Background: Flavodiiron proteins encoded by the flv4-2 operon are photoprotective for photosystem II, but their regulation of expression has remained enigmatic.

Results: Expression of flv4-2 is controlled jointly by NdhR and the antisense RNA As1_flv4, whereas As1_flv4 is controlled by an AbrB-like factor.

Conclusion: As1_flv4 provides a safety threshold preventing premature expression.

Significance: Regulatory networks controlling photosynthetic photoprotection are highly complex.

Keywords: Antisense RNA, Cyanobacteria, Gene Expression, Photosynthesis, Photosystem II, Ci Regulation, Flavodiiron Proteins, Noncoding RNA

Abstract

The functional relevance of natural cis-antisense transcripts is mostly unknown. Here we have characterized the association of three antisense RNAs and one intergenically encoded noncoding RNA with an operon that plays a crucial role in photoprotection of photosystem II under low carbon conditions in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Cyanobacteria show strong gene expression dynamics in response to a shift of cells from high carbon to low levels of inorganic carbon (Ci), but the regulatory mechanisms are poorly understood. Among the most up-regulated genes in Synechocystis are flv4, sll0218, and flv2, which are organized in the flv4-2 operon. The flavodiiron proteins encoded by this operon open up an alternative electron transfer route, likely starting from the QB site in photosystem II, under photooxidative stress conditions. Our expression analysis of cells shifted from high carbon to low carbon demonstrated an inversely correlated transcript accumulation of the flv4-2 operon mRNA and one antisense RNA to flv4, designated as As1_flv4. Overexpression of As1_flv4 led to a decrease in flv4-2 mRNA. The promoter activity of as1_flv4 was transiently stimulated by Ci limitation and negatively regulated by the AbrB-like transcription regulator Sll0822, whereas the flv4-2 operon was positively regulated by the transcription factor NdhR. The results indicate that the tightly regulated antisense RNA As1_flv4 establishes a transient threshold for flv4-2 expression in the early phase after a change in Ci conditions. Thus, it prevents unfavorable synthesis of the proteins from the flv4-2 operon.

Introduction

Regulatory RNAs are key transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression in all domains of life. In plants, small RNA-based mechanisms control almost all aspects of plant biology, including chromatin structure, genome stability, gene expression, and defense. The functions and phylogenetic distribution of plant microRNAs, one particular class of RNA regulators, have been studied comparatively well (for a review, see Ref. 1), whereas the functions of longer noncoding RNAs are only beginning to emerge (2). Transcripts, which originate from the reverse complementary strand of an annotated gene and hence fully or partially overlap with their respective mRNAs, are known as cis-natural antisense transcripts or antisense RNAs (asRNAs).3 Natural asRNAs are abundant in the plant nuclear genome (3, 4). Plant asRNAs have been more frequently observed to be associated with mRNAs of nucleus-encoded plastid and mitochondrial proteins than with other eukaryotic mRNAs (5), a fact that may be taken as a hint for the possible role of bacterial asRNAs during evolution and even after endosymbiosis. Indeed, recent observations for plant chloroplasts indicated asRNAs to be associated to 35% of all genes (6).

In cyanobacteria, the evolutionary ancestors of plant chloroplasts, asRNAs summing up to 26% of all genes for the unicellular Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis) (7, 8) and to 39% of all genes in the nitrogen-fixing Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (hereafter Anabaena) (9) were reported. However, the functional relevance of specific antisense transcripts in plants, chloroplasts, and bacteria has barely been addressed. In cyanobacteria, the functions of only two asRNAs have been studied in molecular detail thus far. In Anabaena, furA, the gene for the ferric uptake regulator, is covered by a long asRNA (10) whose knock-out mutation results in an iron deficiency phenotype (11). In Synechocystis, the 177-nt asRNA IsrR controls the expression of isiA, which encodes the iron stress-induced protein A, in a co-degradation mechanism (12).

Cyanobacteria are often challenged by changes in biotic and abiotic factors in their natural environments. In particular, changes in cellular functions triggered by fluctuations in the availability of inorganic carbon (Ci) have been a subject of studies for years (13–23). Most striking is the induction of the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) in cyanobacterial cells after a shift from high (>1% CO2 in air) to low (atmospheric 0.038% CO2 in air) levels of Ci. By coordinated action of different CCM components, comprising specialized Ci uptake mechanisms and the Rubisco-containing carboxysomes, cyanobacteria manage to lower the CO2 compensation point and thus overcome the otherwise limiting Ci availability (for reviews, see Refs. 24–27). Furthermore, flavodiiron (Flv) proteins have recently been shown to be involved in the low carbon (0.038% CO2 in air; LC) acclimation process (28–30). The fully sequenced (31) cyanobacterial model organism Synechocystis contains four genes encoding the proteins Flv1, Flv2, Flv3, and Flv4. The expression of the flv2, flv3, and flv4 genes becomes up-regulated under LC conditions with flv2 and flv4 showing the strongest induction (16, 20, 28). Although the Flv1 and Flv3 proteins participate in the Mehler-like reaction (29, 32, 33), the Flv2 and Flv4 proteins were demonstrated to have a crucial role in photoprotection of photosystem II (PSII) under LC conditions (28). We have shown recently (30) that under these conditions the small membrane protein Sll0218, which is also encoded by the flv4-2 operon, stabilizes the PSII dimer and enables the Flv2/Flv4 heterodimer to accept electrons from PSII. Thus, the products of the flv4-2 operon provide β-cyanobacteria with a unique and novel photoprotection mechanism. Despite numerous studies and continuous progress (15, 16, 18, 20, 23, 34–36), the understanding of the Ci-controlled gene expression dynamics is still incomplete.

Here we report the identification of three asRNAs and one noncoding RNA (ncRNA) associated with the flv4-2 operon. These transcripts were primarily detected by microarray analysis (7) and 454 sequencing (8). We verified the existence of these ncRNAs by Northern blotting and characterized the asRNA As1_flv4 in more detail. The inversely correlated accumulation of As1_flv4 transcript with the transcripts and proteins from the flv4-2 operon and the results obtained from artificial modulation of As1_flv4 levels suggest a stoichiometric function of As1_flv4 to control the expression of the flv4-2 operon according to the environmental Ci availability. Furthermore, the direct or indirect repression by the AbrB-like transcriptional regulator Sll0822 and the control of the promoter activity by the Ci level support the assumption that ncRNAs play a significant role in the Ci-regulatory network in Synechocystis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The glucose-tolerant strain of cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, served as the WT. Cultivation of mutants was performed at 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin and 20 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, respectively. For the experiments, axenic cultures of the cyanobacteria were grown photoautotrophically under 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (white light) at 30 °C. Cells were cultivated in BG-11 medium (pH 7.5) and aerated by shaking in the presence of CO2-enriched air (3% CO2 in air; high carbon (HC)) or ambient air CO2 (LC). In the case of the LC shift experiment, the cells were collected by centrifugation (2 min at 1730 × g at room temperature) and resuspended in fresh BG-11, and the OD750 measured with a Spectronic Genesys 2 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI) was adjusted to 0.8. After precultivation at HC conditions for 1 h, cultures were transferred to LC conditions. In analogous experiments, cells were aerated directly by continuous bubbling with LC or HC.

For the asRNA overexpression experiments, the two overexpression mutants As1_flv4(+)/2 and As1_flv4(+)/3 and a control strain (mutant in spkA) were precultivated in Cu2+-containing BG-11 medium and bubbled with HC. For induction of petJ promoter activity by Cu2+ depletion (43), the cells were spun down and washed with and resuspended in Cu2+-free BG-11 medium. Subsequently, cultures were treated as described above.

Generation of Promoter Probe Strains

300- and 700-nt promoter regions of the genes encoding the asRNA As1_flv4 and the flv4-2 operon, respectively, were amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA and specific primers (supplemental Table S1). After digestion with KpnI, the respective promoter fragment was ligated into the unique KpnI site of the promoter test vector pILA (37). The vector pILA allows transcriptional fusion of the promoter sequence with the luxAB genes and its stable integration into the chromosome at a neutral site (37). Plasmids with correct promoter insertion direction relative to the reporter genes were selected for subsequent transformation of Synechocystis. Completely segregated clones were checked by PCR analysis as described (19) and subsequently used for promoter activity measurements.

