Abstract

Objective

Although research has established childhood sexual abuse (CSA) as a risk factor for men’s perpetration of sexual aggression, there has been little investigation of the factors undergirding this association. This study represents one of the first to use a laboratory-based sexual aggression analogue coupled with an alcohol administration protocol to investigate the pathways through which CSA and alcohol influence men’s self-reported sexual aggression intentions.

Method

After completing background questionnaires, male social drinkers (N = 220) were randomly assigned to a control, placebo, low alcohol dose or high alcohol dose condition. Following beverage consumption, participants read a sexual scenario in which the female partner refused to have unprotected sexual intercourse, after which they completed dependent measures.

Results

Path analysis indicated that men with a CSA history and intoxicated men perceived the female character as more sexually aroused and reported stronger sexual entitlement cognitions, both of which were in turn associated with greater condom use resistance and higher sexual aggression intentions. Exploratory analyses revealed that intoxication moderated the effects of CSA history on sexual entitlement cognitions, such that sexual entitlement cognitions were highest for men who had a CSA history and consumed alcohol.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that CSA history may facilitate sexual assault perpetration through its effects on in-the-moment cognitions, and that these effects may be exacerbated by alcohol intoxication.

Keywords: Childhood Sexual Abuse, Alcohol, Sexual Aggression, Cognitive Distortions, Condom Use Resistance

Despite prevention efforts, sexual assault remains a significant public health problem in the United States. Although men do experience sexual assault, women comprise at least three-fourths of sexual assault victims, and the overwhelming majority of sexual assault perpetrators are men (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006). Although rates vary, studies indicate that up to 64% of non-incarcerated men report perpetration of some form of sexual assault (Abbey, Parkhill, BeShears, Clinton-Sherrod, & Zawacki, 2006) and that most sexual assaults do not involve condom use (Davis, Schraufnagel, George, & Norris, 2008). These high perpetration rates underscore the critical need for empirical investigations of the factors that may increase men’s likelihood of perpetrating sexual aggression, particularly within the context of condom non-use. The purpose of the present study is to provide one of the first experimental investigations of two previously-identified risk factors for men’s sexual assault perpetration - childhood sexual abuse (CSA; Casey, Beadnell, & Lindhorst, 2009; White & Smith, 2004; Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti, 2003) and acute alcohol intoxication (Testa, 2002; Abbey & McAuslan, 2004) – and their direct and indirect effects on men’s condom use resistance and sexual aggression intentions.

Childhood Sexual Abuse and Sexual Assault Perpetration

Research with both undergraduate and community samples of young men suggest that there is a relationship between having a history of CSA and later perpetration of sexual assault against women. For example, Casey and colleagues (2009) found that in a nationally representative sample of male adolescents, a history of CSA was directly associated with the use of sexual coercion in early adulthood. In a study of patients attending a large HMO, men were three times more likely to report committing sexual assault if they had a history of CSA (Whitfield et al., 2003). Further, a study of male undergraduates found that men were six times more likely to report perpetrating a sexual assault if they had been a victim of CSA (Loh & Gidycz, 2006). In a longitudinal study of undergraduate men, White and Smith (2004) found that CSA predicted sexual aggression in high school, which in turn predicted the perpetration of sexual aggression during college.

In addition to these global associations, some investigators have endeavored to investigate the underlying mechanisms that may mediate the CSA-sexual assault relationship among men. In testing their Confluence Model of sexual assault perpetration risk factors, Malamuth and colleagues found that CSA (often in tandem with physical abuse) may precipitate a developmental trajectory comprised of delinquent behaviors and violence-supportive attitudes, followed by impersonal sexual behavior and hostile masculinity, which in turn predict an increased likelihood of sexual assault perpetration against women (Malamuth, Sockloskie, Koss, & Tanaka, 1991). These findings have been fully supported in some studies (Abbey et al., 2006), while other studies have only provided partial support for this model (Casey et al., 2009).

Childhood Sexual Abuse, Alcohol, & Sexual Assault

Male CSA history has been linked to earlier and increased alcohol and drug use in adolescence and adulthood (DiIorio, Hartwell, & Hansen, 2002; Schraufnagel, Davis, George, & Norris, 2010; Senn, Carey, Vanable, Coury-Doniger, & Urban, 2006). Coping with psychological difficulties stemming from the abuse is an intuitive and oft-cited explanation for the CSA-substance use link, although substantiation of this hypothesis is warranted. Senn et al. documented an association for men between CSA and using alcohol prior to sex, a phenomenon that has also been linked to sexual assault perpetration, in that event-level survey research has consistently found that a majority of acquaintance sexual assault incidents involves alcohol use by male perpetrators (Testa, 2002). Because independent lines of research have identified substance use as both an outcome of CSA and a precursor to sexual assault, substance use may mediate the relationship between CSA and the perpetration of sexual aggression.

In support of this line of reasoning, Abbey and colleagues (2006) found that having a history of CSA increased men’s likelihood of reporting alcohol problems, which in turn increased their self-reported number of sexual assaults. However, this mediating influence of general alcohol problems was tested, but not replicated, by Casey and colleagues (2009). Casey et al. noted that their measure of lifetime alcohol problems may have been too distant to detect alcohol’s effects on specific sexual events and suggested that future research assess alcohol’s influence on sexual assault perpetration more proximally.

Alcohol administration experiments provide an excellent method for examining alcohol’s proximal and causal effects on a variety of behaviors. Laboratory studies have consistently found that intoxicated men report greater sexually aggressive intentions toward a hypothetical female partner than do sober men (Davis, Norris, George, Martell, & Heiman, 2006; Norris, Davis, George, Martell, & Heiman, 2002). To increase the precision of our understanding of these effects, much of the experimental research in this domain has attempted to parse the relative contribution of alcohol’s pharmacological and psychological effects on men’s sexual assault intentions.

Pharmacological models attribute alcohol’s effects on behavior to alcohol-induced cognitive deficits. Due to intoxication-produced cognitive impairment, the attention of an intoxicated person is limited to the most salient and easily processed situational stimuli, which are often the cues that instigate behavior (Steele & Josephs, 1990). Thus, an intoxicated man’s cognitive deficit yields focused attention on instigatory cues, such as sexual arousal, while impairing his perception of inhibitory cues, such as sexual refusal, thereby increasing his likelihood of aggressive sexual behavior (Testa, 2002). Moreover, these effects are expected to increase as alcohol dosage increases (Steele & Josephs). Alcohol administration studies support these predictions (e.g. Gross, Bennett, Sloan, Marx, & Juergens, 2001; Norris et al., 2002).

