Abstract

Objectives

To analyse mortality, loss to follow-up (LTFU) and retention on antiretroviral treatment (ART) in the first year of ART across all age-groups in the Malawi national ART programme.

Design

Cohort study including all patients who started ART in Malawi’s public sector clinics between 2004 and 2007.

Methods

ART registers were photographed, information entered into a database and merged with data from clinics with electronic records. Rates per 100 patient-years and cumulative incidence of retention were calculated. Subhazard ratios (sHR) of outcomes adjusted for patient and clinic level characteristics were calculated in multivariate analysis, applying competing risk models.

Results

A total of 117,945 patients contributed 85,246 person-years: 1.0% were infants <2 years, 7.4 % children 2–14, 7.5% young people 15–24, and 84.2% adults 25 years and above. Sixty percent of patients were female: women outnumbered men from age 14 to 35 years. Mortality and LTFU were higher in men from age 20 years. Infants and young people had the highest rates per 100 person-years for mortality (23.0 and 19.4) and LTFU (24.7 and 19.3), and the highest adjusted relative risks compared to age group 25–34 years: sHRs were 1.37 (95%CI 1.17–1.60) and 1.17 (95%CI 1.10–1.25) for death and 1.37 (95%CI 1.18–1.59) and 1.27 (95%CI 1.19–1.35) for LTFU, respectively.

Conclusion

In this country-wide study patients aged 0–1 and 15–24 years had the highest risk of death and LTFU, and from age 20 and older men were at higher risk than women. Interventions to improve outcomes in these patient groups are required.

Keywords: Antiretroviral therapy, Malawi, mortality, loss to follow-up, retention on ART

INTRODUCTION

Antiretroviral (ART) programmes rapidly scaled up in many countries in Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years. To promote this process, WHO and UNAIDS developed a public health approach, based on clinical decision making, standardized and simplified treatment protocols, regimes, decentralised and free services at the point of care and a coordinated response to the epidemic, including a single monitoring and evaluation system [1, 2].

Monitoring of ART outcomes has been challenging [3].The lack of individual-level data is a major limitation of reports of many national ART programmes. Though large databases have been analysed [4–9], to our knowledge Thailand is the only country that has published nation-wide data at the level of the individual [10, 11]. Rwanda collected data on a representative sample of patients on ART [12]. With few exceptions [6], reports of adults and children are published separately, making a direct comparison of outcomes within a programme difficult.

By the end of 2009 Malawi achieved an ART coverage of 46%, based on the eligibility criteria of the 2010 WHO guidelines, using the public health approach [3]. The quality of the national ART monitoring and evaluation system has been assessed [13–15] and an analysis of aggregated data including adults and children concluded that the rapid ART scale up between 2004 and 2006 was successful [16]. However, the use of quarterly and facility-level data limited this analysis to cumulative outcomes and survival probabilities at 6 and 12 months.

Our aim was to analyse ART outcomes across all age groups and to examine factors related to progression to death, loss to follow-up (LTFU) and programme retention, based on individual-level data from the national ART register.

METHODS

The scale up of ART in Malawi

The national scale up of ART was planned and implemented strategically [17]. Clinics are staffed with at least one clinician (usually clinical officer grade), one nurse (who is certified to provide ART), a counsellor and a clerk. Clinics dispense ART free of charge and start 25 (low), 50 (medium) or 150 (high burden sites) new patients on treatment each month. Initially, only first line drugs were supplied, consisting of fixed dose combination (FDC) tablets of stavudine (d4T) 30mg or 40mg, lamivudine (3TC) 150 mg and nevirapine (NVP) 200 mg (Triomune™ 30 or 40). Alternative drugs, including efavirenz (EFV), were only available for NVP associated toxicity, and these drugs as well as paediatric ART were limited to central hospitals. By December 2005, 98 sites had started patients on ART, including all Central and District Hospitals. The revised 2006 national ART guidelines recommended Triomune™ 30 for all patients, children could be started in all sites and the WHO paediatric 4 stage system was adopted [18].

Patients register at the ART clinics, are clinically staged and receive cotrimoxazole (CTX) prophylaxis except adults in WHO stage 1. Patients are deemed eligible for ART if they are in WHO clinical stages 3 or 4, or have absolute CD4 counts below 200 (until 2005) or 250/μl in adults or the age dependent absolute or percent CD4 threshold in children. They attend a standardized session to understand the implications of ART, start ART with a 2 week lead in phase with a lower dose of nevirapine (NVP) unless on TB treatment, and receive monthly supplies of Triomune™. If adherence is good, patients receive ART for two months.

