Abstract

The Golgi apparatus of eukaryotic cells is known for its central role in the processing, sorting, and transport of proteins to intra- and extra-cellular compartments. In plants, it has the additional task of assembling and exporting the non-cellulosic polysaccharides of the cell wall matrix including pectin and hemicelluloses, which are important for plant development and protection. In this review, we focus on the biosynthesis of complex polysaccharides of the primary cell wall of eudicotyledonous plants. We present and discuss the compartmental organization of the Golgi stacks with regards to complex polysaccharide assembly and secretion using immuno-electron microscopy and specific antibodies recognizing various sugar epitopes. We also discuss the significance of the recently identified Golgi-localized glycosyltransferases responsible for the biosynthesis of xyloglucan (XyG) and pectin.

Keywords: cell wall, immunocytochemistry, glycosyltransferases, Golgi, polysaccharides, plants

Introduction

One of the most important functional properties of the plant Golgi apparatus is its ability to synthesize complex matrix polysaccharides of the cell wall. Unlike cellulose which is synthesized at the plasma membrane and glycoproteins whose protein backbones are generated in the endoplasmic reticulum, the cell wall matrix polysaccharides (pectin and hemicelluloses) are assembled exclusively in the Golgi cisternae and transported to the cell surface within Golgi-derived vesicles (Driouich et al., 1993; Lerouxel et al., 2006).

The synthesis of cell wall matrix polysaccharides occurs through the concerted action of hundreds of glycosyltransferases. These enzymes catalyze the transfer of a sugar residue from an activated nucleotide–sugar onto a specific acceptor. The activity of these enzymes depends, in turn upon nucleotide–sugar synthesizing/interconverting enzymes in the cytosol, and also on the nucleotide–sugar transporters necessary for sugar transport into the lumen of Golgi stacks and subsequent polymerization.

Because cell wall matrix polysaccharides exhibit a high structural complexity, their biosynthesis must be adequately organized and a certain degree of spatial organization/coordination must prevail within Golgi compartments, not only between glycosyltransferases themselves, but also between glycosyltransferases nucleotide–sugar transporters and nucleotide–sugar interconverting enzymes (Seifert, 2004; Reiter, 2008).

Cell wall matrix polysaccharides are known to confer important functions to the cell wall in relation with many aspects of plant life including cell growth, morphogenesis and responses to abiotic, and biotic stresses. Plant cell walls are also an important source of raw materials for textiles, pulping and, potentially, for renewable biofuels or food production for humans and animals (Cosgrove, 2005; Pauly and Keegstra, 2010).

The Primary Cell Wall is Composed of Diverse Complex Carbohydrates

Plants invest a large proportion of their genes (∼10%) in the biosynthesis and remodeling of the cell wall (Arabidopsis Genome Initiative, 2000; International Rice Genome Sequencing Project, 2005; Tuskan et al., 2006).

Cell walls of flowering plants are highly diverse and heterogeneous (Popper et al., 2011). They are composed of a variety of complex carbohydrates whose compositional and structural properties are controlled spatially and temporally as well as at the tissue and cell levels (Roberts, 1990; see also Burton et al., 2010).

The primary wall of eudicotyledonous plants comprises cellulose microfibrils and a xyloglucan network embedded within a matrix of non-cellulosic polysaccharides and proteins (i.e., glycoproteins and proteoglycans). Four major types of non-cellulosic polysaccharides are found in the primary walls of plant cells (in taxa outside the gramineae), namely the neutral hemicellulosic polysaccharide xyloglucan (XyG) and three main pectic polysaccharides, homogalacturonan (HG), rhamnogalacturonan I and rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-I and RG-II; Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993; Mohnen, 2008; Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010).

XyG consists of a β-d-(1-4)-glucan backbone to which are attached side chains containing xylosyl, galactosyl–xylosyl, or fucosyl–galactosyl–xylosyl residues. In eudicotyledonous plants, XyG is the principal polysaccharide that cross-links the cellulose microfibrils. It is able to bind cellulose tightly because its β-d-(1-4)-glucan cellulose-like backbone can form numerous hydrogen bonds with the microfibrils. A single XyG molecule can therefore interconnect separate cellulose microfibrils. This XyG-cellulose network forms a major load-bearing structure that contributes to the structural integrity of the wall and the control of cell expansion (Cosgrove, 1999, 2005; Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010).

The pectic matrix is structurally complex and heterogeneous. HG domains consist of α-d-(1-4)-galacturonic acid (GalA) residues, which can be methyl-esterified, acetylated, and/or substituted with xylose to form xylogalacturonan (Willats et al., 2001; Vincken et al., 2003). De-esterified blocks of HG can be cross-linked by calcium producing a gel matrix which is believed to be essential for cell adhesion (Jarvis, 1984). RG-I domains contain repeats of the disaccharide [-4-α-d-GalA-(1-2)-α-l-Rha-(1-)] and the rhamnosyl residues can possess oligosaccharide side chains consisting predominantly of β-d-(1−4)-galactosyl- and/or α-l-(1-5)-arabinosyl-linked residues (McNeil et al., 1982). Side chains of RG-I can also contain α-l-fucosyl, β-d-glucuronosyl, and 4-O-methyl β-d-glucuronosyl residues and vary in length depending on the plant source (O’Neill et al., 1990). These chains are believed to decrease the ability of pectic molecules to cross-link and form a stable gel network, and are thereby able to influence the mechanical properties of the cell wall (Hwang and Kokini, 1991). In addition, the structure and tissue distribution of arabinan- or galactan-rich side chains of RG-I have been shown to be regulated during cell growth and development of many species (for review see Willats et al., 2001; Scheller et al., 2007; Harholt et al., 2010).

RG-II is the most structurally complex pectic polysaccharide discovered so far in plants and is of a relatively low molecular mass (5–10 Kda; Ridley et al., 2001). It occurs in the cell walls of all higher plants as a dimer (dRG-II-B) that is cross-linked by borate di-esters (Matoh et al., 1993; Ishii and Matsunaga, 1996; Kobayashi et al., 1996; O’Neill et al., 1996). The backbone of RG-II is composed of a HG-like structure containing at least eight α-d-(1-4)-GalA-linked residues to which four structurally different oligosaccharide chains, denoted A, B, C, and D, are attached. The C and D side chains are attached to C-3 of the GalA residues of the backbone whereas A and B are attached to C-2 of GalA residues (O’Neill et al., 2004). The C chain corresponds to a disaccharide that contains rhamnose and 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo), whereas the D chain is a disaccharide of 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-lyxo-heptulosaric acid (Dha) and arabinose (O’Neill et al., 2004). The A and B oligosaccharide chains are both composed of eight to ten monosaccharides and are attached by a β-d-apiose residue to O-2 of the backbone. A D-galactosyl residue (D-Gal) occurs on the B chain. RG-II plays an important role in the regulation of porosity and mechanical properties of primary cell walls (Ishii et al., 2001). This in turn has an important impact on growth and development as has been shown from studies using various Arabidopsis mutants (O’Neill et al., 2001; Reuhs et al., 2004; Voxeur et al., 2011).

As for hemicellulosic polysaccharides, it is worth to note that glucurono(arabino)xylan (GAX) does exist in the primary cell walls of eudicotyledonous although at very limited amounts. It is however mostly present in the secondary walls of eudicotyledonous as well as in both the primary and secondary walls of grasses (see also Vogel, 2008 for a difference in polysaccharide composition of the cell walls between grasses and eudicots). GAX of eudicotyledonous primary cell wall is composed of a linear β-d-(1 −4)-xylose backbone substituted with both neutral and acidic side chains. The acidic side chains are terminated with glucuronosyl or 4-O-methyl glucuronosyl residues, whereas the neutral side chains are composed of arabinosyl and/or xylosyl residues (Darvill et al., 1980; Zablackis et al., 1995; Vogel, 2008). GAX is also known to be synthesized within Golgi stacks and significant advances have recently been made in understanding its biosynthesis (Faik, 2010). However, this is beyond the focus of this review and only major polysaccharides of the primary cell walls of eudicotyledonous are considered here below.

The Role of the Golgi Apparatus in Complex Polysaccharide Biosynthesis

The Golgi implication in the construction of the cell wall

In higher plants, the Golgi apparatus plays a fundamental role in “the birth” of the cell wall. During cytokinesis, a new cell wall is formed and starts to assemble with the transport of Golgi-derived secretory vesicles to the center of a dividing cell. Fusion of these vesicles gives rise to a thin membrane-bound structure, the cell plate, which undergoes an elaborate process of maturation leading to a fully functional cell wall (Staehelin and Hepler, 1996; Cutler and Ehrhardt, 2002; Segui-Simarro et al., 2004). Also to perform the plant cell growth, new polysaccharides are delivered to growing cell wall by fusion of Golgi vesicles with the plasma membrane (Cosgrove, 2005).

