Abstract

A growing body of evidence supports the existence of an extensive network of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) whose combinatorial binding affects the post-transcriptional fate of every mRNA in the cell—yet we still do not have a complete understanding of which proteins bind to mRNA, which of these bind concurrently, and when and where in the cell they bind. We describe here a method to identify the proteins that bind to RNA concurrently with an RBP of interest, using quantitative mass spectrometry combined with RNase treatment of affinity-purified RNA–protein complexes. We applied this method to the known RBPs Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3. Our method significantly enriched for known RBPs and is a clear improvement upon previous approaches in yeast. Our data reveal that some reported protein–protein interactions may instead reflect simultaneous binding to shared RNA targets. We also discovered more than 100 candidate RBPs, and we independently confirmed that 77% (23/30) bind directly to RNA. The previously recognized functions of the confirmed novel RBPs were remarkably diverse, and we mapped the RNA-binding region of one of these proteins, the transcriptional coactivator Mbf1, to a region distinct from its DNA-binding domain. Our results also provided new insights into the roles of Nab2 and Puf3 in post-transcriptional regulation by identifying other RBPs that bind simultaneously to the same mRNAs. While existing methods can identify sets of RBPs that interact with common RNA targets, our approach can determine which of those interactions are concurrent—a crucial distinction for understanding post-transcriptional regulation.

Life depends on the coordinated temporal, spatial, and stoichiometric regulation of gene expression. Combinatorial binding by specific transcription factors allows for the concerted temporal regulation of large sets of genes in physiological and developmental programs at a transcriptional level. The resulting RNA transcripts are also subject to further regulation at the levels of RNA processing, transport, localization, translation, and degradation. The added dimensions of regulation provided by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) enable more precise temporal, spatial, and stoichiometric control of protein production (Wang et al. 2002; Paquin et al. 2007; Jansen et al. 2009; Kurischko et al. 2011). Specific RBPs bind to distinct sets of mRNAs, typically encoding proteins destined for similar subcellular localizations or with related biological functions, suggesting a model in which concerted, combinatorial binding of specific mRNAs by specific sets of RBPs can affect the post-transcriptional fate of potentially every mRNA in the cell (Hieronymus and Silver 2003; Gerber et al. 2004; Ong et al. 2004; Keene 2007a,b; Hogan et al. 2008). Despite the many lines of evidence pointing to pervasive post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression mediated by RBPs, we still do not have a complete understanding of which proteins bind to mRNA, which of these bind concurrently, and when and where in the cell they bind.

Previous global approaches to identify proteins that interact with mRNAs in yeast have been mostly focused on in vitro binding, mass spectrometry, or computational predictions. Although powerful, these techniques may miss complex RNA–protein interactions assembled in vivo, less abundant RBPs, and RBPs that lack domains known to bind RNA (Butter et al. 2009; Scherrer et al. 2010; Tsvetanova et al. 2010). In fact, >75% (503 out of 647) of the proteins annotated as RBPs lack domains known to bind RNA (Tsvetanova et al. 2010). Conversely, despite the fact that ∼10% of the yeast proteome is annotated as “known” RBPs (annotated in the yeast genome database, experimentally validated, or with homology with known RNA-binding domains), some proteins not annotated as RBPs nonetheless reproducibly copurify with distinct sets of RNAs in vivo (Hogan et al. 2008). The known functions of some RBPs would not suggest their involvement in the post-transcriptional regulation of RNA. For example, the metabolic enzyme aconitase, which catalyzes the isomerization of citrate to isocitrate, also functions as an RNA-binding protein, binding to iron regulatory elements in target mRNAs to regulate their translation or stability in response to iron availability (Hentze et al. 1987a,b; Casey et al. 1988; Leibold and Munro 1988; Rouault et al. 1989; Bertrand et al. 1993). Previous work using protein microarrays to search for new RNA-binding proteins in yeast identified additional unexpected RBPs, including several enzymes (Scherrer et al. 2010; Tsvetanova et al. 2010). Recently, two papers used mass spectrometry to identify hundreds of novel RBPs in human cells (Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012). These and other examples suggesting regulatory RNA-binding activity in unexpected proteins highlight the need for additional experimental methods to enable the quantitative, unbiased, and accurate discovery of novel RNA–protein interactions from complexes assembled in vivo.

The post-transcriptional operon model hypothesizes that the fate of a given mRNA molecule is influenced by the concerted, combinatorial binding of specific RBPs (Keene 2007a,b)—yet we know surprisingly little about which RBPs bind to mRNAs concurrently. It is thought that the specific complement of RBPs bound to a given mRNA specifies its post-transcriptional fate, but nearly all existing data are limited to defining pairwise interactions between a single RBP and a single mRNA species. Previous work to identify the mRNA targets bound by individual RBPs has mostly relied on purification of the RBP from a whole-cell lysate followed by analysis of the copurifying mRNAs (Gerber et al. 2004; Ule et al. 2005; Keene 2007a,b; Hogan et al. 2008; Bohnsack et al. 2009; Granneman et al. 2009, 2010; Wolf et al. 2010; Scherrer et al. 2011; Schenk et al. 2012). These approaches do not differentiate between two RBPs that bind simultaneously to their common mRNA targets and two RBPs that bind to a common set of mRNA targets but at different times or in different cellular locations. This limits our understanding of post-transcriptional regulation, because from birth to death the average mRNA molecule is estimated to be bound by at least 10 different known RBPs during the entirety of its processing, export, transport, localization, translation, and degradation (Hogan et al. 2008). The post-transcriptional regulatory network is determined not only by which RBPs bind to a given mRNA, but in what temporal programs and in what combinations with other RBPs. Identifying well-characterized RBPs that bind mRNAs simultaneously with an RBP of unknown role would provide immediate clues to its functions. For example, if an uncharacterized RBP binds concurrently with RBPs known to be involved in splicing, the uncharacterized RBP can be inferred to bind in the nucleus during splicing and possibly play a role in splicing.

Mass spectrometry (MS)–based proteomics is a powerful tool for studying cellular interactions, especially if used in a quantitative format. Stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture, SILAC (Mann 2006), is one such quantitative proteomics technology, and it can be used to detect selective enrichment. This technique has been applied to GFP-tagged proteins (Trinkle-Mulcahy et al. 2008; Hubner et al. 2010), modified peptides (Schulze and Mann 2004), DNA (Mittler et al. 2009), and RNA (Butter et al. 2009; Baltz et al. 2012; Castello et al. 2012; Scheibe et al. 2012) to identify previously unknown binders. Here we used quantitative mass spectrometry combined with RNase treatment of affinity-purified RNA–protein complexes assembled in vivo to identify the proteins that bind to RNA concurrently with the known RBPs Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3.

Results

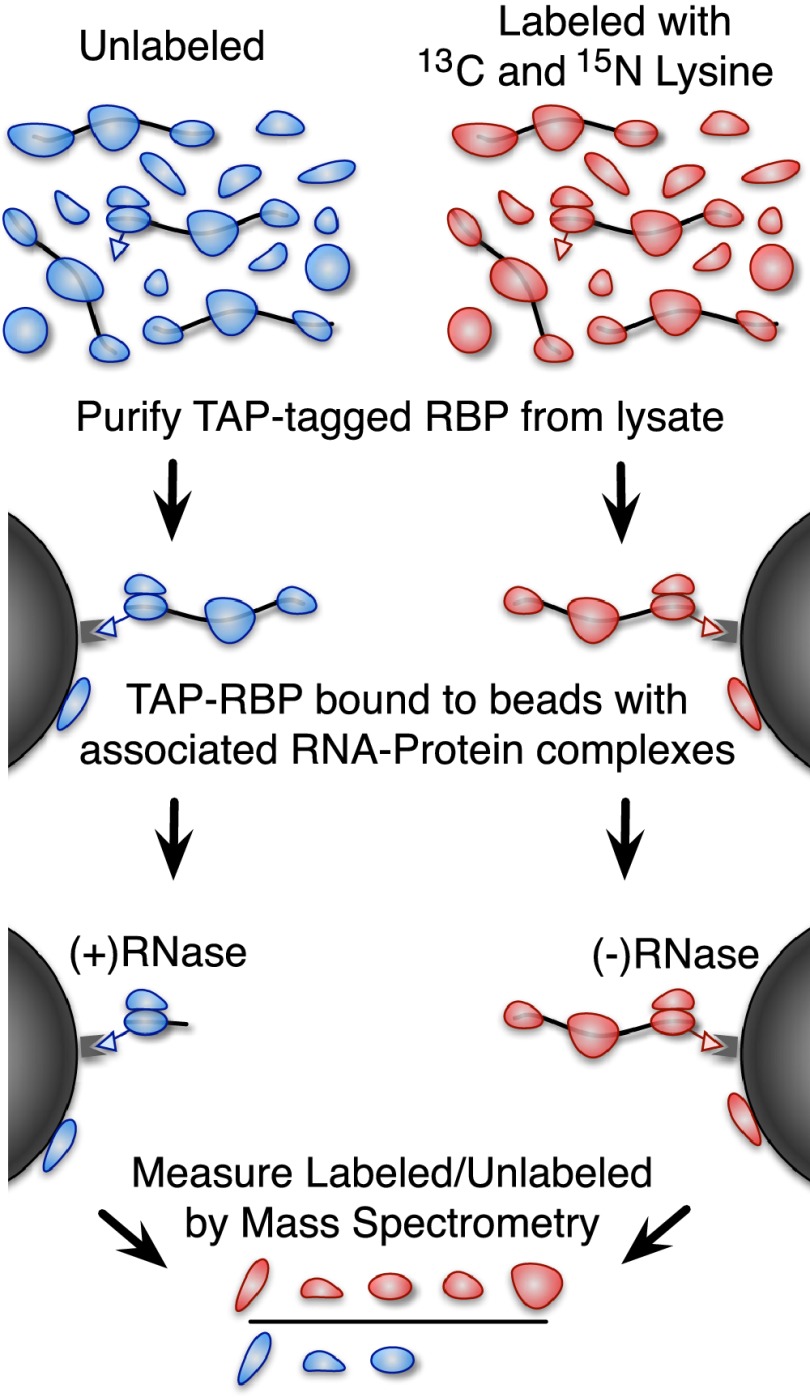

A quantitative proteomic method for identifying RNA-dependent protein interactions

