Abstract

SIRT1 is a NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase that has a very large number of established protein substrates and an equally impressive list of biological functions thought to be regulated by its activity. Perhaps as notable is the remarkable number of points of conflict concerning the role of SIRT1 in biological processes. For example, evidence exists suggesting that SIRT1 is a tumor suppressor, is an oncogene, or has no effect on oncogenesis. Similarly, SIRT1 is variably reported to induce, inhibit, or have no effect on autophagy. We believe that the resolution of many conflicting results is possible by considering recent reports indicating that SIRT1 is an important hub interacting with a complex network of proteins that collectively regulate a wide variety of biological processes including cancer and autophagy. A number of the interacting proteins are themselves hubs that, like SIRT1, utilize intrinsically disordered regions for their promiscuous interactions. Many studies investigating SIRT1 function have been carried out on cell lines carrying undetermined numbers of alterations to the proteins comprising the SIRT1 network or on inbred mouse strains carrying fixed mutations affecting some of these proteins. Thus, the effects of modulating SIRT1 amount and/or activity are importantly determined by the genetic background of the cell (or the inbred strain of mice), and the effects attributed to SIRT1 are synthetic with the background of mutations and epigenetic differences between cells and organisms. Work on mice carrying alterations to the Sirt1 gene suggests that the network in which SIRT1 functions plays an important role in mediating physiological adaptation to various sources of chronic stress such as calorie restriction and calorie overload. Whether the catalytic activity of SIRT1 and the nuclear concentration of the co-factor, NAD+, are responsible for modulating this activity remains to be determined. However, the effect of modulating SIRT1 activity must be interpreted in the context of the cell or tissue under investigation. Indeed, for SIRT1, we argue that context is everything.

Keywords: scale-free network, protein deacetylation, nutritional stress, oncogenesis

The risk of many important diseases increases dramatically with age. Calorie restriction (CR) of experimental animals prolongs the life span and forestalls the onset of a remarkably diverse spectrum of diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative conditions, autoimmunity, and metabolic diseases including diabetes.1 Work on small eukaryotic organisms has established that the beneficial effects of CR depend on a class of enzymes called sirtuins. The working model is that CR activates sirtuin function. In mammals, SIRT1 is the most studied sirtuin. SIRT1 activity in human tissues normally declines with age,2 consistent with the idea that SIRT1 has a role in the age-dependent increase in disease susceptibility and with the notion that increasing SIRT1 activity might prolong the health span and resistance to age-dependent disease.

This article will attempt to resolve some of the many inconsistencies in the literature regarding the roles of SIRT1. It is our conviction that the intact organism is the appropriate one in which to investigate the physiological roles of SIRT1 and that genetic alteration to the endogenous Sirt1 gene constitutes the cleanest form of experimental manipulation. The reader is referred to a recent review of the sirtuin field3 for an excellent encyclopedic summary of the literature.

The Biochemistry of Sirtuins

The sirtuin family of proteins is characterized by the presence of a catalytic domain that couples NAD+ hydrolysis to protein deacetylation.4-6 This domain is found in genes of all animal and plant phyla.7-9 The yeast sir2 protein is the founding member of this family and is known to deacetylate histones H4 (K16Ac) and H3 (K9Ac) to facilitate the establishment of transcriptionally inactive chromatin.10,11 In addition, sir2 confers an enhanced resistance to cellular stresses and an increased replicative life span.12 The biochemical pathways responsible for these characteristics may be related to sir2-mediated inhibition of recombination between members of the ribosomal gene cluster13,14 or may be independent of chromatin effects.15 The sir2 orthologous genes in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster have also been reported to prolong the life span and increase organismal resistance to stress,16,17 although these observations, like many in the sirtuin field, are controversial.18

Of the 7 sirtuins encoded in the mammalian genome, the SIRT1 protein has the amino acid sequence most closely related to sir2 and is thought to be its ortholog. SIRT1 is a nuclear protein expressed in all tissues, albeit at variable levels,19 and it has been the object of intense study. Unlike other members of the sirtuin family, the core sirtuin domain of SIRT1 is insufficient for catalytic activity. Another 25–amino acid peptide called essential for SIRT1 activity (ESA) is also required for catalysis.20

The spectrum of acetylated protein substrates of SIRT1 is vast; at least 79 have been described (Table 1) including a large number of important nuclear proteins (such as p53, Rb, NF-κB, and CBP/p300) along with a variety of cytoplasmic proteins. The identification of cytoplasmic substrates for a protein that appears to be primarily nuclear in interphase cells is one of the many apparent paradoxes in the field. The SIRT1 enzyme is able to deacetylate acetyllysines in peptides with little context-dependent substrate specificity21 in vitro, so establishing what is and what is not a SIRT1 substrate can be problematic.

Table 1.

The Gene Products That Have Been Established as Acetylated Proteins Capable of Being Deacetylated by SIRT1 Either In Vivo, In Vitro, or Both

| SIRT1 substrates | |||||

| 14-3-3ξ146 | c-JUN65 | HIF1α147 | MeCP2148 | PDK1149 | STAT3150 |

| Ac-CoA synthase151 | c-MYC83 | HIF2α152 | MEF2D153 | PER237 | SUV39H1154 |

| AKT149 | Cortactin31 | Histone H1155 | MMP2156 | PGAM1157 | SV40 Tag158 |

| APE1159 | CREB160 | Histone H34 | MYST222 | PGC1α47,161 | TAT (HIV)162 |

| AR135 | DNMT1163 | Histone H44 | NBS1164 | PGC1β165 | Tau166 |

| ATG530 | eNOS167 | HMGSC1168 | NF-κB (p65)169 | PIP5Kγ170 | TIP5 (NCoR)171 |

| ATG730 | ERRα172 | hMOF25 | NHLH2173 | PPARγ174 | TIP6025,175 |

| ATG830 | FOXO1176 | HNF4α177 | NID178 | PTEN179 | TORC1180 |

| β-catenin144 | FOXO3A181 | HSF1182 | Nrf2183 | RARβ184 | WRN185 |

| BCL6186 | FOXO4187 | IRS2117,188 | p30023,181 | RB189 | XBP190 |

| BMAL138 | FOXP3191 | Ku70126,192 | p5326,27 | SATB1193 | XPA194 |

| CBP22 | FXR195 | LKB1196 | p73197 | SMAD7198 | YAP199 |

| CIITA200 | HIC1201 | LXR202 | PAX3203 | SREBP1c204 | Zyxin205 |

| RFX5206 | |||||

Note: Those proteins labeled in bold are normally cytoplasmic, while those not in bold are at least partially nuclear.

A recent investigation of the “acetylome” identified 485 acetylated peptides that are upregulated more than 2-fold in mouse embryo fibroblasts lacking SIRT1.22 However, unambiguous assignment of an acetylated protein as a SIRT1 substrate is complex because SIRT1 also negatively regulates the activities of a number of protein acetyltransferases (CBP/p300,23 Tip60,24 Myst1,25 and Myst222). Thus, ablating SIRT1 may increase the level of acetylation of a protein 1) because the protein is a substrate for SIRT1, 2) because the protein is acetylated by one of the protein acetyltransferases whose activity is modulated by SIRT1, or 3) for some other reason related to divergent paths by which the compared fibroblasts became immortalized in cell culture.

