Background: Lytic enzymes (lysins) from bacteriophages are potential bactericidal agents.

Results: Positive net charge on lysin catalytic domains is a major factor in determining lytic activity and host range.

Conclusion: Lysins can be engineered to modify their dependence on their cell wall targeting domains.

Significance: This work suggests a number of approaches for fine-tuning lysins as novel antibiotics.

Keywords: Antibiotics, Bacteria, Bacteriophage, Cell Wall, Crystal Structure, Drug Design, Metalloprotease, Pathogen-associated Molecular Pattern, Proteoglycan Structure, Proteolytic Enzymes

Abstract

The recombinant lysins of lytic phages, when applied externally to Gram-positive bacteria, can be efficient bactericidal agents, typically retaining high specificity. Their development as novel antibacterial agents offers many potential advantages over conventional antibiotics. Protein engineering could exploit this potential further by generating novel lysins fit for distinct target populations and environments. However, access to the peptidoglycan layer is controlled by a variety of secondary cell wall polymers, chemical modifications, and (in some cases) S-layers and capsules. Classical lysins require a cell wall-binding domain (CBD) that targets the catalytic domain to the peptidoglycan layer via binding to a secondary cell wall polymer component. The cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria generally have a negative charge, and we noticed a correlation between (positive) charge on the catalytic domain and bacteriolytic activity in the absence of the CBD (nonclassical behavior). We investigated a physical basis for this correlation by comparing the structures and activities of pairs of lysins where the lytic activity of one of each pair was CBD-independent. We found that by engineering a reversal of sign of the net charge of the catalytic domain, we could either eliminate or create CBD dependence. We also provide evidence that the S-layer of Bacillus anthracis acts as a molecular sieve that is chiefly size-dependent, favoring catalytic domains over full-length lysins. Our work suggests a number of facile approaches for fine-tuning lysin activity, either to enhance or reduce specificity/host range and/or bactericidal potential, as required.

Introduction

The outer envelopes of Gram-positive bacteria consist of a lipid bilayer and an ∼200–800-Å thick peptidoglycan (PG)3 cell wall as core elements (1). The outer membrane layer has a high content of phospholipid, making it negatively charged, in contrast to most host (eukaryotic) membranes. The PG layer includes a network of linear glycan chains, polymers of the disaccharide N-acetylmuramic acid-(β1–4)-N-acetylglucosamine (MurNAc-GlcNAc), which are cross-linked by short peptides (“muropeptides”) that bind covalently to the MurNAc moieties and to each other. The glycan chain adopts a helical structure, allowing the formation of a thick three-dimensional mesh (2). This mesh acts in part as a “molecular sieve,” with a pore size estimated at ∼20 Å (3), allowing small secreted enzymes and toxins in the 20–30-kDa range to diffuse freely (4). The negative charge on the lipid and SCWP layers makes many Gram-positive bacteria susceptible to the action of small cationic antimicrobial peptides that rapidly transit through the PG layer and disrupt the lipid bilayer (5).

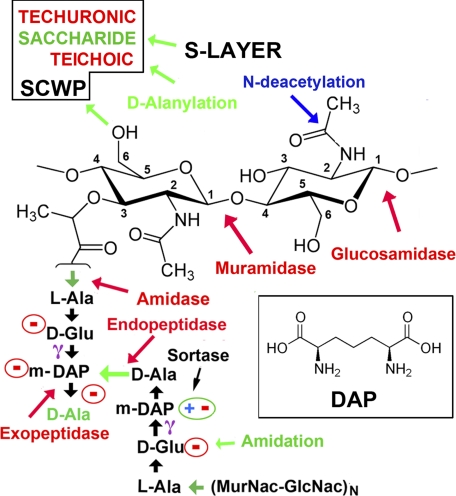

There are two major classes of PG, which differ in the nature of the muropeptides and the peptide cross-links (1). In most bacteria of the family Bacillaceae and most Gram-negative bacteria, including Escherichia coli, the cross-links are formed by a direct peptide bond between diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and d-Ala on apposing peptides (“type A1γ”), although in the second major class, type A3α, Lys replaces DAP and forms a cross-peptide link, typically mediated by a third peptide (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the PG type A1γ cross-link. Two (MurNAc-GlcNAc)N glycan chains are cross-linked by a pair of tetrapeptides, l-Ala-d-Glu-(meso-DAP)-d-Ala. The carboxyl group on a MurNac moiety forms an amide bond with the α-amino group of l-Ala. This bond is the target of amidase lysins. d-Glu uses its γ-carboxyl to makes an amide bond with m-DAP (structure of DAP in inset), leaving its α-carboxylate free. In the A1γ class, the bi-functional m-DAP makes a cross-peptide bond to the terminal d-Ala from the other peptide. The terminal noncross-linked d-Ala is often removed by a carboxypeptidase. In the other major class of PG, a lysine residue replaces DAP, and the transpeptide bond is formed via the side-chain Nζ (although this is typically not direct). Free charges are circled, giving a potential net charge of Z = −4 for the muropeptide bridge. However, species- and strain-specific modifications are common; typically one (not both) of the free acids (d-Ala or m-DAP) is enzymatically amidated. N-Deacetylation of either MurNac or GlcNAC would create a free amino group (positively charged) on the glycan. The cleavage positions of other common lysins are indicated (in red). SCWPs are typically attached via the C-6 hydroxyl group on MurNac. In B. anthracis, the S-layer attaches via the SCWP (16). Sortases may covalently link a number of proteins to the free carboxylate on DAP or other peptides in the muropeptide linkage.

Gram-positive bacteria also display species- and strain-specific “secondary cell wall polymers” (SCWPs) that insert into or attach to the lipid bilayer and/or PG layer (Fig. 1). These SCWPs dramatically alter the appearance and charge of the outer envelope. They include cell wall-anchored teichoic or techuronic acids that decorate the surfaces of many Gram-positive bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis (6). The Bacillus cereus group (including Bacillus anthracis and Bacillus thuringiensis) utilize (uncharged) branched polysaccharides rather than cell wall teichoic acid, but they also display membrane-anchored lipoteichoic acids that extend through the PG layer (7, 8). They may also be further modified by the sortase-mediated covalent linkage of proteins (such as pili and other adhesins) to the muropeptide linkages (9, 10).

Pathogenic bacteria have, not surprisingly, devised many ways to modify their cell wall structure to avoid host defenses. B. subtilis, for example, modifies its membrane phospholipid headgroups (11). In B. anthracis and the closely related B. cereus RSVF1, N-deacetylation of the N-acetyl moieties of both MurNAc and GlcNAc moieties provides resistance to human lysozyme (12). Other common modifications designed to reduce the negative charge are amidation of free carboxylate groups on the muropeptide (1), and d-alanylation of teichoic and lipoteichoic acids (13–15).

Two further protective layers are often observed. The “S-layer” forms a quasi-crystalline protective protein sheath that assembles around the PG layer of some Gram-positive bacteria, generally attached to a cell wall decoration (16–18), although other bacteria synthesize a polysaccharide “capsule” that forms a protective outer shell. B. anthracis is unusual in synthesizing both the S-layer and capsule and constructing its capsule from poly-d-glutamic acid rather than polysaccharide (8).

Phages are viruses that infect bacteria (19–21). They have coevolved with their hosts such that they infect with high specificity and efficiency (22–24). During the final stage of infection, “lytic” phages express a number of enzymes known as endolysins (or simply “lysins”), which are transported from the cytoplasm through the outer membrane via phage-encoded holins (25). Typical lysins have a mass of 25–40 kDa and include an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal CBD (26).

