Abstract

Background

The transcription factor cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein (CREB) orchestrates diverse neurobiological processes including cell differentiation, survival, and plasticity. Alterations in CREB-mediated transcription have been implicated in numerous central nervous system (CNS) disorders including depression, anxiety,addiction,and cognitive decline. However, it remains unclear how CREB contributes to normal and aberrant CNS function, as the identity of CREB-regulated genes in brain and the regional and temporal dynamics of CREB function remain largely undetermined.

Methods

We combined microarray and chromatin immunoprecipitation technology to analyze CREB-DNA interactions in brain. We compared the occupancy and activity of CREB at gene promoters in rat frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum before and after a rodent model of electroconvulsive therapy.

Results

Our analysis identified >860 CREB binding sites in rat brain. We identified multiple genomic loci enriched with CREB binding sites and find that CREB-occupied transcripts interact extensively to promote cell proliferation, plasticity, and resiliency. We discovered regional differences in CREB occupancy and activity that explain, in part, the diverse biological and behavioral outputs of CREB activity in frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum. Electroconvulsive seizure rapidly increased CREB occupancy and/or phosphorylation at select promoters, demonstrating that both events contribute to the temporal regulation of the CREB transcriptome.

Conclusions

Our data provide a mechanistic basis for CREB’s ability to integrate regional and temporal cues to orchestrate state-specific patterns of transcription in the brain, indicate that CREB is an important mediator of the biological responses to electroconvulsive seizure, and provide global mechanistic insights into CREB’s role in psychiatric and cognitive function.

Keywords: cAMP, chromatin immunoprecipitation, CREB, electroconvulsive seizure, microarray, transcription

The cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein (CREB) is a widely expressed, activity-regulated transcription factor that functions in a variety of physiological processes (1). In the central nervous system (CNS), CREB is a key modulator of development, plasticity, circadian entrainment, neuroprotection, and resiliency (2). Alterations in CREB-mediated transcription have been implicated in multiple cognitive and psychiatric disorders including depression, anxiety, addiction, and cognitive decline (3). For example, CREB activity is decreased in the brains of depressed patients, is upregulated by a wide variety of antidepressants, and produces antidepressant effects in rodent hippocampus (3).

CREB responds to diverse neurological inputs producing an equally diverse set of spatially and temporally regulated outputs. For example, CREB facilitates learning and memory in the frontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala; regulates addictive behavior in the locus coeruleus and nucleus accumbens; mediates antidepressant efficacy in the hippocampus; and precipitates depressive behavior in the nucleus accumbens (2,3). While it is unclear how CREB selectively regulates these varied outputs, two explanations have been proposed (2). First, specific functional outcomes may be achieved by regulating CREB within specific neuronal circuits. Second,patterns of CREB-mediated gene transcription may be stimulus, region, and temporally specific.

CREB preferentially binds to the cAMP response element (CRE) palindrome, TGACGTCA. However, CREB can also bind to variations of the CRE palindrome, and many CREB-regulated promoters contain the half CRE site TGACG or multiple substitutions (1,4,5). By combining chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with high-throughput analysis platforms such as microarrays (ChIP-chip), recent studies have identified several thousand CREB binding sites in cell lines (5–7). However, these studies or CRE prediction algorithms cannot be directly extrapolated to brain or other tissues, as CRE functionality is controlled by epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation (5,8–11). To date, only a small number of the CREB binding sites have been experimentally confirmed in brain or other tissues (3).

Acute control over CREB activity is generally thought to result from regulatory phosphorylation and not dynamic changes in CREB binding, despite several reports demonstrating rapid changes in CREB occupancy at isolated promoters (12–14). Multiple kinases phosphorylate CREB Ser-133 in response to extracellular stimuli including growth factors, depolarization, synaptic activity, hypoxia, stress, drugs of abuse, light, learning tasks, chemical antidepressants, and electroconvulsive seizure (ECS) (2). Distinct patterns of CREB target gene expression have been observed following CREB phosphorylation by various stimuli, indicating that additional, yet undetermined mechanisms contribute specificity to the temporal regulation of CREB-mediated gene transcription (5,15). Determining the regional and temporal dynamics of the CREB regulon in brain tissue thus remains a critical hurdle for a molecular understanding of the large body of literature demonstrating the importance of CREB in neurobiology and behavior.

Methods and Materials

Complete, unabridged protocols are given in Supplement 1.

ECS Treatment

Male Sprague Dawley rats (100–120 g) were administered sham or ECS treatment as described (16,17). Brains were quickly removed 15 min after ECS or sham treatment, and regions were manually dissected and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve time point consistency. The freeze-thaw step had no effect on ChIP efficacy or specificity, as confirmed both by real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and microarray analysis comparing flash-frozen and nonfrozen tissue.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed as described with several modifications (18,19). Briefly, chromatin isolated from 10 mg tissue was sonicated into 200 to 500 base pair (bp) fragments (Figure 2B). Resulting samples were immunoprecipitated with 4 (µg total CREB antibody (Upstate #06863; Upstate, Ithaca, New York), 2 µg phospho-Ser-133 CREB (pCREB) antibody (Upstate #06519), or 5 µg normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma I8140; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri).

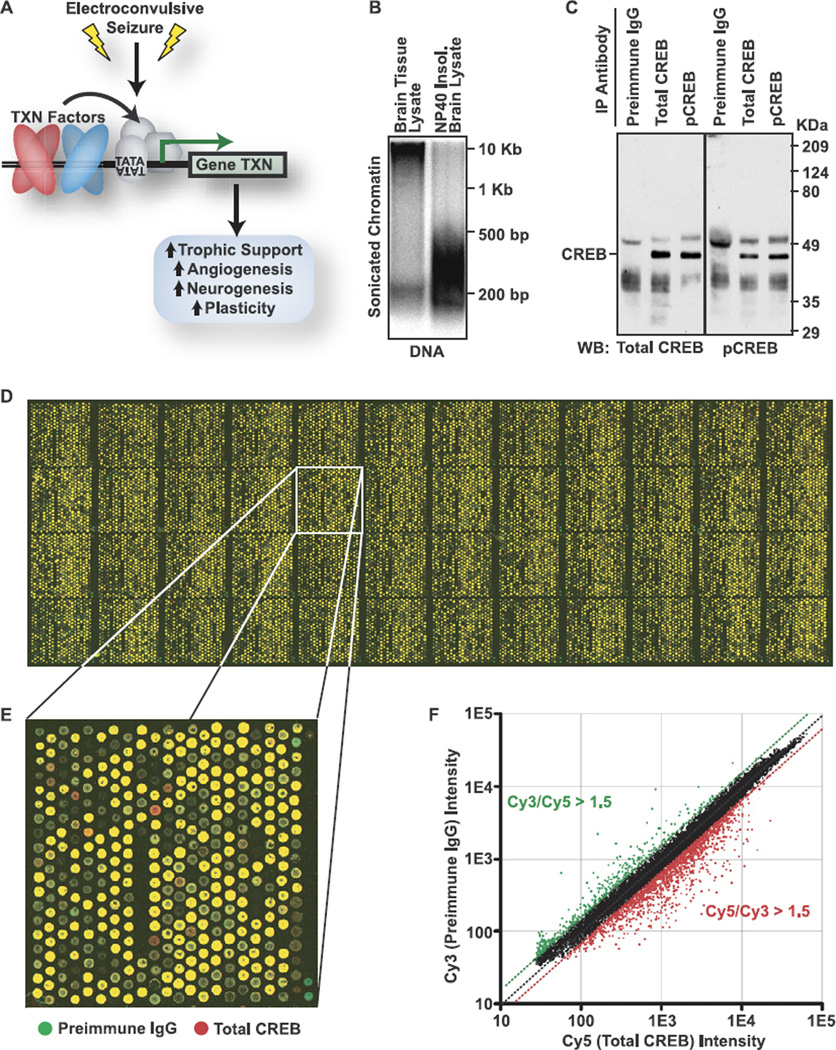

Figure 2.

