Abstract

Peroxisomal matrix protein import is facilitated by cycling receptors shuttling between the cytosol and the peroxisomal membrane. One crucial step in this cycle is the ATP-dependent release of the receptors from the peroxisomal membrane. This step is facilitated by the peroxisomal AAA (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) proteins Pex1p and Pex6p with ubiquitination of the receptor being the main signal for its export. Here we report that the AAA complex contains dislocase as well as deubiquitinating activity. Ubp15p, a ubiquitin hydrolase, was identified as a novel constituent of the complex. Ubp15p partially localizes to peroxisomes and is capable of cleaving off ubiquitin moieties from the type I peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1) receptor Pex5p. Furthermore, Ubp15p-deficient cells are characterized by a stress-related PTS1 import defect. The results merge into a picture in which removal of ubiquitin from the PTS1 receptor Pex5p is a specific event and might represent a vital step in receptor recycling.

Keywords: Deubiquitination, Peroxisomes, Protein Targeting, Protein Translocation, Yeast, PTS1 Receptor, Peroxins

Introduction

Peroxisomes are organelles that carry out a wide variety of metabolic processes in eukaryotic organisms. As peroxisomes do not contain genetic material, their protein content is determined by the import of nuclearly encoded proteins. Peroxisomes can multiply by division (1) or de novo by budding from the endoplasmic reticulum (2, 3). Without exception, peroxisomal matrix proteins are synthesized on free ribosomes and are subsequently imported in a post-translational manner (4, 5). Like the sorting of proteins to other cellular compartments, protein targeting to peroxisomes depends on signal sequences. Peroxisomal matrix proteins contain a C-terminal type I peroxisomal targeting sequence (PTS1)5 or an N-terminal PTS2 (4). These PTSs are recognized by conserved receptors, Pex5p and Pex7p, respectively. Based on the concept of cycling receptors (6, 7), matrix protein import can be divided into four steps: 1) receptor-cargo recognition in the cytosol, 2) docking at the peroxisomal membrane, 3) cargo translocation and release, and 4) receptor release from the membrane and recycling.

With respect to the PTS1 receptor Pex5p, recent reports demonstrated that its dislocation from the peroxisomal membrane to the cytosol at the end of the receptor cycle is ATP-dependent and catalyzed by the AAA peroxins Pex1p and Pex6p (8, 9). The main signal for the export process is the attachment of a monoubiquitin moiety or, alternatively, the anchoring of a polyubiquitin chain (10, 11). Although receptor monoubiquitination occurs on a conserved cysteine, polyubiquitin chains are attached to two lysine residues (10, 12). In general, conjugation of ubiquitin to a target protein or to itself is regulated by the sequential activity of ubiquitin-activating (E1), ubiquitin-conjugating (E2), and ubiquitin-ligating (E3) enzymes, and it typically results in the addition of a ubiquitin moiety either to the ϵ-amino group of a Lys residue or to the extreme N terminus of a polypeptide (13). In a very few cases, including Pex5p, attachment to a Cys residue also has been reported (12, 14). Whereas the addition of a single ubiquitin to a target protein can alter protein activity and localization, the formation of a diverse array of ubiquitin chains is implicated in targeting to the 26 S proteasome (15).

In line with these findings, polyubiquitination of Pex5p makes the receptor available for proteasomal degradation as part of a quality control system for the disposal of dysfunctional Pex5p (16–18). Modification of Pex5p by a single ubiquitin on a conserved Cys residue provides the signal for the AAA peroxin-mediated release of the receptor from the peroxisomal membrane (10, 11, 19). This is of special importance as this ATP-dependent dislocation of the receptor is supposed to be responsible for the overall energy requirement of the protein import cascade and thus might be mechanistically linked to cargo translocation as proposed by the export-driven import model (20).

The ubiquitination cascade acting on Pex5p has been elucidated with the identification of Pex4p and the Ubc1p/Ubc4p/Ubc5p family as the responsible E2s (10, 12, 17, 18, 21). The peroxisomal RING finger peroxins Pex2p, Pex10p, and Pex12p have been identified as E3 enzymes responsible for the poly- and monoubiquitination of Pex5p (22, 23).

After export of the functional receptor to the cytosol, the ubiquitin moiety has to be removed. This cleavage of ubiquitin from a substrate protein is generally carried out by ubiquitin hydrolases also known as deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) (24). Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains genes coding for 18 DUBs (25, 26). Recent in vitro data obtained from rat indicated that the monoubiquitin (monoUb) moiety of Pex5p might be cleaved off in two different ways. A minor portion of the thioester-bound monoUb could be released in a non-enzymatic manner by a nucleophilic attack by glutathione, whereas the major fraction of monoUb-Pex5p is deubiquitinated enzymatically by a still to be identified ubiquitin hydrolase (27).

Here we report on the correlation of the ATP-dependent export of Pex5p and ubiquitin cleavage. The AAA complex of the peroxisomal protein import machinery turned out to possess export as well as deubiquitinating activity. Ubp15p was identified as a novel constituent of the complex that binds to the first AAA domain of Pex6p (D1 domain). Ubp15p exhibits ubiquitin hydrolase activity and is capable of cleaving off ubiquitin moieties from the PTS1 receptor Pex5p. The function of Ubp15p in peroxisome biogenesis is supported by a stress-related PTS1 import defect of ubp15Δ cells. A scenario evolves in which receptor deubiquitination might be functionally linked to its AAA peroxin-mediated export and represents an important step in the receptor cycle that makes Pex5p available for a new round of matrix protein import.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Culture Conditions

The S. cerevisiae strain UTL-7A (MATa ura3-52, trp1, leu2-3/112) was used as wild-type strain for the generation of several isogenic deletion strains by the “short flanking homology” method as described previously (28). The resulting deletion strains were pex5Δ (29), ubp14Δ, ubp15Δ, ubp14Δ/ubp15Δ, doa4Δ, and doa4Δ/ubp15Δ (this study). cl3-ABYS-86 (30) served as the wild-type strain for isolation of His6-Pex6p and His6-GST-Ubp15p complex. The yeast reporter strain L40 (MATa trp1 leu2 his3 LYS2::lexA-HIS3, URA3::lexA-lacZ) (31) was used for two-hybrid assays. Yeast media have been described previously (32). Inhibition of proteasomal degradation by the addition of MG132 to liquid cultures was performed according to Liu et al. (33).

Plasmids and Cloning Strategies

Sequences of oligonucleotides are available upon request. Two-hybrid plasmids expressing Gal4p fusions with Pex1p, Pex6p, or variants thereof were described previously (34). For expression of His6-Ubp15p in bakers' yeast, two overlapping PCRs were performed using genomic S. cerevisiae DNA as template. PCRI (primers RE1813/RE1749) amplified the 5′-half of UBP15 (NTP-UBP15), introducing an NcoI site to the 5′-end. PCRII (primers RE1746/RE1730) amplified the 3′-half of UBP15 (CTP-UBP15), introducing an XhoI site to the 3′-end. Both PCR products were subcloned into EcoRV-digested vector pGEM®-T (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), resulting in vectors pGEM-T-NTP-UBP15 and pGEM-T-CTP-UBP15, respectively. Next, the introduced fragments were cut out of the pGEM vectors (pGEM-T-NTP-UBP15, NcoI/BamHI; pGEM-T-CTP-UBP15, BamHI/XhoI) and cloned together into NcoI/XhoI sites of pYES263 (35), leading to pYES263-UBP15.

For the expression of GST fusions of Ubp15p in Escherichia coli, the vector pGEX-4T-2 (GE Healthcare) was digested with BamHI followed by a Klenow refill reaction and the subsequent cleavage with XhoI. The Ubp15p coding region was obtained by cleaving pYES263-UBP15 with NcoI, Klenow-based refilling, and subsequent XhoI treatment. The UBP15 fragment was then cloned into equally treated pGEX-4T-2, resulting in pGEX-4T-2-UBP15. To introduce a C214A amino acid residue substitution into Ubp15p, the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used combined with pGEX-4T2-UBP15 as template and primers RE2274/RE2275 for the reaction. GFP-Ubp15p expression plasmid pUG36-UBP15 was constructed as follows. UBP15 was amplified by PCR using primers RE3196/RE3198 and plasmid pYES263-UBP15 as template. The SpeI/SalI-digested PCR product was cloned into the SpeI/SalI site of pUG36 (36).

