Abstract

Levels of plasma HDL are determined in part by catabolism in the liver. However, it is unclear how the hepatic catabolism of holo-HDL is regulated or mediated. Recently, we found that ob/ob mice have defective liver catabolism of HDL apoproteins in vivo that can be reversed by low-dose leptin treatment. Here we examined HDL catabolism and trafficking at the cellular level using isolated hepatocytes. We demonstrate that ob/ob hepatocytes have reduced binding, association, degradation, and resecretion of HDL apoproteins and 50% less selective lipid uptake relative to wild-type hepatocytes. In addition, HDL apoproteins were found to colocalize with transferrin in the general endosomal recycling compartment (ERC) in wild-type hepatocytes. However, the localization to the ERC was markedly reduced in ob/ob hepatocytes. Filipin staining of cellular cholesterol revealed decreased cholesterol in the ERC in ob/ob hepatocytes. Defects in HDL cell association and cholesterol distribution were reversed by leptin administration. The findings show a major defect in HDL uptake and recycling in ob/ob hepatocytes and suggest that HDL recycling through the ERC plays a role in the determination of plasma HDL protein and cholesterol levels.

Introduction

The liver is the principal organ for the catabolism of plasma HDL cholesterol and apoproteins (1). There is evidence in humans and mice that variations in plasma HDL apoprotein levels often reflect alterations in HDL apoprotein catabolism (2–4). The mechanism of LDL apoprotein and cholesterol uptake and trafficking have been largely elucidated (5, 6). In brief, LDL particles enter the cell by way of the LDL receptor, followed by dissociation of LDL from its receptor in the sorting endosome, resulting in the return of the LDL receptor to the plasma membrane. Subsequently, LDL cholesterol and apoprotein traffic to late endosomes and lysosomes, with the subsequent movement of LDL-derived cholesterol to the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum for esterification. The limited data on HDL apoprotein and cholesterol uptake indicates that the processes involved in HDL apoprotein and cholesterol uptake are dissimilar to LDL. HDL apoprotein and cholesterol may have different routes of entry into the cell, and fates within the cell are unknown (7). The recent discovery of an authentic HDL receptor, scavenger receptor B-I (SR-BI), has shed some light on this process. SR-BI has been shown to be the primary receptor for the selective uptake of HDL cholesteryl esters from HDL by the liver and steroidogenic tissues without accompanying uptake of HDL apoproteins (8, 9). Because SR-BI–deficient mice do not have defects in catabolism of HDL apoproteins (8, 9), but only HDL cholesteryl esters, it is possible that another receptor exists for the uptake of HDL apoproteins. A number of hepatic HDL-binding proteins have been identified (10). Although these proteins do indeed bind to HDL apoproteins with various affinities, none so far has been shown to mediate the uptake of HDL apoproteins by the liver. Therefore, it remains unclear how the hepatic catabolism of HDL apoproteins is mediated or regulated.

Recently, we have shown that 2 monogenic mouse models of obesity, ob/ob and db/db, have greatly increased plasma HDL cholesterol, apoAI, and apoAII levels, which was shown to be due to delayed hepatic catabolism of HDL apoproteins (11). In addition, this defect was significantly reversed by treatment of ob/ob mice with leptin, and treatment of lean wild-type mice with leptin also resulted in a decrease in plasma HDL cholesterol and apoprotein levels (11). Thus, leptin may play a physiological role in regulating plasma HDL cholesterol and apoprotein levels. Importantly, ob/ob mice do not have reduced hepatic SR-BI levels relative to wild-type mice. These studies suggested that ob/ob mice have a defect in a HDL particulate uptake pathway that is regulated by leptin. Because these studies were performed in vivo, the details of the hepatic catabolic defect at the cellular level in ob/ob mice remains to be determined. Here we extend these studies using a primary hepatocyte system and show that hepatocytes from ob/ob mice have decreased binding, uptake, and degradation of HDL apoproteins, as well as markedly decreased recycling of HDL apoproteins through the endosome recycling compartment.

Methods

Animals.

All mice used in these studies were 8-week-old female wild-type and ob/ob mice of the pure inbred strain C57BL/6J (purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). All mice were fed chow diet. For leptin treatment of ob/ob mice, a dose of 1 μg/g body weight of mouse recombinant leptin (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota) was injected intraperitoneally twice daily.

Lipoproteins.

Human HDL (1.063 < P < 1.21) and LDL (1.006 < P < 1.063) was isolated by buoyant density ultracentrifugation. HDL and LDL were iodinated using IODO-GEN according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Illinois, USA). Specific activities for the HDL and LDL were between 500 and 1000 cpm/ng. Human apoE-free HDL was labeled with 3H cholesteryl ether (31 cpm/ng HDL protein) and 14C-labeled free cholesterol (28 cpm/ng HDL protein) using cholesteryl ester transfer protein. The protein moieties of HDL and LDL were fluorescently labeled using Alexa-488, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oregon, USA). ApoE-free HDL was prepared by heparin Sepharose chromatography (Pierce).

Hepatocyte isolation.

Hepatocytes were isolated according to Honkakoski et al. (12), with the following modifications: Complete protease inhibitor was added to digestion buffer according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany).

Binding, association, and degradation assays.

