Abstract

It is well known that upon stress, the level of the tumor suppressor p53 is remarkably elevated. However, despite extensive studies, the underlying mechanism involving important inter-players for stress-induced p53 regulation is still not fully understood. We present evidence that the human lincRNA-RoR (RoR) is a strong negative regulator of p53. Unlike MDM2 that causes p53 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, RoR suppresses p53 translation through direct interaction with the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein I (hnRNP I). Importantly, a 28-base RoR sequence carrying hnRNP I binding motifs is essential and sufficient for p53 repression. We further show that RoR inhibits p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Finally, we demonstrate a RoR-p53 autoregulatory feedback loop where p53 transcriptionally induces RoR expression. Together, these results suggest that the RoR-hnRNP I-p53 axis may constitute an additional surveillance network for the cell to better respond to various stresses.

Keywords: lncRNA, p53, hnRNPI

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 is a master gene regulator controlling diverse cellular processes including DNA repair, cell cycle progression, differentiation, cell growth, senescence and apoptosis1,2. Because of its importance, p53 expression is regulated by a variety of means, such as transcriptional and translational control, alternative splicing, posttranslational modifications and regulation of subcellular localization. Thus, in the unstressed cells, the p53 level remains low; however, upon stress, the p53 level is increased significantly. Although it is believed that such an increase in the p53 level is mainly due to increased stability through posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation3, recent evidence indicates that p53 translational regulation after DNA damage may also play an important role4.

Protein-coding genes account for only about 2% of the human genome, whereas the vast majority of transcripts consist of the non-coding RNAs, among which are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) with a molecular weight of over 200 bases in length5. Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs, like protein-coding genes, are transcribed mainly by RNA polymerase II; they are spliced products via canonical genomic splice site motifs, frequently ended with a poly A tail. Moreover, they are often regulated by well-established transcription factors and are expressed in a tissue-specific manner6. A variety of previously identified RNA species belong to this group, including antisense RNAs, transcribed ultraconserved regions and pseudogenes. For example, antisense RNAs are transcribed from the opposite strand of a protein-coding gene and frequently overlap the corresponding gene7; pseudogenes such as PTENP1 function as a microRNA decoy8. Overexpression of the PTENP1 leads to an increased level of PTEN and causes cellular growth inhibition, an effect dependent on the presence of mature miRNAs9. However, the most important group of lncRNAs are probably long or large intergenic non-coding RNAs (lincRNAs). Despite relatively newly identified, they have been shown to play a critical role in regulation of a variety of cellular functions and disease progressions including stem cell state and cancer metastasis10,11,12,13,14,15,16. This may have to do with their ability to regulate gene expression. In this regard, the proposed functions for lincRNAs include as signals for transcription; as decoys to titrate transcription factors; as guides so that chromatin-modifying enzymes can be recruited to target genes; and as scaffolds to bring together multiple proteins to form ribonucleoprotein complexes17,18.

The human lincRNA-RoR (RoR) is a recently identified lincRNA that is capable of reprogramming differentiated cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)19. While knockdown of RoR decreases, overexpression increases the number of iPSC colonies formed without affecting cell number. The RoR gene is 2.6 kb in length, located in chromosome 18 (hg19 chr18:54,721,802-54,739,350), consisting of four exons. RoR is highly expressed in embryonic stem cells and iPSCs, which is likely due to the regulation of RoR by pluripotency transcription factors such as Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog. Of interest, knockdown of RoR leads to a modest increase in apoptosis and activation of p53 pathways19. However, the underlying mechanisms remain to be determined. In particular, it is unknown whether RoR plays any role in p53 regulation at the translational level.

In this study, we show that RoR functions as a negative regulator of p53 through interaction with an RNA binding protein, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein I (hnRNP I). While RoR has little effect on p53 in the unstressed cells, it significantly suppresses the DNA damage-induced p53 through a translation repression mechanism. As a result, RoR modulates the p53-regulated cellular processes such as cell cycle progression and apoptosis, and the expression of p53 downstream target genes. Furthermore, RoR and p53 form an autoregulatory feedback loop where p53 positively regulates RoR expression by direct interaction with a p53 response element in the putative RoR promoter.