ChIP-chip analysis of CREB occupancy in brain. (A) Diagram of the biological responses to ECS. ECS activates gene transcription (TXN) to support cell proliferation, growth, and plasticity. (B) Whole brain tissue lysateor the Nonidet-P40 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) insoluble nuclear fraction of whole brain (used for ChIP) was sonicated 20×. Crosslinks were reversed and DNA purified prior to resolving by electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide. Whole brain lysates were resistant to shearing; isolated nuclei were consistently sheared into 200 to 500 bp fragments. (C) Whole brain chromatin immunoprecipitated with preimmune IgG, total CREB, or pCREB antibodies; resolved by SDS-PAGE; and immunoblotted using the same total CREB (left panel) or pCREB (right panel) antibodies. (D) Representative image of the BCBC 18K promoter array. For example shown, amplified preimmune IgG and total CREB ChIP product from frontal cortex were labeled with Cy3 (green) and Cy5 (red), respectively. (E) One grid of the array in (D). (F) Scatter plot of Cy3:Cy5 ratios for array in (D). Green = Cy3/Cy5 ratios > 1.5. Red = Cy5/Cy3 >1.5 indicating sequences enriched by total CREB ChIP relative to preimmune IgG ChIP. BCBC, Beta Cell Biology Consortium; bp, base pair; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; Cy3, cyanine 3; Cy5, cyanine 5; ECS, electroconvulsive seizure; IgG, immunoglobulin G; pCREB, phospho-Ser-133 CREB; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Western Blot Analysis

Chromatin recovered by total CREB or pCREB immunoprecipitation from whole brain was resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with the same total CREB (1:1000) or pCREB (1:1000) antibodies (Upstate #06863 and #06519).

Quantitative PCR

Real time PCR analysis was performed using a Cepheid Smartcycler (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California), Qiagen Quantitect SYBR Green PCR mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 1/25th of the unamplified ChIP product recovered from 10 mg tissue. Supplement 3 lists all primer sequences used.

Amplification of ChIP DNA and Microarray Analysis

Immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified to linear phase by ligation-mediated PCR as described (20). Amplified DNA was labeled using Genisphere’s DNA900 labeling system (Genisphere, Hatfield, Pennsylvania) and hybridized as described fully in Supplement 1. Microarrays from the Beta Cell Biology Consortium (BCBC; Nashville, Tennessee) contained 1 kilobase (kb) sequences immediately upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of 12,000 mouse genes and 2 kb sequences from 3 kb to 1 kb upstream of the TSS for half of the represented genes (www.betacell.org). Although the use of rat samples on this array could result in some false negatives/positives, the vast majority of rat promoters efficiently and specifically hybridize to the mouse array, as the promoters of these species average 85% identity (Figure 2D and Supplement 4) (21).

Mean cyanine 3 (Cy3)/cyanine 5(Cy5) ratios from six independent animal/ChIP/array replicates were calculated using GenePix Pro 6.0 Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, California) and Genespring 7.2 (Agilent, Santa Clara, California) following intensity-dependent Lowess normalization. See Supplements 10–15 for complete data set.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Network analysis was performed using GeneGo (Metacore, Kanata, Ontario, Canada). Gene classification was performed using the Compare Classifications of Lists function of the Panther Classification System (www.pantherdb.org, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California). Rat chromosomal positions of CREB targets were mapped using the Ensembl genome browser (v40, August 2006; http://www.ensembl.org/index.html). TRANSFAC v7.4 was used (Biobase, Wolfenbüttel, Germany).

Results

Analysis of CREB Functional Activity in Brain Tissue

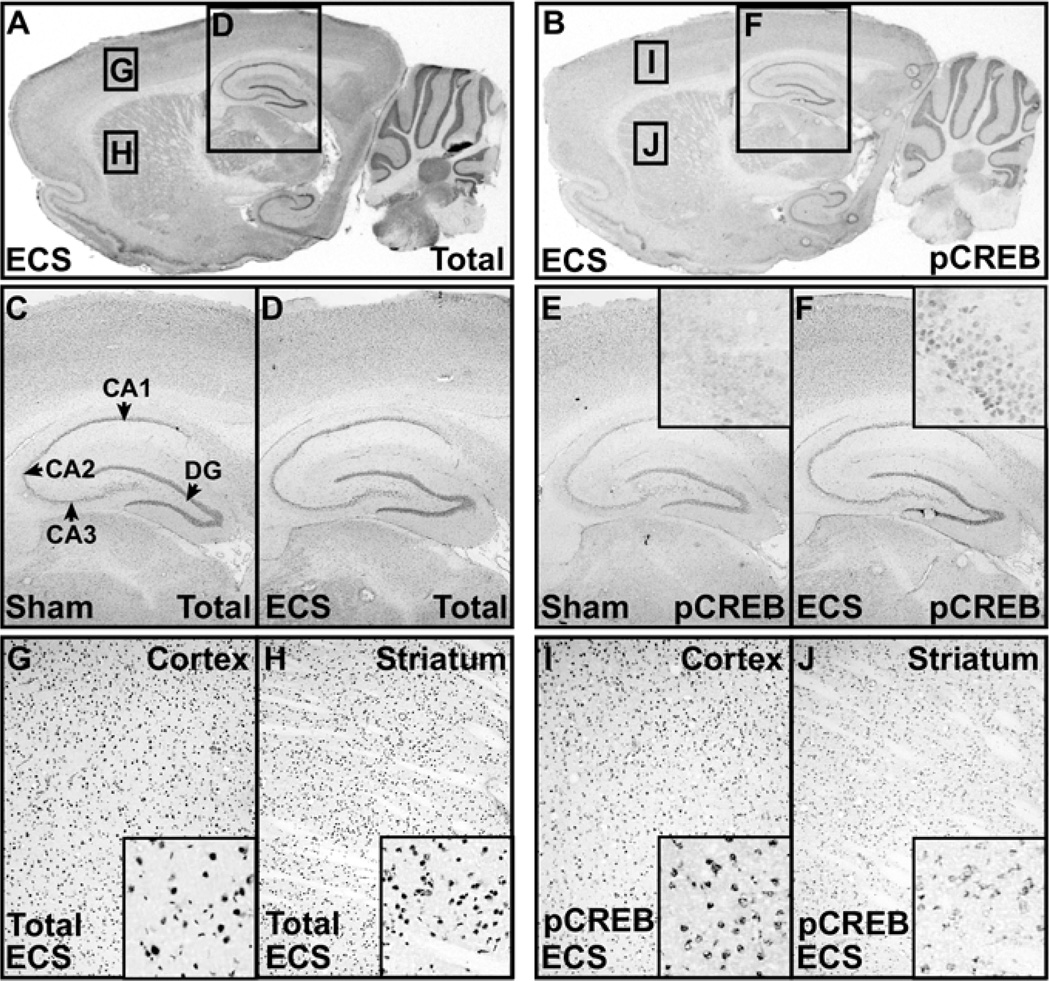

To determine the regional specificity of CREB activity, we analyzed CREB expression, promoter occupancy, and phosphorylation in rat frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum, regions that control diverse processes including learning, cognition, mood, motivation, and reward (3). To examine the temporal dynamics of CREB activity in these regions, we used ECS, a potent CREB stimulus and antidepressant therapy in humans (Figures 1, 2A) (22,23). No difference in total CREB immunoreactivity was observed within 15 minutes of acute ECS (Figure 1C, D). However, pCREB immunoreactivity was consistently elevated in the dentate gyrus in hippocampus of ECS treated rats (Figure 1E, F), consistent with immunoblot studies of whole hippocampus (22). Electroconvulsive seizure-induced increases in pCREB were most pronounced in the subventricular zone, as observed previously with chemical antidepressants (24). This analysis did not detect significant differences in other brain regions following ECS but did detect less pCREB reactivity in the striatum than in cortex regardless of sham or ECS treatment, even though these regions exhibited similar patterns and levels of total CREB immunoreactivity (Figure 1G–J).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemistry of CREB expression and phosphorylation in brain. (A,B) Total CREB (A) and pCREB (B) immunohistochemistry performed on 14 µm cryocut ECS treated rat brains. Boxes indicate regions magnified in (D), (G), (H), (F), (I), (J). (C,D) Total CREB immunoreactivity 15 min after sham handling (C) or ECS (D). (E,F) pCREB immunoreactivity 15 min after sham handling (E) or ECS (F). Insets show magnified views of the top blade of the DG. (G,H) Magnified images of the total CREB immunoreactivity in the cortical (G)and striatal (H) regions boxed in (A). (I,J) Magnified images of the pCREB immunoreactivity in the cortical (I) and striatal (J) regions boxed in (B). CA, cornu ammonis; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; DG, dentate gyrus; ECS, electroconvulsive seizure; pCREB, phospho-Ser-133 CREB.

