Summary

Helicobacter pyloriis a bacterial pathogen that colonizes the gastric niche of ~50% of the human population worldwide and is known to cause peptic ulceration and gastric cancer. Pathology of infection strongly depends on a cag pathogenicity island (cagPAI)-encoded type IV secretion system (T4SS). Here, we aimed to identify as yet unknown bacterial factors involved in cagPAI effector function and performed a large-scale screen of an H. pylori transposon mutant library using activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB in human gastric epithelial cells as a measure of T4SS function. Analysis of ~3000 H. pylori mutants revealed three non-cagPAI genes that affected NF-κB nuclear translocation. Of these, the outer membrane protein HopQ from H. pylori strain P12 was essential for CagA translocation and for CagA-mediated host cell responses such as formation of the hummingbird phenotype and cell scattering. Besides that, deletion of hopQ reduced T4SS-dependent activation of NF-κB, induction of MAPK signalling and secretion of interleukin 8 (IL-8) in the host cells, but did not affect motility or the quantity of bacteria attached to host cells. Hence, we identified HopQ as a non-cagPAI-encoded co-factor of T4SS function.

Keywords: CagA, NF-κB, Omp27, adhesin, type IV secretion system

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic, spiral-shaped gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of ~50% of the human population worldwide. Chronic infection always leads to gastritis and can also result in more serious gastric diseases, such as peptic ulceration, gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT) (Nomura et al., 1991, Cover and Blaser, 1992, Walker and Crabtree, 1998, Peek et al., 2002, Farinha and Gascoyne, 2005, Peek et al., 2006).

H. pylori produces numerous virulence factors (Gressmann et al., 2005) that enable bacteria to adapt and multiply within the hostile environment of the human gastrointestinal tract (Blaser and Atherton, 2004, Bauer and Meyer, 2011). Amongst the known virulence determinants, the type IV secretion system (T4SS) stands out since its presence in the bacterial genome strongly correlates with serious H. pylori-induced pathologies (Ogura et al., 2000, Huang et al., 2003, Blaser and Atherton, 2004). The T4SS is encoded by a 40 kb pathogenicity island (cagPAI), which comprises 31 genes (Censini et al., 1996, Tomb et al., 1997) and was probably acquired by horizontal gene transfer. The T4SS serves to translocate the CagA effector protein from bacteria into gastric epithelial cells (Backert et al., 2000, Odenbreit et al., 2000, Stein et al., 2000), and provokes host cell responses, such as altered cell motility and signal transduction (Churin et al., 2001, Higashi et al., 2002, Mimuro et al., 2002, Churin et al., 2003, Tsutsumi et al., 2003, Suzuki et al., 2005). More recently, CagA has been implicated in the suppression of innate host cell responses (Bauer et al., 2012) and in the cause of an advanced invasive phenotype by disrupting cell-cell adhesion and perturbing epithelial cell differentiation (Bagnoli et al., 2005). Also the T4SS itself induces host cell responses in gastric epithelial cells such as the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB (Glocker et al., 1998). Together with the transcription factor AP-1 (activator protein 1), NF-κB regulates the expression of interleukin 8 (IL-8) (Aihara et al., 1997, Sharma et al., 1998) and is involved in cellular apoptotic, proliferative and immune responses (Hoffmann and Baltimore, 2006).

The H. pylori genome encodes numerous outer membrane protein (OMP) encoding genes. Most OMPs can be assigned to two protein families: Helicobacter OMPs (Hop) and Hop-related proteins (Hor) (Alm et al., 2000). Hops are reminiscent of autotransporter proteins (Jose et al., 1995), many of which are crucial adhesins and subject to phase variation and/or recombination (Alm and Trust, 1999, Odenbreit et al., 1999, Talarico et al., 2012, Hauck and Meyer, 2003). The Hop family adhesins include the H. pylori blood group antigen binding adhesin (BabA) (Ilver et al., 1998); the sialic acid-binding adhesin SabA (Aspholm et al., 2006, Lu et al., 2007); the adherence-associated lipoproteins A and B (AlpA and AlpB; (Odenbreit et al., 1999) and the HopZ protein (Peck et al., 1999, Kennemann et al., 2011). Moreover, HopQ was shown to influence adherence of a subset of H. pylori strains to human epithelial cells (Loh et al., 2008). Another, related H. pylori outer membrane protein is reportedly involved in inducing IL-8 secretion in host cells (Yamaoka et al., 2000, Yamaoka et al., 2002a) while studies by Odenbreit et al. (2002) failed to show correlations between CagA translocation, IL-8 induction and the expression of nine different OMPs. Another five members of the Hop family, named HopA through to HopE, have been speculated to function as porins (Doig et al., 1995, Exner et al., 1995). Therefore, the exact contribution of Hops to the modulation of host cell responses and pathogenesis remain fragmentary and contradictory in part.

To identify novel H. pylori factors that are required for cagPAI-mediated pathogenesis, we screened an H. pylori transposon mutant library (Salama et al., 2004) for mutants affecting a T4SS-dependent host epithelial cell response; namely, activation of the transcription factor NF-κB (Fischer et al., 2001, Maeda et al., 2001, Bauer et al., 2005, Bartfeld et al., 2010). From a total of 59 hits influencing T4SS-dependent NF-κB activation in H. pylori-infected cells, we identified HopQ as an important accessory factor. Our analysis also revealed a function of HopQ for other T4SS-dependent host cell responses in addition to NF-κB activation.

Results

High throughput quantitative assay for H. pylori mutant analysis

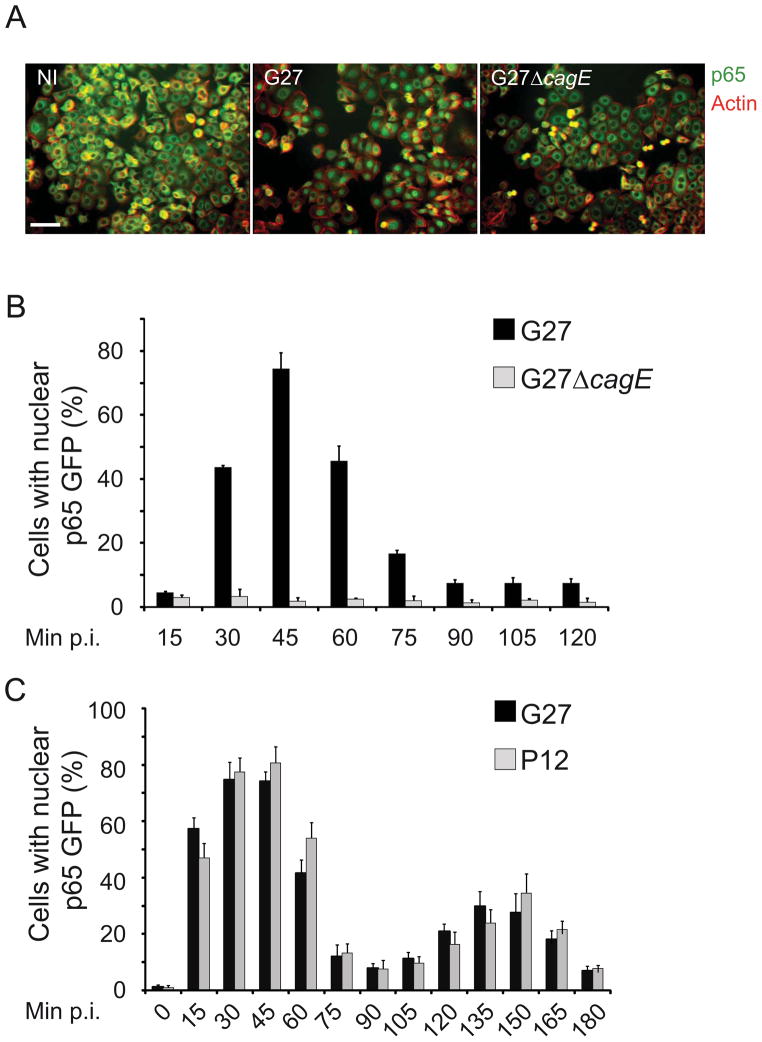

To identify novel bacterial factors involved in the induction of T4SS-mediated host cell responses, we screened an H. pylori transposon-based mutant library for mutants defective in activating the eukaryotic transcription factor NF-κB. The H. pylori type I strain G27 (cagPAI- positive), the strain from which the mutant library was derived (Salama et al., 2004), stimulated NF-κB nuclear translocation in human AGS gastric epithelial cells upon infection, as determined by immunofluorescent staining of the NF-κB subunit p65 (Fig. 1A). Similarly, G27 infection stimulated NF-κB activation in recombinant AGS-SIB02 cells – a cell line in which p65-GFP nuclear translocation can be analyzed as a high-throughput-compatible quantitative read-out (Bartfeld et al., 2009). NF-κB activation by G27 peaked at 45 min post infection (p.i.), whereas a T4SS-defective congenic G27ΔcagE strain failed to activate NF-κB (Fig. 1B). Moreover, infection of AGS-SIB02 cells with the H. pylori strain P12 (cagPAI-positive) led to the induction of an oscillating activation phenotype exhibiting two peaks (45 and 150 min p.i.), very similar to the pattern induced by infection with G27 (Fig. 1C). These studies confirmed the T4SS- dependent activation of NF-κB by H. pylori G27 and validated our read-out system for high- throughput investigations. The assay was adapted to a semi-automated screening protocol, to facilitate the analysis of ~3000 Tn7 transposon mutants using wild type G27 and the library- derived mutant G27ΔvacA as NF-κB-activating controls and the G27ΔcagE mutant as a negative control (Fig. S1A and S1B).