To obtain N-terminal His6-TEV-tagged Pex6p under the control of the GAL1 promotor for expression in yeast, the coding region for the N-terminal half of Pex6p was amplified by PCR using primers KU1549/KU1550 and plasmid pMB34 (37) as template. In a second step, PEX6 was amplified by PCR (primers KU1339/KU698 and plasmid pMB34) and cloned into the NcoI/SpeI site of pYES2.1V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen), leading to vector pYQ6/1. Finally, the first PCR (N-terminal half of Pex6p) was digested with PvuII/SacI, and the fragment was introduced into the PvuII/SacI-digested vector pYQ6/1, leading to pJK-5. Plasmids for expression of PTS2-dsRed or high expression of Pex15p were described elsewhere (38, 39).

Two-hybrid Assay

The yeast reporter strain L40 was transformed with two-hybrid plasmids pPC86 and pPC97 (40) or derivatives thereof and grown on synthetic medium lacking tryptophan and leucine for 3 days at 30 °C. The obtained double transformants were grown at 30 °C for 8 h in liquid synthetic medium. Lysates from these cells were prepared and subsequently subjected to β-galactosidase assays as described (41).

Purification of Pex6p from S. cerevisiae Cells

Recombinant His-tagged Pex6p or Ubp15p were expressed in S. cerevisiae strain cl3-ABYS-86 (30) transformed with pJK-5 or pYES263-UBP15, respectively. Galactose-grown cells were harvested, resuspended in lysis buffer (1.7 mm KH2PO4, 5.2 mm Na2HPO4, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 22.5 μg/ml DNase I) with protease inhibitor mixture (8 μm antipain, 0.3 μm aprotinin, 1 μm bestatin, 10 μm chymostatin, 5 μm leupeptin, 1.5 μm pepstatin (Roche Diagnostics), 1 mm benzamidine, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 5 mm NaF). Cells were disrupted by glass bead lysis. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation and 0.22-μm filtration and loaded on nickel-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) columns equilibrated with washing buffer (1.7 mm KH2PO4, 5.2 mm Na2HPO4, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 40 mm imidazole). The column was washed until no more protein eluted. Pex6p was then eluted by a continuous imidazole gradient up to 500 mm imidazole in elution buffer (1.7 mm KH2PO4, 5.2 mm Na2HPO4, 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 500 mm imidazole). Fractions containing a high concentration of protein were combined and concentrated by VivaSpin concentrators (10,000 molecular weight cutoff) (Sigma).

Isolation of Peroxisomes

Preparation of yeast spheroplasts, cell homogenization, preparation of postnuclear supernatants, and determination of the suborganellar localization of proteins were performed according to Erdmann et al. (42). Density gradient centrifugation was essentially performed as described (43); in particular, postnuclear supernatants (10 mg of protein) were prepared and loaded onto preformed 2.25–24% (w/v) OptiPrep (iodixanol) gradients. Peroxisomes were separated from other organelles in a vertical rotor (Sorvall TV 860, 1.5 h at 48,000 × g, 4 °C). Fractions were collected from the bottom and subjected to enzyme and refractive index measurements as well as immunoblot analysis.

Gel Filtration of Cell Lysates and Purified Proteins

Analytical gel filtration was carried out on a SMART System (Amersham Biosciences) equipped with a Superose 6 PC 3.2/30 column in running buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm ATP). Samples were cleared by centrifugation (15 min at 20,000 × g), and aliquots of 50 μl of purified protein were separated at 40 μl/min. Fractions of 80 μl were collected from 0.8 to 1.6 ml after injection. The column was calibrated using ferritin (440 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), and BSA (66 kDa) as markers.

In Vivo Ubiquitination Assays

Oleate-induced yeast cells were harvested, washed twice, and resuspended in lysis buffer (0.2 m HEPES, 1 m potassium acetate, 50 mm magnesium acetate, pH 7.5) and protease inhibitor mixture (see above)). To accumulate monoubiquitinated Pex5p from wild-type cells, 20 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (Sigma) was added. Cells were disrupted by glass bead lysis and centrifuged at 1,500 × g (Eppendorf rotor A-4-81) for 10 min. Supernatants were normalized for protein and volume, and membranes were sedimented by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min (Sorvall AH650 rotor) followed by trichloroacetic acid precipitation and sample preparation (18).

Deubiquitination Assay

Deubiquitinating activity of Ubp15p was analyzed according to Messick et al. (44). In detail, 1 μg of Ubp15p/Ubp15pC214A and 250 ng of appropriate polyUb(Lys-63) chains (Biomol, Lörrach, Germany) were diluted in reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mm NaCl) to a total volume of 30 μl. Reactions were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Before and after the reaction, 15 μl of each sample were charged with 3× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min for further analysis. Five microliters of each reaction were loaded onto a 15% Tris-glycine gel and subsequently subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

Proteins in polyacrylamide gels were visualized by Coomassie staining according to Neuhoff et al. (45). Destaining of proteins, in-gel tryptic digestion, and subsequent peptide extraction were performed as described (46). Peptide samples were separated by on-line reversed-phase nano-HPLC using the Dionex LC Packings HPLC systems (Dionex LC Packings, Idstein, Germany). Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry on a Bruker Daltonics HCTplus ion trap instrument (Bremen, Germany) and subsequent protein identification by bioinformatics using the yeast NCBI Database was performed as described (46).

Miscellaneous Methods

Immunopurification of ProtA-tagged Pex1p-Pex6p complexes from yeast cells using IgG-Sepharose was described (47). Immunoprecipitation of denatured proteins was carried out according to Platta et al. (22). Membranes containing monoubiquitinated Pex5p were prepared according to Platta et al. (22) and incubated with purified yeast AAA complex according to Platta et al. (8). Recombinant GST fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) according to the manufacturer's protocols (GE Healthcare). Immunoreactive complexes were visualized using anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG-coupled horseradish peroxidase in combination with the ECLTM system from Amersham Biosciences. Alternatively, primary antibody was detected with an IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences, Bad Homburg, Germany) followed by detection using an infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences). Polyclonal rabbit antibodies were raised against Pex5p (48), Pex13p (29), and ubiquitin (Sigma). Monoclonal mouse antibodies were raised against GST (Sigma) and ubiquitin (clone FK2, Biomol, Hamburg, Germany). GFP- and dsRed-tagged proteins were monitored by live cell imaging with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescence microscope and AxioVision 4.8 software (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Electron transmission microscopy, spheroplasting of yeast cells, homogenization, and differential centrifugation of homogenates at 25,000 × g were performed as described previously (8, 42, 49).

RESULTS

Peroxisomal AAA Complex Exhibits Deubiquitinating Activity

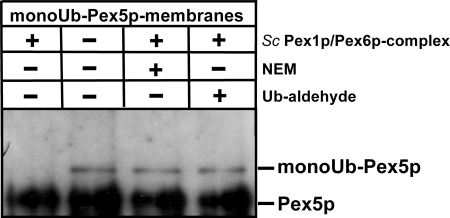

Dislocation of the PTS1 receptor Pex5p from the peroxisomal membrane to the cytosol depends on the peroxisomal AAA proteins Pex1p and Pex6p (8, 9), and ubiquitination of Pex5p is a prerequisite for this process (10). The main signal for the export process is the attachment of a monoubiquitin moiety (10, 11). To gain more insight into the principal export mechanism of monoubiquitinated Pex5p, membranes were prepared from wild-type cells in the presence of NEM, which is a suitable inhibitor of DUBs (50) and results in the accumulation of monoubiquitinated Pex5p at the peroxisomal membrane (10, 21). As NEM proved to be a competent inhibitor of the export machinery, membranes were washed extensively, and NEM was avoided upon purification of the AAA complexes. The membranes containing monoubiquitinated Pex5p were incubated with buffer alone or buffer containing purified cytosolic AAA complex of S. cerevisiae in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system (8) for 30 min at 37 °C. Interestingly, the presence of the AAA complex did result in the disappearance of the monoUb-Pex5p (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that the peroxisomal AAA complex does not only harbor the known dislocase activity of Pex1p/Pex6p but is also capable of facilitating receptor deubiquitination. This assumption is supported by the result that incubation of the AAA complex with DUB inhibitors NEM (Fig. 1, lane 3) and ubiquitin-aldehyde (Fig. 1, lane 4) prior to the assay blocks Pex5p deubiquitination.

