Abstract

Transvection can cause the expression of a gene to be sensitive to the proximity of a homolog. It can account for many cases of intragenic complementation at the Drosophila yellow gene, where one mode of transvection involves the action of enhancers in trans on a promoter present on a separate chromosome. Our goal was to identify cis-acting elements that regulate the trans action of enhancers. Using gene replacement, we altered two core promoter elements at yellow and tested the resulting alleles for their ability to support transvection. We found that the TATA box and initiator element can regulate transvection.

Keywords: Enhancer, pairing, promoter, transcription, transvection, yellow

Homologous sequences can influence each other in profound ways, resulting in changes in gene structure and expression (for review, see Henikoff and Comai 1998). A good example of homolog interaction is transvection, which was defined in Drosophila (Lewis 1954) and is now known to occur elsewhere (for review, see Henikoff and Comai 1998). In Drosophila, somatic homolog pairing brings homologous sequences into proximity. The expression of some genes is sensitive to somatic pairing and these genes are said to exhibit transvection effects. One example of such a gene is yellow (Geyer et al. 1990). The yellow gene is required for cuticle pigmentation and is controlled by several independent tissue-specific enhancers. Mutations in yellow result in decreased pigmentation. Interestingly, some mutant yellow alleles that reduce pigmentation in the same cuticular structures are able to complement each other in pairwise combinations to give a nearly wild-type phenotype. This form of intragenic complementation can be explained by transvection.

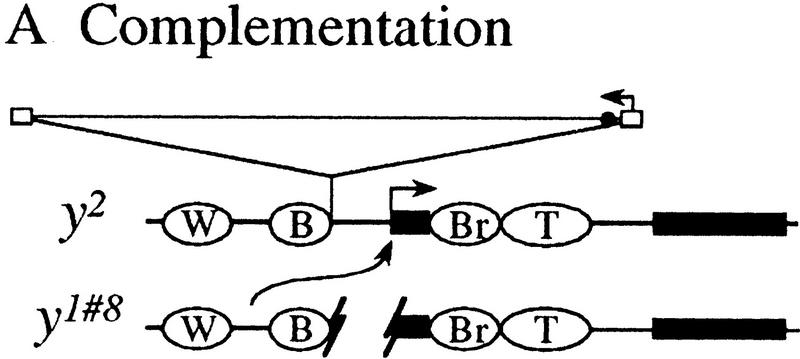

One mode of transvection at yellow entails the action of enhancers in trans on the promoter of a paired homolog (Geyer et al. 1990; Morris et al. 1998). Figure 1A illustrates this mechanism with the y2 and y1#8 alleles (Geyer et al. 1990). The y2 allele results from the insertion of a gypsy retrotransposable element between the promoter and the two enhancers directing expression in the wings and body. When gypsy is bound by the Suppressor of Hairy wing [Su(Hw)] protein, it establishes a chromatin insulator (for review, see Dorsett 1996; Gdula et al. 1996; Geyer 1997) that prevents the wing and body enhancers from communicating with the promoter, and therefore, y2 flies have mutant wing and body pigmentation. The y1#8 allele is a null that is associated with a 780-bp deletion removing the promoter. Although homozygous y2 and y1#8 flies show mutant wing and body pigmentation, y2/y1#8 flies show almost wild-type pigmentation. This intragenic complementation can be explained by the action of the wing and body enhancers of y1#8 in trans on the y2 promoter (Geyer et al. 1990).

Figure 1.

A model to explain complementation patterns at yellow (Geyer et al. 1990). (A) The y1#8 allele complements y2 to give flies with nearly wild-type pigmentation. The model suggests that the wing and body enhancers of y1#8 act in trans on the promoter of the y2 allele. (B) The y1 allele does not complement y2. The intact promoter region of y1 may preclude the action of enhancers in trans. (W) Wing enhancer; (B) body enhancer; (Br) bristle enhancer; (T) tarsal claw enhancer; (solid rectangle) exon; (open rectangle) gypsy long-terminal repeat (LTR); (large arrow above exon) transcription from yellow promoter; (small arrow above LTR) transcription of gypsy; (●) su(Hw)-binding region. There are 17 bp of P-element sequence at the breakpoints of y1#8 (Geyer et al. 1990).

Although the wing and body enhancers of some yellow alleles are able to act in trans on the y2 promoter, the enhancers of other yellow alleles cannot. For example, the y1 allele, which is caused by an A to C mutation in the translation initiation codon, has intact wing and body enhancers, but fails to complement y2 (Fig. 1B; Geyer et al. 1990). This observation suggests that the action of enhancers in trans on a paired promoter is not always possible, that it occurs only under certain circumstances. In this way, transvection is a regulated process at yellow.

