ABSTRACT

The FtsEX protein complex has recently been proposed to play a major role in coordinating peptidoglycan (PG) remodeling by hydrolases with the division of bacterial cells. According to this model, cytoplasmic FtsE ATPase interacts with the FtsZ divisome and FtsX integral membrane protein and powers allosteric activation of an extracellular hydrolase interacting with FtsX. In the major human respiratory pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), a large extracellular-loop domain of FtsX (ECL1FtsX) is thought to interact with the coiled-coil domain of the PcsB protein, which likely functions as a PG amidase or endopeptidase required for normal cell division. This paper provides evidence for two key tenets of this model. First, we show that FtsE protein is essential, that depletion of FtsE phenocopies cell defects caused by depletion of FtsX or PcsB, and that changes of conserved amino acids in the FtsE ATPase active site are not tolerated. Second, we show that temperature-sensitive (Ts) pcsB mutations resulting in amino acid changes in the PcsB coiled-coil domain (CCPcsB) are suppressed by ftsX mutations resulting in amino acid changes in the distal part of ECL1FtsX or in a second, small extracellular-loop domain (ECL2FtsX). Some FtsX suppressors are allele specific for changes in CCPcsB, and no FtsX suppressors were found for amino acid changes in the catalytic PcsB CHAP domain (CHAPPcsB). These results strongly support roles for both ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX in signal transduction to the coiled-coil domain of PcsB. Finally, we found that pcsBCC(Ts) mutants (Ts mutants carrying mutations in the region of pcsB corresponding to the coiled-coil domain) unexpectedly exhibit delayed stationary-phase autolysis at a permissive growth temperature.

IMPORTANCE

Little is known about how FtsX interacts with cognate PG hydrolases in any bacterium, besides that ECL1FtsX domains somehow interact with coiled-coil domains. This work used powerful genetic approaches to implicate a specific region of pneumococcal ECL1FtsX and the small ECL2FtsX in the interaction with CCPcsB. These findings identify amino acids important for in vivo signal transduction between FtsX and PcsB for the first time. This paper also supports the central hypothesis that signal transduction between pneumococcal FtsX and PcsB is linked to ATP hydrolysis by essential FtsE, which couples PG hydrolysis to cell division. The classical genetic approaches used here can be applied to dissect interactions of other integral membrane proteins involved in PG biosynthesis. Finally, delayed autolysis of the pcsBCC(Ts) mutants suggests that the FtsEX-PcsB PG hydrolase may generate a signal in the PG necessary for activation of the major LytA autolysin as pneumococcal cells enter stationary phase.

Introduction

Peptidoglycan (PG) biosynthesis requires the regulated activities of the synthetic penicillin-binding proteins, numerous modification enzymes, and PG hydrolases (reviewed in references 1 to 3). PG hydrolases are required to cleave various bonds in mature PG and thereby allow access points for insertion of newly synthesized glycan strands (4–6). They also allow the ultimate separation of daughter cells (7, 8). The roles of PG hydrolases in PG remodeling during cell division are only starting to be understood, partly because most bacterial species contain functionally redundant division PG hydrolases, and PG hydrolases play roles in processes other than division, including PG recycling, programmed lysis during sporulation, bacterial predation, resuscitation following dormancy, and fratricide during competence (7, 9–11).

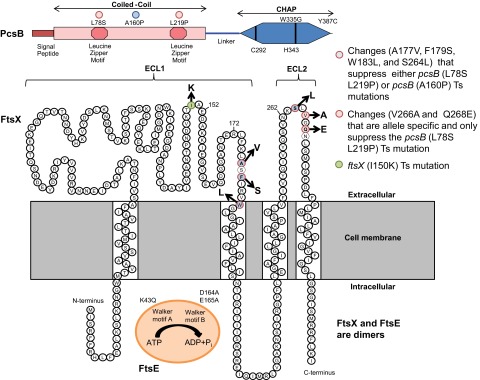

The activities of division PG hydrolases have to be carefully regulated to coordinate PG cleavage with stage of cell division and to prevent PG damage that could be catastrophic (2, 5, 7). An emerging model is that division PG hydrolases are intrinsically inactive due to limited access to their active sites or to autoinhibitory α-helices that block active sites (5, 12, 13). Inhibition is relieved by allosteric interactions with regulatory proteins that couple PG hydrolysis to stages of cell division (5, 12, 13). The conserved FtsEX complex recently emerged as a major regulator of PG hydrolysis during bacterial cell division (2, 7, 14, 15). FtsEX is essential or conditionally essential in a variety of bacterial species (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), with the exception of low-GC Gram-positive bacilli, which may contain redundant mechanisms for FtsEX function (5, 16, 17). FtsEX structurally resembles an ABC transporter (18), although several pieces of evidence suggest that FtsEX acts as a signal transduction system, rather than as a transporter of an unknown substrate (19, 20). FtsX is an integral membrane protein with cytoplasmic amino and carboxyl termini, 4 transmembrane segments, and 1 large and 1 small extracellular loop (ECL1 and ECL2, respectively) (Fig. 1) (19). The transmembrane helices of FtsX lack charged residues that are found in canonical ABC transporters, and no putative extracellular substrate-binding protein is transcribed near ftsEX (19). Moreover, FtsX interacts with FtsA and FtsQ, FtsE interacts with FtsZ, and the FtsE ATPase promotes septal ring constriction in Escherichia coli (1, 19, 21, 22). Together, these results favor a role for FtsEX in promoting complex formation during cell division, rather than acting as a transporter.

FIG 1 .

Summary of PcsB, FtsX, and FtsE domains and amino acid changes described in this paper. (Top) PcsB. Locations of changes in PcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) (red dots) and PcsBA160P(Ts) (blue dot) in CCPcsB and PcsBW335G(Ts) and PcsBY387C(Ts) in CHAPPcsB are indicated. Other structural features include the signal peptide, which is processed from the mature protein, the leucine zipper motifs in CCPcsB, and the required active-site amino acids Cys292 and His343 in CHAPPcsB (24). (Middle) FtsX. The predicted topology of FtsX is based on reference 19. Amino acid changes that suppress pcsB(Ts) mutations are color coded as indicated. The FtsXI150K change is also indicated. (Bottom) FtsE. The K43Q mutation and the D164A and E165A mutations in the Walker A and B motifs, respectively, are indicated. See the text for additional details.