We used quantitative mass spectrometry to identify the proteins that copurify with a protein of interest in an RNA-dependent manner (Fig. 1). We first purified a TAP-tagged protein by IgG–protein-A affinity purification from a “light” (unlabeled) cell lysate and from a “heavy” lysate labeled by incorporation of 13C and 15N isotope–enriched lysine. We then divided the IgG beads with the associated TAP-tagged protein into two equal parts and digested one of them with RNase. Finally, we combined heavy-labeled lysate not treated with RNase with light RNase-treated lysate and quantified the heavy-to-light SILAC ratio by mass spectrometry. By design, this assay specifically measures enrichment due to RNA-dependent association with the TAP-tagged protein. The reverse or ‘label-swapped’ experiment, where instead a heavy-labeled RNase-treated lysate was combined with light (unlabeled) lysate without RNase treatment, served as a replicate and a control for contaminant proteins that are unlabeled in both experiments.

Figure 1.

A method for identifying RNA-dependent protein interactions. An overview of our proteomic method for identifying RNA-dependent protein interactions. A yeast strain with a TAP-tagged protein of interest is grown in media labeled with heavy (13C and 15N isotope enriched) lysine or unlabeled media. The cells are lysed and the protein of interest is purified using the TAP tag. The unlabeled sample is treated with RNase, and the heavy labeled sample is not. The beads are then boiled in SDS-PAGE buffer to release any bound proteins and combined as heavy labeled RNase untreated and unlabeled treated with RNase (we also performed the inverse as a replicate and to control for labeling-related artifacts). The heavy-to-light ratio measured by mass spectrometry indicates the fraction of the bound protein that was liberated by RNase treatment.

The resulting heavy-to-light SILAC ratios are a measure of the RNA-dependent copurification of a given protein with the TAP-tagged protein of interest. When the heavy labeled sample is not treated with RNase and the light sample is treated with RNase, proteins that are lost from the beads in response to RNase treatment will be present more in the heavy labeled sample than the light sample. Consequently, proteins will tend to have heavy-to-light ratios greater than one if they copurify with the TAP-tagged protein of interest in an RNA-dependent manner. For the reverse experiment, in which the heavy labeled sample is treated with RNase and the light sample is not, proteins will have heavy-to-light ratios less than one if they copurify with the TAP-tagged protein of interest in an RNA-dependent manner. To make the results of these replicates directly comparable, we invert the heavy-to-light ratios in the reversed experiment. For simplicity, we represented RNA dependence as the ratio of (−) RNase to (+) RNase, so that RNA-dependent binders would always be expected to have (−/+) RNase ratios greater than one if they copurify with the TAP-tagged protein of interest in an RNA-dependent manner, regardless of the labeling scheme.

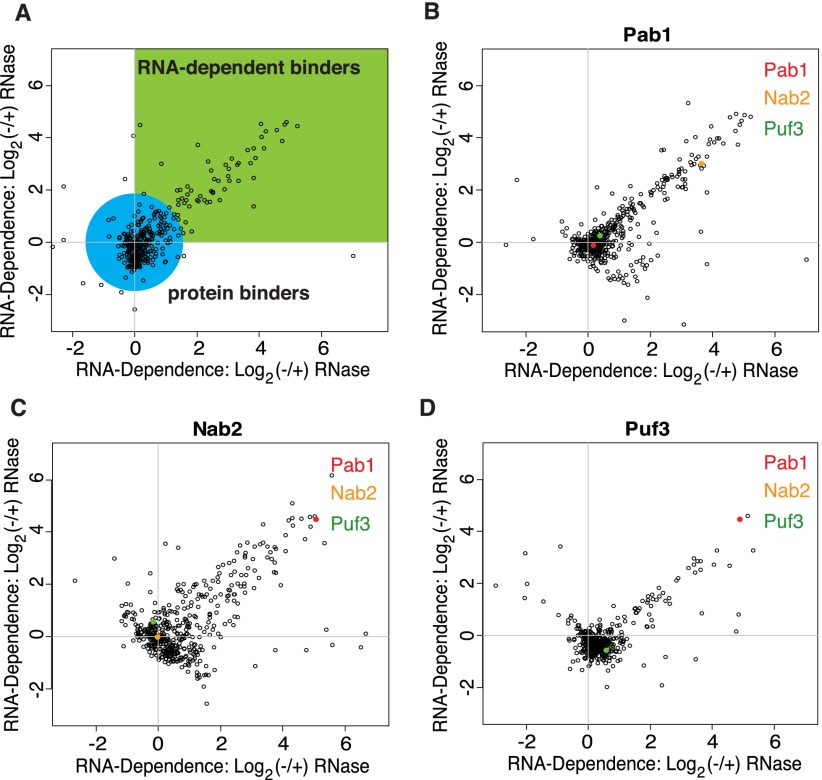

We used this method to identify proteins that interact in an RNA-dependent manner with the RBPs Pab1, Nab2, or Puf3, respectively. Pab1 and Nab2 have each been shown to bind to more than a thousand different mRNAs, while Puf3 binds to a smaller, highly specific set of mRNAs (Gebauer and Hentze 2004; Gerber et al. 2004; Hogan et al. 2008). To assess the scale and reproducibility of the data, we plotted the RNA dependence of each protein as the (log2) (−/+) RNase ratios from the two replicate experiments for Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3 (Fig. 2). In these plots, the reproducible RNA-dependent binders (RDBs) form a tail along the diagonal, while proteins that interact directly with the tagged protein, independent of RNA, are clustered around the origin. As a standard measure of RNA-dependent association with the TAP-tagged protein, we first normalized the (−/+) RNase ratios to set the ratio for the TAP-tagged protein itself to one, based on the premise that enrichment of the TAP-tagged protein itself should not be RNA dependent. We then averaged the (−/+) RNase ratios in both replicate experiments and used the base 2 logarithm of this value as our standard measure of RNA-dependent association with the TAP-tagged protein (referred to as RNA-dependence values).

Figure 2.

Overview of RNA-dependent interaction data. A scatterplot of the RNA-dependent enrichment values as the log base 2 (−/+) RNase ratios for two replicates (with inverted labeling schemes) of each protein that we purified. The reproducible RNA-dependent binders form a tail in quadrant 1. (A) A plot of example data with a green box indicating the quadrant where RNA-dependent binders are expected to be found and a blue circle indicating where RNA-independent binders are expected to be found. These colored regions are broad generalizations only and were not used for actual data analysis. (B) A scatterplot of the log base 2 (−/+) RNase ratios for the replicate experiments with Pab1. The points representing the proteins Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3 are highlighted in red, yellow, and green, respectively. (C) The same scatterplot for experiments with the protein Nab2. (D) The same scatterplot for experiments with the protein Puf3.

To initially evaluate the performance of this assay, we compared the distribution of RNA-dependence values for proteins annotated as RBPs and proteins without such an annotation (Supplemental Fig. S1). The RNA-dependence values for annotated RBPs were significantly shifted toward higher values in the Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3 purifications (P-values 4 × 10−8, 2 × 10−5, and 3 × 10−7, respectively), showing that the method enables RNA-dependent binders (RDBs) to be identified and that proteins with larger RNA-dependence values are more likely to be annotated as RBPs. Although results from traditional mass spectrometry have frequently been biased by protein abundance, we found no correlation between protein abundance and the RNA-dependence values (Supplemental Fig. S2). This demonstrates that our classification of the proteins we detected as RDBs was not affected by their abundance.

To establish a conservative cutoff for the classification of proteins into RNA-dependent and RNA-independent binders, we created a null distribution by modeling RNA-dependence values for proteins with RNA-independent interactions with Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3. To do this, we made two assumptions: first, that after normalization any RNA-dependence values less than zero have a true value of zero and the observed variation from zero is due to noise; and second, that this noise is symmetric about zero (see Methods). We used the null distribution as the basis for estimating an empirical false discovery rate (FDR) for classification of proteins as RDBs, with an FDR threshold of 10% (Supplemental Fig. S3).

