Abstract

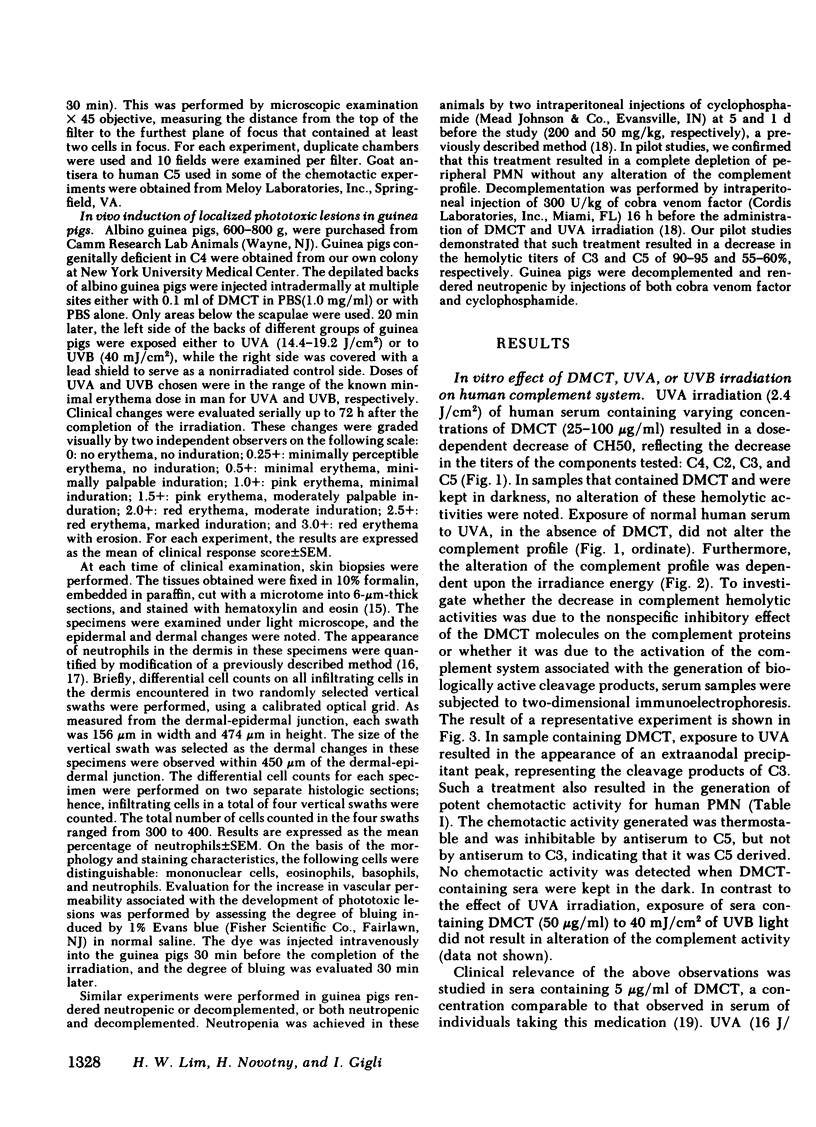

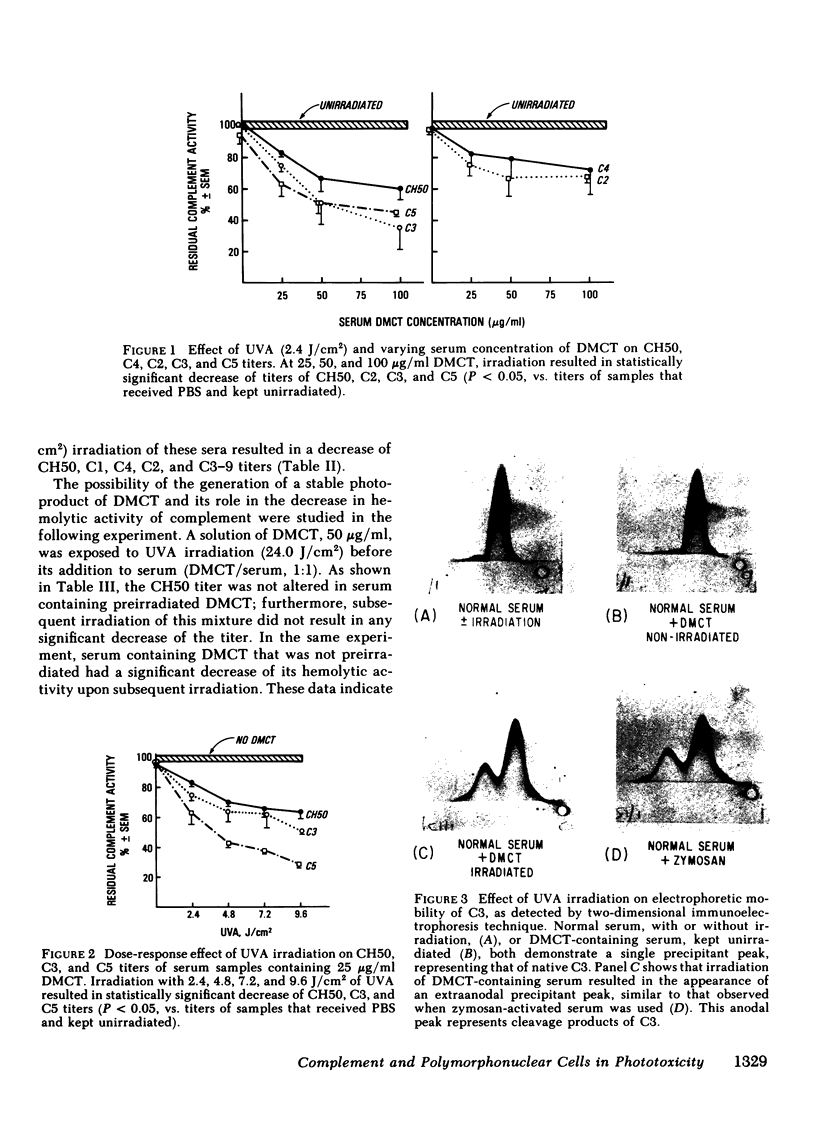

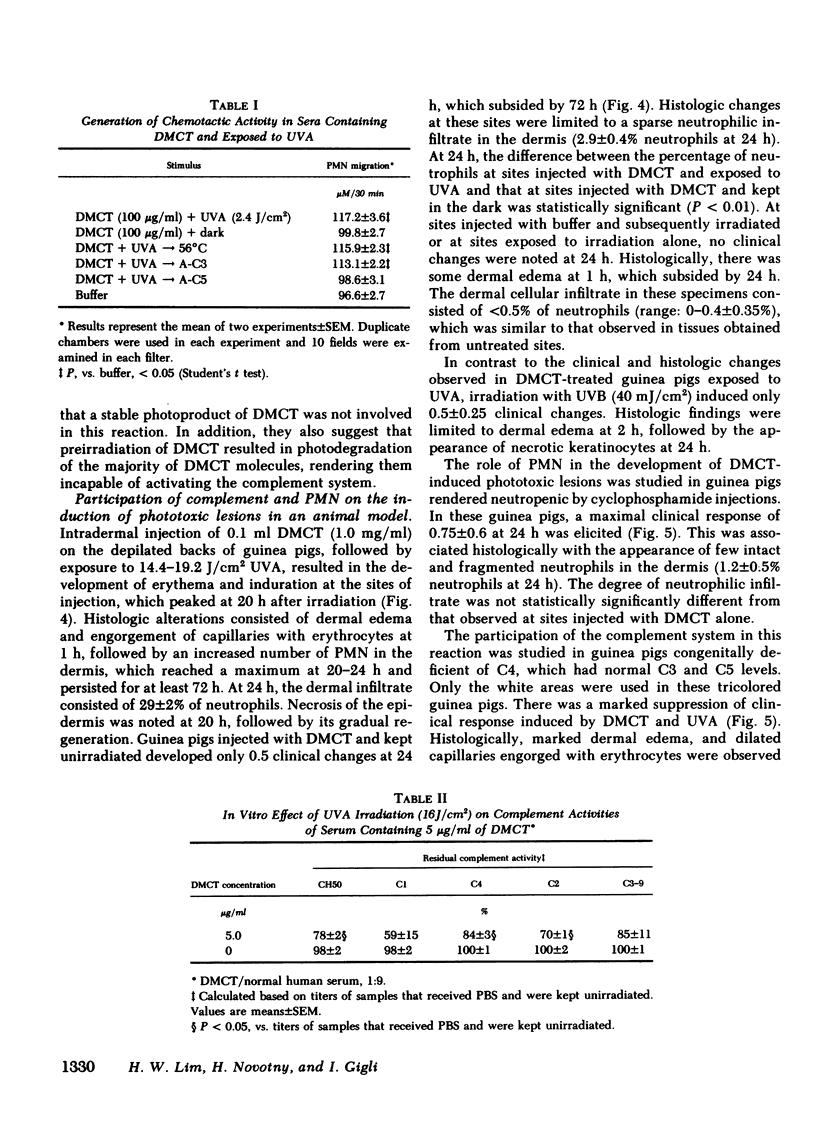

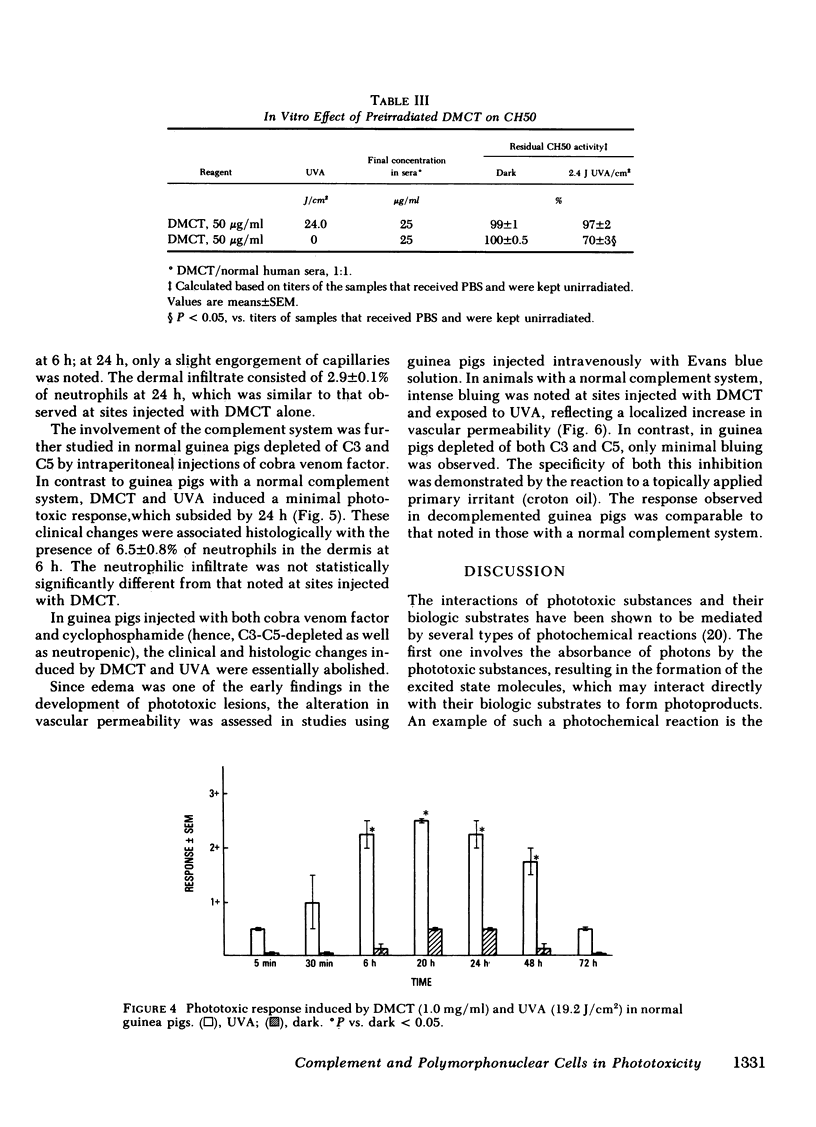

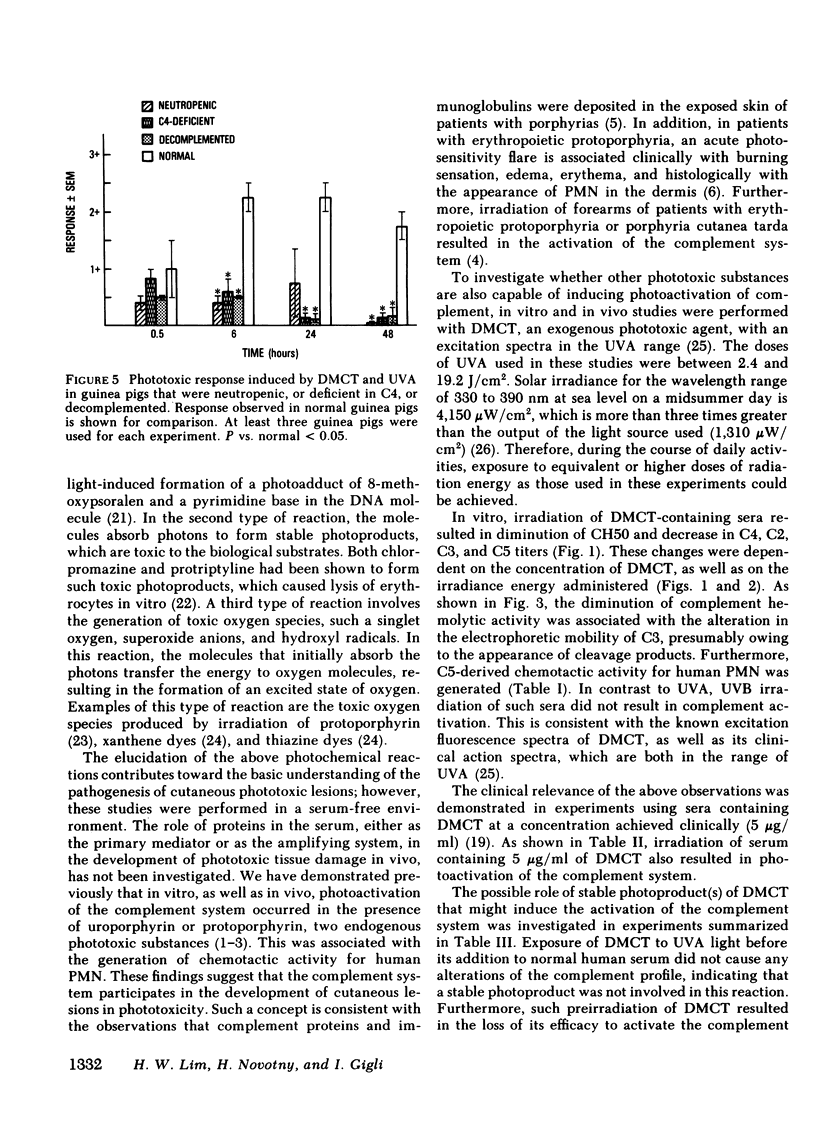

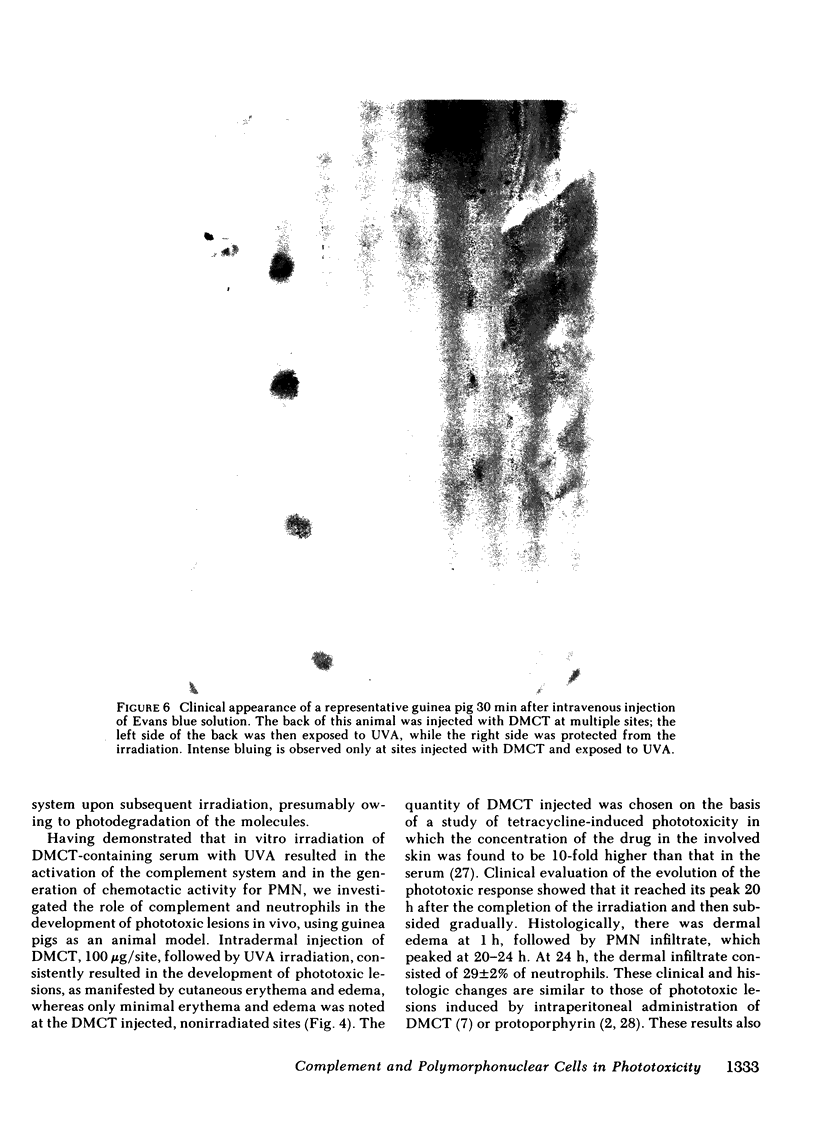

In this study, demethylchlortetracycline was used as a prototype of exogenous phototoxic substances. In vitro, exposure of serum containing demethylchlortetracycline to ultraviolet-A irradiation resulted in the diminution of total complement hemolytic activity and C4, C2, C3, and C5 activities. In addition, chemotactic activity for human polymorphonuclear cells was generated, which was thermostable and antigenically related to human C5 but not human C3. In vivo, phototoxic lesions were induced in guinea pigs upon intradermal injections of demethylchlortetracycline solution, followed by ultraviolet-A irradiation. On a scale of 0-3+, the animals developed a maximal response of 2.5 at 20 h. This clinical response was associated with cellular infiltrate in the dermis, consisting of 29 +/- 2% of neutrophils at 24 h. The participation of the polymorphonuclear cells was evaluated in guinea pigs rendered neutropenic by treatment with cyclophosphamide. In these guinea pigs, demethylchlortetracycline and ultraviolet-A induced a maximal response of 0.75 +/- 0.5, which was associated histologically with 1.2 +/- 0.5% neutrophils in the dermis. The role of complement in this process was studied in guinea pigs congenitally deficient in C4, and in guinea pigs decomplemented by treatment with cobra venom factor. In contrast to normal guinea pigs, C4-deficient animals exhibited a maximal