Results

RoR suppresses the DNA damage-induced p53

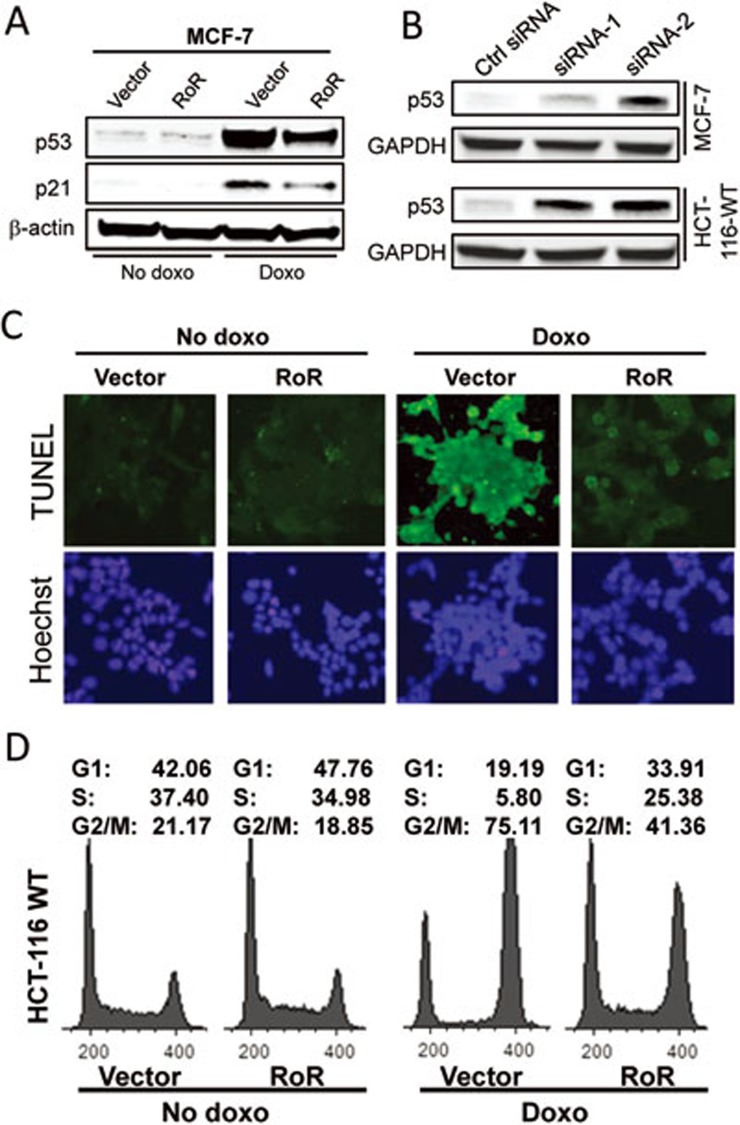

Since a previous study showed that knockdown of p53 can partially rescue the apoptotic phenotype caused by ablation of RoR19, this prompted us to investigate the role of RoR in p53 expression and the p53 regulatory network. Although RoR had little effect on p53 in the unstressed cells, it remarkably suppressed the doxorubicin (doxo)-induced p53 (Figure 1A). A large increase of p53 level was seen in the doxo-treated MCF-7 cells compared to no doxo control cells; however, the same cells transfected with RoR revealed a much lower level of p53 induction than vector control. This was also seen in HCT-116 cells expressing wild-type p53 (HCT-116-WT) but not in p53-null cells (HCT-116-p53 null) (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Consistent with this finding, p53 downstream genes p21 and miR-14520 were also suppressed (Figure 1A; Supplementary information, Figure S1B). Similarly, RoR was able to suppress the ultraviolet C (UVC)-induced p53 (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). In contrast, RoR-siRNAs induced p53 (Figure 1B; Supplementary information, Figure S1D). Given that p53 is a key factor regulating apoptosis and cell cycle progression, we first determined whether RoR affects p53-mediated apoptosis. Consistent with the suppression of p53, RoR reduced the p53-mediated apoptosis, as detected by TUNEL (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) assays (Figure 1C). Similarly, RoR reduced the p53-mediated G2/M arrest (Figure 1D). In the absence of doxo, RoR had little effect on cell cycle profile in HCT-116-WT cells. However, RoR remarkably reduced the doxo-induced G2/M population, from 75.1% down to 41.4% (Figure 1D). On the other hand, such negative effect on G2/M population was not seen in the p53-null cells (Supplementary information, Figure S2).

Figure 1.

RoR suppresses the doxo-induced p53 and the p53-mediated cellular function. (A) Detection of p53 in MCF-7 cells with or without doxo. Cells were transfected with vector or RoR and then treated with doxo at 1 μg/ml for 24 h. Total cellular protein was then extracted for western blot. (B) Suppression of RoR by RNAi induces p53. MCF-7 and HCT-116 WT cells were transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-1 or RoR-siRNA-2. (C) RoR inhibits the doxo-induced apoptosis. The transfected MCF-7 cells were treated with doxo at 2 μg/ml for 24 h before TUNEL assay was performed. A high concentration of doxo was used to detect cell apoptosis. (D) RoR suppresses the doxo-induced G2/M arrest. HCT-116 WT cells were transfected with vector or RoR, and then treated with doxo at 0.1 μg/ml for 24 h, followed by FACS cell cycle analysis. A low concentration of doxo was used to detect cell cycle arrest.

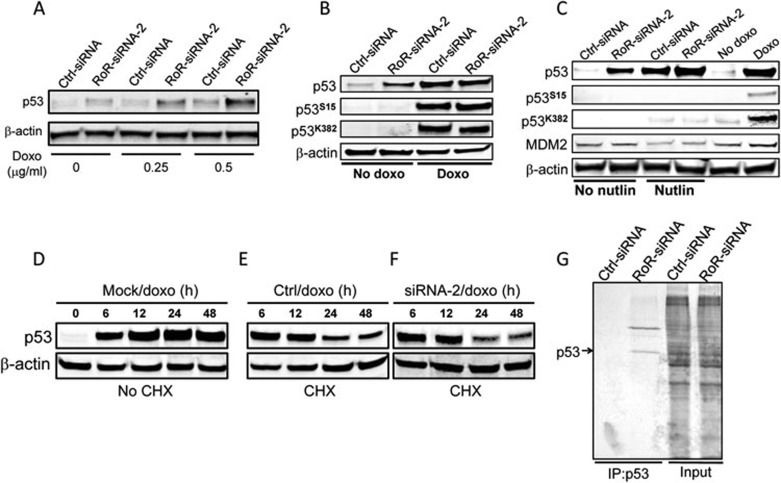

RoR or RoR-siRNA did not change p53 mRNA levels in the presence or absence of doxo (Supplementary information, Figure S3A and S3B), suggesting that a posttranscriptional regulation mechanism was involved. It is known that DNA damage can induce p53 by increasing its stability (e.g., protein phosphorylation) and/or stimulating its translation4. We found that RoR-siRNA alone induced p53 (Figures 2A and 1B) and after treatment with the low concentration of doxo (0.2 μg/ml) for 16 h, RoR-siRNA further induced p53 (Figure 2A), suggesting that the endogenous RoR could regulate the p53 level during DNA damage. Moreover, although RoR-siRNA alone was able to increase the p53 level, it did not cause p53 phosphorylation or acetylation (Figure 2B), both of which are believed to contribute to the p53 stability or activity21,22. Nutlin is a non-genotoxic agent that induces p53 by directly targeting MDM223, a well-characterized negative regulator of p53. As expected, nutlin induced p53, but did not cause phosphorylation or acetylation (Figure 2C). These results suggest that RoR-siRNA-mediated p53 induction may not be due to phosphorylation or acetylation. To further determine the effect of suppression of RoR on the p53 stability, we first transfected cells with RoR-siRNA and then treated them with the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX) for 30 min, followed by doxo treatment. It is evident that CHX reduced the doxo-induced p53 level over the time (Figure 2D vs 2E-2F); however, the p53 protein stability was about the same between control siRNA and RoR-siRNA (Figure 2E and 2F). Finally, pulse-chase experiment with 35S methionine showed a newly synthesized p53 band in the RoR-siRNA transfected cells, whereas no such a protein band was detected in the control siRNA transfected cells (Figure 2G). Therefore, at least translational repression contributes to the RoR-mediated suppression of p53.

Figure 2.

Translational repression of p53 by RoR. (A) Effect of RoR-siRNA on the p53 level with or without doxo. MCF-7 cells were first transfected with control or RoR-siRNA-2 overnight and then treated with doxo at the indicated concentrations for 16 h before harvesting for western blot. (B) RoR-siRNA induces p53 without causing p53 phosphorylation or acetylation. For doxo treatment, MCF-7 cells were transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-2 overnight and then treated with doxo at 0.5 μg/ml for 24 h. (C) Effect of RoR-siRNA combined with nutlin on p53. MCF-7 cells were transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-2 and then treated with nutlin at 0.5 μg/ml for 24 h before the cells were harvested for western blot. (D-F) RoR-siRNA does not change the stability of the doxo-induced p53. MCF-7 cells were transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-2 and then treated with CHX at 20 μg/ml for 30 min, followed by doxo treatment at 0.5 μg/ml. The cells were harvested for western blot at the indicated time points after doxo treatment. (G) RoR-siRNA increases the newly synthesized p53 level as detected by pulse-chase experiments. MCF-7 cells were first transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-2 overnight and newly synthesized protein was labeled with 35S methionine, followed by IP with p53 antibody.