Promoter Activity Measurements

1-ml cell aliquots were taken at selected time points from shaking cultures with an OD750 of 0.5. Subsamples of 100 μl were transferred in triplicate to white 96-well microtiter plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To start the measurement, 100 μl of 2 mm decanal ready-to-use solution was added, and the plate was immediately placed into the plate reader (Wallac Victor 2 1420 multilabel counter, PerkinElmer Life Sciences). 100 mm decanal stock solution was prepared in methanol and freshly diluted with BG-11 for 2 mm decanal ready-to-use solution. Bioluminescence was measured for 30 min at 25 °C. The maximum light emission (around 10 min after the start) was used as the bioluminescence value and related to the OD750. Results are presented in relative bioluminescence units. Experiments were repeated three times.

Generation of As1_flv4 Overexpression Strain

All primers used for plasmid preparation in this work are listed in supplemental Table S1. To generate the overexpression construct, a 563-nt DNA fragment beginning from the mapped as1_flv4 transcriptional start site (nucleotide 166849 according to Ref. 7) was fused with the petJ promoter and integrated with a kanamycin resistance cassette in the spkA gene. The spkA gene can be used as an uncommitted integration site because this gene is disrupted by a frameshift mutation in the Synechocystis strain used (44). The DNA fragment is longer than the asRNA transcript to allow for transcription termination at its own terminator. To prevent eventual read-through, the λ phage oop terminator was fused to the 3′-end of the fragment.

First a platform for the integration of a ncRNA between the petJ promoter and the oop terminator was constructed. The primers “5′ApaI_petJ” and “3′petJ_AsuII_oop_SalI” were used to amplify the petJ promoter fragment. The construct contained ApaI and SalI restriction sites for integration in the pJet-spk plasmid and an AsuII restriction site for the integration of an ncRNA between petJ promoter and oop terminator. The new pJet-spk-petJp plasmid was AsuII-digested for the integration of the AsuII-digested as1_flv4 fragment generated with the as_flv4_asuII_for and as_flv4_asuII_rev primers. The sense orientation of the fragment was tested with the as_flv4_asuII_rev primer and the spK_seg_for primer. The segregation of the construct in the genome was tested with the spK_seg_for and spK_seg_rev primers. A schematic presentation of the cloning strategy is shown in supplemental Fig. S1A.

RNA Extraction and Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with a TURBO DNase kit (Invitrogen) to remove genomic DNA. To characterize small RNAs, RNA samples (5 μg) were mixed with RNA loading dye (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), denatured for 10 min at 70 °C, separated in 10% polyacrylamide-urea gels, and transferred to Hybond-N nylon membranes (GE Healthcare) by electroblotting for 1 h. For the mRNA studies, RNA samples were mixed with denaturation solution, incubated for 10 min at 70 °C, separated in 1.3% agarose gels containing 7% formaldehyde in MOPS, and transferred to Hybond-N nylon membranes by capillary blotting with 10× SSC overnight (38). After UV cross-linking, even loading and blotting were checked by methylene blue staining (0.5 m sodium acetate, pH 5.2, 0.04% methylene blue). The membranes were hybridized with [α-32P]UTP-incorporated transcripts or [α-32P]CTP-labeled DNA probes. In vitro transcription was performed with the MAXIscript kit (Invitrogen) as described (39) and labeled DNA probes obtained with the Prime-Gene Labeling System (Promega, Madison, WI). Hybridization with the specific probes was performed in hybridization buffer (6× SSC, 5× Denhardt, 0.5% SDS, 1 mg ml−1 herring sperm DNA) overnight at 62 °C. The next day, membranes were washed three times with washing buffer (2× SSC, 0.1% SDS) for 10 min at 56 °C. Signals were visualized either by autoradiography on x-ray films or using a Personal Molecular Imager FX system with Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The sequences of the primers used for the preparation of transcript probes are listed in supplemental Table S1.

5′-Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends

The rapid amplification of cDNA 5′-ends was performed as described (40) using RNA from WT cells grown under LC conditions. The primers used are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Protein Isolation and Western Blot Analysis

Membrane and soluble fractions from Synechocystis cells were isolated as described (28). The protein samples were solubilized in Laemmli buffer (5% β-mercaptoethanol, 6 m urea) at room temperature for 2 h and separated by 12% SDS-PAGE. Then the proteins were transferred by semidry blotting to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and immunodetected with antibodies specific for Flv4, Flv2 (28), and Sll0218 (30).

RESULTS

High Abundance of ncRNAs Connected with the flv4-2 Operon

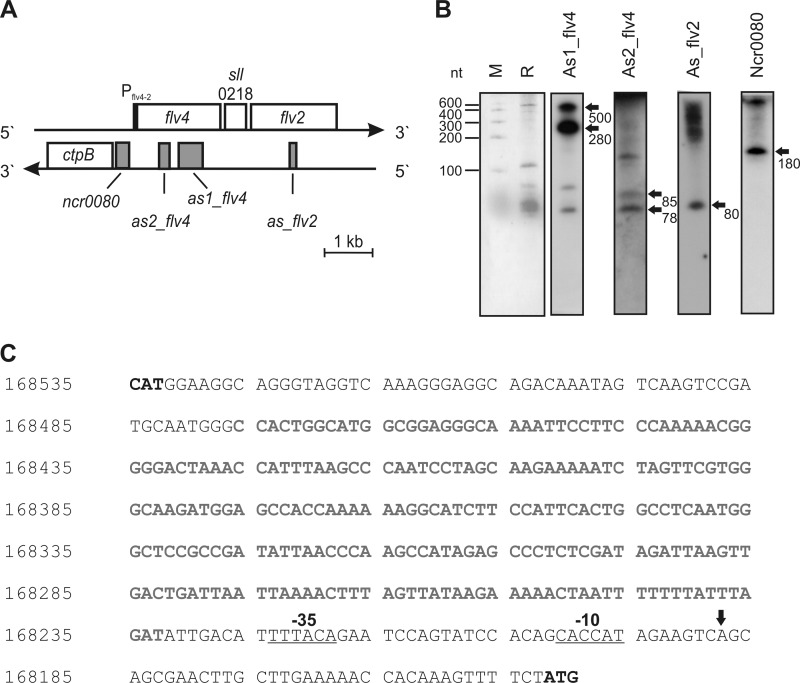

In the cyanobacterium Synechocystis, the flv4-2 operon comprises the three genes flv4, sll0218, and flv2 (Fig. 1A). A previous tiling microarray-based screening of the Synechocystis genome for naturally occurring ncRNA led to the discovery of 60 intergenically encoded ncRNAs and 73 cis-encoded (transcription in the antisense direction to the protein-coding region) asRNAs (7). Interestingly, an asRNA to flv4 was identified among the top scoring small regulatory RNAs in the screen (ranked 12 in the detected asRNAs with regard to the normalized mean signal intensity) and is designated here as As1_flv4. The existence of As1_flv4 transcript was verified by Northern blotting (Fig. 1B) using a single-stranded RNA probe. According to the Northern blots, main transcript lengths are 500 and ∼280 nt. A more recent differential RNA sequencing analysis yielded three more candidate ncRNAs associated with the flv4-2 operon (8). These are a second asRNA to flv4 named As2_flv4, an asRNA to flv2 named As_flv2, and one putative ncRNA originating from the flv4-ctpB intergenic spacer designated as Ncr0080 (Fig. 1A). The 5′-ends of all relevant genes and ncRNAs were mapped: nucleotide positions 166849, 167538, and 168233 on the forward strand are the transcriptional start sites of as1_flv4, as2_flv4, and ncr0080, respectively (chromosomal positions according to Cyanobase). The transcription start site of the ctpB gene is at position 168421. It has to be mentioned that there is no functional connection known between ctpB encoding a carboxyl-terminal protease (41, 42) and the flv4-2 operon. The existence of these candidates also was verified by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Here, the main transcript lengths are about 85 and 78 nt for As2_flv4, about 80 nt for As_flv2, and about 180 nt for the ncRNA Ncr0080, suggesting that its major 3′-end is located ∼10 nt upstream of the transcription start site of the ctpB gene. For all RNAs, extra bands were also detected, most probably resulting from degradation, processing, or read-through processes. In the following experiments, we focused on the regions that correspond to these main signals and to the data obtained from deep sequencing of the transcriptome (8).

FIGURE 1.