Involvement of FtsEX as a regulator of PG hydrolysis was reported concurrently in E. coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae (14, 15). In E. coli, FtsEX is conditionally essential and required for growth in media with low osmotic strength (15, 20). ECL1 of FtsXEco interacts with a coiled-coil domain of the EnvC activator protein, which in turn activates PG amidases AmiA and AmiB, whose activity is autoinhibited (13, 15). In contrast, pneumococcal FtsEX is essential, and the ECL1 of FtsXSpn interacts with the coiled-coil domain in the amino terminus of the PcsB protein (CCPcsB) (14) (Fig. 1). PcsB is essential for growth of serotype 2 strains of S. pneumoniae (23, 24), and the absence of PcsB severely impairs growth in other serotypes of S. pneumoniae (25; our unpublished results). Besides its coiled-coil domain, PcsB contains a carboxyl-terminal CHAP domain (CHAPPcsB), found in PG amidases and endopeptidases (5). Although purified PcsB lacks PG hydrolytic activity, probably due to some type of autoinhibition, changes to the catalytic cysteine (Cys) 292 and histidine (His) 343 are not tolerated (24), and amino acid changes in CHAPPcsB cause temperature sensitivity (Ts) (Fig. 1) (14), strongly implying that PcsB acts as a PG hydrolase. PcsB localizes to division equators and septa, and depletion of FtsX releases PcsB into the growth medium (14).

In this paper, we report the isolation of several new classes of mutations to assess the functions and interactions of the FtsEX-PcsB complex in S. pneumoniae. These experiments confirm the expectation that FtsE ATPase is required for pneumococcal cell division and viability. Suppressor analysis implicates both ECL1 and ECL2 of FtsX in interactions with CCPcsB and provides strong support for signal transduction between the FtsEX complex and PcsB. Finally, phenotypes of pcsBCC(Ts), ftsXECL2(Sup), and ftsXECL1(Ts) mutants revealed a wider role of the FtsEX-PcsB complex in pneumococcal autolysis.

RESULTS

FtsE is essential in S. pneumoniae D39, and depletion of FtsE phenocopies PcsB or FtsX depletion.

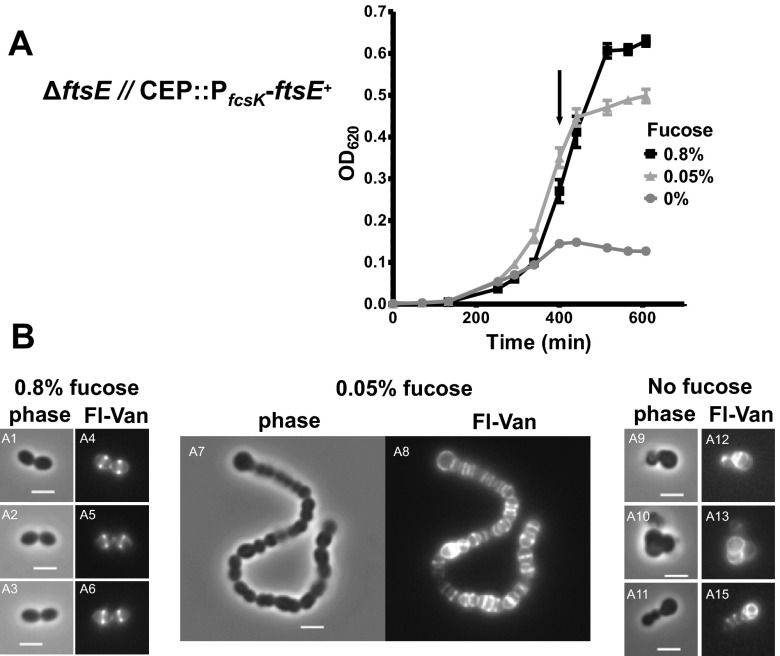

Previously, we demonstrated that pcsB and ftsX are both essential in S. pneumoniae serotype 2 strain D39 (14, 23, 24). Depletion of FtsX led to defects in cell division similar to those seen with depletion of PcsB, suggesting that PcsB and FtsX are involved in the same biological process (14). Since FtsE and FtsX directly interact in E. coli and S. pneumoniae (1, 19, 26), we expected that depletion of FtsE would phenocopy depletion of PcsB or FtsX. To minimize leaky expression of FtsE, we fused ftsE+ to the PfcsK fucose-inducible promoter and fcsK ribosome-binding site, followed by the walJ transcription terminator in the ectopic CEP site in the pneumococcal chromosome (strain IU5382) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) (27). We then deleted ftsE from its native locus and screened for colonies that require fucose for growth. The resulting strain IU5756 (ΔftsE::P-erm [deletion of codons 21 to 195 of 231]//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) grew similarly to parent strain IU5382 (ftsE+//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) in BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose (where // designates a separate chromosomal location) (Fig. 2A; data not shown). Reducing the amount of fucose to 0.05% (wt/vol) reduced the growth yield but not the growth rate of cultures. FtsE-depleted cells formed chains of compacted, semispherical cells that showed misplaced peripheral and septal labeling by fluorescent vancomycin, which labels regions of active PG synthesis (Fig. 2B) (23, 24). Upon removal of fucose, IU5756 cultures stopped growing after ~400 min and did not lyse within the additional ~200 min monitored. Cells severely depleted for FtsE became more spherical and showed aberrant placement of PG synthesis (Fig. 2B, images A8, A13, and A15). These phenotypes match those reported previously for depletion of PcsB or FtsX (14, 23, 24), consistent with FtsE, FtsX, and PcsB acting together in cell division.

FIG 2 .

Depletion of FtsE phenocopies depletion of PcsB and FtsX. Cells of strain IU5756 (ΔftsE::P-erm//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE) were grown in BHI broth containing 0.4% fucose at 37°C, collected by centrifugation, washed once with BHI broth lacking fucose, and resuspended in BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol), 0.05% (wt/vol), and 0% fucose, and growth was monitored (see Materials and Methods). (A) Representative growth curves following the shift to the concentrations of l-fucose indicated. (B) After 400 min (arrow in panel A), cells were collected, stained with fluorescent vancomycin (Fl-Van), and visualized by microscopy (see Materials and Methods). Bar, 2 μm. Replicate independent experiments were done more than 3 times with similar results.

Amino acid changes in the conserved Walker motifs of FtsE are not tolerated by S. pneumoniae D39.

