Abstract

Definitive endoderm differentiation is crucial for generating respiratory and gastrointestinal organs including pancreas and liver. However, whether epigenetic regulation contributes to this process is unknown. Here, we show that the H3K27me3 demethylases KDM6A and KDM6B play an important role in endoderm differentiation from human ESCs. Knockdown of KDM6A or KDM6B impairs endoderm differentiation, which can be rescued by sequential treatment with WNT agonist and antagonist. KDM6A and KDM6B contribute to the activation of WNT3 and DKK1 at different differentiation stages when WNT3 and DKK1 are required for mesendoderm and definitive endoderm differentiation, respectively. Our study not only uncovers an important role of the H3K27me3 demethylases in definitive endoderm differentiation, but also reveals that they achieve this through modulating the WNT signaling pathway.

Keywords: KDM6A/KDM6B, definitive endoderm differentiation, WNT pathway regulation

Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are promising sources for cell therapy due to their pluripotency and unlimited self-renewal capacity1. Definitive endoderm differentiation is the first critical step for generating respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts as well as all of their associated organ/tissues including pancreas and liver2. Segregation of endoderm germ layer from mesoderm and ectoderm is one of the first cell fate decisions made in development. Definitive endoderm induction is controlled by the evolutionarily conserved Nodal/TGF-β signaling pathway2,3. Activin A is a key induction factor for ESC differentiation into definitive endoderm lineages4,5. In addition, molecules of other signaling pathways including WNT, FGF, BMP and PI3K have also been shown to contribute to endoderm differentiation6. Interestingly, different human ESC lines also exhibit different lineage-specific differentiation capacity due to the genetic and epigenetic differences7. Although growth factors, such as activin A, can effectively induce definitive endoderm differentiation from human ESCs, the underlying mechanism, particularly the epigenetic mechanism is largely unknown.

Histone methylation plays an important role in diverse biological processes including transcription8. Although histone methylation can function in both gene activation and repression, Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)-mediated histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) has been mainly linked to transcription repression9. Given the role of H3K27 methylation in silencing lineage-specific differentiation genes in ESCs and that H3K27me3 mark can be actively removed by demethylases, H3K27me3 demethylases likely play an important role in driving ESC differentiation. Indeed, KDM6A (also named UTX) and KDM6B (also named JMJD3) have been shown to be involved in transcriptional activation in normal development10,11,12,13. Recently, Kdm6a and Kdm6b also have been shown to play an important role in cardiac14 and M2 macrophage15 development, respectively. Previous studies have revealed that ESCs contain bivalent chromatin domains that harbor both repressive (H3K27me3) and active (H3K4me3) marks and these bivalent domains play important roles in maintaining the balance between self-renewal and differentiation16,17,18. Here we demonstrate that KDM6A and KDM6B contribute to definitive endoderm differentiation by modulating the WNT signaling pathway.

Results and Discussion

H3K27me3 demethylases KDM6A and KDM6B are upregulated upon definitive endoderm differentiation

Consistently, we found that the expression levels of definitive endoderm genes are markedly increased while pluripotency genes are greatly reduced upon activin A treatment of the HUES8 ESCs (Supplementary information, Figure S1A-S1B). Because activin A-induced differentiation does not generate homogenous cell population (Supplementary information, Figure S1B), we used CD184 (also named CXCR4), a well-known definitive endoderm marker4,19,20,21, to sort the cell population and confirmed successful endoderm differentiation by RT-qPCR analysis (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). In addition to CD184, another report20 used both CD184 and CD117 (also named c-KIT) to mark the definitive endoderm cell population. Interestingly, we found that CD184+ cells are almost always CD117+ in our differentiation system (Supplementary information, Figure S1D). These analyses confirm that CD184 can serve as a marker for definitive endoderm differentiation in our human ESC differentiation system.