Beyond its pharmacological effects, alcohol influences behavior through expectations about its effects (MacAndrew & Edgerton, 1969). According to Alcohol Expectancy Theory, individuals who believe that alcohol will have particular effects on their behavior are likely to act in accordance with those beliefs when intoxicated. Thus, alcohol consumption may increase some men’s sexually aggressive behavior due to their own beliefs that alcohol facilitates sexual aggression (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2004). Experimental studies have investigated this type of alcohol effect through the use of a placebo condition in which participants are led to believe that they have consumed alcohol when in fact they have not. Empirical support for Alcohol Expectancy Theory as related to sexual assault perpetration is mixed. While some studies have found placebo effects on measures related to sexual aggression, the effects are usually not as large as those for actual alcohol consumption (Marx, Gross & Adams, 1999). Moreover, other studies have not found placebo effects on sexual aggression intentions (e.g. Johnson, Noel, & Sutter Hernandez, 2000; Norris et al., 2002).

Cognitive Mediators

Traumatic sexualization, one of the four proposed dimensions of the Traumagenic Dynamics Model, is a hypothesized process through which CSA may result in maladaptive sexual behavior and increased perceptual and cognitive distortions regarding sexual issues (Finkelhor & Browne, 1985). These distortions may include heightened awareness of issues related to sexuality and confusion regarding adaptive sexual behavior. Ward (2002) notes that some cognitive distortions may develop as a way for CSA survivors to understand their experiences of abuse and their abusers’ behavior. Cognitive distortions such as these may later contribute to inaccurate perceptions or interpretations of sexual behavior which may ultimately set the stage for disagreement or conflict between the parties involved in the sexual encounter. Indeed, a great deal of research has established that sexual assault perpetration is undergirded by the perpetrator’s cognitions (Ward, 2000), suggesting that these cognitive distortions may function as a mediator of the CSA-sexual aggression relationship.

Research suggests that sexual offenders engage in a variety of cognitive distortions in their perception of information. For example, perpetrators are more likely than non-perpetrators to misperceive a woman’s sexual intent as greater than it actually is (Abbey et al., 2004; Shea, 1993; Ward, 2000). Such misperceptions of a woman’s level of sexual interest or arousal may be exacerbated when under the influence of alcohol. One experimental study found that men who read a rape scenario while intoxicated rated the woman as being more sexually aroused than did sober men; moreover, these misperceptions resulted in increased sexual aggression intentions by participants (Norris et al., 2002). Similarly, intoxicated men perceived an unwilling woman as more sexually aroused than did sober men, which delayed the decision that a male character should stop his unwanted sexual advances (Gross et al., 2001). Finally, Abbey and colleagues (2009) found that when intoxicated, men with stronger tendencies to misperceive women’s sexual intentions reported feeling more justified in using coercive techniques to obtain unprotected sex than did sober men. Alcohol intoxication may thus compound these cognitive distortions, thereby increasing men’s likelihood of perpetrating sexual assault.

Sexual assault perpetrators also endorse cognitive distortions that may predispose them to perpetrating sexual aggression (Polasheck & Ward, 2002). One example of these offense-related thought patterns among rapists is a belief in sexual entitlement, i.e., men’s sexual needs should be met on demand (Hill & Fischer, 2001; Polasheck & Ward). Research indicates that beliefs of sexual entitlement may be used by rapists as well as child sexual offenders to justify their assaults (Pemberton & Wakeling, 2009). Alcohol intoxication may potentiate the effects of these cognitive distortions by focusing men’s attention toward these salient, instigatory thoughts (Abbey et al., 2004).

Sexual Assault in Relation to Condom Use

In addition to the inherent negative ramifications of being a victim of sexual assault, women who are sexually assaulted by men are also at increased risk for sexually-transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancy. Research indicates that sexually aggressive acts involving penetration often do not include condom use (Davis et al., 2008; Peterson, Janssen, & Heiman, 2010). For example, Davis and colleagues found that approximately 40% of sexual assault perpetrators reported that they never used condoms during their assaults, while another 30% reported using condoms inconsistently. Because of these associations between sexual violence and unprotected sexual behavior, investigators have initiated research to examine men’s use of coercive and forceful tactics to obtain unprotected sex from a female sex partner who wants to use a condom (Abbey et al., 2009; Davis, 2010; Davis & Logan-Greene, in press). One survey of young men revealed that over one-third of participants reported having used coercive or aggressive tactics to avoid using a condom since the age of 14 (Davis & Logan-Greene), while an experimental investigation found that intoxicated men were indirectly more likely to report greater intentions to engage in sexual aggression to obtain unprotected sexual intercourse (Davis). Considering the higher rates of inconsistent condom use reported by men with a CSA history (DiIorio, et al., 2002; Senn et al., 2006), the present study aims to expand our current understanding of the interplay between alcohol and condom use avoidance by exploring the influence of CSA history on intentions to engage in unprotected sexual aggression.