Most lysins cleave either the glycosidic bonds between the sugar moieties (endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase or N-acetylmuramidase; the “lysozymes”) or the glycan-peptide linkage (N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (or “amidases”)) or sometimes the peptide-peptide linkage (Fig. 1). PG cleavage leads to rapid cell lysis, due in part to the high internal turgor pressure maintained by Gram-positive bacteria (27).

Crystal structures of full-length lysins have been determined in a few cases (e.g. the amidase from the Listeria monocytogenes phage PSA (28); a cellobiohydrolase from Trichoderma reesi (29, 30); and a lysin from the pneumococcal phage, Cpl-1, with fragments of receptor and PG bound (24, 31)). The nature of the interdomain linkers varies suggesting different degrees of freedom, but in all cases the structures are consistent with the notion that CBD binding to a species-/strain-specific SCWP positions the catalytic domain for efficient cleavage of PG cross-links.

Recombinant lysins applied externally can be effective bactericidal agents, often retaining high specificity against their natural host (32–35), causing minimal disruption of commensal flora (36) and no evidence for escape mutations (37). The rapid high affinity actions of lysins may also minimize the effects of primary antibody responses (38, 39). Moreover, lysins are effective on mucous membranes and other surfaces such as skin (40, 41), which are major routes of infection/reservoirs for pathogens and where most conventional antibiotics are ineffective (42). Indeed, this is the milieu in which two members of the host “amidase-like” PG recognition immunity proteins operate (see below) (43).

For “classical” lysins, specificity and bacteriolytic activity require the strong binding (typically in the 2–100 nm range (44–46)) of the CBD to its cognate SCWP. The assumption here is that the catalytic domain has an inherently low affinity for the PG layer, and it is only an effective lytic agent when brought into close apposition with its target by its CBD. For example, the B. anthracis phage lysin, PlyB, is a highly effective killer of its host when applied exogenously as a full-length molecule, but a recombinant protein comprising only the catalytic domain showed no detectable lytic activity (i.e. CBD-dependent) (47).

However, we previously described a lysin, PlyL, derived from a B. anthracis prophage, for which the recombinant catalytic domain showed a high level of lytic activity (i.e. CBD-independent; a “nonclassical” lysin). It also displayed an increased host range compared with the full-length lysin (48).

Phage lysins are closely related to bacterial “autolysins,” which are required for PG remodeling during growth and cell division (22, 49), as well as to a small family of mammalian proteins (four in humans), termed PG recognition protein (PGRPs; also called PGLYRPs), which bind to the PG layer of whole cells. They impart a variety of direct and indirect immune responses that complement host recognition of cell wall fragments (43, 49–51).

The PGRPs also adopt an amidase fold, but three of the four human PGRPs lack Zn2+-coordinating residues and are catalytically inactive. Nevertheless, they engage PG on bacterial cell walls in an analogous fashion to E. coli autolysin, as judged by crystallographic studies with PG-muropeptide fragments (24, 52–55). These studies demonstrate a rather broad “footprint” for the lysin/PGRP on the PG layer; and a structural rationale for discriminating between the major types of PG cross-links has been proposed (43, 53). Affinities (Kd values) for the PG layer have been estimated in the 10 nm range (56), similar to the values obtained for CBDs.

The factors accounting for the specificity and bactericidal activity of lysins (when applied externally) would thus appear to be rather complex, arising from the nature of the SCWP, the class of PG, as well as post-assembly modifications to both of these and to the lipid bilayer. One unifying feature, however, is the “continuum of negative charge” (57) created by the cell wall elements.

So why is the CBD sometimes critical for activity and at other times dispensable or even inhibitory? Previous studies on human host immunity proteins such as lysozyme and group IIa-secreted phospholipase A2 offer a clue. These studies point to the importance of positive charge for either hydrolyzing or penetrating the PG layer. Thus, both proteins are small single domain enzymes (∼14 kDa) with very high positive charges (Z = +8 and +15, respectively) (58, 59). Beers et al. (60) found that five charge-reversal mutations (Z = +15 → Z = +5) reduced the activity of group IIa-secreted phospholipase A2 to <1% of wild-type levels; and they also concluded that loss-of-function was due to an overall reduction in charge rather than any specific effect. Moreover, a Staphylococcus aureus strain deficient in cell wall teichoic acid showed increased resistance to group IIa-secreted phospholipase A2 (61), raising the possibility that electrostatic interactions facilitate both localization at the bacterial surface (via long range effects such as electrostatic steering (62)) and passage through the cell wall (63).

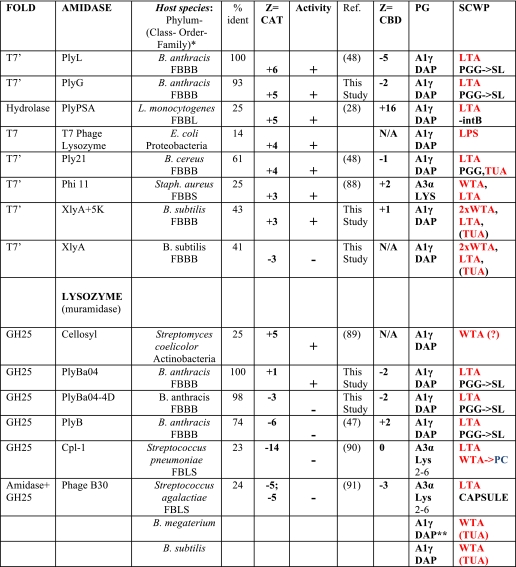

From reviewing the literature, we noted a correlation between net (positive) charge on the catalytic domain of lysin and its bactericidal activity in the absence of the CBD (Table 1) (88–91), even though the absolute values were in general much smaller than those of the host immunity proteins. By contrast, the charges on the CBDs were typically small, often opposite in sign to the catalytic domain, and showed no obvious correlation with lytic activity.

TABLE 1.

Net charge (Z) and lytic activity (±) of phage lysins in the absence of their CBD

* Species of the Firmicute phylum are classified as follows: FBBB, Firmicutes (phylum), Bacilli (class), Bacillales (order), and Bacillaceae (family); FBLS, Firmicutes (phylum), Bacilli (class). Lactobacillales (order), and Streptococcaceae (family); FBBL, Firmicutes (phylum), Bacilli (class), and Bacillales (order), and Listeriaceae (family). % identities are with respect to PlyL (amidases) and PlyBa04 (glycosyl hydrolases), catalytic domains only. PC, phosphatidylcholine; LTA, lipoteichoic acid; PGG, PG glycopolymer (uncharged); WTA, wall teichoic acid; SL, S-layer; TUA, techuronic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; intB, internalin B. B. megaterium and B. subtilis have A1γ (DAP) PG and WTA as their major SCWP but express techuronic acid in minimal phosphate media (as does B. subtilis).

** indicates not amidated on DAP. SCWP in red typeface is negatively charged.

To determine whether the catalytic domain charge/activity correlation had a physical basis, we compared the structures and activities of two pairs of lysins (an amidase pair and a lysozyme pair) with homologous catalytic domains, but which exhibited either classical or nonclassical bacteriolytic behavior. Using structure-based engineering, we switched the sign of the net charge on one of each pair of catalytic domains and found that we could convert a CBD-dependent catalytic domain to CBD independence and vice versa. Although net charge may be only one of many factors defining lytic activity and specificity, our observations suggest a facile approach for fine-tuning lysin activity, either for enhancing or reducing specificity/host range and/or lytic activity as required. These findings may find application in the development of novel therapeutics and detectors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning and Mutagenesis

The primers used for cloning (see supplemental Table 1) were designed based on the NCBI data base sequences of XlyA (accession ID CAB13138) and PlyBa04 (accession ID NP_843024). The B. subtilis 168 (ATCC 27370) and DNA extract of B. anthracis strain Ames (provided by Dr Philip Hanna, University of Michigan Medical School) were used as the templates for PCR. An internal NdeI site within the gene of PlyBa04 was removed with a silence mutation. The amplified DNA product was double-digested using NdeI and BamHI and ligated into a pET15b vector (Novagen) before transforming into XL1-BLUE (Stratagene). The correct ligation construct was selected by restriction digest and confirmed by sequence analysis. QuikChange (Stratagene) and Multiple QuikChange (Stratagene) were used for single and multiple mutagenesis of the lysin genes, following the manufacturer's protocols.

