Abstract

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligatory intracellular bacterium which resides in an early endosome in monocytes. E. chaffeensis infection in a human monocyte cell line (THP1) significantly altered the transcriptional levels of 4.5% of host genes, including those coding for apoptosis inhibitors, proteins regulating cell differentiation, signal transduction, proinflammatory cytokines, biosynthetic and metabolic proteins, and membrane trafficking proteins. The transcriptional profile of the host cell revealed key themes in the pathogenesis of Ehrlichia. First, E. chaffeensis avoided stimulation of or repressed the transcription of cytokines involved in the early innate immune response and cell-mediated immune response to intracellular microbes, such as the interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-15, and IL-18 genes, which might make Ehrlichia a stealth organism for the macrophage. Second, E. chaffeensis up-regulated NF-κB and apoptosis inhibitors and differentially regulated cell cyclins and CDK expression, which may enhance host cell survival. Third, E. chaffeensis also inhibited the gene transcription of RAB5A, SNAP23, and STX16, which are involved in membrane trafficking. By comparing the transcriptional response of macrophages infected with other bacteria and that of macrophages infected with E. chaffeensis, we have identified few genes that are commonly induced and no commonly repressed genes. These results illustrate the stereotyped macrophage response to other pathogens, in contrast with the novel host response to obligate intracellular Ehrlichia, whose survival depends entirely on a long evolutionary process of outmaneuvering macrophages.

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is a gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium which resides in a vacuole within host cells (6, 13). It causes human monocytic ehrlichiosis, an emerging infectious disease first reported in 1987. Human monocytic ehrlichiosis is a moderate to severe disease, with a case fatality rate of approximately 3% (27). The life cycle of E. chaffeensis includes a mammalian host and a tick vector (3). E. chaffeensis is transmitted in ticks transstadially but not transovarially. To overcome this lack of efficient maintenance in ticks, E. chaffeensis has evolved to establish persistent infection in its natural animal hosts, such as white-tailed deer (12) and canines (14). The principal target cell of E. chaffeensis is the monocyte/macrophage lineage. The tropism of this organism for monocytes and its ability to evade normal phagocytic pathways suggest that the organism may have evolved for some unique pathways for intracellular survival and development of infection. E. chaffeensis resides in an early endosome. The survival of E. chaffeensis inside the host cell depends on inhibiting fusion of the phagosome and the lysosome (6).

Understanding the transcriptional profiles of monocyte genes at various time points in response to E. chaffeensis will help us to decipher the tactics used by E. chaffeensis to evade host cell responses and thus will aid future efforts in developing therapeutics. For this study, we used the HG-U95Av2 gene chip (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, Calif.), containing 12,599 sequenced human genes or expressed sequence tags (ESTs), to measure gene expression profiles of the THP1 monocyte cell line 1, 7, 11, and 24 h after exposure to E. chaffeensis (38). We provide some insight into the mechanisms used by E. chaffeensis to block fusion of the phagosome and the lysosome, to evade the host immune system, and to inhibit host cell apoptosis and enhance host cell survival, which are essential to the well-being of the ehrlichiae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

E. chaffeensis.

E. chaffeensis strain Arkansas was cultivated in THP1 cells, a human monocyte cell line, with 10% bovine calf serum-supplemented Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium at 37°C. When 90% of the cells were infected (at approximately 5 days postinfection), ehrlichiae were harvested. The cells were centrifuged for 20 min at 12,100 × g. The pellet was suspended in SPK buffer (0.2 M sucrose, 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) (35) and sonicated twice for 10 s on ice at 40 W, using an Ultrasonic processor (Sonic & Materials Inc., Newtown, Conn.). The suspension was centrifuged at 200 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged for 20 min at 12,100 × g. The pellet was suspended in freezing medium (10% dimethyl sulfoxide, 20% bovine serum, and 70% minimal essential medium). The ehrlichial suspension was divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C as a stock for subsequent infection of THP1 cells and determination of the E. chaffeensis infectious content.

The E. chaffeensis infectivity titer was determined by limiting dilution of host cell-free ehrlichiae. Briefly, diluted ehrlichiae were applied onto DH82 cell monolayers in 24-well plates and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 14 days, with a medium change every 3 days. On days 7 and 14 after infection, cells were examined by PCR and Diff-Quik staining for E. chaffeensis infection. DNA was extracted from cells by use of a Qiagen DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). One microliter of DNA was used to amplify the gp120 gene of E. chaffeensis with primers pxcf3b (5′-CAG CAA GAG CAA GAA GAT GAC) and pxar5 (5′-ATC TTT CTC TAC AAC AAC CGG) (39). PCR amplification was performed for 30 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 55°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension of 7 min. The size of the PCR product was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis. For Diff-Quik staining, 200 μl of supernatant from each well was centrifuged onto a slide with a Cytospin centrifuge. The slides were stained and examined for E. chaffeensis morulae.

E. chaffeensis DNA and RNA isolation.

THP1 cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were infected with host cell-free E. chaffeensis at a multiplicity of infection of 100 and cultivated at 37°C under the same conditions as those described above. Samples of THP1 cells (50 ml) were obtained at 1, 7, 11, and 24 h postinoculation and used for DNA and total RNA isolation by use of a Qiagen DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen) and NucleoSpin RNA and virus purification kits (Clontech), respectively. THP1 cells (50 ml) taken prior to inoculation of E. chaffeensis were used as a 0-h time point control. One microliter of DNA was used to amplify the gp120 gene with primers pxcf3b and pxar5 to confirm E. chaffeensis infection. The purity of the RNA was determined by use of the PicoGreen RNA quantitation kit (Molecular Probes). The integrity of RNA was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis.

cDNA target preparation and array hybridization.

The HG-U95Av2 gene chip (Affymetrix Inc.), containing 12,599 sequenced human genes and ESTs, was used for screening gene expression. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with total RNA (10 to 25 μg), a T7-(dT)24 oligomer (5′-GGCCAGTGAATTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGGCGG-dT24-3′), and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies). Second-strand synthesis converted the cDNA into a double-stranded DNA template for use in an in vitro transcription reaction. The T7 promoter introduced during first-strand cDNA synthesis provided the necessary sequence for directing the synthesis of cRNA with bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. The cRNA targets were labeled with biotin during the in vitro transcription reaction. cRNAs labeled with biotin were fragmented to a mean size of 200 bases to facilitate their hybridization to probe sequences on the gene chip array. Each target sample was initially hybridized to a test array to confirm the successful labeling of the cRNAs and to prevent the use of degraded or nonrepresentative target cRNA samples. The test array contained a set of probes representing genes that are commonly expressed in the majority of cells (actin, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH], transferrin receptor, transcription factor ISGF-3, 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA, and Alu genes).

Hybridization of the HG-U95Av2 gene chip arrays was performed at 45°C for 16 h in hybridization buffer (0.1 M morpholineethanesulfonic acid [pH 6.6], 1 M NaCl, 0.02 M EDTA, and 0.01% Tween 20). Four prokaryotic genes (bioB, bioC, and bioD from the Escherichia coli biotin synthesis pathway and cre, the recombinase gene from bacteriophage P1) were added to the hybridization cocktail as internal controls. Arrays were washed under both nonstringent (1 M NaCl, 25°C) and stringent (1 M NaCl, 50°C) conditions prior to staining with phycoerythrin-streptavidin (final concentration, 10 μg/ml).

