201 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ192–201-c-Myc | This study |

| pDGW4MhpaCΔ202–212 | pDGW4M derivative encoding HpaCΔ202–212-c-Myc | This study |

| pDMhrpB2 | pDSK604 derivative encoding HrpB2-c-Myc | 48 |

| pGEX-2TKM | GST expression vector; Ptac GST lacIq pBR322 ori Apr; derivative of pGEX-2TK with polylinker of pDSK604 | Stratagene; 26 |

| pGhpaC | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HpaC | 14 |

| pGhpaC1–118 | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HpaC1–118 | This study |

| pGhrcU255–357 | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HrcU255–357 | 48 |

| pGhrcU255–357/Y318D | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HrcU255–357/Y318D | 46 |

| pGhrcU265–357 | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HrcU265–357 | 46 |

| pGhrpB2 | pGEX-2TKM derivative encoding GST-HrpB2 | This study |

| pLAFR3 | RK2 replicon; Mob+ Tra− Plac Tcr | 67 |

| pLhpaCΔ2–111 | pLAFR3 derivative encoding HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc | This study |

| pRK2013 | ColE1 replicon; TraRK+ Mob+ Kmr | 29 |

| pUC119 | ColE1 replicon; Apr | 71 |

Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin; Sm, spectinomycin; Gm, gentamicin; r, resistant.

Plant material and plant inoculations.

The nearly isogenic pepper cultivars Early Cal Wonder (ECW) and ECW-10R (39, 57) were grown and inoculated with X. campestris pv. vesicatoria as described previously (8). Briefly, bacteria were inoculated into the intercellular spaces of leaves with a needleless syringe at a concentration of 2 × 108 CFU ml−1 in 1 mM MgCl2 if not stated otherwise. The appearance of disease symptoms and the hypersensitive response (HR) were scored over a period of 1 to 9 days postinoculation (dpi). For better visualization of the HR, leaves were bleached in 70% ethanol. Experiments were repeated at least two times.

Generation of expression constructs.

For the generation of an hpaC-c-myc expression construct, hpaC was amplified by PCR from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10. The amplicon was inserted into pENTR/D-TOPO, giving pENTRhpaC, and recombined into pDGW4M by using Gateway technology. pDGW4M is a derivative of the low-copy-number broad-host-range vector pDSK602 and contains the attR sites, the chloramphenicol resistance and ccdB genes, and the 4× c-Myc-encoding sequence of vector pGWB16 inserted into the EcoRI/HindIII sites downstream of a 3× lacUV promoter (Table 1) (47). Expression constructs encoding HpaC-c-Myc derivatives with 10-amino-acid deletions were generated by PCR, using pENTRhpaC as the template and phosphorylated primers that were designed to introduce the desired deletions and anneal back to back to the template. PCRs were performed using Phusion high-fidelity polymerase (New England BioLabs, Frankfurt, Germany). The amplicons were religated and transformed into E. coli, and the inserts were then recombined into pDGW4M. For the generation of HpaC-c-Myc derivatives containing 5-, 30-, and 60-amino-acid deletions or single point mutations in the C-terminal region, we used the Golden Gate cloning technique. For this method, hpaC was inserted into the SmaI site of vector pUC57 in a restriction-ligation reaction (7) and subsequently cloned into the Golden Gate-compatible vector pBRM as described previously, downstream of a single lac promoter (24, 68). hpaC-c-myc deletion and point mutant derivatives were generated by PCR, using pUC57hpaC as the template and phosphorylated primers as described above. The amplicons were religated and transformed into E. coli, and the inserts were then cloned into pBRM. To generate hpaCΔ2–111-c-myc and hpaCΔ2–121-c-myc expression constructs, corresponding hpaC fragments were amplified by PCR and cloned into pBRM. For the construction of pLhpaCΔ2–111, hpaCΔ2–111-c-myc was excised from pBRMhpaCΔ2–111 and ligated into the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pLAFR3, downstream of a single lac promoter. To obtain an expression construct encoding GST-HrpB2, hrpB2 was amplified by PCR and cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pGEX-2TKM. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Protein secretion studies and immunoblot analysis.

In vitro secretion assays were performed as described previously (63). Briefly, bacteria were incubated in secretion medium, and equal amounts of bacterial total cell extracts and culture supernatants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting (63). In this study, we used polyclonal antibodies specific for HrpF (15), AvrBs3 (37), and HrpB2 (62) and monoclonal anti-c-Myc (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) and anti-glutathione S-transferase (anti-GST; GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, and anti-goat antibodies (GE Healthcare) were used as secondary antibodies. Antibody reactions were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence. Experiments were repeated at least two times. Blots were routinely incubated with an antibody specific for the intracellular protein HrcN to ensure that no bacterial lysis had occurred (62).

GST pulldown assays.

For GST pulldown assays, GST and GST fusion proteins were synthesized in E. coli BL21(DE3). Bacterial cells from 50-ml cultures were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and broken with a French press. Insoluble cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and soluble GST and GST fusion proteins were immobilized on a glutathione Sepharose matrix according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare). Unbound proteins were removed by washing twice with PBS, and the glutathione Sepharose matrix was incubated with 600-μl E. coli cell lysates containing c-Myc epitope-tagged derivatives of the putative interaction partners for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound proteins were removed by washing four times with PBS, and bound proteins were eluted with 10 mM reduced glutathione at room temperature for 2 h. Ten microliters of total protein lysate and 20 μl of eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Generation and functional characterization of HpaC deletion derivatives.

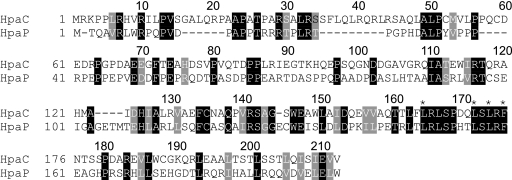

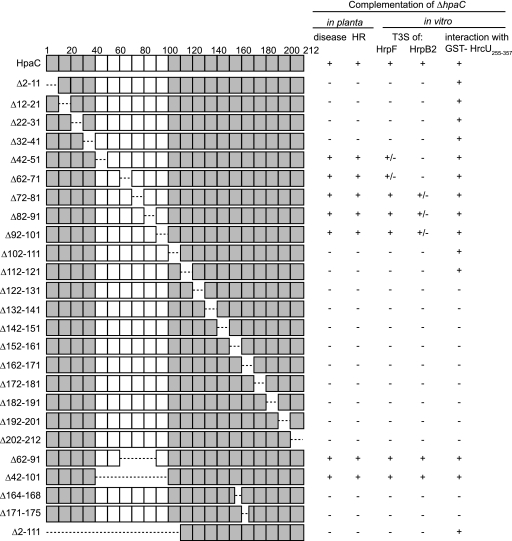

HpaC is a T3S4 protein from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10 (48). Comparative sequence analysis revealed that HpaC shares 28% amino acid sequence identity with HpaP, a protein with a predicted C-terminal T3S4 domain from the plant-pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum (Fig. 1) (1). However, no sequence homology between HpaC and known T3S4 proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria could be detected. To identify functional regions in HpaC, we generated expression constructs encoding HpaC-c-Myc and serial 10-amino-acid deletion derivatives thereof under the control of the lac promoter. Unfortunately, we did not obtain the entry clone and the expression construct encoding HpaCΔ52–61-c-Myc. The other 20 expression constructs could be generated (Fig. 2) and were introduced into X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10 and 85-10 ΔhpaC. For the analysis of in planta phenotypes, bacteria were inoculated into leaves of susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants. ECW-10R pepper plants carry the Bs1 resistance gene and induce the HR upon recognition of the type III effector AvrBs1 that is delivered by strain 85-10 (26, 61). The HR is a rapid local cell death at the infection site that restricts bacterial ingress and is activated upon detection of individual effector proteins (also termed avirulence [Avr] proteins) by the plant surveillance system (34).