Biological Functions of SIRT1

In studies carried out primarily on cancer cells growing in culture, an impressive array of cellular processes has been shown to be regulated by SIRT1. These include apoptosis,26-29 autophagy,30 cell motility,31 drug resistance,32 genome stability,33 stress and drug resistance,32,34 chromatin structure and epigenetic regulation,35,36 and circadian rhythm.37,38 SIRT1 is required for the efficient differentiation of myoblasts,39,40 chondrocytes,41 endothelial cells,42 neural stem cells,43 mesenchymal stem cells,44 hematopoietic stem cells,45 and keratinocytes.46 In addition, whole animal studies indicate a role for SIRT1 in gluconeogenesis,47-49 metabolic syndrome,50,51 inflammation,52 and atherosclerosis.53

It is perhaps not surprising that so many cellular processes are dependent on SIRT1 function because the biochemical data indicate that SIRT1 has many substrates with very diverse functions. However, mice have been created with no detectable SIRT1 protein,54 a truncated SIRT1 lacking much of the catalytic domain,55 or a SIRT1 protein with no catalytic activity.56 Animals homozygous for mutant Sirt1 genes are born live and can survive to old age (more than 2 years) with modest or no compromise to the plethora of cellular functions described above as dependent on SIRT1.

Mice Carrying Genetically Modified Sirt1 Genes

No SIRT1 protein is detectable in Sirt1−/− cells carrying 2 knockout alleles.54 SIRT1-null mice develop in utero to term but have essentially 100% perinatal lethality when with an inbred genetic background. However, when carried with an outbred background, more than half of the SIRT1-null animals survive to adulthood, and some have lived for more than 2 years. One interpretation of the difference in survival with different genetic backgrounds is that the inbred backgrounds carry fixed mutations in genes that are synthetically lethal with the SIRT1-null state.

Efforts have been made to determine whether the neonatal lethality of the Sirt1−/− mice could be attributed to the failed regulation of p53, a well- established substrate of SIRT1. However, deletion of p53 in Sirt1−/− mice did not affect the Sirt1−/− phenotype,33,57 indicating that hyperactivation of p53 is not the source of the neonatal lethality of the SIRT1-null mice. Similarly, PARP has been reported to be regulated by SIRT1,58,59 but PARP deficiency does not rescue the Sirt1−/− phenotype.60 Also, the upregulation of IGFBP1 in Sirt1−/− mice19 appears not to be responsible for the neonatal lethal phenotype because IGFBP1 deficiency has no effect on the Sirt1−/− mice.61 Thus, we cannot attribute the neonatal lethality of the Sirt1−/− mice to deregulation of any one of these 3 proteins.

The Sirt1−/− adult mice that survive to adulthood do suffer from a number of rather subtle phenotypes including abnormally high basal metabolic rates,62 elevated rates of spontaneous activity,19 decreased fertility,54,63 elevated autoimmunity,64,65 craniofacial abnormalities,56 osteoarthritis,66 and compromised cognition67 and wakefulness.68 Although diverse and large in number, these phenotypes are much less severe than might be expected if one extrapolates from the cell culture results mentioned above.

Recently, we have created a mouse line carrying a point mutation in the SIRT1 gene (Sirt1Y, formally labeled Sirt1tm2.1Mcby) that encodes a SIRT1 protein with an H355Y substitution that ablates catalytic activity.56 Mice homozygous for this point mutation, Sirt1Y/Y, share with Sirt1−/− mice the phenotypes of small stature, elevated rates of respiration, and male infertility. However, these 2 mouse lines differ in other respects; for example, Sirt1−/− are female sterile, while Sirt1Y/Y are female fertile, and Sirt1−/− have an eyelid inflammatory phenotype, while Sirt1Y/Y mice generally do not. The difference between the phenotypes is sufficient to suggest that the SIRT1 protein may perform other functions in addition to protein deacetylation.

Confusion Surrounding SIRT1

Much of the literature involving SIRT1 is confusing and controversial. One reason is that many studies use resveratrol or SRT1720, a natural and a synthetic small molecule, respectively, which were initially reported to directly enhance the catalytic activity of SIRT1.50,69-72 The weight of evidence now indicates that neither resveratrol73,74 nor SRT172075,76 directly modulates the catalytic activity of the SIRT1 enzyme (although there may still be residual confusion regarding SRT172077). Resveratrol has been studied intensely and mimics CR in reducing the incidence and severity of a variety of experimentally induced diseases (including metabolic syndrome, cancer, and cardiovascular disease).78 The beneficial effects of resveratrol often require SIRT1,79 but the mechanism(s) responsible for the action of this drug remain controversial.78

A large number of transcription factors and co-factors have been reported to be regulated by SIRT1 (Table 1), so it is surprising that microarray80 and proteome analyses22 of cells lacking SIRT1 showed little difference from the wild type. In fact, the literature is full of conflicting results on the effects of SIRT1 on various biological processes. For example, the tumor suppressor p53 is a well-documented SIRT1 substrate whose transcription- and apoptosis-inducing activities were first reported to be inhibited by SIRT1,26,27,81 but subsequent studies failed to find any effect of SIRT1 on p53 function.57,82 The oncogene c-myc is another SIRT1 substrate that has been variously reported to be destabilized83,84 and to be stabilized85,86 by SIRT1-dependent deacetylation.

The literature linking SIRT1 to autophagy is also illustrative of the confusion and complexity that abounds in the SIRT1 literature. In 2008, it was first reported30 that SIRT1 activity stimulated autophagy and that autophagy was severely compromised in the absence of SIRT1. The contention that SIRT1 promotes autophagy was supported by a number of subsequent reports.87-90 Remarkably, however, several other reports have appeared showing that SIRT1 inhibits autophagy.91-93 Our own work with primary fibroblasts and neurons derived from our Sirt1−/− and Sirt1Y/Y mice showed no defect in autophagy induced by glucose deprivation (Caron et al., unpublished).

SIRT1 is a Protein Network Hub

Protein-protein interaction studies have established that SIRT1 can bind to a broad spectrum of proteins in addition to its known substrates (Table 2). In some cases, the SIRT1 protein regulates the function of the interacting partner (such as EGR194 and AP195), while in other cases, the interacting partner regulates SIRT1 activity (e.g., DBC196,97 and AROS98). A recent meta-analysis puts SIRT1 into an exclusive class of highly networked proteins with 136 primary nodes and 4,691 second-order nodes.99

Table 2.

A Partial List of Proteins That Can Bind to SIRT1 but Are Not Currently Established Substrates for SIRT1 Catalysis

| SIRT1 binding partners | ||||

| AP195 | AROS98 | CTIP2207 | DBC196,97 | E2F1208 |

| EGR194 | eIF-2209 | GCN5210 | HES1211 | HEY2211 |

| HSP70210 | MYOD39 | N-MYC113 | SOX941 | STAT3212 |

| TLE1213 | TRIM28210 | TSC2214 | USP22210 | |

Note: Those indicated in bold are cytoplasmic, while those not in bold are nuclear.