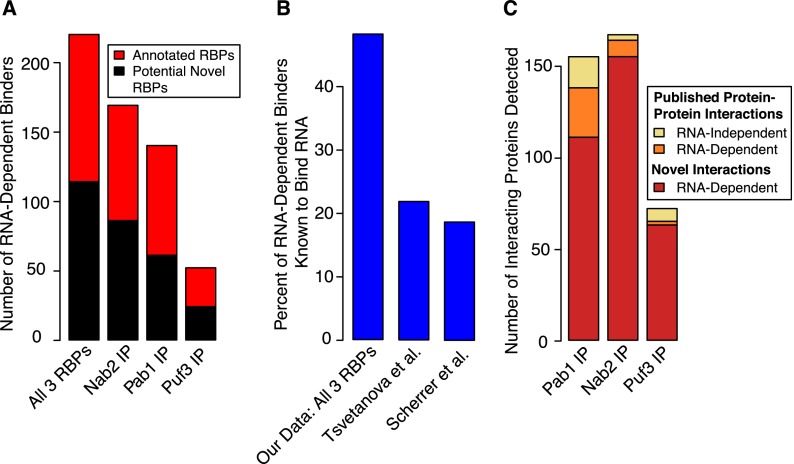

At least half of the proteins classified as RDBs based on our 10% empirical FDR threshold were proteins known to bind RNA (Fig. 3A). In the combined data set, there were 220 RDBs, 48% of which were known RNA-binding proteins. This represents a significant enrichment of known RBPs relative to the set of all proteins that can be detected by mass spectrometry from a yeast whole-cell lysate (∼15%, hypergeometric P-value 2 × 10−35) (Supplemental Table S7; de Godoy et al. 2008). We also examined a published data set of “high-confidence” protein–protein interactions based on large-scale affinity mass spectrometry studies (Gavin et al. 2006; Krogan et al. 2006; Collins et al. 2007), and we discovered that the majority of the previously published physically interacting proteins with Pab1 and Nab2 that we detected in our purifications were actually RNA dependent, suggesting that protein interactions involving RNA-binding proteins (especially those that bind to thousands of different RNAs) may often be indirect and mediated by concurrent binding to RNA molecules (see the Supplemental Material for further information).

Figure 3.

Barplots showing enrichment of known RNA-binding proteins and the RNA dependence of published protein–protein interactions. (A) The fraction of proteins we identified as RNA-dependent binders that are known RBPs (defined as those that have domains known to bind RNA or have a molecular function of RNA binding in the Gene Ontology database). Known RNA-binding proteins are significantly enriched among the proteins interacting in an RNA-dependent manner with Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3 (for example, P-value of 2 × 10−35 for the union of all three data sets). (B) The percentage of proteins known to bind RNA in the set of 220 RNA-dependent binders in our combined data set, compared with the top 220 proteins from the protein array data from two previously published attempts to identify proteome-wide RNA–protein interactions. All had significant enrichment of known RBPs, but the enrichment seen with the set of proteins identified by our method was much greater (hypergeometric P-values 2 × 10−35, 2 × 10−4, and 2 × 10−5 for this study, Scherrer et al. 2010, and Tsvetanova et al. 2010, respectively). (C) A barplot showing the RNA dependence of published high-confidence protein–protein interactions and also the number of novel interactions (RNA dependent) we observed with Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3.

The experiments described used a buffer containing EDTA, and we next performed the Pab1 IP experiment in a buffer containing magnesium. This led to a highly significant enrichment of known RNA-binding proteins composed almost entirely of ribosomal proteins and proteins involved in the initiation, elongation, and termination of translation (Supplemental Table S6). The majority of these proteins were not observed as RNA-dependent binders in experiments done in the presence of EDTA, in which ribosomes are no longer assembled on mRNA. These data provide a unique perspective into Pab1-containing RNA–protein complexes involved in translation.

The high frequency of known RBPs among the 220 RDBs identified in this study contrasts with a frequency of ∼20% known RBPs among the 220 highest-ranking hits identified in two previous studies using protein microarrays (including one method developed by members of our group) (Scherrer et al. 2010; Tsvetanova et al. 2010). Despite this difference, our 220 RDBs are significantly enriched in the protein microarray data from Tsvetanova et al. (2010) and also from Scherrer et al. (2010) (Supplemental Fig. S5; Wilcoxon P-values 0.005 and 0.009, respectively). However, there was no Spearman rank correlation between our data and that from either protein array data set. These results suggest that our method both corroborates and extends previous work identifying RNA-interacting proteins.

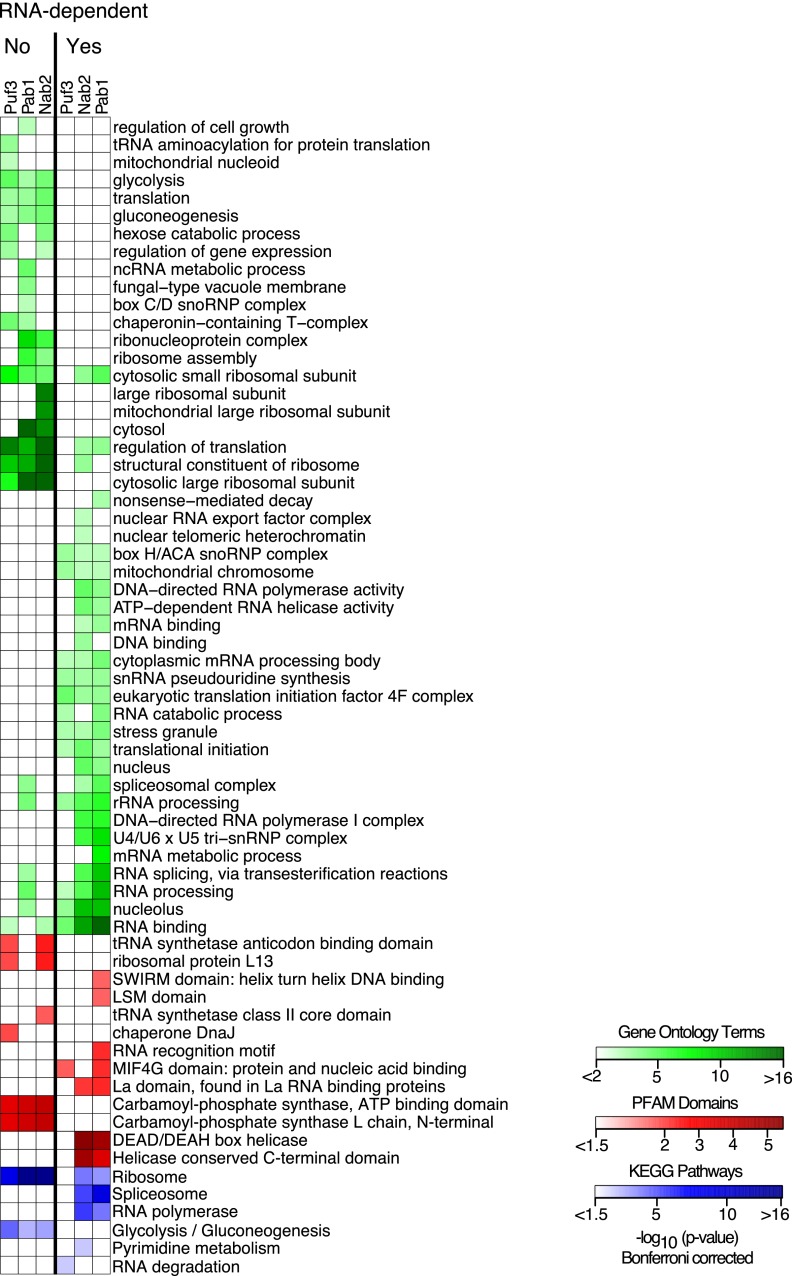

We analyzed the enrichment of Gene Ontology (GO) terms, protein domains from the protein families database (PFAM), and biological pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) relative to all the proteins that could be detected from an analysis of a yeast whole-cell lysate (Fig. 4). Our data clearly partition the proteins into groups with strong ties to RNA-dependent or independent binding as evidenced by the enrichment of GO terms, PFAM domains, and KEGG pathways. The proteins we classified as having RNA-dependent interactions with Pab1, Nab2, or Puf3 were enriched for Gene Ontology (GO) terms referring to RNA-related biological processes and molecular functions, such as RNA binding, transcription, splicing, translation, and decay (Fig. 4). Importantly, the majority of these RNA-related GO terms were not similarly enriched among the proteins falling below the threshold we set for classification as RNA-dependent binders, again demonstrating that our method had successfully separated these proteins based on their ability to bind RNA. The proteins with RNA-dependent interactions were also enriched for several protein domains known to bind RNA, DNA, or nucleic acid in general, such as SWIRM nucleic acid–binding domains, LSM RNA-binding domains, RNA recognition motif domains, MIF4G protein- and nucleic acid–binding domains, La RNA–binding domains, and DEAD/DEAH-box helicase domains. None of these domains were enriched among the proteins falling below the cutoff for RNA-dependent interactions.

Figure 4.

Differential enrichment of Gene Ontology terms, PFAM domains, and KEGG pathways. A heatmap showing the enrichment of Gene Ontology terms, PFAM domains, and KEGG pathways among the proteins we identified as RNA-dependent binders and those that were not (labeled “Yes” and “No,” respectively). Enrichment of Gene Ontology terms, PFAM domains, and KEGG pathways is depicted in green, red, and blue, respectively. Colors correspond to the negative log base 10 of the hypergeometric P-values. The columns are enrichment seen among proteins interacting in an RNA-dependent manner with Puf3, Pab1, or Nab2.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment provides further insight into the functional roles of Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3. Specifically, the proteins that interact in an RNA-dependent manner with Pab1 and Nab2, but not those that interact with Puf3, were enriched for the KEGG pathways “Spliceosome” and “RNA polymerase” (Fig. 4). Nab2 and Pab1 have been implicated in mRNA end processing and polyadenylation, and they are generally believed to bind to their mRNA targets at this stage (Hector et al. 2002; Brune et al. 2005; Dunn et al. 2005; Iglesias and Stutz 2008; Tutucci and Stutz 2011). However, our evidence that they associate simultaneously with RNA polymerase and spliceosomes potentially indicates that these proteins may, in fact, bind earlier, during transcription. This enrichment was not seen among the RNA-dependent interactions with Puf3, suggesting that Puf3 binds later in the life of its mRNA targets. DNA-binding and transcription-related GO terms were also enriched among proteins that we found to have RNA-dependent interactions with Nab2 or Pab1, but not with Puf3—further evidence that Pab1 and Nab2 bind cotranscriptionally to nascent transcripts, but that Puf3 does not. Conversely, the KEGG RNA degradation pathway annotation was specifically enriched among the proteins interacting in an RNA-dependent manner with Puf3, consistent with the known role of Puf3 in promoting the degradation of its mRNA targets (Gerber et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2010).

