Abstract

Recently, we have demonstrated a predominant association of Rad26p with the coding sequences but not promoters of several GAL genes following transcriptional induction. Here, we show that the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer at the coding sequences of these genes is not altered following transcriptional induction in the absence of Rad26p. A histone H2A–H2B dimer-enriched chromatin in Δrad26 is correlated to decreased association of RNA polymerase II with the active coding sequences (and hence transcription). However, the reduced association of RNA polymerase II with the active coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p is not due to the defect in formation of transcription complex at the promoter. Thus, Rad26p regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer, which is correlated to the association of elongating RNA polymerase II with active GAL genes. Similar results are also found at other inducible non-GAL genes. Collectively, our results define a new role of Rad26p in orchestrating chromatin structure and hence transcription in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

In humans, mutations in the CSA (Cockayne syndrome group A) and CSB (Cockayne syndrome group B) genes are strongly correlated to ∼90% Cockayne syndrome (CS) patients (1). CS is associated with severe growth retardation, progressive neurological dysfunction, mental retardation, cataracts, hearing and vision impairments, retinal pigmentation, and mild sun sensitivity (1–6). The average age of survival of the CS patients is ∼12 years (6). These patients are unable to preferentially repair DNA lesions in the transcribed strand of active gene (7) [known as transcription-coupled repair, TCR (8)], implicating CSA and CSB in DNA repair. Additionally, CSB facilitates transcriptional elongation (9). Thus, the defects in DNA repair and/or transcriptional elongation caused by mutations in the CS genes appear to be associated with the above clinical symptoms of the CS patients.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, RAD26 is the homolog of CSB (10). Null mutation of RAD26 causes a defect in TCR (10). RAD26, like CSB, also promotes transcriptional elongation (11,12). Consistently, we have recently demonstrated that Rad26p is predominantly associated with the coding sequences but not promoters of several GAL genes, namely GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 under inducible conditions (13). Similarly, we have also demonstrated that Rad26p is associated with the coding sequences of other active genes such as INO1 and RPS5 (13). We have further shown that the association of Rad26p with active coding sequence is dependent on methylation of K36 (lysine 36), but not K4 of histone H3 (13). Thus, Rad26p associates with the active coding sequence, and regulates transcription.

The proteins encoded by RAD26 and CSB exhibit extensive homology to a large number of proteins of the SWI2/SNF2 family of ATPases with DNA-dependent ATPase activity (14–17). The SWI2/SNF2 family members contain several conserved domains including ATPases and helicases, and function in diverse DNA-transacting processes such as transcription, recombination and different DNA repair processes (16,17). However, purified Rad26p exhibits DNA-dependent ATPase, but no apparent DNA helicase activity (14). Previous studies have implicated Rad26p or its human homolog in chromatin remodeling (18,19). Like SWI/SNF, Rad26p may affect histone–DNA contacts by disrupting the rotational phasing of DNA (20–22) or changing the local DNA topology (18,23,24). This activity may enhance the accessibility of repair factors to DNA lesions or passage of RNA polymerase II through chromatin in the coding sequence to promote transcriptional elongation. However, how Rad26p or CSB regulates the chromatin structure is not yet clearly understood. Here, using formaldehyde-based in vivo cross-linking and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), mutational and transcriptional analyses, we have elucidated the role of Rad26p in regulation of chromatin structure. Our results reveal that Rad26p regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer at the active genes, and hence chromatin structure and transcription in vivo, as presented below.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The plasmid pRS406 (25) was used in the PCR-based disruption of RAD26 and coding sequence of GAL1. The plasmids, pFA6a-13Myc-KanMX6 and pFA6a-3HA-His3MX6 (26), were used for genomic tagging of the proteins of interest by myc and HA epitopes, respectively.

Strains

The yeast (S. cerevisiae) strain bearing Flag-tagged histone H2B (YTT31) was obtained from the Osley laboratory (27). The strain YTT31 was derived from JKM179 (FlagHTB1::LEU2 in JKM179). The genotype of JKM179 is hoΔ MATα hmlΔ::ADE1 hmrΔ::ADE1 ade1-100 leu2-3,112lys5 trp1::hisG′’ ura3-52 ade3::GAL::HO (28). The strain, SMY15, was generated by deleting RAD26 from the YTT31 strain. The yeast strains, MSY143 (Δswi2) and MSY104 (Δasf1), and their isogenic wild-type equivalent (FY406) were obtained from the Struhl laboratory (29–31). The RAD26 gene was deleted from the MSY143 (Δswi2) and MSY104 (Δasf1) strains to generate PCY18 (Δswi2Δrad26) and SMY21 (Δasf1Δrad26) strains, respectively. The HA epitope tag was added genomically to different locations toward the C-terminal of Rad26p using the pFA6a-3HA-KanMX6 plasmid to generate the SMY23 (Rad26p-920), SMY22 (Rad26p-758), PCY20 (Rad26p-660) and PCY12 (Rad26p-600) strains. The yeast strain harboring null mutation in RAD26 and its isogenic wild-type equivalent were obtained from yeast deletion library of the Shilatifard laboratory. In these strains, the coding sequence of GAL1 was deleted to generate PCY27 and PCY28.

Growth media

For transcriptional induction of GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10, yeast strains were initially grown in YPR (yeast extract, peptone plus 2% raffinose) up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG (yeast extract, peptone plus 2% galactose) for different induction time periods prior to formaldehyde-based in vivo cross-linking. For long induction, yeast cells were continuously grown in YPG up to an OD600 of 1.0 prior to cross-linking. For studies at RPS5, yeast cells were grown in YPD (yeast extract, peptone plus 2% dextrose) up to an OD600 of 1.0 before formaldehyde-based in vivo cross-linking. For the induction of INO1, yeast cells were initially grown in synthetic complete medium (yeast nitrogen base, complete amino acid mixture and 2% dextrose) containing 100 µM inositol at 30°C up to an OD600 of 0.45, and then switched to the same medium without inositol for 4 h prior to cross-linking. For studies at the CTT1 and STL1 genes, yeast cells were initially grown in synthetic complete medium up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then were induced by 0.45 M NaCl for 3 and 7 min prior to cross-linking.

ChIP assay

The ChIP assay was performed as described previously (32–35). Briefly, yeast cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde, collected and resuspended in lysis buffer. Following sonication, cell lysate (400 µl lysate from 50 ml of yeast culture) was precleared by centrifugation, and then 100 µl lysate was used for each immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitated protein–DNA complexes were treated with proteinase K, the cross-links were reversed and DNA was purified. Immunoprecipitated DNA was dissolved in 20 µl TE 8.0 (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0 and 1 mM EDTA), and 1 µl of immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR. PCR reactions contained [α-32P]dATP (2.5 µCi for 25 µl reaction), and the PCR products were detected by autoradiography after separation on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. As a control, ‘input’ DNA was isolated from 5 µl lysate without going through the immunoprecipitation step, and dissolved in 100 µl TE 8.0. To compare PCR signal arising from the immunoprecipitated DNA with the input DNA, 1 µl of input DNA was used in the PCR analysis.

The association of Rad26p was analyzed by modified ChIP assay as described in our recent publication (13). For ChIP analysis of histone H3, we modified the above ChIP protocol as follows (34,36,37). Lysate of 800 μl was prepared from 100 ml of yeast culture. Lysate of 300 μl was used for each immunoprecipitation [using 3 μl of anti-histone H3 antibody from Abcam (Ab-1791) and 100 μl of protein A/G plus agarose beads from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.], and immunoprecipitated DNA sample was dissolved in 10 μl of TE 8.0 of which 1 μl was used in PCR analysis. In parallel, PCR for input DNA was performed using 1 μl of DNA that was prepared by dissolving purified DNA from 5 μl of lysate in 100 μl of TE 8.0.

