Abstract

Proteins belonging to PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases constitute a functionally diverse superfamily with representatives involved in replication, restriction, DNA repair and tRNA–intron splicing. Their malfunction in humans triggers severe diseases, such as Fanconi anemia and Xeroderma pigmentosum. To date there have been several attempts to identify and classify new PD-(D/E)KK phosphodiesterases using remote homology detection methods. Such efforts are complicated, because the superfamily exhibits extreme sequence and structural divergence. Using advanced homology detection methods supported with superfamily-wide domain architecture and horizontal gene transfer analyses, we provide a comprehensive reclassification of proteins containing a PD-(D/E)XK domain. The PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases span over 21 900 proteins, which can be classified into 121 groups of various families. Eleven of them, including DUF4420, DUF3883, DUF4263, COG5482, COG1395, Tsp45I, HaeII, Eco47II, ScaI, HpaII and Replic_Relax, are newly assigned to the PD-(D/E)XK superfamily. Some groups of PD-(D/E)XK proteins are present in all domains of life, whereas others occur within small numbers of organisms. We observed multiple horizontal gene transfers even between human pathogenic bacteria or from Prokaryota to Eukaryota. Uncommon domain arrangements greatly elaborate the PD-(D/E)XK world. These include domain architectures suggesting regulatory roles in Eukaryotes, like stress sensing and cell-cycle regulation. Our results may inspire further experimental studies aimed at identification of exact biological functions, specific substrates and molecular mechanisms of reactions performed by these highly diverse proteins.

INTRODUCTION

The large and extremely diverse superfamily of PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases is a remarkable example of adopting a common structural scaffold to various biological activities. These enzymes encompass mainly nucleases (and their inactive homologs) and fill in a variety of functional niches including DNA restriction (1), tRNA splicing (2), transposon excision (3), DNA recombination (4), Holliday junction (HJC) resolving (5), DNA repair (6), Pol II termination (7), or DNA binding (8). The involvement of PD-(D/E)XK enzymes in housekeeping processes suggests that these proteins may be engaged in the development of genetic diseases. It should be noted that PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases exhibit very little sequence similarity, despite retaining a common core fold and a few residues responsible for the cleavage. The extreme sequence diversity, multiple insertions to a relatively small structural core, circular permutations (9) and migration of active site residues (10) render this superfamily a difficult subject to homology inference and hinders a new family identification with traditional sequence- or even structure-based approaches. In the present study our aim was to identify, classify and expand the existing repertoire of proteins belonging to the PD-(D/E)XK fold, in order to obtain a more complete picture of this superfamily.

The common conserved structural core of PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases consists of a central, four-stranded, mixed β-sheet flanked by two α-helices on both sides (with αβββαβ topology), forming a scaffold adopted for the active site formation (11) (Figures 1 and 2). This architecture and topology are classified in SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins) database (12) as a restriction endonuclease-like fold. The active site is located in a characteristic β-sheet Y-shaped bend (the second and third core β-strands) that exposes the catalytic residues (aspartic acid, glutamic acid and lysine, in a canonical active site) from the relatively conserved PD-(D/E)XK motif. In addition to the aforementioned motif, the conserved acidic residues from the core α-helices (usually glutamic acid from the first α-helix) often contribute to active site formation at least in a subset of families (10,13). Altogether, these residues play various catalytic roles which include coordination of up to three divalent metal ion cofactors, depending on the family. In addition, the residues from the second, positively charged α-helix can also contribute to the active site, although their major role is to facilitate the substrate binding and quaternary structure formation (14). The last, fourth core β-strand tends to be strongly hydrophobic as it is buried deeply within the hydrophobic core of the structure. This α/β/α sandwich fold is capable of accommodating a number of modifications (15) that often blur the image of the canonical structure of these enzymes. For a long time, proteins belonging to the PD-(D/E)XK nuclease-like superfamily had been considered as restriction enzymes, exclusively. However, many later experiments showed their contribution to DNA-branched structures resolving (5), double-strand breaks maintenance (16), or RNA maturation (17). In the following years PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases were extensively studied, reclassified (18) and their realm was consequently enlarged. Currently, there are 60 diverse families grouped into the ‘PD-(D/E)XK nuclease superfamily’ clan in the Pfam 26 database (19). This clan includes restriction enzymes, HJC resolvases, herpes virus exonucleases and various other nucleases from all kingdoms of life, sugar fermentation proteins, and several domains of unknown functions (DUFs). In addition, there are over 100 structures of PD-(D/E)XK nucleases cataloged in SCOP database (12) clustered into four main groups, encompassing restriction endonuclease-like enzymes, tRNA–intron splicing endonucleases, eukaryotic RPB5 N-terminal domain and TBP-interacting protein-like.

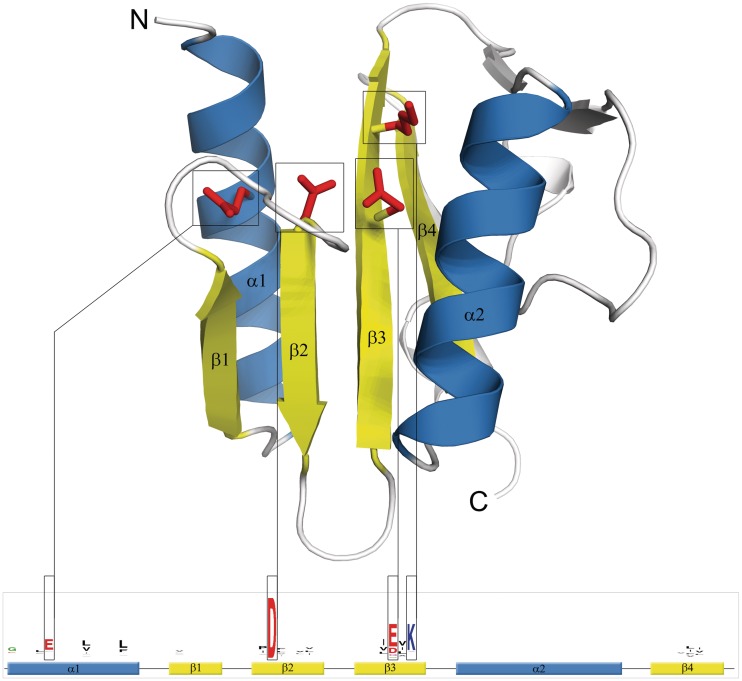

Figure 1.

The commonly conserved core of PD-(D/E)XK nuclease fold. Critical active site residues are shown as red sticks and marked in corresponding sequence logo. Sequence logo was derived from multiple sequence alignment for PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase superfamily using WebLogo (20).

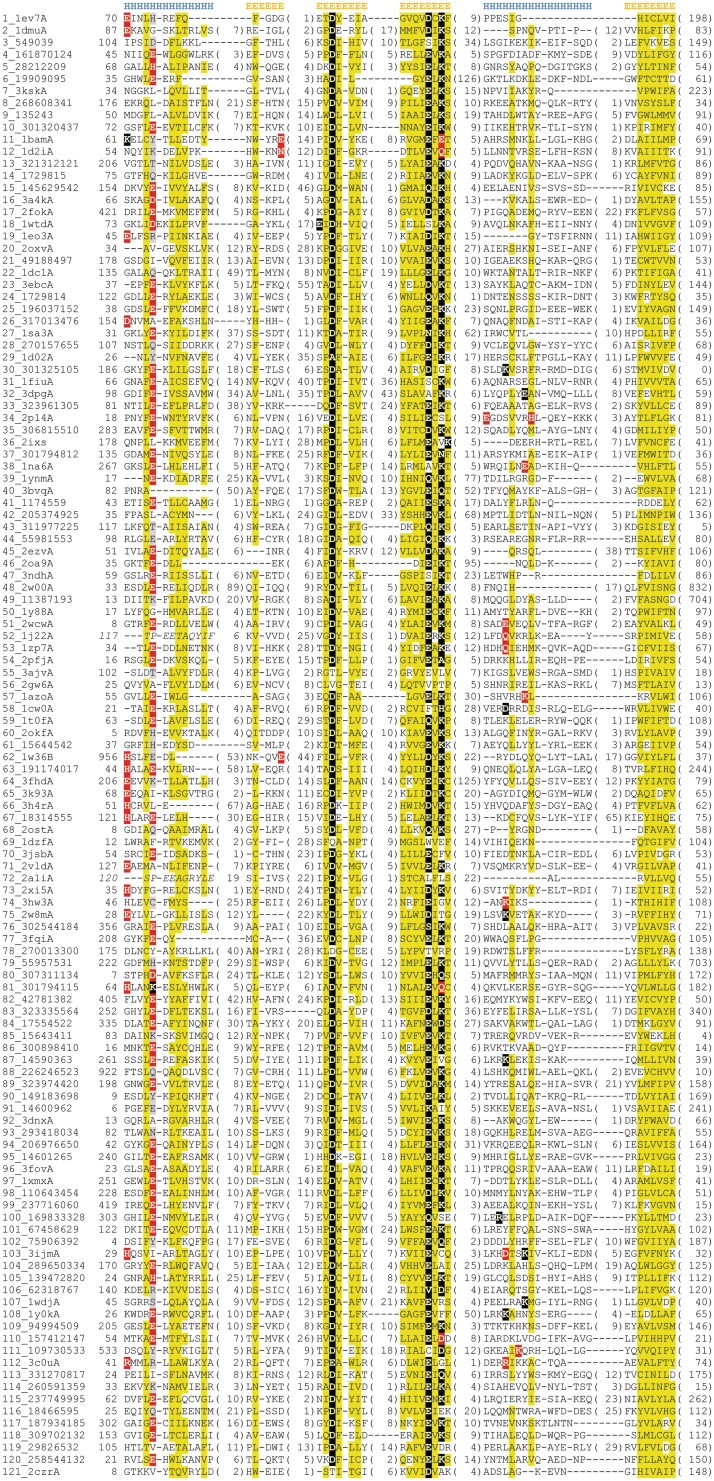

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment for the conserved core regions of the PD-(D/E)XK superfamily. Each group of closely related Pfam, COG, KOG families and PDB90 structures (detectable with PSI-BLAST) is represented by available PDB90 sequence or selected representative if the cluster does not contain solved structure. Sequences are labeled according to the group number followed by NCBI gene identification number or PDB code. The first residue numbers are indicated before each sequence, while the numbers of excluded residues are specified in parentheses. Sequence given in italic corresponds to circularly permuted α-helix. Residue conservation is denoted with the following scheme: uncharged, highlighted in yellow; polar, highlighted in grey; active site PD-(D/E)XK signature residues, highlighted in black; other conserved polar/charged residues augmenting the active site, highlighted in red. Locations of secondary structure elements are shown above the corresponding alignment blocks.