The gene for PlyG was synthesized (GenScript Corp.) using the sequence recorded in NCBI accession number ABB55421, codon-optimized for expression in BL21DE3, with NdeI and BamHI added at the 5′ and 3′ ends. The N-terminal catalytic domain, 1–160, was obtained by PCR (supplemental Table 1). Both full-length and catalytic domain constructs were ligated into pET15b vectors.

Protein Expression and Purification

Wild-type and mutants lysins were expressed in E. coli BL21DE3 cells. Freshly transformed cells (CaCl2 method) were grown in LB at 37 °C to a density of A600 = 1.0. Protein expression was induced by 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and proceeded overnight at 15 °C. For XlyA and its mutants, cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C and resuspended in a buffer containing 300 mm NaCl and 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.0. Cells were lysed by sonication and clarified by centrifugation for 1 h at 4 °C, before loading onto a 5-ml Ni(II)-charged HITRAP chelating column (GE Healthcare), and washed with 50 ml of column buffer containing 30 mm imidazole. The His-tagged protein was eluted using 0.3 m imidazole. The His tag was cleaved using thrombin (Sigma) (1 unit per mg of protein) at 4 °C for 16 h. Superdex S200 (GE Healthcare) gel filtration was used to further purify the protein. The final buffer for crystallization trials of XlyACAT and XlyACAT+5K was 20 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, and 100 mm NaCl. The first three vector-derived residues, Gly-Ser-His, remain in the final protein construct. Similar purification protocols were used for PlyBa04 and PlyG, except that the lysis/column buffer consists of 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm MES titrated to pH 6.5 with NaOH. The final buffer for crystallization trials was 20 mm MES, pH 6.5, and 100 mm NaCl. In all cases, purified proteins were concentrated to 20 mg/ml, and the quality was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-MS analysis. The catalytic mutant, PlyL (E90A), was purified as described previously (48).

Crystallization

All crystals in this study were obtained using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion technique by mixing 2 μl of protein with 1 μl of crystallization liquor prior to equilibration. PlyBa04CAT crystals grew from 25% PEG-4000, 200 mm NaCl, 100 mm sodium acetate at pH 4.5. XlyACAT crystals grew from 40% PEG-400, 0.1 m MES, pH 6.2. The charge mutant, XlyA+5KCAT, grew from 20% (w/v) PEG-8000, 0.1 m Tris-HCl, pH 7.5.

X-ray Data Collection

XlyACAT (wild-type and mutant) crystals were soaked in crystallization buffer + 10% glycerol for a few seconds before freezing in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data for wild-type were collected at the Berkeley Advanced Light Source (Beamline 12.3.1) using a single crystal at 100 K at two wavelengths (peak and remote) at the zinc absorption edge (Table 1). Mutant data were collected at 100 K using an in-house Rigaku FRE high brilliance x-Ray generator (λ = CuKα) and an R-axis IV detector. For PlyBa04CAT, a mercury derivative was obtained by soaking in 5 mm methyl-mercuric nitrate/crystallization buffer for 2 h at 20 °C. In both cases, crystals were flash-frozen in their crystallization liquor, and data were collected on our in-house setup. A mutant with four of the five residues mutated to lysine XlyA+4KCAT behaved similarly.

Structure Determination

Synchrotron data were integrated and scaled with DENZO and SCALEPACK (64). In-house data were processed with MOSFLM (65) and SCALA (66). Heavy atom sites were determined for XlyACAT and PlyBa04CAT and phases determined and refined and initial models built using SOLVE and RESOLVE (67). Rebuilding and refinement were performed using O (68), Coot (69), CNS (70), and REFMAC (71). Initial phases for the XlyACAT mutant, which adopted a different space group from wild type, were determined by molecular replacement in MOLREP (72). Electrostatic potentials were calculated using the PDB2PQR server and APBS program within PyMOL (73).

Bacillus Lysis Experiments

Live cell lysis experiments were performed as described previously (48). Briefly, cell cultures were grown to mid-exponential phase, harvested, and resuspended in 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0. Purified lysins were added to a final concentration of 0.4 mm, and lysis was monitored using a Beckman Coulter DTX880 multimode detector (reduction in light scattering at 600 nm). Experiments were performed in triplicate in 96-well plates. The strains used were B. anthracis 34F2 Stern strain, B. cereus ATCC 4342, Bacillus megaterium WH320 and B. subtilis 168. Net charge (Z) at pH 7.5 was simply estimated as the difference between the number of (Lys + Arg) minus the number of (Asp + Glu) residues. The zinc ion counted as +2 (or +1 if one of its protein-coordinating ligands was deprotonated by the presence of metal, e.g. Cys). Histidine residues were not considered, although their pKa values will tend to increase in an acidic milieu, favoring protonation.

Cell Wall Binding Experiments

Bacillus cells were grown to A600 = 1, centrifuged, and washed once using PBS. Purified His-tagged CBDs of PlyL or PlyG were added to Bacillus cell pellets. Suspensions were incubated on ice for 5 min before washing three times with PBS. Pellets were resuspended using SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane for Western blot analysis using anti-His antibody (Qiagen).

Quantitative CBD Cell Binding Assay

B. cereus ATCC 4342 and B. subtilis 168 were grown under identical conditions to mid-exponential phase, harvested, and resuspended in PBS. His-tagged CBD was diluted into PBS before adding to cells, which were rocked at room temperature for 1 h, then pelleted in a table centrifuge (at 14,000 rpm), and washed three times with PBS. An equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE loading buffer was added to the final mixture and boiled for 1 min at 100 °C. SDS-PAGE was performed using the Invitrogen Tris-Gly 4–20% minigel and then Western-blotted onto a Immobilon transfer membrane (Millipore) using the Invitrogen XCell IITM blot module according to the manufacturer's instructions. The membrane was blocked overnight with 2% milk powder in TBS (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 4 °C. The penta-His antibody (Qiagen) and the goat HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Calbiochem) were the primary and secondary antibodies, with five TBS washes between addition of antibodies. The substrate, Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescent (Pierce), was added before exposure to a Kodak Biomax film. The image was scanned and analyzed using ImageJ 1.35 (rsb.info.nih.gov/). Band intensity was plotted and fitted in Kaleidagraph using the equation: fraction bound = [L]/([L] + Kd). No significant binding was observed with B. subtilis.

RESULTS

Homologous Lysin Catalytic Domains Show Disparate Bactericidal Activity

Table 1 lists published data on lysins where the “external” bactericidal (lytic) activity has been assayed for both full-length proteins and their catalytic domains. The correlation between net charge on the catalytic domains and bactericidal activity in the absence of their CBDs includes two distinct classes of lysins, the amidases (two different folds) and the lysozymes (muramidase class GH25), and extends to phages that infect distinct phyla: Proteobacteria (e.g. E. coli), Actinobacteria, and Firmicutes (class bacilli). We found that the E. coli autolysin, AmiD, human lysozyme, and the PGRPs also followed this rule. We therefore set out to test by structure-based mutagenesis the hypothesis that net charge, per se, was a significant contributor to the lytic activity of the catalytic domain.