Identification and validation of novel RNA-binding proteins

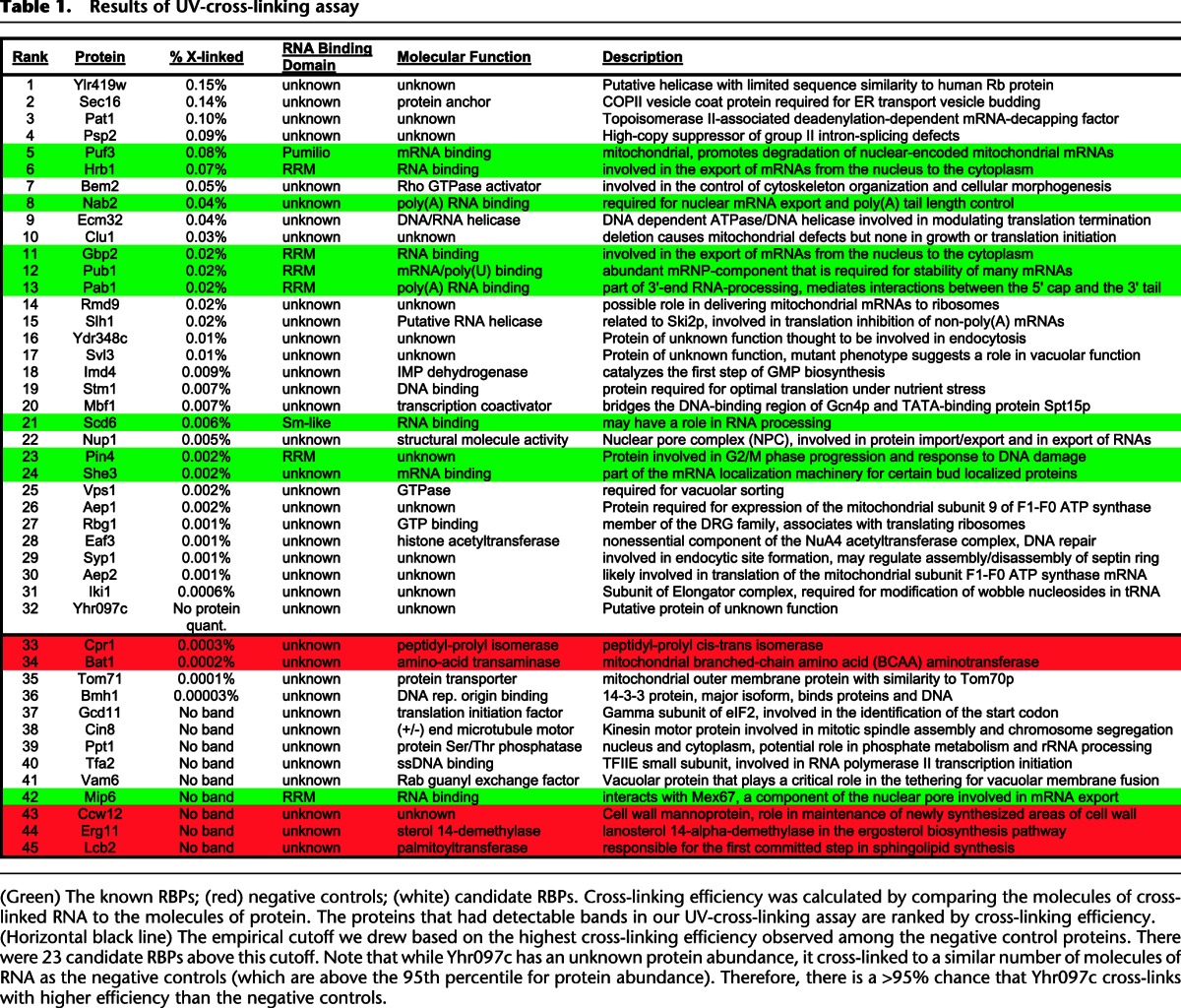

The strong enrichment of known RNA-binding proteins that we observed among the 220 RNA-dependent binders (Fig. 3A) makes it likely that most of the 114 proteins in this group that are not currently annotated as RNA-binding proteins also bind RNA (Supplemental Fig. S6; Supplemental Table S5). To test whether these candidate RBPs bind directly to RNA, we used a method based in part on previous approaches (Greenberg 1979, 1980; Ule et al. 2005) that combines UV cross-linking, affinity purification, RNase treatment, polynucleotide kinase labeling with 32P, and denaturing SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (Supplemental Fig. S7). This method allows us to identify whether a candidate RBP makes direct contact with RNA (within 1 Å) (Pramanik and Bewley 1996; Ule et al. 2005). We tested 25 of the 76 candidate RBPs that were not reported to interact physically with known RBPs as well as five of the 38 candidates that have been reported to interact physically with known RNA-binding proteins. We also included 10 known RBPs as positive controls and five putative negative control proteins that were selected from among highly abundant proteins (95th percentile for abundance) for which we had no evidence to suggest that they bind RNA.

We quantified any detectable radioactive bands on our denaturing SDS-PAGE gels corresponding to the candidate RBPs and analyzed the relationship between the molecules of cross-linked RNA that were detected and an estimate of the molecules of each protein present (based on data from the Saccharomyces Genome Database [Ghaemmaghami et al. 2003; de Godoy et al. 2008; Cherry et al. 2012] and described in Methods). This revealed a correlation between protein abundance and molecules of RNA cross-linked (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.8 for known RBPs and 0.7 for all proteins), although there was a large variation in the amount of RNA that could be cross-linked for proteins at the same abundance level. For example, the known RBPs She3 and Puf3 have similar protein abundance (∼1000 and ∼850 molecules per cell, respectively), but Puf3 cross-links to ∼40-fold more molecules of RNA than She3. For more discussion of these differences in cross-linking efficiency, see the Supplemental Material. The two negative controls with detectable bands cross-linked to far fewer molecules of RNA than would be expected based on their high abundance, placing them in the bottom 10% of cross-linking efficiency out of all 45 tested proteins (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of UV-cross-linking assay

We used the cross-linking efficiency of the negative controls to set a threshold for validated RNA-binding proteins. There were 23 candidate RBPs above this threshold (out of the 25 with detectable cross-linking); their cross-linking efficiencies ranged from ∼0.1 to 0.001%. Remarkably, the four proteins that cross-linked with the highest efficiency among all 45 proteins we tested, including 10 known RBPs, were newly identified candidate RBPs (Table 1). We also found that whether or not a candidate RBP had been reported to interact physically with a known RBP was not a strong predictor of whether it could be cross-linked directly to RNA in our assay (4/5 for the potential indirect binders and 19/25 for the others). Overall, ∼77% (23 of 30) of the candidate RBPs cross-linked to RNA with higher efficiency than the negative controls, providing strong evidence that the majority of the novel candidate RBPs discovered in this study may bind directly to RNA.

None of these 23 validated novel RBPs have any known RNA-binding domains. While many of these proteins have unidentified molecular functions, those with known roles and pathways are remarkably diverse, including a vesicle trafficking protein (Sec16), a transcription factor (Mbf1), a DNA-binding protein (Stm1), two helicases (Ecm32, Slh1), a metabolic enzyme (Imd4), a GTPase (Vps1), and a histone acetyltransferase (Eaf3) (Table 1). The unsuspected RNA-binding activity of dozens of proteins found here underscores the need for unbiased methods for discovering novel RNA-binding proteins.

The transcriptional coactivator Mbf1 cross-links to RNA in a region distinct from its DNA-binding domain.

