SUMMARY

ClpX, a AAA+ ring homohexamer, uses the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to power conformational changes that unfold and translocate target proteins into the ClpP peptidase for degradation. In multiple crystal structures, some ClpX subunits adopt C conformations, others adopt unloadable conformations, and each conformational class exhibits substantial variability. Using mutagenesis of individual subunits in covalently tethered hexamers together with new fluorescence methods to assay the conformations and nucleotide-binding properties of these subunits, we demonstrate that dynamic interconversion between loadable and unloadable conformations is required to couple ATP hydrolysis by ClpX to mechanical work ATP binding to different classes of subunits initially drives staged allosteric changes, which set the conformation of the ring to allow hydrolysis and linked mechanical steps. Subunit switching between loadable and unloadable conformations subsequently isomerizes or resets the configuration of the nucleotide-loaded ring and is required for mechanical function.

INTRODUCTION

In all branches of life, AAA+ molecular machines harness the energy of ATP binding and hydrolysis to degrade, disaggregate, and secrete proteins, to remodel macromolecular complexes, to transport nucleic acids, and to drive vectorial transport along microtubules (Hanson and Whiteheart, 2005). A central unsolved challenge in dissecting the mechanisms of these complicated CC machines is to determine how ATP interacts with different subunits and coordinates the conformational changes that ultimately power machine function. Although many different models for this orchestration are possible, most proposals in the literature depend upon multiple untested assumptions, and the paucity of methods to test specific models has limited understanding of these machines.

ClpXP is an ATP-dependent protease that consists of a self-compartmentalized c recognizes, unfolds, and translocates protein substrates into an internal ClpP chamber for degradation (for review, see Baker and Sauer, 2012). Insight into ClpX function has come from biochemistry, protein engineering, and biophysics. For example, translocation of a peptide degron through the axial pore of the ClpX ring drives substrate unfolding, and processive translocation can occur against substantial resisting forces (Martin et al., 2008a; 2008b; Aubin-Tam et al., 2011; Maillard et al., 2011). Although ClpX is a homohexamer, it is asymmetric, and nucleotides fail to bind some ClpX subunits and bind other subunits with different affinities (Hersch et al., 2005). A single active subunit in the hexameric ring is sufficient to power mechanical unfolding and translocation, yet subunit-subunit communication appears to be important for controlling and coupling ATP hydrolysis to function (Martin et al., 2005). Because processive ClpXP proteolysisof a single polypeptide can require hundreds of ATP-binding and hydrolysis events (Kenniston et al., 2003), understanding how these nucleotide transactions are coupled to mechanical work is a critical aspect of mechanism.

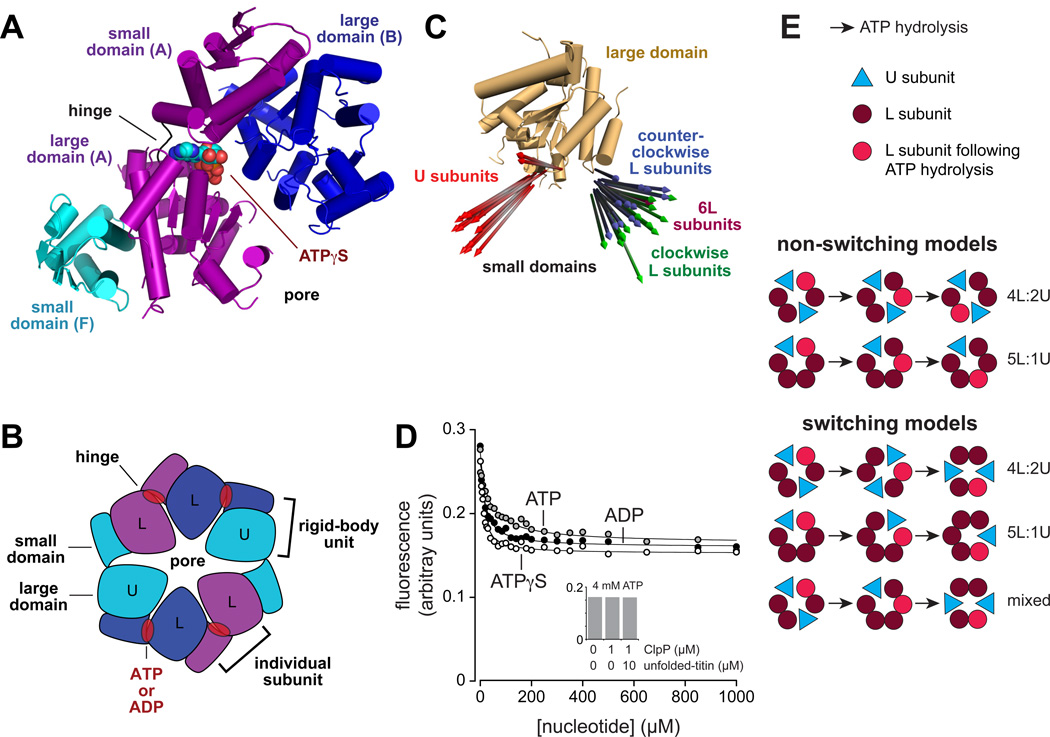

Crystal structures of the hexameric ClpX ring reveal two basic classes of subunits (Glynn et al., 2009). In four loadable (L) subunits, the orientation of the large and small AAA+ domains creates a binding cleft in which nucleotide can contact each domain, the intervening hinge, and a neighboring subunit (Fig. 1A). The exact structure and properties of these binding sites can differ depending upon the position in the hexamer and bound nucleotide. By contrast, these sites are destroyed in two unloadable (U) subunits by a hinge rotation that reorients the flanking domains. In the known hexamer structures, these subunits are arranged in an L/U/L/L/U/L pattern with approximate two-fold symmetry (Fig. 1B). For all subunits, the large AAA+ domain packs against the small AAA+ domain of the counterclockwise subunit in a conserved rigid-body fashion, and crosslinks across these interfaces are compatible with full ClpX function (Glynn et al., 2012). Thus, the functional ring can be viewed as six rigid-body units connected by hinges (Fig. 1B). Nucleotide-dependent changes in hinge geometry provide a potential way to couple ATP binding and hydrolysis in one subunit to conformational changes in neighboring subunits. However, direct evidence for such allosteric changes is lacking, and it is not known if L and U subunits interconvert and/or if a 4:2 ratio of L:U subunits is maintained during function.

Figure 1. ClpX structure.

(A) Nucleotide binds between the large and small AAA+ domains of a ClpX subunit and also contacts the neighboring large domain of the clockwise subunit. Each small domain and the large domain of the neighboring clockwise subunit form a rigid-body unit. The structure shown is from an ATPγS-bound hexamer (PDB code 4I81).

(B) In most crystal structures, the ClpX ring consists of four L subunits, which can bind nucleotide, and two U subunits, which cannot bind nucleotide. The ring consists of six rigid-body units. Changes in the conformations of the hinges that connect the large and small domain of each subunit are responsible for major conformational changes in the hexameric ring.

(C) After aligning the large AAA+ domains of each crystallographically independent subunit in eight crystal structures of E. coli ClpX hexamers (PDB codes 3HTE, 3HWS, 4I81, 4I4L, 4I34, 4I5O, 4I63, and 4I9K), the attached small domains were represented by a vector corresponding to a single α helix (residues 332–343). Although the vectors in U subunits are very different from those in L subunits, substantial variations within each subunit class are evident.

(D) Addition of ATP, ATPγS, or ADP reduced the fluorescence of a W-W-WTT pseudo hexamer (0.3 µM) to a level expected for a 5L:1U hexamer or a mixture of 4L:2U and 6L hexamers. The lines are fits to a hyperbolic equation with Kapp values of 15 ± 2 µM for ADP, 41 ± 6 µM for ATP, and 9 ± 1 µM for ATPγS. Inset: The same final fluorescence value was observed in the presence of 4 mM ATP with or without ClpP (1 µM) and a titinI27 substrate (10 µM) unfolded by reaction with fluorescein-5-maleimide.

(E) Models of ClpX function in which ClpX subunits retain their U or L identities (non-switching models) or subunits adopt U and L conformations at different points in the reaction cycle (switching models).

To address these questions, we have developed and applied assays for subunit-specific nucleotide binding (nCoMET) and conformational changes (cCoMET), where CoMET signifies coordinated metal energy transfer, a method that relies on short-distance quenching of afluorescent dye by a transition-metal ion (tmFRET; Taraska et al., 2009). Our results show that nucleotide binding to ClpX subunits with tight and weak affinities allosterically alters the conformations of neighboring subunits in a stepwise fashion, support a model in which L and U subunits in the ClpX ring dynamically interconvert during the functional cycle, and suggest that nucleotide binding stabilizes a ring with five L-like subunits, reminiscent of structures observed in the AAA+ rings of the E1 helicase and 26S proteasome (Enemark and Joshua-Tor, 2006; Lander et al., 2012). The operating principles and tools developed here should be broadly applicable to the study of other AAA+ machines and multimeric assemblies.