We previously showed that the catalytic domain of the lysin, PlyL (an amidase from the B. anthracis λ Ba02 prophage), “PlyLCAT” displayed high lytic activity and a broader host range than the full-length protein (48). Such nonclassical behavior has been observed previously (47, 74) but rarely to such a dramatic extent. PlyLCAT carries a net charge of Z = +6 at pH 7.5.

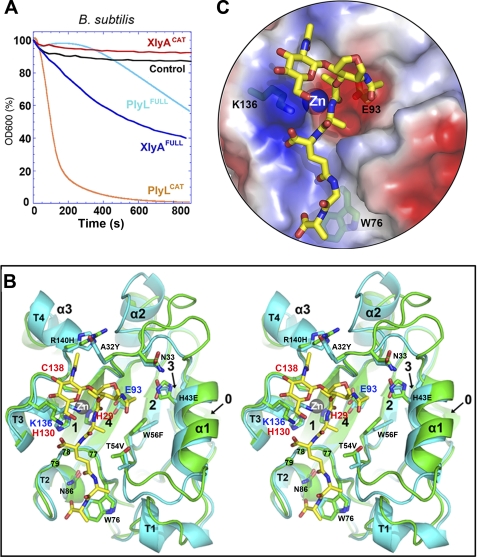

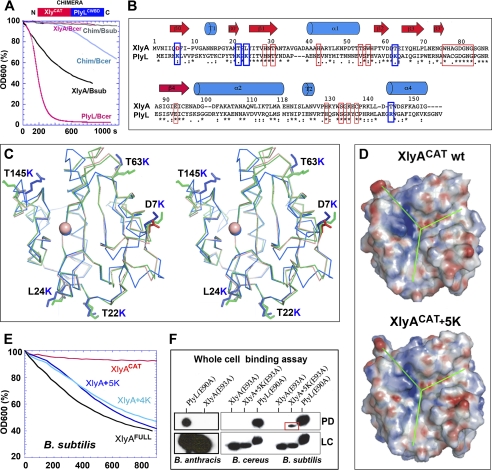

We therefore sought a homologous lysin bearing a net negative charge. The catalytic domain from XlyA (from a B. subtilis prophage (75)) has 45% identity with PlyL and a net charge of Z = −3 at pH 7.5. We expressed and purified both full-length protein (XlyAFULL) and catalytic domain (XlyACAT), and we tested their ability to lyse their natural host, B. subtilis (Fig. 2A). As expected, XlyAFULL lysed efficiently, although XlyACAT had no effect, consistent with its negative net charge. We also found that PlyLFULL had a modest lytic activity, although PlyLCAT was a highly effective killer against this non-native target.

FIGURE 2.

Similar structures and distinct behaviors of two homologous amidase lysins, PlyL and XlyA. A, bactericidal activities against B. subtilis of full-length lysins and catalytic domains, as determined by decrease in light scattering of cells in suspension with time (see “Experimental Procedures”). Control is addition of no enzyme. B, stereo overlay of XlyACAT (cyan) and PlyLCAT (green), shown as schematics, with secondary structure elements labeled as in Fig. 3A. Selected protein side chains are shown as sticks (carbon atoms are cyan or green; others are colored by atom type). Residues in the 77–79 loop are shown as balls. A glycan-muropeptide is also modeled into the active site (carbon atoms are yellow). C, semitransparent surface representation, same view as B, showing fit of the muropeptide to the active site, and the locations of the key catalytic machinery (Lys-136, Zn2+, and Glu-93), as well as Trp-76, which may play a role in PG selectivity (53).

Structures and Catalytic Machinery of XlyACAT and PlyLCAT Are Very Similar

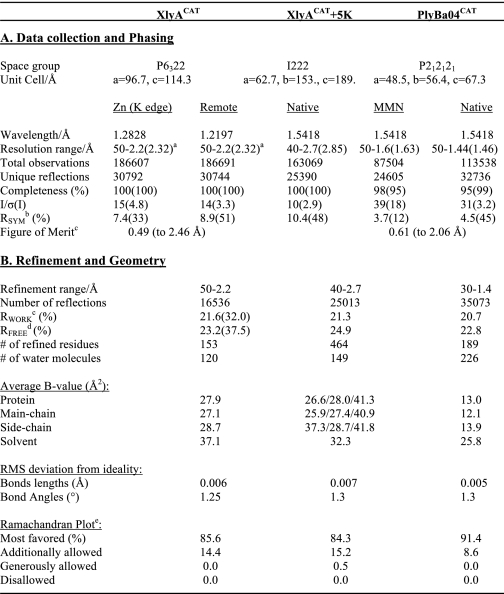

If net charge is a critical determinant of lytic activity, then we must demonstrate that the catalytic machinery is otherwise similar for the two enzymes. We therefore determined the crystal structure of XlyLCAT at 2.2 Å resolution (see “Experimental Procedures” and Table 2) and compared it with that of PlyLCAT (48).

TABLE 2.

Crystallographic statistics

a Figures in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

b RSYM = Σ|Ih − 〈Ih〉|/ΣIh, where 〈Ih〉 is the average intensity over symmetry equivalent reflection.

c RWORK = Σ|Fobs − Fcalc|/ΣFobs, where the summation is over the data used for refinement.

d RFREE was calculated using 5% of data excluded from refinement (92).

e Data were calculated using PROCHECK (93).

As expected, the overall backbones are very similar, with a root mean square difference (on Cα) of 0.7 Å (Fig. 2B). The fold consists of a central β-sheet sandwiched by α-helices and elaborate loops, which define, on the “front” face of the sheet, a pocket housing the active site. The catalytic center includes a zinc ion (coordinated by 2 His and 1 Cys residues). A fragment of PG-muropeptide has been modeled onto the domains based on crystal structures of complexes with a host PGRP and an E. coli autolysin (54), pointing to a strong conservation of the active sites and broader recognition pockets.

There are no steric clashes with the modeled muropeptide in either case, and the overlay places the Zn2+ ion within 3 Å of the scissile bond. Of particular note, the conserved glycine-rich β3′-β4 loop (residues 76–83; stabilized by the conserved Asn-86) defines, together with the conserved Trp-76 side chain, the binding groove for the four amide/peptide bonds of the muropeptide (Fig. 2, B and C). The conserved Lys-136 in XlyA may act both as general acid in the hydrolysis reaction as well as stabilize the α-carboxylate group of d-Glu at position 2 of the muropeptide. The conserved Glu-93 is positioned appropriately to act as general base. Although there are some differences at the back right of the substrate-binding pocket (presumably contact sites for the extended glycan chain), they are mostly conservative (e.g. W56F).

The general base (Glu-93) is in the same position as Glu-90 in PlyL, which places it in a subclass of N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidases that includes Ply21, PlyG, and Phi105 (48), and is related to but distinct from a broader class of enzymes that cleaves the same bond (class A1γ) in Gram-negative bacteria (48).