To determine CREB occupancy and phosphorylation status at specific genomic elements, we developed protocols to extend the use of ChIP-chip to brain tissue (Supplements 1 and 5). Fifteen minutes after sham or ECS treatment, rat frontal cortex, hippocampus, or striatum was rapidly dissected and cross-linked to preserve protein-DNA interactions. Chromatin was extracted and consistently sheared into fragments averaging 200 to 500 bp (Figure 2B). Sheared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with either the total CREB or pCREB antibodies used for immunohistochemistry or with preimmune IgG to control for background. The efficacy and specificity of the total CREB antibody for ChIP have been previously demonstrated (7). We further assessed the immunoprecipitation (IP) specificity of both antibodies by immunoblotting ChIP products recovered from whole brain (Figure 2C). A single band, corresponding to p43 CREB-1, was observed above background IgG bands when total CREB or pCREB ChIP products were immunoblotted with the same antibodies.

For microarray analysis, co-immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified to linear phase by real time ligation-mediated PCR, and microarray signal was passively enhanced using fluorescent dendrimers (Supplements 1 and 5). This limited amplification protocol maintained quantitative differences in ChIP samples, allowing reproducible detection of 1.2-fold differences in ChIP samples. Samples were analyzed using an array containing 24 megabase (Mb) of murine genomic sequence immediately upstream of the TSS of 12,000 genes (Figure 2D–F). Complete details on the array platform, hybridization, and analyses are given in Supplement 1. The complete data set is given in Supplements 10–15. For excellent discussions on this technology, its advantages and limitations, see Sikder and Kodacek (25) and Hanlon and Lieb (26).

Identification of CREB Occupied Promoters in Brain

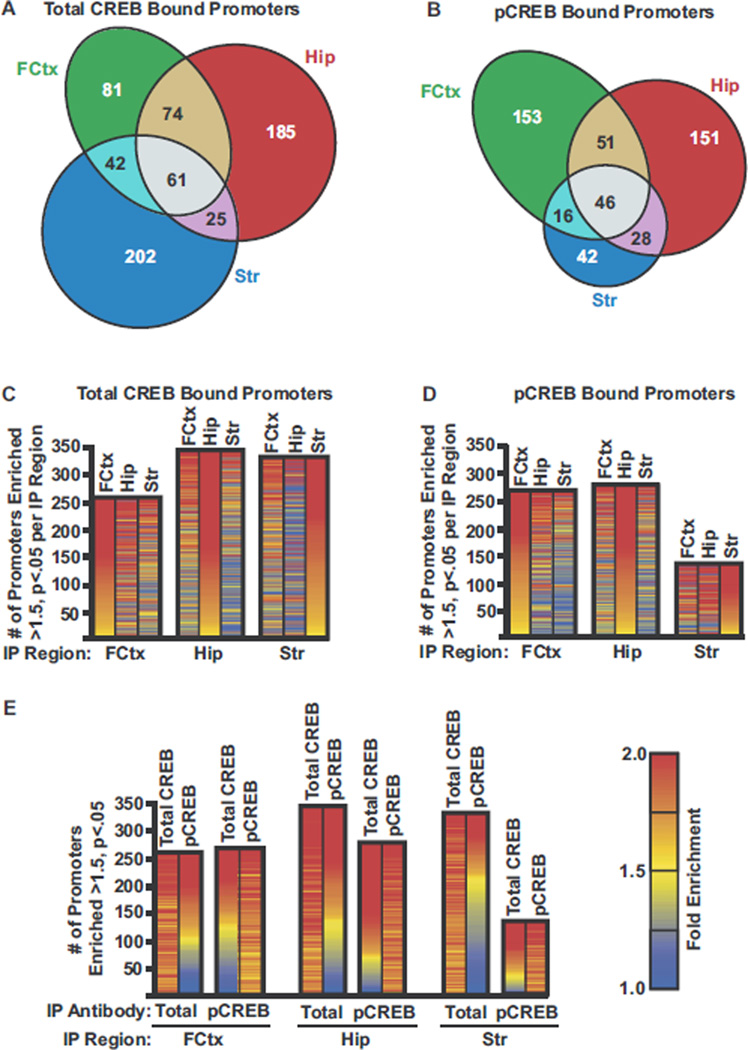

We first compared preimmune IgG ChIPs (Cy3) with total CREB or pCREB ChIPs (Cy5) from ECS treated rats (Figures 2E, F and 3). The Cy5/Cy3 ratios from six independent animal/ChIP/ array replicates were analyzed on a per-spot, per-array basis. Total CREB and pCREB bound sequences were identified with high statistical and biological confidence by selecting for mean Cy5/Cy3 ratios of >1.5, Student t test p values of <.05, and statistical analysis of microarrays (SAM) false discovery rates (FDR) of less than 5% (27,28). In frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum of ECS treated rats, this analysis identified 258, 345, and 330 promoter sequences occupied by total CREB, respectively, and 266, 276, and 132 promoter sequences occupied by pCREB, respectively (Figure 3; Supplements 6 and 7).

Figure 3.

Identification of CREB bound promoters in hippocampus, frontal cortex, and striatum. (A,B) Venn diagrams showing the number and overlap of promoter sequences enriched (>1.5-fold, p< .05, SAM FDR <5%, n = 6) from frontal cortex (Fctx), hippocampus (Hip), and striatum (Str) of ECS treated rats by total CREB ChIP (A) or pCREBChIP (B) relative to preimmune IgG ChIP. (C,D) Bar graphs show number of sequences enriched (> 1.5-fold, p< .05, SAM FDR < 5%, n = 6) by total CREB (C) or pCREB (D) ChIP relative to preimmune IgG IP from Fctx, Hip, or Str of ECS treated rats. Inside each bar are three heat maps that compare mean enrichment values (total CREB or pCREB ChIP versus preimmune IgG) obtained from frontal cortex (left map), hippocampus (middle map), and striatum (right map) for each promoter represented by the bar graph (blue ≤ 1.0, yellow = 1.5-fold, red ≥ 2-fold, n = 6). (E) Bar graph compares number of sequences enriched by total CREB or pCREB IP per region as in (C,D). Inside each bar are two heat maps that compare mean enrichment values from total CREB (left map) or pCREB ChIP (right map) versus preimmune IgG for each promoter represented by the bar (blue ≤ 1.0, yellow = 1.5-fold, red ≥ 2-fold, n = 6). ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; ECS, electroconvulsive seizure; FDR, false discovery rate; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; pCREB, phospho-Ser-133 CREB; SAM, statistical analysis of microarrays.

These results indicate that while CREB occupies a similar fraction of promoters in all three regions, its activity following ECS is lowest in striatum, as 50% fewer pCREB-occupied sequences were identified in striatum compared with the other regions. Similarly, only 25% of total CREB-occupied promoters in striatum were confidently enriched with the pCREB antibody compared with 43% and 45% in frontal cortex and hippocampus, respectively (Figure 3E). These results correlate with the immunohistochemisty experiments above. Almost all (>85%) promoter elements identified by pCREB ChIP were enriched (>1.2-fold) by total CREB ChIP in the corresponding region (Figure 3E).