To measure binding, radiolabeled or HDL or LDL was incubated in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 0.5% BSA, Williams’ medium E; GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, New York, USA) with freshly isolated hepatocytes in suspension in 6-well tissue culture plates for 1 hour at 4°C with slow shaking. After the 1-hour incubation period, cells were washed by centrifugation once with binding buffer, then 2 times with Williams’ medium E. Subsequently, cells were lysed, and radioactivity and protein concentration were measured. Association assays were performed in a manner similar to binding assays, except that incubations were done at 37°C. Degradation was determined using the following pulse-chase scheme: freshly isolated hepatocytes were pulsed for 1 hour at 37°C in suspension with radiolabeled lipoproteins. Cells were then cooled on ice and washed 3 times with binding buffer. Following the washes, cells were returned to 37°C and chased for 2 hours in binding buffer in the absence of radiolabeled lipoproteins. At the completion of the chase period, cell media was collected and TCA-soluble and precipitable counts were determined as a measurement of degradation and secretion, respectively. Cells were also lysed, and radioactivity and protein concentration were measured. To ensure that the pulse-chase scheme was measuring resecreted, nondegraded HDL, and not HDL released from the cell surface that was not washed off the cells after the pulse, 2 independent control experiments were performed to assess this method. In the first control ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes were pulsed for 1 hour at 37°C with 125I-labeled HDL, then washed 3 times with binding buffer, followed by protease treatment to remove surface-bound HDL (13). We found in 2 separate experiments performed in triplicate that there was a small decrease in 125I counts in cells after protease treatment compared with cells that did not receive protease treatment (wild-type, 26.7 ± 2.8 versus 30 ± 4.2; ob/ob, 13.6 ± 2.9 versus 14.3 ± 1.5 ng HDL [mg cell protein]–1h–1). In the second control experiment 2 groups of wild-type hepatocytes were pulsed with 125I-HDL for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed 3 times with binding buffer, then chased at either 37°C or 0°C for 2 hours in media without radiolabeled HDL. The amount of cell-released HDL during the 0°C chase represents HDL that remained bound to the cells during the washes and was not internalized; 29.5 ± 3.1 ng HDL (mg cell protein)–1h–1 remained in the cells chased at 0°C versus 14 ± 0.18 ng HDL (mg cell protein)–1h–1 chased at 37°C. Importantly, only 5.7 ± 0.67 ng HDL (mg cell protein)–1h–1 was found in the media after the 0°C chase with undetectable levels of degradation, whereas 17.5 ± 0.34 ng HDL (mg cell protein)–1h–1 was resecreted intact after the 37°C chase and 6.9 ± 0.4 ng HDL (mg cell protein)–1h–1 degraded. Thus, the pulse-chase scheme is measuring resecreted, intact HDL as well as degraded HDL. Bovine holotransferrin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was iodinated to a specific activity of 1700 cpm/ng and 5 μg/mL was incubated with hepatocytes according to the pulse-chase protocol outlined above. The transferrin pulse-chase assay was performed in triplicate.

HDL cholesterol–uptake assays.

Cholesteryl ether and free cholesterol uptake was measured during recycling using the pulse-chase scheme as described above. Triple-labeled HDL (125I, 3H cholesteryl ether and 14C free cholesterol) was used in these studies. 3H cholesteryl ether and 14C free cholesterol was measured from lipid extracted media and cells at the end of the chase.

Acute cholesterol depletion of hepatocytes.

Isolated hepatocytes were incubated with 20 mM 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma) for 30 minutes, washed to remove the cyclodextrin, and subsequently incubated with double-labeled HDL (125I and 3H cholesteryl ether) for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed 3 times, and cell-associated counts were measured. Lipid extraction showed that cell cholesterol was decreased by 45–50% after cyclodextrin treatment.

Filipin staining.

Freshly isolated hepatocytes were fixed and stained with filipin (Sigma) according to Mukherjee et al. (14).

Fluorescent confocal microscopy.

Cells were incubated with Alexa-labeled HDL or LDL in the same fashion as for association assays described above. Human holotransferrin (Sigma) was fluorescently labeled with Alexa 568 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Molecular Probes), and 5 μg/mL was incubated with hepatocytes. Cells were fixed in 3.7% formalin and examined using a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal laser scanning system (15 mW argon-krypton laser) attached to a Zeiss Axiovert 100TV inverted microscope with a ×100x objective. Optical sections were dual-scanned for both green (Alexa 488-HDL) and red (Alexa 568-transferrin) wavelength, followed by separation of both color channels using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, California, USA).

Statistical analysis.

Probability values were calculated for each experiment using Student’s t test.

Results

Characterization of HDL binding, uptake, and degradation in hepatocytes from ob/ob and wild-type mice.