Gene chip arrays were scanned with a Gene Array scanner (Hewlett-Packard) and analyzed with Gene Chip Analysis, suite 3.3, software (Affymetrix Inc.). For each gene, 16 to 20 probe pairs were immobilized as ∼25-mer oligonucleotides that hybridized throughout the mRNA; each probe pair is represented as a perfect match (PM) oligonucleotide and a mismatch (MM) oligonucleotide used as a hybridization control. The average intensity of each probe cell was calculated after subtraction of the local background (the lowest 2% intensity of each sector; each probe cell is divided into 16 sectors). The normalized average intensity value was used to determine the number of positive and negative probe pairs. Based on the positive/negative ratio, the positive fraction, and the log average ratio of the PM to the MM, the absolute call (i.e., expression of the gene is detected [present] or not [absent]) was determined. Finally, the average difference was determined by calculating the difference in intensity between the PM and the MM of every probe pair and averaging the differences over the entire probe set. The average difference statistic was retrieved for quantification of mRNA abundance for those samples in which the absolute call indicated that the gene was present. Probe set data were deposited into our data warehouse and relational database server (http://www.bioinfo.utmb.edu).

Data analysis for oligonucleotide probe-based microarrays.

Following normalization against the housekeeping genes, the oligonucleotide spot intensity values for each array were compared for the different time points. Gene probe sets with an absolute call of “absent” across all the chips were removed, and gene probe sets that changed ≥|3|-fold in any one of the possible pairwise comparisons were used for further analysis of K means and hierarchical cluster analysis, using the software package Spotfire (Somerville, Mass.).

To more reliably profile global changes in gene expression, we analyzed the reproducibility of the data generated for two independent time courses by log-log plots of the average differences in signal for the independently performed arrays for each time point of E. chaffeensis infection. At each time point, linear regression analysis was performed. In addition, a hierarchical clustering algorithm was used to analyze the reproducibility of the data generated in different arrays in independent time courses.

Confirmation of differential expression of genes.

The expression of selected genes was further analyzed for E. chaffeensis-infected THP1 cells by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR. Total cellular RNA (2 μg) was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with the RETROscript first-strand synthesis kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, Tex.). PCRs were carried out by use of the Roche PCR master kit (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). PCR conditions were the same as those described above. Two negative controls, including a −RT control without reverse transcriptase and a minus-template PCR without sample cDNA, and one positive control, the control template RNA from the kit, were used in PCRs to verify the RT-PCR. The selected host genes and their primers are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Confirmation of the oligonucleotide array results by RT-PCR amplification of selected genes

| Gene | Primerb | Fold change in transcription level in oligonucleotide array at ha:

|

Confirmation by RT-PCR at h:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 24 | 1 | 11 | 24 | ||

| Hiap1 | TGACCTTGTCATTCACACCAG | 1.2 | 7.3 | 5.1 | − | + | + |

| GCCATTAAATGGCATCCTGAT | |||||||

| IL-1a | CAAGGAGAGCATGGTGGTAGTAGCAACCAACG | −0.3 | −0.5 | −0.8 | − | − | − |

| TAGTGCCGTGAGTTTCCCAGAAGAAGAGGAGG | |||||||

| IL-4 | CTCATGATCGTCTTTAGCCT | −1.2 | −0.8 | −0.6 | − | − | − |

| CTCTGTTCTTCCTGCTAGCAT | |||||||

| IL-6 | AATTCGGTACATCCTCGACGG | −0.8 | −0.8 | −0.9 | − | − | − |

| TGACCAGAAGAAGGAATGCCC | |||||||

| IL-8 | AAGAGCCAGGAAGAAACCACC | 8.5 | 2.5 | 1.0 | + | + | + |

| ATTGCATCTGGCAACCCTACA | |||||||

| IL-12a | CCGGCTCAGCATGTGTCCA | UD | UD | UD | − | − | − |

| CAGCTCATCAATAACTGCCAGCA | |||||||

| IL-12b | GATGGTATCACCTGGACCTTG | UD | UD | UD | − | − | − |

| GCATCCACCATGACCTCAAT | |||||||

| IL-15 | GATGGATGGCTGCTGGAA | −1.1 | −7.0 | −1.5 | − | − | − |

| CATTGCTGTTACTTTGCAACTG | |||||||

| IL-18 | CTCAGACCTTCCAGATCGCTT | −2.5 | −4.6 | −2.0 | − | − | − |

| GTGATCTGCCCGCCTCAG | |||||||

| E-selectin | CCGAAGGGTTTGGTGAGGTGTGCT | 2.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 | + | + | + |

| AAATGGTGCTAATGTCAGGAGGGAGAGTC | |||||||

| P-selectin | ACTGGGCTGATAATGAACCTAACAACAAAA | UD | UD | UD | − | − | − |

| GAGGCTTATTTGTCCAGATTCCAGA | |||||||

| SELPLG | CCACCAGCAGCCACGGAAGC | 1.23 | 1.4 | 1.2 | + | + | + |

| GCCACCAGCGCCAAGATTAGGAT | |||||||

| TFAR15 | GATGAATTAGTCGGTTGGCAC | −1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | − | + | + |

| GAACGAGTAAATCTGTCTGCAG | |||||||

Fold change in macrophage gene transcriptional level 1, 11, and 24 h after E. chaffeensis infection compared to the transcriptional level before infection (0 h). UD, signal below detectable level.

For each set, the first primer is the forward primer and the second primer is the reverse primer.

RESULTS

Evaluation of the reproducibility and reliability of the oligonucleotide probe-based microarray experiments.

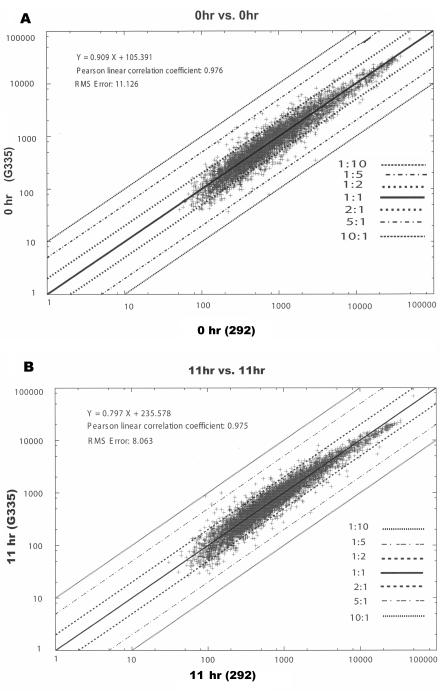

Oligonucleotide array hybridization reactions were performed twice on two separate occasions with RNA prepared from THP1 cells infected with E. chaffeensis. Genes with expression levels that changed in response to E. chaffeensis were selected on the basis of repeated differences in the expression levels of the treated and untreated samples across multiple time points. The data from two independent experiments were tightly clustered within |2|-fold changes, as determined by linear aggregation analysis. At each time point, linear regression analysis showed a slope of 0.909, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of >0.9 for each pairwise comparison (Fig. 1). This indicates that the data were linear and that data points from the two experiments were highly reproducible.

FIG. 1.

Reproducibility of the oligonucleotide array. The average differences for the data at 0 h (A) and 11 h (B) from experiment 1 versus the corresponding time course for experiment 2 were plotted by pairwise comparisons. The only criterion for inclusion was that the probe set was designated “present” in both time series. Least-square linear regression was used to determine the fit to a straight line. For the 0-h data set, the regression was described by the equation y = 1.172 x − 715.408 (r2 = 0.935), and for the 36-h data set, the equation was y = 1.198x − 741.671 (r2 = 0.911).