The PD-(D/E)XK proteins constitute a functionally diverse superfamily that addresses multiple nucleic acid maintenance issues. For instance, PD-(D/E)XK domain occurs in all classes of restriction enzymes, including those of type I, II, III and IV. Type II restriction endonucleases form the most diverged group of PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases. These enzymes, in concert with methyltransferases, set up the restriction–modification systems which protect bacterial and archaeal genomes against foreign genetic material (21). Host DNA is marked through methylation and therefore it is protected from accidental cleavage by a restriction enzyme which recognizes only unmethylated, foreign nucleic acid. Jeltsch and Pingoud proposed an evolutionary dependence between methyltransferases and restriction endonucleases (22). They managed to show that bacterial cells had acquired both a relevant methyltransferase and a restriction enzyme simultaneously in order to provide sufficient protection of host genetic material. Other restriction endonuclease-like fold proteins include mismatch repairing enzymes MutH and Vsr. These enzymes are a part of the machinery that recognizes and removes nucleotides improperly incorporated during recombination. MutH, which is a part of the MutHLS mismatch repair system, is a methylation- and sequence-specific nuclease (6,23). Vsr nuclease is a part of the Very Short Patch Repair system which aids MutHLS deficiency connected with the methylated cytosine spontaneous deamination. The PD-(D/E)XK proteins can also resolve HJC emerging from homologous recombination. HJC fastens together two homologous DNA molecules which, if unresolved, can lead to mutations (24). There are several PD-(D/E)XK protein families conserved through all kingdoms of life that recognize and cut branched DNA structures. These enzymes include RecU (25) and bacteriophage T7 HJC resolvase (endonuclease I) involved in genetic recombination during viral infection (26). XPF, ERCC4, Mus81 and Dna2 are also PD-(D/E)XK nucleases with structure-based specificity for DNA branched structures (27,28). They may cleave HJC or, as proven for Dna2, cut the remaining long flap RNA primers during the Okazaki fragment maturation (29). XPF was identified to process damaged DNA structures in mammalian nucleotide excision repair (NER) (27). Additionally, together with ERCC1, it cleaves DNA duplexes during homologous recombination. Mus81 participates in recombination and cell-cycle regulation (28). PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases also embrace exoribonucleases involved in homologous recombination and various DNA repair pathways, including RecB and its inactive homolog RecC from the RecBCD complex (16). The assortment of functional niches for PD-(D/E)XK proteins also encompasses mobile genetic element transposition, exemplified by TnsA transposase (3). Viral nucleases constitute another PD-(D/E)XK group. The alkaline exonuclease maintains extensively expressed viral DNA and degrades host mRNA molecules (30). Bacteriophage λ-exonuclease facilitates double strand break repair and single strand annealing (31). An eukaryotic Rai1-like (PF08652, KOG1982) plays an important role in pre-rRNA maturation by removing two phosphates from the 5′-termini leaving a 5′-monophosphate (7). The mitochondrial, membrane-bound Pet127 (PF08634) protein is suggested to process the apocytochrome-b precursor during mRNA maturation (32). RPB5, a universal subunit of all three major eukaryotic RNA polymerase complexes, also retains the PD-(D/E)XK fold. RPB5 interacts with several transcription factors, such as TFIIB or HBx, and the TIP120 pre-initiation complex (8). The tRNA splicing endonucleases that constitute a well distinguishable group of archaeal and eukaryotic proteins within the PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase realm are a very interesting example of alternative function gain through acquisition of a novel active site. They are vital for maturation of tRNA molecules by performing intron excision from an anticodon loop (2). Their activity is crucial for tRNA intron identification and removal, allowing ligases and phosphotransferases to complete the tRNA maturation process.

In humans, the malfunction of some PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases is linked to severe, inherited diseases involving neurological abnormalities and susceptibility to develop early onset malignancies. Mutations in tRNA splicing endonuclease lead to pontocerebellar hypoplasia (PCH) (33) which is related to mental and motor impairments. Mutations in XPF–ERCC1, an NER repair pathway structure-dependent endonuclease, are one of the primary causes of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) (34). XP manifests itself by increased sensitivity to sunlight with the development of carcinomas. Fanconi anemia (FA) is a consequence of mutations in PD-(D/E)XK proteins [e.g. FANCM (35)], participating in DNA repair and involves developmental abnormalities, bone marrow failure, and a predisposition to cancer.

Up to date there have been several attempts to identify and classify new PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases, such as YhgA (36), UL24 (37), NERD (38), CoiA (39), RmuC (39) protein families or various restriction enzymes (1). Those studies were mainly based on remote homology detection methods, as the extreme sequence divergence of the PD-(D/E)XK enzymes remains the main obstacle in detection of new superfamily members. This inspired the development of a dedicated SVM (Support Vector Machines) algorithm for the identification of the PD-(D/E)XK active site signature within protein sequences (11). The discussed analyses covered a large part of the PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase world, however each approach individually relied on a limited set of initial sequences and did not provide a widespread view on the PD-(D/E)XK fold. Therefore, in order to confer our work a broader perspective, first we collected the structures and families annotated as restriction endonuclease-like enzymes. This set was used as a starting point for exhaustive, transitive fold recognition searches aiming to obtain the most complete set of PD-(D/E)XK proteins available in current databases. Here we report a comprehensive reclassification of proteins containing a PD-(D/E)XK domain, including their domain architecture, taxonomic distribution and genomic context.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A brief overview of our methods is presented below with further details given in Supplementary Materials (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). Detection of PD-(D/E)XK families (Pfam, COG, KOG) and structures (PDB90) was performed with a distant homology detection method, Meta-BASIC (40). Non-trivial assignments were additionally confirmed with a consensus of fold recognition, 3D-Jury (41). Sequences of proteins belonging to the identified families were collected with PSI-BLAST (42) searches against NCBI nr database. Multiple sequence alignments were prepared using PCMA (43). In addition, structure-based alignment was derived from a manually curated superimposition of PD-(D/E)XK structures. The final alignment for PD-(D/E)XK superfamily was assembled from sequence-to-structure mappings using a consensus alignment and 3D assessment approach (44). The collected PD-(D/E)XK fold proteins were clustered into groups of closely related families and structures based on detectable sequence similarity with both PSI-BLAST and RPS-BLAST. Structure similarity based searches were performed with ProSMoS program (45). Domain architecture was analyzed with RPS-BLAST against COG, KOG and Pfam, and with HMMER3 against Pfam. Transmembrane regions were detected with a TMHMM server (46). Cellular localization for prokaryotic sequences was predicted with PSORTb (47) and for eukaryotic with Cello (48), WoLF PSORT (49) and Multiloc (50). Taxonomic assignment was based on NCBI taxonomic identifiers. HGT events were identified using a phylogenetic approach. Phylogenetic trees for each cluster were calculated using PhyML. The genomic context was analyzed with The SEED (51), GeContII (52), MicrobesOnline (53) and NCBI genomic resources. Clustering of all 21 911 sequences was performed with CLANS (54), with high resolution figures drawn with an in-house script based on CLANS scores.

RESULTS

In order to broaden the repertoire of PD-(D/E)XK proteins we performed sensitive distant homology searches using as the initial dataset 44 Pfam 25 families and 60 representative restriction endonuclease-like proteins of known structure cataloged in SCOP database. The exhaustive, transitive fold recognition searches against Pfam, COG, KOG and PDB90 databases resulted in a collection of various PD-(D/E)XK families that altogether span 21 911 sequences from the NCBI nr protein database (a list of all identified proteins is provided as Supplementary Dataset S1). For instance, we found that 99 PDB90 structures, 49 COG, 11 KOG and 118 Pfam families retain the PD-(D/E)XK fold. This is significantly more than the currently reported in Pfam 26 database in PD-(D/E)XK nuclease superfamily clan which defines only 60 families. In addition, we found six PD-(D/E)XK fold families to be classified also in two other Pfam clans: (i) Restriction endonuclease-like (Endonuc-FokI_C, PF09254; MutH, PF02976; RE_AlwI, PF09491) and (ii) tRNA–intron endonuclease catalytic domain-like (Sen15, PF09631; tRNA_iecd, PF12858; tRNA_int_endo, PF01974).

All PD-(D/E)XK proteins were identified with a single procedure as described in our previous work (36). This exemplifies a major progress in comparison with previous studies on the diversity of PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase superfamily. All collected families and structures were clustered into 121 groups of closely related proteins. The average sequence similarity between different PD-(D/E)XK groups is very low, which is reflected by low Meta-BASIC scores (Supplementary Table S1) and is below the confident recognition both with standard and even more advanced sequence comparison methods. This high sequence divergence implies the need for complex sequence and structure search strategies. Many of the identified protein groups contain uncharacterized and poorly annotated proteins or functionally studied proteins without structural annotations. Eventually, upon further manual literature inspection, the majority of these families were linked to the PD-(D/E)XK superfamily. However, such an assignment was feasible with a list of proteins in question. The remaining 11 identified groups embrace the newly found PD-(D/E)XK fold families.

We detected PD-(D/E)XK sequences in multiple genomes from all forms of life. The versatility of this superfamily convinced us to perform a variety of structure- and sequence-based analyses. We thoroughly examined every family in our dataset in order to determine its characteristic sequence and structure features. Here, we describe in detail the results of sequence and literature searches, domain architecture analysis, structural comparisons and phylogenetic inference, that eventually shed new light on functional diversity of PD-(D/E)XK proteins. Table 1 summarizes the details of all identified PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase groups. Human genes encoding PD-(D/E)XK proteins are shown in Supplementary Table S2. One should note that most of the human PD-(D/E)XK genes are involved in diseases.

Table 1.

One hundred and twenty-one groups of proteins retaining PD-(D/E)XK nuclease fold

| No. | Name |  |

|

Biological function | Taxonomy |

HGTs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Detailed distribution | ||||||

| 1 | NaeI | PF09126 | (58) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (58) | + | Bacteria (α-proteobacteria, Actinobacteria) | Deinococcus maricopensis sequence is found in a clade with Roseobacteriales (α-proteobacteria) & Actinomycetales. The Roseobacteriales clade locates within a Actinomycetales tree. | |||

| 1ev7 | ||||||||||

| 2 | BglI | 1dmu | (59) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (59) | + | Bacteria | Only four sequences from distant taxa: Bacillus atrophaeus (Bacilli), Microcoleus (Oscillatoriales), Deinococcus deserti (Deinococci) suggest a HGT. | |||

| 3 | HpaII | PF09561 | New | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (60) | + | Bacteria (Bacillus/Clostridium, Bacteroidetes) | Streotibacillus moniliformis (Fusobacteriales) forms a clade with Sulfurimonas denitrificans (Campylobacteriales). Bacillus thuringiensis (Bacillales) groups with Flexibacter tractuosus (Cytophagales). Single sequences of Fusobacteria, ε-proteobacteria, β-proteobacteria and γ-proteobacteria. | |||

| 4 | NgoBV, NlaIV | PF09564 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (61) | + | Bacteria (mostly Neisseria) | Multiple transfers, animal related bacteria. Single representatives of: Spirochaetes, Fusobacteria, Tenericutes, ε-proteobacteria, Clostridia, Bacilli. | |||

| 5 | ScaI | PF09569 | New | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (62) | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfers. Ecologically and taxonomically unrelated bacteria from Bacilli, Proteobacteria, Cyanobacteria, Bacterioidetes. | |||