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment of HpaC from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria and HpaP from R. solanacearum. The amino acid sequences of HpaC from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10 (GenBank accession number CAJ22055) and HpaP from R. solanacearum strain GMI1000 (GenBank accession number NP_522423) were aligned using ClustalW2 (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html). Conserved amino acids are highlighted in black, and amino acids with similar chemical properties are shown in gray. Numbers refer to amino acid positions. Amino acids of HpaC that were replaced by alanine in this study are marked by asterisks.

Fig. 2.

Identification of functional protein regions in HpaC. The figure gives an overview of the HpaC deletion derivatives that were analyzed in this study. HpaC and derivatives thereof are represented by rectangles; single boxes refer to regions of 10 amino acids, and dashed lines refer to deletions. Numbers indicate amino acid positions. Essential protein regions of HpaC are shaded in gray. C-terminally c-Myc epitope-tagged derivatives of HpaC were analyzed in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strain 85-10 ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) for the ability to complement the hpaC mutant phenotype with respect to disease symptom formation and HR induction in susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants, respectively. For the analysis of HrpF and HrpB2 secretion, strains 85* and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) carrying HpaC-c-Myc or deletion derivatives thereof were incubated in secretion medium. To study the interaction of HpaC-c-Myc and deletion derivatives thereof with GST-HrcU255–357, we performed GST pulldown assays as shown in Fig. 4. +, wild-type symptom formation in planta, wild-type levels of HrpF and HrpB2 secretion, and an interaction of HpaC-c-Myc derivatives with GST-HrcU255–357; −, reduced symptom formation in planta, reduced HrpF secretion and oversecretion of HrpB2, and no detectable interaction of HpaC-c-Myc derivatives with GST-HrcU255–357; +/−, intermediate secretion levels (see Fig. 3).

As expected, strain 85-10 induced disease symptoms, so-called water-soaked lesions, in ECW and the HR in ECW-10R pepper plants, while symptom formation was severely reduced with strain 85-10 ΔhpaC (summarized in Fig. 2) (14). The hpaC mutant phenotype was complemented by HpaC-c-Myc and deletion derivatives lacking amino acids 42 to 51, 62 to 71, 72 to 81, 82 to 91, and 92 to 101 (Fig. 2). In contrast, HpaC-c-Myc derivatives carrying 10-amino-acid deletions within the N-terminal (amino acids 2 to 41) or C-terminal (amino acids 102 to 212) protein region did not complement the hpaC mutant phenotype (Fig. 2). Lack of complementation was not caused by a dominant-negative effect, because HpaC-c-Myc derivatives did not alter in planta phenotypes when they were expressed ectopically in strain 85-10 (data not shown). Immunoblot analyses using a c-Myc epitope-specific antibody revealed comparable levels of all HpaC derivatives in protein extracts of strains 85-10 and 85-10 ΔhpaC (data not shown) (see Fig. 3). We therefore concluded that the N- and C-terminal protein regions of HpaC are essential for protein function, whereas the central region is dispensable for the contribution of HpaC to bacterial pathogenicity. This hypothesis was confirmed by the finding that additional HpaC deletion derivatives, lacking amino acids 62 to 91 and 42 to 101, complemented the mutant phenotypes of strain 85-10 ΔhpaC (Fig. 2).

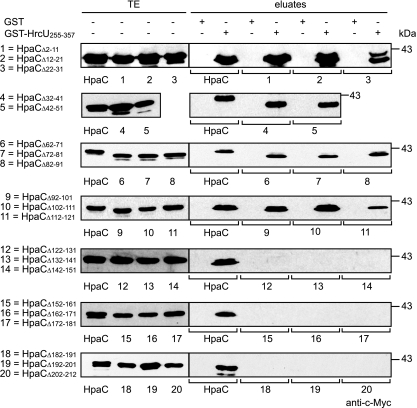

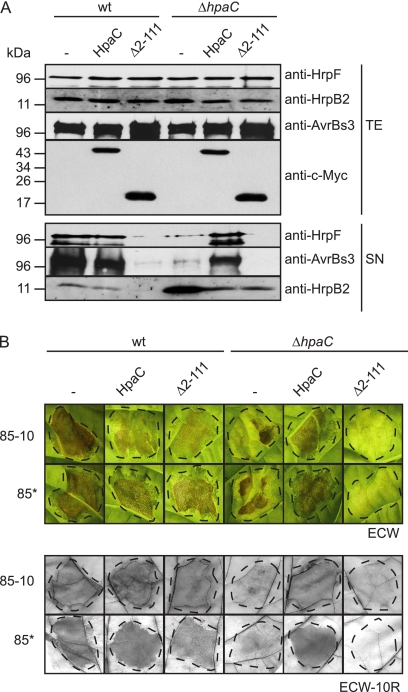

Fig. 3.

N- and C-terminal regions of HpaC contribute to the control of HrpF and HrpB2 secretion. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85* (wt) and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) containing the empty vector (−), HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC), or deletion derivatives thereof, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using HrpF-, HrpB2-, and c-Myc epitope-specific antibodies as indicated. The upper signal detected by the HrpF-specific antibody corresponds to HrpF, and the lower signal corresponds to degradation products.

We also analyzed the effects of five-amino-acid deletions in the C-terminal region of HpaC. HpaC-c-Myc derivatives deleted in amino acids 164 to 168 and 171 to 175, which are strictly conserved between HpaC and HpaP (Fig. 1), did not complement the in planta mutant phenotypes of strain 85-10 ΔhpaC (Fig. 2). This is in agreement with our finding that the C-terminal region of HpaC is required for protein function. Similar phenotypes were observed with 85* strains, which contain a constitutively active version of the key regulatory gene hrpG (hrpG*). 85* strains express T3S genes under noninducing conditions, which is key for the analysis of T3S (77). The presence of hrpG* leads to faster plant reactions in both susceptible and resistant plants without affecting in planta bacterial growth (77). Furthermore, hrpG* did not alter the ability of HpaC deletion derivatives to complement the hpaC mutant phenotype (data not shown).