Noncoding RNAs connected with the flv4-2 operon. A, schematic presentation of chromosomal arrangement of the genes flv4, sll0218, and flv2 in the flv4-2 operon; ctpB; the antisense transcribed sections for as1_flv4, as2_flv4, and as_flv2; and the gene for ncRNA, ncr0080. B, verification of transcript accumulation by Northern blot analysis. RNA was isolated from HC-grown Synechocystis WT cells, separated by denaturing electrophoresis, and blotted onto a Hybond-N nylon membrane. RNA was stained with methylene blue. Specific radiolabeled probes were derived from in vitro transcription. Arrows indicate the selected signals. M, molecular mass marker; R, total RNA after electrophoresis. C, classification of the noncoding RNA Ncr0080. Shown is the region in between the start codons for ctpB (168533–168535) and flv4 (168152–168150). The ncr0080 sequence is in gray boldface, and the transcription start for flv4, according to the results of 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA end experiments, is marked with an arrow. Predicted −10 and −35 elements are underlined. The chromosomal positions are according to Cyanobase.

Because of the origin of Ncr0080 from an intergenic spacer in between two open reading frames (Fig. 1A), it was not clear whether the RNA was a trans-encoded ncRNA transcribed from the intergenic region between ctpB and flv4, was a cis-encoded asRNA overlapping with the 5′-UTR of the antisense encoded gene flv4, or constituted the 5′-UTR of ctpB. The latter possibility appeared to the least likely because in microarray experiments ncr0080 showed a regulation different from ctpB with maxima under high light, whereas ctpB did not respond to high light but was induced under LC (8). Because expression of flv4 had not been detected in the transcriptome analysis (8), we determined its transcription start site separately using RNA from LC-grown cells. 5′-Rapid amplification of cDNA end analysis (Fig. 1C) indicated that flv4 transcription starts from position 168188 on the reverse strand. Additionally, −10 and −35 elements were predicted with high scores according to the evaluation of more than 3,000 transcriptional start sites in Synechocystis (8). Deduced from these results, the RNA Ncr0080 (transcription start site at 168233) does not overlap with the 5′-UTR of flv4 and was therefore categorized as an ncRNA.

Expression of ncRNAs, mRNAs, and respective proteins upon Shift of Synechocystis from HC to LC Conditions

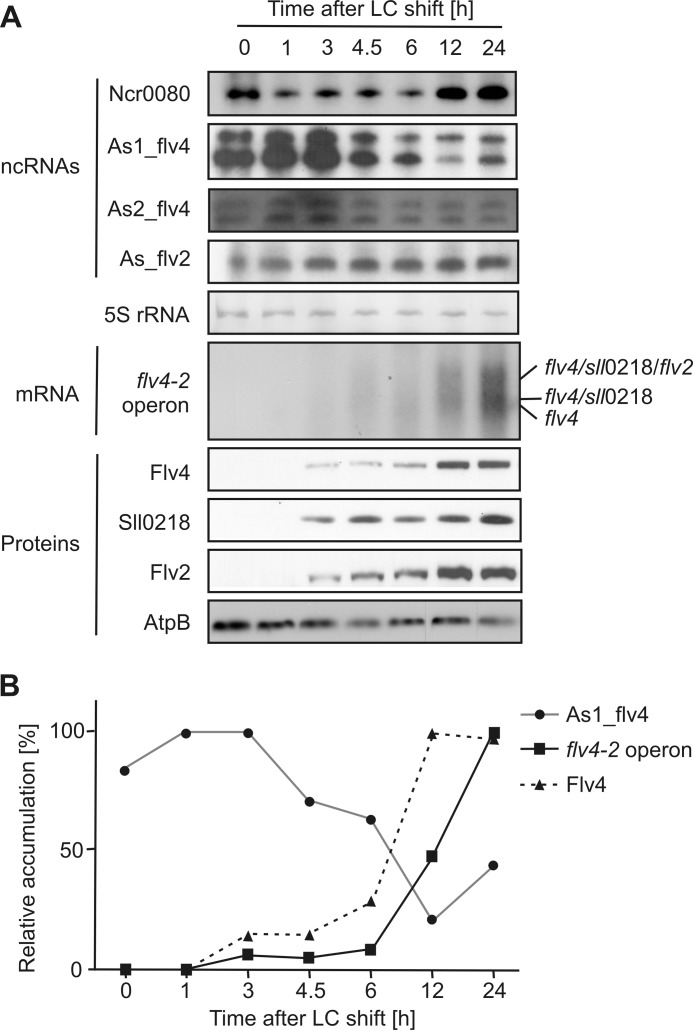

After identification and verification of the ncRNAs, we aimed to find out their biological role. Because it is well documented that the expression of the flv4-2 operon is strongly induced under LC conditions (16, 20) and the encoded proteins have a crucial function under those conditions (28, 30), we compared the time course of accumulation of ncRNAs, mRNA transcripts, and proteins after a shift of cells from HC to LC conditions (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Accumulation of flv4-2 operon-related ncRNAs, mRNA, and proteins after shift of Synechocystis WT cells from HC to LC conditions. Cells were precultivated under HC conditions and then shifted to LC. Samples were collected 0, 1, 3, 4.5, 6, 12, and 24 h after the LC shift and analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, results of blotting experiments. 5 S rRNA and AtpΒ were used as loading controls for RNA and protein, respectively. B, quantification of signal intensities. The strongest signal intensity for each probe was set to 100%, and the other signal intensities were related accordingly. Shown are the results of one representative experiment.

As expected, both flv4-2 mRNA and respective proteins accumulated under LC conditions. Following the LC shift, the tricistronic flv4-2 mRNA and the encoded proteins Flv4, Sll0218, and Flv2 first appeared after 3 h (Fig. 2A). The flv4-2 mRNA appears in the form of three bands representing the three possible mRNA fragments originating from the tripartite operon. Its diffuse character is likely due to a short half-life of the mRNA. Furthermore, we also sometimes observed sense-antisense RNA interactions in gels under denaturing conditions, which may distort band appearance. High protein levels were reached after 12 (Flv4 and Flv2) and 24 h (Sll0218), respectively. The mRNA was most abundant after 24 h (Fig. 2B) under these conditions. The transcript of asRNA As1_flv4, however, accumulated in a reverse manner. The transcript was present already under HC conditions and increased strongly in abundance shortly after the LC shift (1- and 3-h time points). Subsequently, the amount of asRNA As1_flv4 declined (Fig. 2). Accumulation of As2_flv4 transcript seemed to follow similar kinetics but with lower relative abundance, whereas the As_flv2 RNA levels increased over time (Fig. 2A). 24 h after the LC shift, As_flv2 levels were about 3-fold increased compared with HC conditions. Expression of Ncr0080 was strongly affected by the LC shift. The RNA amount was transiently down-regulated for the first 6 h after LC shift and recovered to HC levels after 12 h (Fig. 2A).

Because of the observed strong alterations in transcript levels of flv4-2 mRNA and As1_flv4 asRNA, we chose As1_flv4 as a target for more detailed analysis. To underpin our observation that As1_flv4 levels and flv4-2 operon products are inversely correlated with dependence on Ci levels, we repeated the original time course experiment (Fig. 2) by an additional shift of the culture back to HC conditions and monitored the accumulation of both asRNA and proteins encoded by the flv4-2 operon (supplemental Fig. S2). As in Fig. 2, a shift from HC to LC resulted in strong accumulation of the proteins Flv4, Sll0218, and Flv2, whereas the concentration of As1_flv4 transcript diminished. Importantly, the shift back to HC conditions had an opposite effect. The proteins gradually disappeared after the HC shift and were no longer detected after 6 h. In contrast, the amounts of As1_flv4 transcript recovered rapidly and were at the highest level 12 h after shifting back to HC. In summary, we saw direct and polar responses of the asRNA and the target proteins to changing Ci levels under the cultivation conditions used here.