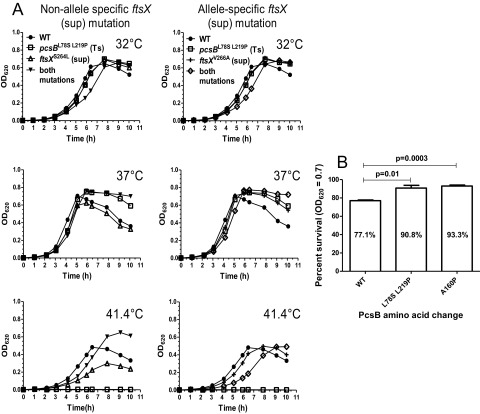

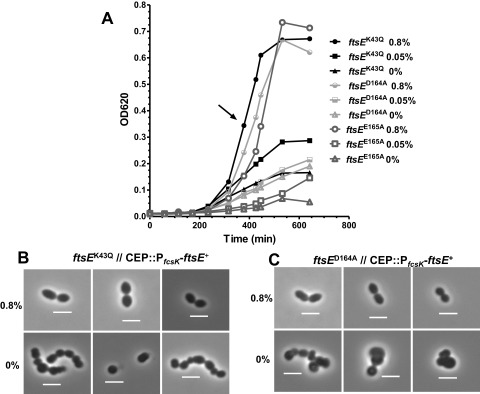

Conserved amino acids in the ATP binding pocket of the Walker A and Walker B motifs of FtsE were shown to be critical for FtsE function in E. coli (15, 19). Changes in these amino acids impaired FtsZ ring constriction during E. coli cell division, resulting in the formation of elongated cells, like those observed in ΔftsE mutants (15, 19). We tested whether comparable amino acid changes in the ATP binding pocket of pneumococcal FtsE resulted in a lethal phenotype (Fig. 1). Mutant alleles ftsE (K43A), ftsE (D164A), and ftsE (E165A) were exchanged into the ftsE chromosomal locus in a merodiploid strain that expresses ftsE+ from the ectopic CEP site (strain IU5818 [ΔftsE::P-kan rpsL+//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+]) (see Materials and Methods; also, see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The resulting strains (IU6023, IU6025, and IU6027) required 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose for growth and formation of wild-type-looking cells (Fig. 3; also, see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 3 .

Amino acid changes FtsEK43Q, FtsED164A, and FtsEE165A in the Walker A and B motifs of FtsE are not tolerated. Strain IU6023 (IU1824 ftsEK43Q//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+), IU6025 (IU1824 ftsED164A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+), and IU6027 (IU1824 ftsEE165A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) were grown in BHI broth supplemented with 0.4% (wt/vol) fucose overnight. Cells were collected by centrifugation, washed with BHI broth lacking fucose, and resuspend to an OD620 of ~0.001 in BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol), 0.05% (wt/vol), or 0% fucose (see Materials and Methods). (A) Representative growth curves following the shift to the concentrations of l-fucose indicated. (B and C) After ~400 min (arrow in panel A), cells were observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Bar, 2 µm. Cells of strain IU6025 (C) and IU6027 (not shown) looked alike. The experiment was done twice with similar results.

Removal of fucose and depletion of FtsE+ led to growth cessation and formation of spherical cells with aberrant division planes, similar to those observed when ectopically expressed FtsE+ was depleted in a ΔftsE mutant (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the ftsE (K43A, D164A, and E165A)//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+ mutants showed significantly reduced growth in low (0.05% [wt/vol]) fucose (Fig. 3A), whereas in repeated independent experiments, the ΔftsE//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+ mutant grew normally until cultures possibly ran out of fucose (Fig. 2A). Although we do not know the level of FtsE expressed from the ectopic CEP site in 0.05% (wt/vol) fucose, the impaired growth of the ftsE (K43A, D164A, and E165A)//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+ mutants is consistent with a dominant negative effect of the mutant FtsE in dimers with wild-type FtsE. From these combined results, we conclude that FtsE ATPase is required for pneumococcal cell division.

Isolation of ftsX mutations that suppress pcsBCC(Ts) mutations.

Previously, we reported that Ts mutations can be isolated in pcsBCC and pcsBCHAP, indicating the requirement of these two domains for PcsB function in pneumococcal cells (14). Four pcsB(Ts) mutations were used in this study. pcsBL78S-L219P changes two leucines in the tandem zipper motifs of CCPcsB, and both changes are required to impart temperature sensitivity (Fig. 1) (14). pcsBA160P changes an alanine, which modeling indicates may be in a hairpin region formed by interactions between the leucine zipper motifs. pcsBW335G and pcsBY387C change amino acids near the active-site His343 and at the very end of CHAPPcsB, respectively (Fig. 1). Previously, Western blotting showed that the cellular amount of PcsBL78S-L219P did not decrease at the nonpermissive (41.4°C) compared to the permissive (32°C) temperature (14). A substantial fraction (>50%) of wild-type PcsB+ is normally released from pneumococcal cells into broth cultures (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) (23), but a greater proportion of PcsBL78S-L219P was not released at 41.4°C than at 32°C (14). Likewise, Western blots of PcsBA160P, PcsBW335G, and PcsBY387C using anti-PcsB antibody showed that these mutant proteins were not destabilized or released more at 41.4°C than at 32°C (see Fig. S2), despite more overall instability of PcsBY387C, and to a lesser extent PcsBW335G, than PcsBA160P or PcsB+ at either temperature. Together, these results suggest that the PcsB(Ts) mutant proteins have lost critical signaling or catalytic functions at the nonpermissive temperature.

To gain information about the signaling between PcsB and FtsX, we used error-prone PCR to target random mutations to an amplicon containing ftsX linked to a downstream kanamycin resistance marker (IU4325) (see Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material), transformed the mutated ftsX amplicon into each pcsB(Ts) mutant, and selected for growth at the nonpermissive temperature of 41.4°C (see Materials and Methods). Screening of ~38,000 transformants of the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutants revealed 7 different ftsX suppressor mutations (Table 1; also, see Table S4 in the supplemental material) that were confirmed by DNA sequencing of the chromosome region corresponding to the entire PCR amplicon used in transformations. Backcrossing the ftsX suppressor mutations into the pcsB(Ts) mutant in which they were originally selected confirmed that the suppression was due solely to the ftsX mutations and not to mutations outside ftsX. In contrast to the pcsBCC(Ts) mutations, no suppressor of the pcsBW335G(Ts) mutation in CHAPPcsB was obtained upon screening of ~16,800 colonies (Fig. 1 and Table 1; also, see Table S4 in the supplemental material), although we cannot rule out the possibility that we missed a rare suppressor mutation. The pcsBY387C(Ts) mutation is leaky and allows slow growth at 41.4°C, and limited screening of ~3,800 colonies did not turn up any ftsX suppressors of the pcsBY387C mutation (Table 1; also, see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1 .

Temperature-sensitive mutants and suppressors isolated in this study

| Temperature-sensitive allele(s) (strain[s]) | Corresponding suppressor allele (strain)a | Comment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| pcsBL78S-L219P (IU4261) | ftsXV266A (IU6363) | Allele specific |

| ftsXQ268E (IU5690) | Allele specific | |

| ftsXK88M-R204H (IU6367) | Allele specific | |

| pcsBL78S-L219P (IU4261) and pcsBA160P (IU4256 and IU4262) | ftsXA177V (IU5692; IU6525) | Not allele specific |

| ftsXF179S (IU6365; IU5961) | Not allele specific | |

| ftsXW183L (IU6335; IU6333) | Not allele specific | |

| ftsXS264L (IU6361; IU6270) | Not allele specific | |

| pcsBW335G (IU4081) | None isolated yet | See Table S4 |

| pcsBY387C (IU4257) | None isolated | Leaky at 41.4°C; see Table S4 |

| ftsXI150K (IU6001) | In progress | See the text |

| ftsXY254C-I300T (IU5694) | In progress | See the text |

ftsXF179S and ftsXS264L were originally isolated as suppressors of the pcsBA160P mutation. Other ftsX suppressor mutations were isolated during screens of a pcsBL78S-L219P mutant. Strains are indicated from backcrosses (Table S2). ftsXA177V was also isolated in strains IU6351, IU6385, and IU6387 with the mutations ftsXI192V-D276Q (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Region specificity and allele specificity of ftsXECL1 and ftsXECL2 suppressors of pcsBCC(Ts) mutations.