Figure 1. H. pylori type I strains induce nuclear translocation of p65.

A) Immunofluorescence staining of infected (G27) and non-infected (NI) AGS cells. AGS cells were infected for 45min at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100, fixed and stained with an anti-p65 antibody (green) and phalloidin (actin, red). Samples were analyzed with epifluorescence microscopy. Scale bar represents 50μm. (B, C) Bar diagrams showing percentage of activated cells in two time course experiments between 0–120min p.i.(B) and 0–180 min p.i. (C). AGS SIB02 cells were infected with G27, the T4SS deficient mutant G27ΔcagE or P12 (MOI 100). After fixation p65 translocation was quantified by using an automated microscope and subsequent computational analysis (ScanR; Olympus). Error bars indicate mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

H. pylori mutations affecting NF-κB activation map both within and distal to the cagPAI

A total of 579 candidate mutants passed initial statistical analyses, determined using a modified R-script (see Experimental Procedures; Fig. S2, S3), and these mutants were validated in two further screening rounds (Fig. S1A), to yield 59 high-confidence hits in genes that exhibited decreased T4SS-dependent p65 translocation upon transposon mutagenesis. All 59 transposon mutants were sequenced using transposon-specific primers with the aim of identifying the loci of transposon insertions within the H. pylori G27 genome. The vast majority (56) of hits carried the insertion in 16 different cagPAI genes, underscoring the strong T4SS dependency of NF-κB activation in AGS epithelial cells (Table I). Infection with all cagPAI mutants led to reduced nuclear translocation of p65 at all time points investigated (Fig. 2A).

Table 1.

Identified cagPAI mutants

| Number of identified mutants | Gene in G27 | Ortholog (Hp 266952) | Ortholog (Hp P12) | cag nomenclature | tn-number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | HPG27_486 | HP0527 | HPP12_0534 | CagY | 1, 3, 4, 10, 11, 14, 19, 28, 34, 41, 44, 49, 52, 26 |

| 2 | HPG27_484 | HP0525 | HPP12_0532 | VirB11 | 2, 58 |

| 6 | HPG27_489 | HP0530 | HPP12_0537 | CagV | 5, 17, 47, 55, 59, 20 |

| 3 | HPG27_490 | HP0531 | HPP12_0538 | CagU | 6, 9, 30 |

| 7 | HPG27_503 | HP0544 | HPP12_0551 | CagE | 7, 13, 23, 39, 40, 53, 25 |

| 3 | HPG27_501 | HP0542 | HPP12_0549 | CagG | 12, 15, 29 |

| 3 | HPG27_481 | HP0522 | HPP12_0529 | Cag3 | 16, 36, 45 |

| 6 | HPG27_487 | HP0528 | HPP12_0535 | CagX | 18, 24, 38, 51, 56, 31 |

| 1 | HPG27_491 | HP0532 | HPP12_0539 | CagT | 21 |

| 1 | HPG27_504 | HP0545 | HPP12_0552 | CagD | 27 |

| 3 | HPG27_488 | HP0529 | HPP12_0536 | CagW | 32, 33, 48 |

| 2 | HPG27_485 | HP0526 | HPP12_0533 | CagZ | 37, 42 |

| 1 | HPG27_497 | HP0539 | HPP12_0546 | CagL | 50 |

| 1 | HPG27_502 | HP0543 | HPP12_0550 | CagF | 54 |

| 2 | HPG27_480 | HP0521 | HPP12_0528 | Cag2 | 60, 72 |

| 1 | HPG27_479 | HP0520 | HPP12_0527 | Cag1 | 73 |

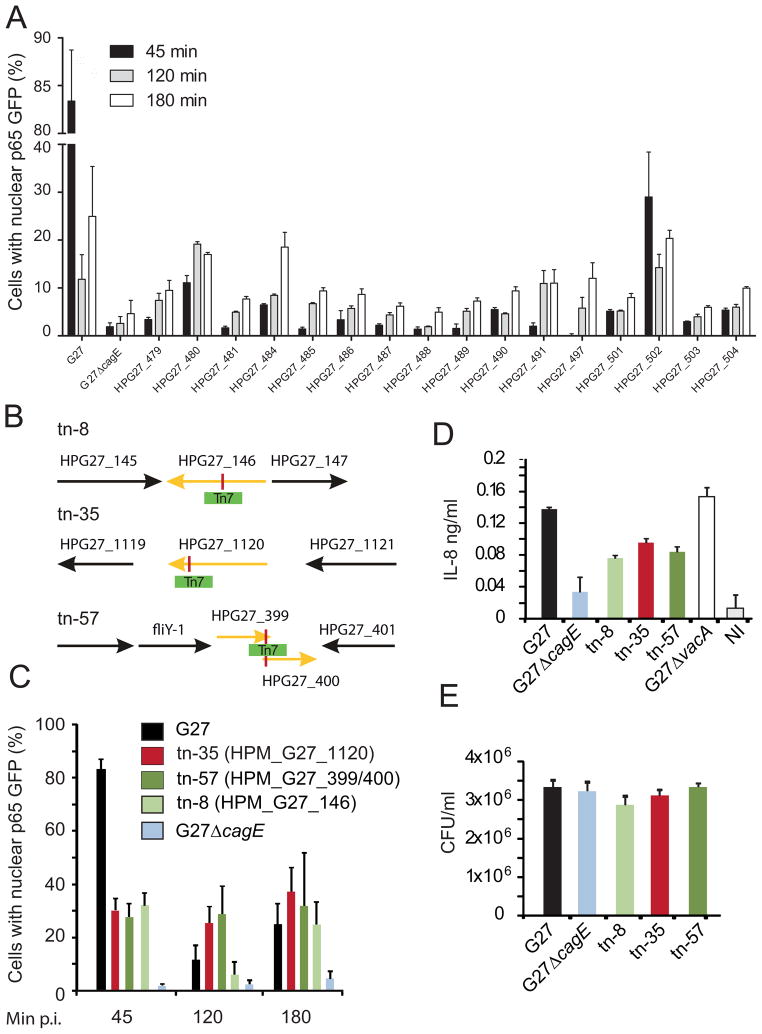

Figure 2. Genome-wide bacterial screen identifies 59 mutants inhibiting NF-kappaB activation.

(A) Bar diagram displaying NF-κB activation patterns after infection of AGS SIB02 cells with 56 identified cagPAI mutants carrying the transposon in 16 different cagPAI genes. AGS SIB02 cells were infected with respective mutants (MOI 100) for 45, 120 and 180min. G27 and G27ΔcagE were used as controls. After fixation p65 translocation was quantified using an automated microscope and subsequent computational analysis (ScanR; Olympus). Error bars indicate mean ± SD of three independent experiments. (B) Transposon loci were identified by genomic sequencing applying transposon specific primers. Targeted genes (indicated in yellow) as well as neighboring cells are shown. (C) Bar diagram displaying NF-κB activation patterns after infection of AGS SIB02 cells with G27 and G27ΔcagE controls, and transposon mutants tn-35, -57, and -8. (D) IL-8 secretion from AGS SIB02 cells infected with mutants and respective controls. Cells were infected for 8h. IL-8 secretion was determined by ELISA. (E) CFU assay of adhered bacteria 6h p.i Error bars indicate mean ± SD of three technical replicates. HPG27_145: hypothetical protein; HPG27_146: lipopolysaccharide 1,2 glycosyltransferase; HPG27_147: cysteine rich protein D; HPG27_1119: hypothetical protein; HPG27_1120: outer membrane protein (HopQ); HPG27_1121: purine-nucleoside phosphorylase; HPG27_399: hypothetical protein; HPG27_400: hypothetical protein (fibronectin type II domain); HPG27_401: ferric uptake regulation protein.

The remaining three transposon mutants contained insertions in non-cagPAI genes (Fig. 2B and Table II). One insertion (tn-57) mapped to a region of overlap in two hypothetical proteins, the second (tn-8) mapped to a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 1,2-glycosyltransferase and the third (tn-35) mapped to the OMP HopQ. As expected, tn-8 mutant bacteria showed substantially altered LPS (Fig. S4A). Although all three transposon mutants exhibited reduced NF-κB activation (45 min p.i.) and IL-8 secretion (6h p.i.) (Fig. 2C and 2D), host cell adherence (Fig. 2E) for all mutants was similar to wild type. Moreover, all mutants retained normal morphology, as shown by electron microscopy, and functioning flagella, as observed from soft agar assays (showing that the ability to form halos was unaffected in mutants) (Fig. S4B and S4C). These observations suggested that mutations at non-cagPAI H. pylori genomic loci directly affected a T4SS-dependent host cell response.

Table 2.