We are interested in the molecular basis for the regulation of transvection. Previous studies at yellow delineated a large region encompassing the promoter as a key player in that its presence appeared to inhibit transvection (Geyer et al. 1990; Morris et al. 1999). For example, y1#8, which lacks this region, can participate in transvection, while y1, which carries this region, cannot. The importance of the promoter region is also highlighted by findings at the Ultrabithorax (Ubx; Martínez-Laborda et al. 1992; Casares et al. 1997) and Abdominal-B (Hendrickson and Sakonju 1995; Sipos et al. 1998) genes. Our goal has been to identify the elements that regulate transvection at yellow. Here, we present our studies that were prompted by the presence of the promoter within the delineated region. It has been proposed that cis-preference of enhancers for their own promoter precludes their action in trans (Geyer et al. 1990; Martínez-Laborda et al. 1992; Hendrickson and Sakonju 1995; Casares et al. 1997; Sipos et al. 1998; Morris et al. 1999). Our strategy involved the introduction of mutations into putative core promoter elements and assessment of the resulting yellow alleles for their ability to support transvection.

Results and Discussion

We focused first on the putative TATA box of yellow, extending from −32 to −24 relative to the transcription start site (Chia et al. 1986; Geyer et al. 1986). Our method of mutagenesis was targeted gene replacement at the endogenous locus. This approach does not compromise the ability of yellow alleles to pair and is required because ectopically located yellow transgenes have not been observed to pair and promote transvection with the endogenous yellow gene (Geyer et al. 1990).