Study Overview and Hypotheses

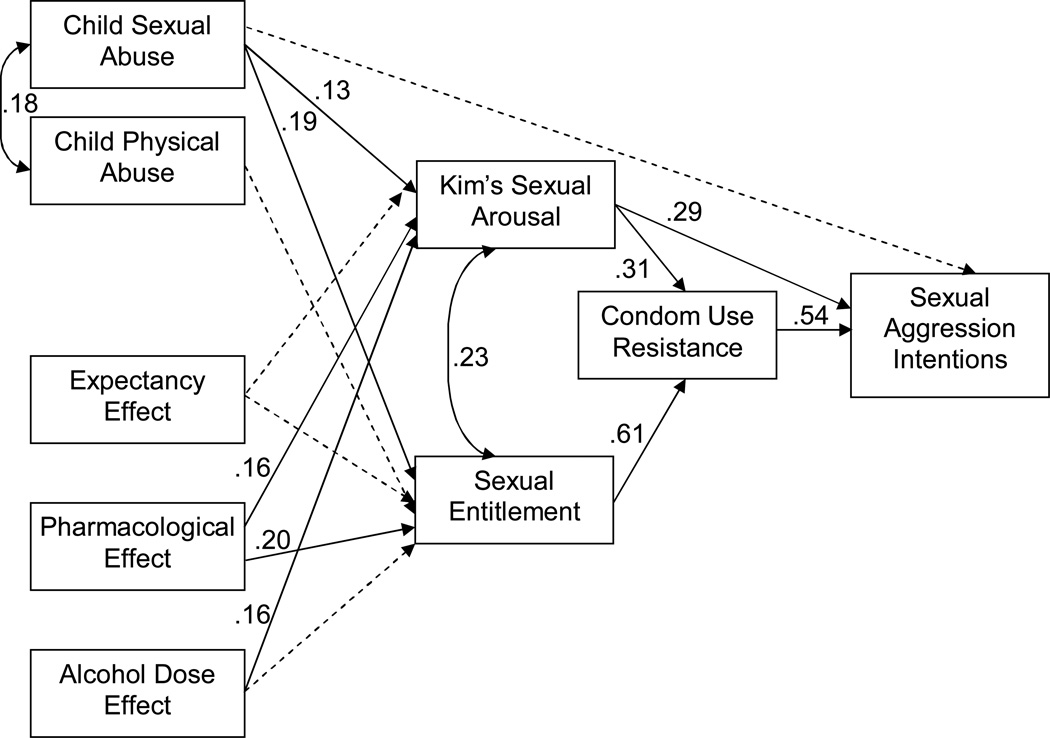

The present study used alcohol administration experimental methods to examine the effects of CSA history and alcohol intoxication on men’s perceptions of and intentions regarding a hypothetical sexual scenario in which their female sex partner refuses to engage in sexual intercourse without a condom. We included childhood physical abuse (CPA) in the analyses due to the high correlation between CSA and CPA, as well as the previously established indirect association between CPA and sexual assault perpetration (Casey et al., 2009). Dependent measures assessed perceptions of the female character’s sexual arousal, cognitive distortions regarding sexual entitlement, condom use resistance tactics, and intentions to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse with an unwilling partner. Employing a path analysis framework, the hypothesized model (see Figure 1) proposes that men with a history of CSA will report greater sexual aggression intentions than men without a CSA background (Hypothesis 1). We expect that CSA will also indirectly increase sexual aggression intentions through increased perceptions of the woman’s sexual arousal and increased sexual entitlement cognitions, both of which are expected to predict increased condom use resistance intentions, which are in turn expected to predict greater intentions to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse despite the female character’s resistance to having unprotected sex (Hypothesis 2). Consistent with previous findings, we predicted that the receipt of alcohol (Hypothesis 3) and amount of alcohol dosage (Hypothesis 4), as well as the belief that alcohol has been consumed (Hypothesis 5), will increase perceptions of the female character’s sexual arousal as well as sexual entitlement cognitions, resulting in greater intentions to resist condom use and commit sexual aggression. Finally, although there has been some investigation of the possible mediating role of alcohol in the CSA-sexual assault relationship (e.g. Abbey et al., 2006), the moderating effects of alcohol intoxication in this linkage are unknown. Thus, we examined the interactive effects of alcohol and CSA history on the dependent measures through exploratory analyses.

Figure 1.

Model Linking Childhood Sexual Abuse, Beverage Condition, and Sexual Aggression Intentions

Note. Dotted lines represent hypothesized paths that were not significant in the final model. Solid lines represent paths significant at p < .050 in the final model. Standardized values shown.

Method

Participants

Print (e.g. newspaper and fliers) and online advertisements stating that single male social drinkers were needed for a study on decision-making were used to recruit participants (N = 227). Interested individuals telephoned for eligibility screening. Inclusion requirements consisted of a) being a male between the ages of 21 and 35; b) being interested in a sexual relationship with a woman; c) having had sexual intercourse without a condom at least once in the past year; d) being a moderate social drinker (defined as drinking between 5 and 40 drinks per week on average); and e) having had at least one binge drinking episode in the past six months (defined as having consumed five or more drinks on one occasion). Given the recommended federal guidelines for alcohol administration (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005), participants were required to have at least one recent binge drinking episode so that, if assigned to the high dose condition, their laboratory alcohol consumption would not be greater than their recent self-administered drinking levels. Exclusion criteria consisted of a) being in a committed relationship with a woman; b) scoring five or higher on the Brief Michigan Alcohol Screening Test, which is suggestive of problem drinking (Pokorny, Miller, & Kaplan, 1972); or c) having an alcohol contraindication such as a health condition or medication regimen.

The average age of participants was 25.5 (SD = 3.5). The sample was 69.0% Caucasian, 6.5% Asian American or Pacific Islander, 8.8% African American, 1.9% Native American/Native Alaskan, and 12.1% of participants indicated that they were multiracial or “other”. The sample was 8.8% Hispanic. In all, 35.6% of the participants identified themselves as full- or part-time students, and 70.8% were employed at least part time. On average, participants reported consuming 8.7 (SD = 9.4) standard drinks per week.

Procedures

Pre-experimental procedures

Eligible callers were scheduled for a laboratory visit and informed of the pre-visit requirements. These guidelines consisted of a) not driving to the laboratory; b) not consuming a caloric beverage or food within three hours of their appointment; c) not consuming alcohol or using recreational or over-the-counter drugs within 24 hours of their appointment; and d) bringing a photographic form of identification.

Upon participants’ arrival, a male research assistant (RA) checked compliance with pre-visit requirements. Participants were also given an alcohol breath test to ensure that their pre-study blood alcohol content (BAC) was 0.0%. Participants were escorted to a private office where they were guided through the process of informed consent. The RA then oriented them to the computer and left them alone to complete a series of background questionnaires.

Experimental procedures

Following the background measures, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four beverage conditions. Beverage conditions included: a) a dose of alcohol intended to yield a peak BAC of .10%; b) a dose of alcohol intended to yield a peak BAC of .05%; c) a control condition in which participants were given no alcohol and were informed as such; and d) a placebo condition in which participants were told they would be receiving the .05% dose, but received no alcohol in actuality. Participants assigned to the .05% condition received 0.510ml ethanol per pound of body weight. Participants in the .10% condition received twice that amount per pound of body weight. Alcoholic beverages consisted of one part 100-proof vodka to three parts orange juice. Control participants consumed a volume of orange juice that was equivalent to the total volume of beverage that they would have received in the alcohol condition to which they were yoked (yoking procedures explained below). Procedures for the placebo manipulation followed those recommended by Marlatt and Rohsenow (1980). Beverages for the placebo condition contained flattened tonic water in place of vodka. The cups for the placebo condition were misted with vodka near the rim of the cup and had a squirt of vodka and lime added to the beverage to increase the fidelity of the placebo manipulation. Placebo participants who inquired about their BAC were given false feedback (told their BAC was .025%) to enhance the manipulation. Participants were guided by the RA to pace their beverage consumption evenly over nine minutes.