| 6 | LlaMI, ScrFI | PF09562 | (63) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (63) | + | Bacteria (Cyanobacteria, Bacillus/Clostridium, γ-proteobacteria) | One clade grouping: Lachnospiraceae bacterium (Clostridiales), Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (Lactobacillales), Prochlorococcus marinus (Cyanobacteria), Vibrio parahaemolyticus (γ-proteobacteria). | |||

| 7 | PvuII | PF09225 | (64) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (64) | + | Bacteria | Meiothermus ruber (Thermales), Bacteroides cellulosilyticus (Bacteroidales) and Arthrospira maxima (Burkholderiales) are single representatives of corresponding taxa suggesting a transfer event from Enterobacteriales. | |||

| 3ksk | ||||||||||

| 8 | XamI | PF09572 | (11) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (65) | + | {1} | Bacteria | Patchy distribution including a Haloarcheon—Halogeometricum borinquense grouping with good support within a bacterial clade. | ||

| 9 | XhoI | PF04555 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (66) | + | {1} | Bacteria (mostly Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria) | Leptospirillum rubarum and 3 Actinobacteria within a Proteobacteria clade. | ||

| 10 | ApaLI | PF09499 | (67) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (62) | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfers, Helicobacter felis (ε-proteobacteria) with Microscilla marina (Bacterioidetes). Patchy distribution including single sequences from Bacillales, Chloroflexales, Xantomonadales, Fusobacteriales, Beggiatoales, Borrelomycetales, Campylobacteriales. | |||

| 11 | BamHI | PF02923 | (68) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (68) | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfers, extremophilic and/or aquatic bacteria. | |||

| 1bam, 3odh | ||||||||||

| 12 | BstYI, BglII | PF09195 | (69) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (69) | {1} | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfers for example B. subtilis sequence grouped with Cyanobacteria. Ethanoligenens harbinense (Clostridiales) is located in a Proteobacteria clade. | ||

| 1sdo, 1d2i | ||||||||||

| 13 | SacI | PF09566 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (70) | + | Bacteria (Bacilli) | Multiple transfers. Patchy distribution: single sequences Bacteroides, Actinobacteria, γ-proteobacteria, ε-proteobacteria. | |||

| 14 | Eco47II | PF09553 | New | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (71) | {1} | + | Bacteria | Helicobacter pylori sequence groups within a Mycoplasma clade, multiple transfers. | ||

| 15 | HaeII | PF09554 | New | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (72) | + | Bacteria (mostly γ- and β-proteobacteria) | Cyanobacteria sequences not grouped. Single sequences from Cyanobacteria, Bacterioidetes. | |||

| 16 | HindIII | PF09518 | (73) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (73) | + | Bacteria (mostly γ-proteobacteria) | Multiple transfers: Citrobacter (γ-proteobacteria) within a Bacilli clade, oral bacterium Streptococcus downei grouped together with Haemophilus influenzae. | |||

| 3a4k | ||||||||||

| 17 | FokI | PF09254 | (14) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (14) | + | Bacteria (Bacillus/Clostridium) | Haemophilus influenzae within a Streptococcus sanguinis clade. | |||

| 2fok | ||||||||||

| 18 | EcoO109I | 1wtd | (74) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (74) | + | Bacteria (Escherichia coli) | No HGT observed | |||

| 19 | EcoRV | PF09233 | (75) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (75) | + | {2} | Bacteria | Escherichia coli in a clade with Streptococcus mitis (Lactobacillales), Listeria innocua (Bacillales), Vibrio orientalis (Vibrionales) and Thiomonas (Burkholderiales)a | ||

| 1eo3 | ||||||||||

| 20 | EcoRI | PF02963 | (76) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (76) | + | {1} | Bacteria (BCF group, Proteobacteria, Bacillus/Clostridium) | Methanobrevibacter smithii, Staphylococcus aureus, Fusobacterium ulcerans and Brucella melitensis group together with 5 E. coli Migula 1895 sequences. Multiple transfers | ||

| 2oxv | ||||||||||

| 21 | XcyI | PF09571 | (77) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (77) | + | Bacteria (γ-proteobacteria, Clostridium) | Pseudomonas alcaligenes (soil bacterium) in a plant pathogenic Xanthomonas clade, Proteobacteria in a extremophilic Clostridium clade. Multiple transfers | |||

| 22 | BsoBI | PF09194 | (78) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (78) | + | Bacteria (mostly Cyanobacteria) | Roseiflexus castenholzii phototrophic bacterium and intestinal Alistipes sp. within a mostly Cyanobacteria clade | |||

| 1dc1 | ||||||||||

| 23 | HincII | PF09226 | (79) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (79) | + | Bacteria (mostly γ-proteobacteria) | Oral bacterium Capnocytophaga ochracea within a Haemophilus & Actinobacillus clade. Additionally, Prevotella bivia pathogen, joins this clade | |||

| 3ebc | ||||||||||

| 24 | SinI, AvaII | PF09570 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (22) | + | Bacteria | Patchy distribution | |||

| 25 | NgoPII | PF09521 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (80) | + | + | Prokaryota | Patchy distribution, possible transfer between Desulfurobacterium thermolithotrophicum (Aquificiae) and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and Candidatus Parvarchaeum acidiphilum (Euryarchaeota) | ||

| 26 | Tsp45I | PF06300 | New | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (81) | + | Bacteria | Possible transfer between Simonsiella muelleri (β-proteobacteria) and Fusobacterium periodonticum (Fusobacteria). Patchy distribution including: Prevotella, Treponema and Chlorobium | |||

| 27 | MspI | PF09208 | (82) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (82) | + | Bacteria (mostly Bacilli/Clostridia) | Two γ-proteobacteria (Idiomarina loihiensis, Moraxella) within a Firmicutes clade. Moraxella opportunistic pathogen groups with Clostridium botulinum. Deep sea I. loihiensis groups with Anoxybacillus flavithermus thermophile. Patchy distribution | |||

| 1sa3 | ||||||||||

| 28 | MjaII | PF09520 | (11) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (83) | + | + | Prokaryota | Possible transfer between Archaea and Bacteria. Patchy distribution | ||

| 29 | MunI | PF11407 | (83) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (83) | + | {1} | Bacteria | Desulfurivibrio alkaliphilus and Prevotella copri prossible transfer. Cenarchaeum symbiosum groups together with Tenericutes and Clostridia. Cenarchaeum symbiosum is a partner of a marine sponge (84) | ||

| 1d02 | ||||||||||

| 30 | CfrBI | PF09516 | (1) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (85) | + | Bacteria (mostly proteobacteria) | Anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis, thermophilic Geobacillus stearothermophilus and Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii group within a Proteobacteria tree | |||

| 31 | NgoMIV | PF09015 | (85) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (85) | + | Bacteria | Bacteroides finegoldii groups within Heliobacterium modesticaldum and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (Clostridiales) clade. Thermomonospora curvata (Actinomycetaceae), Opitutaceae bacterium TAV2 (Opitutaceae) and Idiomarina baltica (Alteromionadaceae) group together | |||

| 1fiu | ||||||||||

| 32 | Cfr10I, Bse634I, SgrAI | PF07832 | (86) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (86) | + | Bacteria | Pseudomonas stutzeri (Pseudomonadales), Nodularia spumigena (Nostocales) and Streptomyces griseus (Actinomycetales) sequences group together | |||

| 1cfr, 1knv | ||||||||||

| 3dpg | ||||||||||

| 33 | Bpu10I | PF09549 | (87) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (87) | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfer events. One clade encompasses representatives of Cyanobacteria (Cyanothece and Nodularia), Proteobacteria (E. coli, Allochromatium vinosum, Plesiocystis pacifica), Chloroflexi (Chloroflexus aurantiacus) and Actinobacteria (Gardnerella vaginalis) | |||

| 34 | BspD6I, AlwI, MlyI | PF09491 2ewf, 2p14 | (88) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease | + | {1} | Bacteria | Micrococcus lylae (Actinomycetales) and Methanohalobium evestigatum (Euryarchaeota) forming a common clade or Mannheimia haemolytica (γ-proteobacteria) within a Firmicutes clade are examples of possible HGT. M. haemolytica causes intramammary infection in sheep. Micrococcus lylae is a denitrifying soil bacterium whereas M. evestigatum is an extreme halophilic methanogen | ||

| Restriction Endonuclease (88) | ||||||||||

| 35 | LlaJI, McrBC | PF09563 | (89) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (89) | + | + | {1} | Prokaryota | Mobiluncus curtisii subsp. curtisii (Actinomycetales) within a Clostridium clade. Gardnerella vaginalis (Actinomycetales) forms a clade with L. lactis (Lactobacillales) and Anaerostipes caccae (Clostridiales). Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis JAM81 (Chytrydiomycota, Fungi) forms a clade with Desulfotomaculum nigrificans (Clostridiales). Methanobrevibacter ruminantium DSM 1093 (Euryarchaeota) locates in a mostly Firmicutes clade | |

| PF10117 | ||||||||||

| COG4268 | ||||||||||

| 36 | SdaI, BsuBI | PF06616 | (90) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (90) | + | {1} | Bacteria | Treponema vincentii (Spirochaetales), B. subtilis and Paenibacillus larvae subsp. larvae (Bacillales) within a Proteobacteria clade. Shewanella sediminis (Enterobacteriales) sequence groups with Clostridium sticklandii (Clostridiales). Methanobrevibacter ruminantium (Euryarchaeota) forms a clade with 2 Prevotella (Bacteroidales) sequences. Methanobrevibacter ruminantium is a rumen bacterium of cattle and Prevotella is involved in periodontal infections | ||

| 2ixs | ||||||||||

| 37 | DpnII, MboI | PF04556 | (91) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (91) | + | + | Prokaryota | Carboxydothermus hydrogeniformans in a Mycoplasma clade. Extremophilic Dictyoglomus thermophilum (Dictyoglomi) with M. smithii & Methanosphaera stadtmanae (Euryarchaeota) | ||

| 38 | Ecl18kI, EcoRII, PspGI | PF09019 | (92) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (92) | {2} | + | {1} | Bacteria | Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida (Vibrionales) sequence locates within an Enterobacteriaceae clade (Klebsiella, Shigella, Escherichia and Yersinia) | |

| 2fqz, 1na6 | ||||||||||

| 3bm3 | ||||||||||

| 39 | HinP1I | PF11463 | (93) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (93) | + | Bacteria (Proteobacteria) | Leptotrichia goodfellowii (Fusobacteriales) in a Proteobacteria clade. Moraxella catarrhalis (Pseudomonadaceae) in a Haemophilus clade (Pasteruellaceae). Haemophilus somnous is a bovine pathogen, L. goodfellowii is found in dental plaque. Moraxella catarrhalis was recently described as a respiratory pathogen | |||

| 1ynm | ||||||||||

| 40 | NotI | PF12183 | (94) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (94) | + | Bacteria | Desulfobacterium sp. (Deltaproteobacteria) and Syntrophomonas wolfei (Clostridiales) in a green sulfur bacteria Chlorobium phaeobacteroides clade | |||