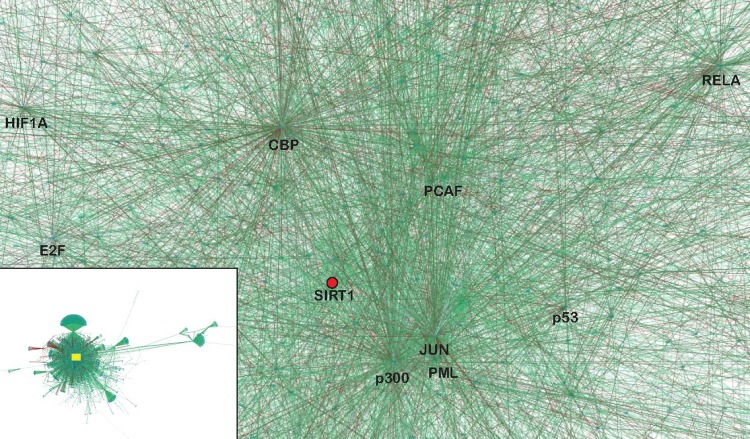

Protein association networks in eukaryotic cells are generally thought to be “scale-free” or “small-world” networks in that some highly connected nodes (hubs) can have hundreds, perhaps thousands, of interactions, while others have very few. SIRT1 is a scale-free network hub (Fig. 1), as are many of its interacting partners (p53, NF-κB, p300, c-myc, etc.). An important characteristic of a scale-free network is its robustness.100 The random loss of a node is unlikely to have severe consequences for the network because of the low probability that any node will be a hub. Even the loss of a hub is not necessarily lethal when there are enough other highly connected nodes in the vicinity of the affected hub to carry signaling information. This kind of redistribution of information flow through the scale-free network may explain the surprising viability of animals in which the function of a hub protein has been eliminated (e.g., p53-null mice). With the loss of a hub, the functioning of a scale-free network may be compromised in cryptic and unpredictable ways. These uncertainties are relevant in established cell lines where the loss of one or more hubs may confer an advantage in vitro (e.g., resistance to apoptosis).

Figure 1.

SIRT1 is a hub embedded in a network of hubs. The image depicts a portion of an edge-weighted, force-directed SIRT1 protein interaction network generated from public databases by Cytoscape.215 Edges represented as green lines refer to interactions reported in the BioGRID database. Edges represented as red lines refer to interactions reported in the HPRD database. The SIRT1 hub is represented as a red dot. The interactions depicted are a small subset of all interactions connected to SIRT1. The entire interaction network appears in the inset, with the location of the expanded region of interest indicated by the box.

The structure of the catalytic domain of model sirtuins has been solved,101 but computational methods applied to the full-length SIRT1 sequence indicate that the N- and C-terminal portions of the protein are largely unstructured,102 which is an observation consistent with the idea that SIRT1 can interact with a vast array of different proteins by “coupled binding and folding.” Bioinformatic analysis of proteins found to contain large unstructured regions (designated intrinsically disordered proteins, or IDPs) has revealed that they are highly enriched in proteins that are network hubs.103 The prevalence of IDPs as hub proteins is consistent with their property of binding with high specificity and low affinity.104 Disordered regions of hub proteins can adopt a variety of structures depending on the identity of the interacting partner protein; one disordered peptide within the p53 protein is known to adopt a β structure when complexed with a sirtuin, a short α helix when complexed with an S100 protein, and at least 2 other stable structures when complexed with other partners.105 The “restrained promiscuity” of hub proteins such as SIRT1 is thought to be a consequence of their disordered regions.

The SIRT1 Scale-Free Network Explains Inconsistencies

The literature is replete with studies claiming essential and critical roles for SIRT1 in various cellular processes3 including developmental processes (see above), so it is surprising that mice lacking SIRT1 or expressing SIRT1 without catalytic activity are only modestly compromised during embryogenesis. Indeed, most of their physiological processes seem to function normally even into adulthood. There is no evidence for compensatory increases in other sirtuins that might blunt the effect of the loss of SIRT1 function. Is it possible to reconcile the observations made in cell cultures with those made in whole animals?

There are obvious potential pitfalls associated with using pharmacological and RNAi reagents with an unappreciated lack of specificity.106 Also, ectopic expression of genes mediated by viral vectors is not without the hazard of nonspecific effects.107,108 However, we believe that the resolution to the apparently conflicting results lies with the fact that much of the published work was carried out on immortal cancer cell lines growing in culture. Each of these cell lines carries a unique collection of mutations (or epigenetic alterations) affecting such oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes such as p53, Rb, NF-κB, c-myc, and others. All of these proteins are part of the SIRT1 interaction network99 (indeed, these proteins are both SIRT1 substrates and binding partners), and each cell line will have a different set of compro- mised proteins depending on its differentiated state and on the mutations it sustained during the progression and acclimation to cell culture. Hence, the physiological effects seen in these cells are attributed by investigators to SIRT1, but our contention is that they really derive from the combination of defects in the other proteins comprising the interacting network as well as the introduced modulation to SIRT1. Thus, the physiological effect seen following SIRT1 modulation is really a synthetic phenotype dependent on some of the other alterations carried by the cell under investigation. One can imagine that the effect of compromising SIRT1 might have no effect in a wild-type background but could either cause the activation or repression of a physiological response depending on the state of the other proteins that comprise the network. Synthetic lethality is also a likely explanation of the neonatal lethality of Sirt1−/− and Sirt1Y/Y mice when carried on inbred mouse strains.56,109

SIRT1 has already been implicated in a number of regulatory feedback loops. These include those described for regulating SIRT1 activity and c-myc,85,110 p53,111 PPARγ,112 and N-myc.113 Many of the feedback loops or sources of SIRT1 regulation involve microRNAs, more than 23 of which are now reported to associate with the 1,800-nucleotide 3′ untranslated region of the SIRT1 transcript.114

Given the large number of pathways apparently governing SIRT1 abundance and activity, it seems prudent to consider SIRT1 to be a hub in a complex scale-free network rather than a critical node in a number of overlapping, independently functioning pathways. Any change in SIRT1 or its partner proteins will have ramifications affecting all of the surrounding network components, so we can expect that the notions of “upstream” and “downstream” in a signaling pathway do not apply.

Adaptation to Stress Is Compromised in Sirt1−/− Mice

Although laboratory-reared Sirt1−/− mice do have relatively minor anatomic and physiological deficits, these animals are notably more sensitive than the wild type when confronted with various chronic perturbations. For example, mice with compromised Sirt1 genes develop emphysema at elevated rates when forced to inhale cigarette smoke,91,115 develop atherosclerosis at higher rates,53 and are more prone to tissue destruction following exposure to ischemic insults to the heart116 and brain.117

Nutritional stress has been a favorite means of perturbing animals because chronic CR has well-established health benefits, and high calorie diets predispose to compromised health. When subject to CR, Sirt1+/+ mice adapt by upregulating their rates of respiration to acquire a new energy homeostatic steady state; however, the rates of respiration in CR Sirt1−/− 62 and Sirt1Y/Y 56 mice decrease in line with their reduced caloric intake, suggesting that these animals fail to adapt in the way that Sirt1+/+ mice do.

Excessive caloric intake results in obesity and predisposes to metabolic syndromes and diabetes. One report118 suggests that liver-specific knockout of SIRT1 protects mice from the adverse effects of high calorie diets, whereas most reports indicate that elevated liver SIRT1 is beneficial51,119,120 and SIRT1 deficiency121,122 exacerbates the defective glucose homeostasis and liver steatosis induced by the high fat diet.

