Abstract

A new designer surfactant is described containing a covalently bound organocatalyst, proline. This species is water-soluble and, via spontaneous nanomicelle formation, catalyzes aldol reactions on water-soluble or -insoluble substrates in water as the only medium. Recycling the catalyst is trivial, as the amphiphile/catalyst remains in the aqueous phase in the flask.

Although organocatalysis dates back to 1971,1 it is only over the past decade during which remarkable progress has been made.2,3 An impressive number of reaction types can now be effected using this transition metal-free approach, and applications abound. Reviews on this subject in 2010 alone are plentiful.4 Included among the new directions in organocatalysis being pursued are tandem or “organocascade” reactions that combine multiple reaction partners leading to significant increases in molecular complexity in a one pot sequence.5 Notwithstanding these advances, the vast majority of reactions that utilize organocatalysis rely on relatively few catalyst turnovers; typically, ≥10% catalyst is needed to achieve reasonable reaction rates and ultimately, isolated yields. Under such circumstances the implications are clear: a considerable amount of organic material is lost upon workup. While economics may not enter into consideration, e.g., using an inexpensive commercially available catalyst such as proline, many second-generation catalysts require several steps to prepare.4a,6 Moreover, the waste component due to catalyst loss upon workup is necessarily large, detracting from even those processes amenable to use in water as solvent.7 Those run in organic media where most substrates of interest find solubility are even less environmentally friendly. Not surprisingly, therefore, recent efforts that address catalyst recycling have come to light.8 Those reported to date follow a similar pattern; i.e., attachment to a solid support, thereby requiring catalyst separation from a reaction mixture and, oftentimes, reactivation. Ideally, no such manipulation would be needed; i.e., in-flask processing should prevail, where the catalyst remains in the reaction vessel.9 Use of water in place of organic solvent(s) would add a considerable element of “greenness” as well. In this communication we describe a newly designed organocatalyst-containing system that provides a solution to all of these issues: organocatalysis involving water-soluble or insoluble substrates, done in water at room temperature, with in-flask catalyst recycling.

