Abstract

As an important molecule in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), amyloid-β (Aβ) interferes with multiple aspects of mitochondrial function, including energy metabolism failure, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and permeability transition pore formation. Recent studies have demonstrated that Aβ progressively accumulates within mitochondrial matrix, providing a direct link to mitochondrial toxicity. Aβ-binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) is localized to the mitochondrial matrix and binds to mitochondrial Aβ. Interaction of ABAD with Aβ exaggerates Aβ-mediated mitochondrial and neuronal perturbation, leading to impaired synaptic function, and dysfunctional spatial learning/memory. Thus, blockade of ABAD/Aβ interaction may be a potential therapeutic strategy for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β, mitochondria, energy metabolism, ABAD

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder clinically characterized by progressive cognitive dysfunction and memory loss. The pathological hallmarks of AD are senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and selective synaptic and neuronal loss in brain regions involved in learning and memory. Both genetic and transgenic mouse model studies have established that Aβ, a 39 to 43 amino acid peptide derived from amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP), plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD [17]. However, mechanisms underlying Aβ-induced neurotoxicity remain to be fully elucidated. Growing evidence suggests that Aβ has deleterious effects on mitochondrial function and contributes to energy failure, neuronal apoptosis and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in AD brain. This review summarizes our recent findings suggesting that Aβ accumulates in mitochondrial matrix and binds to mitochondrial enzymes, eventually causing neuronal perturbation relevant to AD pathology.

EVIDENCE OF MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION IN AD

As the “power houses” of eukaryotic cells, mitochondria contain both citric acid cycle enzymes and respiratory chain components in their matrix and inner membrane. Mitochondrial oxidation begins with production of acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) from either dehydrogenation of glycolysis-derived pyruvate or β-oxidation of fatty acids. Acetyl CoA is funneled into the citric acid cycle to generate NADH and FADH2. Oxidative phophorylation is carried out by the respiratory chain carriers located in mitochondrial inner membrane. The transfer of high energy electrons from NADH and FADH2 to the electron transport chain results in extraction of the energy to produce ATP. Several initial studies have demonstrated decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity in the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortex of AD brains [5,32,35]. Gibson et al. [11] reported that α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH) activity was significantly reduced in AD temporal and parietal cortex. Decreased enzymatic activity did not correlate with the changes in protein expression, suggesting that inhibition, rather than reduced amounts of protein, account for the decrease in KGDH activity. Reduced levels of E1k and E2k subunits of KGDH were also demonstrated in the brains from familial AD patients bearing the APP670/671 mutation, suggesting that defects in the Krebs cycle might be an important downstream component in the cascade starting with disturbed Aβ metabolism and leading to final AD pathology [12]. When multiple enzymes of the citric acid cycle were assayed in the autoptic AD brain, the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex showed a significant decrease in the activities of PDH (−41%), isocitrate dehydrogenase (ICDH, −27%), and KGDH (−57%). The decrease of PDH and KGDH activities correlated with a deteriorating clinical dementia rating (CDR) score, and the decrease in PDH activity correlated with increased mean plaque count [2]. Since PDH, ICDH and KGDH are dehydrogenases in the first half of the citric acid cycle and they catalyze decarboxylation, this could represent coordinated regulation of metabolic pathways or a shared vulnerability due to their similar enzymatic properties. The search for genetic mutations in these enzymes associated with AD has been largely inconclusive, suggesting an acquired mechanism.

In 1990, Parker et al. [30] reported about 50% reduction of cytochrome oxidase (COX) activity in platelet mitochondria isolated from patients with AD. They reported that, while concentrations of cytochrome b, c1 and aa3 (a physical representation of COX) remain stable in AD, there is a general depression of respiratory chain enzyme activities with the most severe defect observed in COX activity. Depressed COX activity has also been shown in homogenates of various brain regions, including frontal (−26%), temporal (−17%) and parietal (−16%) cortices as reported by Kish et al. [20]. Histochemical study by Valla et al. [41] demonstrated that the most significant decline occurred in the posterior cingulate cortex and is most severe in the superficial, synapse-rich molecular layer of cortex. Purified COX from AD brains displayed anomalous kinetic behavior as compared with COX purified from control brains in that the low Km binding site was kinetically absent. This observation implies a structural abnormality in COX purified from AD brain [31].