A parsimonious interpretation of these observations on mice carrying Sirt1 mutations is that SIRT1 accelerates the physiological adaptation to chronic stress by being a member of a network that responds to low (nonlethal) levels of chronic stress by assuming different stable states and that the efficiency with which these transitions occur is dependent on SIRT1 and, one presumes, other components of the network. The fact that SIRT1 is a key node in the complex network of interacting proteins suggests that it plays an important role in allowing cells to transition between stable states during chronic perturbation.

How might SIRT1 effect an accelerated adaptation to chronic stress? One possibility derives from the observation that many sublethal stresses result in moderately elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) derived from mitochondria.123 One can imagine that ROS-mediated changes in cellular redox could elevate the nuclear concentration of NAD+ and hence provoke enhanced SIRT1 catalysis and/or modulate interactions with some of its network associates (indeed, H2O2 is known to modulate some of these interactions124). Alternatively, ROS could activate JNK2 to phosphorylate and stabilize SIRT1, as has been described.125

SIRT1 and Cancer

A number of original and review articles implicating SIRT1 in cancer development have appeared over the past several years.126 There appears to be evidence supporting the idea that SIRT1 is 1) a tumor suppressor, 2) an oncogene, or 3) neither.

A role for SIRT1 in cancer is suggested by the fact that many of its substrates are established oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, such as p53, p73, Rb, NF-κB, and c-myc. SIRT1 itself is regulated by tumor suppressor proteins HIC1, BRCA1, and p53 and the putative tumor suppressor DBC1. Many important physiological processes relevant to carcinogenesis are reported to be regulated by SIRT1. These include genome stability,33,127 immortalization and senescence,81,128-133 and apoptosis.134,135

In human malignancies, SIRT1 has been reported to be overexpressed in cancers of the colon, prostate, breast, ovary, stomach, liver, and pancreas as compared to normal tissue.136-139 In contrast, reduced expression has been reported in cancers of the colon, prostate, ovary, brain, and bladder and in BRCA1-associated breast cancers.33,136,140,141 The inconsistencies in these reports defy simple explanation.

The classic experimental test for oncogenes involves their transfection into primary or immortalized fibroblast cell lines.142 Neither the wild-type nor mutant Sirt1 gene has any activity in these assays.79

Genetically engineered mouse models created to overexpress or ablate SIRT1 expression have provided ambiguous evidence. On the one hand, transgenic mice that moderately overexpress SIRT1 were reported to develop slightly fewer spontaneous carcinomas and sarcomas,143 and mice that overexpress SIRT1 in intestinal epithelium developed fewer polyps in the APCmin mouse model of colon cancer.144 However, Sirt1−/− mice are not tumor prone, and Sirt1−/− animals do not develop more APCmin-dependent intestinal polyps or carcinogen-induced skin cancers when compared to their wild-type littermates.79

Although it was reported87 that young Sirt1-/- animals have prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), these mice have never been found to develop frank prostate cancer. In fact, the penetrance of PIN in these Sirt1-/- animals seems to be subject to some source of variability as yet undefined (Clark-Knowles, et al., unpublished).

Cancer is thought to proceed by the accumulation of mutations affecting oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (many of which are members of the network immediately connected to SIRT1). The clonal cancers that develop are often characterized as having acquired an addiction to,145 or dependence on, oncogenes. It is possible that SIRT1 might be one of the proteins to which the cancer cells become addicted since the spectrum of processes that SIRT1 influences in cancer cells in culture seems far more extensive than those that are affected by the loss of SIRT1 in whole animals. Thus, the synthetic phenotypes discussed above are simply another description of what cancer biologists call acquired dependencies.

