Abstract

Purpose

This phase I study investigated the maximum-tolerated dose (MTD), safety, pharmacodynamics, immunological correlatives, and anti-tumor activity of CP-870,893, an agonist CD40 antibody, when administered in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA).

Experimental Design

Twenty-two patients with chemotherapy-naïve advanced PDA were treated with 1000 mg/m2 gemcitabine once weekly for 3 weeks with infusion of CP-870,893 at 0.1 mg/kg or 0.2 mg/kg on day 3 of each 28 day cycle.

Results

CP-870,893 was well-tolerated; one dose-limiting toxicity (grade 4 cerebrovascular accident) occurred at the 0.2 mg/kg dose level, which was estimated as MTD. The most common adverse event was cytokine release syndrome (grade 1 to 2). CP-870,893 infusion triggered immune activation marked by an increase in inflammatory cytokines, an increase in B cell expression of co-stimulatory molecules, and a transient depletion of B cells. Four patients achieved a partial response (PR). [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) demonstrated >25% decrease in FDG uptake within primary pancreatic lesions in 6 of 8 patients; however, responses observed in metastatic lesions were heterogeneous with some lesions responding with complete loss of FDG uptake while other lesions in the same patient failed to respond. Improved overall survival correlated with a decrease in FDG uptake in hepatic lesions (R = −0.929; p = 0.007).

Conclusions

CP-870,893 in combination with gemcitabine was well-tolerated and associated with anti-tumor activity in patients with PDA. Changes in FDG uptake detected on PET/CT imaging provide insight into therapeutic benefit. Phase II studies are warranted.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer; immunotherapy; CD40; CP-870,893; PET imaging; heterogeneity

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States and is notoriously resistant to conventional forms of treatment including chemotherapy and radiation therapy (1, 2). This finding may be related to emerging data demonstrating the importance of the tumor microenvironment in regulating therapeutic efficacy (3-6). In PDA, the tumor microenvironment is marked by poor vascularity, dense desmoplasia, and a leukocyte reaction dominated by macrophages (3, 7, 8). Strategies that target this desmoplastic reaction may be critical for improving therapeutic efficacy in PDA (3, 5).

Tumor-associated macrophages, among other hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells, can express the cell surface molecule CD40, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily (9). CD40 is a major determinant in the development of T cell dependent anti-tumor immunity through its ability to “license” antigen-presenting cells for tumor-specific T cell priming and activation (10-15). In a preclinical model of PDA, we reported that systemic CD40 activation can also induce tumor regression that is independent of T cells, but requires macrophages that rapidly infiltrate tumor lesions, become tumoricidal, and attack the tumor microenvironment by facilitating stromal depletion (16).

CP-870,893 is a fully human and selective CD40 agonist monoclonal antibody (mAb) that as a single agent has demonstrated promising clinical activity, particularly in patients with melanoma (17). Because preclinical data suggest that chemotherapy can synergize with CD40 agonists, we conducted a phase I study using CP-870,893 in combination with gemcitabine and observed major tumor regressions in some patients with advanced PDA (16). Here, we report a final analysis with biological correlatives of treatment with CP-870,893 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced PDA. The primary objective was to define safety, tolerability, MTD, and recommended Phase 2 dose (RP2D) of CP-870,893 when given in combination with gemcitabine. Secondary objectives were to evaluate clinical activity as well as pharmacodynamics and immune modulation. We also performed novel analyses of metabolic imaging and report biologically important heterogeneity in the treatment response of primary and metastatic lesions.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Twenty-two patients with chemotherapy naïve advanced PDA were enrolled between June 28, 2008 and March 19, 2010 at the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA), and the Indiana University Simon Cancer Center (Indianapolis, IN).

Inclusion criteria were age >18 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1, and adequate end organ function. Exclusion criteria included previous systemic treatment for pancreatic cancer or radiotherapy within 4 weeks prior to randomization, autoimmune disorder, coagulopathy, major illness, and pregnancy or lactating.

Written informed consent was required. The study was approved by local institutional review boards.

Study Design and Treatment Plan

This was an open-label, phase I dose-escalation study. Primary objective was to determine safety, tolerability, MTD, and RP2D of CP-870,893 when given in combination with gemcitabine. Secondary objectives were to characterize pharmacodynamics, immune modulation, and preliminary evidence of efficacy including response rate, overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS).