| 3bvq | ||||||||||

| 41 | Bsp6I | PF09504 | (95) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (95) | {1} | + | Bacteria | Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fusobacteria) sequence localizes in a Ureaplasma/Mycoplasma (Borrellomycetales) clade | ||

| 42 | HindVP, HgiDI, BsaHI | PF09519 | (96) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (96) | + | Bacteria | Patchy taxonomic distributiona | |||

| 43 | MjaI | PF09568 | (67) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease | {1} | + | + | Prokaryota | Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus within a BCF group clade | |

| 44 | TaqI | PF09573 | (97) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (97) | + | Bacteria (Thermus, Aquficae, Nitrospirae) | Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirae) in a Hydrogenivirga sp. (Aquificae) clade | |||

| 45 | SfiI | PF11487 | (98) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (98) | + | Bacteria | No HGT observed, the phylogeny could not be resolved with reliable confidence | |||

| 2ezv | ||||||||||

| 46 | MvaI, BcnI | 2odh, 2oa9 | (99) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (99) | + | {2} | Bacteria | Thermoplasma volcanium (Euryarchaeota) within mixed bacterial clades | ||

| 47 | ThaI | 3ndh | (100) | Type II Restriction Endonuclease (100) | + | Archaea (Thermoplasmata) | No HGT observed | |||

| 48 | HSDR_N, HSDR_N_2, EcoR124I |

|

(101) | Type I Restriction Endonuclease (101); EcoR124I cleaves DNA at a location distant from specific recognition site (102). | + | + | {1} | Prokaryota | Simonsiella muelleri (β-proteobacteria) in a H. influenzae (γ-proteobacteria) clade. A single sequence from Vibrio splendidus (Vibrionales) locates in an Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae & Haemophilus parasuis (Pastereullaceae) clade | |

| Type IV Restriction Endonuclease (predicted, found mostly in Archaea) | ||||||||||

| 49 | HindVIP, EcoPI |

|

(103) | + | + | + | Prokaryota & phages | Lactobacillus helveticus (Lactobacillales) and Pseudomonas stutzeri (Pseudomonadales) form a perfectly supported group. Phylogeny is not well resolveda | ||

| 50 | Mrr_cat, DUF2034 |

|

(105) |

|

{2} | + | + | + |

|

No HGT observed, the phylogeny could not be resolved with reliable confidence |

| 51 | Archaeal HJC |

|

(24) | HJC resolvase (107) | + | + | + | Prokaryota (mostly Archaea) & Archaeal phages | A handful of unrelated bacteria: Fusobacterium nucleatum subsp. polymorphum, Fusobacterium sp., Hydrogenobaculum sp., Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. viciae, Ralstonia solanacearum, E. coli TA206, Nitratiruptor sp. and Synechococcus sp. form a clade within the Archeal tree | |

| 52 | ERCC4, XPF, Mus81 |

|

(9) |

|

+ | + | Archaea & Eukaryota | No HGT observed | ||

| 53 | RecU, HJC Resolvase, Penicillin-binding protein-related factor A |

|

(24) | HJC resolvase (109). The genomic context is well conserved and includes a penicilin-binding protein, a methylase and HhH domain containing proteins. Penicillin-binding proteins are involved in cell-wall biosynthesis. | + | Bacteria (Bacillus/Clostridium) | Catonella morbi (Clostridiales) in a Lactobacillales clade. Acholeplasma laidlawii (Tenericutes) in a Bacillus clade | |||

| 54 | Bacteriophage T7 endonuclease I, Phage_endo_I | PF05367 | (110) | HJC resolvase (110) | + | + | + | Prokaryota & phages | Halanaerobium hydrogeniformans (Firmicutes) locates with Dehalococcoides sp. and Thermomicrobium roseum (Chloroflexi). Patchy distribution suggesting multiple transfers. Phages group with their hosts | |

| 2pfj | ||||||||||

| 55 | tRNA intron endonuclease |

|

(17) | tRNA intron endonuclease, in the proximity of various tRNA synthases in archaeal genomes. | + | + | Archaea & Eukaryota | No HGT observed | ||

| 56 | Sen15 |

|

(111) | A structural subunit of eukaryotic tRNA intron endonuclease (111) | + | Eukaryota (Ophisthokonta, Amoebozoa) | No HGT observed | |||

| 57 | MutH |

|

(6) | Mismatch repairing enzyme (6). MutH cleaves a newly synthesized and unmethylated daughter strand 5′ to the sequence d(GATC) in a hemi-methylated duplex. | + | Bacteria (γ-proteobacteria) | Plautia stali symbiont (unclassified bacterium) in a γ-proteobacteria clade | |||

| 58 | VSR, DUF559, DUF2726 |

|

(112) | {1} | + | + | Prokaryota | No HGT observed | ||

| 59 | TnsA | PF08722 | (114) | Transposase (114) | + | {1} | Bacteria | Ricinus communis and Vibrio harvei form a clade, might be a long branch attraction phenomenon. Deinococcus proteolyticus in a Proteobacteria clade. Mixed clades containing: Bacilli, Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria and Proteobacteria | ||

| 1t0f | ||||||||||

| 60 | XisH | PF08814 | Pfam | fdxN element excision controlling factor (115) | + | Bacteria (mostly Cyanobacteria) | Herpetosiphon aurantiacus in a Cyanobacteria clade. Beggiatoa sp. (γ-proteobacteria) in a Cyanobacteria cladea | |||

| 2inb, 2okf | ||||||||||

| 61 | DUF83, Cas_Cas4 | PF01930 | (5) | Cas1 protein (YgbT) has nuclease activity against single-stranded and branched DNAs including HJC, replication forks and 5′-flaps (116). | + | + | {1} | Prokaryota | Not resolved phylogeny. Aureococcus anophagefferens (Stramenopile, Eukaryota) sequence is localized in a mixed Bacteria clade. Aureococcus anophagefferens causes algal blooms. Planctomycetes are isolated from marine water | |

| COG1468 | ||||||||||

| COG2251 | ||||||||||

| 62 | RecBCD, Exonuclease V |

|

(16) | Exonuclease/helicase, a component of the RecBCD complex that handles double-strand breaks (DSB) (16). RecB alone has a weak helicase activity (117) and its nuclease domain generates single-strand regions at the ends of DSBs (5). | + | {1} | Bacteria (Clostridium/Bacillus, Chlorobiales, γ-proteobacteria) | Oryza sativa protein groups in an Enterobacteriaceae clade within a Serratia proteins | ||

| 63 | DUF2800, PDDEXK_1 |

|

(118) | RecB-like, probable prophage proteins | + | + | Bacteria phages | Dehalococcoides ethernogenes (Chloroflexi) sequence resides in a Clostridiales clade | ||

| 64 | Viral alkaline exonuclease | PF01771 | (30) | Exonuclease processing viral genome during recombination (4). The enzyme displays RNase activity used in mRNA degradation pathways (4). | + | Herpesvirales | No HGT observed | |||

| 2w45, 3fhd | ||||||||||

| 65 | YqaJ, lambda-exonuclease |

|

(31) | Exonuclease facilitating phage DNA recombination (31). The λ exonuclease is an ATP-independent enzyme that binds to dsDNA ends and processively digests the 5′-ended strand to form 5′-mononucleotides and a long 3′-overhang (119). | + | + | + |

|

No HGT observed | |

| 66 | RecE, DUF3799 | PF12684 | (120) | Exonuclease from RecET recombination system (120) | + | + | Bacteria phage | No HGT observed, the phylogeny could not be resolved with reliable confidence | ||

| 3h4r, 3l0a | ||||||||||

| 67 | DEM1, EXO5 | PF09810 | Pfam | Mitochondrial, single-strand-specific 5′-exonuclease releasing dinucleotides as the main products of catalysis. EXO5 binds to 5′-RNA termini of chimeric DNA–RNA molecules and, after sliding across the RNA substrate, cuts the DNA 2 nt from the RNA–DNA junction (121). | {1} | + | + | + | Archaea (Euryarchaeota) | Methanocella paludicola in a Actinobacteria clade. Methanocella paludicola is a methanogen isolated form rice paddy soil. Eubacterium eligens (Clostridiales) in an Ascomycota clade (very long branch) |

| KOG4760 | Eukaryota | |||||||||

| 68 | ssp6803i | PF11645 | (122) | Homing endonuclease with a specificity profile extending over a long (17-bp) target site (122) | + | + | Prokaryota | Patchy distribution including 5 Haloarcheales and 2 Ktedonobacter sequences as well as Bacillus forming a sister clade to 5 sequences Cyanobacteria suggest a HGT history | ||

| 2ost | ||||||||||

| 69 | Rpb5 N-terminal domain | PF03871 | (8) | RNA Polymerase (8). It may hold together the Rpb1-β24/25 and Rpb1-α44/47-fold of RNA polymerase II, or their counterparts in the archaeal, viral and RNA polymerase I and III enzymes (123). | + | Eukaryota | No HGT observed | |||

| KOG3218 | ||||||||||

| 1dzf, 3h0g | ||||||||||

| 70 | Arenavirus RNA polymerase N-terminal domain, virus L-Protein | PF06317 | (124) | RNA Polymerase N-terminal domain that utilizes ‘cap snatching’ mechanism for viral mRNA transcription (125). Similar to groups 73 and 74 | + | Arenavirus | No HGT observed | |||

| 3jsb | ||||||||||

| 71 | RecB, DUF91 | PF01939 | (126) | DNA endonuclease specialized in cleavage at double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)/ssDNA junctions on branched DNA substrates (126) | + | + | Prokaryota (Actinobacteria, β-proteobacteria) | All 3 sequences from Deinococcus-Thermus are located within the Archaea clade. The Proteobacteria sequences are close to the root, this topology is not well resolved | ||

| COG1637 | ||||||||||

| 2vld | ||||||||||

| 72 | ERCC1-XPF, Swi10, Rad10 | PF03834 | (127) | Nuclease of NER system incising oligonucleotide from damaged DNA strand (128) | + | Eukaryota | No HGT observed | |||

| KOG2841 | ||||||||||

| COG5241 | ||||||||||

| 2a1i | ||||||||||

| 73 | La crosse virus L-protein | 2xi5 | (129) | Cap-snatching Endonuclease; cleaves short and capped host primers that are subsequently used by viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase to transcribe viral mRNAs (129) | + | Bunyaniviridae | No HGT observed | |||

| 74 | Viral L-protein | PF00603 | (130) | Cap-snatching Endonuclease, mechanism identical to that described above (131) | + | Influenza A virus | Phylogeny not resolved | |||

| 3hw3 | ||||||||||

| 75 | D212 | PF12187 | (132) | Uncharacterized nuclease suggested to take part in DNA replication, repair, or recombination (132) | + | + | Archaea (Sulfolobus) archaeal phages | Phages and prophages of Sulfolobus, together form one coherent clade | ||