RESULTS

The N domain of ClpX is not required for machine function (Singh et al., 2001; Wojtyra et al., 2003) and was deleted in the variants used here. ClpX variants were typically expressed from genes encoding two, three, or six subunits connected by polypeptide tethers, as linking subunits in this way allows ClpP-mediated degradation of ssrA-tagged substrates, does not affect pseudo-hexamer formation, and permits mutations or fluorescent probes to be introduced into specific subunits (Martin et al., 2005).

New crystal structures

For crystallography, ClpXΔN variants were single-chain trimers or dimers. In addition, specific subunits were either wild-type (W), contained an E185Q (E) Walker-B mutation or R370K (R) sensor-2 mutation to eliminate ATP hydrolysis, or contained both ATPase mutations (ER). In previous structures with and without nucleotide, a covalently tethered E-E-ER ClpXΔN trimer crystallized as a pseudo hexamer with an L/U/L/L/U/L arrangement of subunits (Glynn et al.,2009). We obtained six new pseudo-hexamer structures. Most had the L/U/L/L/U/L pattern, including an E-E-ER trimer with bound ATPγS, E-R dimers, W-W-R trimers, W-W-W trimers, and W-W-W trimers with bound ADP (Table S1). Thus, the L/U/L/L/U/L arrangement is not a consequence of bound nucleotide, the number of covalent tethers, or the presence of specific mutations. However, one W-W-W structure revealed an L/L/L/L/L/L or 6L arrangement of subunits (Table S1; Fig. S1A).

We aligned the large domains of each subunit from the eight crystal structures and represented the small domains by vectors corresponding to one helix (Fig. 1C). As expected, there were two major categories, corresponding to L and U conformations, but substantial variations were evident in each class. For example, compared to single reference vectors, the average angular variability was 16 ± 7° (maximum 27°) among L subunits and 18 ± 13° (maximum 45°) among U subunits, highlighting the variability in the conformations of individual subunits that comprise the ClpX ring. This variability allowed us to model a plausible 5L:1U ring structure using subunits taken from the observed 4L:2U and 6L structures (Fig. S1A).

Evidence supporting 4L:2U and 5L:1U subunit arrangements

Contact between two rhodamine-family dyes, such as TAMRA, results in quenching that displays an all-or-none character (Zhou et al., 2011). To address which arrangements of ClpX subunits might be populated in solution, we produced a W-W-WTT trimer in which TT designates TAMRA dyes attached to K330C in the small domain and D76C in the large domain of the third subunit (the TAMRA-labeled protein was active in ATP hydrolysis and supported ClpP-mediated degradation; Fig. S1B). Modeling showed that the TAMRA dyes were close enough for contact quenching in L subunits but were >25 Å apart in U subunits. Compared to an unquenched control, we would therefore expect ~33% fluorescence for a population of 4L:2U hexamers, ~16% fluorescence for a population of 5L:1U hexamers, and no substantial fluorescence for a population of 6L hexamers. In the absence of nucleotide, the fluorescence of the W-W-WTT pseudo hexamer was ~28% of a control sample of the same protein denatured in 3 M urea, as expected for a predominant population of 4L:2U structures (Fig. 1D). Addition of saturating concentrations of different nucleotides resulted in a decrease to ~16% of the unquenched control, consistent with a 5L:1U arrangement. These results are also consistent with a roughly equal mixture of 4L:2U and 6L hexamers at saturating nucleotide, but we consider this possibility less likely, as similar final fluorescence values at saturating ATP were also obtained when ClpX was bound to ClpP or was translocating an unfolded substrate into ClpP for degradation (Fig. 1D inset). Thus, if 4L:2U and 6L ClpX species were equally populated at saturating nucleotide, this equilibrium would have to be independent of the identity of the bound nucleotide and independent of ClpP binding and ATP-fueled protein degradation.

A test of subunit switching

In principle, L subunits and U subunits could either maintain their conformations during the chemo-mechanical cycle of ClpX or switch dynamically. Fig. 1E shows several non-switching and switching models, but many more are possible, including variations in which ATP hydrolysis occurs sequentially or probabilistically among the L subunits that bind nucleotide and/or models in which subunit switching is not coupled to ATP hydrolysis.

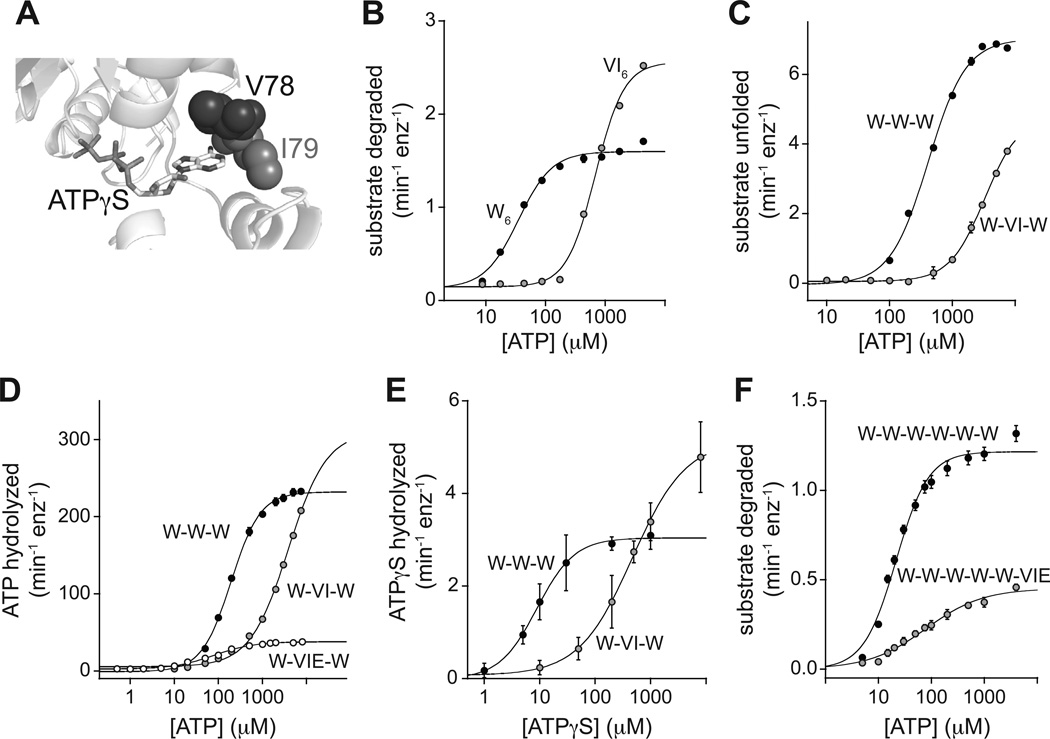

One way to determine if L and U subunits maintain their conformations during ATP hydrolysis and protein unfolding by ClpX is to reduce ATP-binding affinity to one or a few subunits in the hexamer and test for effects on the ATP concentrations required for these activities. The logic is that non-switching models would allow low-affinity subunits to adopt U conformations, and thus the concentration of ATP required for activity should not be significantly altered. By contrast, if nucleotide must bind to each subunit in the ring at some point in a cycle, as required by most switching models, then substantially higher concentrations of ATP would be required for equivalent levels of ClpX activity. To weaken nucleotide affinity, we engineered V78A/I79A substitutions (hereafter called VI) to truncate the wild-type side chains and reduce packing with the adenine base of ATP (Fig. 2A). As anticipated, substantially higher concentrations of ATP were required to support ATP hydrolysis and ClpP-mediated protein degradation by the VI homohexamer compared to the parental enzyme (Fig. 2B; Table S2).

Figure 2. VI mutations alter the ATP dependence of ClpX function.

(A) The side chains of Val78 and Ile79 contact the adenine base of bound nucleotide.

(B) The VI mutations (V78A/I79A) in a non-tethered hexamer (VI6) increased the concentration of ATP required to support degradation of cp7-CFP-ssrA (20 µM) by ClpP14 (0.9 µM) compared to an otherwise identical hexamer (W6) without the VI mutations. The VI6 and W6 concentrations were 0.3 µM. In panels B–F, data are shown as mean ± SD, and lines are fits to a Hill equation. Values of fitted parameters are listed in Table S2.

