Abstract

Knowledge of the natural roles of cellular prion protein (PrPC) is essential to an understanding of the molecular basis of prion pathologies. This GPI-anchored protein has been described in synaptic contacts, and loss of its synaptic function in complex systems may contribute to the synaptic loss and neuronal degeneration observed in prionopathy. In addition, Prnp knockout mice show enhanced susceptibility to several excitotoxic insults, GABAA receptor-mediated fast inhibition was weakened, LTP was modified and cellular stress increased. Although little is known about how PrPC exerts its function at the synapse or the downstream events leading to PrPC-mediated neuroprotection against excitotoxic insults, PrPC has recently been reported to interact with two glutamate receptor subunits (NR2D and GluR6/7). In both cases the presence of PrPC blocks the neurotoxicity induced by NMDA and Kainate respectively. Furthermore, signals for seizure and neuronal cell death in response to Kainate in Prnp knockout mouse are associated with JNK3 activity, through enhancing the interaction of GluR6 with PSD-95. In combination with previous data, these results shed light on the molecular mechanisms behind the role of PrPC in excitotoxicity. Future experimental approaches are suggested and discussed.

Keywords: Glutamate Receptors, Synapse, excitotoxicity, neuroprotection, prion protein, prionopathy

The Cellular Prion Protein—The Quest for a Natural Function

The cellular prion protein is encoded by a single-copy gene (PRNP) that comprises two to three exons, with the open reading frame (ORF) lying in the third exon.1,2 The resulting protein is a glycosyl phosphatidyl inositol (GPI)-anchored cell-surface glycoprotein.3 PrPC is highly expressed in the adult central nervous system (CNS) by post-mitotic neurons and glial cells.4-7 Outside the CNS, elevated PrPC expression has been reported in different cell types, such as bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells, spermatogonia, or lymphocytes.8-11 Pioneer studies reported that cultured neurons lacking PrPC showed poor resistance to serum withdrawal,12 and especial sensitivity to oxidative stress stimuli.13 Thus, in order to determine the physiological functions of the protein, several cell lines lacking PrPC expression were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells by modifications restricted to the ORF or, alternatively, by deleting the ORF but also expanding flanking regions. Using the first mouse strains homozygous for the inactivated gene (such as Zürich I,14 or Edinburgh,15) researchers found that these were resistant to prion infection and showed normal development. In aging mice they detected certain peripheral nervous system degeneration, albeit without clear clinical symptoms.16 However, further detailed physiological studies reported that Prnp0/0 mice showed weak GABAA receptor-mediated fast inhibition, modified LTP and alterations in circadian activity and sleep rhythms.17-20 Mice carrying larger deletions overexpress Doopel (Dpl) but develop normally at perinatal stages. However, they exhibit severe ataxia and Purkinje cell loss at young-adult stages, a phenotype that can be overcome by the inclusion of a single copy of Prnp.21 In recent years, several mice lacking particular regions of PrPC have been developed, which unveiled specific functional regions of PrPC relevant to fast degeneration of cerebellar cells. For a review see references. 22 and 23. However, here we focus on some recently determined functions of PrPC, especially related to its putative participation in synaptic plasticity and in the prevention of excitotoxicity. Although this review focuses on neurons, we should not forget that PrPC expressed in astrocytes may have a functional influence in vivo.24

Histochemical analysis revealed that PrPC is located in axons, for example in hippocampal mossy fibers.25 However, electron microscopy analysis identified it in synaptic contacts (at both pre- and post-synaptic level).26 In addition, loss of PrPC function at synapses following deletion of the Prnp gene triggers several neural dysfunctions (see above). From a neurological point of view, prionopathies were characterized as synaptic diseases.27 Indeed, in CJD, an abnormal form of PrPC accumulates at synaptic terminals,28 and physiological PrPC function is lost. Several authors consider this as showing simply that physiological processes in prionopathies such as CJD are the result of the increased pathological effects of the misfolded protein PrPSC together with the loss of natural functions of the decreased PrPC. However, additional knowledge is needed to ascertain whether this scenario is as simple as hypothesized. We cannot rule out factors identified in recent studies that may condition the evolution of the illness: for example, the emerging role of the oligomeric or soluble forms of PrPSC,29,30 the Prnp and non-Prnp genetic influence,31changes in gene expression in affected individuals,32 new data on the intracellular trafficking of the protein and conformational studies,33,34 as well as the crosstalk of prionopathies with other diseases such as AD.35,36 We need to integrate this emerging knowledge from animal models with clinical data from patients.

PrPC and “Partners”—A Scenario with Many Actors at the Synapse

Epilepsy

The first physiological descriptions mainly focused on stress and the sensitive phenotype of mutant mice.37 Later studies indicate that Prnp knockout mice showed cognitive deficits, depressive-like behavior, and anxiety-related responses.38-40 Taken together, these results point to modified or unbalanced neurotransmission. Indeed, a pioneer study by Walz et al. demonstrated that mice devoid of PrPC were more sensitive to kainate, pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) and pilocarpine injections.41 This result was further corroborated by other authors.18,42-45 However, a recent study using cultured slices containing zero-magnesium, bicuculline, and PTZ as convulsants showed that higher concentrations of convulsants were necessary to generate spontaneous epileptiform activity in Prnpo/o slices in contrast to wild-type mice.46 Moreover, we cannot rule out the possibility that other factors (e.g., genetic background, age at analysis, technical conditions) may affect the enhanced epileptic phenotype displayed for the mutant mice. These factors may also correlate with neuroanatomical modifications in the hippocampus (e.g., mossy fiber reorganization in the dentate gyrus). (For a review, see ref. 47).