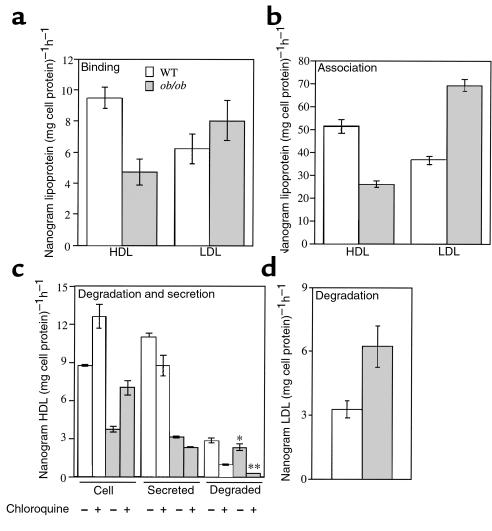

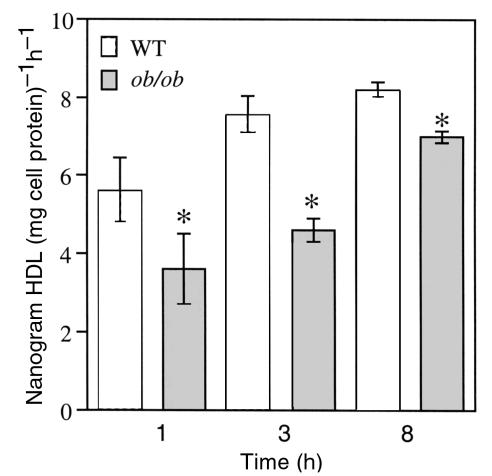

To characterize the defect in hepatic catabolism of HDL at the cellular level in ob/ob mice, we used freshly prepared primary hepatocytes from ob/ob and wild-type mice. The HDL catabolic defect in ob/ob mice may be the result of decreased binding of HDL to a cell-surface receptor resulting in decreased uptake and degradation. To test if binding of HDL to the hepatocyte cell surface is decreased in ob/ob mice, primary hepatocytes were isolated from both ob/ob and wild-type mice and incubated with 125I-labeled apoE-free HDL at 4°C. Figure 1a shows that specific binding of HDL to ob/ob hepatocytes was significantly reduced relative to wild-type hepatocytes. As a control, specific LDL binding at 4°C was assessed and found to be similar in ob/ob hepatocytes and wild-type hepatocytes. Next, specific HDL uptake was analyzed by incubating primary hepatocytes with 125I-labeled HDL at 37°C. Specific HDL cell association was reduced by 50% in ob/ob hepatocytes relative to wild-type (Figure 1b). Specific LDL uptake was found to be increased in ob/ob hepatocytes by 2-fold relative to wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 1b). Because ob/ob mice bind and internalize fewer HDL apoproteins than wild-type mice, it was of interest to determine whether the reduced amount of HDL that gets taken up by ob/ob hepatocytes is degraded to the same extent as in wild-type hepatocytes. A pulse-chase scheme was employed to measure HDL degradation and resecretion. Hepatocytes were pulsed with radiolabeled HDL, washed, and then chased in the absence of HDL. Very little of the cell-associated HDL at the end of the pulse was surface bound (see Methods), indicating that the HDL subsequently accumulating in media had been resecreted from cells. The amount of HDL residing in ob/ob hepatocytes and secreted by ob/ob hepatocytes at the end of the chase period was substantially reduced relative to wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 1c). The amount of HDL that was degraded was also significantly less in ob/ob hepatocytes relative to wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 1c). However, greater than 95% of HDL degradation in ob/ob hepatocytes was inhibited by chloroquine, an inhibitor of lysosomal function, compared with about 68% of the HDL degraded by wild-type hepatocytes. In addition, the amount of HDL that was resecreted by ob/ob hepatocytes was only 33% of that secreted by wild-type hepatocytes. Thus, although 50% less HDL is taken up by ob/ob hepatocytes, a greater fraction of internalized HDL is degraded by the lysosome, and a similar fraction (∼48%) is secreted out of the cell. Moreover, chloroquine treatment caused a modest accumulation of HDL within both ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes, which resulted in the expected reduced secretion of HDL from the cells. The amount of LDL degraded by ob/ob hepatocytes was found to be increased relative to wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 1d), consistent with an increased amount of LDL uptake by ob/ob hepatocytes (Figure 1b). HDL protein degradation was also compared in longer, steady-state incubations. The results seen in Figure 2 confirmed a significant, moderate decrease in HDL protein degradation in ob/ob hepatocytes at steady-state up to 8 hours. Together these data suggest that ob/ob hepatocytes have defects in binding, uptake, degradation, and recycling of HDL.

Figure 1.

Analysis of binding, association, and degradation of HDL and LDL with ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes. (a) Binding at 4°C for 1 hour of apoE-free human 125I-HDL or 125I-LDL with freshly isolated hepatocytes. (b) Association of apoE-free human 125I-HDL or 125I-LDL at 37°C for 1 hour with hepatocytes. (c) Degradation of apoE-free human 125I-HDL was determined by following a pulse-chase scheme (see Methods) in the presence or absence of 50 μM chloroquine. Degradation was calculated as the amount of TCA-soluble counts in the media at the end of the chase period (ob/ob versus WT, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0001). (d) Degradation of 125I-LDL was determined as in c. All experiments used 5 μg of HDL or LDL and were performed in triplicate a total of 3 times, with similar results. Results were reported as mean nanogram of HDL or LDL per milligram of cell protein per hour ± SD, after subtraction of background counts measured in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled HDL or LDL. WT, wild-type.

Figure 2.

Analysis of HDL degradation under steady-state conditions. Five micrograms apoE-free human 125I-HDL was incubated with hepatocytes at 37°C for the times indicated. Degraded HDL was determined from the amount of TCA-soluble counts in the media. Results were reported as mean nanogram HDL degraded per milligram of cell protein per hour ± SD, after subtraction of background counts measured in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled HDL (ob/ob versus WT, *P < 0.05). The data are representative of 2 independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Characterization of HDL cholesteryl ester and free cholesterol delivery to hepatocytes from ob/ob and wild-type mice.