Along with the abnormalities in oxidative energy metabolism discussed above, there is also evidence of oxidative stress in AD brain. Mitochondria generate most of endogenous ROS as toxic by-products of oxidative phosphorylation. ROS production is increased when the electron carriers in the initial steps of the respiratory chain harbor excess electrons resulting from either inhibition of later steps of respiratory chain or from excessive energy consumption. Excess electrons can be donated directly to O2 to generate superoxide anion (O2−) and other ROS [42]. Oxidative stress in AD brain is manifested by increased protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation, nucleic acid oxidation and glycooxidation [4].

A direct effect of Aβ on mitochondrial properties is further suggested by in vitro experiments in which cultured cells or isolated mitochondria were exposed to Aβ. In the micromolar concentration range, Aβ induced dose-dependent generation of ROS and ATP depletion associated with depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane, decreased oxygen consumption and inhibition of respiratory chain enzymes in PC12 cells [33]. Addition of Aβ to isolated rat brain mitochondria inhibited respiration and COX activity [6]. A recent study by Tillement et al. [40] showed that as low as 0.1 pM of Aβ(1–42) decreased the mitochondrial respiratory coefficient (MRC: defined as V3/V4 where V3 is the O2 consumption after adding ADP and V4 is the basal O2 consumption) in mitochondria isolated from rat forebrain, suggesting that Aβ impairs oxidative phosphorylation. Moreira et al. [24,25] demonstrated that Aβ(1–40) (2 μM) and Aβ(25–35) (50 μM) can exacerbate calcium-dependent formation of the permeability transition pore (PTP), resulting in decreased mitochondrial transmembrane potential, decreased capacity to accumulate calcium, and uncoupling of respiration. Extensive studies have suggested that increased permeabilization of the mitochondrial membrane with subsequent release of cytochrome c is a key initiative step in the apoptotic process [14].

DEMONSTRATION OF INTRAMITOCHONDRIAL Aβ

Using mitochondria purified from cerebral cortices of transgenic mutant AβPP (Tg mAPP) mice (J20) [26], our group first demonstrated that Aβ progressively accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix, and that this was associated with diminished enzymatic activity of respiratory chain complexes III and IV, as well as a reduction in the rate of oxygen consumption. The time course for accumulation of Aβ in mitochondria was further assessed in animals from 4 to 24 months of age. The most rapid phase of Aβ accumulation appeared to be at 8–12 months of age. Both Aβ42 and Aβ40 are present within mitochondrial matrix, but the level of Aβ42 is considerably higher than Aβ40, as is true for intracelllular Aβ in other compartments. Intramitochondrial Aβ was first detectable at 4 months of age, before significant extracellular deposition of Aβ in the animal brain. Protease sensitivity assays further showed that a certain amount of Aβ peptide is also protected from protease digestion within the inner membrane compartment, suggesting that a significant amount of Aβ is present within mitochondrial matrix rather than simply adsorbed to the external mitochondrial surface [7]. Using another line of Tg mAPP mice (Tg2576), Manczak et al. also reported the presence of both Aβ40 and Aβ42 within mitochondria [23].

Morphologic studies provide further evidence of the presence of Aβ in mitochondria. Confocal microscopy demonstrated that Aβ co-localized with HSP60, a marker of mitochondrial matrix. Neurons in the cortex and hippocampus of Tg mAPP mice displayed an overlapping distribution of Aβ and HSP60 antigens. About 40% and 20% of mitochondria were stained with Aβ42 in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, respectively. In contrast, non-transgenic littermate controls showed no detectable Aβ42 antigen in the mitochondria [7].

The association between intramitochondrial Aβ and AD was further supported by data derived from postmortem AD samples versus non-demented control brains. Using brains harvested with a post-mortem time of 3.5 hours or less, we demonstrated the presence of intramitochondrial Aβ by immunogold staining in mitochondria purified from AD brain, but to a much lesser extent in non-demented control samples. Confocal microscopic analysis of double immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that 40% (temporal lobe tissues) and 70% (hippocampus) of the mitochondria from AD brain were co-stained with an antibody to Aβ versus 5% (temporal lobe) and 14% (hippocampus) from ND control [7].

