Background: SQN (SQUINT), the Arabidopsis ortholog of cyclophilin 40, promotes microRNA-mediated gene silencing by promoting the activity of AGO1.

Results: SQN bound to Hsp90, and this is required for the activity of SQN in planta.

Conclusion: SQN promotes AGO1 activity in association with Hsp90.

Significance: Determining how AGO1 is regulated is essential for understanding the mechanism of microRNA-mediated gene silencing in plants.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Immunophilin, MicroRNA, Plant Biochemistry, Plant Molecular Biology, Argonaute, Hsp90

Abstract

SQN (SQUINT) is the Arabidopsis ortholog of the immunophilin CyP40 (cyclophilin 40) and promotes microRNA activity by promoting the activity of AGO1. In animals and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, CyP40 promotes protein activity in association with the protein chaperone Hsp90. To determine whether CyP40 also acts in association with Hsp90 in plants, we examined the interaction between SQN and Hsp90 in vitro and tested the importance of this interaction for the function of SQN in planta. We found that SQN interacts with cytoplasmic Hsp90 proteins but not with Hsp90 proteins localized to chloroplasts, mitochondria, or the endoplasmic reticulum. The interaction between SQN and Hsp90 in vitro requires the MEEVD domain of Hsp90, as well as several conserved amino acids within the tetratricopeptide repeat domain of SQN. Amino acid substitutions that disrupt the interaction between SQN and Hsp90 in vitro also impair the activity of SQN in planta. Our results indicate that the interaction between CyP40 and Hsp90 is conserved in plants and that this interaction is essential for the function of CyP40.

Introduction

SQN (SQUINT) is the Arabidopsis ortholog of CyP40 (cyclophilin 40), an ancient, highly conserved protein co-chaperone (1). SQN was originally identified because of its developmental phenotype: sqn mutants undergo precocious phase change, have a reduced rate of leaf initiation, and display a variety of floral defects. This phenotype is attributable to an increase in the expression of microRNA (miRNA)2-regulated genes, which is thought to result from a decrease in the activity of AGO1 (ARGONAUTE1) (2, 3), the protein that is largely responsible for miRNA-directed gene repression in Arabidopsis (4–6). The mechanism by which SQN promotes the activity of AGO1 is unknown.

CyP40 has two evolutionarily conserved domains. The N-terminal part of the protein has a high degree of similarity to the cyclophilin family of peptidyl-proline isomerases (PPIases) and has PPIase activity in both mammals and yeast (7, 8). The C-terminal end of the protein consists of three tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs). In mammals, CyP40 is found in association with Hsp90 (heat shock protein 90) in a number of different steroid hormone receptor complexes (9, 10). In vitro studies and yeast two-hybrid experiments indicate that CyP40 binds to Hsp90 via these TPRs (11–14). Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two CyP40 proteins, Cpr6p and Cpr7p, both of which bind to Hsp90 (15). Loss-of-function mutations in CPR6 have no obvious phenotype, but mutations in CPR7 decrease the growth rate of yeast cells and produce a synergistic growth defect in combination with mutations in HSP90 (16, 17), implying that Cpr7p and Hsp90 have related functions. Interestingly, the slow growth phenotype of cpr7 cells can be rescued by a peptide consisting solely of the Cpr7 TPR domain (16). Although the cyclophilin and TPR domains of SQN are quite similar to the corresponding domains of the mammalian and yeast proteins, there is currently no evidence that SQN has PPIase activity or that it directly interacts with Hsp90 (2, 18).

CyP40 is structurally similar to multidomain FK506-binding proteins (FKBPs). Like CyP40, these proteins possess an N-terminal PPIase domain and C-terminal TPRs and are thought to function as protein co-chaperones in association with Hsp90 (19, 20). Arabidopsis has seven multidomain FKBP genes, of which FKBP62/ROF1, FKBP72/PAS1, and FKBP42/TWD1/UCU2 are the best characterized (20, 21). ROF1 confers resistance to heat stress through its effects on small heat shock proteins (22). TWD1/UCU1 regulates polar auxin transport by interacting with the ATP-binding cassette transporters PGP1/ABCB1 and PGP19/ABCB19 (23, 24) and directing them to the plasma membrane (25). PAS1 promotes the cytokinin-dependent repression of cell proliferation through its interaction with the transcription factor FAN (26, 27). ROF1 and TWD1/UCU1 have both been shown to interact with Hsp90, but the functional significance of this interaction remains unknown (22, 28).