Identified non-cagPAI mutants

| Protein group | Definition | Gene | Ortholog (Hp 26695) | Ortholog (Hp12) | Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | LPS 1,2- Glycosyltransferase | HPG27_146 | HP0159 | HPP12_0158 | tn-8 |

| Outer membrane protein | HopQ | HPG27_1120 | HP1177 | HPP12_1142 | tn-35 |

| Flagellar associated protein/Toxin | Flagellar associated protein/Toxin | HPG27_399/400 | HP1029/HP1028 | HPP12_0415/HPP12_0416 | tn-57 |

Association of HopQ polymorphism with cagPAI status

Previous work revealed a degree of ‘co-inheritance’ between hopQ and cagPAI (Salama et al., 2000), and the hopQ gene exists in two allelic forms: alleles I and II. Allele I is generally present in H. pylori strains possessing the cagPAI. However, some strains harbour both alleles (Cao and Cover, 2002). On the basis of this interesting background information we decided to study a possible contribution of HopQ to T4SS-mediated pathogenesis in greater detail. A BLAST search revealed single hopQ genes in the published genome sequences of strains P12 (Fischer et al., 2010) and G27 (Baltrus et al., 2009). However, the allelic form of hopQ in these two strains had, until now, not been classified. Here, we repeated the sequence analysis of P12 hopQ and identified three nucleotide deviations from the published genome sequence (Fischer et al., 2010); namely, the absence of an adenine (position 1188) and two guanine residues (positions 1141 and 1209). This led to an amendment of the internal reading frame (between amino acid residues 380 and 401; Table S1) with a net loss of one amino acid from the P12 HopQ protein sequence (AcsNo: JF303025). An obvious discordance in a short (21 amino acid) fragment of the published sequence (ACJ08294) with aligned sequences of known HopQ proteins of allele I and II strains (27 and 8, respectively) was thus excluded in our revised P12 HopQ sequence (Table S2). Phylogenetic analysis with MEGA 4.0 software (Tamura et al., 2007) subsequently revealed that the P12 and G27 hopQ genes, as well as their gene products, group with the type I allele (Fig. S5). The P12 and G27 hopQ genes thus constitute genuine type I alleles.

HopQ deficient mutants do not exhibit altered bacterial morphology, cell adherence or motility

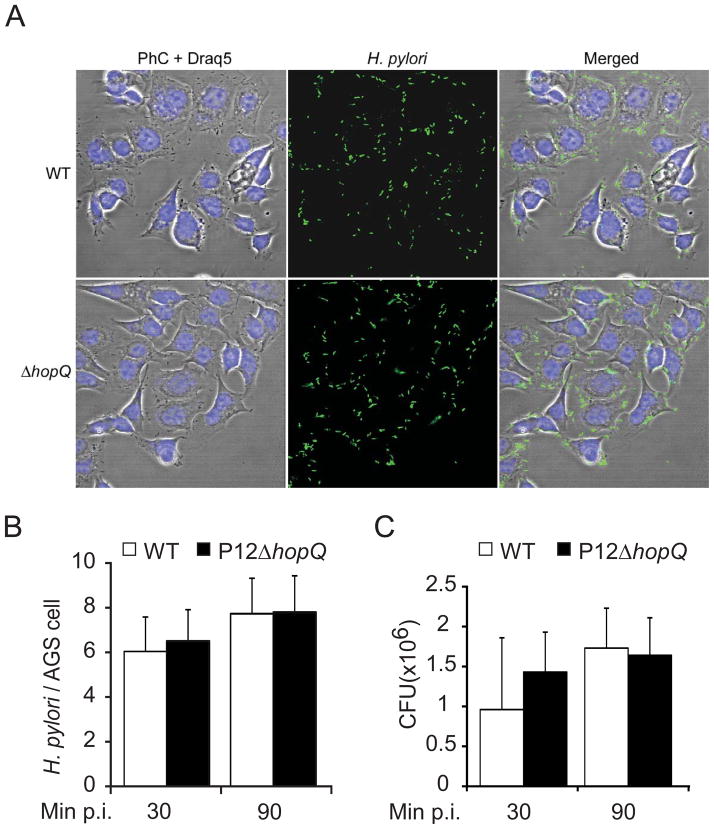

Several Hop family members in H. pylori have been implicated in both adherence and phase variable expression (Alm and Trust, 1999, Talarico et al., 2012). Although previous work on four different H. pylori strains (26695, J99, J178 and 87–29) suggested that HopQ can contribute to bacterial adhesion, this activity appears to be strain-specific, since two strains showed no changes in adherence (Loh et al., 2008). In order to determine whether our results might be caused by decreased bacterial adhesion, we analyzed the G27-derived HopQ transposon mutant, but this did not reveal any detectable alteration in adherence as compared to wild type bacteria (Fig. 2E). Similarly, H. pylori P12ΔhopQ did not show detectable differences in cell adherence. To further validate this observation, we monitored the binding behaviour of P12ΔhopQ and isogenic wild type to AGS cells at different time points of infection (30 and 90 min p.i., MOI 50) using immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3A, 3B and S6), and we determined the colony forming units (CFU) of adherent bacteria (Fig. 3C). This analysis clearly demonstrated that the HopQ defect did not alter the number of adherent P12 or G27 bacteria on the human epithelial cells. Nonetheless, this result does not exclude a likely function of HopQ as an adhesin, since adhesin phenotypes could be masked in strains expressing several adhesins at a time (Yamaoka et al, 2002b, Robertson and Meyer, 1992).

Figure 3. Bacterial adherence to AGS cells is HopQ independent.

(A–C) Adherence of the H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT) and its mutant (ΔhopQ) to AGS cells. (A) Micrographs of H. pylori (green) attached to AGS cells. Bacteria are visualized by immunofluorescence (green), DRAQ-stained DNA from nuclei and bacterial chromosome (Draq5, blue), and phase-contrast (PhC) (Scale bar, 20 μm. B) Number of adherent bacteria per single AGS cell were enumerated by direct counting through immunofluorescence microscopy. (C) Quantification of CFU after 30 and 90min of infection. Errors bars show standard deviation (± SD) of three independent experiments.

To further exclude that altered NF-κB activation was due to impaired bacterial motility or differences in bacterial morphology, we performed soft agar motility assays and transmission electron microscopy using the P12ΔhopQ strain. The results of these analyses confirmed the transposon mutant observations that HopQ deficient bacteria exhibit similar motility and morphology (bacterial cell shape and surface structure) to wild type strains (Fig. S7 and S8). Thus, our data indicates that mechanisms other than decreased bacterial attachment and/or altered motility/morphology are responsible for the reduced capacity of hopQ-mutants to activate NF-κB.

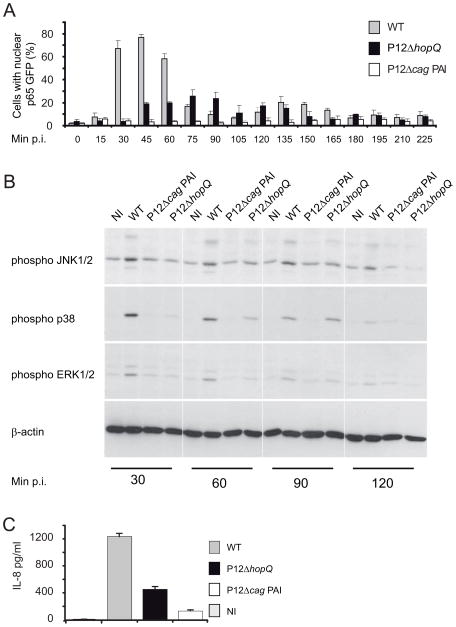

The hopQ defect broadly impairs activation of cag-T4SS-dependent host cell signalling routes

A hallmark of H. pylori infections is the induction of a strong pro-inflammatory host cell response via the activation of two major parallel signalling routes: the NF-κB and MAP kinase pathways (reviewed in Backert and Naumann, 2010). To substantiate the observed effect of HopQ on T4SS-dependent NF-κB activation, we extended the time course experiments of AGSSIB02 cell infection using the hopQ deletion mutant (P12ΔhopQ), and the wild type P12 and P12ΔcagPAI congenic strains as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 for up to 225 min. Wild-type P12 infection induced p65-GFP nuclear translocation from 30 min p.i., reaching a peak at 45 min p.i. while no p65-GFP nuclear translocation was observed upon infection with the mutant P12ΔcagPAI strain (Fig. 4A), which was consistent with previously described T4SS-dependency of NF-κB activation (Schweitzer et al., 2010). Interestingly, infection with the P12ΔhopQ mutant caused a ~2.5-fold decrease in p65-GFP nuclear translocation compared with wild type. Additionally, the peak of activation was delayed, shifting to 75 min p.i. (Fig. 4A). In order to confirm the HopQ dependency of T4SS-mediated NF-κB activation, we complemented the P12ΔhopQ knock-out mutant with an intact hopQ gene. This restored the p65 translocation phenotype in infected cells (Fig. S9) corroborating the notion that HopQ is functionally linked with the T4SS.

Figure 4. HopQ triggers cagPAI dependent host cell signal transduction pathways.

(A) Infection time course (0–225 min) with WT, P12ΔhopQ mutant and P12ΔcagPAI (MOI 100). Activation of NF-κB was assessed by nuclear p65 translocation. Numbers of activated cells are given as a percentage of total cell number. (B) Activation of pro-inflammatory pathways in AGS cells upon infection with the H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT), P12ΔhopQ and P12ΔcagPAI mutants in comparison to non-infected AGS cells (NI). Immunoblot analysis showing activation of MAPK JNK1/2, p38, and ERK1/2. Blots are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Production of IL-8 estimated by ELISA; NI, non-infected AGS cells. Errors bars in A and C show ± SD of three independent experiments.

