Abstract

To identify accessible and permissive human cell types for efficient derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), we investigated epigenetic and gene expression signatures of multiple postnatal cell types such as fibroblasts and blood cells. Our analysis suggested that newborn cord blood (CB) and adult peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (MNCs) display unique signatures that are closer to iPSCs and human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) than age-matched fibroblasts to iPSCs/ESCs, thus making blood MNCs an attractive cell choice for the generation of integration-free iPSCs. Using an improved EBNA1/OriP plasmid expressing 5 reprogramming factors, we demonstrated highly efficient reprogramming of briefly cultured blood MNCs. Within 14 days of one-time transfection by one plasmid, up to 1000 iPSC-like colonies per 2 million transfected CB MNCs were generated. The efficiency of deriving iPSCs from adult PB MNCs was approximately 50-fold lower, but could be enhanced by inclusion of a second EBNA1/OriP plasmid for transient expression of additional genes such as SV40 T antigen. The duration of obtaining bona fide iPSC colonies from adult PB MNCs was reduced to half (∼14 days) as compared to adult fibroblastic cells (28–30 days). More than 9 human iPSC lines derived from PB or CB blood cells are extensively characterized, including those from PB MNCs of an adult patient with sickle cell disease. They lack V(D)J DNA rearrangements and vector DNA after expansion for 10–12 passages. This facile method of generating integration-free human iPSCs from blood MNCs will accelerate their use in both research and future clinical applications.

Keywords: iPS Cells, reprogramming, cord blood, episomal vectors, epigenetics, DNA methylation, sickle cell disease

Introduction

Human iPSCs that morphologically and functionally resemble human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have been generated from many somatic cell types by viral vectors expressing defined reprogramming factors since 2007. Generation of human iPSCs from blood MNCs offers several advantages over other cell types 1. It is more convenient and less invasive to obtain PB than dermal fibroblasts and keratinocytes, in which several weeks are required to establish a primary cell culture from skin biopsy. We and others have successfully generated iPSCs from human immature MNCs expressing CD34 or CD133 markers isolated from umbilical CB, adult PB and bone marrow (BM), after cultures of 2–4 days and gene transduction by the standard retroviral vectors expressing 4 or fewer reprogramming genes 2, 3, 4. The purified CD34-expressing (CD34+) and CD133-expressing (CD133+, nearly all CD34+) cells from blood or BM (≤ 2% of total MNCs) are enriched for human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Subsequently, 5 groups used viral vectors and generated human iPSCs from un-fractionated MNCs, after longer cell culture to activate a sub-population into a proliferating state 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Since T cells are most abundant in PB MNCs, and can be easily expanded and infected by viral vectors under these culture conditions, it is not surprising that all or the vast majority of the derived iPSCs in each of the 5 studies contain somatic V(D)J DNA rearrangements at the T cell receptor (TCR) loci. It is unclear, however, whether the preexisting genomic rearrangements in human T cell-derived iPSCs will affect iPSC differentiation to T and non-T cell lineages 1, 10, and whether T cell-derived iPSCs may form T cell lymphomas at an unexpectedly high rate as observed with reprogrammed mouse T cells 11. Thus, methods of iPSC derivation without altering the genome are preferred, ideally by a virus-free approach.

Recently, several virus-free and integration-free methods were reported, which generated mouse and human iPSCs by using purified proteins or mRNAs, as well as plasmids 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. However, most of these published studies using proteins or mRNAs needed serial delivery (up to 17–21 times) of multiple reprogramming molecules to targeted adherent cells. Two of these studies used plasmid-based episomal vectors to successfully reprogram human fetal neural progenitor cells and neonatal fibroblasts, generating integration-free iPSC lines 17, 18. This is based on a well-established technology that inclusion of the EBNA1 gene and the OriP DNA sequence from the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) enables a plasmid, after one-time DNA transfection, to replicate extra-chromosomally in many types of primate cells as a circular episome 19. However, the reported efficiency of reprogramming postnatal cells was very low (∼3–6 per 106 neonatal human fibroblasts), even when the best combination of 3 EBNA1/OriP plasmids expressing 7 genes was used in DNA transfection 17. For cell therapy development and disease modeling, it is necessary to develop more efficient methods to generate integration-free and virus-free human iPSCs from adult somatic cells that tend to be more refractory to reprogramming than fetal/neonatal cells. To this end, we constructed improved EBNA1/OriP episomal vectors for efficient reprogramming of adult and neonatal somatic cells. In addition, we sought human postnatal cell types that are easily accessible, and more importantly, amenable to producing high-quality iPSCs efficiently.