Accumulation of intramitochondrial Aβ also leads to mitochondrial functional abnormalities. Although oxygen consumption was comparable at age 4 months in Tg mAPP mice and non-Tg littermates, by age 8 months there was a trend towards lower levels in Tg mAPP mice that achieved statistical significance by 12 months. Since changes in oxygen consumption could result from multiple defects in mitochondrial properties, we assessed the activity of key enzymes in respiratory chain complexes to localize possible sites of dysfunction. There were no significant differences in respiratory enzymatic activities between Tg mAPP mice and non-Tg littermates at 8 months of age. However, there was a significant decrease in the activity of succinate-cytochrome c reductase (complex III) and COX (complex IV) by the 10 month time point. These results indicate that accumulation of Aβ within mitochondria correlates temporally with changes in mitochondrial function at the level of oxygen consumption and activity of key enzymes in complexes III and IV of the respiratory chain [7].

The origin of intramitochondrial Aβ is far from certain. It has been established that intracellular Aβ is generated in the ER/Golgi compartment, multivesicular bodies, endosomal/lysomal system and the cell surface [8,15,16,18,21,34,37,39,43,45,46]. It is logical to presume that Aβ might gain access into the mitochondrial matrix by an intracellular trafficking mechanism with involvement of a specific transport mechanism on the mitochondrial membrane. However, with the recent localization of AβPP in mitochondria and the discovery of a mitochondrial protease system theoretically capable of generating Aβ, the possibility of in situ Aβ production within mitochondria needs to be further explored. The presence of AβPP in the mitochondrial membrane fraction in AD brain was initially observed by Yamaguchi et al. [48], though the nature of this association and the role of AβPP in mitochondrial functions were not investigated. Anandatheerthavarada et al. [1] demonstrated that three positively charged residues (Arg40, His44 and Lys55) in the N-terminal of AβPP were essential for mitochondrial targeting. The orientation of AβPP in mitochondria, based on cross-linking studies, seemed to show the molecule to be embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane in close association with mitochondrial translocase proteins, with the N-terminus facing the mitochondrialmatrix and C-terminus (about 73 kD) exposed in the cytosol. Thus, AβPP appears to be trapped in the mitochondrial membrane due to its acidic domain (residues 220 to 290). Park et al. [29] recently reported that HtrA2 (also known as Omi), a serine protease that localizes to the mitochondrial intermembrane space, can cleave AβPP and produce an insoluble C161 fragment encompassing amino acids 535-695 of AβPP 695. Although a relationship between the C161 fragment and the formation of Aβ within the mitochondria remains to be determined, these data suggest that mitochondria might also be a potential site for intracellular Aβ formation.

ABAD AS A MITOCHONDRIAL TARGET OF Aβ

Using the yeast two-hybrid system, our group identified a mitochondrial short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase, which specifically binds to Aβ. We initially termed this enzyme as ERAB (endoplasmic reticulum-associated Aβ-binding protein) and later changed its name to Aβ binding alcohol dehydrogenase (ABAD) to reflect its mitochondrial location, ability to bind Aβ and potential role in mediating Aβ toxicity. ABAD is a 261 amino acid mitochondrial enzyme encoded by HADH2 (MIM: 300256; GeneID: 3028) gene located on chromosome Xp11.2. In vitro binding studies demonstrated that Aβ peptides (1–42, 1–40, and 1–20) bind to ABAD in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, the C-terminal portion of Aβ(25–35) does not bind to ABAD, suggesting that Aβ might bind to ABAD via its N-terminus, thereby leaving the C-terminus free to multimerize with additional Aβ. Further, our recent studies have demonstrated that oligomeric Aβ binds to ABAD [47,51]. Immunoprecipitation of the AD brain further showed that ABAD and Aβ form a complex in brain homogenates and mitochondrial extracts [22]. These data suggest the significance of ABAD in the pathogenesis of AD.