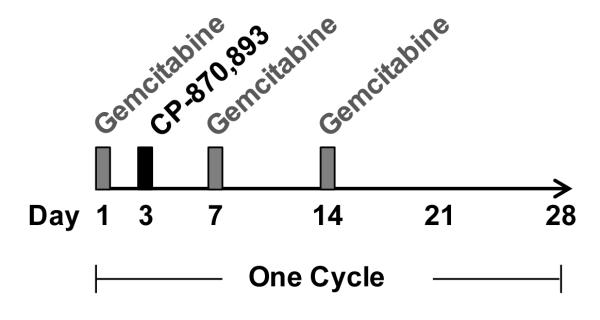

Patients received 1000 mg/m2 gemcitabine on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28 day cycle (Fig 1). Based on preclinical data demonstrating synergy when CD40 agonists are delivered 48 hours after gemcitabine, CP-870,893 was administered once during each treatment cycle on day 3 (18, 19). To determine the MTD of CP-870,893, two dose cohorts (0.1 mg/kg and 0.2 mg/kg) of at least 3 patients were enrolled based on single agent safety data (17, 20). To further evaluate safety and efficacy, an expansion cohort of at least 12 patients was planned. Safety assessments included incidence of treatment-related adverse events (AEs), according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events version 3.0, and incidence of patients experiencing dose modifications and/or premature discontinuation of study drug. Dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined during cycle 1 of treatment as treatment-related non-hematologic grade 3 to 4 AEs despite optimal supportive care; grade 3 or 4 neutropenia or grade 3 febrile neutropenia; grade 4 thrombocytopenia or grade 3 thrombocytopenia associated with bleeding; grade 4 lymphopenia if complicated by infection, or any other grade 3 hematologic adverse event. MTD was estimated as the highest dose level at which fewer than two of six patients experienced DLT. Patients continued treatment until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. CP-870,893 was supplied by Pfizer Corporation (17, 21).

Figure 1.

Treatment schema. Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) was infused on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28 day cycle with CP-870,893 administered once during each treatment cycle on day 3.

Pharmacodynamic Studies

Serum and peripheral blood for assessment of cytokines and B lymphocyte activation were obtained at baseline and at defined times during cycle 1 after infusion of gemcitabine and CP-870,893. Serum cytokine levels of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Peripheral-blood CD19+ B lymphocytes were evaluated by flow cytometry, and molecules of equivalent soluble fluorochrome (MESF) were calculated for HLADR (major histocompatibility molecule complex [MHC] class II) and CD86 (costimulatory molecule).

Tumor Response

All patients who received at least one dose of CP-870,893 were evaluated for toxicity and efficacy. Tumor response was assessed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline and every 8 weeks according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0.

PET Data Acquisition and Analysis

Metabolic activity was assessed in patients enrolled in the MTD expansion cohort by determining [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake within tumor lesions seen on positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging at baseline, 2 weeks, 8 weeks, and then every 8 weeks while on treatment. FDG-PET/CT was performed after patients had fasted for ≥6 hours and plasma glucose levels were determined to be <200 mg/dl. Approximately 15 mCi of FDG were administered intravenously, and images were acquired ~60 minutes later from skull base to mid thighs. Analysis was performed using the ROVER software package (ABX, GmbH, Germany), providing a semi-automated approach to delineate FDG avid lesions and to estimate metabolically active volume (MAV) and mean standardized uptake value (SUVmean) for individual lesions from PET datasets as previously described (22). For each tumor lesion, mean metabolic volumetric product (MVPmean) was determined by multiplying metabolism by volume [i.e. MVPmean = SUVmean x MAV]. Total MVPmean, a quantitative measure of global disease burden, was determined by summing MVPmean of all lesions. Total hepatic lesion MVPmean, a measure of hepatic disease burden, was determined by summing MVPmean of hepatic lesions only. Image assessment also included measuring the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) for each of five target lesions and determining the sum of SUVmax for all lesions.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 10.0 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station Texas, USA). PFS was defined as time from start of study treatment to disease progression or patient death, whichever occurred first. OS was defined as time from start of study treatment to patient’s death. PFS and OS were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methods. The Spearman rank test was used to estimate correlations between changes in biomarkers relative to baseline and OS. For analysis of change from baseline of pharmacodynamic end points, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed. All analyses were carried out per protocol on patients receiving at least one dose of CP-870,893.

Results

Patient Characteristics

Twenty-two patients with advanced chemotherapy-naïve PDA were enrolled (Table 1). Ninety percent (n = 20) of patients had metastatic disease. One patient in the MTD expansion cohort received a single dose of gemcitabine and withdrew from study prior to receiving CP-870,893 due to acute cholangitis related to tumor progression. The remaining patients (n = 21) received gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) administered on days 1, 8, and 15 with infusion of CP-870,893 at either 0.1 mg/kg or 0.2 mg/kg on day 3 of a 28 day cycle (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| CP-870,893 Dose