The primer pairs used for PCR analysis were as follows:

| GAL1(UAS): | 5′-CGCTTAACTGCTCATTGCTATATTG-3′ |

| 5′-TTGTTCGGAGCAGTGCGGCGC-3′ | |

| GAL1 (Core): | 5′-ATAGGATGATAATGCGATTAGTTTTTTAGCCTT-3′ |

| 5′-GAAAATGTTGAAAGTATTAGTTAAAGTGGTTATGCA-3′ | |

| GAL1 (ORF): | 5′-CAGTGGATTGTCTTCTTCGGCCGC-3′ |

| 5′-GGCAGCCTGATCCATACCGCCATT-3′ | |

| GAL1 (ORF1): | 5′-GTGAGGAAGATCATGCTCTATACG-3′ |

| 5′-GGCGGTTTCAAACTTGTTAGATAC-3′ | |

| GAL1 (ORF2): | 5′-CAGAGGGCTAAGCATGTGTATTCT-3′ |

| 5′-GTCAATCTCTGGACAAGAACATTC-3′ | |

| GAL7 (Core): | 5′-CTATGTTCAGTTAGTTTGGCTAGC-3′ |

| 5′-TTGATGCTCTGCATAATAATGCCC-3′ | |

| GAL7 (ORF): | 5′-AAAGTGCAATCTGTGAGAGGCAATT-3′ |

| 5′-TTTTCTCTTGCTTCTCTGGAGAGAT-3′ | |

| GAL10 (Core): | 5′-GCTAAGATAATGGGGCTCTTTACAT-3′ |

| 5′-TTTCACTTTGTAACTGAGCTGTCAT-3′ | |

| GAL10 (ORF): | 5′-TTAATGCGAATCATAGTAGTATCGG-3′ |

| 5′-TTACCAATAGATCACCTGGAAATTC-3′ | |

| RPS5 (Core): | 5′-GGCCAACTTCTACGCTCACGTTAG-3′ |

| 5′-CGGTGTCAGACATCTTTGGAATGGTC-3′ | |

| RPS5 (ORF): | 5′-AGGCTCAATGTCCAATCATTGAAAG-3′ |

| 5′-CAACAACTTGGATTGGGTTTTGGTC-3′ | |

| INO1 (ORF): | 5′-TGCCCATGGTTAGCCCAAACGACTT-3′ |

| 5′-AAGGAAGAGGCTTCACCAAGGACA-3′ | |

| CTT1 (Core): | 5′-GGCTGCAGGCTAGCCTAGCCGAT-3′ |

| 5′-GGAATAGAGGTAAAGCAACGACTTC-3′ | |

| CTT1 (ORF): | 5′-TGCTGAACTGTCAGGCTCCCACC-3′ |

| 5′-GGGGAATTCCTTGTGTGGCCATATT-3′ | |

| STL1 (Core): | 5′-ACCTTTGATAGGGCTTTCATTGGGGC-3′ |

| 5′-TCTAAGGCCAAGCAGCGTTGAAG-3′ | |

| STL1 (ORF): | 5′-ACACTAGACGCGGATCCAAAT-3′ |

| 5′-AGCGTTACAACCAGTAAATTGCTGG-3′ |

Autoradiograms were scanned and quantitated by the National Institutes of Health image 1.62 program. Immunoprecipitated (IP) DNAs were quantitated as the ratio of IP to input. For eviction analysis of histones H2B and H3 following transcriptional induction, the ChIP signal of histone H2B or histone H3 at 0 min of induction was set to 100 for both the wild-type and mutant strains. The ChIP signals at later induction time periods were normalized with respect to 100. UAS, upstream activating sequence; Core, core promoter; and ORF, open reading frame.

Total mRNA preparation

The total mRNA was prepared from yeast cell culture as described by Peterson et al. (38). Briefly, 10 ml yeast culture of a total OD600 of 1.0 in YPD was harvested, and then was suspended in 100 µl RNA preparation buffer (500 mM NaCl, 200 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM Na2EDTA and 1% SDS) along with 100 µl phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol and 100 µl volume-equivalent of glass beads (acid washed; Sigma). Subsequently, yeast cell suspension was vortexed with a maximum speed (10 in VWR mini-vortexer; Cat. No. 58816-121) for 5 times (30 s each). Cells suspension was put in ice for 30 s between pulses. After vortexing, 150 µl RNA preparation buffer and 150 µl phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol were added to yeast cell suspension followed by vortexing for 15 s with a maximum speed on VWR mini-vortexer. The aqueous phase was collected following 5 min centrifugation at a maximum speed in microcentrifuge machine. The total mRNA was isolated from aqueous phase by ethanol precipitation.

Primer extension analysis

Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (35). The primers used for analysis of GAL1 and RPS5 mRNAs were as follows

| GAL1: | 5′-CCTTGACGTTACCTTGACGTTAAAGTATAGAGG-3′ |

| RPS5: | 5′-GACTGGGGTGAATTCTTCAACAACTTC-3′ |

Reverse transcriptase–PCR analysis

Reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT–PCR) analysis was performed according to the standard protocols (39). Briefly, total mRNA was prepared from 10 ml yeast culture grown to an OD600 of 1.0. Ten micrograms of total mRNA was used in the reverse transcription assay. mRNA was treated with RNase-free DNase (M610A, Promega) and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using oligo(dT) as described in the protocol supplied by Promega (A3800, Promega). PCR was performed using synthesized first strand as template and the primer pairs targeted to the GAL1, GAL7, GAL10 and RPS5 ORFs. RT–PCR products were separated by 2.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The primer pairs used in the PCR analysis were as follows:

GAL1: 5′-CAGAGGGCTAAGCATGTGTATTCT-3′

5′-GTCAATCTCTGGACAAGAACATTC-3′

GAL7: 5′-TGAGACCTTGGTCATTTCAAAGAAG-3′

5′-ATGGATACCCATTGAGTATGGGAAA-3′

GAL10: 5′-TTAATGCGAATCATAGTAGTATCGG-3′

5′-TTACCAATAGATCACCTGGAAATTC-3′

RPS5: 5′-AGGCTCAATGTCCAATCATTGAAAG-3′

5′-CAACAACTTGGATTGGGTTTTGGTC-3′

Growth analysis in solid and liquid media

The growth of various mutant and wild-type cells were analyzed on plates containing solid YPD, YPG and YPG plus antimycin (1 µg/ml) after 4 days. Yeast cells were initially grown in YPD up to an OD600 of 1.0, and then were spotted on different solid growth media following serial dilution. Yeast cells were grown at 30°C, and photographed after 4 days. For analysis of growth in liquid medium, wild-type and mutant cells were initially grown in YPD up to an OD600 of 0.2, which is then switched to YPG at 30°C, and subsequently, OD600 was measured at different times.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have recently demonstrated that Rad26p associates with the active coding sequence in histone H3 K36, but not histone H3 K4, methylation-dependent manner (13). However, we find that the absence of Elp3p (which possesses histone acetyltransferase activity, and is an integral component of the elongator complex) or Eaf3p (a specific component of the Rpd3S histone deacetylase complex) does not alter the recruitment of Rad26p (Supplementary Figure S1), implicating the association of Rad26p with active coding sequence in a histone acetylation-independent manner. Thus, Rad26p associates with the chromatin of active coding sequence, and elongating RNA polymerase II and Set2p or histone H3 K36 methylation play crucial roles in such association (13). Consistent with our in vivo results, Nag et al. (40) have also implicated genetic interaction between Rad26p and histone H4. Furthermore, previous biochemical studies (41) have demonstrated the association of Rad26p with chromatin. Like Rad26p, its human homolog has also been shown to interact with chromatin (18).