Of the seven ftsX suppressors of pcsBCC(Ts) mutations isolated in this study, six resulted in single-amino-acid changes in ECL1FtsX or ECL2FtsX (Fig. 1). Of these six ftsX suppressors, three (ftsXA177V, ftsXF179S, and ftsXW183L) are in the far-distal region of ECL1FtsX and three (ftsXS264L, ftsXV266A, and ftsXQ268E) are in the small domain ECL2FtsX, which has not been characterized before (Fig. 1; Table 1). All six ftsX single suppressors did not suppress the pcsBW335G(Ts) mutation in CHAPPcsB, indicating that the ftsX suppressor mutations do not cause a general gain of function of FtsX.

We next tested the ftsX suppressors for allele specificity (28). The three ftsX mutations in ECL1FtsX (ftsXA177V, ftsXF179S, and ftsXW183L) and one in ECL2 (ftsXS264L) suppressed both the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutations, whereas two ftsX mutations in ECL2FtsX (ftsXV266A and ftsXQ268E) were allele specific and suppressed only the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) mutations. Finally, one other ftsX suppressor isolated in this study contained two mutations (ftsXK88M-R204H), which change amino acids in the proximal region of ECL1 and in the cytoplasmic domain between ECL1 and ECL2 (Table 1). The ftsXK88M-R204H suppressor was also allele specific for the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) mutations, but the ftsXK88M-R204H mutations were not separated or characterized further in this study. We conclude that region-specific and allele-specific suppressors clustered in the distal ECL1FtsX and in ECL2FtsX can correct conformational defects in the CCPcsB but not in CHAPPcsB.

pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), and ftsXV266A(Sup) mutations delay autolysis in stationary phase.

We characterized the growth of the Ts and suppressor strains described above at the permissive temperatures of 32°C and 37°C (Fig. 4A; also, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The single mutants containing pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), ftsXS264L(Sup), or ftsXV266A(Sup) (where Sup indicates that the mutation acts as a suppressor) and the suppressed double mutants containing pcsBL78S-L219P ftsXS264L or pcsBL78S-L219P ftsXV266A grew like the parent strain at 32°C (Fig. 4A; also, see Fig. S3). In contrast, the pcsBW335G(Ts) mutant grew more slowly and to a lower yield than the other strains, even at 32°C (see Fig. S3). At 37°C, cultures of the parent strain and the single mutants containing ftsXS264L(Sup) or pcsBW335G(Ts) showed the characteristic drop in optical density at 620 nm (OD620) in stationary phase, indicative of autolysis (Fig. 4A; also, see Fig. S3). Unexpectedly, cultures of the single mutants containing pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), or ftsXV266A(Sup) and the suppressed double mutants containing pcsBL78S-L219P ftsXS264L or pcsBL78S-L219P ftsXV266A did not show this pronounced drop in OD620 in stationary phase (Fig. 4A; also, see Fig. S3). Consistent with a reduced drop in OD620, live-dead staining (Materials and Methods) showed that the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutants retained cell viability in early stationary phase (OD620 ≈ 0.7) at 37°C compared to a drop for the parent strain (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4 .

Delayed autolysis at 37°C of single mutants pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and ftsXV266A(Sup) and double pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXS264L(Sup) and pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXV266A(Sup) mutants. (A) Strains IU1945 (parent), IU4261 [pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts)], IU6426 [ftsXS264L(Sup)], IU6371 [pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXS264L(Sup)], IU6439 [ftsXV266A(Sup)], and IU6363 [pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXV266A(Sup)] were grown in BHI broth at 32°C and diluted to an OD620 of ~0.001 in fresh BHI broth prewarmed to the temperatures indicated. Growth was monitored as described in Materials and Methods, and representative growth curves from more than 3 independent experiments are shown. ftsXS264L(Sup) and ftsXV266A(Sup) are non-allele-specific and allele-specific suppressors of pcsBCC(Ts), respectively (Fig. 1; see the text). A comparable delay in autolysis was detected for strain IU4262 [pcsBA160P(Ts)] (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). (B) At an OD620 of 0.7 in 37°C cultures, cells of strain IU1945 (parent), IU4261 [pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts)], and IU4262 [pcsBA160P(Ts)] were stained for viability as described in Materials and Methods. Experiments were performed independently three times (n = 3), and ~1,300 cells were counted per sample (B).

At 41.4°C, all of the pcsB Ts mutants failed to grow as expected (Fig. 4A; also, see Fig. S3). In contrast, the suppressed pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXV266A(Sup) double mutant grew similarly to the parent strain, whereas the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) ftsXS264L(Sup) double mutant consistently gave higher growth yields than the parent at 41.4°C (Fig. 4A). Autolysis is caused by activation of a small amount of extracellular LytA amidase as pneumococcal cells enter stationary phase (29). In addition, LytA PG hydrolysis contributes to the autolysis that occurs when pneumococcus encounters penicillin G and in the fratricide response during competence (9, 29, 30). Consequently, we compared the culture densities of mutants containing pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) or pcsBA160P(Ts) with an isogenic ΔlytA mutant as cells entered stationary phase or were treated with penicillin G (see Fig. S3D). For ~5 h in stationary phase, the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), and ΔlytA mutants maintained their culture densities compared to the parent strain and a pcsBW335G(Ts) mutant (see Fig. S3). If left overnight, the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutant cultures lysed, whereas the ΔlytA mutant culture maintained its density. At the concentration of penicillin G added, ΔlytA cultures stopped growing and did not lyse, whereas the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutant cultures showed rapid autolysis like the parent strain (see Fig. S3D). We conclude that stationary-phase autolysis is delayed, but not eliminated, by the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) and pcsBA160P(Ts) mutations, and these mutations do not provide any protection against the rapid autolysis induced by penicillin G treatment.

