Abstract

The late phase of the human papillomavirus (HPV) life cycle is linked to epithelial differentiation, and we investigated the factors that regulate this process. One potential regulator is p63, a member of the p53 family of proteins, which modulates epithelial development, as well as proliferation capability, in stem cells. In this study, we examined the role of p63 in the HPV life cycle using a lentiviral knockdown system for p63. In epithelial cells, the ΔN truncated isoforms of p63 predominate, while the full-length TA isoforms are present at very low levels. Upon the differentiation of normal keratinocytes, p63 levels rapidly decreased while higher levels were retained in HPV-positive cells. Our studies indicate that reducing p63 levels in differentiated HPV-positive cells resulted in the loss of viral genome amplification and late gene expression. p63 regulates the expression of cell cycle regulators, and we determined that cyclin A, cyclin B1, cdk1, and cdc25c were reduced in p63-deficient, HPV-positive keratinocytes, which suggests a possible mechanism of action. In addition, activation of the DNA repair pathway is necessary for genome amplification, and the expression of two members, BRCA2 and RAD51, was altered in the absence of p63 in HPV-positive cells. Our studies indicate that p63 is necessary for the activation of differentiation-dependent HPV late viral functions and provide insights into relevant cellular targets.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small, nonenveloped DNA viruses that infect mucosal and epithelial tissues of the feet, hands, and anogenital tracts (16). Over 120 types of HPVs have been identified, and approximately one-third have a tropism for the genital epithelium (51). These genital HPVs are further divided into high-risk and low-risk types based on their ability to progress toward malignancy, and high-risk HPVs are the causative agents of cervical and other anogenital cancers (9, 24, 50). The HPV life cycle is intimately associated with the differentiation program of epithelial cells (33). HPVs gain access to cells in the basal layer of the epithelium that become exposed through microabrasions (22, 37). Following entry, the viral genome is maintained as episomes in the nucleus at approximately 50 to 100 copies per cell (15, 16, 29). As HPV-infected basal cells divide and one of the daughter cells begins to differentiate, the late promoter is activated, resulting in the onset of the productive phase of the life cycle, which includes viral DNA amplification and late gene expression (13, 20). The signals that control the induction of these late viral events are not well understood, but infected cells that exit the basal layer need to remain active in the cell cycle to reenter S phase or G2/M in order to activate late functions (5). Furthermore, E6, E7, E1̂E4, and E5 are needed for the activation of late viral events (11, 12, 41, 44), even though their mechanisms of action are, for the most part, unknown. Studies have shown that a primary function of E7 was its ability to bind to Rb family members and that this was important for blocking cell cycle exit in differentiating cells (6, 12, 29).

One HPV protein known to be important for controlling aspects of the viral life cycle is E6, which is, along with E7, able to efficiently immortalize human keratinocytes (14). A major target of the high-risk E6 proteins is p53, which is sequestered into a complex with E6 and E6AP, resulting in its ubiquitin-mediated degradation (17–19). This inhibits the activation of a stress response and allows cells to continue to be active in the cell cycle. Recently, two other family members of the p53 family of proteins have been identified (21, 46). Several studies have shown that p63 and p73 function similarly in regulating differentiation and developmental events, but p63 was more important in the skin and epithelia while p73 was vital in neurons (32, 36, 43, 47, 48). All three p53 family members share the same basic structural arrangement, consisting of a transactivation domain (TA), a DNA-binding domain (DBD), and an oligomerization domain (10). While the degree of homology between these domains varies, the region within the DBD of p53 that directly binds and activates p53-responsive promoters is identical to that found in p63 and p73 (10). This suggests that p63 and p73 are able to bind and activate p53-responsive genes and influence cellular events, including cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (26, 43). Both p63 and p73 utilize two different promoters, as well as alternative splicing, to yield several different protein isoforms, with 6 forms identified for p63 and at least 20 for p73 (7, 8, 46). The full-length TA isoforms behave similarly to p53 in terms of activation of cellular transcription. Alternative promoter usage generates the ΔN isoforms, which are still transactivation competent but target a more restricted set of genes than the TA isoforms (10). In epithelial cells, ΔNp63 is by far the most prominent isoform expressed (23, 35, 42), while TAp63 is found at very low levels (25).