We then investigated the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), p38, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1/2 (JNK1/2) (Keates et al., 1999) by determining the phosphorylation of respective pathway components. Infection with the wild type strain resulted in phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38 and JNK1/2, which reached its maximum peak between 30 to 60 min p.i. (Fig. 4B). By contrast, infection with the P12ΔcagPAI strain resulted in marked attenuation of JNK1/2 and p38 activation and decreased as well as delayed ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 4B). These findings demonstrate that HopQ also facilitates T4SS-dependent MAPK pathway activation.

Both MAPK and NF-κB pathways culminate in the activation of several pro-inflammatory target genes, including the IL-8 gene (Aihara et al., 1997). Hence, we determined the potential of P12ΔhopQ to stimulate IL-8 secretion in AGS cells compared with P12 wild type and P12ΔcagPAI. IL-8 levels were monitored in cell culture supernatants 6 h p.i. by ELISA. Consistent with the results obtained with transposon mutant-35 (Fig. 2D), IL-8 secretion in AGS cells was ~2-fold lower following infection with the mutant P12ΔhopQ compared with P12 wild type (Fig. 4C). This observation correlated with reduced levels of NF-κB activation upon infection with the P12ΔhopQ mutant strain. Taken together, the isogenic deletion mutant P12ΔhopQ stimulated a reduced T4SS-dependent inflammatory host cell response, which ranged between the levels of the wild type strain P12, and the congenic P12ΔcagPAI T4SS mutant.

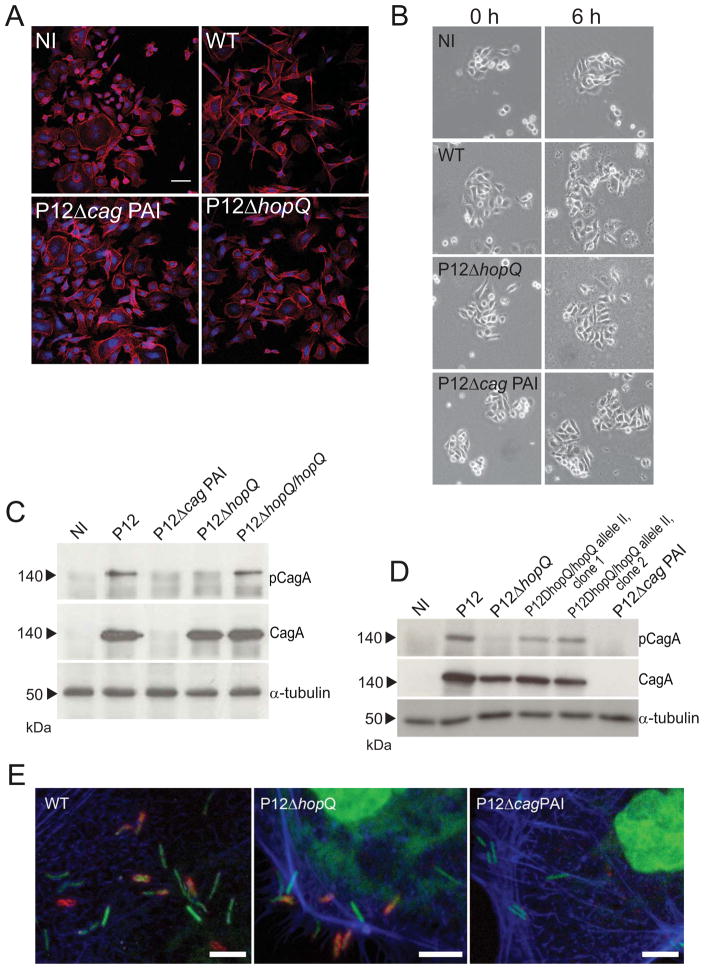

HopQ is essential for CagA translocation

A prominent function of the cagPAI-encoded T4SS is the translocation of the effector CagA into gastric epithelial cells, resulting in the activation of several cellular responses (Censini et al., 1996, Tomb et al., 1997, Keates et al., 1999). One striking phenotype of CagA is its effect on cell morphology of AGS gastric epithelial cells (hummingbird phenotype) and cell motility (Segal et al., 1999, Stein et al., 2002, Moese et al., 2004). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed hummingbird formation in AGS cells only when infected with the CagA-expressing P12 wild type strain, but no notable changes of cell morphology occurred during infection with either P12ΔhopQ or P12ΔcagPAI (MOI 100; 6 h p.i.; Fig. 5A). Consistently, phase contrast microscopy revealed increased cell scattering, indicative of motility, after infection with wild type P12, whereas minimal scattering occurred after infection with either hopQ or cagPAI mutant strains (Fig. 5B). To assess the ability of the P12ΔhopQ strain to translocate CagA into infected host cells, we determined CagA phosphorylation as a marker for its translocation (Odenbreit et al., 2000, Stein et al., 2000). In accordance with our phenotypic analyses, no, or very minor levels of, CagA phosphorylation was observed in P12ΔhopQ infected AGS cells, although the hopQ mutant expressed similar levels of CagA protein as wild type bacteria (Fig. 5C). As depicted in Fig. 5C, genetic complementation of the mutant hopQ restored the ability of H. pylori to translocate CagA. Furthermore, in an equivalent fashion, we also complemented the P12ΔhopQ mutant with an intact hopQ gene from strain Tx30a that contains hopQ allele II (Fig. 5D). The result suggests that hopQ allele II, too, can functionally restore P12ΔhopQ.

Figure 5. HopQ is essential for CagA translocation.

(A) Development of hummingbird phenotype and (B) scattering in AGS cells upon infection with the H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT) and with its isogenic mutants P12ΔhopQ and P12ΔcagPAI in comparison to non-infected AGS cells (NI). Development of hummingbird phenotype was assessed by immunofluorescence microscopy at 6 h p.i.. Actin stained by phalloidin A546 is shown in red, DRAQ-strained DNA from nuclei and bacterial chromosome are shown in blue. (C) CagA phosphorylation in AGS cells upon infection with H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT), with its isogenic mutants P12ΔhopQ and P12ΔcagPAI and the complemented hopQ mutant (P12ΔhopQ/hopQ.) in comparison with non-infected AGS cells (NI). The infection was performed at the MOI of 100 for 3 h. Phosphorylated CagA (pCagA), total amount of CagA (CagA) and AGS cells (β-actin or α-tubulin) were estimated with specific antibodies by immunoblot analysis. Scale bar, 50μm. Scattering of AGS cells was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy at different time points. Blots and microscopy pictures are representative of three independent experiments. (D) CagA phosphorylation in AGS cells upon infection with H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT), with its isogenic mutants P12ΔhopQ and the H. pylori mutant with exchanged hopQ alleles (P12ΔhopQ/hopQ allele II, clone 1 and clone 2.) and P12ΔcagPAI and in comparison with non-infected AGS cells (NI). The infection was performed at the MOI of 100 for 3 h. Phosphorylated CagA (pCagA), total amount of CagA (CagA) and AGS cells (α-tubulin) were estimated with specific antibodies by immunoblot analysis. (E) Micrographs of immunostaining for CagY (red), a component of T4SS, Phalloidin 488 (blue) and DRAQ5 (green) in H. pylori wild type strain P12 (WT), in its HopQ-deletion mutant (ΔhopQ) and in the cagPAI-deletion mutant (ΔcagPAI) after the infection of AGS cells for 30min. Images are projections of confocal stacks taken with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope Green and blue channels were interchanged to improve visualization of bacteria. (Scale bars: 5μm)

To address the question whether hopQ deletion can affect T4SS assembly we performed immunostaining experiments of CagY, one of the major proteins of the T4SS which is proposed to bind the T4SS-specific host cell receptor β1α5 integrin and therefore represents an important bacterial surface-located factor for T4SS function (Tanaka et al., 2003, Jiménez-Soto et al., 2009). As expected, CagY expression was only detectable in bacteria carrying the intact cagPAI. Both the wild type H. pylori P12 and P12ΔhopQ strains CagY revealed a similar patchy pattern of staining, reminiscent of local accumulation of CagY on the bacterial cell surfaces (Fig. 5E). This suggests T4SS formation was not fully distorted in hopQ-deleted bacteria and supports the notion of an accessory, rather than a central structural function of HopQ in the activation of the H. pylori T4SS (Fig. 5D.)