Cohort |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 mg/kg (N=3) |

0.2 mg/kg (N=6) |

MTD Expansion 0.2 mg/kg (N=13) |

||||

| Characteristic | No | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Median | 59 | 59 | ||||

| Range | 57-72 | 40-81 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 2 | 67% | 3 | 50% | 9 | 69% |

| Female | 1 | 33% | 3 | 50% | 4 | 31% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 0 | 0% | 5 | 83% | 11 | 84% |

| Black | 3 | 100% | 1 | 17% | 1 | 8% |

| Asian | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 | 2 | 67% | 5 | 83% | 2 | 15% |

| 1 | 1 | 33% | 1 | 17% | 11 | 85% |

| Extent of Disease | ||||||

| Locally advanced | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 15% |

| Metastatic | 3 | 100% | 6 | 100% | 11 | 85% |

| Location of Primary | ||||||

| Head | 2 | 67% | 2 | 33% | 4 | 31% |

| Body or Tail | 1 | 33% | 2 | 33% | 9 | 69% |

| Not reported | 0 | 0% | 2 | 33% | 0 | 0% |

| Site of Metastases | ||||||

| Liver | 3 | 100% | 5 | 83% | 10 | 77% |

| Lung | 0 | 0% | 2 | 33% | 0 | 0% |

| Peritoneal | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 23% |

| Skeleton | 0 | 0% | 2 | 33% | 0 | 0% |

| Other | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Prior Radiation Therapies | ||||||

| No | 3 | 100% | 6 | 100% | 11 | 84% |

| Yes | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Not Reported | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; IVTD, maximum tolerated dose

Safety results, DLTs, and MTD

None of 3 patients in cohort 1 (0.1 mg/kg) or 6 patients in cohort 2 (0.2 mg/kg) experienced DLT. Among 12 evaluable patients in the expansion cohort (0.2 mg/kg), one patient experienced DLT due to grade 4 cerebrovascular accident on day 3 of cycle 1 after receiving CP-870,893 and was withdrawn from study. As this AE occurred within several hours after receiving the first dose of CP-870,893, it was considered possibly related to treatment. Clinical evaluation of the patient demonstrated paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on telemetry and MRI brain imaging revealed evidence of bilateral frontal and parietal region gray/white matter junction lesions consistent with both acute and chronic embolic infarcts. Together, these findings suggested a chronic pathological process that may have been provoked by treatment. MTD and RP2D for CP-870,893, when combined with 1000 mg/m2 gemcitabine in patients with PDA, were estimated at 0.2 mg/kg per clinical protocol.

AEs are summarized in Table 2. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was the most common AE; occurred within minutes to several hours after CP-870,893 infusion; and most commonly manifested as chills and rigors. Rigors were managed with meperidine and routinely resolved within one hour. Prophylactic use of ibuprofen (400 mg) prior to CP-870,893 infusion was provided to lower CRS grade and incidence. One patient treated in cohort 1 experienced a grade 3 CRS after CP-870,893 infusion during cycle 9. Symptoms resolved with diuretic therapy, and the patient continued on study without dose modification. However, after 10 cycles of therapy in the absence of disease progression, the patient was diagnosed with glomerulonephritis related to gemcitabine and was withdrawn from study. A second patient developed grade 3 gastrointestinal bleed related to pancreatic tumor invasion of the stomach on day 24 of cycle 1, and was eventually withdrawn from study due to development of deep vein thrombosis during hospitalization.

Table 2.

Summary of the Most Commonly Reported Adverse Events by Grade

| CP-870,893 Dose

Cohort |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 mg/kg (N=3) |

0.2 mg/kg (N=6) |

MTD Expansion 0.2 mg/kg (N=13) | ||||||||||

| Grade 1 or 2 |

Grade 3 or 4 |

Grade 1 or 2 |

Grade 3 or 4 |

Grade 1 or 2 |

Grade 3 or 4 |

|||||||

| Adverse Events | No | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Clinical events | ||||||||||||

| Cytokine release syndrome | 2 | 67% | 1 | 33% | 6 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 85% | 0 | 0% |

| Fatigue | 3 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 83% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 85% | 0 | 0% |

| Nausea | 3 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 83% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 77% | 0 | 0% |

| Vomiting | 1 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 46% | 0 | 0% |

| Pyrexia | 1 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 17% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 46% | 0 | 0% |

| Peripheral edema | 3 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 23% | 0 | 0% |

| Constipation | 1 | 33% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 6 | 46% | 0 | 0% |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 8% |

| Hematologic events | ||||||||||||

| Anemia | 3 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 67% | 1 | 17% | 10 | 77% | 2 | 15% |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | 33% | 1 | 33% | 4 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 7 | 54% | 4 | 31% |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 17% | 3 | 50% | 3 | 23% | 2 | 15% |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 23% | 0 | 0% |

| Nonhematologic events | ||||||||||||

| ALT | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 4 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 8 | 62% | 0 | 0% |

| AST | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 85% | 0 | 0% |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 5 | 83% | 1 | 17% | 8 | 62% | 2 | 15% |

| Total bilirubin | 2 | 67% | 1 | 33% | 2 | 33% | 1 | 17% | 5 | 38% | 1 | 8% |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 | 67% | 1 | 33% | 2 | 33% | 4 | 67% | 11 | 85% | 1 | 8% |

| Hypocalcemia | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 17% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 77% | 0 | 0% |

| Hyponatremia | 2 | 67% | 0 | 0% | 3 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 15% | 2 | 15% |

Treatment Exposure

The median number of cycles administered was 4 (range, 1 to 12). Gemcitabine dose was reduced by 25% for thrombocytopenia or neutropenia and was required in 55% of patients with a median of 1 dose reduction (range, 0 to 5) per patient. No dose reductions in CP-870,893 were required. Discontinuation of therapy was due to progressive disease (n=14, 66%), unacceptable toxicity without progressive disease (n=1, 5%), patient discretion (n = 4, 19%), or AE (n = 2, 10%).