Monitoring and evaluation system

The monitoring and evaluation system has been described elsewhere [13–15]. The system is based on tools recommended by WHO, including a master card for each ART patient and a patient register at each facility. At ART initiation, clinicians enter date, type of regimen and demographics on the patient’s treatment card and this information is later transcribed into the ART register by a clerk. At each scheduled visit, the following primary outcomes are assessed and recorded on the treatment card by the clinician or nurse: alive and on ART, stopped all ART (for any reason, such as treatment fatigue or toxicity), LTFU (not been seen in the clinic more than 2 months after dispensed drugs have run out), transferred to another ART clinic, and death (based on a reliable report about the patient’s death). Secondary outcomes included side effects, change of regimen and pill counts.

Outcomes are transcribed at least quarterly to the ART register and information is updated in the register where appropriate. For example, a patient who was lost to follow-up and came back to restart ART would be reclassified as alive and on ART, a patient found to receive ART elsewhere would be classified as transferred out, and a patient found to have died would be recorded as a death. A MoH supervision team, consisting of two trained supervisors, visits each site quarterly and checks all treatment cards and ART site registers for completeness and consistency [19]. The supervision teams aggregate data in quarterly national reports. Since 2006, an Electronic Medical Records System using touchscreen computers has been introduced at sites exceeding 2000 patients [20]. A recent audit of data quality found that monitoring and evaluation of the ART programme was well organized and produced good quality data [15].

Data collection

Between April and June 2008, two photography clerks visited all public and private ART sites and photographed ART registers to create a set of digital images using 2 digital cameras, four 2GB SD memory cards, 2 sets of re-chargeable batteries, chargers and 2 wooden camera frames (jigs) for fixed distance image collection. The jig allowed a constant focal distance to ensure that the camera captured the entire page with maximum clarity. The left and right pages were labelled with blue tags with page numbers to ensure proper pairing of pages. Patients’ and guardians’ names and addresses were covered and were invisible on the pictures to protect confidentiality. Images were enhanced and aligned using Google’s Picasa™ –software for optimal data transcription; images were backed up on a 150 GB external hard drive. Thereafter, six data clerks transcribed the data into an Excel database by double entry using the enhanced digital images. The project manager supervised data entry and conducted data validation, using the Excel Synkronizer plug-in. The database contained the following variables: ART registration number and date of registration, age, sex, transfer, date of starting ART, reason for ART, and primary outcomes with dates. The data from nine sites with electronic records were merged with the database.

Study population

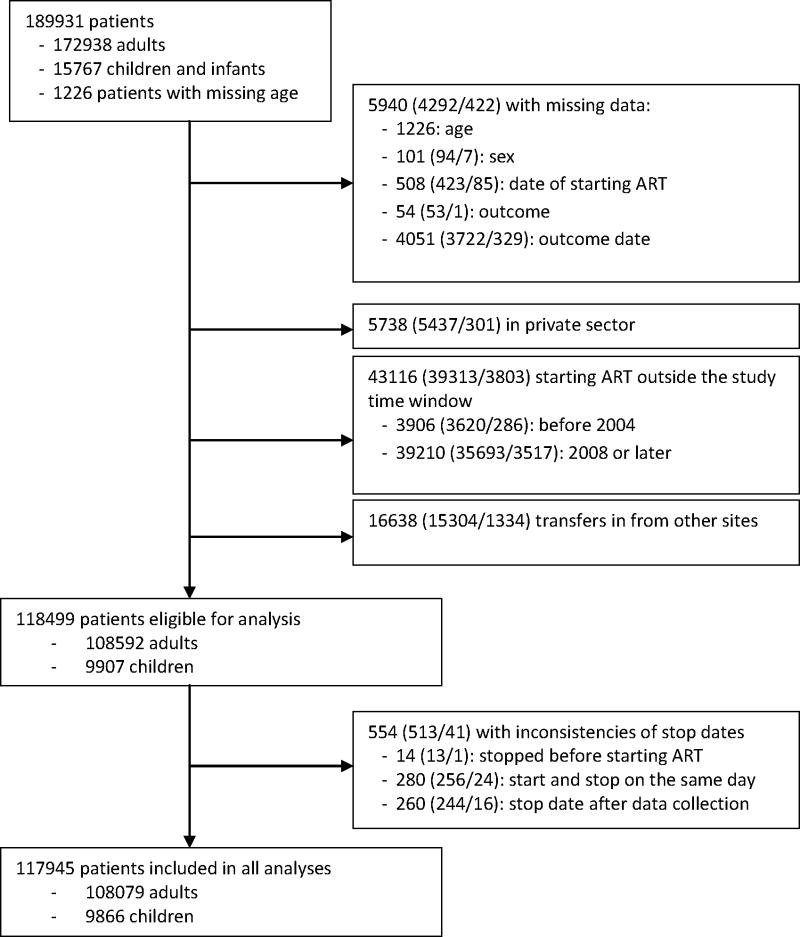

The analysis includes patients who started treatment between 1st January 2004 and 31st December 2007 in the public sector through their first 12 months on ART and excludes patients with unknown age, sex, start date and date and type of outcome (Figure 1). In addition, patients of private sector sites had to be excluded since data quality was poor. Patients who started ART elsewhere and were transferred in had to be excluded from the analysis to avoid double counting: the program does not use a unique national identification number. Patients transferred out were censored at their last follow-up visit. We considered three endpoints: mortality, LTFU and retention on ART, defined as the reciprocal of death, LTFU and treatment stop combined.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients included.