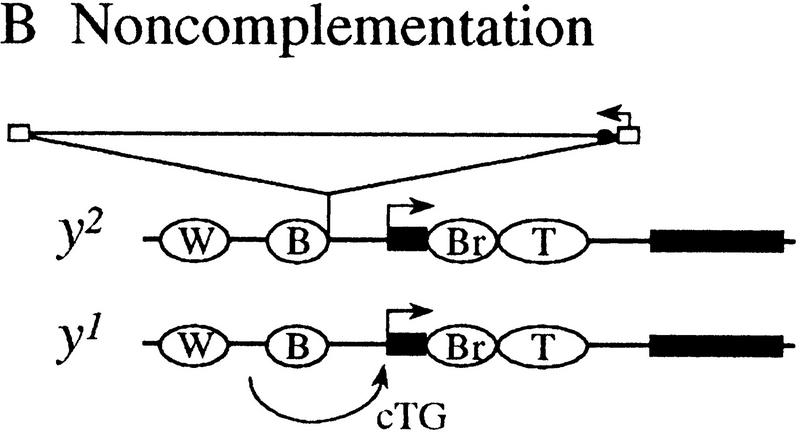

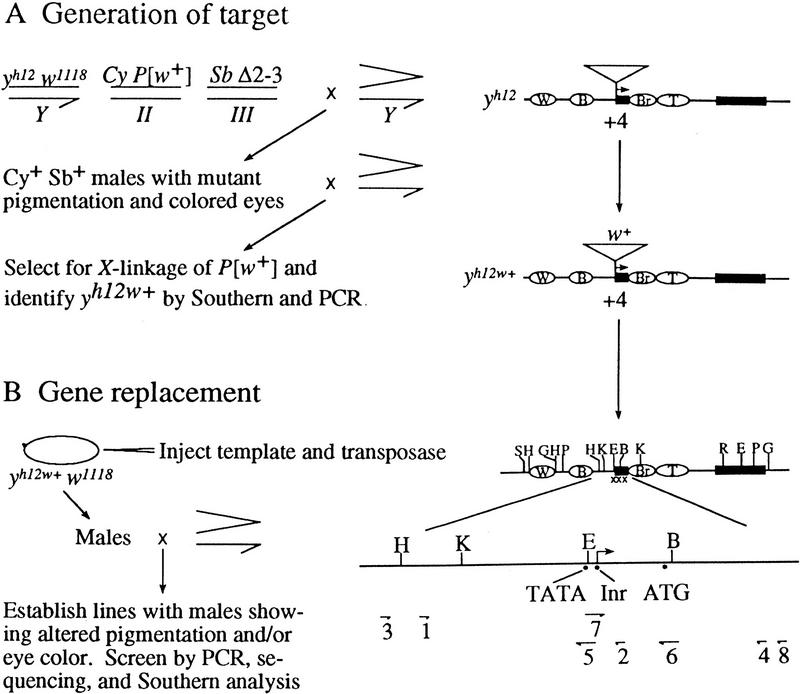

Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila involves the excision of a marked P element followed by gap repair from a template (Fig. 2; Keeler et al. 1996). To generate a marked P element in yellow, we began with an allele, yh12, that is associated with an unmarked P element at +4 relative to the transcription initiation site (Geyer et al. 1990). We then used targeted transposition (e.g., see Heslip and Hodgetts 1994) to substitute the internal sequences of the yh12 P element with sequences containing the white+ marker gene (Fig. 2A). The resulting yellow allele, called yh12w+, became our target for the introduction of sequence changes from a plasmid template (Fig. 2B). Using this strategy, we replaced 6 bp of the wild-type TATA box with the 6-bp recognition site for the SmaI restriction enzyme (Table 1). Introduction of the SmaI site allowed us to use restriction analysis of PCR-amplified fragments in the identification of gene convertants. Changes were subsequently confirmed by sequencing, and the integrity of the yellow locus was ascertained by Southern analysis. The new yellow allele with a mutant TATA box is called ytata (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Scheme for targeted gene replacement. (A) Generation of yh12w+ by targeted transposition (Heslip and Hodgetts 1994). Males carrying yh12 w1118, P[w+], and a source of transposase (Δ2-3) were mated to attached-X (>) females. Of the 1500 progeny, 106 males were selected as candidates for targeted transposition events by the indicated phenotype. Candidates were singly mated to attached-X females, and two were shown to be true examples of targeted transposition by (1) demonstration of X-linkage of the w+, (2) Southern analysis of genomic DNA digested separately with BamHI–BglII, HindIII–BamHI, and PstI (Boehringer-Mannheim) and probed with full-length yellow sequence, and (3) PCR analysis with primers in yellow and white (not shown), and primers 1 and 2, which flank the insertion site. (B) Gene replacement (Keeler et al. 1996). yh12w+ w1118 embryos were injected with template sequences and the transposase-encoding helper plasmid (W. Bender, unpubl.) at concentrations of 1 and 0.25 mg/ml, respectively. Surviving males were crossed to attached-X females and male progeny with altered pigmentation and/or eye color were singly mated to attached-X females to establish lines. These lines were screened by single-fly PCR (Czank 1996) with primers 1 and 2, which gives a 519-bp PCR product, followed by digestion of the product with restriction enzymes diagnostic of the desired changes (Table 1). Candidate lines were verified by sequence and Southern analyses. Sequence analyses were carried out on a 973-bp PCR product generated from genomic DNA with primers 3 and 4. Southern analyses of genomic DNA digested separately with HindIII–BamHI, PstI, and EcoRI (Boehringer-Mannheim) and hybridized to a full-length yellow probe gave patterns identical to those of wild-type flies (data not shown). Symbols are as in Fig. 1; (triangle) P-element insertion; (xxx) mutated sequence; (B) BamHI; (G) BglII; (E) EagI; (H) HindIII; (K) KpnI; (P) PstI; (R) EcoRI; (S) SalI.

Table 1.

Targeted gene replacement at yellow

|

Homozygous ytata/ytata and hemizygous ytata/Df flies showed a reduction in the pigmentation of all adult cuticular structures (Table 2). For example, the wings showed intermediate pigmentation, the body showed low-level pigmentation, and the bristles showed fully mutant pigmentation. These observations demonstrate that ytata compromises transcription, and therefore, that the putative TATA box is functional.

Table 2.

Complementation data

|

|

Df

|

Homozygous

|

2

|

62a

|

82f29

|

2374

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Df | 1, 1 | — | 1, 1 | 1, 4 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 |

| Homozygous | — | — | 1, 1–2 | 1, 3 | 1, 1a | 1, 1–2 |

| tata | 2–3, 1 | 3, 2 | 4, 3 | 4, 4 | 3, 1–2 | 4, 3 |

| inr | 5, 4 | 5, 5 | 5, 5 | 5, 5 | 5, 5 | 5, 5 |

| tata–inr | 2, 1 | 2, 1 | 4, 3–4 | 4, 4 | 3, 1–2 | 4, 3 |

| tata-1 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 3, 2–3 | 2, 4 | 2, 1–2 | 3, 2–3 |

| inr-1 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 3, 2–3 | 2, 4 | 2, 1–2 | 3, 2–3 |

| tata–inr-1 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 4, 3–4 | 3, 4 | 3, 1–2 | 4, 3 |

| 1#8 | 1, 1 | 1, 1 | 4, 4 | 4, 4 | 3, 3 | 4, 4 |

Pigmentation scores for wings and body (wings, body) when alleles are in trans to a deficiency (Df), homozygous, or in trans to one of the alleles listed at the top. Scores in boldface type indicate complementation. The y1 allele behaved like Df in complementation tests involving each promoter mutation, as did y1#8 in trans to ytata-1, yinr-1, and ytata–inr-1. Flies bearing y1#8 in trans to ytata, yinr, or ytata–inr showed slightly darker pigmentation compared to flies bearing Df in trans to these three promoter mutations, suggesting that these altered promoters can receive enhancer input in trans.