Immune modulation

Rapid decreases in absolute monocyte count (AMC) and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) were observed in peripheral blood one day after gemcitabine administration (Supplementary Fig S1A). Further decreases in AMC and ALC were observed after CP-870,893 infusion with a nadir on day 4. Both AMC and ALC recovered by day 8 to near baseline levels. Decreases in ALC were associated with a rapid decline in absolute levels of CD19+ B lymphocytes seen within 2 hours of CP-870,893 infusion (Supplementary Fig S1B). Cellular recovery of peripheral blood CD19+ B lymphocytes to near baseline levels was seen by day 8. A rapid increase in B cell expression of co-stimulatory molecules CD86 and HLA-DR was also observed within 24-48 hours of CP-870,893 treatment, a pattern similar to findings previously reported for CP-870,893 when used as a single agent (17). In addition, inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 transiently increased in serum of patients within 24 hours after CP-870,893 but not gemcitabine treatment (Supplementary Fig S1C). These findings are consistent with preclinical data demonstrating that CD40 agonists induce immune activation and trafficking of leukocytes to lymphoid organs (16). No relationship was found between peak cytokine levels and development or grade of CRS.

FDG-PET Response

Ten patients in the MTD expansion cohort were evaluated using European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria for partial metabolic response (PMR; >25% reduction in SUVmax) detected by FDG-PET/CT (23). Eight of 10 patients completed at least two cycles of therapy, and two achieved a PMR. To further quantify metabolic responses, we determined the percentage reduction in the sum of SUVmax for up to five predefined lesions (up to 2 per organ) with the most intense FDG uptake (24). On average, the sum of SUVmax was reduced by 29% in target lesions after two cycles of therapy with 6 of 8 patients achieving >25% reduction.

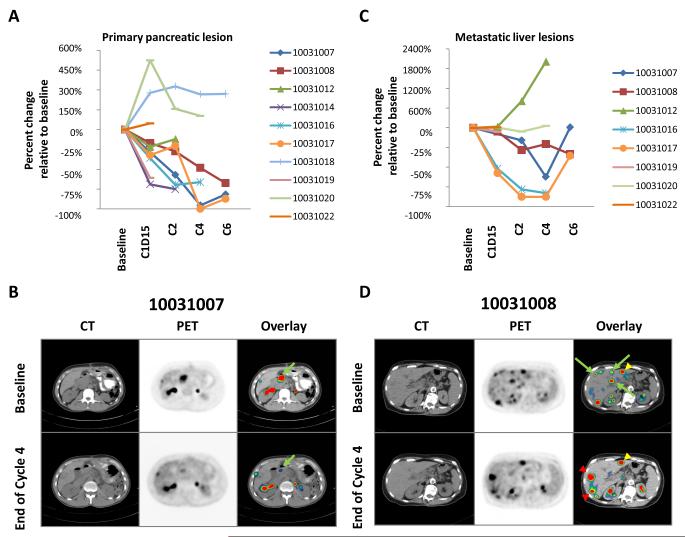

Because preclinical data demonstrate the capacity of CD40 agonists to target the microenvironment of primary pancreatic tumors (16), we examined metabolic responses specifically within the primary lesion. After two cycles of therapy, an average reduction of 26.9% in SUVmax was observed in pancreatic lesions, and all patients showed some reduction. To quantify this metabolic response, changes in primary tumor MVPmean were determined. A decrease in MVPmean was observed in 6 of 8 patients after two cycles of therapy with changes seen as early as day 15 (Fig 2A and 2B). Further reductions in MVPmean were also observed with subsequent cycles of therapy. However, after six cycles of therapy, three patients, despite achieving >50% reduction in MVPmean of the primary lesion, were withdrawn from study due to progressive disease of metastatic lesions. This suggested heterogeneity of the tumor response to therapy, which prompted investigation of metastatic lesions.

Figure 2.

FDG-PET/CT imaging of (A-B) primary pancreatic tumors and (C-D) metastatic hepatic lesions. (A, C) Change relative to baseline in MVPmean as a measure of metabolic activity. (B, D) CT, FDG-PET and fused PET/CT images (baseline vs. end of cycle 4) showing (B) a responding primary pancreatic lesion (green arrow) and (D) a mixed response in liver with representative new or progressive lesions (red arrowheads), stable lesions (yellow arrowheads), and responding lesions (green arrows). Also seen is normal FDG excretion in kidneys and ureters.