Given this high structural similarity, we tested whether the innate catalytic activity of XlyACAT was similar to that of PlyLCAT by constructing a chimeric lysin, an approach that has been used for other lysins (76). To avoid the added complexity of the S-layer, we used B. cereus (strain ATCC 4342) as a surrogate for B. anthracis, because it has a very similar cell wall but no S-layer (see below). We knew that neither XlyAFULL nor XlyACAT lysed B. cereus, so we fused XlyACAT with the CBD of PlyL (PlyLCBD). As expected, the XlyACAT:PlyLCBD chimera failed to lyse B. subtilis, but it did lyse B. cereus, with an efficiency only 2–3 times less than that of XlyAFULL for its host (B. subtilis) (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Designing a gain-of-function lysin (amidase) catalytic domain, XlyA+5KCAT. A, bactericidal activities of wild-type lysins and a chimera (XlyACAT:PlyLCBD) against B. cereus (Bcer) or B. subtilis (Bsub). B, sequence alignment and secondary structure assignments of XlyACAT and PlyLCAT. Residues involved in catalysis and substrate recognition are boxed in red. Residue pairs in blue boxes indicate sites mutated to lysine in XlyACAT to create XlyACAT+5K. Below the sequences, asterisks indicate identity; and colons indicate close similarity. C, stereo Cα overlay of XlyACAT (pink), Xly A+ 5KCAT (green), and PlyLCAT (cyan). XlyA mutated residues are labeled, and their side chains shown as sticks. Orientation is the same as in Fig. 2B. D, electrostatic surfaces of wild-type XlyACAT and XlyA+5KCAT, viewed as in A, showing that mutations do not affect the active site face. E, bactericidal activities (against B. subtilis) of wild-type and mutant XlyA catalytic domains, compared with full-length enzyme. XlyA+4KCAT is similar to XlyA+5KCAT but has one less residue changed to lysine. F, pulldown (PD) binding assays (Western blots using anti-His tag antibody) using whole cells (B. cereus, B. subtilis, or B. anthracis Sterne) and catalytically inactivated His-tagged mutants of PlyLCAT, XlyACAT, and XlyA5KCAT. LC = loading control. The input protein concentration was 1 μm or (for B. anthracis) 10 μm.

Engineering a Gain-of-Function Lysin Domain

We next asked whether the innate catalytic activity of XlyACAT could be converted into bactericidal activity simply by engineering a positive net charge onto the domain.

By overlaying the crystal structures, we found five residues in XlyACAT (Asp-7, Thr-22, Leu-24, Thr-63, and Thr-145) that were surface-exposed, not close to the catalytic face of the domain, and not playing any other obvious structural roles (Fig. 3, B and C). By mutating all five residues to Lys, we created a mutant, “XlyA+5KCAT”, with a switch in sign of its net charge from −3 to +3. XlyA+5KCAT expressed and folded well, as judged by its thermal denaturation profile and our ability to crystallize and refine its structure at 2.7 Å resolution (Fig. 3C, Table 2, and supplemental Fig. 1). The mutant backbone structure is identical within experimental error (root mean square difference on Cα = 0.36 Å). The mutations alter the electrostatic surface potential on the sides and back of the domain but not on the catalytic face (Fig. 3D).

We found that XlyA+5KCAT lysed B. subtilis cells at a rate nearly identical to that of wild-type XlyAFULL (Fig. 3E). A similar mutant with four of the five sites substituted behaved similarly. However, XlyA+5KCAT showed no activity toward B. cereus (data not shown).

To explore this observation further, we constructed variants of XlyACAT, XlyA+5KCAT, and PlyLCAT that were catalytically inactive but structurally sound by mutation of the active site general base, Glu-93/90, to Gln. We expected these mutants to bind Zn2+ normally with negligible disruption of the active site, so that the enzyme could, in principle, recognize its target bond within the PG layer, but not lyse it (by analogy with the PGRPs). Using pulldown assays with live cells, we found that PlyL(E90A)CAT bound strongly to both B. subtilis and B. cereus (as well as B. anthracis Sterne) without lysing either of them (Fig. 3F). We also observed significant binding of XlyA+5K(E93A)CAT to B. subtilis but not to B. cereus, although XlyA(E93A)CAT bound to neither species.

Engineering a Second Class of Endolysins, Muramidase Lysozymes

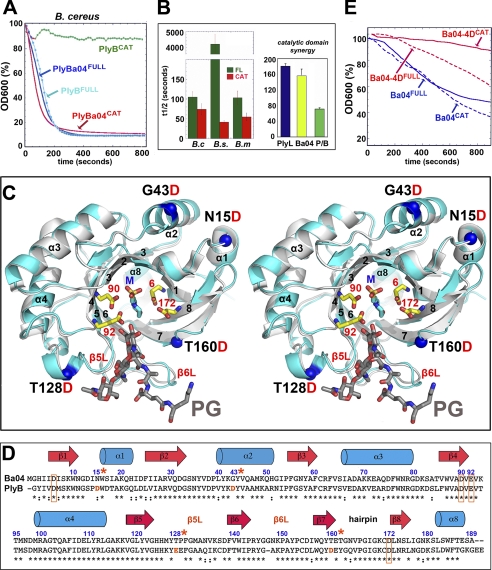

We next explored whether a similar behavior could be engineered into a lysozyme/muramidase that cleaves the β-1,4-glycan linkage between the MurNac and GlcNAC moieties (see Fig. 1). One such full-length lysin, PlyBFULL, efficiently lyses B. cereus ATCC 4342 when applied externally, although PlyBCAT (Z = −6) does not (47). We therefore selected a homologous lysin with a net positive charge; PlyBa04CAT (from the B. anthracis phage, Ba04) is 72% identical but has Z = +1. We expressed both PlyBa04FULL and PlyBa04CAT and tested their lytic activities. We found that PlyBa04CAT lysed B. cereus as efficiently as the full-length lysin (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Engineering a loss-of-function (muramidase/lysozyme) lysin. A, comparison of the lytic activities of full-length and catalytic domains of B. anthracis phage lysozymes, PlyBa04 and PlyB, against B. cereus ATCC 4243. The data for PlyB are derived from Fig. 1 of Porter et al. (47). Enzyme and bacterial concentrations and strains are identical. B, PlyBa04CAT and PlyLCAT have similar host ranges and synergize in killing B. cereus. Left panel, PlyBa04CAT is a highly effective killer of B. cereus, B. megaterium, and B. subtilis (t½ = 50–100 s with 0.8 μm lysin), similar to the behavior of PlyLCAT (and faster than the full-length protein in each case). Right panel, when used in combination, there is a clear synergistic effect between PlyLCAT and PlyBa04CAT against B. cereus. Total lysin concentration is the same in each case (0.4 μm). P/B = 0.2 μm PlyLCAT + 0.2 μm PlyBa04CAT). C, stereo overlay of PlyBa04 (cyan) and PlyB (gray) catalytic domains, with secondary structure elements as in C. The four mutation sites in PlyBa04CAT are indicated. The two pairs of conserved acidic residues at the active site are shown as ball-and-stick (PlyBa04 numbering), as is a molecule of buffer (MES), which lines the center of the site and may be a substrate mimetic. A glycan-muropeptide fragment is modeled based on an overlay with the structure of pneumococcal phage lysin, Cpl-1 (Protein Data Bank code 1H09), in complex with a fragment of PG. E, comparison of lytic activities of PlyBa04 wild-type and mutant lysins against B. cereus in the context of full-length and catalytic domains. D, structure-based sequence alignment and secondary structure assignments of PlyBa04CAT and PlyBCAT, with active residues boxed. Mutations sites are numbered and labeled with *.

We further found that PlyBa04CAT had an extended host range compared with PlyBa04FULL, efficiently killing B. subtilis and B. megaterium (Fig. 4B, left panel). This is very similar behavior to PlyL (48). Moreover, PlyLCAT and PlyBa04CAT displayed synergistic killing (Fig. 4B, right panel) (77).