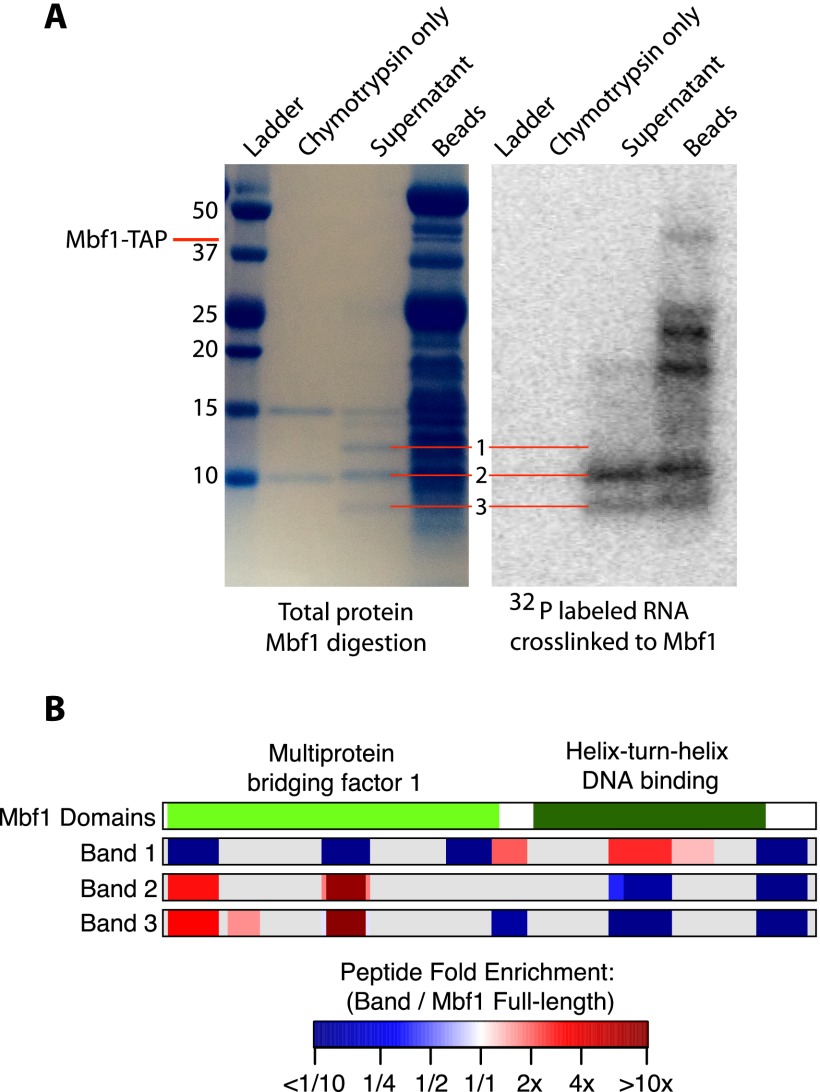

Since none of these validated RNA-binding proteins have homology with protein domains known to bind RNA, we sought to identify the region of each protein that cross-links to RNA. We performed a partial protease digest of purified proteins to reveal structured regions cross-linked to radioactively labeled, exhaustively digested RNA fragments. We then analyzed the digestion products by SDS-PAGE to find distinct bands representing ordered domains of the protein (Fontana et al. 2012). Next, we measured the radioactivity of each of these bands to determine if they were cross-linked to RNA. Protease digestion of Mbf1 produced fragments that could be resolved as three distinct bands by SDS-PAGE, corresponding to putative stable digestion products (Fig. 5A). Bands 2 and 3 had strong signals from the cross-linked, radiolabeled RNA, while band 1 did not (Fig. 5A). We excised these three bands (and undigested Mbf1) from the gel and analyzed them by mass spectrometry, comparing the enrichment of each peptide relative to undigested Mbf1 for each band after normalization (Fig. 5B). This identified a region at the N terminus in the multiprotein bridging factor (MBF) domain that was ∼10-fold enriched in bands 2 and 3 but not band 1 (Fig. 5B). Conversely, band 1, which did not cross-link to RNA, displayed approximately twofold enrichment for peptides derived from the helix–turn–helix DNA-binding domain. These results imply that the RNA-binding domain of Mbf1 is distinct from its DNA-binding domain, suggesting that Mbf1 could potentially bind simultaneously to DNA and RNA.

Figure 5.

Mapping the RNA-binding domain of Mbf1. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of protein fragments resulting from partial digestion of Mbf1 with the protease chymotrypsin. The lanes from left to right contain the ladder, chymotrypsin only, the supernatant of protein fragments liberated by chymotrypsin digestion of Mbf1, and the protein fragments remaining on the beads. A total protein stain is shown on the left, and the radioactive image of the same gel is shown on the right. Gel images were scaled and aligned to facilitate direct comparison of the visible bands. The radioactive image shows a signal from 32P-labeled RNA fragments cross-linked to Mbf1. (B) A diagram showing the domains of Mbf1 and the position and enrichment relative to full-length Mbf1 for all the peptides that were detected in each sample. The fold enrichment of the normalized intensity of each peptide relative to undigested Mbf1 for each of the three bands is represented by a color gradient ranging from dark blue for less than one-tenth fold enriched, to white for no enrichment, to dark red for greater than 10-fold enriched. (Gray) Areas of the protein for which no peptides were detected.

A large fraction of the RNA-dependent binders that we identified are annotated as DNA-binding proteins, including several transcription factors such as Mbf1 (Supplemental Fig. S6). We speculate that the RNA-dependent binders that also bind DNA may operate to connect the post-transcriptional regulatory network to the transcriptional regulatory network, by first binding DNA to regulate transcription and subsequently binding to the nascent RNA to affect its stability or translation in the cytoplasm. Indeed, recent reports provide evidence that transcriptional regulation can affect post-transcriptional regulation in yeast (Harel-Sharvit et al. 2010; Bregman et al. 2011; Choder 2011). In addition, a connection between the transcription and the processing of RNA has long been known to exist (Cramer et al. 1997; McCracken et al. 1997).

Analysis of the proteins that bind to RNAs concurrently with Nab2 or Puf3 expands on the existing models of Nab2 and Puf3 function in post-transcriptional regulation

While RNA immunoprecipitation methods (RIP-chip, CLIP-seq, and related) can identify specific interactions between RNAs and RNA-binding proteins, they cannot identify whether the multiple proteins that interact with a given RNA bind concurrently, sequentially, or in mutually exclusive cellular locations. In contrast, our RNA-dependent interaction data enable us to directly identify pairs of proteins that bind concurrently to one or more RNAs in a cell. Together with other information about these RBPs, this can provide clues to its function and when and where in the cell it binds.

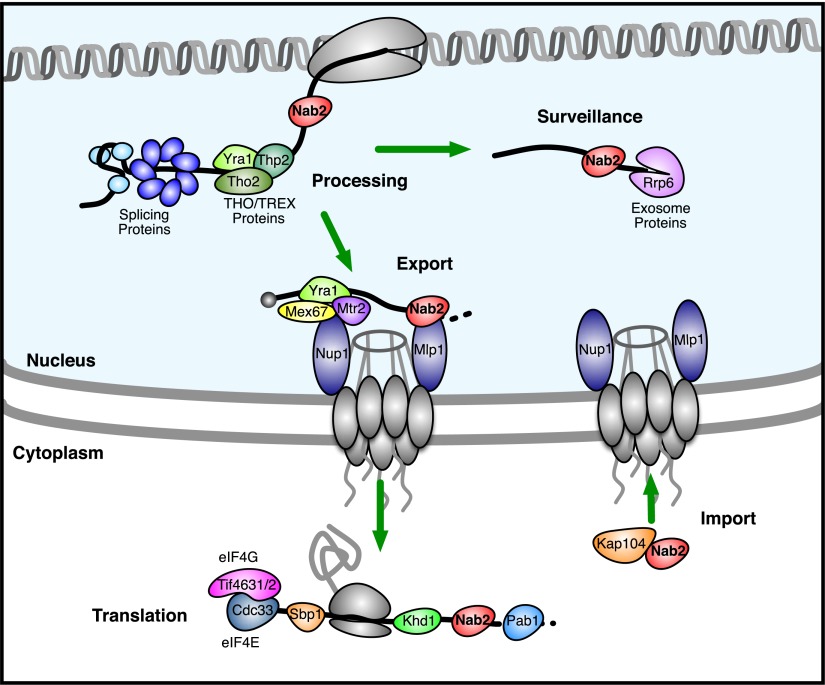

Nab2 is involved in the end processing, polyadenylation, and export of poly(A) mRNA from the nucleus (Green et al. 2002; Hector et al. 2002; Fasken et al. 2008; Iglesias and Stutz 2008; Tutucci and Stutz 2011). It is generally believed that Nab2 binds to mRNAs during their end cleavage and polyadenylation and is removed immediately following their nuclear export (Lee and Aitchison 1999; Tran et al. 2007). Previous work also revealed that the mRNAs bound by Nab2 tend to encode nuclear-localized proteins involved in transcription and splicing (Guisbert et al. 2005; Hogan et al. 2008). We confirmed several known RNA-dependent interactions with Nab2 in our data and uncovered novel RNA-dependent interactions that were consistent with the known role of Nab2 in end processing and mRNA export, such as THO/TREX complex components, Mex67, Mtr2, and Nup1 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

A revised model for Nab2 activity. This diagram depicts a subset of the proteins that we found to interact with Nab2 in an RNA-dependent or independent manner. We used our observations to expand on previous models of Nab2 function. Proteins separated by a black line (the RNA) with Nab2 had RNA-dependent interactions. When limited to well-studied proteins known to bind RNA, this RNA-dependent interaction data suggest that these RBPs bind to the same RNAs at the same time as Nab2. Proteins were placed in this diagram according to their known roles in RNA processing and regulation. Note that the RNA-independent interactions we detected between Nab2 and Mlp1 and Kap104 are also shown because of their known roles in Nab2 function.

Using our data to extend the existing model of Nab2 function, we looked for novel RNA-dependent interactions between Nab2 and other well-studied RNA-binding proteins involved in processes other than mRNA polyadenylation and export (Fig. 6). We detected novel RNA-dependent interactions between Nab2 and several protein components of the splicing apparatus (Smb1, Smd1, Smd2, Smd3, Smx3, Cef1, Luc7, Msl5, Prp19, Prp22, Prp39, and Yhc1) (Fig. 6). We also found RNA-dependent interactions with proteins involved in transcription or the regulation of transcription (Tfa2, Arp9, Gat1, Mbf1, Met28, and the RNA polymerase II central core component Rpb2) (Fig. 6). These interactions appear to be specific to Nab2, because most are not seen with Pab1 (5/5 Sm proteins, 1/7 other splicing, 1/6 transcription related) or Puf3 (0 out of 18). Nab2's unexpected RNA-dependent interactions with these proteins involved in splicing and transcription suggest that in some cases Nab2 may bind earlier than generally believed, perhaps cotranscriptionally. We also find a novel RNA-dependent interaction between Nab2 and the nuclear exosome core component Rrp6, suggesting that Nab2 remains associated with some mRNAs when they are targeted for surveillance or degradation. Finally, while in vitro experiments and genetic interactions have led to the model that Nab2 is removed from its mRNA targets by helicases anchored on the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complex (Tran et al. 2007), we discovered novel RNA-dependent interactions between Nab2 and proteins involved in translation and the repression of translation, such as Tif4631, Tif4632, Cdc33, Sbp1, Khd1, and Pab1. This suggests that in some cases Nab2 remains bound to its targets after mRNA export (Fig. 6). These results illustrate how analyzing the well-studied RBPs that bind concurrently with Nab2 can expand the model of Nab2 function and refine our view of when in the life of its mRNA targets it binds.