DISCUSSION

PG remodeling by hydrolases is essential for PG biosynthesis and must be carefully coordinated with specific stages of bacterial cell division (5, 6, 14, 15). In this process, endopeptidases and amidases are thought to remove cross-links between PG peptides and to cleave off PG peptides, respectively, and thereby allow insertion and cross-linking of newly synthesized glycan strands or the separation of divided cells (4–6, 31). In S. pneumoniae, the PcsB protein has the hallmarks of a PG hydrolase (32). Typical of many hydrolases from Gram-positive organisms, PcsB is processed and exported to the cell surface by the SecA system (23), and PcsB consists of a surface-binding domain (CCPcsB) and a catalytic domain (CHAPPcsB) (Fig. 1) (see the introduction). PcsB is a relatively abundant protein (~5,000 monomers) on the pneumococcal cell surface, yet this amount represents less than 50% of the PcsB lost to the culture medium of exponential growing S. pneumoniae (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) (14, 23). Like other regulated, remodeling PG hydrolases, purified PcsB lacking its signal peptide is catalytically inactive in a variety of assay formats, including zymograms (data not shown) (14, 23, 25). In zymograms, apparent clearing by PcsB protein was not due to PG hydrolysis, because it still occurred in control experiments containing catalytically inactive PcsB Cys292Ala and His343Ala mutant proteins (data not shown). In contrast, the Cys292Ala and His343Ala amino acid changes are not tolerated in cells, consistent with an essential PG hydrolase function for PcsB (24).

The lack of PG hydrolysis activity by purified PcsB led to the hypothesis of allosteric activation of PcsB by an essential membrane protein, which was found to be FtsX in complex with FtsE (see the introduction) (Fig. 1) (2, 14, 24). In this paper, we show that FtsE, like PcsB and FtsX, is essential in serotype 2 S. pneumoniae (Fig. 2A), and depletion of each of these proteins leads to similar defects in cell division (Fig. 2B), consistent with a shared function. Interestingly, partial depletion of PcsB, FtsX, or FtsE causes unencapsulated pneumococcus to form chains of cells that are more spherical and compressed than those of the diplococcal parent strain (Fig. 2B) (14, 23, 24). This phenotype may indicate that decreased PG remodeling by the PcsB-FtsEX hydrolase blocks glycan chain insertion in midcell peripheral (sidewall-like) PG synthesis, which would cause formation of spherical cells (2). In addition, this paper shows that the conserved amino acids in the ATP binding site of FtsE are essential for pneumococcal growth, supporting the idea that FtsE ATPase activity is required for PcsB-FtsEX signaling and coordination with cell division. Based on the EnvC-FtsEX complex in E. coli (15), we expect that loss of FtsE ATPase activity will not alter the localization of the PcsB-FtsEX complex in S. pneumoniae. This and other hypotheses about the role of FtsE ATPase function await testing in future experiments.

This study also provides strong new support for the idea that the FtsX interaction with PcsB is mediated by interactions between ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX and CCPcsB. The FtsEX complex resembles an ABC transporter (see the introduction) (18, 19), and biochemical reconstitution of FtsEX-PcsB function could be challenging (33, 34). To gain more insight into the interactions between PcsB and FtsX, we used an updated version of classical suppressor analysis (28) that combines error-prone PCR targeting of mutations with the ease of strain construction by pneumococcal transformation (see Results and Materials and Methods). We found region- and allele-specific mutations in ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX that indicate interactions between the distal portion of ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX in FtsX and CCPcsB, but not CHAPPcsB, in PcsB (Fig. 1 and Table 1; see Results). Alignments of ECL1 and ECL2 from different bacteria showed that the amino acid changes caused by the ftsX suppressor mutations are in nonconserved amino acids (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This observation is consistent with the fact that ECL1 and ECL2 interact with different PG hydrolases in different bacterial species, such as PcsB in S. pneumoniae and EnvC-AmiA/B in E. coli (14, 15). Since FtsE and FtsX are likely both dimers (19, 26), our results suggest a complex interaction surface between FtsX and PcsB and indicate that biochemical interaction studies will need to include both ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX, perhaps in rigid juxtaposition. The amino acid changes identified in this study also will be invaluable in future biochemical studies.

We are currently reversing the genetic scheme described above, starting with the isolation of ftsX(Ts) mutants enriched by error-prone PCR. Of 10 ftsX(Ts) mutants isolated from several independent screens, 9 contained the single ftsXI150K mutation, which changes a conserved isoleucine in the last third of ECL1FtsX (Fig. 1 and Table 1; also, see Fig. S4 and Table S2 in the supplemental material). The remaining mutant contained two mutations: ftsXY254C in ECL2FtsX and ftsXI300T in the cytoplasmic domain of FtsX near its carboxyl terminus (Table 1). We are in the process of selecting for pcsB or ftsE suppressors of the ftsXI150K(Ts) mutation. But together, these studies of FtsX show that these genetic approaches can be used to interrogate the functions and complex interactions of other integral membrane proteins involved in pneumococcal cell division.

Finally, we found that the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), and ftsXV266A(Sup) mutations delay autolysis in stationary phase at 37°C (Fig. 4; also, see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In S. pneumoniae, stationary-phase autolysis is catalyzed by the LytA amidase, which is a surface choline-binding protein (9, 29). However, LytA lacks a signal export sequence, and only about 5% of cellular LytA finds its way to the surface of exponentially growing cells, where it remains inactive (29). As pneumococcal cells enter stationary phase in culture, surface LytA is thought to sense some structural signal in the PG that activates the surface LytA in some cells, thereby triggering release of cytoplasmic LytA and autolysis of the culture (29). Our results suggest that the PG signal for LytA release may be reduced by certain mutations of pcsB and ftsX, including pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), and ftsXV266A(Sup), thereby delaying the onset of autolysis. Previously, we showed that the PG lactoyl-peptide composition was not altered upon PcsB underexpression or depletion (23). However, recent studies have shown that depletion of some cell division PG hydrolases results in subtle changes in PG composition that require determination of PG peptides attached to glycan-chain disaccharides to be detected (4). Ongoing experiments will determine whether the PG structure of pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts), pcsBA160P(Ts), and ftsXV266A(Sup) mutants is different from that of the isogenic pcsB+ ftsX+ parent strain as cells enter stationary phase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and strain constructions.

Strains used in this study (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) were constructed in an unencapsulated derivative of serotype 2 strain D39 (35), which was chosen to highlight cell morphology defects (23). Unless otherwise specified, bacteria were grown on TSAII blood agar (BA) plates or statically in Becton Dickinson brain heart infusion (BHI) broth at the temperatures indicated in the figures in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 as described before (14, 36, 37). Overnight cultures with an OD620 of <0.2 were diluted in fresh BHI broth to an OD620 of ~0.002, and bacterial growth was monitored by determining the OD620 hourly as described in references 14, 36, and 37.

Strains containing site-directed point mutations, deletion mutations, or antibiotic markers were constructed by transforming linear DNA amplicons synthesized by overlapping fusion PCR into competent pneumococcal cells as described in references 23, 36, and 37. Primers synthesized and the DNA templates used for PCRs are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. Allele exchange of point mutations was done using the Janus cassette method as described previously (36, 38). All constructs in strains were confirmed by PCR mapping and DNA sequencing of relevant chromosomal regions as described in references 14, 36, and 37.