| 2w8m | ||||||||||

| 76 | Archaea bacterial proteins of unknown function, DUF234 | PF03008 | (5) | DEXX-box ATPase belonging to AAA+ superfamily; DEXX-box ATPases act to transduce the energy of ATP-hydrolysis into a conformational stress required for the remodeling of nucleic acid or protein–nucleic acid structure (133). | + | + | Prokaryota | Two Treponema vincentii (Spirochaetales) sequences are in a Butyrivibrio proteoclasticus/ Ruminococcus bromii/Roseburia inulinivorans rumen bacteria (Clostridiales) clade | ||

| COG1672 | ||||||||||

| 77 | RAI1-like, Dom-3z | PF08652 | (7) | Exoribonuclease. Has a pyrophosphohydrolase activity towards 5′-triphosphorylated RNA (7). | + | Eukaryota | No HGT observeda | |||

| KOG1982 | ||||||||||

| 3fqg, 3fqi | ||||||||||

| 78 | NARG2 | PF10505 | (134) | Nuclear protein involved in thickness of the brain’s cortical gray matter regulation (57) | + | Eukaryota (without Plantae & Chromoalveolata) | No HGT observed | |||

| 79 | DUF911, Dna2 |

|

(39) | Dna2 processes common structural intermediates that occur during diverse DNA processing (e.g. lagging strand synthesis and telomere maintenance) (135). Dna2 is a dual polarity exo/endonuclease, and 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase involved in Okazaki Fragment Processing (OFP) (136) and DSB Repair (137). DUF911 function is unknown. | + | + | + | Prokaryota & Eukaryota | Very long branches, dubious positioning of various taxons | |

| 80 | YhgA-like | PF04754 | (36) | Putative transposase (138). The genomic context is not conserved even among strains of one species suggesting recent mobility. | + | Bacteria (γ-proteobacteria) | Three Burkholderia rhizoxinica (β-proteobacteria) sequences are present on a Enterobacteriales clade forming a sister clade to a Yersinia clade | |||

| COG5464 | ||||||||||

| 81 | CoiA-like | PF06054 | (39) | Negative regulator of competence. CoiA is probably involved after DNA uptake, either in DNA processing or recombination (139). | + | Bacteria (Bacillus, Lactobacillus) | No HGT observed | |||

| COG4469 | ||||||||||

| 82 | DUF524 | PF04411 | (36) | Predicted restriction endonuclease (36). Co-occurs with a restriction GTPase or ATPase. | + | + | Bacteria & Euryarchaeota | Mixed clades like: Geobacter uraniireducens (Deltaproteobacteria) together with Gallionella capsiferriformans (β-proteobacteria) and Chlorobium luteolum (Chlorobia) | ||

| COG1700 | ||||||||||

| 83 | Mitochondrial protein Pet127 | PF08634 | (134) | 5′-exonuclease responsible for processing the precursor to the mature form (140) involved in modulation of mtRNAP activity | + |

|

Distribution limited to different unicellular eukaryote, not enough sequencing data for a HGT hypothesis | |||

| 84 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit 7, eIF-3-zeta, eIF3 p66, moe1 | PF05091 | (134) | eIF3 p66 is the major RNA-binding subunit of the eIF3 complex; Cdc48, Yin6 and Moe1 act in the same protein complex to concertedly control ERAD and chromosome segregation (141). | + | Eukaryota | No HGT observed | |||

| KOG2479 | ||||||||||

| 85 | Secreted endonuclease distantly related to HJC resolvase | PF10107 | (11) | Predicted secreted endonuclease distantly related to archaeal HJC resolvase | + | + | {1} | Prokaryota | A sequence of a bacteria feeding nematode Caenorhabditis remanei in an Acintobacter clade. Archaea sequences in Bacteria clades | |

| COG4741 | ||||||||||

| 86 | DUF1064 | PF06356 | (39) | Unknown, In firmicutes co-occurs with: RecT, DnaC, DnaB, SSB what suggest a role in recombination. In Proteobacteria phage proteins are also present. | + | + | Bacteria phages | Beggiatoa sp. (γ-proteobacteria) within a Clostridiales clade | ||

| 87 | DUF790 | PF05626 | (39) | Unknown. Co-occurs with ResIII and helicase domains. | + | + | Prokaryota | A single sequence of Rubrobacter xylanophilus (Actinobacteria) locates with Cyanobacteria and Deinococci | ||

| COG3372 | ||||||||||

| 88 | VRR-NUC | PF08774 | (39) | A DNA repair nuclease recruited to DNA damage by monoubiquitinated FANCD2 (142) exhibits endonuclease activity toward 5′ flaps and has 5′ exonuclease activity. In γ-proteobacteria co-occurs with DEAD_2 helicase and bacterial extracellular solute-binding protein family POTD/POTF. | + | + | + | Bacteria & Eukaryota & phages | No HGT observed | |

| KOG2143 | ||||||||||

| 89 | RmuC | PF02646 | (39) | Molecular function unknown. Involved in DNA recombination (143), neighborhood of metallopeptidases and MFS1 transporters | + | Bacteria (mostly γ-proteobacteria) | Lentisphaera araneosa (Lentisphaere) in a Oceanospirillales (Proteobacterial) clade, forms a clade together with Neptuniibacter caesariensis. Both bacteria were isolated from a surface water sample (144,145) | |||

| COG1322 | ||||||||||

| 90 | Uncharacterized conserved protein | COG5482 | New | Unknown | {2} | + | {1} | Bacteria (mostly α-proteobacteria) & phages | Ricinus communis (Plantae) forms a clade with a tumorogenic Agrobacterium radiobacter (Rhizobiales) within a Rhizobiales clade | |

| 91 | Predicted transcriptional regulator | COG1395 | New | The function is unknown but it likely binds nucleic acids. Harbors a HTH motif, co-occurs with a two-domain protein consisting of DUF1743 and tRNA_anti (PF01336) nucleic acid-binding OB-fold domain. | + | Archaea | No HGT observed | |||

| 92 | DUF1052 | PF06319 | Pfam | Co-occurs with HisKA and Lactamase_B or YkuD (PF03734) which also gives β-lactam resistance. | {1} | + | Bacteria (mostly α-proteobacteria) | An uncultured Acidobacterium within a Rhizobiales clade with Nitrobacter, Bradyrhizobium and Rhodopseudomonas palustris. Acidobacteria, Nitrobacter, Bradyrhizobium are soil related bacteria, but R. palustris is found in sea sediments | ||

| COG5321 | ||||||||||

| 3dnx | ||||||||||

| 93 | Sugar fermentation stimulation protein SfsA | PF03749 | (146) | Unknown, SfsA protein binds to DNA non-specifically (147). Connected with maltose metabolism (147). In γ-proteobacteria in the proximity of LigT and Pol A or with a C4-type zinc finger and nucleotidyltransferase domain. In Cyanobacteria co-occurs with transport proteins related to virulence. In Archaea with a MSF_1 transporter or Lactamase_B. | + | Bacteria (mostly Proteobacteria) | Plautia sali symbiont (unclassified bacterium) groups with a Pantoea sp. clade (γ-proteobacteria)a | |||

| COG1489 | ||||||||||

| 94 | NERD | PF08378 | (38) | Unknown, described as nuclease-related (38) | + | {2} | Bacteria | Planctomyces limnophilus (Planctomycetales) groups with Puniceispirillum marinum (α-proteobacteria). Mannheimia succiniciproducens (γ-proteobacteria) locates in a Neisseria (β-proteobacteria) clade. Clades with mixed taxonomic groups | ||

| 95 | DUF1626 | PF07788 | (36) | Unknown | + | + | Prokaryota | Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii (Nitrospirales) within a Cyanobacterial clade mostly C. raciborskii. Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii is bloom-forming and potentially toxic river cyanobacteria. T. yellowstonii was isolated form thermal vent water. Patchy distribution in Bacteria suggesting multiple HGT events | ||

| COG5493 | ||||||||||

| 96 | UPF0102, RPA0323 | PF02021 | Pfam | Is often found with a TP_methylase (PF00590) domain. Tetrapyrrole (Corrin/Porphyrin) Methylases use S-AdoMet in the methylation of diverse substrates. The genomic context is well conserved for each bacterial class. | + | + | Prokaryota | Cryptobacterium curtum (Actinobacteria) in a Clostridium cladea | ||

| COG0792 | ||||||||||

| COG4998 | ||||||||||

| 3fov | ||||||||||

| 97 | DUF1887 | PF09002 | Pfam | Occasionally co-occurs with phosphorylase superfamily PNP_UDP_1 (PF01048) (uridine phosphorylase) and zinc/cadmium/mercury/lead-transporting ATPase. | + | + | Prokaryota | Three M. smithii (Euryarchaeota) sequences form a clade with 2 sequences from Synechococcus sp. from Yellowstone (Cyanobacteria) and M. ruber (Thermales). Methanobrevibacter smithii is a methanogenic archeon highly resistant to antibiotics | ||

| 1xmx | ||||||||||

| 98 | DUF1016 | PF06250 | (39) | Co-occurs with restriction MTase, ResIII and ResI S domains, and mobile element domains (phage integrase, DDE). Might act as nucleic acid-binding element in restriction enzymes. | {1} | + | {3} | {2} | Bacteria | Trichoplax adhaerens (Plecozoa) groups with a Bacterioidales clade with two additional HGT transfered sequences: Rickettsia felis (α-proteobacteria) and Legionella longbeachae (γ-proteobacteria). Ricinus communis (Plantae) locates with a Burkholderiales clade harboring other unrelated taxa from γ-proteobacteria: Thioalkalivibrio sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Dickeya dadantii |

| COG4804 | ||||||||||

| 99 | DUF1703 | PF08011 | (36) | There are 9 DUF1703 proteins in Methanospirillum hungatei DSM 864. Some of them reside in the proximity of multiple PAS fold domains and CheY sensor related genes. In Bacterioidetes the genomic context is not conserved due to a duplication. | + | {1} | Bacteria (mostly Bacterioidetes) | Nine sequences from M. hungatei form a sister clade to a Proteobacteria clade. This clade is grouped together with a Treponema clade. The rest of the tree belongs to Bacterioidetes | ||

| 100 | DUF4143 | COG1373, PF13635 | Pfam | Unknown | + | + | Prokaryota | Ilyobacter polytropus (Fusobacteriales) forms a clade with C. sticklandii (Clostridiales). Ilyobacter polytropus was isolated from marine anoxic mud | ||

| 101 | DUF511 | PF04373 | (11) | Unknown | + | Bacteria | Unrelated sequences from Fibrobacterales, Chlorobiales, Clostridiales, Flavobacteriales and Bacteroidales on a Proteobacteria tree | |||

| COG2958 | ||||||||||

| 102 | DUF2887 | PF11103 | (11) | Unknown. Co-occurs with transport related proteins. | + | Bacteria (Cyanobacteria) | Methylococcus capsulatus and Beggiatoa sequences are found within a Cyanobacteria clade | |||

| 103 | Restriction endonuclease-like fold superfamily protein | 3ijm | PDB | Unknown | + | Spirosoma linguale (Cytophagales) | No HGT observed | |||