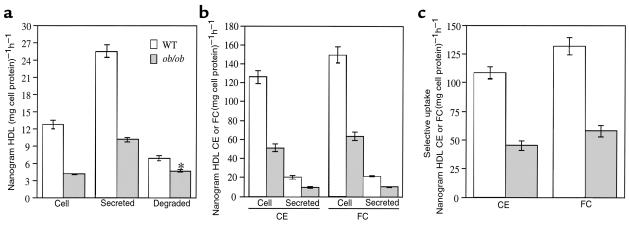

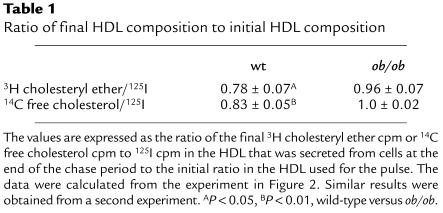

The major defect in HDL apoprotein metabolism in ob/ob hepatocytes is a defect in HDL apoprotein uptake associated with decreases in downstream events, especially recycling. This raises the question of whether a defect in HDL recycling could lead to increased plasma HDL cholesterol in ob/ob mice. To determine if the defect in HDL apoprotein recycling results in a decrease in HDL cholesterol uptake within the cell, we employed the same pulse-chase scheme as seen in Figure 1c using HDL radiolabeled on protein, cholesteryl ether, and free cholesterol. After the pulse period, cells were extensively washed so that the large majority of HDL protein was found only inside the cells (see Methods). Figure 3a shows the decreases in HDL apoprotein uptake and recycling in ob/ob hepatocytes similar to that seen in Figure 1c. This decrease in recycling was associated with an approximate 2.5-fold decrease in uptake of HDL cholesteryl ether and free cholesterol radioactivity by the cell (Figure 3b). In addition, the amount of secreted HDL cholesteryl ether and free cholesterol was half that of wild-type hepatocytes. Representing the data in terms of apparent selective uptake (see Methods), the ob/ob hepatocytes showed a greater than 50% reduction in selective uptake of both HDL cholesteryl ether and HDL free cholesterol (Figure 3c). If selective uptake of cholesterol occurs during the recycling process, then the HDL particles that recycled through the hepatocytes and were resecreted should be depleted of cholesterol tracers relative to protein tracer when compared with the initial HDL particle composition. As seen in Table 1, HDL particles that were resecreted by wild-type hepatocytes contained 22% less 3H cholesteryl ether and 17% less 14C free cholesterol tracer than the initial HDL particle used during the pulse period, whereas the HDL particles resecreted by ob/ob hepatocytes contained only 4% less 3H cholesteryl ether and similar amounts of 14C free cholesterol tracer relative to the initial HDL particle.

Figure 3.

Analysis of HDL cholesteryl ether and free cholesterol uptake during HDL recycling. Triple-labeled apoE-free human HDL (3H cholesteryl ether, 14C free cholesterol, 125I) was incubated with both ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes according to the pulse-chase scheme used in Figure 1c. (a) Shown is the HDL protein concentrations that remained inside the cells, or was secreted intact, or degraded at the end of the chase period (ob/ob versus WT, *P < 0.001). (b) The amount of cholesteryl ether and free cholesterol per nanogram of HDL protein that remained inside the cells or was secreted at the end of the chase period is shown. (c) Apparent selective uptake was measured by subtracting the amount of HDL cholesteryl ether (3H) or free cholesterol (14C) from the amount of HDL protein (125I) that remained inside the cells at the end of the chase period. Results were reported as specific internalization (cell), degradation, and secretion by subtracting the counts remaining after incubations with 100-fold excess unlabeled HDL. All experiments were performed twice, in triplicate, with similar results.

Table 1.

Ratio of final HDL composition to initial HDL composition

Subcellular localization of HDL apoproteins in ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes.

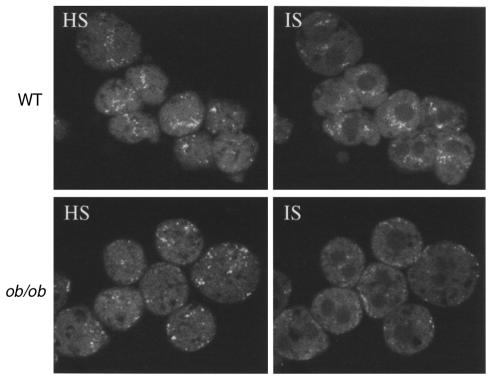

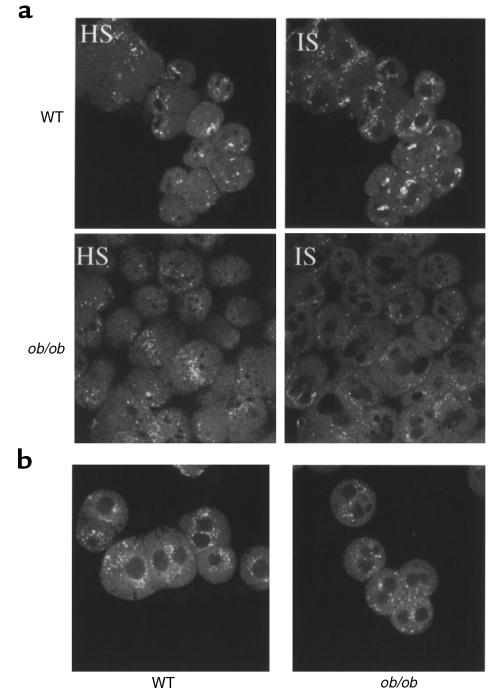

Based on the findings that ob/ob hepatocytes have defective HDL apoprotein binding, uptake, degradation, and recycling, it was of interest to determine whether these defects are correlated with changes in HDL apoprotein subcellular localization within the hepatocyte. To examine HDL apoprotein localization within the hepatocyte, HDL with a fluorescently labeled apoprotein component was injected intravenously into ob/ob and wild-type mice, followed by isolation of hepatocytes and examination of apoprotein localization using confocal microscopy. Both ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes have a similar pattern of HDL apoproteins at the cell surface as shown by a high optical section (HS; Figure 4). However, the intensity of the fluorescent signal within the ob/ob hepatocyte was found to be different compared with wild-type mice (internal optical section; IS). HDL apoproteins were primarily seen in a juxtanuclear region, whereas in ob/ob hepatocytes few juxtanuclear localized signals were detected. Next, it was important to confirm that the localization pattern in wild-type and ob/ob hepatocytes could be recapitulated in vitro under the same conditions used previously (Figures 1–3). Therefore, hepatocytes were first isolated from ob/ob and wild-type animals and then incubated with fluorescently labeled HDL. The localization patterns for HDL apoproteins in vitro for both ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 5a) were found to be similar to those in the in vivo pattern (Figure 4). The ob/ob hepatocytes again showed a reduced internal signal relative to wild-type hepatocytes. As a control, fluorescently labeled LDL was incubated in vitro with isolated hepatocytes. The pattern of LDL apoprotein localization was found to be similar in ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 5b).

Figure 4.

In vivo localization of HDL apoproteins in ob/ob hepatocytes. Apoproteins on human apoE-free HDL were labeled with the green fluorescent tracer Alexa-488 and injected intravenously into ob/ob and wild-type mice. After 1 hour, hepatocytes were isolated, fixed in 3.7% formalin, and optical sections were imaged using a confocal microscope. Apoproteins were seen to be localized in a juxtanuclear compartment in wild-type cells, which was reduced in ob/ob cells. HS, high optical section; IS, internal optical section.