But we should be cautious in extrapolating these results to CJD patients displaying different degrees of seizures, ranging from episodes of periodic lateralized epileptiform complexes (PLEDs), general status epilepticus or epilepsia partialis continua (EPC).48-50 Readers are referred to a recent study on CJD and status epilepticus.51

Role of PrPC in Long-term Potentiation: a challenging puzzle

Results from electrophysiological studies in Prnp knockout mice, which have been extensively used to examine PrPC-mediated synaptic plasticity, have also brought controversy to the field. Several authors established that PrPC participates in LTP in hippocampal slices,17,19,52 and in vivo in anesthetized mice.53,54 Collinge et al. observed that hippocampal slices from Prnp knockout mice have weakened GABAA receptor-mediated fast inhibition and impaired long-term potentiation.17 A lower threshold for generating LTP in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, in Prnp knockout mice compared with wild-type animals, was also observed by Maglio et al.19 In addition, Curtis et al. found a reduction in the level of post-tetanic potentiation and LTP in the CA1 region of aged Prnp knockout mice but not in young animals.53 Later, the same authors reported similar results with aged Prnp knockout animals (9 mo old).52In agreement with this, we also observed enhanced synaptic facilitation in paired-pulse experiments and hippocampal LTP in living, behaving mutant mice.54 However, Lledó et al. found no differences in LTP between control and Prnp knockout mice in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, although the same laboratory found a range of synaptic responses correlated with the level of PrPC expression.55,56 In addition, most authors attribute differences in electrophysiological recording in slice experiments between several reports vs. in vivo analysis to differences in experimental conditions.

Can PrPC Partners be Responsible for the Differences in Observations of PrPC Roles in Neurotransmission?

There is controversy as to whether PrPC participates in synaptic transmission. In fact two lines of inquiry are being followed in an attempt to resolve the issue: i) the interaction of PrPC with extracellular elements (e.g., ions, molecules or contra-receptors) or ii) its interactions with the synaptic molecules or members of the vesicle transport machinery. In the last few years an emerging third line of analysis appears to indicate that PrPC may modulate neurotransmission by interacting with neurotransmitter receptors.

Extracellular partners

PrPC, which binds copper through its octarepeat domain, has been implicated in the maintenance of the redox stage at pre-synaptic level through the regulation of calcium flux.57,58 A second example of extracellular partners can be seen by analyzing the binding of PrPC to adhesion molecules, such as NCAM,59,60 or Laminin.61 Binding of Laminin to PrPC modulates neuronal plasticity and memory by acting through Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors.61

The third and probably the most exciting example, found in 2009 in a study by Strittmatter’s group indicates that PrPC mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by Aβ oligomers (ADDLs).62 Indeed, in the same study a removal function of free ADDLs was suggested for PrPC, although further studies by the same group failed to find a direct effect of PrPC expression on Aβ deposition in mouse models.63 However, the results of the same study reinforce the notion that interaction between PrPC and ADDLs is required for suppression of synaptic plasticity in hippocampal slices.63In fact, a recent study reported that ADDLs increased the presence of PrPC at the cell membrane and that to some extent the effects of intracellular ADDLs are mediated by PrPC.64 This contrasts with those reported by Aguzzi’s group, who found no change in the impairment of hippocampal synaptic plasticity in a transgenic model of AD after Prnp deletion or overexpression, suggesting that PrPC has a weak role as mediator of Aβ toxicity.35 Indeed, no changes in PrPC protein levels were detected in AD patients,65 although fibrillar forms of PrPC and Aβ are detected in amyloid plaques,66 and fibrillar forms of PrPC and Aβ interact in AD brains.67

We conclude that the pathophysiological relevance of the PrPC/Aβ interaction remains to be established.