| 104 | DUF1853 | PF08907 | (11) | Unknown. The genomic context is conserved within bacterial families. | + | Bacteria (mostly Proteobacteria) | Anacystis nidulans (Cyanobacteria), Planctomycetes and Flavobacteria within a Proteobacteria clade | |||

| COG3782 | ||||||||||

| 105 | UL24 | PF01646 | (36) | The molecular mechanism is unknown however the UL24 protein is able to induce G2 cell-cycle arrest (148), disperse nucleolin (149) and alter the nuclei. The PD-(D/E)XK motif preservation is crucial for these functions (150). | + | + | Herpesvirales | No HGT observed | ||

| 106 | DUF506 | PF04720 | (36) | Unknown | Plantae | No HGT observed | ||||

| Green algae | ||||||||||

| 107 | TT1808, DUF820, Uma2 | PF05685 | (39) | Predicted endonuclease. In Cyanobacteria the genomic context is well conserved. In γ-proteobacteria the context is not conserved and involves mobile elements suggesting recent mobility and/or acquisition. | + | Bacteria | Proteobacteria sequences within Firmicutes or Cyanobacteria clades. Very long branches. Multiple transfer | |||

| COG4636 | ||||||||||

| 1wdj, 3ot2 | ||||||||||

| 108 | DUF1780 | PF08682 | SCOP | Unknown. Well conserved context | + | Bacteria (Pseudomonadales) | No HGT observed | |||

| 1y0k | ||||||||||

| 109 | DUF2130 | PF09903 | Pfam | Unknown | + | {1} | Bacteria | Parascardovia denticolens and Scardovia inopinata (Bifidobacteriales) in a Lactobacillaes clade. One archeon M. paludicola | ||

| COG4487 | ||||||||||

| 110 | DUF2726 | PF10881 | Pfam | Unknown. In Fusobacteria DUF2726 proteins are surrounded by mobile elements. This feature is less pronounced in other bacteria. | + | + | Bacteria | Multiple transfers. Pirellula staleyi (Plantomyces) forms a clade with Anaerolinea thermophila (Chloroflexi) | ||

| 111 | RAP domain | PF08373 | Pfam | Unknown. Initially claimed to bind RNA and abundant in Apicomplexans, present in proteins involved in mitochondrial stress sensing (151) and plant immunity (152). | {1} | + | Eukaryota | Parachlamydia acanthamoebae is located with a lycophyte, Selaginella moellendorffii, long branches | ||

| 112 | YaeQ | PF07152 | (153) | Located with bleomycin resistance (Glyoxalase) and Aceltyltransf_1 (GNAT). In P. aeruginosa biofilms a YaeQ mutant has decreased expression of genes encoding NADH dehydrogenase activity and cobalamin biosynthetic process and increased expression of secretion and pathogenesis genes (e.g. exoY, pscU and exsC). This mutant has biofilm-exclusive tobramycin fitness advantages. Tobramycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic. YaeQ compensates (154) or does not (155) the hemolysin transcription elongation protein RfaH function. | + | Bacteria (Proteobacteria) | Nitrospira defluvii on a Proteobacteria tree forms a clade with Leptothrix cholodnii. Ricinus communis (Plantae) groups with Methylotenera mobilis | |||

| COG4681 | ||||||||||

| 2ot9, 2g3w | ||||||||||

| 3c0u | ||||||||||

| 113 | PDDEXK_2 | PF12784 | Pfam | Putative transposase | + | {1} | Bacteria | Phylogeny not resolved | ||

| 114 | PDDEXK_3 | PF13366 | Pfam | Unknown | + | + | + | Prokaryota & Viruses | Multiple transfers, mixed clades for Bacteria and Archaea or different Bacterial divisions | |

| 115 | PDDEXK_4 | PF14281 | Pfam | Unknown | + | + | {1} | Prokaryota | Ricinus communis (Plantae) is present in a Proteobacteria clade. Parabacteroides merdae a human gut bacterium found also in wounds forms a clade with a bacteria from termite hindguts Treponema primitia | |

| 116 | DUF4263 | PF14082 | New | Unknown | {1} | + | {2} | {1} | Bacteria | Populus balsamifera subsp. trichocarpa (Plantae) sequence forms a clade with a non-pathogenic metal resistant bacterium Ralstonia metallidurans |

| 117 | DUF3883 | PF13020 | New | Unknown | + | + | + | Eukaryota & Prokaryota | Phylogeny not well resolveda | |

| 118 | DUF4420 | PF14390 | New | Putative transposase | + | {2} | Bacteria | Methanoplanus petrolearius (Euryarchaeota) and an uncultured archaeon locate within a Bacteria (Bacterioidetes/Actinobacteria) clade. Multiple transfers | ||

| 119 | Replic_Relax | PF13814 | New | Plasmid replication (156) and plasmid DNA relaxation (157) | {1} | + | Bacteria (Bacillus/Clostridium & Actinobacteria) | Streptococcus (Lactobacillales) locates within an Actinobacteria clade. Paenibacillus (Bacillales) sequence is found in an Actinobacteria clade | ||

| 120 | Dam-replacing protein | PF06044 | (158) | DNA adenine methyltransferase replacing protein (DRP), a restriction endonuclease (158) | {2} | + | {3} | Bacteria | Patchy distribution possibly due to multiple transfers | |

| 121 | TBP-interacting protein | 2czr | (159) | A family of proteins, that interact with TATA-binding protein (TBP) (159). | + | Archaea (Thermococcales) | No HGT observed | |||

Groups include closely related families and structures that share relatively high sequence similarity detectable with PSI-BLAST and RPS-BLAST.

aThe tree was not rooted due to dubious position of the rooting sequence.

The curly brackets in the taxonomy columns indicate the number of sequences if kingdom is represented only by a few sequences.

Newly identified PD-(D/E)XK families

According to extensive database and literature searches 11 groups (3, 5, 14, 15, 26, 90, 91, 116, 117, 118, 119; Table 1) include proteins not annotated previously to PD-(D/E)XK fold superfamily. Five of them embrace completely uncharacterized proteins from DUF4420 (PF14390), DUF3883 (PF13020), DUF4263 (PF14082), COG5482 and COG1395 families. The remaining six newly detected groups cover functionally studied protein families which, however, lacked fold assignment. These include restriction endonucleases Tsp45I (PF06300), HaeII (PF09554), Eco47II (PF09553), ScaI (PF09569) and HpaII (PF09561) and Replic_Relax (PF13814)—a predicted transcriptional regulator. We studied in detail all newly detected families to hint at additional functional information. COG1395, COG5482 and Replic_Relax (PF13814) usually occur in a fusion with HTH DNA-binding domains, which suggests their role in transcription regulation. DUF4263 (PF14082) and DUF3883 (PF13020) are often present in proteins encoding an ATPase domain. Additionally, DUF3883 appears in a variety of domain architectures, including fusions with helicases, TF domains, protein kinases and MTases. Details of identification of new families are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. One should note that only two of them were assigned to the PD-(D/E)XK superfamily with Meta-BASIC scores above confidence threshold of 40.

Structure analysis

A comprehensive analysis of the identified structures allows us to better understand how the PD-(D/E)XK fold adapt to particular functions. The structural analyses are critical to further detection and classification of PD-(D/E)XK proteins and provide a solid background for rational hypotheses about structurally unstudied families. In the next section we describe multiple aspects of structural changes that blur a commonly recognized image of the restriction endonuclease-like proteins.

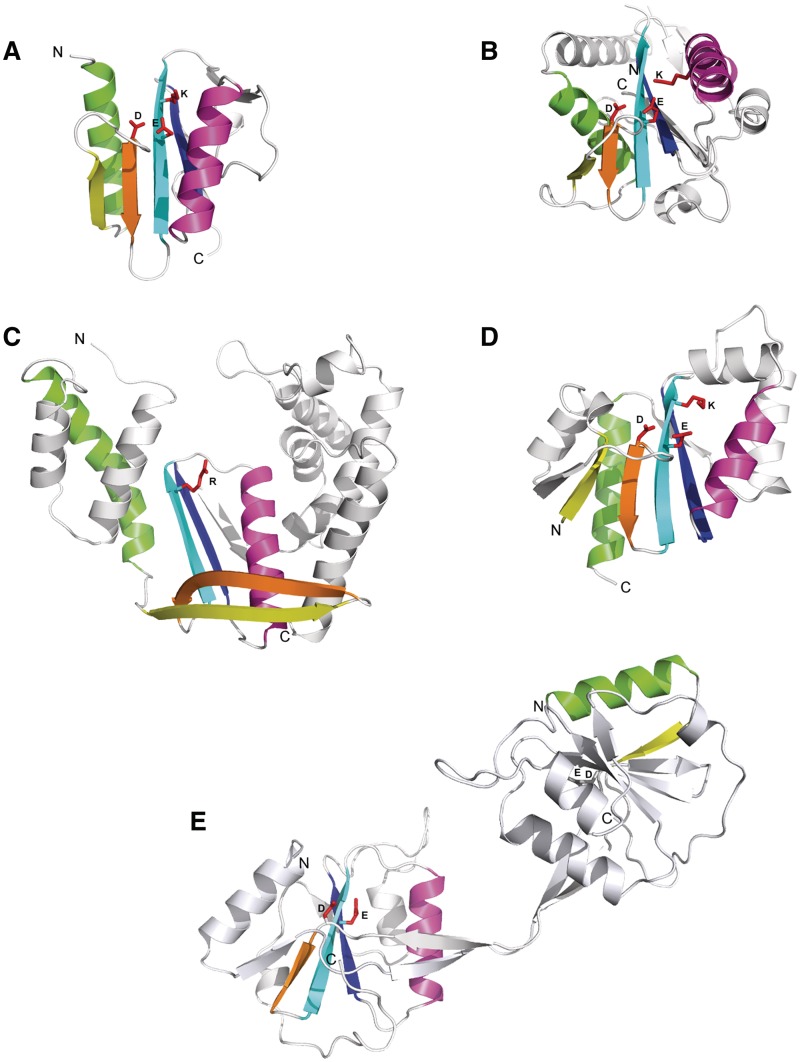

Core variability

The structural core of PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase fold includes only six major elements: four β-strands and two α-helices (Figure 3A). We believe that this minimalism contributes to structural diversity of the superfamily. The first and the second core β-strands can embrace only a few residues (pdb|1y0k, Figure 3B), hardly forming a well-defined part of the central β-sheet. On the other hand, they can also be very long, forming a hairpin, which barely interacts with the rest of the β-sheet and keeps the remaining region bent away from the core structure (RecBCD nuclease, pdb|1w36 chain C, Figure 3C). Even if all core secondary structures are present, their spatial arrangement may still vary significantly. In a canonical PD-(D/E)XK enzyme α-helices remain in a roughly parallel orientation, whereas in the Pa4535 protein (pdb|1y0k, Figure 3B) they are almost perpendicular. In addition, we also observed circular permutations, e.g. in HJC resolving enzyme (pdb|1j22), where the first core α-helix is formed by the C-terminal sequence region, while N-termini encodes the first core β-strand (Figure 3D). Finally, the repertoire of structural variation within restriction endonuclease-like proteins is additionally enriched by domain swapping. For instance, bacteriophage T7 endonuclease I (pdb|2pfj) exchanges the first core α-helix and the first core β-strand between separate chains, both forming catalytically active, dimerized domains (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Examples of structural diversity in the PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase superfamily. (A) typical PD-(D/E)XK enzyme (Holiday junction resolvase, Pyrococcus furiosus, pdb|1gef); (B) highly diverged structure with short first β-strand and perpendicular orientation of core α-helices (Pa4535 protein, P. aeruginosa, pdb|1y0k); (C) structure deterioration and the loss of active site (RecC, E. coli, pdb|1w36C); (D) circular permutation of the first core α-helix (Hef endonuclease, Pyrococcus furiosus, pdb|1j22); (E) domain swapping (endonuclease I, Enterobacteria phage T7, pdb|2pfj). Active site PD-(D/E)XK signature residues are shown as red sticks.