Because alcohol intoxication limb (either ascending or descending levels of intoxication) has been shown to affect cognitive and behavioral performance differently (e.g. Pihl, Paylan, Gentes-Hawn, & Hoaken, 2003), we ensured that the stimulus story and related assessments were completed on the ascending limb by testing participant BACs every four minutes until they reached a criterion BAC of ≥.03% for participants in the .05% condition and ≥.07% for participants in the .10% condition, at which point they began reading the stimulus story (Schacht, Stoner, George, & Norris, 2010). Just prior to reading the stimulus story, participants had a mean BAC of .050% (SD = .014) in the .05% condition and .077% (SD = .008) in the .10% condition. Their respective mean BACs after the completion of the dependent measures was .051% (SD = .010) and .096% (SD = .014). Mean BAC of the control and placebo participants was .000% (SD = .00) throughout the protocol. A yoked control design was used to reduce error variance in time between beverage consumption and experimental manipulation (Giancola & Zeichner, 1997), such that each participant assigned to either a control or placebo condition was yoked to a prior alcohol participant and was conducted through the experiment at the same time intervals as the alcohol participant to whom he had been yoked. Half of the control participants were yoked to low-dose alcohol participants; half were yoked to high-dose participants. Placebo condition participants were yoked only to alcohol participants in the .05% condition.

Stimulus Story

After reaching the criterion BAC, participants read a sexually explicit scenario of approximately 1600 words and a 5th grade reading level. The story was generated by members of the research team and was pilot tested and modified in the light of pilot participant feedback. The story was written in the second person, and participants were instructed to project themselves into the story as the protagonist at their current level of intoxication. In the story, the protagonist is attending a party where he sees “Kim,” an attractive woman with whom he has previously had sex twice (using a condom both times). They flirt then go to Kim’s house where they progress from kissing to removing their clothes. The protagonist and Kim realize that neither one of them has a condom. They agree that they should not have sex without a condom but agree to continue “fooling around”. The protagonist then suggests that they have sex “just for a little while” to which Kim responds that she does not want to have sex without a condom. They continue to engage in mutually agreed-upon non-penetrative sexual activity. The protagonist then moves on top of Kim and presses his genitals against hers despite her repeated verbal and physical protests. Dependent measures were then assessed. Participants reported finding the scenario to be a realistic situation (I feel that the scenario depicted a realistic situation that might happen to me; 1 = not at all; 5 = very much; M = 4.03; SD = 1.28).

Manipulation checks

Two manipulation checks were used to ensure the placebo manipulation was successful. Near the conclusion of the study, participants were asked how many drinks they had consumed and what their highest level of intoxication was on a scale from 1 (not at all intoxicated) to 7 (extremely intoxicated). If a participant indicated “0” drinks and an intoxication level of “1”, he was considered a manipulation failure.

Detoxification and debriefing

After completing the dependent measures, participants were debriefed, paid $15 per hour, and released. (Participants who received alcohol were not debriefed or released until their BAC dropped to .03% or below.) All study methods were approved by the University Human Subjects Division.

Measures

Childhood Sexual and Physical Abuse

To assess history of childhood sexual and physical abuse, we utilized the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003). The sexual and physical abuse subscales both include five items scored from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). The subscales of the CTQ can be scored dichotomously or continuously and have demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties among across several samples (Bernstein et al.). Of our participants, 18.4% reported a history of CSA and 58.5% reported a history of CPA. Because of the relatively low prevalence of CSA in the sample, we scored both CSA and CPA dichotomously. See Table 1 for all scale means and standard deviations.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations of Study Variables (N = 220)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Sexual Abuse | -- | ||||||||

| 2. Child Physical Abuse | .18** | -- | |||||||

| 3. Expectancy Effect | .12 | −.01 | -- | ||||||

| 4. Pharmacological Effect | .05 | .03 | −.04 | -- | |||||

| 5. Dose Effect | .15* | .13 | −.01 | .01 | -- | ||||

| 6. Kim's Sexual Arousal | .16* | .10 | −.04 | .17* | .19** | -- | |||

| 7. Sexual Entitlement | .20** | .08 | −.01 | .22** | .04 | .30** | -- | ||

| 8. Condom Use Resistance | .20** | .11 | −.04 | .18** | −.03 | .49** | .70** | -- | |

| 9. Sexual Aggression Intentions | .15 | .16* | −.08 | .11 | .01 | .55** | .41** | .68** | -- |

| Mean | .20 | .60 | NA | NA | NA | 2.89 | 1.75 | 2.11 | 3.34 |

| Standard Deviation | .40 | .49 | 1.27 | 1.25 | 1.30 | 1.65 | |||

| Range | 0 – 1 | 0 – 1 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 7 | 1 – 6.63 | 1 – 7 | |||

Note 1.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Note 2. “Expectancy effect” refers to the contrast comparing control and placebo conditions. “Pharmacological effect” refers to the contrast comparing participants who consumed alcohol (low and high doses) with those who did not (controls and placebos). “Dose effect” refers to the contrast comparing the high dose and low dose conditions.

Perceptions of Kim’s Sexual Arousal

Based on items presented in Norris et al. (2002), participants rated their perceptions of Kim’s level of sexual arousal and interest through five items, such as “How sexually aroused is Kim at this point?” using 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = not at all; 7 = extremely). The mean of the five items was computed (α = .72).

Sexual Entitlement Cognitions

Participants rated their sexual entitlement cognitions in the current scenario on 3 items using 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) scales. Participants were asked “How likely are you to think the following at this point in the situation:” and were provided with a list of statements, such as “She owes it to me to have sex with me.” The mean of the three items was computed (α = .84).

Condom Use Resistance Intentions

An 8-item scale assessed the likelihood that participants would engage in various tactics in order to obtain unprotected sexual intercourse using 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) scales. These behaviors ranged in intensity and included relatively mild tactics, such as “try to persuade Kim to have sex with you without a condom” as well as more extreme tactics, such as “Threaten to hurt Kim if she will not have sex with you without a condom”. The mean of the eight items was computed (α = .89).

Sexual Aggression Intentions

A 5-item scale assessed estimates of participants’ intentions to engage in sexual intercourse with Kim without a condom, despite her refusal to engage in unprotected sexual intercourse (Davis, 2010). Participants rated the likelihood of a variety of sexual outcomes such as “Put your penis inside of Kim’s vagina without a condom” and “Have sex with Kim without a condom” using 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) scales. The mean of the five items was computed (α = .86).