We determined the crystal structure of PlyBa04CAT at 1.4 Å resolution using heavy atom methods (Fig. 4, C and D, and Table 2). As expected, the structures of PlyBa04CAT and PlyBCAT are very similar (Fig. 4C; root mean square difference = 0.38 Å for 160 Cαs). They are “GH-25” family glycosyl hydrolases, including a central mostly parallel eight-stranded β-barrel, with an α-helix or extended loop connecting each of the seven parallel strands in a simple circular topology. The 7th and 8th strands are connected by a short β-hairpin, creating a final (antiparallel) strand that extends to the bottom of the barrel, where it elaborates a short helix (α8) that seals the base.

Two pairs of acidic residues that are conserved throughout the GH-25 family are required for catalysis (78) and dominate a negatively charged substrate-binding pocket at the top of the barrel. In PlyBa04, these are Asp-90/Glu-92 and Asp-6/Asp-172. A fragment of PG-muropeptide has been modeled onto PlyBa04CAT based on the structure of the pneumococcal phage lysin, Cpl-1 (Fig. 4C) (24). In the broader family of GH-25 domains, loops at the ends of β5 and β6 are the most variable; in the model they cradle both glycan and muropeptide and may thus provide specificity (24).

Having established a strong structural similarity, we proceeded to engineer PlyBa04, using a similar strategy as for the amidases. However, in this case, we chose to build a loss-of-function mutant, by creating a catalytic domain with a net negative charge. We introduced additional Asp residues into PlyBa04, at four positions as follows: Asn-15, Gly-43, Thr-128, and Thr-160 (situated on helices and loops that are not expected to interfere directly with substrate binding or catalysis) resulting in a change in net charge from Z = +1 to Z = −3 (Fig. 4, C and D).

This mutant, “PlyBa04-4DCAT,” expressed well and, as expected, showed little or no lytic activity toward B. cereus (Fig. 4E), very similar to the behavior of PlyBCAT (Fig. 4A). However, we also made the same mutant in the context of the full-length lysin, PlyBa04–4DFULL, and found that a significant portion of wild-type activity was retained.

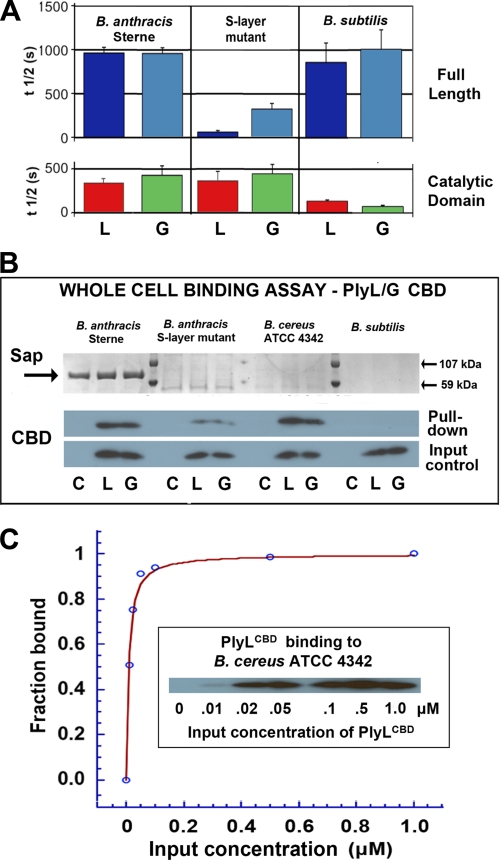

Effect of S-layer

We compared the effects of PlyL and the closely related PlyG (96% identical in the catalytic domain; 63% in the CBD) on the B. anthracis Sterne strain (which makes S-layer but not capsule) and a mutant Sterne lacking a key S-layer gene (sap−). We showed previously that when applied externally, PlyLCAT had a higher lytic activity than PlyLFULL against Sterne (48). We found that PlyG behaved similarly (Fig. 5A); indeed, PlyGCAT killed Sterne more than twice as fast as PlyGFULL.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of the B. anthracis S-layer on lytic activity and whole cell binding by two homologous amidases, PlyL and PlyG. A, cell killing activities of full-length (top) or catalytic domain (bottom) of PlyL (“L”) and PlyG (“G”) against B. anthracis Sterne, B. anthracis (sap−) mutant deficient in S-layer synthesis, and B. subtilis. Lysin concentration was 0.4 μm in each case. B, whole-cell pulldown binding assays using His-tagged CBDs (1 μm) of PlyL (“L”) and PlyG (“G”) and mutant and wild-type B. anthracis, B. cereus 4342 (which has a similar PG/SCWP architecture but does not express an S-layer), and B. subtilis, which serves as a control (it has a different SCWP architecture and does not express an S-layer). Lower gels are Western blots using anti-His antibody (C = cell pellet alone). Upper gels show expression of Sap protein, with markers at 59 and 107 kDa. C, quantitative binding assay for PlyLCBD to live B. cereus cells (see “Experimental Procedures”). The derived Kd = 7.8 ± 0.8 nm; curve-fitting quality parameters are: χ2 = 0.0067; R = 0.996.

Although the lytic activities of PlyLCAT (Z = +6) and PlyGCAT (Z = +5) were unaffected by the absence of the S-layer, both full-length lysins showed enhanced activity in the absence of the S-layer; indeed, the relative activities of the full-length proteins and catalytic domains were reversed (Fig. 5A). In particular, PlyLFULL displayed an extremely high lytic activity (higher even than against B. cereus (48), which lacks an S-layer but has a very similar PG layer). PlyG also behaved like PlyL (48) toward B. subtilis (which has a different SCWP architecture), showing low activity as a full-length protein, although the catalytic domains lysed cells rapidly. We also found that both CBDs behaved similarly; they bound strongly to Sterne and B. cereus, less well to the sap− mutant (and not at all to B. subtilis, as expected) (Fig. 5B). Finally, we quantified the binding of PlyL CBD to B. cereus (Fig. 5C) and obtained a Kd of 8 nm, comparable with values reported for lysins that display a variety of CBD architectures and target distinct cell walls (44–46, 79).

DISCUSSION

Few studies have investigated the role of the catalytic domains in lytic (bactericidal) activity, specificity, and host range. Our findings that a positive net charge is a requirement for lytic activity by the catalytic domain in the absence of its CBD (as well as our demonstration of “gain-of-function” of an inactive negatively charged domain by facile engineering to create a positively charged active mutant) have clear implications for the design of lysins as macromolecular antibiotics.

We assume that the strong binding of the CBD to its cognate receptor is dominant in localizing the catalytic domain to the cell wall in the case where the recombinant catalytic domain is negatively charged and has no detectable affinity/activity toward the PG layer. Once the catalytic domain is positioned close to the PG layer, the local concentration of substrate is greatly enhanced (80), and although the negative charge on the catalytic domain reduces its on-rate, significant catalysis may ensue. The situation is similar for the chimeric lysin that we constructed (XlyACAT:PlyLCBD), where both charge and PG preference reduce but do not eliminate lysis.

Further support for this model comes from our study of PlyBa04, where we successfully converted a positively charged bactericidal catalytic domain into a negatively charged inactive one. But when we expressed the same mutant in the context of the full-length protein (with an authentic CBD), we found that lytic activity was retained, but at a reduced level.

We found that a subset of catalytic domains (PlyLCAT, PlyGCAT, and PLyBa04CAT) show strong lytic activity and broad host range, which correlates with their ability to bind to the surface of both native and non-native hosts. Although we did not quantify the affinity for the PG layer, for PlyLCAT and PlyGCAT it appears comparable with the binding of PlyLCBD to its SCWP, as judged by whole-cell pulldown experiments performed under similar conditions (compare Figs. 3F and 5, B and C). Precedents for high affinity (10–60 nm) binding by amidase domains to the PG layer have been reported in the case of certain PGRPs (52, 56). By comparison, the gain-of-function mutant, XlyACAT+5K, bound significantly less well to its host and not at all to B. cereus, showing that although a positive net charge may be a critical, additional elements contribute to the overall binding affinity/lytic activity.