Results

Unique epigenetic and gene expression signatures of human blood cells

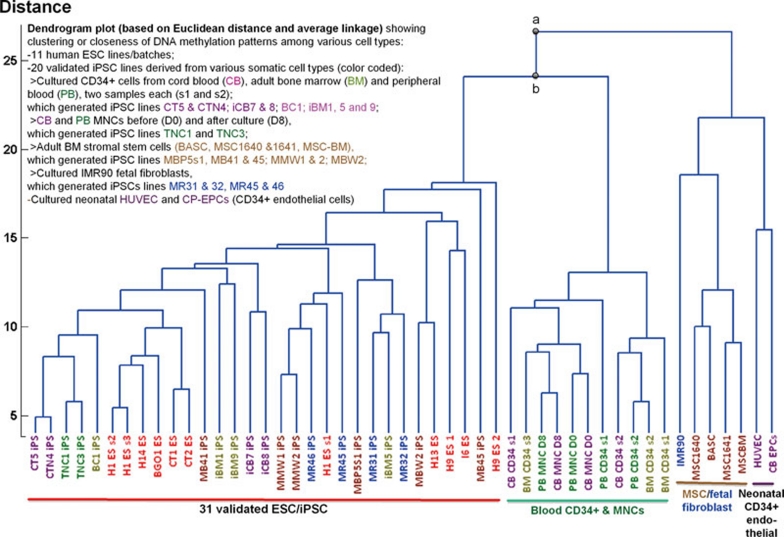

In this study, we analyzed global promoter DNA methylation in human CD34+ cells from CB, adult PB and BM, which are enriched for HSCs and appear more efficient in deriving iPSCs after improvement of retroviral delivery of standard reprogramming factors 2, 3, 4. Their signatures were compared to cultured adult BM-derived MSCs and other age-matched non-hematopoietic cells. We also included 11 human ESC samples to establish a baseline and 20 iPSC lines derived from the above somatic cell types, including 15 lines we derived previously by using integrating vectors 2, 20 and 5 iPSC lines derived by using episomal vectors in this study. To assess global DNA methylation, we performed genome-wide analysis using Illumina's Infinium Methylation27 platform containing 27 578 informative CpG sites near the promoter region, in which hypermethylation often correlates with repression of gene expression. A dendrogram plot using Euclidean distances revealed that the 20 validated iPSC lines derived from various somatic cell sources are highly similar to ESCs, but distinct from their parental cells (Figure 1). The cultured human blood (CD34+) cells are distinct from cultured endothelial cells (also CD34+) or MSCs/fibroblasts (CD34−). We also found that cultured blood (CD34+) cells cluster closer with the ESC/iPSC group than the non-hematopoietic cells (Figure 1). A similar clustering is also observed when using Pearson correlations to determine the distance metric (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Global epigenetic signatures and relatedness of human ESC lines, iPSC lines and their parental somatic cells. A dendrogram plot using Euclidean distances and average linkage based on DNA methylation at 26 424 autosomal loci in the Infinium Methylation27 platform, to analyze promoter DNA methylation genome-wide. 11 hESCs (passages 30–80) and 20 iPSCs derived from various somatic cell types (passage 5–15) that have a normal karyotype and validated pluripotency were analyzed. Parental cell types used for reprogramming include cultured CD34+ cells from cord blood (CB), adult peripheral blood (PB) and adult bone marrow (BM), CB and PB mononuclear cells (MNCs) before (D0) and after culture (D8), 4 types of adult BM stromal cells (MSC-BM, MSCs and BASC) and IMR90 fetal fibroblasts, neonatal cord-derived endothelial cells (CD34+) such as HUVEC and CB-derived endothelial progenitor cells (CB-EPCs). The clustering confirms that the 20 validated iPSC lines derived from various somatic cell sources are highly similar to ESCs, but distinct from their parental cells. DNA methylation patterns in human blood cells are more similar to ESC/iPSC group as compared to age-matched non-hematopoietic cells. Based on a two-sample t-test with unequal variances, we confirmed that the different mean distance corresponding to the indicated nodes a and b is statistically significant (P < 0.01).

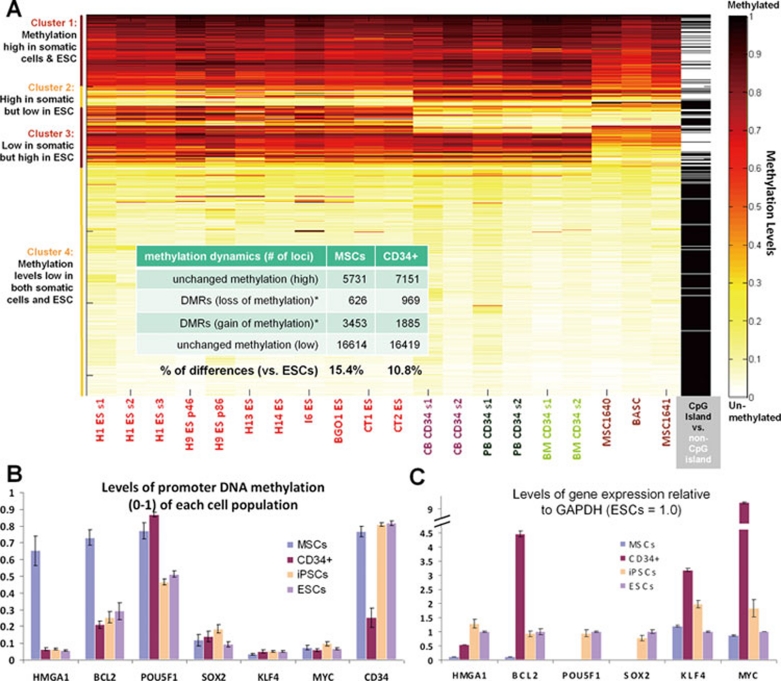

We next did a K-means clustering analysis of the same data (Figure 2A). The levels of promoter DNA methylation at 26 424 autosomal loci in postnatal blood/BM CD34+ hematopoietic cells and adult BM-derived MSCs were analyzed. Four distinct clusters emerged, based on relative levels of promoter DNA methylation in somatic cells as compared to the 11 ESCs (Figure 2A). Cluster #2 (high in somatic cells but low in ESCs) and cluster #3 (low in somatic cells and high in ESCs) contain loci showing different promoter DNA methylation levels between somatic cells and ESCs. While 15.4% of loci in MSCs are different from ESCs, only 10.8% of loci in CD34+ cells are different from ESCs, suggesting that hematopoietic CD34+ cells are closer to ESCs (and iPSCs, not shown) by this global analysis. In cluster #2, there are 234 loci (∼1%) that are hypermethylated in cultured MSCs but hypomethylated in blood CD34+ cells and ESCs/iPSCs (Figure 2B and Supplementary information, Table S1). We confirmed the high-level expression of two differentially hypomethylated genes, namely HMGA1 and BCL2, by quantitative RT-PCR in cultured CD34+ cells compared to MSCs derived from the same BM donor (Figure 2C). HMGA1 expression is high in undifferentiated human ESCs/iPSCs (and low in differentiated progeny) and in human CD34+ hematopoietic cells (and low in CD34– cells) 21, 22. BCL2 is highly expressed in CD34+ cells and mouse HSCs, and known to be critical for blocking apoptosis in HSCs as well as B cells 23. Interestingly, cultured BM CD34+ cells also express much higher levels of KLF4 and c-MYC than MSCs (Figure 2C), as found previously in CB CD133+/CD34+ cells 4. Thus, our data provide a rationale why hematopoietic CD34+ cells from CB and adult sources have a higher reprogramming efficiency than fibroblastic cells, as observed previously when retroviral vectors were used 2, 4, 20.

Figure 2.