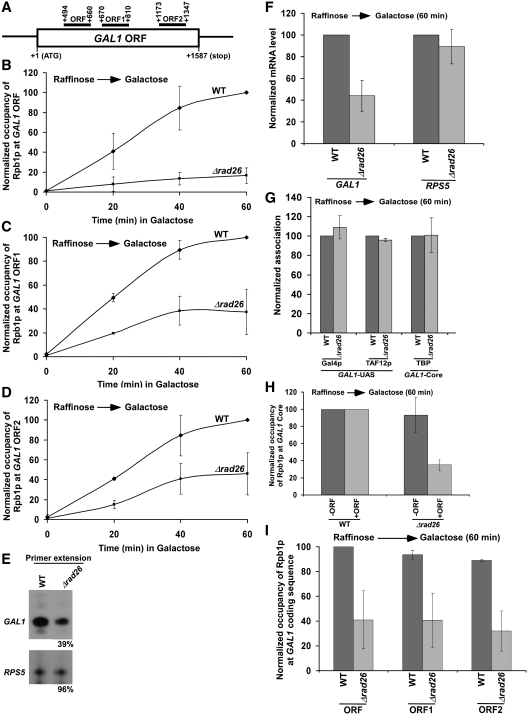

Since Rad26p associates with active coding sequences (13) and enhances transcriptional elongation (11,12), the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence is likely to be decreased in the absence of Rad26p. To test this possibility, we analyzed the level of RNA polymerase II at different locations (Figure 1A) of the GAL1 coding sequence following transcriptional induction in YPG (inducing) in the Δrad26 strain and its isogenic wild-type equivalent. We find that Rad26p promotes the association of Rpb1p (the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II) with the GAL1 coding sequence following transcriptional induction (Figure 1A–D). However, the global level of Rpb1p is not altered in the Δrad26 strain (data not shown). Consistent with the ChIP results, our primer extension analysis reveals that the synthesis of GAL1 mRNA is significantly decreased in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 1E). The levels of RPS5 mRNA in the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were monitored as an internal control, since Rad26p does not regulate the association of RNA polymerase II with the constitutively active RPS5 gene (Figure 2F). Our RT–PCR analysis also reveals a decreased level of GAL1 mRNA in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 1F). Together, our results demonstrate that Rad26p enhances the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence following induction, hence promoting transcriptional elongation. However, such an enhanced association of RNA polymerase II with the active GAL1 coding sequence could be an indirect result of the stimulation of transcription complex assembly at the promoter by Rad26p. To test this possibility, we analyzed the recruitment of TBP as a representative component of the preinitiation complex (PIC) at the GAL1 core promoter in the presence and absence of Rad26p. We find that Rad26p does not regulate the recruitment of TBP to the GAL1 core promoter (Figure 1G). Furthermore, we show that the recruitment of the factors such as Gal4p (activator) and SAGA co-activator (TAF12p) upstream of the PIC formation at the GAL1 promoter is not altered in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 1G). Collectively, these results support that Rad26p promotes the association of elongating RNA polymerase II independently of the transcription complex assembly at the promoter following transcriptional induction. Consistently, Rad26p is recruited to the coding sequence, but not promoter, of GAL1 under inducible conditions (13). Although Rad26p does not promote the formation of transcription complex at the promoter, we observed a reduced association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 core promoter following transcriptional induction in YPG (Figure 1H). Since the primer pair targeted to the GAL1 core promoter in the ChIP assay is located very close to its coding sequence and the average size of the sonicated DNA fragments is ∼500 bp (13), it is expected to observe a change in RNA polymerase II association with the GAL1 core promoter if it is altered at the coding sequence. Thus, the decreased recruitment of RNA polymerase II at the GAL1 core promoter in the absence of Rad26p is likely to be an indirect effect of reduced association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain. To confirm it further, we deleted the coding sequence of the GAL1 gene, and then analyzed the association of RNA polymerase II with the core promoter in the wild-type and Δrad26 strains following transcriptional induction in YPG. We find that the absence of Rad26p does not alter the association of RNA polymerase II with GAL1 core promoter when the coding sequence is deleted (Figure 1H). Taken together, our data support that Rad26p does not regulate transcriptional initiation, but rather transcriptional elongation, consistent with previous studies (11,12).

Figure 1.

Rad26p promotes the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence following transcriptional induction. (A) The schematic diagram of the GAL1 coding sequence or ORF with the PCR amplification regions (ORF, ORF1 and ORF2) in the ChIP assay. The numbers are presented with respect to the position of the first nucleotide of the initiation codon (+1). (B–D) Analysis of Rpb1p (the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II) association with the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain and its isogenic wild-type equivalent. The wild-type and Δrad26 strains were first grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then shifted to YPG for different periods of induction prior to formaldehyde-based in vivo cross-linking. Immunoprecipitation was performed using the mouse monoclonal antibody 8WG16 (Covance) against Rpb1p-CTD (carboxy terminal domain). The specific primer pair targeted to the different locations in the GAL1 coding sequence was used for PCR analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA samples. The ChIP signal is the ratio of immunoprecipitate over the input in the autoradiogram. The maximum ChIP signal in the wild-type strain was set to 100, and other ChIP signals in the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were normalized with respect to 100. The normalized ChIP signals (represented as normalized occupancy) were plotted as a function of induction times. (E) Primer extension analysis. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG for 60 min. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed by primer extension. (F) RT-PCR analysis. Yeast strains were grown as in panel E. Total RNA was prepared and analyzed for transcription. Oligo(dT) primer was used for cDNA synthesis. (G) Rad26p does not regulate the formation of transcription complex at the GAL1 promoter. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown as in panel E prior to formaldehyde-based in vivo cross-linking. Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-Gal4p (RK5C1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-TAF12p (obtained from the laboratory of Michael R. Green) and anti-TBP (obtained from the laboratory of Michael R. Green) antibodies against Gal4p, TAF12p and TBP, respectively. (H) Regulation of Rpb1p occupancy at the GAL1 core promoter by Rad26p in the presence and absence of the coding sequence. Wild-type and mutant strains were grown as in panel E prior to cross-linking. +ORF, with open reading frame; and –ORF, without open reading frame. (I) Analysis of Rpb1p occupancy at different regions of the GAL1 coding sequence following 60 min transcriptional induction in YPG. The maximum ChIP signal was set to 100, and other ChIP signals were normalized with respect to 100.

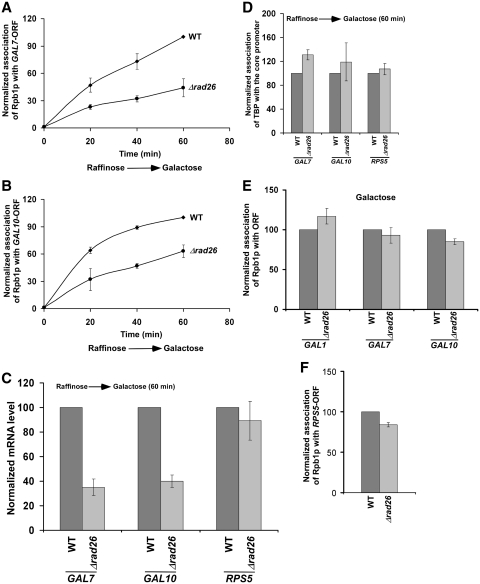

Figure 2.

Rad26p promotes the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequence following transcriptional induction. (A and B) Analysis of Rpb1p association with the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences in the Δrad26 strain and its isogenic wild-type equivalent. The yeast strains were grown and cross-linked as in Figure 1B. The specific primer pairs targeted to the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences were used for PCR analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA samples. (C) RT-PCR analysis. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown as in Figure 1E. (D) Rad26p does not regulate the recruitment of TBP to the GAL7, GAL10 and RPS5 core promoters. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown as in Figure 1E prior to cross-linking. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 1G. The specific primers targeted to the core promoters were used for PCR analysis of the immunoprecipitated DNA samples. (E) The steady-state levels of RNA polymerase II association with the coding sequences of GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 are not altered in the absence of Rad26p. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were continuously grown in YPG prior to cross-linking. (F) Rad26p does not alter the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence of a constitutively active gene, RPS5. Yeast strains were grown in YPD up to an OD600 of 1.0 prior to cross-linking. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR, using the primer pair targeted to the RPS5 coding sequence.

The reduced association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain could be due to the fact that RNA polymerase II is paused at or fallen off the 5′-end of the GAL1 coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p. To test these possibilities, we next analyzed the relative occupancy of RNA polymerase II at different locations of the GAL1 coding sequence (ORF, ORF1 and ORF2) in the Δrad26 mutant and its isogenic wild-type equivalent. We find that the association of RNA polymerase II throughout the GAL1 coding sequence is significantly decreased in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 1H and I). If RNA polymerase II is paused at the 5′-end of the GAL1 coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p, we would have observed a significant increase in RNA polymerase II occupancy toward the 5′-end of the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain as compared with the wild-type equivalent. Such a paused-RNA polymerase II would have further led to a decrease in the occupancy of RNA polymerase II toward the 3′-end of the GAL1 coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p. However, we observed a uniform decrease in the occupancy of RNA polymerase II throughout the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 1H and I), supporting that Rad26p is not involved in RNA polymerase II pausing. Furthermore, our results rule out the possibility that RNA polymerase II has fallen off the GAL1 coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p. If this happens, we would have observed a dramatic decrease in the occupancy of RNA polymerase II toward the 3′-end of the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain. However, our results reveal that the association of RNA polymerase II is uniformly decreased throughout the GAL1 coding sequence (Figure 1H and I). These results support that RNA polymerase II moves slowly through the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26 strain.