High-resolution crystallography of Aβ-ABAD complex demonstrated a considerable distortion of ABAD structure upon binding to Aβ [22]. Specifically, the NAD cofactor was excluded from the structure due to Aβ binding. Aβ binding induced multiple structural changes in the loops of ABAD (LD, LE, LF) whose orientation is important for ABAD activity. Comparison of the amino acid sequence of ABAD to other enzymes within this family showed an 11 amino acid insertion in the LD loop that is unique to ABAD, suggesting the possibility that this might be a site mediating the binding to Aβ. To determine whether the LD loop is sufficient for Aβ interaction, a peptide encompassing this region (residues 92-120), termed ABAD decoy peptide (ABAD-DP) was tested by surface plasmon resonance for its ability to inhibit the interaction of full length ABAD with Aβ. ABAD-DP did inhibit the binding of Aβ40 and Aβ42 to full-length ABAD with inhibitory constants of 4.9 and 1.7 μM respectively, whereas peptide with reversed sequence (ABAD-RP) was inactive. These data indicate that LD loop of ABAD is critical for Aβ binding to ABAD [22].

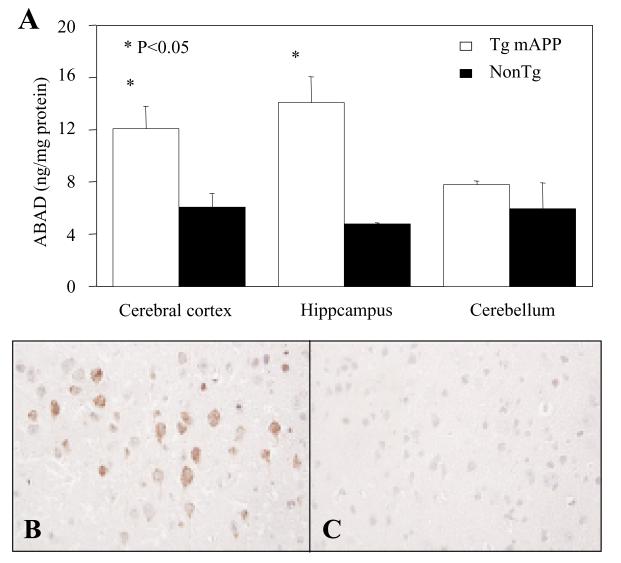

As an ubiquitously expressed mitochondrial enzyme with its highest expression level in heart and liver, the expression of ABAD in temporal lobe was increased in AD brains as compared to age-matched normal control [49]. This result was further confirmed when additional 19 AD tissues with post-mortem time less than 3 hours were compared to 15 non-dementia controls with similar post-mortem time. The ABAD antigen levels in AD brains were increased by ~28% and ~40% in either inferior temporal gyrus or hippocampus respectively, as compared to the non-demented controls. The increased ABAD level paralleled with an increase of specific mRNA transcript as demonstrated by In situ hybridization [22]. The discrepant data were reported by Frackowiak et al. finding no immunoreactivity for HADH (ABAD) in AD cortex, leptomeninges and white matter [10]. Although the reason for this apparent discrepancy remains unclear, the unspecified postmortem time in the latter study might be one of the contributing factors consideringthe vulnerabilityof ABAD to post-mortem degradation. Expression of ABAD in the hippocampus and cortex was also increased in the Tg mAPP mice (J20) by 4–5 months of age, following the rise of Aβ which occurs at 2–4 months of age. Increased levels of ABAD were observed in the hippocampus (~3-fold) and cortex (~2-fold) but not in cerebellum, as compared with non transgenic littermates by ELISA (Fig. 1). To analyze the subcellular localization of ABAD, immunogold electron microscopy was employed to study brains of transgenic mice. At 8–12 months of age, the increased ABAD is predominately localized in mitochondria of neurons, though it was also found in astrocytes, and, occasionally, in peripheral amyloid fibrils. ABAD was not detected in the nucleolus or nuclear heterochromatin as reported in Tg2576 mouse. Despite difference in the expression patterns, a significantly increased expression of ABAD in the brain was demonstrated in both strains of AD-type murine models, the J20 mice in our laboratory and the Tg2576 mice as previously reported [19,44]. In vitro studies demonstrated that addition of micromolar levels of synthetic Aβ40 to purified or recombinant ABAD inhibited its enzymatic activity in terms of reduction of S-acetoactyl-CoA (Ki≈1.6 μM), oxidation of 17β-estradiol (Ki≈1.6 μM) and (−)-2-octanol (Ki≈2.6 μM) [50]. Point mutations of ABAD have been associated with an inborn metabolic disorder of 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (MHBD) deficiency. Children affected by MHBD deficiency present a clinical picture of progressive loss of mental and motor function starting within the first year of life [13,28,36,52]. Since MHBD is an important enzyme in isoleucine metabolism, MHBD-deficient patients suffer from lactic acidosis accompanied by increased urinary excretion of 2-methyl-3-hydrobutyrate (MHB) and tiglyglycine (TG). A reductionof respiratory chain complex I and IV activity was demonstrated in the skeletal muscle samples derived from patients with MHBD deficiency [3,9,28]. Studies using rat cerebral cortex tissue have shown that MHB at 0.01 mmol/L and higher concentrations can inhibit CO2 production from glucose, acetate and citrate, indicating inhibitory effects on the citric acid cycle, and also showing specific inhibition of respiratory chain complex IV activity [3]. Based on these data, we suspect that intramitochondrial Aβ might exert its inhibitory effects on mitochondrial metabolism through inhibiting ABAD activity and accumulation of certain intermediate metabolites, such as MHB.