(C) ATP dependence of the unfolding of cp7-CFP-ssrA (10 µM) by the W-W-W and W-VI-W ClpX variants (1 µM pseudo hexamer). This experiment and those in panels D and E contained 10 mM Co2+ and no Mg2+.

(D) ATP dependence of the rate of ATP hydrolysis for W-W-W, W-VI-W, or W-VIE-W (0.3 µM pseudo hexamer).

(E) ATPγS dependence of the rate of ATPγS hydrolysis for W-W-W (0.1 µM pseudo hexamer) and W-VI-W (2 µM pseudo hexamer).

(F) ATP dependence of the degradation of cp7-CFP-ssrA (20 µM) by ClpP (0.5 µM) supported by the W-W-W-W-W-W or W-W-W-W-W-VIE ClpX variants (0.2 µM pseudo hexamer).

To test the predictions of a 4L:2U non-switching model, we constructed a covalently tethered W-VI-W trimer and found that protein unfolding, ATP hydrolysis, and ATPγS hydrolysis all required ~10-fold higher ATP/ATPγS concentrations to achieve activities comparable to the W-W-W parent (Fig. 2C–E; Table S2). Like its wild-type counterparts, the W-VI-W enzyme ran as a pseudo hexamer in gel filtration and bound 3–4 ADPs in isothermal titration calorimetry (Fig. S2A–C). We also introduced the E185Q mutation into the VI subunit to generate W-VIE-W, as this mutation should only affect activity if nucleotide binds the VIE subunit, and found that W-VIE-W had much lower ATP-hydrolysis activity than W-VI-W (Fig. 2D). These results are inconsistent with a non-switching 4L:2U model and suggest that robust activity requires ATP occupancy and hydrolytic activity by at least one VI or VIE subunit in these pseudo hexamers.

To test a 5L:1U non-switching model, we constructed W-W-W-W-W-VIE and W-W-VIE-W-W-W enzymes, which had properties similar to each other (Table S2; Fig. S2D). In both cases, higher concentrations of ATP were required for function compared to the parental W-W-W-W-W-W enzyme and maximal activity was also reduced (Fig. 2F; Fig. S2D). These results suggest that ATP binds to the single VIE subunit of these pseudo hexamers, a result inconsistent with non-switching models. Additional pseudo hexamers with five wild-type subunits and one subunit with multiple mutations affecting ATP binding and/or hydrolysis also required increased concentrations of ATP for function (Fig. S2D).

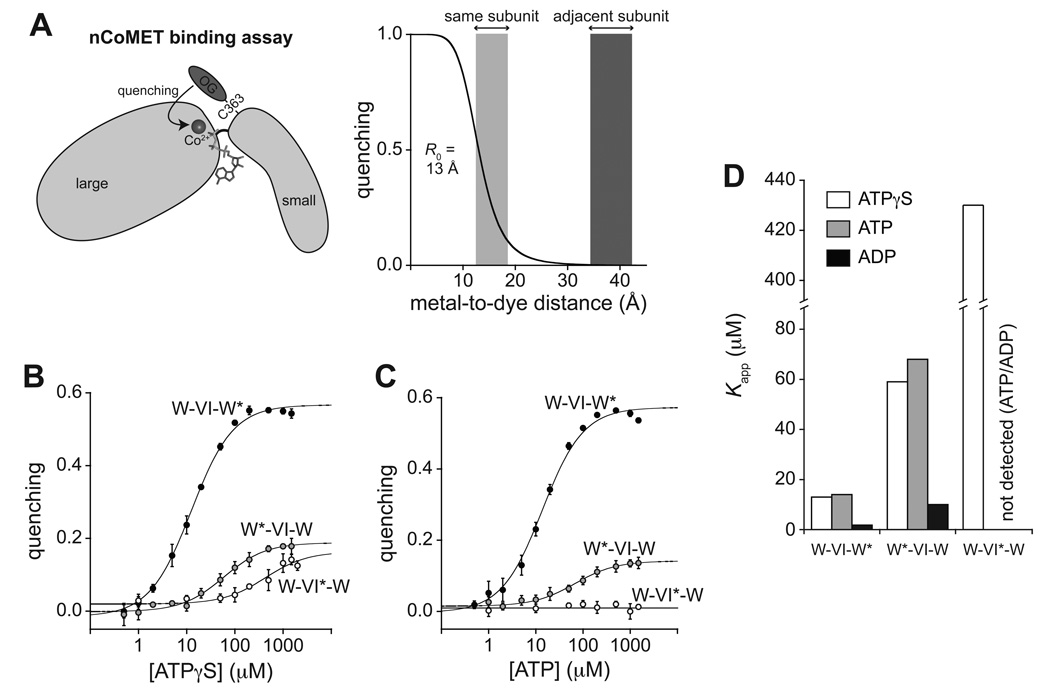

An assay for subunit-specific nucleotide binding

We developed nCoMET to measure nucleotide binding to specific sites in the ClpX ring. Mg2+ and nucleotide normally bind ClpX together, but Co2+ substitutes for Mg2+ and can quench the fluorescence of a nearby Oregon-Green dye with a calculated Förster radius (R0) of ~13 Å (Fig. 3A). We attached this dye to ClpX residue M363C in just one subunit of the W-VI-W trimer, which should position the dye ~10–15 Å from the metal in the nucleotide-binding site of the same subunit. By contrast, the closest neighboring nucleotide-binding site is ~35 Å away, a distance at which nucleotide/Co2+ binding would cause less than 1% quenching. Although Mg2+ is normally required for ClpX function, Co2+ supported ATP/ATPγS hydrolysis and protein unfolding by W-VI-W and W-W-W (Fig. S3A–C), although it inhibited the ClpP peptidase (Fig. S3D). Indeed, the assays shown in Fig. 2C, 2D, and 2E contained Co2+ but no Mg2+ to allow comparisons of ClpX function and nucleotide binding under the same conditions. Modification of M363C with the Oregon-Green dye was also compatible with ClpX activity (Fig. S3E).

Figure 3. nCoMET detects nucleotide binding to specific subunits.

(A) In the nCoMET assay, nucleotide binds ClpX and coordinates a Co2+ ion, which quenches the fluorescence of an Oregon-Green dye attached to M363C in the small AAA+ domain of a ClpX subunit. Given the calculated R0, quenching would be substantial from nucleotide/Co2+ bound in the same subunit but minimal from nucleotide/Co2+ bound in neighboring subunits.

(B) – (C) ATPγS and ATP binding to pseudo hexamers of W*-VI-W, W-VI*-W, and W-VI-W* assayed by nCoMET. Data are shown as mean ± SD, and the lines are fits to a hyperbolic equation. Kapp values are listed in Table S2. The panel-B experiment contained 0.1 µM nCoMET variants (pseudo hexamer equivalents). The panel-C experiment contained 0.5 µM pseudo hexamer and 10 µM cp7-CFP-ssrA.

(D) Summary of fitted Kapp values for nucleotide binding to different classes of subunits. See also Fig. S3 and Table S3.

To allow nCoMET binding assays to different subunits, we generated and purified W*-VI-W, W-VI*-W, and W-VI-W* pseudo hexamers, where the asterisk indicates the subunit containing the nCoMET probe. Titration experiments were performed using ATP in the presence of protein substrate (Fig. 3B), ATPγS without substrate (Fig. 3C), or ADP without substrate (Fig. S3F). In each case, binding to the rightmost W* subunit was tight (Kapp 2–14 µM), binding to the leftmost W* subunit was weaker (Kapp 60–90 µM), and binding to the VI* subunit was even weaker (Kapp 430 µM) or undetectable (Fig. 3D; Table S2). For ATP and ATPγS, Kapp values are a function of the rate constants for nucleotide association and dissociation, the rate constant for hydrolysis, and the rate constant for ADP dissociation, and thus are greater than true KD’s. Nevertheless, ADP and ATP/ATPγS bound ClpX subunits over similar concentration ranges (Fig. 3D), a finding we return to in the Discussion.

For ATPγS hydrolysis by W-VI-W, KM (470 µM) was similar to Kapp (430 µM) for nCoMET binding to the VI subunit in W-VI*-W (Table S2). For ATP hydrolysis by W-VI-W in the presence of protein substrate, KM (~4 mM) was 20-fold greater than the ATP concentration required for nCoMET binding to the weakest wild-type subunits in W*-VI-W or W-VI-W* (Fig. 3D; Table S2). Thus, as expected for a subunit-switching model, the high ATP/ATPγS concentrations required to support W-VI-W function appear to reflect binding of these nucleotides to the VI subunit.