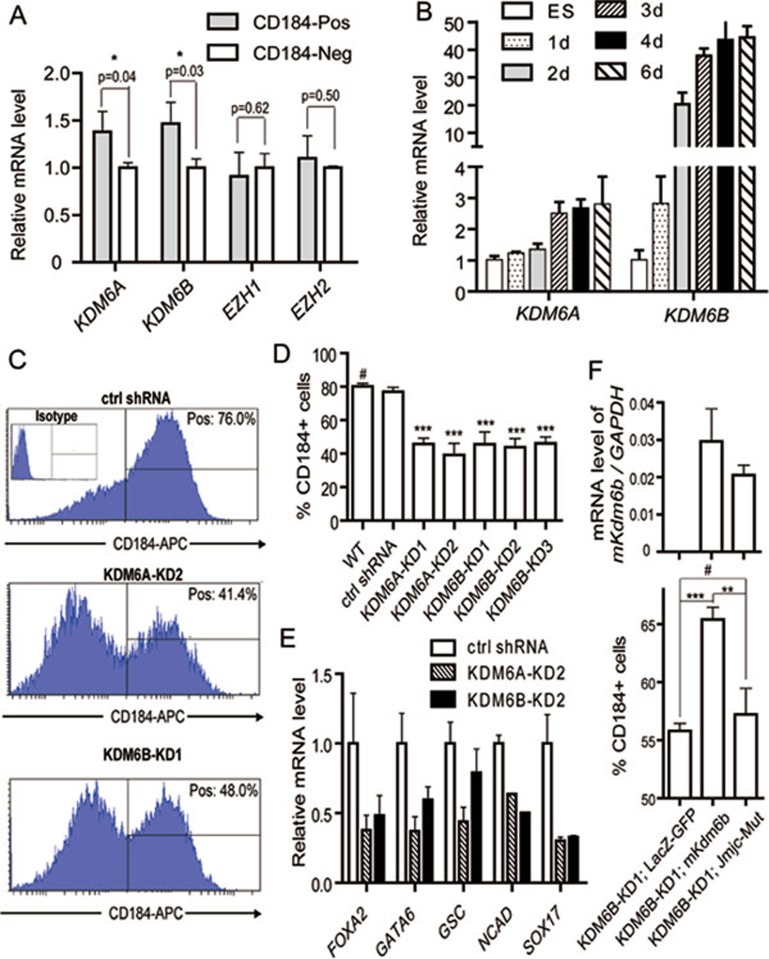

To explore a potential role of H3K27me3-related enzymes in definitive endoderm differentiation, we asked whether these enzymes are enriched in purified definitive endoderm cells. RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates both KDM6A and KDM6B levels are significantly higher in CD184-positive cells compared to that in CD184-negative cell population (Figure 1A, P < 0.05). In contrast, no significant difference in the level of EZH1 or EZH2 is detected between these two cell populations (Figure 1A). Consistent with a potential role of KDM6A and KDM6B in endoderm differentiation, we found that both are upregulated (> 20-fold for KDM6B and ∼3-fold for KDM6A) during endoderm differentiation (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

KDM6A and KDM6B contribute to definitive endoderm differentiation from human ESCs. (A) 4 days after differentiation, CD184-positive definitive endoderm cells and CD184-negative cells were analyzed to compare the gene expression levels of H3K27me3 methyltransferases (EZH1 and EZH2) and demethylases (KDM6A and KDM6B). The P values are derived from three independent experiments. The expression level in CD184-negative cells is set as 1. (B) Relative expression levels of KDM6A and KDM6B during 6-day activin A-induced definitive endoderm differentiation. The expression level in undifferentiated human ESCs is set as 1. (C) Representative flow cytometric data showing the percentage of CD184-positive cells in control and KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown ESCs upon 4-day definitive endoderm differentiation. (D) Quantification of the CD184-positive cell populations in control and KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown ESCs upon 4-day definitive endoderm differentiation. The statistical values are # P > 0.05; *** P < 0.001. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression levels of endoderm markers in control and KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown human ESCs upon 4-day definitive endoderm differentiation. (F) Enforced expression of wild-type mouse Kdm6b, but not its catalytic mutant, could rescue the endoderm differentiation defect of KDM6B knockdown. Upper panel showed similar exogeneous expression levels of wild-type and mutant Kdm6b; lower panel showed percentage of CD184-positive cells in KDM6B knockdown cells transfected with control, wild-type or catalytic mutant mouse Kdm6b upon 4-day activin A treatment. The statistical values are # P> 0.05; ** P< 0.01; *** P< 0.001.

KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown impairs definitive endoderm differentiation

To explore a potential role of KDM6A and KDM6B in endoderm differentiation, we generated lentiviral shRNA knockdown constructs that target KDM6A or KDM6B, and established stable KDM6A and KDM6B knockdown cell lines. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that we achieved 60%-70% of knockdown in these cell lines (Supplementary information, Figure S2). To evaluate whether knockdown of KDM6A or KDM6B affects definitive endoderm differentiation, we subjected the KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown cell lines to activin A treatment. FACS analysis indicated that KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown cell lines exhibited lower percentage of CD184-positive cells compared to the control (Figure 1C-1D) indicating impairment of endoderm differentiation. Consistently, RT-qPCR analysis revealed decreased expression of endoderm marker genes, such as FOXA2, GATA6, GSC, NCAD and SOX17, upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown (Figure 1E). FACS analysis and immunofluorescence staining further confirmed impairment in endoderm differentiation upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown (Supplementary information, Figure S3). To demonstrate that the knockdown effect is specific and to evaluate whether the H3K27me3 demethylase activity of KDM6 is required for efficient endoderm differentiation, we attempted to rescue the endoderm differentiation defects with wild-type and catalytic mutant mouse Kdm6b. Results shown in Figure 1F demonstrate that wild-type, but not the catalytic mutant, Kdm6b partially rescued the endoderm differentiation defect. This result not only confirms the knockdown specificity, but also indicates that the demethylase activity of KDM6 is important for endoderm differentiation.

Defective endoderm differentiation is linked to defective WNT signaling

The fact that KDM6A or KDM6B depletion impairs definitive endoderm differentiation prompted us to ask whether the defect is caused by defective ESC maintenance. Characterization of the KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown ESCs revealed that they exhibit normal human ESC morphology, and express pluripotency markers such as NANOG, SOX2, SSEA4 and OCT4 (Supplementary information, Figure S4A and S4C). RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates that the expression levels of pluripotency genes or the three germ layer lineage markers are not significantly altered in the KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown cells (Supplementary information, Figure S4B). Consistent with a recent report demonstrating that Utx knockout does not affect mouse ESC pluripotency14, these studies indicate that depletion of either KDM6A or KDM6B does not affect human ESC maintenance. We then asked whether KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown affect signaling pathways important for endoderm differentiation.

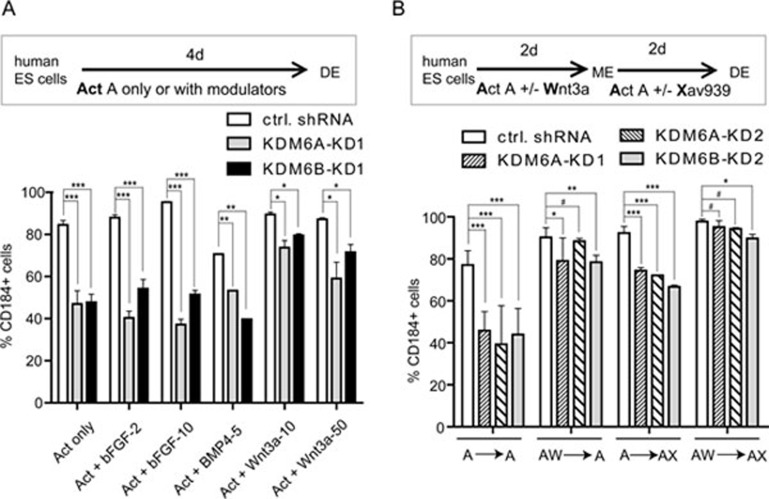

WNT, BMP and FGF signaling pathways play important roles in modulating definitive endoderm differentiation6. To determine which of these signaling pathways is relevant to the endoderm differentiation defect caused by KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown, we asked whether the differentiation defect could be overcome by treatment with agonists of these pathways. We found that WNT agonists, but not BMP or FGF agonists, partially rescued the endoderm differentiation defect phenotype (Figure 2A), indicating that the WNT pathway might be relevant. Consistent with this notion, analysis of previous ChIP-seq results16,17 of H3K27me3-enriched genes in human ESCs revealed that the WNT signaling pathway is highly enriched for H3K27me3 (Supplementary information, Figure S5, P = 0.00007), making genes of the WNT pathway likely relevant targets for KDM6A or KDM6B regulation. Consequently, we focused our attention on the WNT pathway.

Figure 2.

KDM6A/KDM6B contributes to definitive endoderm differentiation through modulating WNT signaling pathway. (A) KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown-caused endoderm differentiation defects can be partially rescued by the addition of the growth factor Wnt3a (10 and 50 ng/ml), but not bFGF (2 and 10 ng/ml) or BMP4 (5 ng/ml) to the activin A-induced differentiation procedure. The statistical values are * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. (B) KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown-caused endoderm differentiation defects can be rescued by addition of the WNT agonist Wnt3a (50 ng/ml) at the first 2-day differentiation or addition of WNT antagonist Xav939 (1 μM) at the late 2-day differentiation individually or in combination in the activin A-based endoderm differentiation. Percentage of CD184-positive cells is measured after 4-day differentiation and presented in the various treatments. The statistical values are # P> 0.05; * P< 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001.