Cellular microRNAs (miRNAs) are important regulators of gene expression and act posttranscriptionally by binding to the consensus sequences within the 3′ untranslated regions of target transcripts (2). These miRNA-mRNA complexes are then cleaved by the RNA-induced silencing complex, resulting in target gene silencing. This process is quite complex, in that a single miRNA can target up to 200 genes in one or more pathways and a target mRNA can be regulated by more than one miRNA (2). Previous studies have shown that HPVs do not encode their own viral miRNAs (3). However, recent work has demonstrated that HPVs suppress a skin-specific cellular miRNA, miR-203, in order to facilitate the viral life cycle and that this activity was mediated by the viral proteins E6 and E7 (30, 31). Furthermore, studies have shown that one of the many cellular targets of miR-203 is p63 (30, 31). In this study, we investigated specifically what role, if any, p63 plays in facilitating the HPV life cycle. We demonstrated that while the levels of p63 normally decreased upon epithelial differentiation, larger amounts are retained in HPV-positive cells than in normal human keratinocytes. Furthermore, we show that knockdown of p63 resulted in a loss of differentiation-dependent HPV late gene expression and genome amplification, thus identifying a major cellular regulator of the HPV life cycle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Normal human foreskin keratinocytes (NHKs) were isolated from neonatal human foreskin tissue as described previously (39) and maintained in keratinocyte growth medium with supplements (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). CIN612 is a biopsy specimen-derived cell line that stably maintains HPV type 31 episomes. CIN612 cells were grown in coculture with J2 3T3 fibroblast feeders treated with mitomycin C (MEDAC GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) in serum-containing medium (E medium) supplemented with 5 ng/ml mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). 293T human embryonic kidney cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (Thermo Fisher, Asheville, NC), 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Prior to harvesting of protein, DNA, or RNA, CIN612 cells were treated with Versene (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] containing 0.5 mM EDTA) for 2 min and then washed twice with PBS to remove the J2 3T3 fibroblast feeders.

Differentiation of keratinocytes in semisolid medium.

To induce differentiation, NHKs and CIN612 cells were suspended in 1.5% methylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as previously described (45). Dry autoclaved methylcellulose was combined with E medium (no EGF added) and supplemented with 0.05% fetal bovine serum (FBS). J2 3T3 fibroblasts were removed from cell cultures using Versene, 3 × 106 cells were suspended in 25 ml methylcellulose that was placed in a petri dish, and cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 and 48 h. Following incubation, the methylcellulose was removed by four washes with ice-cold PBS and each half of the resulting cell pellet was harvested for either total DNA and protein or total RNA and protein as described below.

Lentiviral constructs.

MISSION short hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral vectors (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were used to achieve transient p63 knockdown in CIN612 cells. Five p63-specific shRNA constructs in a pLKO.1 plasmid backbone (named constructs sh2, sh3, sh4, sh5, and sh6), a “nontarget” construct (scram), and an HIV-green fluorescent protein (HIVGFP) construct were utilized individually to transfect 293T cells in order to produce lentiviral particles. The scram construct contained an shRNA sequence that did not include any known human gene and acted as a negative control. The HIVGFP construct was used to assess transduction efficiency.

Lentiviral particle production and transduction.

293T cells were grown to 40 to 50% confluence in 10-cm tissue culture dishes and transfected with 5 μg shRNA plasmid DNA, 1.66 μg vesicular stomatitis virus G plasmid DNA, and 3.37 μg Gag-Pol-Tet-Rev plasmid DNA using polyethyleneimine (Polysciences, Warrington, PA). Twenty-four hours posttransfection, the culture medium was changed and the cells were grown for an additional 48 h (3 days total). Medium was collected and filter sterilized using 0.45-μm syringe filters (Pall, Ann Arbor, MI). Approximately 7.5 × 105 CIN612 cells were incubated with 5 ml viral supernatant consisting of p63 shRNA or scram shRNA control lentiviral particles in the presence of 4 μg/ml hexadimethrine bromide (Polybrene; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 72 h at 37°C. Twenty-four hours posttransduction, fresh E medium was placed in each plate of transduced CIN612 cells and p63 knockdown was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Determination of transduction efficiency.

Approximately 2 × 106 CIN612 cells were transduced with reporter HIVGFP-pLKO lentiviral particles for 24 h. Following a medium change, the cells were allowed to grow for an additional 48 h prior to harvesting. J2 fibroblasts were then removed, and the transduced cells were trypsinized and counted. One million cells were isolated and washed with PBS and stored in PBS with 2% FBS. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells was determined to be approximately 80%. Untransduced CIN612 cells were used as a negative control (0.85% GFP+).

Western blot analysis.

Following the removal of J2 fibroblasts, whole-cell extracts were isolated by resuspension of cell pellets in 100 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mM Tris base [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors [cOmplete Mini; Roche, Indianapolis, IN]). Samples were incubated on ice for 15 min and then centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 16,100 × g). Supernatants were recovered and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were quantified using the NanoDrop ND2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Asheville, NC). Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Hayward, CA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in a solution of 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and then incubated with one of the following primary antibodies (with dilutions noted in parentheses): anti-cyclin A (1:2,000), anti-cyclin E (1:1,000), anti-cdk2 (1:1,000), anti-transglutaminase (TGM2; 1:1,000), anti-Brca2 (1:500), anti-Chk2 (1:750), anti-pChk2 Thr68 (1:750) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), anti-GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (1:4,000), anti-p63 4A4 clone (1:700), anti-involucrin (1:1,000), anti-K10 (1:1,000), anti-filaggrin (1:500) (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-Rad50 (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX), and anti-Rad51 (Millipore, Hayward, CA). The secondary antibodies utilized were horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA). Enhanced chemiluminescence was used to visualize the proteins (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA).

Southern and Northern blot analyses.