RoR directly interacts with hnRNP I

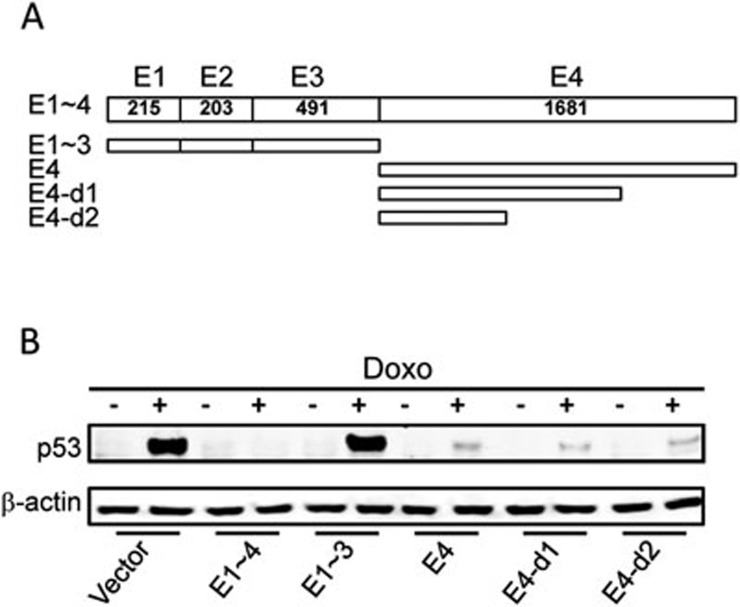

RoR consists of 4 exons with the largest exon 4 of > 1 500 bp (Figure 3A). Of interest, DNA sequence homology search with BLAST program identified about 95% identity to the counterpart of chimpanzee sequence. However, UCSC genome browser found no homolog in mouse, dog and others except Rhesus (Supplementary information, Figure S4), suggesting that RoR is poorly conserved at the primary sequences, even though lncRNAs could be relatively conserved in terms of RNA secondary structures24. Deletion analysis combined with western blot identified an active region within exon 4 (Figure 3B). Further deletion analysis defined a ∼500 bp fragment (E4-d2) capable of suppressing p53. Therefore, E4-d2 was used in the RNA precipitation experiments (Supplementary information, Figure S5) to identify RoR binding partner(s).

Figure 3.

Identification of the suppressive activity of RoR within exon 4 (E4). (A) Schematic description of RoR deletion constructs. RoR consists of 4 exons. A series of deletions were generated using standard PCR approaches to define which region is responsible for p53 repression. E1 stands for exon 1 and so on. (B) Effect of RoR deletions on p53 repression as detected by western blot. MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector alone or full-length RoR (E1∼4) or deletion constructs of RoR and then treated with doxo at 1 μg/ml for 24 h before western blot.

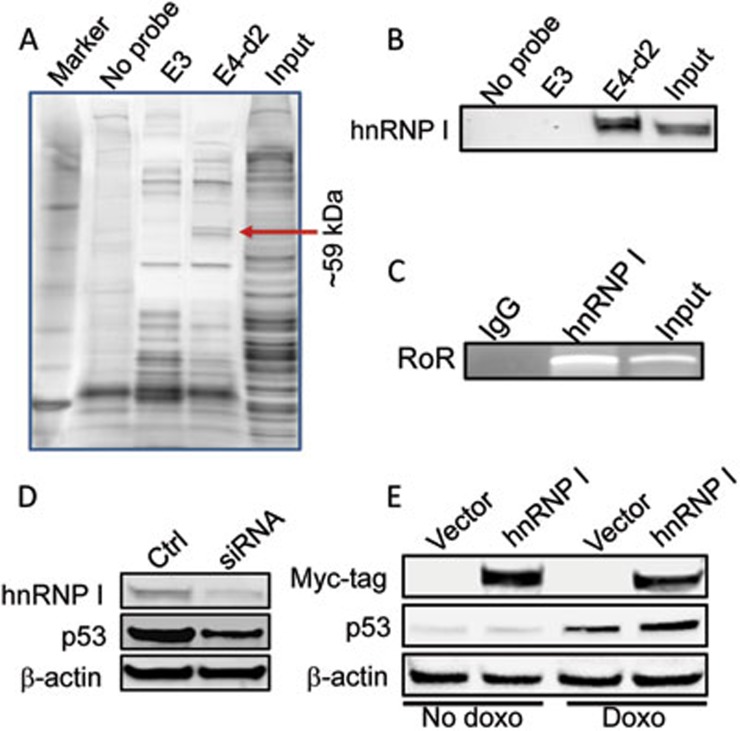

After mixing the biotin-labeled probes with total cellular extract and then separation in SDS-PAGE, silver staining of the gel revealed a doublet band (∼59 kDa) specific to the E4-d2 probe (Figure 4A; Supplementary information, Figure S6A). Mass spectrometry analysis indicated that this doublet band is hnRNP I (also called PTBP1) (Supplementary information, Figure S6B). Western blot confirmed the nature of the protein band (Figure 4B; Supplementary information, Figure S7A). However, we found no evidence of RoR interacting with MDM2 or other well-known negative regulators including MDMX25, COP126, Pirh227 or p53 translation regulators including RPL2628,29 and RNPC130 or p53 itself (Supplementary information, Figure S7B). Furthermore, RoR RNA was pulled down by hnRNP I specific antibody (Figure 4C), further suggesting that RoR interacts with hnRNP I. In addition, hnRNP I also interacted with p53 mRNA, as detected by RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) (Supplementary information, Figure S7C). As a member of the large hnRNP family31, hnRNP I has been implicated in mRNA splicing32. To demonstrate that hnRNP I is important to p53 induction, we knocked down hnRNP I by RNAi and detected a remarkable reduction of the doxo-induced p53 in the siRNA-treated cells compared to control (Figure 4D). In contrast, ectopic expression of hnRNP I increased the p53 level though at a lesser extent (Figure 4E) presumably because sufficient amount of the endogenous hnRNP I is already in the cell.

Figure 4.

hnRNP I is a RoR binding partner. (A) A representative silver-stained gel picture showing a doublet band unique to E4-d2. Mass spectrometry analysis indicated that this band is hnRNP I. (B) Verification of the interaction of RoR with hnRNP I by RNA precipitation and western blot. Samples were prepared in the same way as in (A) and the membrane was probed with hnRNP I antibody. (C) RT-PCR detection of RoR after the hnRNP I immunoprecipitation using primers ROR-Exon4-RT-5.1A and ROR-Exon4-RT-3.1A (Supplementary information, Table S1). (D) Suppression of the doxo-induced p53 by hnRNP I-siRNAs. MCF-7 cells were first transfected with control siRNA or hnRNP-siRNAs (mixed pool), and then treated with 0.5 μg/ml doxo for 16 h before harvesting cells for western blot. (E) Effect of ectopic expression of hnRNP I on p53. MCF-7 cells were first transfected with vector or hnRNP I, and then treated with 0.2 μg/ml doxo for 16 h before western blot. The purpose of using a low concentration of doxo was to not allow p53 induction to reach the maximum so that we would be able to detect any further increase in the p53 level by hnRNP I.