Conclusion

The studies of SIRT1 define a field of enormous potential and of contradiction. The spectrum of diseases and physiological processes that have been reported to be modulated by SIRT1 is remarkably varied, yet the biochemical linkages between SIRT1 and the physiological readout are often obscure. Some clarity may emerge by considering SIRT1 as a member of a multicomponent protein/RNA network in which the modulation of SIRT1 has far-reaching consequences, well beyond what is normally considered in signal transduction pathways. Our interpretation of experiments carried out on whole animals is that SIRT1 functions primarily to facilitate the physiological adaptation of the organism to mild nonlethal stressors and that this function is served because SIRT1 is integral to a network of affiliate proteins and RNAs that comprise a robust network able to modulate its components to accommodate nutritional and physical perturbation. It seems likely that the modulation of SIRT1 activity by pharmacological means may achieve desirable outcomes, but the complexity of the network in which SIRT1 resides makes simple predictions imprudent.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Work from the authors’ laboratories was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1. Anderson RM, Weindruch R. The caloric restriction paradigm: implications for healthy human aging. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24(2):101-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Massudi H, Grant R, Braidy N, Guest J, Farnsworth B, Guillemin GJ. Age-associated changes in oxidative stress and NAD(+) metabolism in human tissue. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e42357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morris BJ. Seven sirtuins for seven deadly diseases of aging. Free Radic Biol Med. Epub 2012. October 24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403(6771):795-800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith JS, Brachmann CB, Celic I, et al. A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6658-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landry J, Sutton A, Tafrov ST, et al. The silencing protein SIR2 and its homologs are NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(11):5807-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brachmann CB, Sherman JM, Devine SE, Cameron EE, Pillus L, Boeke JD. The SIR2 gene family, conserved from bacteria to humans, functions in silencing, cell cycle progression, and chromosome stability. Genes Dev. 1995;9(23):2888-902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frye RA. Characterization of five human cDNAs with homology to the yeast SIR2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260(1):273-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frye RA. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273(2):793-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suka N, Luo K, Grunstein M. Sir2p and Sas2p opposingly regulate acetylation of yeast histone H4 lysine16 and spreading of heterochromatin. Nat Genet. 2002;32(3):378-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kimura A, Umehara T, Horikoshi M. Chromosomal gradient of histone acetylation established by Sas2p and Sir2p functions as a shield against gene silencing. Nat Genet. 2002;32(3):370-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guarente L. Sir2 links chromatin silencing, metabolism, and aging. Genes Dev. 2000;14(9):1021-6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13(19):2570-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salvi JS, Chan JN, Pettigrew C, Liu TT, Wu JD, Mekhail K. Enforcement of a lifespan-sustaining distribution of Sir2 between telomeres, mating-type loci, and rDNA repeats by Rif1. Aging Cell. Epub 2012. October 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Orlandi I, Bettiga M, Alberghina L, Nystrom T, Vai M. Sir2-dependent asymmetric segregation of damaged proteins in ubp10 null mutants is independent of genomic silencing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(5):630-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tissenbaum HA, Guarente L. Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;410(6825):227-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, et al. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300(5627):1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, et al. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 2011;477(7365):482-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lemieux ME, Yang X, Jardine K, et al. The Sirt1 deacetylase modulates the insulin-like growth factor signaling pathway in mammals. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126(10):1097-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kang H, Suh JY, Jung YS, Jung JW, Kim MK, Chung JH. Peptide switch is essential for sirt1 deacetylase activity. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2):203-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blander G, Olejnik J, Krzymanska-Olejnik E, et al. SIRT1 shows no substrate specificity in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11):9780-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Y, Zhao W, Yang JS, et al. Quantitative acetylome analysis reveals the roles of SIRT1 in regulating diverse substrates and cellular pathways. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(10):1048-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bouras T, Fu M, Sauve AA, et al. SIRT1 deacetylation and repression of P300 involves lysine residues 1020/1024 within the cell-cycle regulatory domain 1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11): 10264-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang J, Chen J. SIRT1 regulates autoacetylation and HAT activity of Tip60. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(15):11458-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peng L, Ling H, Yuan Z, et al. SIRT1 negatively regulates the activities, functions, and protein levels of hMOF and TIP60. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(14):2823-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo J, Nikolaev AY, Imai S, et al. Negative control of p53 by Sir2alpha promotes cell survival under stress. Cell. 2001;107(2):137-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Eaton EN, et al. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 2001;107(2):149-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jin Q, Yan T, Ge X, Sun C, Shi X, Zhai Q. Cytoplasm-localized SIRT1 enhances apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213(1):88-97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lara E, Mai A, Calvanese V, et al. Salermide, a sirtuin inhibitor with a strong cancer-specific proapoptotic effect. Oncogene. 2009;28(6):781-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, et al. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. PNAS. 2008;105(9):3374-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Y, Zhang M, Dong H, et al. Deacetylation of cortactin by SIRT1 promotes cell migration. Oncogene. 2009;28(3):445-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chu F, Chou PM, Zheng X, Mirkin BL, Rebbaa A. Control of multidrug resistance gene mdr1 and cancer resistance to chemotherapy by the longevity gene sirt1. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang RH, Sengupta K, Li C, et al. Impaired DNA damage response, genome instability, and tumorigenesis in SIRT1 mutant mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(4):312-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raval AP, Dave KR, Perez-Pinzon MA. Resveratrol mimics ischemic preconditioning in the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26(9):1141-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pruitt K, Zinn RL, Ohm JE, et al. Inhibition of SIRT1 reactivates silenced cancer genes without loss of promoter DNA hypermethylation. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(3):e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Hagan HM, Mohammad HP, Baylin SB. Double strand breaks can initiate gene silencing and SIRT1-dependent onset of DNA methylation in an exogenous promoter CpG island. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(8):e1000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, et al. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134(2):317-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nakahata Y, Kaluzova M, Grimaldi B, et al. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell. 2008;134(2):329-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fulco M, Schiltz RL, Iezzi S, et al. Sir2 regulates skeletal muscle differentiation as a potential sensor of the redox state. Mol Cell. 2003;12(1):51-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fulco M, Cen Y, Zhao P, et al. Glucose restriction inhibits skeletal myoblast differentiation by activating SIRT1 through AMPK-mediated regulation of Nampt. Dev Cell. 2008;14(5):661-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dvir-Ginzberg M, Gagarina V, Lee EJ, Hall DJ. Regulation of cartilage-specific gene expression in human chondrocytes by SirT1 and NAMPT. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(52):36300-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Potente M, Ghaeni L, Baldessari D, et al. SIRT1 controls endothelial angiogenic functions during vascular growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21(20): 2644-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prozorovski T, Schulze-Topphoff U, Glumm R, et al. Sirt1 contributes critically to the redox-dependent fate of neural progenitors. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(4):385-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Backesjo CM, Li Y, Lindgren U, Haldosen LA. Activation of sirt1 decreases adipocyte formation during osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(7):993-1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Matsui K, Ezoe S, Oritani K, et al. NAD-dependent histone deacetylase, SIRT1, plays essential roles in the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012; 418(4):811-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Blander G, Bhimavarapu A, Mammone T, et al. SIRT1 promotes differentiation of normal human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(1):41-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1[alpha] and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434(7029):113-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rodgers JT, Puigserver P. Fasting-dependent glucose and lipid metabolic response through hepatic sirtuin 1. PNAS. 2007;104(31):12861-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liu Y, Dentin R, Chen D, et al. A fasting inducible switch modulates gluconeogenesis via activator/coactivator exchange. Nature. 2008;456(7219):269-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;450(7170):712-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pfluger PT, Herranz D, Velasco-Miguel S, Serrano M, Tschop MH. Sirt1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(28):9793-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang SR, Wright J, Bauter M, Seweryniak K, Kode A, Rahman I. Sirtuin regulates cigarette smoke induced pro-inflammatory mediators release via RelA/p65 NF-{kappa}B in macrophages in vitro and in rat lungs in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L567-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stein MA, Lohmann C, Schafer N, et al. SIRT1 protects against atherosclerosis by decreasing macrophage infiltration and foam cell formation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(18):2301-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McBurney MW, Yang X, Jardine K, et al. The mammalian SIR2alpha protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(1):38-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, et al. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. PNAS. 2003;100(19):10794-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Seifert EL, Caron AZ, Morin K, et al. SirT1 catalytic activity is required for male fertility and metabolic homeostasis in mice. FASEB J. 2012;26(2):555-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kamel C, Abrol M, Jardine K, He X, McBurney MW. SirT1 fails to affect p53-mediated biological functions. Aging Cell. 2006;5(1):81-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kolthur-Seetharam U, Dantzer F, McBurney MW, de Murcia G, Sassone-Corsi P. Control of AIF-mediated cell death by the functional interplay of SIRT1 and PARP-1 in response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(8):873-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rajamohan SB, Pillai VB, Gupta M, et al. SIRT1 promotes cell survival under stress by deacetylation-dependent deactivation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(15):4116-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. El Ramy R, Magroun N, Messadecq N, et al. Functional interplay between Parp-1 and SirT1 in genome integrity and chromatin-based processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(19):3219-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Boily G, He XH, Jardine K, McBurney MW. Disruption of Igfbp1 fails to rescue the phenotype of Sirt1-/- mice. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(13):2189-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Boily G, Seifert EL, Bevilacqua L, et al. SirT1 regulates energy metabolism and response to caloric restriction in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3):e1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kolthur-Seetharam U, Teerds K, de Rooij DG, et al. The histone deacetylase SIRT1 controls male fertility in mice through regulation of hypothalamic-pituitary gonadotropin signaling. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(2):384-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sequeira J, Boily G, Bazinet S, et al. sirt1-null mice develop an autoimmune-like condition. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314(16):3069-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang J, Lee SM, Shannon S, et al. The type III histone deacetylase Sirt1 is essential for maintenance of T cell tolerance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(10):3048-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gabay O, Sanchez C, Dvir-Ginzberg M, et al. Sirt1 enzymatic activity is required for cartilage homeostasis in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1): 159-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Michan S, Li Y, Chou MM, et al. SIRT1 is essential for normal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30(29):9695-707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Panossian L, Fenik P, Zhu Y, Zhan G, McBurney MW, Veasey S. SIRT1 regulation of wakefulness and senescence-like phenotype in wake neurons. J Neurosci. 2011;31(11):4025-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425(6954):191-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Feige JN, Lagouge M, Canto C, et al. Specific SIRT1 activation mimics low energy levels and protects against diet-induced metabolic disorders by enhancing fat oxidation. Cell Metab. 2008;8(5):347-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yamazaki Y, Usui I, Kanatani Y, et al. Treatment with SRT1720, a SIRT1 activator, ameliorates fatty liver with reduced expression of lipogenic enzymes in MSG mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(5):E1179-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Minor RK, Baur JA, Gomes AP, et al. SRT1720 improves survival and healthspan of obese mice. Sci Rep. 2011;1:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kaeberlein M, McDonagh T, Heltweg B, et al. Substrate specific activation fo sirtuins by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):17038-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(17):17187-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pacholec M, Chrunyk BA, Cunningham D, et al. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(11):8340-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Huber JL, McBurney MW, DiStefano PS, McDonagh T. SIRT1-independent mechanisms of the putative sirtuin enzyme activators SRT1720 and SRT2183. Future Med Chem. 2010;2(12):1751-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dai H, Kustigian L, Carney D, et al. SIRT1 activation by small molecules: kinetic and biophysical evidence for direct interaction of enzyme and activator. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(43):32695-703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nakata R, Takahashi S, Inoue H. Recent advances in the study on resveratrol. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(3):273-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Boily G, He XH, Pearce B, Jardine K, McBurney MW. SirT1-null mice develop tumors at normal rates but are poorly protected by resveratrol. Oncogene. 2009;28:2882-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. McBurney MW, Yang X, Jardine K, Bieman M, Th’ng J, Lemieux M. The absence of SIR2alpha protein has no effect on global gene silencing in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1(5):402-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Langley E, Pearson M, Faretta M, et al. Human SIR2 deacetylates p53 and antagonizes PML/p53-induced cellular senescence. EMBO J. 2002;21(10):2383-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Solomon JM, Pasupuleti R, Xu L, et al. Inhibition of SIRT1 catalytic activity increases p53 acetylation but does not alter cell survival following DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(1):28-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yuan J, Minter-Dykhouse K, Lou Z. A c-Myc-SIRT1 feedback loop regulates cell growth and transformation. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(2):203-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Xie Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, Shao C. SirT1 confers hypoxia-induced radioresistance via the modulation of c-Myc stabilization on hepatoma cells. J Radiat Res (Tokyo). 2012;53(1):44-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Menssen A, Hydbring P, Kapelle K, et al. The c-MYC oncoprotein, the NAMPT enzyme, the SIRT1-inhibitor DBC1, and the SIRT1 deacetylase form a positive feedback loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;109(4):E187-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Herranz D, Maraver A, Canamero M, et al. SIRT1 promotes thyroid carcinogenesis driven by PTEN deficiency. Oncogene. Epub 2012. September 17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Powell MJ, Casimiro MC, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Disruption of a Sirt1 dependent autophagy checkpoint in the prostate results in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesion formation. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):964-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hariharan N, Maejima Y, Nakae J, Paik J, DePinho RA, Sadoshima J. Deacetylation of FoxO by Sirt1 plays an essential role in mediating starvation-induced autophagy in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;107(12):1470-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jeong JK, Moon MH, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Park SY. Autophagy induced by the class III histone deacetylase Sirt1 prevents prion peptide neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(1):146-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jang SY, Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide-induced mitophagy: an event mediated by high NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19304-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, et al. Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy is regulated by SIRT1-PARP-1-dependent mechanism: implication in pathogenesis of COPD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500(2):203-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang Z, Lowry SF, Guarente L, Haimovich B. Roles of Sirt1 in the acute and restorative phases following induction of inflammation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(53):41391-401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Wang J, Kim TH, Ahn MY, et al. Sirtinol, a class III HDAC inhibitor, induces apoptotic and autophagic cell death in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(3):1101-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pardo PS, Boriek AM. An autoregulatory loop reverts the mechanosensitive Sirt1 induction by EGR1 in skeletal muscle cells. Aging (Albany NY). 2012;4(7):456-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gao Z, Ye J. Inhibition of transcriptional activity of c-JUN by SIRT1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376(4):793-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kim JE, Chen J, Lou Z. DBC1 is a negative regulator of SIRT1. Nature. 2008;451(7178):583-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhao W, Kruse JP, Tang Y, Jung SY, Qin J, Gu W. Negative regulation of the deacetylase SIRT1 by DBC1. Nature. 2008;451(7178):587-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kim EJ, Kho JH, Kang MR, Um SJ. Active regulator of SIRT1 cooperates with SIRT1 and facilitates suppression of p53 activity. Mol Cell. 2007;28(2):277-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sharma A, Gautam V, Costantini S, Paladino A, Colonna G. Interactomic and pharmacological insights on human sirt-1. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Barabasi AL, Bonabeau E. Scale-free networks. Sci Am. 2003;288(5):60-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Avalos JL, Celic I, Muhammad S, Cosgrove MS, Boeke JD, Wolberger C. Structure of a Sir2 enzyme bound to an acetylated p53 peptide. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):523-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Autiero I, Costantini S, Colonna G. Human sirt-1: molecular modeling and structure-function relationships of an unordered protein. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(10):e7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Iakoucheva LM, Brown CJ, Lawson JD, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;323(3):573-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Dunker AK, Cortese MS, Romero P, Iakoucheva LM, Uversky VN. Flexible nets: the roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. FEBS J. 2005;272(20):5129-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Uversky VN, Oldfield CJ, Dunker AK. Intrinsically disordered proteins in human diseases: introducing the D2 concept. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:215-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Kaelin WG. Molecular biology: use and abuse of RNAi to study mammalian gene function. Science. 2012;337(6093):421-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Yamagata Y, Parietti V, Stockholm D, et al. Lentiviral transduction of CD34(+) cells induces genome-wide epigenetic modifications. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lee J, Sayed N, Hunter A, et al. Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2012;151(3):547-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. McBurney MW, Yang X, Jardine K, et al. The mammalian SIR2α protein has a role in embryogenesis and gametogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(1):38-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Yuan J, Minter-Dykhouse K, Lou Z. A c-Myc-SIRT1 feedback loop regulates cell growth and transformation. J Cell Biol. 2009;185(2):203-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Yamakuchi M, Lowenstein CJ. MiR-34, SIRT1 and p53: the feedback loop. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(5):712-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Han L, Zhou R, Niu J, McNutt MA, Wang P, Tong T. SIRT1 is regulated by a PPAR{gamma}-SIRT1 negative feedback loop associated with senescence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(21):7458-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Marshall GM, Liu PY, Gherardi S, et al. SIRT1 promotes N-Myc oncogenesis through a positive feedback loop involving the effects of MKP3 and ERK on N-Myc protein stability. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(6):e1002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Yamakuchi M. MicroRNA regulation of SIRT1. Front Physiol. 2012;3:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Yao H, Chung S, Hwang JW, et al. SIRT1 protects against emphysema via FOXO3-mediated reduction of premature senescence in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(6):2032-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Nadtochiy SM, Yao H, McBurney MW, et al. SIRT1 mediated acute cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(4):H1506-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Li Y, Xu W, McBurney MW, Longo VD. SirT1 inhibition reduces IGF-I/IRS-2/Ras/ERK1/2 signaling and protects neurons. Cell Metab. 2008;8(1):38-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Chen D, Bruno J, Easlon E, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of SIRT1 by calorie restriction. Genes Dev. 2008;22(13):1753-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Banks AS, Kon N, Knight C, et al. SirT1 gain of function increases energy efficiency and prevents diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2008;8(4):333-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Escande C, Chini CCS, Nin V, et al. Deleted in breast cancer-1 regulates SIRT1 activity and contributes to high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(2):545-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, Guo X, Li X. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009;9(4):327-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wang RH, Li C, Deng CX. Liver steatosis and increased ChREBP expression in mice carrying a liver specific SIRT1 null mutation under a normal feeding condition. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6(7):682-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Sena LA, Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell. 2012;48(2):158-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303(5666):2011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Ford J, Ahmed S, Allison S, Jiang M, Milner J. JNK2-dependent regulation of SIRT1 protein stability. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(19):3091-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305(5682):390-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Oberdoerffer P, Michan S, McVay M, et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135(5):907-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Sasaki T, Maier B, Bartke A, Scrable H. Progressive loss of SIRT1 with cell cycle withdrawal. Aging Cell. 2006;5(5):413-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Ota H, Tokunaga E, Chang K, et al. Sirt1 inhibitor, sirtinol, induces senescence-like growth arrest with attenuated Ras-MAPK signaling in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2006;25(2):176-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann J, Lal A, et al. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol Cell. 2007;25(4):543-57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. van der Veer E, Ho C, O’Neil C, et al. Extension of human cell lifespan by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):10841-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Huang J, Gan Q, Han L, et al. SIRT1 overexpression antagonizes cellular senescence with activated ERK/S6k1 signaling in human diploid fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(3):e1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Chua KF, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, et al. Mammalian SIRT1 limits replicative life span in response to chronic genotoxic stress. Cell Metab. 2005;2(1):67-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Ford J, Jiang M, Milner J. Cancer-specific functions of SIRT1 enable human epithelial cancer cell growth and survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10457-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Fu M, Liu M, Sauve AA, et al. The hormonal control of androgen receptor function through SIRT1. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(21):8122-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Kabra N, Li Z, Chen L, et al. SirT1 is an inhibitor of proliferation and tumor formation in colon cancer. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(27):18210-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Stunkel W, Peh BK, Tan YC, et al. Function of the SIRT1 protein deacetylase in cancer. Biotechnol J. 2007;2(11):1360-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Wu M, Wei W, Xiao X, et al. Expression of SIRT1 is associated with lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in both operable triple-negative and non-triple-negative breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29(5):3240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Jang KY, Kim KS, Hwang SH, et al. Expression and prognostic significance of SIRT1 in ovarian epithelial tumours. Pathology. 2009;41(4):366-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Jang SH, Min KW, Paik SS, Jang KS. Loss of SIRT1 histone deacetylase expression associates with tumour progression in colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(8):735-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Wang RH, Zheng Y, Kim HS, et al. Interplay among BRCA1, SIRT1, and survivin during BRCA1-associated tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2008;32(1):11-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Tumourigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1986;304:596-601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Herranz D, Munoz-Martin M, Canamero M, et al. Sirt1 improves healthy ageing and protects from metabolic syndrome-associated cancer. Nat Commun. 2010;1(1):1-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Firestein R, Blander G, Michan S, et al. The SIRT1 deacetylase suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis and colon cancer growth. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):e2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Weinstein IB, Joe A. Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3077-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Andersen JL, Thompson JW, Lindblom KR, et al. A biotin switch-based proteomics approach identifies 14-3-3zeta as a target of sirt1 in the metabolic regulation of caspase-2. Mol Cell. 2011;43(5):834-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Lim JH, Lee YM, Chun YS, Chen J, Kim JE, Park JW. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell. 2010;38(6):864-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Zocchi L, Sassone-Corsi P. SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of MeCP2 contributes to BDNF expression. Epigenetics. 2012;7(7):695-700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Sundaresan NR, Pillai VB, Wolfgeher D, et al. The deacetylase SIRT1 promotes membrane localization and activation of Akt and PDK1 during tumorigenesis and cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Signal. 2011;4(182):ra46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Sestito R, Madonna S, Scarponi C, et al. STAT3-dependent effects of IL-22 in human keratinocytes are counterregulated by sirtuin 1 through a direct inhibition of STAT3 acetylation. FASEB J. 2010;25(3):916-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM. Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-CoA synthetases. PNAS. 2006;103(27):10230-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Dioum EM, Chen R, Alexander MS, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2{alpha} signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science. 2009;324(5932):1289-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Zhao X, Sternsdorf T, Bolger TA, Evans RM, Yao TP. Regulation of MEF2 by histone deacetylase 4- and SIRT1 deacetylase-mediated lysine modifications. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(19):8456-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Vaquero A, Scher M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Serrano L, Reinberg D. SIRT1 regulates the histone methyl-transferase SUV39H1 during heterochromatin formation. Nature. 2007;450(7168):440-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Das C, Lucia MS, Hansen KC, Tyler JK. CBP/p300-mediated acetylation of histone H3 on lysine 56. Nature. 2009;459(7243):113-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Lovaas JD, Zhu L, Chiao CY, Byles V, Faller DV, Dai Y. SIRT1 enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression and tumor cell invasion in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. Epub 2012. October 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Hallows WC, Yu W, Denu JM. Regulation of glycolytic enzyme phosphoglycerate mutase-1 by Sirt1-mediated deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2011;287(6):3850-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Shimazu T, Komatsu Y, Nakayama KI, Fukazawa H, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Regulation of SV40 large T-antigen stability by reversible acetylation. Oncogene. 2006;25(56):7391-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Yamamori T, DeRicco J, Naqvi A, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates APE1 and regulates cellular base excision repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(3):832-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Qiang L, Lin HV, Kim-Muller JY, Welch CL, Gu W, Accili D. Proatherogenic abnormalities of lipid metabolism in SirT1 transgenic mice are mediated through creb deacetylation. Cell Metab. 2011;14(6):758-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. SIRT1 functionally interacts with the metabolic regulator and transcriptional coactivator PGC-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(16):16456-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Pagans S, Pedal A, North BJ, et al. SIRT1 regulates HIV transcription via Tat deacetylation. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(2):e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Peng L, Yuan Z, Ling H, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates the DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) protein and alters its activities. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(23):4720-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Yuan Z, Zhang X, Sengupta N, Lane WS, Seto E. SIRT1 regulates the function of the Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein. Mol Cell. 2007;27(1):149-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Kelly TJ, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Puigserver P. GCN5-mediated transcriptional control of the metabolic coactivator PGC-1beta through lysine acetylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):19945-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Min SW, Cho SH, Zhou Y, et al. Acetylation of tau inhibits its degradation and contributes to tauopathy. Neuron. 2010;67(6):953-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Mattagajasingh I, Kim CS, Naqvi A, et al. SIRT1 promotes endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation by activating endothelial nitric oxide synthase. PNAS. 2007;104(37):14855-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Capra JA, Pollard KS, Verdin E. SIRT1 and SIRT3 deacetylate homologous substrates: AceCS1,2 and HMGCS1,2. Aging (Albany NY). 2011;3(6):635-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, et al. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004;23(12):2369-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Akieda-Asai S, Zaima N, Ikegami K, et al. SIRT1 regulates thyroid-stimulating hormone release by enhancing PIP5Kgamma activity through deacetylation of specific lysine residues in mammals. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(7):e11755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Zhou Y, Schmitz KM, Mayer C, Yuan X, Akhtar A, Grummt I. Reversible acetylation of the chromatin remodelling complex NoRC is required for non-coding RNA-dependent silencing. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(8):1010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Wilson BJ, Tremblay AM, Deblois G, Sylvain-Drolet G, Giguere V. An acetylation switch modulates the transcriptional activity of estrogen-related receptor {alpha}. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(7):1349-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Libert S, Pointer K, Bell EL, et al. SIRT1 activates MAO-A in the brain to mediate anxiety and exploratory drive. Cell. 2011;147(7):1459-72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Qiang L, Wang L, Kon N, et al. Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Ppargamma. Cell. 2012;150(3):620-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Yamagata K, Kitabayashi I. Sirt1 physically interacts with Tip60 and negatively regulates Tip60-mediated acetylation of H2AX. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390(4):1355-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Yang Y, Hou H, Haller EM, Nicosia SV, Bai W. Suppression of FOXO1 activity by FHL2 through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation. EMBO J. 2005;24(5):1021-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Yang J, Kong X, Martins-Santos ME, et al. The activation of SIRT1 by resveratrol represses transcription of the gene for the cytosolic form of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) by deacetylating HNF4alpha. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(40):27042-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Guarani V, Deflorian G, Franco CA, et al. Acetylation-dependent regulation of endothelial Notch signalling by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Nature. 2011;473(7346):234-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179. Ikenoue T, Inoki K, Zhao B, Guan KL. PTEN acetylation modulates its interaction with PDZ domain. Cancer Res. 2008;68(17):6908-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180. Jeong H, Cohen DE, Cui L, et al. Sirt1 mediates neuroprotection from mutant huntingtin by activation of the TORC1 and CREB transcriptional pathway. Nat Med. 2011;18(1):159-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181. Motta MC, Divecha N, Lemieux M, et al. Mammalian SIRT1 represses forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2004;116:551-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182. Westerheide SD, Anckar J, Stevens SM, Sistonen L, Morimoto RI. Stress-inducible regulation of heat shock factor 1 by the deacetylase SIRT1. Science. 2009;323(5917):1063-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 183. Kawai Y, Garduno L, Theodore M, Yang J, Arinze IJ. Acetylation-deacetylation of the transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) regulates its transcriptional activity and nucleo-cytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem. 2010;286(9):7629-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 184. Donmez G, Wang D, Cohen DE, Guarente L. SIRT1 suppresses beta-amyloid production by activating the alpha-secretase gene ADAM10. Cell. 2010;142(2):320-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 185. Li K, Casta A, Wang R, et al. Regulation of WRN protein cellular localization and enzymatic activities by SIRT1 mediated deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(12):7590-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 186. Bereshchenko OR, Gu W, Dalla-Favera R. Acetylation inactivates the transcriptional repressor BCL6. Nat Genet. 2002;32(4):606-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 187. van der Horst A, Tertoolen LGJ, Vries-Smits LMM, Frye RA, Medema RH, Burgering BMT. FOXO4 is acetylated upon peroxide stress and deacetylated by the longevity protein hSir2SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):28873-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 188. Zhang J. The direct involvement of SirT1 in insulin-induced IRS-2 tyrosine phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(47):34356-64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 189. Wong S, Weber JD. Deacetylation of the retinoblastoma tumour suppressor protein by SIRT1. Biochem J. 2007;407(3):451-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 190. Wang FM, Ouyang HJ. Regulation of unfolded protein response modulator XBP1s by acetylation and deacetylation. Biochem J. 2011;433(1):245-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 191. van Loosdregt J, Vercoulen Y, Guichelaar T, et al. Regulation of Treg functionality by acetylation-mediated Foxp3 protein stabilization. Blood. 2010;115(5):965-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 192. Jeong J, Juhn K, Lee H, et al. SIRT1 promotes DNA repair activity and deacetylation of Ku70. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39(1):8-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 193. Xue Z, Lv X, Song W, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates SATB1 to facilitate MARHS2-MAR{epsilon} interaction and promote {epsilon}-globin expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(11):4804-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 194. Fan W, Luo J. SIRT1 regulates UV-induced DNA repair through deacetylating XPA. Mol Cell. 2010;39(2):247-58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 195. Kemper JK, Xiao Z, Ponugoti B, et al. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metab. 2009;10(5):392-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 196. Lan F, Cacicedo JM, Ruderman N, Ido Y. SIRT1 modulation of the acetylation status, cytosolic localization and activity of LKB1: possible role in AMP-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(41):27628-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 197. Dai JM, Wang ZY, Sun DC, Lin RX, Wang SQ. SIRT1 interacts with p73 and suppresses p73-dependent transcriptional activity. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(1):161-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 198. Kume S, Haneda M, Kanasaki K, et al. SIRT1 inhibits TGFbeta-induced apoptosis in glomerular mesangial cells via Smad7 deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(1):151-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 199. Hata S, Hirayama J, Kajiho H, et al. A novel acetylation cycle of transcription co-activator Yes-associated protein that is downstream of Hippo pathway is triggered in response to SN2 alkylating agents. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(26):22089-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 200. Wu X, Kong X, Chen D, et al. SIRT1 links CIITA deacetylation to MHC II activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(22):9549-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 201. Stankovic-Valentin N, Deltour S, Seeler J, et al. An acetylation/deacetylation-SUMOylation switch through a phylogenetically conserved {psi}KxEP motif in the tumor suppressor HIC1 (hypermethylated in cancer 1) regulates transcriptional repression activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(7):2661-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 202. Li X, Zhang S, Blander G, Tse JG, Krieger M, Guarente L. SIRT1 deacetylates and positively regulates the nuclear receptor LXR. Mol Cell. 2007;28(1):91-106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 203. Ichi S, Boshnjaku V, Shen YW, et al. Role of Pax3 acetylation in the regulation of Hes1 and Neurog2. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(4):503-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 204. Ponugoti B, Kim DH, Xiao Z, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates and inhibits SREBP-1C activity in regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(44):33959-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 205. Fujita Y, Yamaguchi A, Hata K, Endo M, Yamaguchi N, Yamashita T. Zyxin is a novel interacting partner for SIRT1. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 206. Xia J, Wu X, Yang Y, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates RFX5 and antagonizes repression of collagen type I (COL1A2) transcription in smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;428(2):264-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 207. Senawong T, Peterson VJ, Avram D, et al. Involvement of the histone deacetylase SIRT1 in COUP-TF-interacting protein 2-mediated transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(44):43041-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 208. Wang C, Chen L, Hou X, et al. Interactions between E2F1 and SirT1 regulate apoptotic response to DNA damage. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(9):1025-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 209. Ghosh HS, Reizis B, Robbins PD. SIRT1 associates with eIF2-alpha and regulates the cellular stress response. Sci Rep. 2011;1:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 210. Lin Z, Yang H, Kong Q, et al. USP22 antagonizes p53 transcriptional activation by deubiquitinating Sirt1 to suppress cell apoptosis and is required for mouse embryonic development. Mol Cell. 2012;46(4):484-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 211. Takata T, Ishikawa F. Human Sir2-related protein SIRT1 associates with the bHLH repressors HES1 and HEY2 and is involved in HES1- and HEY2-mediated transcriptional repression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301(1):250-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 212. Niwa H, Burdon T, Chambers I, Smith A. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 213. Ghosh HS, Spencer JV, Ng B, McBurney MW, Robbins PD. Sirt1 interacts with transducin-like enhancer of split-1 to inhibit NF-kappaB mediated transcription. Biochem J. 2007;408(1):105-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 214. Ghosh HS, McBurney M, Robbins PD. SIRT1 negatively regulates the mammalian target of rapamycin. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 215. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498-504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]