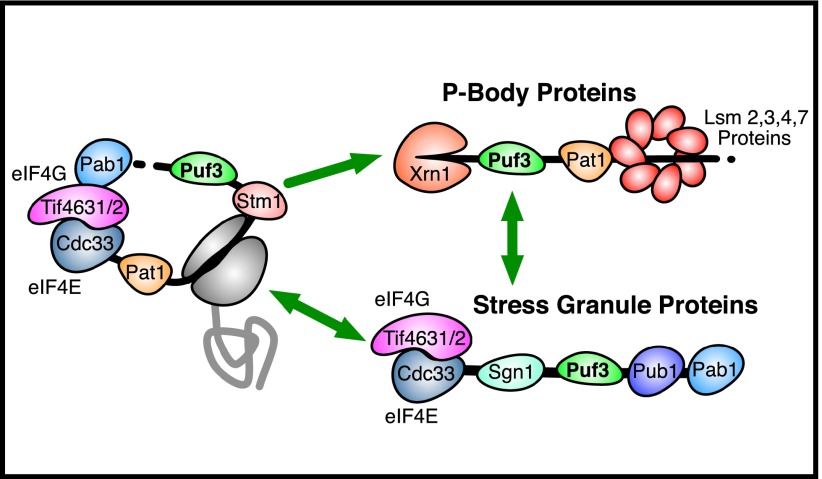

Applying a similar approach to Puf3 identifies several novel RNA-dependent interactions that extend and refine the known role of Puf3 in repressing the expression of its mRNA targets. Puf3 promotes the decay and localization of its mRNA targets (Gerber et al. 2004; Saint-Georges et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2010; Quenault et al. 2011). It also physically interacts with decay proteins such as the major cytoplasmic deadenylase complex Ccr4–Not (in an RNA-independent manner) (Lee et al. 2010). Our method has revealed that in addition to its role in promoting decay and localization, Puf3 binds to mRNAs concurrently with proteins involved in translation and translational repression, namely, Tif4631, Tif4632, Cdc33, Pat1, and Stm1 (Fig. 7). We have also discovered novel RNA-dependent interactions between Puf3 and the P-body and RNA decay–related proteins, Xrn1 and the Lsm ring complex (Fig. 7). Finally, we learned that Puf3 can bind to mRNAs concurrently with the stress granule proteins Sgn1 and Pub1 (Fig. 7). Puf3 can promote the deadenylation and decay of its mRNA targets independent of Ccr4 (Lee et al. 2010). It has been hypothesized to recruit an as-yet-unknown factor or factors to promote the rearrangement of the mRNP structure from a pro-translation/stability state into an anti-translation/decay state (Lee et al. 2010). Given that Stm1 and the Pat1/Lsm-ring complex are involved in the repression of translation and promote mRNA decapping/decay (Marnef and Standart 2010; Balagopal and Parker 2011), we speculate that these proteins may be the undiscovered factors that Puf3 recruits to its target mRNAs to promote their degradation. Going beyond the known role of Puf3, we found novel RNA-dependent interactions between Puf3 and proteins involved in repressing translation, suggesting that Puf3 may also repress the expression of its mRNA targets at the translational level. These vignettes illustrate how our data provide a unique perspective into the makeup of the RNA–protein complexes in which an RBP of interest is found and highlight the value of this technique for the study of post-transcriptional regulation.

Figure 7.

Insights from RNA-dependent interactions with Puf3. This diagram depicts a subset of the proteins that we found to interact with Puf3 in an RNA-dependent manner. Proteins separated by a black line (the RNA) with Puf3 had RNA-dependent interactions. When limited to well-studied proteins known to bind RNA, these RNA-dependent interaction data suggest that these RBPs bind to the same RNAs at the same time as Puf3. Proteins were placed in this diagram according to their known roles in RNA regulation.

Discussion

A growing body of evidence suggests that post-transcriptional regulation mediated by RBPs is a widespread phenomenon, but how this happens largely remains to be discovered. It is clear from the many published examples of regulatory RNA-binding activity in unexpected proteins that we need methods to enable the unbiased discovery of novel RNA–protein interactions. A prevailing model of post-transcriptional regulation is that the specific complement of RBPs bound to a given mRNA specifies its post-transcriptional fate—yet nearly all existing data are limited to defining pairwise interactions between a single RBP and a single mRNA species, potentially missing vital information about this aspect of post-transcriptional regulation.

Here we developed a method that characterizes RNA–protein interactions from a different perspective. It combines quantitative mass spectrometry with RNase treatment of affinity-purified RNA–protein complexes assembled in vivo. We interrogated the constituents of RNA–protein complexes containing the known RNA-binding proteins Pab1, Nab2, or Puf3, respectively, providing a new perspective on the role of Nab2 and Puf3 in post-transcriptional regulation.

Our data revealed a large and diverse group of previously unrecognized RNA-binding proteins and showed that the majority of previously reported protein–protein interactions involving Pab1 or Nab2 that we could detect are, in fact, RNA dependent. We extrapolate that other reported protein–protein interactions, especially those involving abundant RNA-binding proteins, may likewise reflect concurrent binding to RNA rather than direct interactions. We identified several annotated DNA-binding proteins as RNA-dependent binders. These proteins may both bind DNA to regulate transcription and subsequently bind to the nascent RNA and regulate its stability or translation in the cytoplasm, as a means of coordinating the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of a given gene, a model that has been suggested by previous work (Cramer et al. 1997; McCracken et al. 1997; Harel-Sharvit et al. 2010; Bregman et al. 2011). In contrast to previous applications of mass spectrometry to the identification of RNA–protein interactions, our approach appears to be largely unbiased by protein abundance. Strikingly, ∼50% (114/220) of the RNA-dependent binders we identified were already known to be RBPs (enrichment P-value 2 × 10−35), which is a considerable improvement over previous approaches.

The RBP Nab2 is involved in the end processing, polyadenylation, and export of poly(A) mRNA from the nucleus; we see both known and novel RNA-dependent interactions with Nab2 that are consistent with the existing model (Hector et al. 2002; Tran et al. 2007; Fasken et al. 2008; Iglesias and Stutz 2008; Tutucci and Stutz 2011). However, our data provide new insight into the temporal program of Nab2 binding based on evidence for concurrent binding with RBPs involved in transcription, splicing, and translation. From its RNA-dependent interaction partners, we infer a model in which Nab2 binds cotranscriptionally and remains bound during splicing and end processing. Nab2 also appears to remain bound to mRNAs that fail splicing or are otherwise targeted for surveillance/degradation by the nuclear exosome. For mRNAs that pass nuclear quality control, Nab2 interacts with the nuclear pore to promote their export. After export into the cytoplasm, Nab2 remains bound to its mRNA targets as they are bound by cytoplasmic translation regulatory proteins and perhaps until they initiate the first round of translation. An intriguing possibility is that some of these proteins typically involved in regulating translation in the cytoplasm may be loaded onto mRNAs before or during export, while Nab2 is still bound.

The RBP Puf3 is known to promote the decay of its mRNA targets (Gerber et al. 2004; Saint-Georges et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2010; Quenault et al. 2011). We identified novel RNA-dependent interactions consistent with this role. Proteins that bind RNAs concurrently with Puf3 include candidates (Stm1 and the Pat1/Lsm1 ring complex) for hypothetical factors recruited by Puf3 to promote the rearrangement of its mRNP structure from a pro-translation/stability state into an anti-translation/decay state (Lee et al. 2010). We found that Puf3 binds to mRNAs at the same time as proteins that are involved in translational repression (Pat1, Stm1), found in P-bodies (Xrn1, Lsm ring), or found in stress granules (Sgn1, Pub1), suggesting that Puf3 may repress its mRNA targets at the translational level as well. As a part of this model, these proteins may briefly physically interact with Puf3 as they are recruited to a Puf3-bound mRNA, but we would not necessarily expect to detect this interaction in our assay if at steady state a substantial fraction of these proteins remain bound to RNA but not Puf3.

We identified as candidate RBPs 106 proteins that were not previously known to bind RNA. Of the 30 candidates we tested, 23 (77%) bound directly to RNA in an independent assay. None of these 23 novel RNA-binding proteins have known RNA-binding domains, and many have unknown molecular functions. The known functions of the novel RBPs were diverse, including a vesicle trafficking protein (Sec16), a transcriptional coactivator (Mbf1), a regulator of translational elongation (Stm1), two helicases (Ecm32 and Slh1), a metabolic enzyme (Imd4), a dynamin-like GTPase (Vps1), and a histone acetyltransferase (Eaf3). We speculate that in some cases these unexpected RNA–protein interactions involving proteins with already established biological functions that are apparently unrelated to RNA binding might have evolved to facilitate mRNA localization. Specifically, RNAs may have evolved structured elements to bind to specific proteins with distinct localization patterns (such as Imd4) to “hitch a ride” to, or hold their position in, a particular part of the cell. Overall, our high success rate for validating the RNA-binding activity of the proteins identified as RDBs suggests that many of the 76 candidates we have yet to test may also bind directly to RNA (Supplemental Table S5).

