Abstract

Multiple isoforms of inhibitory Gα-subunits (Gαi1,2,3, as well as Gαo) are present within the heart, and their role in modulating pacemaker function remains unresolved. Do inhibitory Gα-subunits selectively modulate parasympathetic heart rate responses? Published findings using a variety of experimental approaches have implicated roles for Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαo in parasympathetic signal transduction. We have compared in vivo different groups of mice with global genetic deletion of Giα1/Gαi3, Gαi2, and Gαo against littermate controls using implanted ECG telemetry. Significant resting tachycardia was observed in Gαi2−/− and Gαo−/− mice compared with control and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mice (P < 0.05). Loss of diurnal heart rate variation was seen exclusively in Gαo−/− mice. Using heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, compared with littermate controls (4.02 ms2 ± 1.17; n = 6, Gαi2−/−) mice have a selective attenuation of high-frequency (HF) power (0.73 ms2 ± 0.31; n = 5, P < 0.05). Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− and Gαo−/− cohorts have nonsignificant changes in HF power. Gαo−/− mice have a different basal HRV signature. The observed HRV phenotype in Gαi2−/− mice was qualitatively similar to atropine (1 mg/kg)-treated controls [and mice treated with the GIRK channel blocker tertiapinQ (0.05 mg/kg)]. Maximal cardioinhibitory response to the M2-receptor agonist carbachol (0.5 mg/kg) compared with basal heart rate was attenuated in Gαi2−/− mice (0.08 ± 0.04; n = 6) compared to control (0.27 ± 0.04; n = 7 P < 0.05). Our data suggest a selective defect of parasympathetic heart rate modulation in mice with Gαi2 deletion. Mice with Gαo deletion also have a defect in short-term heart rate dynamics, but this is qualitatively different to the effects of atropine, tertiapinQ, and Gαi2 deletion. In contrast, Gαi1 and Gαi3 do not appear to be essential for parasympathetic responses in vivo.

Keywords: inhibitory G proteins, heart rate, heart rate variability, parasympathetic

heart rate is regulated via the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. In particular, the release of ACh from vagal nerve efferents slows heart rate; however, the biological signal transduction processes involved remain unclear. Investigators have largely focused on two potential electrophysiological mechanisms in cardiac pacemaking tissues. K+ currents activated through M2-muscarinic receptors (KACh) are present in atrial and nodal regions and are carried by G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRK) (5, 48, 49). Muscarinic receptor-mediated GIRK channel activation results in membrane hyperpolarization and heart rate slowing. The activation of KACh is inhibited by pertussis toxin, implicating the family of inhibitory G proteins (Gαi/o) (33). Adenosine, which activates A1 receptors, leads to heart rate slowing through similar mechanisms. A second potential mechanism is modulation of hyperpolarization-activated cation currents (If or Ih) in pacemaker cells. Activation of these nonselective cation channels leads to membrane depolarization and thus accelerates heart rate. Membrane hyperpolarization and the direct binding of cAMP to the protein opens the channel (35). Thus a decrease in cAMP via inhibition of adenylate cyclase by activated Gαi/o subunits could inhibit the channel and slow heart rate.

The influence of the parasympathetic system can be detected in the beat-to-beat variation of heart rate. In vivo, using frequency domain analysis of R-R interval, heart rate shows characteristic patterns of variability: a low frequency (LF) component (>6-s cycle length in man) is determined by sympathetic and parasympathetic drive, and a high-frequency (HF) component (2.5- to 6-s cycle length in man) is solely governed by parasympathetic innervation (32, 41). Heart rate variability (HRV) analysis has also been applied to murine models (11, 48) with some debate as to whether sympathovagal balance can be determined in such a straightforward fashion (13, 21, 43). In a clinical setting, loss of HRV has been recorded just prior to the onset of ventricular tachycardia in patients with implantable cardiac defibrillators and independently predicts sudden cardiac death in heart failure populations (34). Additionally, abnormal HRV predicts adverse outcome in acute myocardial infarction, hypertension, and heart failure (9). Finally, heart rate is integrated with blood pressure and respiratory control via a series of neural cardiac reflexes involving a number of different regions in the brain stem (40), and these should be considered in the interpretation of in vivo experimental results.

Various attempts have been made to address the identity of the molecular players in vagal-mediated heart rate slowing. It is generally agreed that the M2 muscarinic receptor is the major isoform responsible for vagally mediated bradycardia in conduction tissues, and this is supported by studies on mice with global genetic deletion of the gene encoding for this protein (8). KACh is a heterotetramer of Kir3.1\3.4 (also known as the G protein gated inwardly rectifying K channel, i.e., GIRK1\GIRK4), and studies in knockout mice support the importance of Kir3.4 (48). The channel is directly activated by Gβγ (27), and its role has been validated in an experiment with cardiac-restricted overexpression of nonisoprenylated Gγ subunit, which led to reduced membrane Gβγ and impaired parasympathetic heart rate control (11). Despite Gβγ being the direct activator of the channel, recent work has revealed the importance of inhibitory Gα subunits in determining selectivity of this particular response (25, 26, 31, 38). However, the identity of the inhibitory Gα isoform(s) involved in vivo remains unclear. It is known that Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3 isoforms are widely expressed. Gαi2 is the predominant cardiac isoform (12). Gαo is expressed abundantly in neuronal tissue, comprising 1% of brain tissue mass and has critical functions in neuronal growth cone migration (28, 47). Gαo expression within cardiac myocytes has only recently been determined categorically and has been implicated in Ca2+ channel modulation; its presence previously being accounted for by neuronal contamination of cardiac preparations (50). Do specific Gαi/o protein subunits perform specific functions in vivo? Or is there significant redundancy in function? Our hypothesis was that there was little redundancy in function and that Gαi2 is the isoform of major importance in pacemaker tissues in controlling heart rate via the vagus nerve.

