Abstract

The first report of Z-selective macrocyclizations using a ruthenium-based metathesis catalyst is described. Selectivity for Z-macrocycles is consistently high for a diverse set of substrates with a variety of functional groups and ring sizes. The same catalyst was also employed for the Z-selective ethenolysis of a mixture of E and Z macrocycles, providing the pure E-isomer. Notably, only an atmospheric pressure of ethylene was required. These methodologies were successfully applied to the construction of several olfactory macrocycles, as well as the formal total synthesis of the cytotoxic alkaloid motuporamine C.

The macrocyclic motif is widely prevalent in an abundance of natural products and pharmaceuticals, and also provides the backbone for a unique class of olfactory compounds, termed macrocyclic musks. Originally derived from natural sources, macrocyclic musks have been rapidly gaining popularity in the perfume industry as alternatives to synthetic nitroarene and polycyclic musks, which exhibit bioaccumulation and toxicity hazards.1,2 In general, many biologically and industrially relevant macrocyclic compounds feature an internal olefin. The alkene geometry is instrumental in the resulting biological activity or olfactory properties of the compound of interest, which can be adversely affected by even minute amounts of stereoisomeric impurities. In addition, stereochemically pure macrocyclic olefins are often utilized as platforms to stereospecifically install other functional groups. Although in some cases it might be possible to separate a mixture of E- and Z-isomers chromatographically or by crystallization, these methods are by no means general and often require extensive optimization for each individual compound. Furthermore, with respect to macrocyclic musks in particular, certain perfumes often contain a specific mixture of E- and Zolfactory macrocycles.2 Hence, selective methods for the preparation of both E- and Z-olefin containing macrocycles are of paramount importance.

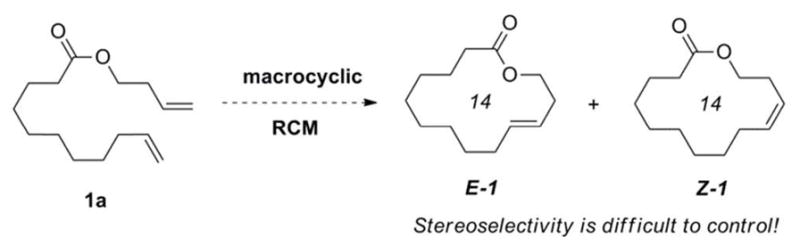

Ring-closing metathesis (RCM) has become a ubiquitous tool for the synthesis of carbo- and heterocylic ring systems, and is particularly well-suited for the efficient synthesis of macrocycles.3 Unfortunately, most metathesis catalysts exhibit minimal kinetic selectivity, and thus for medium- to large-sized ring systems in which both E- and Z-isomers are accessible, the product distribution at high conversion reflects the thermodynamic energetic difference between the two. For ruthenium-based metathesis catalysts bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands, the E-isomer is often favored, as in the macrocyclic RCM of diene 1a, which produces 14-membered lactones E-1 and Z-1 in a ca. 12:1 ratio (Scheme 1).4 However, it can be difficult to predict the thermodynamic product a priori, and the reaction will frequently proceed with minimal or inverse selectivity to that which was anticipated.5 This issue has been circumvented indirectly through the implementation of ring-closing alkyne metathesis (RCAM), followed by Lindlar- or Birch-type reductions to generate stereopure Z- or E-macrocycles respectively.3,6 Fürstner and co-workers have also developed a complementary method for the synthesis of E-macrocycles from cycloalkynes, employing a hydrosilylation/desilylation sequence.7 More recently, a report has appeared detailing the use of vinylsiloxanes to promote stereoselective ring-closing metathesis, generating E-alkenylsiloxanes, which upon desilylation yield Z-macrocycles. 8

Scheme 1.

Macrocyclic RCM of diene 1a to E-1 and Z-1.