Results

Descriptive and Preliminary Analyses

All data were first examined for strings of missing data or repeated responses. Data from 7 participants were deleted due to missing data on nearly all variables (3 cases) or being assigned to the placebo condition but suspecting that they were not drinking alcohol (4 cases). The final sample size for analyses was 220, and final cell sizes were as follows: control condition = 54; placebo condition = 61; low dose condition = 53; high dose condition = 52. Missing data was addressed with the use of maximum likelihood estimators, rather than imputation or substitution. All study variable distributions were examined for normality. CPA and CSA were both dichotomized into whether (coded as 1) or not (coded as 0) abuse was experienced.

Table 1 one provides descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables. Alcohol condition was coded with three contrasts. The expectancy effect tested differences between control and placebo participants and was coded as -1 = control, 1 = placebo. The pharmacological effect tested differences between participants who received alcohol with those who did not, and was coded as -1 = did not consume alcohol, 1 = consumed alcohol. The alcohol dose effect tested differences between participants who consumed a low dose of alcohol with those who received a high dose, and was coded as -1 = low dose, 1 = high dose. CSA was significantly and positively correlated with CPA, an alcohol dose effect, perceptions of Kim’s sexual arousal, sexual entitlement, and condom use resistance. CPA was significantly, albeit modestly, positively associated with sexual aggression intentions. Expectancy set was not related to any of the in-lab variables. Consuming alcohol was associated with higher perceptions of Kim’s sexual arousal, sexual entitlement, and condom use resistance. Participants receiving a high alcohol dose perceived Kim to be more sexually aroused than those who received a low alcohol dose. All story variables (i.e. the dependent variables based on events from the story) were significantly and positively correlated with one another with large correlations.

Model Testing

Path analysis testing the hypothesized relationships presented in Figure 1 was conducted with MPlus 4.21. All hypothesized paths were free to vary. This model did not fit the data well, χ2 (12, N = 220) = 43.741, p < .001, RMSEA = .110, CFI = .919, and there were several nonsignificant pathways.

Model refinement did not involve deleting nonsignificant pathways, because the absence of a detectable path does not negate its potential for suppression and/or enhancement effects, nor does it make the path any less relevant to the initial hypothesis. Instead, refinement focused on adding paths implied by the modification indices. Thus, based on the modification indices, an additional direct path from Kim’s arousal to sexual aggression intentions was added. This model demonstrated good fit, χ2 (11, N = 220) = 16.851, p = .112, RMSEA = .049, CFI = .985 (see Figure 1; all path coefficients are included in the model results and are presented in standardized and unstandardized form in Table 2).

Table 2.

Path Weights (Standardized and Unstandardized) with Standard Errors (N = 220)

| Unstandardized | S.E. | Z-Score | Standardized | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim's Sexual Arousal ON | |||||

| Child Sexual Abuse | 0.42 | 0.21 | 2.02* | 0.13 | |

| Expectancy Effect | −0.16 | 0.23 | −0.72 | −0.05 | |

| Pharmacological Effect | 0.39 | 0.17 | 2.39* | 0.16 | |

| Alcohol Dose Effect | 0.59 | 0.24 | 2.45* | 0.16 | |

| Sexual Entitlement ON | |||||

| Child Physical Abuse | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.03 | |

| Child Sexual Abuse | 0.58 | 0.21 | 2.80** | 0.19 | |

| Expectancy Effect | −0.06 | 0.22 | −0.26 | −0.02 | |

| Pharmacological Effect | 0.51 | 0.16 | 3.15** | 0.20 | |

| Alcohol Dose Effect | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.01 | |

| Condom Use Resistance ON | |||||

| Kim's Sexual Arousal | 0.31 | 0.05 | 6.56*** | 0.31 | |

| Sexual Entitlement | 0.64 | 0.05 | 13.15*** | 0.61 | |

| Sexual Aggress Intentions ON | |||||

| Child Sexual Abuse | 0 | 0.2 | −0.01 | 0 | |

| Kim's Sexual Arousal | 0.37 | 0.07 | 5.35*** | 0.29 | |

| Condom Use Resistance | 0.69 | 0.07 | 10.09*** | 0.54 | |

| Child Physical Abuse WITH | |||||

| Child Sexual Abuse | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.64** | 0.18 | |

| Kim's Sexual Arousal WITH | |||||

| Sexual Entitlement | 0.36 | 0.1 | 3.57*** | 0.23 | |

Note 1.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Note 2. “Expectancy effect” refers to the contrast comparing control and placebo conditions. “Pharmacological effect” refers to the contrast comparing participants who consumed alcohol (low and high doses) with those who did not (controls and placebos). “Alcohol dose effect” refers to the contrast comparing the high dose and low dose conditions.

A direct association between CSA and greater sexual aggression intentions (Hypothesis 1) was not supported. However, consistent with Hypothesis 2, CSA was positively associated with perceptions of Kim’s arousal and with sexual entitlement. Men who were sexually abused in childhood perceived Kim as more sexually aroused and reported stronger sexual entitlement cognitions. As predicted in Hypothesis 3, participants who received an alcoholic beverage also believed that she was more sexually aroused and reported stronger sexual entitlement cognitions. Further, in partial support of Hypothesis 4, men who consumed a high dose of alcohol believed that Kim was more sexually aroused than did men who consumed a low dose of alcohol. There were no effects of CPA or alcohol expectancy set (Hypothesis 5) on the story variables; however, CSA and CPA were positively correlated.

In further support of Hypothesis 2, there were several significant paths linking the story-related dependent measures. Perceptions of Kim’s sexual arousal were positively associated with condom use resistance and sexual aggression intentions. As men believed Kim to be more sexually aroused, they were more likely to endorse condom use resistance strategies and to intend to engage in sexual activities with Kim without a condom despite her protests. Sexual entitlement cognitions were also positively associated with condom use resistance. Perceptions of Kim’s sexual arousal and sexual entitlement cognitions were significantly positively correlated with one another. Finally, condom use resistance was positively associated with sexual aggression intentions. As men’s resistance to using a condom increased, their intentions of having unprotected sex with Kim despite her protests also increased.