Global epigenetic signature changes and gene expression patterns of human CD34+ hematopoietic cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). (A) K-means clustering analysis using the same promoter DNA methylation data as in Figure 1. To simplify presentation, we omitted iPSCs since they are highly similar to ESCs (11 lines/batches) that established a baseline. Two different samples of CD34+ cells from cord blood (CB), peripheral blood (PB) and bone marrow (BM) were used, together with 3 adult MSCs 3 samples. The level of promoter DNA methylation (from 0 to 1) of various loci (either within a CpG island or not) in postnatal somatic cells and in 11 ESC lines is analyzed. Four distinct clusters emerged: 1) high in both; 2) high in at least one type of somatic cells but low in ESCs; 3) low in somatic cells but high in ESCs; and 4) low in both somatic cells and ESCs. The numbers of loci in each cluster common in 3 MSCs or CD34+ cells are listed in the insert table. Clusters #2 and #3 consists of loci that are methylated differently from ESCs. Combining the two clusters, 15.4% of loci in MSCs are different from ESCs and only 10.8% of loci in CD34+ cells are different from ESCs. A list of cluster #2 genes that are hypomethylated in CD34+ cells and in ESC/iPSCs, but hypermethylated in MSCs is shown in Supplementary information, Table S1. (B) DNA methylation levels (mean +/− SEM, n ≥ 3) of two such genes are HMGA1 and BCL2 in multiple samples of BM MSCs, CD34+ cells, iPSCs and ESCs are plotted, together with the endogenous levels of the 4 reprogramming genes (OCT4 [also known as POU5F1], SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC). Levels at the CD34 gene loci are also plotted as a control. (C) The high levels of HMGA1 and BCL2 mRNA expression in cultured BM CD34+ cells (versus MSCs from the same donor) correlate with the lack of repressive hypermethylation marks. The levels of KLF4 and c-MYC expression are also very high in the cultured CD34+ cells used for reprogramming.

Reprogramming human CB CD34+ cells by episomal vectors

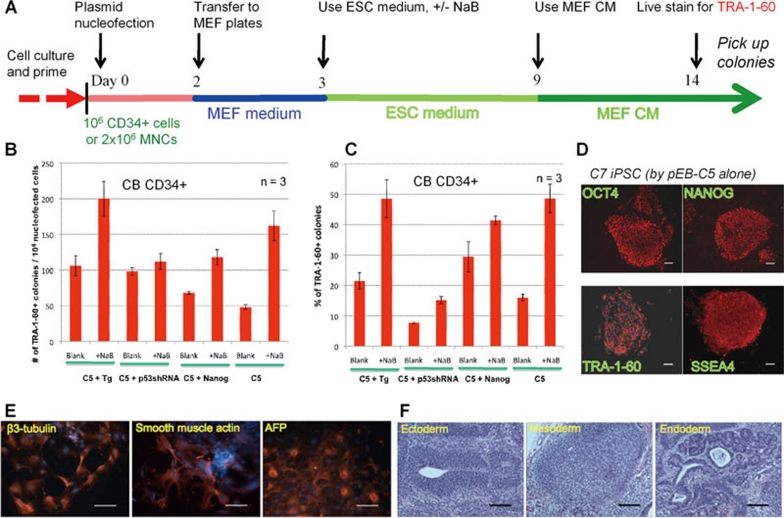

We next tested a novel set of EBNA1/OriP plasmids we constructed for reprogramming cultured CB CD34+ cells, which have the most favorable epigenetic/gene expression signatures and proliferative capacity as compared to adult CD34+ cells or fibroblasts/MSCs. In the first EBNA1/OriP plasmid (called pEB-C5), 5 reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC and LIN28) are expressed as a single poly-cistronic unit (Supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). In the second set of EBNA1/OriP plasmids, SV40 Large T antigen (Tg), NANOG or a small hairpin RNA targeting p53 (p53shRNA) is individually expressed. In the first set of 3 experiments (Supplementary information, Figure S3), the pEB-C5 and pEB-Tg plasmids were used in comparison with the Thomson/Yu combination #6 containing 3 plasmids 17. After expansion (∼5-fold) with cytokines for 4 days, CB CD34+ cells were transfected once and then cultured on MEF feeders following the standard protocol for deriving human iPSCs 2, 20 (Figure 3A and Supplementary information, Figure S3A). Previous studies showed that the acquisition of cell surface expression of TRA-1-60/TRA-1-81 is a reliable marker for monitoring full reprogramming of human somatic cells 20, 24, 25. We performed live staining of whole cultures at day 14 and numerated both TRA-1-60 positive and negative colonies (Supplementary information, Figure S3B–S3E). Our 2-plasmid combination generated similar numbers of TRA-1-60+ colonies (Supplementary information, Figure S2D), but their percentages among total colonies were much higher than combination #6 (Supplementary information, Figure S3E). We also observed that sodium butyrate (NaB), a nutritional supplement and HDAC inhibitor that stimulates reprogramming of human fibroblastic cells 20, also consistently enhanced the number (and percentages) of TRA-1-60+ colonies genetated by either vector combination (Supplementary information, Figure S3D–S3E).

Figure 3.

Reprogramming of human hematopoietic CD34+ cells from cord blood by 1–2 episomal vectors. (A) A diagram of procedure for human iPSC generation from blood cells. Purified CD34+ cells were cultured with cytokines for 4 days, and then nucleofected one-time by 1–2 plasmids at day 0. Transfected cells were cultured for 2 more days before transferring onto 6 wells coated with MEF feeder cells. At day 3, the ESC culture medium was used +/− sodium butyrate (NaB). After day 9, the MEF-derived conditioned medium (CM) was used to substitute plain ESC medium. At day 14, cultures were stained live with the TRA-1-60 antibody. (B) Reprogramming efficiency of cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells by various combinations of EBNA1/OriP epiosmal vectors, either pEB-C5 (C5) + pEB-Tg (Tg), C5 + pEB-p53shRNA, C5 + pEB-NANOG or C5 alone. The efficiency is measured at day 14 as numbers of TRA-1-60+, ESC-like colonies per 106 nucleofected cells (B). The percentages of TRA-1-60+ colonies among the total colonies are also plotted (C). Data are plotted as mean +/− SEM (n = 3). Discrete TRA-1-60+ colonies with the best ESC-like morphology were selectively picked after counting. (D) Phenotypes of expanded iPSC clone C7 derived from CB CD34+ cells by the single C5 vector. Scale bar: 100 μm throughout. (E) The C7 iPSCs display normal pluripotency as assayed by embryoid body formation and in vitro differentiation. Various cell types derived from all the 3 embryonic germ layers were found, based on positive staining of beta-3-tubulin (ectoderm), smooth muscle actin (mesoderm) and alpha-fetal protein or AFP (endoderm). Cell nuclei were counterstained by DAPI (blue). (F) In vivo pluripotency of C7 assayed by teratoma formation. The presence of various cell types derived from all the 3 embryonic germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) are shown in representative images of H & E stained sections.

In the second set of experiments, we tested whether we could replace Tg by either NANOG or p53shRNA (which inhibits p53 as by Tg expression), or omit Tg completely (Figure 3B–3C). The stimulatory effect of CB CD34+ cell reprogramming by the second vector over pEB-C5 alone was the greatest for Tg followed by p53shRNA, and minimal for NANOG. The pEB-C5 plasmid alone was sufficient to generate ∼50 TRA-1-60+ colonies from 106 nucleofected cells (expanded from ∼0.2 × 106 original CD34+ cells) without NaB (Figure 3B). In the presence of NaB during the reprogramming (day 3–14), ∼160 TRA-1-60+ colonies were generated (> 3-fold), accounting for ∼50% of the total colonies formed (Figure 3C).