Hierarchical clustering algorithm analysis showed that the data generated in different arrays in independent time courses were tightly clustered at different time points and further confirmed the reproducibility of the results (data not shown).

The oligonucleotide probe-based microarrays used here contain several multiple probe sets, with oligonucleotides complementary to the same mRNAs. Altered expression of L24564, a Ras-related gene associated with diabetes, and U22376, a v-Myb myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog (avian), were each confirmed by consistent results from several independent probe sets targeted to different regions of their mRNAs. Several cases produced different results from different probe sets, which could reflect false positives, alternative mRNA splicing, or the different specificities and cross-hybridization possible with different probe sets.

Confirmation of gene transcription by RT-PCR.

RT-PCR amplification of monocyte transcripts was positive for interleukin-8 (IL-8), human apoptosis-related protein TFAR15, and E-selectin and L-selectin ligand sulfotransferase but was negative for human inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (Hiap1), IL-1α, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12α, IL-12β, IL-15, and IL-18. The results were consistent with the microarray results and confirmed the accuracy of our microarray data (Table 1).

Screening of oligonucleotide probe-based microarrays.

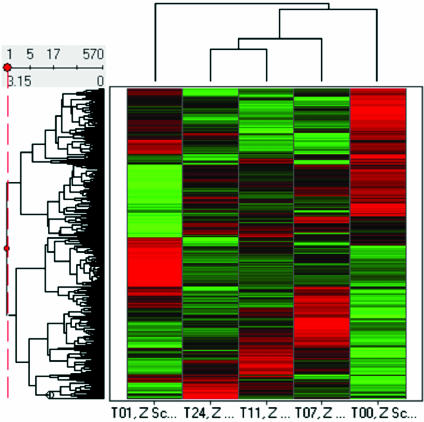

Biotin-labeled target cDNAs prepared from total RNA extracted from THP1 cells following exposure to E. chaffeensis for 1, 7, 11, and 24 h and uninfected control THP1 cells were hybridized to the HG-U95Av2 gene chip, containing 12,599 sequenced human genes. We plotted the number of genes whose expression changed by a factor of 3 (conservatively chosen to minimize the number of false positives) relative to that in uninfected cells. Of the 12,599 genes represented on the oligonucleotide array, 903 tested genes or ESTs were found to have a significant change (≥|3|-fold) in at least one of the comparisons during the 24-h infection period, corresponding to 7.2% (903 of 12,599) of the genes on the chip. After subtraction of the genes whose transcripts were detected at more than one time point of a single experiment, 570 genes of the monocytes had significantly changed transcriptional levels for at least one time point after E. chaffeensis infection, which is 4.5% of the total number of genes tested (Fig. 2; Tables 2 and 3). The numbers of genes with altered expression (induced/repressed) at 1, 7, 11, and 24 h were 284 (140/144), 236 (151/85), 218 (129/89), and 173 (101/72), respectively. The number of genes with a changed transcriptional level decreased while the infection was progressing. At the earliest time point (1 h), the number of genes that were upregulated was approximately equal to the number of genes that were downregulated. At the middle (7 and 11 h) and late (24 h) time points, upregulated genes predominated.

FIG. 2.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of 570 genes with threefold changes after exposure to E. chaffeensis. T00, T01, T11, and T24 represented 0, 1, 7, 11, and 24 h postinoculation. Z-score values are displayed colorimetrically from top to bottom. Line lengths in the dendrogram indicate the correlation of the genes, with shorter lines indicating higher levels of correlation. Genes induced by E. chaffeensis are indicated in red, and genes with reduced expression are indicated in green. The degree of redness represents the level of induction, whereas that of greenness represents the level of repression. Each column presents the expression of that gene at the indicated time point relative to uninfected THP1 cells. The complete data set was deposited at http://www.bioinfo.utmb.edu.

TABLE 2.

Macrophage gene transcription induced by E. chaffeensis infection

| Functional category or gene | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion and structure | |||