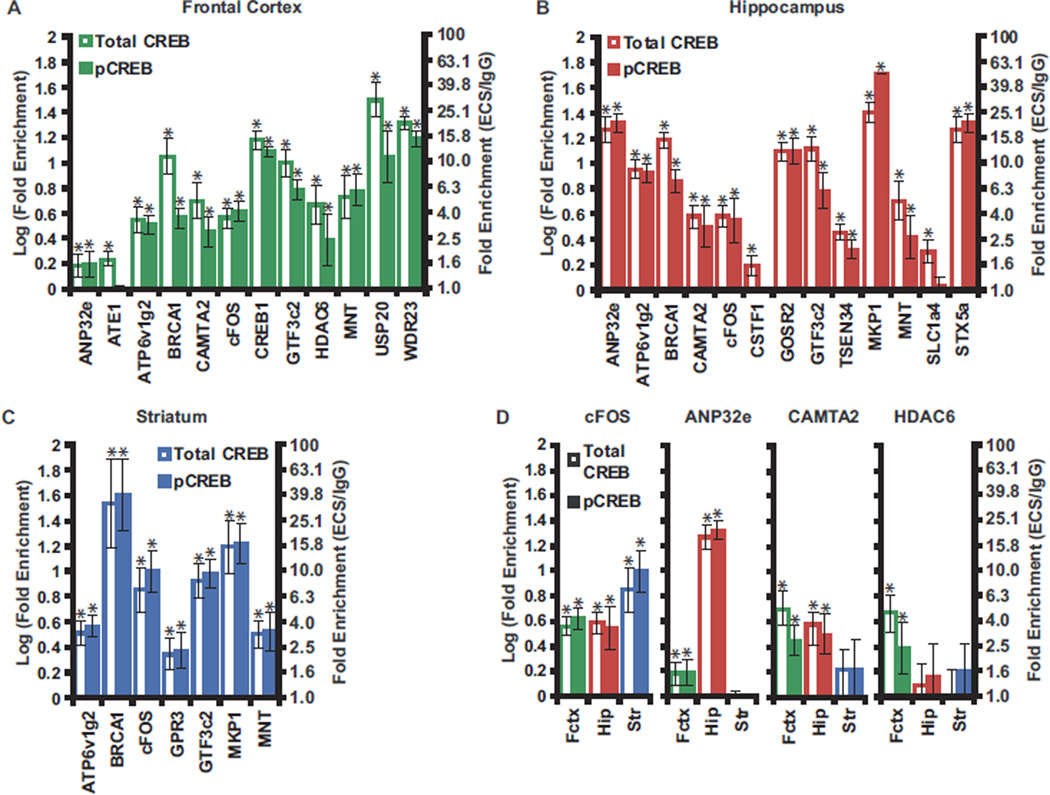

In total, we identified 864 different functional CREB/pCREB binding sites in rat brain proximal to 820 unique genes (7% of the promoters examined). Multiple lines of evidence confirm the accuracy of these CREB targets. Twenty-seven percent were identified in cell line studies using different CREB antibodies, and an additional 33% were predicted functional CREB binding sites based on half CRE site conservation in rat, mouse, and human (hypergeometric distribution p-value = 5.3e–18) (5–7). Similarly, 12% of the identified CREB target genes have TRANSFAC designated CREB binding sites within 2 kb of their TSS in both mouse and human (hypergeometric distribution p-value = 1.3e–6), demonstrating the conservation of these sites in the rodent and human genomes. We confirmed a subset (2.5%) of the CREB targets using real time PCR on unamplified DNA from an independent set of ChIPs with a success rate of >80% (Figure 4A–C). Of the 820 CREB target genes identified, 73% were not identified in previous cell line studies (5–7).

Figure 4.

Real time PCR confirmation of identified CREB targets. (A–C) An independent set of unamplified ChIP products from frontal cortex (A), hippocampus (B), and striatum (C) of ECS treated animals were analyzed by real time PCR to confirm enrichment of CREB targets identified by ChIP-chip. Gene names indicate gene most proximal to examined sequence (within 3 kb). Plotted values are log10 of the fold enrichment of each promoter. Fold enrichment equals the ratio of the promoter concentration in the total CREB (open bars) or pCREB (shaded bars) IP to the promoter concentration in the corresponding preimmuneIgG IP. Values are mean ± standard error, n = 6.* indicates Student t test p value of < .05 obtained by comparing PCR cycle numbers from IgGand antibody ChIP. Approximate fold enrichment values are given for reference. c-FOS, BRCA1, MKP1,and CREB1 are known CREB targets in many systems and were examined as positive controls. The other 19 promoters examined for enrichment by PCR (Supplement 3) were chosen randomly from the identified CREB targets. Fifteen of these 19 promoters were significantly enriched in the real time PCR experiments. (D) Comparison of enrichment of the indicated promoter in total CREB (open bars) or pCREB (shaded bars) ChIPs from frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum. Data were obtained, plotted, and colored as in (A–C). BRCA1, breast cancer gene 1; c-FOS, v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; CREB1, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein 1; ECS, electroconvulsive seizure; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; kb, kilobase; MKP1, MAP kinase phosphatase 1; pCREB, phospho-Ser-133 CREB; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Region Specificity of CREB Bound Promoters

Observations of epigenetic control over CREB occupancy in cell culture suggest that CREB targets likely vary between cell populations in vivo. We compared CREB occupancy in frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum. Eleven percent of the 864 CREB targets were identified in all three regions, and 35% were identified in at least two regions (Figure 3A, B). However, we also observed substantial differences in CREB occupancy between the three regions (Figure 3A–D). For example, 9% of CREB targets were clearly unique to a single region, not showing any trends toward enrichment (> 1.2-fold) by either total CREB or pCREB antibody in any other region. Frontal cortex and hippocampus shared the highest number of CREB targets, while hippocampus and striatum were most dissimilar. These differences begin to explain the diverse outputs of CREB activation in these brain regions (see below).

Real time PCR on unamplified ChIP product confirmed these results, identifying substantial regional overlap in the CREB targets but also striking regional differences in CREB occupancy at multiple promoters (Figure 4D). For example, the v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (c-FOS) promoter was strongly enriched by total CREB or pCREB ChIP from all three regions. In contrast, the acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32 family, member E (ANP32e) promoter was among the most strongly enriched sequences in hippocampus (18-fold by total CREB, 20-fold by pCREB antibody) but was enriched only 1.5-fold and 1.6-fold by total CREB and pCREB ChIP, respectively, from frontal cortex and was not significantly enriched from striatum.

The Genomic Distribution of CREB Targets

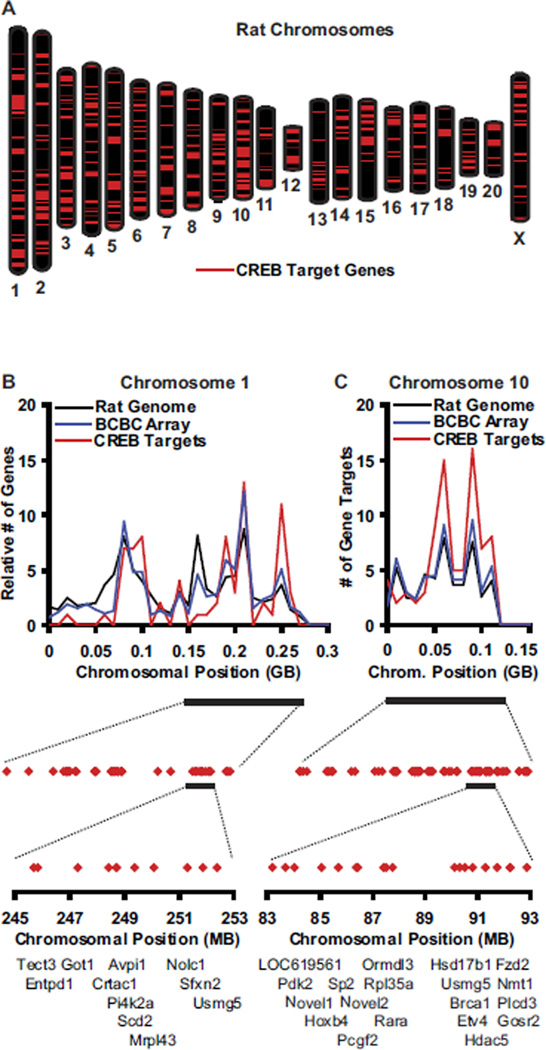

We mapped the genomic positions of the 820 CREB target genes. While CREB targets were identified on each rat chromosome, they were not distributed randomly when compared with the genomic density along each chromosome (Figure 5; Supplement 2). For example, chromosome 1 had 10% the expected number of CREB targets in the 30 Mb region between bases 1.5E8 and 1.8E8 and 280% the expected number in the 30 Mb between bases 2.4E8 and 2.7E8 (Figure 5B). Similarly, we identified 60% more CREB targets on chromosome 10 than expected (Figure 5C). These observations suggest that localized changes in chromatin architecture could regulate specific networks of CREB targets (see Discussion).

Figure 5.

Genomic map of the CREB regulon. (A) Positions of the identified CREB target genes (red lines) on rat chromosomes. Base pair numbering begins at top of chromosome. (B,C) Number of CREB targets identified (red) per 10 Mb of chromosomes 1 (B) and 10 (C) compared with the expected number of CREB targets given a random distribution of the 820 CREB targets and the number of genes per each 10 Mb region in the rat genome (black) or on the BCBC array (blue). A 120 Mb region of each chromosome is expanded to show the distribution of identified CREB targets (red diamonds). These regions are further expanded to show example CREB target clusters. MGI gene symbols are given, Novel1 = 5730593F17Rik, Novel2 = E130012A19Rik. See Supplement 2 for other chromosomes. BCBC, Beta Cell Biology Consortium; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; Mb, megabase; MGI, Mouse Genome Informatics.