After TRA-1-60 live staining, we picked individual ESC-like colonies derived by transfection with either pEB-C5 alone (C), pEB-C5 + pEB-Tg (CT) or CT in the presence of NaB (CTN). We examined at least two CB-derived clones from each category by standard assays. Undifferentiated phenotypes of one representative clone, C7, are shown in Figure 3D, and additional clones CT5 and CTN4 are shown in Supplementary information, Figure S4. We found that 5 of 6 clones derived with pEB-C5 + pEB-Tg vectors have a normal karyotype (CT5 and CTN4 are shown in Supplementary information, Figure S4D–S4E). To further analyze iPSCs derived with transient expression of Tg, we used genome-wide SNP analysis to examine the similarity of the CT5 and CTN4 genome to that of primary CB CD34- cells from the same CB donor. The genome-wide data (covering > 106 SNPs) indicate that CT5 and CTN4 iPSCs are essentially identical to CD34- cells of the CB donor and that reprogramming by the episomal vectors did not cause any detectable alterations in the genome (see Methods). Equally important, CT5 and CTN4 iPSCs are pluripotent as validated by both in vitro and in vivo differentiation assays (Supplementary information, Figure S4B–S4C). Similarly, the iPSC clones derived by the single C5 vector from the same donor (CN1) and a different donor (C7) are also pluripotent. The pluripotency and karyotyping data of the C7 iPSC line are shown in Figure 3E–3F and Figure 4D.

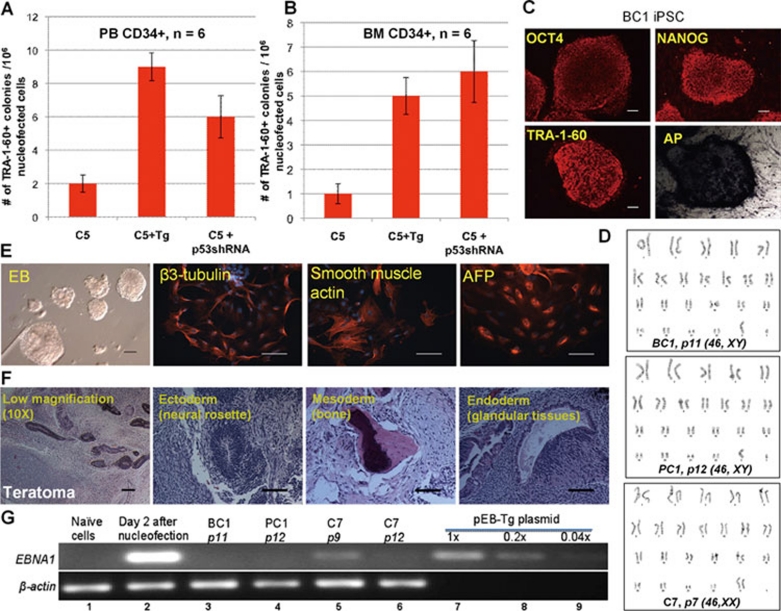

Figure 4.

Reprogramming of human adult hematopoietic CD34+ cells. Reprogramming efficiency of adult peripheral blood (PB, A) or bone marrow (BM, B) CD34+ cells by various plasmid combinations in the presence of NaB, as conducted in Figure 3. Numbers of TRA-1-60+, hESC-like colonies were numerated (mean +/− SEM) at day 14 after one-time nucleofection of 106 expanded cells. (C) Phenotypes of expanded iPSC clone BC1 derived from BM CD34+ cells by the single C5 vector. Scale bar: 100 μm throughout. (D) Normal karyotypes of iPSC lines derived by the single C5 vectors from 3 types of human CD34+ cells. (E) The BC1 iPSCs display normal pluripotency as assayed by embryoid body (EB) formation and in vitro differentiation. Various cell types derived from ectoderm (beta-3-tubulin), mesoderm (smooth muscle actin) and endoderm (alpha-fetal protein or AFP) were found. (F) In vivo pluripotency of BC1 assayed by teratoma formation. Both low (10×) and high (20×) magnification images of multiple H & E stained sections are shown. Various cell types such as neural rosettes (ectoderm), bone (mesoderm) and glandular structures (endoderm) are found. (G) PCR-based detection of vector sequence (EBNA1) in 3 iPSCs derived from human CD34+ by the single C5 vector. The single-copy cellular sequence beta-actin is used as a quality control for isolated genomic DNA. Total DNA isolated from the cells before (naïve) and after nucleofection (day 2) was used as negative and positive controls for vector DNA. The pEB-Tg plasmid diluted in amounts equivalent to 1, 0.2 or 0.04 copies per genome of cellular DNA is used as a control for detection of the EBNA1 viral DNA sequence.

Reprogramming adult hematopoietic CD34+ cells by 1–2 episomal vectors

We next used this approach to derive iPSCs from human adult PB or BM CD34+ cells by 1 or 2 EBNA1/OriP plasmids (Figure 4). After 4 days of culture and expansion, 106 primed cells were nucleofected by the same sets of plasmids. The ESC-like TRA-1-60+ colonies emerged at day 9–11, about 3–4 days later than those from CB CD34+ cells. We found the efficiency of reprogramming adult CD34+ cells was ∼50-fold lower than CB CD34+ cells (per 106 cells transfected by the same vector sets), although sufficient numbers of iPSC colonies formed (Figure 4A–4B). Adding a second EBNA1/OriP vector expressing Tg or shRNA targeting p53 increased the efficiency by ∼5-fold. Human iPSC clones derived from adult CD34+ cells by the single pEB-C5 vector were picked, expanded and characterized as before. One clone from PB CD34+ cells (PC1) and one from BM CD34+ cells (BC1) were further characterized after 5–12 passages. Both iPSCs show undifferentiated phenotypes (Figure 4C) and have normal karyotypes as C7 iPSCs derived from CB CD34+ cells (Figure 4D). They are also pluripotent by in vitro (Figure 4E) and in vivo (Figure 4F) differentiation assays, similar to C7 iPSCs shown in Figure 3. We also examined the presence of the vector DNA in these 3 iPSCs at various stages (Figure 4G). In general, a trace amount of vector DNA (< 0.2 copies per cell) could be detected after reprogramming (lasting 14 days) and expansion for 9 passages (∼50 days), but they became undetectable in most cases by passage 10–12 (Figure 4G and Supplementary information, Figure S4G). Our data are consistent with previous publications showing that the EBNA1/OriP episomal DNA in human fetal or neonatal cell-derived iPSCs is spontaneously and gradually lost after reprogramming 17, 18. This is likely due to the silencing of EBNA1 gene expression and/or loss of OriP DNA functions in iPSCs, resulting from different DNA methylation and other epigenetic regulations from those in somatic cells. We also performed DNA fingerprinting on these iPSC lines derived by a single non-integrating vector and confirmed their authentic origins (Supplementary information, Figure S5).