CIN612 (wild-type, scram, and p63 knockdown) cells were treated with Versene to remove J2 3T3 fibroblasts. Cells grown in monolayer and methylcellulose were collected and lysed in Southern lysis buffer (400 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA) and then incubated at room temperature with 50 μg/ml RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 50 μg/ml proteinase K (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 37°C to remove residual RNA and proteins. Total DNA was then isolated and extracted by phenol-chloroform extraction, and Southern analysis was carried out as described previously (11). For Northern blot analysis, cells were isolated as described above and total RNA was isolated from cells grown in monolayer or methylcellulose by use of the RNA STAT-60 reagent (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Northern blot analysis was then carried out as outlined previously (11).

RESULTS

shRNA against p63 decreases p63 expression in HPV-positive cells.

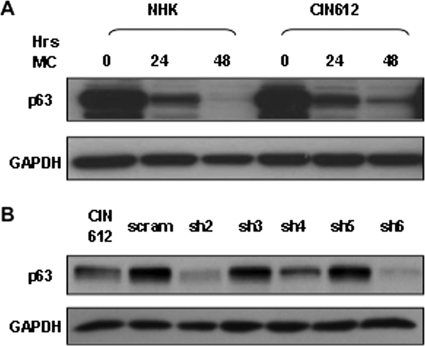

To determine if p63 performs any significant function during the differentiation-dependent HPV life cycle, we examined the effects of knocking down p63 levels in cells that stably maintain HPV type 31 episomes by using a series of lentiviruses expressing p63-specific shRNAs. We first examined the levels of p63 in NHKs and compared them with the levels seen in HPV type 31-containing CIN612 cells. Consistent with previous reports (30, 31), we observed levels of p63 in HPV-positive cells that were similar or slightly elevated compared to those in NHKs grown in monolayer culture (Fig. 1A). The induction of late viral functions, such as activation of the late viral promoter and genome amplification, is dependent upon keratinocyte differentiation; therefore, we examined the levels of p63 upon differentiation induced by the suspension of keratinocytes in 1.5% methylcellulose. In NHKs, the levels of p63 rapidly decreased upon differentiation and were barely detectable after 48 h in methylcellulose (30, 31). Similarly, the levels of p63 in CIN612 cells also decreased upon differentiation but remained higher than those seen in NHKs (Fig. 1A). This is consistent with previous reports that, upon differentiation, p63 is retained at higher levels in HPV-positive cells than in NHKs (30, 31). The primary isoform of p63 detected in keratinocytes is ΔNp63, as opposed to the TA isoform, which is found at very low levels, and this was observed in other studies (23, 25, 31, 35).

Fig. 1.

Levels of p63 proteins are decreased following infection of CIN 612 cells with p63-specific shRNA lentiviruses. (A) Western blot analysis of p63 in undifferentiated (0 h methylcellulose [MC]) or differentiated (24 and 48 h MC) NHKs and HPV-positive CIN612 cells. Band volumes for GAPDH and p63 blots were analyzed using ImageLab (Bio-Rad) software and normalized to GAPDH loading. Following differentiation for 48 h in MC, p63 levels in CIN612 cells were approximately 2.3-fold higher than in NHK cells at the same time point. (B) Undifferentiated CIN612 cells either left uninfected or infected with lentiviruses expressing p63-specific (sh2 to sh6) or nontarget (scram) shRNAs. GAPDH was included as a loading control. A GFP control lentivirus infection indicated that >80% of the cells were infected.

We next investigated what role, if any, p63 plays in HPV pathogenesis. For these studies, we obtained a series of lentiviral vectors expressing shRNAs targeted against p63. To verify the efficacy of these p63-specific shRNAs, we used Western blot analyses to examine the levels of p63 proteins in monolayer cultures of CIN612 cells that were transduced with p63-specific shRNA-expressing lentiviruses (Fig. 1B). Cell extracts were harvested 72 h after transduction and examined by Western blot analyses for p63 protein levels. A GFP-expressing lentivirus control transduction (HIVGFP) indicated that using this methodology allowed the successful transduction of >80% of the cells via the recombinant lentiviral system. Two of the five p63-specific shRNAs, sh2 and sh6, were found to reduce the levels of p63 in monolayer CIN612 cells. We also observed greatly reduced p63 expression levels upon the differentiation of CIN612 cells transduced with sh2- and sh6-expressing lentiviruses following suspension in methylcellulose (not shown). No such reductions were observed with cells that were transduced with nontarget shRNA (scram)- or HIVGFP shRNA-expressing lentivirus. In addition, no appreciable difference in p63 levels was observed between the control transductions and untransduced CIN612 cells. For the remainder of these studies, we utilized sh2- and sh6-expressing lentiviruses to examine the effects of reduced p63 levels on the HPV life cycle.

We subsequently examined if the growth of CIN612 cells was altered by the introduction of these lentiviruses expressing p63-specific shRNAs. For these studies, undifferentiated cells were transduced with p63 shRNA-, scram shRNA-, and HIVGFP shRNA-expressing lentiviruses and cells were counted at 3 and 5 days posttransduction (Fig. 2). We observed that the growth of lentivirus-transduced CIN612 cells was comparable to that of normal CIN612 cells (Fig. 2). These results illustrate that CIN612 cells transduced with p63 shRNA-expressing lentiviruses exhibit reduced p63 expression levels, but the loss of p63 on a short-term basis does not inhibit normal cell growth. We also transduced HPV-positive cells with the sh2 and sh6 lentiviruses, selected for transduced cells, and expanded cultures; however, we did not observe any reductions in p63 levels due to the expression of these recombinant lentiviruses (data not shown). This suggests that there may be a selection against long-term reductions in p63 levels.