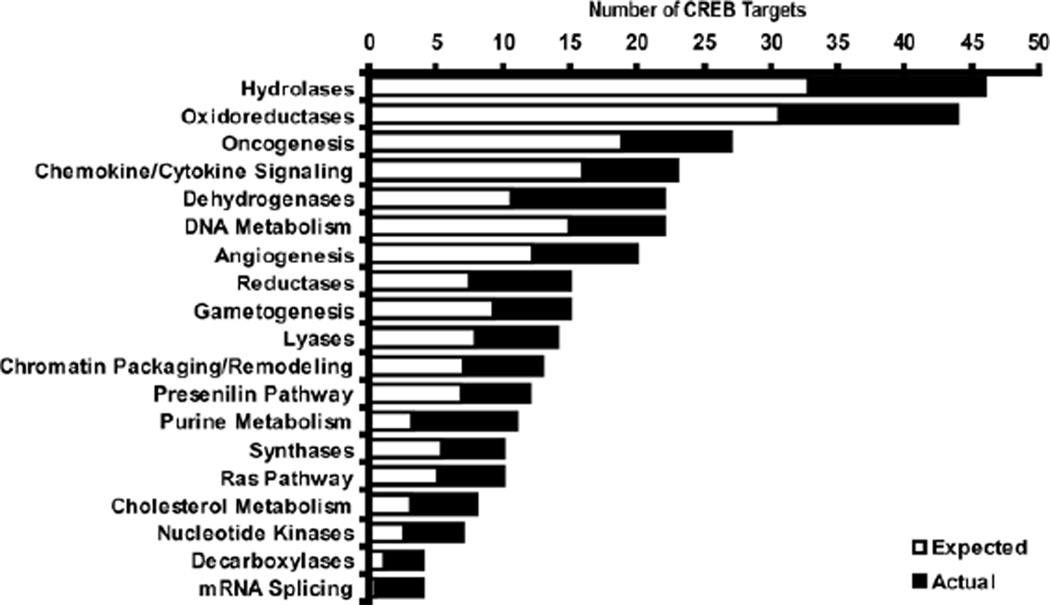

Biological Pathways and Gene Networks Regulated by CREB

We next characterized the molecular and biological functions of the 820 CREB/pCREB target genes. The CREB targets encompassed a diversified set of molecular functions, signaling pathways and biological processes. Bioprocesses and pathways highly represented in the CREB target list include metabolism, cell proliferation and plasticity, inflammatory/stress responses, chromatin remodeling, and the presenilin pathway (Figure 6). Metabolism genes are significantly overrepresented in the CREB target set, even when stringently correcting for multiple comparisons (corrected p-value 2.2e–7). We analyzed whether the biological functions of CREB vary by brain region by comparing the CREB targets identified in each region. The list of CREB targets unique to frontal cortex (enriched >1.5-fold, p< .05, SAM FDR <5%, but not enriched >1.2-fold, p < .05 from hippocampus or striatum) is enriched in genes involved in the presenilin pathway relative to the other two regions (Supplement 8). CREB targets unique to hippocampus are enriched in genes involved in messenger RNA (mRNA) transcription, protein biosynthesis and folding, and neurotransmitter release relative to the other regions. CREB targets unique to striatum are enriched for processes such as immunity, inflammation, apoptosis, proteolysis, serotonin degradation, and steroid metabolism relative to the other regions.

Figure 6.

Functional characterization of CREB target genes. The 820 CREB target genes were analyzed using the Panther Classification System. Panther categories enriched (binomial p< .05) in the CREB target list compared with all promoters present on the array are given.These categories are given as examples. They are not overrepresented in the list when accounting for multiple ontology comparisons, demonstrating the highly diversified biological functions of the CREB targets. Open bars indicate the number of genes from each category expected by chance based on the number of genes printed on the array from each category. Closed bars indicate the actual number of genes from each category with CREB binding sites identified in their promoters. CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein.

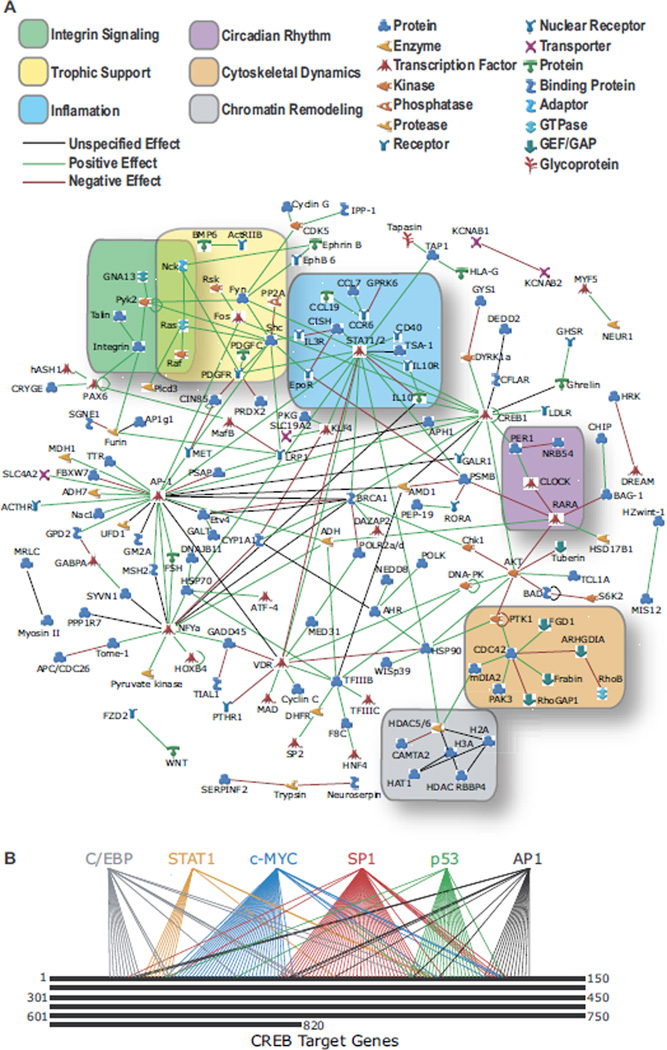

We also examined known relationships between the 820 CREB target genes using the GeneGo database. Twenty-six percent of the CREB targets were connected to CREB through published direct interactions with other CREB targets, 150% more than obtained with 820 randomly selected genes on the array (Figure 7A). The CREB interaction map also highlighted multiple gene networks central to CREB function, including inflammatory responses, circadian rhythm, cytoskeletal dynamics, integrin signaling, growth factor/neurotrophic factor signaling, chromatin remodeling, and gene transcription.

Figure 7.

The CREB interactome. (A) The 820 identified CREB targets were analyzed for direct interactions using GeneGo (Metacore, Kanata, Ontario, Canada). Network includes all CREB targets reported in the curated literature to interact directly withatleast one otherofthe identified CREB targets. Network connections specify positive (green), negative (red),or unspecified (black) interactions. Gene functional classes are categorized by symbols shown. Nodes are clustered into several biological functionsas highlighted. (B) Diagram depicts the number of identified CREB targets known to be transcriptionally regulated by C/EBP, STAT1, c-Myc, SP1, p53, and/or AP1. AP1, activator protein 1; C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; c-Myc, v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; SP1, specificity protein 1;STAT1, signal transducer and activatorof transcription 1;p53, p53 tumor suppressor.

Network analysis also indicated that CREB cooperates heavily with other transcription factors. We identified 67 transcription factors with functional CREB binding sites in their promoters, suggesting that CREB utilizes these transcription factors to indirectly regulate transcription (Supplements 6 and 7). CREB also cooperates with additional transcription factors at target promoters. Our analysis identified six transcription factors, CCAAT/ enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (cMyc), specificity protein 1 (SP1), p53 tumor suppressor (p53), and activator protein 1 (AP1), which are known to individually regulate the transcription of 10 or more of the identified CREB targets (Figure 7B). Together, these transcription factors co-regulate at least 118 of the CREB targets (this number is likely to increase as more targets of these transcription factors are identified).