Hsp90 is an evolutionarily conserved protein chaperone that regulates the activity of a variety of substrates, many of which are involved in the cell cycle and in signal transduction (29, 30). The Arabidopsis genome contains seven Hsp90 genes (31, 32). Four of these (HSP90.1, HSP90.2, HSP90.3, and HSP90.4) encode cytoplasmic proteins, and three (HSP90.5, HSP90.6, and HSP90.7) encode proteins that localize to chloroplasts, mitochondria, and the endoplasmic reticulum, respectively (32–35). HSP90.2, HSP90.3, and HSP90.4 are encoded by genes located in tandem on chromosome 5 and have almost identical amino acid sequences (96% identity) (31, 32). HSP90.1 is 88% identical to HSP90.2. Mutations in the chloroplast-localized protein HSP90.5 and the endoplasmic reticulum-localized protein HSP90.7 have severe pleiotropic developmental phenotypes (33, 35). A null allele of the cytoplasmic protein HSP90.2 has no obvious phenotype, but missense mutations in its ATP-binding domain decrease disease resistance and have a weak effect on shoot morphology (2, 36). Mutations in HSP90.1, HSP90.2, or HSP90.3 cause poorly penetrant defects in seedling morphology (31). Simultaneous reduction of multiple cytoplasmic Hsp90 proteins by RNAi or by the Hsp90 inhibitor geldanamycin produces severely defective seedlings, some of which resemble ago1 mutants (31).

The discovery that Hsp90 co-purifies with Argonaute-containing RNA-induced silencing complexes (37–39) provided the first evidence that it is involved in miRNA- and siRNA-mediated gene silencing. More recent studies in both animals (40, 41) and plants (42) indicate that Hsp90 is specifically required for the loading of small RNAs into RNA-induced silencing complexes. On the basis of the association of Hsp90 with apo-steroid hormone receptor complexes, it has been suggested that Hsp90 may hold Argonaute proteins in a loading-competent state (42). These observations, the genetic evidence indicating that SQN regulates AGO1 activity (2, 3), and the observation that CyP40 interacts with Hsp90 in yeast and mammals (11–14) suggest that SQN facilitates the assembly or function of an HSP90-AGO1 complex. In support of this hypothesis, we report here that SQN binds to the cytoplasmic isoforms of HSP90 in Arabidopsis and that this interaction is required for the normal function of SQN in planta.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Western Blotting

Plants were grown on Fafard 2 soil at 23 °C under 16-h fluorescent illumination. Leaf tissue was harvested from 14-day-old plants and ground with a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen. Ground tissue was suspended in 20 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 300 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), 1 mm PMSF, and 1 mm DTT. Equal concentrations of soluble protein were separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose, and membranes were then blocked with TBS/Tween and 5% milk. Membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody (1:2000; Sigma) in TBS/Tween and 5% milk overnight at 4 °C.

Constructs

All primers used in the generation of constructs are shown in supplemental Table 1. Full-length cDNAs of SQN, HSP90.1, and HSP90.2 and the C-terminal ends of HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705), HSP90.2 (amino acids 497–699), HSP90.5 (amino acids 569–780), HSP90.6 (amino acids 592–799), and HSP90.7 (amino acids 603–823) were amplified from Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA using Pfu DNA polymerase. C-terminal constructs of HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 missing the last five amino acids (MEEVD) were amplified from HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 cDNAs, respectively. PCR products were TOPO-cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on pENTR-SQN constructs using site-directed ligase-independent mutagenesis protocol, as described previously (43). The primers used for site-directed ligase-independent mutagenesis are listed in supplemental Table 2. pENTR-HSP90 constructs were subsequently recombined into pDEST17 (His tag) using LR Clonase enzyme mixture (Invitrogen). pENTR-SQN and pENTR-SQN mutant constructs were recombined into either pDEST15 (GST tag) or pEG202 (FLAG tag) using LR Clonase (44). pDEST constructs containing either SQN or HSP90 were transformed into BL21-AI cells. pEG202-SQN and pEG202-SQN point mutant constructs were transfected into Agrobacterium GV3101 and subsequently transformed into A. thaliana by the floral dip method (45).