N- and C-terminal regions of HpaC are essential for the T3S substrate specificity switch.

In addition to plant infection assays, we analyzed the contributions of HpaC deletion derivatives to T3S. For this purpose, strains 85* and 85* ΔhpaC carrying empty vector or expression constructs encoding HpaC-c-Myc and deletion derivatives thereof were incubated in secretion medium, and total cell extracts and culture supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies specific for the c-Myc epitope and the translocon protein HrpF. As expected, HrpF was detected in the culture supernatant of strain 85* (Fig. 3). HrpF secretion was severely reduced in strain 85* ΔhpaC and could be restored by HpaC-c-Myc, HpaCΔ72–81-c-Myc, HpaCΔ82–91-c-Myc, HpaCΔ92–101-c-Myc, HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc, and HpaCΔ42–101-c-Myc (Fig. 3). HpaCΔ42–51-c-Myc and HpaCΔ62–71-c-Myc only partially complemented the HrpF secretion deficiency of strain 85* ΔhpaC (Fig. 2 and 3). In contrast, HrpF secretion was not restored by HpaC derivatives with deletions within the N-terminal 41 or the C-terminal 111 amino acids, which coincides with the results of our phenotypic studies (Fig. 2 and 3). As previously observed for the wild-type protein, HpaC-c-Myc derivatives carrying 10-amino-acid deletions were not detected in the culture supernatant, suggesting that they are not secreted by the T3S system (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

We also analyzed the secretion of the early T3S substrate HrpB2, which is hardly detectable in the supernatant of strain 85* but is oversecreted in the absence of hpaC, as shown previously (Fig. 3) (48). HpaC-c-Myc, HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc, and HpaCΔ42–101-c-Myc restored wild-type levels of HrpB2 secretion in strain 85* ΔhpaC, whereas HpaCΔ72–81-c-Myc, HpaCΔ82–91-c-Myc, and HpaCΔ92–101-c-Myc partially complemented the HrpB2 oversecretion (Fig. 2 and 3). In contrast, all other HpaC-c-Myc deletion derivatives, including HpaCΔ42–51-c-Myc and HpaCΔ62–71-c-Myc, which complemented the HrpF secretion deficiency (see above), did not affect oversecretion of HrpB2 by strain 85* ΔhpaC (Fig. 2 and 3). Taken together, we concluded from our results that the N-terminal 41 and the C-terminal 111 amino acids of HpaC are important for bacterial virulence and HpaC-dependent control of HrpF secretion. Furthermore, our data suggest that secretion of HrpF and HrpB2 is controlled by independent mechanisms that can be uncoupled.

The HrcUC-binding site is located in the C-terminal region of HpaC.

We have previously shown that HpaC interacts with the C-terminal domain of the FlhB/YscU homolog HrcU (HrcUC) (48). To localize the HrcUC-binding site in HpaC, we performed in vitro pulldown assays using a fusion protein between GST and HrcUC (amino acids 255 to 357; GST-HrcU255–357), which contains the NPTH motif and has been shown to interact with HpaC (48). GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with bacterial lysates containing HpaC-c-Myc or deletion derivatives thereof. As expected, HpaC-c-Myc was detected in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 but not in that of GST (Fig. 4; summarized in Fig. 2). Similarly, HpaC-c-Myc derivatives containing 10-amino-acid deletions within the N-terminal or central protein regions (amino acids 2 to 121) coeluted with GST-HrcU255–357 (Fig. 4). However, reduced amounts of HpaCΔ112–121-c-Myc were detected in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 compared with those of HpaC-c-Myc, suggesting that amino acids 112 to 121 contribute to the efficient interaction of HpaC with HrcUC (Fig. 4). HpaC deletion derivatives containing 5- or 10-amino-acid deletions in the region spanning amino acids 122 to 212 were not detectable in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357, suggesting that the C-terminal 90 amino acids of HpaC are essential for the interaction with HrcUC (Fig. 4 and 5 A).

Fig. 4.

Protein-protein interaction studies with HrcUC and HpaC deletion derivatives. GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were immobilized on glutathione Sepharose and incubated with E. coli lysates containing HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC) or HpaC-c-Myc deletion derivatives, as indicated. Total cell extracts (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using a c-Myc epitope-specific antibody. Blots were routinely incubated with a GST-specific antibody to ensure stable synthesis of GST and GST fusion proteins (data not shown).

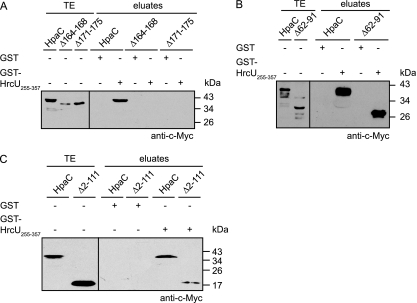

Fig. 5.

The C-terminal region of HpaC provides the binding site for HrcUC. (A) The interaction between HpaC and HrcUC depends on conserved amino acids in the C-terminal region of HpaC. Immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC), HpaCΔ164–168-c-Myc (Δ164–168), or HpaCΔ171–175-c-Myc (Δ171–175), as indicated. Total cell extracts (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using a c-Myc epitope-specific antibody. (B) The central region of HpaC is dispensable for the interaction with HrcUC. Immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC) and HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc (Δ62–91), and total cell extracts and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A. (C) Amino acids 112 to 212 of HpaC are sufficient for binding of HrcUC. Immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC) and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (Δ2–111). Total cell extracts and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A. Blots were routinely incubated with a GST-specific antibody to ensure stable synthesis of GST and GST fusion proteins (data not shown).

To confirm this finding and to investigate whether the C-terminal region of HpaC is sufficient for the interaction with GST-HrcU255–357, we analyzed a possible interaction of HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc with GST-HrcU255–357 (note that an HpaC-c-Myc derivative spanning amino acids 122 to 212 was unstable and therefore unavailable). Figure 5B and C show that both HpaCΔ62–91-c-Myc and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc were detected in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 but not in that of GST. This suggests that the N-terminal and central regions of HpaC are dispensable for the interaction with HrcUC.

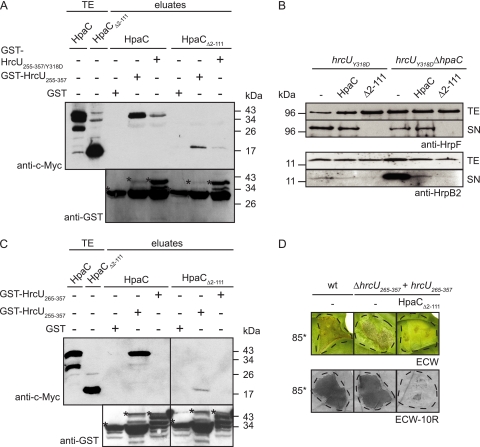

HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc exerts a dominant-negative effect on T3S.