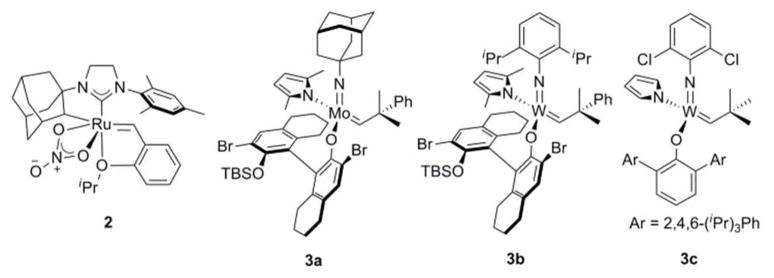

Accordingly, a considerable effort has been expended in the search for metathesis catalysts exhibiting kinetic selectivity. This has resulted in numerous current reports detailing the successful realization of Z-selective homo-coupling, cross-metathesis, and ring-opening/cross-metathesis reactions employing tungsten and molybdenum-based catalyst systems.9 In addition, a single report has emerged detailing the Z-selective ethenolysis of straight-chain olefins, resulting in pure E-olefins from an E/Z mixture with a molybdenum catalyst.10 Recently, in an elegant publication, the Schrock and Hoveyda groups disclosed the first example of catalyst systems capable of performing a highly Z-selective macrocyclic RCM reaction, utilizing the monoaryloxide-pyrrolide (MAP) catalysts 3a and 3b (Figure 1), to generate a 16-membered lactone.12 They further showcased the utility of these types of complexes in the synthesis of the 16-membered core of epothilone C (85% yield, 96% Z), and the 15-membered core of nakadomarin A (90% yield, 97% Z), using tungsten catalyst 3c.

Figure 1.

Prominent Z-selective metathesis catalysts.

Recently, we have developed a family of chelated ruthenium-based catalysts that promote highly Z-selective homo-coupling, cross-metathesis, and ring-opening metathesis polymerization reactions.13 Herein, we disclose the first report of Z-selective macrocyclic RCM using a ruthenium-based catalyst system (2), applicable to a broad range of ring sizes and functional groups. Additionally, we report the first instance of Z-selective ethenolysis of macrocycles, resulting in pure E-macrocycles from an E/Z-mixture, using the same catalyst system (2). We have successfully applied these strategies to the stereoselective synthesis of a selection of olfactory macrocycles, and the formal total synthesis of the cytotoxic alkaloid motuporamine C.

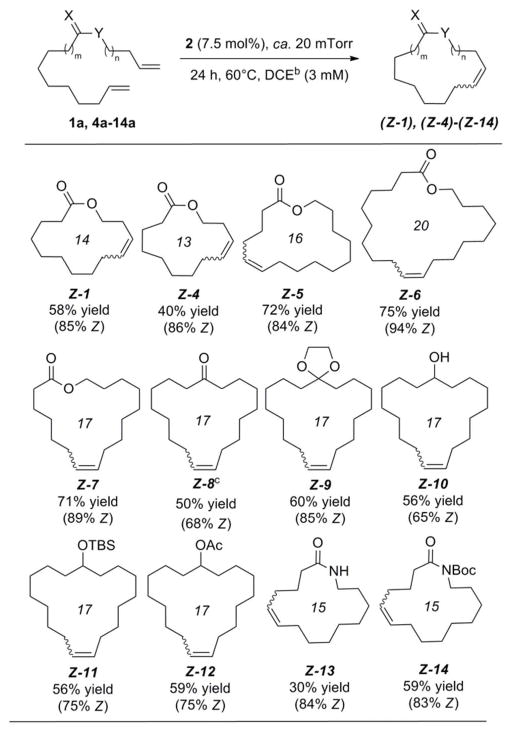

We initiated our studies by optimizing reaction conditions for the macrocyclic RCM of diene 1a, producing lactone Z-1 in 58% yield and 85% Z (Table 1). Although all reagents were initially combined in a glovebox, using rigorously degassed anhydrous dichloroethane, the reaction could also be conveniently set-up on the benchtop, with commercial anhydrous dichloroethane used directly as received, generating Z-1 in 49% yield and 86% Z. The main competing process in the macrocyclic RCM to Z-1 was oligomerization of diene 1a,14 and the amount of Z-1 produced is dependent upon the ratio of these respective rate constants (kRCM/koligomer), as well as the rate of catalyst decomposition.15 Macrocyclic ring closure in general is entropically disfavored. In the case of macrocyclic RCM reactions mediated by 2, the transformation might also suffer from a significant negative enthalpic contribution as a result of steric interactions with the NHC moiety in transition states leading to productive turnovers.16 Thus, in order to favor ring closure with respect to oligomerization, dilute conditions (3 mM) and elevated temperatures (60 °C) were required. The application of a static vacuum (20 mtorr) was also necessary, as refluxing conditions under either an inert atmosphere or while sparging with argon resulted in an increased formation of oligomerization products.14 An increase in temperature (80 °C) decreased the yield of Z-1, likely as a result of catalyst decomposition, and a further increase in dilution (1 mM) resulted in prohibitively slow reaction times. An increase in the catalyst loading (10 mol%) or reaction time (48 h) did not increase conversion to Z-1.17

Table 1.