Depletion of FtsE+ in ∆ftsE, ftsEK43Q, ftsED164A, and ftsEE165A merodiploid strains.

Procedures to deplete FtsE in pneumococcal strains IU5756 (IU1824 ΔftsE::P-erm//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+), IU6023 (IU1824 ftsEK43Q//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+), IU6025 (IU1824 ftsED164A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+), and IU6027 (IU1824 ftsEE165A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) were similar to those used to previously to deplete FtsX (14) and are described in the supplemental methods. Following washing, final cultures were inoculated to an OD620 of ~0.001 in 5 ml of BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol), 0.05% (wt/vol), or no fucose, and growth was monitored by measuring the OD620 at 37°C. Cells were observed at various times by phase-contrast microscopy and were stained with fluorescent vancomycin and observed by epifluorescent microscopy as described before (14, 23).

Determination of relative cellular amounts of the PcsBA160P(Ts), PcsBW335G(Ts) and PcsBY387C(Ts) proteins.

Previously, we used quantitative Western blotting to show that the relative amount of the PcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) protein and its release into the growth medium were similar at the permissive (32°C) and nonpermissive (41.4°C) temperatures and resembled the pattern detected for the wild-type PcsB+ protein (14). We again used quantitative Western blotting with polyclonal anti-PcsB antibody to determine the relative cellular amounts and release of the PcsBA160P(Ts), PcsBW335G(Ts), and PcsBY387C(Ts) proteins (see Fig. S2 and the supplemental methods in the supplemental material). Cell morphologies were observed by phase-contrast microscopy in 32°C cultures before temperature shifts (t = 0) and ~100 min after shifts to 41.4°C, when samples were taken for Western blotting.

Isolation of pcsB(Ts) suppressors in ftsX.

A mutated “ftsEXM P-kan rpsL+” amplicon containing 0 to 4 mutations per kb was generated by error-prone PCR using primers listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material as described before (14), with the modifications described in the supplemental methods. Mutated ftsEXM P-kan rpsL+ amplicon was transformed into strains IU4261 (IU1945 pcsBL78S-L219P Pc-erm), IU4256 (IU1945 pcsBA160P Pc-erm), IU4081 (IU1945 pcsBW335G Pc-erm), and IU4262 (IU1945 pcsBY387C Pc-erm) at 32°C. Transformants were plated on BA containing 250 µg kanamycin per ml and incubated at 32°C or 41.4°C to obtain numbers of transformants or to select for suppressors of the pcsB(Ts) alleles, respectively. Control experiments showed that the reversion frequency of pcsB(Ts) mutations was negligible. Suppressor mutations in ftsX were confirmed by DNA sequencing and by backcrosses into the pcsB(Ts) mutant used for the selection, Allele specificity was determined by transformation into other pcsB(Ts) mutants.

Isolation of ftsX(Ts) mutants.

Mutated ftsEXM P-kan rpsL+ amplicon was transformed into strain IU1945 (D39 Δcps), and ftsX(Ts) mutants were screened by methods described in reference 14, with the modifications described in the supplemental methods.

Live-dead staining of pcsB and ftsX mutants in different growth phases.

Live-dead staining was performed using LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (Molecular Probes) as described before (39) with the modifications described in the supplemental methods.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental materials and methods. Download

Pneumococcal mutants with amino acid changes in the Walker motifs of FtsE show aberrant cell division. The Walker motif changes are illustrated in Fig. 1. Merodiploid strains IU6023 (IU1824 ftsEK43Q//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (A), IU6025 (IU1824 ftsED164A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (B), and IU6027 (IU1824 ftsEE165A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (C) were grown in BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose at 37°C and shifted to BHI broth lacking fucose at 37°C to deplete wild-type FtsE+ as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 2. After ~400 min, cells were concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 µl of room temperature BHI broth, stained with fluorescent vancomycin (Fl-Van), and visualized by epifluorescent microscopy (see Materials and Methods) (14; S. M. Barendt, A. D. Land, L. T. Sham, W. L. Ng, H. C. Tsui, R. J. Arnold, and M. E. Winkler, J. Bacteriol. 191:3024-3040, 2009; A. D. Land and M. E. Winkler, J. Bacteriol. 193:4166-4179, 2011). Bar, 2 µm. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Download

The relative amounts of cell-associated PcsB+, PcsBA160P, PcsBW335G, and PcsBY387C are unchanged in cells shifted from the permissive (32°C) to the nonpermissive (41.4°C) temperature. Strain IU1945 (D39 Δcps), IU4256 (IU1945 pcsBA160P Pc-erm), IU4081 (IU1945 pcsBW335G Pc-erm), and IU4262 (IU1945 pcsBY387C Pc-erm) were grown in BHI broth at 32°C to an OD620 of ~0.2. One set of cultures was shifted to 41.4°C, while the other set remained at 32°C. Cells were sampled before and ~120 min after the temperature shift, and relative amounts of exported PcsB in spent-medium supernatants (S) and attached to cells in pellets (P) were determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-PcsB antibody (see Materials and Methods) (14). There was more degradation of PcsBW335G and PcsBY387C than PcsB+ or PcsBA160P at both temperatures, but importantly, the fraction of cell-associated intact PcsBW335G and PcsBY387C did not vary at the two temperatures. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Download

Delay of stationary-phase autolysis in pcsBL78S-L219P and pcsBA160P mutants, but not in a pcsBW335G mutant. (A to C) Cultures of strains IU1945 (D39 Δcps), IU4081 (IU1945 pcsBW335G Pc-erm), IU4261 (IU1945 pcsBL78S-L219P Pc-erm), and IU4262 (IU1945 pcsBA160P Pc-erm) were grown overnight in BHI broth at 32°C (see Materials and Methods). Overnight cultures were used to inoculate fresh BHI broth cultures to an OD620 of ~0.005, which were grown at 32°C (A), 37°C (B), and 41.4°C (C). (D) Duplicate cultures of strains IU1945, IU4081, IU4261, IU4262, and IU3900 (IU1945 ΔlytA<>Pc-aad9) were grown as described for panel B at 37°C. At an OD620 of ~0.2, penicillin G (Pen-G) was added to a final concentration of 0.01 µg per ml to one set of cultures (arrow). Growth was monitored hourly for ~11 h, and a final density measurement was made the next day at ~74 h (broken curves). See the text for additional details. Download

