How might a cell modulate the signals it receives from other cells and from the environment, so that it would not get too wound up or even signaled to death? It uses negative feedback regulation, as any sensible machinery would. Given that two very basic ways of signaling are to raise the free Ca2+ concentration inside the cell ([Ca2+]i) and to alter the electrical potential across the cell membrane, it is no wonder that the large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-dependent K+ (MaxiK) channels, which are negative feedback regulators for these signaling processes, are so prevalent in our nerves, muscles, secretory glands, and other eukaryotes, including protozoa (1). In this issue, Meera et al. (21) give us new insight into the molecular mechanisms through which the MaxiK channels respond to Ca2+ and membrane potential and thereby enhance our understanding of the control of electrical signaling.

How do MaxiK channels exert negative feedback regulation and modulate the electrical signals and/or the Ca2+ concentration? Electrical signals are excitatory if they tend to make the membrane potential (the electrical potential inside the cell minus the electrical potential outside the cell, typically at −60 mV when the cell is at rest) more positive (i.e., if they cause depolarization), because they increase the likelihood that the cell will fire an action potential that would bring the membrane potential close to the Na+ equilibrium potential (typically at +50 mV, because of the much higher Na+ concentration outside the cell). Depolarization could cause activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels and hence Ca2+ influx (1). Elevating the cytosolic Ca2+ levels could lead to the release of transmitters or hormones, activation of protein kinases, and/or regulation of gene expression. MaxiK channels provide negative feedback because these channels are activated by depolarization and/or elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration; an increase of K+ conductance because of MaxiK channel activation would bring the membrane potential closer to the K+ equilibrium potential (typically at −90 mV, because of the much higher K+ concentration inside the cell), thereby making it harder to depolarize the membrane or to activate the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.

Since the first discovery of K+ channels that are sensitive to cytosolic Ca2+ by Meech in 1974 (2), two major classes of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels have been found: those that are also voltage-dependent (e.g., MaxiK) and those that are not (e.g., Ca2+-dependent K+ channels with small conductance or intermediate conductance) (1). The gene encoding the MaxiK α subunit (the subunit that probably lines the channel pore) was first identified in the fruit fly Drosophila melanosgaster; because flies mutant for this gene can barely fly at room temperature and become even more uncoordinated when they are warmed up, this gene is named slowpoke (slo) (3). Under ether anesthesia, slowpoke mutants shake their legs (3), and thus resemble Shaker mutants. Consistent with this phenotypic similarity, the voltage-dependent K+ channels encoded by Shaker and the voltage- and Ca2+-dependent K+ channels encoded by slowpoke are both found in the motor nerves that innervate the muscle (4, 5). The behavioral abnormalities exhibited by flies mutant for Shaker or slowpoke indicate that these different K+ channels serve similar but not redundant functions. Besides modulation of neuronal excitability, MaxiK channels are known to regulate arterial tone and hence the blood pressure (6), control gastrointestinal motility (7), and modulate uterine contractility (8).