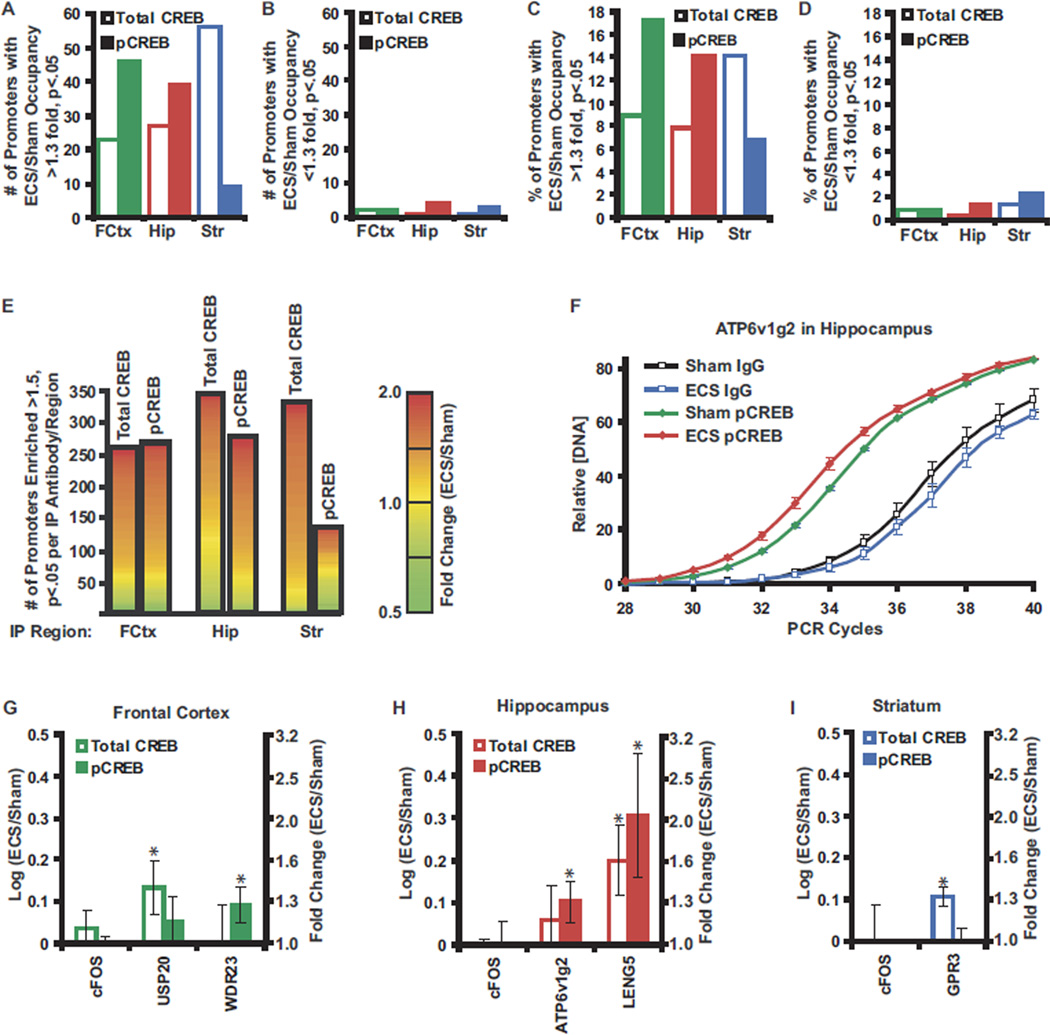

Regulation of CREB Occupancy and Phosphorylation by ECS

We next examined the effect of acute ECS on the CREB regulon in each brain region by co-hybridizing ChIP samples from sham (Cy3) or ECS (Cy5) treated rats. Fifteen minutes after ECS, CREB phosphorylation was increased at select promoters in frontal cortex and hippocampus relative to sham treated animals with robust (>1.3-fold), statistically significant (t test p < .05, SAM FDR <5%) increases detected at 46 (17%) and 39 (14%) of the pCREB occupied sequences identified above in frontal cortex and hippocampus, respectively (Figure 8A,C ,E; Supplement 9). In contrast, only 2 (1%) and 4 (1%) of the promoters in these regions, respectively, exhibited a significant reduction in enrichment by pCREB following ECS (Figure 8B,D,E). Electroconvulsive seizure had less effect on CREB phosphorylation at promoters in striatum with only 9 (7%) and 3 (2%) of pCREB occupied promoters having a significant increase or reduction, respectively, in enrichment following ECS (Figure 8A–E; Supplement 9).

Figure 8.

Acute enhancement of CREB occupancy and phosphorylation by ECS. (A,B) Bar chart showing the number of promoter sequences with > 1.3-fold, p< .05, SAM FDR < 5% enhancement (A) or reduction (B) in quantity immunoprecipitated 15 min following ECS relative to sham handled animals for either the total CREB (open bars) or pCREB (shaded bars) antibody in the indicated brain regions (n= 6). (C,D) Data in A (C) and B (D) plotted as the percent of the total number of promoters occupied by total CREB or pCREB in each region. (E) Bar graph showing number of sequences enriched > 1.5-fold, p< .05, SAM FDR < 5% by total CREB or pCREB ChIP relative to preimmune IgG ChIP from each region. Heat maps give the ratio of the promoter quantity immunoprecipitated between ECS and sham treated animals for each promoter represented by the bar (green: ECS/sham ≤ .5; yellow: ECS/sham = 1.0; red: ECS/sham ≥ 2; mean, n=6). (F) Real time PCR analysis of ATP6v1g2 promoter concentrations in unamplified ChIP product from pCREB or preimmune IgG IPs from hippocampus 15 min following ECS or sham treatment. Open squares indicate data obtained from preimmune IgG IPs from sham (black) and ECS (blue) treated animals. Closed triangles indicate data obtained from pCREB IPs from sham (green) and ECS (red) treated animals. Values are mean ± standard error, n = 6. (G–I) Real time PCR analysis comparing unamplified ChIP product from frontal cortex (G), hippocampus (H), and striatum (I) of sham and ECS treated animals. Values are log10 of the ratio of the promoter concentration in ChIPsfrom ECS treated animals to its concentration in ChIPsfrom sham treated animals. Open bars indicate total CREB ChIPs. Shaded bars indicate pCREB ChIPs. Values are mean ± standard error, n = 6. * indicates Student t test p value of < .05. Approximate fold changes are given for reference. ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein; ECS, electroconvulsive seizure; FDR, false discovery rate; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IP, immunoprecipitation; pCREB, phospho-Ser-133 CREB; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SAM, statistical analysis of microarrays.

We performed a similar analysis using total CREB ChIPs and consistently observed increased CREB occupancy at select promoters within 15 minutes of ECS (Figure 8A–E; Supplement 9). Electroconvulsive seizure significantly increased total CREB occupancy (>1.3-fold, t test p < .05, SAM FDR <5%) at 23 (9%), 27 (8%), and 56 (14%) of CREB binding sites identified in frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum, respectively. In contrast, only four genes had a significant decrease in total CREB occupancy in any brain region following ECS.

Real time PCR on unamplified ChIP product confirmed the increases in CREB occupancy and/or phosphorylation observed following ECS (Figure 8F–I). For example, in frontal cortex, significant increases in CREB occupancy at the ubiquitin specific peptidase 20 (USP20) promoter and significant increases in CREB phosphorylation at the WD repeat domain 23 (WDR23) promoter were confirmed by PCR (Figure 8G). Changes in CREB occupancy and phosphorylation occurred only at a subset of CREB targets. For example, no changes in CREB occupancy or phosphorylation were observed at the c-FOS CRE site in frontal cortex, hippocampus, or striatum following ECS (Figure 8G–I).

Discussion

These results present a global view of CREB function in brain and provide multiple insights into the neurobiology and regulation of CREB activity as well as the biological consequences of ECS.

Functional Characterization of the CREB Regulon in Brain

We observed CREB occupancy at 7% of the promoters examined. The identified CREB targets encompass a diversified set of biological functions and highlight the contributions of CREB to numerous neurobiological processes. For example, biological functions enriched in CREB targets include cell proliferation, development, metabolism, morphological plasticity, and stress responses, explaining the known involvement of CREB in each of these processes (Figures 6 and 7) (2,4). However, our data indicate that CREB also plays a central role in several previously unrealized pathways. For example, the CREB target list contains 13 genes involved in amyloid precursor protein (APP) processing (Figure 6). The transcription of one of these genes, presenilin enhancer 2 homolog (PSENEN), was recently shown to require the CRE in its promoter and to be induced following CREB activation (29). CREB is also reported to regulate presenilin 1 (PSEN1) (30). Combined, this indicates that CREB is a key regulator of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated APP processing pathway (29,30).

We observed CREB occupancy at the promoters of an extensive set of transcriptional regulators and modulators of chromatin structure, suggesting that in addition to controlling gene expression at individual promoters, CREB can indirectly regulate gene networks by modulating the expression of transcriptional machinery (Figures 6 and 7A). Further, many of the CREB targets are known to be regulated by other transcription factors, especially C/EBP, STAT1, Myc, SP1, p53, and AP1 (Figure 7B). Using in silico approaches, Zhang et al. (5) also observed an enrichment of conserved transcription factor binding sites, including SP1 and AP1 sites, in the promoters of known or predicted CREB targets. CREB likely cooperates with these transcription factors to provide precise and graded control over transcriptional levels. Indeed, numerous studies have shown cooperation between CREB and other transcription factors. For example, calcium and cyclic guanine monophosphate (cGMP) transcriptional synergism requires the cooperation of CREB and C/EBP-beta at the c-FOS promoter (31).