Intracellular partners

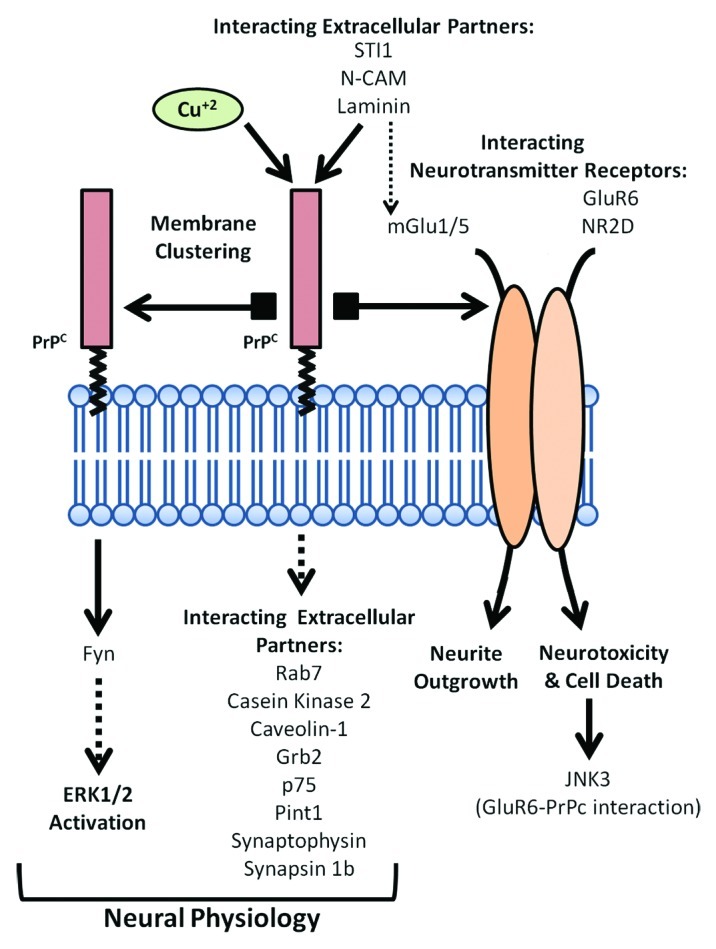

PrPC may participate in neurotransmitter release, as reported at the neuromuscular junction, by interacting with synaptic associated proteins.68 Indeed, Synapsin Ib, and Synaptophysin (among others) have been reported to interact with PrPC. For a review see reference 69. In fact, misfolded PrPC has been implicated in SNARE dysfunction in vitro (see below), but surprisingly, not in vivo.70 Again parallels are found between bench experiments and CJD patients, since defective synaptic machinery in infected brains (mainly (SNAP-25), syntaxin-1, synapsin-1) was demonstrated several years ago.27,71 However, whether these changes affect the symptoms and the evolution of the illness requires additional study. In this regard, recent approaches analyzing gene expression changes in different rodent models lacking PrPC,18,72 and the comparison with CJD patients and prion infected animals73-76 could be of interest in order to harmonize data. On the other hand, a large group of PrPC-binding proteins locate into vesicles or caveolae-like domains such as Casein Kinase 2, Caveolin-1, Grb-2, p75 and Pint-1. For a review see reference 77. Recently, an interaction between PrPC and Rab7 has also been shown, and silencing of Rab7a promotes PrPC accumulation in Rab9-positive endosomal compartments,78 which implicates PrPC in vesicular trafficking. The potential effects of these interactions in lipid rafts and associated vesicles on vesicular trafficking, cellular signaling and neuroprotection warrants further study. A scheme summarizing proposed functional interactions for PrPC at the cell membrane is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scheme of the proposed functional roles for PrPC at the cell membrane as intracellular transducer of extracellular signals. PrPC mediates self-aggregation, interaction with intracellular and extracellular partners or with glutamatergic receptor subunits, leading to a broad range of molecular mechanisms regulating neuronal cell physiology.

Emerging Roles of PrPC—Modulating Neurotransmitter Receptors in Intracellular Processes in Excitotoxicity

The signaling mechanism that triggers PrPC remains elusive. After antibody recruitment of PrPC at the plasma membrane, Fyn,60,79-81 and ERK/CREB signaling activation has been described.82,83 However, PrPC aggregation by specific antibodies also leads to cell death by increased ROS in vitro and in vivo,84,85 which raises the question of whether this is the natural mechanism of PrPC-mediated signaling. For a review see reference 47. Although it is assumed that PrPC transduces neuroprotective signals,86 we should not consider it as a generic neuroprotective molecule per se.87 In fact, Steele et al. showed that deletion of Prnp in several transgenic models of neurodegenerative disease (PD, HD, tauopathy) did not contribute to the development of the disease, suggesting a context-dependent neuroprotective function for PrPC.88 As indicated above, the enhanced susceptibility of Prnp knockout to glutamate excitotoxicity has been reported extensively.41,42,89 In addition, neuronal cell death in the hippocampus of Prnp knockout mice has been described in response to glutamate toxicity when compared with control animals.42,45 In addition, Koshravani et al. recently measured NMDAR-mediated currents and mEPSCs recorded from Prnp knockout hippocampal slices and showed events with significantly larger amplitudes than those observed in control animals.45 Furthermore, NMDAR-mediated mEPSCs of Prnp knockout slices showed significantly longer decay times.45

However, little is known about the molecular mechanisms activated by the lack of PrPC in the presence of excitotoxic insults. When compared with control mice, we observed increased phospho-JNK reactivity in the pyramidal cells of the hippocampal CA1 and enhanced sensitivity to seizures and hippocampal cell death.42 Further, we investigated the signaling pathways activated after KA treatment in the Prnp knockout mice.44

PrPC, Glutamate Receptors and JNK3 Activity

JNK has been implicated in several neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and PD,90,91 and it plays a crucial role in epilepsy and stroke.92,93 Of the three isoforms of JNK (JNK1, 2 and 3), JNK3 was a good candidate to be a key molecule in the PrPC-dependent transmission of the excitotoxicity provoked by glutamate: 1) JNK3 is predominantly expressed in the CNS;94 2) Jnk3 knockout provides neuroprotection against various injuries,95,96 and most interestingly, resistance to epileptic seizures and hippocampal cell death;92 and 3) the JNK3 apoptotic signaling pathway is reported to be induced by KA and ischemia.92,97 With these results in mind, we recently generated a double knockout mutant Prnp/Jnk3, which was insensitive to seizure and hippocampal cell death in response to KA injections.44 This observation was corroborated in organotypic slices using pharmacological JNK inhibitors.