Figure 5.

In vitro localization of HDL apoproteins in ob/ob hepatocytes. Primary hepatocytes from ob/ob and wild-type mice were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with human apoE-free HDL labeled with Alexa-488. After 1 hour, hepatocytes were washed and fixed in 3.7% formalin, and optical sections were imaged using a confocal microscope. HS, high optical section; IS, internal optical section.

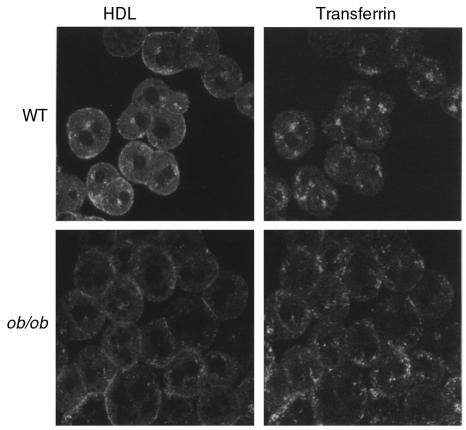

Biochemical data (Figure 1) shows that ob/ob hepatocytes have greatly reduced binding, uptake, and recycling of intact HDL. Because proteins known to recycle within cells pass through what is known as the general endosomal recycling compartment (ERC) located in a juxtanuclear region (6), the reduction of HDL apoprotein recycling in ob/ob hepatocytes should be correlated with a reduction in the amount of HDL apoprotein entering the recycling compartment. To determine if the juxtanuclear compartment seen in wild-type hepatocytes is the ERC and if less HDL apoproteins enter this compartment in ob/ob hepatocytes, the subcellular localization of transferrin, a well-established marker of the ERC (6), was examined. Co-incubation of fluorescently labeled HDL and transferrin using 2 different-colored fluorescent probes (see Methods) with wild-type hepatocytes showed that both HDL and transferrin colocalized to the juxtanuclear compartment, thus identifying it as the ERC (Figure 6). In contrast, few HDL apoprotein signals were seen in the ERC in ob/ob hepatocytes (Figure 6). Together with the biochemical data (Figure 1c and Figure 3a), these data indicate that less HDL apoprotein is trafficking through the ERC in ob/ob hepatocytes. Although the pattern of transferrin localization appeared slightly different in ob/ob and wild-type cells, both types of hepatocytes recycled similar amounts of transferrin (ob/ob, 5.3 ± 0.6 versus wild-type, 5.3 ± 0.8 ng transferrin [mg cell protein]–1h–1), indicating that ob/ob cells do not have a general defect in ERC function.

Figure 6.

Localization of HDL and transferrin in wild-type and ob/ob hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were coincubated with Alexa-labeled human apoE-free HDL and Alexa-labeled human holotransferrin at 37°C for 1 hour. Hepatocytes were then washed and fixed in 3.7% formalin and examined using a confocal microscope. Dual scanning for both green (Alexa 488) and red (Alexa 568) fluorophores was performed on the same sections, followed by computer separation of both color channels. This experiment was repeated on hepatocytes from 3 separate animals of each genotype yielding similar results.

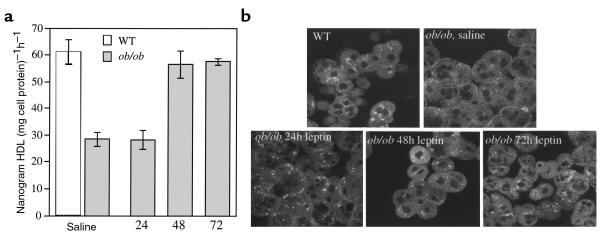

Reversal of the defect in HDL uptake and localization in ob/ob hepatocytes by leptin.

Previously we showed that low-dose intraperitoneal injection of leptin into ob/ob mice significantly reduced plasma HDL cholesterol levels. Therefore, we tested whether leptin could reverse the low level of HDL uptake by isolated ob/ob hepatocytes and reverse the altered pattern of HDL apoprotein localization. Here, ob/ob mice were injected with either leptin or saline for 24, 48, and 72 hours, and hepatocytes were isolated. Isolated hepatocytes were then incubated with 125I-labeled HDL, and uptake was measured. Figure 7a shows that HDL apoprotein uptake by ob/ob hepatocytes was significantly increased to near wild-type levels after 48 hours of leptin treatment. As an independent test to confirm that leptin reversed the defect in HDL uptake, the same ob/ob hepatocytes used to biochemically measure HDL apoprotein uptake (Figure 7a) were examined under confocal microscopy using Alexa-HDL. Indeed, after 48 and 72 hours of leptin treatment, there was an increase in HDL apoproteins seen in a juxtanuclear location similar to that seen for wild-type hepatocytes (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Leptin restores the defect in HDL uptake by ob/ob primary hepatocytes and the altered localization pattern of HDL apoproteins in primary ob/ob hepatocytes. (a) ob/ob mice were injected twice daily with 1 μg/g body weight leptin for the times indicated. Control ob/ob mice (0 hour time point) were injected twice daily with saline and pair-fed to the leptin-treated mice. After treatments, hepatocytes were isolated and incubated with either apoE-free human 125I-HDL or Alexa-HDL (see Figure 6) at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed, and total cell radioactivity was counted. All experiments used 5 μg of HDL and were performed a total of 2–3 times in triplicate with similar results. Results were reported as mean nanogram of HDL per milligram of cell protein per hour ± SD, after subtraction of background counts measured in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled HDL (*0 and 24 hours versus 48 and 72 hours; P < 0.005). (b) Primary hepatocytes from a were incubated with Alexa-HDL at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were then washed, fixed, and examined using confocal microscopy. Apoproteins in hepatocytes from leptin-treated ob/ob mice were localized in a similar pattern as seen in wild-type mice, i.e., juxtanuclear location. All experiments used 5 μg of HDL and were performed a total of 3 times with similar results.