KDM6A/KDM6B contributes to definitive endoderm differentiation through modulating WNT pathway

In human ESCs, activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes loss of self-renewal and drives mesoderm lineage differentiation22. Moreover, Wnt3a was utilized in the first days to promote mesendoderm differentiation but was removed in the later stage23. These studies suggest that WNT signaling is required for mesendoderm differentiation but continuous activation of this pathway would lead to mesoderm differentiation. Consistent with this, we found that inhibition of WNT signaling could also facilitate definitive endoderm differentiation from human ESC-derived mesendoderm (see data below). Given the role of WNT signaling in mesendoderm and further definitive endoderm differentiation, we asked whether manipulation of WNT signaling at different differentiation stages could rescue the endoderm differentiation defect caused by KDM6A/KDM6B knockdown. FACS sorting and quantification of the CD184-positive cell population after activin A-induced endoderm differentiation under various WNT agonist (Wnt3a) or antagonist (Xav939) treatments revealed that the differentiation defects caused by KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown can be rescued either by the use of the WNT agonist at the early differentiation stage (Figure 2B, compare A-A with AW-A treatment) or partially rescued by the use of WNT antagonist at the late differentiation stage (Figure 2B, compare A-A with A-AX treatment). Under the condition of sequential treatment with WNT agonist followed by antagonist, the differentiation defects are completely rescued (Figure 2B, compare A-A with AW-AX treatment). These results indicate that the function of KDM6A and KDM6B in endoderm differentiation is largely mediated through the WNT signaling pathway.

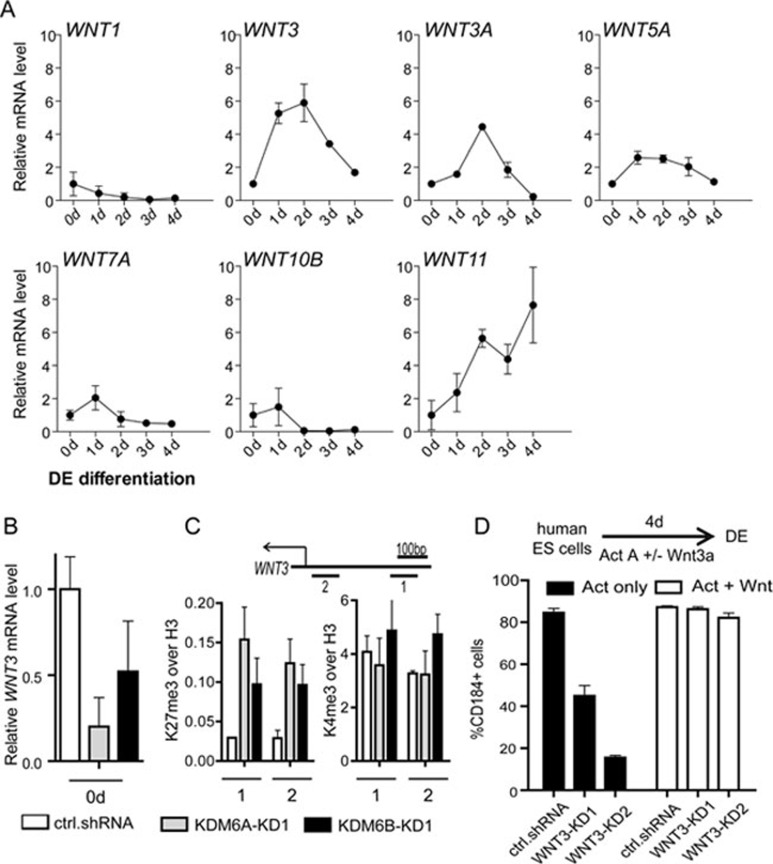

WNT3 is a KDM6A/KDM6B target contributing to the early stage of endoderm differentiation

Results presented in Figure 2B demonstrate that depletion of KDM6A or KDM6B impairs WNT signaling at an early stage of differentiation but enhances WNT signaling at a late differentiation stage, suggesting that different KDM6A/KDM6B target genes may mediate the early and late differentiation effects, respectively. Because KDM6A and KDM6B remove the H3K27me3 repressive mark, they likely function in gene activation. Considering the fact that WNT agonist in the early differentiation stage and WNT antagonist in the late differentiation stage can partially rescue impaired definitive endoderm differentiation phenotype, it is likely that KDM6A/KDM6B upregulate WNT activator at the early stage and WNT repressor at the late stage of endoderm differentiation.