On the other hand, several authors reported that assembly of the GluR6-PSD-95-MLK3 trimer induced by KA and ischemia is essential for the activation of JNK3.98,99 JNK3 phosphorylation and activation induces phosphorylation of c-Jun, which is part of the AP-1 complex. The JNK-c-Jun-AP-1 pathway plays a key role in cell death and apoptosis regulation following several insults. Interestingly, GluR6, JNK3 and c-Jun Ser63/73AA knockout mice are resistant to KA-induced seizures.92,100,101 We observed that PrPC favors the interaction between GluR6 and PSD-95 in the presence of KA, and that PrPC interacts with GluR6-PSD-95 in the PSD fraction from hippocampus.44

In this regard, interaction between PrPC and NR2D was also observed by Khosravani et al.45 Similarly to our observations, the presence of PrPC silenced NR2D and reduced excitotoxic lesions in the presence of NMDA. In addition, Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1/5) also associate with PrPC. Furthermore, Group I mGluRs are involved in the transduction of cellular signals triggered by PrPC-Laminin interaction.61

PrPC and Excitotoxicity—New Questions

As in any other scientific field, a particular discovery may raise more than a hundred challenging questions. Current data indicate that PrPC contributes to a general neuroprotective mechanism in response to excitotoxic insults through interaction with glutaminergic receptors. However, we first need to establish whether this neuroprotective response of PrPC to increased glutamate is pleiotropic or specific to a particular subset of glutamate receptors. In order to determine whether PrPC inhibits the glutamate-mediated post-synaptic hyperexcitation of neural cells in a specific manner, further interactome experiments from post-synaptic density-enriched fractions should be performed. In this regard Khosravani et al. demonstrated some degree of specificity between PrPC and NMDAR subunits, since they did not detect NR2B in their PrPC immunoprecipitates.45 In addition, it would also be interesting to study the kinetics of the interaction between PrPC and its receptor partners in order to establish the role of PrPC under basal conditions. To date, several interactome studies have been performed in neuroblastoma cell lines overexpressing PrPC or in transgenic myc-PrP mice.78,102,103 Although the list of PrPC interacting partners is increasing, the main problem so far resides in our lack of knowledge of the functional relevance of these interactions.104 We can find some exceptions such as the interaction of PrPC with the plasma membrane stress-inducible protein 1(STI1) that has clearly been shown to transduce extracellular signals to the intracellular environment of PrPC expressing cells in an alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-dependent manner.105-107

Another open question in this field is how PrPC inhibits GluR6 and NR2D. Khosravani and Steele hypothesized, for the NR2D-PrPC interaction, that PrPC could block receptor agonist binding, stabilize the closed state of the channel, or act indirectly by interfering with signaling pathways affecting glutamate receptor functions by individual regulation of its subunits.45,108 Mapping the interaction regions between PrPC and GluR6 and NR2D may help to discern the molecular mechanisms by which PrPC silences both receptor subunits. In addition, since GPI seems to play an essential role in the physiological and pathological functionality of PrPC 109,110 the PrPC-GPI domain may help to direct the interaction between PrPC and glutamate receptor subunits. In this regard, interaction and neurotoxic experiments with the anchorless Prnp transgenic mice (GPI−/−), which produces a PrPC form that is mainly released in the culture media in a fully glycosylated, soluble form, could be a good approach to this issue.

Final Remarks

Despite efforts to discern the physiological role of PrPC, understanding its biological function presents several challenges. There are a large number of PrPC-partners, most of which still need to be associated with a biological function. In addition, the pleiotropic phenotypes of the various Prnp knockout mice hinder the study of basic biological PrPC-dependent functions. Furthermore, our lack of knowledge of the PrPC-dependent signaling pathways, both in physiological and in pathological conditions, makes it difficult to integrate the biological information gathered from membrane (receptor) levels to gene expression. The development of new experimental tools such as double JNK3-glutamatergic subunit knockout mice, together with the discovery of new potential PrPC partners involved in neurotransmission, and the study of such interactions using interdisciplinary approaches (merging data from proteomic, cell signaling and neuropathological experiments) may help to elucidate the neuroprotective role of PrPC in response to excitotoxic insults.

Finally, although a striking degree of conservation between the Prnp mammalian sequences has been observed, to date there are no studies linking PrPC-mediated excitotoxicity at the evolutionary level. However, the contribution of recent articles on the structural differences between different species may bring some light on how these changes may be crucial for the PrPC physiology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of our lab for their contributions during these years and Prof. A. Aguzzi for reagents, and fruitful discussions on the topic along these years. This research was supported by the FP7-PRIORITY, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (BFU2009–10848), the Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR2009–366) and the Instituto Salud Carlos III.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- CJD