Next, we analyzed whether ectopic expression of the C-terminal region of HpaC which provides the HrcUC-binding site would be sufficient to induce the substrate specificity switch in an hpaC deletion mutant. Notably, HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc did not complement strain 85* ΔhpaC with respect to its in planta and HrpF secretion phenotypes (Fig. 2 and 6). However, HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc restored wild-type levels of HrpB2 secretion in strain 85* ΔhpaC (Fig. 6A). This was presumably caused by a dominant-negative effect of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc on T3S, because the presence of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc in strains 85* and 85* ΔhpaC led to a severe reduction in the secretion of HrpF (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained for the secretion of the effector protein AvrBs3, which was expressed ectopically in strains 85* and 85* ΔhpaC, suggesting that HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc exerts a general negative effect on T3S (Fig. 6A). HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc was the only HpaC derivative with a dominant-negative effect on T3S and pathogenicity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Notably, however, when bacteria were inoculated into susceptible and resistant pepper plants, ectopic expression of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc did not significantly affect the plant reactions to infections with strains 85-10 and 85*. This result implies that the reduced T3S levels were sufficient for pathogenicity (Fig. 6B). In contrast, ectopic expression of hpaCΔ2-111-c-myc in an hpaC deletion mutant strain led to reduced disease symptoms which were visible at 8 to 9 dpi (Fig. 6B). We therefore speculate that the dominant-negative effect of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc on pathogenicity is visible only with a weak pathogen such as the hpaC deletion mutant.

Fig. 6.

Ectopic expression of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc exerts a negative effect on T3S and pathogenicity. (A) T3S assays with X. campestris pv. vesicatoria carrying HpaC-c-Myc and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc expression constructs. Strains 85* (wt) and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) carrying the empty vector (−) or expression constructs encoding HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC) and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (Δ2-111), as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using HrpF-, HrpB2-, AvrBs3-, and c-Myc epitope-specific antibodies. AvrBs3 was expressed ectopically in wild-type and ΔhpaC strains. (B) Infection studies with HpaC and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10 (wt), 85-10 ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC), 85* (wt), and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) carrying the empty vector (−) or expression constructs encoding HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC) and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (Δ2-111), as indicated, were inoculated at a bacterial density of 1 × 108 CFU/ml into leaves of susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants. For the analysis of hrpG* derivatives in ECW pepper plants, the inoculation density was lowered to 2 × 107 CFU/ml. Disease symptoms were photographed at 7 dpi (85-10 derivatives) and 8 dpi (85* derivatives). For better visualization of the HR, leaves were bleached in ethanol at 1 dpi. Dashed lines mark the infiltrated areas. We have previously observed that disease symptom formation by hpaC deletion mutants is delayed but not completely abolished (14).

We also investigated whether HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc depends on the interaction with HrcUC to interfere with T3S. For this purpose, we analyzed T3S in strain 85* hrcU(Y318D), which contains a point mutation (Y318D) in HrcUC that has been shown to suppress the hpaC mutant phenotype and prevent the efficient interaction between HrcUC and HpaC (46). Similar to HpaC-c-Myc, HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc did not interact efficiently with GST-HrcU255–357/Y318D in GST pulldown assays (Fig. 7 A). However, when strains 85* hrcU(Y318D) and 85* hrcU(Y318D) ΔhpaC carrying the empty vector, HpaC-c-Myc, or HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc were incubated in secretion medium, the secretion of HrpF and HrpB2 was severely reduced in the presence of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc but not HpaC-c-Myc, suggesting that HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc exerts a dominant-negative effect on T3S even in the absence of an efficient interaction with HrcUC (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

The dominant-negative effect of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc does not depend on efficient interaction with HrcUC. (A) The interaction between HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc and HrcUC is significantly reduced in the presence of a Y318D mutation in HrcUC. Immobilized GST, GST-HrcU255–357, and GST-HrcU255–357/Y318D were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc. Total cell extracts (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using c-Myc epitope- and GST-specific antibodies, respectively. GST and GST fusion proteins are marked by asterisks, and the lower bands correspond to degradation products. (B) HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc exerts a negative effect on T3S in hrcU(Y318D) mutants. Strains 85* hrcU(Y318D) (hrcUY318D) and 85* hrcU(Y318D) ΔhpaC (hrcUY318DΔhpaC) carrying the empty vector (−), HpaC-c-Myc, or HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc, as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using HrpF- and HrpB2-specific antibodies, respectively. (C) Interaction studies with HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc and HrcU265–357. Immobilized GST, GST-HrcU255–357, and GST-HrcU265–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc, and total cell extracts and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A. (D) HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc reduces in planta symptom formation by strain 85* ΔhrcU265–357 carrying HrcU265–357. Strain 85* (wt) carrying the empty vector (−) and strain 85* ΔhrcU265–357 expressing hrcU265–357 (ΔhrcU265–357 + hrcU265–357) and carrying either the empty vector (−) or HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (HpaCΔ2–111), as indicated, were inoculated at a bacterial density of 1 × 108 CFU/ml into leaves of susceptible ECW and resistant ECW-10R pepper plants, respectively. Disease symptoms were photographed at 8 dpi. For better visualization of the HR, leaves were bleached in ethanol at 2 dpi. Dashed lines mark the infiltrated areas.

To confirm this, we also analyzed the effect of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc on the pathogenicity of strain 85* ΔhrcU265–357, which lacks the cytoplasmic domain of HrcU (46). We have previously shown that the mutant phenotype of strain 85* ΔhrcU265–357 can be complemented partially by providing the C-terminal cleavage product of HrcU (HrcU265–357) in trans (46). HrcU265–357 lacks the NPTH motif and no longer interacts efficiently with HpaC (Fig. 7C) (46). GST pulldown assays revealed a similar result for HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (Fig. 7C). However, we observed that HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc led to a severe reduction of in planta symptom formation caused by strain 85* ΔhrcU265–357 carrying HrcU265–357-c-Myc (Fig. 7D). This finding confirms our notion that HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc not only interacts with HrcUC but also employs alternative mechanisms that are involved in the dominant-negative effect of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc on T3S.

A phenylalanine residue at position 175 of HpaC is required for protein function and the interaction with HrcUC.

To study the contribution of the C-terminal region of HpaC to the T3S substrate specificity switch in more detail, we introduced point mutations leading to exchange of the leucine residues at positions 164, 171, and 173 and the phenylalanine residue at position 175 with alanine. These amino acids are conserved in HpaC and HpaP (Fig. 1). HpaC point mutant derivatives were analyzed as c-Myc epitope-tagged proteins in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10 ΔhpaC and 85* ΔhpaC as described above. Infection assays revealed that HpaCL164A-c-Myc, HpaCL171A-c-Myc, and HpaCL173A-c-Myc complemented the in planta phenotypes of strains 85-10 ΔhpaC and 85* ΔhpaC. Partial complementation of disease symptoms was observed with HpaCF175A-c-Myc. Furthermore, HpaCF175A-c-Myc did not fully restore the HR induction by strain 85* ΔhpaC (Fig. 8 A). In contrast, the HR induction by strain 85-10 ΔhpaC carrying HpaCF175A-c-Myc was like that of the wild type (Fig. 8A). The phenotypic differences were not caused by differences in protein stability, because all HpaC mutant derivatives were stably synthesized, as shown by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 8B; data not shown).