FIGURE 1.

Yeast AAA complex possesses ubiquitin hydrolase activity. MonoUb-Pex5p-containing wild-type membranes were incubated with the AAA complex purified from a cytosolic fraction of pex5Δ cells using the TEV-ProtA tag. Where indicated, the AAA complex was preincubated with NEM or with Ub-aldehyde to inhibit the observed ubiquitin hydrolase activity. Sc, S. cerevisiae.

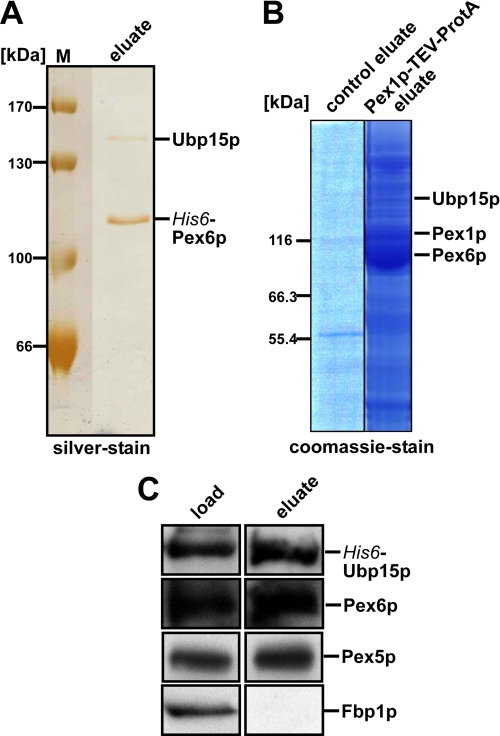

Ubp15p Is Associated with AAA Complex

The data described above also indicate that the isolated AAA complex contains export and deubiquitinating activity in the absence of cytosol. Thus, the suspected additional factor is supposed to be part of the yeast AAA complex. To identify the unknown factor, we isolated the cytosolic AAA complex with Pex6p as the overexpressed bait protein. For this purpose, a plasmid encoding N-terminal His6-tagged Pex6p under the inducible GAL1 promotor was transformed into the protease-deficient yeast strain cl3-ABYS-86 (30). Transformants were precultured on glucose-rich media, and expression of the tagged Pex6p was induced by shifting to galactose media. His-Pex6p was isolated by affinity chromatography on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining. Two dominant protein bands were visible (Fig. 2A) that were excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry. The fast migrating protein was identified as the bait protein Pex6p. The band with an approximate size of 140 kDa consisted of three proteins, Clu1p, Ubp15p, and Ecm21p. Clu1p is a subunit of translation initiation factor eIF3, which functions in AUG scanning in translation, that is also required to maintain the morphology of mitochondria (51, 52). Ubp15p is a ubiquitin-specific processing protease (53). Ecm21p is an arrestin-related protein that acts as an adaptor in ubiquitin ligation (54). As a second approach to identify AAA peroxin-associated proteins, we genomically tagged Pex1p with protein A, isolated the complex as described previously (8), separated proteins of the isolated complex by SDS-PAGE, and subjected selected protein bands to mass spectrometric analysis. The band marked in Fig. 2B contained Ubp15p, which indicated its association with the AAA complex and moved the protein into the focus of our interest. To validate the Pex6p-Ubp15p interaction, the complex isolation was performed vice versa using Ubp15p as bait. His6-GST-tagged Ubp15p was expressed in the wild-type cl3-ABYS-86 strain and isolated by immunopurification, and the constituents of the complex were analyzed by immunoblotting. Pex6p was identified as a component of the Ubp15p complex (Fig. 2C), and a minor portion of the PTS1 receptor Pex5p also co-eluted with the Ubp15p complex. The soluble fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (Fbp1p; Ref. 55) was not retained by the chromatography, an indication for the specificity of the isolation procedure (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Ubp15p forms a complex with AAA peroxins. Protein complexes were isolated by affinity chromatography from soluble fractions of the protease-deficient yeast strain cl3-ABYS-86 with His6-Pex6p (A) or from the UTL-7A strain with endogenously encoded Pex1p fused to TEV-ProtA tag (B). For the latter, the untransformed strain served as a control for the specificity of the isolation. Isolated proteins were visualized by silver stain or colloidal Coomassie as indicated. C, His6-GST-Ubp15p was isolated from the soluble fraction of the cl3-ABYS-86 strain and analyzed by immunoblotting. Equal volumes of load and the 100×-concentrated eluate fractions were probed with antibodies raised against the indicated proteins. The detection of cytosolic fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (Fbp1p) served as a control for unspecific binding. M, molecular mass markers.

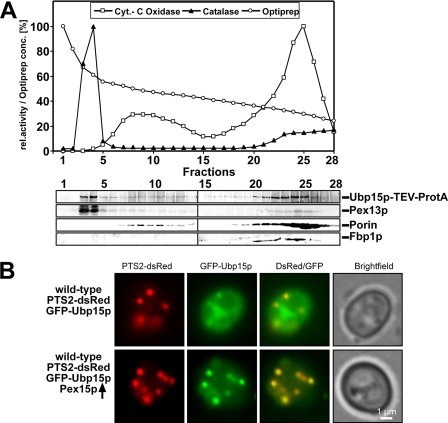

Portion of Ubiquitin Hydrolase Ubp15p Localizes to Peroxisomes

Our results demonstrate that yeast Ubp15p possesses the ability to interact with Pex6p. As Pex6p is localized in the cytosol and at peroxisomes, the subcellular localization of Ubp15p was analyzed under peroxisome-inducing conditions. To this end, a cell-free homogenate of oleic acid-induced wild-type cells expressing a genomically tagged UBP15 gene coding for a Ubp15p-protein A fusion protein (Ubp15p-TEV-ProtA) was prepared, and organelles were separated by density gradient centrifugation (Fig. 3A). The presence of organelle marker proteins in the obtained fractions was assayed either by determination of enzyme activities or by immunoblotting. As indicated by the segregation behavior of the peroxisomal membrane marker Pex13p and activity measurements of the peroxisomal catalase, peroxisomes migrated to the bottom fractions and showed a clear peak in fraction 3, clearly separated from the mitochondrial marker (porin). In line with the reported cytosolic localization (56), the majority of Ubp15p remained in the top gradient fractions. However, a significant portion of Ubp15p was detected at a higher density, co-localizing with peroxisomal marker proteins (Fig. 3A, lane 3). To support this finding, we monitored localization of GFP-tagged Ubp15p by fluorescence microscopy. GFP-Ubp15p was co-expressed with the synthetic peroxisomal marker protein PTS2-dsRed in wild-type cells. PTS2-dsRed exhibits a punctate fluorescence pattern, which is typical for a peroxisomal localization (Fig. 3B and Ref. 38). In line with our results obtained by cell fractionation (Fig. 3A), GFP-Ubp15p was predominantly localized to the cytosol, which leads to overall cellular fluorescence (Fig. 3B). However, a portion of GFP-Ubp15p co-stained with PTS2-dsRed-positive structures, demonstrating its peroxisomal localization. Next, we tried to increase the amount of peroxisomal Ubp15p by overexpression of Pex15p. The overexpression of this peroxisomal membrane protein leads to an increased recruitment of Pex6p to peroxisomes (37). We assumed that the consequence thereof should be an increased amount of Ubp15p bound to the peroxisomal membrane as it is a binding partner of the Pex6p complex. Indeed, upon Pex15p overexpression, only a small portion of GFP-Ubp15p was cytosolic, whereas the major fraction was found co-localized with the peroxisomal marker PTS2-dsRed (Fig. 3B). Taken together, the localization studies indicate that a portion of Ubp15p is associated with peroxisomes.