Cholesterol distribution within ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes.

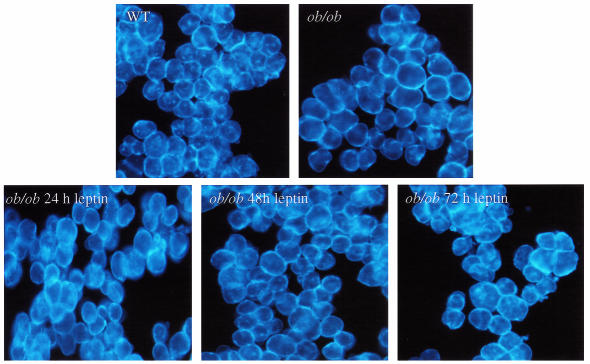

Because ob/ob hepatocytes showed a marked reduction in HDL cholesterol delivery during recycling relative to wild-type hepatocytes, it was possible that these defects were associated with an altered distribution of cholesterol within the hepatocyte. To examine this possibility both ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes were stained with the fluorescent cholesterol-sequestering drug filipin. Figure 8 shows that cholesterol in wild-type hepatocytes was found in both the plasma membrane and in perinuclear compartments (as similarly shown by others) and described as the ERC (14, 15). However, in ob/ob hepatocytes the distribution was dramatically different, with cholesterol staining primarily in the plasma membrane and no or faint intracellular signals.

Figure 8.

Cellular cholesterol distribution in ob/ob hepatocytes and effect of leptin. Hepatocytes were fixed and then stained with filipin (50 μg/mL), then viewed using fluorescent microscopy. Filipin staining was carried out on hepatocytes isolated from 3 ob/ob and 3 wild-type mice not treated with leptin, yielding a similar staining pattern as shown. One group of mice was treated with leptin according to Figure 7. Hepatocytes were fixed and stained with filipin. A total of 2 ob/ob mice were used for each time point giving similar staining patterns, as shown.

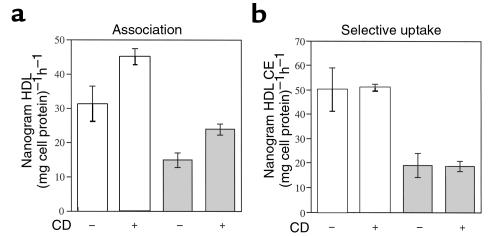

To examine whether decreased HDL uptake might be secondary to the apparent increase in plasma membrane cholesterol, hepatocytes from both ob/ob and wild-type mice were acutely depleted of cholesterol (∼45–50%) using 2-hydroxypropyl-βcyclodextrin, an effective extracellular cholesterol acceptor, and HDL association was measured. Figure 9a shows that acute cholesterol depletion resulted in a modest increase in cell association, but did not increase selective uptake (Figure 9b). The defect in both HDL association and selective uptake in ob/ob hepatocytes was still apparent after cholesterol depletion.

Figure 9.

Acute cholesterol depletion of ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes. Hepatocytes were pretreated with 20 mM 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin for 30 minutes, washed, then incubated with 5 μg/mL of 125I and 3H cholesteryl ether–labeled apoE-free HDL at 37°C for 1 hour. (a) HDL protein association (125I). (b) Apparent selective uptake was measured by subtracting the amount of HDL cholesteryl ether (3H) from the amount of HDL protein (125I) that remained cell associated. This experiment was performed a total of 2 times, in triplicate, with similar results. Results were reported as mean nanogram HDL or HDL cholesteryl ether per milligram cell protein per hour ± SD, after subtraction of background counts measured in the presence of 100-fold excess unlabeled HDL.

Based on the results that leptin reversed the defect in HDL uptake in ob/ob hepatocytes (Figure 7), we next examined whether leptin might also revert the altered cholesterol distribution pattern in ob/ob hepatocytes to a pattern more similar to a wild-type pattern. Here, ob/ob mice were injected with leptin as represented in Figure 8. Hepatocytes were isolated and stained with filipin. Figure 8 shows that after 48 hours and 72 hours of leptin treatment perinuclear filipin fluorescence appeared within many ob/ob cells, suggesting reversion to the wild-type pattern.

Discussion

In this study we used freshly isolated primary mouse hepatocytes to document the cellular defects leading to high levels of plasma HDL protein and cholesterol in ob/ob mice (11). Specifically, this study has demonstrated that ob/ob hepatocytes have defects in HDL binding, cell association, degradation, and recycling of HDL apoproteins. Because the percentage of HDL recycling through the ob/ob hepatocyte was similar to wild-type, the primary defect in ob/ob hepatocytes may be reduced HDL particle uptake that then results in reductions of all downstream events in HDL trafficking (e.g., recycling and degradation). These changes were associated with decreased HDL cholesteryl ester selective uptake during recycling, even though SR-BI levels were similar to wild-type levels (11). These studies document extensive HDL recycling through the ERC and suggest that when recycling is reduced, increased HDL levels result. It is interesting that ob/ob hepatocytes appear to have a global alteration in cholesterol distribution, with a notable paucity of cholesterol in intracellular sites. These changes could, in part, reflect a failure of HDL to deliver cholesterol to the ERC.

Taking the data together, the defects in HDL cholesterol uptake and protein degradation probably explain the high plasma HDL cholesterol and protein levels found in ob/ob mice. Because the decrease in HDL protein degradation in ob/ob hepatocytes relative to wild-type hepatocytes was moderate, other in vivo factors, such as HDL pool size and HDL particle composition and size, may also contribute to the marked increase in HDL protein and cholesterol in ob/ob mice. The defect in total and selective uptake of HDL cholesteryl ester was marked (Figure 3, b and c, and Figure 9) and could account for the 2- to 3-fold elevation in plasma HDL cholesterol levels in ob/ob mice. In wild-type mice, during repeated rounds of recycling, HDL cholesterol may be progressively removed, resulting in a smaller particle. A decrease in this process, as found in ob/ob hepatocytes, might result in larger, cholesterol-enriched particles with secondary increases in apoAI and apoAII protein levels (11). Indeed, it has been shown that large HDL and apoAII-enriched HDL are catabolized more slowly than smaller HDL (2, 16, 17). Therefore, the defect in recycling in ob/ob hepatocytes may have a cumulative effect on HDL protein catabolism in vivo.