With regard to cardiac pacemaking function, the identity of the inhibitory Gα-subunit protein(s) involved in modulating parasympathetic control of intrinsic cardiac automaticity remains undetermined. Data exist supporting roles for Gαi2, Gαi3, and Gαo. Specifically, Gαi2 and Gαi3 (but not Gαo) rescue K+ACh current activation in ES-derived cardiomyocytes (39). Gαi3 when expressed in heterologous expression systems seems to couple GIRK channel activation particularly efficaciously (15), and lastly, murine Gαo deletion has recently been reported to selectively impair parasympathetic responses (6). Given the current controversy, our aim was to perform an in vivo study in mice with global genetic deletion of Gαi1/Gαi3 (combined deletion), Gαi2, or Gαo against littermate controls on the same genetic background.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gene-targeted mice.

Mice with global deletion of Gαi2, Gαo (both splice variants GαoA and GαoB), and Gαi1/Gαi3 (deletion of both Gαi1 and Gαi3) maintained on a Sv129 background were compared with wild-type littermate controls. The gene-targeting strategy and confirmation of relevant Gαi/o deletion have previously been investigated (18, 20, 37). Genomic DNA was isolated from tail snips, and PCR was used to confirm genotype using the following primers combinations for Gαi1 (i1EX2F1: 5′-GAATC TGGAA AGAGT ACCAT TGTGA-3′, i1EX3R1: 5′-GTCTC CGAAG TCGAT TTTCA ACCTC-3′, NeoR3: 5′-GATTG TCTGT TGTGC CCAGT CATAG-3′), Gαi3 (i3Ex6F1: 5′-GTGGC CAAAG ATCCG AACGA A-3′, iEx7R1: 5′-ttcat gcttt catgc attcg gttc-3′, NeoF1: 5′-TGCCG AGAAA GTATC CATCA TG-3′), Gαi2 (i2F8: 5′-gatca tcc gaga tggct actca gaag-3′, i2F14: 5′-CAGGA TCATC CATGA AGATG GCTAC-3′, i2R7: 5′-CCCCT CTCAC TCTTG ATTTC CTACT GACAC-3′, NeoR2: 5′-GCACT CAAAC CGAGG ACTTA CAGAA C-3′), and Gαo (oEx5F: 5′-GGACA GCCTG GATCG GATTG G-3′, OEx6R: 5′ACCTG GTCAT AGCCG CTGAG TG-3′, NeoR3: 5′-GATTG TCTGT TGTGC CCAGT CATAG-3′). For example, when we genotyped the Gαi2−/− mice with PCR, the i2F8 and i2R7 primer pair gave a product of 805 base pairs from the wild-type allele, while the i2F14 and NeoR2 pair gave a product of 509 base pairs from the knockout mice. Mice were aged 3–4 mo, weighing 20–25 g at time of telemetry implantation. We observed significant early Gαo−/− lethality (19). Therefore, pharmacological experiments in Gαo−/− were performed at 1 mo of age and compared against control age-matched littermates. Only 4 Gαo−/− mice (3.5% survival) survived long enough (3–4 mo) for telemetry implantation. The animals were allowed free access to standard chow and water ad libitum. The animals were housed in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle in a temperature-controlled environment (21–23°C). The work conforms with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). All procedures were approved by the University College London Animal Ethics Committee and performed in accordance with British Home Office regulations and guidance (project license PPL\6732).

ECG telemetry.

The telemetry probe (TEA-F20; DSI, St. Paul, MN) was implanted into mice to record ECG data in the conscious animal. Tunnelled electrodes were secured in a lead II configuration connected to a telemetry device, which was implanted either subcutaneously or intra-abdominally under strict aseptic surgical technique. After a minimum 2-wk period of surgical recovery, ECG signals were acquired continuously by radio-telemetry. Initially, mean day and night HR (12 h light to dark cycle) were determined over 48 h from the mean heart rate determined for 15 s every 30 min. Subsequently, we acquired R-R interval variability signal from ECG data streamed over 20 min at high sampling frequency (2 kHz), digitized and analyzed using a HRV extension module of CHART 4.0 (ADInstruments, Oxford, UK). We based our recording analysis methodologies on a previous report (7). Before performing HRV analysis, recording artifact was excluded and the raw ECG strip was manually inspected to confirm sinus rhythm and ensure good-quality ECG signal. A threshold R-wave-sensing algorithm was applied to detect all R-R intervals. Ectopic beats were defined as those that were 2 times above or below the average R-R interval; these beats were excluded from analysis, and no averaged or interpolated beats were used to replace them. Frequency domain analysis was performed after fast Fourier transform (FFT) using 1024 spectral points and a half overlap within a Welch window. HRV data were analyzed in both frequency and time domains using standard HRV parameters: specifically, SDn-n (ms), standard deviation of all R-R intervals in sinus rhythm; RMSSD (ms), root mean square of successive differences; and total power (TP) (ms2/Hz) is the integral sum of total variability after FFT over the entire recorded frequency (0–4.0 Hz) range recorded from power spectral density plots. Cutoff frequencies previously determined to be accurate for mice were used to divide signal into three major components, very low frequency (VLF < 0.4 Hz), low frequency (LF 0.4–1.5 Hz), and high frequency (HF 1.5–4.0 Hz) (7). Normalization to exclude VLF was also performed. Normalized low frequency (nLF) = LF/(TP-VLF) × 100 and normalized high frequency (nHF) = HF/(TP-VLF) × 100.

To determine the effect of vagolytics on heart rate variability signature, mice underwent pharmacological intervention studies. Initially, the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (1 mg/kg) (Sigma, UK) was administered to wild-type (WT) controls and HRV redetermined after a 15-min equilibration period using an identical recording protocol over 20 min. After a 48-h drug washout phase, in a separate experiment, HRV was reevaluated using the GIRK channel blocker tertiapinQ (0.05 mg/kg) (Tocris Bioscience, Cornwall, UK).

Chronotropic responses after pharmacological provocation.