| CD58 | |||

| EMP2 | |||

| EMP3 | |||

| EPB41L3 | |||

| ICAM1 | |||

| PRPH | |||

| VIM | |||

| Apoptosis and cell proliferation | |||

| AJ011981 | |||

| ANXA1 | |||

| ARHGEF12 | |||

| BCL2A1 | |||

| BIRC3 | |||

| BTG2 | |||

| CCNE1 | |||

| CCNE2 | |||

| CD83 | |||

| CDC25A | |||

| CDC6 | |||

| CRIP1 | |||

| CTGF | |||

| CYBB | |||

| CYP1B1 | |||

| DNAJB1 | |||

| DSPG3 | |||

| EGR2 | |||

| EPS8 | |||

| FGF7 | |||

| FTH1 | |||

| HAS6591 | |||

| HSPA1A | |||

| HSPA6 | |||

| IER3 | |||

| IGFBP3 | |||

| LARGE | |||

| MCL1 | |||

| MDM2 | |||

| NCF1 | |||

| NFKBIA | |||

| PLA2G7 | |||

| PTGS2 | |||

| PTTG2 | |||

| PTX3 | |||

| RAB3IP3 | |||

| RELB | |||

| RGS2 | |||

| RRAD | |||

| SERPINE1 | |||

| SOD2 | |||

| SPAG6 | |||

| STATH | |||

| STC2 | |||

| TNFAIP6 | |||

| TNFRSF10B | |||

| TSSC3 | |||

| TUB | |||

| Immune response | |||

| AF070578a | |||

| CD48 | |||

| CORT | |||

| CYR61 | |||

| GRO1 | |||

| GRO2 | |||

| HUMRTVLH3 | |||

| ID2 | |||

| IFI30 | |||

| IGSF4 | |||

| IL1B | |||

| IL7R | |||

| IL8 | |||

| M59830 | |||

| NAF1 | |||

| NPTX1 | |||

| PEA15 | |||

| SCYA2 | |||

| SCYA2 | |||

| SCYA20 | |||

| SCYA4 | |||

| SCYA5 | |||

| SIX6 | |||

| TNF | |||

| TNFAIP2 | |||

| TNFAIP3 | |||

| TNFRSF9 | |||

| TRAF3 | |||

| Signal trasduction | |||

| ACVR2 | |||

| ADORA2B | |||

| AHR | |||

| C3AR1 | |||

| CNK | |||

| CYP27B1 | |||

| DUSP10 | |||

| DUSP14 | |||

| DUSP8 | |||

| EBI2 | |||

| EPHA2 | |||

| EPHB2 | |||

| F3 | |||

| FGR | |||

| FZD7 | |||

| GP1BA | |||

| GPR51 | |||

| HCK | |||

| HG3484-HT3678 | |||

| HSD11B1 | |||

| HTR1E | |||

| KCNAB1 | |||

| KCNN3 | |||

| KCNN4 | |||

| MD-2 | |||

| NPR3 | |||

| NR4A1 | |||

| PIM1 | |||

| PIM2 | |||

| PPM1A | |||

| PROCR | |||

| SCYA3 | |||

| SGK | |||

| WSX1 | |||

| DNA and protein binding | |||

| ANXA8 | |||

| ARHE | |||

| CHAF1B | |||

| CTNNBIP1 | |||

| GEM | |||

| ITIH2 | |||

| LGALS3 | |||

| MARCKS | |||

| NEBL | |||

| RAB36 | |||

| RIN1 | |||

| RPGR | |||

| RPP14 | |||

| S100A10 | |||

| SYT1 | |||

| TMPO | |||

| WARS | |||

| Oncogene | |||

| ERF | |||

| EXT1 | |||

| RB1 | |||

| FOSBa | |||

| Transporter | |||

| ATP2B1 | |||

| SLC11A2 | |||

| SLC17A4 | |||

| SLC31A1 | |||

| SLC7A7 | |||

| Transcription | |||

| CHD1L | |||

| CRIP2 | |||

| DSCR1 | |||

| E2F6 | |||

| EGR3 | |||

| ETR101 | |||

| ETV5 | |||

| ETV6 | |||

| GAS7 | |||

| JUN | |||

| JUNB | |||

| JUND | |||

| LOC51042 | |||

| MAF | |||

| MAFF | |||

| MEOX2 | |||

| MRPS10 | |||

| MSC | |||

| MTF1 | |||

| MYBL1 | |||

| NAB2 | |||

| NFE2L2 | |||

| NFE2L3 | |||

| NFKB1 | |||

| NFKB2 | |||

| NFKBIE | |||

| NMP200 | |||

| NR4A2a | |||

| OLIG2 | |||

| PCNA | |||

| PIR | |||

| PLAG1 | |||

| TFAP2A | |||

| ZFP36 | |||

| ZNF140 | |||

| ZNF202 | |||

| ZNF297B | |||

| Metabolism | |||

| ADAM17 | |||

| ADAM28 | |||

| ALAS1 | |||

| ALDH1A1 | |||

| ANXA2 | |||

| AQP9 | |||

| ASAH | |||

| CHST2 | |||

| CTSH | |||

| CTSZ | |||

| DPYD | |||

| DTYMK | |||

| ECGF1 | |||

| FACL2 | |||

| FADS3 | |||

| FUT3 | |||

| GCH1 | |||

| GGH | |||

| IDS | |||

| ME1 | |||

| MGAT2 | |||

| MMP9 | |||

| PDE5A | |||

| PLA2G4C | |||

| SAT | |||

| SLC1A5 | |||

| TJP2 | |||

| TPS1 | |||

| UGCG | |||

| UP | |||

| Miscellaneous | |||

| AA534868 | |||

| AD024 | |||

| ADAMDEC1 | |||

| ADFP | |||

| AI432401 | |||

| ATIP1 | |||

| BCL3 | |||

| BTG3 | |||

| CAPRI | |||

| COPEB | |||

| DRD1 | |||

| FGL2 | |||

| GPNMB | |||

| HG172-HT3924 | |||

| HRB2 | |||

| HRYa | |||

| J04755 | |||

| JTB | |||

| KPNA5 | |||

| LHX2 | |||

| LOC55884 | |||

| LPXN | |||

| M59287 | |||

| M62895 | |||

| MAPRE3 | |||

| OPTN | |||

| P8 | |||

| PER2 | |||

| PRAX-1 | |||

| QPCT | |||

| SCEL | |||

| SCO2 | |||

| SDC4 | |||

| V01512 | |||

| VLGR1 | |||

| XRCC3 | |||

| ESTs | |||

| AF027153 | |||

| AF038174 | |||

| AL049265 | |||

| AL080190 | |||

| DKFZP434J214 | |||

| DKFZP564D0462 | |||

| DKFZP566B183 | |||

| DKFZp586G0123 | |||

| FLJ10803 | |||

| FLRT2 | |||

| KIAA0186 | |||

| KIAA0189 | |||

| KIAA0379 | |||

| KIAA0410 | |||

| KIAA0429 | |||

| KIAA0507 | |||

| KIAA0690 | |||

| KIAA0951 | |||

| KIAA1564 | |||

| PSORT | |||

| Rab11-FIP2 | |||

| W26472 | |||

Transcription of the genes was induced and suppressed at different time points.

TABLE 3.