The major defect in ob/ob cells was a decrease in uptake of HDL protein and cholesterol. Because the initial step (binding) in HDL-particle uptake was defective in ob/ob hepatocytes, it is likely that the observed reductions in degradation and recycling are simply the result of a decrease in the amount of HDL being taken up. This idea is supported by the finding that the percentage of HDL that is recycled through both wild-type and ob/ob hepatocytes was similar. In wild-type cells HDL recycling was extensive and HDL colocalized with transferrin, suggesting that HDL passes through the ERC. Our data have confirmed the findings from others that the majority of HDL apoprotein that enters hepatocytes recycles back outside of the cell in what has been termed “retroendocytosis” (18–20). These initial descriptions of HDL recycling were extended here by showing that a reduction in HDL recycling is associated with marked elevation in plasma HDL levels. Moreover, we showed that selective uptake can occur during the process of HDL recycling. The decrease in HDL recycling may therefore contribute to defective selective uptake and increased HDL cholesterol in ob/ob mice. Together, these observations suggest that recycling plays a role in regulating HDL levels.

The finding of defective HDL uptake and reduced recycling was supported by the marked reduction in the subcellular localization signal of HDL apoproteins observed in ob/ob hepatocytes as shown by confocal microscopy. The decrease in the HDL apoprotein signal also appeared to be associated with an alteration in localization pattern. The simplest interpretation of the confocal data is that the overall amount of HDL apoprotein taken up by the ob/ob hepatocyte is reduced, resulting in the appearance of reduced juxtanuclear signals. The juxtanuclear compartment that was shown to contain HDL and LDL in wild-type hepatocytes may be composed of lysosomes intermixed with the ERC (21). Our confocal microscopy data using transferrin as a marker for the ERC (6) indicated that the juxtanuclear compartment containing HDL is the ERC, and that fewer HDL apoproteins traffic to this compartment in ob/ob hepatocytes, and therefore less HDL may recycle.

The degradation of HDL apoproteins in ob/ob hepatocytes was found to be significantly reduced compared with wild-type hepatocytes. The decrease in HDL degradation in ob/ob hepatocytes is not because of a general defect in lysosome function because the uptake and degradation of LDL apoprotein, which becomes degraded within lysosomes (6), was actually enhanced in ob/ob hepatocytes relative to wild-type hepatocytes. In addition, the pattern of LDL subcellular localization was similar in ob/ob and wild-type hepatocytes. Rather, the defect in ob/ob hepatocytes appeared to reflect reduced degradation by a nonlysosomal pathway. Chloroquine did not completely abolish degradation in wild-type hepatocytes, suggesting a nonlysosomal pathway for degradation of HDL. Similarly, Duan et al. have shown that apoE can be partially degraded by a nonlysosomal pathway in macrophages (22), possibly involving proteasomes (23). However, chloroquine nearly abolished HDL degradation by the ob/ob hepatocyte, indicating that the majority of HDL that is degraded in the ob/ob hepatocyte terminates in the lysosome. Thus, the decrease in HDL degradation in ob/ob hepatocytes appears to be due to decreased degradation by a nonlysosomal pathway.

It is intriguing that although ob/ob and wild-type mice have similar SR-BI levels, ob/ob mice showed a marked reduction in selective uptake of cholesteryl ester, a process known to be mediated by SR-BI (7). Our data imply that either SR-BI function is altered or that another molecule mediates selective uptake during HDL-particle recycling. It is also possible that SR-BI itself traffics along with HDL particles during particle recycling, thereby mediating selective cholesterol uptake in endosomes.

Despite similar liver cholesterol levels in ob/ob and wild-type mice (ref. 24; D.L. Silver and A.R. Tall, unpublished results), there was a striking defect in cholesterol distribution in ob/ob hepatocytes. The majority of cellular cholesterol as determined by filipin staining in ob/ob hepatocytes appeared to be localized to the plasma membrane and not distributed in plasma membrane and endosomal compartments as seen in wild-type cells. The cholesterol-rich juxtanuclear compartment has been identified as the ERC (14, 15). The origin of the cholesterol in the ERC is unknown. LDL-derived cholesterol does not seem to be a contributor because evidence indicates that LDL-derived cholesterol traffics from the lysosome to the plasma membrane and then enters the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) for esterification (25). The contribution of de novo synthesized cholesterol to the ERC cholesterol pool remains to be determined. However, some data suggest that after its synthesis in the ER, the majority of cholesterol arrives in the plasma membrane as determined by susceptibility to extraction by cyclodextrin (25). Some de novo synthesized cholesterol may pass through the ERC on its way to the plasma membrane. Because we found that HDL recycles through the ERC, it is tempting to speculate that HDL plays a role in delivering cholesterol to the recycling compartment and that reduced recycling of HDL in ob/ob hepatocytes contributes to a paucity of cholesterol in the ERC. In support of this idea we showed that leptin treatment coordinately reversed the altered cholesterol distribution and defective HDL apoprotein uptake in ob/ob hepatocytes.