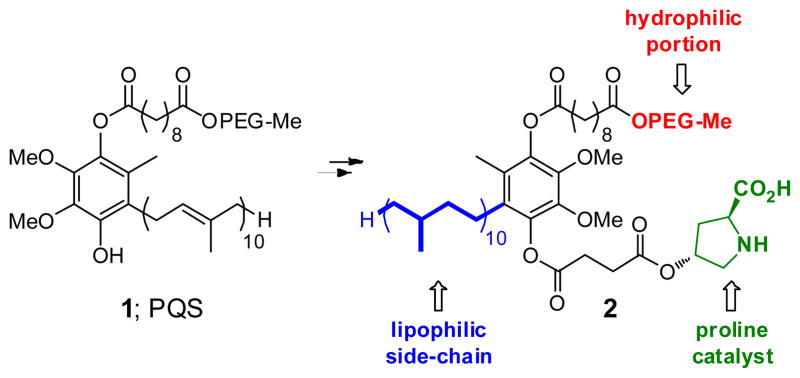

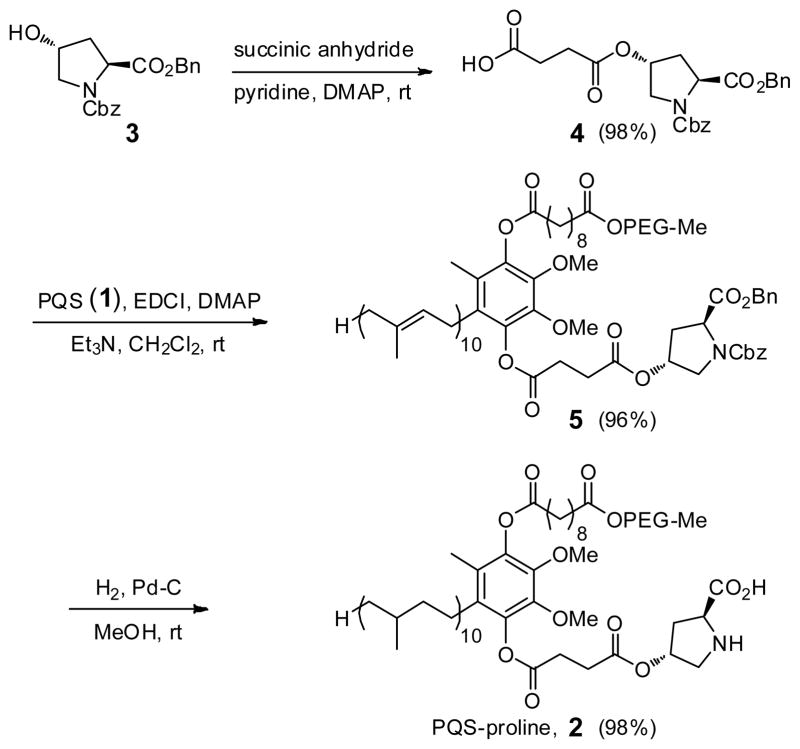

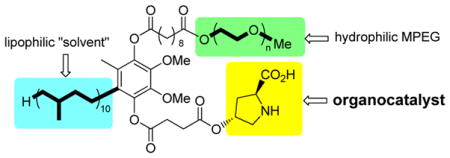

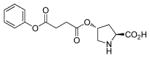

As a “proof-of principle” case, 4-hydroxyproline was selected to represent the potential of the new technology developed. Covalent attachment to the water-soluble micelle-forming species “PQS” (1)10 via its OH group was anticipated to arrive at species 2 (Figure 1). The synthesis of 2 follows the outline shown in Scheme 1. Protected proline derivative 311 was used to open succinic anhydride to arrive at acid 4 in close to quantitative yield. Esterification of coenzyme Q10-derived PQS (1) led to ester 5 (96%), which underwent global hydrogenation to remove (1) the benzyl ester, (2) the Cbz residue, and (3) all ten olefins present in the 50-carbon side-chain found in the reduced form of CoQ10, ubiquinol. Compound 2 thus serves in multiple capacities: (a) as the source of the organocatalyst, in this case, proline; (b) provides the reaction solvent in the form of the 50 carbon hydrocarbon chain; (c) forms a water-soluble nanoparticle that, due to the PEG-2000 component, remains in water upon in-flask extraction of the product. Dissolution of PQS-proline (2) in pure water results in formation of 79 nm micelles, as determined by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS),12 within which homogeneous organocatalysis can occur.

Figure 1.

PQS attached proline catalyst for reactions in water.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of PQS-proline (2)

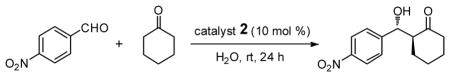

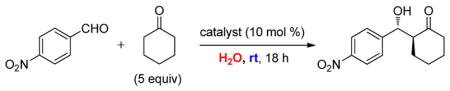

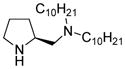

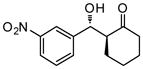

For comparison purposes, the aldol reaction between cyclohexanone and p-nitrobenzaldehyde was chosen for initial study (Table 1). This particular pair of reactants is described in the literature with considerable frequency for related studies in organocatalysis.13 The closest analogy to PQS-proline 2 is Barbas’ micelle-forming proline derivative 6C,7b which shows considerable promise for use in industrial settings.7c Catalysts screened for this aldol reaction included not only PQS-proline, but also the analogous mixed diester derivative 6A14 of 4-hydroxyproline, designed to test the importance of the micelle-forming CoQ10 platform, and proline itself. As illustrated in Table 1, only PQS-proline (2) afforded aldol product to any significant extent, the reaction being run in water at room temperature. With less ketone present (2.5 equiv), the extent of conversion was lower and the yield, therefore, dropped to 80%.

Table 1.

Comparisons between Organocatalysts in an Aldol Reaction, in Water at rt

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| catalyst | yielda (%) | anti:synb | eec (%) |

| PQS-proline (2) | 93 | 92:8 | 96 |

| proline C-4 ester (6A) | <5 | – | – |

| proline (6B) | 0 | – | – |

proline C-4 ester (6A) |

proline (6B) |

Barbas’ catalyst 7b (6C) |

|

Combined yield of isolated diastereomers.

Determined by 1H NMR of the crude product.

Determined by chiral-phase HPLC analysis for anti-product.