Z-Selective macrocyclizations employing ruthenium catalyst 2.a

|

Yields are of isolated product (E/Z ratios determined by 1H- or 13C-NMR).11

DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane.

Reaction was quenched after 8 hours.

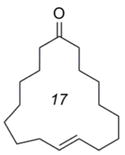

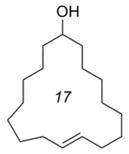

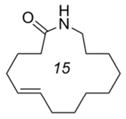

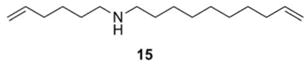

A variety of substrates readily underwent macrocyclic RCM with ruthenium catalyst 2, utilizing the single set of standard reaction conditions optimized for lactone Z-1 (Table 1).18 In almost all cases, consumption of the diene precursor was high, resulting in ca. 80% conversion to macrocyclic products; unprotected amide 13a was the sole exception, which reached only ca. 50% conversion to Z-13. Protection of 12a as its tert-butylcarbamate derivative 13a restored activity, and resulted in higher yields of Z-14.19 The larger, 16-, 17-, and 20-membered ring lactones (Z-5, Z-7, and Z-6) gave the highest yields (72%, 71%, and 75% respectively),20 whereas the reaction was less efficient for the smaller 13-membered ring lactone Z-4 (40% yield). In general, the Z-selectivity was high for all macrocyclizations (75–94% Z), although it was necessary to mask ketone (Z-8) and alcohol (Z-10) functionality in order to maintain high Z-selectivity.21 The origin of the considerable bias exhibited by 2 for the production of Z-olefins has been attributed to a strong preference for the formation of side-bound metallocyclobutanes in these systems, in which transition states leading to E-olefins are strongly disfavored, as a result of unfavorable steric interactions with the mesityl ring of the N-heterocyclic carbene ligand.16

It is noteworthy that macrolides Z-4, Z-7, and Z-8 are currently in demand by the perfume industry (marketed as yuzu lactone, ambrettolide and civetone respectfully).2 Fürstner and co-workers had previously accessed these compounds by RCAM/Lindlar hydrogenation,22 as ring-closing metathesis strategies had failed to proceed with adequate Z-selectivities for these types of ring systems.23 Macrocyclic lactam Z-13 is also an intermediate en route to Goldring and Weiler’s total synthesis of the cytotoxic alkaloid motuporamine C.24.25 In this case, Z-13 had been obtained following RCM and purification from a mixture with its E-isomer (only 44% Z), using radial chromatography. Fürstner and co-workers had also previously employed a RCAM/Lindlar hydrogenation sequence to access motuporamine C stereospecifically.26

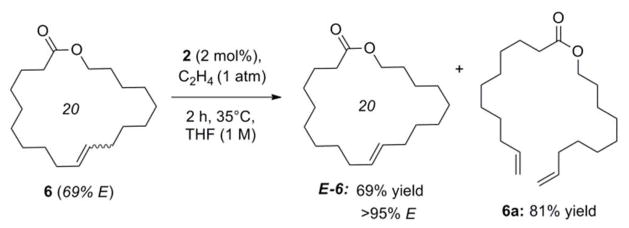

In a complementary approach to the synthesis of the Z-macrocycles shown above in Table 1, we were also able to further exploit catalyst 2 for the isolation of pure E-macrocy cles, through the selective degradation of the Z-isomer in the corresponding E-dominant mixtures (Scheme 2).27 Ring-opening via ethenolysis is simply the reverse of the macrocyclic RCM reaction. Thus, as high Z-selectivity was evidenced in the forward reaction (cf. Table 1), it was expected that the reverse reaction would also display high selectivity for Z-olefins. 28 Indeed, exposure of an E/Z mixture of lactone 6 (69% E) to ethylene (1 atm) in the presence of catalyst 2 (2 mol%) led to the complete degradation of Z-6 after only 2 hours at 35 °C (Scheme 2). Notably only an atmospheric pressure of ethylene was necessary.30 It is also significant to mention that the corresponding ring-opened diene was also recovered, and thus could subsequently be recyclized in subsequent macrocyclic RCM reactions if desired.