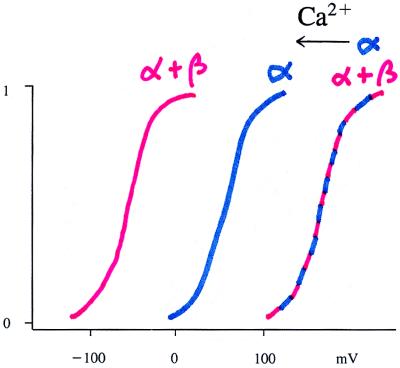

How do voltage and Ca2+ regulate MaxiK channels? At any given Ca2+ concentration, MaxiK channel activities are dependent on voltage in the same way as voltage-dependent K+ channels (i.e., the rate of channel opening increases and the rate of channel closing decreases with depolarization); increasing the Ca2+ concentration results in a left shift of the voltage dependence curve, so that at a given voltage the channels are more active at higher Ca2+ concentrations (9, 10) (Fig. 1). The Ca2+-dependence of MaxiK channels can be further regulated by the presence or absence of β subunits. These β subunits are found in MaxiK channels from trachea, arota, and probably gastrointestinal and uterine smooth muscles (11–13). In contrast, the brain expresses high levels of the MaxiK α subunits but low or undetectable levels of the β subunit (14). The way the β subunits regulate the Ca2+ dependence of MaxiK channels is to cause a left shift of the voltage dependence curve by as much as 95 mV when the Ca2+ concentration is significantly above the resting level (Fig. 1): At [Ca2+]i < 100 nM, the activities of MaxiK channels with or without β subunits are voltage-dependent but Ca2+-independent. At higher Ca2+ concentrations, the MaxiK channels that contain β subunits are far more active (15). As a consequence, a physiological increase of [Ca2+]i at the resting membrane potential such as a Ca2+ spark, a local [Ca2+]i increase because of spontaneous Ca2+ release from the internal store (16), may be sufficient to activate the smooth muscle MaxiK channels that contain β subunits, whereas a concurrent depolarization and elevation of Ca2+ concentration may be necessary to activate the neuronal MaxiK channels that lack β subunits. Thus the functional properties of MaxiK channels can be tailored for the specific physiological requirements of a cell not only by controlling the expression of different splice variants of the α subunit (17, 18) but also by regulating the β subunit expression (11–14).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the voltage-dependence curve of the MaxiK channel. The channel open probability rises from 0 to 1 with depolarization. The rightmost curve represents channels with or without β subunits at the resting [Ca2+]i. Raising the Ca2+ concentration to a few μM causes a left shift. The shift is exaggerated for channels that contain the β subunits (red) as compared with channels that lack β subunits (blue).

What are the molecular machineries that mediate voltage and Ca2+ regulation of MaxiK channels? The MaxiK channel α subunits belong to the same superfamily as do voltage-dependent K+ channel α subunits (17, 18). It therefore seems likely that the voltage dependence of MaxiK channels is at least in part mediated by the basic residue-studded S4 segment which, as an intrinsic voltage sensor, may be propelled by depolarization and move halfway across the membrane (19), thereby causing further conformation changes that lead to channel opening. Compared with the voltage-dependent K+ channel α subunits, which contain six transmembrane segments (S1-S6), the MaxiK channel α subunits have a much larger C-terminal region, which includes four additional segments (S7-S10) that contain predominantly hydrophobic residues. The “tail” domain that encompasses the S9 and S10 segments can be expressed separately from the rest of the α subunit (the “core”) that contains the voltage sensor and the pore-lining structures, and still confer Ca2+ sensitivity to the channel formed by the split α subunits (20). The Ca2+ dependence of the MaxiK channel is affected not only by the tail domain of the α subunit but also by the β subunit, which contains two transmembrane segments (11–15).

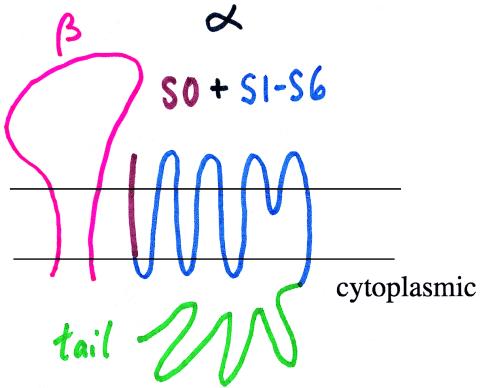

How might these molecular machineries interact with one another, so as to allow the MaxiK channel to display different voltage dependence at different Ca2+ concentrations in a manner that depends on the presence or absence of the β subunit? Meera, Wallner, Song, and Toro (21) address this question in this issue of the Proceedings by deciphering the interactions between the tail and the core, and between the β subunit and the α subunit. Their studies indicate that the MaxiK channel α subunit has an additional transmembrane segment (S0) at the N terminus. The S0 segment is followed by transmembrane segments S1-S6 that are homologous to the S1-S6 segments of voltage-dependent K+ channels, and a large cytoplasmic C-terminal domain including S7-S10 (Fig. 2). Moreover, the tail expressed in one Xenopus oocyte and the core expressed in another oocyte can work together to reconstitute a voltage- and Ca2+-dependent K+ channel, if a membrane patch from the oocyte expressing the core is crammed into the oocyte expressing the tail (21). Thus, not only is covalent linkage between the core and the tail not necessary for channel function, these two domains can be synthesized and folded independently, and they still will associate with each other within minutes to form function channels. This action provides one more example for the rather universal gating mechanism, which uses a cytoplasmic gate to transduce signals from within the cell to a channel in the membrane (22).