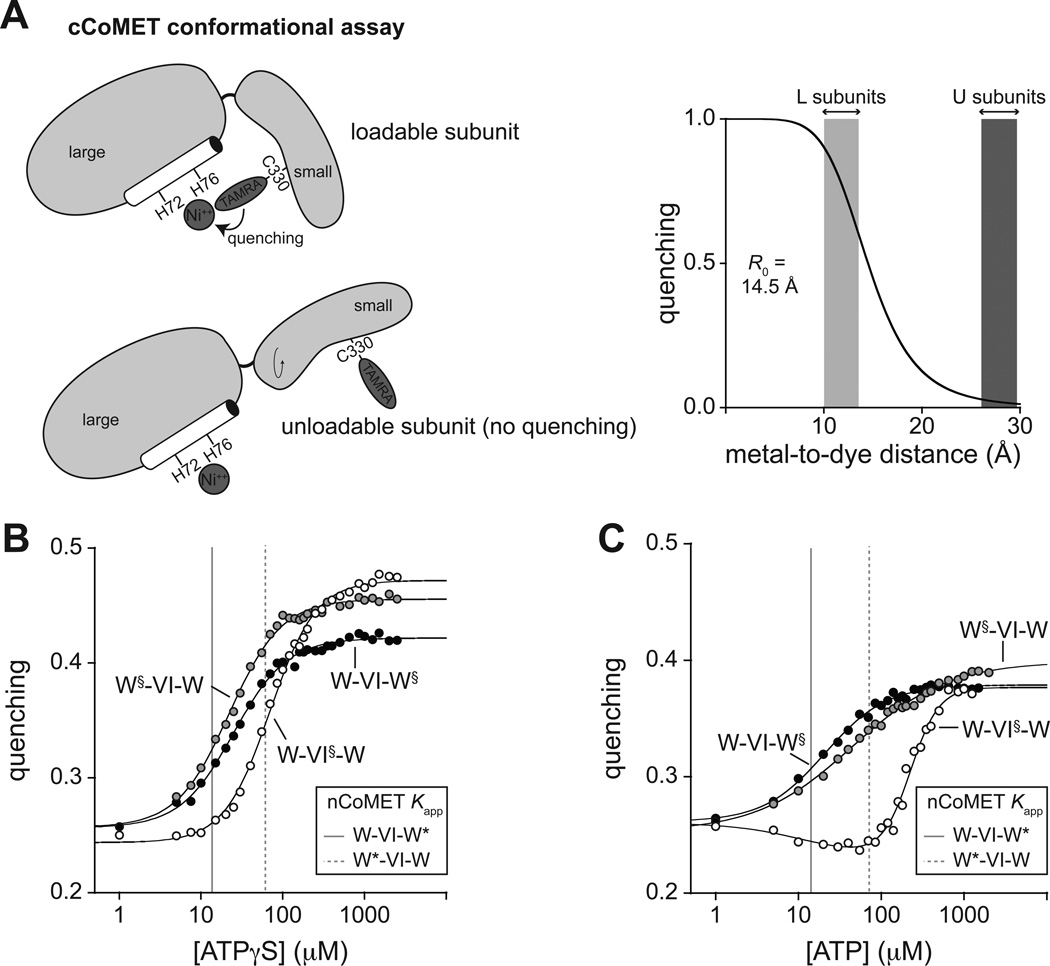

Subunit-specific conformational changes

We developed cCoMET to assay how the conformations of specific subunits in the ClpX ring were altered by nucleotide binding. In this variation of tmFRET (Taraska et al., 2009), quenching is determined by the distance between a TAMRA dye attached to K330C in the small AAA+ domain and a Ni2+ ion bound to an a-helical His-X3-His motif in the large domain of the same subunit (Fig. 4A). The His-X3-His site was engineered by introducing N72H and D76H mutations in combination with H68Q to remove an alternative Ni2+-binding site, and nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) was included in assays to minimize Ni2+ binding to nucleotides. The calculated R0 for the Ni2+-TAMRA pair is ~14 Å, and thus strong quenching should occur in L subunits (modeled distance 8–15 Å) and weak or no quenching should occur in U subunits (19–31 Å). The mutations and modifications required for this assay did not affect ATP hydrolysis or protein degradation (Fig. S4A,B).

Figure 4. cCoMET detects conformational changes in specific subunits.

(A) The cCoMET assay measures quenching of a TAMRA dye attached to K330C in the small domain of a ClpX subunit by a Ni2+ ion bound to an a-helical His-X3-His motif in the large domain. Based on distances estimated from crystal structures and a calculated R0, L subunits should display moderate quenching and U subunits should display little or no quenching.

(B) ATPγS-dependent changes in the conformations of subunits containing cCoMET probes (§) were assayed for pseudo hexamers (0.3 µM). Lines are fits to a Hill equation with Kapp and n values of 22 ± 1 µM and 1.4 ± 0.1 (W§-VI-W), 70 ± 2 µM and 1.5 ± 0.1 (W-VI§-W), or 25 ± 1 µM and 1.3 ± 0.1 (W-VI-W§). The solid gray vertical line represents Kapp for tight binding to the rightmost subunit of W-VI-W* in nCoMET experiments, whereas the dashed vertical linerepresents Kapp for weak binding to the leftmost subunit in W*-VI-W. (C) ATP-dependent cCoMET conformational changes using 0.3 µM pseudo hexamers and 10 µM cp7-CFP-ssrA. Lines are either fits to a Hill equation (Kapp and n values of 45 ± 4 µM and 0.8 ± 0.1 for W-VI-W, and 21 ± 1 µM and 1.2 ± 0.1 for W-VI-W§) or a hyperbolic plus Hill equation for W-VI-W (hyperbolic phase, Kapp = 12 ± 18 µM, amplitude = −0.03; Hill phase, Kapp = 230 ± 13 µM, n = 2.5 ± 0.3, amplitude = 0.15). The solid gray and dashed vertical lines represent Kapp values for binding to tight and weak subunits as defined in panel B.

See also Fig. S4.

We introduced the cCoMET modifications (§) to generate W§-VI-W, W-VI§-W, and W-VI-W§ pseudo hexamers and assayed the nucleotide dependence of fluorescence quenching using conditions differing from nCoMET only in the divalent metals. Changes in cCoMET quenching were determined as a function of ATP with protein substrate present (Fig. 4B), as a function of ATP without substrate (Fig. 4C), and as a function of ADP without substrate (Fig. S4C). As nucleotide increased, quenching generally increased from an initial value to a plateau that depended upon the variant and nucleotide. Several conclusions follow from these assay results. (a) At saturating nucleotide, the average distance between the dye and Ni2+ decreased both in W§ and in VI§ subunits. (b) Conformational changes in both the leftmost and rightmost W§ subunits occurred at low nucleotide concentrations, where only the rightmost subunits were substantially occupied in nCoMET assays (Fig. 4B,C). Thus, the first nucleotide-binding events cause allosteric changes in both bound (rightmost W) and unbound (leftmost W) subunits of the ring, possibly altering the hinge conformations and rigidifying the domain-domain interfaces in L subunits. (c) In VI§ subunits, the Ni2+-dye distance increased slightly at low ATP concentrations and then decreased substantially at higher ATP concentrations (Fig. 4C). The low-ATP transition corresponds to binding to tight W sites in nCoMET assays, whereas the high-ATP transition occurred at concentrations at which ATP binding to both weak W subunits as well as VI subunits was observed. Thus, nucleotide binding to weak W and VI subunits stabilizes a different conformation (possibly a 5L:1U ring) than binding to tight subunits. (d) Although there were small differences depending on the nucleotide, the magnitude of maximal quenching in VI§ and W§ subunits was generally similar, suggesting that these subunits spend roughly comparable amounts of time in L and U conformations because of switching.

We also performed cCoMET and nCoMET assays using W-W-W§ and W-W-W* constructs (Fig. S3G, Fig. S4D). In these cases, signal amplitudes were similar to those observed with the W-VI-W proteins, but averaging over all types of subunits precluded rigorous determination of interaction constants for individual classes.