Mice were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane and ECG signal recorded after stabilization. Carbachol (0.5 mg/kg), a M2 selective agonist was administered intraperitoneally and heart rate was redetermined at regular intervals to evaluate relative cardioinhibitory response. Maximal cardioinhibitory response occurred by 3 min. We determined inhibitory response compared with basal heart rate in each mouse and expressed heart rate change as relative cardioinhibition. A similar experiment was performed using the selective A1-receptor agonist 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA; 0.1 mg/kg) over a 10-min time course. Our cardioinhibition protocols are based on previous reports specifically investigating parasympathetic heart rate modulation (10, 11, 30). Similarly, CCPA is a pure A1 receptor agonist (1,000-fold A1 to A2 selectivity), which results in similar chronotropic effects (10, 48). Similar experiments were performed after pretreatment with tertiapinQ (0.05 mg/kg) to determine the effects of GIRK channel blockade on receptor-mediated heart rate slowing (5, 23).

Statistical analysis.

Mean statistical difference was analyzed using one-way ANOVA (with a Dunnett's post hoc test) or t-test where appropriate. This approach is standard in the literature (e.g., 7, 17); however, given the small sample size, a case could be made for using nonparametric analysis. In this regard, we also performed a Kruskal-Wallis test, and the key data comparisons are still significant (or not) to the same degree. However, the parametric results are presented, and data are shown as means ± SE. A P value of <0.05 was taken to be statistically significant (statistical P values are represented by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

RESULTS

Gαi2 and Gαo deletion increases heart rate.

Using telemetry in conscious mice, we observed significant differences in mean heart rate both at night and during the day with respect to inhibitory Gα subunit isoform. Mice are largely active at night and sleep during the day, and the increased nocturnal heart rate reflects this. Gαi2−/− [618 ± 12 beats per minute (bpm), n = 5] and Gαo−/− (656 ± 8 bpm, n = 4) mice have significant nocturnal tachycardia compared with control (569 ± 15 bpm, n = 6). Daytime heart rate reflected a similar pattern (Fig. 1). Daytime HR in Gαo−/− mice (634 ± 8 bpm, n = 4) was faster than control (517 ± 18 bpm, n = 6). Similarly Gαi2-deficient mice show a trend toward faster daytime heart rate (560 ± 16, n = 5), but this did not reach statistical significance. In comparison, Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− had nocturnal and daytime heart rates comparable with control.

Fig. 1.

Mean day and nocturnal heart rate in mice with selective Gαi/o deletion. A: mean heart rate measured every six hours in a single experimental mouse with indicated genotype. B: summary of mean heart rate in each Gαi/o cohort both during the day and at night with respect to control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P value < 0.001).

Effect of inhibitory G protein subunit deletion on diurnal HR variation.

Significant diurnal variation in heart rate was observed in WT, Gαi2 −/−, and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/−. However, Gαo-deficient mice demonstrated a pronounced lack of diurnal HR variation (Fig. 1).

Effects of atropine and tertiapinQ on HRV in wild-type mice.

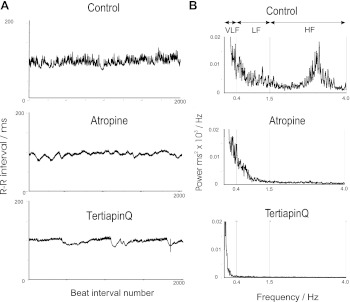

We first examined heart rate variability in conscious wild-type animals (n = 6, all groups) using telemetry and sought to compare this with pharmacological intervention (Fig. 2 and Table). Clear differences can be seen from tachogram recordings and power spectral density (PSD) plots between control, atropine, and tertiapinQ-treated animals (Fig. 2). Control mice reveal significant R-R variability under basal conditions, and PSD plots reveal spectral peaks within both the LF and HF range. The administration of atropine or the selective GIRK channel blocker tertiapinQ caused qualitatively similar changes in HRV (Table 1). This was best revealed in the frequency domain, where with both drugs, the LF component of power, HF component of power, and TP were all attenuated compared with control (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Representative tracings from wild-type control mice in the time (A) and frequency domain (B) recorded from conscious freely moving mice. A: raw tachogram tracings of R-R interval recorded over 2,000 consecutive beats from control (top), after addition of atropine (middle) and TertiapinQ (bottom). B: frequency domain power spectral density plots obtained from 20 min of recording from control (top) after atropine (middle) and tertiapinQ (bottom) administration.

Table 1.

Mean parameters for heart rate variability

| Control | Atropine | TertiapinQ | Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− | Gαi2−/− | Gαo−/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| RMSSD/ms | 3.52±0.46 | 2.01±0.55 ns | 1.26±0.37* | 3.03±0.34 ns | 1.44±0.29† | 2.48±0.45 ns |

| SDn-n/ms | 7.19±0.43 | 3.83±0.95 ns | 4.96±0.73 ns | 8.94±1.39 ns | 4.67±1.08 ns | 5.62±0.92 ns |

| TP/ms2 | 29.2±3.1 | 8.12±4.36† | 7.20±1.54† | 30.7±4.3 ns | 13.4±6.1 ns | 23.1±6.3 ns |

| VLF/ms2 | 18.4±2.2 | 4.76±2.92† | 5.68±1.26† | 22.9±3.2 ns | 11.2±5.8 ns | 18.6±4 ns |

| LF/ms2 | 6.95±0.66 | 1.61±0.89† | 0.61±0.37† | 4.98±1.04 ns | 1.30±0.52† | 1.90±1.34* |

| nLF/nu | 64.1±6 | 33.8±7.8 ns | 42.0±3.39 ns | 62.9±3.9 ns | 56.0±7.6 ns | 33.8±7.3 ns |

| HF/ms2 | 4.02±1.17 | 1.30±0.72† | 0.73±0.49† | 2.76±0.56 ns | 0.73±0.31* | 1.90±0.91 ns |

| nHF/nu | 33.3±5.3 | 45.1±2.99† | 42.9±2.4 ns | 35.5±3.9 ns | 32.6±5.3 ns | 53.0±5.6 ns |

| LF/HF | 2.28±0.47 | 0.90±0.30 | 1.01±0.13 | 1.93±0.31 | 2.11±0.54 | 0.71±0.25 |

All observations are expressed as means ± SE and are compared against control;ns = not significant.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01. RMSSD, root mean square of successive differences; SDn-n, SD of “normal” sinus rhythm R-R/n-n intervals; TP, total power; VLF power, very low frequency <0.4 Hz); LF power, low frequency 0.4–1.5 Hz; HF power, high frequency 1.5-4.0 Hz. nHF and nLF are normalized to exclude VLF and presented in normalized power units.