Existing methods that use microarrays or sequencing to identify the RNA targets of specific RBPs can identify sets of RBPs that interact with common RNA targets. The method we describe here makes it possible to determine which of those interactions are concurrent. This is a crucial distinction, because while each RNA may be bound by several different RBPs over the course of its lifetime (Hogan et al. 2008), many of those RBPs may bind at different times or places within the cell. When applied to a specific RNA-binding protein, the identity of other concurrently associated RBPs can provide clues to its position in the temporal sequence of protein–RNA interactions and the subcellular location in which they occur. This approach could thus be broadly applicable to mapping relationships and connections in the RNA–protein network that affects the fate of each mRNA. A similar approach could also be used to identify proteins that bind to DNA concurrently.

Methods

RNA-dependent protein purification

We grew TAP-tagged yeast strains (Pab1-TAP, Nab2-TAP, and Puf3-TAP) auxotrophic for lysine to mid-log phase in media with or without heavy labeled L-lysine. We lysed the cells and purified the RNA-binding proteins essentially as described previously (Tsvetanova et al. 2010), except that we split the beads equally after the initial washes and performed the subsequent three washes in buffer with or without RNase (in excess). Note: For the Pab1 Mg2+ purification, the wash buffers contained 1.8 mM MgCl2, but for all other purifications, the washes were done with buffer containing 10 mM EDTA.. Finally, we boiled the beads in Laemmli sample buffer and proceeded to analysis by mass spectrometry. A detailed protocol is available in the Supplemental Material.

Quantitative mass spectrometry

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and each lane was sliced into eight fractions, which were further minced. The minced gel pieces were then destained, minced, alkylated, and incubated overnight with LysC. The resulting peptides were then extracted from the gel, separated by capillary chromatography, and analyzed by an LTQ-Orbitrap XL. The MS data were processed using the MaxQuant software suite (version 1.2.0.18) (Cox and Mann 2008) and a yeast protein database (6717 entries and its reverse complement). For the search, oxidation on methionine and protein N-terminal acetylation were set as variable modifications. Protease cleavage specificity was set to LysC. False discovery rates at the peptide and protein levels were set to 0.01, and only proteins with at least two quantitation events were considered for the subsequent bioinformatic analysis. A detailed protocol is available in the Supplemental Material.

Analysis of mass spectrometry data

The forward experiment (heavy labeled without RNase over unlabeled with RNase) and the reverse experiment (heavy labeled with RNase over unlabeled without RNase) were analyzed by mass spectrometry separately and treated as replicates (except with inverted heavy-to-light ratios). To generate a high-confidence data set, we filtered the mass spectrometry results for proteins for which we detected two peptides in both the forward and the reverse experiment (that map to only one protein). To generate a background set of all proteins that had the opportunity to be detected in our assays, we used mass spectrometry data from an analysis of all proteins detected from a yeast whole-cell lysate and filtered for two peptides in at least two replicates. This background set (Supplemental Table S7) was used to calculate enrichment of known RNA-binding proteins as well as Gene Ontology terms, KEGG pathways, and PFAM domains. We then inverted the heavy-to-light ratios for the reverse experiment, normalized the forward and reverse samples so that the ratio for the TAP-tagged protein was 1, and then averaged the forward and reverse values. We then took the log base 2 of these heavy-to-light ratios and worked with the data in this format from this point on [referred to as log2(−/+) RNase ratios or RNA-dependence values].

To establish a conservative cutoff for the classification of proteins into RNA-dependent binders and protein binders based on their RNA-dependence values, we modeled the distributions of RNA-dependence values for proteins with RNA-independent interactions with Pab1, Nab2, and Puf3. To do this, we made two assumptions: first, that after normalization, any RNA-dependence values less than zero have a true value of zero and the observed variation from zero is due to noise; and, second, that this noise is symmetric about zero. Using these two assumptions, we took the RNA-dependence values less than zero (excluding the most negative 1% as extreme outliers) and combined them with their absolute values to form a null distribution symmetric about zero (Supplemental Fig. S3). We used this null distribution to determine an empirical FDR cutoff of 10% for the classification of RDBs (Supplemental Fig. S3). To evaluate this cutoff independently, we plotted the frequency of annotated RBPs in a sliding window versus the RNA-dependence values (Supplemental Fig. S4). This analysis revealed that the frequency of annotated RBPs was well above the median frequency for all proteins that could be detected from a yeast whole-cell lysate as well as the median frequency for all proteins detected in each purification experiment (Supplemental Fig. S4). Note that ribosomal proteins were excluded from the analysis for Supplemental Figures S1 and S4 because they are common mass spectrometry contaminants, and they also often have an annotated molecular function of RNA binding. This serves as independent validation of the cutoff we made for classifying proteins as RDBs.

We calculated the enrichment of Gene Ontology terms, PFAM domains, and KEGG pathways using the GOStats package in R (Falcon and Gentleman 2007). We corrected the resulting P-values for multiple hypothesis testing using the Bonferroni correction. We made the RNA–protein interaction network diagram with the program Cytoscape (Smoot et al. 2011). We made the diagrams depicting the RNA-dependent binding interactions as well as the method overview with the program OmniGraffle by the Omni Group. The protein abundance data we used were previously published (Ghaemmaghami et al. 2003). The set of high-confidence protein–protein interactions we used was from Collins et al. (2007).

UV cross-linking assay

To test whether our candidate RNA-binding proteins cross-link directly to RNA by UV irradiation, we used a method based on work by Greenberg (1979, 1980) and Ule et al. (2005). First, we cross-linked RNA to protein in vivo by UV irradiation and purified the TAP-tagged candidate RBPs under denaturing conditions. Then, we subjected each sample to limited digestion by MNase and then subjected half to further, exhaustive digestion by RNase. We next labeled the RNA fragments by polynucleotide kinase treatment and ran the samples on a denaturing SDS-PAGE gel. We looked specifically for the presence of a PNK-labeled band that was RNase sensitive and of corresponding size to the protein of interest. We also included 10 known RBPs as positive controls and five putative negative-control proteins that were selected from among highly abundant proteins (95th percentile for abundance) for which we had no evidence to suggest that they bind RNA. Molecules of cross-linked RNA were quantified by comparing the intensity of the radioactive band with a standard curve, and molecules of protein were estimated based on published protein abundance data and the number of cells used, the typical lysis efficiency, and the typical purification efficiency. A detailed protocol is available in the Supplemental Material.

Identification of RNA-binding protein domains

We prepared the protein samples exactly as they were for the UV-cross-linking assay described above, except that we scaled up everything 4×. After we subjected the samples to exhaustive RNase digestion and radioactive labeling, we digested them with chymotrypsin, trypsin, or elastase ranging in concentration from 0.1 mg/mL to 0.0001 mg/mL (10× dilutions). We analyzed the supernatants containing protein fragments liberated by protease digestion by SDS-PAGE, visualizing both total protein and radioactive signal in the same gel. We analyzed the distinct bands by mass spectrometry, to map them to a specific position in the full-length protein. This information, combined with our observation of which bands were radioactively labeled, allowed us to identify the regions of the protein that were cross-linked to RNA. A detailed protocol is available in the Supplemental Material.

Data access

Raw data are included as Supplemental Material with this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Alex Lovejoy and Dan Herschlag for comments on this manuscript. P.O.B., D.M.K., and G.J.H. are supported mainly by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health to P.O.B. (NIH RO1 CA77097). P.O.B. is an investigator for the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. D.M.K. was also partially supported by a National Science Foundation pre-doctoral fellowship. G.J.H. was also partially supported by a Burt and Deedee McMurtry Stanford Graduate Fellowship. Work in the Mann laboratory is supported by the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.153031.112.

Freely available online through the Genome Research Open Access option.