FIGURE 3.

Ubp15p is partially localized to peroxisomes. A, a cell-free extract of oleate-induced wild-type cells expressing genomically tagged Ubp15p (Ubp15p-TEV-ProtA) was separated by density gradient centrifugation (2.25–24% OptiPrep, 18% sucrose). Fractions were subjected to measurements of the activity of catalase and cytochrome (Cyt.) c oxidase as peroxisomal and mitochondrial markers, respectively (upper panel). Equal portions of fractions were probed by immunoblotting (lower panel) with antibodies against the protein A tag, Pex13p (peroxisomes), porin (mitochondria), and Fbp1p (cytosol). B, wild-type cells expressing both the PTS2 marker protein PTS2-dsRed and GFP-Ubp15p with and without overexpression of Pex15p were grown on oleic acid plates for 2 days and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Although only a small portion of GFP-Ubp15p was localized to peroxisomes in cells containing normal levels of Pex15p, a higher fraction of the fusion protein was recruited to peroxisomes upon overexpression of Pex15p as indicated by the co-localization of GFP-Ubp15p and the peroxisomal dsRed marker. rel., relative.

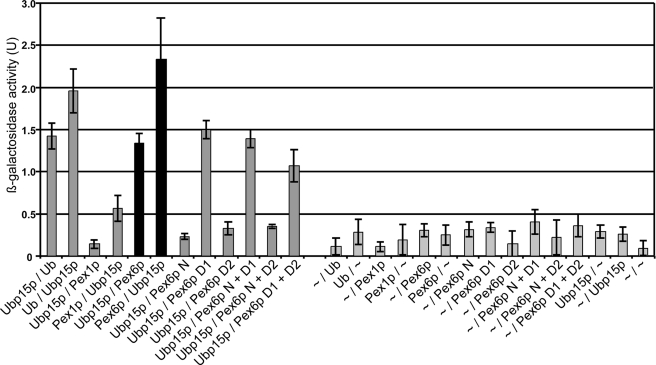

Ubp15p Interacts with First AAA Domain of Pex6p

To analyze the Ubp15p interaction with the peroxisomal AAA complex in more detail, we applied the yeast two-hybrid system. Plasmids expressing full-length Pex1p, Pex6p, or ubiquitin fused to the Gal4p activation domain or the Gal4p DNA-binding domain were transformed in the S. cerevisiae strain L40, and reporter gene expression was analyzed by assaying β-galactosidase activity. In line with previous findings (57), co-expression of Ubp15p with ubiquitin led to significant reporter gene activity as judged by the determined β-galactosidase activity, which indicated the known Ubp15p-ubiquitin interaction (Fig. 4). The enzyme activities differed depending on whether Ubp15p was fused to the DNA-binding domain or the transactivation domain of Gal4p; however, in the case of interaction, the enzyme activity was significantly higher than that of the empty vector controls versus bait plasmids. Comparison of the different assays revealed that Pex6p interacts with Ubp15p, whereas the monitored β-galactosidase activity was only slightly above the control level when Pex1p was tested for interaction with Ubp15p. To determine the Pex6p region that contributes to the Ubp15p interaction, we analyzed the interaction of Ubp15p with the N-terminal region (N-domain; amino acids 1–428), the first AAA cassette (D1 domain; amino acids 421–716), and the second AAA cassette (D2 domain; amino acids 704–1030) of Pex6p and combinations thereof. As shown in Fig. 3, neither the N-domain nor the second AAA domain is capable of interacting with Ubp15p. In contrast, the first AAA domain of Pex6p alone or fused to the N-domain or D2-domain led to β-galactosidase activity in the same range as observed with full-length Pex6p. Thus, the first AAA domain of Pex6p is involved in the interaction with Pex1p (34, 58) as well as with Ubp15p.

FIGURE 4.

First AAA domain of Pex6p mediates Ubp15p interaction. The L40 reporter yeast cells were co-transformed with empty two-hybrid plasmids pPC86 and pPC97 (∼) or plasmids expressing the indicated proteins. Double transformants were lysed and subjected to a liquid β-galactosidase assay. β-Galactosidase activities (expressed in arbitrary units (U)) indicate binding and are represented as mean values of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Error bars denote S.E. N, N-terminal domain; D1, first AAA domain; D2, second AAA domain.

Ubp15p Facilitates Deubiquitination of Pex5p in Vitro

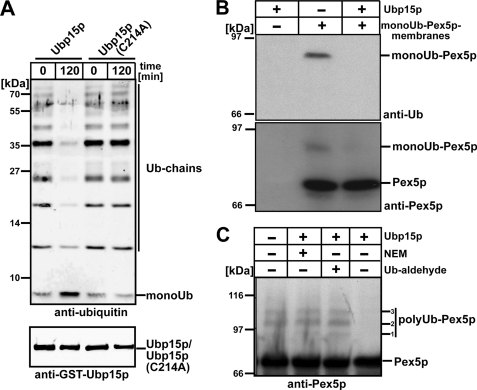

UBPs represent a subclass of the DUBs, comprising 18 putative members in S. cerevisiae, including Ubp15p (53). The UBP family is highly divergent, but all members contain several short consensus sequences, the Cys and the His boxes that are likely to form a part of the active site (59). Within Ubp15p, the Cys box covers amino acids 206–223, whereas the His box is localized between amino acids 449 and 533 (60). Sequence alignment of Ubp15p with other UBPs indicated that Cys-214 of Ubp15p most likely represents an amino acid residue that is crucial for the deubiquitinating activity (60). Accordingly, a Cys-214 to Ala substitution was introduced into the full-length protein by site-directed mutagenesis, and recombinant wild-type or mutant Ubp15p (Ubp15pC214A) fused to GST was expressed in E. coli and isolated by affinity chromatography. The tag was removed by thrombin cleavage. To demonstrate that recombinant Ubp15p exhibits deubiquitinating activity and is thus biologically active, in vitro ubiquitin cleavage assays were performed. To this end, the isolated proteins were incubated with Ub chains, and the reaction was stopped after 0 (control) or 120 min by addition of SDS sample buffer and subsequent boiling. Cleavage of the Ub chain was monitored by immunoblot analysis with an antiserum against ubiquitin. Incubation of the Ub chain with wild-type Ubp15p resulted in a decrease of higher molecular Ub species and accumulation of monoUb as a cleavage product (Fig. 5A, lane 2). When the assay was performed with mutated Ubp15p, no difference between the control sample and the sample incubated for 120 min (Fig. 5A, lanes 3 and 4) was observed. Thus, our data are clear in that Ubp15p acts as a ubiquitin hydrolase on Ub chains and that an enzyme harboring the C214A replacement is enzymatically inactive. This finding is not due to a dramatic influence of the mutation on the structure of the protein as both wild-type and mutated Ubp15p exhibited the same behavior when analyzed by size exclusion chromatography (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Ubp15p is a ubiquitin hydrolase acting on poly- as well as monoubiquitinated Pex5p. A, polyUb chains were incubated with recombinant wild-type Ubp15p or mutant Ubp15pC214 harboring a substitution of the supposedly active site cysteine. At the indicated time points, reactions were stopped by adding SDS sample buffer. Equal amounts of the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The presence of the indicated proteins was monitored by immunoblotting with antibodies against ubiquitin and Ubp15p as indicated. Membranes isolated from NEM-treated wild-type cells that harbor monoubiquitinated Pex5p were incubated with recombinant Ubp15p followed by Pex5p immunoisolation (B), or pex1Δpex6Δ cells that contain polyubiquitinated Pex5p were incubated with recombinant Ubp15p without further purification steps (C). The presence of either NEM or Ub-aldehyde inhibits hydrolase activity of Ubp15p and serves as a control. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with antibody against ubiquitin or Pex5p-specific antibody as indicated to monitor the presence of ubiquitinated Pex5p. 1,2,3 refer to Pex5p modified with polyubiquitin chains of different length.