Culture and activation of un-fractionated blood MNCs for reprogramming

Next, we attempted to reprogram un-fractionated blood MNCs (without CD34 cell purification) by the improved episomal vectors. Uncultured or cultured MNCs under the CD34+ cell culture condition did not survive well before or after nucleofection, resulting in zero iPSC colonies per 5 million MNCs. We tested various culture conditions that would stimulate myeloid-erythroid proliferation from MNCs, and avoided the standard protocols expanding T and/or B cells that contain V(D)J DNA rearrangements (and thus an altered genome). We chose a condition that stimulates erythroblast proliferation 26 for the following 4 reasons. 1) We observed net gains of cell numbers after culture: 2.5-fold by day 8 for CB MNCs and 1.5-fold by day 8–9 for PB MNCs, despite a reduction in the first 2–4 days (Supplementary information, Figure S6A). 2) The expanded cells contained very few T or B cells compared to input MNCs (Supplementary information, Figure S6B–S6C). Nearly all the expanded cells expressed an erythroblast marker CD36 (not shown), and many expressed CD71high/CD235a+ erythroid phenotypes. They also showed erythroblast morphology at day 8–9 (Supplementary information, Figure S7A), and were enriched for colony-forming erythroid progenitor cells (Supplementary information, Figure S7B). The data suggest that the resulting cells after expansion are enriched for highly proliferative erythroblasts as previously reported 26. 3). The expanded cells from adult PB MNCs resembled neonatal cells found in CB cells. Surprisingly the levels of fetal/neonatal hemoglobin (HBG, gamma-globin) gene expression were greatly (> 8 000-fold) increased in expanded PB MNCs, and more cultured cells (> 70%) expressed HBG (gamma-globin) proteins as compared to uncultured PB MNCs (Supplementary information, Figure S8). 4). The culture condition also elevated the expression of genes associated with pluripotency or reprogramming enhancement such as HMGA1 and c-MYC (Supplementary information, Figure S9).

Reprogramming un-fractionated blood MNCs by episomal vectors after stimulation by cell culture

We further devised a condition to efficiently transfect expanded cells with favorable profiles. Two million cells were transfected one-time by nucleofection with the same 1–2 EBNA1/OriP episomal vectors, and followed by an identical reprogramming protocol as before (Figure 3A). The cultured CB MNCs after 8-day culture can generate TRA-1-60+ iPSC-like colonies very efficiently (Figure 5A). Although variations of different CB MNC preparations existed, the overall reprogramming efficiency is very high: 930 and 320 TRA-1-60+ colonies formed by day 14 per 2 × 106 transfected MNCs by the single pEB-C5 episomal vector in the presence of NaB. The stimulatory effect of Tg or NaB is minimal for the cultured CB MNCs (Figure 5A). The generation of iPSCs by the 1–2 EBNA1/OriP episomal vectors was also achieved with the cultured PB MNCs including those from an adult sickle cell disease patient (SCD003), although the efficiency is much lower than that of CB MNCs (Figure 5B and Supplementary information, Figure S10). The pEB-C5 vector alone is sufficient to generate 3.2 iPSCs at day 14 after transfection of 2 × 106 cultured MNCs that can be easily obtained from ∼106 MNCs isolated from ≤ 1 ml volume of PB. Similar to adult PB CD34+ cells, PB MNC reprogramming is more dependent than CB MNCs on NaB stimulation. Adding pEB-Tg further increased the efficiency by ∼4-fold, resulting in 14 iPSCs per 2 × 106 cultured MNCs. Thus, the efficiency is adequate for nearly all applications involving PB, and is even higher with CB MNCs (Figure 5A).

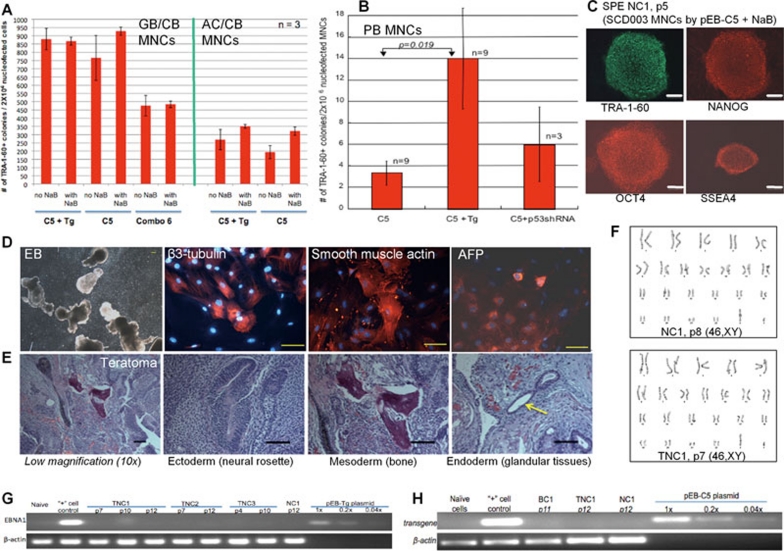

Figure 5.