The scores given were all obtained in the laboratory of C.-t.W. We note that y82f29/y82f29 flies give a score of 1, 1–2 in the laboratory of P.K.G. The difference may be due to culture condition.

We placed ytata in trans to y2 and discovered that ytata can support transvection. The wings and body of y2/ytata flies were darker than the wings and body of flies homozygous or hemizygous for either y2 or ytata (Table 2). This finding has two implications. First, ytata identifies 6 bp that, when mutant, allow transvection to proceed, and represents the most precise definition, to date, of an element that acts in cis to determine whether transvection can occur. Second, the 6 bp implicate a promoter element in the regulation of transvection.

Although the model for transvection shown in Figure 1 predicts that complementation between y2 and ytata results from the ytata enhancers activating transcription from the y2 promoter, it is formally possible that complementation arises from pairing-mediated activation of the ytata promoter. For instance, pairing-mediated activation of transcription has been reported for Ubx (Goldsborough and Kornberg 1996). To address this issue, we used targeted gene replacement to generate a derivative of ytata that is disrupted post-transcriptionally and, therefore, unable to contribute to a complementing phenotype. This derivative, called ytata-1, bears the A → C change in the translation initiation codon that is found in y1 (Table 1). As anticipated, homozygous and hemizygous ytata-1 flies showed fully mutant pigmentation in all cuticular structures (Table 2). The ability of ytata-1 to support transvection was determined by placing it in trans to y2. We found that ytata-1 complements y2, with wing and body pigmentation of y2/ytata-1 flies significantly darker than that of either parental line (Table 2). This result demonstrates that when ytata-1 complements y2, the promoter of y2 is activated in trans.

We asked whether ytata-1 could complement alleles other than y2 by placing ytata-1 in trans to three additional alleles: y62a, y82f29, and y2374. These alleles are similar to y2 in that they complement y1#8 and fail to complement y1 (Morris et al. 1998, 1999), and together with y2 will be referred to as tester alleles. The y62a allele is structurally disrupted in the vicinity of the wing and body enhancers and, although it produces significant levels of pigmentation in the body, pigmentation in the wings is minimal (Chia et al. 1986; Morris et al. 1999). The y82f29 allele is caused by a deletion of the wing and body enhancers and produces very little, if any, pigmentation in the wings and body (Morris et al. 1998, 1999). The y2374 allele carries a large insertion between the promoter and the wing and body enhancers, and also produces very little, if any, pigmentation in the wings and body (Morris et al. 1999). We placed ytata-1 in trans to y62a, y82f29, and y2374 and found that it complements each allele (Table 2). These findings demonstrate that the ability of ytata-1 to activate a promoter in trans is not specific for the y2 allele.

Our data regarding the TATA box suggest that core promoter elements can participate in the regulation of transvection at yellow. To pursue this idea, we determined the role of another potential yellow core promoter element, the putative initiator (Inr) that encompasses the transcription start site (Arkhipova 1995; Emami et al. 1997). We replaced 6 bp of the putative Inr with the 6 bp recognition site for the ClaI restriction enzyme and called the new allele yinr (Table 1). In contrast to the mutation in the TATA box, mutation of the Inr caused only a slight reduction in yellow expression as judged by pigmentation levels (Table 2). Homozygous yinr/yinr flies showed wild-type wing, body, and bristle pigmentation, while hemizygous yinr/Df flies showed only a slight reduction in body pigmentation as compared to pigmentation levels seen in y+/Df flies.

To determine the effect of the Inr mutation on transvection, we made a companion allele, as was done for ytata. This allele, yinr-1, carried an A → C change in the translation initiation codon in addition to the changes in the Inr and produced a fully mutant pigmentation phenotype. We placed yinr-1 in trans to the four tester alleles and found that it supports complementation (Table 2). The level of complementation was similar to that seen with ytata-1.

Finally, we made two additional alleles, ytata-inr and ytata-inr-1, in which both the TATA box and Inr had been mutated and where ytata-inr-1 also carried a mutated translation initiation codon (Table 1). The doubly mutant ytata-inr/ytata-inr flies showed a reduction in wing, body, and bristle pigmentation that was more severe than that seen in flies homozygous for either ytata or yinr (Table 2). These phenotypes are consistent with studies showing functional synergy between the TATA box and Inr (Emami et al. 1997). We placed ytata-inr-1 in trans to all four tester alleles and observed complementation in each case. The level of complementation was greater than levels seen with either ytata-1 or yinr-1 (Table 2).