Macrophage gene transcription repressed by E. chaffeensis infection

| Functional category or gene |

|---|

| Adhesion and structure |

| ACTA1 |

| ADARB1 |

| ADD3 |

| CDH18 |

| COL4A1 |

| COL4A5 |

| COL9A3 |

| CTNNA1 |

| DMD |

| DSC2 |

| ITGA4 |

| LAMA4 |

| SELE |

| SPTBN1 |

| TGFA |

| THBS4 |

| TUBA1 |

| Apoptosis and cell proliferation |

| AP15 |

| ATP11A |

| BCL2 |

| BIK |

| BMP4 |

| BNIP3L |

| CDC14B |

| CDK5 |

| CDK8 |

| CIS4 |

| CORO2A |

| CSPG2 |

| DEFB1 |

| FLNA |

| FMO5 |

| GAGE1 |

| IGFBP2 |

| IGFBP4 |

| KEO4 |

| LOC58509 |

| LSP1 |

| MASP1 |

| MEST |

| MJD |

| MNDA |

| MYL1 |

| NCAM2 |

| OSR2 |

| PDCD4 |

| PIR51 |

| RFC5 |

| RFPL1S |

| RORB |

| SERPINB10 |

| SERPINB1 |

| SERPINB2 |

| SFRP1 |

| SIRPB1 |

| SPP1 |

| STAM2 |

| TIAF1 |

| TSN |

| VELI1 |

| Immune response |

| AF070578a |

| AL078636 |

| ATRN |

| CALCRL |

| CCR2 |

| CCR3 |

| CD1D |

| CDBA |

| CDC2 |

| CEACAM6 |

| CNR1 |

| CXCR4 |

| DEFA4 |

| FCGR2A |

| FER1L3 |

| FSHR |

| GFR |

| GLRB |

| IL13RA1 |

| IL15 |

| IL18 |

| IL8RB |

| ITK |

| KCNA4 |

| KCNAB1 |

| LILRA2 |

| MAPK9 |

| MS4A3 |

| OAS1 |

| P2RY2 |

| PAK1 |

| PAK2 |

| PAK7 |

| PRKACB |

| PRKCQ |

| PTPN22 |

| PTPRJ |

| RET |

| RPS6KA3 |

| RYR3 |

| SCYA23 |

| SLC15A1 |

| STK4 |

| TNFSF10 |

| TRG |

| TXK |

| ZW10 |

| DNA and protein binding |

| ABCC6 |

| AS3 |

| CRHBP |

| DLGAP1 |

| DMXL1 |

| FNBP3 |

| GTF2I |

| HYPE |

| ID1 |

| LYL1 |

| RGS1 |

| RPS26 |

| TAF6L |

| TF |

| TOP2B |

| ZNF261 |

| Vesicles |

| PACSIN2 |

| RAB5A |

| SNAP23 |

| STX16 |

| Oncogene |

| CAV1 |

| CHEK1 |

| CUL1 |

| LGI1 |

| MYB |

| MYB |

| RB1 |

| FOSBa |

| RAB27a |

| Transporter |

| NUP155 |

| RAB3-GAP150 |

| Transcription |

| ADAM10 |

| ADK |

| AF041259 |

| ALDH5A1 |

| ALDH6A1 |

| ART1 |

| ATP6V1A1 |

| B4GALT5 |

| BCKDHB |

| BDH |

| BS69 |

| CDKN1B |

| CDS2 |

| CPM |

| CTSG |

| D50419 |

| DHFR |

| DNASEIL1 |

| EIF2S3 |

| ELL2 |

| EPHX1 |

| FBP1 |

| FECH |

| GATA2 |

| GLUL |

| GNS |

| GSR |

| GSTA4 |

| GTF2B |

| GYG2 |

| HAL |

| HIVEP1 |

| IRF7 |

| KR18 |

| KYNU |

| LILRB1 |

| LOC51172 |

| MCFP |

| ME1 |

| MED6 |

| MME |

| MPI |

| MPO |

| MPST |

| MXI1 |

| MYC |

| NAALAD2 |

| NDUFB6 |

| NEDD4 |

| NFATC3 |

| NFE2 |

| PDE4D |

| PDE7A |

| PDGFRL |

| PGGT1B |

| PLU-1 |

| PPP1R8 |

| PPP2R1B |

| PRP17 |

| PRPS1 |

| RAD51 |

| RBM12 |

| RNAH |

| RNGTT |

| RPC32 |

| RRM2 |

| SLC26A2 |

| SMAP |

| SMARCA2 |

| SMARCA3 |

| SNAPC3 |

| SS18 |

| STAT1 |

| TFAP4 |

| TFDP1 |

| TRIP4 |

| TRIP8 |

| U31248 |

| U37251 |

| U95044 |

| UBE2D1 |

| UGT2B15 |

| XDH |

| Miscellaneous |

| AF007155 |

| AL022398 |

| BCL11A |

| C18orf1 |

| CCNG1 |

| CG012 |

| CHN2 |

| DNAJB12 |

| DNC12 |

| DO |

| DPYSL4 |

| DRD1 |

| F8 |

| FACVL1 |

| HG2259-HT2348 |

| HG2510-HT2606 |

| HG3523-HT4899 |

| HG4679-HT5104 |

| HIRIP3 |

| HIS1 |

| HRYa |

| HS2ST1 |

| ITM2B |

| KIF2 |

| KIF5B |

| LOC51097 |

| LRMP |

| MDM4 |

| NCALD |

| NCK1 |

| NCOA2 |

| NR4A2a |

| OMD |

| OSBPL1A |

| P311 |

| PCTAIRE2BP |

| PLOD2 |

| RASGRP2 |

| RPE |

| SIX3 |

| SKD1 |

| SNX7 |

| STAR |

| STHM |

| TM75F2 |

| TXNIP |

| Y43374 |

| U43604 |

| U90916 |

| W28319 |

| W87466 |

| X55989 |

| ESTs |

| AA143021 |

| AF052146 |

| AL050151 |

| AW043812 |

| CG018 |

| DKFZp566D133 |

| DKFZP586A0522 |

| DKFZP586G011 |

| GASC1 |

| HSU84971 |

| KIAA0096 |

| KIAA0193 |

| KIAA0241 |

| KIAA0390 |

| KIAA0493 |

| KIAA0628 |

| KIAA0711 |

| KIAA0712 |

| KIAA0746 |

| KIAA0752 |

| KIAA0828 |

| KIAA0869 |

| KIAA0918 |

| KIAA0924 |

| KIAA0930 |

| KIAA1128 |

| KIAA1405 |

| L39064 |

| LOC63923 |

| U79277 |

| W28589 |

| W72239 |

We further analyzed the data by classifying threefold-regulated genes by their primary functions. Although no single biochemical process could be identified, the profiles of host cell gene transcripts included those for proteins inhibiting apoptosis and regulating cell differentiation, signal transduction and transcription factors, proinflammatory cytokines, biosynthesis and metabolism, membrane trafficking, adhesion, and structure. The transcription of genes related to the immune response to E. chaffeensis infection and intracellular survival of E. chaffeensis was particularly interesting and is described in detail below.

Immune response to E. chaffeensis infection.

At the early and middle stages of infection (1 to 7 h), E. chaffeensis induced transcription of monocyte genes for IL-1β, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor beta (TNF-β). Transcription of monocyte genes for small inducible cytokines such as A3, A4, A5 (RANTES), and Cys-Cys member 20 was induced 1 to 11 h after infection, and A4 transcription was induced at all time points.

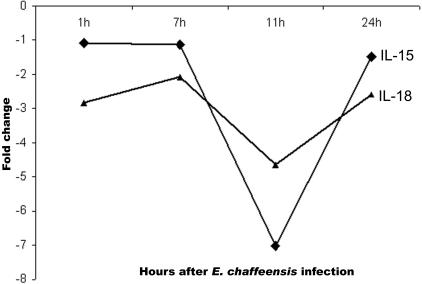

E. chaffeensis repressed monocyte gene transcription of IL-15, IL-18 (Fig. 3 ), and small inducible cytokine subfamily A (Cys-Cys) member 23. The transcription of IL-10 and IL-12 in monocytes was not changed after E. chaffeensis infection.

FIG. 3.

Repression of transcription of IL-15 and IL-18 genes by E. chaffeensis.

Cytokine receptors were generally repressed by E. chaffeensis infection. These receptors included chemokine (C-C motif) receptors 2, 3, and 4, IL-8 receptor, and IL-13 receptor. IL-7 receptor was the only cytokine receptor of monocytes that was induced by E. chaffeensis.

Membrane trafficking.

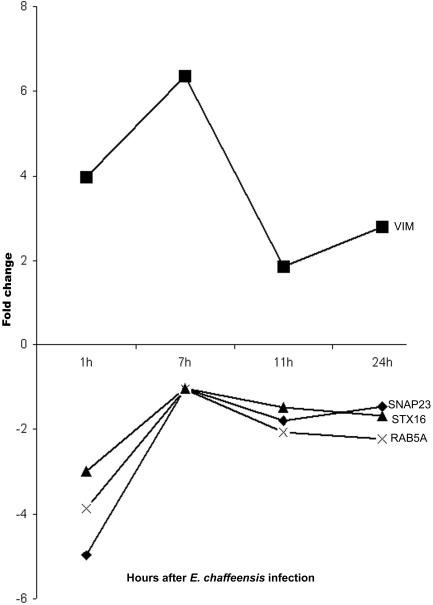

Molecules mediating vesicle docking were generally repressed by E. chaffeensis. E. chaffeensis repressed the transcription of SNAP23 (synaptosomal-associated protein; 23 kDa), Rab5A (member of RAS oncogene family), and STX16 (syntaxin 16) significantly (>|3|-fold) during early infection (1 h). The genes for these proteins were also repressed at the later time points, but to a lesser extent (twofold). Vimentin, a reservoir for SNAP23, was induced 1 to 7 h after E. chaffeensis infection (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Regulation of gene transcription of proteins involved in vesicle docking by E. chaffeensis.

Apoptosis.