Next, we asked whether Rad26p also promotes the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequences of other GAL genes following transcriptional induction. To address this question, we analyzed the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequences of GAL7 and GAL10 in the presence and absence of Rad26p. We find that Rad26p promotes the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences following induction in YPG (Figure 2A and B), and consequently, enhances the synthesis of mRNA (Figure 2C). However, the recruitment of TBP to the core promoters of these genes is not altered in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 2D). Thus, like the results at GAL1, Rad26p enhances the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences following induction, hence promoting transcriptional elongation. Consistently, Rad26p is associated with the coding sequences, but not promoters, of these genes under inducible conditions (13).

To determine whether RNA polymerase II association could reach the wild-type level if given enough time to attain the steady state, we analyzed the levels of RNA polymerase II at the GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences following continuous induction in YPG. We find that the steady state levels of RNA polymerase II association with the GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences are not altered in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 2E). Thus, Rad26p promotes the initial association of RNA polymerase II with the active coding sequence. However, when the steady state is reached, the alteration of RNA polymerase II association is not observed in the absence of Rad26p. Thus, it is anticipated that the defect in the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence of the constitutively active gene would not be observed in the Δrad26 strain. Indeed, the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence of a constitutively active gene, RPS5, is not altered in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 2F). Furthermore, the recruitment of TBP to the RPS5 core promoter remains invariant in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 2D).

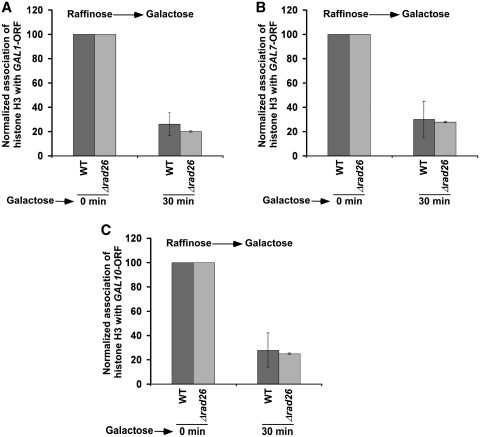

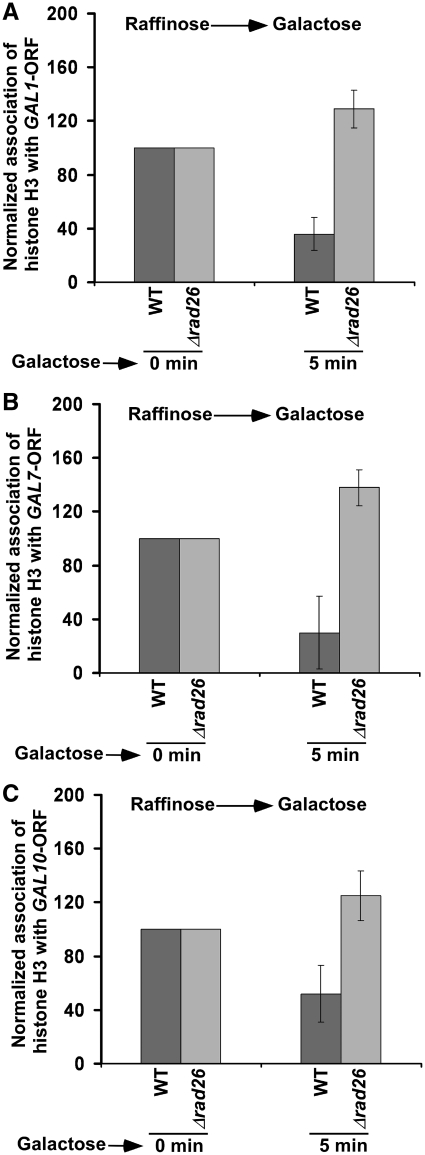

Next, we asked how Rad26p enhances the association of RNA polymerase II with active coding sequence. We hypothesized that Rad26p might be facilitating the eviction of histone H3–H4 tetramer and H2A–H2B dimer during transcriptional induction, hence promoting the passage of RNA polymerase II through the coding sequence. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the level of histone H3 (as a representative component of histone H3–H4 tetramer) at the coding sequence of GAL1 prior to and following 30 min induction in YPG. We find that histone H3 is evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence following induction in the wild-type cells (Figure 3A). This is expected, since histone H3 is evicted during transcription (37,42–46). However, the absence of Rad26p does not alter the eviction of histone H3 from the GAL1 coding sequence following 30 min transcriptional induction (Figure 3A). Thus, Rad26p does not appear to affect the eviction of histone H3 from the GAL1 coding sequence during transcriptional induction. Likewise, we find that the eviction of histone H3 from the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences is not altered in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 3B and C). Together, these results indicate that Rad26p does not alter the eviction of histone H3–H4 tetramer from the GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences following 30 min transcriptional induction. Thus, the reduced association of RNA polymerase II with the active GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences in the Δrad26 strain does not appear to be due to an impaired eviction of histone H3–H4 tetramer.

Figure 3.

Rad26p does not alter the eviction of histone H3 from the coding sequences of GAL1 (A), GAL7 (B) and GAL10 (C) upon transcriptional induction. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG for 30 min prior to formaldehyde treatment. Immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-histone H3 antibody (Abcam; Ab-1791) against histone H3. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR, using the primer pairs targeted to the coding sequences of GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10.