Protein Expression and Purification

BL21-AI Escherichia coli cells containing pDEST15 and pDEST17 constructs were grown in 500 ml of Luria broth to an A600 of 0.5. GST-SQN and His-HSP90 recombinant proteins were induced with 0.2% (w/v) l-arabinose overnight at 16 °C. Cells were centrifuged at 6000 × g and placed at −80 °C. Cells were resuspended in 30 ml of buffer containing sodium phosphate (pH 7.6), 300 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; sonicated on ice; and centrifuged at 12,500 × g. Soluble proteins from either GST-SQN or His-HSP90 extracts were subsequently added to 500 μl of either glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare) or nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Invitrogen), respectively, and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin or nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose was washed four times with sodium phosphate (pH 7.6), 300 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. GST-SQN proteins were eluted using 10 mm glutathione and 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and His-HSP90 proteins were eluted using sodium phosphate (pH 7.6), 300 mm NaCl, and 250 mm imidazole. All purified proteins were dialyzed against dialysis buffer (100 mm KCl and 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.3)).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were performed as described previously (14) with slight modification. Briefly, purified GST-SQN and His-HSP90 were incubated together in dialysis buffer containing 1 mm dithiothreitol and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 1 h at 4 °C. 50 μl of pre-equilibrated glutathione-Sepharose 4B resin was added, followed by incubation for 2 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed eight times with dialysis buffer containing 1 mm dithiothreitol and 0.2% Triton X-100. SDS-PAGE sample buffer (50 mm Tris (pH 6.8), 6% glycerol, 2% SDS, 100 mm DTT, and 0.01% bromphenol blue) was added to the beads, and samples were heated to 95 °C for 5 min. Protein samples were electrophoresed on either a 10 or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

RESULTS

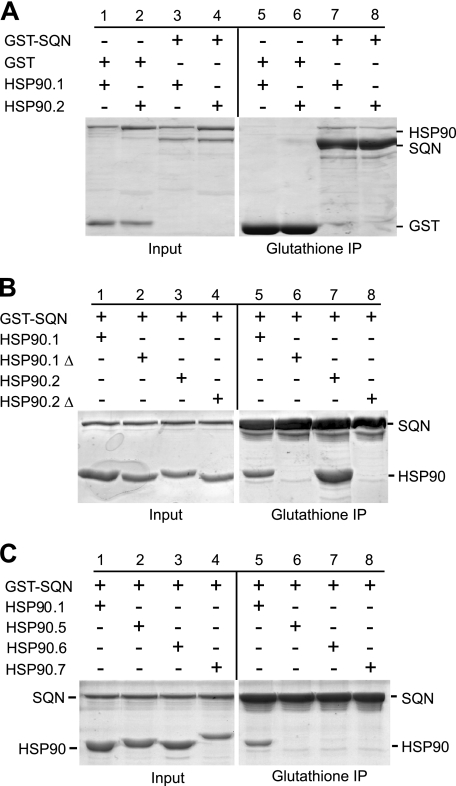

To determine whether SQN interacts with Hsp90 in vitro, GST-tagged SQN and a GST control were incubated with His-tagged HSP90.1 or His-tagged HSP90.2 (Fig. 1A, lanes 1–4), and then precipitated with glutathione-Sepharose resin. HSP90.1 (Fig. 1A, lane 7) and HSP90.2 (lane 8) co-purified with GST-SQN but not with the GST control (lanes 5 and 6), indicating that SQN interacts with HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 in vitro.

FIGURE 1.