Pex5p can be monoubiquitinated (21) or polyubiquitinated (17, 18). In Fig. 1, we showed that the AAA peroxin complex harbors deubiquitinating activity. Next, we addressed whether mono- or polyubiquitinated Pex5p can function as molecular target for deubiquitination by Ubp15p. To this end, we prepared membranes from wild-type cells in the presence of NEM, which results in the accumulation of monoUb-Pex5p. These membranes were incubated with recombinant Ubp15p followed by co-immunoisolation of Pex5p. MonoUb-Pex5p was visible when the membranes were incubated with buffer alone but disappeared upon incubation with Ubp15p (Fig. 5B).

Next, we assayed whether Ubp15p also acts on polyubiquitinated Pex5p. We isolated whole cell membranes from a pex1Δpex6Δ strain. These membranes showed accumulation of polyUb-Pex5p species (Refs. 17 and 18 and Fig. 5C, lane 1). Incubation of these membranes with recombinant Ubp15p resulted in the disappearance of modified Pex5p, indicating that Ubp15p can also cleave off ubiquitin from polyUb-Pex5p (Fig. 5C, lane 4). In line with this finding, no cleavage of Pex5p was observed when Ubp15p activity was blocked by NEM or Ub-aldehyde (Fig. 5C, lanes 2 and 3). Ub-aldehyde inhibits ubiquitin hydrolases by the formation of an extremely tight complex in which the inhibitor is bound to the active site of DUBs (61). Taken together, the data demonstrate that recombinant Ubp15p exhibits ubiquitin hydrolase activity and facilitates deubiquitination of mono- and polyUb-Pex5p.

Clustered Peroxisomes in ubp15Δ Cells

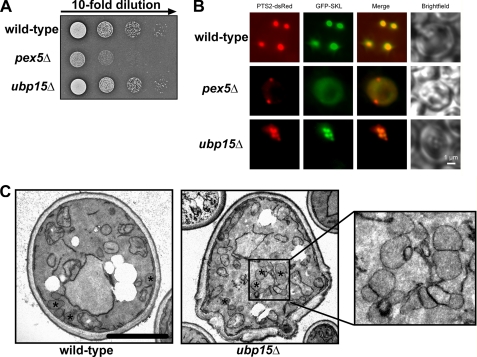

Ubp15p is a cytosolic protein that is associated with the yeast AAA complex. Pex1p and Pex6p are both required for peroxisomal matrix protein import, leading to the question of whether also Ubp15p contributes to peroxisomal function in vivo. To address this question, growth tests were performed on plates containing oleic acid as the sole carbon source that will support cell growth only if peroxisomal β-oxidation is functional, which requires intact organelle biogenesis. In contrast to wild type, PEX5-deficient cells were unable to grow on this medium, which is in accordance with the literature (62) and typical for peroxisomal mutant strains of S. cerevisiae (42). Cells deficient in Ubp15p did not exhibit a growth defect on oleic acid medium (Fig. 6A). As a partial defect in peroxisome biogenesis does not inevitably lead to a complete destruction of peroxisome function, we analyzed matrix protein import in wild type and mutants in more detail. To this end, the subcellular localization of GFP-PTS1 as a marker for the Pex5p-dependent import and PTS2-dsRed, an artificial substrate for the Pex7p-dependent matrix protein import, was monitored by live cell imaging. Fluorescence microscopic inspection of oleic acid-induced wild-type cells revealed a punctate staining pattern for both marker proteins, which is typical for peroxisomal labeling (Fig. 6B). Mutant pex5Δ cells that are affected in the peroxisomal protein import of PTS1 proteins (62) exhibited a cytosolic fluorescence pattern for GFP-PTS1 as typical for these cells. In contrast, the PTS2 pathway was not affected in pex5Δ cells, which results in a punctate staining pattern for PTS2-dsRed. The fluorescence microscopy pattern observed for the ubp15Δ strain was similar to that observed in the wild-type strain (Fig. 6B), suggesting that ubp15Δ cells are still able to import both PTS1- and PTS2-containing peroxisomal matrix proteins. Interestingly, in contrast to wild-type peroxisomes, which were well separated, peroxisomes of ubp15Δ cells appeared to form clusters (Fig. 6B). This observation was corroborated by electron microscopic inspection of wild-type and mutant cells (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

ubp15Δ cells contain functional but clustered peroxisomes. A, indicated strains were spotted as a series of 10-fold dilutions on media containing oleic acid as the sole carbon source and incubated for 5 days at 30 °C. In contrast to pex5Δ, ubp15Δ grew at the wild-type rate, suggesting that the peroxisome function in the cells is not affected. B, the PTS1 marker protein GFP-SKL and the PTS2 marker protein PTS2-dsRed were co-transformed in wild-type, pex5Δ, and ubp15Δ cells. The transformed strains were grown on oleic acid plates for 2 days and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Mutant pex5Δ cells were capable of importing PTS2 proteins properly (indicated by the punctate pattern) but were impaired in PTS1-dependent matrix protein import and accordingly the marker protein was mislocalized to the cytosol. Both wild-type and ubp15Δ cells exhibit a punctate congruent staining for both peroxisomal markers, indicative of normal peroxisomal protein import. The peroxisomes of ubp15Δ cells form clusters. C, ultrastructural appearance of clustered peroxisomes in ubp15Δ cells. Wild-type and ubp15Δ mutant cells were grown on oleic acid medium and analyzed by electron microscopy. In wild-type cells, peroxisomes are separated and distributed within the cell, whereas the ubp15Δ mutant cells are characterized by peroxisome clusters. Peroxisomes are marked with an asterisk. Scale bar, 2.5 μm.

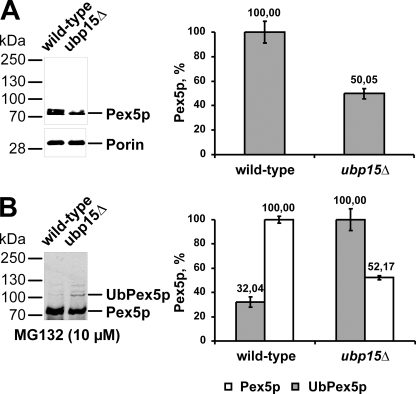

ubp15Δ Cells Exhibit Lower Steady State Concentration of Pex5p but Higher Rate of Ubiquitinated Pex5p

To investigate the consequence of a deletion of UBP15 on the turnover of Pex5p, we estimated the Pex5p steady state concentration in wild-type and ubp15Δ cells. Whole cell lysates of oleic acid-induced wild-type and ubp15Δ cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis with mitochondrial porin as the loading control. Although the porin concentration was the same in both strains, the Pex5p level differed (Fig. 7A, left panel). For quantification of the observed difference, the signal intensity was analyzed by densitometry. It turned out that the amount of Pex5p in ubp15Δ cells was reduced to approximately half of the wild-type level (Fig. 7A, right panel). Next, we analyzed whether the lower amount of Pex5p in ubp15Δ cells is accompanied by a higher ubiquitination rate. To this end, we monitored receptor ubiquitination in cells treated with MG132, which inhibits proteasomal protein degradation and leads to accumulation of ubiquitinated Pex5p (22). Accordingly, ubiquitinated Pex5p was visible in both MG132-treated wild-type and ubp15Δ cells (Fig. 7B, left panel). However, although the level of unmodified Pex5p in ubp15Δ cells was half of the wild-type level as described before (Fig. 7B), ubp15Δ exhibited 3 times more polyubiquitinated Pex5p than the wild-type strain. Taken together, our results indicate a higher polyubiquitination rate of Pex5p in strains lacking Ubp15p, which most likely causes a reduced steady state concentration of the PTS1 receptor.