reaction of 0.83 +/- 0.16 at 6 h, which subsided within 24 h. Cobra venom factor-treated guinea pigs developed a maximal response of 0.5 at 0.5 and at 6 h. These clinical changes were associated with the development of an increased vascular permeability, as demonstrated by studies using guinea pigs injected intravenously with Evans blue solution. In animals with a normal complement system, there was intense localized bluing at the sites of phototoxic lesion. In contrast, only minimal bluing was observed in decomplemented guinea pigs. These data indicate that a normal number of polymorphonuclear cells and an intact complement system are required for the full development of demethylchlortetracycline-induced phototoxic lesions.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baer R. L., Miles W. J., Rorsman H., Harber L. C. Erythropoietic protoporphyria: photosensitivity patterns in man and laboratory animals. Dermatologica. 1967;135(1):5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen S. I., Catalano P. M., Helfman R. J. Tetracycline sun sensitivity. Arch Dermatol. 1966 Jan;93(1):77–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak H. F., Dvorak A. M., Simpson B. A., Richerson H. B., Leskowitz S., Karnovsky M. J. Cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity. II. A light and electron microscopic description. J Exp Med. 1970 Sep 1;132(3):558–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.3.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak H. F., Mihm M. C., Jr Basophilic leukocytes in allergic contact dermatitis. J Exp Med. 1972 Feb 1;135(2):235–254. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.2.