Insertions to core

In order to investigate the capabilities of the fold to handle additional structural elements we studied the structures of known PD-(D/E)XK proteins. The PD-(D/E)XK structural core is often decorated with plenty of insertions that tune the substrate-binding capabilities or enable protein-protein interactions (Supplementary Figure S1). The structure of Bacillus subtilis RecU resolvase (pdb|1zp7) is a remarkable example of tweaking canonical restriction endonuclease core for a specific function. It has a characteristic stalk formed by the first and the second β-strands extensions that fits into a four-way junction central region and provides a scaffold for substrate destabilizing interactions.

Interestingly, using topology based-searches we identified PD-(D/E)XK core fold in many unrelated structures (Supplementary Figure S2). The so called ‘Russian-doll’ effect is discussed in more detail in Supplementary Materials [PD-(D/E)XK fold in other unrelated structures].

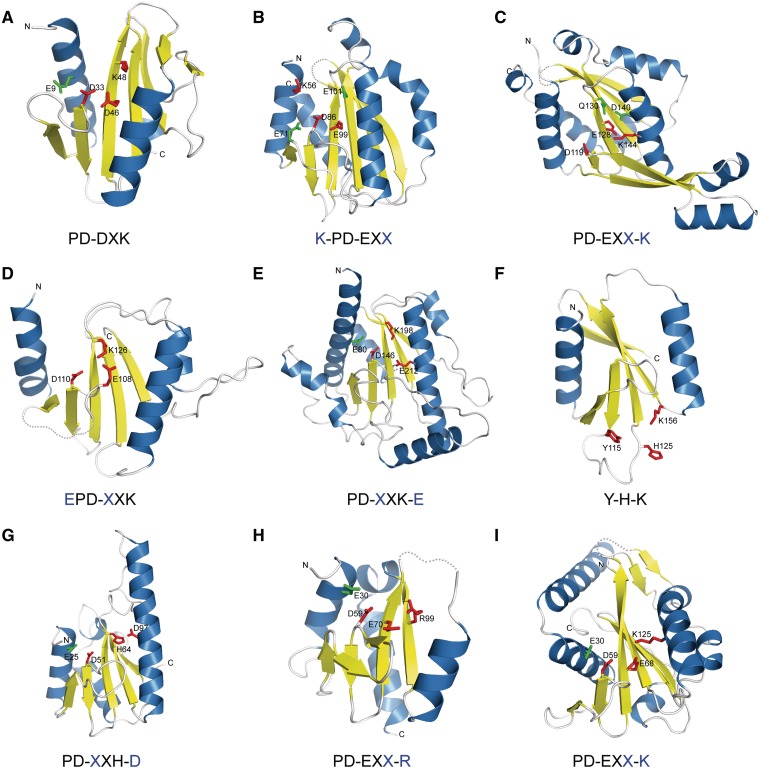

Active site variation

A PD-(D/E)XK active site residues fingerprint varies between the families (Figure 4). For instance, the signature motif proline can be replaced by any residue (mainly hydrophobic). Having a vast collection of PD-(D/E)XK proteins we analyzed possible alterations to the archetypical active site architecture. Such information is fundamental for further effective searches for new, putative PD-(D/E)XK enzymes within uncharacterized protein families. The canonical active site is formed by aspartic acid placed in the N-termini of the second core β-strand and glutamic acid, followed by lysine from the third β-strand, placing the carboxyl and amino groups in a suitable spatial arrangement. Interestingly, the glutamic acid and lysine may be shifted into nearby structural elements, tending however to position their chemical groups towards the active site and preserving its catalytic functionality (10). We observed such migration in several structures: (i) Cfr10I restriction endonuclease (pdb|1cfr), where glutamic acid migrates from the third β-strand to the adjacent, second core α-helix resulting in the PD-XXK-E motif; (ii) EcoO109I restriction enzyme (pdb|1wtd), where glutamic acid E moves from the expected position 124 into position 108 and now precedes aspartic acid from the PD motif (motif EPD-XXK); (iii) Pa4535 structural genomics hypothetical protein (pdb|1y0k), where lysine migrates from the expected position 70 into position 125 in the adjacent second core α-helix (motif PD-EXX-K). Interestingly, tRNA splicing endonucleases acquired a different active site within restriction endonuclease-like fold. These enzymes conserve three catalytic residues: tyrosine, histidine and lysine (Y115, H125, K156 in a Methanococcus jannaschii endonuclease) that form an active site located on the opposite edge of the central β-sheet. Even though tRNA-splicing endonucleases share a common PD-(D/E)XK fold, they eventually recognize a different substrate and possess a distinct catalytic mechanism.

Figure 4.

Active site variations observed in the PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase superfamily structures. Observed variant of ‘PD-(D/E)XK’ signature motif is given below each structure with residue migration denoted in blue. (A) archaeal HJC resolvase (P. furiosus, pdb|1gef); (B) BamHI restriction endonuclease (Oceanobacter kriegii, pdb|3odh); (C) BstYI restriction endonuclease (Geobacillus stearothermophilus, pdb|1sdo); (D) EcoO109I restriction endonuclease (E. coli, pdb|1wtd); (E) Bse634I restriction endonuclease (Geobacillus stearothermophilus, pdb|1knv); (F) tRNA splicing endonuclease (Methanocaldococcus jannaschii, pdb|1a79); (G) Vsr repair endonuclease (E. coli, pdb|1cw0); (H) a putative endonuclease-like protein (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, pdb|3hrl); (I) Pa4535 protein (P. aeruginosa, pdb|1y0k).

Sequence analyses

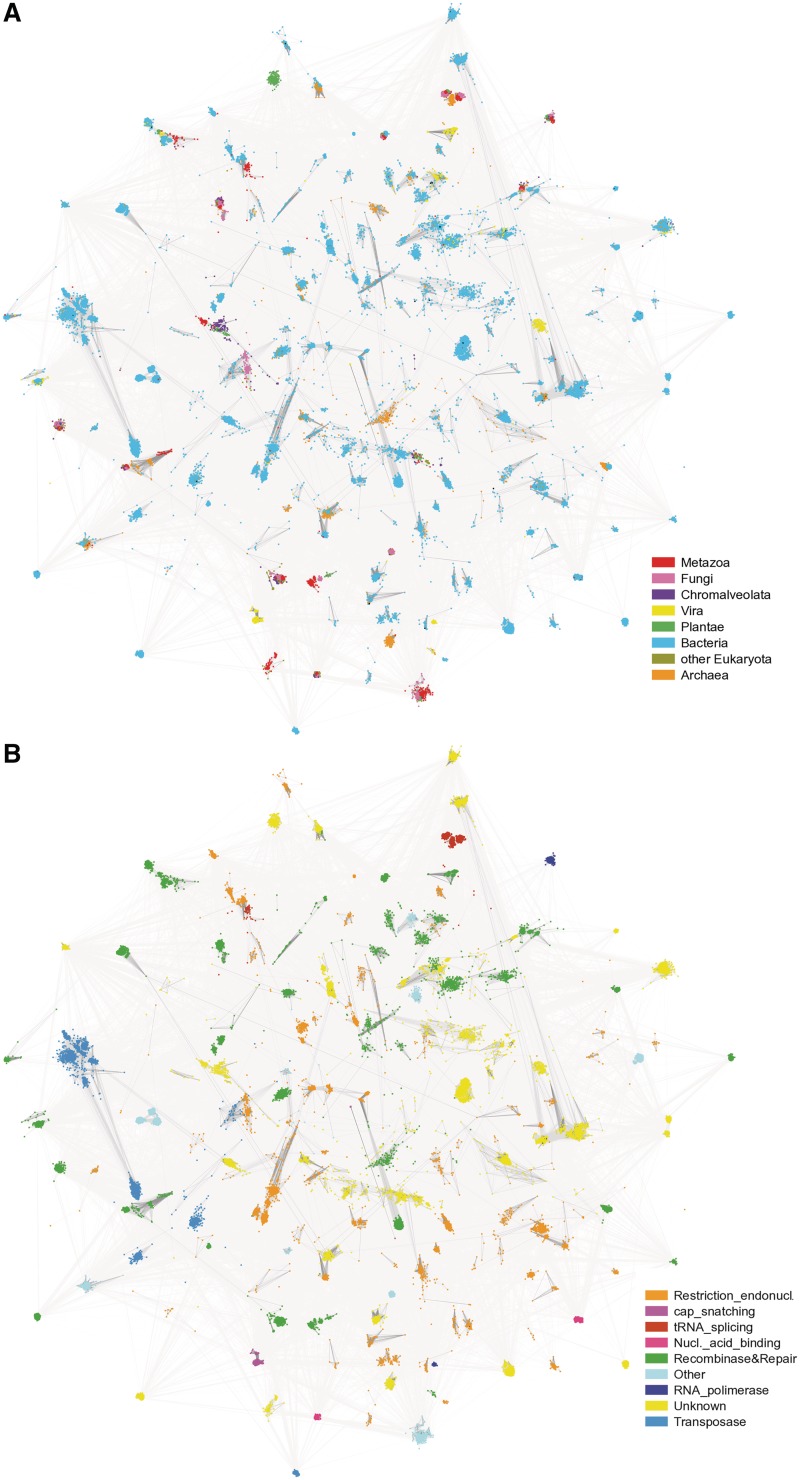

Although most of the PD-(D/E)XK proteins have a nuclease activity, they may also perform other diverse functions. Adaptation to a particular functional niche may involve the presence of additional protein domains encoded separately or together with the PD-(D/E)XK domain. Some functions are restricted to a certain taxonomic unit while others are widely distributed across the tree of life. In order to gain a general overview of sequence similarities, all 21 911 protein sequences were clustered with CLANS. The obtained clustering was colored based on both sequence taxonomic distribution and protein function (Figure 5). One should note that restriction endonucleases exhibit high sequence divergence, whereas house-keeping genes form tight clusters. Bacterial sequences are present all over the sequence space in contrast to viral sequences which appear only in a handful of sequence groups. Our analysis of taxonomic distribution, genomic context and domain architecture of PD-(D/E)XK proteins should help understand their biological relevance.

Figure 5.