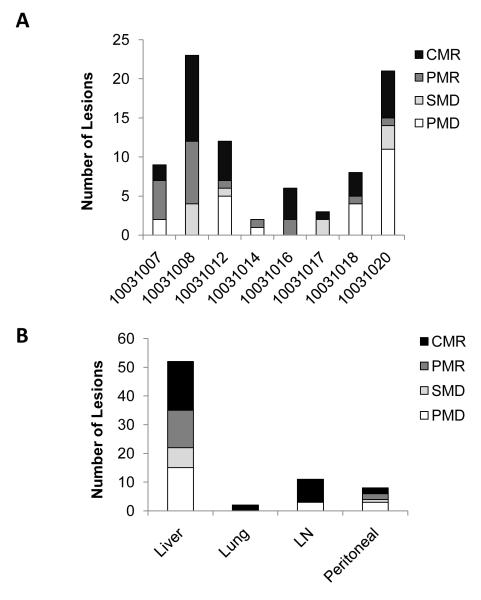

The most common metastatic site in this study was the liver (Table 1). For this reason, we evaluated the impact of therapy on metabolic responses of hepatic lesions only. Eight of 10 patients had hepatic lesions; 6 of whom completed at least two cycles of therapy. Four patients achieved a >25% reduction in total hepatic lesion MVPmean; this metabolic response, though, was sometimes transient (Fig 2C). Moreover, metabolic changes in hepatic lesions were found to be heterogeneous (Fig 2D). For patient 10031016, a marked metabolic response was observed in both the primary and hepatic lesions (Fig 2). After four cycles of therapy, we biopsied the responding hepatic lesion. We previously reported histological analysis of this lesion which demonstrated an impressive immune infiltrate that was dominated by macrophages with an absence of viable tumor cells (16). Thus, a metabolic response correlated with a pathological response for this patient. To understand the heterogeneity of metabolic responses observed with treatment, we quantified responses of all identifiable lesions after 2 cycles of therapy (Fig 3A). This analysis revealed that metabolic responses within individual patients varied considerably from complete metabolic response to progression, sometimes with development of new lesions. This treatment response heterogeneity was particularly pronounced in the liver (Fig 3B). Overall, these data demonstrate that FDG-PET/CT based treatment responses were heterogeneous in many patients.

Figure 3.

The response of individual lesions measured by changes in lesional MVPmean from baseline to end of cycle 2, shown for (A) each patient and (B) for each metastatic site (all patient lesions pooled) including liver, lung, lymph node (LN), and peritoneal cavity. Changes in MVPmean were classified as complete metabolic response (CMR) indicating disappearance of lesion; partial metabolic response (PMR) indicating >25% reduction in MVPmean; progressive metabolic disease (PMD) indicating >25% increase in MVPmean or new lesion; and stable metabolic disease (SMD) indicating insufficient decrease to qualify for PMR and insufficient increase to qualify for PMD.

Efficacy, Pharmacodynamic and Immunologic Correlative Results

Survival

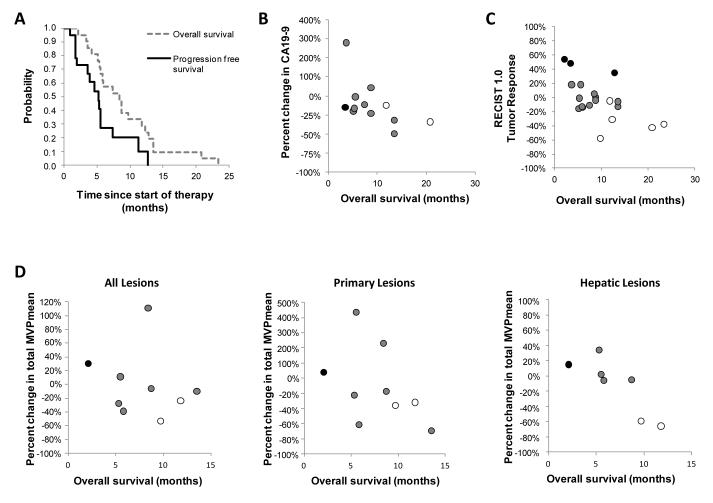

Median PFS was 5.2 months (95% CI, 1.9 to 7.4 months); median OS was 8.4 months (95% CI, 5.3 to 11.8 months); and 1-year OS was 28.6% (Fig 4A).

Figure 4.