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein J. H., Tuffanelli D. L., Epstein W. L. Cutaneous changes in the porphyrias. A microscopic study. Arch Dermatol. 1973 May;107(5):689–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A., Nussenzweig V., Gigli I. Structural and functional differences between the H-2 controlled Ss and Slp proteins. J Exp Med. 1978 Nov 1;148(5):1186–1197. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.5.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost P., Weinstein G. D., Gomez E. C. Methacycline and demeclocycline in relation to sunlight. JAMA. 1971 Apr 12;216(2):326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gigli I. Prosser White Oration 1978. The complement system in inflammation and host defence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979 Sep;4(3):271–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1979.tb02640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrest B. A., Soter N. A., Stoff J. S., Mihm M. C., Jr The human sunburn reaction: histologic and biochemical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981 Oct;5(4):411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosea S., Brown E., Hammer C., Frank M. Role of complement activation in a model of adult respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1980 Aug;66(2):375–382. doi: 10.1172/JCI109866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochevar I. E., Lamola A. A. Chlorpromazine and protriptyline phototoxicity: photosensitized, oxygen independent red cell hemolysis. Photochem Photobiol. 1979 Apr;29(4):791–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1979.tb07768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochevar K. E. Phototoxicity mechanisms: chlorpromazine photosensitized damage to DNA and cell membranes. J Invest Dermatol. 1981 Jul;77(1):59–64. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12479244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad K., Hönigsmann H., Gschnait F., Wolff K. Mouse model for protoporphyria. II. Cellular and subcellular events in the photosensitivity flare of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1975 Sep;65(3):300–310. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12598366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAURELL C. B. ANTIGEN-ANTIBODY CROSSED ELECTROPHORESIS. Anal Biochem. 1965 Feb;10:358–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(65)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamola A. A., Doleiden F. H. Cross-linking of membrane proteins and protoporphyrin-sensitized photohemolysis. Photochem Photobiol. 1980 Jun;31(6):597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1980.tb03752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. W., Gigli I. Role of complement in porphyrin-induced photosensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 1981 Jan;76(1):4–9. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12524423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. W., Perez H. D., Goldstein I. M., Gigli I. Complement-derived chemotactic activity is generated in human serum containing uroporphyrin after irradiation with 405 nm light. J Clin Invest. 