Creutzfeldt Jakob disease

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- PD

Parkinson disease

- HD

Huntington disease

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid

- GABA

gamma-Aminobutyric acid

- NR2

NMDA receptor subunit 2

- GluR

Glutamate Receptor

- PSD-95

post-synaptic density protein 95

- LTP

Long term potentiation

- OR

Octorepeat region

- CNS

Central Nervous System

- GPI

glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/19639

References

- 1.Basler K, Oesch B, Scott M, Westaway D, Wälchli M, Groth DF, et al. Scrapie and cellular PrP isoforms are encoded by the same chromosomal gene. Cell. 1986;46:417–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabriel JM, Oesch B, Kretzschmar H, Scott M, Prusiner SB. Molecular cloning of a candidate chicken prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9097–101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prusiner SB. Prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13363–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DR, Besinger A, Herms JW, Kretzschmar HA. Microglial expression of the prion protein. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1425–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moser M, Colello RJ, Pott U, Oesch B. Developmental expression of the prion protein gene in glial cells. Neuron. 1995;14:509–17. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford MJ, Burton LJ, Morris RJ, Hall SM. Selective expression of prion protein in peripheral tissues of the adult mouse. Neuroscience. 2002;113:177–92. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radovanovic I, Braun N, Giger OT, Mertz K, Miele G, Prinz M, et al. Truncated prion protein and Doppel are myelinotoxic in the absence of oligodendrocytic PrPC. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4879–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0328-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu T, Zwingman T, Li R, Pan T, Wong BS, Petersen RB, et al. Differential expression of cellular prion protein in mouse brain as detected with multiple anti-PrP monoclonal antibodies. Brain Res. 2001;896:118–29. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tichopad A, Pfaffl MW, Didier A. Tissue-specific expression pattern of bovine prion gene: quantification using real-time RT-PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 2003;17:5–10. doi: 10.1016/S0890-8508(02)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujisawa M, Kanai Y, Nam SY, Maeda S, Nakamuta N, Kano K, et al. Expression of Prnp mRNA (prion protein gene) in mouse spermatogenic cells. J Reprod Dev. 2004;50:565–70. doi: 10.1262/jrd.50.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang CC, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Lodish HF. Prion protein is expressed on long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells and is important for their self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2184–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510577103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwahara C, Takeuchi AM, Nishimura T, Haraguchi K, Kubosaki A, Matsumoto Y, et al. Prions prevent neuronal cell-line death. Nature. 1999;400:225–6. doi: 10.1038/22241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong BS, Liu T, Li R, Pan T, Petersen RB, Smith MA, et al. Increased levels of oxidative stress markers detected in the brains of mice devoid of prion protein. J Neurochem. 2001;76:565–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Büeler H, Fischer M, Lang Y, Bluethmann H, Lipp HP, DeArmond SJ, et al. Normal development and behaviour of mice lacking the neuronal cell-surface PrP protein. Nature. 1992;356:577–82. doi: 10.1038/356577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manson JC, Clarke AR, Hooper ML, Aitchison L, McConnell I, Hope J. 129/Ola mice carrying a null mutation in PrP that abolishes mRNA production are developmentally normal. Mol Neurobiol. 1994;8:121–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02780662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bremer J, Baumann F, Tiberi C, Wessig C, Fischer H, Schwarz P, et al. Axonal prion protein is required for peripheral myelin maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:310–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collinge J, Whittington MA, Sidle KC, Smith CJ, Palmer MS, Clarke AR, et al. Prion protein is necessary for normal synaptic function. Nature. 1994;370:295–7. doi: 10.1038/370295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rangel A, Madroñal N, Gruart A, Gavín R, Llorens F, Sumoy L, et al. Regulation of GABA(A) and glutamate receptor expression, synaptic facilitation and long-term potentiation in the hippocampus of prion mutant mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maglio LE, Perez MF, Martins VR, Brentani RR, Ramirez OA. Hippocampal synaptic plasticity in mice devoid of cellular prion protein. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;131:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobler I, Gaus SE, Deboer T, Achermann P, Fischer M, Rülicke T, et al. Altered circadian activity rhythms and sleep in mice devoid of prion protein. Nature. 1996;380:639–42. doi: 10.1038/380639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heitz S, Grant NJ, Leschiera R, Haeberlé AM, Demais V, Bombarde G, et al. Autophagy and cell death of Purkinje cells overexpressing Doppel in Ngsk Prnp-deficient mice. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:119–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolas O, Gavín R, del Río JA. New insights into cellular prion protein (PrPc) functions: the “ying and yang” of a relevant protein. Brain Res Rev. 2009;61:170–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steele AD, Lindquist S, Aguzzi A. The prion protein knockout mouse: a phenotype under challenge. Prion. 2007;1:83–93. doi: 10.4161/pri.1.2.4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathmajeyan MS, Patel SA, Carroll JA, Seib T, Striebel JF, Bridges RJ, et al. Increased excitatory amino acid transport into murine prion protein knockout astrocytes cultured in vitro. Glia. 2011;59:1684–94. doi: 10.1002/glia.21215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailly Y, Haeberlé AM, Blanquet-Grossard F, Chasserot-Golaz S, Grant N, Schulze T, et al. Prion protein (PrPc) immunocytochemistry and expression of the green fluorescent protein reporter gene under control of the bovine PrP gene promoter in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2004;473:244–69. doi: 10.1002/cne.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fournier JG. Cellular prion protein electron microscopy: attempts/limits and clues to a synaptic trait. Implications in neurodegeneration process. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;332:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0565-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrer I, Rivera R, Blanco R, Martí E. Expression of proteins linked to exocytosis and neurotransmission in patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:92–100. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamoto T, Shin RW, Doh-ura K, Tomokane N, Miyazono M, Muramoto T, et al. Abnormal isoform of prion proteins accumulates in the synaptic structures of the central nervous system in patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:1285–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou WQ, Zhou X, Yuan J, Xiao X. Insoluble cellular prion protein and its association with prion and Alzheimer diseases. Prion. 2011;5:172–8. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.3.16894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simoneau S, Rezaei H, Salès N, Kaiser-Schulz G, Lefebvre-Roque M, Vidal C, et al. In vitro and in vivo neurotoxicity of prion protein oligomers. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e125. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloyd S, Mead S, Collinge J. Genetics of prion disease. Top Curr Chem. 2011;305:1–22. doi: 10.1007/128_2011_157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang W, Windl O, Westner IM, Neumann M, Zerr I, Lederer RM, et al. Cerebral gene expression profiles in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:242–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porto-Carreiro I, Février B, Paquet S, Vilette D, Raposo G. Prions and exosomes: from PrPc trafficking to PrPsc propagation. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis V, Hooper NM. The role of lipid rafts in prion protein biology. Front Biosci. 2011;16:151–68. doi: 10.2741/3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calella AM, Farinelli M, Nuvolone M, Mirante O, Moos R, Falsig J, et al. Prion protein and Abeta-related synaptic toxicity impairment. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:306–14. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Checler F, Vincent B. Alzheimer’s and prion diseases: distinct pathologies, common proteolytic denominators. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:616–20. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown DR, Nicholas RS, Canevari L. Lack of prion protein expression results in a neuronal phenotype sensitive to stress. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:211–24. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Criado JR, Sánchez-Alavez M, Conti B, Giacchino JL, Wills DN, Henriksen SJ, et al. Mice devoid of prion protein have cognitive deficits that are rescued by reconstitution of PrP in neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:255–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gadotti VM, Bonfield SP, Zamponi GW. Depressive-like behaviour of mice lacking cellular prion protein. Behav Brain Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xikota JC, Rial D, Ruthes D, Pereira R, Figueiredo CP, Prediger RD, et al. Mild cognitive deficits associated to neocortical microgyria in mice with genetic deletion of cellular prion protein. Brain Res. 2008;1241:148–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walz R, Amaral OB, Rockenbach IC, Roesler R, Izquierdo I, Cavalheiro EA, et al. Increased sensitivity to seizures in mice lacking cellular prion protein. Epilepsia. 1999;40:1679–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rangel A, Burgaya F, Gavín R, Soriano E, Aguzzi A, Del Río JA. Enhanced susceptibility of Prnp-deficient mice to kainate-induced seizures, neuronal apoptosis, and death: Role of AMPA/kainate receptors. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2741–55. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walz R, Castro RM, Velasco TR, Carlotti CG, Jr., Sakamoto AC, Brentani RR, et al. Cellular prion protein: implications in seizures and epilepsy. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2002;22:249–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1020711700048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carulla P, Bribián A, Rangel A, Gavín R, Ferrer I, Caelles C, et al. Neuroprotective role of PrPC against kainate-induced epileptic seizures and cell death depends on the modulation of JNK3 activation by GluR6/7-PSD-95 binding. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3041–54. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khosravani H, Zhang Y, Tsutsui S, Hameed S, Altier C, Hamid J, et al. Prion protein attenuates excitotoxicity by inhibiting NMDA receptors. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:551–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ratté S, Vreugdenhil M, Boult JK, Patel A, Asante EA, Collinge J, et al. Threshold for epileptiform activity is elevated in prion knockout mice. Neuroscience. 2011;179:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MA, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:673–728. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Au WJ, Gabor AJ, Vijayan N, Markand ON. Periodic lateralized epileptiform complexes (PLEDs) in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 1980;30:611–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.6.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neufeld MY, Talianski-Aronov A, Soffer D, Korczyn AD. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Seizure. 2003;12:403–5. doi: 10.1016/S1059-1311(02)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee K, Haight E, Olejniczak P. Epilepsia partialis continua in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102:398–402. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.102006398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Espinosa PS, Bensalem-Owen MK, Fee DB. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting as nonconvulsive status epilepticus case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:537–40. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maglio LE, Martins VR, Izquierdo I, Ramirez OA. Role of cellular prion protein on LTP expression in aged mice. Brain Res. 2006;1097:11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curtis J, Errington M, Bliss T, Voss K, MacLeod N. Age-dependent loss of PTP and LTP in the hippocampus of PrP-null mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0969-9961(03)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rangel EB, Gonzalez AM, Linhares MM, Aguiar WF, Nogueira M, Ximenes S, et al. Asynchronous kidney allograft loss after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation: impact on pancreas allograft outcome at a single center. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1773–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lledo PM, Tremblay P, DeArmond SJ, Prusiner SB, Nicoll RA. Mice deficient for prion protein exhibit normal neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2403–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carleton A, Tremblay P, Vincent JD, Lledo PM. Dose-dependent, prion protein (PrP)-mediated facilitation of excitatory synaptic transmission in the mouse hippocampus. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:223–9. doi: 10.1007/s004240100523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walter ED, Stevens DJ, Spevacek AR, Visconte MP, Dei Rossi A, Millhauser GL. Copper binding extrinsic to the octarepeat region in the prion protein. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2009;10:529–35. doi: 10.2174/138920309789352056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vassallo N, Herms J. Cellular prion protein function in copper homeostasis and redox signalling at the synapse. J Neurochem. 2003;86:538–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Farina F, Botto L, Chinello C, Cunati D, Magni F, Masserini M, et al. Characterization of prion protein-enriched domains, isolated from rat cerebellar granule cells in culture. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1038–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santuccione A, Sytnyk V, Leshchyns’ka I, Schachner M. Prion protein recruits its neuronal receptor NCAM to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn and to enhance neurite outgrowth. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:341–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beraldo FH, Arantes CP, Santos TG, Machado CF, Roffe M, Hajj GN, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptors transduce signals for neurite outgrowth after binding of the prion protein to laminin γ1 chain. FASEB J. 2011;25:265–79. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-161653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laurén J, Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Gilbert JW, Strittmatter SM. Cellular prion protein mediates impairment of synaptic plasticity by amyloid-beta oligomers. Nature. 2009;457:1128–32. doi: 10.1038/nature07761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gimbel DA, Nygaard HB, Coffey EE, Gunther EC, Laurén J, Gimbel ZA, et al. Memory impairment in transgenic Alzheimer mice requires cellular prion protein. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6367–74. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0395-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caetano FA, Beraldo FH, Hajj GN, Guimaraes AL, Jürgensen S, Wasilewska-Sampaio AP, et al. Amyloid-beta oligomers increase the localization of prion protein at the cell surface. J Neurochem. 2011;117:538–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saijo E, Scheff SW, Telling GC. Unaltered prion protein expression in Alzheimer disease patients. Prion. 2011;5:109–16. doi: 10.4161/pri.5.2.16355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Takahashi RH, Tobiume M, Sato Y, Sata T, Gouras GK, Takahashi H. Accumulation of cellular prion protein within dystrophic neurites of amyloid plaques in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neuropathology. 2011;31:208–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2010.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou WQ, Xiao X, Yuan J, Puoti G, Fujioka H, Wang X, et al. Amyloid-beta42 interacts mainly with insoluble prion protein in the Alzheimer brain. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15095–105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.199356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Re L, Rossini F, Re F, Bordicchia M, Mercanti A, Fernandez OS, et al. Prion protein potentiates acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:62–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hetz C, Maundrell K, Soto C. Is loss of function of the prion protein the cause of prion disorders? Trends Mol Med. 2003;9:237–43. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asuni AA, Cunningham C, Vigneswaran P, Perry VH, O’Connor V. Unaltered SNARE complex formation in an in vivo model of prion disease. Brain Res. 2008;1233:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sisó S, Puig B, Varea R, Vidal E, Acín C, Prinz M, et al. Abnormal synaptic protein expression and cell death in murine scrapie. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:615–26. doi: 10.1007/s00401-001-0512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benvegnù S, Roncaglia P, Agostini F, Casalone C, Corona C, Gustincich S, et al. Developmental influence of the cellular prion protein on the gene expression profile in mouse hippocampus. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43:711–25. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00205.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Skinner PJ, Abbassi H, Chesebro B, Race RE, Reilly C, Haase AT. Gene expression alterations in brains of mice infected with three strains of scrapie. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tang Y, Xiang W, Terry L, Kretzschmar HA, Windl O. Transcriptional analysis implicates endoplasmic reticulum stress in bovine spongiform encephalopathy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sorensen G, Medina S, Parchaliuk D, Phillipson C, Robertson C, Booth SA. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of prion infection in mouse models reveals networks of responsive genes. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim HO, Snyder GP, Blazey TM, Race RE, Chesebro B, Skinner PJ. Prion disease induced alterations in gene expression in spleen and brain prior to clinical symptoms. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem. 2008;1:29–50. doi: 10.2147/aabc.s3411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee KS, Linden R, Prado MA, Brentani RR, Martins VR. Towards cellular receptors for prions. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:399–408. doi: 10.1002/rmv.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zafar S, von Ahsen N, Oellerich M, Zerr I, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Armstrong VW, et al. Proteomics approach to identify the interacting partners of cellular prion protein and characterization of Rab7a interaction in neuronal cells. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3123–35. doi: 10.1021/pr2001989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taylor DR, Hooper NM. The prion protein and lipid rafts. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:89–99. doi: 10.1080/09687860500449994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen S, Mangé A, Dong L, Lehmann S, Schachner M. Prion protein as trans-interacting partner for neurons is involved in neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:227–33. doi: 10.1016/S1044-7431(02)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mouillet-Richard S, Ermonval M, Chebassier C, Laplanche JL, Lehmann S, Launay JM, et al. Signal transduction through prion protein. Science. 2000;289:1925–8. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mouillet-Richard S, Schneider B, Pradines E, Pietri M, Ermonval M, Grassi J, et al. Cellular prion protein signaling in serotonergic neuronal cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1096:106–19. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pradines E, Loubet D, Schneider B, Launay JM, Kellermann O, Mouillet-Richard S. CREB-dependent gene regulation by prion protein: impact on MMP-9 and beta-dystroglycan. Cell Signal. 