While CREB binding and Ser-133 phosphorylation are necessary for CREB-mediated gene transcription, these events are often not sufficient to initiate transcription due to the multiple additional regulatory nodes. For example, in HEK293 cells, only a small percentage of genes directly respond to forskolin-induced CREB phosphorylation at their promoters (5). This suggests that CREB-mediated transcription requires integration of multiple regulatory inputs. Despite this complication, numerous CREB targets identified in our study (such as breast cancer gene 1 [BRCA1], c-FOS, galanin receptor 1 [GALR1], interleukin 10 [IL-10], period homolog 1 [PER1], and PSENEN) have been shown to be regulated by CREB (29,32–36).

Our analysis uncovered several novel elements of control over CREB activity. We identified multiple regions of the rat genome that are enriched or depleted in CREB binding sites (Figure 5; Supplement 2). A large number of publications have shown that co-transcribed genes, including highly transcribed genes, tissue-specific genes, and functionally related genes, often cluster within the genome (37– 47). The clustering of CREB targets at specific chromosomal locations may provide an energetically favorable mechanism to simultaneously regulate the expression of specific sets of CREB targets in response to localized changes in chromatin architecture. It may also contribute to the cellular and temporal specificity of the CREB regulon by regulating networks of CREB targets that are expressed during cell differentiation, developmental time points, and under specific environmental conditions.

We observed substantial differences in CREB occupancy and phosphorylation between frontal cortex, hippocampus, and striatum that could explain the diversified consequences of CREB activation in these regions (Figure 3; Supplement 8). For example, CREB targets unique to hippocampus are enriched in genes involved in transcriptional activation, protein biosynthesis, and synaptic transmission relative to the other regions, while CREB targets unique to striatum are enriched in genes involved in immunity, inflammation, apoptosis, proteolysis, serotonin degradation, and steroid metabolism. These differences likely contribute to the divergent behavioral consequences of enhanced CREB activity in these regions, namely the antidepressant or prodepressive effects of CREB hyperactivity in hippocampus or striatum, respectively (48–50).

Acute Induction of CREB Binding and Phosphorylation by ECS

The reduced CREB activity observed in the brains of depressed patients, the antidepressive effects of CREB activation in rodent hippocampus, and the activation of CREB by diverse antidepressants suggest that CREB plays a critical role in both the etiology and treatment of depressive disorders (3). We sought to determine the basis for CREB’s contributions to antidepressant responses by monitoring its functional activity following ECS. Acute ECS rapidly enhanced CREB occupancy and phosphorylation at promoters within hippocampus and frontal cortex, elevating CREB activity within multiple bioprocesses known to be induced by ECS, including trophic support, angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and plasticity (Figure 2A; Supplement 9) (23,51). Increases in these bioprocesses in cortical and limbic brain regions have been implicated in the antidepressant actions of ECS and chemical antidepressants, suggesting that CREB plays an integral role in the molecular and behavioral adaptations to ECS (23,52–54). While ECS enhanced CREB binding at select promoters in striatum, it had little effect on CREB phosphorylation in this region. The inability of ECS to promote phosphorylation of CREB in striatum may be critical for its overall positive physiological and behavioral effects, as the striatal CREB regulon contains a high concentration of proinflammatory and apoptotic genes and hyperactivation of CREB in striatum produces depressive effects (55).

While CREB phosphorylation on Ser-133 has been intensely studied for its ability to activate CREB in response to acute extracellular stimuli, it has remained controversial whether changes in CREB occupancy contribute to the regulation of CREB by acute stimuli. Several groups have observed changes in CREB occupancy at individual promoters following in vivo stimuli, including pharmacological upregulation of cAMP signaling and extended fasting (12–14). Here, we report that ECS rapidly triggers widespread induction of both CREB binding and phosphorylation in brain indicating that both events are important for the regulation of CREB by acute in vivo stimuli (Figure 8).

Importantly, changes in CREB occupancy and phosphorylation occurred only at select targets (Figure 8G–I). While this could result in part from CREB activation in limited cell populations, our data in combination with previous studies suggest that several mechanisms may provide acute and localized control over CREB activity at each promoter. A ChIP-chip study in yeast demonstrated that most mitogen-activated protein kinases and protein kinase A subunits physically associate with the genes they regulate (56). This mechanism may contribute to our observation that ECS stimulates CREB phosphorylation at a subset of promoters and previous findings that phosphorylation of CREB by different stimuli or kinases can trigger distinct patterns of gene expression (15,56). Although Ser-133 phosphorylation increases CREB’s affinity for certain variant CRE sites in vitro, it remains controversial whether this regulates CREB binding in vivo given the high concentration of CREB in the nucleus (400 nmol/L, KD for CREB binding <180 nmol/L) (1). Our data demonstrate that changes in CREB occupancy can occur independent of phosphorylation (Figure 8; Supplement 9). CREB occupancy may be modified by rapid changes in local chromatin structure, such as changes in histone acetylation that occur at CREB-regulated promoters in hippocampus within minutes of ECS and in striatum immediately following pharmacological stimulation (57,58). Similarly, alterations to accessory proteins at CRE sites may occlude or potentiate CREB binding or the kinetics and stability of CREB phosphorylation at each promoter. While our experiments indicate that CREB phosphorylation can occur after CREB binding, the reverse order is also likely to occur.

A Multifaceted Model of CREB Regulation

We propose that the specific contributions of CREB to diverse neurobiological processes and the varied yet specific transcriptional outputs observed following CREB activation are a function of multifaceted control over CREB activity (Figure 9). Our dynamic map of the CREB regulon in brain has defined multiple layers of control over CREB, including regional control over CREB occupancy within tissues, clustering of CREB regulatory networks within the genome, CREB control over and cooperation with various members of the chromatin remodeling and transcriptional machinery, and acute localized regulation of CRE occupancy and activating phosphorylation of CREB. Together, these regulatory mechanisms provide a basis for integration and differentiation of multiple spatial and temporal cues to drive diverse yet specific patterns of CREB-mediated transcription and provide insight into how CREB orchestrates such a diverse set of biological responses within the CNS and other tissues.

Figure 9.

Model of dynamic control over the CREB regulon. Three potential CRE states are proposed under basal conditions: 1) unoccupied by CREB, 2) occupied by CREB, and 3) stably inactivated, for example by methylation (CH3). These states contributeto the regional and developmental specificity of the CREB regulon and have different requirements for transcriptional activation. CRE sites occupied under basal conditions require only CREB phosphorylation to trigger transcription. Basally unoccupied CRE sites require two independent events to activate transcription: 1) initiation ofCREB binding, and2)CREB phosphorylation, allowing the integration of cues from two different cellular events. While our experiments find that CREB phosphorylation can occur after binding, the reverse order is also likely to occur. Kinases may physically associate with and activate CREB at specific promoters. CREB cooperates with other transcription factors to provide an additional levelof transcriptional control. CRE,cyclic adenosinemonophosphate (cAMP) response element; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by MH14276 (KQT), MH25642 (RSD), MH45481 (RSD), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) U24 NS05186 (SSN), and NARSAD (SSN).

We thank Rose Terwilliger for assistance with immunohistochemistry experiments.

Footnotes

Dr. Tanis reported no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work. Dr. Duman reported no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work. Dr. Newton reported no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work.

Supplementary material cited in this article is available online.