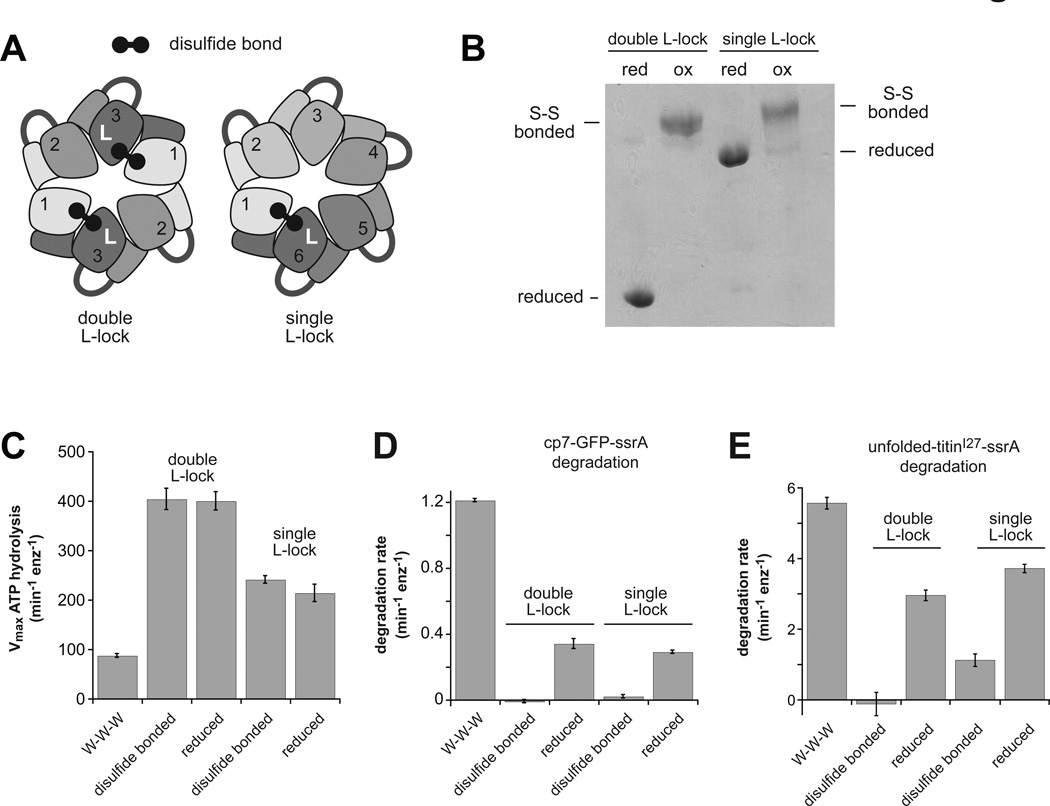

Locking subunits in the L conformation prevents unfolding and degradation

To prevent L→U switching, we engineered disulfide bonds to lock a single subunit or two opposed subunits of a pseudo hexamer in the L conformation. A T147C cysteine (TC) in the large domain of one subunit can form a disulfide with an E205C cysteine (EC) in the large domain of the clockwise subunit, only when the TC subunit adopts the L conformation. We constructed a linked trimer, with the EC mutation in the first subunit and the TC mutation in the third subunit, and we also constructed a linked hexamer, with the EC mutation in the first subunit and the TC mutation in the sixth subunit. Disulfide formation between two trimers forms a covalently closed hexameric ring, with subunit 3 of each trimer in the L-lock conformation (called double L-lock; Fig. 5A). Disulfide formation in the linked hexamer covalently closes the ring and locks subunit 6 in the L conformation (called single L-lock; Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Effects of L-lock disulfides on ClpX function.

(A) Cartoon depiction of L-lock disulfide bonds between cysteines in the adjacent large AAA+ domains of subunits in the L conformation.

(B) Non-reducing SDS-PAGE of the single and double L-lock proteins before and after treatment with 20 mM copper phenanthroline. For the single L-lock enzyme, ~15% of the sample was not disulfide bonded after oxidation.

(C) Maximal rates of ATP hydrolysis were determined by Michaelis-Menten experiments using the indicated ClpX variants (0.3 µM pseudo hexamers). KM values were 100 ± 19 µM (W-W-W), 2700 ± 350 µM (disulfide bonded double L-lock), 1250 ± 190 µM (reduced double L-lock), 440 ± 45 µM (disulfide bonded single L-lock), and 490 ± 120 µM (reduced single L-lock).

(D) Rates of degradation of cp7-GFP-ssrA (10 µM) by the indicated ClpX variants (0.3 µM pseudo hexamers) and ClpP14 (0.5 µM) in the presence of ATP (4 mM) and an ATP-regeneration system.

(E) Rates of degradation of titin127-ssrA (20 µM) denatured by reaction with fluorescein-iodoacetamide by the indicated ClpX variants (0.3 µM pseudo hexamers) and ClpP14 (0.9 µM) in the presence of ATP (10 mM) and an ATP-regeneration system. In panels C–E, data are shown as mean ± SD.

See also Fig. S5.

We purified these variants, catalyzed oxidation with copper phenanthroline, and confirmed that disulfides were formed by non-reducing SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5B), although 10–15% of the single L-lock protein remained reduced. The disulfide-bonded L-lock enzymes hydrolyzed ATP (Fig. 5C) at maximum rates comparable to the reduced enzymes but faster than a W-W-W control. In the presence of ClpP, which binds both variants (Fig. S5), the disulfide-bonded enzymes showed poor or undetectable degradation of a folded protein substrate (cp7-GFP-ssrA) compared to the reduced proteins or W-W-W (Fig. 5D). Similarly, the disulfide bonded double L-lock enzyme failed to degrade an unfolded substrate (titin127-ssrA with core cysteines modified by fluorescein) at an appreciable rate in the presence of ClpP, but degraded this substrate well following reduction (Fig. 5E). Following oxidation, the single L-lock enzyme displayed a low level of degradation of the unfolded substrate (Fig. 5E), although some of this activity may result from the reduced protein still present (Fig. 5B). ClpX rings topologically closed by formation of different disulfide bonds are fully active (Glynn et al., 2012). Thus, disulfide crosslinks that block L→U switching in one or two subunits of the ClpX ring uncouple ATP hydrolysis from efficient substrate unfolding and translocation.

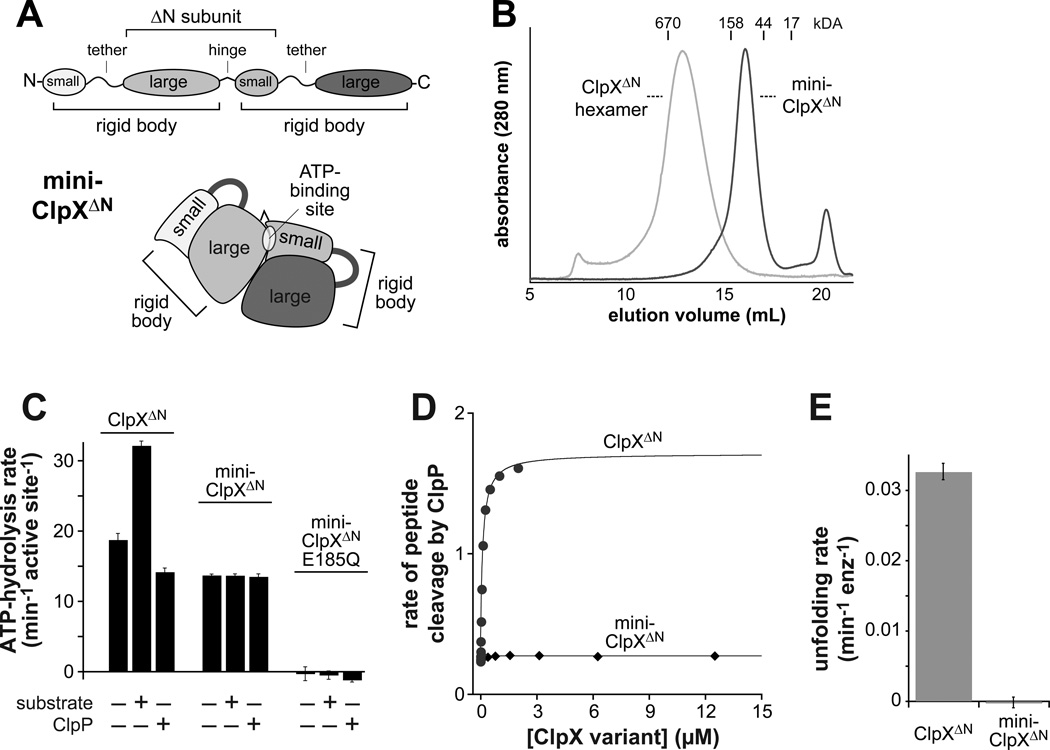

Subunit communication and ATP hydrolysis

To determine if ATP hydrolysis requires communication between different nucleotide-binding sites, we designed mini-ClpXΔN, which contains two rigid-body units that encompass a single nucleotide-binding site (Fig. 6A). We expected that a mini-ClpXΔN pseudo hexamer would not be stable because the surface buried between different rigid-body units is small (Glynn et al., 2009). Indeed, mini-ClpXΔN eluted at a position expected for a molecule with two subunits in gel-filtration experiments (Fig. 6B). Mini-ClpXΔN hydrolyzed ATP at approximately 75% of the basal rate of a ClpXΔN hexamer on a per site basis, the KM for ATP was similar for mini-ClpXΔN (210 µM) and W-W-W (230 µM; Table S2), and hydrolysis activity was abolished by an E185Q mutation in the single nucleotide-binding site in mini-ClpXΔN (Fig. 6C). Thus, hexamer formation and communication between different nucleotide-binding sites are not required for ATP binding and hydrolysis. However, mini-ClpXΔN did not bind ClpP (Fig. 6D) and exhibited no evidence of interacting with or unfolding protein substrates (Fig. 6C, 6E), suggesting that hexamer formation is required for these activities.