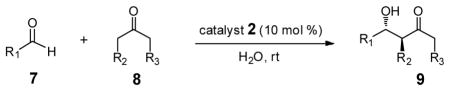

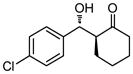

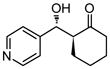

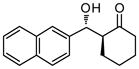

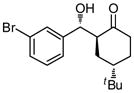

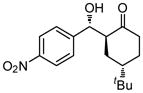

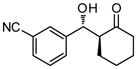

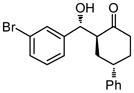

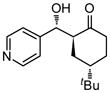

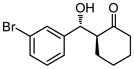

Several additional examples of aldol reactions occurring within, and mediated by, PQS-proline can be found in Table 2. Catalyst loading (10 mol %) was chosen as a compromise between maximizing the amount of 2 used (since none is lost), and the overall viscosity of the aqueous medium (typically hosting large excesses of ketone). While proline works well insofar as ee’s are concerned in several cases, the goal in this study was not to maximize levels of stereoinduction. Rather, both the dr’s and ee’s resulting from various ketone/aldehyde combinations are all as expected based on proline as catalyst.15 In several cases, far better ee’s can be realized using known alternative catalysts that could replace proline bonded to the PQS backbone.16 Another feature worthy of note, given that catalysis is presumably taking place within the lipophilic core of 2 (and not in water), is that water-insoluble educts, in fact, are the preferred substrates. Thus, substituted cyclohexanones (entries 4, 5, 7, and 8) readily participate at ambient temperatures.

Table 2.

Representative PQS-proline (2)-Catalyzed Reactionsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | product | time (h) | yieldb (%) | ant i:sync | eed (%) |

| 1 |

9a |

30 | 88 | 82:18 | 90 |

| 2 |

9b |

18 | 90 | 90:10 | 90 |

| 3 |

9c |

48 | 74 | 86:14 | 92 |

| 4 |

9d |

36 | 80 | 83:17 | 91 |

| 5 |

9e |

18 | 85 | 85:15 | 79 |

| 6 |

9f |

30 | 80 | 90:10 | 97 |

| 7 |

9g |

36 | 82 | 68:32 | 86 |

| 8 |

9h |

18 | 85 | 89:11 | 75 |

| 9 |

9i |

36 | 82 | 84:16 | 86 |

| 10 |

9j |

24 | 90 | 90:10 | 91 |

The reactions were performed with aldehyde (0.1 mmol), ketone (0.5 mmol) and catalyst 2 (0.01 mmol) at rt.

Combined yield of isolated diastereomers.

Determined by 1H NMR of the crude product.

Determined by chiral-phase HPLC analysis for anti-product.

Key to the value of 2 as a model for organocatalytic processes is its inherent potential for in-flask recycling.10 Thus, upon completion of the aldol event, introduction of a single organic solvent (e.g., EtOAc) allows in-flask extraction of the product. Removal of the EtOAc layer is followed by product purification and potential solvent recovery, while the residual aqueous layer in the reaction flask retains the proline-containing nanomicelles composed of amphiphile 2. Re-introduction of starting materials begins the first recycle. Table 3 documents, through three recycles, that the yield, diastereomeric ratio, and ee of the process are essentially invariant.

Table 3.

In-flask Recycling of Catalyst 2

Combined yield of isolated diastereomers.

Determined by 1H NMR of the crude product.

Determined by chiral-phase HPLC analysis for anti-product.

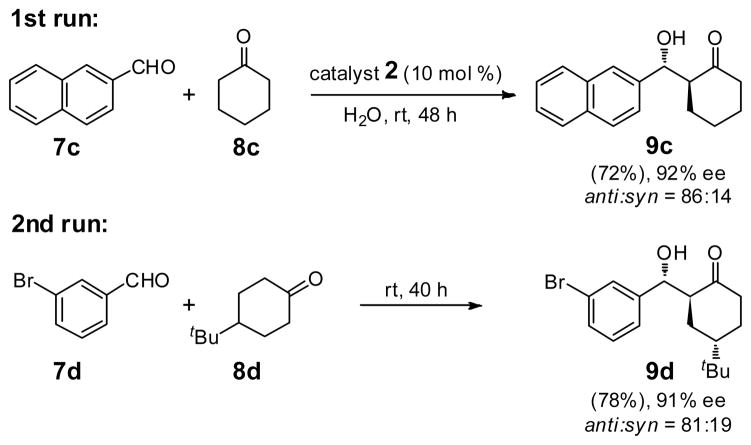

The option to add educts differing in constitution at any point exists as well. For example, as illustrated in Scheme 2, following an initial PQS-proline-catalyzed aldol reaction between aldehyde 7c and ketone 8c giving product 9c, addition of aldehyde 7d and ketone 8d to the same pot containing 2 now leads to aldol 9d.

Scheme 2.