To identify target genes of KDM6A/KDM6B in the early stage, we analyzed the expression of 14 WNT ligand genes that are enriched for H3K27me3 in human ESCs (Supplementary information, Figure S5). Among these genes, only seven are detectable. Of which, WNT3 exhibits the highest upregulation at 1 day of differentiation (Figure 3A). Consistent with the notion that WNT3 is an important KDM6A/KDM6B target, knockdown of KDM6A or KDM6B downregulates WNT3 expression (Figure 3B). In addition, ChIP analysis indicates that the H3K27me3 level of WNT3 gene promoter is increased upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown, while the H3K4me3 level is not significantly altered, consistent with the H3K27me3 demethylase activity of KDM6A/KDM6B (Figure 3C). Importantly, when WNT3 knockdown ESCs (Supplementary information, Figure S6, left panel) are subjected to endoderm differentiation, they exhibit endoderm differentiation defect similar to KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown ESCs (Figure 3D). This differentiation defect can be rescued by treatment with the WNT agonist, supporting a role for WNT3 in endoderm differentiation (Figure 3D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that WNT3 is an important KDM6A/KDM6B target that mediates the function of KDM6A/KDM6B at early stage of endoderm differentiation.

Figure 3.

WNT3 is a KDM6A/KDM6B target contributing to early endoderm differentiation. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of 7 H3K27me3-enriched WNT ligand genes during definitive endoderm differentiation. WNT2, WNT2B, WNT5B, WNT6, WNT9B, WNT10A and WNT16 are not detectable. Expression levels are related to day 0. Data presented is the average of three independent experiments with error bars. (B) RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates downregulation of WNT3 expression upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown. (C) ChIP analysis demonstrates increased H3K27me3 level, but not H3K4me3, at the WNT3 gene promoter upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown. The analysis was performed at the beginning of differentiation. (D) Activin A-induced endoderm differentiation is compromised by WNT3 knockdown, which can be rescued by the addition of the WNT agonist Wnt3a. The differentiation efficiency is measured by quantification of CD184-positive cell population after 4-day activin A-based endoderm differentiation.

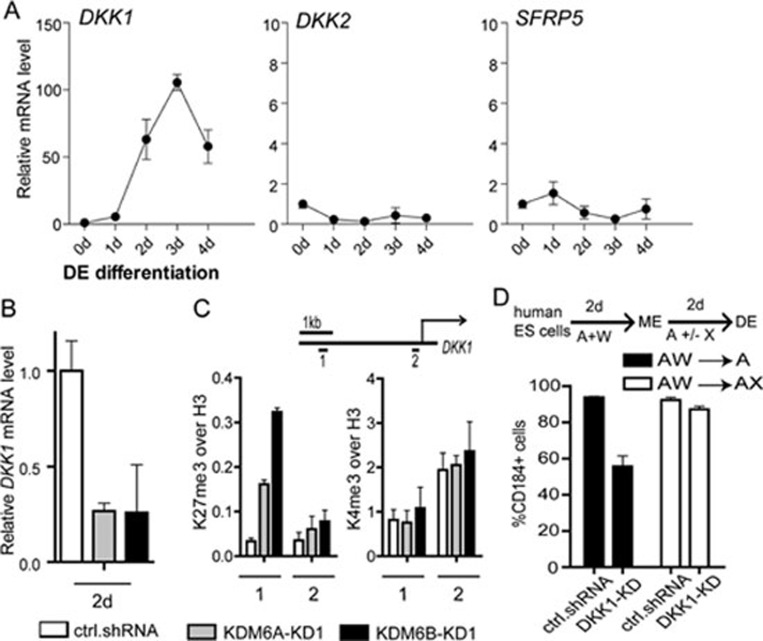

DKK1 is a KDM6A/KDM6B target contributing to later stage endoderm differentiation