Human iPSC derived from adult peripheral blood (PB) and cord blood (CB) mononuclear cells (MNCs) by a single EBNA1/OriP plasmid. (A) Reprogramming efficiency of CB MNCs. Two different CB MNCs, frozen 1.5 months before (GB/CB) and 13 years before (AC/CB), were cultured for 8 days. 2 × 106 cultured and primed cells were nucleofected by 1–3 EBNA1/OriP plasmids as indicated. C5: pEB-C5; Tg: pEB-Tg; Combo 6: the Thomson/Yu combination #6 (3 plasmids). The reprogramming proceeded as with CD34+ cells (Figure 3A), with or without sodium butyrate (NaB). Numbers of TRA-1-60+ colonies (on day 14) per 2 × 106 nucleofected cells are plotted as mean +/− SEM, n = 3. (B) PB MNCs (from donor SCD003) were similarly reprogrammed by the same approach in the presence of NaB (day 3-14), after an initial cell culture and stimulation for 8–9 days. (C) Representative images of undifferentiated phenotypes of an iPSC clone (NC1, passage 5) generated from SCD003 PB MNC-derived erythroblasts (SPE) by the pEB-C5 (C5) vector alone + NaB. Scale bar: 100 μm throughout. (D) Blood MNC-derived iPSCs such as NC1 display normal pluripotency as assayed by embryoid body (EB) formation and in vitro differentiation. Various cell types derived from ectoderm (beta-3-tubulin), mesoderm (smooth muscle actin) and endoderm (alpha-fetal protein or AFP) were found. (E) In vivo pluripotency of NC1 assayed by teratoma formation. Both low (10×) and high (20×) magnification images of multiple H & E stained sections are shown. Various cell types such as neural rosettes (ectoderm), bone (mesoderm) and glandular tissues (endoderm, yellow arrow) were found. (F) Normal karyotypes of 2 iPSC lines (NC1 and TNC1) derived by a single plasmid (C5) or two plasmids (C5+Tg). (G) Lack of vector DNA in expanded iPSCs (clones NC1, TNC1, TNC2 and TNC3) after 10–12 passages, as analyzed in Figure 4G. (H) Selected iPSCs (passages 11–12) were also analyzed by a different pair of PCR primers to detect vector DNA at the region encoding reprogramming transgenes. Lack of vector DNA in the iPSCs by Southern blot analysis is shown in Supplementary information, Figure S11.

We further characterized the iPSC lines derived from cultured adult PB MNCs (called SPE for Sickle PB Erythroblast). Four expanded and further characterized SPE iPSC lines derived by pEB-C5 alone (NC1) or two vectors including pEB-Tg (TNCx, x = 1, 2, or 3) show undifferentiated phenotypes (Figure 5C). They are pluripotent as confirmed by both in vitro and in vivo differentiation assays (Figure 5D–5E), and normal in karyotype (Figure 5F). Four characterized iPSC clones (NC1, TNC1, 2 and 3) were also analyzed by PCR to detect the presence of vector DNA (such as EBNA1) in expanded iPSCs at various passages. We again found that the plasmid DNA is undetectable after 10–12 passages of iPSC expansion (Figure 5G and 5H). Similar results were found when PCR detection for vector DNA from a different region was conducted. We also conducted Southern blot analysis that is capable of detecting a single copy of vector DNA (Supplementary information, Figure S11). The southern blot did not detect the vector DNA either as episomes or anywhere in the genome of NC1, TNC1, BC1 and C7 iPSCs we analyzed. We also examined if the iPSC lines we derived from cultured PB MNCs could be from T or B lymphocytes (Supplementary information, Figure S12). Using 7 sets of probes for detecting rearranged TCR and immunoglobin (IGH) loci, we did not find any evidence of somatic V(D)J rearrangements in the 6 iPSC lines. Table 1 summarizes the characterizations of 10 most analyzed iPSC lines we derived from human blood cells by transient transfection of 1–2 episomal vectors.

Table 1. List of characterized integration-free human iPSC lines derived from blood cells by 1–2 plasmids.

| iPSC Lines | Cell Source | Episomal Vectors | ± NaB | Karyotyping (passages tested) | Pluripotency Markers1 | in vitro Pluripotency Assay2 | in vivo Pluripotency Assay3 | ESC-like Global DNA Methylation Signatures | Genetic Identity4 | Absence of V(D)J DNA Recombination | Absence of vector DNA5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT5 | CB CD34+ All Cells, Lot#100204 | pEB-C5,Tg | No | Normal (46,XY) (p7) | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | Yes | Confirmed | N/A | P |

| CTN4 | CB CD34+ All Cells, Lot#100204 | pEB-C5,Tg | Yes | Normal (46,XY) (p8) | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | Yes | Confirmed | N/A | P |

| C7 | CB CD34+ All Cells, Lot#CBC091022A | pEB-C5 | No | Normal (46,XX) (p7) | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | N/D | N/A | N/A | P, S |

| BC1 | ABM CD34+ All Cells, Lot# BM2426 | pEB-C5 | No | Normal (46,XY) (p11) | Positive | Yes | Yes (4/4) | Yes | Confirmed | N/A | P, S |

| PC1 | mPB CD34+ All Cells, Lot# A1868B | pEB-C5 | No | Normal (46,XY) (p12) | Positive | N/D | Yes (2/2) | N/D | N/D | N/A | P |

| AC/CB1 | CB MNCs frozen for 13 years | pEB-C5 | No | Normal (46,XX) (p12) | Positive | Yes | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| SPE NC1 | PB MNCs SCD003 | pEB-C5 | Yes | Normal (46,XY) (p8) | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | N/D | Confirmed | Absent | P, S |

| SPE TNC1 | PB MNCs SCD003 | pEB-C5,Tg | Yes | Normal (46,XY) (p7 & p17) | Positive | Yes | Yes (2/2) | Yes | Confirmed | Absent | P, S |

| SPE TNC2 | PB MNCs SCD003 | pEB-C5,Tg | Yes | Normal (46,XY) (p6) | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | N/D | Confirmed | Absent | P |

| SPE TNC3 | PB MNCs SCD003 | pEB-C5,Tg | Yes | N/D | Positive | Yes | Yes (1/1) | Yes | Confirmed | Absent | P |

NaB: Sodium Butyrate (added during the reprogramming); N/D: not done yet; N/A: not applicable

Staining for a panel of pluripotency markers including OCT4, NANOG, TRA-1-60, SSEA4 and alkaline phosphatase

By embryoid body formation assay showing the presence of various cell types derived from all the embryonic 3 germlayers

By teratoma formation assay (No. of positive/No. of samples tested)

Conformation of gnetic identity to the corresponding parental cell type by PCR detecting variable short tandem repeats. High-density SNP assays were also used to authenticate CT5 and CTN4 iPSCs. Three SPE iPSCs lines derived from the SCD003 donor all contain the sickle mutation (A to T at condon 6) in both alleles of the beta-globin gene

Detection of vector DNA by either PCR (P) or Southern blot (S) methods.