Theoretically, the altered cholesterol distribution in ob/ob hepatocytes could be the cause or consequence of defective HDL uptake. There is precedent for such a mechanism. Experimentally altered plasma membrane and endosomal membrane cholesterol levels have been shown to affect the trafficking of proteins such as GPI-anchored proteins, transferrin receptor, and signal transduction pathways (15, 26, 27). However, acute cholesterol depletion of the plasma membrane of ob/ob hepatocytes did not reverse the defect in selective uptake and resulted in only minor increases in HDL cell association also found in cholesterol-depleted wild-type cells. Therefore, it is more likely that the altered cholesterol distribution in ob/ob hepatocytes is the result of defective HDL uptake rather than its cause. However, it was shown recently that cholesterol biosynthesis in livers of ob/ob mice was 6-fold less per gram of tissue compared with wild-type mice (28). Thus, reduced cholesterol biosynthesis could also contribute to the altered cholesterol distribution.

In summary, our further characterization of HDL catabolism by ob/ob mice has revealed novel aspects of hepatic HDL apoprotein catabolism; namely, we appear to have shown for the first time the existence of a hepatic HDL-particle pathway that involves HDL apoprotein trafficking to the ERC, with selective uptake of cholesterol followed by recycling of HDL particles out of the cell. The activity of this pathway was shown to be reduced, suggesting downregulation of a cell-surface receptor regulated in part by leptin in ob/ob mice. The identification of the molecular components of this pathway may lead to a better understanding of the regulation of plasma HDL homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank I. Tabas for many helpful suggestions and discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL-22682 (to A.R. Tall) and National Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Award HL-09928-01 (to D.L. Silver).

References

- 1.Glass CK, Pittman RC, Keller GA, Steinberg D. Tissue sites of degradation of apoprotein A-I in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:7161–7167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinton EA, Eisenberg S, Breslow JL. Human HDL cholesterol levels are determined by apoA-I fractional catabolic rate, which correlates inversely with estimates of HDL particle size. Effects of gender, hepatic and lipoprotein lipases, triglyceride and insulin levels, and body fat distribution. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:707–720. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fidge N, Nestel P, Ishikawa T, Reardon M, Billington T. Turnover of apoproteins A-I and A-II of high density lipoprotein and the relationship to other lipoproteins in normal and hyperlipidemic individuals. Metabolism. 1980;29:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrabian M, et al. Influence of the apoA-II gene locus on HDL levels and fatty streak development in mice [erratum 1993, 13:466] Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1–10. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Lipoprotein receptors and the control of plasma LDL cholesterol levels. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(Suppl. B):34–36. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/13.suppl_b.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherjee S, Ghosh RN, Maxfield FR. Endocytosis. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:759–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rigotti A, et al. Scavenger receptor BI: a cell surface receptor for high density lipoprotein. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1997;8:181–188. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigotti A, et al. A targeted mutation in the murine gene encoding the high density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor scavenger receptor class B type I reveals its key role in HDL metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12610–12615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varban ML, et al. Targeted mutation reveals a central role for SR-BI in hepatic selective uptake of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4619–4624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fidge NH. High density lipoprotein receptors, binding proteins, and ligands. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:187–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver DL, Jiang XC, Tall AR. Increased high density lipoprotein (HDL), defective hepatic catabolism of ApoA-I and ApoA-II, and decreased ApoA-I mRNA in ob/ob mice. Possible role of leptin in stimulation of HDL turnover. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4140–4146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honkakoski P, Negishi M. Protein serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitors suppress phenobarbital-induced Cyp2b10 gene transcription in mouse primary hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1998;330:889–895. doi: 10.1042/bj3300889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammad SM, et al. Cubilin, the endocytic receptor for intrinsic factor-vitamin B(12) complex, mediates high-density lipoprotein holoparticle endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee S, Zha X, Tabas I, Maxfield FR. Cholesterol distribution in living cells: fluorescence imaging using dehydroergosterol as a fluorescent cholesterol analog. Biophys J. 1998;75:1915–1925. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77632-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subtil A, et al. Acute cholesterol depletion inhibits clathrin-coated pit budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6775–6780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weng W, et al. ApoA-II maintains HDL levels in part by inhibition of hepatic lipase. Studies in apoA-II and hepatic lipase double knockout mice. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1064–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen JC, Vega GL, Grundy SM. Hepatic lipase: new insights from genetic and metabolic studies. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:259–267. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLamatre JG, Sarphie TG, Archibold RC, Hornick CA. Metabolism of apoE-free high density lipoproteins in rat hepatoma cells: evidence for a retroendocytic pathway. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:191–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takata, K., Horiuchi, S. , Rahim, A.T., and Morino, Y. 1988. Receptor-mediated internalization of high density lipoprotein by rat sinusoidal liver cells: identification of a nonlysosomal endocytic pathway by fluorescence-labeled ligand. J. Lipid Res. 29:1117–1126. [PubMed]

- 20.Kambouris AM, Roach PD, Calvert GD, Nestel PJ. Retroendocytosis of high density lipoproteins by the human hepatoma cell line, HepG2. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:582–590. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemery I, Durand-Schneider AM, Feldmann G, Vaerman JP, Maurice M. The transcytotic pathway of an apical plasma membrane protein (B10) in hepatocytes is similar to that of IgA and occurs via a tubular pericentriolar compartment. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1215–1227. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan H, Lin CY, Mazzone T. Degradation of macrophage ApoE in a nonlysosomal compartment. Regulation by sterols. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31156–31162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivett AJ. The multicatalytic proteinase. Multiple proteolytic activities. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12215–12219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feingold KR, Lear SR, Moser AH. De novo cholesterol synthesis in three different animal models of diabetes. Diabetologia. 1984;26:234–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00252414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neufeld EB, et al. Intracellular trafficking of cholesterol monitored with a cyclodextrin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21604–21613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayor S, Sabharanjak S, Maxfield FR. Cholesterol-dependent retention of GPI-anchored proteins in endosomes. EMBO J. 1998;17:4626–4638. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodal SK, et al. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:961–974. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimomura I, Bashmakov Y, Horton JD. Increased levels of nuclear SREBP-1c associated with fatty livers in two mouse models of diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30028–30032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]