Fig. 2.

Reduction of p63 levels does not inhibit cell growth. CIN612 cells were infected with a lentivirus expressing a p63-specific (sh2 or sh6) or a nontarget (scram) shRNA. Total cells were counted at 3 and 5 days postinfection and plotted as millions of cells.

Viral transcripts are decreased in p63 knockdown CIN612 cells.

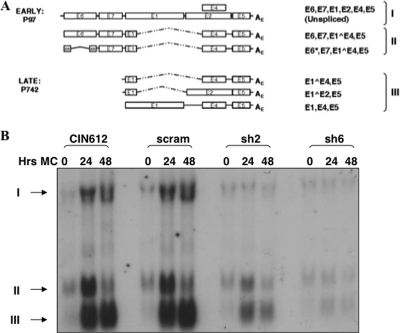

It was next important to determine if reduced p63 levels have any effects on either early or late viral gene transcription. For these analyses, normal CIN612 cells or CIN612 cells transduced with p63 shRNA- or scram shRNA-expressing lentivirus were grown in monolayer or suspended in 1.5% methylcellulose for 24 and 48 h to induce differentiation. At each time point, cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated and screened by Northern blot analysis for the levels of HPV late messages. As shown in Fig. 3, we observed minimal differences in early mRNAs expressed in undifferentiated cells (0-h time point). In contrast, cells in which p63 levels were reduced exhibited a corresponding decrease in late viral gene transcription upon differentiation (Fig. 3). These findings indicate that p63 is required for the production of late viral transcripts upon differentiation.

Fig. 3.

Loss of p63 results in reduced differentiation-dependent late gene expression. (A) Schematic representation of HPV transcripts initiating from early (p97) and late (p742) promoters. Transcripts are marked I, II, and III and correspond to the arrows in panel B. Northern blot analysis of RNA extracted from CIN612 cells left uninfected or infected with a scram shRNA- or p63 shRNA-expressing lentivirus and differentiated for 24 and 48 h in methylcellulose (MC). Transcripts are labeled in groups I, II, and III as described for panel A.

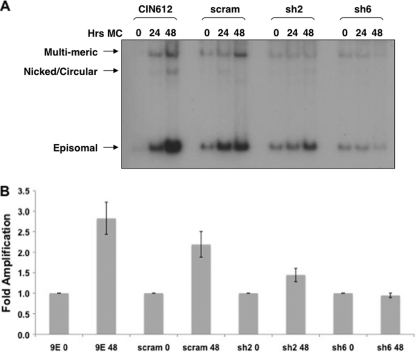

Amplification of viral genomes is impaired in p63 knockdown CIN612 cells.

A second late viral function that is dependent upon differentiation is genome amplification. Therefore, we next examined if this late activity was impaired when p63 levels were reduced. For these studies, CIN612 cells were transduced with p63 shRNA- or scram shRNA-expressing lentivirus and then grown in monolayer or suspended in 1.5% methylcellulose for 24 or 48 h to induce differentiation. Cells were harvested at each time point, and DNA was extracted and screened by Southern blot analysis for viral genome amplification. We observed a minimal effect on the genome copy number in undifferentiated cells, which is similar to what was observed for early viral transcripts (Fig. 4). Conversely, upon differentiation, we detected an impaired ability to amplify viral genomes in cells with reduced levels of p63 (Fig. 4). No such effects were seen in cells transduced with control lentiviruses expressing scram shRNAs. This experiment was performed four times, and the results are plotted in Fig. 4B. We conclude that retention of p63 upon differentiation is important for both activation of late gene expression and genome amplification.

Fig. 4.

p63 knockdown of CIN612 cells results in loss of differentiation-dependent viral genome amplification. (A) CIN612 cells left uninfected or infected with a scram shRNA- or p63 shRNA-expressing lentivirus. DNA was isolated from undifferentiated cells at 72 h postinfection (0 h) or after differentiation in methylcellulose (MC) for an additional 24 or 48 h and analyzed by Southern blotting for the presence of episomal HPV DNA. Arrows indicate the forms of HPV DNA that were visualized. (B) Graphic representation of results of four experiments. Band densities were determined using ImageLab (Bio-Rad), and the graph was assembled using Microsoft Excel software.