In-flask Recycling of Catalyst 2 in Different Asymmetric Aldol Reactions

In summary, a new surfactant has been designed with the principles of green chemistry in mind to address the high levels of catalyst loading typically associated with organocatalysis. Proline, as a model catalyst, has been attached to a nanomicelle-forming amphiphile derived from the dietary supplement CoQ10. In water this species self-aggregates into nanoreactors in which catalysis takes place at room temperature. Given the covalent linkage of the catalyst (that can be varied) and the high solubility in water of the amphiphile to which it is attached, typical extractive workup is avoided, and in-flask recycling of the catalyst is easily performed.17

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support provided by the NIH (GM 86485) is warmly acknowledged with thanks.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and spectral data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. 2102623. DE. 1971; (b) Eder U, Sauer G, Wiechert R. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1971;10:496–497. [Google Scholar]; (c) Deer U, Sauer G, Wiechert R. 2014757. DE. 1971; (d) Hajos ZG, Parrish DR. J Org Chem. 1974;39:1615–1621. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Special issues dealing with asymmetric organocatalysis: Houk KN, List B, editors. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:487–621. doi: 10.1021/ar0300571.Kocovsky P, Malkov AV, editors. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:255–502.List B, editor. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5413–5883. doi: 10.1021/cr0684016.

- 3.Reviews: Moisan L, Dalko PI. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:3840–3864. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3726::aid-anie3726>3.0.co;2-d.Jarvo ER, Miller SJ. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:2481–2495.List B. Chem Commun. 2006:819–824. doi: 10.1039/b514296m.Doyel AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5713–5743. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r.Mukherjee S, Yang JW, Hoffmann S, List B. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5471–5569. doi: 10.1021/cr0684016.Barbas CF. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:42–47. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702210.Dondoni A, Massi A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:4638–4660. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704684.Bella M, Gasperi T. Synthesis. 2009:1583–1614.

- 4.(a) Trost BM, Brindle CS. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1600–1632. doi: 10.1039/b923537j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Núnez MG, Garcia P, Moro RF, Diez D. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:2089–2109. [Google Scholar]; (c) Johnston JN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2330. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Tietze LF, Brasche G, Gerke K. Domino Reactions in Organic Chemistry. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]; (b) Brandau S, Maerten E, Jorgensen KA. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14986–14991. doi: 10.1021/ja065507+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hong B-C, Wu M-F, Tseng H-C, Liao J-H. Org Lett. 2006;8:2217–2220. doi: 10.1021/ol060486+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Enders D, Huettl MRM, Grondal C, Raabe G. Nature. 2006;441:861–863. doi: 10.1038/nature04820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Carlone A, Cabreea S, Marigo M, Jorgensen KA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hayashi Y, Okano T, Aratake S, Hazelard D. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:4922–4925. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Enders D, Hüttl MRM, Runsink J, Raabe G, Wendt B. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:467–469. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Huang Y, Walji AM, Larsen CH, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15051–15053. doi: 10.1021/ja055545d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zlotin SG, Kucherenko AS, Beletskaya IP. Russian Chem Rev. 2009;78:737–784. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sakthivel K, Notz W, Bui T, Barbas CF. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5260–5267. doi: 10.1021/ja010037z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tang Z, Yang ZH, Chen XH, Cun LF, Mi AQ, Jiang YZ, Gong LZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9285–9289. doi: 10.1021/ja0510156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Samanta S, Liu JY, Dodda R, Zhao CG. Org Lett. 2005;7:5321–5323. doi: 10.1021/ol052277f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guillena G, Hita MC, Nájera C. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:1493–1497. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gandhi S, Singh VK. J Org Chem. 2008;73:9411–9416. doi: 10.1021/jo8019863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Hayashi Y, Sumiya T, Takahashi J, Gotoh H, Urushima T, Shoji M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:958–961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj M, Singh VK. Chem Commun. 2009:6687–6703. doi: 10.1039/b910861k.Mase N, Nakai Y, Ohara N, Yoda H, Takabe K, Tanaka F, Barbas CF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:734–735. doi: 10.1021/ja0573312.In this work, the authors state “Furthermore, crude aldol products were easily isolated by removal of water using centrifugal separation”, sugesting that the catalyst remains in the aqueous phase and may be recyclable, although catalyst reuse is not described Mase N, Watanabe K, Yoda H, Takabe K, Tanaka F, Barbas CF. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4966–4967. doi: 10.1021/ja060338e.For a review, see Mase N, Barbas CF. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:4043–4050. doi: 10.1039/c004970k.Mase N, Noshiro N, Mokuya A, Takabe K. Adv Syn Catal. 2009;351:2791–2796.Hayashi Y, Aratake S, Okano T, Takahashi J, Sumiya T, Shoji M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:5527–5529. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601156.Lei M, Shi L, Li G, Chen S, Fang W, Ge Z, Cheng T, Li R. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:7892–7898.Brogan AP, Dickerson TJ, Janda KD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:8100–8102. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601392.Hayashi Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:8103–8104. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603378.Huang J, Zhang X, Armstrong DW. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:9073–9077. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703606.