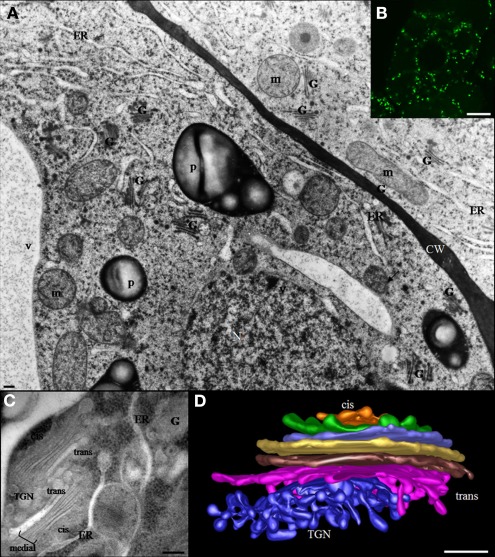

The Golgi apparatus of plant cells is a dynamic and organized organelle consisting of a large number of small independent Golgi stacks that are randomly dispersed throughout the cytoplasm. At the confocal microscopy level, individual green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Golgi stacks (around 1 μm in diameter) appear as round disks, small rings, or short lines depending on their orientation (Nebenführ et al., 1999; Ritzenthaler et al., 2002). At the level of transmission electron microscopy in high pressure frozen/freeze substituted cells, each stack appears to consist of three types of cisternae, designated cis, medial, and trans that are defined based on their position within a stack and their unique morphological features (Staehelin et al., 1990; Staehelin and Kang, 2008). This morphological polarity reflects different functional properties of Golgi compartments (Figure 1; Staehelin et al., 1990; Driouich and Staehelin, 1997). The number of stacks per cell, as well as the number of cisternae within an individual stack, varies with the cell type, the developmental stage of the cell and the plant species (Staehelin et al., 1990; Zhang and Staehelin, 1992).

Figure 1.

(A) Electron micrograph of suspension-cultured tobacco cells preserved by high pressure freezing showing the random distribution of Golgi stacks throughout the cytoplasm. The bar represents 0.5 μm. (B) Confocal microscopy image showing distribution of Golgi stacks in suspension-cultured tobacco (BY-2) cells. Golgi stacks-expressing the Golgi XyG-synthesizing enzyme (XyG –GalT/MUR3) fused to GFP are visible as bright green spots. The bar represents 8 μm. (C) Two Golgi stacks and associated trans Golgi network (TGN) in a tobacco BY-2 suspension-cultured cell. Cis-, medial, and trans type of cisternae as well as the TGN are indicated. The bar represents 0.1 μm. (D) Electron tomographic model of a Golgi stack in a columella root cell of Arabidopsis. CW, cell wall; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; G, Golgi stack; m, mitochondria; N, nucleus; P, plastid; TGN, trans Golgi network; V, vacuole.

The trans Golgi network (TGN) is a branched tubulo-vesicular structure that is frequently located close to trans cisternae. However, the TGN can be found remote from the Golgi stack located throughout the cytosol as an independent compartment. Two types of TGN compartments have been described and referred to as an early and a late TGN (see Staehelin and Kang, 2008). The plant TGN plays a major role in sorting of proteins and it represents a meeting point of secretory, endocytosis, and membrane recycling pathways. Recent studies have shown that certain TGN types, can serve also as early endosomes and thus have been termed TGN-Early endosomes (Dettmer et al., 2006; Richter et al., 2009; Viotti et al., 2010).

In contrast to the Golgi complex in mammalian cells that has a fixed location near the centrosomes, Golgi units in plants appear to move actively throughout the cytoplasm (Boevink et al., 1998; Nebenführ et al., 1999). GFP-fusions have allowed the study of Golgi dynamics in vivo and have shown that each Golgi unit can move at a slow or high speed (up to 5 μm/s) without loosing structural integrity (Boevink et al., 1998; Nebenführ et al., 1999; Brandizzi et al., 2002). In addition, cytoskeletal depolymerization studies have indicated that the movement of Golgi stacks depends on actin filaments rather than on microtubules (Nebenführ et al., 1999). Indeed, it is now established that the movement of Golgi stacks in plant cells occurs along actin filaments driven by myosin motors (Staehelin and Kang, 2008). In the context of this review, it is worth noting that actin filaments interact with Golgi stacks via an actin-binding protein, KATAMARI 1/MURUS3 – that is also known as a glycosyltransferase required for cell wall biosynthesis (see below; Tamura et al., 2005). KATAMARI 1 has been shown to be involved in maintaining the organization and dynamics of Golgi membranes.

As in animal cells (Rabouille et al., 1995), the plant Golgi apparatus functions in the processing and modification of N-linked glycoproteins (Pagny et al., 2003; Saint Jore Dupas et al., 2006; Schoberer and Strasser, 2011); but the bulk of the biosynthetic activity of this organelle is devoted to the assembly of different subtypes of complex, non-cellulosic polysaccharides of the cell wall such as pectin and hemicelluloses.

The first studies implicating plant Golgi stacks in cell wall biogenesis date back to the 60 and 70 and involved cytochemical staining as well as autoradiographic experiments with radiolabeled sugars (Pickett-Heaps, 1966, 1968; Harris and Northcote, 1971; Dauwalder and Whaley, 1974). These investigations have shown that Golgi cisternae and Golgi-derived vesicles are rich in carbohydrates and that a similar carbohydrate content is found in the cell plate, the cell wall and in Golgi-enriched fractions. Additionally, biochemical evidence for the role of the Golgi apparatus in the assembly of cell wall polysaccharides was obtained from fractionation experiments in which several glycosyltransferase activities (e.g., xylosyltransferase, arabinosyltransferase, fucosyltransferase) were detected in Golgi membranes (Gardiner and Chrispeels, 1975; Green and Northcote, 1978; Ray, 1980). Further biochemical investigations, reported in the eighties and nineties, allowed the identification and partial characterization of Golgi-associated enzymes specifically involved in the synthesis of XyG and pectic polysaccharides (Camirand et al., 1987; Brummell et al., 1990; Gibeaut and Carpita, 1994).

More recently, a proteomic method called LOPIT, for Localization of Organelle Proteins by Isotope Tagging, has been developed in order to determine the subcellular localization of membrane proteins in organelles of the secretory pathway such as Golgi stacks (Dunkley et al., 2004, 2006). This approach has allowed the identification of the α1,6-xylosyltransferase (AtXT1) involved in XyG biosynthesis, in the Golgi apparatus (Dunkley et al., 2004).

In connection with XyG biosynthesis, it is remarkable to note that the structure of XyG present in isolated Golgi membranes has been investigated using oligosaccharide mass profiling (OLIMP) method (Obel et al., 2009). This study has revealed subtle differences in the structure of the polymer with XXG and GXXG fragments being more abundant in Golgi-enriched fraction as compared to the cell wall. However, due to the inability of subfractionating plant Golgi stacks into cis, medial, and trans cisternae, it is not possible to associate a XyG oligosaccharide to a specific sub-compartment of the Golgi apparatus. For similar reasons, it is still not possible neither to determine how the enzymes are spatially organized and how complex polysaccharides are assembled within Golgi sub-compartments using biochemical methods.

Spatial organization of the complex polysaccharide assembly pathway in Golgi stacks: Insights from immuno-electron microscopy

Progress toward understanding the compartmentalization of matrix cell wall polysaccharide biosynthesis has come from immuno-electron microscopical analyses with antibodies directed against specific sugar epitopes. In most cases, these immunolabeling studies have been performed on a variety of cells prepared by high pressure freezing, a cryofixation technique that is recognized as providing excellent preservation of Golgi stacks thereby allowing different cisternal subtypes to be easily distinguished (Staehelin et al., 1990; Zhang and Staehelin, 1992; Driouich et al., 1993; Follet-Gueye et al., 2012). More recently, a combination of cryofixation/freeze substitution with Tokuyasu cryosectioning have been used to immunolocalize polysaccharide epitopes in Golgi stacks of Arabidopsis (Stierhof and El Kasmi, 2010). This technology is quite promising and should be able to provide interesting information on the localization of epitopes within plant Golgi cisternae.

Quantitative immunolabeling experiments using antibodies recognizing either the XyG backbone (anti-XG antibodies: Moore et al., 1986; Lynch and Staehelin, 1992) or an α-l-Fucp-(1-2)-β-d-Galp epitope of XyG side chains in sycamore cultured cells have shown that the epitopes localize to trans cisternae and the TGN (Zhang and Staehelin, 1992). These data suggested that the synthesis of XyG occurs exclusively in late compartments of the Golgi and that no precursor forms of XyG are made in cis and medial cisternae. The use of these antibodies on clover and Arabidopsis root tip cells have also suggested that the synthesis of XyG takes place in trans Golgi cisternae and the TGN (Moore et al., 1991; Driouich et al., 1994). Nevertheless, it could be argued that the sugar epitopes recognized by both antibodies are not accessible until they reach the trans and TGN compartments, or that the antibodies do not bind XyG precursor forms in cis and medial cisternae. More recently, Viotti et al. (2010) have also shown that fucosylated epitopes of XyG occur preferentially in trans cisternae and the TGN using thawed ultrathin cryosections of high pressure frozen/freeze substituted and rehydrated Arabidopsis root tip cells. Therefore, it is necessary to localize XyG-synthesizing enzymes within Golgi cisternae to determine whether XyG synthesis is exclusively limited to trans and TGN cisternae. Although no antibody against any XyG-synthesizing enzyme is currently available, one possible approach of addressing this issue is to produce transgenic plants expressing GFP-tagged glycosyltransferases, followed by localization with anti-GFP antibodies. Such a strategy has been successfully used to study the compartmentation of enzymes involved in the processing of N-linked glycoproteins, including a β-1,2-xylosyltransferase responsible for the addition of β-1,2 xylose residues and an α-1,2-mannosidase responsible for the removal of α-1,2 mannose residues in tobacco suspension-cultured cells (Follet-Gueye et al., 2003; Pagny et al., 2003; Saint Jore Dupas et al., 2006). The same strategy has been recently applied to enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of XyG side chains including α-1,6-xylosyltransferase (AtXT1), β-1,2-galactosyltransferase (AtMUR3), and α-1,2-fucosyltransferase (AtFUT1; Chevalier et al., 2010). Immunogold localization of these GFP-tagged glycosyltransferases has demonstrated that AtXT1–GFP is mainly located in the cis and medial cisternae, AtMUR3–GFP is predominantly associated with medial cisternae and AtFUT1–GFP mostly detected over trans cisternae suggesting that initiation of XyG side chains occurs in early Golgi compartments in tobacco suspension-cultured (BY-2) cells.