Figure 6. ATP hydrolysis by a variant with one binding site does not support function.

(A) Cartoon depiction of the domain structure of mini-ClpXΔN. This variant contains two rigid-body units but only one complete ATP-binding site.

(B) Mini-ClpXΔN (loading concentration 12 µM) chromatographed at a position expected for a pseudo dimer on a Superose 6 gel-filtration column. The elution position of a single-chain ClpXΔN hexamer is shown for reference.

(C) Mini-ClpXΔN hydrolyzed ATP at approximately 75% of the basal rate of single-chain ClpXΔN when activities were normalized for the number of active sites. Unlike ClpXΔN, ATP hydrolysis by mini-ClpXΔN was not stimulated by protein substrate (10 µM V15P-titinI27-ssrA) or repressed by ClpP14 (3 µM). In panels C and E, data are shown as mean ± SD.

(D) The rate of cleavage of a fluorescent decapeptide (15 µM) by ClpP14 (50 nM) in the presence of increasing concentrations of single-chain ClpXΔN or mini-ClpXΔN was determined in the presence of 1 mM ATPγS.

(E) Unfolding rates of photo-cleaved Kaede-ssrA (5 µM; Glynn et al., 2012) by single-chain ClpXΔN or mini-ClpXΔN (2 µM) were determined in the presence of 2.5 mM ATP and a regeneration system.

DISCUSSION

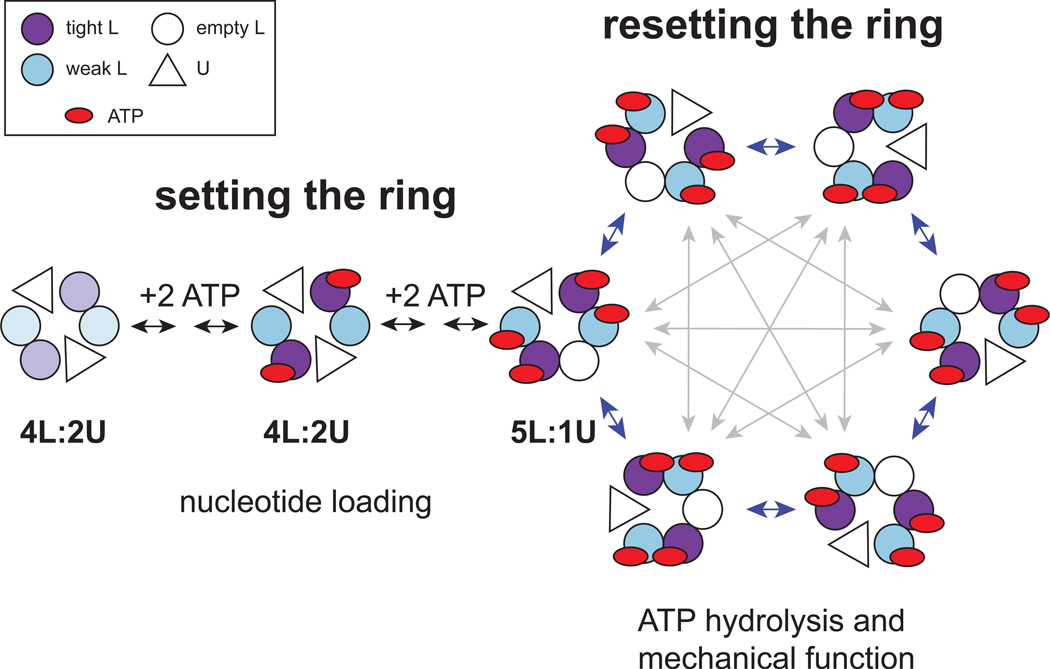

Setting and resetting the configuration of the ClpX ring

Our results support a model in which (i) the conformation of the hexameric ClpX ring is initially “set” in a staged nucleotide-binding reaction to allow ATP hydrolysis, and (ii) the configuration of the nucleotide-loaded ring is subsequently “reset” via isomerization that involves changes in the nucleotide-binding properties of subunits and reciprocal U→L and L→U subunit switching events that occur synchronously. Fig. 7 shows a model for ring-setting and ring-resetting reactions in which ATP binding causes one ClpX subunit in a 4L:2U ring to switch from a U→L conformation, resulting in a 5L: 1U ring. We expect the 5L: 1U structure to persist as long as ATPis plentiful but cannot exclude models in which the ring occasionally reverts to a 4L:2U structure. More complicated models in which the active enzyme is a 6L ring that switches through a 4L:2U intermediate, or that involve mixtures of 4L:2U, 5L:1U, and 6L rings are also possible. We favor the 5L:1U model shown, in part, because structures with five L-like subunits and one U-like subunit are observed in the AAA+ rings of the E1 helicase and 26S proteasome (Enemark and Joshua-Tor, 2006; Lander et al., 2012), and a 5L:1U ClpX ring is structurally plausible. Because a maximum of ~4 nucleotides bind to the ClpX hexamer (Hersch et al. 2005; Fig. S2B), we also posit that a 5L:1U ring contains one L subunit that is nucleotide free or binds nucleotide only transiently.

Figure 7. Model for ring-setting and ring-resetting reactions.

The left side of the figure shows the proposed ring-setting reaction. In the absence of nucleotide, ClpX hexamers mainly adopt a 4L:2U ring structure with two U subunits (triangles), two Lsubunits with high affinity for nucleotide (light purple circles), and two L subunits with low affinity for nucleotide (light blue circles). ATP (red oval) binding to the high-affinity subunits changes the conformations of both classes of loadable subunits (designated by color darkening), but this intermediate is inactive in ATP hydrolysis. Subsequent ATP binding to the low-affinity L subunits stabilizes a 5L:1U configuration of the ring, which is active in ATP hydrolysis, but the new L subunit (white circle) has very low nucleotide affinity and is generally empty. The right side of the figure shows ring-resetting reactions (gray arrows), in which reciprocal L⇔U subunit switching changes the configuration of the ring. These isomerization reactions are required for efficient protein unfolding and translocation of substrates by ClpX. Resetting of the ring could occur sequentially, with subunit switching proceeding clockwise or counterclockwise in rotary order around the perimeter (blue arrows), or stochastically, with subunits switching in a probabilistic fashion (gray arrows). Many variations of the model shown are possible.

Stepwise conformational changes, driven initially by ATP binding to high-affinity subunits and subsequently by binding to lower-affinity subunits, are key features of the ring-setting reaction. Our results indicate that only the fully loaded ring can perform mechanical work and show that little or no ATP hydrolysis occurs in the partially loaded intermediate with just the high-affinity ATP sites occupied. Thus, the ring-setting reaction minimizes ATP hydrolysis before it can be coupled to functional work. However, the mini-ClpXΔN pseudo dimer, which has just one nucleotide-binding site, hydrolyzes ATP efficiently with a KM similar to wild-type hexamers. Thus, structural constraints imposed by formation of the hexameric ring appear to keep the high-affinity subunits in the partially loaded intermediate in a conformation poorly suited for ATP hydrolysis.

In our model, ring resetting involves synchronous and paired U→L and L→ subunit switching in the nucleotide-loaded ClpX hexamer, resulting in new isomers or ring configurations withindividual subunits having redefined nucleotide-binding properties determined by their position with respect to the U and/or empty L subunits (Fig. 7). As we discuss below, resetting the ring appears to be required for the mechanical functions of the ClpX machine. Ring resetting could be linked to ClpX activity in two ways. First, coupled L→U and U→L switching could be a normal consequence of ATP hydrolysis, occurring with each power stroke or some fixed number of power strokes. Alternatively, ring resetting could be independent of a fixed number of hydrolysis events. Such probabilistic resetting could provide a way to escape stalling in situations in which machine function might otherwise be compromised. These situations could include failed protein-unfolding attempts, as for very stable proteins fewer than 1% of ClpX ATP-hydrolysis events result in unfolding (Kenniston et al., 2003), or binding of an inappropriate nucleotide. For example, ADP binds ClpX subunits over concentration ranges similar to or lower than ATP, yet ClpX functions well in the presence of equimolar ATP and ADP (B.M.S., unpublished). Ring isomerization might allow ClpX to eject improperly bound ADP and avoid prolonged stalling and could also help explain how ClpX hexamers with only one or two hydrolytically active subunits escape stalling as they unfold and protein substrates (Martin et al., 2005).