Overall, this model accounted for 52.40% of the variance in men’s sexual aggression intentions. Although there were no direct effects of CSA or acute alcohol intoxication on these intentions, these constructs had significant indirect effects through their effects on perceptions of her sexual arousal and sexual entitlement cognitions. Total standardized effects were as follows: CSA = .121 (z = 2.882; p = .004); Pharmacological effect = .137 (z = 3.294; p = .001); Alcohol dose effect = .075 (z = 1.811; p = .070); Kim’s sexual arousal = .165 (z = 5.509; p < .001); and Sexual entitlement = .329 (z = 8.005; p < .001).

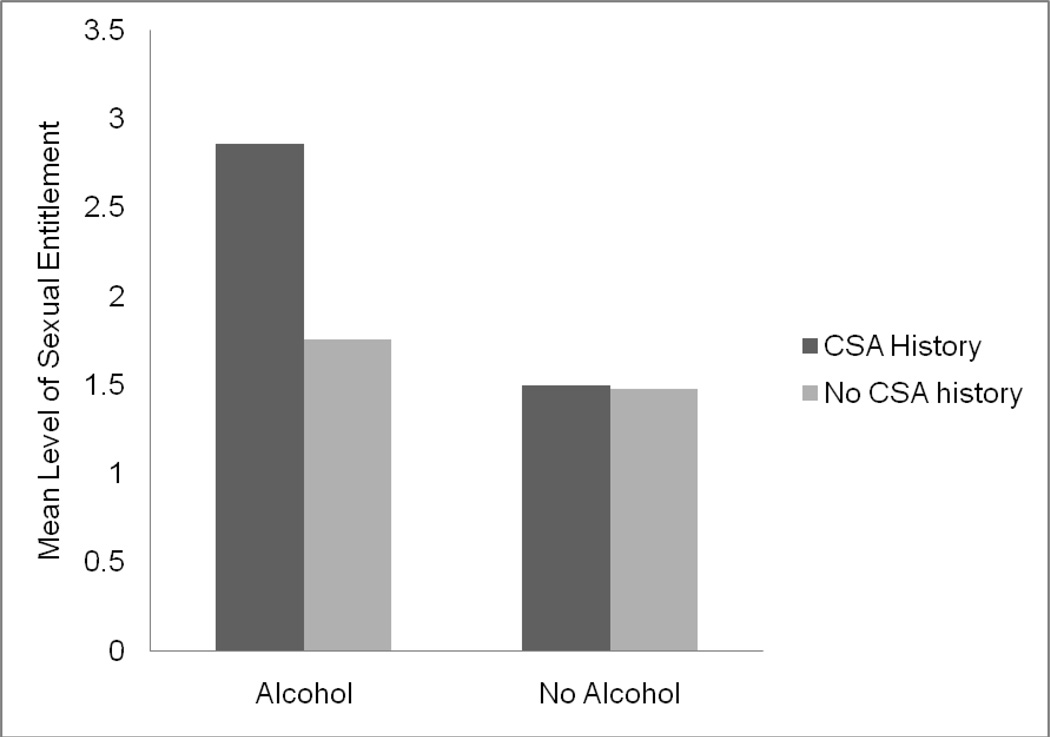

Exploratory Analyses

Because of insufficient power to include interactions in the model, we used analysis of variance to examine potential interactions between CSA and beverage condition on perceptions of Kim’s arousal and sexual entitlement cognitions. In order to have approximately the same number of men who experienced CSA in each cell, and because there were no significant expectancy effects, we dichotomized alcohol consumption by combining control and placebo participants into a ‘non-alcohol’ group (with 21 men who experienced CSA) and combining low and high dose participants into an ‘alcohol’ group (with 23 men who experienced CSA).

There were significant main effects of CSA and alcohol consumption on perceptions of Kim’s sexual arousal, Fabuse (1, 215) = 4.99, p = .027, Falcohol (1, 215) = 7.64, p = .006, and on sexual entitlement, Fabuse (1, 215) = 8.30, p = .004, Falcohol (1, 215) = 15.64, p = .001. The main effects on sexual entitlement were moderated by an interaction F(1, 215) = 5.30, p = .022 (presented in Figure 2). Among men who consumed alcohol, those who were sexually abused in childhood reported stronger sexual entitlement cognitions than did men who had not been sexually abused in childhood, t (215) = 3.71, p < .001. However, among men who did not consume alcohol, CSA history was not associated with men’s sexual entitlement cognitions, t (215) = 0.41, p = .687.

Figure 2.

The Interacting Effects of Childhood Sexual Abuse History and Acute Alcohol Consumption on Sexual Entitlement

Because the means for both condom use resistance and sexual aggression intentions were below the midpoint, we also examined the percentages of the sample who said they were “likely” (i.e. had a mean score of 5 or higher) to engage in these behaviors. Overall, 6.6% of participants reported being likely to resist condom use (2.2% of sober/CSA negative participants; 5.6% of sober/CSA positive participants; 5.0% of intoxicated/CSA negative participants; and 33.3% of intoxicated/CSA positive participants). Additionally, 17.9% of participants reported being likely to engage in sexual aggression (12.9% of sober/CSA negative participants; 11.1% of sober/CSA positive participants; 18.8% of intoxicated/CSA negative participants; and 42.9% of intoxicated/CSA positive participants).

Discussion

Although the “cycle of abuse” is often cited in the research literature, there has been little experimental investigation of the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying this cycle (Thomas & Fremouw, 2009). To our knowledge, this study represents the first to use a laboratory-based sexual aggression analogue coupled with an alcohol administration experimental protocol to examine the direct and indirect effects of CSA background and acute alcohol intoxication on men’s sexual aggression intentions. As such, the present research pioneers the exploration of how a history of CSA may have a sustained influence on mediating cognitive mechanisms relevant to sexual assault perpetration.

Although CSA history was not directly related to sexual aggression intentions as predicted in Hypothesis 1, it was indirectly related to increased sexual aggression intentions through the mediating variables of partner sexual arousal perceptions and sexual entitlement cognitions (Hypothesis 2). As conceptualized by Finkelhor and Browne (1985), the experience of CSA may involve traumatic sexualization, which can result in a variety of cognitive distortions regarding sex. Although there has been little research in this area with male CSA survivors, the present study certainly justifies further investigation. Men with a CSA history perceived a woman who was refusing to have unprotected sex as more sexually aroused and interested than did men without such a history. Perhaps, as proposed by Finkelhor and Brown, having been involved in a non-consensual or abusive childhood sexual experience shifts or pollutes their conception of normative sexual behavior and adaptive sexual thought-processes. While speculative, this maladaptive sexuality may result in the increased misperception of their partner’s sexual interest and arousal that was observed in the present study. Such distortions may ultimately facilitate and normalize sexually aggressive behavior by implying that the victim was not truly resisting sexual activity because she “really wanted it” (Ward, 2000). Future research should compare and contrast the ways in which men with and without a history of CSA attend to and interpret the nuances of women’s sexual behavior when assessing their sexual arousal and interest.