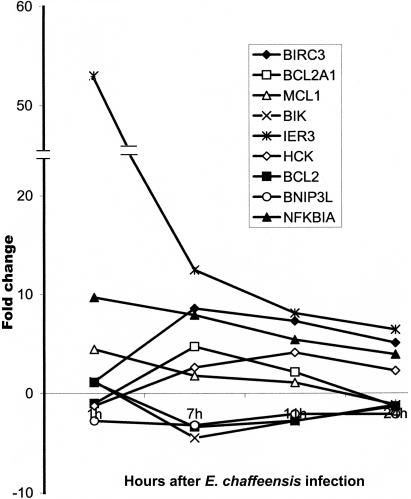

Apoptosis inhibitors were generally induced by E. chaffeensis infection of monocytes. NF-κB (NFKBIA) gene transcription was induced in monocytes at all time points after E. chaffeensis infection. Apoptosis inhibitor IER3 (immediately early response 3) was induced significantly at all time points, with a peak 1 h after infection. BirC3 (baculoviral IAP repeat-containing protein 3) was significantly induced from 7 to 24 h, with a peak at 7 h, after E. chaffeensis infection. The BCL2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) and BCL2-related proteins (MCL1 and BCL2A1) were differentially transcribed. MCL1 was induced in the first hour, and BCL2A1 was induced at 7 h. BCL2 was repressed at 7 h. Apoptosis inducers such as BIK (BCL2-interacting killer) and BNIP3L (BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19-kDa interacting protein 3-like) were downregulated at 7 h (Fig. 5). The transcription of caspase genes was not changed in monocytes after E. chaffeensis infection. Apoptosis inducer hematopoietic cell kinase (HCK) was upregulated from 7 to 24 h, peaking at 11 h.

FIG. 5.

Differential regulation of gene transcription of apoptosis inhibitors and inducers by E. chaffeensis.

Signal transduction and cell proliferation.

E. chaffeensis downregulated many protein kinases. E. chaffeensis inhibits TXK (a tyrosine kinase), ITK (IL-2-inducible T-cell kinase), and RET transcription at all the time points studied during infection. Three p21-activated kinase genes (PAK1, -2, and -7) and STK4 (serine/threonine protein kinase Krs-2) were repressed 1 h after exposure to E. chaffeensis. CNK (cytokine-inducible kinase) was induced 1 h after exposure to E. chaffeensis but was repressed at other time points. Both JAK1 and STAT1 were downregulated during the first hour after E. chaffeensis infection. EPHA2 and DRT (developmentally regulated EPH-related tyrosine kinase) were induced at the earliest stage (1 h) and repressed at later stages (7, 11, and 24 h) of infection.

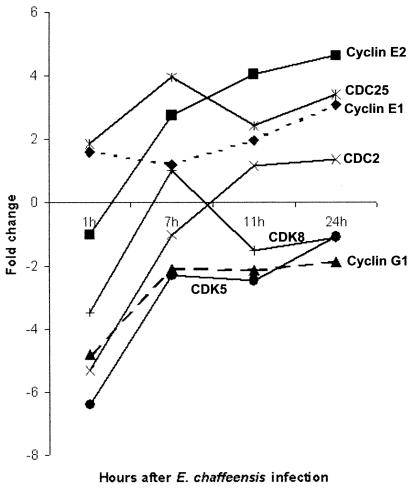

Many genes involved in controlling cell cycles in monocytes changed expression levels during E. chaffeensis infection. In the first hour postinfection, E. chaffeensis downregulated CDC2 (cell division cycle 2), CDK5 (cyclin-dependent kinase 5), CDK8, and cyclin G1. From 7 to 24 h postinfection, E. chaffeensis upregulated cyclin E1, cyclin E2, and CDC25 (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Differential regulation of gene transcription of proteins involved in the cell cycle by E. chaffeensis.

DISCUSSION

We have analyzed the global gene transcriptional profile of human monocytes in response to E. chaffeensis infection by using oligonucleotide arrays. Our data provide evidence of differential expression of monocyte genes 1, 7, 11, and 24 h after infection with E. chaffeensis. E. chaffeensis infection altered the transcription of a wide range of genes across the host genome (4.5%), despite the fact that E. chaffeensis develops exclusively inside a vacuolar inclusion separated from the cytosol of the host cell by a host membrane. Considering the nature and scope of these differentially transcribed genes, the interaction between E. chaffeensis and the host cell is far more complex than simply fulfilling the metabolic needs of E. chaffeensis. E. chaffeensis infection results in profound changes in the transcription of host cell genes encoding proteins involved in biosynthesis and metabolism, ion channel transport, regulation of cell differentiation, signal transduction and transcription, inflammation, and membrane trafficking. From the point of view of pathogenesis, the most important changes in the host cell caused by E. chaffeensis infection are downregulation of the innate immune system and a differentially regulated cell cycle.

The most striking feature of E. chaffeensis infection is repression of host cell cytokines that modulate innate and adaptive immunity to intracellular bacteria. E. chaffeensis avoids stimulation of IL-12 production and represses IL-15 and IL-18 production. These cytokines play fundamental roles in stimulating NK cells and T helper 1 cells to produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ), which then activates macrophages to kill phagocytosed bacteria. IL-12 and IL-15 also activate NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes to kill cells infected with intracellular bacteria. Thus, repression of IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18 may help E. chaffeensis to evade host innate and adaptive immunity. Another intracellular bacterium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (26), and the intracellular protozoan and fungus Leishmania major (9) and Histoplama capsulatum (23) inhibit IL-12 production. Thus, intracellular pathogens may have convergently evolved the ability to survive inside the macrophage by repressing IL-12 production.

Apoptosis is an innate mechanism of host defense used to prevent proliferation of internalized bacteria (31). Intracellular bacteria usually grow very slowly and require several days of intracellular replication. Thus, intracellular bacteria such as M. tuberculosis (5, 30), Chlamydia trachomatis (18), Rickettsia rickettsii (10), and Anaplasma phagocytophilum (37) have all evolved different mechanisms to inhibit host cell apoptosis during the early stages of infection to gain time for growth within host cells. E. chaffeensis induces the production of apoptosis inhibitors such as NF-κB, BCL2A1, BIRC3, IER3, and MCL1. In the early stage of infection (7 h), E. chaffeensis represses the BCL2 antagonists BIK and BNIP3L, which induce apoptosis by inactivating BCL2 proteins (8). The expression of BCL2 proteins and their antagonists returns to normal levels gradually in the late stages of infection. However, HCK is induced during the late stages of infection. The HCK SH3 domain mediates signaling at the plasma membrane, triggering a pathway leading to caspase-3-dependent cytochrome c release and apoptosis (29). NF-κB stimulates cell proliferation by activating cellular transcription. R. rickettsii blocks host cell apoptosis through activation of the NF-κB prosurvival signaling pathway (10). Prosurvival members of the BCL2 family (BCL2, BCL2A1, and MCL1) prevent apoptosis by maintaining the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane and thus preventing the release of cytochrome c, which binds to apoptotic protease-activating factor 1, resulting in activation of the apoptosis pathway (19, 31, 40). C. trachomatis inhibits host cell apoptosis by blocking the BCL2 pathway. It will be interesting to investigate whether E. chaffeensis inhibits apoptosis during the early stage of infection by regulating the mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, since our data suggest that E. chaffeensis blocks the BCL2 pathway.