The figures in brackets give the number of adults aged ≥ 15 years/the number of infants and children aged 0–14 years.

Statistical analysis

We used competing risk models to analyze the time to LTFU and the time to death, as measured from the start of ART (i.e. baseline) [21]. Competing risk analysis assumes that each patient is exposed to two or more risks, which may not be independent. One of these outcomes is the event of interest, while the others are competing events. The analyses were censored one year after starting ART. The multivariable models included patient-level (age group, gender, WHO stage and year of start) and clinic-level (degree of urbanization, region and health facility level) variables. Age groups included infants 0–1 years of age, children 2–5 and 6–14 years, and adults 15–24, 25–34, 35–44 and ≥45 years. We investigated possible interactions between age group and all other variables. Retention on ART was analyzed by fitting a Cox proportional hazards regression model for outcomes death, LTFU and stopping treatment combined, adjusted for the same variables as in the competing risk analyses. Results are shown as sub-hazard ratios (sHR) from the competing risk analysis and hazard ratios (HR) from the Cox regression, with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

In a separate analysis we used a web calculator developed by the International epidemiological Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA, available at www.iedea-sa.org) to obtain estimates of mortality that are corrected for LTFU. The calculations are based on the fact that overall mortality is the average of mortality in patients retained in care and mortality in patients lost to follow-up, weighted by the proportion of patients lost to follow-up [22]. Mortality in patients LTFU was estimated based on a meta-analysis of studies that assessed the vital status of patients by tracing them [23].

Confidentiality and ethical approval

Measures are in place in all ART facilities to ensure patient confidentiality, consent for HIV testing, and counselling and support for those who receive a positive HIV test result. Studies using data collected routinely within the context of monitoring and evaluation, such as ART registers, do not require formal approval by the Malawi National Health Science Research Committee.

RESULTS

The dataset included 189,931 patients from 211 clinics; 117,945 patients from 148 clinics met the eligibility criteria and were analysed (Figure 1). The median age of patients was 34 years and 1.0% were infants <2 years, 7.4% children 2–14 years, 7.5% were young people 15 to 24 years and 84.2% were 25 years and older (Table 1). Sixty percent of all patients were female and the gender ratio showed a characteristic pattern across age groups: women outnumbered men from age 14 to 40 years, with a peak female-to-male ratio of 6.3 at the age of 20 (web appendix Figure S1). The proportion of patients with WHO clinical stage 3 or 4 was similar for adults (85.8%), children 2–14 years (85.2%), and infants (84.4%). Between 2004 and 2007 the proportion of annual ART initiations that were in infants and children increased from 6.0% to 9.6%.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at start of antiretroviral therapy

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 0-1 | 1178 | 1.0% |

| 2-5 | 3737 | 3.2% |

| 6-14 | 4951 | 4.2% |

| 15-24 | 8821 | 7.5% |

| 25-34 | 40703 | 34.5% |

| 35-44 | 36342 | 30.8% |

| 45- | 22213 | 18.8% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 71247 | 60.4% |