Fig. 1.

Expression of ABAD in transgenic mutant AβPP (Tg mAPP) mice. Analysis of ABAD antigen in various brain regions by ELISA in Tg mAPP mice vs. non-transgenic (NonTg) littermates is shown in panel A. The micrographs demonstrate immunostaining of ABAD in cerebral cortex of Tg mAPP mouse (B) and NonTg control (C).

A more readily observed effect of ABAD in AD pathology is enhanced Aβ-induced neuronal stress. Initial in vitro studies showed that over-expression of ABAD enhanced Aβ-induced cell stress and cytotoxicity and that intracellular introduction of anti-ABAD F(ab’)2 blocked the cytotoxic effect of Aβ [49]. Further, antagonizing ABAD/Aβ interaction protects against neuronal and mitochondrial toxicity induced by Aβ. Addition of ABAD decoy peptide (ABAD-DP) to cultured mouse cortical neurons prevented Aβ-induced mitochondrial cytochrome c release, DNA fragmentation, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release and generation of ROS, while the control peptide with reverse sequence (ABAD-RP) has no such effects. Consistent with the results of these in vitro studies, transgenic mice with targeted neuronal expressionof ABAD and mutant AβPP (Tg mAPP/ABAD) exhibited enhanced mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunction,as well as impaired behavioral and synaptic function. Electron paramagnetic spin resonance (EPR) spectroscopic measurement of ROS in frozen mouse brain showed higher amounts of free radicals, as shown by a sharp peak at 3410 G, in samples from Tg mAPP/ABAD mice compared to controls. It was believed that this species of free radical, which arise from ascorbyl or the one-electron reduced ubiquinone radical, is generated as a result of higher levels of oxidative stress in Tg mAPP/ABAD, as compared to the mice of non-Tg, Tg mAPP, or Tg ABAD genotypes. The radial-arm water maze test was used to detect learning and memory deficits in Tg mAPP/ABAD mice. At 5 months of age, control mice of non-Tg, Tg mAPP, or Tg ABAD genotypes all showed intact learning and memory capacity. In contrast, Tg mAPP/ABAD mice at this age demonstrated severe impairment in spatial learning and memory [22]. Further study by Takuma et al. [38] showed that neuronal culture from Tg mAPP/ABAD mice displays spontaneous generation of ROS, decreased ATP production, decreased COX activity, release of cytochrome c from mitochondria with subsequent induction of caspase-3-like activity followed by DNA fragmentation and loss of cell viability. The brains of Tg mAPP/ABAD mice displayed reduced levels of brain ATP and COX activity as well as diminished glucose utilization. Measuring field-excitatory postsynaptic potential (fEPSPs) in the CA1 stratum radiatum revealed an impairment of basal synaptic transmission (BST) in 8- to 10-month-old Tg mAPP/ABAD and Tg mAPP mice, as compared to single Tg ABAD and non-Tg littermates. Long-term potential (LTP) was most severely affected in Tg mAPP/ABAD mice as compared with the other groups. These results provide support for the hypothesis that ABAD serves as a cellular cofactor promoting and amplifying Aβ-mediated mitochondrial toxicity and leading to neuronal and synaptic stress in an Aβ-rich environment relevant to AD pathogenesis. This pathogenic mechanism might involve other mitochondrial enzymes as implicated by the recent identification that Aβ can also bind C-terminal peptide domain of NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 3 (complex I, ND3) encoded by mitochondrial DNA genome [27], although the role for this interaction requires further investigation.