In short, our data show that mutations in the TATA box and Inr induce transvection and that they do so by activating gene expression from a promoter in trans. How might promoter mutations in one allele induce expression from the promoter of a paired allele? One attractive explanation proposes that ytata and yinr influence transvection as a direct consequence of their effects on the transcriptional process. As noted earlier, transvection may be regulated by cis preference of enhancers for their own promoter. If so, ytata and yinr may induce transvection because disruption of transcription leads to the release of enhancers from cis preference. In this way, our observations parallel studies addressing the mechanism by which enhancers select among multiple cis-linked promoters (Blackwood and Kadonaga 1998) and indicate that the parameters governing promoter choice in cis may also apply in trans. Specifically, the commitment of an enhancer for a particular promoter may reflect promoter strength, accessibility (e.g., see Geyer et al. 1990; Martínez-Laborda et al. 1992; Cai and Levine 1995; Hendrickson and Sakonju 1995; Scott and Geyer 1995; Casares et al. 1997; Dillon et al. 1997; Krebs and Dunaway 1998; Sharpe et al. 1998; Sipos et al. 1998; Tilghman et al. 1998; Morris et al.1999) and/or identity as determined by sequence or associated factors (e.g., see Hirschman et al. 1988; Li and Noll 1994; Hansen and Tjian 1995; Merli et al. 1996; Ohtsuki et al. 1998; Sharpe et al. 1998). Likewise, at yellow, mutations in core promoter elements may release cis-acting enhancers to act on a promoter in trans because they compromise promoter strength through reduction in transcriptional efficiency, decrease promoter accessibility through alterations in chromatin structure or DNA topology, or change promoter identity through disruption of the TATA box or Inr. The consequence of such events could be that the intact promoter in trans becomes more competitive for the input of the enhancers in cis to the promoter mutations. The weakening of a promoter such that it cannot retain transcription factors could also lead to an increased concentration of transcription factors at a paired and functional second promoter, again, causing enhancers to be drawn to the second promoter.

If promoter choice reflects relative promoter appeal, how do yellow enhancers act when paired promoters are identical? The inability of y1 to complement the four tester alleles is informative. As the promoters of the tester alleles are intact and, at this level, identical to the promoter of y1, lack of complementation indicates that cis preference dominates. It may be that mechanisms of enhancer–promoter interaction (Blackwood and Kadonaga 1998) favor interactions between cis-linked, over unlinked, elements. We note, however, one caveat. The lesions of the tester alleles, while outside the promoter region, may compromise the promoters of the tester alleles such that they are unable to compete effectively with the promoter of y1. That is, cis preference of y1 enhancers may be accentuated by a reduced potential of the promoter in trans.

How, then, might yellow enhancers act when the paired alleles are identical throughout, such as in the case of paired wild-type genes? It is plausible that cis action will prevail. Again, arguments of linkage may favor cis action. Trans action might also be inhibited because a wild-type promoter that is fully engaged with its cis enhancers might not be able to receive input in trans (see also Sipos et al. 1998), although this does not appear to be the case at Ubx (Martínez-Laborda et al. 1992). It is equally plausible that when faced with identical promoters, enhancers will be free to act in cis or trans, as has been demonstrated with catenated plasmids in a Xenopus oocyte system (Krebs and Dunaway 1998). While our data do not address the situation where genes are identical, they do suggest that enhancers that are able to act in trans may still be able to act in cis, consistent with the behavior of regulatory elements at the bithorax gene complex (Lewis 1955; and most recently, Goldsborough and Kornberg 1996; Casares et al. 1997; Sipos et al. 1998). In the case of yellow, the pigmentation seen in flies that bear a tester allele in trans to ytata or yinr is darker than that of flies bearing the tester allele in trans to ytata-1 or yinr-1 (Table 2). This observation indicates that ytata and yinr are contributing directly to the pigmentation levels and, therefore, are transcriptionally productive even as they participate in transvection.

The higher degree of transvection supported by ytata-inr as compared with that supported by ytata or yinr is consistent with transcription-based interpretations because, by pigmentation levels, ytata-inr is more compromised than ytata and yinr (Table 2). The comparable levels of transvection supported by ytata and yinr, though, were not expected as yinr flies are much more pigmented than ytata flies. If pigmentation levels are a good indicator of transcriptional competency, then the similar levels of transvection seen with ytata and yinr may indicate that degree of transvection does not directly correlate with degree of transcription. The actual relationship between levels of transcription and pigmentation, however, is not known for yellow.