| Male | 46698 | 39.6% |

| WHO stage at start | ||

| I or II | 16813 | 14.3% |

| III or IV | 101132 | 85.7% |

| Year of starting ART | ||

| 2004 | 6809 | 5.8% |

| 2005 | 21378 | 18.1% |

| 2006 | 37948 | 32.2% |

| 2007 | 51810 | 43.9% |

| Region | ||

| Northern | 16536 | 14.0% |

| Central | 38865 | 33.0% |

| Southern | 62544 | 53.0% |

| Degree of urbanization | ||

| Urban | 60688 | 51.5% |

| Semiurban | 21069 | 17.9% |

| Rural | 36188 | 30.7% |

| Health care facility | ||

| Central hospital | 16414 | 13.9% |

| District hospital | 65363 | 55.4% |

| Rural hospital | 5317 | 4.5% |

| Health centre | 14018 | 11.9% |

| Others* | 16833 | 14.3% |

| TOTAL | 117945 | 100.0% |

Non-governmental Organizations, armed forces, occupational clinics

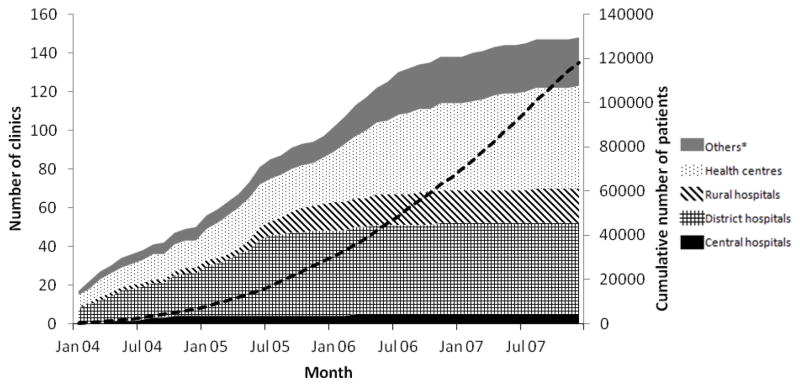

The number of clinics grew steadily from 17 in January 2004 to 148 in December 2007 and more patients started treatment each year: from 6,809 in 2004 to 51,810 in 2007, reaching the cumulative number of 117,945 by December 2007 (Figure 2). Most clinics (n=66, 45%) were in southern Malawi, where the majority of patients were started on ART (n=62,544, 53%). Though the majority of clinics were health centres (n=53, 36%), most adults (56%) and children 2–14 years (48%) started in district hospitals and clinics located in urban areas (52% of adults and 48% of children, respectively, Table 1). Thirty-three clinics had only adults and in two clinics the majority of patients were children and infants. Most ‘other’ facilities were run by Malawian non-governmental organisations.

Figure 2. Number of clinics and cumulative number of patients (dashed black line) starting ART between 2004 and 2007.

* Facilities run by non-governmental organizations or armed forces, occupational clinics

Mortality, loss to follow-up and retention on ART

Patients were followed for a total of 85,246 person-years. At 12 months outcomes were as follows: 81,980 (69.5%) patients were alive and on ART in the same clinic, 14,425 (12.2%) had died, 11,827 (10.0%) were LTFU, 9,432 (8.0%) had transferred to another clinic and 281 (0.2%) had stopped ART.

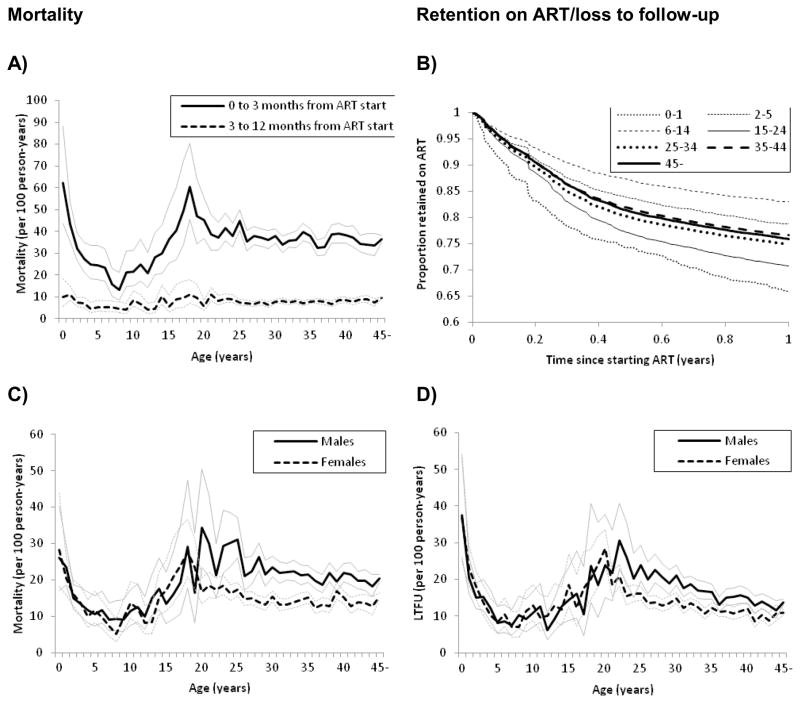

Mortality rates in children and infants decreased from 24.3 per 100 person-years during the period of the first 3 months on ART to 5.9 per 100 person-years during months 4 to 12; the corresponding numbers for adults were 37.0 per 100 person-years and 8.0 per 100 person-years. Figure 3A shows the mortality for the two periods by age at start of ART: infants <2 years (47.0 per 100 person-years) and young people aged 15–24 years (40.8 per 100 person-years) had the highest early mortality. Infants and young people had also the highest rates for LTFU over 12 months (24.7 and 19.3 per 100 person-years, respectively). As a result, retention in these age groups was lowest, while children 6 to 14 years were most likely to remain in care, followed by children aged 2–5 years (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Mortality and loss to follow-up within one year of starting antiretroviral therapy.

A: Mortality rates per 100 person-years with 95% confidence intervals in months 1–3 and months 4–12 months after start of antiretroviral therapy by age group.