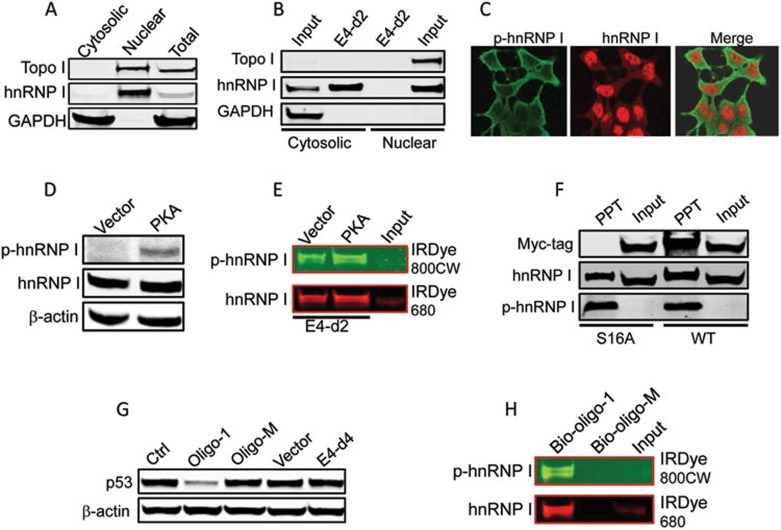

RoR interacts with the phosphorylated hnRNP I in the cytoplasm

Although hnRNP I is a nuclear protein, cell fractionation experiments revealed a small amount of hnRNP I in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A). Of great interest, RNA precipitation combined with western blot suggested that the interaction between hnRNP I and RoR occurs predominantly in the cytoplasm because a strong signal was detected in the cytosolic fraction, whereas little signal was detected in the nuclear fraction (Figure 5B). Furthermore, in situ hybridization (ISH) revealed that RoR is mainly present in the cytoplasm (Supplementary information, Figure S8A). Previous reports indicated that phosphorylation impacts the subcellular localization of hnRNP I33,34. Indeed, immunofluorescence microscopy showed that while a majority of the protein is unphosphorylated and stays in the nucleus, phosphorylated hnRNP I (p-hnRNP I) was present in the cytoplasm (Figure 5C; Supplementary information, Figure S8B). In particular, protein kinase A (PKA) serves a kinase for hnRNP I phosphorylation33. Thus, we ectopically expressed PKA and detected an increase in p-hnRNP I (Figure 5D). Consistent with this finding, hnRNP I pulled down by E4-d2 probe was mainly the phosphorylated form, p-hnRNP I; moreover, a higher level of p-hnRNP I was seen in the PKA-transfected cells compared to the vector control cells (Figure 5E). To further demonstrate the role of phosphorylation of hnRNP I in its ability to interact with RoR, we made a phosphorylation dead mutant (S16A)33 (Supplementary information, Figure S8C). As expected, the wild type, but not the mutant hnRNP I, was recovered from the RoR RNA precipitates (Figure 5F), thus demonstrating that RoR preferably interacts with p-hnRNP I.

Figure 5.

p-hnRNP I is localized to the cytoplasm and interacts with RoR at the hnRNP I binding motifs. (A) Subcellular localization of hnRNP I by cell fractionation. After cell fractionation of MCF-7 cells, an equal amount of protein (30 μg/lane) was loaded for each lane. Note that a very weak hnRNP I band was detected in the cytosolic fraction whereas a strong band came from the nuclear fraction. Topoisomerase I (topo I) serves as a nuclear protein marker; GAPDH as a cytosolic protein marker. (B) Detection of hnRNP I protein after RNA precipitation by western blot. The same cytosolic and nuclear extracts from (A) were used for RNA precipitation. However, since over 95% of hnRNP I is present in the nucleus, we adjusted the amount of protein and used the nuclear protein of about 1/5 amount of the cytosolic protein for RNA precipitation. (C) Detection of hnRNP I and p-hnRNP I by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy. While hnRNP I (red) is predominantly in the nucleus, p-hnRNP I (green) is in the cytoplasm. (D) PKA enhances hnRNP I phosphorylation. (E) RoR-bound hnRNP I is phosphorylated and PKA enhances the interaction of RoR with hnRNP I. Total cellular extract from the same transfected cells in (D) was used for RNA precipitation. The same membrane was probed simultaneously with hnRNP I antibody (rabbit origin) and p-hnRNP I antibody (mouse origin), followed by secondary antibody probing as indicated. (F) Serine phosphorylation of hnRNP I is essential for its interaction with RoR. MCF-7 cells were transfected with wild-type hnRNP I or mutant hnRNP I (S16A). Total cellular extract was prepared for RNA precipitation. (G) Suppression of p53 by RoR-oligo-1. MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector or E4-d4; or control oligo, oligo-1 or oligo-M. The transfected cells were then treated with doxo at 1 μg/ml for 24 h before protein extraction for western blot. (H) Precipitation of hnRNP I by biotin-labeled RNA oligos (Supplementary information, Figure S9B). Total cellular extract from non-transfected MCF-7 cells was prepared for RNA precipitation. The same membrane was probed simultaneously with hnRNP I antibody (rabbit origin) and p-hnRNP I antibody (mouse origin), followed by secondary antibody probing as indicated.

A 28-base RoR sequence carrying hnRNP I binding motifs is fully functional for p53 repression

To determine the minimal region required for p53 repression, we made two additional deletions and narrowed down the active region within a 165 bp fragment (E4-d3B) (Supplementary information, Figure S9A). Of considerable interest, we found two potential hnRNP I binding motifs in this region (Supplementary information, Figure S9B) that are very similar to the conserved hnRNP I binding motif35. Deletion of these two potential hnRNP I binding motifs (E4-d4) abolished the suppression activity (Figure 5G; Supplementary information, Figure S9B and S9C), suggesting that these two motifs are essential. To further determine their role in p53 repression, we introduced a synthetic RNA oligo (RoR-oligo-1) (Supplementary information, Figure S9C) into the cells, and demonstrated that RoR-oligo-1 alone was sufficient to suppress p53 (Figure 5G). In contrast, the same oligo with mutations at 4 conserved cytosines (RoR-oligo-M) lost its ability to suppress p53 (Figure 5G; Supplementary information, Figure S9C), highlighting the critical role of these 4 cytosines. Furthermore, biotin-labeled RoR-oligo-1 was able to successfully pull down hnRNP I, whereas the same oligo with mutations at 4 conserved cytosines (Biotin-oligo-M) was not (Figure 5H). Therefore, RoR-oligo-1 possesses full function of RoR for p53 repression. Together, these results suggest that RoR suppresses p53 through its interaction with the cytoplasmic p-hnRNP I at the hnRNP I binding motifs.