CLANS clustering of 21 911 sequences belonging to 121 clades of the PD-(D/E)XK superfamily. The image was drawn with an in-house script based on CLANS run files. (A) illustrates the taxonomic distribution of analyzed sequences and (B) summarizes their functional annotation.

Domain architecture

We extensively studied a domain organization for all collected PD-(D/E)XK proteins that might provide a broader view on the diversity of functional associations in this superfamily and also hint at specific functions for uncharacterized and poorly annotated proteins. In particular, we identified fused protein domains, internal repeat regions, coiled-coils and transmembrane elements. We observed various interesting domain arrangements that adjust the PD-(D/E)XK protein function to a specific role (Supplementary Figure S3), although most of the analyzed proteins harbor a single PD-(D/E)XK domain. Altogether, we identified 535 fused protein domains of distinct functions in 79 PD-(D/E)XK groups (Supplementary Table S4). Some of the most interesting and newly observed domain architectures are described in Supplementary Materials [Domain architecture], whereas a complete list of domain arrangements is included as Supplementary Figure S3.

Taxonomic distribution and horizontal gene transfers

The abundance of possible functions within PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterase proteins raises a question of the origin of these enzymes. In order to gain some insight into evolutionary history of these proteins we looked at the taxonomic distribution of the 121 PD-(D/E)XK groups (Table 1 and Supplementary Dataset S2). The housekeeping genes such as: HJC resolvase, RecBCD or tRNA intron endonuclease exhibit a broad taxonomic distribution. On the other hand, restriction endonucleases are usually unevenly distributed among a handful of specific orders of Prokaryota. Some PD-(D/E)XK proteins display a special taxonomic distribution. For example, the occurrence of Sen15 tRNA, a subunit of a splicing endonuclease is limited to Amebozoa and Ophistokonta. Noteworthy, in plants only two pre-tRNA molecules undergo splicing (tRNATyr and tRNAMet) (55) and the observed introns are significantly related in structure. The remaining Eukaryotic lineages could display alternative modes of tRNA intron endonuclease action. NARG2 and Pet127 proteins, also absent in plants, are known to participate in vital processes (32,56), but their molecular function is unknown. Pet127 is a mitochondrial protein involved in mtRNA polymerase regulation and mitochondrial mRNA maturation (32). The absence of Pet127 in plants raises a question of the differences in mtRNA polymerase performance and mtRNA maturation in these organisms. Initial studies on NARG2 claimed it is restricted to higher vertebrates and is involved in development (56). For example, human NARG2 protein is involved in the regulation of brain cortical gray matter thickness (57). Importantly, we found NARG2-like proteins to be also present in Amebozoa and Metazoa.

We observed Horizontal Gene Transfers (HGTs) in the majority of the PD-(D/E)XK groups. In the families that span multiple proteins originated from one taxon, together with a protein from evolutionary distant species, the HGT is the most parsimonious hypothesis which explains such uneven distribution. Derived tree topologies are often obscured by long and deep, unresolved branches. The distorted clades occasionally encompass sequences of mixed taxonomic origin and may intriguingly group together Archaea and Bacteria sequences. In 1996 Jeltsch and Pingoud (22) hypothesized that HGT affected the distribution and evolution of type II restriction enzymes. Our results corroborate their hypothesis. Patchy taxonomic distribution of restriction enzymes usually covers many unrelated taxonomic ranges, but is limited to a handful of representatives of each taxon. House-keeping genes such as HJC, Vsr do not transfer laterally. The event possibilities for each of the 121 PD-(D/E)XK clades are summarized in Table 1. In Supplementary Materials (Taxonomic distribution and HGTs), we describe some of the most interesting HGT events, with special attention paid to human pathogenic bacteria, and Prokaryota to Eukaryota transfers.

Summarizing, the patchy, narrow, or wide taxonomy distribution along with multiple HGT events greatly contribute to the complexity of the world of PD-(D/E)XK proteins that significantly vary in their structural features and display a wide range of domain architectures.

DISCUSSION

The PD-(D/E)XK proteins play important roles in many vital processes including the nucleic acid maintenance. Probably for this reason they are found in all living organisms. Across the superfamily, these proteins display a broad collection of general scaffold alterations which tweak their basic function to perform more specialized actions. The abundance of functions and distant evolutionary distances between particular PD-(D/E)XK families encouraged us to split the whole set of identified proteins into groups of sequences displaying obvious homology in terms of sequence comparison (Table 1). We expected such grouping to reflect the differences between functions and taxonomic distributions. Indeed, most of the defined groups show very coherent functions. The restriction enzymes and tRNA splicing endonucleases may be one of the most prominent examples here. However, some of the groups are blurred in terms of sequence similarity and cover many, yet connected functions including helicases, repair endonucleases, exonucleases and others. The difficulty of reproducing functional partition in our grouping procedure is 2-fold. The consensus sequence definitions that were used in our search included COG and KOG sequences which tend to cover multiple domains. This might lead to extended sequence alignment and boost of sequence similarity measure between distinct protein families. The other reason for grouping deficiency is the complex biological context of the analyzed proteins, especially that observed for housekeeping enzymes, like structure-specific repair nucleases. The alternative functions may emerge relatively fast, because homologous proteins may easily gain a new activity by fusing or interacting with unconventional protein domains. In our opinion, the precision of the grouping also strongly depends on the protein family concept which remains unclear.

PD-(D/E)XK phosphodiesterases exhibit great variability in sequence and structure. There are potentially two major reasons for that. These enzymes are involved in a variety of biological processes which require a very diverse range of substrates to be recognized in both the sequence- and structure-specific manner. High sequence dissimilarity, especially between restriction endonucleases is the result of evolutionary arms race between phages and bacteria (160).

A detailed analysis of insertions to the common conserved core observed in the existing structures across multiple PD-(D/E)XK families inspire a reflection that the majority of structural diversities are focused on the substrate-binding side (Supplementary Figure S1). The opposite side to the active site remains relatively unchanged.

The PD-(D/E)XK fold can be described as gregarious (161) referring to its presence in several evolutionary unrelated protein structures. N-acetyltransferases, lipases, dehydrogenases containing the PD-(D/E)XK domain as a substructure represent different folds (even fold classes) according to SCOP database. This finding provides novel challenges to protein structure classification that should probably describe structural space for the α/β sandwich architecture as the continuum rather than distinct folds. This also sheds new light on the possible mechanisms of fold change in the evolution of protein structure through the structural drift (162), and may also provide some hints about the evolutionary history of these proteins suggesting that some of them might have evolved from a common ancestor.

We observed many rare multiple domain architectures what is a general feature of sequence space (163). We identified PD-(D/E)XK domains that co-occur with the domains acting on nucleic acids, including methylases, helicases, resolvases, RNAse H, excision repair endonucleases, chromatin remodelers, or DNA ligases. These domain architectures follow the main functional niche occupied by nucleases. However, proteins with the PD-(D/E)XK domain can also be involved in protein structure maintenance. An interesting example is provided here by a hypothetical protein from Vitis vinifera discussed above (gi|147821195) which may be involved in both nucleic acid and histone protein structure upkeep, or Rai 1 from Polysphondylium pallidum (gi|281203778) followed by COBRA domain, a BRCA1 related protein that contributes to chromatin remodeling. Also intriguing domain association includes nucleases co-occurring with kinases. This might suggest that such proteins are somehow involved in triggering the response to nucleic acid aberrancies.

We observed the PD-(D/E)XK groups limited to one Archaea group (ThaI REase in Thermoplasmata), present in a few unrelated taxa (BgII REase) or conserved and essential in all domains of life (Dem1/EXO5). This phenomenon might be explained by the different roles played by conserved and patchy distributed proteins. The former are rarely transferred and inherited vertically, their mutations are strongly deleterious. In consequence, they appear in broad taxonomic groups in a fixed number of copies per genome and in all representatives of a taxon. The latter offer additional adaptive advantages, useful in a defined ecological niche and are frequently transferred laterally rather than inherited. The reported cases of HGT between human pathogenic bacteria or from bacteria to Eukaryotes additionally exemplify the complex evolution of the PD-(D/E)XK proteins.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The aim of this project was to identify the most complete set of proteins retaining the PD-(D/E)XK fold. Such a collection is indispensable for a comprehensive view on this fold and enables further insight into detailed biological functions, exact substrates and the molecular mechanisms undergoing in the processes connected with nucleic acid cleavage.

The large and extremely diverse PD-(D/E)XK superfamily covers both specialized and multifunctional enzymes, as well as proteins that lost their enzymatic activity and now serve as structural or nucleic acid-binding units. Some of the PD-(D/E)XK fold families are restricted to a single bacterial family while others are present in all living organisms. The PD-(D/E)XK domains may co-occur solely, with one additional protein domain or in elaborated domain contexts. Moreover, some of the PD-(D/E)XK families harbor proteins appearing once per genome and others can display an increased number of copies. In humans the PD-(D/E)XK proteins can be linked to severe neurological diseases and may increase the probability of cancer.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–4, Supplementary Figures 1–4, Supplementary Materials, Supplementary Datasets 1–2 and Supplementary References [164–199].

FUNDING

EMBO Installation, Foundation for Polish Science (Team, Focus), Ministry of Science and Higher Education [N N301 159435, 0376/IP1/2011/71]; European Regional Development Fund under Innovative Economy Programme [POIG.01.01.02-14-054/09-00]; European Social Fund [UDA-POKL.04.01.01-00-072/09-00] grants. Funding for open access charge: Waived by Oxford University Press.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Orlowski J, Bujnicki JM. Structural and evolutionary classification of Type II restriction enzymes based on theoretical and experimental analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3552–3569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belfort M, Weiner A. Another bridge between kingdoms: tRNA splicing in archaea and eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hickman AB, Li Y, Mathew SV, May EW, Craig NL, Dyda F. Unexpected structural diversity in DNA recombination: the restriction endonuclease connection. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:1025–1034. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahlroth SL, Gurmu D, Schmitzberger F, Engman H, Haas J, Erlandsen H, Nordlund P. Crystal structure of the shutoff and exonuclease protein from the oncogenic Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. FEBS J. 2009;276:6636–6645. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravind L, Makarova KS, Koonin EV. SURVEY AND SUMMARY: holliday junction resolvases and related nucleases: identification of new families, phyletic distribution and evolutionary trajectories. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3417–3432. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ban C, Yang W. Structural basis for MutH activation in E.coli mismatch repair and relationship of MutH to restriction endonucleases. EMBO J. 1998;17:1526–1534. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiang S, Cooper-Morgan A, Jiao X, Kiledjian M, Manley JL, Tong L. Structure and function of the 5′–>3′ exoribonuclease Rat1 and its activating partner Rai1. Nature. 2009;458:784–788. doi: 10.1038/nature07731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Todone F, Weinzierl RO, Brick P, Onesti S. Crystal structure of RPB5, a universal eukaryotic RNA polymerase subunit and transcription factor interaction target. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6306–6310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishino T, Komori K, Ishino Y, Morikawa K. X-ray and biochemical anatomy of an archaeal XPF/Rad1/Mus81 family nuclease: similarity between its endonuclease domain and restriction enzymes. Structure. 2003;11:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]