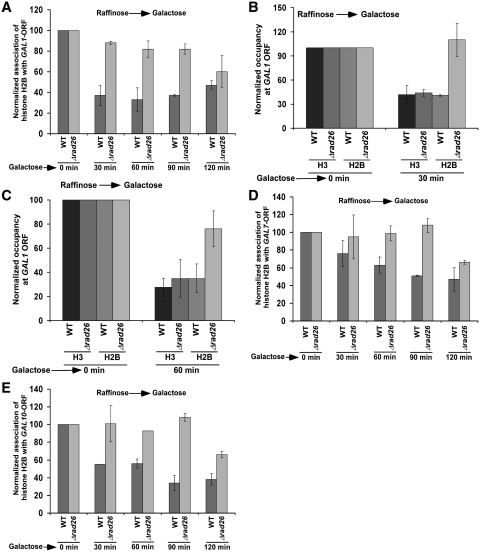

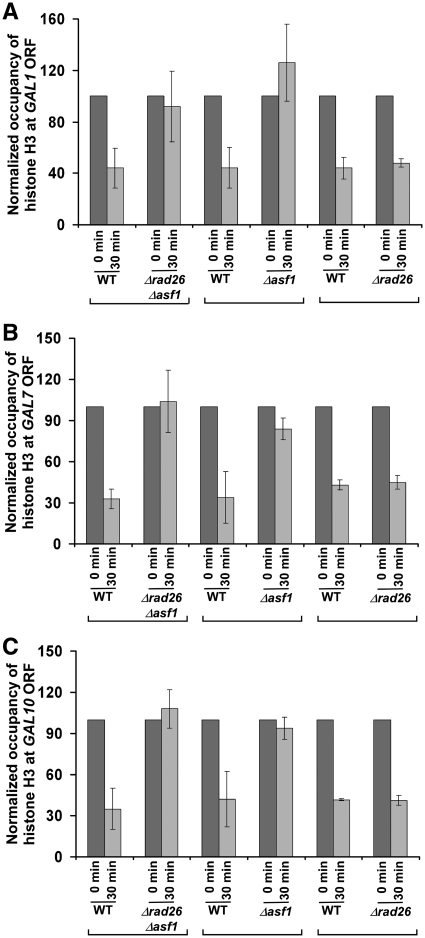

Previous studies (47–49) have implicated the loss of histone H2A–H2B dimer in impairing the formation of higher order chromatin structures from polynucleosomes for facilitating the interaction of protein–protein complexes with DNA to promote transcription. Thus, it is quite likely that Rad26p enhances the association of RNA polymerase II with the active coding sequence by promoting the eviction of histone H2A–H2B dimer. Furthermore, the loss of histone H2A–H2B dimer has been suggested to be relevant for the function of RNA polymerase II on the chromatin template (47), since dimer removal acts as the first step in the complete removal of octamer (50,51). Thus, to test the hypothesis that Rad26p facilitates the eviction of histone H2A–H2B dimer, we analyzed the level of histone H2B (as a representative component of histone H2A–H2B dimer) at the GAL1 coding sequence in the presence and absence of Rad26p following induction in YPG. As expected, histone H2B is evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence following transcriptional induction in the wild-type cells (Figure 4A), consistent with previous studies (37,42–46). Intriguingly, the occupancy of histone H2B is not altered till 90 min following transcriptional induction in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 4A). Thus, we observe histone H2A–H2B dimer-enriched chromatin at the GAL1 coding sequence in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 4A–C; Figure 8E). As a result, the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence is decreased in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 1A–D). Similar to the results at GAL1, we find that the occupancy of histone H2B at the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences is not altered in the Δrad26 strain (Figure 4D and E). These results support that Rad26p facilitates the eviction of histone H2A–H2B dimer from the coding sequences of active GAL genes. Interestingly, even when histone H3 is evicted normally from the GAL coding sequences following 30 min transcriptional induction, the occupancy of histone H2B is not significantly altered in the Δrad26 strain (Figures 3 and 4). However, previous studies have demonstrated that histone H2A–H2B dimer is assembled on histone H3–H4 tetramer to form a nucleosome (52–54). So, how is histone H3 evicted normally from the GAL coding sequences in the absence of Rad26p following 30 min transcriptional induction, whereas the occupancy of histone H2B is not altered in the Δrad26 strain? It is quite likely that a relatively reduced level of histone H2B eviction in the Δrad26 strain may slow down the eviction of histone H3 immediately following transcriptional induction. However, later on, histone H3 is evicted with the help of histone H3 chaperone, Asf1p, as previous studies (29,55) have implicated the accumulation of Asf1p at GAL1 following transcriptional induction to promote the eviction of histone H3. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the levels of histones H3 at the coding sequences of GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 in the wild-type and Δrad26 strains immediately following transcriptional induction. We find that histone H3 is not efficiently evicted from the GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences following 5 min transcriptional induction in the Δrad26 strain in comparison to the wild-type equivalent (Figure 5A–C). However, following 30 min induction, histone H3 is evicted in the Δrad26 strain, similar to the wild-type equivalent (Figure 3). When both Rad26p and Asf1p are absent, histone H3 is not evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence following 30 min transcriptional induction (Figure 6A). Likewise, histone H3 is not evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δasf1 strain (Figure 6A), consistent with previous studies (29,55). Similar results are also found at GAL7 and GAL10 (Figure 6B and C). Thus, the delayed eviction of histone H2B in the absence of Rad26p slows down histone H3 eviction immediately following transcriptional induction, but later on, histone H3 is evicted. However, the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer is not altered in the Δrad26 strain. These observations support the existence of a sufficiently high level of histone H2A–H2B dimer, even when a significant amount of histone H3–H4 tetramer is evicted in the Δrad26 strain. Consistent with our results, Andrews et al. (56) have also recently reported an atypical histone H2A–H2B dimer-enriched chromatin at several GAL genes in the absence of Nap1p, a histone chaperone. Furthermore, histone H2A–H2B dimer has been shown to form a stable complex with DNA in the absence of histone H3–H4 tetramer (56).

Figure 4.

Rad26p promotes the loss of histone H2B from the coding sequences of GAL1, GAL7 and GAL10 following transcriptional induction. (A) Regulation of histone H2B occupancy at the GAL1 coding sequence by Rad26p. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains carrying Flag-tagged histone H2B were grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG for different periods of transcriptional induction prior to formaldehyde treatment. Immunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-Flag antibody (Sigma; F1804) against Flag-tagged histone H2B. (B and C) Analysis of the occupancies of histone H3 and Flag-tagged histone H2B at the GAL1 coding sequence following 30 and 60 min transcriptional induction in YPG in the Δrad26 and wild-type strains. (D and E) Regulation of histone H2B occupancy at the GAL7 and GAL10 coding sequences by Rad26p following transcriptional induction.

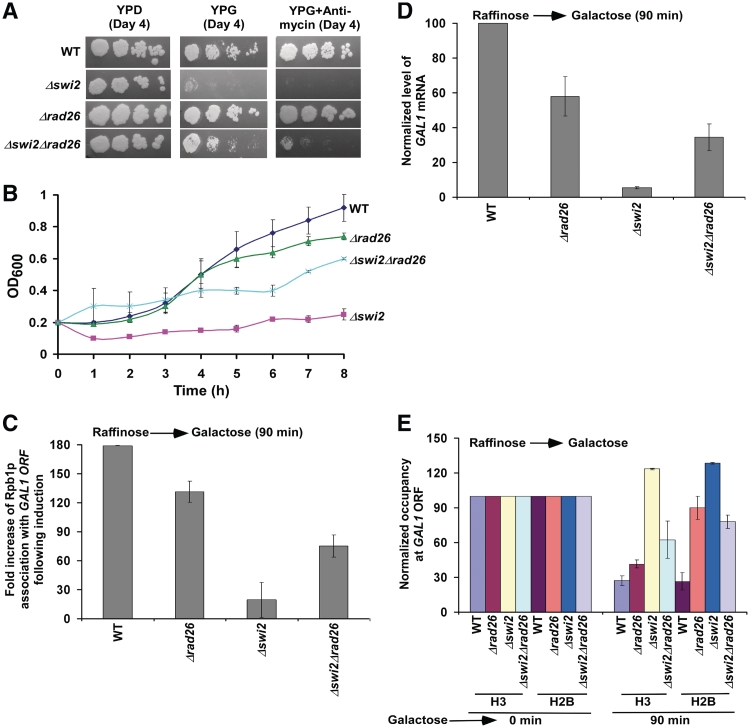

Figure 8.

Growth analysis of the Δswi2, Δrad26, Δswi2Δrad26 and wild-type strains in the solid YPD, YPG, and YPG plus antimycin growth media (A), and liquid YPG medium (B). Fold increase of Rpb1p association with the GAL1 coding sequence following 90 min induction in the Δrad26, Δswi2, Δswi2Δrad26 and wild-type strains (C). Fold increase is the ratio of ChIP signal following 90 min induction to that prior to induction. (D) RT-PCR analysis of GAL1 mRNA following 90 min induction in YPG. (E) Analysis of histone occupancy at the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δrad26, Δswi2, Δswi2Δrad26 and wild-type strains following 90 min transcriptional induction in YPG.

Figure 5.

Eviction of histone H3 from the GAL1 (A), GAL7 (B) and GAL10 (C) coding sequences is impaired immediately following transcriptional induction in the absence of Rad26p. Both the wild-type and Δrad26 strains were grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG for 5 min prior to formaldehyde treatment. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 3.

Figure 6.

Analysis of histone H3 eviction from the GAL1 (A), GAL7 (B) and GAL10 (C) coding sequences following 30 min transcriptional induction in the Δrad26, Δasf1, Δrad26Δasf1 and wild-type strains.