Fig. 4.

Variations in low-frequency (LF; A) and high-frequency (HF; B) power with the different interventions. Bar graphs showing the magnitude of the variations in power between the different interventions (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

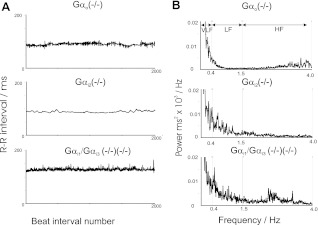

Global Gαi/o deletion, and heart rate dynamics.

We next investigated HRV with respect to deletion of inhibitory Gα subunits (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mice exhibited HRV characteristics that were not significantly different from wild-type controls under basal conditions in both the time and frequency domain (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 1). Tachogram tracings and measurements in the time domain in Gαi2−/− mice show suppression of R-R variability compared with controls (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 1). However, more revealingly in the frequency domain, as with atropine and tertiapinQ, there is a significant reduction of both the LF and HF component of power compared with control (Table 1 and Figs. 3 and 4). We were able to implant telemetry devices in four Gαo−/− mice, and a different pattern of HRV modulation was noted. In the frequency domain, TP and HF power was not changed, but there was a selective and significant reduction of LF power compared with control (Table and Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Heart rate variability in Gαi/o knockout mice presented in the time domain (A) and frequency domain (B) recorded from conscious freely moving mice. Tachograms (A) and power spectral density plots (B) in Gαo−/− (top) Gαi2−/− (middle), and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− (bottom). A recording from a control mouse is shown in Fig. 2.

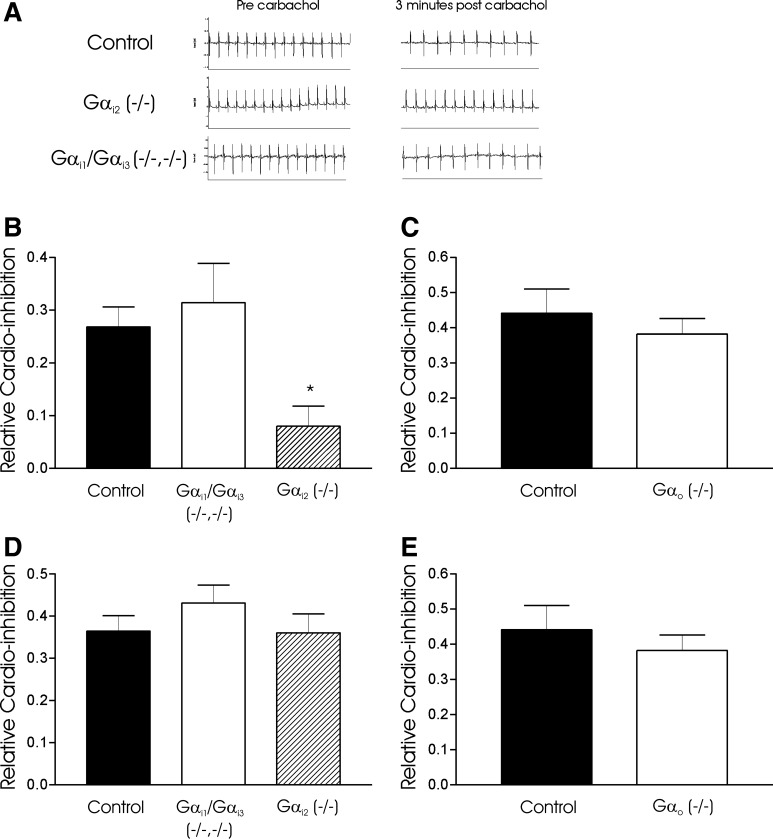

Attenuation of cardioinhibitory response to carbachol is dependent on Gαi/o isoform.