SQN binds to cytoplasmic Hsp90 proteins via a conserved C-terminal MEEVD peptide. A, Input, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of GST-tagged SQN incubated with full-length HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 proteins; Glutathione IP, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of proteins bound to glutathione-agarose after washing. B, Input, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of GST-tagged SQN incubated with the C terminus of either HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705) or HSP90.2 (amino acids 497–699) with or without (Δ) the C-terminal MEEVD peptide; Glutathione IP, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of proteins bound to glutathione-agarose after washing. C, Input, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of GST-tagged SQN incubated with the C terminus of HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705), HSP90.5 (amino acids 569–780), HSP90.6 (amino acids 592–799), or HSP90.7 (amino acids 603–823) in the presence of glutathione-agarose; Glutathione IP, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of proteins bound to glutathione-agarose after washing. HSP90.5, HSP90.6, and HSP90.7 are organellar proteins and lack the MEEVD sequence.

In mammals, the last five amino acids of Hsp90 (MEEVD) are absolutely essential for its interaction with CyP40 (13, 14, 46). Molecular modeling suggests that these amino acids contact CyP40 in a pocket formed by the CyP40 TPR domain (13, 14). Given the high similarity between the amino acid sequences of human Hsp90 and A. thaliana HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 (supplemental Fig. 1), we predicted that this interaction is conserved in Arabidopsis. To test this hypothesis, we used a pulldown assay to examine the interaction between GST-tagged SQN and truncated versions of HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705) and HSP90.2 (amino acids 497–699) with or without the C-terminal MEEVD peptide. The truncated peptides used in these experiments correspond to the peptides used for similar studies of mammalian Hsp90 (14). We found that the C termini of HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 co-purified with SQN (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 7) and that this interaction was disrupted by deletion of the MEEVD sequence (lanes 6 and 8). These results suggest that, like mammalian CyP40, SQN contacts Hsp90 via this MEEVD sequence.

The organelle-localized Arabidopsis Hsp90 proteins (HSP90.5, HSP90.6, and HSP90.7) lack the MEEVD sequence and are less similar to cytoplasmic Hsp90 proteins than these proteins are to mammalian Hsp90 (supplemental Fig. 2). To determine whether SQN interacts with these Hsp90 variants, we performed pulldown assays with SQN-GST and C-terminal fragments of HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705; as a positive control), HSP90.5 (amino acids 569–780), HSP90.6 (amino acids 592–799), and HSP90.7 (amino acids 603–823). Whereas the C terminus of HSP90.1 co-purified with SQN (Fig. 1C, lane 5), we observed no interaction between SQN-GST and the C termini of HSP90.5, HSP90.6, and HSP90.7 (lanes 6–8). This observation suggests that SQN interacts solely with the cytoplasmic form of Hsp90 in Arabidopsis and provides additional evidence that this interaction is mediated by the MEEVD sequence of HSP90.

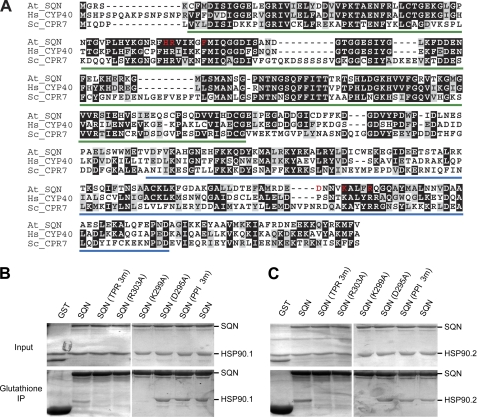

The cyclophilin domain of SQN is 66% identical to the cyclophilin domain of CyP40 and 57% identical to human CyPA, the most extensively studied member of the cyclophilin family of PPIases (Fig. 2A). Although the TPR domains of CyP40 and SQN are less similar, all of the amino acids that have been found to mediate the interaction of CyP40 with Hsp90 are conserved in SQN (13, 14, 46). To study the function of these domains, we used site-directed mutagenesis to convert amino acids that have been implicated in the function of CyPA or CyP40 to alanine (Fig. 2A). GST-tagged proteins containing one or more of these mutations were tested for their ability to interact with the C-terminal portions of HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 in vitro. In addition, FLAG-tagged versions of these mutant proteins were placed under the regulation of the constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and tested for their ability to rescue the sqn-1 phenotype in transgenic plants.