FIGURE 7.

ubp15Δ cells exhibit lower steady state concentration of Pex5p but higher rate of ubiquitinated Pex5p. A, whole cell lysates of oleic acid-induced wild-type and ubp15Δ cells were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific for Pex5p and mitochondrial porin, which served as a loading control (left). Signal intensity was estimated by densitometric analysis (right). B, indicated strains were grown for 10 h under oleic acid conditions and for an additional 4 h under the same conditions in the presence of MG132 to inhibit proteasomal degradation. Whole cell lysates were prepared, and equal portions were subjected to immunoblot analyses with Pex5p antibodies (left). Signal intensity of modified Pex5p in ubp15pΔ cells and unmodified Pex5p in wild-type cells was quantified by densitometry (right).

ubp15Δ Cells Exhibit Oxidative Stress-related Import Deficiencies and Growth Defect on Oleic Acid

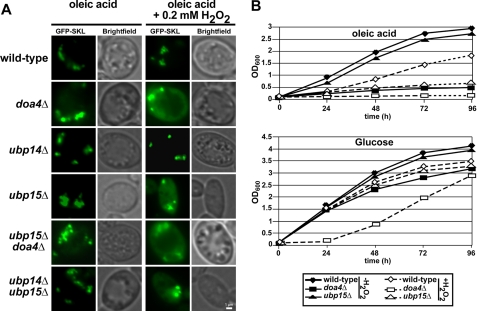

None of the genes encoding ubiquitin hydrolases are essential for viability, suggesting that many of these enzymes have overlapping functions (53). As ubp15Δ exhibited normal growth and matrix protein import under oleic acid conditions, we suspected such a redundancy and tested double deletion strains for growth on oleic acid medium and peroxisomal protein import. Cells lacking Doa4p are characterized by decreased free ubiquitin levels, and these mutants display a strongly reduced turnover of several proteins that are targeted to degradation via ubiquitination. In line with this observation, Doa4p was shown to be involved in cleavage of ubiquitin chains (59). Doa4p is required for turnover of the PTS2 co-receptor Pex18p, which also is ubiquitinated (63). Interestingly, Doa4p interacts with Ubp15p as well as Ubp14p (64, 65). Thus, Ubp15p might be part of a ternary complex of ubiquitin hydrolases with overlapping functions. For this reason, we analyzed single mutants of UBP15, UBP14, and DOA4 as well as combinations thereof for their capacity to import GFP-PTS1. As judged by fluorescence microscopy, neither the single nor the double deletion strains exhibited an import deficiency for GFP-PTS1 (Fig. 8A, left panel). In all strains tested, the GFP-SKL exhibited a clear punctate staining, demonstrating its localization in the peroxisomal matrix.

FIGURE 8.

ubp15Δ cells exhibit oxidative stress-related protein import deficiencies and defective growth on oleic acid. A, the PTS1 marker protein GFP-PTS1 was transformed into wild-type and the indicated mutant strains. The transformed strains were grown in liquid oleic acid media in the absence or presence of 0.2 mm H2O2. All strains exhibited normal import of the marker protein GFP-PTS1 on oleic acid medium without oxidative stress. Upon supplementation of the oleic acid medium with H2O2, the marker protein was partially mislocalized to the cytosol in both doa4Δ and upb15Δ cells, whereas wild-type and ubp14Δ cells remained unaffected. B, indicated strains were cultured in either oleic acid or glucose as the sole carbon source in the absence (closed symbols) and presence (open symbols) of 0.2 mm H2O2. At different time points, samples were taken, and the optical density was estimated at 600 nm. Scale bar, 1 μm.

It is well known that the function of redundant protein sometimes becomes essential when cells are under stress (66). To test for this possibility, we examined oleic acid-induced wild-type and mutant cells for matrix protein import upon oxidative stress conditions (0.2 mm H2O2; Ref. 67). Under this condition, neither wild-type nor ubp14Δ cells showed an import defect for GFP-SKL as indicated by the clear punctate staining with no background labeling (Fig. 8A, right panel). In contrast, doa4Δ and ubp15Δ cells showed a punctate staining of the peroxisomal matrix marker GFP-SKL but also a background labeling indicative for a partial mislocalization of the marker protein to the cytosol. This finding indicated that these mutants exhibit a partial peroxisomal protein import defect upon oxidative stress. In this respect, it is worth noting that expression of Ubp15p and Dao4p but not of Ubp14p is induced by oleic acid (68). Moreover, Doa4p and Ubp15p are also induced upon oxidative stress caused by H2O2 (69). Our data indicate that deficiency in both Ubp15p and Doa4p affects proper peroxisomal protein import under oxidative stress conditions.

To support this observation of an impaired peroxisomal function under oxidative stress, we monitored the growth behavior of UBP15-affected cells in comparison with wild-type and doa4Δ cells. Cells were grown on either glucose or oleic acid as the sole carbon source in the absence or presence of 0.2 mm H2O2. As judged by optical density measurements, wild-type and ubp15Δ cells exhibited similar growth rates when glucose served as the energy source (Fig. 8B, lower panel). When H2O2 was added to the media, growth rates of these strains were nearly the same as those without oxidative stress. In contrast, doa4Δ cells showed the lowest growth rate of the monitored strains already without H2O2, but growth was significantly delayed in the presence of H2O2. When cells were cultured on oleic acid medium, growth of doa4Δ cells was drastically reduced (Fig. 8B, lower panel), which is in line with the known pleiotropic effects of the deletion of this protein as Doa4p is involved in many Ub-dependent processes in the cell (70). The growth rate of wild-type and ubp15Δ cells was similar on glucose medium also under oxidative stress conditions. Both strains also grew equally well on oleic acid medium without H2O2. However, oxidative stress affected growth on oleic acid medium of both wild-type and ubp15Δ cells; however, although the wild-type still grew reasonably well, growth of the ubp15Δ cells was severely affected (Fig. 8B, lower panel). Taken together, results of the analysis of the mutant phenotypes disclosed a peroxisome- and stress-related defect of ubp15Δ cells.

DISCUSSION

The AAA complex of Pex1p and Pex6p is responsible for the release of the ubiquitinated PTS1 receptor Pex5p from the peroxisomal membrane, which has been regarded as the final step of the peroxisomal protein import cascade. In this work, we show that the AAA complex is also responsible for receptor deubiquitination, which is supposed to be an important step in receptor recycling. We have identified the corresponding ubiquitin hydrolase Ubp15p as a novel factor that accompanies the AAA complex in peroxisomal protein import.