Biological correlatives for overall survival after treatment with CP-870,893 in combination with gemcitabine. (A) Median overall survival and progression free survival for patients (n=21) receiving at least one dose of CP-870,893. Relationship between (B) percent change in CA19-9 at end of one cycle of therapy compared to baseline (R = −0.579; p = 0.049), (C) overall survival and tumor response determined by RECIST 1.0 at completion of two cycles of therapy (R = −0.652; p = 0.002), and (D) percent change in total MVPmean for all lesions, primary pancreatic lesion, and all hepatic lesions after two weeks of therapy compared to baseline (R = −0.929; p = 0.007). Best overall tumor response measured by RECIST 1.0 is indicated in (B), (C), and (D) using open circles (partial response), grey circles (stable disease), and black circles (progressive disease).

Response Rate

Overall response rate (ORR) based on RECIST 1.0 was 19% with four patients achieving a PR. Stable disease was seen in 11 patients. In addition, one patient withdrawn after one dose of CP-870,893 due to DLT restarted gemcitabine alone and achieved a PR off-study, as previously reported (16).

Correlative Studies

Exploratory analyses were performed to correlate changes in immune activation, tumor biomarkers, tumor response and metabolic response with OS. Treatment-related increases in cytokine levels (i.e. IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) during cycle 1 were not associated with OS (Supplementary Table S1). CA19-9 levels were available for 12 patients with 9 patients demonstrating decreases after cycle 1 that correlated with improved OS (Fig 4B). Response rate determined by RECIST 1.0 after cycle 2 was also associated with improved OS (Fig 4C). In contrast, metabolic responses using EORTC criteria or by evaluating SUVmax for up to five predefined lesions did not correlate with OS (Supplementary Table S1).

Because metabolic responses to therapy were heterogeneous, we examined the association between OS and changes in metabolic activity observed within the liver and pancreas separately. Changes in total MVPmean as well as SUVmax and MVPmean of primary pancreatic lesions were not associated with OS. In contrast, a decrease in total hepatic lesion MVPmean after cycle 2 was associated with improved OS (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, analysis of 7 patients with hepatic lesions who underwent FDG-PET/CT after two weeks of therapy revealed a decrease in total hepatic lesion MVPmean at this early time point that was also strongly correlated with OS (Fig 4D). Patients with a metabolic response in the liver at two weeks also achieved a PR by RECIST 1.0.

Discussion

This investigation evaluated the safety and biological impact of combining a fully human agonist CD40 mAb (CP-870,893) with gemcitabine for treatment of patients with advanced PDA. Combination treatment with CP-870,893 and full dose gemcitabine was well-tolerated and associated with objective tumor responses (19%) in patients with advanced PDA. In addition, FDG-PET/CT imaging revealed therapy-induced metabolic responses in both primary and metastatic lesions. These responses, though, were heterogeneous with some lesions responding and others progressing during therapy. All patients receiving CP-870,893 in combination with gemcitabine responded with immune activation (i.e. increases in serum cytokines and/or upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules on B lymphocytes) that was transient. However, we determined that changes in serum cytokines and peripheral lymphocyte cell populations did not correlate as biomarkers of tumor response or survival parameters. In contrast, in an exploratory analysis we found that improved overall survival correlated with a decrease in FDG uptake in hepatic lesions.

Strategies that target the stromal microenvironment may improve outcomes for patients with PDA. Preclinical studies have suggested that the mechanism of action of CP-870,893 when used in PDA is dependent on peripheral blood monocytes which are induced to rapidly leave circulation, infiltrate tumor lesions, and orchestrate degradation of the stromal microenvironment (16). Consistent with this, we observed a rapid decrease in monocyte levels in patients after CP-870,893 infusion; however, because gemcitabine also produced a decrease in peripheral blood monocytes, we speculate that the full anti-tumor activity of an agonist CD40 antibody in patients may have been hindered in the current study by myelosuppression from repeated administration of gemcitabine. In this regard, because agonist CD40 antibodies can rapidly deplete the stroma that is a critical barrier to drug delivery, we propose that chemotherapy administration after, rather than before, the infusion of CD40 agonists would represent a novel approach to enhance efficacy while eliminating potential deleterious effects of chemotherapy on CP-870,893 activity. Moreover, this treatment schedule would permit the use of functional imaging approaches such as FDG-PET/CT performed one day after administration of CP-870,893 to investigate the impact of delivering an agonist CD40 antibody on the biology of primary and metastatic tumor lesions. To understand the impact of therapy on tumor-associated stroma, tissue biopsies could also be performed before and after delivery of CP-870,893 or alternatively, CP-870,893 could be administered to patients with resectable PDA in the neoadjuvant setting prior to surgical resection. It is expected that these study approaches would provide further insight into the biological impact of CP-870,893 on PDA tumor biology.