CONCLUSION

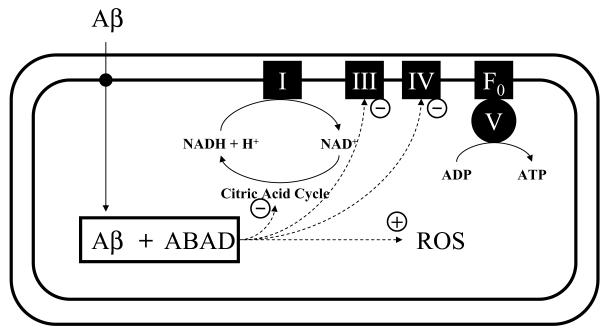

Mitochondrial dysfunction in AD presents as defects of citric acid cycle enzymes, diminished activity of complexes III/IV of the respiratory chain and enhanced ROS production. Progressive accumulation of Aβ within the mitochondrial matrix might be an important underlying mechanism for Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Our recent data suggest that intracellular-derived Aβ may gain access to the mitochondrial matrix and specifically bind to ABAD, as depicted in Fig. 2. Interaction between Aβ and ABAD induces mitochondrial cytochrome c release, DNA fragmentation, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release and generation of ROS in cortical neurons. These changes closely correlate with hippocampal and neurophysiological impairment and learning and memory deficiency demonstrated in the transgenic AD-type mouse models. These results suggest that interception of ABAD/Aβ interaction may be a potential therapeutic approach for AD.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of intramitochondrial trafficking of Aβ and the consequences of interactions between Aβ and ABAD. I, III, IV, V and F0 denote respiratory chain complexes at mitochondrial inner membrane; + denotes enhancing effect and – denotes inhibitory effect.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (National Institute on Aging, AG16736, PO1 AG17490, and P50 AG08702), and the Alzheimer’s Association.