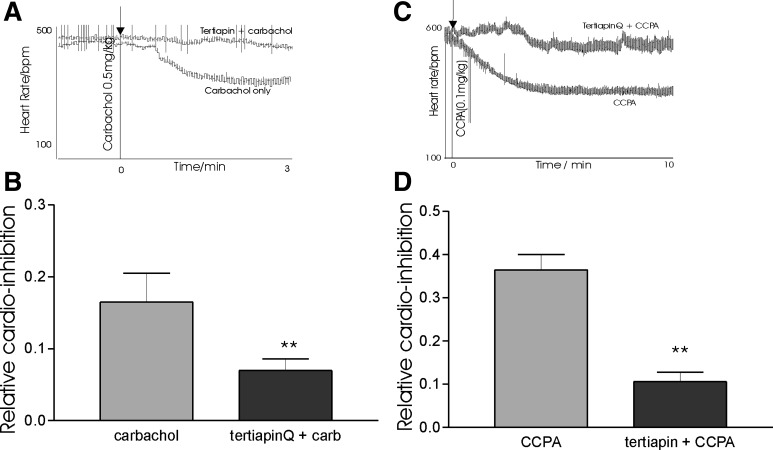

We next determined negative chronotropic response to carbachol (0.5 mg/kg) and on a separate occasion CCPA (0.1 mg/kg) in anesthetized mice. Selective attenuation of cardioinhibitory response to carbachol was seen in Gαi2−/− (0.08 ± 0.04, n = 6) but not control (0.27 ± 0.04, n = 7) or Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− (0.31 ± 0.07, n = 6) mice (Fig. 5). As no differences were seen in mean cardioinhibition between littermates and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mice, a pooled comparison of carbachol response was determined in the presence and absence of tertiapinQ. TertiapinQ attenuated cardioinhibition (0.07 ± 0.02, n = 10) compared with carbachol alone (0.16 ± 0.04, n = 10) in this cohort (Fig. 6). Owing to early lethality and considerable problems of working with Gαo−/− mice, we were unable to directly compare against control mice (3–4 mo). As a practical alternative, carbachol responses were measured at 1 mo of age against wild-type littermates. After carbachol administration, mean cardioinhibition in Gαo−/− was (0.16. ± 0.16, n = 4) compared with control (0.32 ± 0.1, n = 6). While a trend to reduced inhibition was observed, substantial variation in response occurred, perhaps reflecting variable pharmacokinetics in such small mice. No differences were observed between control (0.36 ± 0.04, n = 6), Gαi2−/− (0.36 ± 0.04, n = 5) or Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− (0.43 ± 0.04, n = 6) (Fig. 5) in CCPA induced heart rate slowing. We observed no significant difference in CCPA response between Gαo−/− mice (0.38 ± 0.04) and littermate controls (0.44 ± 0.07) (Fig. 5). However, in the presence of tertiapinQ, CCPA-induced cardioinhibition was attenuated (0.11 ± 0.02, n = 6) compared with CCPA only-treated controls (0.36 ± 0.04, n = 6) (Fig. 6). We have determined the intrinsic heart rate of the mouse (albeit on a mixed Sv\129:C57\BL background). Resting heart rate was determined in awake telemeterized mice and propranolol (1 mg/kg ip) and atropine (1 mg/kg ip) administered. The change in heart rate stabilized after 5 min and increased from 419 ± 34 to 537 ± 68 (n = 5) bpm.

Fig. 5.

Negative chronotropic responses to carbachol and 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA). A: raw ECG tracings from wild-type (WT) and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mouse before and 3 min after carbachol administration. Note a significant negative chronotropic response (increasing R-R interval). Gαi2−/− (n = 7) mice have a selective attenuation of heart rate slowing response to carbachol compared with Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− (n = 6), Gαo−/− (n = 6), and WT (n = 6) B and C: relative cardio-inhibition to carbachol at 3 min after drug administration with respect to Gαi/o isoform (*P < 0.05). D and E: no significant difference in bradycardic response to CCPA in WT, Gαi2−/−, Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− or Gαo−/− mice. Note that the Gαo−/− mice and respective controls are studied at a younger age (see materials and methods).

Fig. 6.

The effects of tertiapinQ on carbachol and CCPA-induced bradycardia in a cohort of WT and Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mice (n = 10). A: raw tracing of heart rate response to carbachol in an individual experiment; arrow indicates point of carbachol administration. B: relative cardio-inhibition to carbachol (carb) in the presence and absence of tertiapinQ. C: raw tracing of heart rate response to CCPA in an individual experiment; arrow indicates CCPA administration. D: relative cardio-inhibition to CCPA in the presence and absence of tertiapinQ. B and D: **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to investigate the role of the different inhibitory G protein isoforms in heart rate regulation in the intact whole animal and, in particular, the isoform(s) responsible for the modulation of heart rate via the parasympathetic system. HRV can be influenced by processes intrinsic and extrinsic (i.e., cardiovascular reflexes) to the pacemaking tissues, while it is generally accepted that the administration of carbachol and CCPA (and related agonists and antagonists) is dominated by receptor-mediated processes occurring in the sinoatrial (SA) node (e.g., see Ref. 14).

Tachycardia in mice with global G protein deletion.

In Gαi2−/− mice, there was preservation of the diurnal variation in heart rate, but there was a significant increase in heart rate at night and a trend to a more rapid heart rate during the day. We interpret this to be a consequence of vagal withdrawal (see Role of Gai2 in heart rate regulation). The effects of autonomic tone on HR are complex. Ambient temperature and levels of physical activity modulate sympathovagal balance. Specifically, it is possible for mice to have high vagal tone under some conditions (4, 42). Recently, investigators have reported vagal predominance in mice, if appropriate care is taken to ensure appropriate recovery from surgery (21, 24). In mice with global genetic deletion of Gαo, there was a significant increase in heart rate both during the night and day and a loss of circadian rhythm. One possible explanation for this, given that Gαo is by far the predominant inhibitory Gα within brain tissue is that Gαo may regulate central control of autonomic tone. The observed HRV phenotype is qualitatively very similar to sympathetic overactivity as in seen in heart failure.

Role of Gαi2 in heart rate regulation.

Heart rate modulation is of vital physiological importance. Analysis of basal HRV signature can be used to determine the influence of autonomic tone on heart rate. Autonomic afferents are responsible for beat-to-beat variation in heart rate. HF power is determined by respiratory sinus arrhythmia and parasympathetic output to the heart while the LF component likely reflects the response of heart rate to short-term variations in blood pressure mediated by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems (9). The LF:HF ratio may reflect the sympathovagal balance, although this is more controversial. The resting heart rate of the mouse is approximately 10-fold higher than man, but heart period shows similar patterns of HF and LF with comparably higher-frequency ranges (17); however, the role of murine VLF remains unclear. There has been some debate as to whether HRV signal can be applied to mice, perhaps reflecting a number of methodological and perhaps strain differences during recording. However, it has been proposed that the HF component reflects respiration but via a direct modulation of the parasympathetic response through changes in pressure in the cardiac chambers (16, 17). The LF component reflects various cardiorespiratory reflexes with modulation via both arms of the autonomic nervous system and the value of the LF:HF ratio is not clear. Thus we investigated the empirical pharmacological HRV signature in the 129\Sv strain of mouse. Administration of atropine, a muscarinic receptor antagonist, and tertiapinQ, a relatively selective GIRK channel blocker, to conscious animals with telemetry probes in situ revealed an abrogation of HRV. In particular, there was a generalized reduction in all frequency components namely VLF, LF, and HF. This pattern was also seen in the mice with global genetic deletion of Gαi2 and thus would be consistent with an intersection in the signaling between the M2 receptor and the GIRK channel in cardiac and, in particular, SA nodal cells. In the clinical setting Gαi2 upregulation, induced by pravastatin therapy, has also been reported to selectively increase HF power, suggesting that Gαi2 may be a critical mediator of parasympathetic tone, as have we observed (46). How does Gαi2 modulate vagal heart rate slowing? We propose two mechanisms; in our hands, pharmacological GIRK channel blockade with tertiapinQ produces a HRV signature (↓Total, ↓LF, and ↓HF power) similar to atropine treatment and that observed in Gαi2−/− mice, implicating GIRK channel activation in heart rate slowing. Second, previous work in the Gαi2−/− line has demonstrated that in cardiac tissue Gαi2 (but not Gαo) selectively couples to inhibition of adenylate cyclase activity (19, 37). Elevated basal (and receptor mediated) cAMP concentration may lead to tachycardia through If channel activation in the sinus node.