Another interesting approach to study sub-Golgi localization of glycosyltransferases is through development of in silico predictors based on the transmembrane domain of these enzymes. Such an approach employing a support vector machine (SVM) algorithm has been recently used to predict the localization of several human and mouse glycosyltransferases and glycohydrolases within Golgi sub-compartments (van Dijk et al., 2008). This is an interesting methodology to apply for the prediction of sub-Golgi localization of the known plant glycosyltransferases involved in cell wall biosynthesis. Using this approach AtRGXT1 and AtRGXT2 -two α-1,3-xylosyltransferases involved in the synthesis of the pectic polysaccharide RG-II- have been predicted to be confined to the TGN (P. Ulskov, personal communication).

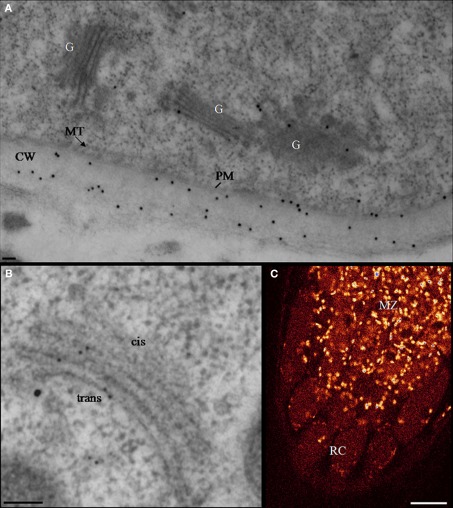

As for XyG synthesis, similar immunocytochemical studies using antibodies raised against pectin epitopes (including JIM7, anti-PGA/RG-I, and CCRCM2) has allowed a partial characterization of the assembly pathway of homogalacturonan (HG) and RG-I within Golgi cisternae (Zhang and Staehelin, 1992). The polyclonal anti-PGA/RG-I antibodies (recognizing un-esterified HG) were shown to label mostly cis and medial cisternae in suspension-cultured sycamore cells as well as in clover root cortical cells (Moore et al., 1991; Zhang and Staehelin, 1992). In contrast, JIM7 (specific for methyl-esterified HG) labeling was mostly confined to medial and trans cisternae (Figure 2). Consistent with this data is the localization of the putative pectin methyltransferase, QUASIMODO2 (Mouille et al., 2007) fused to GFP which was found mainly in medial and trans cisternae of Golgi stacks in Arabidopsis root tip cells (Chevalier et al., unpublished; Figure 2). In addition, the mAb CCRCM-2 which is believed, but not proven, to bind RG-I side chains was found to label trans cisternae in sycamore cultured cells (Zhang and Staehelin, 1992). These data suggest that HG is synthesized in its un-esterified form in cis and medial Golgi cisternae and, that (i) the methylesterification occurs in both medial and trans compartments, and (ii) that side chains of RG-I are added in trans cisternae. However, as discussed above for XyG labeling, the absence of labeling in trans cisternae and the TGN by anti-PGA/RG-I antibodies, might be due to the inaccessibility of the recognized epitopes in these compartments (because of the methylesterification for instance). This idea is supported by the fact that the same epitopes are localized predominantly in trans Golgi cisternae and the TGN in the epidermal cells of clover. Thus, it is not surprising that the compartmentation of cell wall matrix polysaccharides within Golgi cisternae varies in a cell type specific manner. The distribution of XyG and HG in Golgi membranes has also been investigated immunocytochemically in root hair cells of Vicia villosa preserved by high pressure freezing (Sherrier and VandenBosch, 1994). Although no quantitative analyses were performed, methyl-esterified HG epitopes recognized by JIM7 were detected within medial and trans cisternae, whereas the fucose-containing epitope of XyG (recognized by CCRCM1) was found over trans Golgi cisternae. These observations are consistent with those made in sycamore suspension-cultured cells and clover root cortical cells using the same antibodies (Moore et al., 1991; Zhang and Staehelin, 1992). However, the V. villosa study did not address the issue of RG-I side chain distribution within Golgi stacks using the mAb CCRCM2. Therefore, the use of the more recently produced monoclonal antibodies LM5 and LM6, recognizing β-1,4-d-galactan and α-1,5-d-arabinan epitopes, respectively (Jones et al., 1997; Willats et al., 1998) should prove very useful for extending the “current map” of the pectin assembly pathway within the Golgi cisternae of sycamore cultured cells and V. villosa root hairs. Both antibodies have been widely used to study the distribution of galactan and arabinan epitopes within the cell walls, but relatively very little is known concerning their localization within the endomembrane system. In flax root cells, LM5-containing epitopes have been shown to be present mostly in trans cisternae and the TGN (Vicré et al., 1998). Similarly, epitopes recognized by LM5 and LM6 have been quantitatively localized to TGN in tobacco (BY-2) cultures (Bernard et al., unpublished). Therefore, it appears that galactan- and arabinan-containing side chains of RG-I are assembled in the TGN. Whether the enzymes responsible for the addition of these residues are confined to the same Golgi sub-compartments remains to be determined by future studies. One of the genes involved in the synthesis of RG-I side chains, namely ARAD1 (encoding a putative α-1,5-d-arabinosyltransferase) has been recently identified and cloned (see below). The generation of specific antibodies against this glycosyltransferase, or the generation of a GFP-tagged protein should help us to understand more about its specific localization within Golgi compartments. To extend our understanding of RG-I synthesis within Golgi stacks, the use of the new monoclonal antibodies specifically raised against the RG-I backbone (Ralet et al., 2010) or the LM13 recognizing longer oligoarabinosides than LM6, should be very helpful. In contrast to RG-I, information on the localization and assembly of RG-II within the endomembrane system is missing. RG-II has a complex structure consisting of a HG-like backbone and four side chains that contain specific and unusual sugars including Kdo and apiose (see above). It would certainly be interesting to find out whether the backbone is assembled in the same compartments as the side chains and whether different side chains are assembled in the same or distinct compartments. The elucidation of RG-II assembly within sub-compartments of Golgi stacks requires the generation of antibodies specific for the sugar epitopes of the backbone and for the epitopes associated with different side chains, as well as the associated immuno-electron microscopy studies.

Figure 2.

Homogalacturonan localization in transgenic Arabidopsis root tips expressing the QUA2–GFP fusion protein. (A,B) Electron micrographs illustrating typical double-immunogold labeling of Golgi stacks (G) in Arabidopsis root cells with the mAbs JIM7 (20 nm gold particles) or with anti-GFP (10 nm gold particles). HG epitopes and the QUA2–GFP are predominantly associated with the trans cisternae and the TGN. The cell wall (CW) is labeled with JIM 7. Bar represents 100 nm. (C) A confocal laser fluorescence image of Arabidopsis root tip expressing the fusion protein QUA2–GFP. Bright spots represent GFP-stained Golgi units. Scale Bar: 16 μm (Chevalier et al., unpublished). CW, cell wall; G, Golgi stack; MT, microtubule; PM, plasma membrane; MZ, meristematic zone; RC, root cap.

It is generally accepted that the transport of Golgi products, including glycoproteins and complex polysaccharides, to the cell surface occurs by bulk flow (Hadlington and Denecke, 2000). To date, no specific signals responsible for targeting and transport of such products to the cell wall have been found associated with any protein or polysaccharide. It has been shown that Golgi-derived secretory vesicles mediating such a transport vary in size and are capable of carrying mixed classes of complex polysaccharides (Sherrier and VandenBosch, 1994) or both polysaccharides and glycoproteins (see Driouich et al., 1994). Nevertheless, using secretory carrier membrane protein 2 (SCAMP2) from Nicotiana tabacum, a mobile secretory vesicle cluster (SVC) generated from the TGN has been recently identified in Arabidopsis tissues and tobacco suspension-cultured BY-2 cells (Toyooka et al., 2009). These clusters formed by budding of clathrin coated vesicles from the late TGN, are highly labeled with antibodies specific for either complex glycan or homogalacturonan epitopes (JIM7), suggesting that SVC are involved in mass transport from Golgi stacks to the cell surface. It is also possible that the processing of Golgi products such as cell wall polymers may continue to occur within the vesicles during their transport to the cell surface (Zhang et al., 1996).