In this Phase I study, we administered CP-870,893 two days after gemcitabine chemotherapy based on preclinical data demonstrating the effectiveness of this treatment schedule in producing robust T cell dependent anti-tumor immunity (18). Treatment with CP-870,893 was administered monthly to allow sufficient time for resolution of immune activation and to coincide with the schedule of gemcitabine chemotherapy. In addition, this timeframe was selected based on previous investigation demonstrating deleterious effects on T cells when CP-870,893 was administered more frequently (i.e. weekly dosing) to patients with advanced cancer (20). However, in our studies of this treatment schedule, we have found that anti-tumor T cell immunity is not induced when a CD40 agonist is administered two days after gemcitabine chemotherapy in a clinically relevant mouse model of PDA (16). This discrepancy between our findings and previously reported work may be related to immune suppression imposed by PDA which may inhibit the development of productive anti-tumor T cell immunity. Consistent with our preclinical findings, tumor biopsies from patients with PDA treated on this Phase I study revealed an absence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and an abundance of macrophages which we have previously reported are required for the anti-tumor effects observed with CD40 agonists (16). Although lymphocytes do not appear to be involved in anti-tumor immunity induced with CD40 agonists in PDA, we speculate that chronic immune activation reported with weekly dosing of CP-870,893 could be detrimental as inflammation can also be a key driver of tumorigenesis. Nonetheless, shorter dosing intervals that allow for sufficient time for resolution of immune activation (e.g. every 3 weeks) could be explored in subsequent clinical studies. Moreover, future combinations of CP-870,893 with chemotherapy should include more efficacious chemotherapeutic regimens such as FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (5, 25).

To understand the impact of therapy on tumor biology, we incorporated FDG-PET/CT imaging into this study. FDG-PET/CT has been used to assess responses to chemotherapies and targeted therapies in various solid malignancies including PDA (5, 26, 27). However, its utility in predicting responsiveness to immunotherapy in solid malignancies has not been well explored. SUVmax is the most common semi-quantitative approach applied to PET image analysis; however, SUVmax only reflects a small fraction of the metabolic activity in any given lesion. For this reason, we calculated MVPmean of individual lesions as an overall measure of metabolic activity (22) and demonstrated the ability of FDG-PET/CT obtained as early as two weeks after therapy to detect metabolic responses in primary and metastatic lesions. In our investigation for imaging biomarkers, we found a lack of statistically significant associations between overall survival and changes in many FDG-PET imaging correlatives including EORTC criteria. This finding may reflect the small sample size of this study. However, consistent with the heterogeneity in metabolic responses that we observed between primary and metastatic lesions, we found that changes in hepatic lesion MVPmean determined by FDG-PET/CT strongly correlated with OS. While decreases in primary lesion MVPmean were not statistically significant, a trend toward improved overall survival was observed and may have been appreciated with a larger sample size.

Metabolic responses were commonly seen within primary lesions with each cycle of therapy. However, the metabolic response of hepatic lesions was heterogeneous with some lesions showing no response to therapy, even in patients where other lesions responded with complete loss of metabolic activity. This disparity in response observed between primary and metastatic lesions can be observed by FDG-PET imaging in some patients receiving standard chemotherapy alone (28-30). Here, we have used FDG-PET/CT imaging to demonstrate and quantify heterogeneity in metabolic responses observed with therapy in PDA. While the role of CP-870,893 in contributing to response heterogeneity seen between primary and metastatic lesions cannot be determined from our analyses, the disparate responses observed suggest differences in tumor biology such that metastasis biology may be a unique and major site of resistance for both chemotherapy and immunotherapy based approaches.

Although the results from this Phase I study are encouraging, our sample size was small and thus, we are unable to determine the clinical benefit achieved with adding CP-870,893 to gemcitabine chemotherapy. As a result, further investigation with randomized clinical studies will be necessary to determine a role for CP-870,893 in the treatment of PDA. Nonetheless, our study suggests the value of incorporating early FDG-PET/CT imaging to evaluate benefit from therapeutic approaches in PDA and for understanding heterogeneity in treatment responses.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

This phase I study investigates the tolerability and clinical impact of an agonist CD40 monoclonal antibody (CP-870,893) when administered in combination with gemcitabine for the treatment of patients with chemotherapy-naive advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. We show that combination of CP-870,893 with gemcitabine is well tolerated and associated with preliminary evidence of efficacy. Treatment produced a systemic immune response that was marked by leukocyte trafficking, cytokine production and cellular activation. Using novel analyses of metabolic imaging, we observed in many patients a cumulative decrease with each cycle of therapy in the metabolic activity of the primary pancreatic lesion. However, treatment responses of metastatic lesions were heterogeneous. These findings highlight the biological heterogeneity of pancreatic carcinoma and demonstrate a role for metabolic imaging in understanding treatment responses.

Acknowledgements

We thank Maryann Redlinger, Amy Kramer, and all of our nurses and data managers from the Abramson Cancer Center for their outstanding and dedicated patient care and for careful data collection.