Discussion

The cagPAI-encoded T4SS is a major H. pylori virulence determinant (Tomb et al., 1997, Odenbreit et al., 1999, Alm et al., 2000). Its function has been implicated in severity of disease and increased risk of gastric cancer (Hatakeyama et al., 2006). One key effector role of the T4SS is translocation of the CagA protein, which is phosphorylated upon arrival in the host cells and triggers the activation of host cell signalling pathways. Major outcomes include the suppression of innate defence mechanisms (Bauer et al., 2012) and putatively oncogenic events involving cytoskeletal rearrangements (Segal et al., 1999, Odenbreit et al., 2000). However, even in the absence of CagA, the T4SS can activate pro-inflammatory signalling events in infected cells (reviewed in Backert and Naumann, 2010). T4SS-mediated delivery of bacterial peptidoglycan into host cells could be a mechanism of T4SS-dependent, but CagA-independent, activation of the pro-inflammatory response (Viala et al., 2004). Recent studies have also suggested a role for β1 integrins in docking of the T4SS to host cells (Kwok et al., 2007, Jiménez-Soto et al., 2009), an interaction that could mediate downstream perturbation of host cell signalling, as well as integrin linked kinase (ILK)/integrin β5 signalling complex, which could play a role in the activation of pro-inflammatory cascades in a T4SS-dependent, CagA-independent manner (Wiedemann et al., 2012). The proposed involvement of peptidoglycan and prominent host cell receptors did not rule out the existence of other potential, as yet unknown bacterial effectors or T4SS-associated determinants, which could function in pathogen-induced host cell responses. This possibility is supported by studies showing that pathways other than NOD-1 are involved in H. pylori-induced activation of, e.g. NF-κB and miR-155 (Maeda et al., 2000, Neumann et al., 2006, Backert and Naumann, 2010, Koch et al., 2012).

Here, we screened an H. pylori transposon mutant library for putative factors that modulate the pathogen-induced pro-inflammatory response in host cells using nuclear translocation of GFP-coupled p65 in human AGS epithelial cells as a measure of NF-κB activation. We identified 19 genes whose products influenced T4SS-dependent NF-κB activation and IL-8 secretion. The majority of transposon insertions that substantially reduced NF-κB activation occurred in 16 distinct cagPAI genes, thus confirming the central importance of the cagPAI for NF-κB activation. Interestingly, five cagPAI genes of H. pylori G27 (HPG27_479, HPG27_480, HPG27_485, HPG27_502, HPG27_504), previously described as having modest effects on H. pylori-induced IL-8 secretion (Fischer et al., 2001), were identified here as strong contributors to T4SS-dependent NF-κB activation. This discrepancy could be due to strain-specific differences (such as H. pylori 26695 vs. G27) or transposon-based polar effects on neighbouring genes. Of the three mutants carrying defects in non-cagPAI genomic regions in the H. pylori G27 genome, we could not clearly assign functions for two of them, being affected in hypothetical and LPS genes, respectively. Instead, we focussed our analysis on the most intriguing hit from our screen, HopQ, for which a functional association with T4SS has already been reported (Cao and Cover, 2002). Our studies thus extend current knowledge on the existence of T4SS accessory factors that appear to be intricately associated with H. pylori pathogenicity, including flagellar motility (Asakura et al., 2010), bacterial attachment via OipA (Dossumbekova et al., 2006), and the regulation of cagPAI gene expression (Hp1451, (Hare et al., 2007).

Depletion of HopQ substantially reduced both the induction of cagPAI-associated pro-inflammatory signalling and the translocation of the pathogen’s main effector protein CagA, even though this protein and CagY, a structural component of T4SS, appeared to be properly produced and positioned in the mutant. While the pro-inflammatory host cell response to H. pylori infection culminates in the production of cytokines such as IL-8, the precise role of CagA in IL-8 induction remains controversial. Whereas CagA has been shown to induce IL-8 expression in a strain-dependent fashion (Brandt et al., 2005, Argent et al., 2008) which stimulates only minor increases in IL-8 expression (Ritter et al., 2010), NF-κB activation has been demonstrated to be independent of CagA (Schweitzer et al., 2010). Here, we found that the depletion of HopQ reduced both pro-inflammatory signalling and CagA translocation, thus indicating that HopQ broadly influenced T4SS activation. Moreover, in agreement with defective CagA translocation in the HopQ mutant, there was no development of the characteristic host cell phenotype resulting from CagA translocation: host cell elongation, ‘hummingbird phenotype’, and increased host cell motility (Segal et al., 1999, Higashi et al., 2002, Tsutsumi et al., 2003, Suzuki et al., 2005). At the same time, weak and delayed activation of MAPK p38 and JNK1/2, NF-κB and IL-8 secretion observed after infection with the P12ΔhopQ mutant could be facilitated by bacterial factors in a T4SS-dependent, but CagA-independent manner, as mentioned above. The mild host cell responses induced by the hopQ-deletion mutant could not be explained by any decrease in the number of adherent bacteria or motility because these respective measurements were comparable to those of the parental strain. Finally, genetic complementation of the mutant P12ΔhopQ restored the wild type infection phenotype indicating that deletion of the hopQ gene was responsible for the observed phenotype.

Both H. pylori strains (P12 and G27) investigated carried the hopQ allele I, previously found to be ‘co-inherited’ with cagPAI, which is contained in highly pathogenic H. pylori strains (Salama et al., 2000, Cao and Cover, 2002). Our current observations support the notion that a functional link exists between HopQ and the T4SS and nurture speculations that allelic divergence of HopQ could have an impact on T4SS function. However, our preliminary studies on the phenotypic rescue of the P12ΔhopQ mutant with hopQ allele II from the H. pylori Tx30 did not support this hypothesis in the infection model that we have used.

Several previous observations are in line with the idea of HopQ being an adhesive factor. The hopQ gene exhibits pronounced homology to several well characterised adhesion genes in the H. pylori genome (Alm et al., 2000). The sabA and sabB genes, known to encode prominent sialyl-Lewis specific adhesins (Mahdavi et al., 2002), and hopQ further are part of a combinatorial family that undergoes gene conversion in the genome (Talarico et al., 2012). Both these facts strongly suggest a functional relationship between the three factors. Moreover, the structure of H. pylori Hops is reminiscent of the large family of autotransporter proteins of gram-negative bacteria, the majority of which represent adhesins (Henderson and Nataro, 2001). Intriguingly, a subclass of autotransporters occurs as trimers (Cotter et al., 2005), which could, in principle, allow the formation of hetero-complexes. Whether SabA, SabB and HopQ are involved in such complex formation is currently unknown, but it could provide a rationale even for increased adherence upon HopQ depletion from hetero-complexes (Loh et al., 2008). Therefore, our findings are consistent with the notion that HopQ exhibits adhesive properties, but has no net effect on the number of bacteria attaching to host cells. However, a site-specific adherence property of HopQ could be instrumental in conferring contacts of H. pylori’s T4SS to the host cell surface, providing a tantalizing explanation for the observed role of HopQ in T4SS function.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains, cell culture and cultivation

H. pylori wild type strains G27 and P12 (MPIIB strain collection numbers P409 and HP8880), and the mutants P12ΔcagPAI (Backert et al., 2001, Kwok et al., 2002), G27ΔflaA and P12ΔhopQ were grown on horse serum agar plates containing vancomycin (10μg ml−1), trimethoprim (5μg ml−1), and nystatin (1μg ml−1) under microaerobic conditions (85% N, 10% CO, 5% O) at 37 °C. The mutant P12ΔcagPAI was grown on agar plates supplemented with kanamycin (8μg ml−1); for cultivation of P12ΔhopQ, G27ΔflaA and G27-derived transposon mutants including G27ΔvacA, agar medium was supplemented with chloramphenicol (4μg ml−1). Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Invitrogen) was grown on Luria-Bertani (Sambrook et al., 2001) agar plates or in liquid medium supplemented with ampicillin (100μg ml−1) or chloramphenicol (40μg ml−1). Conjugation experiments were performed using E. coli strain β2155 (Dehio and Meyer, 1997), grown on the same media supplemented with diaminopimelic acid (0.2 mM). AGS cells (human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line, ATCC CRL-1739) and AGSSIB02 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) in a humidified 5% CO atmosphere at 37°C.

Screening of H. pylori G27 Tn7-mutant library and p65 translocation assay of individual H. pylori P12 strains

Preparation of bacterial inocula

An H. pylori G27 mini-Tn-7 transposon (Tn7) mutant library comprising ca. 10,000 clones (Salama et al., 2004) was used for the screening assay. H. pylori G27 wild type and the transposon mutant G27ΔvacA2 were used as positive controls, whereas the isogenic deletion mutant G27ΔcagE was used as negative control. The Tn7 library and control strains were grown on GC agar under microaerophilic conditions at 37°C. GC agar plates used for library incubation were supplemented with chroramphenicol (4μg ml−1). After 2 days, 96 single clones per plate (containing 3 different controls) were picked and transferred to new plates containing no chloramphenicol (Fig. S1). Colonies were incubated again for 2 days under microaerophilic conditions at 37°C. Single clones were resuspended in 100μl BHI broth containing 10% FCS in a 96-well tissue culture plate (TPP), followed by incubation for 1h at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions.

Automated infection and p65 translocation assay

The monoclonal p65-GFP expressing cell line (AGSSIB02) (Bartfeld et al., 2009) was used for automated infection. Cells were seeded in 100μl RPMI containing 10% FCS into 96-well-plates one day prior to activation to obtain a confluency of approximately 70%. Bacteria (25μl) were added at each time point by a Biomek FP Workstation (Fig. S1). Infection was stopped 45min, 120min and 180min p.i. and cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, stained with Hoechst 33342 (2μg/ml) and stored in PBS until analysis. In each well, four pictures were taken by the automated microscopy system Scan^R (Olympus) using autofocus on nuclei. Automated image analysis to quantify translocation of p65-GFP was performed as described previously (Bartfeld et al., 2010). Briefly, activated cells were assigned by quantification of cells showing nuclear p65-GFP using ScanR image analysis software (Olympus).