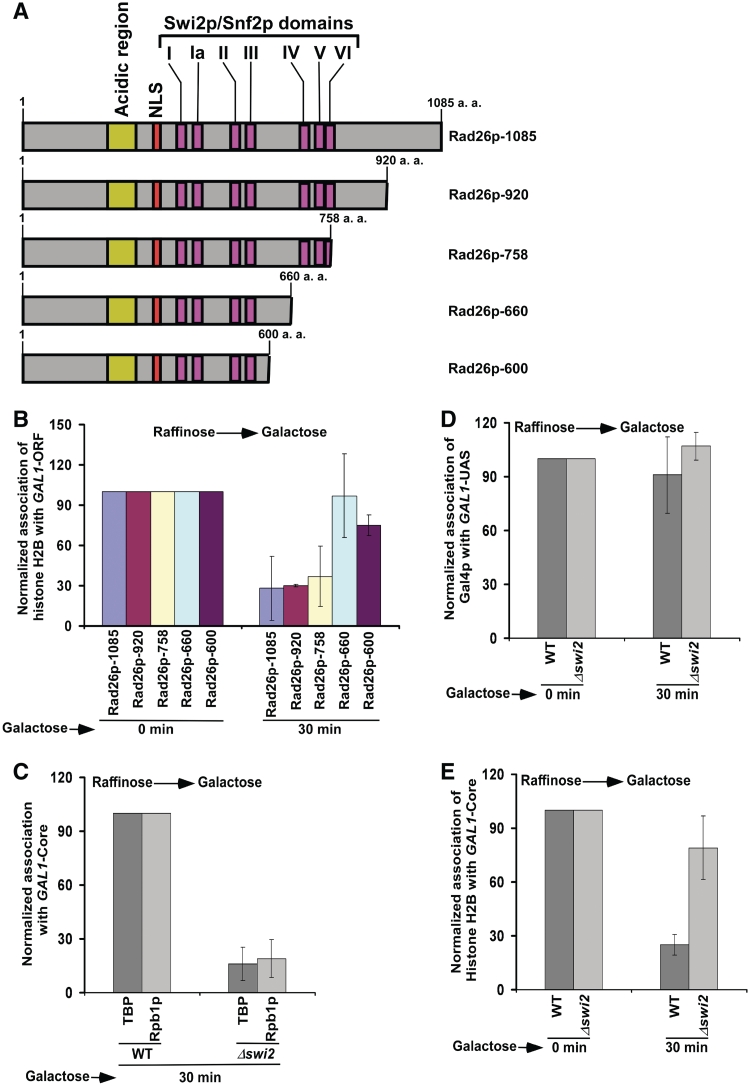

Next, we analyzed the role of Rad26p's ATPase domain in regulation of the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer. Rad26p has seven (I, Ia, II–VI) conserved Swi2p/Snf2p translocase domains essential for ATPase activity (57,58). The domains, IV, V and VI, are present toward the C-terminal of Rad26p, and are essential for its ATPase activity (57). Here, we generated four mutant versions of Rad26p (namely, Rad26p-920, Rad26p-758, Rad26p-660 and Rad26p-600) as schematically shown in Figure 7A. Each mutant version was generated by placing C-terminal HA-epitope tag genomically at the desired positions of Rad26p, and was found to be stable by western blot analysis (data not shown). Using these mutant versions of Rad26p along with the wild-type equivalent (Rad26p-1085), we analyzed the occupancy of histone H2B at the GAL1 coding sequence. We find that the deletion of all amino acids just downstream of the domain VI decreases the occupancy of histone H2B (Figure 7B), and thus histone H2B is evicted normally. But, the deletion of three consecutive domains IV, V and VI does not impair the occupancy of histone H2B (Figure 7B). These three conserved Swi2p/Snf2p domains are essential for ATPase activity (57). Thus, Rad26p regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer via its ATPase activity. However, the effect of the deletion of three consecutive domains (i.e. IV–VI) of Rad26p in regulation of histone H2B occupancy is not dramatic (Figure 7B). Thus, other domain(s) of Rad26p might also be involved in regulating the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer.

Figure 7.

Analysis of the roles of Rad26p's ATPase domain and Swi2p in regulation of the occupancy of histone H2B. (A) Schematic diagram of different mutant versions of Rad26p. (B) The Rad26p mutant without Swi2p/Snf2p domains IV, V and VI is defective in regulating the occupancy of histone H2B. Yeast strains bearing wild-type and mutant versions of Rad26p were grown in YPR up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then switched to YPG for 30 min prior to cross-linking. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 4A. The primer pair targeted to the GAL1 coding sequence was used for PCR analysis of immunoprecipitated DNA samples. (C) Recruitment of TBP and Rpb1p to the GAL1 core promoter is impaired in the Δswi2 strain. Both the wild-type and mutant cells were grown and cross-linked as in panel B. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 1B and G. (D) Analysis of Gal4p recruitment to the GAL1 UAS in the Δswi2 and wild-type strains. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 1G. (E) Analysis of histone H2B occupancy at the GAL1 core promoter in the Δswi2 strain and its isogenic wild-type equivalent.

Like Rad26p, the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex has been implicated in the displacement of histone H2A–H2B dimer but not histone H3–H4 tetramer in the generation of a transiently disrupted chromatin structure (59–61). However, unlike Rad26p, Swi2p component (that possesses DNA-dependent ATPase activity) of the SWI/SNF complex is essential for formation of the PIC at the GAL1 core promoter (Figure 7C). We find that the recruitment of TBP as well as Rpb1p to the GAL1 core promoter is significantly impaired in the Δswi2 strain (Figure 7C). However, the recruitment of Gal4p to the GAL1 UAS is not altered in the Δswi2 strain (Figure 7D). Thus, Swi2p specifically promotes the PIC formation. Furthermore, we observe that the eviction of histone H2A–H2B dimer from the GAL1 core promoter is impaired in the absence of Swi2p (Figure 7E). These results are consistent with previous studies (30,42,62,63) that implicated a correlation between chromatin disassembly and PIC formation. Since transcription is not initiated, histone H2B is not evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence (data not shown). Thus, while Rad26p promotes transcriptional elongation, Swi2p facilitates transcriptional initiation of GAL1. Hence, the yeast strain with null mutations of SWI2 and RAD26 is likely to be inviable in YPG. To test this possibility, we analyzed the growth of the wild-type, Δswi2, Δrad26 and Δswi2Δrad26 strains in solid YPD, YPG and YPG plus antimycin media. We find that the Δswi2 cells do not grow well in solid YPG and YPG plus antimycin media after 4 days (Figure 8A), consistent with previous studies (64). In contrast, the Δrad26 cells grow well in YPG and YPG plus antimycin media (Figure 8A). Interestingly, the Δswi2Δrad26 cells grow better than the Δswi2 cells in solid YPG and YPG plus antimycin media (Figure 8A). Similarly, the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant grows better than the Δswi2 strain in liquid YPG medium (Figure 8B). These results demonstrate that the absence of Rad26p suppresses the Δswi2 growth phenotype, supporting the genetic interaction between RAD26 and SWI2. Since the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant grows better than the Δswi2 strain (Figure 8A and B), it may be likely that the association of RNA polymerase II with GAL1 would be enhanced in the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant as compared with the Δswi2 strain. To test this, we analyzed the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δswi2, Δswi2Δrad26, Δrad26 and wild-type strains following 90 min induction in YPG. We find that the association of RNA polymerase II with the GAL1 coding sequence is significantly increased in the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant as compared with the Δswi2 strain (Figure 8C). Consistently, we find that the GAL1 transcription in the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant is higher than that in the Δswi2 strain (Figure 8D). Since transcription is inversely correlated with the eviction of histones H3–H4 tetramer and H2A–H2B dimer (30,42,62,63), we observed a significant eviction of histones H3 and H2B in the Δswi2Δrad26 double mutant as compared with the Δswi2 strain (Figure 8E). However, both histones H3 and H2B are not evicted from the GAL1 coding sequence in the Δswi2 strain (Figure 8E), consistent with previous studies (30). Thus, RAD26 and SWI2 appear to interact functionally to promote transcription. Based on the fact that Swi2p is required for transcriptional initiation and Rad26p promotes transcriptional elongation, one would expect similar growth phenotypes of the Δswi2Δrad26 and Δswi2 strains. However, our data demonstrate that the deletion of RAD26 suppresses the phenotype of the Δswi2 strain. Thus, both Rad26p and Swi2p are likely to be involved in the same process. Therefore, like Rad26p, Swi2p may also be involved in transcriptional elongation, in addition to its role in transcriptional initiation. Indeed, Schwabish et al. (30) have implicated the role of Swi2p in transcriptional elongation. Taken together, our results support the functional genetic interaction between RAD26 and SWI2. However, the molecular basis of such interaction is yet to be determined.