PolyUb-Pex5p (17, 18) and monoUb-Pex5p (21, 27) are solely found in the peroxisomal membrane fraction in wild-type yeast and rat liver cells, indicating that Pex5p ubiquitination exclusively takes place at the peroxisomal membrane. Interestingly, exported Pex5p appears to be unmodified, indicating that the Ub moiety is removed during or directly after receptor export (10, 11, 21). However, published data on the deubiquitination of Pex5p so far have focused on in vitro assays with mammalian Pex5p. Soluble monoUb-Pex5p is formed when the in vitro export reaction is performed in the presence of DUB inhibitors (11, 27). Accordingly, it was concluded that deubiquitination of Pex5p occurs predominantly in the cytosol after release from the membrane. It also was suggested that a small fraction of the dislocated Ub-Pex5p in vitro can be deubiquitinated by reducing reagents like glutathione, whereas most of the Ub-Pex5p is deubiquitinated via an enzymatic pathway (27). However, cleavage of the Ub moiety from mammalian Pex5p was thought to be catalyzed by an unspecific reaction that could be carried out by any DUB in the cytosol or may even occur via a non-enzymatic reaction. Our data indicate that deubiquitination of yeast Pex5p represents a specific and important event for the optimal functionality of the export machinery. With Ubp15p, we have identified a deubiquitinating enzyme that is dedicated for this deubiquitination event in bakers' yeast. The deubiquitinating activity found to be associated with the endogenous AAA complex was the first indication for the presence of such an enzyme. Mass spectrometry analysis of the AAA complex derived from endogenous proteins as well as overexpressed Pex6p revealed a stable association of Ubp15p. The interaction with Pex6p was confirmed by yeast two-hybrid analysis, and the interaction site could be mapped to the D1 domain of Pex6p. Although the evolutionarily related AAA protein Cdc48p (p97/VCP) utilizes several cofactors (71), Ubp15p is only the second known cofactor that accompanies the function of Pex6p; its membrane anchor Pex15p (Pex26p in mammals) is the first cofactor (37). Pex6p acts in concert with Pex1p as a dislocase complex for the ubiquitinated Pex5p to facilitate the export of the PTS1 receptor back to the cytosol (8, 9). This leads to the intriguing question of how the activity of the deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp15p is coordinated with the Ub-dependent dislocation of Pex5p from the membrane and release into the cytosol. The finding that the deletion of UBP15 did not result in a complete peroxisomal biogenesis defect can either be explained by the model that deubiquitination has only modulating activity or it may indicate the existence of additional factors that may accompany the AAA complex in its function. This situation could well be explained by redundant DUBs acting on Ub-Pex5p. Possible candidates are the known Ubp15p binding partners Ubp14p and Doa4p (Ubp4p) (64, 65). However, the characterization of the single deletion strains suggested that these two DUBs do not have a peroxisome-specific function similar to Ubp15p. The single deletion strain of Ubp14p had no significant effect on peroxisome morphology or cargo import under both oleate and H2O2 stress conditions. Previous studies have suggested a role for Ubp14p in the disassembly of unanchored polyubiquitin chains (64). The deletion of Doa4p had an effect on the efficiency of peroxisomal cargo import. However, it has to be taken into account that the deletion of Doa4p is known to result in pleiotropic effects on many Ub-dependent processes in the cell as Doa4p influences the homeostasis of free ubiquitin (70). Possibly related to this function, DOA4 is a stress-regulated gene, giving an alternative explanation for the oleate induction reported (68). Thus, although we cannot fully exclude that Doa4p exhibits a peroxisome-related function overlapping with Ubp15p, the partial import defect observed for the doa4Δ strain might well be explained by the pleiotropic phenotype of this mutant.

The observation that ubp15Δ cells contain more clustered peroxisomes than wild-type cells is puzzling. Earlier work correlated a reduced level of imported matrix proteins such as catalase and the occurrence of clustered peroxisomes (72). Slowing of Pex5p cycling is most certainly associated with reduced import rates. Interestingly, induction of oxidative stress by treating cells with hydrogen peroxide causes Pex5p to amass on the organelle membrane and significantly reduces PTS1 protein import (73–75). As our data are clear in that Ubp15p can deubiquitinate Pex5p and as the ubiquitination status of the PTS1 receptor directly influences its cycling (10, 11), it is conceivable that the deletion of Ubp15p influences the import process of PTS1 proteins like catalase and thus possibly also morphology and clustering of peroxisomes.

Although Ubp15p is not essential for peroxisomal biogenesis under normal conditions, its regulative function gains significantly more weight when the cells are stressed with H2O2 and require an efficient import of matrix proteins into peroxisomes. Thus, the findings that 1) Ubp15p was stably associated with the export machinery by interacting with Pex6p, 2) a small portion of the protein was associated with peroxisomes, and 3) a partial protein import defect for PTS1 proteins was observed in ubp15Δ cells upon oxidative stress suggest that the deubiquitination, at least in bakers' yeast, is not an unspecific event that takes place at any location in the cytosol as suggested by the mammalian study (27) and support the notion that the detachment of the Ub moiety is a regulated event.

Ubiquitination of the receptor is a precondition for its export (10, 11). In this respect, it is likely that the Pex1p-Pex6p complex recognizes the Ub moiety. This, however, still needs to be shown. The in vitro data demonstrate that the exported import receptor is deubiquitinated. This reflects the in vivo situation in which it is clear that the cytosolic receptor is not ubiquitinated. Thus, the accumulating evidence indicates that the ubiquitin moiety is cleaved off the import receptor during or shortly after export. There are several possible advantages to favor a peroxisome-associated deubiquitination of Ub-Pex5p. This could protect Pex5p from unspecific ubiquitination by detaching Ub moieties from lysine residues or preventing the formation of a polyubiquitin chain at the crucial cysteine residue dedicated to monoubiquitination. This function would ensure an optimal protection and presentation of monoUb-Pex5p to the export machinery. Another possible explanation might be that the deubiquitination step may trigger the efficient release of Pex5p from the export machinery by cleavage of the complex-bound Ub moiety. Furthermore, this mechanism could prevent recognition of the monoUb-Pex5p by the proteasome system to ensure an efficient recycling of the receptor for new matrix protein import cycles.

The finding that both ubiquitinating and deubiquitinating activities are required for the transport of proteins from a membrane to the cytosol is similar to examples in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. The AAA-type ATPase p97 (Cdc48/VCP) is evolutionarily related to the peroxisomal AAA proteins Pex1p and Pex6p (76). Most interestingly, among the growing number of known cofactors and adaptor proteins that p97 utilizes to carry out its different functions are also several deubiquitinating enzymes (71). The mammalian deubiquitinating enzymes YOD1 and Ataxin-3 are p97-associated proteins and function in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway (77–79). Most of the published literature defines both DUBs as a positive regulator of the p97-driven dislocation of the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation substrates most likely by editing the polyUb chains on the substrates themselves to ensure the best fit to downstream Ub receptor proteins.

Ubp15p acts in concert with the AAA peroxins in the matrix protein import cycle of the PTS1 receptor. Pex5p deubiquitination occurs as a highly specific event in yeast, and removal of ubiquitin from the PTS1 receptor Pex5p turns out to be a vital step in the receptor cycle in its own right. Thus, removal of the ubiquitin seems to complete the receptor cycle of Pex5p to make the receptor available for another round of matrix protein import.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ulrike Freimann for technical assistance and to Wolfgang Schliebs for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB642.

- PTS1

- type I peroxisomal targeting sequence

- PTS2

- type II peroxisomal targeting sequence

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- ProtA

- protein A

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- DUB

- deubiquitinating enzyme

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- UBP

- ubiquitin-specific processing protease

- VCP

- valosin-containing protein

- AAA

- ATPases associated with various cellular activities.