References

- Balagopal V, Parker R 2011. Stm1 modulates translation after 80S formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA 17: 835–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltz AG, Munschauer M, Schwanhausser B, Vasile A, Murakawa Y, Schueler M, Youngs N, Penfold-Brown D, Drew K, Milek M, et al. 2012. The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol Cell 46: 674–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E, Fromont-Racine M, Pictet R, Grange T 1993. Visualization of the interaction of a regulatory protein with RNA in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 90: 3496–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Martin R, Granneman S, Ruprecht M, Schleiff E, Tollervey D 2009. Prp43 bound at different sites on the pre-rRNA performs distinct functions in ribosome synthesis. Mol Cell 36: 583–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman A, Avraham-Kelbert M, Barkai O, Duek L, Guterman A, Choder M 2011. Promoter elements regulate cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Cell 147: 1473–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune C, Munchel SE, Fischer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Weis K 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein Pab1 shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and functions in mRNA export. RNA 11: 517–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butter F, Scheibe M, Morl M, Mann M 2009. Unbiased RNA–protein interaction screen by quantitative proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 10626–10631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey JL, Hentze MW, Koeller DM, Caughman SW, Rouault TA, Klausner RD, Harford JB 1988. Iron-responsive elements: Regulatory RNA sequences that control mRNA levels and translation. Science 240: 924–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A, Fischer B, Eichelbaum K, Horos R, Beckmann BM, Strein C, Davey NE, Humphreys DT, Preiss T, Steinmetz LM, et al. 2012. Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149: 1393–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry JM, Hong EL, Amundsen C, Balakrishnan R, Binkley G, Chan ET, Christie KR, Costanzo MC, Dwight SS, Engel SR, et al. 2012. Saccharomyces Genome Database: The genomics resource of budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D700–D705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choder M 2011. mRNA imprinting: Additional level in the regulation of gene expression. Cell Logist 1: 37–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SR, Kemmeren P, Zhao XC, Greenblatt JF, Spencer F, Holstege FC, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ 2007. Toward a comprehensive atlas of the physical interactome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics 6: 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M 2008. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 26: 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P, Pesce CG, Baralle FE, Kornblihtt AR 1997. Functional association between promoter structure and transcript alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 11456–11460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Godoy LM, Olsen JV, Cox J, Nielsen ML, Hubner NC, Frohlich F, Walther TC, Mann M 2008. Comprehensive mass-spectrometry-based proteome quantification of haploid versus diploid yeast. Nature 455: 1251–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn EF, Hammell CM, Hodge CA, Cole CN 2005. Yeast poly(A)-binding protein, Pab1, and PAN, a poly(A) nuclease complex recruited by Pab1, connect mRNA biogenesis to export. Genes Dev 19: 90–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon S, Gentleman R 2007. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics 23: 257–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasken MB, Stewart M, Corbett AH 2008. Functional significance of the interaction between the mRNA-binding protein, Nab2, and the nuclear pore-associated protein, Mlp1, in mRNA export. J Biol Chem 283: 27130–27143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, de Laureto PP, Spolaore B, Frare E 2012. Identifying disordered regions in proteins by limited proteolysis. Methods Mol Biol 896: 297–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Aloy P, Grandi P, Krause R, Boesche M, Marzioch M, Rau C, Jensen LJ, Bastuck S, Dumpelfeld B, et al. 2006. Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature 440: 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer F, Hentze MW 2004. Molecular mechanisms of translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 827–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2004. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol 2: e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS 2003. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425: 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman S, Kudla G, Petfalski E, Tollervey D 2009. Identification of protein binding sites on U3 snoRNA and pre-rRNA by UV cross-linking and high-throughput analysis of cDNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 9613–9618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman S, Petfalski E, Swiatkowska A, Tollervey D 2010. Cracking pre-40S ribosomal subunit structure by systematic analyses of RNA–protein cross-linking. EMBO J 29: 2026–2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Marfatia KA, Crafton EB, Zhang X, Cheng X, Corbett AH 2002. Nab2p is required for poly(A) RNA export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and is regulated by arginine methylation via Hmt1p. J Biol Chem 277: 7752–7760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JR 1979. Ultraviolet light-induced crosslinking of mRNA to proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 6: 715–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JR 1980. Proteins crosslinked to messenger RNA by irradiating polyribosomes with ultraviolet light. Nucleic Acids Res 8: 5685–5701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guisbert K, Duncan K, Li H, Guthrie C 2005. Functional specificity of shuttling hnRNPs revealed by genome-wide analysis of their RNA binding profiles. RNA 11: 383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel-Sharvit L, Eldad N, Haimovich G, Barkai O, Duek L, Choder M 2010. RNA polymerase II subunits link transcription and mRNA decay to translation. Cell 143: 552–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hector RE, Nykamp KR, Dheur S, Anderson JT, Non PJ, Urbinati CR, Wilson SM, Minvielle-Sebastia L, Swanson MS 2002. Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J 21: 1800–1810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Caughman SW, Rouault TA, Barriocanal JG, Dancis A, Harford JB, Klausner RD 1987a. Identification of the iron-responsive element for the translational regulation of human ferritin mRNA. Science 238: 1570–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Rouault TA, Caughman SW, Dancis A, Harford JB, Klausner RD 1987b. A cis-acting element is necessary and sufficient for translational regulation of human ferritin expression in response to iron. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 6730–6734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieronymus H, Silver PA 2003. Genome-wide analysis of RNA–protein interactions illustrates specificity of the mRNA export machinery. Nat Genet 33: 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DJ, Riordan DP, Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2008. Diverse RNA-binding proteins interact with functionally related sets of RNAs, suggesting an extensive regulatory system. PLoS Biol 6: e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner NC, Bird AW, Cox J, Splettstoesser B, Bandilla P, Poser I, Hyman A, Mann M 2010. Quantitative proteomics combined with BAC TransgeneOmics reveals in vivo protein interactions. J Cell Biol 189: 739–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias N, Stutz F 2008. Regulation of mRNP dynamics along the export pathway. FEBS Lett 582: 1987–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JM, Wanless AG, Seidel CW, Weiss EL 2009. Cbk1 regulation of the RNA-binding protein Ssd1 integrates cell fate with translational control. Curr Biol 19: 2114–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD 2007a. Biological clocks and the coordination theory of RNA operons and regulons. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 72: 157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD 2007b. RNA regulons: Coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet 8: 533–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, Zhong G, Guo X, Ignatchenko A, Li J, Pu S, Datta N, Tikuisis AP, et al. 2006. Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440: 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurischko C, Kim HK, Kuravi VK, Pratzka J, Luca FC 2011. The yeast Cbk1 kinase regulates mRNA localization via the mRNA-binding protein Ssd1. J Cell Biol 192: 583–598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Aitchison JD 1999. Kap104p-mediated nuclear import: Nuclear localization signals in mRNA-binding proteins and the role of Ran and RNA. J Biol Chem 274: 29031–29037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Ohn T, Chiang YC, Quigley G, Yao G, Liu Y, Denis CL 2010. PUF3 acceleration of deadenylation in vivo can operate independently of CCR4 activity, possibly involving effects on the PAB1–mRNP structure. J Mol Biol 399: 562–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibold EA, Munro HN 1988. Cytoplasmic protein binds in vitro to a highly conserved sequence in the 5′ untranslated region of ferritin heavy- and light-subunit mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci 85: 2171–2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann M 2006. Functional and quantitative proteomics using SILAC. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7: 952–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marnef A, Standart N 2010. Pat1 proteins: A life in translation, translation repression and mRNA decay. Biochem Soc Trans 38: 1602–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken S, Fong N, Yankulov K, Ballantyne S, Pan G, Greenblatt J, Patterson SD, Wickens M, Bentley DL 1997. The C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II couples mRNA processing to transcription. Nature 385: 357–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler G, Butter F, Mann M 2009. A SILAC-based DNA–protein interaction screen that identifies candidate binding proteins to functional DNA elements. Genome Res 19: 284–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Mittler G, Mann M 2004. Identifying and quantifying in vivo methylation sites by heavy methyl SILAC. Nat Methods 1: 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquin N, Menade M, Poirier G, Donato D, Drouet E, Chartrand P 2007. Local activation of yeast ASH1 mRNA translation through phosphorylation of Khd1p by the casein kinase Yck1p. Mol Cell 26: 795–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik SK, Bewley JD 1996. Post-transcriptional regulation of protein synthesis during alfalfa embryogenesis: Proteins associated with the cytoplasmic polysomal and non-polysomal mRNAs (messenger ribonucleoprotein complex). J Exp Bot 45: 1871–1879 [Google Scholar]

- Quenault T, Lithgow T, Traven A 2011. PUF proteins: Repression, activation and mRNA localization. Trends Cell Biol 21: 104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouault TA, Hentze MW, Haile DJ, Harford JB, Klausner RD 1989. The iron-responsive element binding protein: A method for the affinity purification of a regulatory RNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 5768–5772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Georges Y, Garcia M, Delaveau T, Jourdren L, Le Crom S, Lemoine S, Tanty V, Devaux F, Jacq C 2008. Yeast mitochondrial biogenesis: A role for the PUF RNA-binding protein Puf3p in mRNA localization. PLoS ONE 3: e2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe M, Butter F, Hafner M, Tuschl T, Mann M 2012. Quantitative mass spectrometry and PAR-CLIP to identify RNA–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 9897–9902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk L, Meinel DM, Strasser K, Gerber AP 2012. La-motif–dependent mRNA association with Slf1 promotes copper detoxification in yeast. RNA 18: 449–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer T, Mittal N, Janga SC, Gerber AP 2010. A screen for RNA-binding proteins in yeast indicates dual functions for many enzymes. PLoS ONE 5: e15499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer T, Femmer C, Schiess R, Aebersold R, Gerber AP 2011. Defining potentially conserved RNA regulons of homologous zinc-finger RNA-binding proteins. Genome Biol 12: R3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze WX, Mann M 2004. A novel proteomic screen for peptide–protein interactions. J Biol Chem 279: 10756–10764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T 2011. Cytoscape 2.8: New features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics 27: 431–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran EJ, Zhou Y, Corbett AH, Wente SR 2007. The DEAD-box protein Dbp5 controls mRNA export by triggering specific RNA:protein remodeling events. Mol Cell 28: 850–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Boulon S, Lam YW, Urcia R, Boisvert FM, Vandermoere F, Morrice NA, Swift S, Rothbauer U, Leonhardt H, et al. 2008. Identifying specific protein interaction partners using quantitative mass spectrometry and bead proteomes. J Cell Biol 183: 223–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvetanova NG, Klass DM, Salzman J, Brown PO 2010. Proteome-wide search reveals unexpected RNA-binding proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS ONE 5: e12671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutucci E, Stutz F 2011. Keeping mRNPs in check during assembly and nuclear export. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12: 377–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ule J, Jensen K, Mele A, Darnell RB 2005. CLIP: A method for identifying protein–RNA interaction sites in living cells. Methods 37: 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu CL, Storey JD, Tibshirani RJ, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2002. Precision and functional specificity in mRNA decay. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 5860–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf JJ, Dowell RD, Mahony S, Rabani M, Gifford DK, Fink GR 2010. Feed-forward regulation of a cell fate determinant by an RNA-binding protein generates asymmetry in yeast. Genetics 185: 513–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]