Discussions

We describe in this report an efficient method for generating human iPSCs with an intact genome by using a single episomal vector to transfect briefly-cultured adult PB or CB MNCs. Transient expression of a second vector (pEB-Tg) further increased reprogramming efficiencies of adult PB CD34+ and MNCs by 4-fold, although its stimulatory activity is much less on CB cells that have a much higher reprogramming efficiency. Tg stimulation on reprogramming was observed by several groups using different vectors and somatic cell types 17, 27. Transient expression of Tg by episomal vectors did not necessarily alter karyotypes of the derived iPSCs (17 and this study), or global epigenetic signatures as shown in Figure 1. Transient p53 inhibition by shRNA expression from an episomal vector also enhanced reprogramming efficiency as previously observed in studies using genome-integrating viral vectors 28, 29, although its stimulatory effect on PB cell reprogramming is less than Tg over-expression. Interestingly, we noticed that all 5 of the iPSC lines derived from blood cells by non-integrating vectors we analyzed so far clustered together (and close to a group of hESC lines), based on promoter DNA methylation signatures. They appear distinct from other iPSCs derived by integrating vectors from either blood CD34+ cells or MSCs/fibroblasts (Figure 1). A recent study found that mouse blood cell-derived iPSCs more closely resemble ESCs epigenetically and functionally than those derived from fibroblasts 30. Whether the virus-free and integration-free human iPSCs we derived from blood cells and by the non-integrating vectors are superior in quality (closer to the best human ESCs) than previous iPSC lines derived by integrating vectors remains to be determined.

Our EBNA1/OriP episomal vector system offers several important advantages over the previous episomal vector combinations for reprogramming postnatal human cell types 17. First, the pEB-C5 plasmid (+/− pEB-Tg) generated a higher percentage of TRA-1-60+ pre-iPSC colonies, especially in the presence of NaB, facilitating the efficient isolation of the desired TRA-1-60+ colonies. Second, the platform is more flexible if one needs to omit or replace Tg with other factors for mechanistic investigations. More importantly, our vector system, together with optimized cell culture conditions, allows us to efficiently generate integration-free human iPSCs from blood MNCs isolated from a few milliliters of blood after suspension cultures for 8–9 days. When further enhancement is needed for other cell types, or patient's blood MNCs that are more refractory to reprogramming by the current episomal vectors, we can easily add additional reprogramming genes over the 5–6 transgenes we used. Since we can deliver multiple (at least 8) genes from a single EBNA1/OriP plasmid for simultaneous and transient expression, it is no longer critical to reduce the numbers of reprogramming factors used. Obviously, small numbers of vectors (1–2) are preferred to ensure the lack of episomal vector DNA in the reprogrammed and expanded iPSC lines. Using PCR (3 sets of specific primers) and Southern blot, we did not detect vector DNA either as episomes or anywhere in the genome of the iPSCs analyzed. More sensitive methods are needed to detect residual vector DNA or to eliminate (episomal) vector DNA more efficiently than the passive expansion and dilution approach we used here.

Increasing evidence suggests that both DNA replication-dependent and -independent mechanisms are involved in promoting reprogramming, which is fundamentally an epigenetic process 31. Our success in generating iPSCs from un-fractionated human blood MNCs depends on a culture condition to obtain a proliferating cell population that is neither T nor B cells, before plasmid-mediated reprogramming. We also detected that the proliferating cells derived from human blood MNCs or purified CD34+ cells display a global profile of promoter DNA methylation that groups closer to human ESCs/iPSCs than age-matched non-hematopoietic cells such as fibroblastic and endothelial cells. The unique blood cell DNA methylation and gene expression signatures may contribute to the high efficiency of iPSC derivation from blood cells we achieved by using a single episomal vector after one-time DNA transfection. Our data further substantiate the hypothesis that differences in epigenetic profiles among different human adult cell types contribute to differences in reprogramming efficiencies as well as the properties of derived iPSCs, as previously shown in the mouse system 30. It is of interest to determine if the serial delivery of synthetic mRNAs encoding 4–5 reprogramming factors or purified proteins could reprogram human blood MNCs more efficiently than human fibroblasts as reported recently.

The facile method described here that reprograms blood cells after minimal culture and using plasmids provides several important advantages over other virus-free and integration-free methods. First, one-time delivery of 1–2 plasmids that are much easier to produce and more stable than proteins or mRNAs makes our method more attractive or feasible for generation of clinical-grade iPSCs under current good manufacture practice (cGMP) conditions. Second, the capability to reprogram PB MNCs not only provides a readily available source of human cells for iPSC derivation 1, but also shortens the cell culture time required to prepare and prime the target cells for reprogramming (now < 10 days from blood versus ≥ 4 weeks from skin biopsies). Our combined method of using MNCs from a few milliliters of blood and non-integrating plasmids brings the iPSC derivation technology to a new level, and offers greater promise for the use of patient iPSCs for disease modeling and future clinical applications in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Approvals of using human ESCs, iPSCs and primary cells from anonymous donors

The experimental designs using human ESCs and iPSCs were approved by the Institutional Stem Cell Research Oversight (ISCRO) committee in the Johns Hopkins University. Use of anonymous human samples for laboratory research was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Constructions of episomal vectors

All transgenes were cloned into the EBNA1/OriP-based pCEP4 episomal vector (Invitrogen). A single EBNA1/OriP vector expressing five (mouse) cDNAs Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc and Lin28 that are linked by 2A sequences and under the control of the synthetic CAG promoter was constructed in the pCEP4 plasmid backbone, analogous to a piggyBac transposon plasmid we previously used 20. The cDNA for the SV40 large T antigen was PCR cloned and inserted into the pCEP4 plasmid backbone as we did previously into a lentiviral vector 27. The expression cassette for expressing p53-shRNA was obtained by digesting a fragment from a pSUPER-based vector, and was inserted into the pCEP4 plasmid. See more details in Supplementary information, including Figures S1 and S2.

Genome-wide analysis of promoter DNA methylation

The promoter DNA methylation data was generated using the Infinium Human DNA Methylation27 BeadArray platform (Illumina, San Diego, California). This platform allows us to interrogate DNA methylation of 27 578 informative CpG sites at single-nucleotide resolution.

Additional Materials and Methods are provided in Supplementary information, Data S1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr William Savage for providing phlebotomized blood cells from adult patients with adult sickle disease, Dr Wayne Yu for DNA methylation BeadArray detection, Dr Rasika Mathias for analyzing SNP data and Dr Jizhong Zou for assisting with Southern blot using non-radioactive probes. Genomic DNA samples from additional human ESC lines were kindly provided by Drs Renhe Xu (CT1, CT2, and H1), Xianmin Zeng (H1, H14, BG01 and I6) and Sharon Gerecht (H13). Dr Gerecht's group also provided human neonatal endothelial cells (HUVEC and CB-EPCs) for making genomic DNA. We also thank Drs Robert Brodsky and Paul Liu for critical reading. This study is supported by Johns Hopkins University, a New York State Stem Cell research grant (N08T-019), and grants from the NIH (R01HL073781, U01HL099775, RC2HL101582 and T32HL007525). BKC was supported by the Taiwan Merit Scholarship NSC-095-SAF-I-564-019-TMS and PM is a Siebel Scholar.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Diagrams of novel episomal vectors used in this report, based on an EBNA1/OriP-containing plasmid.