Glycosyltransferases and Sugar-Converting Enzymes Involved in the Assembly of Complex Polysaccharides

The Golgi-mediated assembly of complex polysaccharides requires the action of a set of Golgi glycosyltransferases, in addition to nucleotide–sugar transporters and nucleotide–sugar interconversion enzymes (Keegstra and Raikhel, 2001; Seifert, 2004; Reiter, 2008; Reyes and Orellana, 2008). It has been postulated that these partners could interact physically to form complexes within Golgi membranes that would coordinate sugar supply and polymer synthesis (Seifert, 2004; Nguema-Ona et al., 2006).

Xyloglucan biosynthesis: Glycosyltransferases and other proteins

XyG biosynthesis has long been an interesting, but a challenging, area of investigation. Biosynthesis of the XyG core is expected to require two different catalytic activities, a glucan synthase activity for the backbone and a xylosyltransferase activity adding xylosyl substitutions. Interestingly, Ray (1980) suggested a “cooperative action of β-glucan synthase and UDP-xylose xylosyltransferase in Golgi membranes for the synthesis of a XyG-like polysaccharide.” In that study, a UDP-xylose xylosyltransferase activity was measured in Golgi membranes isolated from pea, and the incorporation of xylose was shown to be stimulated by the addition of UDP-glucose. Furthermore, the stimulating effect of UDP-glucose on xylosyltransferase activity was shown to occur only in a pH range where β-glucan synthase is active, suggesting that UDP-glucose stimulates UDP-xylose incorporation by promoting β-glucan synthase activity. Here, the β-glucan synthase produces the required β-1,4-glucan substrate molecule necessary for XyG xylosyltransferase activity. At about the same time, Hayashi and Matsuda (1981a,b) performed a detailed characterization of XyG synthase activity in soybean suspension-cultured cells and demonstrated that XyG synthesis requires the cooperation of XyG β-1,4-glucan synthase and the XyG xylosyltransferase. The authors not only demonstrated that the incorporation of one sugar (xylose or glucose) depended on the presence of the other, but also that xylose was not transferred to a preformed β-1,4-glucan. This observation strongly supports the existence of a multienzyme complex responsible for XyG biosynthesis where glucan synthase and xylosyltransferase activities cooperate tightly (Hayashi, 1989). Since then, considerable efforts have been devoted to the characterization of XyG biosynthesis at the molecular level using functional genomics and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Lerouxel et al., 2006; Scheller and Ulvskov, 2010).

We have currently gained a better picture of XyG biosynthesis by identifying and characterizing some of the genes involved (Table 1), although without much (if any) understanding of how these enzymes could potentially cooperate to achieve the biosynthesis. For example, the XyG fucosyltransferase AtFUT1 (CAZy GT37, Cantarel et al., 2009) was the first type II glycosyltransferase characterized at the biochemical level (Perrin et al., 1999), and for a long time the only member of this gene family containing nine putative glycosyltransferases to be characterized, as analyses of three other members failed to demonstrate any XyG fucosylation activity (Sarria et al., 2001). Wu et al. (2010) have recently demonstrated the involvement of AtFUT4 and AtFUT6 genes in arabinogalactan proteins fucosylation.

Table 1.

List and characteristics of the glycosyltransferase and nucleotide–sugar interconversion enzymes.

| Gene |

Enzyme characteristics |

Arabidopsis mutant |

Notes |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Code | CAZy | Activity | Localization | Designation | Phenotypes | Category | Reference | |

| AtCSLC4 | At3g28180 | GT2 | β-l,4-Glucan synthase | Golgi | None | None | Cocuron et al. (2007) | ||

| AtXT1 | At3g62720 | GT34 | α-1,6-Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | xxt1 | 10% Reduction in XyG | xxt1 xxt2 Double mutant lacks | Faik et al. (2002), Cavalier and Keegstra (2006), Cavalier et al. (2008) | |

| AtXT2 | At4g02500 | GT34 | α-1,6-Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | xxt1 | 20% Reduction in XyG | Detectable amountof XyG | Xyloglucan | Cavalier and Keegstra (2006), Cavalier et al. (2008) |

| AtMUR3 | At2g20370 | GT47 | β-1,2-Galactosyltransferase | Golgi | mur3 | Hypocotyls wall strength is 50% reduced, xyloglucan lacks fucogalactosyl sidechain | Madson et al. (2003), Pena et al. (2004) | ||

| AtFUT1 | At2g03220 | GT37 | α-1,2-Fucosyltransferase | Golgi | Mur2 | Hypocotyls wall strength is slightly reduced, xyloglucan lacks fucose substitution | Perrin et al. (1999), Vanzin et al. (2002) | ||

| AXY4 | Atlg70230 | GT | O-Acetyltransferase | Golgi | axy4 | Cell wall XyG extract is non-acetylated | Pena et al. (2004), Gille et al. (2011) | ||

| AtFUT4 | At2gl5390 | GT37 | α-1,2-Fucosyltransferase | Golgi | None | None | Arabinogalactan proteins | ||

| AtFUT6 | Atlgl4080 | GT37 | α-1,2-Fucosyltransferase putative | Golgi | None | None | |||

| AtQUA1 | At3g25140 | GT8 | α-1,4-Galacturonosyltransferase | Predicted Golgi | qua1 | Dwarf, reduced cell adhesion, 25% reduction in cell wall GalA content | Bouton et al. (2002) | ||

| AtGAUT1 | At3g61130 | GT8 | α-1,4-Galacturonosyltransferase | Golgi | None | None | Sterling et al. (2006), Dunkley et al. (2004) | ||

| AtRGXT1 | At4g01770 | GT77 | α-1,3-Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | rgxt1 | RG-II from mutant (but not from WT) is an acceptor for a-l,3-xylosyltransferase acitvity | Egelund et al. (2006) | ||

| AtRGXT2 | At4g01750 | GT77 | α-1,3-Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | rgxt2 | RG-II from mutant (but not from WT) is an acceptor for a-l,3-xylosyltransferase acitvity | Egelund et al. (2006) | ||

| AtRGXT4 | At4g01220 | GT77 | Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | mgp4 | Defective for root and pollen tube growth | Fangel et al. (2011), Liu et al. (2011) | ||

| AtARAD1 | At2g35100 | GT47 | α-1,5-Arabinosyltransferase | Predicted Golgi | arad1 | Cell wall composition altered, decrease in RG-I arabinose content | Pectins | Harholt et al. (2006) | |

| AtXGD1 | At5g33290 | GT47 | β-1,3-Xylosyltransferase | Golgi | xgd1 | xgd1 mutant lacks detectable XGA in pectin enriched fraction | Jensen et al. (2008) | ||

| NpGUT1 | – | GT47 | Putative β-glucuronytransferase | Predicted Golgi | nolac-H18 | Callus harbored a cell-cell adhesion defect, and a reduced RG-II dimerisation ability | Iwai et al. (2002) | ||

| AtEPC1 | At3g55830 | GT64 | Unknown | Predicted Golgi | epc1 | Reduced growth habit, defects in vascular formation and reduced cell-cell adhesion in hypocotyls | Singh et al. (2005) | ||

| AtQUA2 | Atlg78240 | – | Putative methyltransferase | Golgi | qua2/tsd2 | Dwarf, reduced cell adhesion, 50% reduction in HG content | Mouille et al. (2007), Krupková et al. (2007) | ||

| AtQUA3 | At4g00740 | Putative methyltransferase | Golgi | qua3 | No detectable phenotype | Miao et al. (2011) | |||

| AtCGR3 | At5g65810 | – | Putative methyltransferase | Golgi | cgr3 | Decrease HG methylesterification | Held et al. (2011) | ||

| AtUGE4 | Atlg64440 | UDP-glucose epimerase | Cytosolic and Golgi associated | rhd1 (uge4); reb1 | Reduced root elongation rate, bulging of trichoblast cells, xyloglucan, and arabinogalactan galactosylation defects in roots | Andème-Onzighi et al. (2002), Seifert et al. (2002), Barber et al. (2006), Nguema-Ona et al. (2006) | |||

| AtRGP1 | At3g02230 | GT75 | Putative UDP-arabinopyranose mutase | Cytosolic and Golgi associated | rgp1 | Decrease in L-Ara, l development altered | rgp1 rgp2 double mutant is lethal (pollen development altered) | Interconversion enzymes | Rautengarten et al. (2011) |

| AtRGP2 | At5gl5650 | GT75 | Putative UDP-arabinopyranose mutase | Cytosolic and Golgi associated | rgp2 | Decrease in L-Ara | hpRGP1/2 cell wall is deficient in L-Ara | ||

arad1, arabinose deficient 1; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; CSLC4, cellulose synthase-like C4; cgr3, cotton golgi-related 3; epc1, ectopically parting cells1; FUT, fucosyltransferase; hpRGP1/2, hairpin construct targeting RGP1 and RGP2 genes; mgp4, male gametophyte defective 4; nolac-H18, non-organogenic callus with loosely attached cells-H18; Np, Nicotiana plumbaginifolia; qua1, quasimodo1; qua2, quasimodo2; reb1, root epidermal bulging1;rgp1, reversibly glycosylated protein1; rgp2, reversibly glycosylated protein2; rhd1, root hair deficent1; rgxt1, rhamnogalacturonane II xylosyltransferase1; rgxt2, rhamnogalacturonan II xylosyltransferase2; xgd1, xylogalacturonan deficient1; xxt1, xyloglucan xylosyltransferase1; xxt2, xyloglucan xylosyltransferase2.