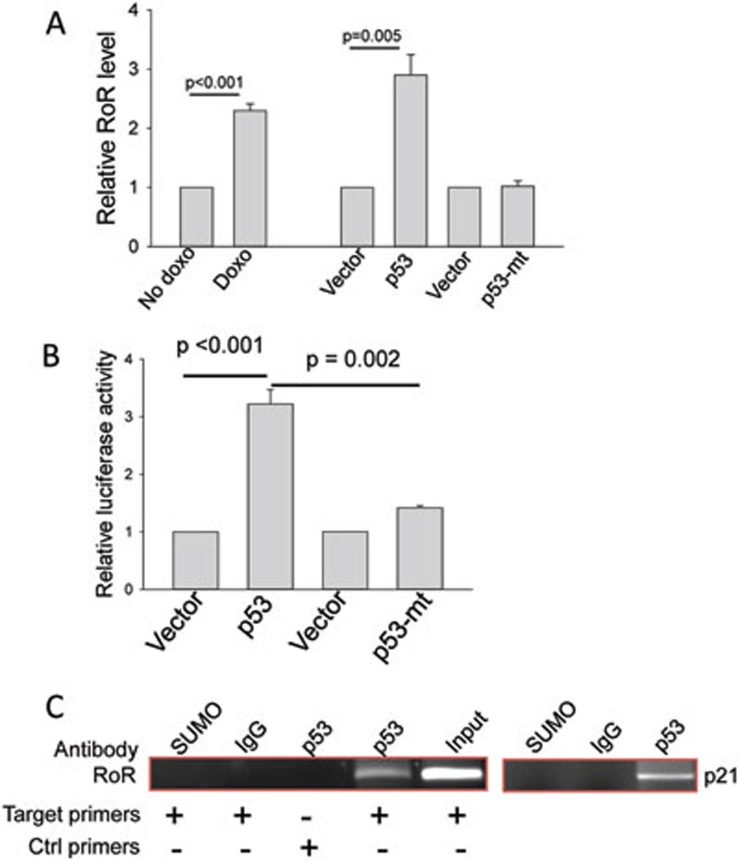

p53 transcriptionally induces RoR

Finally, we showed that RoR itself is under regulation of p53. Doxo induced p53 and at the same time, it increased the RoR level, as detected by qRT-PCR (Figure 6A). Moreover, ectopic expression of p53 also induced RoR (Figure 6A). However, p53 with a point mutation (R175H) at the DNA binding domain, a frequent mutant in cancer36, had no effect on RoR expression. The p53 scan program37 identified 4 potential p53 response elements (p53REs) within a 1 Kb fragment upstream of RoR (Supplementary information, Figure S10A). It is evident that p53RE-1 is the most conserved among all four p53REs (Supplementary information, Figure S10A). Consistent with qRT-PCR results, luciferase assays with a reporter carrying this 1 Kb fragment revealed that p53 increased the luciferase activity by 3-fold (Figure 6B). Again, the mutant p53 had no effect on the luciferase activity (Figure 6B). Deletion and site-directed mutagenesis showed that p53RE-1 was important to the p53-induced activity (Supplementary information, Figure S10B). Deletion of all four p53REs or p53RE-1 alone decreased the luciferase activity to below 40%; similarly, the reporter with mutations in p53RE-1 also showed about 40% of the full-length promoter activity. Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirmed that p53 specifically interacted with p53RE-1 (Figure 6C). Therefore, like the negative regulator MDM2, RoR is also under control of p53, forming an autoregulatory feedback loop (Supplementary information, Figure S11), through which p53 may be delicately kept in check so that the cell is able to better respond to intracellular or extracellular stresses.

Figure 6.

p53 induces RoR by binding to a p53 response element in the RoR promoter. (A) Induction of RoR by p53. Cells were treated with doxo at 1 μg/ml for 24 h and then RNA was extracted for qRT-PCR. In addition, HCT-116 WT cells were transfected with vector alone or WT-p53 or mutant p53 (R175H). Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). (B) Induction of the RoR promoter luciferase activity by p53. A 1 000 bp fragment upstream of RoR was cloned into pGL3-Basic as a luciferase reporter. 293T cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter along with wild-type or mutant (R175H) p53. Luciferase assay was performed 24 h after transfection. Values are mean ± SE (n = 3). (C) Detection of p53 interaction with p53RE-1 by ChIP assay. PCR primers (RoR-ChIP-p53-1–5.1 and RoR-ChIP-p53-1–3.1) were indicated by red arrows (see Supplementary information, Figure S10B). SUMO antibody serves as a negative control, and p21 serves as a positive control.

Discussion

Given the importance of p53 in diverse cellular pathways, the cellular level of p53 protein is under strict control. To achieve this, the cell may develop a sophisticated regulatory system because an unwanted induction of p53 could be harmful to the cell. For instance, the cell may express a number of negative regulators25,26,38. Among them, MDM2 is a major E3 ubiquitin ligase controlling the p53 stability through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway while allowing its rapid increase in response to stress21,39. However, it is unclear whether there is an additional mechanism that can keep the stress-induced p53 level under control. This study demonstrates that RoR is a unique member of p53 negative regulators because RoR is capable of suppressing the cellular p53 level after DNA damage; this RoR-mediated p53 repression is in part through translation regulation.

Our study identifies another important protein, hnRNP I, in this RoR-mediated p53 repression network because the ability of RoR to repress p53 is dependent on the interaction of RoR with hnRNP I and suppression of hnRNP I by RNAi substantially decreases the doxo-induced p53, as RoR does. In particular, a 28-base RoR sequence carrying the potential hnRNP I binding motifs is essential and sufficient for this repression, providing further evidence of the involvement of hnRNP I in RoR-mediated p53 repression. hnRNP I is an RNA binding protein that carries several RNA binding domains and is well known for its role in mRNA splicing40; it is relatively abundant in the cell. While the majority of hnRNP I is retained in the nucleus; small fraction is in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A and 5C). Since mRNA splicing takes place in the nucleus, this function is mostly likely dependent on the nuclear hnRNP I. On the other hand, our study shows that the cytoplasmic hnRNP I is phosphorylated and is responsible for the interaction with RoR because almost all of the pulled down hnRNP I is phosphorylated.