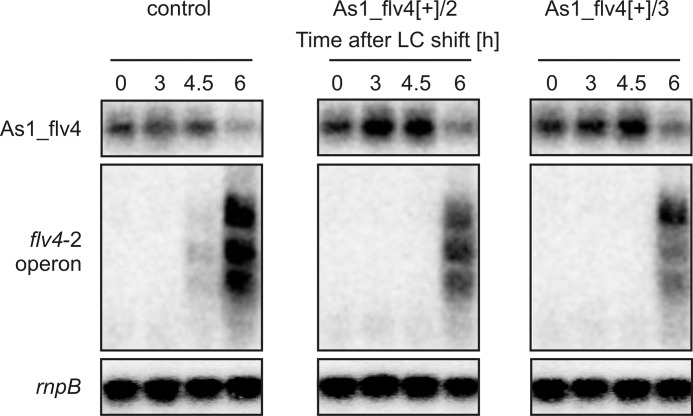

Modulation of asRNA As1_flv4 Abundance Effects flv4-2 Expression

The observed tightly controlled and inversely correlated accumulation of As1_flv4 transcript and its target mRNA strongly suggested a regulatory impact of As1_flv4 on the expression of the flv4-2 operon. To verify this, the abundance of the As1_flv4 transcript was artificially modulated in Synechocystis cells. To generate a mutant with elevated As1_flv4 levels, the sequence was fused with the promoter of the petJ gene, which is strongly induced in the absence of Cu2+ (43). The fusion construct was integrated by homologous recombination into the spkA gene. In the commonly used glucose-tolerant Synechocystis WT strain, this gene is disrupted by a frameshift mutation (44) and could therefore be regarded as a neutral integration site. After genotypic verification of the obtained overexpression mutant As1_flv4(+), two independent clones of the strain were initially characterized with regard to the expression strength of As1_flv4. Northern blot analysis (supplemental Fig. S1B) revealed successful overexpression of the asRNA As1_flv4 in the two overexpression mutants As1_flv4(+)/2 and As1_flv4(+)/3 when the cells were cultivated in Cu2+-free BG-11 medium for 46 h. We also tried to reduce internal As1_flv4 concentrations by expressing an antisense construct for As1_flv4, but the target asRNA levels did not change significantly for an unknown reason.

To analyze the impact of increased As1_flv4 transcript levels, we performed another time course experiment after shifting cells to LC. As expected, the control strain showed a similar expression pattern for the asRNA and the flv4-2 operon compared with WT cells in the previous experiments (Fig. 3). However, it was striking to find that compared with the control strain the overexpression mutants showed at 4.5 h after LC shift fully suppressed and at 6 h reduced (−15%) transcript levels of the flv4-2 operon (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Impact of artificial modulation of As1_flv4 transcript amount on the expression of the flv4-2 operon after shift from HC to LC conditions. For overexpression, the as1_flv4 coding sequence was fused with the petJ promoter, which is induced in the absence of Cu2+. For construction details, see “Experimental Procedures.” A mutant in spkA served as control strain. To reach maximal petJ promoter activity, cultures were precultivated under HC conditions and in the absence of Cu2+ for 48 h. After precultivation, LC-induced expression patterns of the asRNA As1_flv4 and the mRNAs of flv4, sll0218, and flv2 were monitored as described previously. As a loading control, rnpB was used. In this experiment, cultures were aerated by continuous bubbling.

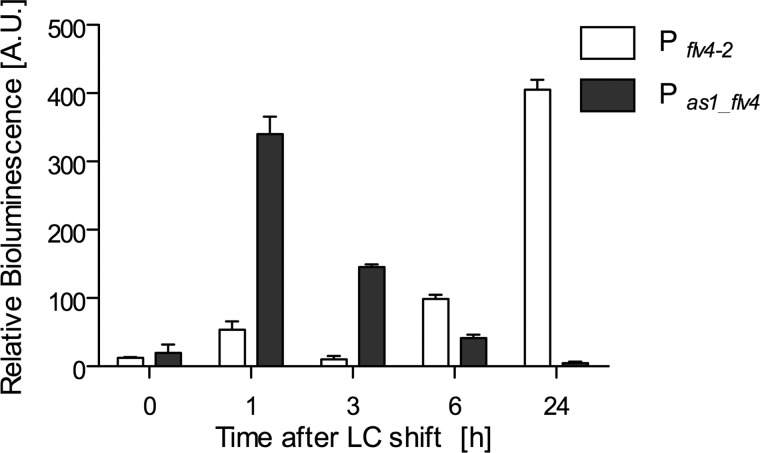

The as1_flv4 Promoter Is Transiently Induced after LC Shift

It has been well established that bacterial ncRNAs act by pairing with the target mRNA and thus modify the mRNA stability or translation in a positive or negative manner, respectively (45–48). Hence, the results of the Northern blotting experiments only demonstrate momentary RNA levels; therefore, it was of importance to unravel the true effects of changing Ci levels on transcription activity. For this purpose, we performed promoter activity analysis using a 300-nt fragment containing hypothetical promoter elements upstream of as1_flv4 and a 700-nt fragment containing the putative flv4-2 operon promoter fused with the reporter genes luxAB encoding the bioluminescent luciferase enzyme. The bioluminescence of transformed Synechocystis cells was quantified and used as a measure for the promoter activity (37). A promoterless construct was used as a negative control. For both promoters, significant activities were recorded under HC conditions (0-h time point; Fig. 4). Interestingly, the activity of the asRNA promoter highly increased at 1 and 3 h after the shift but then strongly declined after 6 h of LC stress. The flv4-2 promoter showed a different regulation. Its activity increased over time: after 6 h, the flv4-2 promoter activity was 8-fold increased, and after 24 h, promoter activity was about 30-fold increased compared with the HC level.

FIGURE 4.

Activities of as1_flv4 and flv4-2 operon promoters after shift from HC to LC conditions. Promoter sequences of the as1_flv4 gene and the flv4-2 operon were fused with the luxAB genes. The generated mutant strains MpILA-as1_flv4 and MpILA-flv4-2 were verified by PCR and used for luminescence measurement. The promoterless construct MpILA served as a negative control. Cells were cultivated under HC conditions and shifted to LC. At the given time points, samples were taken, and bioluminescence was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The bioluminescence was normalized to the OD750 and corrected by subtraction of luminol autoluminescence and MpILA luminescence. Each sample was measured in triplicates. Given are the means and S.D. (error bars) of triplicates of a representative time course. Pflv4-2, promoter of the flv4-2 operon; Pas1_flv4, promoter of the as1_flv4 gene. A.U., arbitrary units.

Transcriptional Regulator NdhR Controls the Expression of the flv4-2 Operon

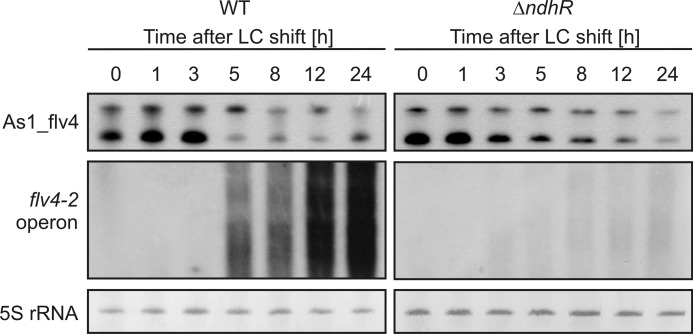

Because of the obviously Ci-controlled activity of the as1_flv4 promoter, we aimed to find a possible transcriptional regulator protein. For that purpose, we chose two known Ci-dependent transcriptional regulators in cyanobacteria, NdhR (16, 34) and the AbrB-like protein Sll0822 (36, 49, 50). Single mutants in either ndhR or sll0822 were characterized in respect to the expression of as1_flv4 and the flv4-2 operon. After LC shift, the ΔndhR mutant (16) accumulated heavily reduced amounts of the flv4-2 operon mRNA, whereas expression of the asRNA As1_flv4 was not influenced by the deletion of NdhR (Fig. 5). The reduction in flv4-2 mRNA levels correlated with a correspondingly reduced and delayed protein accumulation (supplemental Fig. S3A). The simplest explanation for this observation is that NdhR controls the promoter activity of the flv4-2 operon, which is indeed what we detected in promoter-reporter gene assays (supplemental Fig. S3B).

FIGURE 5.

Expression of as1_flv4 and the flv4-2 operon in the mutant ΔndhR and the WT. Shown is a representative time course of transcript abundances of the asRNA As1_flv4 and the mRNA of the flv4-2 operon after LC shift. 5 S rRNA was used as a loading control.