B: Kaplan-Meier probability of retention on ART over the first year on ART for different age groups.

C and D: Mortality and LTFU rates per 100 person-years by age at start of ART and sex.

The higher mortality and LTFU rates in infants and young people were confirmed in the multivariable analysis with adjusted sHRs for mortality of 1.37 (95%CI 1.17–1.60) in infants and 1.17 (95%CI 1.10–1.25) in young people compared to adults 25 to 34 years. For LTFU the corresponding sHRs were 1.37 (95%CI 1.18 to 1.59) and 1.27 (95%CI 1.19 to 1.35, Table 2). Male sex was associated with a faster progression to death and a higher risk of LTFU, and this was particularly pronounced in adults 25–34 years of age (Figure 3C, 3D; the sHR of mortality 1.50, 95%CI 1.42–1.59, p-value for interaction <0.001; sHR for LTFU 1.29, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.38, p-value for interaction <0.001). WHO stages 3 and 4 were associated with higher mortality; this was more pronounced in adults of all ages compared to children (p-value for interaction <0.001). Over calendar years, the risk of death decreased whereas the risk of LTFU increased: the sHR comparing 2004 with 2007 was 1.65 (95%CI 1.54–1.76) for mortality and 0.56 (95%CI 0.51 to 0.62) for LTFU, resulting in a similar probability of retention each year (Table 2; web appendix Figure S2). Finally, there were differences between health care facilities. For example, mortality in central hospitals was lower and LTFU higher in central hospitals compared to district hospitals.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for mortality, loss to follow up and retention on ART.

| Mortality | Loss to follow up | Retention on ART | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted sHR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted sHR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 1.37 (1.17–1.60) | 1.37 (1.18–1.59) | 0.71 (0.64–0.79) | |||

| 2–5 | 0.81 (0.73–0.90) | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 1.25 (1.16–1.35) | |||

| 6–14 | 0.63 (0.57–0.70) | 0.63 (0.56–0.70) | 1.66 (1.54–1.79) | |||

| 15–24 | 1.17 (1.10–1.25) | 1.27 (1.19–1.35) | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | |||

| 25–34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 35–44 | 0.94 (0.91–0.98) | 0.81 (0.77–0.85) | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | |||

| 45– | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.75–0.83) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.09–1.17) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 1.39 (1.34–1.44) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.17–1.26) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.73–0.77) | <0.001 |

| WHO stage at start | ||||||

| I or II | 0.48 (0.45–0.52) | 0.59 (0.55–0.63) | 1.93 (1.84–2.02) | |||

| III or IV | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Year of starting ART | ||||||

| 2004 | 1.65 (1.54–1.76) | 0.56 (0.51–0.62) | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | |||

| 2005 | 1.57 (1.50–1.64) | 0.88 (0.84–0.93) | 0.82 (0.79–0.85) | |||

| 2006 | 1.34 (1.28–1.39) | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 0.90 (0.88–0.93) | |||

| 2007 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northern | 1.26 (1.20–1.32) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) | 0.94 (0.90–0.97) | |||

| Central | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) | 1.11 (1.07–1.16) | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) | |||

| Southern | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Degree of urbanization | ||||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Semiurban | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | |||

| Rural | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 0.41 | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.04–1.11) | <0.001 |

| Health care facility | ||||||

| Central hospital | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | |||

| District hospital | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Rural hospital | 0.86 (0.79–0.94) | 1.11 (1.01–1.21) | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | |||

| Health centre | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | 1.28 (1.23–1.34) | |||

| Others* | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | <0.001 | 1.10 (1.05–1.14) | <0.001 |

Mortality and loss to follow were analyzed according to the competing risk method. The hazard ratios (HR) for retention on ART are calculated as inverses of hazard ratios obtained by fitting a Cox regression model with failure defined as meeting any of the following endpoints: death, loss to follow up or stopping treatment.

All analyses were adjusted for all the variables shown in the table. sHR=subhazard ratio; HR=hazard ratio; CI=confidence interval

NGOs, armed forces, occupational clinics

Mortality corrected for loss to follow-up

Observed mortality rates for each clinic together with estimated rates of mortality that take deaths among patients LTFU into account are presented in the web appendix (Figure S3). Across all clinics, the median (interquartile range, IQR) observed mortality rate was 14.6/100 person-years (9.2 – 21.6). After correcting mortality for LTFU, the median (IQR) mortality rate increased to 18.5/100 person-years (12.9 – 26.1).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of patient-level data of the national ART programme in Malawi between 2004 and 2007 showed that infants less than 2 years and young people 15 to 24 years had the highest mortality and LTFU rates in the first year of ART, in particular during the first 3 months, when mortality rates were up to 5 times higher than in the subsequent 9 months. Multivariable regression confirmed that patients starting in these age groups had the highest risk of death or LTFU. From the age of 20 years, men were more likely to die than women, with a 50% higher risk in those aged 25 to 34 years. Overall, there was a trend of decreasing mortality from 2005 onwards, but LTFU increased across all age groups, and consequently overall programme retention remained stable.