Previous studies suggest that the 5′-UTR of p53 mRNA may form a secondary structure to serve as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)41,42. Translation regulation can also occur through the 3′-UTR. For instance, HuR was shown to bind to either the AU-rich or the U-rich regions of the p53 3′-UTR, leading to an increase in p53 translation after UVC treatment43. On the other hand, RNPC1 functions as a translational repressor by binding to the 5′- and 3′-UTR of p53 mRNA so that it prevents cap-binding protein eIF4E from binding to p53 mRNA30. Moreover, p53 protein is capable of binding to the 5′-UTR of p53 mRNA and inhibiting its translation44. We showed that hnRNP I binds to p53 mRNA (Supplementary information, Figure S7C), which is consistent with the report that hnRNP I is capable of binding to the IRES to stimulate p53 translation after DNA damage, leading to the production of the N-terminal truncated isoform of p5345. Thus it is possible that RoR may prevent or interrupt the interaction of hnRNP I with p53 mRNA to suppress p53.

MDM2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase and regulates the p53 stability; it is no longer able to bind to p53 upon stress, so that p53 is rapidly increased. Unlike MDM2, RoR is able to keep the p53 level low even after DNA damage. This is critical because in this way, RoR may serve as a check point to prevent p53 induction from “out of control”. A delicate balance of these two mechanisms would assure cells to precisely respond to various stresses. In addition to negative regulators of E3 ubiquitin ligases, other notable p53 regulators include ribosomal proteins, such as RPL26 and RPL11, and RNA binding proteins such as RNPC1. For instance, RPL26 has been shown to directly bind to the 5′- and 3′-UTR of p53 mRNA in a way that facilitates p53 translation,28,29 although RPL26 can also interact with MDM2 and regulate the p53 stability46. Similarly, ribosomal proteins such as RPL11 have been reported to bind to MDM2 protein and increase the p53 protein stability by inhibiting the association of MDM2 with p5347,48,49. Suppression of RPL11 by PICT1 causes p53 repression and promotes cell growth50. Although both RPL26 and RNPC1 are involved in p53 translation, we found no evidence that RoR interacts with RPL26 or RNPC1. Thus, the mechanism of p53 regulation involving these proteins may also be distinct from what we have reported here. Nevertheless, both positive and negative translational control of p53 by these proteins, along with RoR, may be part of the highly coordinated response of cells to DNA damage and other cellular stresses.

One of the interesting findings is the transcriptional regulation of RoR by p53. MDM2 inhibits p53, which, however, is able to induce MDM2. Like MDM2, RoR is also under control of p53. This autoregulatory feedback loop may signify the critical role of RoR as an important p53 repressor. As discussed above, an unwanted induction of p53 could be deleterious to the cell. In order for the cell to keep p53 at a certain level, the cell has to control the p53 level precisely. One of such mechanisms may involve RoR-mediated suppression because the RoR level is also increased when p53 is induced (Supplementary information, Figure S11). Although the mouse lincRNA-p2151 and the human lncRNA PANDA12 were recently shown to be targets of p53, unlike these lncRNAs, RoR functions to suppress p53 by a novel negative feedback loop. Given that microRNAs are well known as direct p53 targets52, as a member of lncRNAs, RoR now also joins the p53 network, providing another piece in the tumor suppression puzzle. Along with these findings, our study provides further evidence that non-coding RNAs, particularly RoR in this case, are important inter-players in the p53-mediated tumor suppression network.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Primary antibodies were purchased from the following commercial vendors: p53 (both N- and C-terminal), phosphorylated p53 (Ser15), MDM2 from Epitomics; acetylated p53 (K382), p21, RPL26 from Cell Signaling; hnRNP I, Pirh2 and MDMX from Santa Cruz; COP1 from Abcam; GAPDH from ProteinTech; RNPC1 (or RBM38), β-actin from Sigma; Myc-tag from Applied Biological Materials (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Secondary antibodies conjugated with IRDye 800CW or IRDye 680 were from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE, USA); 35S methionine from Perkin Elmer; PCR primers and RNA oligos were purchased from IDT (Coralville, IA, USA); hnRNP I siRNAs (mixed pool) from Santa Cruz. Breast tumor RT-PCR arrays from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA); RoR-siRNA-1/2 and negative control oligo from Thermo Scientific; RoR-LNA oligo for ISH from Exiqon (2950 Vedbaek, Denmark); the PKA cDNA clone from Open Biosystems; mutant p53 (R175H) from Addgene; nutlin from Sigma. The original RoR in pBabe was a generous gift from Dr Daley (Harvard Medical School) and it was used as a PCR template to generate various RoR constructs in this study. Antibody against p-hnRNP I (Ser16) was a generous gift from Dr Black (UCLA).

Cell culture

Breast cancer MCF-7 cells (both from ATCC) and colon cancer cell lines HCT-116 (wild-type p53 and p53 null) (provided by Dr. Voglestein at The Johns Hopkins University) were grown in RPMI 1640 (Lonza, Walkersville, MD). HEK-293T (ATCC) cells were cultured in DMEM (Lonza). All culture media were supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units of penicillin/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and supplemented with 5% CO2 in the humidified chamber.

Transfection

Cells were transfected with siRNAs or RNA oligos using RNAfectin reagent or with plasmid DNA using DNAfectin (Applied Biological Materials) following the manufacturer's protocol. Sequences for RoR-siRNA-1 and RoR-siRNA-2 were described previously19.

Plasmid construction

All PCR primers for cloning were listed in Supplementary information, Table S1 and high fidelity enzyme Phusion was used for PCR amplification. The entire RoR sequence was PCR amplified from the original RoR expression vector in pBabe using primers RoR-R1–5.1 (sense) and RoR-Not1–3.1 (antisense) and then directly cloned into a lentiviral vector under MSCV promoter by Cold Fusion kit (SBI). The same strategy was used to clone various lengths of RoR fragments in this study unless it was specifically stated. The cloning of RoR putative promoter used human genomic DNA as a template with RoRp-Xho1–5.1 and RoRp-Xho1–3.1 and was cloned into pGL3-basic (Promega) at Xho I site by Cold Fusion; various deletions and site-directed mutagenized sequences were also made in the same vector. PKA, hnRNP1, RPL26 and RNPC1 were cloned into a modified pCDH-CMV-EF1-copGFP that carried Myc-tag at the N-terminus. RoR was also cloned into a mCherry-carrying expression vector by a standard ligation method; this clone was used in TUNEL assays. To make RoR or RoR promoter constructs carrying deletions or mutations, a two-step PCR procedure was used as described previously53. All PCR products were verified by DNA sequencing.

Luciferase assay

Luciferase assays were performed using a luciferase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, cells were first transfected with appropriate plasmids in 12-well plates. Then the cells were harvested and lysed for luciferase assay 24 h after transfection. Renilla luciferase was used for normalization.

qRT-PCR

To detect the transcriptional level of RoR and p53, we used the SYBR Green method with primers listed in Supplementary information, Table S1. PCR was carried out in ABI 7500 real time PCR system. PCR results, recorded as threshold cycle numbers (Ct), were normalized against an internal control (β-actin).