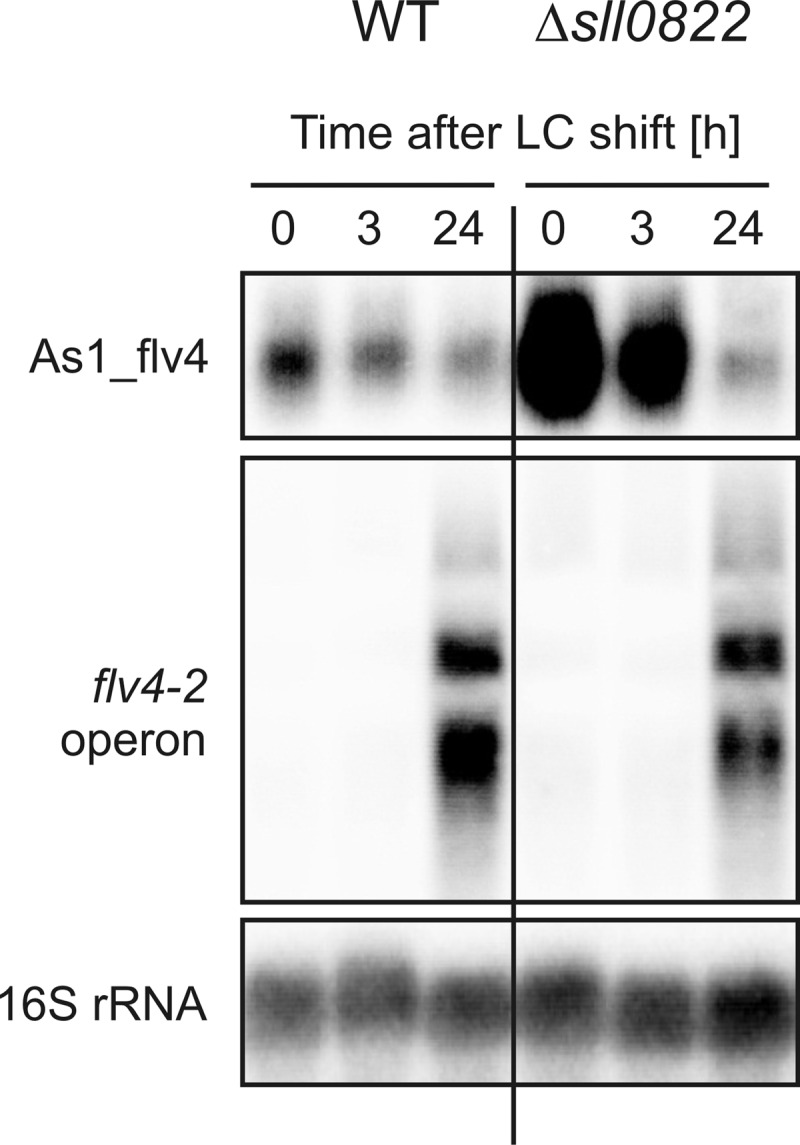

AbrB-like Protein Sll0822 Regulates the Expression of the asRNA As1_flv4

In an analogous experiment with the Δsll0822 mutant (49), we found a different behavior. Expression of as1_flv4 was massively enhanced with an about 10-fold accumulation compared with WT at 0 and 3 h after the shift from HC to LC conditions (Fig. 6), whereas expression of the flv4-2 operon mRNA was initially not affected. Nevertheless, after 24 h, the abundance of As1_flv4 transcripts returned to the low WT level, but the flv4-2 operon mRNA remained lower as compared with WT cells, which we interpret as a post-transcriptional effect caused by the enhanced As1_flv4 expression. These results indicate that the AbrB-like protein Sll0822 is a direct or indirect negative transcriptional regulator for the promoter activity of as1_flv4 and furthermore support the hypothesis that this asRNA titrates out the mRNA of the flv4-2 operon.

FIGURE 6.

Expression of as1_flv4 and the flv4-2 operon in the mutant Δsll0822 and the WT. Shown is a representative time course of transcript abundances of the asRNA As1_flv4 and the mRNA of the flv4-2 operon after LC shift. 16 S rRNA was used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

In the cyanobacterium Synechocystis, the expression of the flavodiiron proteins Flv4 and Flv2 was shown in several microarray analyses to respond to various stresses such as microaerobic conditions (51) and increased pH (52). Particularly extreme up-regulation of the genes organized in the flv4-2 operon occurs after a shift of cells from HC to LC conditions (16, 20). More detailed studies of Flv4 and Flv2 demonstrated their crucial function in the protection of PSII against photoinhibition under LC conditions as revealed by higher susceptibility of the mutants Δflv4 and Δflv2 to high light-induced inhibition of PSII activity than the WT (28). Recently, we showed that the Flv2/Flv4 heterodimer opens up an alternative electron transfer route, likely starting from the QB site in PSII (30), thus acting as an electron valve under photooxidative stress conditions.

Apparently related to the delicate function of the Flv2 and Flv4 proteins, the expression of the flv4-2 operon is strictly controlled. Here, for the first time, we provide evidence indicating that ncRNAs are involved in the Ci-dependent control mechanisms. Four ncRNAs, three asRNAs, and one intergenically encoded ncRNA were verified to be associated with the flv4-2 operon (Fig. 1). The most pronounced response in regard to the dependence on changing Ci levels was found for the asRNA As1_flv4, which accumulated strictly inversely with the mRNA and proteins derived from the target flv4-2 operon (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S2).

asRNA As1_flv4 Prevents Premature Expression of the flv4-2 Operon

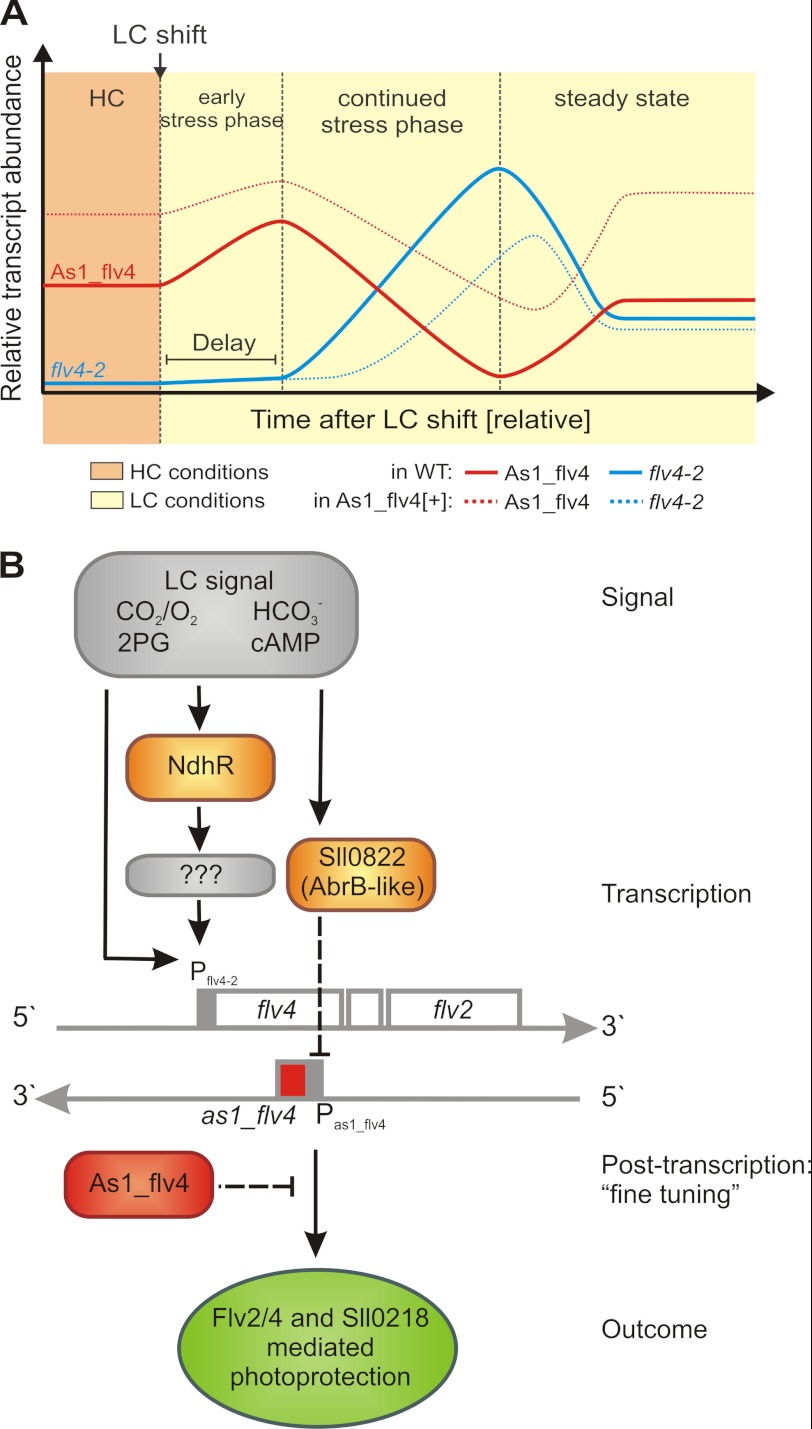

Based on the expression kinetics of the asRNA As1_flv4 and its target flv4-2 operon mRNA (Fig. 2) on the promoter activity measurements (Fig. 4) as well as on the characterization of the As1_flv4[+] overexpression mutants (Fig. 3), we suggest the model presented in Fig. 7A to explain the regulation of the flv4-2 operon by the asRNA As1_flv4 in response to changes in Ci conditions.