Fig. 8.

The phenylalanine residue at position 175 of HpaC contributes to virulence, in vitro T3S, and the interaction between HpaC and HrcUC. (A) F175A exchange in HpaC leads to reduced virulence. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85-10 (wt), 85-10 ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC), 85* (wt), and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) carrying the empty vector (−) or encoding HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC), HpaCL164A-c-Myc (L164A), HpaCL171A-c-Myc (L171A), HpaCL173A-c-Myc (L173A), or HpaCF175A-c-Myc (F175A), as indicated, were inoculated at a density of 108 CFU/ml into leaves of susceptible ECW pepper plants. For the analysis of hrpG* derivatives in resistant ECW-10R pepper plants, the inoculation density was lowered to 2 × 107 CFU/ml. Disease symptoms were photographed at 5 dpi (for 85-10 derivatives) and at 6 dpi (for 85* derivatives). For better visualization of the HR, leaves were bleached in ethanol at 2 dpi. Dashed lines indicate the infiltrated areas. (B) F175 is required for the HpaC-mediated control of HrpF and HrpB2 secretion. X. campestris pv. vesicatoria strains 85* (wt) and 85* ΔhpaC (ΔhpaC) carrying the empty vector (−) or HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC), HpaCL164A-c-Myc (L164A), HpaCL171A-c-Myc (L171A), HpaCL173A-c-Myc (L173A), or HpaCF175A-c-Myc (F175A), as indicated, were incubated in secretion medium. Total cell extracts (TE) and culture supernatants (SN) were analyzed by immunoblotting using HrpF-, HrpB2-, and c-Myc epitope-specific antibodies. The upper signal detected by the HrpF-specific antibody corresponds to HrpF, and the lower signal corresponds to degradation products. (C) The F175A exchange in HpaC abolishes the stable interaction between HpaC and HrcUC. Immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc (HpaC), HpaCL164A-c-Myc (L164A), HpaCL171A-c-Myc (L171A), HpaCL173A-c-Myc (L173A), or HpaCF175A-c-Myc (F175A), as indicated. Total cell extracts (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using a c-Myc epitope-specific antibody. Blots were routinely incubated with a GST-specific antibody to ensure stable synthesis of GST and GST fusion proteins (data not shown).

In addition to infection studies, we performed T3S assays with strains 85* and 85* ΔhpaC carrying HpaC-c-Myc and mutant derivatives thereof. While L164A, L171A, and L173A mutations in HpaC did not affect the secretion of HrpF and HrpB2 by strain 85* ΔhpaC, HpaCF175A-c-Myc only partially restored wild-type levels of HrpF and HrpB2 secretion (Fig. 8B). The results of the T3S assays are in agreement with the observed phenotypic differences (Fig. 8A) and suggest that the phenylalanine residue at position 175 of HpaC is important for protein function. To investigate whether the F175A mutation in HpaC also affects the interaction with HrcUC, we performed GST pulldown assays with GST-HrcU255–357, HpaC-c-Myc, and point mutant derivatives thereof. Compared with HpaC-c-Myc, which coeluted with GST-HrcU255–357 but not with GST, reduced amounts of HpaCL164A-c-Myc, HpaCL171A-c-Myc, and HpaCL173A-c-Myc were detected in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357. This suggests that L164A, L171A, and L173A point mutations affect the interaction of HpaC with HrcUC (Fig. 8C). Notably, we did not detect HpaCF175A-c-Myc in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 (Fig. 8C). We therefore concluded that the phenylalanine residue at position 175 is important for both HpaC function and the interaction with HrcUC.

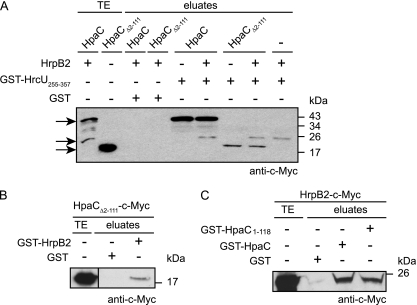

HpaC, HrcUC, and HrpB2 are part of a common protein complex.

Given that HpaC interacts with HrpB2 and HrcUC (48), we wondered whether these three proteins form a protein complex. We therefore immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 on glutathione Sepharose and incubated them with HpaC-c-Myc in the absence or presence of HrpB2-c-Myc. Figure 9 A shows that both HpaC-c-Myc and HrpB2-c-Myc were present in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 but not in that of GST, suggesting that all three proteins are part of the same complex. We repeated the interaction studies with HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc, which provides the binding site for HrcUC. Similar to HpaC-c-Myc, HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc coeluted with GST-HrcU255–357, irrespective of the presence of HrpB2-c-Myc. Furthermore, HrpB2-c-Myc was also detected in the eluate of GST-HrcU255–357 in the absence or presence of HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc (Fig. 9A). Since HrpB2 and HpaC both bind to the NPTH motif of HrcUC, they presumably compete for the same binding site, suggesting that HpaC acts as a linker between HrcUC and HrpB2 during complex formation (46). We therefore investigated whether HpaCΔ2–111, which interacts with HrcUC (Fig. 5C), also provides a binding site for HrpB2. For this purpose, we performed GST pulldown assays with GST-HrpB2 and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc. HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc was detected in the eluate of GST-HrpB2 but not in that of GST, suggesting that it interacts with HrpB2 (Fig. 9B). In a reciprocal experiment, we analyzed the interaction of HrpB2-c-Myc with immobilized GST-HpaC and GST-HpaC1-118. The latter lacks the C-terminal protein region. Interestingly, HrpB2-c-Myc was detected in the eluates of both GST-HpaC and GST-HpaC1-118 but not in that of GST (Fig. 9C). We concluded from these results that (i) the C-terminal region of HpaC is sufficient but not essential for the interaction with HrpB2 and (ii) HpaC contains more than one binding site for HrpB2.

Fig. 9.