Later, the identification and characterization of the mur2 mutant of Arabidopsis provided the unequivocal proof that the AtFUT1 gene encodes the unique α-1,2-fucosyltransferase activity responsible for XyG fucosylation in Arabidopsis plants (Vanzin et al., 2002). Likewise, one XyG β-1,2-galactosyltransferase (AtMUR3; CAZy GT47) activity was successfully characterized using both mutant analysis (mur3) and heterologous expression of the enzyme (Madson et al., 2003). Nevertheless, as the galactose residue of the XyG molecule can be found in two different positions, it seems that at least one XyG galactosyltransferase remains to be identified and characterized. The galactosyl-residues of XyG are known to be O-acetylated and only one XyG-O-acetyltransferase (AXY4) has been identified so far (Gille et al., 2011) and found to be localized within Golgi stacks.

An important contribution to understanding XyG biosynthesis was also made by the characterization of two α-1,6-xylosyltransferase activities required for XyG xylosylation (CAZy GT34). First, one xylosyltransferase activity (named AtXT1) was identified based on sequence homology with a previously identified α-1,6-galactosyltransferase from fenugreek (Edwards et al., 1999), and characterized as an α-1,6-xylosyltransferase using heterologous expression in Pichia pastoris (Faik et al., 2002). Cavalier and Keegstra (2006) extended this work to the characterization of a second xylosyltransferase activity (named AtXT2), encoded by a gene closely related to AtXT1, that promotes an identical reaction to the one catalyzed by AtXT1. Interestingly, the authors also demonstrated that both AtXT1 and AtXT2 are able to catalyze multiple addition of xylosyl residues onto contiguous glucosyl residues of a cellohexaose acceptor in vitro (even though the β-linkage introduce a 180° rotation from one glucosyl residue to the other), but non-xylosylated cellohexaose was the preferred acceptor. The observation that both AtXT1 and AtXT2 xylosyltransferase activities were able to perform multiple xylosylation might indicate a reduced substrate specificity of these enzymes as compared to the high specificity of the XyG fucosyl- or galactosyl-transferases. Nevertheless, these results raise the intriguing possibility that AtXT1 and AtXT2 would be fully redundant in planta and that both would be able to perform multiple xylosylation. Such a hypothesis is consistent with the characterization of an Arabidopsis double mutant for AtXT1 and AtXT2 genes (named xxt1 xxt2; xyloglucan xylosyltransferase 1 and 2), which is lacking detectable amounts of XyG in planta (Cavalier et al., 2008).

Another enzyme involved in XyG biosynthesis is glucan synthase. While XyG glucan synthase activity has long been studied biochemically (discussed above), efforts to purify and ultimately characterize this enzyme have not been successful. A gene from the Cellulose Synthase-Like C family (AtCSLC4; CAZy GT2) was shown to encode a Golgi-localized β-1,4-glucan synthase activity providing a strong candidate for the, as yet, unidentified XyG β-glucan synthase (Cocuron et al., 2007). The candidate gene was identified using a transcriptional profiling strategy taking advantage of nasturtium’s capacity to perform rapidly XyG biosynthesis during seed development (Desveaux et al., 1998). This observation supports the hypothesis that the β-1,4-glucan synthase activity identified was involved in XyG biosynthesis. Interestingly, this study also indicates that AtCSLC4 is co-regulated with AtXT1 at the transcriptional level and that some degree of interaction occurs at the protein level could possibly alter the length of the β-1,4-glucan synthesized by the AtCSLC4 protein (Cocuron et al., 2007). The results of this study are consistent with earlier reports showing that in vitro synthesis of XyG was shown to involve a cooperative action between the glucan synthase and the xylosyltransferase activities (Hayashi, 1989). Recently, the topology of AtCSLC4 was examined using protease protection experiments (Davis et al., 2010). AtCSLC4 was predicted to have six transmembrane domains and the active site facing the cytosol. These data suggest that AtCSLC4 protein would delimitate a pore, the glucan chain being synthesized at the cytosolic side of Golgi cisternae, translocated into the lumen and further substituted by an α-1,6-xylosyltransferase to prevent β-1,4-glucan chain aggregation. A physical cooperation between AtCSLC4 and AtXT1 or AtXT2 could then be envisioned to rationalize this process. Recently, Chevalier et al. (2010) have shown that AtXT1–GFP is mainly associated with cis and medial Golgi cisternae in transformed tobacco suspension-cultured (BY-2) cells. A similar approach to localize the AtCSL4 would be highly instructive. Another approach would be the design of a tagged version of either AtXT1 or AtXT2, taking advantage of the characterization of xxt1/xxt2 double mutant (Cavalier et al., 2008) and further use the tagged version of the xylosyltransferases to pull down interacting candidate proteins. Then the interaction could be examined using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) approach as previously performed for cellulose biosynthesis (Desprez et al., 2007).

XyG biosynthesis does not only depend upon the cooperation between glycosyltransferase activities, but might also require close interaction between glycosyltransferases and nucleotide–sugar interconversion enzymes. The study on the reb1/rhd1 mutant of Arabidopsis, deficient in one of the five UDP-glucose 4-epimerase isoforms (UGE4) involved in the synthesis of UDP-d-galactose, provided indirect evidence for a possible interaction between UGE4 and a XyG-β-1,2-galactosyltransferase (Nguema-Ona et al., 2006). The authors showed that the galactosylation of XyG, unlike that of pectins (RG-I and RG-II), was absent in specific cells of the mutant and that UGE4 and XyG- β-1,2-galactosyltransferase are co-expressed at the transcriptional level in the root. Thus, it was postulated that the two enzymes might be associated in specific protein complexes involved in the galactosylation of XyG within Golgi membranes. Such an association could be required for an efficient galactosylation of XyG, where UGE4 would channel UDP-Gal to XyG-galactosyl-transferases. The existence of such a hypothetical association was supported by the demonstration that UGE4 was not only present in the cytoplasm but also found associated with Golgi membranes (Barber et al., 2006).

Although it is not the focus of this review, it is of interest to note that some glycosylhydrolases involved in XyG modification have been identified and characterized (Sampedro et al., 2001, 2012; Günl and Pauly, 2011; Günl et al., 2011). These are known to be transported via Golgi-derived vesicles to the apoplastic compartment where they act on the polymers. However, whether these enzymes are transported in the same Golgi vesicles and whether they are able to act on polymers within the vesicles during transport remain to be elucidated.

Pectin biosynthesis: Toward identification of the glycosyltransferases involved

Because there is a considerable diversity of monosaccharide units and glycosidic linkages making up pectic polysaccharides, it has been proposed that a minimum of 67 glycosyltransferases would be needed for pectin biosynthesis (Mohnen, 2008). In addition, the complexity of pectic polysaccharides has made the identification and characterization of such glycosyltransferases difficult and, consequently, only a handful have been assigned precise biochemical functions (Egelund et al., 2006; Sterling et al., 2006; Jensen et al., 2008) or suggested to have certain functions (Iwai et al., 2001, 2002; Bouton et al., 2002; Harholt et al., 2006, 2010; Egelund et al., 2007; Fangel et al., 2011; Held et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011). An additional degree of complexity in pectin synthesis is related to the control of the homogalacturonan methylesterification that requires specific methyltransferase activities, but also specific esterases to adjust methyl-esterification level during plant development (Wolf et al., 2009).

As for XyG biosynthesis, many biochemical studies have been devoted to the characterization of the enzymes involved in HG biosynthesis (Doong and Mohnen, 1998; Scheller et al., 1999). These studies showed that α-1,4-galacturonosyltransferase (GalAT) and HG methyltransferase activities are located in the lumen of isolated Golgi membranes (Goubet and Mohnen, 1999; Sterling et al., 2001). A HG-GalAT activity was partially purified from solubilized membrane proteins isolated from Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells and trypsin-digested peptides sequencing led to the identification of a candidate gene, named AtGAUT1 for GAlactUronosylTransferase1 (Sterling et al., 2006). Genome analysis revealed that AtGAUT1 belongs to a large gene family comprising 25 members in Arabidopsis that is present in CAZy GT8 along with galactinol synthases and bacterial α-galactosyltransferase (Yin et al., 2010). Among the 25 homolog genes to AtGAUT1 in the Arabidopsis genome, two distinct group have been described for the GAUT genes and the GAUT-related genes (GATL), which comprise 15 and 10 genes, respectively (Sterling et al., 2006). Heterologous expression of AtGAUT1 in human embryonic kidney cells, showed that AtGAUT1 cDNA encodes a galacturonosyltransferase activity able to transfer radiolabeled GalA onto α-1,4-oligogalacturonide acceptors, whereas the heterologous expression of AtGAUT7 cDNA (36% amino-acid sequence identity with AtGAUT1) carried out in parallel did not yield any transferase activity. More recently, Atmodjo et al. (2011) have demonstrated that the association of AtGAUT1 with AtGAUT7 is necessary to retain GAUT1 galacturonosyltransferase activity in Golgi membranes. In that study the authors have proposed that two GAUT1 proteins would remain associated to each other (and thus retain) via one GAUT7 protein anchored in the Golgi membrane. However, whether the AtGAUT1 activity is directly responsible for the biosynthesis of the backbone of HG or that of RG-II polysaccharide in Arabidopsis has not been determined. Characterization of cell wall composition of Arabidopsis mutants altered for 13 out of the 15 GAUT genes and 3 of the 10 GATL genes has failed to clearly establish which polysaccharide is affected (Caffal et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2011).