FIGURE 7.

Models of the Ci-controlled expression of the flv4-2 operon in Synechocystis. A, schematic representation of changes in the abundances of the asRNA As1_flv4 and flv4-2 operon transcripts upon shift of Synechocystis cells from HC to LC conditions. Given are relative abundances of the asRNA As1_flv4 (red line) and the flv4-2 operon mRNA (blue) in WT (solid line) and As1_flv4 overexpression strains (dashed lines). For a detailed description, see the text. The kinetics of the transcriptional response is strongly dependent on the experimental implementation and the resulting Ci levels in the medium. B, hypothetical model on the integrated function of transcriptional regulators NdhR and Sll0822 and the asRNA As1_flv4 in Ci-controlled expression of the flv4-2 operon. For a detailed description, see the text. 2PG, 2-phosphoglycolate.

As1_flv4 originates from the antisense strand to flv4. Both the asRNA and its target mRNA, flv4-2, are transcribed under HC conditions according to the promoter activity studies (Fig. 4). Most likely, the asRNA As1_flv4 pairs with its target, the flv4-2 mRNA, and the RNA duplexes are directed to co-degradation. Because the asRNA transcript is more abundant, the target mRNA is outcompeted, and no free flv4-2 mRNA occurs inside the cells. Indeed, neither the flv4-2 mRNA nor the respective proteins but only the asRNA As1_flv4 can be detected under HC conditions. The mechanisms of asRNA-mRNA interaction and subsequent degradation are poorly understood in cyanobacteria. In regard to the degradation of RNA duplexes, it was shown recently (53) that this process is mediated by the double-stranded RNA-specific RNase, RNase III, in Staphylococcus aureus. The involvement of RNase III has been postulated also for cyanobacteria (7, 10, 12, 48), and in this context, it is interesting to note that in contrast to most other bacteria Synechocystis has two different RNase III genes (slr0346 and slr1646).

When Synechocystis cells were exposed to LC conditions, the promoter of as1_flv4 was induced (Fig. 4). Intriguingly, the induction of the asRNA promoter was only transient but sufficient to prevent premature biosynthesis of the flv4-2-encoded proteins. Only if the LC signal persisted did the increasing flv4-2 promoter activity (Fig. 4) lead to high production of flv4-2 mRNA. At the time point when the mRNA level exceeds the asRNA abundance, the threshold is overcome, and flv4-2 mRNA becomes available for ribosome binding and subsequent protein biosynthesis (Fig. 7A). Finally, Flv2 and Flv4 assemble as heterodimers, Sll0218 stabilizes the PSII dimer, and thus the proteins protect the cell against photoinhibition under LC conditions (30). In general, the strong transcriptional response to a shift from HC to LC seems to be transient. Deduced from our previous results with steadily LC-grown cells (22, 28, 30) and prolonged promoter activity measurements (supplemental Fig. S3B), we hypothesize that after a peak in the accumulation of the flv4-2 mRNA the transcript amounts decline but remain at levels higher than those at prestress conditions, allowing for sufficient Flv2, Flv4, and Sll0218 synthesis under prolonged or even permanent LC treatment. This behavior is probably inversely mirrored by the asRNA As1_flv4 (Fig. 7A).

A mechanism similar to that for As1_flv4 was previously postulated for the asRNA IsrR (12). It was demonstrated that IsrR controls the expression of the gene isiA encoding the iron stress-induced protein IsiA in a stoichiometric manner. Artificial modulation of the internal IsrR levels was used to successfully prove such a regulatory function. Likewise, the artificial overexpression of the asRNA As1_flv4 resulted in decreased and delayed expression of the flv4-2 operon (Fig. 3).

In summary, the inverse correlation of asRNA As1_flv4 levels with flv4-2 transcripts and the results from the As1_flv4 overexpression experiments after a shift from HC to LC conditions are consistent with a major function of As1_flv4 in the early phase of the acclimation process to changed Ci levels. The amount of As1_flv4 transcripts sets a threshold for flv4-2 mRNA accumulation and thus delays the protein synthesis from the flv4-2 operon. It is also valid to assume that the asRNA As1_flv4 ensures rapid degradation of the flv4-2 mRNA and thus shuts down the Flv4-2-mediated electron valve promptly as discussed for IsrR in the shutdown of IsiA expression (54). The rapid depletion of the proteins Flv2, Flv4, and Sll0218 after a shift from LC to HC conditions is illustrated in supplemental Fig. S2.

AbrB-like Transcriptional Regulator Sll0822 Controls the Expression of as1_flv4

Importantly, we demonstrate here that the promoter activity of the asRNA encoding gene as1_flv4 after an LC shift is transiently induced (Fig. 4). To our knowledge, such transient induction is so far the first demonstration for a stress-responsive asRNA promoter in cyanobacteria. For comparison, the isrR promoter is to present knowledge constitutively active (48). The fact that the Ci levels control the promoter activity of the as1_flv4 prompted us to search for a transcriptional regulator protein exerting this control. We selected the NdhR protein and the AbrB-like protein Sll0822 as reasonable candidates and studied their impact on the expression of as1_flv4 and the flv4-2 operon, respectively. NdhR, which is also known as CcmR (34), belongs to the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. This large family of prokaryotic regulators typically activates genes and responds to coinducers (55). One of the best characterized examples is BenM, which controls genes involved in aromatic compound degradation in Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 (56). In cyanobacteria, besides NdhR, also the LysR-type transcriptional regulator CmpR was demonstrated to be involved in LC-induced gene expression. CmpR acts as activator of the cmp operon encoding the ATP-binding cassette-type bicarbonate transporter BCT1 (35). By contrast, NdhR has been characterized as a repressor of a regulon that includes genes encoding components of the inducible Ci uptake system, such as sbtA, ndhF3, ndhD3, and cupA (16). Sll0822, an AbrB-like protein, is suggested to serve as a repressor of LC-induced genes such as sbtA and ndhF3 (36) and is central in the regulation of carbon and nitrogen metabolism (49, 50). The results of our studies with mutants in either ndhR or sll0822 are the basis for a hypothetical model (Fig. 7B) on the integrated function of the transcriptional regulators NdhR and Sll0822 and the asRNA As1_flv4 in Ci-controlled expression of the flv4-2 operon. Changes in CO2 partial pressure and alterations in the level of HCO3− (18), cAMP (57), or 2-phosphoglycolate (20, 35) act as signals and trigger the cellular response toward LC stress. The transcriptional regulator NdhR is directly or indirectly involved in the activation of the promoter of the flv4-2 operon but has no effect on the accumulation of the asRNA (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S3). Because we could not identify NdhR binding sites in the promoter regions of the flv4-2 operon, it is likely that NdhR has secondary impact on the expression of this operon as postulated previously (16). In contrast, the AbrB-like protein Sll0822 controls primarily or solely the expression of the asRNA As1_flv4 as demonstrated by accumulation of high amounts of As1_flv4 transcript in the mutant Δsll0822 (Fig. 6). Again, the control can be either direct or indirect. Predictions, however, are not possible because the binding sites of Sll0822 have not yet been identified. The tightly regulated amount of asRNA As1_flv4 functions as a tool to “fine-tune” the post-transcriptional level to assure timed biosynthesis of the proteins encoded by the flv4-2 operon. Furthermore, it allows the integration of different signal sources, which are transduced by NdhR or Sll0822, respectively. As a result, the production of the Flv2, Flv4, and Sll0218 proteins provides PSII with a photoprotection mechanism under LC conditions when the terminal electron acceptors are scarce.