FIGURE 2.

Conserved amino acids within the TPR domain of SQN are necessary for its interaction with HSP90.1 or HSP90.2. A, ClustalW alignment of A. thaliana (At) SQN and Homo sapiens (Hs) and S. cerevisiae (Sc) CyP40 proteins. The cyclophilin (PPIase) and TPR domains are underlined in green and blue, respectively. The amino acids mutated to alanines are marked in red. B and C, Input, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of GST-tagged wild-type and mutant SQN incubated with the C terminus of either HSP90.1 (amino acids 503–705) (B) or HSP90.2 (amino acids 497–699) (C) in the presence of glutathione-agarose; Glutathione IP, Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel of proteins bound to glutathione-agarose after washing. SQN (TPR 3m), SQN protein with substitutions of three amino acids (D295A, K299A, and R303A) within the TPR domain; SQN (PPI 3m), SQN protein with substitutions of three amino acids (H62A, R63A, and F68A) within the PPIase domain. The results from two independent co-immunoprecipitation experiments are shown.

The C termini of HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 co-purified with wild-type SQN and with an SQN protein containing mutations in three evolutionarily conserved residues (H62A, R63A, and F68A) within the predicted substrate-binding site of the cyclophilin domain; these amino acids correspond to His-54, Arg-55, and Phe-60 in mammalian CyPA and are thought to be required for PPIase activity and substrate binding (Fig. 2, B and C) (47–51). In contrast, HSP90.1 and HSP90.2 failed to co-purify with SQN proteins containing alanine substitutions of Lys-299 (K299A) or Arg-303 (R303A), both of which are required for the interaction between mammalian CyP40 and HSP90 (14). As a control, we mutated the adjacent non-conserved Asp-295 (D295A); this mutation had no apparent effect on HSP90 binding (Fig. 2, B and C). Proteins containing the three mutations, D295A, K299A, and R303A (Fig. 2, B and C), did not interact with HSP90.1 or HSP90.2.

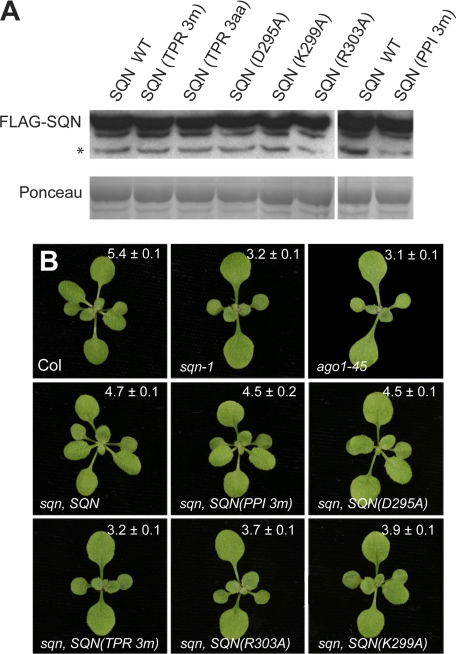

Transgenic sqn-1 plants containing approximately equal levels of wild-type and mutant SQN-FLAG proteins were identified by Western analysis using antibodies against the FLAG epitope (Fig. 3A). The morphological phenotype of sqn-1 is essential identical to that of weak ago1 alleles and is characterized by a reduction in the rate of leaf initiation, an increase in the size of leaves 1 and 2, elongated leaf blades, and the accelerated production of leaves with trichomes on the abaxial surface of the leaf blade (Fig. 3B) (2, 3). These defects were largely corrected by constitutively expressed SQN-FLAG (Fig. 3B). Transgenic plants had a normal leaf shape and a normal rate of leaf initiation and produced abaxial trichomes only slightly earlier than wild-type plants. Plants expressing proteins with the three cyclophilin domain mutations or the D295A mutation were also morphologically normal. In contrast, constructs containing the single amino acid substitution R303A or K299A and the triple D295A/K299A/R303A construct failed to rescue the mutant phenotype of sqn-1. The triple mutant protein had no apparent activity, whereas the R303A and K299A proteins slightly suppressed the phenotype of sqn-1, indicating that these single amino acid substitutions do not completely eliminate the function of SQN. These results suggest that SQN must interact with HSP90 to promote the function of AGO1.