Statistics

Graphs were compiled using Microsoft Excel and Graph-Pad Prism. R-Script based analyses were performed to calculate activated cells (percent), NF-κB activation intensity per well, Z-score and Z-factor (Fig. S2). The Z-score expresses the divergence of the experimental result x from the most probable result μ as a number of standard deviations δ.

where μ=mean; δ=standard deviation

The Z-factor is a measure of statistical effect size, and is used in high-throughput screening to judge whether the response measured warrants further analysis (Zhang et al., 1999). Z-scores were calculated for controls and mutants (Fig. S2). Hits were then classified as activating or inhibitory (−0.5 and −6, respectively) (Fig. S3) and further validated by two additional screening rounds.

p65 translocation assay after infection with individual H. pylori P12 strains

Generally, this was performed as above using parental strain P12, mutants P12ΔhopQ and P12ΔcagPAI at MOI 100.

Identification of transposon mutation loci

Genomic bacterial DNA was isolated using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Transposon loci were identified by DNA sequencing using the Primer S2 (5′-CAGTTCCCAACTATTTTGTCC-3′; (Salama et al., 2004)). Sequences were analyzed by BLASTN search against the NCBI non-redundant (nr) database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and exact transposon loci were determined by in silico genome analysis of identified gene (Fig. S2B).

Deletion and complementation of hopQ gene

The P12ΔhopQ mutant was constructed by replacing the hopQ gene with a chloramphenicol resistance gene cassette (CmR, 1kb), which was isolated from the plasmid pDH80 using endonuclease BamH I. Briefly, DNA fragments of ca. 0.5kb in length were amplified from chromosome of the parental strain P12 using following primer set (synthesized by TIB Molbiol, Germany) carrying BamH I restriction sites (underlined): (i) hp1141f (5′-CTCGGTGGCAATGTTAGTGTTGTGTTCTTT-3′) and hp1142r (5′-GACTGGATCCGGCTTTATAGCGTGTATCTC-3′) for upstream, and (ii) hp1142iGf (5′-GACTGGATCCAGATGTTCCTTAAAGTAATG-3′) and hp1143r (5′-CTTATGCTCAGTCTCAGATCACTTAATCAC-3′) for downstream DNA fragments flanking hopQ gene, respectively. The amplicons were subsequently cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Germany) and separated by the CmR gene at the BamH I restriction site. Genetic complementation of isogenic H. pylori mutant P12ΔhopQ was performed using a derivative of the E. coli-H. pylori shuttle plasmid pHel3, designated pIB6 (Haas et al., in preparation). For that, the hopQ gene was amplified from chromosome of the H. pylori strain P12 using the forward primer CE68 5′-GATCGTCGACATGAAAAAAACGAAAAAAAC-3′ containing a Sal I restriction site (underlined) and the reverse primer CE69 5′-GATCAGATCTTTTAATACGCGAACACATAA-3′ containing a Bgl II restriction site (underlined). The purified PCR product was directly digested with Sal I and Bgl II and ligated into the vector pIB6 at the corresponding restriction sites that resulted in plasmid pCE4. Conjugation of these shuttle vectors, carrying the hopQ gene, from E. coli β2155 to H. pylori strain P76 was performed under previously described mating conditions (Heuermann and Haas, 1998). Since growth of strain β2155 is dependent on exogenously supplied diaminopimelic acid, inoculation of serum plates without diaminopimelic acid is a strong counter selection against the donor strain. Shuttle vector was re-isolated from H. pylori strain P76 using Wizard Plus SV Minipreps Kit (Promega, USA). Purified shuttle vector and plasmid carrying the construct for hopQ deletion were introduced to H. pylori P12 strain by natural transformation (Haas et al., 1993). HopQ gene knockout was confirmed by PCR amplification using primers s1141f (5′-TGGTGATAAAGGTCGTTAAACCCGC-3′) and s1143r (5′-GCCTTAGCGTTTAGTTCCATCGCCG-3′) spanning a DNA fragment of ca. 3 kb in length up- and downstream of sites targeted by primers hp1141f and hp1143r. PCR products were purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) and were subjected to restriction analysis with BamH I endonuclease; additionally, amplicons were sequenced using the s1141f and s1143r primers.

Genetic complementation of isogenic H. pylori mutant P12ΔhopQ with hopQ allele II was performed using hopQ amplified from the strain Tx30a with primers CE68 (as above) CE62 (ACTTTTTACAACCAGCCAG), CE67 (GATCGTCGACATGTACCCATACGATGTTCCAGATTACGCTATGAAAAAAACGAAA AAAAC) containing a Sal I restriction site (underlined) and an HA tag (bold), and the reverse primer CE70 (GATCAGATCTTTTAATAGGCAAACACATAA) containing a Bgl II restriction site (underlined). Further procedures were similar to those described above.

Infection assays

For infection experiments, AGS cells were grown in 12-well tissue culture plates for 1–2 days to reach 70 to 80% confluence. Further, AGS cells were incubated in serum-free RPMI medium for 3 h before infection. Bacteria harvested from agar plates were washed, resuspended in RPMI medium and added to AGS cells at an assay–specific multiplicity of infection (MOI). Infection was carried out at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere supplemented with 5% CO. Samples were taken 30, 60, 90, 180 min and 6 h p.i.

Adherence assay, CFU quantification, immunofluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy

The adherence of the H. pylori parental strain P12 and the P12ΔhopQ mutant was analyzed by counting colony-forming units (CFU) on agar plates and by direct enumeration of bacterial cells using immunofluorescence microscopy. Infections with P12 and P12ΔhopQ were performed at an MOI of 50 for 30 and 90 min. Adherent H. pylori strains were recovered from AGS cells by dispersing in RPMI medium supplemented with 0.5% saponin (Serva) as described previously (Wunder et al., 2006). Serial dilutions of recovered bacteria were plated onto horse serum agar plates to determine CFU. For immunofluorescence microscopy, AGS cells were grown on cover slips under conditions described above. After infection, AGS cells with adherent H. pylori were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (137mM NaCl; 2.7mM KCl; 10mM NaHPO; 2mM KHPO) for 20 min at room temperature (RT) followed by three washes with PBS.

Samples were incubated in blocking buffer without detergent containing 3% cold water fish gelatine, 4% donkey serum, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0,2% BSAc for 30 min at 37°C to block non-specific binding. For CagY visualization, bacteria were incubated with CagY-specific antibody, followed by washing three times with PBS and incubation with goat anti-rabbit Cy3-linked (Dianova) secondary antibody. Cells were also stained with Phalloidin 488 and DRAQ5 (Enzo Life Sciences), washed three times with PBS and mounted on slides with mowiol. H. pylori cells were detected, by incubating in 1% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 1 h at RT to block non-specific binding followed by incubation with primary rabbit anti-H. pylori antibody (Biomol, Germany), followed by three washes in PBS and incubation with secondary goat anti-rabbit Cy2-linked antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, UK), for 1h at RT. Cells were also stained with DRAQ5 (Enzo Life Sciences, Germany), washed three times with PBS and mounted on slides with mowiol. A monoclonal mouse anti-p65 antibody (Santa Cruz, USA) was used to monitor nuclear p65 translocation of AGS cells infected with G27.

For the calculation of adherence properties in total, images of at least 30 random fields of view from three independent experiments were acquired using a Leica TCS SP laser confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany). AGS cells were counted manually from obtained images. Adherent H. pylori cells were quantified using ImageJ 1.37 software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) with thresholds manually set for individual images and circularity 0.05–1.00; each count was verified manually. Parameters for bacterial counts were established in preliminary experiments using a pure culture of H. pylori (data not shown). Statistical analysis of bacterial counts was then performed by t-test. Significance was set at P< 0.05.

Hummingbird phenotype and cell scattering

Development of the hummingbird phenotype in AGS cells was assessed upon infection with P12, P12ΔhopQ and P12ΔcagPAI at MOI of 100. Samples were analyzed after 0, 2, 4 and 6h of infection. AGS cells were fixed as described above, treated with 0.2% Triton X100 in PBS for 20min at RT and incubated with Alexa Fluor® 546 (A546) phalloidin (Invitrogen, Germany) and DRAQ5 to stain actin and DNA, respectively. Cells were visualized using a Leica TCS SP laser confocal microscope. For scattering assay, AGS cells were infected as above described and their motility was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy using an inverted microscope (model IX50-S8F; Olympus) at the same time points.