The DNA sequence of the pEB-C5 reprogramming vector (the orientation is as indicated in the graphic map in Figure S1A).

Reprogramming of cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells by various combinations of episomal vectors.

Characterization of iPSC lines derived from CB CD34+ cells reprogrammed by pEB-C5 and pEB-Tg plasmids or by pEB-C5 alone.

DNA fingerprinting to confirm the authenticity of iPSCs as compared to their somatic cell origins.

Growth curves and phenotypes of expanded mononuclear cells (MNCs) from newborn cord blood (CB or adult peripheral blood (PB).

Morphology and functions of expanded cells from adult peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (MNCs).

Hemoglobin expression patterns of expanded adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs).

Analysis of mRNA levels of key genes involved in reprogramming in blood mononuclear cells (MNCs) before (day 0) and after culture and priming (day 8).

Reprogrammed iPSC-like colonies from un-fractionated adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs).

Southern blot analyses for the lack of vector DNA in expanded iPSCs that are derived by episomal vectors.

Six iPSC lines we derived from PB MNCs lack any detectable somatic mutations associated with committed T cells and B cells.

A list of loci that are hypermethylated in adult MSCs (3 samples), compared to human hematopoietic CD34+ cells (6 samples), iPSCs (17 lines) and ESCs (11 samples).

Experimental Procedures

References

- Yamanaka S. Patient-specific pluripotent stem cells become even more accessible. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z, Zhan H, Mali P, et al. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells from blood cells of healthy donors and patients with acquired blood disorders. Blood. 2009;114:5473–5480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Agarwal S, Park IH, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human blood. Blood. 2009;113:5476–5479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Aasen T, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood using OCT4 and SOX2. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisato A, Wakatsuki M, Shinba H, et al. Direct Generation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells from Human Nonmobilized Blood Stem Cells Dev 2010. Sep 14. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0063 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown ME, Rondon E, Rajesh D, et al. Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Yuasa S, Oda M, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human terminally differentiated circulating T cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh YH, Hartung O, Li H, et al. Reprogramming of T cells from human peripheral blood. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:15–19. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staerk J, Dawlaty MM, Gao Q, et al. Reprogramming of human peripheral blood cells to induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwold T, Hochedlinger K, Inlay M, Jaenisch R, Weissman IL. Early TCR expression and aberrant T cell development in mice with endogenous prerearranged T cell receptor genes. J Immunol. 2007;179:928–938. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwold T, Hochedlinger K, Swindle J, Hedgpeth J, Jaenisch R, Weissman IL. T-cell receptor-driven lymphomagenesis in mice derived from a reprogrammed T cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;07:18939–18943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013230107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Nakagawa M, Hyenjong H, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells without viral vectors. Science. 2008;322:949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1164270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Wu S, Joo JY, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Kim CH, Moon JI, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:472–476. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Wilson KD, Sun N, et al. A nonviral minicircle vector for deriving human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2010;7:197–199. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu K, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science. 2009;324:797–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1172482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetto MC, Yeo GW, Kainohana O, et al. Transcriptional signature and memory retention of human-induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner SE, Sugden B. The plasmid replicon of Epstein-Barr virus: mechanistic insights into efficient, licensed, extrachromosomal replication in human cells. Plasmid. 2007;58:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Chou BK, Yen J, et al. Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency-associated genes. Stem Cells. 2010;28:713–720. doi: 10.1002/stem.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, et al. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Chen J, Lee S, Clark T, Rowley JD, Wang SM. The pattern of gene expression in human CD34(+) stem/progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13966–13971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241526198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domen J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cells need two signals to prevent apoptosis; BCL-2 can provide one of these, Kitl/c-Kit signaling the other. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1707–1718. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan EM, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Park IH, et al. Live cell imaging distinguishes bona fide human iPS cells from partially reprogrammed cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:1033–1037. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry WE, Richter L, Yachechko R, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from dermal fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2883–2888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711983105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker E, Satchwell T, Pellegrin S, Daniels G, Toye A. The majority of the in vitro erythroid expansion potential resides in CD34(-) cells, outweighing the contribution of CD34(+) cells and significantly increasing the erythroblast yield from peripheral blood samples. Haematologica. 2010;95:1594–1598. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.019828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P, Ye Z, Hommond HH, et al. Improved efficiency and pace of generating induced pluripotent stem cells from human adult and fetal fibroblasts. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1998–2005. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yin X, Qin H, et al. Two supporting factors greatly improve the efficiency of human iPSC generation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:475–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizhanovsky V, Lowe SW. The promises and perils of p53. Nature. 2008;460:1065–1086. doi: 10.1038/4601085a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Saha K, Pando B, et al. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature. 2009;462:595–601. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagrams of novel episomal vectors used in this report, based on an EBNA1/OriP-containing plasmid.

The DNA sequence of the pEB-C5 reprogramming vector (the orientation is as indicated in the graphic map in Figure S1A).

Reprogramming of cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells by various combinations of episomal vectors.

Characterization of iPSC lines derived from CB CD34+ cells reprogrammed by pEB-C5 and pEB-Tg plasmids or by pEB-C5 alone.

DNA fingerprinting to confirm the authenticity of iPSCs as compared to their somatic cell origins.

Growth curves and phenotypes of expanded mononuclear cells (MNCs) from newborn cord blood (CB or adult peripheral blood (PB).

Morphology and functions of expanded cells from adult peripheral blood (PB) mononuclear cells (MNCs).

Hemoglobin expression patterns of expanded adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs).

Analysis of mRNA levels of key genes involved in reprogramming in blood mononuclear cells (MNCs) before (day 0) and after culture and priming (day 8).

Reprogrammed iPSC-like colonies from un-fractionated adult peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PB MNCs).

Southern blot analyses for the lack of vector DNA in expanded iPSCs that are derived by episomal vectors.

Six iPSC lines we derived from PB MNCs lack any detectable somatic mutations associated with committed T cells and B cells.

A list of loci that are hypermethylated in adult MSCs (3 samples), compared to human hematopoietic CD34+ cells (6 samples), iPSCs (17 lines) and ESCs (11 samples).

Experimental Procedures