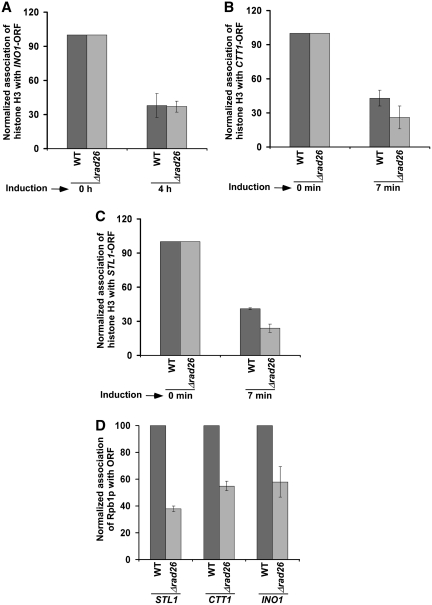

The above results at the GAL genes support that Rad26p regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer during transcriptional elongation. Next, we analyzed whether Rad26p also regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer at the coding sequences of other inducible non-GAL genes such as INO1, CTT1 and STL1. We find that Rad26p predominantly associates with the coding sequences but not promoters of these genes following transcriptional induction (13; Figure 9A and B). Furthermore, we observe that the occupancy of histone H2B at the coding sequences of these genes is not significantly altered in the absence of Rad26p (Figure 9C–E). However, Rad26p does not alter the eviction of histone H3 from the coding sequences of these genes following transcriptional induction (Figure 10A–C). Thus, like the results at the GAL genes, we find that Rad26p predominantly associates with these non-GAL coding sequences, and regulates the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer. Furthermore, we observe that such regulation of the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer by Rad26p is correlated with the association of elongating RNA polymerase II (Figure 10D).

Figure 9.

Rad26p is predominantly associated with the coding sequences of CTT1 (A) and STL1 (B) following transcriptional induction. Yeast cells were grown in synthetic complete medium up to an OD600 of 0.9, and then induced by 0.45 M NaCl for 7 min prior to cross-linking. Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (13). Rad26p facilitates the loss of histone H2B from the INO1 (C), CTT1 (D), and STL1 (E) coding sequences following transcriptional induction. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 4.

Figure 10.

Rad26p does not alter the eviction of histone H3 from the INO1 (A), CTT1 (B) and STL1 (C) coding sequences following transcriptional induction. Both the wild-type and mutant strains were grown and cross-linked as in Figure 9. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 3. (D) Rad26p facilitates the association of RNA polymerase II with the STL1, CTT1 and INO1 coding sequences. Immunoprecipitation was performed as in Figure 1B.

Collectively, our results support an atypical histone H2A–H2B dimer-enriched chromatin in the absence of Rad26p. Notably, the loss of histone H2A–H2B dimer has been shown to impair the formation of higher order chromatin structures that inhibit transcription (49). Furthermore, the loss of histone H2A–H2B dimer has been implicated to facilitate the binding of transcription factors to promote transcription in vitro (47,48). Thus, the enhanced association of RNA polymerase II with the active coding sequences in the presence of Rad26p appears to be mediated through the stimulated eviction of histone H2A–H2B dimer. Furthermore, we have recently demonstrated that the association of Rad26p with the coding sequence is dependent on RNA polymerase II or active transcription (13). Thus, Rad26p is associated with the active coding sequence in an RNA polymerase II-dependent manner, and subsequently, enhances the passage of RNA polymerase II through nucleosomes by promoting the loss of histone H2A–H2B dimer in a feedback fashion in vivo.

Rad26p plays an important role in TCR (65–70). It recognizes DNA lesion in a transcriptional elongation-dependent manner (13), and subsequently, participates in DNA repair. Thus, an enhanced elongation appears to promote TCR by facilitating the recruitment of Rad26p to the lesion. In addition, the decreased occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer in the presence of Rad26p may also be directly enhancing TCR by stimulating the access and recruitment of DNA repair factors to the lesion. Furthermore, Rad26p may be enhancing TCR by directly interacting with and recruiting DNA repair factor(s) to the lesion, since previous studies (71,72) have implicated the interaction of Rad26p with DNA repair factors such as Rad3p and Rad2p. Such possibilities remain to be further elucidated. Nonetheless, this study defines a new physiological role of Rad26p in regulating the occupancy of histone H2A–H2B dimer, and hence chromatin structure. Since Rad26p is highly conserved with human CSB, the chromatin structure in human is likely to be regulated in a similar fashion.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Reference [13].