H. pylori motility assay

The motility of H. pylori parental strains G27 and P12, mutants P12ΔhopQ, G27ΔflaA and four G27 transposon mutants was assessed using soft agar plates, as described previously (Worku et al., 2004), with minor modifications. Briefly, approximately 109 H. pylori cells in a final volume of 3μl were spotted onto horse serum soft agar plates containing agar (0.5%) and FCS (10%). Plates were incubated for three days under microaerobic conditions. The diameters of the halos were measured by using a ruler.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in 1× Laemmli buffer (60mM Tris (pH6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue). Proteins (25μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel (10%) electrophoresis and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Perkin Elmer) in buffer (25mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 20% methanol). Non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubation in blocking buffer (0.05M Tris (pH7.4), 0.2M NaCl, 3% Tween, 3% BSA) for 1h at RT before probing with primary antibodies against phospho- JNK1/2, phospho-p38 (Cell Signaling Technology, Germany), phospho- ERK1/2, β-actin, (Sigma, Germany), phospho-Tyr (PY99 and CagA, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Germany; (Odenbreit et al., 2000)), all at a final dilution of 1:1000 in blocking buffer supplemented with 3% BSA. Secondary HRP-labelled goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse antibodies (GE Healthcare, Germany) were used at a dilution of 1:3000 in the same buffer. The blots were detected on the X-ray film X-OMAT (Kodak, USA) after treatment with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (ECL) (Pierce, USA). Band intensities were quantified from processed images using Photoshop CS3 (Adobe) and normalised to respective loading controls.

IL-8 secretion

IL-8 production by AGS cells was assessed following infection with H. pylori strains (MOI 100, 6 h and 8 h respectively). IL-8 was measured in the supernatants by ELISA using a sandwich ELISA kit (R&D Systems, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokine secretion was measured in at least three independent experiments carried out in triplicate.

Scanning electron microscopy

Fresh cultures of H. pylori wild type strain P12 and the isogenic mutant P12ΔhopQ, were harvested from agar plates, washed twice in PBS and then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/PBS solution for 20 min at RT. H. pylori wild type strain G27 and the transposon mutants (Tn-8, Tn-35, Tn-57) were inoculated in BHI broth (OD: 0.2) and incubated for 12 h in a shaking incubator at 37°C (110rpm). Samples were washed once in PBS and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/PBS by RT for 30min. After washing again in PBS and water, samples were postfixed in 0.5% Osmiumtetroxide, contrasted with 1% tannic acid, and incubated in 0.5% OsO, with intermediate washing. Samples were then dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and subjected to critical point drying followed by coating with a layer of 10nm carbon. The samples were analyzed with Leo 1550 scanning and transmission electron microscope.

In silico analyses of hopQ gene and HopQ protein sequences

The hopQ gene and protein sequences were downloaded from the NCBI database. The hopQ gene of H. pylori strain P12 was fully sequenced using the primers 1142-F (5′-AAAAGCTCATCTTGTAAGGTAATTTT-3′) and 1142-R (5′-TTTTTTGCAATAAAA-CATTACTTT-3′), and with OP5136c (5′-CAACGATAATGGCACAAACT) and OP4829d (5′-GTCGTATCAATAACAGAAGTTG) (Cao and Cover, 2002). In silico translation of the sequenced hopQ and multiple alignments of nucleotide and protein sequences were carried out with BioEdit software (Hall, 1999). Phylogenetic analysis was performed with the MEGA 4.0 software (Tamura et al., 2007) using the neighbour-joining method and the Kimura 2-parameter model for gene sequences and Poisson correction for protein sequences. The sequence of P12 hopQ obtained from this work was deposited in GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ under accession numbers JF303025.

Quantification of Western blots

Western blot quantification of band intensities was performed directly from digital pictures which were processed using the computer software Photoshop CS3 (Adobe). Pictures were inverted and region of interest was defined. Histograms of selected regions displayed median of intensity and region size. All bands were normalized to background regions and respective band intensities of loading control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank Drs. Lesley Ogilvie, Kate Holden-Dye and Rike Zietlow for excellent editorial assistance on this manuscript. We also thank David Manntz, for the exceptional technical assistance at the Biomek FP Workstation and Dr. André Maeurer for his obliging technical support at the automated microscopy system Scan^R and Meike Soerensen, Dagmar Frahm, Joerg Angermann and Britta Laube for general technical support. This work was supported by research grants of the DFG (HA2697/10-1) to R.H. and funding under the Sixth Research Framework Programme of the European Union, Project INCA (LSHC-CT-2005-018704) and BMBF (ERA-NET PathoGenoMics - FunGen GA No. 0315435A) to T.F.M. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Aihara M, Tsuchimoto D, Takizawa H, Azuma A, Wakebe H, Ohmoto Y, et al. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced interleukin-8 production by a gastric cancer cell line, MKN45. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3218–3224. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3218-3224.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm RA, Bina J, Andrews BM, Doig P, Hancock REW, Trust TJ. Comparative Genomics of Helicobacter pylori: Analysis of the Outer Membrane Protein Families. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4155–4168. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4155-4168.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alm RA, Trust TJ. Analysis of the genetic diversity of Helicobacter pylori: the tale of two genomes. J Mol Med. 1999;77:834–846. doi: 10.1007/s001099900067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argent RH, Hale JL, El-Omar EM, Atherton JC. Differences in Helicobacter pylori CagA tyrosine phosphorylation motif patterns between western and East Asian strains, and influences on interleukin-8 secretion. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1062–1067. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.2008/001818-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura H, Churin Y, Bauer B, Boettcher JP, Bartfeld S, Hashii N, et al. Helicobacter pylori HP0518 affects flagellin glycosylation to alter bacterial motility. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:1130–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspholm M, Olfat FO, Nordén J, Sondén B, Lundberg C, Sjöström R, et al. SabA Is the H. pylori Hemagglutinin and Is Polymorphic in Binding to Sialylated Glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Moese S, Selbach M, Brinkmann V, Meyer TF. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 972 of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein is essential for induction of a scattering phenotype in gastric epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:631–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Naumann M. What a disorder: proinflammatory signaling pathways induced by Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Ziska E, Brinkmann V, Zimny-Arndt U, Fauconnier A, Jungblut PR, et al. Translocation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric epithelial cells by a type IV secretion apparatus. Cellular Microbiology. 2000;2:155–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnoli F, Buti L, Tompkins L, Covacci A, Amieva MR. Helicobacter pylori CagA induces a transition from polarized to invasive phenotypes in MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502598102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltrus DA, Amieva MR, Covacci A, Lowe TM, Merrell DS, Ottemann KM, et al. The Complete Genome Sequence of Helicobacter pylori Strain G27. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:447–448. doi: 10.1128/JB.01416-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfeld S, Engels C, Bauer B, Aurass P, Flieger A, Brüggemann H, Meyer TF. Temporal resolution of two-tracked NF-κB activation by Legionella pneumophila. Cellular Microbiology. 2009;11:1638–1651. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfeld S, Hess S, Bauer B, Machuy N, Ogilvie L, Schuchhardt J, Meyer T. High-throughput and single-cell imaging of NF-kappaB oscillations using monoclonal cell lines. BMC Cell Biology. 2010;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Moese S, Bartfeld S, Meyer TF, Selbach M. Analysis of Cell Type-Specific Responses Mediated by the Type IV Secretion System of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4643–4652. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4643-4652.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Pang E, Holland C, Kessler M, Bartfeld S, Meyer TF. The Helicobacter pylori virulence effector CagA abrogates human beta-defensin 3 expression via inactivation of EGFR signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:576–586. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer BM, Meyer TF. The human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori and its association with gastric cancer and ulcer disease. Ulcers. 2011;2011:Article ID 340157. [Google Scholar]