Figure 2.

Membrane topology of the MaxiK channel. The extracellular N terminus and the S0 segment (in brown) of the α subunit probably interacts with the β subunit. The tail domain (in green) of the α subunit can be made separately and may function as a cytoplasmic gate for Ca2+-gating. The core domain contains the six transmembrane segments S1-S6 that are homologous to the voltage-dependent K+ channel α subunits; it probably harbors the intrinsic voltage sensor and the pore-lining structures.

Remarkably, the MaxiK channel continues to exhibit left shifts as the Ca2+ concentration is raised from a few hundred nM to a few mM (15, 21). Just how this cytoplasmic gate, the tail of the α subunit, conveys the quantitative signal regarding [Ca2+]i to the voltage-gating machinery is a fascinating question for future investigation. Whichever way this signal is achieved, this Ca2+ gating can be further amplified by the β subunit (Fig. 1), which appears to interact with the extracellular N terminus and the S0 segment of the α subunit (23) (Fig. 2). Conceivably, the tetrameric channel has multiple Ca2+ binding sites, probably in the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the α subunits. For a homomeric channel to be sensitive to Ca2+ concentrations over four orders of magnitude, these binding sites probably exhibit different affinities for Ca2+, because of the presence of more than one binding site in each α subunit and/or cooperativity of the tetramer. Conformation changes induced by Ca2+ binding to the α subunit may stabilize the activated channel conformation relative to the inactive conformation, thereby making it easier to activate the channel by membrane depolarization. This change would result in a left shift in the voltage-dependence curve. The relative stability of the activated channel conformation could be further enhanced by the interaction between the α subunit and the β subunit, so as to exaggerate the left shift.

References

- 1.Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meech R W. J Physiol (London) 1974;237:259–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elkins T, Ganetzky B, Wu C F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8415–8419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tejedor F J, Bokhari A, Rogero O, Gorczyca M, Zhang J, Kim E, Sheng M, Budnik V. J Neurosci. 1997;17:152–159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robitaille R, Garcia M L, Kaczorowski G J, Charlton M P. Neuron. 1993;11:645–655. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson M T. Trends Cardiovas Med. 1993;3:54–60. doi: 10.1016/1050-1738(93)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carl A, Bayguinov O, Shuttleworth C W R, Ward S M, Sanders K M. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C619–C627. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.3.C619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pérez G, Toro L. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1459–C1463. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blatz A L, Magleby K L. Trends Neurosci. 1987;10:463–467. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latorre R, Oberhauser A, Labarca P, Alvarez O. Annu Rev Physiol. 1989;51:385–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaus H G, Folanker K, Garcia-Calvo M, Garcia M L, Kaczorowski G J, Smith M, Swanson R. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17274–17278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogalis F, Vincent T, Qureshi I, Schmalz F, Ward M W, Sanders K M, Horowitz B. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G629–G639. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.4.G629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallner M, Meera P, Ottolia M, Kaczorowski G J, Latorre R, Garcia M L, Stefani E, Toro L. Receptors Channels. 1995;3:185–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tseng-Crank J, Godinot N, Johansen T E, Ahring P K, Strøbaek D, Mertz R, Foster C D, Olesen S P, Reinhart P H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9200–9205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meera P, Wallner M, Jiang Z, Toro L. FEBS Lett. 1996;382:84–88. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson M T, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana L F, Bonev A D, Knot H J, Lederer W J. Science. 1995;270:633–637. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagrutta A, Shen K Z, North R A, Adelman J P. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20347–20351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tseng-Crank J, Foster C D, Krause J D, Mertz R, Godinot N, DiChiara T J, Reinhart P H. Neuron. 1994;13:1315–1330. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson H P, Baker O S, Dhillon D S, Isacoff E Y. Neuron. 1996;16:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei A, Solaro C, Lingle C, Salkoff L. Neuron. 1994;13:671–681. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meera P, Wallner M, Song M, Toro L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14066–14071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jan L Y, Jan Y N. Nature (London) 1994;371:119–122. doi: 10.1038/371119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallner M, Meera P, Toro L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14922–14927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]