FIGURE 3.

Conserved amino acids within the TPR domain are required for SQN function. A, Western blot of protein extracts from the transgenic lines pictured in B. Membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody. Ponceau staining and a nonspecific band (*) were used as the loading control. B, 18-day-old rosettes of wild-type Columbia (Col), sqn-1, ago1-45, and transgenic sqn-1 plants constitutively expressing wild-type or mutant SQN-FLAG proteins. SQN (TPR 3m) refers to SQN with substitutions of three amino acids (D295A, K299A, and R303A) within the TPR domain; SQN (PPI 3m) refers to SQN with substitutions of three amino acids (H62A, R63A, and F68A) within the PPIase domain. The position of the first leaf with abaxial trichomes is indicated (mean ± S.E., n = 15–20).

DISCUSSION

We took advantage of existing information about the amino acids required for the interaction between mammalian CyP40 and HSP90 (13, 14) to explore the function of CyP40 (SQN) in Arabidopsis. Here, we have shown that SQN binds to Arabidopsis Hsp90 proteins and that the amino acids involved in this interaction are identical in the plant and animal proteins. Additionally, we have shown that the interaction between SQN and Hsp90 is essential for the function of SQN in planta. Previous studies indicate that both SQN and Hsp90 promote the activity of AGO1 (2, 3, 42). Our results suggest that these proteins operate together to accomplish this function.

AGO1 is involved in both siRNA- and miRNA-mediated gene silencing in Arabidopsis (4, 52). Hsp90 promotes both of these functions (42), whereas SQN appears to be required only for miRNA activity (2). One possibility is that SQN recruits miRNAs to Hsp90-bound AGO1, perhaps by interacting with effectors required for miRNA function. An alternative possibility is that SQN regulates AGO1 activity in its Hsp90-bound state. Iki and co-workers (42) found that the passenger strands (siRNA*) in siRNA duplexes are cleaved by AGO1, whereas miRNA* strands are unwound without being cleaved. SQN may facilitate miRNA* unwinding by holding AGO1 in a conformation that prevents the endonucleolytic cleavage of this strand or by recruiting a protein involved in the unwinding of this strand. The in vitro system developed by Iki and co-workers (42) recapitulates the essential features of AGO1 activity and should make it possible to examine the biochemical activity of SQN in detail.

The N-terminal cyclophilin/PPIase domain of SQN is the most highly conserved part of the protein. This domain has PPIase activity in both the yeast (8) and mammalian (7) CyP40 proteins, but the importance of this activity for the in vivo function of CyP40 remains unknown. For example, deletion of the cyclophilin domain in the yeast CyP40 protein Cpr7p does not impair the ability of the protein to rescue the cpr7 mutant phenotype (16). We investigated the function of this domain in SQN by mutating three highly conserved amino acids that structural and mutational studies have suggested are critical for cyclophilin function (47, 48, 53, 54). Mutations of these amino acids severely decrease the binding of CyPA to a proline-containing site in the HIV coat protein (49, 50) and in the B cell surface antigen CD147 and reduce the PPIase activity of CyPA in an in vitro assay employing a tetrapeptide substrate (47, 48). However, the significance of this latter result has recently been called into question by the observation that the R55A mutation (which had the most significant effect in the in vitro assay) does not interfere with the PPIase activity of CyPA when a larger protein is used as a substrate (55). Thus, the actual effect of these mutations on the PPIase activity of cyclophilins is difficult to predict. There is increasing evidence that cyclophilins can affect protein function in ways that do not depend on their PPIase activity (48), so these conserved amino acids may be more important for substrate binding than for enzymatic activity. In any case, it is noteworthy that mutations of these amino acids had no effect on the ability of SQN to bind to HSP90 and did not impair its ability to rescue the sqn-1 mutant phenotype. The most parsimonious interpretation of this result is that these amino acids are dispensable for SQN function. However, this conclusion is difficult to reconcile with the conservation of these amino acids in the vast majority of cyclophilins and FKBPs (56). An alternative possibility is that they contribute to the function of SQN but in ways too subtle to be detected by the morphological criteria used in this study. The biological function of the cyclophilin domain of SQN and other CyP40 proteins is an important problem for future research.