Transcription-based mechanisms for promoter choice are attractive because the mutations we made are in core promoter elements. Nevertheless, we are considering the possibility that promoter elements also influence transvection via routes that are independent of the transcriptional process. For instance, transvection might normally be inhibited by the packaging of homologous chromosomes in a way that favors intramolecular over intermolecular interactions (Martínez-Laborda et al. 1992; Wu and Howe 1995; Sipos et al. 1998). If so, small sequence changes, such as ytata and yinr, might alter relative homolog accessibilities or, if sequences within a wild-type promoter are important for homolog sequestration, ytata and yinr might act by disrupting the insular state. Alternatively, the changes in ytata and yinr may influence a promoter in trans by virtue of their effect on pairing. For example, if sequences in, or factors associated with, the promoter region are essential for homolog pairing (Jorgensen 1990; Cook 1997; McKee 1998), ytata and yinr may lead to local unpairing of the promoter in trans, resulting in its greater accessibility and ultimate activation. Intriguingly, this structural interpretation can explain why ytata and yinr support transvection equally; the magnitude of their lesions is the same. Also consistent with this view are studies suggesting that yellow alleles bearing deletions or insertions in the promoter region induce transvection by causing pairing-mediated changes in gene topology (Morris et al. 1998, 1999; Sipos et al. 1998). In fact, in genotypes involving y2, such changes may be responsible for a second mode of transvection in which the y2 wing and body enhancers bypass the gypsy insulator to activate the y2 promoter (Morris et al. 1998). If ytata and yinr can cause this mode of transvection, then insulator bypass may contribute to the complementation observed when these alleles are paired with y2.

Finally, we note that none of our promoter mutations achieves the uniformly high level of transvection that is seen with y1#8 (Table 2). It may be that stronger degrees of transvection require maximal disruption of transcription and/or severe structural disruption of the promoter, both of which characterize y1#8. For example, yellow may carry promoter elements, in addition to the TATA box and Inr, whose presence inhibits transvection. Alternatively, there may be as-yet-unidentified elements present in our mutant promoter alleles, but absent from y1#8, that are independent of promoter function but which down-regulate transvection. In fact, there is evidence for the ability of special elements, in particular insulators, to confer cis preference on enhancer–promoter interactions in plasmid-based assays (Krebs and Dunaway 1998) and for the existence of nonpromoter elements regulating transvection at Abdominal-B (Hendrickson and Sakonju 1995; Hopmann et al. 1995; Sipos et al. 1998).

In summary, our data demonstrate that the TATA and Inr promoter elements play key roles in the regulation of transvection at yellow. These results are particularly exciting in light of suggestions that the promoter may participate in other pairing-mediated processes (Jorgensen 1990; Lichten and Goldman 1995; Cook 1997; McKee 1998). Specifically, promoter elements have been implicated in meiotic recombination in yeast (Lichten and Goldman 1995) and in meiotic pairing and segregation of the X and Y chromosomes in Drosophila (McKee 1998). The importance of promoter elements in these meiotic events, as well as in transvection-modulated gene expression in nonmeiotic tissues, argues strongly that transcriptional regulatory elements and pairing-mediated processes, while distinct, are intimately linked.

Materials and methods

Drosophila stocks

Df represents the Df(1)y− ac− w1118 chromosome, which lacks the entire yellow gene (Morris et al. 1998). The w1118 marker is a null allele of the white eye color gene, and the Cy wing and Sb bristle mutations are dominant markers on the CyO second chromosome balancer and TMS third chromosome balancer, respectively (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). For simplicity, Figure 2 notes the dominant markers but does not give the names of the balancer chromosomes. The attached X chromosome we used was FMA3 (Lindsley and Zimm 1992). P[w+] is a transposon carrying a wild-type w+ gene, and P[ry+ Δ2-3](99B), abbreviated Δ2-3, is a transposon encoding transposase (Keeler et al. 1996 and references within).

Culture condition

Flies were cultured at 25 ± 1°C on standard Drosophila cornmeal, yeast, sugar, and agar medium with p-hydroxybenzoic acid methyl ester added as a mold inhibitor. Three females were mated with three or more males in vials and brooded daily. Temperature and crowding were carefully controlled as both affect pigmentation.

Scoring of pigmentation

Pigmentation was scored in 1- to 3-day-old flies on a scale of 1–5, where 1 represents the null or nearly null state, and 5 represents the wild-type or nearly wild-type state. The null phenotype is defined by the pigmentation seen in flies that are homozygous or hemizygous for y1 or Df(1)y− ac− w1118, and the wild-type phenotype is defined by the pigmentation seen in our wild-type Canton S strain. The wing pigmentation score refers to pigmentation of the wing blade but not the wing bristles, and body pigmentation refers to pigmentation of the abdominal stripes. At least two independent crosses were set up for each genotype. Complementation between two alleles was judged to occur when wing or body pigmentation was at least one point darker on the pigmentation scale than the pigmentation of analogous tissues in females that were homozygous for either allele and females that were heterozygous for either allele and Df.