Using a similar strategy, we analyzed the expression pattern of 4 WNT antagonist genes with enrichment of H3K27me3 in human ESCs (Supplementary information, Figure S5). We found that only DKK1 exhibited a dramatic upregulation at the late differentiation stage (Figure 4A). Consistent with the notion that DKK1 is an important KDM6A/KDM6B target, knockdown of KDM6A or KDM6B results in DKK1 downregulation (Figure 4B). In addition, ChIP analysis indicates that the H3K27me3 level at DKK1 gene enhancer (amplicon #1), but not its transcription start site (amplicon #2), is increased upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown, while the H3K4me3 level is not significantly altered (Figure 4C), consistent with the H3K27me3 demethylase activity of KDM6A/KDM6B. Importantly, when DKK1 knockdown ESCs (Supplementary information, Figure S6, right panel) are subjected to endoderm differentiation, they exhibit endoderm differentiation defect similar to KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown ESCs (Figure 4D). This differentiation defect can be rescued by treatment with exogenous WNT antagonist Xav939 at late stage of differentiation (Figure 4D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that DKK1 is an important KDM6A/KDM6B target that mediates the function of KDM6A/KDM6B at late stage of endoderm differentiation.

Figure 4.

DKK1 is a KDM6A/KDM6B target contributing to late endoderm differentiation. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of H3K27me3-enriched WNT antagonist genes during definitive endoderm differentiation. SFRP4 is not detectable. Expression levels are related to day 0. Data presented is the average of three independent experiments with error bars. (B) RT-qPCR analysis demonstrates downregulation of DKK1 expression upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown. (C) ChIP analysis demonstrates increased H3K27me3 level, but not H3K4me3, at the DKK1 gene enhancer upon KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown. The analysis was performed at the beginning of the second stage of differentiation. (D) Activin A-induced endoderm differentiation is compromised by DKK1 knockdown, which can be rescued by addition of WNT antagonist Xav939 at late stage of differentiation. The differentiation process includes 2-day treatment of activin A and Wnt3a followed by another 2-day treatment with or without Xav939. The differentiation efficiency is measured by quantification of CD184-positive cell population after 4-day differentiation.

In this study, we demonstrate that the H3K27me3 demethylases KDM6A and KDM6B contribute to definitive endoderm differentiation from human ESCs. The fact that sequential treatment with WNT agonist and antagonist can rescue the endoderm differentiation defect caused by KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown suggests that KDM6A and KDM6B participate in endoderm differentiation through regulating WNT signaling pathway. Further analysis revealed that KDM6A and KDM6B play an important role in the activation of WNT3 and DKK1 at early and late stage of endoderm differentiation, respectively. Consistent with the notion that KDM6A and KDM6B play an important role in modulating the WNT signaling pathway, knockdown of KDM6A/KDM6B also disrupted the expression of other WNT target genes in responding to endoderm differentiation (Supplementary information, Figure S7). These results allow us to propose a working model explaining how KDM6A/KDM6B may contribute to the endoderm differentiation process (Figure 5). It appears that the low KDM6A/KDM6B levels in human ESCs help maintain the expression of WNT3 at a basal level by keeping the repressive mark H3K27me3 at a low level. When treated with endoderm inducer such as activin A, KDM6A and KDM6B are upregulated, which causes removal of the H3K27me3 repressive mark leading to upregulation of WNT3 gene expression. Upregulation of WNT3 causes activation of the WNT pathway, which promotes mesendoderm differentiation in the presence of activin A. At the late stage of definitive endoderm differentiation, WNT antagonist genes such as DKK1 is also activated by KDM6A/KDM6B in a similar fashion to suppress WNT signaling pathway for mesendoderm to definitive endoderm differentiation (Figure 5). Depletion of KDM6A/KDM6B impairs activation of WNT3 and DKK1 leading to impaired definitive endoderm differentiation. Future studies should reveal how KDM6A/KDM6B achieves precise temporal control of WNT3 and DKK1 regulation.

Figure 5.

Hypothetic model explaining how KDM6 may contribute to definitive endoderm differentiation. Treatment of hESCs with activin A causes activation of KDM6A and KDM6B, which can target and remove the H3K27me3 repressive mark leading to upregulation of WNT3. Increased WNT3 causes activation of the WNT pathway and promotes mesendoderm differentiation. At the late stage of endoderm differentiation, WNT antagonist gene DKK1 is activated by KDM6A and KDM6B in a similar fashion to suppress WNT signaling pathway for mesendoderm to definitive endoderm differentiation. ME, mesendoderm; DE, definitive endoderm.