Evidence for subunit switching

Our results support L⇔U switching during ClpX function. For example, we find that weakening the nucleotide affinity of one or two subunits in a hexamer increases the concentration of ATP/ATPyγS required for ClpX activity, a result expected for a switching model in which nucleotide must bind to every subunit in the hexameric ring at some time during the multiple enzyme cycles required for protein unfolding and translocation. In a non-switching model, by contrast, a low-affinity subunit could simply assume a U or empty L conformation and would only alter the ATP dependence of enzyme function by restricting the number of active ring configurations, which would produce much smaller activity effects than those we observe. Moreover, when we crosslink one or two ClpX subunits in the L conformation using disulfide bonds, these enzymes hydrolyze ATP and bind ClpP but do not efficiently unfold protein substrates and/or translocate unfolded substrates into ClpP, a result that suggests that ATP hydrolysis is not tightly coupled to mechanical work.

L⇔U switching is also supported by cCoMET results. Each type of subunit in the W-VI-W pseudo hexamer displayed roughly similar quenching at saturating concentrations of nucleotide. Thus, in a nucleotide-loaded ring, the average Ni2+-TAMRA distance must be similar in high-affinity and low-affinity W subunits as well as in VI subunits. Based on crystal structures, moderate quenching is expected for loadable subunits and very low quenching for unloadable subunits. Thus, our cCoMET results suggest that no single type of subunit in W-VI-W adopts just an L conformation or just a U conformation, but rather that all subunits sample both conformations. This result is inconsistent with non-switching models, in which the VI subunits would preferentially adopt the U conformation. For ATP and ATPyγS, hydrolysis-powered L⇔U switching could explain these results. For ADP, however, subunit switching would need to be thermally driven. Indeed, ongoing single-molecule studies using the assays described here show subunit switching in the presence of saturating ADP (A.R.N., T.A.B., R.T.S., Y. Shin, H. Manning, and M. Lang, unpublished).

Structural and functional classes of ClpX subunits

In our crystal structures, substantial conformational variations occur within the general L and U classes of ClpX subunits. Indeed, this variation could allow each L subunit in a 4L:2U or 5L:1U ring to have different nucleotide-binding properties. In previous studies of nucleotide binding to ClpX hexamers, evidence was presented for tight, weak, and empty sites with an approximate ratio of four binding to two non-binding subunits (Hersch et al., 2005). Subsequent studies with the hexameric HslU and PAN AAA+ unfoldases revealed similar nucleotide-binding categories and ratios (Yakamavich et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2011). Our current studies support multiple classes of nucleotide-binding sites, and suggest a basic ring pattern of [weak-empty-tight-weak-empty-tight] sites, with the proviso that empty sites may bind nucleotide transiently and very weakly. Based on our nCoMET and cCoMET studies, ATP binding to tight subunits alters the conformations of weak subunits, whereas ATP binding to weak subunits alters the conformations of empty subunits. These allosteric effects can be viewed as being propagated to the subunit clockwise from the bound subunit, probably through the shared rigid-body unit. Because the conformational changes observed in different classes of subunits occur over different ranges of nucleotide, allosteric models in which there are just two conformations of the ClpX ring can be rejected.

Sequential versus probabilistic models

Subunits of hexameric AAA+ and related enzymes may be coordinated by either a sequential model, in which ATP hydrolysis and conformational changes occur in an ordered progression around the ring, or by a probabilistic model, in which sequential events are possible but not obligatory. In the tightly coupled chemical and mechanical cycles of the F1 ATPase, for example, the hydrolytic β subunits switch in a strictly sequential reaction between conformations with different nucleotide-binding properties (Kinosita et al., 2000; Leslie and Walker, 2000). The structural changes in different classes of F1 subunits are less dramatic than L⇔U switching in ClpX subunits and can be considered analogous to the modest structural changes between different classes of L subunits. Our results suggest that ATP must bind to every subunit in the ClpX ring at some point during the multiple cycles required to unfold and translocate protein substrates and that these activities require U⇔L subunit switching. Whether these binding, hydrolysis, and switching reactions occur sequentially or probabilistically is unresolved, but several factors suggest that ClpX may operate by a mechanism that is at least partially probabilistic. First, as noted above, ClpX is rather insensitive to ADP inhibition, whereas inappropriate ADP binding stalls the F1 motor for very long periods (Hirono et al., 2001). Second, unlike F1, the ATP-hydrolysis and mechanical functions of ClpX are not tightly coupled. ClpX does not stall when unfolding fails, and our L-lock variants hydrolyze ATP rapidly without doing mechanical work. Third, previous studies showed that R-W-E-R-W-E rings, containing two non-adjacent W subunits that are hydrolytically active and four R or E subunits that are ATPase-defective, have ~30% of wild-type ClpX activity in ClpP-mediated degradation (Martin et al., 2005). Given our current results, ATP binding to non-hydrolytic subunits in R-W-E-R-W-E is likely to be important for setting the active conformation of the ring, and probabilistic subunit switching could then permit the two hydrolytic subunits to power substrate unfolding and translocation in a non-sequential reaction. We anticipate that assays at the single-molecule level, potentially using multi-color CoMET pairs in different subunits to establish how nucleotide binding and conformational switching are coordinated, will establish if ClpX and other AAA+ machines operate as strictly sequential motors, as probabilistic motors, or operate sequentially some of the time and probabilistically when necessary.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

PD buffer contained 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.5 mM EDTA. IEXA buffer contained 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 150 mM KCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 1 mM EDTA. GF buffer contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 300 mM KCl, and 10% (v/v) glycerol. ATP (Sigma), ADP (Sigma), ATPγS (Roche), and GTP (Sigma) were dissolved in PD buffer, and adjusted to pH 7.0 by addition of NaOH.

Proteins

Unless noted, all ClpX variants were derived from E. coli ClpXΔN (residues 61–423), contained the C169S mutation to remove an accessible cysteine, and were constructed by PCR and purified generally as described (Martin et al., 2005; 2007). During purification of variants with reactive cysteines, buffers were degassed, argon sparged, and contained 0.5 mM EDTA to minimize oxidation. Buffer exchange and desalting steps were performed using a PD10 column (GE Healthcare).

ClpX variants used for nCoMET experiments initially contained an N-terminal His6-SUMO domain. After Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen), these variants were exchanged into IEXA buffer, and the H6-SUMO domain was cleaved by incubation with equimolar Ulp1 protease for 2 h at room temperature. Cleavage was confirmed by SDS-PAGE, and the mixture was chromatographed on a MonoQ column (GE Healthcare) using a gradient from 150 to 500mM KCl. Fractions containing the nCoMET variant were incubated with Oregon Green 488 Maleimide (Invitrogen; 3 equivalents for each cysteine) for 30 min at room temperature and separated from unreacted dye on a Superdex S-200 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in GF buffer. The extent of labeling was > 90% as determined by absorbance of the purified protein at the maximum of the dye and at 280 nm for this reaction and those described below.

ClpX variants used for cCoMET initially contained a TEV-cleavable C-terminal His6 tag. After Ni2+-NTA affinity chromatography, these variants were exchanged into PD buffer, incubated with TAMRA-5-maleimide (1.5 equivalents for each cysteine) for 30 min at room temperature, dithiothreitol (1 mM) was added to quench the reaction, and excess dye was removed by desalting. Proteins were incubated with equimolar TEV protease for ~1 h at room temperature to remove the His6 tag, and a final purification step was performed using a Superdex S-200 column equilibrated in PD buffer. Disulfide-bond formation in L-lock variants was performed as described (Glynn et al., 2012).

The cp7-CFP-ssrA substrate was generated from cp7-GFP-ssrA (Nager et al., 2011) by PCR incorporation of the Y66W, A206K, and N146I mutations and initially contained a cleavable N-terminal His6 tag. cp7-CFP-ssrA was purified by Ni-NTA2+ affinity chromatography, exchanged into IEXA buffer, incubated with 10 units of PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) for 2 h at room temperature to remove the His6 tag, and the sample was diluted 5-fold into water and purified on a MonoQ column using a gradient from 30 to 500 mM KCl.

Crystallization and structure determination

Detailed methods are presented in the Supplement.