Template construction

The templates used for gene replacement were full-length yellow genes, carrying appropriate sequence changes, cloned into a Bluescript plasmid (Stratagene). The following constructs are named according to the yellow allele that they were used to generate. pUC8ySB is a pUC8 plasmid containing the 5′ 3.1-kb SalI–BamHI yellow fragment, pBSyBG is a Bluescript plasmid containing the 3′ 4.7-kb BamHI–BglII yellow fragment, and pUC8ySG is a pUC8 plasmid containing the entire yellow gene in a 7.8-kb SalI–BglII fragment. For the tata construct, primers 3 and 5 (see below) were used with pUC8ySG to PCR amplify a product that was digested with KpnI and EagI and then cloned into the KpnI and EagI sites of pUC8ySB to make pUC8ySBtata. The SalI–BamHI yellow fragment of pUC8ySBtata was then cloned into the SalI and BamHI sites of pBSyBG to generate a full-length yellow gene. For the remaining constructs, the following strategy was followed. Primers were used to PCR amplify regions of pUC8ySG, and the products were digested with EagI and BamHI and cloned into those sites of either pUC8ySB or pUC8ySBtata. The resulting plasmids were digested with SalI and BamHI and the yellow sequences cloned into those sites of pBSyBG. For the tata–1 construct, primers 3 and 6 were used, and the digested PCR product was cloned into pUC8ySBtata. For the inr and tata–inr constructs, primers 7 and 8 were used, and the digested PCR products were cloned into pUC8ySB and pUC8ySBtata, respectively. For the inr-1 and tata–inr-1 constructs, primers 7 and 6 were used, and the digested PCR products were cloned into pUC8ySB and pUC8ySBtata, respectively.

Primer sequences

The primer sequences used in this study are indicated below. Mutant nucleotides are noted in boldface type and the position of the 5′ base is noted in parentheses after the primer number: 1 (−448) 5′-GAGCCTCCTGGCCTTACAATTTAC; 2 (+71) 5′-GTTCTTCTCTAGCCTTCGGCTGTG; 3 (−547) 5′-GCAGTCGCCGATAAAGATGAACACAG; 4 (+426) 5′-ATTTAACTTCCACTTACCATCACGCC; 5 (−7) 5′-CATAATATGTCGGCCGCGTCCCGGGTGAAGGTTTCTCCGAAGACGAAGACAG; 6 (+206) 5′-GTCACAAGGATCCACCCTTTGTCCTGGAACAGTGCACTTAGCTCTAAGCTGACAATCAC; 7 (−30) 5′-ATAAAACGCGGCCGACATATTATGGCCACATCGATTTACCGCGCCACGGTCCACAGAAG; 8 (+478) 5′-TCTGATGCCCTAAGTAAGAATGTCCC.

Acknowledgments

We thank W. Engels, G. Gloor, K. Keeler, and D. Lankenau for enthusiastic assistance in the design of gene replacement protocols, W. Bender for expertise, equipment, and transposase-encoding helper plasmid, S. Gustincich, R. Mollaaghababa, and P. Sudarsanam for technical advice, F. Winston, H. Genetti, D. Petrov, W. Bender, J.-l. Chen, K. Huisinga, C. Kaplan, K. Scott, and P. Sudarsanam for stimulating discussions, and A. Moran for superb technical assistance. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant to P.K.G., a National Science Foundation grant, an NIH Shannon Award, a Funds for Discovery Exploratory Award, support from the Monsanto Fellowship Program, and generosity of the Richard and Priscilla Hunt Fellowship to C.-t.W.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’ in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL twu@rascal.med.harvard.edu; FAX (617) 432-7663.