Definitive endoderm commitment is mainly controlled by the TGF-β superfamily member, Nodal/activin A, which activates SMAD2/3 and SMAD4 transcriptional complexes to drive target gene expression3. It has been reported recently that activin A treatment results in the recruitment of KDM6B concomitant with H3K27me3 reduction at SMAD2/3 target loci during endoderm differentiation24. Here we extended this study by uncovering WNT genes as targets of KDM6A and KDM6B that contribute to the regulation of definitive endoderm differentiation. The fact that knockdown of two of the KDM6A/KDM6B targets WNT3 and DKK1 impairs endoderm differentiation even when activin A signaling is still active suggests that KDM6A/KDM6B-mediated activation of WNT signaling is important for endoderm differentiation. Our study not only uncovered a novel function for KDM6A/KDM6B in endoderm differentiation, but also revealed how they contribute to the differentiation process.

Materials and Methods

Generation of knockdown human ESC lines

Human ESC lines HUES8 (passage 40-60) was cultured in Matrigel-coated dishes with mTeSR1 medium according to the manual (STEMCELL Technologies). The lentiviral vector system is obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program. The murine U6-shRNA cassette is inserted into the pTY transducing vector. The 19-nt siRNA targeting sites against human KDM6A or KDM6B are as follows: KDM6A-KD1, GGAAATTCATTTACGACTT; KDM6A-KD2, GGAGTTCTGTAATTTCAAA; KDM6B-KD1, GCATCTATCTGGAGAGCAA; KDM6B-KD2, GATTCTTTCTATGGGCTTT; KDM6B-KD3, GCTCTGGAACTTTCATACT; control-KD, GGAACTTATTTAGCAACTT. WNT3 and DKK1 knockdown vectors were purchased from Open Biosystems and verified (clone ID: TRCN0000033381 and TRCN0000033382 for WNT3; TRCN0000033385 for DKK1). After lentiviral transfection, stable knockdown cells were selected by using 2 μg/ml puromycin based on the construct containing puromycin-resistant cassette.

Definitive endoderm differentiation

For definitive endoderm differentiation, human ESCs cultured on Matrigel were washed twice by DMEM/F12 and then cultured in basal medium (DMEM/F12, 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1% (vol/vol) nonessential amino acids, 0.5% (vol/vol) B27 without vitamin A (Invitrogen), 0.25% (vol/vol) N2 (Invitrogen)) supplemented with 100 ng/ml activin A (PeproTech) and/or other growth factors and chemicals as noted. The growth factors and chemicals used in this study included murine Wnt3a (PeproTech, 10-50 ng/ml), bFGF (PeproTech, 2-10 ng/ml), BMP4 (R&D, 1-10 ng/ml) and XAV939 (Tocris, 0.5-1 μM).

Flow cytometry

Cells were dissociated to a single-cell suspension using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA or Accutase (StemCell Technologies). For labeling of cell surface antigens, cells were incubated with primary antibody (APC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD184 IgG, BD; PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD117 IgG, BD) or control isotype in ice-cold FACS buffer (2% (vol/vol) FBS in PBS) for 30-45 min and followed by washing twice. Then cell labeling was analyzed using the flow cytometer FACSAria II with FACSDiva software version 6.0 (BD Biosciences) and positive or negative cells were sorted for further experiments.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures using Qiashredder and RNeasy mini kits (Qiagen) and treated with RNase-free DNase I set according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (about 1-2 μg per 20 μl reaction) was reverse transcribed using SuperScript™ II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) primed with random hexamer oligonucleotides (Promega). Quantitative PCR was carried out on CFX384 Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad) using Sso-Fast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH and calculated using the 2−ΔCt method. All primers were purchased from Invitrogen and listed in Supplementary information, Table S1.

ChIP-qPCR

For ChIP analysis, undifferentiated human ESCs or differentiated cells from knockdown or control were used for H3K27me3 or H3K4me3 or H3 ChIP using Imprint® Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The antibodies used are all polyclonal rabbit IgG and included anti-H3K27me3 (Millipore), anti-H3K4me3 (Millipore) and anti-H3 (Abcam). Quantitative PCR was carried out as above. The primers were designed according to the published H3K27me3 ChIP-seq data16,17 and listed in Supplementary information, Table S2.

More detailed methods are shown in Supplementary information, Data S1.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues in our lab: Dr Jin He for help in lentiviral transfection and providing the mouse Kdm6b cDNA and mutant constructs; Dr Shinpei Yamaguchi for making Figure 5; Drs Jin He and Gaoyang Liang for critical reading of the manuscript. This work is supported by U01DK089565 from NIH. YZ is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

Definitive endoderm is successfully induced in human ESC line HUES8.