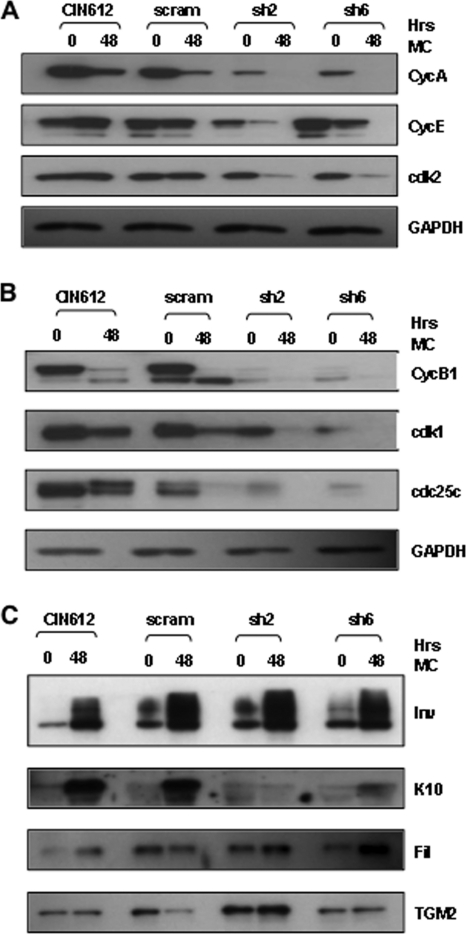

Levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins are altered in p63 knockdown CIN612 cells.

p63 could act in a number of ways to regulate HPV late functions. The first way it could act is to directly bind to viral sequences and activate the late promoter, but we found no consensus p63 binding sites in HPV type 31. p63 has also been implicated as a factor important in maintaining a stem cell nature in cells (“stemness”), and this could be manifested in differentiating human epithelia in several ways (49). One way p63 could act to maintain stemness is to facilitate cell cycle competence in differentiating cells. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed the levels of cell cycle regulatory proteins in differentiated HPV-positive cells and compared them with the amounts seen in cells in which p63 levels had been reduced with p63 shRNAs. As shown in Fig. 5A, cyclin A is maintained at high levels following the differentiation of control CIN612 cells and these levels are decreased when p63 levels are reduced. Cyclin E levels were also maintained at high levels in HPV-positive cells upon differentiation; however, only minimal changes in levels were seen when p63 was reduced. We believe that the modest differences in cyclin E levels observed in sh2- and sh6-transduced CIN612 cells are due to experimental variation. Similarly, no change was observed in the levels of cdk2 in undifferentiated cells, though levels were reduced upon differentiation (Fig. 5A). Additionally cdk1, cdc25c, cdk2, and cyclin B1 levels were reduced in both undifferentiated and differentiated HPV-positive cells in which p63 levels were knocked down (Fig. 5B). Overall, it seems that cyclin A and B1, cdk1, and cdc25c levels in differentiated HPV-positive cells are highly sensitive to the presence of p63.

Fig. 5.

Loss of p63 affects the expression levels of cell cycle proteins but not involucrin, TGM2, or filaggrin. (A, B, and C) Total cell proteins were harvested from uninfected CIN612 cells and CIN612 cells infected with a virus expressing scram shRNA or p63 shRNA after 0 and 48 h in methylcellulose (MC). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blot analysis for factors indicated by each lane. Blots were probed for p63 first and then stripped and reprobed for the various other factors indicated. GAPDH was included as a loading control. CycA, cyclin A; CycB1, cyclin B1; CycE, cyclin E; Inv, involucrin; Fil, filaggrin; TGM2, transglutaminase.

Another way p63 could act to interfere with HPV late functions is by modulating differentiation. We therefore examined the levels of involucrin, TGM2, and filaggrin induced following differentiation and found minimal differences between CIN612 cells that retained p63 and those that had reduced levels of p63 (Fig. 5C). In contrast, the levels of K10 decreased when p63 levels were reduced (Fig. 5C). We conclude that reductions in p63 levels interfered with the expression of some, but not all, markers of differentiation. Our previous studies indicated that amplification closely correlated with involucrin and TGM2 expression and not K-10 (39).

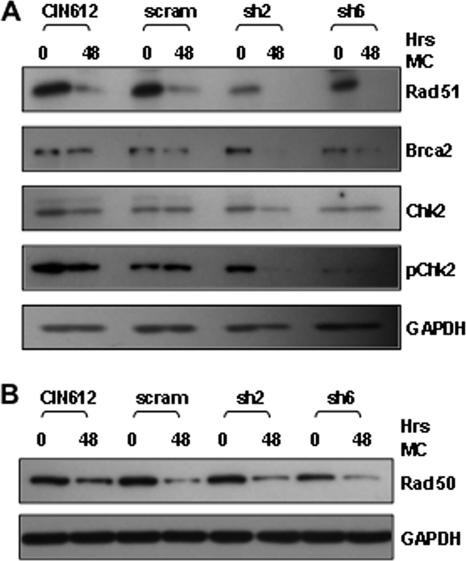

Reduction of p63 levels in CIN612 cells alters the expression levels of DNA repair proteins.