E. chaffeensis survival within the macrophage depends on its ability to inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion. After ingestion by a macrophage, E. chaffeensis lives in a vacuole containing early endosomal markers, such as EEA1, but not lysosomal markers, such as LAMP1 (25). Thus, E. chaffeensis lives in an early endosome and inhibits the maturation of the endosome to evade destruction by lysosomal enzymes. The mechanism that E. chaffeensis employs to inhibit the maturation of the endosome is not understood. A current model of vesicle fusion is explained by the SNARE hypothesis. According to the SNARE hypothesis, docking and fusion of vesicles with the plasma membrane are mediated by the specific interaction of vesicle proteins (v-SNARE and SNAR receptor) with the target plasma membrane protein (t-SNARE) (34). Among the proteins implicated are syntaxins, which have at least 16 members, synaptosome-associated proteins (SNAPs), of which the two best known are SNAP25 and SNAP23, and other proteins. These proteins form a complex that juxtaposes the two membranes to be fused. This interaction is regulated by Rab5, a small GTPase of the Rab family. Depletion of Rab5 inhibits the fusion of the phagosome containing Listeria monocytogenes with lysosomes (2). SNAP23 has been demonstrated to interact with different syntaxins in different types of cells (22, 24). Our data show that E. chaffeensis represses the production of Rab5, SNAP23, and STX16 (syntaxin 16) at all times during infection, most dramatically during the first hour of infection. E. chaffeensis induces the production of vimentin, a reservoir for SNAP23 (17). Thus, E. chaffeensis may inhibit phagosome-lysosome fusion by regulating the concentration of Rab5 and SNAPs in the macrophage.

Protein kinases are essential elements of signal transduction pathways that control fundamental cellular processes, including growth, differentiation, and cytoskeletal function. Protein kinases are activated by phosphorylation of tyrosine, serine, or threonine residues and are inactivated by dephosphorylation by protein phosphatases. E. chaffeensis infection regulated 55 protein kinase and kinase-related genes of the host cells.

E. chaffeensis infection downregulated protein kinases involving cell mobility and cytoskeletal changes, such as ITK, TXK, and PAKs. ITK and TXK were inhibited by E. chaffeensis at all times during infection. ITK and TXK are nonreceptor tyrosine kinases of the Tec family. ITK regulates TCR/CD3-induced actin cytoskeletal events (20). The expression of ITK was thought to be restricted to T lymphocytes, NK cells, and mast cells (36). TXK binds to the IFN-γ gene promoter region that regulates IFN-γ gene transcription (32). PAK1, PAK2, and PAK7 were downregulated during the first hour of infection. PAKs (p21-activated kinases) serve as important regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics and cell mobility, transcription through mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades, death and survival signaling, and cell cycle progression (7).

E. chaffeensis inhibits the JAK-STAT pathway. JAK1 and STAT1 were repressed at the early stage (1 h) of E. chaffeensis infection. The JAK-STAT pathway has a fundamental role in cytokine signaling. JAKs bind specifically to intracellular domains of cytokine receptor signaling chains and phosphorylate themselves and tyrosine residues on the receptor, creating docking sites for the SH2 domains of STATs. The receptor-bound STAT is then phosphorylated at a tyrosine residue. Phosphorylation of STAT leads to STAT homo- and heterodimer formation dependent on the intermolecular SH2-phosphotyrosine interaction. STAT dimers are rapidly transported from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and are involved in DNA binding. The ligands for receptors which bind JAKs include IFN-α, -β, and -γ, IL-2 to -7, -10 to -13, and -15, and erythropoietin, growth hormone, prolactin, thrombopoietin, and other polypeptides (1, 11). Therefore, E. chaffeensis may inhibit activation of macrophages by interferons and interleukins by downregulating the JAK-STAT pathway.

E. chaffeensis inhibits cyclin and CDC2-related protein kinases (CDKs). The cell cycles of eukaryotes are controlled by multiple cyclins and multiple CDKs. E. chaffeensis downregulates CDC2, CDK5, CDK8, and cyclin G1 during the early stage of infection. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, passage through START is controlled by CDC2 in association with cyclin G1. Thus, E. chaffeensis may arrest the host cell in the G1 stage during the early stages of infection. The early-stage inhibition of host cell growth may help E. chaffeensis to establish itself inside the cell during the initial stages of infection. In the late stages of infection, however, E. chaffeensis upregulates cell proliferation to prevent the cell from dying due to progressive infection. This hypothesis is supported by our data that E. chaffeensis upregulates cyclin E and CDC25 in the late stages of infection. Cyclin E is expressed later in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and plays a role in the G1-to-S phase transition and initiation of DNA synthesis.

E. chaffeensis downregulates JNK2 (MAPK9) during the early stage of infection and upregulates DUSP8 and -14 (dual-specificity phosphatase), which dephosphorylate and inactivate JNK2. JNK2 is a member of the MAP kinases. JNK2 phosphorylates the DNA binding protein Jun and increases its transcriptional activity. Jun is a component of the AP-1 transcription factor, which activates transcription of a number of genes in response to environmental stress, radiation, and growth factors (21). JNKs are important in controlling apoptosis. The absence of JNK causes a defect in the mitochondrial death signaling pathway by inhibiting cytochrome c release (33). E. chaffeensis may inhibit cell transcriptional activity during the early stage of infection and/or inhibit apoptosis through downregulation of MAP kinase pathways, thus impairing host cell defenses and maintaining a prolonged growth opportunity for ehrlichiae.

Other protein kinases are downregulated in the first hour of infection by E. chaffeensis, including ADK, CNK, EPHA2, EPHB2, and STK4. ADK is involved in ribonucleoside monophosphate biosynthesis. CNK is required for Raf activation (4). The EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase critically regulates tumor cell growth, migration, and invasiveness (28). A primary function of EphB2, a member of the most populous family of receptor tyrosine kinases, is to inactivate the Ras-MAP kinase pathway in a fashion that contributes to cytoskeletal reorganization and adhesion responses in neuronal growth cones (15).

A previous study compared the transcriptional profiles of macrophages infected with mycobacteria, gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium), and gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus and L. monocytogenes) and identified shared transcriptional responses among the bacteria, consisting of 132 induced genes and 59 repressed genes (9). Despite the fact that a similar number of genes changed transcriptional levels in macrophages infected with E. chaffeensis and macrophages infected with other bacteria, the transcriptional profile of E. chaffeensis-infected macrophages differed remarkably from that of macrophages infected with other bacteria, as mentioned above. In comparing the shared transcriptional response of macrophages infected with other bacteria and that of macrophages infected with E. chaffeensis, we have identified only a few genes that are commonly induced by E. chaffeensis and the other bacteria and found no shared repressed genes. The commonly induced genes include those involved in the innate immune response and the stress response (IL-8, IL-7R, and SOD2), transcription (JunB, NFKBIA, and NFKBIE), and cell adhesion (ICAM1). It is very interesting that another intracellular bacterium, Brucella abortus, also inhibits macrophage transcription of various genes involved in apoptosis, cell cycling, and intracellular vesicular trafficking (16), although E. chaffeensis and B. abortus inhibited different genes involved in these processes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S. Wesley Long and David H. Walker for discussions of the manuscript.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI45871).