The C-terminal region of HpaC is sufficient for complex formation with HrcUC and HrpB2. (A) The C-terminal region of HpaC forms a complex with HrcUC and HrpB2. Immobilized GST and GST-HrcU255–357 were incubated with HpaC-c-Myc, HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc, and/or HrpB2-c-Myc, as indicated. Total cell extracts (TE) and eluted proteins (eluates) were analyzed by immunoblotting using a c-Myc epitope-specific antibody. Arrows indicate the positions of HpaC-c-Myc, HrpB2-c-Myc, and HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc. (B) The C-terminal region of HpaC provides a binding site for HrpB2. Immobilized GST and GST-HrpB2 were incubated with HpaCΔ2–111-c-Myc, and total cell extracts and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A. (C) The C-terminal region of HpaC is dispensable for the interaction with HrpB2. Immobilized GST, GST-HpaC, and GST-HpaC1-118 were incubated with HrpB2-c-Myc, and total cell extracts and eluates were analyzed as described for panel A. Blots were routinely incubated with a GST-specific antibody to ensure stable synthesis of GST and GST fusion proteins (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

HpaC from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria is the first known T3S4 protein identified in plant-pathogenic bacteria. Similar to T3S4 proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria, HpaC switches the T3S substrate specificity from early (HrpB2) to late (translocon and effector proteins) substrates and contributes to bacterial pathogenicity. In this study, the analysis of serial HpaC deletion derivatives revealed that the N-terminal 41 and the C-terminal 111 amino acids of HpaC (total length of 212 amino acids) are essential for the contributions of HpaC to T3S and bacterial virulence. In contrast, an HpaC derivative lacking amino acids 42 to 101 was still functional, suggesting that the central region of HpaC encompassing amino acids 42 to 101 is dispensable for the contributions of HpaC to T3S and pathogenicity (Fig. 2 and 3). Notably, however, deletions in the central protein region impaired the ability of HpaC to restore wild-type levels of HrpB2 secretion, while secretion of HrpF was not affected or was affected only partially (Fig. 2 and 3). Of course, it cannot be excluded that differences in the abilities of HpaC deletion derivatives to complement the hpaC mutant phenotype were caused by differences in protein folding. However, our results clearly show that the HpaC-dependent secretion of early and late substrates might be controlled by distinct mechanisms that can be uncoupled. In agreement with this model, we previously found that HrcUY318D restored secretion of late substrates in an hpaC mutant strain but did not affect oversecretion of HrpB2 (46). This implies that the postulated conformational change in HrcUC that is mimicked by HrcUY318D is not sufficient for the control of HrpB2 secretion. The HpaC-mediated suppression of HrpB2 secretion therefore presumably depends on alternative mechanisms that remain to be elucidated. It is possible that the direct interaction of HpaC with HrpB2 leads to the suppression of HrpB2 secretion, because HpaC-bound HrpB2 is retained in the bacterial cytoplasm. Unfortunately, because HrpB2 appears to interact with both the N- and C-terminal regions of HpaC, it is technically difficult to elucidate the contribution of the HpaC-HrpB2 interaction to the control of HrpB2 secretion. Furthermore, given the fact that HpaC, HrcUC, and HrpB2 are part of the same protein complex (Fig. 9), it cannot be excluded that HpaC prevents the access of HrpB2 to HrcUC and thus to the secretion apparatus. Notably, we have previously shown that HpaC and HrpB2 both depend on the NPTH motif for efficient binding to HrcUC, suggesting that they compete for the same binding site.

Protein-protein interaction studies with HpaC deletion derivatives showed that the C-terminal region of HpaC spanning amino acids 112 to 212 is required and sufficient for the interaction with HrcUC. Since HpaC derivatives with deletions in this region did not complement the hpaC mutant phenotypes and did not detectably interact with HrcUC, we assume that the binding of HpaC to HrcUC is essential for the HpaC-dependent T3S substrate specificity switch. Notably, however, the HpaC-HrcUC interaction is presumably not sufficient to induce the substrate specificity switch, because deletions in the N-terminal region of HpaC led to a loss of protein function without affecting the binding of HpaC to HrcUC (Fig. 2 to 4). Furthermore, we showed that the C-terminal region of HpaC (HpaCΔ2–111), which provides the HrcUC-binding site, did not complement the hpaC mutant phenotypes. Interestingly, ectopic expression of HpaCΔ2–111 in the wild-type strain led to reduced secretion of early and late T3S substrates, suggesting that enhanced levels of HpaCΔ2–111 exert a dominant-negative effect on T3S (Fig. 6). It was tempting to speculate that binding of HpaCΔ2–111 to HrcUC blocks the conformation of HrcUC in a state that is not permissive for the secretion of late T3S substrates. Alternatively, HrcUC-bound HpaCΔ2–111 might prevent the access of T3S substrates such as HrpB2 to the secretion apparatus (46). Notably, however, the inhibitory effect of HpaCΔ2–111 did not appear to be restricted to the interaction with HrcUC, because it was also observed in hrcU mutant strains that did not allow an efficient HpaC-HrcUC interaction (Fig. 7). We therefore assume that the dominant-negative effect of HpaCΔ2–111 is also caused by distinct molecular mechanisms that remain to be investigated. It cannot be excluded that HpaCΔ2–111 titrates additional components (e.g., the ATPase HrcN and the inner membrane protein HrcV) or control proteins (e.g., the global chaperone HpaB and the secreted regulator HpaA) of the T3S system which have previously been shown to interact with HpaC and are required for efficient T3S (14, 45, 47). The binding sites of these proteins in HpaC have yet to be determined.

The localization of the HrcUC-binding site in the C-terminal region of HpaC is in agreement with the finding that the binding site of the FlhB/YscU homolog Spa40 from the animal-pathogenic bacterium S. flexneri was mapped to amino acids 206 to 246 of the T3S4 protein Spa32 (total length of 292 amino acids) and was shown to be crucial for Spa32 function (9). Similarly, essential protein regions and functional amino acid residues were identified in the C-terminal domain (T3S4 domain) of FliK from the flagellar T3S system (52). It was assumed that binding of FliK to FlhBC is structurally controlled by the N-terminal region of FliK and might therefore occur only upon secretion of FliK (56). This model was based on the finding that the T3S4 domain of FliK alone is unable to restore the fliK mutant phenotype (56).

According to the “molecular ruler” model proposed for T3S4 proteins from animal-pathogenic bacteria, the N-terminal region of T3S4 proteins enters the secretion apparatus. A pause in secretion and/or a stretched conformation of the T3S4 protein presumably allows the interaction of the C-terminal domain with the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of FlhB/YscU family members and thus signals the substrate specificity switch (19, 25, 72, 73). It is unlikely, however, that the molecular ruler model is applicable to plant-pathogenic bacteria, because the extracellular pilus that is associated with the T3S systems of plant-pathogenic bacteria is too long to be “bridged” by a single proteinaceous ruler. In good agreement with this hypothesis is our finding that HpaC from X. campestris pv. vesicatoria is not secreted by the T3S system and therefore probably acts as a switch protein without a ruler function (14). Furthermore, we demonstrated that deletion of the central region of HpaC (amino acids 42 to 101) did not interfere significantly with protein function, suggesting that a defined length of HpaC is not essential for the substrate specificity switch (Fig. 2 and 3). We therefore propose that HpaC acts as a cytoplasmic T3S4 protein that binds to HrcUC prior to the proteolytic cleavage of HrcU at the conserved NPTH motif (46). Because HpaC also interacts with HrpB2, which might compete with HpaC for the same binding site in HrcUC, it is conceivable that HpaC blocks the access of HrpB2 to the secretion apparatus at the inner bacterial membrane. The interaction between HpaC and HrcUC is presumably required to induce the T3S substrate specificity switch that promotes the secretion of translocon and effector proteins and abolishes the efficient secretion of HrpB2 (46, 48). In this study, however, we provide experimental evidence that the binding of HpaC to HrcUC, which depends on the C-terminal region of HpaC, is required but not sufficient for the control of T3S. It remains to be investigated whether the N-terminal region of HpaC is needed to induce the predicted conformational change in HrcUC and thus the switch in T3S substrate specificity.