Amino acid sequence alignment of ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX of different bacterial species. Alignment was done by ClustalW (J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins, Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics, Chapter 2, Unit 2.3, 2002) for the ECL1 and ECL2 regions of FtsX predicted in different bacterial species by the TMHMM program (14; A. Krogh, B. Larsson, G. von Heijne, and E. Sonnhammer, J. Mol. Biol. 305:567-580, 2001). Red circles indicate the positions of amino acid changes that suppress pcsBL78S-L219P or pcsBA160P(Ts) mutations in S. pneumoniae (see the internal legend and Fig. 1). Blue circles indicate the positions of amino acid changes that are allele specific for suppression of the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) mutation in S. pneumoniae. The green circle indicates the position of the ftsXI150K(Ts) mutation in S. pneumoniae. The 2 limited stretches of consecutive conserved amino acids in ECL1FtsX are marked by red lines. Sequences used in the alignment were retrieved from NCBI for representative strains, whose designations are given after the following abbreviations for bacteria: Lla, Lactococcus lactis; Spy, Streptococcus pyogenes; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Smi, Streptococcus mitis; Sth, Streptococcus thermophilus; Efa, Enterococcus faecalis; Ban, Bacillus anthracis; and Bsu, Bacillus subtilis. Download

Essentiality of FtsEX in different bacterial species.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

Primers used in this study.

Numbers of suppressor mutations and temperature-sensitive (Ts) mutations isolated in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tiffany Tsui, Krys Kazmierczak, and David Giedroc for information, comments, and helpful discussion about this work.

This work was supported by NIAID grant AI097289 to M.E.W. and by funds from the Indiana University Bloomington METACyt Initiative, funded in part by a major grant from the Lilly Endowment, to M.E.W.

The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

Citation Sham L-T, Jensen KR, Bruce KE, Winkler ME. 2013. Involvement of FtsE ATPase and FtsX extracellular loops 1 and 2 in FtsEX-PcsB complex function in cell division of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. mBio 4(4):e00431-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.00431-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Egan AJ, Vollmer W. 2013. The physiology of bacterial cell division. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1277:8–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sham LT, Tsui HC, Land AD, Barendt SM, Winkler ME. 2012. Recent advances in pneumococcal peptidoglycan biosynthesis suggest new vaccine and antimicrobial targets. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 15:194–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2012. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh SK, SaiSree L, Amrutha RN, Reddy M. 2012. Three redundant murein endopeptidases catalyse an essential cleavage step in peptidoglycan synthesis of Escherichia coli K12. Mol. Microbiol. 86:1036–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vollmer W. 2012. Bacterial growth does require peptidoglycan hydrolases. Mol. Microbiol. 86:1031–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. 2008. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32:259–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uehara T, Bernhardt TG. 2011. More than just lysins: peptidoglycan hydrolases tailor the cell wall. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14:698–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uehara T, Parzych KR, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2010. Daughter cell separation is controlled by cytokinetic ring-activated cell wall hydrolysis. EMBO J. 29:1412–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berg KH, Biørnstad TJ, Johnsborg O, Håvarstein LS. 2012. Properties and biological role of streptococcal fratricins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:3515–3522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Morlot C, Uehara T, Marquis KA, Bernhardt TG, Rudner DZ. 2010. A highly coordinated cell wall degradation machine governs spore morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 24:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wyckoff TJ, Taylor JA, Salama NR. 2012. Beyond growth: novel functions for bacterial cell wall hydrolases. Trends Microbiol. 20:540–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chou S, Bui NK, Russell AB, Lexa KW, Gardiner TE, LeRoux M, Vollmer W, Mougous JD. 2012. Structure of a peptidoglycan amidase effector targeted to gram-negative bacteria by the type VI secretion system. Cell. Rep. 1:656–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yang DC, Tan K, Joachimiak A, Bernhardt TG. 2012. A conformational switch controls cell wall-remodelling enzymes required for bacterial cell division. Mol. Microbiol. 85:768–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sham LT, Barendt SM, Kopecky KE, Winkler ME. 2011. Essential PcsB putative peptidoglycan hydrolase interacts with the essential FtsXSpn cell division protein in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:E1061–E1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang DC, Peters NT, Parzych KR, Uehara T, Markovski M, Bernhardt TG. 2011. An ATP-binding cassette transporter-like complex governs cell-wall hydrolysis at the bacterial cytokinetic ring. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:E1052–E1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crawford MA, Lowe DE, Fisher DJ, Stibitz S, Plaut RD, Beaber JW, Zemansky J, Mehrad B, Glomski IJ, Strieter RM, Hughes MA. 2011. Identification of the bacterial protein FtsX as a unique target of chemokine-mediated antimicrobial activity against Bacillus anthracis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:17159–17164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garti-Levi S, Hazan R, Kain J, Fujita M, Ben-Yehuda S. 2008. The FtsEX ABC transporter directs cellular differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 69:1018–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt KL, Peterson ND, Kustusch RJ, Wissel MC, Graham B, Phillips GJ, Weiss DS. 2004. A predicted ABC transporter, FtsEX, is needed for cell division in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:785–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Arends SJ, Kustusch RJ, Weiss DS. 2009. ATP-binding site lesions in FtsE impair cell division. J. Bacteriol. 191:3772–3784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reddy M. 2007. Role of FtsEX in cell division of Escherichia coli: viability of ftsEX mutants is dependent on functional SufI or high osmotic strength. J. Bacteriol. 189:98–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corbin BD, Wang Y, Beuria TK, Margolin W. 2007. Interaction between cell division proteins FtsE and FtsZ. J. Bacteriol. 189:3026–3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karimova G, Dautin N, Ladant D. 2005. Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J. Bacteriol. 187:2233–2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barendt SM, Land AD, Sham LT, Ng WL, Tsui HC, Arnold RJ, Winkler ME. 2009. Influences of capsule on cell shape and chain formation of wild-type and pcsB mutants of serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:3024–3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ng WL, Kazmierczak KM, Winkler ME. 2004. Defective cell wall synthesis in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6 depleted for the essential PcsB putative murein hydrolase or the VicR (YycF) response regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1161–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giefing-Kröll C, Jelencsics KE, Reipert S, Nagy E. 2011. Absence of pneumococcal PcsB is associated with overexpression of LysM domain containing proteins. Microbiology 157:1897–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. de Leeuw E, Graham B, Phillips GJ, ten Hagen-Jongman CM, Oudega B, Luirink J. 1999. Molecular characterization of Escherichia coli FtsE and FtsX. Mol. Microbiol. 31:983–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guiral S, Hénard V, Laaberki MH, Granadel C, Prudhomme M, Martin B, Claverys JP. 2006. Construction and evaluation of a chromosomal expression platform (CEP) for ectopic, maltose-driven gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiology 152:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manson MD. 2000. Allele-specific suppression as a tool to study protein-protein interactions in bacteria. Methods 20:18–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mellroth P, Daniels R, Eberhardt A, Rönnlund D, Blom H, Widengren J, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B. 2012. LytA, the major autolysin of Streptococcus pneumoniae, requires access to nascent peptidoglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 287:11018–11029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tomasz A, Waks S. 1975. Mechanism of action of penicillin: triggering of the pneumococcal autolytic enzyme by inhibitors of cell wall synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:4162–4166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peters NT, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. 2011. A fail-safe mechanism in the septal ring assembly pathway generated by the sequential recruitment of cell separation amidases and their activators. J. Bacteriol. 193:4973–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. García P, García JL, García E, Sánchez-Puelles JM, López R. 1990. Modular organization of the lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Gene 86:81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Alvarez FJ, Orelle C, Davidson AL. 2010. Functional reconstitution of an ABC transporter in nanodiscs for use in electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132:9513–9515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cui J, Davidson AL. 2011. ABC solute importers in bacteria. Essays Biochem. 50:85–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lanie JA, Ng WL, Kazmierczak KM, Andrzejewski TM, Davidsen TM, Wayne KJ, Tettelin H, Glass JI, Winkler ME. 2007. Genome sequence of Avery’s virulent serotype 2 strain D39 of Streptococcus pneumoniae and comparison with that of unencapsulated laboratory strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 189:38–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramos-Montañez S, Tsui HC, Wayne KJ, Morris JL, Peters LE, Zhang F, Kazmierczak KM, Sham LT, Winkler ME. 2008. Polymorphism and regulation of the spxB (pyruvate oxidase) virulence factor gene by a CBS-HotDog domain protein (SpxR) in serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 67:729–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsui HC, Mukherjee D, Ray VA, Sham LT, Feig AL, Winkler ME. 2010. Identification and characterization of noncoding small RNAs in Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 2 strain D39. J. Bacteriol. 192:264–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sung CK, Li H, Claverys JP, Morrison DA. 2001. An rpsL cassette, Janus, for gene replacement through negative selection in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5190–5196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wayne KJ, Li S, Kazmierczak KM, Tsui HC, Winkler ME. 2012. Involvement of WalK (VicK) phosphatase activity in setting WalR (VicR) response regulator phosphorylation level and limiting cross-talk in Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 cells. Mol. Microbiol. 86:645–660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental materials and methods. Download