Our second finding was that Gαi2−/− mice had selective attenuation of carbachol-induced bradycardia compared with control. In our studies, we did not combine this approach with β-blockade for a number of reasons. β-blockade has been combined with pressor challenge with an α1-adrenoreceptor agonist to elicit heart rate slowing via the baroreceptor reflex. We preferred a more direct strategy, as these reflexes may be impaired in the various mice as discussed in Tachycardia in mice with global G protein deletion. A second possibility is that β-blockade could be combined with carbachol administration. We were wary of systemic β-blockade, as it may in itself add additional complexity through central nervous system (CNS) and blood pressure effects. The methods used for looking specifically at carbachol-induced HR slowing have been used by several other groups (3, 10, 30, 48). Some studies have presumed a sympathetic predominance to the mouse heart rate, in such a setting β-blockade would be necessary to exclude sympathetic withdrawal (rather than vagal activation) (44). However, this assumption has been questioned recently (21, 24, 42). In our own hands, we have also determined a significant vagal component to resting HR in mice after intrinsic heart rate determination with dual autonomic blockade.

Effects of genetic deletion of Gαo.

The effects of global genetic deletion of Gαo are subtler. There is an increased heart rate with loss of diurnal rhythm and fairly selective loss of the LF component of HRV with preserved total power. However, carbachol still has a negative chronotropic effect. This signature is different from that following pharmacological intervention with atropine and tertiapinQ and mice with genetic deletion of Gαi2. Gαo is expressed at higher levels than other inhibitory G proteins in neuronal tissue, and mice with deletion of Gαi1, Gαi2, or Gαi3 do not have a gross neurological phenotype. Given its importance in the central nervous system, it is possible that a CNS defect in Gαo signaling, for example, in the brain stem, could potentially affect regulation of HRV. There is also the formal possibility for such central effects to influence the phenotype with deletion of the other inhibitory heterotrimeric G proteins, and these questions will only be definitively answered by conditional gene-targeting approaches. The HRV phenotype of Gαo deletion is remarkably similar to that observed in patients with brain stem death (1). The observed increase in heart rate could be accounted for by excessive sympathetic drive, and our observations are also consistent with the findings that β-blockade increases the LF component of HRV in the mouse (the opposite is the case in man) (17). However, there are considerable practical problems working with these mice, and this made it difficult to characterize these phenomena further. New experimental approaches, such as conditional gene targeting, may be required to reach definitive conclusions about the role of Gαo in cardiovascular control and what influence it has on myocyte and pacemaker function. Recently, a constitutively active Gαo mouse was reported; however, heart rate dynamics in this model are currently unpublished (10). It is quite striking by comparison that Gαi1−/−/Gαi3−/− mice have essentially normal HRV and suggests these G proteins have a limited role in heart rate regulation that may be easily compensated for by the expression of others.

Purinergic A1 receptor activation and heart rate control.

A cardiac A1-specific overexpressing mouse line has resting bradycardia and heart block that is pertussis toxin sensitive, setting a precedent for the identification of the physiologically relevant inhibitory Gα subunit that couples this response (22). In contrast to the muscarinic system, in which we observed selectivity of inhibitory Gα-subunit responses, we did not see any clear effects of inhibitory G protein deletion on the negative chronotropic response after the addition of an A1 adenosine receptor agonist. The reasons for this remain unclear. It is possible that other G-proteins can effectively compensate for the absence of another or that all Gαi isoforms couple equally well to cardiac A1-receptor activation, as is seen in heterologous expression systems (26). Recently, an RGS-insensitive Gαo mutation has provided some evidence of signaling selectivity in this pathway in vitro but not in vivo (10). Our data, however, do support an important role for GIRK channel activation as a mediator of both A1 (and M2) receptor-mediated heart rate slowing, as has been suggested from studies in the GIRK4 knockout mouse (48).

Comparisons with previous studies and summary.

Our observations are discrepant with a number of studies, particularly those in in vitro systems. It is clear in heterologous expression systems that a wide range of inhibitory G proteins can mediate channel activation and there are suggestions that Gαi3 may do so particularly efficaciously (15, 26). Our aim here was to determine the physiologically relevant inhibitory Gα for in vivo heart rate control. A role for Gαi2 as a modulator of nodal function has been suggested from Gαi2 atrioventricular nodal gene transfer experiments in a swine model producing significant physiological atrioventricular block as a potential treatment for chronic atrial fibrillation (2). Experiments using an engineered RGS-resistant Gαi2 knockin mouse demonstrate dramatic sensitivity to M2 receptor activation, suggesting that Gαi2 appears to be a critical link between the M2 receptor and GIRK channels in mediating vagal responses (10). There is one study that measures HRV and shows a selective impairment with global Gαo deletion (6). However, there is a major technical difference with these studies and ours in that the mice were studied 24 h after surgery. In addition, there was no resting HRV, and this had to be evoked using methoxamine. We found, as have other investigators (17), that the mice need at least 14 days to recover from surgery and develop a characteristic resting HRV signature. Our findings on the importance of Gαi2 are consistent with those on the RGS-insensitive knockin mouse though the experimental findings are in the opposite direction, reflecting a gain vs. loss-of-function phenotype. Furthermore, a series of studies have highlighted the role of the transcription factor SREBP-1 as a potent and specific modulator of Gαi2/GIRK1 channel expression resulting in attenuated parasympathetic response to carbachol both in vitro and in vivo (29, 30).