The biological functions of the other two asRNAs, As2_flv4 and As_flv2, are not yet clear. The As2_flv4 transcript accumulation is similar to that of As1_flv4 and hence might back up the As1_flv4-dependent delay in target protein synthesis. The Northern blot experiments (Fig. 2) did not show an inverse correlation for As_flv2 and its target mRNA as is the case with As1_flv4. It might be that the asRNA As_flv2 rather acts as a stabilizing element on the flv4-2 operon or solely on the flv2 transcript. The biological function of the noncoding RNA Ncr0080 and the identity of its target mRNA in particular remain completely unknown, but the Ci-dependent accumulation points to a possible role in LC acclimation as well.

Ecological Implications of asRNA-regulated Control of flv4-2 Operon Expression and Beyond

The postulated function of some bacterial asRNAs is the establishment of a threshold for expression of the target gene. This threshold is thought to provide a safety mechanism against transcriptional noise or transient stress signals (48, 53, 54, 58). For Synechocystis, it is mandatory to avoid the premature expression of the flv4-2 operon after a shift from HC to LC conditions for the following reasons. First, each flavodiiron protein contains two iron molecules. The iron quota of Synechocystis is 1 order of magnitude higher than that of the similarly sized Escherichia coli (59), and its bioavailability in aquatic environments is frequently limited because Fe3+ forms insoluble crystals. Therefore, iron is often a limiting factor in the cyanobacterial environment (60) and should rather be available for essential enzymes involved in e.g. photosynthesis than wasted without a crucial reason like transient Ci limitation. Second, Sll0218-, Flv2-, and Flv4-catalyzed reactions consume electrons from PSII (30). Under HC conditions, it is favorable for the cyanobacterium to direct the photosynthetically produced energy toward CO2 fixation and rather than to waste the energy in Flv4-2-mediated processes. The tight control of the flv4-2 operon is thought to ensure maximal photosynthetic efficiency in unstressed cells in HC and conversely to provide photoprotection upon stressful conditions in LC. However, it has to be noted that the growth conditions (e.g. low and continuous light) used here do not essentially reflect natural conditions. Hence, our suggested ecological implications have to be considered as potentially limited. The real environmental growth conditions provide substantially stronger, more diverse, and more frequent fluctuations in irradiance than our laboratory conditions, including day/night cycles and the combination with other stress conditions. Therefore, we assume that in natural environments it is much more important to buffer against short term environmental changes, e.g. to prevent the initiation of long term acclimation processes upon only a short term stress period. It also seems favorable to integrate different signals to prevent responses that are beneficial at an isolated stress condition but may be detrimental in a more complex superposition of different environmental and metabolic cues. This biological important fine-tuning is likely to be a main function of many regulatory RNAs and especially cis-asRNAs (48).

To our knowledge, this is the first time the involvement of an asRNA (As1_flv4) in the bacterial Ci-regulatory network has been demonstrated. The asRNA As1_flv4 contributes at least partially to the Ci-dependent regulation of the Flv4-2 proteins by establishing the safety threshold and timely shifted expression during the early phase of LC acclimation. It is also of note that altogether 16 asRNAs and 29 ncRNAs respond to Ci limitation in Synechocystis (8). The observations made here for the strict control of the flv4-2 operon are also possibly applicable for other elements of the Ci regulon in Synechocystis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Annegret Wilde for helpful discussion and Tuomas Huovinen for support with the bioluminescence measurements. The mutant ΔndhR was kindly provided by Robert Burnap, and the mutant Δsll0822, originally created by Yukako Hihara, was provided by Aaron Kaplan. Martin Hagemann kindly provided the promoter test vector pILA. The plasmid pJet-spk was kindly provided by Ekaterina Kuchmina (A. Wilde laboratory). We thank Doreen Schwarz for support with Δsll0822. We acknowledge technical support by Maija Holmström, Anniina Leppäniemi, and Gudrun Krüger.

This work was supported by Academy of Finland Projects 118637 and 133299 (to E.-M. A. and M. E.), European Union Project Solar-H2 (FP7 Contract 212508) (to E.-M. A.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Focus Program “Sensory and Regulatory RNAs in Prokaryotes” SPP1258 and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung Grant 0313921 (to W. R. H.), and the DFG-sponsored graduate school GRK1305 “Signal Systems in Plant Model Organisms” (to J. G.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Table S1.

- asRNA

- antisense RNA

- ncRNA

- noncoding RNA

- PSII

- photosystem II

- LC

- low carbon (0.038% CO2 in air)

- HC

- high carbon (3% CO2 in air)

- Ci

- inorganic carbon

- nt

- nucleotide(s)