Scheme 2.

Z-Selective ethenolysis of E/Z-6.29

We were able to apply similar reaction conditions to macrocycles containing ketone (8), alcohol (10), and amide (13) functionality (Table 2). In general, complete consumption of the Z-macrocycle occurs within two hours, affording the pure E-macrocycle in good yield. The lower yield of ketone-containing product E-8 is likely a result of the elevated temperature required to form the E-isomer exclusively, which might also be expected to accelerate undesired degradation of the E-macrocycle. Additionally, an increase in oligomerization was also observed in this case, thus reducing the yield of the recovered diene 8a.

Table 2.

Z-Selective ethenolysis of a mixture of E-dominant macrocycles.

| Compound |

E-8b |

E-10c |

E-13d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial E (%) | 80 | 80 | 55 |

| Final E (%)e | >95 | >95 | >95 |

| Yield (%)f | E-8: 40g | E-10: 78g | E-13: 75g |

| 8a: 46h | 10a: 79h | 13a: 86h |

Reaction conditions: 2 (2 mol%), C2H4(1 atm), 2 h, THF (1 M).

Reaction was run at 75°C.

Reaction was run at 35°C,

Reaction was run at 40°C.

Product was entirely E based on 1H- or 13C-NMR.

Isolated product.

Calculated based on initial amount of E-isomer.

Calculated based on initial amount of Z-isomer.

In summary, we have demonstrated the first example of a ruthenium metathesis catalyst that is capable of promoting Z-selective macrocyclic RCM. This represents the first systematic study of the scope of Z-selective macrocyclic RCM with respect to a broad range of ring sizes. The transformation is amenable to a variety of functional groups, and proved applicable in the synthesis of a number of olfactory macrocycles as well as the formal total synthesis of motuporamine C. In addition, it has been shown that the same catalyst system can promote Z-selective ethenolysis of macrocyclic compounds that are present in an E/Z mixture, providing pure E-macrocycles. It is anticipated that both methods will realize extensive use in the synthesis of natural products and pharmaceuticals, as well as in the perfume industry. The ability to utilize an atmospheric pressure of ethylene for Z-selective ethenolysis should enable the widespread use of this application in particular, for both bench-top and industrial scales, as an effective method for the isolation of pure E-macrocycles without advanced chromatography or alternative purification techniques. Therefore, as improved Z-selective catalysts based on ruthenium are discovered, the utility of these complementary methodologies will only increase. As in the past, organic chemists will find these ruthenium-based systems to have broad applicability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. David VanderVelde is thanked for assistance with NMR experimentation and analysis. This work was financially supported by NIH (R01-GM031332), the NSF (CHE-1212767), and the NSERC of Canada (fellowship to V.M.M.). Instrumentation on which this work was carried out was supported by the NIH (NMR spectrometer, RR027690). Materia, Inc. is thanked for its donation of metathesis catalyst 2.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental details and characterization data for all compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rimkus GG. The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. 3X Springer Verlag; Berlin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Rowe DJ. Chemistry and Technology of Flavors and Fragrances. Blackwell; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]; b) Ohloff G, Pickenhagen W, Kraft P. Scent and Chemistry - The Molecular World of Odors. Verlag Helvectica Acta; Zurich: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Grubbs RH. Handbook of Metathesis. Vol. 2 Wiley-VCH; Weinhem: 2003. [Google Scholar]; b) Gradillas A, Pérez-Castells J. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:6086–6101. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Majumdar KC, Rahaman H, Roy B. Curr Org Chem. 2007;11:1339–1365. [Google Scholar]; d) Diederich F, Stang PJ, Tykwinski RR. Modern Supramolecular Chemistry: Strategies for Macrocycle Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinhem: 2008. [Google Scholar]; e) Cossy J, Arseniyadis S, Meyer C. Metathesis in Natural Product Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinhem: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee C–W, Grubbs RH. Org Lett. 2000;2:2145–2147. doi: 10.1021/ol006059s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivkin A, Cho YS, Gabarda AE, Yoshimura F, Danishefsky SJ. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:139–143. doi: 10.1021/np030540k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Fürstner A, Davies PW. Chem Commun. 2005:2307–2320. doi: 10.1039/b419143a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang W, Moore JS. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:93–120. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Fürstner A, Radkowski K. Chem Commun. 2002:2182–2183. doi: 10.1039/b207169j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lacomber F, Radkowski K, Seidel G, Fürstner A. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7315–7324. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Jimenez M, Hansen AS, Raiber E-A, Schreiber SL, Young DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9196–9199. doi: 10.1021/ja202012s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Ibrahem I, Yu M, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3844–3845. doi: 10.1021/ja900097n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiang AJ, Zhao Y, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16630–16631. doi: 10.1021/ja908098t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Meek SJ, O’Brien RV, Llaveria J, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2011;471:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature09957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Peryshkov DV, Schrock RR, Takase MK, Muller P, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:20754–20757. doi: 10.1021/ja210349m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Marinescu SC, Schrock RR, Muller P, Takase MK, Hoveyda AH. Organometallics. 2011;30:1780–1782. doi: 10.1021/om200150c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Yu M, Ibrahem I, Hasegawa M, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2788–2799. doi: 10.1021/ja210946z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marinescu SC, Levine DS, Zhao Y, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:11512–11514. doi: 10.1021/ja205002v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.E/Z macrocycles can be readily differentiated through careful analysis of their 1H, 13C, and HSQC spectra, as the carbon atoms α to the olefin moeity in the E-isomers are located significantly more downfield then the corresponding carbon atoms in the Z-isomers, see: Breitmaier E, Voelter W. Carbon-13 NMR Spectroscopy: High-Resolution Methods and Applications in Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry. Verlag Chemie; Weinheim: 1987.