References

- 1.Shaywitz A, Greenberg ME. CREB: A stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlezon WA, Jr., Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Odom DT, Koo SH, Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Best J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501076102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Impey S, McCorkle SR, Cha-Molstad H, Dwyer JM, Yochum GS, Boss JM, et al. Defining the CREB regulon: A genome-wide analysis of transcription factor regulatory regions. Cell. 2004;119:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Euskirchen G, Royce TE, Bertone P, Martone R, Rinn JL, Nelson FK, et al. CREB binds to multiple loci on human chromosome 22. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3804–3814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.9.3804-3814.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cha-Molstad H, Keller DM, Yochum GS, Impey S, Goodman RH. Cell-type-specific binding of the transcription factor CREB to the cAMP-response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13572–13577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405587101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iguchi-Ariga SM, Schaffner W. CpG methylation of the cAMP-responsive enhancer/promoter sequence TGACGTCA abolishes specific factor binding as well as transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1989;3:612–619. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinowich K, Hattori D, Wu H, Fouse S, He F, Hu Y, et al. DNA methylation-related chromatin remodeling in activity-dependent BDNF gene regulation. Science. 2003;302:890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.1090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancini DN, Singh SM, Archer TK, Rodenhiser DI. Site-specific DNA methylation in the neurofibromatosis (NF1) promoter interferes with binding of CREB and SP1 transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:4108–4119. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfl S, Martinez C, Majzoub JA. Inducible binding of cyclic adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate (cAMP)-responsive element binding protein (CREB) to a cAMP-responsive promoter in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:659–669. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiroi H, Christenson LK, Strauss JF., 3rd Regulation of transcription of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: Temporal and spatial changes in transcription factor binding and histone modification. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;215:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Rubins NE, Ahima RS, Greenbaum LE, Kaestner KH. Foxa2 integrates the transcriptional response of the hepatocyte to fasting. Cell Metab. 2005;2:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayr B, Canettieri G, Montminy MR. Distinct effects of cAMP and mitogenic signals on CREB-binding protein recruitment impart specificity to target gene activation via CREB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10936–10941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191152098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madsen TM, Treschow A, Bengzon J, Bolwig TG, Lindvall O, Tingström A. Increased neurogenesis in a model of electroconvulsive therapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen AC, Eisch AJ, Sakai N, Takahashi M, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Regulation of GFRalpha-1 and GFRalpha-2 mRNAs in rat brain by electroconvulsive seizure. Synapse. 2001;39:42–50. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<42::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braveman MW, Chen-Plotkin AS, Yohrling GJ, Cha JH. Chromatin immunoprecipitation technique for study of transcriptional dysregulation in intact mouse brain. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;277:261–276. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-804-8:261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsankova N, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Histoone modifications at gene promoter regions in rat hippocampus after acute and chronic electroconvulsive seizures. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5603–5610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phuc Le P, Friedman JR, Schug J, Brestelli JE, Parker JB, Bochkis IM, Kaestner KH. Glucocorticoid receptor-dependent gene regulatory networks. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xuan Z, Zhao F, Wang J, Chen G, Zhang MQ. Genome-wide promoter extraction and analysis in human, mouse, and rat. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R72. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-r72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeon SH, Seong YS, Juhnn YS, Kang UG, Ha KS, Kim YS, Park JB. Electroconvulsive shock increases the phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein at Ser-133 in rat hippocampus but not in cerebellum. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newton S, Collier E, Hunsberger J, Adams D, Salvanayagam E, Duman RS. Gene profile of electroconvulsive seizures: Induction of neurogenic and angiogenic factors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10841–10851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10841.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thome J, Sakai N, Shin KH, Steffen C, Zhang Y-J, Impey S, et al. cAMP response element-mediated gene transcription is upregulated by chronic antidepressant treatment. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4030–4036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04030.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikder D, Kodadek T. Genomic studies of transcription factor-DNA interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanlon SE, Lieb JD. Progress and challenges in profiling the dynamics of chromatin and transcription factor binding with DNA microarrays. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi L, Reid LH, Jones WD, Shippy R, Warrington JA, Baker SC, et al. The MicroArray Quality Control (MAQC) project shows inter- and intraplatform reproducibility of gene expression measurements. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1151–1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang R, Zhang YW, Sun P, Liu R, Zhang X, Zhang X, et al. Transcriptional regulation of PEN-2, a key component of the gamma-secretase complex, by CREB. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1347–1354. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1347-1354.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitsuda N, Ohkubo N, Tamatani M, Lee YD, Taniguchi M, Namikawa K, et al. Activated cAMP-response element-binding protein regulates neuronal expression of presenilin-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9688–9698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Zhuang S, Cassenaer S, Casteel DE, Gudi T, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Synergism between calcium and cyclic GMP in cyclic AMP response element-dependent transcriptional regulation requires cooperation between CREB and C/EBP-beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4066–4082. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4066-4082.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zachariou V, Georgescu D, Kansal L, Merriam P, Picciotto MR. Galanin receptor 1 gene expression is regulated by cyclic AMP through a CREB-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2001;76:191–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gee K, Angel JB, Ma W, Mishra S, Gajanayaka N, Parato K, Kumar A. Intracellular HIV-Tat expression induces IL-10 synthesis by the CREB-1 transcription factor through Ser133 phosphorylation and its regulation by the ERK1/2 MAPK in human monocytic cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31647–31658. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Platzer C, Fritsch E, Elsner T, Lehmann MH, Volk HD, Prosch S. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive elements are involved in the transcriptional activation of the human IL-10 gene in monocytic cells. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3098–3104. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199910)29:10<3098::AID-IMMU3098>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atlas E, Stramwasser M, Mueller CR. A CREB site in the BRCA1 proximal promoter acts as a constitutive transcriptional element. Oncogene. 2001;20:7110–7114. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sassone-Corsi P, Visvader J, Ferland L, Mellon PL, Verma IM. Induction of proto-oncogene fos transcription through the adenylate cyclase pathway: Characterization of a cAMP-responsive element. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1529–1538. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gotter J, Brors B, Hergenhahn M, Kyewski B. Medullary epithelial cells of the human thymus express a highly diverse selection of tissue-specific genes colocalized in chromosomal clusters. J Exp Med. 2004;199:155–166. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boon WM, Beissbarth T, Hyde L, Smyth G, Gunnersen J, Denton DA, et al. A comparative analysis of transcribed genes in the mouse hypothalamus and neocortex reveals chromosomal clustering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14972–14977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406296101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashita T, Honda M, Takatori H, Nishino R, Hoshino N, Kaneko S. Genome-wide transcriptome mapping analysis identifies organ-specific gene expression patterns along human chromosomes. Genomics. 2004;84:867–875. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boutanaev AM, Kalmykova AI, Shevelyov YY, Nurminsky DI. Large clusters of co-expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. Nature. 2002;420:666–669. doi: 10.1038/nature01216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JM, Sonnhammer EL. Genomic gene clustering analysis of pathways in eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2003;13:875–882. doi: 10.1101/gr.737703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snel B, Bork P, Huynen MA. The identification of functional modules from the genomic association of genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5890–5895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092632599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen BA, Mitra RD, Hughes JD, Church GM. A computational analysis of whole-genome expression data reveals chromosomal domains of gene expression. Nat Genet. 2000;26:183–186. doi: 10.1038/79896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kovanen PE, Young L, Al-Shami A, Rovella V, Pise-Masison CA, Radonovich MF, et al. Global analysis of IL-2 target genes: Identification of chromosomal clusters of expressed genes. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1009–1021. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spellman PT, Rubin GM. Evidence for large domains of similarly expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. J Biol. 2002;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caron H, van Schaik B, van der Mee M, Bass F, Riggins G, van Sluis P, et al. The human transcriptome map: Clustering of highly expressed genes in chromosomal domains. Science. 2001;291:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1056794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lercher MJ, Urrutia AO, Hurst LD. Clustering of housekeeping genes provides a unified model of gene order in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;31:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen AC, Shirayama Y, Shin KH, Neve RL, Duman RS. Expression of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) in hippocampus produces an antidepressant effect. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton S, Thome J, Wallace TL, Shirayama Y, Schlesinger L, Sakai N, et al. Inhibition of cAMP response element-binding protein or dynorphin in the nucleus accumbens produces an antidepressant-like effect. J Neurosci. 2002;24:10883–10890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10883.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pliakas A, Carlson RR, Neve RL, Konradi C, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA. Altered responsiveness to cocaine and increased immobility in the forced swim test associated with elevated CREB expression in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7397–7403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07397.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Altar C, Laeng P, Jurata LW, Brockman JA, Lemire A, Bullard J, et al. Electroconvulsive seizures regulate gene expression of distinct neurotrophic signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2667–2677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5377-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newton SS, Girgenti MJ, Collier EF, Duman RS. Electroconvulsive seizure increases adult hippocampal angiogenesis in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:819–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duman R. Depression: A case of neuronal life and death? Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newton SS, Thome J, Wallace TL, Shirayama Y, Schlesinger L, Sakai N, et al. Inhibition of cAMP response element-binding protein or dynorphin in the nucleus accumbens produces an antidepressant-like effect. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10883–10890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10883.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pokholok DK, Zeitlinger J, Hannett NM, Reynolds DB, Young RA. Activated signal transduction kinases frequently occupy target genes. Science. 2006;313:533–536. doi: 10.1126/science.1127677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsankova NM, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Histone modifications at gene promoter regions in rat hippocampus after acute and chronic electroconvulsive seizures. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5603–5610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DE, Truong HT, et al. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]