Studies using global inhibitory Gα-subunit deletion have been highly informative (12, 36, 45); however, developmental adaptations, for example, the upregulation of compensatory Gαi/o isoforms during development could potentially limit interpretation. Previous studies in these or equivalent mouse lines have shown no evidence of compensatory cardiac-specific upregulation of other G protein isoforms in Gαo−/− mice (19), Gαi3−/− mice or Gαi2−/− mice (12). In the latter group Gαi3 upregulation occurs in the liver but not the heart. Additionally, we have also seen no evidence of cardiac Gα subunit compensation at an mRNA level from Gαi2−/− cardiac gene array profiling (unpublished observations). Therefore, we feel that our results are consistent with a central importance of Gαi2 modulating HRV- and M2 receptor-induced bradycardia in vivo.

Perspectives and Significance

Determination of the inhibitory Gα subunits involved in modulating parasympathetic responses in vivo is of critical importance to physiology. Our data suggest a selective defect of parasympathetic modulation of heart rate in vivo in mice with global genetic deletion of Gαi2. Specifically, these mice have elevated heart rates, loss of HRV comparable to that after the application of atropine and tertiapinQ, and an attenuation of heart rate slowing after the application of carbachol. In contrast, Gαi1 and Gαi3 do not appear essential for parasympathetic responses in vivo. Manipulating Gαi2 signaling within the heart may, therefore, be of therapeutic interest (2). Similarly, mice with Gαo deletion are tachycardic and have a defect in short-term heart rate dynamics, but this is qualitatively different to the effects of atropine, tertiapinQ, and Gαi2 deletion and may arise from defective central control of cardiovascular reflexes, as is seen in clinical subjects with brain stem death.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, the British Heart Foundation, and by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the comments of Dr. Muriel Nobles on the manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baillard C, Vivien B, Mansier P, Mangin L, Jasson S, Riou B, Swynghedauw B. Brain death assessment using instant spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Crit Care Med 30: 306–310, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer A, McDonald AD, Nasir K, Peller L, Rade JJ, Miller JM, Heldman AW, Donahue JK. Inhibitory G protein overexpression provides physiologically relevant heart rate control in persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation 110: 3115–3120, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cifelli C, Rose RA, Zhang H, Voigtlaender-Bolz J, Bolz SS, Backx PH, Heximer SP. RGS4 regulates parasympathetic signaling and heart rate control in the sinoatrial node. Circ Res 103: 527–535, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De AK, Wichi RB, Jesus WR, Moreira ED, Morris M, Krieger EM, Irigoyen MC. Exercise training changes autonomic cardiovascular balance in mice. J Appl Physiol 96: 2174–2178, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drici MD, Diochot S, Terrenoire C, Romey G, Lazdunski M. The bee venom peptide tertiapin underlines the role of I(KACh) in acetylcholine-induced atrioventricular blocks. Br J Pharmacol 131: 569–577, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan SZ, Christe M, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Go but not Gi2 or Gi3 is required for muscarinic regulation of heart rate and heart rate variability in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 357: 139–143, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ecker PM, Lin CC, Powers J, Kobilka BK, Dubin AM, Bernstein D. Effect of targeted deletions of beta1- and beta2-adrenergic-receptor subtypes on heart rate variability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H192–H199, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher JT, Vincent SG, Gomeza J, Yamada M, Wess J. Loss of vagally mediated bradycardia and bronchoconstriction in mice lacking M2 or M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. FASEB J 18: 711–713, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frenneaux MP Autonomic changes in patients with heart failure and in post-myocardial infarction patients. Heart 90: 1248–1255, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu Y, Huang X, Zhong H, Mortensen RM, D'Alecy LG, Neubig RR. Endogenous RGS proteins and Galpha subtypes differentially control muscarinic and adenosine-mediated chronotropic effects. Circ Res 98: 659–666, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gehrmann J, Meister M, Maguire CT, Martins DC, Hammer PE, Neer EJ, Berul CI, Mende U. Impaired parasympathetic heart rate control in mice with a reduction of functional G protein betagamma-subunits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H445–H456, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gohla A, Klement K, Piekorz RP, Pexa K, vom DS, Spicher K, Dreval V, Haussinger D, Birnbaumer L, Nurnberg B. An obligatory requirement for the heterotrimeric G protein Gi3 in the antiautophagic action of insulin in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3003–3008, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross V, Tank J, Obst M, Plehm R, Blumer KJ, Diedrich A, Jordan J, Luft FC. Autonomic nervous system and blood pressure regulation in RGS2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R1134–R1142, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ieda M, Kanazawa H, Kimura K, Hattori F, Ieda Y, Taniguchi M, Lee JK, Matsumura K, Tomita Y, Miyoshi S, Shimoda K, Makino S, Sano M, Kodama I, Ogawa S, Fukuda K. Sema3a maintains normal heart rhythm through sympathetic innervation patterning. Nat Med 13: 604–612, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ivanina T, Varon D, Peleg S, Rishal I, Porozov Y, Dessauer CW, Keren-Raifman T, Dascal N. Galphai1 and Galphai3 differentially interact with, and regulate, the G protein-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem 279: 17260–17268, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janssen BJ, Leenders PJ, Smits JF. Short-term and long-term blood pressure and heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R215–R225, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janssen BJ, Smits JF. Autonomic control of blood pressure in mice: basic physiology and effects of genetic modification. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1545–R1564, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang M, Boulay G, Spicher K, Peyton M, Brabet P, Birnbaumer L, Rudolph U. Inactivation of the Gαi2 and Gαo genes by homologous recombination. Receptors Channels 5: 187–192, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang M, Gold MS, Boulay G, Spicher K, Peyton M, Brabet P, Srinivasan Y, Rudolph U, Ellison G, Birnbaumer L. Multiple neurological abnormalities in mice deficient in the G protein Go. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 3269–3274, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang M, Spicher K, Boulay G, Martin-Requero A, Dye CA, Rudolph U, Birnbaumer L. Mouse gene knockout and knockin strategies in application to alpha subunits of Gi/Go family of G proteins. Methods Enzymol 344: 277–298, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Just A, Faulhaber J, Ehmke H. Autonomic cardiovascular control in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R2214–R2221, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhof P, Fabritz L, Fortmuller L, Matherne GP, Lankford A, Baba HA, Schmitz W, Breithardt G, Neumann J, Boknik P. Altered sinus nodal and atrioventricular nodal function in freely moving mice overexpressing the A1 adenosine receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H145–H153, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura H, Yokoyama M, Akita H, Matsushita K, Kurachi Y, Yamada M. Tertiapin potently and selectively blocks muscarinic K+ channels in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 293: 196–205, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laude D, Baudrie V, Elghozi JL. Effects of atropine on the time and frequency domain estimates of blood pressure and heart rate variability in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 35: 454–457, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leaney JL, Milligan G, Tinker A. The G protein α subunit has a key role in determining the specificity of coupling to, but not the activation of G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ channels. J Biol Chem 275: 921–929, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaney JL, Tinker A. The role of members of the pertussis toxin-sensitive family of G proteins in coupling receptors to the activation of the G protein-gated inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5651–5656, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logothetis DE, Kurachi Y, Galper J, Neer EJ, Clapham DE. The beta gamma subunits of GTP-binding proteins activate the muscarinic K+ channel in heart. Nature 325: 321–326, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Offermanns S New insights into the in vivo function of heterotrimeric G-proteins through gene deletion studies. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 360: 5–13, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park HJ, Begley U, Kong D, Yu H, Yin L, Hillgartner FB, Osborne TF, Galper JB. Role of sterol regulatory element binding proteins in the regulation of Galpha(i2) expression in cultured atrial cells. Circ Res 91: 32–37, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park HJ, Georgescu SP, Du C, Madias C, Aronovitz MJ, Welzig CM, Wang B, Begley U, Zhang Y, Blaustein RO, Patten RD, Karas RH, Van Tol HH, Osborne TF, Shimano H, Liao R, Link MS, Galper JB. Parasympathetic response in chick myocytes and mouse heart is controlled by SREBP. J Clin Invest 118: 259–271, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peleg S, Varon D, Ivanina T, Dessauer CW, Dascal N. G alpha i controls the gating of the G protein-activated K+ channel, GIRK. Neuron 33: 87–99, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perini R, Veicsteinas A. Heart rate variability and autonomic activity at rest and during exercise in various physiological conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol 90: 317–325, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaffinger PJ, Martin JM, Hunter DD, Nathanson NM, Hille B. GTP-binding proteins couple cardiac muscarinic receptors to a K channel. Nature 317: 536–538, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pruvot E, Thonet G, Vesin JM, van-Melle G, Seidl K, Schmidinger H, Brachmann J, Jung W, Hoffmann E, Tavernier R, Block M, Podczeck A, Fromer M. Heart rate dynamics at the onset of ventricular tachyarrhythmias as retrieved from implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 101: 2398–2404, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Hyperpolarization-activated cation currents: from molecules to physiological function. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 453–480, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudolph U, Finegold MJ, Rich SS, Harriman GR, Srinivasan Y, Brabet P, Boulay G, Bradley A, Birnbaumer L. Ulcerative colitis and adenocarcinoma of the colon in G alpha i2-deficient mice. Nat Genet 10: 143–150, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rudolph U, Spicher K, Birnbaumer L. Adenylyl cyclase inhibition and altered G protein subunit expression and ADP-ribosylation patterns in tissues and cells from Gi2 alpha−/−mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 3209–3214, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rusinova R, Mirshahi T, Logothetis DE. Specificity of Gβγ signaling to Kir3 channels depends on the helical domain of pertussis toxin-sensitive Gα subunits. J Biol Chem 282: 34019–34030, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sowell MO, Ye C, Ricupero DA, Hansen S, Quinn SJ, Vassilev PM, Mortensen RM. Targeted inactivation of αi2 or αi3 disrupts activation of the cardiac muscarinic K+ channel, IK+ACh, in intact cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 7921–7926, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spyer KM Annual review prize lecture. Central nervous mechanisms contributing to cardiovascular control. J Physiol 474: 1–19, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stauss HM Heart rate variability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R927–R931, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swoap SJ, Li C, Wess J, Parsons AD, Williams TD, Overton JM. Vagal tone dominates autonomic control of mouse heart rate at thermoneutrality. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1581–H1588, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thireau J, Zhang BL, Poisson D, Babuty D. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Exp Physiol 93: 83–94, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uechi M, Asai K, Osaka M, Smith A, Sato N, Wagner TE, Ishikawa Y, Hayakawa H, Vatner DE, Shannon RP, Homcy CJ, Vatner SF. Depressed heart rate variability and arterial baroreflex in conscious transgenic mice with overexpression of cardiac Gsalpha. Circ Res 82: 416–423, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valenzuela D, Han X, Mende U, Fankhauser C, Mashimo H, Huang P, Pfeffer J, Neer EJ, Clapham DE. Gαo is necessary for muscarinic regulation of Ca2+ channels in mouse heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1727–1732, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Welzig CM, Shin DG, Park HJ, Kim YJ, Saul JP, Galper JB. Lipid lowering by pravastatin increases parasympathetic modulation of heart rate: Galpha(i2), a possible molecular marker for parasympathetic responsiveness. Circulation 108: 2743–2746, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type-specific functions. Physiol Rev 85: 1159–1204, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wickman K, Nemec J, Gendler SJ, Clapham DE. Abnormal heart rate regulation in GIRK4 knockout mice. Neuron 20: 103–114, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamada M, Inanobe A, Kurachi Y. G protein regulation of potassium ion channels. Pharmacol Rev 50: 723–757, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu M, Gach AA, Liu G, Xu X, Lim CC, Zhang JX, Mao L, Chuprun K, Koch WJ, Liao R, Koren G, Blaxall BC, Mende U. Enhanced calcium cycling and contractile function in transgenic hearts expressing constitutively active Gαo* protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1335–H1347, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]