Activation of the DNA damage response is important for the differentiation-dependent genome amplification of human papillomaviruses (34), and p63 has recently been shown to be a transcriptional activator of several members of the DNA damage response (28). The ΔNp63 isoform has been reported to specifically transactivate RAD51 and BRCA2. We therefore examined how the levels of DNA repair proteins varied in HPV-positive cells in which p63 levels were reduced by shRNAs. As shown in Fig. 6, the levels of BRCA2 were reduced in CIN612 cells expressing shRNAs against p63 after 48 h in methylcellulose, while no change was seen in the levels of the RAD50 and total chk2 proteins (Fig. 6), which are also members of the DNA damage pathway. In addition, RAD51 levels were decreased upon the differentiation of p63-deficient CIN612 cells compared to those in untransduced HPV-positive cells (Fig. 6A). Finally, the levels of the active phosphorylated form of CHK2 were reduced after 48 h in methylcellulose in cells lacking p63 (Fig. 6A). Previous studies indicated that inhibition of CHK2 phosphorylation blocks HPV genome amplification upon differentiation (34), and our observations suggest that retention of p63 in differentiating HPV-positive keratinocytes is important for activation of DNA damage response. We conclude that retention of p63 upon differentiation of HPV-positive cells is important for activities necessary for the late phase of the viral life cycle, including cell cycle control, the expression of differentiation markers, and the activation of DNA repair proteins.

Fig. 6.

Loss of p63 affects the expression levels of DNA damage response proteins. (A and B) Total cell proteins were harvested from uninfected CIN612 cells and CIN612 cells infected with a virus expressing scram shRNA or p63 shRNA after 0 and 48 h in methylcellulose (MC). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Western blot analysis for the factors indicated. Blots were probed, stripped, and reprobed for the various other factors indicated. GAPDH was included as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that the expression of p63 upon differentiation is necessary for activation of HPV late functions, such as induction of the late promoter and genome amplification. During normal keratinocyte differentiation, p63 levels rapidly decrease to barely detectable levels. Although p63 levels also decrease upon differentiation in HPV-positive cells, the p63 levels are retained at higher levels than in normal keratinocytes. In lentivirus-transduced, HPV-positive cells in which p63 expression levels were reduced by shRNAs, differentiation-dependent late transcripts, as well as genome amplification, were reduced. Previous studies have shown that activation of the differentiation-dependent late promoter is not necessarily dependent upon genome amplification and can occur at low levels in its absence (1, 40). This indicates that the retention of p63 is needed for the activation of HPV late viral functions. Our studies identify a novel role for p63 in regulating both differentiation-dependent viral genome amplification and late gene expression.

Six isoforms of p63 have been identified, and all have distinct biological roles, some of which may be antagonistic to one another (10). The major p63 isoform in keratinocytes is ΔNp63, which is consistent with our studies (31). On the other hand, the TAp63 isoform is expressed at very low levels in keratinocytes. The ΔN isoform is expressed from its own promoter and lacks the TA domain; however, it retains the ability to transactivate downstream effectors similarly to TAp63 (10). Previous studies have shown that ΔNp63 is responsible for maintaining the proliferative potential of basal epithelial cells, while TAp63 acts synergistically with ΔNp63 to facilitate epithelial differentiation (27, 43, 49). Additionally, TAp63 plays a central role in maintaining genetic stability in oocytes (26). The shRNA constructs utilized in our studies are targeted to regions present in all p63 isoforms, and although ΔNp63 is the most prominent isoform present in keratinocytes, it is possible that other p63 isoforms may also contribute to the reductions in late gene expression and viral DNA amplification despite their low levels of expression. Overall, our studies demonstrate that p63 is necessary for activation of late functions, and it is possible that more than one isoform is responsible.

Downregulation of p63 in regenerating human epidermis has been reported to result in severe tissue developmental defects and the inhibition of stratification and differentiation (4). Interestingly, knocking down of p53 and p63 concurrently appears to rescue the developmental, as well as the proliferation, defects of p63 alone, but not the inhibition of differentiation (43). In HPV-positive cells, where E6 targets p53 for degradation, we observed no change in short-term proliferation effects in p63 knockdown cells similar to those seen in double knockdowns (17, 19). While transient knockdown of p63 did not affect the growth of cells, we were unable to isolate stable cell lines in which p63 levels were reduced. This suggests that long-term loss of p63 may be selected against, which is in contrast to the loss of p53 in cells that are not restricted in growth ability.

p63 also controls differentiation, and in our studies we observed that loss of p63 resulted in minimal changes in the levels of involucrin, TGM2, and filaggrin. In contrast, loss of p63 resulted in reduced levels of keratin 10, suggesting that there is a reduction in the expression of some, but not all, markers of differentiation. Our previous studies indicated that HPV genome amplification upon differentiation correlated with the expression of involucrin and TGM2 but not K-10 (39). While we cannot exclude the possibility that loss of the expression of some markers of differentiation has an effect on amplification, we believe that other activities targeted by p63 provide more significant effects. An alternate explanation for why retention of p63 is essential for late viral functions is a role in maintaining cell cycle competence in differentiating cells (38). HPV late functions are activated in differentiating keratinocytes that are arrested in late S phase or G2/M, and our studies show that the loss of p63 in differentiating HPV-positive cells correlates with reductions in cyclins A and B1, which restrict the ability to enter S and G2/M. Both TAp63 and ΔNp63 can regulate the expression of genes involved in cell cycle regulation, and so their loss would affect the ability of HPV-positive cells to reenter S or G2, preventing the activation of late viral functions. Interestingly, p63 seems to have different effects on some cell cycle proteins, such as cyclin B1 and cdk1, in undifferentiated cells, while the expression of others is more specifically decreased upon differentiation. One possible explanation is that p63 has different activities in undifferentiated and differentiated cells, and this needs to be investigated in more detail.