References

- Arkhipova IR. Promoter elements in Drosophila melanogaster revealed by sequence analysis. Genetics. 1995;139:1359–1369. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood EM, Kadonaga JT. Going the distance: A current view of enhancer action. Science. 1998;281:60–63. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Levine M. Modulation of enhancer-promoter interactions by insulators in the Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1995;376:533–536. doi: 10.1038/376533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casares F, Bender W, Merriam J, Sánchez-Herrero E. Interactions of Drosophila Ultrabithorax regulatory regions with native and foreign promoters. Genetics. 1997;145:123–137. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia W, Howes G, Martin M, Meng YB, Moses K, Tsubota S. Molecular analysis of the yellow locus of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1986;5:3597–3605. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PR. The transcriptional basis of chromosome pairing. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1033–1040. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.9.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czank A. One-tube direct PCR from whole Drosophila melanogaster adults. Trends Genet. 1996;12:457. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)99992-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon N, Trimborn T, Strouboulis J, Fraser P, Grosveld F. The effect of distance on long-range chromatin interactions. Mol Cell. 1997;1:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsett D. The suppressor of Hairy-wing protein and long distance enhancer-promoter interactions. Mol Cells. 1996;6:381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Emami KH, Jain A, Smale ST. Mechanism of synergy between TATA and initiator: Synergistic binding of TFIID following a putative TFIIA-induced isomerization. Genes & Dev. 1997;11:3007–3019. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gdula DA, Gerasimova TI, Corces VG. Genetic and molecular analysis of the gypsy chromatin insulator of Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:9378–9383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer PK. The role of insulator elements in defining domains of gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer PK, Spana C, Corces VG. On the molecular mechanism of gypsy-induced mutations at the yellow locus of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1986;5:2657–2662. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer PK, Green MM, Corces VG. Tissue-specific transcriptional enhancers may act in trans on the gene located in the homologous chromosome: The molecular basis of transvection in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1990;9:2247–2256. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsborough AS, Kornberg TB. Reduction of transcription by homologue asynapsis in Drosophila imaginal discs. Nature. 1996;381:807–810. doi: 10.1038/381807a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen SK, Tjian R. TAFs and TFIIA mediate differential utilization of the tandem Adh promoters. Cell. 1995;82:565–575. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson JE, Sakonju S. Cis and trans interactions between the iab regulatory regions and abdominal-A and Abdominal-B in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;139:835–848. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S, Comai L. Trans-sensing effects: The ups and downs of being together. Cell. 1998;93:329–332. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslip TR, Hodgetts RB. Targeted transposition at the vestigial locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1994;138:1127–1135. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman JE, Durbin KJ, Winston F. Genetic evidence for promoter competition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4608–4615. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.11.4608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopmann R, Duncan D, Duncan I. Transvection in the iab-5, 6, 7 region of the bithorax complex of Drosophila: Homology independent interactions in trans. Genetics. 1995;139:815–833. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.2.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen R. Altered gene expression in plants due to trans interactions between homologous genes. Trends Biotech. 1990;8:340–344. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(90)90220-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeler KJ, Dray T, Penney JE, Gloor GB. Gene targeting of a plasmid-borne sequence to a double-strand DNA break in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:522–528. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs JE, Dunaway M. The scs and scs′ insulator elements impart a cis requirement on enhancer-promoter interactions. Mol Cell. 1998;1:301–308. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis EB. The theory and application of a new method of detecting chromosomal rearrangements in Drosophila melanogaster. Am Nat. 1954;88:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- ————— Some aspects of position pseudoallelism. Am Nat. 1955;89:73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Noll M. Compatibility between enhancers and promoters determines the transcriptional specificity of gooseberry and gooseberry neuro in the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 1994;13:400–406. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichten M, Goldman ASH. Meiotic recombination hotspots. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:423–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Zimm GG. The Genome of Drosophila melanogaster. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Laborda A, González-Reyes A, Morata G. Trans regulation in the Ultrabithorax gene of Drosophila: Alterations in the promoter enhance transvection. EMBO J. 1992;11:3645–3652. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee BD. Pairing sites and the role of chromosome pairing in meiosis and spermatogenesis in male Drosophila. Curr Top Dev Biol. 1998;37:77–115. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60172-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merli C, Bergstrom DE, Cygan JA, Blackman RK. Promoter specificity mediates the independent regulation of neighboring genes. Genes & Dev. 1996;10:1260–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JR, Chen J-l, Geyer PK, Wu C-t. Two modes of transvection: Enhancer action in trans and bypass of a chromatin insulator in cis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1998;95:10740–10745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JR, Chen J-l, Filandrinos ST, Dunn RC, Fisk R, Geyer PK, Wu C-t. An analysis of transvection at the yellow locus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1999;151:633–651. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki S, Levine M, Cai HN. Different core promoters possess distinct regulatory activities in the Drosophila embryo. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:547–556. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KS, Geyer PK. Effects of the su(Hw) insulator protein on the expression of the divergently transcribed Drosophila yolk protein genes. EMBO J. 1995;14:6258–6279. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe J, Nonchev S, Gould A, Whiting J, Krumlauf R. Selectivity, sharing and competitive interactions in the regulation of the Hoxb genes. EMBO J. 1998;17:1788–1798. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipos L, Mihály J, Karch F, Schedl P, Gausz J, Gyurkovics H. Transvection in the Drosophila Abd-B domain: Extensive upstream sequences are involved in anchoring distant cis-regulatory regions to the promoter. Genetics. 1998;149:1031–1050. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilghman SM, Caspary T, Ingram RS. Competitive edge at the imprinted Prader-Willi/Angelman region? Nat Genet. 1998;18:206–208. doi: 10.1038/ng0398-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-t, Howe M. A genetic analysis of the Suppressor 2 of zeste complex of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;140:139–181. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]