This country-wide study of ART clinics in the public sector, which in Malawi covers over 96% of all patients receiving ART, was highly representative and thus provides a comprehensive picture of ART in the country. Data were produced in paper registers under routine service conditions by providers on the ground, and their quality was assessed quarterly by Ministry of Health teams. To our knowledge this is the largest data set from a single country that includes adults and children and allows the examination of clinic-level and patient-level risk factors. Our analysis thus extends studies of national ART programmes that were limited to geographical regions [8, 24], a sample of sites [12], aggregated data [14, 25], and specific providers, such as nongovernmental organisations [7, 9]. We present outcomes across all ages in one analysis, reflecting the integrated nature of care in Malawi, and thus make valid comparisons between age groups possible.

The mortality in our cohort was higher compared to other paediatric [5, 26] and adult [8] studies. A comparable early mortality rate in infants was reported from Côte d’Ivoire [4] and Malawi [27]. In 2004–5, at primary care facilities in Lusaka in neighbouring Zambia, the overall mortality in adults was less than in our national cohort with 16.1/100 person-years, but younger people 15–29 years also had the highest mortality rate among adults (17.2/100 person-years). The early mortality in this age group was 25.6/100 person-years, considerably lower than in our study [8]. This might be caused by differences in baseline characteristics, quality of care or deaths not accounted for among patients LTFU. Recent data from Tanzania’s national ART programme report poor retention of young people on ART who had advanced disease at ART initiation [28].

We found decreasing mortality and increasing LTFU over the four years of this study, resulting in overall a stable retention of patients on ART over time. This pattern was also observed in four provinces in South Africa [29], where errors in the documentation of patients transferred out and insufficient capacity to manage the many patients contributed to the higher rates of LTFU. Our dataset included no information on individual visits: only the most recent outcome was recorded for each patient. Patients who became lost to follow-up recently therefore had less time to return to the clinic than patients lost in earlier years. This could partly explain the increase in the rate of LTFU in more recent years, but the bias is likely to be small: a study from Zambia found that the 60-day threshold for the number of days patients could be late for an appointment before being classified as LTFU performed well, with a sensitivity of 84% and misclassification of only about 5% of patients [30]. The change of policy in the treatment of HIV/TB co-infected patients may have contributed to the decline in mortality. Before 2006, HIV/TB patients had to wait with ART until completion of TB treatment or had to stop and restart ART, when TB was diagnosed while on ART. In 2006 co-treatment of HIV and TB was introduced [31].

Our study relied on routine operational data collected during normal service provision. With high workloads, errors are unavoidable, but routine supervision should have minimized their frequency. Of note, the dataset was limited to the variables required for national monitoring. It is well known that CD4 count and viral load as well as socioeconomic and anthropometric parameters are associated with patients’ outcomes, but we could not examine these variables as they were not a part of our core dataset. We also did not collect information on cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, AIDS-related diseases such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and tuberculosis, or prior exposure to antiretroviral prophylaxis as part of prevention of mother to child transmission (MTCT). By excluding patients who transferred in at ART sites we may have introduced some bias, since patients who move between clinics may have different outcomes compared to patients who stay in care at the same site [32]. Our method of taking photographs of ART registers using a simple digital camera supported by a jig, to standardize distance and focus is a novel and untested approach. However, the method was piloted, and all photographs were reviewed twice and data entry errors corrected.

In conclusion, routine data from Malawi’s ART monitoring and evaluation system not only provide useful aggregated data to guide policy [33], but also patient level data that specifically point to the needs of infants, young people and men, extending previous findings [34–36]. Malawi national guidelines have now adopted the new WHO recommendations to start adults and children earlier on ART [33], and go beyond WHO recommendations in the prevention of MTCT [37]. Late presentation and start of ART may be one reason for poor outcomes both in young people and men [38, 39]. Unfortunately, outcomes of men on ART have received little attention, despite increasing evidence that in sub-Saharan Africa their prognosis is poorer than in women [40]. Gender norms may prevent men to seek health care early or make them feel uncomfortable admitting ill health, resulting in lower and later uptake of ART [35, 41]. Male champions, popular men advocating for a change in behaviour, may have an impact [41]. Several factors facilitating access to health services have been identified in young people [42]: services should be free, respect young people’s need for privacy and involve them in decision making. In Zambian children on ART, factors associated with poor adherence included changing residence, school attendance, lack of HIV disclosure to the child, and increasing household income [43]. ART programs should collaborate more closely with schools, and with youth-friendly services in the community [44, 45], for example teen clubs [44], and involve these services in efforts to improve retention on ART.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Clinton Health Access Initiative, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Grant 5U01-AI069924-05, a PROSPER fellowship to O.K. supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 32333B_131629) and a PhD student fellowship to J.E. from the Swiss School of Public Health.