The Arabidopsis mutant quasimodo1 (qua1) is characterized by a reduced cell adhesion phenotype combined with a 25% decrease in cell wall galacturonic acid content, supporting the hypothesis that the AtQUA1 gene encodes a putative glycosyltransferase activity involved in pectin biosynthesis (Bouton et al., 2002; Durand et al., 2009). AtQUA1 (also named AtGAUT8) belongs to CAZy GT 8 family and shows 77% similarity to AtGAUT1 which has a characterized HG-galacturonosyltransferase activity (Sterling et al., 2006). In addition, α-1,4-galacturonosyltransferase activity was shown to be significantly reduced in qua1 providing further support for AtQUA1 involvement in pectin biosynthesis (Orfila et al., 2005). Another Arabidopsis mutant quasimodo2 (qua2), having a 50% decrease in HG content, has been described (Mouille et al., 2007). Interestingly, AtQUA2 does not show any similarity with other glycosyltransferases, but it is a Golgi-localized protein (Figure 2) that contains a putative S-adenosyl methionine dependent methyltransferase domain, and appears strongly co-regulated with AtQUA1. This study supports the hypothesis that AtQUA2 is a pectin methyltransferase required for HG biosynthesis and that both enzymes work interdependently. The observation that an alteration in a putative methyltransferase can impair HG synthesis led the authors to suggest the existence of a protein complex containing galacturonosyltransferase and methyltransferase where the latter enzyme would be essential for the functioning of the protein complex (Mouille et al., 2007). Whereas Arabidopsis genome contains 29 putative genes encoding for pectin methyltransferases (Krupková et al., 2007), in addition to the AtQUA2, a novel putative S-adenosyl methionine dependent HG methyltransferase, showing a high amino-acid similarity with AtQUA2, the AtQUA3 has been recently characterized (Miao et al., 2011). AtQUA3 is a Golgi-localized type II membrane protein which is highly expressed and abundant in Arabidopsis suspension-cultured cells. More recently, it has been shown that AtQUA3 is co-expressed with AtGAUT1 and AtGAUT7; supporting the idea that HG methylation is closely associated with HG synthesis (Atmodjo et al., 2011). In addition, Held et al. (2011) have identified an Arabidopsis ortholog of a cotton protein containing a domain similar to SAM methyltransferase domain named cotton Golgi-related 3 (CGR3) involved in the methylesterification of HG. Finally, a third Arabidopsis mutant – ectopically parting cells 1 (epc1) – was characterized on the basis of cell adhesion defects, however cell wall analyses did not support the hypothesis that pectin biosynthesis was specifically altered in epc1 (Singh et al., 2005).

The HG backbone in Arabidopsis can also be decorated with β-1,3-xylose residues thus forming a xylogalacturonan domain (Zandleven et al., 2007). The characterization of the xylogalacturonan deficient1 (xgd1) Arabidopsis mutant along with the heterologous expression of XGD1 protein in Nicotiana benthamiana led to the demonstration that the XGD1 gene is involved in XGA biosynthesis (Jensen et al., 2008).

Four other genes involved in pectin biosynthesis, encoding a small glycosyltransferase family with four members named RG-II xylosyltransferase (RGXT1–4; CAZy GT77), have been described (Egelund et al., 2006, 2008; Fangel et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2011). The authors convincingly demonstrated that AtRGXT1, AtRGXT2, AtRGXT3, and AtRGXT4 encode α-1,3-xylosyltransferase activities that are involved in the synthesis of the pectic polysaccharide RG-II. Whereas no mutant has been found for RGXT3 (Egelund et al., 2008), Arabidopsis mutants have been described for RGXT1, RGXT2 (Egelund et al., 2006) and RGXT4 (Liu et al., 2011). Among these, only rgxt4 mutant, also named male gametophyte defective 4 (mgd4), presents visible phenotypes in both RG-II structure and pollen tube growth (Liu et al., 2011). The peculiar role of RGXT4 could be explained by its ubiquitous expression in vegetative and reproductive organs whereas RGXT1 and RGXT2 expression is restricted to the vegetative organs. Other genes have also been proposed to function in pectin biosynthesis although their involvement has not been firmly established. Mutant lines altered in pectin biosynthesis have been screened based on cell adhesion defects – a process that involves pectin (Iwai et al., 2001, 2002; Bouton et al., 2002; Mouille et al., 2007). A gene named NpGUT1, for Nicotiana plmbaginifolia glucuronyltransferase 1, has been identified using nolac-H18, a tobacco callus mutant line that exhibits a “loosely attached cells” phenotype (Iwai et al., 2002). It was proposed that NpGUT1 encodes a putative glucuronyltransferase involved in RG-II biosynthesis based on the analysis of nolac-H18 mutant cell walls. However, recent studies have shown that homologs of Arabidopsis NpGUT1 are related to the biosynthesis of the hemicellulosic polysaccharide glucuronoxylan rather than to that of RG-II (Wu et al., 2009).

As compared to HG and RG-II biosynthesis, relatively little is known about the glycosyltransferases involved in RG-I biosynthesis and only one glycosyltransferase has been characterized so far. A reverse genetics approach with putative glycosyltransferases from the CAZy GT47 family led to the identification of the arabinan deficient 1 (arad1) mutant of Arabidopsis showing a reduced arabinose content in the cell wall (Harholt et al., 2006) Characterization of the arad1 cell wall demonstrated that the ARAD1 gene probably encodes an arabinan α-1,5-arabinosyltransferase activity important for RG-I biosynthesis. Another Golgi glycosyltransferase of GT47 family sharing a high homology with ARAD1, named ARAD2, has been recently characterized (Harholt et al., 2012). Using biochemical and microscopical approaches, the study has revealed that ARAD1 and ARAD2 form homo and heterodimers when they are co-expressed in N. benthamiana plants (Harholt et al., 2012). It is interesting to note that although arabinofuranose is normally incorporated in RG-I during its biosynthesis in planta, it is the arabinopyranose that is actually incorporated during in vitro assays, using detergent-solubilized membranes. To explain this discrepancy between in planta and in vitro observations, it has been hypothesized that a mutase activity responsible for the conversion is lost upon solubilization (Nunan and Scheller, 2003). A UDP-arabinose mutase (UAM) that converts UDP-arabinopyranose into UDP-arabinofuranose was characterized in rice (Konishi et al., 2007) and found to share more than 80% identity with the reversibly glycosylated proteins (RGPs) of Arabidopsis that have long been known to be cytosolic proteins capable of associating with Golgi membranes (Dhugga et al., 1991, 1997; Delgado et al., 1998). Based on the fact that RGPs can be reversibly glycosylated by glucose, xylose, and galactose residues, it has been postulated that they could be involved in XyG or xylan biosynthesis. Among the five isoforms of RGPs (RGP1–5) identified in the Arabidopsis genome, the mutase activity has been recently shown for AtRGP1, AtRGP2, and AtRGP3 (Rautengarten et al., 2011). This UAM activity of RGPs suggests their potential role in the biosynthesis of arabinofuranosyl-containing polymers such pectin or arabinogalactan proteins. A double mutant rgp1/rgp2 was shown to harbor pollen development defects, thereby leading the authors to hypothesize that RGPs might be involved in cell wall polysaccharide biosynthesis (Drakakaki et al., 2006). Moreover, Rautengarten et al. (2011) analyzed the phenotype of homozygous T-DNA insertion mutants (rgp1–1 and rgp1–2), and described severe developmental phenotypes associated with subsequent reduction (≥69%) in cell wall arabinose content.

Concluding Remarks

The knowledge of XyG and pectin biosynthesis has progressed significantly over the past 10 years with respect to the identification of the enzymes involved in their biosynthesis, using functional genomics. The challenge now is, to determine how these players (and partners) cooperate, in a timely and probably spatially resolved manner, in order to achieve the coordinated and efficient synthesis of these polymers.

In plants, the only approach that has so far provided evidence for the compartmental organization of the Golgi with regards to complex polysaccharide biosynthesis is immunogold microscopy using antibodies raised against specific sugars of different polysaccharides (Follet-Gueye et al., 2012). Now we need to move forward with studies addressing how the glycosyltransferases are distributed within plant Golgi stacks and to determine whether distinct enzymes are preferentially compartmentalized within distinct Golgi cisternae, or if they are always localized in all Golgi sub-compartments and in all cell types. Another interesting issue relates to whether glycohydrolases are able to act on polysaccharides within Golgi-derived vesicles before secretion. Finally, in light of the recent identification of glycosyltransferase complexes involved in HG and arabinan synthesis (Atmodjo et al., 2011; Harholt et al., 2012), as well determination of their membrane topologies (Søgaard et al., 2012), it is of special interest to understand location and interactions of glycosyltransferases with partners including nucleotide–sugar interconversion enzymes and sugar transporters within Golgi membranes. Clearly, a better understanding of such interactions, their dynamics along with membrane topologies of the enzymes and their distribution within Golgi cisternae will provide new mechanistic insights into the biosynthesis and secretion of cell wall polysaccharides in flowering plants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Very special thanks are due to Pr. A. Staehelin (who retired recently) for having passionately launched AD onto the path of plant Golgi research. The authors wish to thank Pr. S. Hawkins and Dr. J. Moore for their critical reading of the manuscript as well as Pr. B. H. Kang for providing Figure 1D. We also thank Dr. G. Mouille (INRA, Versailles) for providing the GFP-QUA2 line. Work in AD laboratory is supported by the University of Rouen, le Conseil Régional de Haute Normandie via le Grand Réseau de Recherche VASI (Végétal, Agronomie, Sol, Innovation), le CNRS and l’ANR.