Taken together, the observations in this study provide the first detailed characterization of a T3S4 protein from a plant-pathogenic bacterium and suggest that in contrast to the proposed substrate specificity switch mechanisms in animal-pathogenic bacteria, secretion of early and late T3S substrates in X. campestris pv. vesicatoria is controlled by distinct HpaC-dependent mechanisms that can be uncoupled. Furthermore, our data imply that the interaction between HpaC and HrcUC is not sufficient to trigger the T3S substrate specificity switch. Open questions for future research concern the contribution of the N-terminal region of HpaC to the switch or to the interaction of HpaC with additional binding partners that have been identified previously, including T3S substrates and conserved components of the secretion apparatus (14, 45). The relevance of these interactions to the role of HpaC as a T3S4 protein remains to be investigated.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to M. Jordan for technical assistance, to U. Bonas for critical reading of the manuscript, and to A. Eichhorn for generating constructs pBRMhpaCΔ62-91 and pBRMhpaCΔ42-101.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BU 2145/1-1) and the Sonderforschungsbereich SFB 648 Molekulare Mechanismen der Informationsverarbeitung in Pflanzen to D.B.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agrain C., et al. 2005. Characterization of a type III secretion substrate specificity switch (T3S4) domain in YscP from Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 56:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akeda Y., Galan J. E. 2005. Chaperone release and unfolding of substrates in type III secretion. Nature 437:911–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold R., et al. 2009. Sequence-based prediction of type III secreted proteins. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ausubel F. M., et al. (ed.). 1996. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartetzko V., et al. 2009. The Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria type III effector protein XopJ inhibits protein secretion: evidence for interference with cell wall-associated defense responses. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 22:655–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Björnfot A. C., Lavander M., Forsberg A., Wolf-Watz H. 2009. Auto-proteolysis of YscU of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is important for regulation of expression and secretion of Yop proteins. J. Bacteriol. 191:4259–4267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolchi A., Ottonello S., Petrucco S. 2005. A general one-step method for the cloning of PCR products. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 42:205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonas U., et al. 1991. Isolation of a gene-cluster from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria that determines pathogenicity and the hypersensitive response on pepper and tomato. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 4:81–88 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Botteaux A., Sani M., Kayath C. A., Boekema E. J., Allaoui A. 2008. Spa32 interaction with the inner-membrane Spa40 component of the type III secretion system of Shigella flexneri is required for the control of the needle length by a molecular tape measure mechanism. Mol. Microbiol. 70:1515–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Büttner D., Bonas U. 2002. Getting across—bacterial type III effector proteins on their way to the plant cell. EMBO J. 21:5313–5322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Büttner D., Bonas U. 2002. Port of entry—the type III secretion translocon. Trends Microbiol. 10:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Büttner D., Bonas U. 2010. Regulation and secretion of Xanthomonas virulence factors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:107–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Büttner D., Gürlebeck D., Noël L. D., Bonas U. 2004. HpaB from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria acts as an exit control protein in type III-dependent protein secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 54:755–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Büttner D., Lorenz C., Weber E., Bonas U. 2006. Targeting of two effector protein classes to the type III secretion system by a HpaC- and HpaB-dependent protein complex from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Microbiol. 59:513–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Büttner D., Nennstiel D., Klüsener B., Bonas U. 2002. Functional analysis of HrpF, a putative type III translocon protein from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 184:2389–2398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Büttner D., Noël L., Stuttmann J., Bonas U. 2007. Characterization of the non-conserved hpaB-hrpF region in the hrp pathogenicity island from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 20:1063–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Canteros B. I. 1990. Diversity of plasmids and plasmid-encoded phenotypic traits in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Ph.D. thesis. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coombes B. K., Finlay B. B. 2005. Insertion of the bacterial type III translocon: not your average needle stick. Trends Microbiol. 13:92–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cornelis G. R., Agrain C., Sorg I. 2006. Length control of extended protein structures in bacteria and bacteriophages. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daniels M. J., et al. 1984. Cloning of genes involved in pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris using the broad host range cosmid pLAFR1. EMBO J. 3:3323–3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deane J. E., et al. 2008. Crystal structure of Spa40, the specificity switch for the Shigella flexneri type III secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 69:267–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Desvaux M., Hebraud M., Henderson I. R., Pallen M. J. 2006. Type III secretion: what's in a name? Trends Microbiol. 14:157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edqvist P. J., et al. 2003. YscP and YscU regulate substrate specificity of the Yersinia type III secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 185:2259–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Engler C., Kandzia R., Marillonnet S. 2008. A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS One 3:e3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Erhardt M., et al. 2010. The role of the FliK molecular ruler in hook-length control in Salmonella enterica. Mol. Microbiol. 75:1272–1284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Escolar L., Van den Ackerveken G., Pieplow S., Rossier O., Bonas U. 2001. Type III secretion and in planta recognition of the Xanthomonas avirulence proteins AvrBs1 and AvrBsT. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2:287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feldman M. F., Cornelis G. R. 2003. The multitalented type III chaperones: all you can do with 15 kDa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219:151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferris H. U., et al. 2005. FlhB regulates ordered export of flagellar components via autocleavage mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 280:41236–41242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Figurski D., Helinski D. R. 1979. Replication of an origin-containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:1648–1652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gauthier A., Finlay B. B. 2003. Translocated intimin receptor and its chaperone interact with ATPase of the type III secretion apparatus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 185:6747–6755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ghosh P. 2004. Process of protein transport by the type III secretion system. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:771–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. He S. Y., Nomura K., Whittam T. S. 2004. Type III protein secretion mechanism in mammalian and plant pathogens. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694:181–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huguet E., Hahn K., Wengelnik K., Bonas U. 1998. hpaA mutants of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria are affected in pathogenicity but retain the ability to induce host-specific hypersensitive reaction. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1379–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jones J. D., Dangl J. L. 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444:323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Journet L., Agrain C., Broz P., Cornelis G. R. 2003. The needle length of bacterial injectisomes is determined by a molecular ruler. Science 302:1757–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kay S., Hahn S., Marois E., Hause G., Bonas U. 2007. A bacterial effector acts as a plant transcription factor and induces a cell size regulator. Science 318:648–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knoop V., Staskawicz B., Bonas U. 1991. Expression of the avirulence gene avrBs3 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is not under the control of hrp genes and is independent of plant factors. J. Bacteriol. 173:7142–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koebnik R. 2001. The role of bacterial pili in protein and DNA translocation. Trends Microbiol. 9:586–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kousik C. S., Ritchie D. F. 1998. Response of bell pepper cultivars to bacterial spot pathogen races that individually overcome major resistance genes. Plant Dis. 82:181–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kovach M. E., et al. 1995. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene 166:175–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kutsukake K., Minamino T., Yokoseki T. 1994. Isolation and characterization of FliK-independent flagellation mutants from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:7625–7629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lavander M., et al. 2002. Proteolytic cleavage of the FlhB homologue YscU of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is essential for bacterial survival but not for type III secretion. J. Bacteriol. 184:4500–4509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leyns F., De Cleene M., Swings J., De Ley J. 1984. The host range of the genus Xanthomonas. Bot. Rev. 50:305–355 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lloyd S. A., Sjostrom M., Andersson S., Wolf-Watz H. 2002. Molecular characterization of type III secretion signals via analysis of synthetic N-terminal amino acid sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 43:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lorenz C., Büttner D. 2009. Functional characterization of the type III secretion ATPase HrcN from the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 191:1414–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lorenz C., Büttner D. 2011. Secretion of early and late substrates of the type III secretion system from Xanthomonas is controlled by HpaC and the C-terminal domain of HrcU. Mol. Microbiol. 79:447–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lorenz C., et al. 2008. HpaA from Xanthomonas is a regulator of type III secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 69:344–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lorenz C., et al. 2008. HpaC controls substrate specificity of the Xanthomonas type III secretion system. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lountos G. T., Austin B. P., Nallamsetty S., Waugh D. S. 2009. Atomic resolution structure of the cytoplasmic domain of Yersinia pestis YscU, a regulatory switch involved in type III secretion. Protein Sci. 18:467–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Magdalena J., et al. 2002. Spa32 regulates a switch in substrate specificity of the type III secreton of Shigella flexneri from needle components to Ipa proteins. J. Bacteriol. 184:3433–3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ménard R., Sansonetti P. J., Parsot C. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899–5906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Minamino T., Ferris H. U., Moriya N., Kihara M., Namba K. 2006. Two parts of the T3S4 domain of the hook-length control protein FliK are essential for the substrate specificity switching of the flagellar type III export apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 362:1148–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Minamino T., Gonzalez-Pedrajo B., Yamaguchi K., Aizawa S. I., Macnab R. M. 1999. FliK, the protein responsible for flagellar hook length control in Salmonella, is exported during hook assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 34:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Minamino T., Macnab R. M. 2000. Domain structure of Salmonella FlhB, a flagellar export component responsible for substrate specificity switching. J. Bacteriol. 182:4906–4914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Minamino T., MacNab R. M. 2000. Interactions among components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and its substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1052–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Minamino T., et al. 2004. Domain organization and function of Salmonella FliK, a flagellar hook-length control protein. J. Mol. Biol. 341:491–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Minsavage G. V., et al. 1990. Gene-for-gene relationships specifying disease resistance in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria-pepper interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 3:41–47 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parsot C., Hamiaux C., Page A. L. 2003. The various and varying roles of specific chaperones in type III secretion systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Petnicki-Ocwieja T., et al. 2002. Genomewide identification of proteins secreted by the Hrp type III protein secretion system of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7652–7657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pieretti I., et al. 2009. The complete genome sequence of Xanthomonas albilineans provides new insights into the reductive genome evolution of the xylem-limited Xanthomonadaceae. BMC Genomics 10:616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ronald P. C., Staskawicz B. J. 1988. The avirulence gene avrBs1 from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria encodes a 50-kDa protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1:191–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rossier O., Van den Ackerveken G., Bonas U. 2000. HrpB2 and HrpF from Xanthomonas are type III-secreted proteins and essential for pathogenicity and recognition by the host plant. Mol. Microbiol. 38:828–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rossier O., Wengelnik K., Hahn K., Bonas U. 1999. The Xanthomonas Hrp type III system secretes proteins from plant and mammalian pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9368–9373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Samudrala R., Heffron F., McDermott J. E. 2009. Accurate prediction of secreted substrates and identification of a conserved putative secretion signal for type III secretion systems. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Schechter L. M., Roberts K. A., Jamir Y., Alfano J. R., Collmer A. 2004. Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system targeting signals and novel effectors studied with a Cya translocation reporter. J. Bacteriol. 186:543–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sorg I., et al. 2007. YscU recognizes translocators as export substrates of the Yersinia injectisome. EMBO J. 26:3015–3024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Staskawicz B. J., Dahlbeck D., Keen N., Napoli C. 1987. Molecular characterization of cloned avirulence genes from race0 and race1 of Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. J. Bacteriol. 169:5789–5794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Szczesny R., et al. 2010. Functional characterization of the Xps and Xcs type II secretion systems from the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. New Phytol. 187:983–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Thieme F., et al. 2005. Insights into genome plasticity and pathogenicity of the plant pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria revealed by the complete genome sequence. J. Bacteriol. 187:7254–7266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thomas J., Stafford G. P., Hughes C. 2004. Docking of cytosolic chaperone-substrate complexes at the membrane ATPase during flagellar type III protein export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:3945–3950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vieira J., Messing J. 1987. Production of single-stranded plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 153:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wagner S., Stenta M., Metzger L. C., Dal Peraro M., Cornelis G. R. 2010. Length control of the injectisome needle requires only one molecule of Yop secretion protein P (YscP). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:13860–13865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Waters R. C., O'Toole P. W., Ryan K. A. 2007. The FliK protein and flagellar hook-length control. Protein Sci. 16:769–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Weber E., Berger C., Bonas U., Koebnik R. 2007. Refinement of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria hrpD and hrpE operon structure. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20:559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Weber E., et al. 2005. The type III-dependent Hrp pilus is required for productive interaction of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria with pepper host plants. J. Bacteriol. 187:2458–2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wengelnik K., Bonas U. 1996. HrpXv, an AraC-type regulator, activates expression of five of the six loci in the hrp cluster of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. J. Bacteriol. 178:3462–3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wengelnik K., Rossier O., Bonas U. 1999. Mutations in the regulatory gene hrpG of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria result in constitutive expression of all hrp genes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6828–6831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wengelnik K., Van den Ackerveken G., Bonas U. 1996. HrpG, a key hrp regulatory protein of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is homologous to two-component response regulators. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 9:704–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wiesand U., et al. 2009. Structure of the type III secretion recognition protein YscU from Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Mol. Biol. 385:854–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Williams A. W., et al. 1996. Mutations in fliK and flhB affecting flagellar hook and filament assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:2960–2970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zarivach R., et al. 2008. Structural analysis of the essential self-cleaving type III secretion proteins EscU and SpaS. Nature 453:124–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.