Western blot

Cells were harvested and protein was extracted from transfected cells as previously described20 using pre-casted SDS-gels (Thermo Scientific) at 12% or 4%-20% gradient.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

To determine the subcellular localization of hnRNP I, we performed immunofluorescence staining using the hnRNP I as well as p-hnRNP I antibody according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). The signal was revealed by a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568. Confocal microscopy was carried out by using the Leica confocal microscope at the imaging facility of Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

TUNEL assays

MCF-7 cells were transfected with vector or RoR carrying mCherry and then treated with doxo at 2 μg/ml for 24 h. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, and permeabilized in 0.25% Triton-X 100 for 20 min at room temperature. TUNEL assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Briefly, the cells were first incubated in TdT reaction cocktail for 60 min at 37 °C, followed by treatment with Click-iT reaction cocktail. The nucleus was stained with Hoechst 33342.

Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle analysis was performed using the standard propidium iodide method. In brief, HCT-116 WT, HCT-116 p53-null cells were first transfected with either vector control or RoR expression vector. The transfected cells were then treated with doxo at 0.1 μg/ml for 16 h before harvesting for cell cycle analysis. After fixing with 70% ethanol, the cells were stained with propidium iodide along with RNase A. Finally, the cells were analyzed by FACS Vantage flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) at the core facility of Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

RIP

To determine whether hnRNP I interacts with RoR, we used hnRNP I antibody to pull down hnRNP I and then detected RoR RNA by RT-PCR using RoR specific primers (ROR-Exon4-RT-5.1A and ROR-Exon4-RT-3.1A) in Supplementary information, Table S1. Magna RIP™ RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation Kit (Millipore) was used for RIP procedures according to the manufacturer's protocol. After the antibody was recovered by protein A+G beads, standard RT-PCR was performed to detect RoR RNA in the precipitates.

RNA precipitation

This experiment used RNA probes to precipitate RNA binding proteins. Thus, the DNA fragment covering RoR exon 3 or E4-d2 was PCR-amplified using a T7 containing primer and then cloned into pCR8 (Invitrogen). In addition, the full-length RoR was also cloned and used in precipitation experiments for comparison. The resultant plasmid DNA was linearized with restriction enzyme Not I (the stie was introduced from the reverse PCR primer), and then used to synthesize RNA by T7 polymerase. A 20 μl reaction contained 400 ng linearized plasmid DNA, 20 U ribonuclease inhibitor, 2.5 mM NTP mixture supplemented with 10% biotin-labeled UTP (Perkin Elmer) and 20 U T7 RNA polymerase (New England BioLabs); and then it was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, followed by 25 U RNase-free DNase I (New England BioLabs) treatment at 37 °C for 30 min. The labeled RNA was purified by a column-based kit (Zymo Research). Cellular extract was prepared from a 10 cm dish culture with ∼80% confluence (about 8 million cells) with protein lysis buffer54. In addition to total protein extract, we also prepared cytosolic and nuclear fractions with cell membrane lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 100 μM DTT, 0.5% NP-40) containing protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma). After a brief spin, supernatant was saved as a cytosolic fraction, and nuclear lysis buffer (500 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.8, 100 μM DTT, 10% glycerol) containing protease inhibitor cocktails was then added to the pellet to extract nuclear protein. For precipitation assays, the reaction (RNA probe and protein extract) was incubated at 4 °C for 60 min, followed by 5 washes with PBS. For experiments with biotin-labeled RoR-oligo-1 and mutant oligo-1, the RNA oligos (100 pmole each) were directly used in precipitation assay.

Pulse-chase experiment

MCF-7 cells were first transfected with control siRNA or RoR-siRNA-2 overnight and then grown in regular DMEM medium at the exponential stage before replacing pre-warm DMEM minus methionine with 10% dialyzed FBS (Invitrogen) and incubated for 30 min. After removal of medium, the cells were incubated in the same fresh medium containing 30 μl of ∼10 μCi /μl L-35>S methionine (Perkin Elmer) for 1 h. Finally, the radioactive medium was removed and fresh warm DMEM + 10% FBS + 2 mM cold methionine was added to dishes. After incubation for 30 min, the cells were harvested for IP with anti-p53 antibody, followed by SDS-PAGE. The gel was dried under vacuum, and then exposed to an X-ray film for 16-24 h before development.

Protein ID identification by mass spectrometry

After RNA precipitation, samples were separated in SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Candidate protein bands were carefully cut out and sent out for mass spectrometry analysis provided by Applied Biomics.

ChIP

ChIP assays were performed using a commercial kit from Cell Signaling. Briefly, cells were first fixed with formaldehyde, and chromatin DNA was isolated and digested with nucleases. PCR was performed using primers RoR-ChIP-p53-1–5.1 and RoR-ChIP-p53-1–3.1 or control primers RoR-ChIP-p53-1–5.1A and RoR-ChIP-p53-1–3.1A (Supplementary information, Table S1). IgG and an unrelated antibody (anti-SUMO) were used as negative controls; p21 was used as a positive control.

ISH

ISH was used to detect RoR expression in cultured MCF-7 cells using a biotin-labeled antisense RoR-LNA probe according to a published method55. In brief, cells were first grown on coverslips overnight and then fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Following pre- and hybridization, and washes, the signal was amplified by TSA amplification kit (Perkin Elmer) and subsequently revealed by Ultra Vision One polymer and AEC chromogen (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE; the Student's t-test was used for assessing the difference between individual groups and P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr George Daley (Harvard Medical School) for providing the original clone of RoR; Dr Douglas Black (University of California, Los Angeles) for phosphorylated hnRNP I antibody, and Dr Vert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University) for HCT-116 p53 WT and HCT-116 p53 null cells. We thank Dr Xiao-wei Wang (Washington University at St. Louis) for helping us with UCSC genome browser analysis. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA154989 (YM) and R01 CA124650 (KW).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Material

RoR suppresses the DNA damage-induced p53 protein level.

RoR has no effect on the doxo-induced G2/M arrest in HCT-116 p53 null cells.

RoR has no effect on p53 mRNA, as detected by qRT-PCR.

A UCSC genome browser search identified no RoR counterpart from mouse, dog, elephant, opossum or chicken. Human RoR exons were in red circles.

A procedure for preparation of biotin-labeled RoR probes.

Identification of hnRNP I as a potential RoR-binding protein.

Interaction of hnRNP I with RoR and p53 mRNA.

(A) RoR is predominantly in the cytoplasm (MCF-7 cells) as detected by in situ hybridization.

Identification of an active region in RoR responsible for p53 repression.

p53 induces RoR by binding to p53RE in the RoR promoter.

The RoR-p53 autoregulatory feedback loop.