References

- Andème-Onzighi C., Sivaguru M., Judy-March J., Baskin T. I., Driouich A. (2002). The reb1-1 mutation of Arabidopsis alters the morphology of trichoblasts, the expression of arabinogalactan-proteins and the organization of cortical microtubules. Planta 215, 949–958 10.1007/s00425-002-0836-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabidopsis Genome Initiative (2000). Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 408, 796–815 10.1038/35048692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmodjo M. A., Sakuragi Y., Zhu X., Burell A. J., Mohanty S. S., Atwood J. A., III, Orlando R., Scheller H. V., Mohnen D. (2011). Galacturonosyltransferase (GAUT)1 and GAUT7 are the core of a plant cell wall pectin biosynthetic homogalacturonan:galacturonosyltransferase complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20225–20230 10.1073/pnas.1112816108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber C., Rösti J., Rawat A., Findlay K., Roberts K., Seifert G. J. (2006). Distinct properties of the five UDP-D-glucose/UDP-D-galactose 4-epimerase isoforms of Arabidopsis thaliana. 281, 17276–17285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boevink P., Oparka K., Sant Cruz S., Martin B., Betteridge A., Hawes C. (1998). Stacks on tracks: the plant Golgi apparatus traffics on an actin/ER network. Plant J. 15, 441–447 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton S., Leboeuf E., Mouille G., Leydecker M. T., Talbotec J., Granier F., Lahaye M., Höfte H., Truong H. N. (2002). QUASIMODO1 encodes a putative membrane-bound glycosyltransferase required for normal pectin synthesis and cell adhesion in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 14, 2577–2590 10.1105/tpc.004259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandizzi F., Snapp E. L., Roberts A. G., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Hawes C. (2002). Membrane protein transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi in tobacco leaves is energy dependent but cytoskeleton independent: evidence from selective photobleaching. Plant Cell 14, 1293–1309 10.1105/tpc.000620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummell D. A., Camirand A., Maclachlan G. A. (1990). Differential distribution of xyloglucan glycosyl transferases in pea Golgi dictyosomes and secretory vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 96, 705–710 [Google Scholar]

- Burton R. A., Gidley M. J., Fincher G. B. (2010). Heterogeneity in the chemistry, structure and function of plant cell walls. Nat. Chem. Biol. 724–732 10.1038/nchembio.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffal K. H., Pattathil S., Phillips S. E., Hahn M. G., Mohnen D. (2009). Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutants implicate GAUT genesin the biosynthesis of pectin and xylan in cell walls and seed testa. Mol. Plant 2, 1000–1014 10.1093/mp/ssp062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camirand A., Brummell D. A., Maclachlan G. A. (1987). Fucosylation of xyloglucan: localization of the transferase in dictyosomes of pea stem cells. Plant Physiol. 113, 487–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009). The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 10.1093/nar/gkn663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N. C., Gibeaut D. M. (1993). Structural models of primary cells in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 3, 1–30 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1993.00999.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier D. M., Keegstra K. (2006). Two xyloglucan xylosyltransferases catalyze the addition of multiple xylosyl residues to cellohexaose. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34197–34207 10.1074/jbc.M606379200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier D. M., Lerouxel O., Neumetzler L., Yamauchi K., Reinecke A., Freshour G., Zabotina O. A., Hahn M. G., Burgert I., Pauly M., Raikhel N. V., Keegstra K. (2008). Disrupting Two Arabidopsis thaliana xylosyltransferase genes results in plants deficient in xyloglucan, a major primary cell wall component. Plant Cell 20, 1519–1537 10.1105/tpc.108.059873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier L., Bernard S., Ramdani Y., Lamour R., Bardor M., Lerouge P., Follet-Gueye M. L., Driouich A. (2010). Subcompartment localization of the side chain xyloglucan-synthesizing enzymes within Golgi stacks of tobacco suspension-cultured cells. Plant J. 64, 977–989 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocuron J. C., Lerouxel O., Drakakaki G., Alonso A. P., Liepman A. H., Keegstra K., Raikhel N., Wilkerson C. G. (2007). A gene from the cellulose synthase-like C family encodes a beta-1,4 glucan synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8550–8555 10.1073/pnas.0703133104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (2005). Growth of the plant cell wall. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 850–861 10.1038/nrm1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove D. J. (1999). Enzymes and others agents that enhance cell wall extensibility. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 391–417 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler S. R., Ehrhardt D. W. (2002). Polarized cytokinesis in vacuolate cells of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 2812–2817 10.1073/pnas.052712299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darvill J. E., McNeil M., Darvill A. G., Albersheim P. (1980). Structure of Plant Cell Walls: XI. Glucuronoarabinoxylan, a second hemicellulose in the primary cell walls of suspension-cultured sycamore cells. Plant Physiol. 66, 1135–1139 10.1104/pp.66.6.1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauwalder M., Whaley W. G. (1974). Patterns of incorporation of (3H)galactose by cells of Zea mays root tips. J. Cell Sci. 14, 11–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J., Brandizzi F., Liepman A. H., Keegstra K. (2010). Arabidopsis mannan synthase CSLA9 and glucan synthase CSLC4 have opposite orientations in the Golgi membrane. Plant J. 64, 1028–1037 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado I. J., Wang Z., de Rocher A., Keegstra K., Raikhel N. V. (1998). Cloning and characterization of AtRGP1. A reversibly autoglycosylated Arabidopsis protein implicated in cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 116, 1339–1350 10.1104/pp.116.4.1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez T., Juraniec M., Crowell E. F., Jouy H., Pochylova Z., Höfte H., Gonneau M., Vernhettes S. (2007). Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15572–15577 10.1073/pnas.0706569104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desveaux D., Faik A., Maclachlan G. (1998). Fucosyltransferase and the biosynthesis of storage and structural xyloglucan in developing nasturtium fruits. Plant Physiol. 118, 885–894 10.1104/pp.118.3.885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer J., Hong-Hermesdorf A., Stierhof Y. D., Schumacher K. (2006). Vacuolar H+-ATPase activity is required for endocytic and secretory trafficking in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 715–730 10.1105/tpc.105.037978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga K. S., Tiwari S. C., Ray P. M. (1997). A reversibly glycosylated polypeptide (RGP1) possibly involved in plant cell wall synthesis: purification, gene cloning, and trans-Golgi localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7679–7684 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga K. S., Ulskov P., Gallagher S. R., Ray P. M. (1991). Plant Polypeptide reversibly glycosylated by UDP-glucose. Possible components of Golgi beta-glucan synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 94, 7679–7684 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doong R. L., Mohnen D. (1998). Solubilization and characterization of a galacturonosyltransferase that synthesizes the pectic polysaccharide homogalacturonan. Plant J. 13, 363–374 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1998.00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drakakaki G., Zabotina O., Delgado I., Robert S., Keegstra K., Raikhel N. (2006). Arabidopsis reversibly glycosylated polypeptides 1 and 2 are essential for pollen development. Plant Physiol. 142, 1480–1492 10.1104/pp.106.086363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A., Faye L., Staehelin L. A. (1993). The plant Golgi apparatus: a factory for complex polysaccharides and glycoproteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 18, 210–214 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90191-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A., Levy S., Staehelin L. A., Faye L. (1994). Structural and functional organization of the Golgi apparatus in plant cells. Plant Physiol. 32, 731–749 [Google Scholar]