- Blaser MJ, Atherton JC. Helicobacter pylori persistence: biology and disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:321–333. doi: 10.1172/JCI20925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, König W, Backert S. NF-kappaB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P, Cover TL. Two Different Families of hopQ Alleles in Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.12.4504-4511.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Censini S, Lange C, Xiang Z, Crabtree JE, Ghiara P, Borodovsky M, et al. cag, a pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori, encodes type I-specific and disease-associated virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churin Y, Al-Ghoul L, Kepp O, Meyer TF, Birchmeier W, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:249–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churin Y, Kardalinou E, Meyer TF, Naumann M. Pathogenicity island-dependent activation of Rho GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42 in Helicobacter pylori infection. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:815–823. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter SE, Surana NK, St Geme JW., 3rd Trimeric autotransporters: a distinct subfamily of autotransporter proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter Pylori and Gastroduodenal Disease. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:135–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Meyer M. Maintenance of broad-host-range incompatibility group P and group Q plasmids and transposition of Tn5 in Bartonella henselae following conjugal plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:538–540. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.538-540.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doig P, Exner M, Hancock R, Trust T. Isolation and characterization of a conserved porin protein from Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5447–5452. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5447-5452.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossumbekova A, Prinz C, Mages J, Lang R, Kusters JG, Van Vliet AHM, et al. Helicobacter pylori HopH (OipA) and Bacterial Pathogenicity: Genetic and Functional Genomic Analysis of hopH Gene Polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1346–1355. doi: 10.1086/508426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exner M, Doig P, Trust T, Hancock R. Isolation and characterization of a family of porin proteins from Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1567–1572. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1567-1572.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinha P, Gascoyne RD. Helicobacter pylori and MALT Lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1579–1605. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Püls J, Buhrdorf R, Gebert B, Odenbreit S, Haas R. Systematic mutagenesis of the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island: essential genes for CagA translocation in host cells and induction of interleukin-8. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1337–1348. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Windhager L, Rohrer S, Zeiller M, Karnholz A, Hoffmann R, et al. Strain-specific genes of Helicobacter pylori: genome evolution driven by a novel type IV secretion system and genomic island transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6089–6101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glocker E, Lange C, Covacci A, Bereswill S, Kist M, Pahl HL. Proteins Encoded by the cag Pathogenicity Island of Helicobacter pylori Are Required for NF-kappa B Activation. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2346–2348. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2346-2348.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gressmann H, Linz B, Ghai R, Pleissner KP, Schlapbach R, Yamaoka Y, et al. Gain and Loss of Multiple Genes During the Evolution of Helicobacter pylori. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e43. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas R, Meyer T, van Putten J. Aflagellated mutants of Helicobacter pylori generated by genetic transformation of naturally competent strains using transposon shuttle mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TA. BioEdit:a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windonws 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hare S, Fischer W, Williams R, Terradot L, Bayliss R, Haas R, Waksman G. Identification, structure and mode of action of a new regulator of the Helicobacter pylori HP0525 ATPase. EMBO J. 2007;26:4926–4934. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama M, Brzozowski T. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Helicobacter. 2006;11:14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-405X.2006.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck CR, Meyer TF. ‘Small’ talk: Opa proteins as mediators of Neisseria-host-cell communication. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Nataro JP. Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1231–1243. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1231-1243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuermann D, Haas R. A stable shuttle vector system for efficient genetic complementation of Helicobacter pylori strains by transformation and conjugation. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;257:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s004380050677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi H, Tsutsumi R, Muto S, Sugiyama T, Azuma T, Asaka M, Hatakeyama M. SHP-2 Tyrosine Phosphatase as an Intracellular Target of Helicobacter pylori CagA Protein. Science. 2002;295:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A, Baltimore D. Circuitry of nuclear factor κB signaling. Immunol Rev. 2006;210:171–186. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilver D, Arnqvist A, Ögren J, Frick IM, Kersulyte D, Incecik ET, et al. Helicobacter pylori Adhesin Binding Fucosylated Histo-Blood Group Antigens Revealed by Retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Soto LF, Kutter S, Sewald X, Ertl C, Weiss E, Kapp U, et al. Helicobacter pylori Type IV Secretion Apparatus Exploits β1 Integrin in a Novel RGD-Independent Manner. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose J, Jahnig F, Meyer TF. Common structural features of IgA1 protease-like outer membrane protein autotransporters. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:378–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keates S, Keates AC, Warny M, Peek RM, Murray PG, Kelly CnP. Differential Activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in AGS Gastric Epithelial Cells by cag+ and cag− Helicobacter pylori. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;163:5552–5559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennemann L, Didelot X, Aebischer T, Kuhn S, Drescher B, Droege M, et al. Helicobacter pylori genome evolution during human infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5033–5038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018444108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Mollenkopf HJ, Klemm U, Meyer TF. Induction of microRNA-155 is TLR- and type IV secretion system-dependent in macrophages and inhibits DNA-damage induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1153–1162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116125109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok T, Backert S, Schwarz H, Berger J, Meyer TF. Specific Entry of Helicobacter pylori into Cultured Gastric Epithelial Cells via a Zipper-Like Mechanism. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2108–2120. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2108-2120.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok T, Zabler D, Urman S, Rohde M, Hartig R, Wessler S, et al. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh JT, Torres VJ, Scott Algood HM, McClain MS, Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori HopQ outer membrane protein attenuates bacterial adherence to gastric epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;289:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Wu JY, Beswick EJ, Ohno T, Odenbreit S, Haas R, et al. Functional and Intracellular Signaling Differences Associated with the Helicobacter pylori AlpAB Adhesin from Western and East Asian Strains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6242–6254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611178200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Akanuma M, Mitsuno Y, Hirata Y, Ogura K, Yoshida H, et al. Distinct Mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-mediated NF-κB Activation between Gastric Cancer Cells and Monocytic Cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44856–44864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Yoshida H, Ogura K, Mitsuno Y, Hirata Y, Yamaji Y, et al. H. pylori Activates NF-[kappa]B Through a Signaling Pathway Involving I[kappa]B Kinases, NF-[kappa]B-Inducing Kinase, TRAF2, and TRAF6 in Gastric Cancer Cells. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:97–108. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdavi J, Sonden B, Hurtig M, Olfat FO, Forsberg L, Roche N, et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science. 2002;297:573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Tanaka J, Asahi M, Haas R, Sasakawa C. Grb2 Is a Key Mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA Protein Activities. Mol Cell. 2002;10:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moese S, Selbach M, Kwok T, Brinkmann V, Konig W, Meyer TF, Backert S. Helicobacter pylori Induces AGS Cell Motility and Elongation via Independent Signaling Pathways. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3646–3649. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3646-3649.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Foryst-Ludwig A, Klar S, Schweitzer K, Naumann M. The PAK1 autoregulatory domain is required for interaction with NIK in Helicobacter pylori-induced NF-KB activation. Biol Chem. 2006;387:79–86. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, Kato I, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastric Carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Kavermann H, Puls J, Haas R. CagA tyrosine phosphorylation and interleukin-8 induction by Helicobacter pylori are independent from alpAB, HopZ and bab group outer membrane proteins. Int J Med Microbiol. 2002;292:257–266. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into Gastric Epithelial Cells by Type IV Secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenbreit S, Till M, Hofreuter D, Faller G, Haas R. Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1537–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K, Maeda S, Nakao M, Watanabe T, Tada M, Kyutoku T, et al. Virulence Factors of Helicobacter pylori Responsible for Gastric Diseases in Mongolian Gerbil. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck B, Ortkamp M, Diehl KD, Hundt E, Knapp B. Conservation, localization and expression of HopZ, a protein involved in adhesion of Helicobacter pylori. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3325–3333. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek RM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek RM, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter infection and gastric neoplasia. J Pathol. 2006;208:233–248. doi: 10.1002/path.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter B, Kilian P, Reboll M, Resch K, DiStefano J, Frank R, et al. Differential Effects of Multiplicity of Infection on Helicobacter pylori-Induced Signaling Pathways and Interleukin-8 Gene Transcription. J Clin Immunol. 2010:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson BD, Meyer TF. Genetic variation in pathogenic bacteria. Trends Genet. 1992;8:422–427. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama N, Guillemin K, McDaniel TK, Sherlock G, Tompkins L, Falkow S. A whole-genome microarray reveals genetic diversity among Helicobacter pylori strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14668–14673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama NR, Shepherd B, Falkow S. Global Transposon Mutagenesis and Essential Gene Analysis of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7926–7935. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7926-7935.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russel DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 2001. Appendix 2: Media. [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer K, Sokolova O, Bozko PM, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori induces NF-[kappa]B independent of CagA. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:10–11. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. Altered states: Involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SA, Tummuru MKR, Blaser MJ, Kerr LD. Activation of IL-8 Gene Expression by Helicobacter pylori Is Regulated by Transcription Factor Nuclear Factor κB in Gastric Epithelial Cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:2401–2407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Bagnoli F, Halenbeck R, Rappuoli R, Fantl WJ, Covacci A. c-Src/Lyn kinases activate Helicobacter pylori CagA through tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motifs. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Mimuro H, Suzuki T, Park M, Yamamoto T, Sasakawa C. Interaction of CagA with Crk plays an important role in Helicobacter pylori-induced loss of gastric epithelial cell adhesion. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talarico S, Whitefield SE, Fero J, Haas R, Salama NR. Regulation of Helicobacter pylori adherence by gene conversion. Mol Microbiol. 2012;84:1050–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) Software Version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Suzuki T, Mimuro H, Sasakawa C. Structural definition on the surface of Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion apparatus. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:395–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomb JF, White O, Kerlavage AR, Clayton RA, Sutton GG, Fleischmann RD, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi R, Higashi H, Higuchi M, Okada M, Hatakeyama M. Attenuation of Helicobacter pylori CagA·SHP-2 Signaling by Interaction between CagA and C-terminal Src Kinase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3664–3670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viala J, Chaput C, Boneca IG, Cardona A, Girardin SE, Moran AP, et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker MM, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter pylori Infection and the Pathogenesis of Duodenal Ulceration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;859:96–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb11114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedemann T, Hofbaur S, Tegtmeyer N, Huber S, Sewald N, Wessler S, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagL dependent induction of gastrin expression via a novel alphavbeta5-integrin-integrin linked kinase signalling complex. Gut. 2012;61:986–996. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worku ML, Karim QN, Spencer J, Sidebotham RL. Chemotactic response of Helicobacter pylori to human plasma and bile. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:807–811. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder C, Churin Y, Winau F, Warnecke D, Vieth M, Lindner B, et al. Cholesterol glucosylation promotes immune evasion by Helicobacter pylori. Nat Med. 2006;12:1030–1038. doi: 10.1038/nm1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, Kikuchi S, El-Zimaity HMT, Gutierrez O, Osato MS, Graham DY. Importance of Helicobacter pylori oipA in clinical presentation, gastric inflammation, and mucosal interleukin 8 production. Gastroenterology. 2002a;123:414–424. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, Souchek J, Odenbreit S, Haas R, Arnqvist A, Boren T, et al. Discrimination between cases of duodenal ulcer and gastritis on the basis of putative virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2002b;40:2244–2246. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.6.2244-2246.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaoka Y, Kwon DH, Graham DY. A Mr 34,000 proinflammatory outer membrane protein (OipA) of Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7533–7538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130079797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JH, Chung TDY, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomolecular Screening. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.