Financial support: The clinical trial was supported by Pfizer Corporation. Additional support in part by an American Society Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (G.L.B.) and by Grants No. K08 CA138907-02 (GLB) and R01 CA169123 (RHV) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: D.A.T. has received research funding from Pfizer Corporation. R.H.V. has received research funding from Pfizer Corporation and Roche. P.J.O. has received research funding from Pfizer Corporation. The other authors disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

Trial registration: NCT00711191

This manuscript presents original results of a phase I study of CP-870,893 with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Preliminary findings have been reported in Science 2011 331:1612-6 and at the 46th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 4-8, 2010, Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society Cancer facts and figures. 2012.

- 2.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362:1605–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, Gopinathan A, McIntyre D, Honess D, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Provenzano PP, Cuevas C, Chang AE, Goel VK, Von Hoff DD, Hingorani SR. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan RK, Borad MJ, Laheru DA, Smith LS, Wood TE, et al. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is an active regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4548–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobetz MA, Chan DS, Neesse A, Bapiro TE, Cook N, Frese KK, et al. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:112–20. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C, Tuveson DA, Vonderheide RH. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9518–27. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurahara H, Shinchi H, Mataki Y, Kuwahata T, Maeda K, Sakoda M, et al. Significance of M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage in pancreatic cancer. J Surg Res. 167:e211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elgueta R, Benson MJ, de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Guo Y, Noelle RJ. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:152–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–3. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–80. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–8. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French RR, Chan HT, Tutt AL, Glennie MJ. CD40 antibody evokes a cytotoxic T-cell response that eradicates lymphoma and bypasses T-cell help. Nat Med. 1999;5:548–53. doi: 10.1038/8426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diehl L, den Boer AT, Schoenberger SP, van der Voort El, Schumacher TN, Melief CJ, et al. CD40 activation in vivo overcomes peptide-induced peripheral cytotoxic T-lymphocyte tolerance and augments anti-tumor vaccine efficacy. Nat Med. 1999;5:774–9. doi: 10.1038/10495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sotomayor EM, Borrello I, Tubb E, Rattis FM, Bien H, Lu Z, et al. Conversion of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell tolerance to T-cell priming through in vivo ligation of CD40. Nat Med. 1999;5:780–7. doi: 10.1038/10503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beatty GL, Chiorean EG, Fishman MP, Saboury B, Teitelbaum UR, Sun W, et al. CD40 agonists alter tumor stroma and show efficacy against pancreatic carcinoma in mice and humans. Science. 2011;331:1612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1198443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vonderheide RH, Flaherty KT, Khalil M, Stumacher MS, Bajor DL, Hutnick NA, et al. Clinical activity and immune modulation in cancer patients treated with CP-870,893, a novel CD40 agonist monoclonal antibody. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:876–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nowak AK, Robinson BW, Lake RA. Synergy between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of established murine solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4490–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lake RA, Robinson BW. Immunotherapy and chemotherapy--a practical partnership. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:397–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruter J, Antonia SJ, Burris HA, Huhn RD, Vonderheide RH. Immune modulation with weekly dosing of an agonist CD40 antibody in a phase I study of patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:983–93. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.10.13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gladue RP, Paradis T, Cole SH, Donovan C, Nelson R, Alpert R, et al. The CD40 agonist antibody CP-870,893 enhances dendritic cell and B-cell activity and promotes anti-tumor efficacy in SCID-hu mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1009–17. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torigian DA, Lopez RF, Alapati S, Bodapati G, Hofheinz F, van den Hoff J, et al. Feasibility and performance of novel software to quantify metabolically active volumes and 3D partial volume corrected SUV and metabolic volumetric products of spinal bone marrow metastases on 18F-FDG-PET/CT. Hell J Nucl Med. 2011;14:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young H, Baum R, Cremerius U, Herholz K, Hoekstra O, Lammertsma AA, et al. Measurement of clinical and subclinical tumour response using [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose and positron emission tomography: review and 1999 EORTC recommendations. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) PET Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1773–82. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge MA. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122S–50S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benz MR, Herrmann K, Walter F, Garon EB, Reckamp KL, Figlin R, et al. (18)F-FDG PET/CT for monitoring treatment responses to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1684–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lordick F, Ott K, Krause BJ, Weber WA, Becker K, Stein HJ, et al. PET to assess early metabolic response and to guide treatment of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: the MUNICON phase II trial. The lancet oncology. 2007;8:797–805. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuwatani M, Kawakami H, Eto K, Haba S, Shiga T, Tamaki N, et al. Modalities for evaluating chemotherapeutic efficacy and survival time in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: comparison between FDG-PET, CT, and serum tumor markers. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2009;48:867–75. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maisey NR, Webb A, Flux GD, Padhani A, Cunningham DC, Ott RJ, et al. FDG-PET in the prediction of survival of patients with cancer of the pancreas: a pilot study. British journal of cancer. 2000;83:287–93. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klimant E, Markman M, Albu DM. Clinically meaningful responses to sequential gemcitabine-based chemotherapy regimens in a patient with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Case reports in oncology. 2013;6:72–7. doi: 10.1159/000346836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.