Additional transcriptional targets of ΔNp63 have recently been reported to include DNA damage response genes such as BRCA2 and RAD51 (28). We previously demonstrated that the activation of the DNA damage response is important for genome amplification upon differentiation (34), and we now observe that the loss of p63 in differentiating HPV-positive cells results in the altered expression of two members of this pathway. Reduction of p63 levels in differentiating HPV-positive cells was found to result in decreased levels of BRCA2. In addition, knockdown of p63 in differentiating HPV-positive cells also resulted in decreased levels of RAD51. Both RAD51 and BRCA2 are involved in regulating double-strand break repair, but it is still unclear if and how they could contribute to HPV amplification. Using inhibitors, it was demonstrated previously that blocking of CHK2 action resulted in impaired genome amplification. In our study, we observed that CHK2 phosphorylation was inhibited in differentiating HPV-positive cells that expressed shRNAs to p63. It is not clear if prevention of CHK2 phosphorylation is due to loss of RAD51 or BRCA2 or whether some other, as-yet-unidentified, activity of p63 is responsible. Understanding how and why the DNA damage response contributes to differentiation-dependent HPV genome amplification is an important area for future study.

Previous studies in our laboratory showed that the HPV E6 and E7 proteins suppress the expression of a skin-specific cellular miRNA, miR-203, in differentiating keratinocytes and that this is important for the amplification of the viral DNA upon differentiation (30, 31). As mentioned previously, miRNAs often target multiple genes, with some miRNAs having as many as 200 targets (2). The p63 isoforms are likely only a small set of the miR-203 target genes, and it is possible that other targets of miR-203 are equally important for HPV pathogenesis. Our studies demonstrate that p63 is one important target of this miRNA and that it is essential in differentiating cells for HPV pathogenesis. miRNAs usually target cellular pathways, and the additional targets of miR-203 are not yet identified, but we believe they may also play essential roles in the viral life cycle. Since the expression of a single gene product can be regulated by multiple miRNAs, it will be important to identify the additional regulating miRNAs and targets in the future in order to understand how the complex interplay between these individual components contributes to the regulation of the HPV life cycle.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cary Moody, Jason Bodily, and members of the Laimins laboratory for their insightful comments and discussions.