Pneumococcal mutants with amino acid changes in the Walker motifs of FtsE show aberrant cell division. The Walker motif changes are illustrated in Fig. 1. Merodiploid strains IU6023 (IU1824 ftsEK43Q//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (A), IU6025 (IU1824 ftsED164A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (B), and IU6027 (IU1824 ftsEE165A//CEP::PfcsK-ftsE+) (C) were grown in BHI broth containing 0.8% (wt/vol) fucose at 37°C and shifted to BHI broth lacking fucose at 37°C to deplete wild-type FtsE+ as described in Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 2. After ~400 min, cells were concentrated by centrifugation and resuspended in 50 µl of room temperature BHI broth, stained with fluorescent vancomycin (Fl-Van), and visualized by epifluorescent microscopy (see Materials and Methods) (14; S. M. Barendt, A. D. Land, L. T. Sham, W. L. Ng, H. C. Tsui, R. J. Arnold, and M. E. Winkler, J. Bacteriol. 191:3024-3040, 2009; A. D. Land and M. E. Winkler, J. Bacteriol. 193:4166-4179, 2011). Bar, 2 µm. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Download

The relative amounts of cell-associated PcsB+, PcsBA160P, PcsBW335G, and PcsBY387C are unchanged in cells shifted from the permissive (32°C) to the nonpermissive (41.4°C) temperature. Strain IU1945 (D39 Δcps), IU4256 (IU1945 pcsBA160P Pc-erm), IU4081 (IU1945 pcsBW335G Pc-erm), and IU4262 (IU1945 pcsBY387C Pc-erm) were grown in BHI broth at 32°C to an OD620 of ~0.2. One set of cultures was shifted to 41.4°C, while the other set remained at 32°C. Cells were sampled before and ~120 min after the temperature shift, and relative amounts of exported PcsB in spent-medium supernatants (S) and attached to cells in pellets (P) were determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-PcsB antibody (see Materials and Methods) (14). There was more degradation of PcsBW335G and PcsBY387C than PcsB+ or PcsBA160P at both temperatures, but importantly, the fraction of cell-associated intact PcsBW335G and PcsBY387C did not vary at the two temperatures. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. Download

Delay of stationary-phase autolysis in pcsBL78S-L219P and pcsBA160P mutants, but not in a pcsBW335G mutant. (A to C) Cultures of strains IU1945 (D39 Δcps), IU4081 (IU1945 pcsBW335G Pc-erm), IU4261 (IU1945 pcsBL78S-L219P Pc-erm), and IU4262 (IU1945 pcsBA160P Pc-erm) were grown overnight in BHI broth at 32°C (see Materials and Methods). Overnight cultures were used to inoculate fresh BHI broth cultures to an OD620 of ~0.005, which were grown at 32°C (A), 37°C (B), and 41.4°C (C). (D) Duplicate cultures of strains IU1945, IU4081, IU4261, IU4262, and IU3900 (IU1945 ΔlytA<>Pc-aad9) were grown as described for panel B at 37°C. At an OD620 of ~0.2, penicillin G (Pen-G) was added to a final concentration of 0.01 µg per ml to one set of cultures (arrow). Growth was monitored hourly for ~11 h, and a final density measurement was made the next day at ~74 h (broken curves). See the text for additional details. Download

Amino acid sequence alignment of ECL1FtsX and ECL2FtsX of different bacterial species. Alignment was done by ClustalW (J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins, Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics, Chapter 2, Unit 2.3, 2002) for the ECL1 and ECL2 regions of FtsX predicted in different bacterial species by the TMHMM program (14; A. Krogh, B. Larsson, G. von Heijne, and E. Sonnhammer, J. Mol. Biol. 305:567-580, 2001). Red circles indicate the positions of amino acid changes that suppress pcsBL78S-L219P or pcsBA160P(Ts) mutations in S. pneumoniae (see the internal legend and Fig. 1). Blue circles indicate the positions of amino acid changes that are allele specific for suppression of the pcsBL78S-L219P(Ts) mutation in S. pneumoniae. The green circle indicates the position of the ftsXI150K(Ts) mutation in S. pneumoniae. The 2 limited stretches of consecutive conserved amino acids in ECL1FtsX are marked by red lines. Sequences used in the alignment were retrieved from NCBI for representative strains, whose designations are given after the following abbreviations for bacteria: Lla, Lactococcus lactis; Spy, Streptococcus pyogenes; Spn, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Smi, Streptococcus mitis; Sth, Streptococcus thermophilus; Efa, Enterococcus faecalis; Ban, Bacillus anthracis; and Bsu, Bacillus subtilis. Download

Essentiality of FtsEX in different bacterial species.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

Primers used in this study.

Numbers of suppressor mutations and temperature-sensitive (Ts) mutations isolated in this study.