RT-qPCR quantification of knockdown efficiency of the stable KDM6A (left) and KDM6B (right) knockdown HUES8 cell lines.

KDM6A/KDM6B knockdown cells exhibit impaired endoderm differentiation during the entire differentiation process.

KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown does not affect ESC maintenance

DAVID-KEGG (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov">) signaling pathway analysis with the overlapped H3K27me3-marked genes in human ESCs from two independent reports (Pan et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2007).

RT-qPCR quantification of knockdown efficiency of the stable WNT3 (left) and DKK1 (right) knockdown HUES8 cell lines.

KDM6A/KDM6B knockdown alters WNT target gene expression under definitive endoderm differentiation conditions.

Primers for quantitative expression analysis of RT-PCR.

Genomic primers for ChIP-qPCR.

Methods

References

- Murry CE, Keller G. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell. 2008;132:661–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn AM, Wells JM. Vertebrate endoderm development and organ formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:221–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF. Nodal morphogens. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a 003459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour KA, Agulnick AD, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Kroon E, Baetge EE. Efficient differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to definitive endoderm. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A, Shinozaki K, Shannon JM, et al. Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development. 2004;131:1651–1662. doi: 10.1242/dev.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mfopou JK, Chen B, Sui L, Sermon K, Bouwens L. Recent advances and prospects in the differentiation of pancreatic cells from human embryonic stem cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:2094–2101. doi: 10.2337/db10-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osafune K, Caron L, Borowiak M, et al. Marked differences in differentiation propensity among human embryonic stem cell lines. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:313–315. doi: 10.1038/nbt1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R, Zhang Y. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agger K, Cloos PA, Christensen J, et al. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449:731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, Natoli G. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130:1083–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F, Bayliss PE, Rinn JL, et al. A histone H3 lysine 27 demethylase regulates animal posterior development. Nature. 2007;449:689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature06192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Villa R, Trojer P, et al. Demethylation of H3K27 regulates polycomb recruitment and H2A ubiquitination. Science. 2007;318:447–450. doi: 10.1126/science.1149042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee JW, Lee SK. UTX, a histone H3-lysine 27 demethylase, acts as a critical switch to activate the cardiac developmental program. Dev Cell. 2012;22:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Takeuchi O, Vandenbon A, et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:936–944. doi: 10.1038/ni.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Tian S, Nie J, et al. Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 4 and lysine 27 methylation in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XD, Han X, Chew JL, et al. Whole-genome mapping of histone H3 Lys4 and 27 trimethylations reveals distinct genomic compartments in human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:286–298. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Jiang W, Liu M, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of human ES cells and iPS cells into mature pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Cell Res. 2009;19:429–438. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nostro MC, Sarangi F, Ogawa S, et al. Stage-specific signaling through TGFbeta family members and WNT regulates patterning and pancreatic specification of human pluripotent stem cells. Development. 2011;138:861–871. doi: 10.1242/dev.055236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Rodriguez RT, Wang J, Ghodasara A, Kim SK. Targeting SOX17 in human embryonic stem cells creates unique strategies for isolating and analyzing developing endoderm. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KC, Adams AM, Goodson JM, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling promotes differentiation, not self-renewal, of human embryonic stem cells and is repressed by Oct4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:4485–4490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118777109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, et al. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Yoon SJ, Chuong E, et al. Chromatin and transcriptional signatures for Nodal signaling during endoderm formation in hESCs. Dev Biol. 2011;357:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Definitive endoderm is successfully induced in human ESC line HUES8.

RT-qPCR quantification of knockdown efficiency of the stable KDM6A (left) and KDM6B (right) knockdown HUES8 cell lines.

KDM6A/KDM6B knockdown cells exhibit impaired endoderm differentiation during the entire differentiation process.

KDM6A or KDM6B knockdown does not affect ESC maintenance

DAVID-KEGG (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov">) signaling pathway analysis with the overlapped H3K27me3-marked genes in human ESCs from two independent reports (Pan et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2007).

RT-qPCR quantification of knockdown efficiency of the stable WNT3 (left) and DKK1 (right) knockdown HUES8 cell lines.

KDM6A/KDM6B knockdown alters WNT target gene expression under definitive endoderm differentiation conditions.

Primers for quantitative expression analysis of RT-PCR.

Genomic primers for ChIP-qPCR.

Methods