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aaronson, D. S., and C. M. Horvath. 2002. A road map for those who know JAK-STAT. Science 296:1653-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Dominguez, C., A. M. Barbieri, W. Beron, A. Wandinger-Ness, and P. D. Stahl. 1996. Phagocytosed live Listeria monocytogenes influences Rab5-regulated in vitro phagosome-endosome fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 271:13834-13843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, B. E., K. G. Sims, J. G. Olson, J. E. Childs, J. F. Piesman, C. M. Happ, G. O. Maupin, and B. J. Johnson. 1993. Amblyomma americanum: a potential vector of human ehrlichiosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 49:239-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anselmo, A. N., R. Bumeister, J. M. Thomas, and M. A. White. 2002. Critical contribution of linker proteins to Raf kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5940-5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balcewicz-Sablinska, M. K., J. Keane, H. Kornfeld, and H. G. Remold. 1998. Pathogenic Mycobacterium tuberculosis evades apoptosis of host macrophages by release of TNF-R2, resulting in inactivation of TNF-alpha. J. Immunol. 161:2636-2641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnewall, R. E., Y. Rikihisa, and E. H. Lee. 1997. Ehrlichia chaffeensis inclusions are early endosomes which selectively accumulate transferrin receptor. Infect. Immun. 65:1455-1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokoch, G. M. 2003. Biology of the p21-activated kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72:743-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyd, J. M., G. J. Gallo, B. Elangovan, A. B. Houghton, S. Malstrom, B. J. Avery, R. G. Ebb, T. Subramanian, T. Chittenden, R. J. Lutz, et al. 1995. Bik, a novel death-inducing protein shares a distinct sequence motif with Bcl-2 family proteins and interacts with viral and cellular survival-promoting proteins. Oncogene 11:1921-1928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrera, L., R. T. Gazzinelli, R. Badolato, S. Hieny, W. Muller, R. Kuhn, and D. L. Sacks. 1996. Leishmania promastigotes selectively inhibits interleukin 12 induction in bone marrow-derived macrophages from susceptible and resistant mice. J. Exp. Med. 183:515-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clifton, D. R., R. A. Goss, S. K. Sahni, D. van Antwerp, R. B. Baggs, V. J. Marder, D. J. Silverman, and L. A. Sporn. 1998. NF-kappa B-dependent inhibition of apoptosis is essential for host cell survival during Rickettsia rickettsii infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4646-4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darnell, J. E., Jr. 1997. STATs and gene regulation. Science 277:1630-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson, W. R., J. M. Lockhart, D. E. Stallknecht, E. W. Howerth, J. E. Dawson, and Y. Rechav. 2001. Persistent Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in white-tailed deer. J. Wildl. Dis. 37:538-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson, J. E., B. E. Anderson, D. B. Fishbein, J. L. Sanchez, C. S. Goldsmith, K. H. Wilson, and C. W. Duntley. 1991. Isolation and characterization of an Ehrlichia sp. from a patient diagnosed with human ehrlichiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2741-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson, J. E., and S. A. Ewing. 1992. Susceptibility of dogs to infection with Ehrlichia chaffeensis, causative agent of human ehrlichiosis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 53:1322-1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elowe, S., S. J. Holland, S. Kulkarni, and T. Pawson. 2001. Downregulation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway by the EphB2 receptor tyrosine kinase is required for ephrin-induced neurite retraction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7429-7441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eskra, L., A. Mathison, and G. Splitter. 2003. Microarray analysis of mRNA levels from RAW264.7 macrophages infected with Brucella abortus. Infect. Immun. 71:1125-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faigle, W., E. Colucci-Guyon, D. Louvard, S. Amigorena, and T. Galli. 2000. Vimentin filaments in fibroblasts are a reservoir for SNAP23, a component of the membrane fusion machinery. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3485-3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan, T., H. Lu, H. Hu, L. Shi, G. A. McClarty, D. M. Nance, A. H. Greenberg, and G. Zhong. 1998. Inhibition of apoptosis in Chlamydia-infected cells: blockade of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation. J. Exp. Med. 187:487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao, L. Y., and Y. A. Kwaik. 2000. The modulation of host cell apoptosis by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 8:306-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grasis, J. A., C. D. Browne, and C. D. Tsoukas. 2003. Inducible T cell tyrosine kinase regulates actin-dependent cytoskeletal events induced by the T cell antigen receptor. J. Immunol. 170:3971-3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, G. L., and R. Lapadat. 2002. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 298:1911-1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazo, P. A., M. Nadal, M. Ferrer, E. Area, J. Hernandez-Torres, S. M. Nabokina, F. Mollinedo, and X. Estivill. 2001. Genomic organization, chromosomal localization, alternative splicing, and isoforms of the human synaptosome-associated protein-23 gene implicated in vesicle-membrane fusion processes. Hum. Genet. 108:211-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marth, T., and B. L. Kelsall. 1997. Regulation of interleukin-12 by complement receptor 3 signaling. J. Exp. Med. 185:1987-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Martin, B., S. M. Nabokina, P. A. Lazo, and F. Mollinedo. 1999. Co-expression of several human syntaxin genes in neutrophils and differentiating HL-60 cells: variant isoforms and detection of syntaxin 1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65:397-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mott, J., R. E. Barnewall, and Y. Rikihisa. 1999. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and Ehrlichia chaffeensis reside in different cytoplasmic compartments in HL-60 cells. Infect. Immun. 67:1368-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nau, G. J., J. F. Richmond, A. Schlesinger, E. G. Jennings, E. S. Lander, and R. A. Young. 2002. Human macrophage activation programs induced by bacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:1503-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paddock, C. D., and J. E. Childs. 2003. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prototypical emerging pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:37-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pratt, R. L., and M. S. Kinch. 2002. Activation of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase stimulates the MAP/ERK kinase signaling cascade. Oncogene 21:7690-7699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radha, V., C. Sudhakar, P. Ray, and G. Swarup. 2002. Induction of cytochrome c release and apoptosis by Hck-SH3 domain-mediated signalling requires caspase-3. Apoptosis 7:195-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas, M., M. Olivier, P. Gros, L. F. Barrera, and L. F. Garcia. 1999. TNF-alpha and IL-10 modulate the induction of apoptosis by virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis in murine macrophages. J. Immunol. 162:6122-6131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sly, L. M., S. M. Hingley-Wilson, N. E. Reiner, and W. R. McMaster. 2003. Survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in host macrophages involves resistance to apoptosis dependent upon induction of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Mcl-1. J. Immunol. 170:430-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeba, Y., H. Nagafuchi, M. Takeno, J. Kashiwakura, and N. Suzuki. 2002. Txk, a member of nonreceptor tyrosine kinase of Tec family, acts as a Th1 cell-specific transcription factor and regulates IFN-gamma gene transcription. J. Immunol. 168:2365-2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tournier, C., P. Hess, D. D. Yang, J. Xu, T. K. Turner, A. Nimnual, D. Bar-Sagi, S. N. Jones, R. A. Flavell, and R. J. Davis. 2000. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science 288:870-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber, T., B. V. Zemelman, J. A. McNew, B. Westermann, M. Gmachl, F. Parlati, T. H. Sollner, and J. E. Rothman. 1998. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell 92:759-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss, E., J. C. Williams, G. A. Dasch, and Y. H. Kang. 1989. Energy metabolism of monocytic Ehrlichia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:1674-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang, W. C., Y. Collette, J. A. Nunes, and D. Olive. 2000. Tec kinases: a family with multiple roles in immunity. Immunity 12:373-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshiie, K., H. Y. Kim, J. Mott, and Y. Rikihisa. 2000. Intracellular infection by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 68:1125-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu, X. J., P. A. Crocquet-Valdes, L. C. Cullman, V. L. Popov, and D. H. Walker. 1999. Comparison of Ehrlichia chaffeensis recombinant proteins for serologic diagnosis of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2568-2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu, X. J., J. W. McBride, C. M. Diaz, and D. H. Walker. 2000. Molecular cloning and characterization of the 120-kilodalton protein gene of Ehrlichia canis and application of the recombinant 120-kilodalton protein for serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:369-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou, P., L. Qian, K. M. Kozopas, and R. W. Craig. 1997. Mcl-1, a Bcl-2 family member, delays the death of hematopoietic cells under a variety of apoptosis-inducing conditions. Blood 89:630-643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]