The idea that men are entitled to sex is a common cognitive distortion among sexual assault perpetrators (Polaschek & Ward, 2002). Ward (2000) has speculated that men who were sexually abused may develop these distortions as a way to understand their abuser’s behavior. For example, they may come to believe (or even have been told by their abuser) that the abuse occurred because the victim “owes them” or is “their property” (Pemberton & Wakeling, 2009). Ward notes that while these early beliefs may in some ways be adaptive within the abuse context by enabling survival, they may later prove to be maladaptive in other contexts by generating the cognitive distortions that facilitate sexually aggressive behavior towards others.

While CPA had a significant bivariate relationship with sexual aggression intentions, in the final model CPA was only significantly related to childhood sexual abuse. This lack of relationship with the outcome variable may indicate that mediators that may best account for a relationship between CPA and sexual assault perpetration were not included in the current analyses. Indeed, Casey et al. (2009) found that the relationship between CPA and sexual assault only occurred indirectly through delinquent behavior. Thus, based on this study as well as prior findings like those in Casey et al., it appears that CSA and CPA may both be associated with an increased likelihood of sexual assault perpetration, but that the pathways undergirding these relationships may differ. Delineating the similarities and differences between men’s responses to CSA and CPA and how these responses might influence sexual assault perpetration should be a focus of future research.

In concordance with Hypothesis 3, the receipt of alcohol also increased female sexual arousal misperceptions and cognitions regarding sexual entitlement; the pharmacological effect of alcohol on misperceptions of female sexual arousal was even stronger for those participants who received a high dose of alcohol (Hypothesis 4). However, contrary to Hypothesis 5, alcohol expectancies (as operationalized through a placebo condition) were not a significant predictor in the model. In accordance with pharmacological impairment models, intoxicated men had a greater focus on instigatory sexual cues such as the woman’s arousal and their own sexual entitlement, which resulted in increased sexual aggression intentions. These findings not only replicate previous studies (e.g. Norris et al., 2002), but they also emphasize the greater relevance of the actual cognitive impairment effects of alcohol over the mere belief that one has consumed alcohol in predicting sexual assault likelihood. Moreover, perceptions of the woman’s arousal increased with alcohol dosage, indicating that as men’s cognitive impairment increases, their perceptions of a woman’s sexual interest and arousal – even in the face of clear sexual refusal – also increases. Thus, greater levels of intoxication may precipitate a higher likelihood of sexual aggression through an increased (mis)perception of the woman’s sexual interest and arousal (Abbey et al., 2004).

Our exploratory analyses suggest that acute alcohol intoxication moderates the effects of CSA history on men’s in-the-moment cognitions regarding sexual entitlement. Intoxicated men with a CSA history reported greater endorsement of sexual entitlement cognitions than any other group. Men with a CSA background also reported greater endorsement of this cognition generally; thus, the cognitive impairment effects of alcohol may have redoubled their focus on these salient features and cognitions. Although these analyses were exploratory and require replication, these findings indicate that the ways in which acute alcohol intoxication may exacerbate sexual assault-congruent cognitive distortions, particularly among men who were sexually abused in childhood, is an important area for future research.

Limitations

As with any laboratory experiment, external validity is a potential limitation. Although hypothetical sexual scenarios can never completely capture every important element of a real-world sexual encounter, great care was taken to ensure that the current scenario was realistic for our sample, and participant ratings substantiate the success of this effort. Similarly, although a BAC of .10% represents a high level of intoxication (as well as one of the highest doses researchers may ethically administer to participants), many young male social drinkers reach levels of intoxication greater than this during real-world drinking experiences; thus our findings may not generalize to situations that involve greater amounts of alcohol consumption. Our sample consisted of recent binge drinkers who also used condoms inconsistently. Although this increases the relevance of our findings for interventions targeting high-risk groups, it also diminishes their generalizability to other populations. Additionally, less than 20% of the sample reported a history of CSA, thus precluding examination of the possible differential effects of specific abuse characteristics (e.g. abuse severity, relationship to perpetrator, perpetrator gender) on the dependent measures. Prior to reading the stimulus story and related outcome measures, participants completed background questionnaires, some of which assessed sexual assault perpetration-related attitudes and behaviors. Thus, the potential of demand characteristics cannot be ruled out. Finally, this study represents a novel way of investigating the relationships among CSA, alcohol consumption, and sexual assault perpetration through its use of experimental methods involving alcohol administration and its inclusion of in-the-moment cognitive mediators. As such, future research replicating these findings would bolster their validity.

Clinical and Prevention Implications

As noted by Malamuth and colleagues (1991), experiencing abuse as a child may put one on a trajectory towards violence through the development of distorted schemas regarding sexuality. Although these distortions may help male CSA survivors mask their feelings of shame surrounding sex (Lisak et al., 1996), they may also ultimately increase their propensity towards sexual aggression. This study shows that these distortions occur as part of the in-the-moment sexual decision-making process and increase sexual aggression intentions, suggesting that interventions targeting these cognitive distortions may ultimately reduce sexually aggressive behavior. Early intervention (e.g. Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) with CSA victims may not only prevent the development of these distortions, but can also teach them more adaptive ways of experiencing and addressing the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral fallout from the abuse (Silverman et al., 2008). Similarly, cognitive-behavioral approaches with older adolescents and adults are effective for modifying abuse-related cognitive distortions (McDonagh et al., 2005; Ward, 2000), although research with male survivors specifically requires further investigation. Broader prevention efforts focusing on the societal messages that support these cognitive distortions are also warranted.

Findings of this study corroborate those of many others: alcohol intoxication fuels men’s sexual aggression intentions (Testa, 2002; Davis, 2010). As such, intervention programs that focus on reducing alcohol consumption, even without a focus on sexual aggression, may indirectly reduce sexual assault perpetration through reduced drinking. Foubert’s sexual aggression prevention program has also been shown effective at reducing men’s rates of sexual aggression and seems particularly promising in light of its recently-added components that address the intersection of alcohol and sexual assault (Foubert & Newberry, 2006). Our exploratory analyses suggest that alcohol intoxication may uniquely exacerbate the cognitive distortions of men with a CSA history; thus, these men may especially benefit from interventions designed to remedy maladaptive beliefs regarding alcohol’s facilitation of sexual assault.