The activity of CyP40 has been characterized primarily in vitro and in yeast. Arabidopsis offers another powerful experimental system for the analysis of this poorly understood protein. Besides the advantages of Arabidopsis for molecular genetic studies, the identification of AGO1 as a likely endogenous substrate of both SQN and Hsp90 is important for two reasons: first, because it represents a biologically meaningful protein with which to study the biochemical functions of SQN and Hsp90 in plants, and second, because AGO1 plays a central role in small RNA metabolism in Arabidopsis, and it is critical to understand how the activity of this protein is regulated. Future biochemical and genetic analyses of the interactions between these three proteins are likely to provide important insights into the role of protein chaperones in miRNA-mediated gene silencing in plants.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM051893 (to R. S. P.) and National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship F32GM084591 from NIGMS (to K. W. E.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2 and Tables 1 and 2.

- miRNA

- microRNA

- PPIase

- peptidyl-proline isomerase

- TPR

- tetratricopeptide repeat

- FKBP

- FK506-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ratajczak T., Ward B. K., Cluning C., Allan R. K. (2009) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1652–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith M. R., Willmann M. R., Wu G., Berardini T. Z., Möller B., Weijers D., Poethig R. S. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 5424–5429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Earley K., Smith M., Weber R., Gregory B., Poethig R. (2010) Silence 1, 15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaucheret H., Vazquez F., Crété P., Bartel D. P. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 1187–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumberger N., Baulcombe D. C. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11928–11933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qi Y., Denli A. M., Hannon G. J. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pirkl F., Buchner J. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 308, 795–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayr C., Richter K., Lilie H., Buchner J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34140–34146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pratt W. B., Toft D. O. (1997) Endocr. Rev. 18, 306–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ratajczak T., Ward B. K., Minchin R. F. (2003) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3, 1348–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ratajczak T., Carrello A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2961–2965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Owens-Grillo J. K., Czar M. J., Hutchison K. A., Hoffmann K., Perdew G. H., Pratt W. B. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13468–13475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taylor P., Dornan J., Carrello A., Minchin R. F., Ratajczak T., Walkinshaw M. D. (2001) Structure 9, 431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ward B. K., Allan R. K., Mok D., Temple S. E., Taylor P., Dornan J., Mark P. J., Shaw D. J., Kumar P., Walkinshaw M. D., Ratajczak T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40799–40809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duina A. A., Chang H. C., Marsh J. A., Lindquist S., Gaber R. F. (1996) Science 274, 1713–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duina A. A., Marsh J. A., Kurtz R. B., Chang H. C., Lindquist S., Gaber R. F. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10819–10822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duina A. A., Marsh J. A., Gaber R. F. (1996) Yeast 12, 943–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berardini T. Z., Bollman K., Sun H., Poethig R. S. (2001) Science 291, 2405–2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galat A. (2003) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3, 1315–1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Romano P., Gray J., Horton P., Luan S. (2005) New Phytol. 166, 753–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Geisler M., Bailly A. (2007) Trends Plant Sci. 12, 465–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meiri D., Breiman A. (2009) Plant J. 59, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geisler M., Girin M., Brandt S., Vincenzetti V., Plaza S., Paris N., Kobae Y., Maeshima M., Billion K., Kolukisaoglu U. H., Schulz B., Martinoia E. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3393–3405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bouchard R., Bailly A., Blakeslee J. J., Oehring S. C., Vincenzetti V., Lee O. R., Paponov I., Palme K., Mancuso S., Murphy A. S., Schulz B., Geisler M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30603–30612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu G., Otegui M. S., Spalding E. P. (2010) Plant Cell 22, 3295–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vittorioso P., Cowling R., Faure J. D., Caboche M., Bellini C. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 3034–3043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smyczynski C., Roudier F., Gissot L., Vaillant E., Grandjean O., Morin H., Masson T., Bellec Y., Geelen D., Faure J. D. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25475–25484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamphausen T., Fanghänel J., Neumann D., Schulz B., Rahfeld J. U. (2002) Plant J. 32, 263–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Young J. C., Moarefi I., Hartl F. U. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154, 267–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Picard D. (2002) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1640–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sangster T. A., Bahrami A., Wilczek A., Watanabe E., Schellenberg K., McLellan C., Kelley A., Kong S. W., Queitsch C., Lindquist S. (2007) PLoS ONE 2, e648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Krishna P., Gloor G. (2001) Cell Stress Chaperones 6, 238–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cao D., Froehlich J. E., Zhang H., Cheng C. L. (2003) Plant J. 33, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prassinos C., Haralampidis K., Milioni D., Samakovli D., Krambis K., Hatzopoulos P. (2008) Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 323–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ishiguro S., Watanabe Y., Ito N., Nonaka H., Takeda N., Sakai T., Kanaya H., Okada K. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 898–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hubert D. A., Tornero P., Belkhadir Y., Krishna P., Takahashi A., Shirasu K., Dangl J. L. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5679–5689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Landthaler M., Gaidatzis D., Rothballer A., Chen P. Y., Soll S. J., Dinic L., Ojo T., Hafner M., Zavolan M., Tuschl T. (2008) RNA 14, 2580–2596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu J., Carmell M. A., Rivas F. V., Marsden C. G., Thomson J. M., Song J. J., Hammond S. M., Joshua-Tor L., Hannon G. J. (2004) Science 305, 1437–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maniataki E., Mourelatos Z. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 2979–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnston M., Geoffroy M. C., Sobala A., Hay R., Hutvagner G. (2010) Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 1462–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iwasaki S., Kobayashi M., Yoda M., Sakaguchi Y., Katsuma S., Suzuki T., Tomari Y. (2010) Mol. Cell 39, 292–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Iki T., Yoshikawa M., Nishikiori M., Jaudal M. C., Matsumoto-Yokoyama E., Mitsuhara I., Meshi T., Ishikawa M. (2010) Mol. Cell 39, 282–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chiu J., March P. E., Lee R., Tillett D. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, e174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Earley K. W., Haag J. R., Pontes O., Opper K., Juehne T., Song K., Pikaard C. S. (2006) Plant J. 45, 616–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998) Plant J. 16, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carrello A., Ingley E., Minchin R. F., Tsai S., Ratajczak T. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2682–2689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zydowsky L. D., Etzkorn F. A., Chang H. Y., Ferguson S. B., Stolz L. A., Ho S. I., Walsh C. T. (1992) Protein Sci. 1, 1092–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davis T. L., Walker J. R., Campagna-Slater V., Finerty P. J., Paramanathan R., Bernstein G., MacKenzie F., Tempel W., Ouyang H., Lee W. H., Eisenmesser E. Z., Dhe-Paganon S. (2010) PLoS Biol. 8, e1000439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Braaten D., Ansari H., Luban J. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 2107–2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dorfman T., Göttlinger H. G. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 5751–5757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yurchenko V., Zybarth G., O'Connor M., Dai W. W., Franchin G., Hao T., Guo H., Hung H. C., Toole B., Gallay P., Sherry B., Bukrinsky M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22959–22965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fagard M., Boutet S., Morel J. B., Bellini C., Vaucheret H. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11650–11654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Howard B. R., Vajdos F. F., Li S., Sundquist W. I., Hill C. P. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Huai Q., Kim H. Y., Liu Y., Zhao Y., Mondragon A., Liu J. O., Ke H. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12037–12042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Moparthi S. B., Hammarström P., Carlsson U. (2009) Protein Sci. 18, 475–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fanghänel J., Fischer G. (2004) Front. Biosci. 9, 3453–3478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.