It is also interesting to consider the influence of the CBD on the lytic activity of these highly active catalytic domains in the context of a non-native host. Although positive charge is necessary for activity and broad host range, we note that the absolute value need not be high; thus, although PlyGCAT and PlyLCAT have net charges of Z = +5 and +6, PlyBa04CAT (Z = +1) showed the highest activity against (both native and) non-native targets.

In the case of full-length lysins targeting non-native hosts, the CBD typically has no affinity for the noncognate bacterial surface, and we found the effect of the CBD on lytic activity to be variable in extent but always inhibitory. We previously proposed that auto-inhibitory interactions between the catalytic domain and the CBD might be responsible for this inhibition (48), but a comparison of the melting temperatures of full-length PlyL and its domains argues against significant interdomain interactions (supplemental Fig. 2).

We therefore suggest the following scenario. When the CBD does not have a cognate target, the determinants of cell wall lysis may be quite different. The very high activity of PlyLCAT and PlyBa04CAT likely arises from an ability of these domains to bind strongly to and cut a path through the thick PG layer, because of strong inherent binding, positive charge, and a size small enough (∼17 kDa) to readily penetrate the PG mesh (3). The addition of a nonbinding CBD would then simply provide unwelcome baggage, making the protein larger (26–30 kDa, close to the PG size cutoff), as well as more negatively charged. However, the extreme contrast we encountered between the lytic activity of PlyBa04 in its full-length and catalytic forms against B. subtilis (but not against B. megaterium) suggests that more specific inhibitory mechanisms (perhaps recognition by the CBD of a noncognate “decoy” SCWP) may operate in some cases (Fig. 4B).

Presumably, PlyLCAT binds tightly to a highly conserved element found on the PG surface of many Bacillus species. The existence of distinct SCWP elements (cell wall teichoic acids) on the outer surfaces of B. subtilis (and B. megaterium, which is also efficiently lysed by PlyLCAT) does not seem to offer significant protection against PlyL.

For those bacteria that do not possess an S-layer or capsule, the observation that most recombinant lysins efficiently and specifically cleave their host when applied externally suggests that the decorated PG layer has a similar appearance/accessibility whether viewed from inside or outside the cell. However, lysins have not evolved to contend with the asymmetric (external) barrier created by the S-layer. Our data suggest that the S-layer in B. anthracis Sterne also acts as a molecular sieve, with a similar size exclusion limit to the PG but lacking the charge requirement. Thus, the S-layer impeded full-length PlyG and PlyL (30 kDa) as judged by their poor lytic activity, but both recombinant catalytic domains (17 kDa; Z = +5 and +6) were highly efficient killers (Fig. 5A); and their CBD domains (13 kDa; Z = −2 and −5) also penetrated and bound with an affinity similar to binding to B. cereus ATCC 4342, which lacks an S-layer (Fig. 5B).

In terms of potential therapeutics, our data suggest that catalytic domain-only variants of lysins may offer advantages in cases where an S-layer exists, because of their smaller size/greater penetrance of the S-layer. We did not test the role of the B. anthracis capsule, but Fischetti and co-workers (81) reported that “the capsulated state of several B. anthracis strains examined indicated that the capsule does not block access of PlyG to the cell wall.”

The correlation between positive charge and lytic activity extends to many genera of bacteria as well as two classes of lysins (amidases and muramidases). Given that the fundamental glycan building blocks are the same for all PGs, the lysozyme lysins are potentially multifunctional. What are the prospects for engineering amidase lysins that show broad lytic activity against both major classes? Our experiments have been restricted to bacteria displaying the common DAP-mediated A1γ PG linkage, although Streptococcus and Staphylococcus utilize the lysine-mediated A3α linkage. Studies on host PGRPs have shed some light in this direction (53). However, there are some differences in the binding modes between lysins and PGRPs (arising for example from a preference by the PGRPs to bind the free ends of glycan strands in many cases). Thus, direct structural information on lysins in complex with more realistic mimetics of the PG “continuum” are likely needed for optimal rational design.

In summary, our results provide a novel avenue for fine-tuning or defining the host range and activity of therapeutic lysins that complement ongoing efforts in protein engineering (82) and domain swapping (83–86). We suggest that refining or increasing the host range of lysins may be achieved in a facile manner by altering the net charge on the catalytic domain. Also, the utility of endolysins as “biologics” may indeed depend upon fine-tuning this balance, as too high a specificity may lead to the emergence or selection of resistant strains, although a lower specificity/increased host range may lead to the destruction of commensal bacteria. In other instances, broadly acting lysins may be preferred (87), and our studies point to novel examples of this class of lysin, which could be used singly or in combination. Finally, our work provides new insights into designing therapeutic lysins to treat bacteria that express S-layers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the Berkeley ALS (beamline 12.3.1) for their help with remote x-ray data collection and Drs. L. Bankston and D. Donovan (United States Department of Agriculture) for their comments and suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI055789 and AI055860 from NIAID. This work was also supported by United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Grant DAMD17-03-2-0038.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3RDR, 3HMB, and 3HMC) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- PG