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health grant (1R15GM088798-01 to Bhaumik laboratory); American Heart Association (National) Scientist Development Grant (0635008N); American Heart Association (Greater Midwest Affiliate) Grant-in-aid award (10GRNT4300059); Mallinckrodt Foundation award. Funding for open access charge: Edward Mallinckrodt Foundation and American Heart Association (Greater Midwest Affiliate).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mary Ann Osley, Kevin Struhl and Ali Shilatifard for yeast strains; Michael R. Green for antibodies; and Sarah Frankland-Searby for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanawalt PC. The bases for Cockayne syndrome. Nature. 2000;405:415–416. doi: 10.1038/35013197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapin I, Weidenheim K, Lindenbaum Y, Rosenbaum P, Merchant SN, Krishna S, Dickson DW. Cockayne syndrome in adults: review with clinical and pathologic study of a new case. J. Child Neurol. 2006;21:991–1006. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleaver JE, Revet I. Clinical implications of the basic defects in Cockayne Syndrome and xeroderma pigmentosum and the DNA lesions responsible for cancer, neurodegeneration and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008;129:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleaver JE, Lam ET, Revet I. Disorders of nucleotide excision repair: the genetic and molecular basis of heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:756–768. doi: 10.1038/nrg2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weidenheim KM, Dickson DW, Rapin I. Neuropathology of Cockayne syndrome: evidence for impaired development, premature aging, and neurodegeneration. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009;130:619–636. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nance MA, Berry SA. Cockayne syndrome: review of 140 cases. Am. J. Med. Gen. 1992;42:68–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hoffen A, Natarajan AT, Mayne LV, van Zeeland AA, Mullenders LHF, Venema J. Deficient repair of the transcribed strand of active genes in Cockayne's syndrome cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5890–5895. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellon I, Spivak G, Hanawalt PC. Selective removal of transcription-blocking DNA damage from the transcribed strand of the mammalian DHFR gene. Cell. 1987;51:241–249. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selby CP, Sancar A. Cockayne syndrome group B protein enhances elongation by RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:11205–11209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Gool AJ, Verhage R, Swagemakers SMA, van de Putte P, Brouwer J, Troelstra C, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JHJ. RAD26, the functional S. cerevisiae homolog of the Cockayne syndrome B gene ERCC6. EMBO J. 1994;13:5361–5369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SK, Yu SL, Prakash L, Prakash S. Requirement for yeast RAD26, a homologue of the human CSB gene, in elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:8651–8656. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8651-8656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SK, Yu SL, Prakash L, Prakash S. Yeast RAD26, a homolog of the human CSB gene, functions independently of nucleotide excision repair and base excision repair in promoting transcription through damaged bases. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:4383–4389. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4383-4389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malik S, Chaurasia P, Lahudkar S, Durairaj G, Shukla A, Bhaumik SR. Rad26p, a transcription-coupled repair factor, is recruited to the site of DNA lesion in an elongating RNA polymerase II-dependent manner in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1461–1477. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzder SN, Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. RAD26, the yeast homolog of human Cockayne's syndrome group B gene, encodes a DNA dependent ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18314–18317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selby CP, Sancar A. Human transcription-repair coupling factor CSB/ERCC6 is a DNA-stimulated ATPase but is not a helicase and does not disrupt the ternary transcription complex of stalled RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:1885–1890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.3.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson RE, Henderson ST, Petes TD, Prakash S, Bankmann M, Prakash L. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD5-encoded DNA repair protein contains DNA helicase and zinc-binding sequence motifs and affects the stability of simple repetitive sequences in the genome. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992;12:3807–3818. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eisen JA, Sweder KS, Hanawalt PC. Evolution of the SNF2 family of proteins: subfamilies with distinct sequences and functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2715–2723. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Citterio E, van den Boom V, Schnitzler G, Kanaar R, Bonte E, Kingston RE, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling by the Cockayne syndrome B DNA repair-transcription-coupling factor. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:7643–7653. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7643-7653.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregory SM, Sweder KS. Deletion of the CSBhomolog, RAD26, yields Spt(-) strains with proficient transcription-coupled repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3080–3086. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Côté J, Quinn J, Workman JL, Peterson CL. Stimulation of GAL4 derivative binding to nucleosomal DNA by the yeast SWI/SNF complex. Science. 1994;265:53–60. doi: 10.1126/science.8016655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imbalzano AN, Kwon H, Green MR, Kingston RE. Facilitated binding of TATA-binding protein to nucleosomal DNA. Nature. 1994;370:481–485. doi: 10.1038/370481a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornberg RD, Lorch Y. Chromatin-modifying and -remodeling complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999;9:148–151. doi: 10.1016/S0959-437X(99)80022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon H, Imbalzano AN, Khavari PA, Kingston RE, Green MR. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SW1/SNF complex. Nature. 1994;370:477–481. doi: 10.1038/370477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imbalzano AN, Schnitzler GR, Kingston RE. Nucleosome disruption by human SWI/SNF is maintained in the absence of continued ATP hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:20726–20733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longtine MS, McKenzie A, III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pingle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukuda T, Fleming AB, Nickoloff JA, Osley MA. Chromatin remodelling at a DNA double-strand break site in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2005;438:379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature04148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SE, Moore JK, Holmes A, Umezu K, Kolodner RD, Haber JE. Saccharomyces Ku70, mre11/rad50 and RPA proteins regulate adaptation to G2/M arrest after DNA damage. Cell. 1998;94:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. Asf1 mediates histone eviction and deposition during elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. The Swi/Snf complex is important for histone eviction during transcriptional activation and RNA polymerase II elongation in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:6987–6995. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00717-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirschhorn JN, Brown SA, Clark CD, Winston F. Evidence that SNF2/SWI2 and SNF5 activate transcription in yeast by altering chromatin structure. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2288–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12a.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhaumik SR, Green MR. Differential requirement of SAGA components for recruitment of TATA-box-binding protein to promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:7365–7371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7365-7371.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhaumik SR, Green MR. Interaction of Gal4p with components of transcription machinery in vivo. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:445–454. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70038-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shukla A, Stanojevic N, Duan Z, Sen P, Bhaumik SR. Ubp8p, a histone deubiquitinase whose association with SAGA is mediated by Sgf11p, differentially regulates lysine 4 methylation of histone H3 in vivo. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:3339–3352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3339-3352.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhaumik SR, Raha T, Aiello DP, Green MR. In vivo target of a transcriptional activator revealed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Genes Dev. 2004;18:333–343. doi: 10.1101/gad.1148404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malik S, Shukla A, Sen P, Bhaumik SR. The 19s proteasome subcomplex establishes a specific protein interaction network at the promoter for stimulated transcriptional initiation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:35714–35724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durairaj G, Chaurasia P, Lahudkar S, Malik S, Shukla A, Bhaumik SR. Regulation of chromatin assembly/disassembly by Rtt109p, a histone H3 Lys56-specific acetyltransferase, in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:30472–30479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peterson CL, Kruger W, Herskowitz I. A functional interaction between the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II and the negative regulator SIN1. Cell. 1991;64:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nag R, Gong F, Fahy D, Smerdon MJ. A single amino acid change in histone H4 enhances UV survival and DNA repair in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3857–3866. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woudstra EC, Gilbert C, Fellows J, Jansen L, Brouwer J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Svejstrup JQ. A Rad26-Def1 complex coordinates repair and RNA pol II proteolysis in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2002;415:929–933. doi: 10.1038/415929a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwabish MA, Struhl K. Evidence for eviction and rapid deposition of histones upon transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:10111–10117. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10111-10117.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korber P, Luckenbach T, Blaschke D, Hörz W. Evidence for histone eviction in trans upon induction of the yeast PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:10965–10974. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10965-10974.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorch Y, Maier-Davis B, Kornberg RD. Chromatin remodeling by nucleosome disassembly in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:3090–3093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Removal of promoter nucleosomes by disassembly rather than sliding in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams SK, Tyler JK. Transcriptional regulation by chromatin disassembly and reassembly. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007;17:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kireeva ML, Walter W, Tchernajenko V, Bondarenko V, Kashlev M, Studitsky VM. Nucleosome remodeling induced by RNA polymerase II: loss of the H2A/H2B dimer during transcription. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hayes JJ, Wolffe AP. Histones H2A/H2B inhibit the interaction of transcription factor IIIA with the Xenopus borealis somatic 5S RNA gene in a nucleosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:1229–1233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hansen JC, Wolffe AP. A role for histones H2A/H2B in chromatin folding and transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:2339–2343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boeger H, Griesenbeck J, Strattan JS, Kornberg RD. Nucleosomes unfold completely at a transcriptionally active promoter. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1587–1598. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reinke H, Horz W. Histones are first hyperacetylated and then lose contact with the activated PHO5 promoter. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1599–1607. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tyler JK. Chromatin assembly. Cooperation between histone chaperones and ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling machines. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:2268–2274. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haushalter KA, Kadonaga JT. Chromatin assembly by DNA-translocating motors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:613–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polo SE, Almouzni G. Chromatin assembly: a basic recipe with various flavours. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006;16:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park YJ, Luger K. Histone chaperones in nucleosome eviction and histone exchange. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andrews AJ, Chen X, Zevin A, Stargell LA, Luger K. The histone chaperone Nap1 promotes nucleosome assembly by eliminating non-nucleosomal histone DNA interactions. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Licht CL, Stevnsner T, Bohr VA. Cockayne syndrome group B cellular and biochemical functions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:1217–1239. doi: 10.1086/380399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taschner M, Harreman M, Teng Y, Gill H, Anindya R, Maslen SL, Skehel JM, Waters R, Svejstrup JQ. A role for checkpoint kinase-dependent Rad26 phosphorylation in transcription-coupled DNA repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;30:436–446. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00822-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruno M, Flaus A, Stockdale C, Rencurel C, Ferreira H, Owen-Hughes T. Histone H2A/H2B dimer exchange by ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling activities. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1599–1606. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00499-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vicent GP, Nacht AS, Smith CL, Peterson CL, Dimitrov S, Beato M. DNA instructed displacement of histones H2A and H2B at an inducible promoter. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:439–452. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang X, Zaurin R, Beato M, Peterson CL. Swi3p controls SWI/SNF assembly and ATP-dependent H2A-H2B displacement. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:540–547. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adkins MW, Williams SK, Linger J, Tyler JK. Chromatin disassembly from the PHO5 promoter is essential for the recruitment of the general transcription machinery and coactivators. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;27:6372–6382. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00981-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shukla A, Bajwa P, Bhaumik SR. SAGA-associated Sgf73p facilitates formation of the preinitiation complex assembly at the promoters either in a HAT-dependent or independent manner in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6225–6232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Larschan E, Winston F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Srb8-Srb11 complex functions with the SAGA complex during Gal4-activated transcription. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;25:114–123. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.114-123.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu SL, Lee SK, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. The stalling of transcription at abasic sites is highly mutagenic. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:382–388. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.382-388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhatia PK, Verhage RA, Brouwer J, Friedberg EC. Molecular cloning and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD28, the yeast homolog of the human Cockayne syndrome A (CSA) gene. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5977–5988. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.5977-5988.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jansen LE, den Dulk H, Brouns RM, de Ruijter M, Brandsma JA, Brouwer J. Spt4 modulates Rad26 requirement in transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 2000;19:6498–6507. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teng Y, Waters R. Excision repair at the level of the nucleotide in the upstream control region, the coding sequence and in the region where transcription terminates of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MFA2 gene and the role of RAD26. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1114–1119. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.5.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Gool AJ, Verhage R, Swagemakers SM, van de Putte P, Brouwer J, Troelstra C, Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers JH. RAD26, the functional S. cerevisiae homolog of the Cockayne syndrome B gene ERCC6. EMBO J. 1994;13:5361–5369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verhage RA, van Gool AJ, de Groot N, Hoeijmakers JH, van de Putte P, Brouwer J. Double mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with alterations in global genome and transcription-coupled repair. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996;16:496–502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.2.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ho Y, et al. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature. 2002;415:180–183. doi: 10.1038/415180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee SK, Yu SL, Prakash L, Prakash S. Requirement of yeast RAD2, a homolog of human XPG gene, for efficient RNA polymerase II transcription. Implications for Cockayne syndrome. Cell. 2002;109:823–834. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.