- 12.Yu M, Wang C, Kyle AF, Jakubec P, Dixon DJ, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. Nature. 2011;479:88–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Endo K, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8525–8527. doi: 10.1021/ja202818v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Keitz BK, Endo K, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:9686–9688. doi: 10.1021/ja203488e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Keitz BK, Endo K, Patel PR, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:693–699. doi: 10.1021/ja210225e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Herbert MB, Marx VM, Pederson RL, Grubbs RH. Angew Chem Int Ed. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Determined by inspection of the 1H-NMR spectra of crude reaction mixtures. Additionally, no competing olefin isomerization events were observed.

- 15.For a detailed study of decomposition pathways of catalysts resembling 2see: Herbert MB, Lan Y, Keitz BK, Liu P, Endo K, Day MW, Houk KN, Grubbs RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:7861–7866. doi: 10.1021/ja301108m.

- 16.Liu P, Xu X, Dong X, Keitz BK, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH, Houk KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1464–1467. doi: 10.1021/ja2108728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.When tetrahydrofuran was used in place of dichloro-ethane, a significant increase in oligomerization products was observed, chloroform decomposed 2, and multiple byproducts were formed when toluene or methanol was utilized.

- 18.This is in contrast to the report disclosed by Yu et. al., in which a separate optimization event was required for each individual substrate (see reference 12).

-

19.Macrocyclic RCM was also attempted with amino-diene 15, however <5% conversion resulted. Similar results were obtained with the hydrochloride salt derived from 15.

- 20.This is comparable to the results obtained by Yu et. al for the macrocyclization of 5a, which generated lactone Z-5 in 56% yield (92% Z) using Mo-based catalyst 3a, and 62% yield (91% Z) using W-based catalyst 3b (see reference 12).

- 21.Ketone (8) and alcohol (10) were protected as their corresponding ethyleneglycol (9), and tert-butyldimethylsilyl (11) or acetate (12) derivatives, respectively.

- 22.a) Fürstner A, Guth O, Rumbi A, Seidel G. J Am Chem Soc. 1999:11108–11113. [Google Scholar]; b) Fürstner A, Siedel G. J Organomet Chem. 2000;606:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fürstner A, Langemann K. Synthesis. 1997:792–803. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldring WPD, Weiler L. Org Lett. 1999;1:1471–1473. doi: 10.1021/ol991029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isolation: Williams DE, Lassota P, Andersen RJ. J Org Chem. 1998;63:4838–4841.

- 26.Fürstner A, Rumbo A. J Org Chem. 2000;65:2608–2611. doi: 10.1021/jo991944d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.See supporting information for details regarding the synthesis of the E-dominant macrocycles.

- 28.A more detailed study involving the Z-selective ethenolysis of linear olefins using catalyst 2 is currently underway, and will be reported in due course.

- 29.Yields are isolated, and were calculated based on theoretical amount of pure E-isomer.

- 30.This is in comparison to the molybdenum-based system which requires higher ethylene pressures (4–20 atm) (see reference 10).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.