- peptidoglycan

- SCWP

- secondary cell wall polymer

- CBD

- cell wall-binding domain

- DAP

- diaminopimelic acid

- PGRP

- PG recognition protein

- PGRP

- PG recognition protein

- MurNAc

- N-acetylmuramic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1. Schleifer K. H., Kandler O. (1972) Bacteriol. Rev. 36, 407–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meroueh S. O., Bencze K. Z., Hesek D., Lee M., Fisher J. F., Stemmler T. L., Mobashery S. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4404–4409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Demchick P., Koch A. L. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 768–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lambert P. A. (2002) J. Appl. Microbiol. 92, 46S-54S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oyston P. C., Fox M. A., Richards S. J., Clark G. C. (2009) J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 977–987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bhavsar A. P., Erdman L. K., Schertzer J. W., Brown E. D. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 7865–7873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leoff C., Choudhury B., Saile E., Quinn C. P., Carlson R. W., Kannenberg E. L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29812–29821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fouet A. (2009) Mol. Aspects Med. 30, 374–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ton-That H., Marraffini L. A., Schneewind O. (2004) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1694, 269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scott J. R., Barnett T. C. (2006) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 397–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roy H. (2009) IUBMB Life 61, 940–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Severin A., Tabei K., Tomasz A. (2004) Microb. Drug Resist. 10, 77–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peschel A. (2002) Trends Microbiol. 10, 179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peschel A., Sahl H. G. (2006) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perego M., Glaser P., Minutello A., Strauch M. A., Leopold K., Fischer W. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 15598–15606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kern J., Ryan C., Faull K., Schneewind O. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 401, 757–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Etienne-Toumelin I., Sirard J. C., Duflot E., Mock M., Fouet A. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177, 614–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Claus H., Akça E., Debaerdemaeker T., Evrard C., Declercq J. P., Harris J. R., Schlott B., König H. (2005) Can. J. Microbiol. 51, 731–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Groman N. B., Suzuki G. (1962) J. Bacteriol. 84, 596–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Groman N. B., Suzuki G. (1963) J. Bacteriol. 86, 187–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Young I., Wang I., Roof W. D. (2000) Trends Microbiol. 8, 120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loessner M. J., Maier S. K., Daubek-Puza H., Wendlinger G., Scherer S. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 179, 2845–2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Blackburn N. T., Clarke A. J. (2001) J. Mol. Evol. 52, 78–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pérez-Dorado I., Campillo N. E., Monterroso B., Hesek D., Lee M., Páez J. A., García P., Martínez-Ripoll M., García J. L., Mobashery S., Menéndez M., Hermoso J. A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 24990–24999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Young R., Bläsi U. (1995) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 17, 191–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loessner M. J. (2005) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8, 480–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koch A. L. (2003) Trends Microbiol. 11, 166–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Korndörfer I. P., Danzer J., Schmelcher M., Zimmer M., Skerra A., Loessner M. J. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 364, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Divne C., Ståhlberg J., Reinikainen T., Ruohonen L., Pettersson G., Knowles J. K., Teeri T. T., Jones T. A. (1994) Science 265, 524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Srisodsuk M., Reinikainen T., Penttilä M., Teeri T. T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20756–20761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hermoso J. A., Monterroso B., Albert A., Galán B., Ahrazem O., García P., Martínez-Ripoll M., García J. L., Menéndez M. (2003) Structure 11, 1239–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bernhardt T. G., Wang I. N., Struck D. K., Young R. (2002) Res. Microbiol. 153, 493–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fischetti V. A. (2005) Trends Microbiol. 13, 491–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fischetti V. A. (2010) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 357–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hermoso J. A., García J. L., García P. (2007) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 461–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Witzenrath M., Schmeck B., Doehn J. M., Tschernig T., Zahlten J., Loeffler J. M., Zemlin M., Müller H., Gutbier B., Schütte H., Hippenstiel S., Fischetti V. A., Suttorp N., Rosseau S. (2009) Crit. Care Med. 37, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loeffler J. M., Nelson D., Fischetti V. A. (2001) Science 294, 2170–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loeffler J. M., Djurkovic S., Fischetti V. A. (2003) Infect. Immun. 71, 6199–6204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rashel M., Uchiyama J., Ujihara T., Uehara Y., Kuramoto S., Sugihara S., Yagyu K., Muraoka A., Sugai M., Hiramatsu K., Honke K., Matsuzaki S. (2007) J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1237–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fischetti V. A. (2008) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 393–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pastagia M., Euler C., Chahales P., Fuentes-Duculan J., Krueger J. G., Fischetti V. A. (2011) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 738–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hudson I. R. (1994) J. Hosp. Infect. 27, 81–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guan R., Mariuzza R. A. (2007) Trends Microbiol. 15, 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Loessner M. J., Kramer K., Ebel F., Scherer S. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 44, 335–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Spinelli S., Campanacci V., Blangy S., Moineau S., Tegoni M., Cambillau C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 14256–14262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tremblay D. M., Tegoni M., Spinelli S., Campanacci V., Blangy S., Huyghe C., Desmyter A., Labrie S., Moineau S., Cambillau C. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188, 2400–2410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Porter C. J., Schuch R., Pelzek A. J., Buckle A. M., McGowan S., Wilce M. C., Rossjohn J., Russell R., Nelson D., Fischetti V. A., Whisstock J. C. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 366, 540–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Low L. Y., Yang C., Perego M., Osterman A., Liddington R. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35433–35439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dziarski R., Gupta D. (2010) Innate Immun. 16, 168–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Saha S., Qi J., Wang S., Wang M., Li X., Kim Y. G., Núñez G., Gupta D., Dziarski R. (2009) Cell Host Microbe 5, 137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ting J. P., Lovering R. C., Alnemri E. S., Bertin J., Boss J. M., Davis B. K., Flavell R. A., Girardin S. E., Godzik A., Harton J. A., Hoffman H. M., Hugot J. P., Inohara N., Mackenzie A., Maltais L. J., Nunez G., Ogura Y., Otten L. A., Philpott D., Reed J. C., Reith W., Schreiber S., Steimle V., Ward P. A. (2008) Immunity 28, 285–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kumar S., Roychowdhury A., Ember B., Wang Q., Guan R., Mariuzza R. A., Boons G. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37005–37012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Swaminathan C. P., Brown P. H., Roychowdhury A., Wang Q., Guan R., Silverman N., Goldman W. E., Boons G. J., Mariuzza R. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 684–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guan R., Brown P. H., Swaminathan C. P., Roychowdhury A., Boons G. J., Mariuzza R. A. (2006) Protein Sci. 15, 1199–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kerff F., Petrella S., Mercier F., Sauvage E., Herman R., Pennartz A., Zervosen A., Luxen A., Frère J. M., Joris B., Charlier P. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 397, 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu C., Gelius E., Liu G., Steiner H., Dziarski R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 24490–24499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Neuhaus F. C., Baddiley J. (2003) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 686–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Foreman-Wykert A. K., Weinrauch Y., Elsbach P., Weiss J. (1999) J. Clin. Invest. 103, 715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Buckland A. G., Heeley E. L., Wilton D. C. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1484, 195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beers S. A., Buckland A. G., Koduri R. S., Cho W., Gelb M. H., Wilton D. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1788–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Koprivnjak T., Weidenmaier C., Peschel A., Weiss J. P. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 2169–2176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kozack R. E., d'Mello M. J., Subramaniam S. (1995) Biophys. J. 68, 807–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Buckland A. G., Wilton D. C. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1488, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Leslie A. G. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Evans P. (2006) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Terwilliger T. C. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 374, 22–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jones T. A., Zou J. Y., Cowan S. W., Kjeldgaard M. (1991) Acta Crystallogr. A 47, 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (1997) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 73. DeLano W. L. (2005) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC, South San Francisco, CA [Google Scholar]

- 74. Turner M. S., Hafner L. M., Walsh T., Giffard P. M. (2004) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238, 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Longchamp P. F., Mauël C., Karamata D. (1994) Microbiology 140, 1855–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Díaz E., López R., García J. L. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 8125–8129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Djurkovic S., Loeffler J. M., Fischetti V. A. (2005) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 1225–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sanz J. M., García P., García J. L. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 8495–8499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Briers Y., Schmelcher M., Loessner M. J., Hendrix J., Engelborghs Y., Volckaert G., Lavigne R. (2009) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 383, 187–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. McLaughlin S., Wang J., Gambhir A., Murray D. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31, 151–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schuch R., Nelson D., Fischetti V. A. (2002) Nature 418, 884–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sugahara K., Yokoi K. J., Nakamura Y., Nishino T., Yamakawa A., Taketo A., Kodaira K. (2007) Gene 404, 41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Alcantara E. H., Kim D. H., Do S. I., Lee S. S. (2007) J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40, 539–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Becker S. C., Foster-Frey J., Stodola A. J., Anacker D., Donovan D. M. (2009) Gene 443, 32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. García P., García J. L., García E., Sánchez-Puelles J. M., López R. (1990) Gene 86, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. López R., García E., García P., García J. L. (1997) Microb. Drug Resist. 3, 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Yoong P., Schuch R., Nelson D., Fischetti V. A. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186, 4808–4812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Donovan D. M., Lardeo M., Foster-Frey J. (2006) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 265, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bräu B., Hilgenfeld R., Schlingmann M., Marquardt R., Birr E., Wohlleben W., Aufderheide K., Pühler A. (1991) Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34, 481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sanz J. M., Díaz E., García J. L. (1992) Mol. Microbiol. 6, 921–931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Donovan D. M., Foster-Frey J., Dong S., Rousseau G. M., Moineau S., Pritchard D. G. (2006) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5108–5112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kleywegt G. J., Brünger A. T. (1996) Structure 4, 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.