The current study underscores how pervasive the effects of CSA are in the lives of men – even to the extent that these effects emerge in laboratory protocols years after the abuse. Unfortunately, these findings also support previous research establishing that these effects include the facilitation of sexual aggression against women. More research specifically examining the proximal effects of alcohol intoxication and how they influence men’s perceptions, cognitions, and emotions during sexual situations – both independently and in conjunction with sexual abuse history – would further elucidate the relationships among these sexual aggression risk factors. Moreover, both this and other research (e.g. Davis et al., 2008) has demonstrated that sexual violence and sexual risk are not independent behaviors. Improving our understanding of the pathways through which a history of CSA, as well as alcohol intoxication, may contribute to men’s engagement in nonconsensual, unprotected sexual behavior could greatly enhance sexual health education and intervention efforts for both men and women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants to the first author from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01-AA017608 and R21-AA016283).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/VIO

References

- Abbey A, McAuslan P. A longitudinal examination of male college students’ perpetration of sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:747–756. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill M, BeShrears A, Clinton-Sherrod A, Zawacki T. Cross-sectional predictors of sexual assault perpetration in a community sample of single African American and Caucasian men. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:54–67. doi: 10.1002/ab.20107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Parkhill MR, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Saenz C. Alcohol’s role in men’s use of coercion to obtain unprotected sex. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1329–1348. doi: 10.1080/10826080902961419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Monique Clinton A, McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: what do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Beadnell B, Lindhorst TP. Predictors of sexually coercive behavior in a nationally representative sample of adolescent males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:1129–1147. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC. The influence of alcohol expectancies and intoxication on men’s aggressive unprotected sexual intentions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:418–428. doi: 10.1037/a0020510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Logan-Greene PL. Young men's aggressive tactics to avoid condom use: A test of a theoretical model. Social Work Research. doi: 10.1093/swr/svs027. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Norris J, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Men’s likelihood of sexual aggression: The influence of alcohol, sexual arousal and violent pornography. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Schraufnagel TJ, George WH, Norris J. The use of alcohol and condoms during sexual assault. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2008;2:281–290. doi: 10.1177/1557988308320008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiIorio C, Hartwell T, Hansen N. Childhood sexual abuse and risk behaviors among men at high risk for hiv infection. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:214–219. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Browne A. The traumatic impact of child sexual abuse: A conceptualization. Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1985;55:530–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1985.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foubert JD, Newberry JT. Effects of two versions of an empathy-based rape prevention program on fraternity men’s survivor empathy, attitudes, and behavior intent to commit rape or sexual assault. Journal of College Student Development. 2006;47:133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola P, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598–607. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AM, Bennett T, Sloan L, Marx BP, Juergens J. The impact of alcohol and alcohol expectancies on male perception of female sexual arousal in a date rape analog. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9:380–388. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.4.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MS, Fischer AR. Does entitlement mediate the link between masculinity and rape-related variables? Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2001;48:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JD, Noel NE, Sutter Hernandez J. Alcohol and male acceptance of sexual aggression: The role of perceptual ambiguity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:1186–1200. [Google Scholar]

- Lisak D, Hopper J, Song P. Factors in the cycle of violence: Gender rigidity and emotional constriction. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:721–743. doi: 10.1007/BF02104099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh C, Gidycz CA. A prospective analysis of the relationship between childhood sexual victimization and perpetration of dating violence and sexual assault in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:732–749. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAndrew C, Edgerton RB. Drunken comportment: A social explanation. Oxford, England: Aldine; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Malamuth NM, Sockloskie RJ, Koss MP, Tanaka JS. Characteristics of aggressors against women: testing a model using a national sample of college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:670–681. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.5.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Rohsenow DJ. Cognitive processes in alcohol use: Expectancy and the balanced placebo design. Advances in Substance Abuse. 1980;1:159–199. [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Gross AM, Adams HE. The effect of alcohol on the responses of sexually coercive and noncoercive men to an experimental rape analogue. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research & Treatment. 1999;11:131–145. doi: 10.1177/107906329901100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh A, Friedman M, McHugo G, Ford J, Sengupta A, Mueser K, et al. Randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:515–524. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Recommended Council Guidelines on Ethyl Alcohol Administration in Human Experimentation. 2005 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/ResearchResources/job22.htm.

- Norris J, Davis KC, George WH, Martell J, Heiman JR. Alcohol’s direct and indirect effects on men’s self-reported sexual aggression likelihood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:688–695. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton AE, Wakeling HC. Entitled to sex: Attitudes of sexual offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression. 2009;15:289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson ZD, Janssen E, Heiman JR. The association between sexual aggression and HIV risk behavior in heterosexual men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:538–556. doi: 10.1177/0886260509334414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Paylan SS, Gentes-Hawn A, Hoaken PNS. Alcohol effects executive cognitive functioning differentially on the ascending versus descending limb of the blood alcohol concentration curve. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:773–779. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065434.92204.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny AD, Miller BA, Kaplan HB. The brief MAST: A shortened version of the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1972;129:342–345. doi: 10.1176/ajp.129.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaschek DLL, Ward T. The implicit theories of potential rapists: What our questionnaires tell us. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2002;7:385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Schacht RL, Stoner SA, George WH, Norris J. Idiographically-determined versus standard absorption periods in alcohol administration studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:925–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Davis KC, George WH, Norris J. Childhood sexual abuse in males and subsequent risky sexual behavior: A potential alcohol-use pathway. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Coury-Doniger P, Urban MA. Childhood sexual abuse and sexual risk behavior among men and women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:720–731. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MC. The effects of selective evaluation on the perception of female cues in sexually coercive and noncoercive males. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1993;22:415–433. doi: 10.1007/BF01542557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Ortiz CD, Viswesvaran C, Burns BJ, Kolko DJ, Putnam FW, Amaya-Jackson L. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:156–183. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M. The impact of men’s alcohol consumption on perpetration of sexual aggression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1239–1263. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TA, Fremouw W. Moderating variables of the sexual “victim to offender cycle” in males. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:382–387. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Extent, nature, and consequences of rape victimization: Findings from the national violence against women survey. (No. 210346) Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ward T. Sexual offenders’ cognitive distortions as implicit theories. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Smith J. Sexual assault perpetration and re-perpetration: From adolescence to young adulthood. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2004;31:182–202. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield CL, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ. Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:166–185. [Google Scholar]