- Driouich A., Staehelin L. A. (1997). “The plant Golgi apparatus: Structural organization and functional properties,” in The Golgi Apparatus, ed. Berger E. G. (Basel: J. Roth Birkhauser; ), 275–301 [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley T. P., Hester S., Shadforth I. P., Runions J., Weimar T., Hanton S. L., Griffin J. L., Bessant C., Brandizzi F., Hawes C., Watson R. B., Dupree P., Lilley K. S. (2006). Mapping the Arabidopsis organelle proteome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 6518–6523 10.1073/pnas.0506958103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkley T. P. J., Watson R., Griffin J. L., Dupree P., Lilley K. S. (2004). Localization of organelle proteins by isotope tagging (LOPIT). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3, 1128–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand C., Vicré-Gibouin M., Moreau M., Duponchel L., Follet-Gueye M. L., Lerouge P., Driouich A. (2009). The organization pattern of root border-like cells in Arabidopsis is dependent on homogalacturonan. Plant Physiol. 150, 1411–1421 10.1104/pp.109.136382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M. E., Dickson C. A., Chengappa S., Sidebottom C., Gidley M. J., Reid J. S. (1999). Molecular characterization of a membrane-bound galactosyltransferase of plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant J. 19, 691–697 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00566.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelund J., Damager I., Faber K., Olsen C. E., Ulvskov P., Petersen B. L. (2008). Functional characterisation of a putative rhamnogalacturonan II specific xylosyltransferase. FEBS Lett. 582, 3217–3222 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelund J., Obel N., Ulvskov P., Geshi N., Pauly M., Bacic A., Petersen B. L. (2007). Molecular characterization of two Arabidopsis thaliana glycosyltransferase mutants, rra1 and rra2, which have a reduced residual arabinose content in a polymer tightly associated with the cellulosic wall residue. Plant Mol. Biol. 64, 439–451 10.1007/s11103-007-9162-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelund J., Petersen B. L., Motawia M. S., Damager I., Faik A., Olsen C. E., Ishii T., Clausen H., Ulvskov P., Geshi N. (2006). Arabidopsis thaliana RGXT1 and RGXT2 encode Golgi-localized (1,3)-alpha-D-xylosyltransferases involved in the synthesis of pectic rhamnogalacturonan-II. Plant Cell 18, 2593–2607 10.1105/tpc.105.036566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faik A. (2010). Xylan biosynthesis: news from the grass. Plant Physiol. 153, 396–402 10.1104/pp.110.154237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faik A., Price N. J., Raikhel N. V., Keegstra K. (2002). An Arabidopsis gene encoding an alpha-xylosyltransferase involved in xyloglucan biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7797–7802 10.1073/pnas.102644799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fangel J. U., Petersen B. L., Jensen N. B., Willats W. G. T, Bacic, A., Egelund J. (2011). A putative Arabidopsis thaliana glycosyltransferase, At4g01220, which is closely related to three plant cell wall-specific xylosyltransferases, is differentially expressed spatially and temporally. Plant Sci. 180, 470–479 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follet-Gueye M. L., Mollet J. C., Vicré-Gibouin M., Bernard S., Chevalier L., Plancot B., Dardelle F., Ramdani Y., Coimbra S., Driouich A. (2012). “Immuno-glyco-imaging in plant cells: localization of cell wall carbohydrate epitopes and their biosynthesizing enzymes,” in Applications of Immunocytochemistry, ed. Dehghani H. (Rijeka: In Tech; ), 297–320 [Google Scholar]

- Follet-Gueye M. L., Pagny S., Faye L., Gomord V., Driouich A. (2003). An improved chemical fixation method suitable for immunogold localization of green fluorescent protein in the Golgi apparatus of tobacco Bright Yellow (BY-2) cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51, 931–940 10.1177/002215540305100708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner M., Chrispeels M. J. (1975). Involvement of the Golgi apparatus in the synthesis and secretion of hydroxyproline-rich cell wall glycoproteins. Plant Physiol. 55, 536–541 10.1104/pp.55.3.536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut D. M., Carpita N. C. (1994). Biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides. FASEB J. 8, 904–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille S., de Souza A., Xiong G., Benz M., Cheng K., Schultink A., Reca I. B., Pauly M. (2011). O-acetylation of Arabidopsis hemicellulose xyloglucan requires AXY4 or AXY4L, proteins with a TBL and DUF231 domain. Plant Cell 23, 4041–4053 10.1105/tpc.111.091728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubet F., Mohnen D. (1999). Solubilization and partial characterization of homogalacturonan-methyltransferase from microsomal membranes of suspension-cultured tobacco cells. Plant Physiol. 121, 281–290 10.1104/pp.121.1.281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. R., Northcote D. H. (1978). The structure and function of glycoproteins synthesized during slime-polysaccharide production by membranes of the root-cap cells of maize (Zea mays). Biochem. J. 170, 599–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M., Neumetzler L., Kraemer F., de Souza A., Schultink A., Pena M., York W. S., Pauly M. (2011). AXY8 encodes an (α-fucosidase, underscoring the importance of apoplastic metabolism on the fine structure of Arabidopsis cell wall polysaccharides. Plant Cell 23, 4025–4040 10.1105/tpc.111.089193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günl M., Pauly M. (2011). AXY3 encodes a (α-xylosidase that impacts the structure and accessibility of the hemicellulose xyloglucan in Arabidopsis plant cell walls. Planta 233, 707–719 10.1007/s00425-010-1330-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlington J. L., Denecke J. (2000). Sorting of soluble proteins in the secretory pathway of plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3, 461–468 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00114-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt J., Jensen J. K., Sørensen S. O., Orfila C., Pauly M., Scheller H. V. (2006). ARABINAN DEFICIENT 1 is a putative arabinosyltransferase involved in biosynthesis of pectic arabinan in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140, 49–58 10.1104/pp.105.072744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt J., Jensen J. K., Verhertbruggen Y., Casper Søgaard C., Bernard S., Nafisi M., Poulsen C. P., Geshi N., Sakuragi Y., Driouich A., Knox J. P., Vibe Scheller H. (2012). ARAD proteins associated with pectic Arabinan biosynthesis form complexes when transiently overexpressed in planta. Planta. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s00425-012-1592-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harholt J., Suttangkakul A., Vibe Scheller H. (2010). Biosynthesis of pectin. Plant Physiol. 153, 384–395 10.1104/pp.110.156588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. J., Northcote D. H. (1971). Polysaccharide formation in plant Golgi bodies. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 237, 56–64 10.1016/0304-4165(71)90029-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T. (1989). Xyloglucans in the primary cell wall. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 139–168 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.001035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Matsuda K. (1981a). Biosynthesis of xyloglucan in suspension-cultured soybean cells. Occurrence and some properties of xyloglucan 4-beta-D-glucosyltransferase and 6-alpha-D-xylosyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 11117–11122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T., Matsuda K. (1981b). Biosynthesis of Xyloglucan in Suspension-cultured soybean cells. Evidence that the enzyme system of xyloglucan synthesis does not contain ß-1,4-glucan 4-ß-D-glucosyltransferase activity (EC 2.4.1.12). Plant Cell Physiol. 22, 1571–1584 [Google Scholar]

- Held M. A., Be E., Zemelis S., Withers S., Wilkerson C., Brandizzi F. (2011). CGR3: a Golgi-localized protein influencing homogalacturonan methylesterification. Mol. Plant. 4, 832–844 10.1093/mp/ssr012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J. W., Kokini J. L. (1991). Structure and rheological function of side branches of carbohydrate polymers. J. Texture Stud. 22, 123–167 10.1111/j.1745-4603.1991.tb00011.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Rice Genome Sequencing Project (2005). The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature 436, 793–800 10.1038/nature03895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Matsunaga T. (1996). Isolation and characterization of a boron-rhamnogalacturonan II complex from cell walls of sugar beet pulp. Carbohydr. Res. 284, 1–9 10.1016/0008-6215(96)00010-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Matsunaga T., Hayashi N. (2001). Formation of Rhamnogalacturonan II-borate dimer in pectin determines cell wall thickness of pumpkin tissue. Plant Physiol. 126, 1698–1705 10.1104/pp.126.4.1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai H., Ishii T., Satoh S. (2001). Absence of arabinan in the side chains of the pectic polysaccharides strongly associated with cell walls of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia non-organogenic callus with loosely attached constituent cells. Planta 213, 907–915 10.1007/s004250100559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai H., Masaoka N., Ishii T., Satoh S. (2002). A pectin glucuronyltransferase gene is essential for intercellular attachment in the plant meristem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16319–11624 10.1073/pnas.252530499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis M. C. (1984). Structure and properties of pectin gels in plant cell wall. Plant Cell Environ. 7, 153–164 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1984.tb01662.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J. K., Sørensen S. O., Harholt J., Geshi N., Sakuragi Y., Møller I., Zandleven J., Bernal A. J., Jensen N. B., Sørensen C., Pauly M., Beldman G., Willats W. G., Scheller H. V. (2008). Identification of a xylogalacturonan xylosyltransferase involved in pectin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20, 1289–1302 10.1105/tpc.107.050906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Seymour G. B., Knox J. P. (1997). Localization of pectic galactan in tomato cell walls using a monoclonal antibody specific to (1-4)-β-D-galactan. Plant Physiol. 113, 1405–1412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegstra K., Raikhel N. V. (2001). Plant glycosyltransferases. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4, 219–224 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00164-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M., Matoh T., Azuma J. (1996). Two chains of rhamnogalacturonan-II are cross-linked by borate-diol ester bonds in higher plant cell walls. Plant Physiol. 110, 1017–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y., Zhou G., Yin Y., Xu Y., Pattathil S., Hahn M. G. (2011). Molecular analysis of a family of Arabidopsis genes related to galacturonosyltransferases. Plant Physiol. 155, 1791–1805 10.1104/pp.110.163220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi T., Takeda T., Miyazaki Y., Ohnishi-Kameyama M., Hayashi T., O’Neill MA., Ishii T. (2007). A plant mutase that interconverts UDP-arabinofuranose and UDP-arabinopyranose. Glycobiology 17, 345–354 10.1093/glycob/cwl081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupková E., Immerzeel P., Pauly M., Schmülling T. (2007). The TUMOROUS SHOOT DEVELOPMENT2 gene of Arabidopsis encoding a putative methyltransferase is required for cell adhesion and co-ordinated plant development. Plant J. 50, 735–750 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerouxel O., Cavalier D. M., Liepman A. H., Keegstra K. (2006). Biosynthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides – a complex process. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 9, 621–630 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. L., Liu L., Niu Q. K., Xia C., Yang K. Z., Li R., Chen L. Q., Zhang X. Q., Zhou Y., Ye D. (2011). Male gametophyte defective 4 encodes a rhamnogalacturonan II xylosyltransferase and is important for growth of pollen tubes and roots in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 65, 647–660 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04452.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]