Primers used in this study

References

- Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell. 2009;137:413–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek DW, Anderson CW. Posttranslational modification of p53: cooperative integrators of function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000950. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaby MJ, Yang DQ. p53 translational control: a new facet of p53 regulation and its implication for tumorigenesis and cancer therapeutics. Gene. 2007;395:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prensner JR, Chinnaiyan AM. The emergence of lncRNAs in cancer biology. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:391–407. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW. The antisense transcriptomes of human cells. Science. 2008;322:1855–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1163853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami M. Small RNAs: Pseudogenes act as microRNA decoys. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:535. doi: 10.1038/nrc2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B, Haveman WJ, Pandolfi PP. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman M, Donaghey J, Carey BW, et al. lincRNAs act in the circuitry controlling pluripotency and differentiation. Nature. 2011;477:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature10398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung T, Wang Y, Lin MF, et al. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prensner JR, Iyer MK, Balbin OA, et al. Transcriptome sequencing across a prostate cancer cohort identifies PCAT-1, an unannotated lincRNA implicated in disease progression. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:742–749. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Yang YW, Liu B, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KC, Chang HY. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2011;43:904–914. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva M, Zhu S, Wu F, et al. p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3207–3212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808042106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K, Herrera JE, Saito S, et al. DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation-acetylation cascade. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–2841. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivoactivation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2 Science 2004303844–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torarinsson E, Yao Z, Wiklund ED, et al. Comparative genomics beyond sequence-based alignments: RNA structures in the ENCODE regions. Genome Res. 2008;18:242–251. doi: 10.1101/gr.6887408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shvarts A, Steegenga WT, Riteco N, et al. MDMX: a novel p53-binding protein with some functional properties of MDM2. EMBO J. 1996;15:5349–5357. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornan D, Wertz I, Shimizu H, et al. The ubiquitin ligase COP1 is a critical negative regulator of p53. Nature. 2004;429:86–92. doi: 10.1038/nature02514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng RP, Lin Y, Ma W, et al. Pirh2, a p53-induced ubiquitin-protein ligase, promotes p53 degradation. Cell. 2003;112:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kastan MB. 5′-3′-UTR interactions regulate p53 mRNA translation and provide a target for modulating p53 induction after DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2146–2156. doi: 10.1101/gad.1968910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M, Absalon MJ, McLure KG, Kastan MB. Regulation of p53 translation and induction after DNA damage by ribosomal protein L26 and nucleolin. Cell. 2005;123:49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cho SJ, Shu L, et al. Translational repression of p53 by RNPC1, a p53 target overexpressed in lymphomas. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1528–1543. doi: 10.1101/gad.2069311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G, Matunis MJ, Pinol-Roma S, Burd CG. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:289–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo JM, Majos N, Bonnal S, et al. Regulation of Fas alternative splicing by antagonistic effects of TIA-1 and PTB on exon definition. Mol Cell. 2005;19:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Lee JA, Kress TL, Mowry KL, Black DL. Protein kinase A phosphorylation modulates transport of the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8776–8781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoch KP, Meisterfeld R, Kersting S, et al. cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of PTB1 promotes the expression of insulin secretory granule proteins in beta cells. Cell Metab. 2006;3:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillmar L, Carlsson C, Welsh N. Control of insulin mRNA stability in rat pancreatic islets. Regulatory role of a 3′-untranslated region pyrimidine-rich sequence. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1099–1106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soussi T, Ishioka C, Claustres M, Beroud C. Locus-specific mutation databases: pitfalls and good practice based on the p53 experience. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeenk L, van Heeringen SJ, Koeppel M, et al. Characterization of genome-wide p53-binding sites upon stress response. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3639–3654. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal D, Tovar C, Yang H, Vu BT, Heimbrook DC, Vassilev LT. Activation of p53 by MDM2 antagonists can protect proliferating cells from mitotic inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1918–1924. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meek DW. Tumour suppression by p53: a role for the DNA damage response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:714–723. doi: 10.1038/nrc2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberstrass FC, Auweter SD, Erat M, et al. Structure of PTB bound to RNA: specific binding and implications for splicing regulation. Science. 2005;309:2054–2057. doi: 10.1126/science.1114066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray PS, Grover R, Das S. Two internal ribosome entry sites mediate the translation of p53 isoforms. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:404–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang DQ, Halaby MJ, Zhang Y. The identification of an internal ribosomal entry site in the 5′-untranslated region of p53 mRNA provides a novel mechanism for the regulation of its translation following DNA damage. Oncogene. 2006;25:4613–4619. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazan-Mamczarz K, Galban S, Lopez de Silanes I, et al. RNA-binding protein HuR enhances p53 translation in response to ultraviolet light irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8354–8359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432104100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosner J, Mummenbrauer T, Bauer C, Sczakiel G, Grosse F, Deppert W. Negative feedback regulation of wild-type p53 biosynthesis. EMBO J. 1995;14:4442–4449. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover R, Ray PS, Das S. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein regulates IRES-mediated translation of p53 isoforms. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2189–2198. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofir-Rosenfeld Y, Boggs K, Michael D, Kastan MB, Oren M. Mdm2 regulates p53 mRNA translation through inhibitory interactions with ribosomal protein L26. Mol Cell. 2008;32:180–189. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrum MA, Ludwig RL, Kubbutat MH, Hanlon M, Vousden KH. Regulation of HDM2 activity by the ribosomal protein L11. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:577–587. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00134-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KP, Itahana K, Jin A, Zhang Y. Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 2004;23:2402–2412. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Kawahara K, Nishio M, et al. Regulation of the MDM2-P53 pathway and tumor growth by PICT1 via nucleolar RPL11. Nat Med. 2011;17:944–951. doi: 10.1038/nm.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, He X, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ. microRNAs join the p53 network--another piece in the tumour-suppression puzzle. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nrc2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Si ML, Wu H, Mo YY. MicroRNA-21 targets the tumor suppressor gene tropomyosin 1 (TPM1) J Biol Chem. 2007;282:14328–14336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611393200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Chiocca S, Beck WT, Mo YY. Gam1-associated alterations of drug responsiveness through activation of apoptosis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1823–1830. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Mo YY. Detection of microRNAs in cultured cells and paraffin-embedded tissue specimens by in situ hybridization. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;676:73–83. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-863-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

RoR suppresses the DNA damage-induced p53 protein level.

RoR has no effect on the doxo-induced G2/M arrest in HCT-116 p53 null cells.

RoR has no effect on p53 mRNA, as detected by qRT-PCR.

A UCSC genome browser search identified no RoR counterpart from mouse, dog, elephant, opossum or chicken. Human RoR exons were in red circles.

A procedure for preparation of biotin-labeled RoR probes.

Identification of hnRNP I as a potential RoR-binding protein.

Interaction of hnRNP I with RoR and p53 mRNA.

(A) RoR is predominantly in the cytoplasm (MCF-7 cells) as detected by in situ hybridization.

Identification of an active region in RoR responsible for p53 repression.

p53 induces RoR by binding to p53RE in the RoR promoter.

The RoR-p53 autoregulatory feedback loop.

Primers used in this study