- CCM

- CO2-concentrating mechanism

- Flv

- flavodiiron

- Rubisco

- ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cuperus J. T., Fahlgren N., Carrington J. C. (2011) Evolution and functional diversification of MIRNA genes. Plant Cell 23, 431–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Lucia F., Dean C. (2011) Long non-coding RNAs and chromatin regulation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 14, 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou X., Sunkar R., Jin H., Zhu J. K., Zhang W. (2009) Genome-wide identification and analysis of small RNAs originated from natural antisense transcripts in Oryza sativa. Genome Res. 19, 70–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang X., Xia J., Lii Y. E., Barrera-Figueroa B. E., Zhou X., Gao S., Lu L., Niu D., Chen Z., Leung C., Wong T., Zhang H., Guo J., Li Y., Liu R., Liang W., Zhu J. K., Zhang W., Jin H. (2012) Genome-wide analysis of plant nat-siRNAs reveals insights into their distribution, biogenesis and function. Genome Biol. 13, R20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jin H., Vacic V., Girke T., Lonardi S., Zhu J. K. (2008) Small RNAs and the regulation of cis-natural antisense transcripts in Arabidopsis. BMC Mol. Biol. 9, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhelyazkova P., Sharma C. M., Förstner K. U., Liere K., Vogel J., Börner T. (2012) The primary transcriptome of barley chloroplasts: numerous non-coding RNAs and the dominating role of the plastid-encoded RNA polymerase. Plant Cell 24, 123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Georg J., Voss B., Scholz I., Mitschke J., Wilde A., Hess W. R. (2009) Evidence for a major role of antisense RNAs in cyanobacterial gene regulation. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitschke J., Georg J., Scholz I., Sharma C. M., Dienst D., Bantscheff J., Voss B., Steglich C., Wilde A., Vogel J., Hess W. R. (2011) An experimentally anchored map of transcriptional start sites in the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 2124–2129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitschke J., Vioque A., Haas F., Hess W. R., Muro-Pastor A. M. (2011) Dynamics of transcriptional start site selection during nitrogen stress-induced cell differentiation in Anabaena sp. PCC7120. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20130–20135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hernández J. A., Muro-Pastor A. M., Flores E., Bes M. T., Peleato M. L., Fillat M. F. (2006) Identification of a furA cis antisense RNA in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hernández J. A., Alonso I., Pellicer S., Luisa Peleato M., Cases R., Strasser R. J., Barja F., Fillat M. F. (2010) Mutants of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 lacking alr1690 and α-furA antisense RNA show a pleiotropic phenotype and altered photosynthetic machinery. J. Plant Physiol. 167, 430–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dühring U., Axmann I. M., Hess W. R., Wilde A. (2006) An internal antisense RNA regulates expression of the photosynthesis gene isiA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7054–7058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benschop J. J., Badger M. R., Dean Price G. (2003) Characterisation of CO2 and HCO3− uptake in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Photosynth. Res. 77, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McGinn P. J., Price G. D., Maleszka R., Badger M. R. (2003) Inorganic carbon limitation and light control the expression of transcripts related to the CO2-concentrating mechanism in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. Plant Physiol. 132, 218–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woodger F. J., Badger M. R., Price G. D. (2003) Inorganic carbon limitation induces transcripts encoding components of the CO2-concentrating mechanism is Synechococcus sp. PCC7942 through a redox-independent pathway. Plant Physiol. 133, 2069–2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang H. L., Postier B. L., Burnap R. L. (2004) Alterations in global patterns of gene expression in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 in response to inorganic carbon limitation and the inactivation of ndhR, a LysR family regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5739–5751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang P., Battchikova N., Jansen T., Appel J., Ogawa T., Aro E. M. (2004) Expression and functional roles of the two distinct NDH-1 complexes and the carbon acquisition complex NdhD3/NdhF3/CupA/Sll1735 in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Cell 16, 3326–3340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Woodger F. J., Badger M. R., Price G. D. (2005) Sensing of inorganic carbon limitation in Synechococcus PCC7942 is correlated with the size of the internal inorganic carbon pool and involves oxygen. Plant Physiol. 139, 1959–1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eisenhut M., Kahlon S., Hasse D., Ewald R., Lieman-Hurwitz J., Ogawa T., Ruth W., Bauwe H., Kaplan A., Hagemann M. (2006) The plant-like C2 glycolate cycle and the bacterial-like glycerate pathway cooperate in phosphoglycolate metabolism in cyanobacteria. Plant Physiol. 142, 333–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eisenhut M., von Wobeser E. A., Jonas L., Schubert H., Ibelings B. W., Bauwe H., Matthijs H. C., Hagemann M. (2007) Long-term response toward inorganic carbon limitation in wild type and glycolate turnover mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 144, 1946–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eisenhut M., Huege J., Schwarz D., Bauwe H., Kopka J., Hagemann M. (2008) Metabolome phenotyping of inorganic carbon limitation in cells of the wild type and photorespiratory mutants of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 148, 2109–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Battchikova N., Vainonen J. P., Vorontsova N., Keranen M., Carmel D., Aro E. M. (2010) Dynamic changes in the proteome of Synechocystis 6803 in response to CO2 limitation revealed by quantitative proteomics. J. Proteome. Res. 9, 5896–5912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwarz D., Nodop A., Hüge J., Purfürst S., Forchhammer K., Michel K. P., Bauwe H., Kopka J., Hagemann M. (2011) Metabolic and transcriptomic phenotyping of inorganic carbon acclimation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Plant Physiol. 155, 1640–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaplan A., Reinhold L. (1999) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 539–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Badger M. R., Price G. D. (2003) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 609–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giordano M., Beardall J., Raven J. A. (2005) CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 99–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Price G. D., Badger M. R., Woodger F. J., Long B. M. (2008) Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 1441–1461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang P., Allahverdiyeva Y., Eisenhut M., Aro E. M. (2009) Flavodiiron proteins in oxygenic photosynthetic organisms: photoprotection of photosystem II by Flv2 and Flv4 in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS One 4, e5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allahverdiyeva Y., Ermakova M., Eisenhut M., Zhang P., Richaud P., Hagemann M., Cournac L., Aro E. M. (2011) Interplay between flavodiiron proteins and photorespiration in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 24007–24014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang P., Eisenhut M., Brandt A. M., Carmel D., Silén H. M., Vass I., Allahverdiyeva Y., Salminen T. A., Aro E. M. (2012) Operon flv4-flv2 provides cyanobacteria with a novel photoprotection mechanism. Plant Cell 24, 1952–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaneko T., Sato S., Kotani H., Tanaka A., Asamizu E., Nakamura Y., Miyajima N., Hirosawa M., Sugiura M., Sasamoto S., Kimura T., Hosouchi T., Matsuno A., Muraki A., Nakazaki N., Naruo K., Okumura S., Shimpo S., Takeuchi C., Wada T., Watanabe A., Yamada M., Yasuda M., Tabata S. (1996) Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 3, 109–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vicente J. B., Gomes C. M., Wasserfallen A., Teixeira M. (2002) Module fusion in an A-type flavoprotein from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis condenses a multiple-component pathway in a single polypeptide chain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 294, 82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Helman Y., Tchernov D., Reinhold L., Shibata M., Ogawa T., Schwarz R., Ohad I., Kaplan A. (2003) Genes encoding A-type flavoproteins are essential for photoreduction of O2 in cyanobacteria. Curr. Biol. 13, 230–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Woodger F. J., Bryant D. A., Price G. D. (2007) Transcriptional regulation of the CO2-concentrating mechanism in a euryhaline, coastal marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7002: role of NdhR/CcmR. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3335–3347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nishimura T., Takahashi Y., Yamaguchi O., Suzuki H., Maeda S., Omata T. (2008) Mechanism of low CO2-induced activation of the cmp bicarbonate transporter operon by a LysR family protein in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus strain PCC 7942. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 98–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lieman-Hurwitz J., Haimovich M., Shalev-Malul G., Ishii A., Hihara Y., Gaathon A., Lebendiker M., Kaplan A. (2009) A cyanobacterial AbrB-like protein affects the apparent photosynthetic affinity for CO2 by modulating low-CO2-induced gene expression. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 927–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kunert A., Hagemann M., Erdmann N. (2000) Construction of promoter probe vectors for Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 using the light-emitting reporter systems Gfp and LuxAB. J. Microbiol. Methods 41, 185–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hagemann M., Schoor A., Jeanjean R., Zuther E., Joset F. (1997) The stpA gene from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 encodes the glucosylglycerol-phosphate phosphatase involved in cyanobacterial osmotic response to salt shock. J. Bacteriol. 179, 1727–1733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steglich C., Futschik M. E., Lindell D., Voss B., Chisholm S. W., Hess W. R. (2008) The challenge of regulation in a minimal photoautotroph: non-coding RNAs in Prochlorococcus. PloS Genet. 4, e1000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Argaman L., Hershberg R., Vogel J., Bejerano G., Wagner E. G., Margalit H., Altuvia S. (2001) Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol. 11, 941–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jansèn T., Kidron H., Soitamo A., Salminen T., Mäenpää P. (2003) Transcriptional regulation and structural modelling of the Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 carboxyl-terminal endoprotease family. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 228, 121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Komenda J., Kuviková S., Granvogl B., Eichacker L. A., Diner B. A., Nixon P. J. (2007) Cleavage after residue Ala352 in the C-terminal extension is an early step in the maturation of the D1 subunit of photosystem II in Synechocystis PCC 6803. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1767, 829–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tous C., Vega-Palas M. A., Vioque A. (2001) Conditional expression of RNase P in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 allows detection of precursor RNAs. Insight in the in vivo maturation pathway of transfer and other stable RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29059–29066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kamei A., Yuasa T., Orikawa K., Geng X. X., Ikeuchi M. (2001) A eukaryotic-type protein kinase, SpkA, is required for normal motility of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 183, 1505–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Altuvia S., Weinstein-Fischer D., Zhang A., Postow L., Storz G. (1997) A small, stable RNA induced by oxidative stress: role as a pleiotropic regulator and antimutator. Cell 90, 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Majdalani N., Cunning C., Sledjeski D., Elliott T., Gottesman S. (1998) DsrA RNA regulates translation of RpoS message by an anti-antisense mechanism, independent of its action as an antisilencer of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 12462–12467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Opdyke J. A., Kang J. G., Storz G. (2004) GadY, a small-RNA regulator of acid response genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6698–6705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Georg J., Hess W. R. (2011) cis-Antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 286–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ishii A., Hihara Y. (2008) An AbrB-like transcriptional regulator, Sll0822, is essential for the activation of nitrogen-regulated genes in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 148, 660–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamauchi Y., Kaniya Y., Kaneko Y., Hihara Y. (2011) Physiological roles of the cyAbrB transcriptional regulator pair Sll0822 and Sll0359 in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 193, 3702–3709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Summerfield T. C., Toepel J., Sherman L. A. (2008) Low-oxygen induction of normally cryptic psbA genes in cyanobacteria. Biochemistry 47, 12939–12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Summerfield T. C., Sherman L. A. (2008) Global transcriptional response of the alkali-tolerant cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 to a pH 10 environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5276–5284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lasa I., Toledo-Arana A., Dobin A., Villanueva M., de los Mozos I. R., Vergara-Irigaray M., Segura V., Fagegaltier D., Penadés J. R., Valle J., Solano C., Gingeras T. R. (2011) Genome-wide antisense transcription drives mRNA processing in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20172–20177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Legewie S., Dienst D., Wilde A., Herzel H., Axmann I. M. (2008) Small RNAs establish delays and temporal thresholds in gene expression. Biophys. J. 95, 3232–3238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schell M. A. (1993) Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47, 597–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bundy B. M., Collier L. S., Hoover T. R., Neidle E. L. (2002) Synergistic transcriptional activation by one regulatory protein in response to two metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7693–7698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hammer A., Hodgson D. R., Cann M. J. (2006) Regulation of prokaryotic adenylyl cyclases by CO2. Biochem. J. 396, 215–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Levine E., Hwa T. (2008) Small RNAs establish gene expression thresholds. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11, 574–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Shcolnick S., Summerfield T. C., Reytman L., Sherman L. A., Keren N. (2009) The mechanism of iron homeostasis in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 and its relationship to oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 150, 2045–2056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morel F. M., Price N. M. (2003) The biogeochemical cycles of trace metals in the oceans. Science 300, 944–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.