Footnotes

Lydia Lo contributed to the design, data collection and data management of the study. Chris Buck commented and helped editing the paper.<br>R.W., A.H., S.M., H.T. and A.J. coordinated data collection, H.T. and A.J. performed the data management. J.E., O.K., M.E. and A.J. designed the statistical analyses which were performed by J.E. and O.K. R.W. and J.E. wrote the first draft of the manuscript which was revised by O.K., A.H. and M.E. All authors approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, Gove S, Perriens J, Souteyrand Y, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2006;368(9534):505–510. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. “Three Ones” Key principles. 2004 Available at: http://data.unaids.org/UNA-docs/three-ones_keyprinciples_en.pdf.

- 3.WHO. Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector Progress report. 2010 Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2010progressreport/en/

- 4.Anaky MF, Duvignac J, Wemin L, Kouakoussui A, Karcher S, Toure S, et al. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected children in Cote d’Ivoire: determinants of survival and loss to programme. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(7):490–499. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton-Moore C, Mubiana-Mbewe M, Cantrell RA, Chintu N, Stringer EM, Chi BH, et al. Clinical outcomes and CD4 cell response in children receiving antiretroviral therapy at primary health care facilities in Zambia. JAMA. 2007;298(16):1888–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.16.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulle A, Bock P, Osler M, Cohen K, Channing L, Hilderbrand K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(9):678–687. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauvageot D, Schaefer M, Olson D, Pujades-Rodriguez M, O’Brien DP. Antiretroviral therapy outcomes in resource-limited settings for HIV-infected children <5 years of age. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1039–e1047. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mwango A, Chi BH, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. JAMA. 2006;296(7):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, Traore M, Dakoury-Dogbo N, Duvignac J, et al. Rapid scaling-up of antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d’Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS. 2008;22(7):873–882. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f768f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chasombat S, McConnell MS, Siangphoe U, Yuktanont P, Jirawattanapisal T, Fox K, et al. National expansion of antiretroviral treatment in Thailand, 2000–2007: program scale-up and patient outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(5):506–512. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181967602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McConnell MS, Chasombat S, Siangphoe U, Yuktanont P, Lolekha R, Pattarapayoon N, et al. National program scale-up and patient outcomes in a pediatric antiretroviral treatment program, Thailand, 2000–2007. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(4):423–429. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181dc5eb0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowrance DW, Ndamage F, Kayirangwa E, Ndagije F, Lo W, Hoover DR, et al. Adult clinical and immunologic outcomes of the national antiretroviral treatment program in Rwanda during 2004–2005. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(1):49–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b03316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makombe SD, Hochgesang M, Jahn A, Tweya H, Hedt B, Chuka S, et al. Assessing the quality of data aggregated by antiretroviral treatment clinics in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(4):310–314. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowrance D, Filler S, Makombe S, Harries A, Aberle-Grasse J, Hochgesang M, et al. Assessment of a national monitoring and evaluation system for rapid expansion of antiretroviral treatment in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(3):377–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John Snow I. Draft Report for the Data Quality Audit for HIV/AIDS in Malawi (MLW-102-G01-H, MLW-506-G03-H, MLW-708-G07-H. 2011 Available at: http://www.hivunitmohmw.org/uploads/Main/DQA%20Final%20Report%20July2011.pdf.

- 16.Lowrance DW, Makombe S, Harries AD, Shiraishi RW, Hochgesang M, Aberle-Grasse J, et al. A public health approach to rapid scale-up of antiretroviral treatment in Malawi during 2004–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(3):287–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181893ef0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health Malawi. A five year plan for the provision of antiretroviral therapy and good management of HIV related diseases to HIV infected patinets in Malawi 2006 to 2010. 2006 Available at: http://www.hivunitmohmw.org/uploads/Main/ARV-ScaleUpPlan_2006-2010.pdf.