2008;20:2050–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schneider B, Mutel V, Pietri M, Ermonval M, Mouillet-Richard S, Kellermann O. NADPH oxidase and extracellular regulated kinases 1/2 are targets of prion protein signaling in neuronal and nonneuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13326–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235648100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Solforosi L, Criado JR, McGavern DB, Wirz S, Sánchez-Alavez M, Sugama S, et al. Cross-linking cellular prion protein triggers neuronal apoptosis in vivo. Science. 2004;303:1514–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1094273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J. 2002;21:3317–26. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Martins VR, Beraldo FH, Hajj GN, Lopes MH, Lee KS, Prado MM, et al. Prion protein: orchestrating neurotrophic activities. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2010;12:63–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steele AD, Zhou Z, Jackson WS, Zhu C, Auluck P, Moskowitz MA, et al. Context dependent neuroprotective properties of prion protein (PrP) Prion. 2009;3:240–9. doi: 10.4161/pri.3.4.10135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.McLennan NF, Brennan PM, McNeill A, Davies I, Fotheringham A, Rennison KA, et al. Prion protein accumulation and neuroprotection in hypoxic brain damage. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:227–35. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63291-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mehan S, Meena H, Sharma D, Sankhla R. JNK: a stress-activated protein kinase therapeutic strategies and involvement in Alzheimer’s and various neurodegenerative abnormalities. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43:376–90. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peng J, Andersen JK. The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in Parkinson’s disease. IUBMB Life. 2003;55:267–71. doi: 10.1080/1521654031000121666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang DD, Kuan CY, Whitmarsh AJ, Rincón M, Zheng TS, Davis RJ, et al. Absence of excitotoxicity-induced apoptosis in the hippocampus of mice lacking the Jnk3 gene. Nature. 1997;389:865–70. doi: 10.1038/39899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuan CY, Burke RE. Targeting the JNK signaling pathway for stroke and Parkinson’s diseases therapy. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:63–7. doi: 10.2174/1568007053005145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gupta S, Barrett T, Whitmarsh AJ, Cavanagh J, Sluss HK, Dérijard B, et al. Selective interaction of JNK protein kinase isoforms with transcription factors. EMBO J. 1996;15:2760–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Quigley HA, Cone FE, Gelman SE, Yang Z, Son JL, Oglesby EN, et al. Lack of neuroprotection against experimental glaucoma in c-Jun N-terminal kinase 3 knockout mice. Exp Eye Res. 2011;92:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brecht S, Kirchhof R, Chromik A, Willesen M, Nicolaus T, Raivich G, et al. Specific pathophysiological functions of JNK isoforms in the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:363–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Han D, Zhang QG, Yong-Liu, Li C, Zong YY, Yu CZ, et al. Co-activation of GABA receptors inhibits the JNK3 apoptotic pathway via the disassembly of the GluR6-PSD95-MLK3 signaling module in cerebral ischemic-reperfusion. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li C, Xu B, Wang WW, Yu XJ, Zhu J, Yu HM, et al. Coactivation of GABA receptors inhibits the JNK3 apoptotic pathway via disassembly of GluR6-PSD-95-MLK3 signaling module in KA-induced seizure. Epilepsia. 2010;51:391–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tian H, Zhang QG, Zhu GX, Pei DS, Guan QH, Zhang GY. Activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 3 is mediated by the GluR6.PSD-95.MLK3 signaling module following cerebral ischemia in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2005;1061:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mulle C, Sailer A, Pérez-Otaño I, Dickinson-Anson H, Castillo PE, Bureau I, et al. Altered synaptic physiology and reduced susceptibility to kainate-induced seizures in GluR6-deficient mice. Nature. 1998;392:601–5. doi: 10.1038/33408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Behrens A, Sibilia M, Wagner EF. Amino-terminal phosphorylation of c-Jun regulates stress-induced apoptosis and cellular proliferation. Nat Genet. 1999;21:326–9. doi: 10.1038/6854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Watts JC, Huo H, Bai Y, Ehsani S, Jeon AH, Shi T, et al. Interactome analyses identify ties of PrP and its mammalian paralogs to oligomannosidic N-glycans and endoplasmic reticulum-derived chaperones. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000608. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rutishauser D, Mertz KD, Moos R, Brunner E, Rülicke T, Calella AM, et al. The comprehensive native interactome of a fully functional tagged prion protein. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Spielhaupter C, Schätzl HM. PrPC directly interacts with proteins involved in signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44604–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zanata SM, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Hajj GN, Chiarini LB, Nomizo R, et al. Stress-inducible protein 1 is a cell surface ligand for cellular prion that triggers neuroprotection. EMBO J. 2002;21:3307–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Beraldo FH, Arantes CP, Santos TG, Queiroz NG, Young K, Rylett RJ, et al. Role of alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in calcium signaling induced by prion protein interaction with stress-inducible protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36542–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Roffé M, Beraldo FH, Bester R, Nunziante M, Bach C, Mancini G, et al. Prion protein interaction with stress-inducible protein 1 enhances neuronal protein synthesis via mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13147–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000784107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Steele AD. All quiet on the neuronal front: NMDA receptor inhibition by prion protein. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:407–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baumann F, Pahnke J, Radovanovic I, Rülicke T, Bremer J, Tolnay M, et al. Functionally relevant domains of the prion protein identified in vivo. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chesebro B, Race B, Meade-White K, Lacasse R, Race R, Klingeborn M, et al. Fatal transmissible amyloid encephalopathy: a new type of prion disease associated with lack of prion protein membrane anchoring. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000800. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]