1981 Apr;67(4):1072–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI110119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim H. W., Perez H. D., Poh-Fitzpatrick M., Goldstein I. M., Gigli I. Generation of chemotactic activity in serum from patients with erythropoietic protoporphyria and porphyria cutanea tarda. N Engl J Med. 1981 Jan 22;304(4):212–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101223040406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison W. L., Paul B. S., Parrish J. A. The effects of indomethacin on long-wave ultraviolet-induced delayed erythema. J Invest Dermatol. 1977 Mar;68(3):130–133. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12492445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. A., Jr, Jensen J., Gigli I., Tamura N. Methods for the separation, purification and measurement of nine components of hemolytic complement in guinea-pig serum. Immunochemistry. 1966 Mar;3(2):111–135. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(66)90292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez H. D., Lipton M., Goldstein I. M. A specific inhibitor of complement (C5)-derived chemotactic activity in serum from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1978 Jul;62(1):29–38. doi: 10.1172/JCI109110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy S., Austen K. F. A stoichiometric assay for the fourth component of complement in whole human serum using EAC'la-gp and functionally pure human second component. J Immunol. 1967 Dec;99(6):1162–1172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sams W. M., Jr, Epstein J. H. The experimental production of drug phototoxicity in guinea pigs. I. Using sunlight. J Invest Dermatol. 1967 Jan;48(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/jid.1967.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnait F. G., Wolff K., Konrad K. Erythropoietic protoprophyria--submicroscopic events during the acute photosensitivity flare. Br J Dermatol. 1975 May;92(5):545–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder D. S. Cutaneous effects of topical indomethacin, an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis, on UV-damaged skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1975 May;64(5):322–325. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12512265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel J. D., Gallin J. I. Polymorphonuclear leukocyte and monocyte chemoattractants produced by human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 1979 Apr;63(4):609–618. doi: 10.1172/JCI109343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song P. S., Tapley K. J., Jr Photochemistry and photobiology of psoralens. Photochem Photobiol. 1979 Jun;29(6):1177–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1979.tb07838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratigos J. D., Magnus I. A. Photosensitivity by dimethylchlortetracycline and sulphanilamide. Br J Dermatol. 1968 Jun;80(6):391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1968.tb12326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond S. H., Hirsch J. G. Leukocyte locomotion and chemotaxis. New methods for evaluation, and demonstration of a cell-derived chemotactic factor. J Exp Med. 1973 Feb 1;137(2):387–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.137.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]