Fluorescence assays

Unless noted, assays were performed at room temperature in PD buffer, with nucleotides, metals, and substrate added as required. All nCoMET assays contained 10 mM CoCl2, and nucleotide-dependent changes in fluorescence were measured using a PTI QM-20000-4SE spectrofluorimeter (excitation 500 nm; emission: 520 nm). Signal contamination from fluorescent CFP substrates, when present, was less than 2%. Addition of 1 mM GTP did not result in nCoMET quenching (Fig. S6A), confirming specificity. Ni2+ can also be used for nCoMET and supports ClpX function, but Co2+ results in a larger R0 when paired with the Oregon-Green dye. nCoMET assays were limited to nucleotide concentrations below 2 mM, as higher concentrations appeared to alter fluorescence indirectly by binding Co2+.

All cCoMET assays contained 500 µM Ni2+, 500 µM NTA, and 10 mM MgCl2. NTA was included because it binds Ni2+ (KD ~ 1 nM) and reduces its affinity for free and ClpX-bound nucleotides but does not prevent binding to the His-X3-His motif. Titration of ATP against W-W-W§ in the absence of Ni2+-NTA resulted in no quenching (Fig. S6B). Titration of Ni2+-NTA against W-W-W§ resulted in ~30% quenching with an affinity of 25 ± 2 µM (Fig. S6C). cCoMET can detect small conformational changes. For example, when a cCoMET pair was placed within a single rigid-body unit, ATP binding to high-affinity subunits resulted in quenching (Fig. S6D). Conformational changes of 3–4 Å caused by a minor change in the rigid body or side-chain movements that alter the dye-quencher distance, could account for these results.

The degree of TAMRA-TAMRA contact quenching for W-W-WTT was determined relative to a control experiment with W-W-WTT in 3 M urea (a W-W-WTT sample degraded with elastase showed the same fluorescence as the sample in urea).

The apparent nucleotide affinities of individual subunits observed using nCoMET represent a time-weighted average over multiple conformations that occur as a consequence of subunit switching and other conformational changes. Thus, nCoMET may detect ATPγS but not ATP binding to the VI subunits of W-VI*-W because these subunits spend very little time in an ATP-bound state as a consequence of rapid hydrolysis and subsequent ADP dissociation. Alternatively, nCoMET would fail to detect a nucleotide bound without a companion Co2+ ion. This situation is unlikely to occur for ATP, because Co2+ binding is also required for hydrolysis, but could explain why no ADP binding to VI subunits was detected.

Biochemical assays

ATP hydrolysis was measured by a coupled assay (Nørby, 1988). ATPγS hydrolysis was analyzed by ion-pair chromatography on a Shimadzu Class-VP HPLC. Time points were taken by quenching the reaction with excess dithiothreitol (when Co2+ was present) or by the addition of one-quarter volume of 50% trichloroacetic acid. Samples were directly loaded onto a Waters Delta-Pak C18 column (300 Å, 5 µM, 3.9 × 150 mm) equilibrated in 30 mM triethylammonium phosphate (pH 5.5) and eluted isocratically. Hydrolysis was measured by quantifying the ADP and ATPγS peaks (retention times ~6 min and ~15 min, respectively) and calculating the amount of ADP formed as a fraction of total nucleotide. ATP-hydrolysis rates measured by the coupled assay and the HPLC assay were within experimental error.

The rate of cp7-CFP-ssrA unfolding was calculated from the initial rate of loss of fluorescence measured with an SF-300X stopped flow instrument (KinTek). Pre-mixed ClpX and substrate were rapidly mixed with an equal volume of ATP solution and substrate fluorescence was monitored (excitation 435 nm; emission 495 nm long-pass filter).

ClpP peptide-cleavage assays were performed using a succinyl-Leu-Tyr-AMC dipeptide or a decapeptide containing an N-terminal 2-aminobenzoic acid fluorophore and nitro-tyrosine quencher at residue nine as described (Lee et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

New ClpX crystal structures show nucleotide-loadable and unloadable subunits

Novel assays detect subunit-specific ATP binding and conformational changes

ATP binding drives staged allosteric changes in the ClpX ring

Work requires dynamic interconversion between loadable and unloadable conformations

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C. Drennan, Y. Goldman, R. Grant, K. Knockenhauer, M. Lang, C. Lukehart, A. Olivares, O. Yosefson, and T. Schwartz for help and discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM-101988. T.A.B. is an employee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Studies using the NE-CAT beamline were supported by the NCRR (5P41RR015301-10) and NIGMS (8P41 GM103403-10). Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the US DOE (contract DE-AC02-06CH11357).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The Protein Data Bank accession codes for the new ClpX hexamer structures are 4I81, 4I4L, 4I34, 4I5O, 4I63, and 4I9K (Table S1).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Data include six figures, three tables, and some experimental procedures.

REFERENCES

- Aubin-Tam ME, Olivares AO, Sauer RT, Baker TA, Lang MJ. Single-molecule protein unfolding and translocation by an ATP-fueled proteolytic machine. Cell. 2011;145:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, Sauer RT. ClpXP, an ATP-powered unfolding and protein-degradation machine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1823:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark EJ, Joshua-Tor L. Mechanism of DNA translocation in a replicative hexameric helicase. Nature. 2006;442:270–275. doi: 10.1038/nature04943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SE, Martin A, Nager AR, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Crystal structures of asymmetric ClpX hexamers reveal nucleotide-dependent motions in a AAA+ protein-unfolding machine. Cell. 2009;139:744–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SE, Nager AR, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Dynamic and static components power unfolding in topologically closed rings of a AAA+ proteolytic machine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012;19:616–622. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson PI, Whiteheart SW. AAA+ proteins: have engine, will work. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;6:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersch GL, Burton RE, Bolon DN, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Asymmetric interactions of ATP with the AAA+ ClpX6 unfoldase: allosteric control of a protein machine. Cell. 2005;121:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirono-Hara Y, et al. Pause and rotation of F(1)-ATPase during catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA. 2001;98:13649–13654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241365698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenniston JA, Baker TA, Fernandez JM, Sauer RT. Linkage between ATP consumption and mechanical unfolding during the protein processing reactions of an AAA+ degradation machine. Cell. 2003;114:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinosita K, Yasuda R, Noji H, Adachi K. A rotary molecular motor that can work at near 100% efficiency. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000;355:473–489. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander GC, Estrin E, Matyskiela ME, Bashore C, Nogales E, Martin A. Complete subunit architecture of the proteasome regulatory particle. Nature. 2012;482:186–191. doi: 10.1038/nature10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ME, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Control of substrate gating and translocation into ClpP by channel residues and ClpX binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;399:707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AG, Walker JE. Structural model of F1-ATPase and the implications for rotary catalysis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000;355:465–471. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard RA, Chistol G, Sen M, Righini M, Tan J, Kaiser CM, Hodges C, Martin A, Bustamante C. ClpX(P) generates mechanical force to unfold and translocate its protein substrates. Cell. 2011;145:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Rebuilt AAA+ motors reveal operating principles for ATP-fueled machines. Nature. 2005;437:1115–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature04031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Distinct static and dynamic interactions control ATPase-peptidase communication in a AAA+ protease. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Diverse pore loops of the AAA+ ClpX machine mediate unassisted and adaptor-dependent recognition of ssrA-tagged substrates. Mol. Cell. 2008a;29:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Pore loops of the AAA+ ClpX machine grip substrates to drive translocation and unfolding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008b;15:1147–1151. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nager AR, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Stepwise unfolding of a β barrel protein by the AAA+ ClpXP protease. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;413:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nørby JG. Coupled assay of Na+,K+-ATPase activity. Methods Enzymol. 1988;156:116–119. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)56014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh SK, Rozycki J, Ortega J, Ishikawa T, Lo J, Steven AC, Maurizi MR. Functional domains of the ClpA and ClpX molecular chaperones identified by limited proteolysis and deletion analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29420–29429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Fraga H, Reis C, Kafri G, Goldberg AL. ATP binds to proteasomal ATPases in pairs with distinct functional effects, implying an ordered reaction cycle. Cell. 2011;144:526–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraska JW, Puljung MC, Olivier NB, Flynn GE, Zagotta WN. Mapping the structure and conformational movements of proteins with transition metal ion FRET. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:532–537. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtyra UA, Thibault G, Tuite A, Houry WA. The N-terminal zinc binding domain of ClpX is a dimerization domain that modulates the chaperone function. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48981–48990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakamavich JA, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Asymmetric nucleotide transactions of the HslUV protease. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;380:946–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou R, Kunzelmann S, Webb MR, Ha T. Detecting intramolecular conformational dynamics of single molecules in short distance range with subnanometer sensitivity. Nano Lett. 2011;11:5482–5488. doi: 10.1021/nl2032876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.