- 18.Ministry of Health Malawi. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. 2. Vol. 2006. Lilongwe: Dec, 2005. Treatment of AIDS. Available at: http://www.hivunitmohmw.org/uploads/Main/Malawi-ARV-Guidelines-2ndEdition.doc. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Libamba E, Makombe S, Mhango E, de Ascurra TO, Limbambala E, Schouten EJ, et al. Supervision, monitoring and evaluation of nationwide scale-up of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(4):320–326. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.023952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Douglas GP, Gadabu OJ, Joukes S, Mumba S, McKay MV, Ben-Smith A, et al. Using touchscreen electronic medical record systems to support and monitor national scale-up of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. PLoS Med. 2010;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1999:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Spycher BD, Sidle J, Weigel R, Geng EH, Fox MP, et al. Correcting mortality for loss to follow-up: a nomogram applied to antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornell M, Technau K, Fairall L, Wood R, Moultrie H, Van CG, et al. Monitoring the South African National Antiretroviral Treatment Programme, 2003–2007: the IeDEA Southern Africa collaboration. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(9):653–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somi G, Matee M, Makene CL, Van Den Hombergh J, Kilama B, Yahya-Malima KI, et al. Three years of HIV/AIDS care and treatment services in Tanzania: achievements and challenges. Tanzan J Health Res. 2009;11(3):136–143. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v11i3.47700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bock P, Boulle A, White C, Osler M, Eley B. Provision of antiretroviral therapy to children within the public sector of South Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(9):905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laufer MK, van Oosterhout JJ, Perez MA, Kanyanganlika J, Taylor TE, Plowe CV, et al. Observational cohort study of HIV-infected African children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(7):623–627. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000220264.45692.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somi G, Arthur G, Gongo R, Senkoro K, Kellogg T, O’Donnell J, et al. 24-Month Outcomes for Adults in Tanzania’s National ART Program from 2004 to 2009: Success Maintained during Scale-up, but Should Services Be More Youth Friendly?. 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Abstract number 1019; Boston. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornell M, Grimsrud A, Fairall L, Fox MP, Van CG, Giddy J, et al. Temporal changes in programme outcomes among adult patients initiating antiretroviral therapy across South Africa, 2002–2007. AIDS. 2010;24(14):2263–2270. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833d45c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chi BH, Cantrell RA, Mwango A, Westfall AO, Mutale W, Limbada M, et al. An empirical approach to defining loss to follow-up among patients enrolled in antiretroviral treatment programs. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(8):924–931. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Oosterhout JJ, Kumwenda JJ, Beadsworth M, Mateyu G, Longwe T, Burger DM, et al. Nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy started early in the course of tuberculosis treatment in adult Malawians. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(4):515–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu JK, Tok TS, Tsai JJ, Chang WS, Dzimadzi RK, Yen PH, et al. What happens to patients on antiretroviral therapy who transfer out to another facility? PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e2065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ministry of Health Malawi. Malawi Integrated Guidelines for Clinical Management of HIV, 2011, First Edition. Available at: http://www.hivunitmohmw.org/uploads/Main/Malawi%20Integrated%20Guidelines%20for%20Clinical%20Management%20of%20HIV%202011%20First%20Edition.

- 34.Bong CN, Yu JK, Chiang HC, Huang WL, Hsieh TC, Schouten EJ, et al. Risk factors for early mortality in children on adult fixed-dose combination antiretroviral treatment in a central hospital in Malawi. AIDS. 2007;21(13):1805–1810. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282c3a9e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen SC, Yu JK, Harries AD, Bong CN, Kolola-Dzimadzi R, Tok TS, et al. Increased mortality of male adults with AIDS related to poor compliance to antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(4):513–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taylor-Smith K, Tweya H, Harries A, Schoutene E, Jahn A. Gender differences in retention and survival on antiretroviral therapy of HIV-1 infected adults in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2010;22(2):49–56. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v22i2.58794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schouten EJ, Jahn A, Midiani D, Makombe SD, Mnthambala A, Chirwa Z, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: time for a public health approach. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):282–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornell M, Myer L, Kaplan R, Bekker LG, Wood R. The impact of gender and income on survival and retention in a South African antiretroviral therapy programme. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(7):722–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02290.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrand RA, Munaiwa L, Matsekete J, Bandason T, Nathoo K, Ndhlovu CE, et al. Undiagnosed HIV infection among adolescents seeking primary health care in Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(7):844–851. doi: 10.1086/656361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornell M, McIntyre J, Myer L. Men and antiretroviral therapy in Africa: our blind spot. Trop Med Int Health. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nattrass N. Gender and access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. Feminist Economics. 2008;14(4):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO. Adolescent friendly health services. An agenda for change. 2002 Available at: http://www.who.int/child_adolescent_health/documents/fch_cah_02_14/en/index.html.

- 43.Haberer JE, Cook A, Walker AS, Ngambi M, Ferrier A, Mulenga V, et al. Excellent adherence to antiretrovirals in HIV+ Zambian children is compromised by disrupted routine, HIV nondisclosure, and paradoxical income effects. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UNICEF. Children and AIDS: Fifth Stocktaking Report. 2010 Available at: http://www.unicef.org.uk/Latest/Publications/Children-and-AIDS-5th-Stocktaking-Report-2010/

- 45.UNICEF. Second Global Consultation on Service Provision for Adolescents Living with HIV. Consensus Statement. 2010 Available at: http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/Communique_ALHIV_Final2.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.