This work was supported by a grant to L.A.L. from the National Cancer Institute (R37CA074202). K.K.M. was supported by a grant from the NCI (R37CA074202-13S2).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 29 June 2011.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bodily J. M., Meyers C. 2005. Genetic analysis of the human papillomavirus type 31 differentiation-dependent late promoter. J. Virol. 79:3309–3321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bostjancic E., Glavac D. 2008. Importance of microRNAs in skin morphogenesis and diseases. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Panonica Adriat. 17:95–102 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cai X., Li G., Laimins L. A., Cullen B. R. 2006. Human papillomavirus genotype 31 does not express detectable microRNA levels during latent or productive virus replication. J. Virol. 80:10890–10893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Candi E., et al. 2006. Differential roles of p63 isoforms in epidermal development: selective genetic complementation in p63 null mice. Cell Death Differ. 13:1037–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cheng S., Schmidt-Grimminger D. C., Murant T., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. 1995. Differentiation-dependent up-regulation of the human papillomavirus E7 gene reactivates cellular DNA replication in suprabasal differentiated keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 9:2335–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collins A. S., Nakahara T., Do A., Lambert P. F. 2005. Interactions with pocket proteins contribute to the role of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 in the papillomavirus life cycle. J. Virol. 79:14769–14780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. De Laurenzi V., et al. 1998. Two new p73 splice variants, gamma and delta, with different transcriptional activity. J. Exp. Med. 188:1763–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Laurenzi V. D., et al. 1999. Additional complexity in p73: induction by mitogens in lymphoid cells and identification of two new splicing variants epsilon and zeta. Cell Death Differ. 6:389–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. de Villiers E. M. 1994. Human pathogenic papillomavirus types: an update. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 186:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dötsch V., Bernassola F., Coutandin D., Candi E., Melino G. 2010. p63 and p73, the ancestors of p53. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a004887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fehrmann F., Klumpp D. J., Laimins L. A. 2003. Human papillomavirus type 31 E5 protein supports cell cycle progression and activates late viral functions upon epithelial differentiation. J. Virol. 77:2819–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flores E. R., Allen-Hoffmann B. L., Lee D., Lambert P. F. 2000. The human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncogene is required for the productive stage of the viral life cycle. J. Virol. 74:6622–6631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grassmann K., Rapp B., Maschek H., Petry K. U., Iftner T. 1996. Identification of a differentiation-inducible promoter in the E7 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) in raft cultures of a new cell line containing high copy numbers of episomal HPV-16 DNA. J. Virol. 70:2339–2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hawley-Nelson P., Vousden K. H., Hubbert N. L., Lowy D. R., Schiller J. T. 1989. HPV16 E6 and E7 proteins cooperate to immortalize human foreskin keratinocytes. EMBO J. 8:3905–3910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hebner C. M., Laimins L. A. 2006. Human papillomaviruses: basic mechanisms of pathogenesis and oncogenicity. Rev. Med. Virol. 16:83–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Howley P. M., Lowy D. R. 2007. Papillomaviruses, vol. 1 Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hubbert N. L., Sedman S. A., Schiller J. T. 1992. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 increases the degradation rate of p53 in human keratinocytes. J. Virol. 66:6237–6241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huibregtse J. M., Scheffner M., Howley P. M. 1991. A cellular protein mediates association of p53 with the E6 oncoprotein of human papillomavirus types 16 or 18. EMBO J. 10:4129–4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huibregtse J. M., Scheffner M., Howley P. M. 1993. Cloning and expression of the cDNA for E6-AP, a protein that mediates the interaction of the human papillomavirus E6 oncoprotein with p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:775–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hummel M., Hudson J. B., Laimins L. A. 1992. Differentiation-induced and constitutive transcription of human papillomavirus type 31b in cell lines containing viral episomes. J. Virol. 66:6070–6080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaghad M., et al. 1997. Monoallelically expressed gene related to p53 at 1p36, a region frequently deleted in neuroblastoma and other human cancers. Cell 90:809–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kines R. C., Thompson C. D., Lowy D. R., Schiller J. T., Day P. M. 2009. The initial steps leading to papillomavirus infection occur on the basement membrane prior to cell surface binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:20458–20463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koster M. I., et al. 2004. p63 is the molecular switch for initiation of an epithelial stratification program. Genes Dev. 18:126–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Laimins L. A. 1993. The biology of human papillomaviruses: from warts to cancer. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:74–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laurikkala J., et al. 2006. p63 regulates multiple signalling pathways required for ectodermal organogenesis and differentiation. Development 133:1553–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee H., Kimelman D. 2002. A dominant-negative form of p63 is required for epidermal proliferation in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2:607–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lena A. M., et al. 2008. miR-203 represses ‘stemness’ by repressing DeltaNp63. Cell Death Differ. 15:1187–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin Y. L., et al. 2009. p63 and p73 transcriptionally regulate genes involved in DNA repair. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 29. Longworth M. S., Laimins L. A. 2004. Pathogenesis of human papillomaviruses in differentiating epithelia. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68:362–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McKenna D. J., McDade S. S., Patel D., McCance D. J. 2010. MicroRNA 203 expression in keratinocytes is dependent on regulation of p53 levels by E6. J. Virol. 84:10644–10652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Melar-New M., Laimins L. A. 2010. Human papillomaviruses modulate expression of microRNA 203 upon epithelial differentiation to control levels of p63 proteins. J. Virol. 84:5212–5221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mills A. A., et al. 1999. p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398:708–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moody C. A., Laimins L. A. 2010. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. 10:550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moody C. A., Laimins L. A. 2009. Human papillomaviruses activate the ATM DNA damage pathway for viral genome amplification upon differentiation. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nylander K., et al. 2002. Differential expression of p63 isoforms in normal tissues and neoplastic cells. J. Pathol. 198:417–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pozniak C. D., et al. 2000. An anti-apoptotic role for the p53 family member, p73, during developmental neuron death. Science 289:304–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roberts J. N., et al. 2007. Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan. Nat. Med. 13:857–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruesch M. N., Laimins L. A. 1998. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins alter differentiation-dependent cell cycle exit on suspension in semisolid medium. Virology 250:19–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ruesch M. N., Stubenrauch F., Laimins L. A. 1998. Activation of papillomavirus late gene transcription and genome amplification upon differentiation in semisolid medium is coincident with expression of involucrin and transglutaminase but not keratin-10. J. Virol. 72:5016–5024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Spink K. M., Laimins L. A. 2005. Induction of the human papillomavirus type 31 late promoter requires differentiation but not DNA amplification. J. Virol. 79:4918–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas J. T., Hubert W. G., Ruesch M. N., Laimins L. A. 1999. Human papillomavirus type 31 oncoproteins E6 and E7 are required for the maintenance of episomes during the viral life cycle in normal human keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:8449–8454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thurfjell N., et al. 2004. Complex p63 mRNA isoform expression patterns in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Int. J. Oncol. 25:27–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Truong A. B., Kretz M., Ridky T. W., Kimmel R., Khavari P. A. 2006. p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes Dev.. 20:3185–3197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilson R., Fehrmann F., Laimins L. A. 2005. Role of the E1-E4 protein in the differentiation-dependent life cycle of human papillomavirus type 31. J. Virol. 79:6732–6740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilson R., Laimins L. A. 2005. Differentiation of HPV-containing cells using organotypic “raft” culture or methylcellulose. Methods Mol. Med. 119:157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang A., et al. 1998. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol. Cell 2:305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang A., et al. 1999. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398:714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yang A., et al. 2000. p73-deficient mice have neurological, pheromonal and inflammatory defects but lack spontaneous tumours. Nature 404:99–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yi R., Poy M. N., Stoffel M., Fuchs E. 2008. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature 452:225–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. zur Hausen H. 1996. Papillomavirus infections—a major cause of human cancers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1288:F55–F78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. zur Hausen H. 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat. Rev. 2:342–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]