References

- [1].Anandatheerthavarada HK, Biswas G, Robin MA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial targeting and a novel transmembrane arrest of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein impairs mitochondrial function in neuronal cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:41–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bubber P, Haroutunian V, Fisch G, Blass JP, Gibson GE. Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:695–703. doi: 10.1002/ana.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burlina AB, Gibson KM, Ruitenbeek W, Bonafe L, Bennett MJ. Profound neurological phenotype in a patient presenting with disordered isoleucine and energy metabolism. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:864–866. doi: 10.1023/a:1005426920116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Butterfield DA, Perluigi M, Sultana R. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease brain: new insights from redox proteomics. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;545:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Butterworth RF, Besnard AM. Thiamine-dependent enzyme changes in temporal cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Metab Brain Dis. 1990;5:179–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00997071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Casley CS, Canevari L, Land JM, Clark JB, Sharpe MA. Beta-amyloid inhibits integrated mitochondrial respiration and key enzyme activities. J Neurochem. 2002;80:91–100. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Caspersen C, Wang N, Yao J, Sosunov A, Chen X, Lustbader JW, Xu HW, Stern D, McKhann G, Yan SD. Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential focal point for neuronal metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Faseb J. 2005;19:2040–2041. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cook DG, Forman MS, Sung JC, Leight S, Kolson DL, Iwatsubo T, Lee VM, Doms RW. Alzheimer’s A beta(1-42) is generated in the endoplasmic reticulum/intermediate compartment of NT2N cells. Nat Med. 1997;3:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ensenauer R, Niederhoff H, Ruiter JP, Wanders RJ, Schwab KO, Brandis M, Lehnert W. Clinical variability in 3-hydroxy-2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:656–659. doi: 10.1002/ana.10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Frackowiak J, Mazur-Kolecka B, Kaczmarski W, Dickson D. Deposition of Alzheimer’s vascular amyloid-beta is associated with decreased expression of brain L-3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase (ERAB) Brain Res. 2001;907:44–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gibson GE, Sheu KF, Blass JP. Abnormalities of mitochondrial enzymes in Alzheimer disease. J Neural Transm. 1998;105:855–870. doi: 10.1007/s007020050099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gibson GE, Zhang H, Sheu KF, Bogdanovich N, Lindsay JG, Lannfelt L, Vestling M, Cowburn RF. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in Alzheimer brains bearing the APP670/671 mutation. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:676–681. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gibson KM, Burlingame TG, Hogema B, Jakobs C, Schutgens RB, Millington D, Roe CR, Roe DS, Sweetman L, Steiner RD, Linck L, Pohowalla P, Sacks M, Kiss D, Rinaldo P, Vockley J. 2-Methylbutyryl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase deficiency: a new inborn error of L-isoleucine metabolism. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:830–833. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200006000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Multiple pathways of cytochrome c release from mitochondria in apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gouras GK, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Greenfield JP, Tsai J, Gouras GK, Hai B, Thinakaran G, Checler F, Sisodia SS, Greengard P, Xu H. Endoplasmic reticulum and trans-Golgi network generate distinct populations of Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:742–747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hartmann T, Bieger SC, Bruhl B, Tienari PJ, Ida N, Allsop D, Roberts GW, Masters CL, Dotti CG, Unsicker K, Beyreuther K. Distinct sites of intracellular production for Alzheimer’s disease A beta40/42 amyloid peptides. Nat Med. 1997;3:1016–1020. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].He XY, Wen GY, Merz G, Lin D, Yang YZ, Mehta P, Schulz H, Yang SY. Abundant type 10 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the hippocampus of mouse Alzheimer’s disease model. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;99:46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kish SJ, Mastrogiacomo F, Guttman M, Furukawa Y, Taanman JW, Dozic S, Pandolfo M, Lamarche J, DiStefano L, Chang LJ. Decreased brain protein levels of cytochrome oxidase subunits in Alzheimer’s disease and in hereditary spinocerebellar ataxia disorders: a nonspecific change? J Neurochem. 1999;72:700–707. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Koo EH, Squazzo SL. Evidence that production and release of amyloid beta-protein involves the endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17386–17389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, Xu HW, Takuma K, Wang N, Caspersen C, Chen X, Pollak S, Chaney M, Trinchese F, Liu S, Gunn-Moore F, Lue LF, Walker DG, Kuppusamy P, Zewier ZL, Arancio O, Stern D, Yan SS, Wu H. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2004;304:448–452. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manczak M, Anekonda TS, Henson E, Park BS, Quinn J, Reddy PH. Mitochondria are a direct site of A beta accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: implications for free radical generation and oxidative damage in disease progression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moreira PI, Santos MS, Moreno A, Oliveira C. Amyloid beta-peptide promotes permeability transition pore in brain mitochondria. Biosci Rep. 2001;21:789–800. doi: 10.1023/a:1015536808304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Moreira PI, Santos MS, Moreno A, Rego AC, Oliveira C. Effect of amyloid beta-peptide on permeability transition pore: a comparative study. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:257–267. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1-42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Munguia ME, Govezensky T, Martinez R, Manoutcharian K, Gevorkian G. Identification of amyloid-beta 1-42 binding protein fragments by screening of a human brain cDNA library. Neurosci Lett. 2006;397:79–82. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Olpin SE, Pollitt RJ, McMenamin J, Manning NJ, Besley G, Ruiter JP, Wanders RJ. 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency in a 23-year-old man. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:477–482. doi: 10.1023/a:1021251202287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Park HJ, Kim SS, Seong YM, Kim KH, Goo HG, Yoon EJ, Mindo S, Kang S, Rhim H. Beta-amyloid precursor protein is a direct cleavage target of HtrA2 serine protease. Implications for the physiological function of HtrA2 in the mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34277–34287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Parker WD, Jr., Filley CM, Parks JK. Cytochrome oxidase deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1302–1303. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Parker WD, Jr., Parks JK. Cytochrome c oxidase in Alzheimer’s disease brain: purification and characterization. Neurology. 1995;45:482–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Perry EK, Perry RH, Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Gibson PH. Coenzyme A-acetylating enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease: possible cholinergic ‘compartment’ of pyruvate dehydrogenase. Neurosci Lett. 1980;18:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Shearman MS, Ragan CI, Iversen LL. Inhibition of PC12 cell redox activity is a specific, early indicator of the mechanism of beta-amyloid-mediated cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1470–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sisodia SS, Koo EH, Beyreuther K, Unterbeck A, Price DL. Evidence that beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease is not derived by normal processing. Science. 1990;248:492–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1691865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sorbi S, Bird ED, Blass JP. Decreased pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in Huntington and Alzheimer brain. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:72–78. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sutton VR, O’Brien WE, Clark GD, Kim J, Wanders RJ. 3-Hydroxy-2-methylbutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2003;26:69–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1024083715568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Takahashi RH, Milner TA, Li F, Nam EE, Edgar MA, Yamaguchi H, Beal MF, Xu H, Greengard P, Gouras GK. Intraneuronal Alzheimer abeta42 accumulates in multivesicular bodies and is associated with synaptic pathology. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64463-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Takuma K, Yao J, Huang J, Xu H, Chen X, Luddy J, Trillat AC, Stern DM, Arancio O, Yan SS. ABAD enhances Abeta-induced cell stress via mitochondrial dysfunction. Faseb J. 2005;19:597–598. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2582fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tienari PJ, Ida N, Ikonen E, Simons M, Weidemann A, Multhaup G, Masters CL, Dotti CG, Beyreuther K. Intracellular and secreted Alzheimer beta-amyloid species are generated by distinct mechanisms in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4125–4130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Tillement L, Lecanu L, Yao W, Greeson J, Papadopoulos V. The spirostenol (22R, 25R)-20alpha-spirost-5-en-3beta-yl hexanoate blocks mitochondrial uptake of Abeta in neuronal cells and prevents Abeta-induced impairment of mitochondrial function. Steroids. 2006;71:725–735. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Valla J, Berndt JD, Gonzalez-Lima F. Energy hypometabolism in posterior cingulate cortex of Alzheimer’s patients: superficial laminar cytochrome oxidase associated with disease duration. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4923–4930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04923.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Weggen S, Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Pietrzik CU, Ozols V, Fauq A, Golde TE, Koo EH. Evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs decrease amyloid beta 42 production by direct modulation of gamma-secretase activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31831–31837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wen GY, Yang SY, Kaczmarski W, He XY, Pappas KS. Presence of hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 10 in amyloid plaques (APs) of Hsiao’s APP-Sw transgenic mouse brains, but absence in APs of Alzheimer’s disease brains. Brain Res. 2002;954:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03354-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wild-Bode C, Yamazaki T, Capell A, Leimer U, Steiner H, Ihara Y, Haass C. Intracellular generation and accumulation of amyloid beta-peptide terminating at amino acid 42. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16085–16088. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wilson CA, Doms RW, Lee VM. Intracellular APP processing and A beta production in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:787–794. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Xie Y, Deng S, Chen Z, Yan S, Landry DW. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of the Abeta-ABAD interaction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:4657–4660. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Yamaguchi H, Yamazaki T, Ishiguro K, Shoji M, Nakazato Y, Hirai S. Ultrastructural localization of Alzheimer amyloid beta/A4 protein precursor in the cytoplasm of neurons and senile plaque-associated astrocytes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1992;85:15–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00304629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yan SD, Fu J, Soto C, Chen X, Zhu H, Al-Mohanna F, Collison K, Zhu A, Stern E, Saido T, Tohyama M, Ogawa S, Roher A, Stern D. An intracellular protein that binds amyloid-beta peptide and mediates neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1997;389:689–695. doi: 10.1038/39522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yan SD, Shi Y, Zhu A, Fu J, Zhu H, Zhu Y, Gibson L, Stern E, Collison K, Al-Mohanna F, Ogawa S, Roher A, Clarke SG, Stern DM. Role of ERAB/L-3-hydroxyacylcoenzyme A dehydrogenase type II activity in Abeta-induced cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2145–2156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yan SD, Chen X, Arancio O, Lustbader J, Wu H. ABAD: Mitochondrial Target for Abeta-mediated cellular perturbation in Alzheimer Disease. In: Sun M, editor. Research Progress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zschocke J, Ruiter JP, Brand J, Lindner M, Hoffmann GF, Wanders RJ, Mayatepek E. Progressive infantile neurodegeneration caused by 2-methyl-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: a novel inborn error of branched-chain fatty acid and isoleucine metabolism. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:852–855. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200012000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]