REFERENCES

- 1. Motley A. M., Hettema E. H. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 178, 399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoepfner D., Schildknegt D., Braakman I., Philippsen P., Tabak H. F. (2005) Cell 122, 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lam S. K., Yoda N., Schekman R. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21523–21528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schrader M., Fahimi H. D. (2008) Histochem. Cell Biol. 129, 421–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ma C., Subramani S. (2009) IUBMB Life 61, 713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dodt G., Gould S. J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 135, 1763–1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marzioch M., Erdmann R., Veenhuis M., Kunau W. H. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 4908–4918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Platta H. W., Grunau S., Rosenkranz K., Girzalsky W., Erdmann R. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 817–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyata N., Fujiki Y. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 10822–10832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Platta H. W., El Magraoui F., Schlee D., Grunau S., Girzalsky W., Erdmann R. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 197–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carvalho A. F., Pinto M. P., Grou C. P., Alencastre I. S., Fransen M., Sá-Miranda C., Azevedo J. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 31267–31272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams C., van den Berg M., Sprenger R. R., Distel B. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 22534–22543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hicke L., Schubert H. L., Hill C. P. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 610–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cadwell K., Coscoy L. (2005) Science 309, 127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dikic I., Wakatsuki S., Walters K. J. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 659–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erdmann R., Schliebs W. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 738–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kiel J. A., Emmrich K., Meyer H. E., Kunau W. H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1921–1930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Platta H. W., Girzalsky W., Erdmann R. (2004) Biochem. J. 384, 37–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grou C. P., Carvalho A. F., Pinto M. P., Wiese S., Piechura H., Meyer H. E., Warscheid B., Sá-Miranda C., Azevedo J. E. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14190–14197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schliebs W., Girzalsky W., Erdmann R. (2010) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 885–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kragt A., Voorn-Brouwer T., van den Berg M., Distel B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 7867–7874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Platta H. W., El Magraoui F., Bäumer B. E., Schlee D., Girzalsky W., Erdmann R. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 5505–5516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Williams C., van den Berg M., Geers E., Distel B. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374, 620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Komander D., Clague M. J., Urbé S. (2009) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 550–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilkinson K. D. (1997) FASEB J. 11, 1245–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rumpf S., Jentsch S. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grou C. P., Carvalho A. F., Pinto M. P., Huybrechts S. J., Sá-Miranda C., Fransen M., Azevedo J. E. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10504–10513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Güldener U., Heck S., Fielder T., Beinhauer J., Hegemann J. H. (1996) Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 2519–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Girzalsky W., Rehling P., Stein K., Kipper J., Blank L., Kunau W. H., Erdmann R. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 144, 1151–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heinemeyer W., Kleinschmidt J. A., Saidowsky J., Escher C., Wolf D. H. (1991) EMBO J. 10, 555–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vojtek A. B., Hollenberg S. M., Cooper J. A. (1993) Cell 74, 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Erdmann R., Wiebel F. F., Flessau A., Rytka J., Beyer A., Fröhlich K. U., Kunau W. H. (1991) Cell 64, 499–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu C., Apodaca J., Davis L. E., Rao H. (2007) BioTechniques 42, 158, 160,, 162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Birschmann I., Rosenkranz K., Erdmann R., Kunau W. H. (2005) FEBS J. 272, 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Melcher K. (2000) Anal. Biochem. 277, 109–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niedenthal R. K., Riles L., Johnston M., Hegemann J. H. (1996) Yeast 12, 773–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Birschmann I., Stroobants A. K., van den Berg M., Schäfer A., Rosenkranz K., Kunau W. H., Tabak H. F. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2226–2236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stein K., Schell-Steven A., Erdmann R., Rottensteiner H. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6056–6069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Elgersma Y., Kwast L., van den Berg M., Snyder W. B., Distel B., Subramani S., Tabak H. F. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 7326–7341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chevray P. M., Nathans D. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 5789–5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Guarente L. (1983) Methods Enzymol. 101, 181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Erdmann R., Veenhuis M., Mertens D., Kunau W. H. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 5419–5423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grunau S., Lay D., Mindthoff S., Platta H. W., Girzalsky W., Just W. W., Erdmann R. (2011) Biochem. J. 434, 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Messick T. E., Russell N. S., Iwata A. J., Sarachan K. L., Shiekhattar R., Shanks J. R., Reyes-Turcu F. E., Wilkinson K. D., Marmorstein R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 11038–11049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Neuhoff V., Stamm R., Pardowitz I., Arold N., Ehrhardt W., Taube D. (1990) Electrophoresis 11, 101–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wiese S., Gronemeyer T., Ofman R., Kunze M., Grou C. P., Almeida J. A., Eisenacher M., Stephan C., Hayen H., Schollenberger L., Korosec T., Waterham H. R., Schliebs W., Erdmann R., Berger J., Meyer H. E., Just W., Azevedo J. E., Wanders R. J., Warscheid B. (2007) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 2045–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Agne B., Meindl N. M., Niederhoff K., Einwächter H., Rehling P., Sickmann A., Meyer H. E., Girzalsky W., Kunau W. H. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Albertini M., Rehling P., Erdmann R., Girzalsky W., Kiel J. A., Veenhuis M., Kunau W. H. (1997) Cell 89, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rottensteiner H., Stein K., Sonnenhol E., Erdmann R. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4316–4328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ellison M. J., Hochstrasser M. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 21150–21157 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhu Q., Hulen D., Liu T., Clarke M. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7308–7313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Vornlocher H. P., Hanachi P., Ribeiro S., Hershey J. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 16802–16812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Amerik A. Y., Li S. J., Hochstrasser M. (2000) Biol. Chem. 381, 981–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lin C. H., MacGurn J. A., Chu T., Stefan C. J., Emr S. D. (2008) Cell 135, 714–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Entian K. D., Vogel R. F., Rose M., Hofmann L., Mecke D. (1988) FEBS Lett. 236, 195–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huh W. K., Falvo J. V., Gerke L. C., Carroll A. S., Howson R. W., Weissman J. S., O'Shea E. K. (2003) Nature 425, 686–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Peng J., Schwartz D., Elias J. E., Thoreen C. C., Cheng D., Marsischky G., Roelofs J., Finley D., Gygi S. P. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 921–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tamura S., Yasutake S., Matsumoto N., Fujiki Y. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27693–27704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Papa F. R., Hochstrasser M. (1993) Nature 366, 313–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hochstrasser M. (1996) Annu. Rev. Genet. 30, 405–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hershko A., Rose I. A. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 1829–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Van der Leij I., Franse M. M., Elgersma Y., Distel B., Tabak H. F. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11782–11786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Purdue P. E., Lazarow P. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47684–47689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Amerik A. Yu., Swaminathan S., Krantz B. A., Wilkinson K. D., Hochstrasser M. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 4826–4838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Krogan N. J., Cagney G., Yu H., Zhong G., Guo X., Ignatchenko A., Li J., Pu S., Datta N., Tikuisis A. P., Punna T., Peregrín-Alvarez J. M., Shales M., Zhang X., Davey M., Robinson M. D., Paccanaro A., Bray J. E., Sheung A., Beattie B., Richards D. P., Canadien V., Lalev A., Mena F., Wong P., Starostine A., Canete M. M., Vlasblom J., Wu S., Orsi C., Collins S. R., Chandran S., Haw R., Rilstone J. J., Gandi K., Thompson N. J., Musso G., St Onge P., Ghanny S., Lam M. H., Butland G., Altaf-Ul A. M., Kanaya S., Shilatifard A., O'Shea E., Weissman J. S., Ingles C. J., Hughes T. R., Parkinson J., Gerstein M., Wodak S. J., Emili A., Greenblatt J. F. (2006) Nature 440, 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jamieson D. J. (1998) Yeast 14, 1511–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Izawa S., Inoue Y., Kimura A. (1995) FEBS Lett. 368, 73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Smith J. J., Ramsey S. A., Marelli M., Marzolf B., Hwang D., Saleem R. A., Rachubinski R. A., Aitchison J. D. (2007) Mol. Syst. Biol. 3, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gasch A. P., Spellman P. T., Kao C. M., Carmel-Harel O., Eisen M. B., Storz G., Botstein D., Brown P. O. (2000) Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4241–4257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Swaminathan S., Amerik A. Y., Hochstrasser M. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 2583–2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jentsch S., Rumpf S. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 6–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang J. W., Han Y., Lazarow P. B. (1993) J. Cell Biol. 123, 1133–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Legakis J. E., Koepke J. I., Jedeszko C., Barlaskar F., Terlecky L. J., Edwards H. J., Walton P. A., Terlecky S. R. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4243–4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Terlecky S. R., Koepke J. I., Walton P. A. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 1749–1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Petriv O. I., Rachubinski R. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19996–20001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gabaldón T., Snel B., van Zimmeren F., Hemrika W., Tabak H., Huynen M. A. (2006) Biol. Direct 1, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Doss-Pepe E. W., Stenroos E. S., Johnson W. G., Madura K. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6469–6483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang Q., Li L., Ye Y. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7445–7454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ernst R., Mueller B., Ploegh H. L., Schlieker C. (2009) Mol. Cell 36, 28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]