- 8.Font D, Sayalero S, Bastero A, Jimeno C, Pericàs MA. Org Lett. 2008;10:337–340. doi: 10.1021/ol702901z.Yan J, Wang L. Synthesis. 2008:2065–2072.Wu Y, Zhang Y, Yu M, Zhao G, Wang S. Org Lett. 2006;8:4417–4420. doi: 10.1021/ol061418q.Gruttadauria M, Giacalone F, Noto R. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1666–1688. doi: 10.1039/b800704g.and references therein.

- 9.Sheldon RA, Arends IWCE, Hanefeld U. Green Chemistry and Catalysis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Lipshutz BH, Ghorai S. Org Lett. 2009;11:705–708. doi: 10.1021/ol8027829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lipshutz BH, Ghorai S. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:1057–1063. [Google Scholar]; (c) Moser R, Ghorai S, Lipshutz BH. unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrett AGM, Pilipauskas D. J Org Chem. 1991;56:2787–2800. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borkovec M. Handbook of Applied Surface and Colloid Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2002. Measuring particle size by light scattering; pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Hernández JG, Juaristi E. J Org Chem. 2011;76:1464–1467. doi: 10.1021/jo1022469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pedrosa R, Andrés JM, Manzano R, Román D, Téllez S. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:935–940. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00688b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ricci A, Bernardi L, Gioia C, Vierucci S, Robitzer M, Quignard F. Chem Commun. 2010:6288–6290. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01502d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.See Supporting Information for preparation.

- 15.Font D, Jimeno C, Pericàs MA. Org Lett. 2006;8:4653–4655. doi: 10.1021/ol061964j.Kristensen TE, Vestli K, Fredriksen KA, Hansen FK, Hansen T. Org Lett. 2009;11:2968–2971. doi: 10.1021/ol901134v.Lombardo M, Easwar S, Marco AD, Pasi F, Trombini C. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:4224–4229. doi: 10.1039/b812607k.See also references 7b and 8a.

- 16.(a) Hayashi Y, Itoh T, Aratake S, Ishikawa H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:2082–2084. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hayashi Y, Samanta S, Itoh T, Ishikawa H. Org Lett. 2008;10:5581–5583. doi: 10.1021/ol802438u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Marigo M, Wabnitz TC, Fielenbach D, Jorgensen KA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:794–797. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zheng Z, Perkins BL, Ni B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:50–51. doi: 10.1021/ja9093583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Representative procedure (Table 2, entry 6). 3-Cyanobenzaldehyde 7f (13 mg, 0.10 mmol), cyclohexanone (52 μL, 0.50 mmol) and catalyst 2 (33 mg, 0.01 mmol) were sequentially added into a Teflon-coated stir bar-containing glass vial at rt. Water (0.25 mL) was added and the resulting solution was allowed to stir at rt for 30 h. The homogeneous reaction mixture was then diluted with EtOAc (1 mL), filtered through a bed of silica gel layered over Celite, and the bed further washed (3 × 4 mL) with EtOAc to collect all of the aldol product material. The volatiles were removed in vacuo to afford the crude product which was subsequently purified by flash chromatography on silica gel (eluting with 20% EtOAc/hexanes) to afford the product as a white solid (18 mg, 80%). Enantiomeric excess: 97%, determined by HPLC (Daicel Chiralpak AD, iPrOH/hexane = 10:90), λ = 273 nm, flow rate 0.5 mL/min, tRmajor = 46.92 min, tRminor = 60.28 min; anti isomer (2S,1′R)-9f: [α]20D = +28.0 (c = 0.30, CHCl3); mp 69–72 °C; IR (thin film): 3498, 2941, 2864, 2229, 1704, 1483, 1449, 1434, 1311, 1229, 1130, 1042, 805 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.64 (t, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (dt, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.57 (dt, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 2.61-2.54 (m, 1H), 2.53-2.48 (m, 1H), 2.41-2.33 (m, 1H), 2.15-2.09 (m, 1H), 1.85-1.80 (m, 1H), 1.67 (qt, J = 12.8, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.59-1.51 (m, 2H), 1.35 (qd, J = 12.8, 4.0 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 215.1, 142.8, 131.7, 130.9, 129.4, 118.9, 112.7, 74.2, 57.3, 42.8, 30.9, 27.8, 24.9; MS (ESI): m/z 252 (M + Na); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C14H15NO2Na [M + Na]+ = 252.1000, found 252.0993.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.